Abstract

The effects of elevated CO2 concentration (eCO2) on the utilization of carbohydrates in wheat cultivars with different ear types remain poorly understood, despite the critical role of wheat ears as major carbohydrate sinks and the importance of ear type as a key growth trait influencing crop yield. In this study, a free-air CO2 enrichment (CAAS-FACE) facility was utilized to investigate the effects of eCO2 on the non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) utilization in two wheat cultivars: a large-ear cultivar (cv. Shaanhan 8675) and a multiple-ear cultivar (cv. Triumph). The findings demonstrated that under eCO2 conditions, Shaanhan 8675 exhibited enhanced NSC availability and more efficient remobilization from vegetative organs to grains. This improvement was associated with sustained photosynthetic activity in the leaves during the grain-filling period, which contributed to better grain filling. Consequently, both grain NSC accumulation and kernel weight were significantly increased in Shaanhan 8675 under eCO2. In contrast, the grain NSC accumulation in Triumph was constrained by limited translocation of NSC from the stem and ear to the grain under eCO2 environment. Overall, our findings suggest that CO2 enrichment has a pronounced positive effect on NSC utilization in large-ear wheat cultivars. These results contribute to strategies aimed at ensuring stable and high wheat yields under future climatic conditions.

1. Introduction

By 2050, the expanding global population will reach 9.1 billion, which demands increased crop production to ensure global food security [1]. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the most important staple crops in the human diet, directly contributing approximately 20% of the total caloric and protein intake worldwide [2]. In China, wheat cultivation is predominantly concentrated in the central and eastern regions, with approximately 18.5 million hm2 accounting for 70.1% of the country’s total wheat planting area dedicated to its production. However, numerous studies have highlighted the potential impacts of global climate change on wheat productivity [3,4]. According to projections by the IPCC, they predicted that atmospheric CO2 concentrations are expected to reach 550 µmol·mol−1 by 2050 and up to 1020 µmol·mol−1 by 2100 [4], which will inevitably influence the production of wheat.

As a typical C3 crop, wheat exhibits high sensitivity to climatic and environmental fluctuations [5]. Since atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) serves as the substrate for Rubisco-catalyzed carboxylation in plants, variations in climate, particularly rising CO2 levels, are expected to have direct impacts on wheat production [3]. The effects of elevated CO2 concentration (eCO2) on wheat grain yield, grain quality, and plant physiological responses have been extensively investigated [4]. Furthermore, previous studies on CO2 enrichment have revealed significant interspecific variation in plant biomass accumulation and grain protein response to eCO2 [6]. This variation can be attributed to differences in photosynthetic capacity and carbohydrate utilization efficiency among genotypes with diverse genetic backgrounds [7]. Enhanced biomass production, particularly when accompanied by an optimized source–sink relationship, has been proposed as a key driver for achieving substantial increases in wheat grain yield [7]. When grown under eCO2 environment, C3 crops such as wheat can significantly increase grain yield if the carbon supply (photosynthetic capacity) and sink capacity (storage strength) are well coordinated. Specifically, this synergy involves enhanced carbon assimilation during the vegetative stage and improved sink strength during reproductive growth [8,9,10]. In wheat, the primary carbon sink is grain during the middle and late stages of growth and development; hence, the ear is a crucial carbon sink, especially during the later growth stage [11]. Numerous studies have also demonstrated that efficient carbohydrate utilization enables plants to mitigate photosynthetic downregulation under prolonged exposure to an elevated CO2 environment [12]. Therefore, future agricultural systems under elevated atmospheric CO2 will require cultivars with superior photosynthetic efficiency, enhanced carbon assimilation capacity, and effective carbon redistribution mechanisms. To address this need, we selected two winter wheat cultivars representing contrasting ear types: large-ear- and multiple-ear-type winter wheat cultivars to investigate whether genotypes with stronger reproductive sinks can achieve higher kernel weights through more efficient utilization of non-structural carbohydrates under elevated CO2 conditions.

In detail, we hypothesized that elevated carbon dioxide concentrations would enhance the photosynthetic efficiency of wheat leaves, thereby promoting greater accumulation of non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) within the plant. Large-ear wheat cultivars are expected to exhibit stronger “sink strength” during the grain-filling period, which could facilitate the translocation and reallocation of NSC stored in various vegetative organs to the developing grains. This enhanced sink capacity may, to some extent, allow for functional leaves to maintain a higher photosynthetic rate during the grain-filling stage, leading to increased NSC accumulation in the grains and, consequently, improved kernel weight. The findings of this study will contribute to the theoretical understanding of how climate resources can be effectively utilized in crop production, supporting strategies for ensuring stable and high wheat yields under future CO2-enriched environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Growing Conditions

This study was conducted at the wheat–maize rotation CAAS-FACE system in Changping (40°13′ N, 116°14′ E), Beijing, China. This system site is on a clay loam (0–0.20 m soil) with a pH (soil–water ratio of 1:5) of 8.4 and contains 14.10 g·kg−1 organic C, 0.82 g·kg−1 total N, 19.97 mg·kg−1 available phosphorus, and 79.77 mg·kg−1 ammonium acetate extractable potassium. The CAAS-FACE system includes six elevated CO2 (550 ± 17 µmol·mol−1) and six ambient CO2 octagonal plots (415 ± 16 µmol·mol−1), each with a diameter of 4 m. The carbon dioxide concentrations of each plot were measured by sensors (Vaisala, Vantaa, Finland) at the center of each octagonal plot, during the experimental season. The experimental plots were separated by at least 14 m to minimize cross-contamination of CO2 between experimental treatments. Cross-contamination was minimal, according to a comparison of the CO2 concentrations in ambient plots with and without the release of CO2 gas to elevated plots (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mini-free air carbon dioxide enrichment system of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-FACE system) in Changping, Beijing, China.

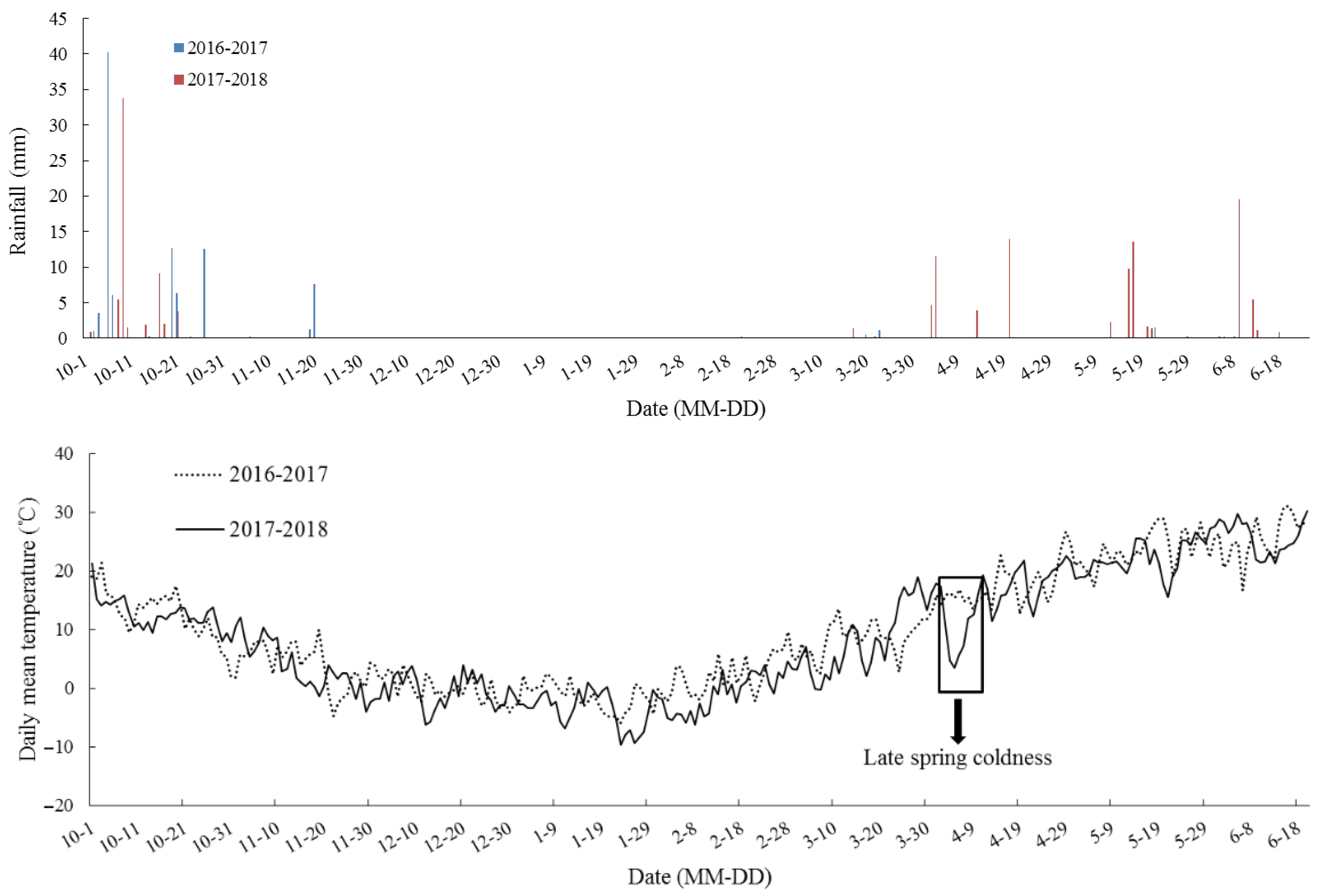

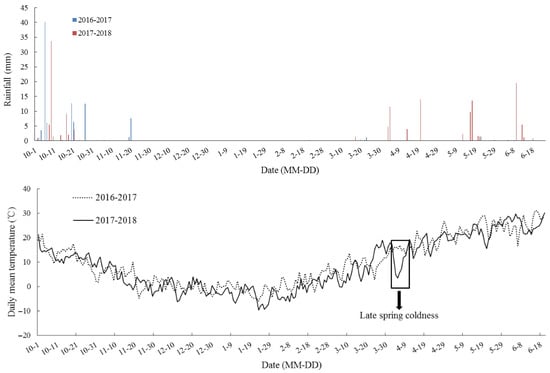

In the eCO2 treatment, carbon dioxide exposure commenced one week after sowing and terminated at maturity, and CO2 was maintained at 550 ± 17 µmol·mol−1 from 6:00 to 19:00 h. The experiments were carried out during two growing seasons, from 2016 to 2018. According to the climatic database, the rainfall of two winter wheat growing seasons from 2016 to 2018 was 98.1 mm and 149.4 mm, respectively, and the corresponding mean temperature was 9.7 °C and 8.5 °C at this location (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Rainfall (mm) and daily temperature (°C) at the wheat–maize rotation CAAS-FACE system in Changping from the sowing of winter wheat until maturity in 2016–2018, two continuous contrasting experiment years. The downward arrow indicates late spring coldness in 2018.

In this experiment, a split-plot randomized block design was adopted with 3 replications; CO2 concentration was the main treatment (aCO2, 415 ± 16 mol·mol−1 and eCO2, 550 ± 17 mol·mol−1) and winter wheat cultivar was the sub-treatment.

2.2. Plant Material and Fertilization

In this research, Triticum aestivum L. cv. Shaanhan 8675 and Triumph were chosen for this research. Shaanhan 8675 is a wheat cultivar developed by the Shaanxi Provincial Wheat Research Institute, with its parental cross combination derived from Changwu 131 and Xizhi 81206. Owing to its excellent yield performance, this cultivar has been extensively utilized in wheat cross-breeding programs. Triumph is an early-introduced American wheat cultivar whose genetic background harbors desirable agronomic traits, such as strong stress tolerance and large population capacity. Owing to its excellent comprehensive agronomic traits, this cultivar has become one of the core genetic resources for wheat breeding in China. According to the ear traits and the ratio of harvest index (HI), Shaanhan 8675 is regarded as a large-ear cultivar (Table 1). In contrast, the ear size of Triumph is relatively small as a multiple-ear type when compared with Shaanhan 8675 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ear traits and the ratio of harvest index of two cultivars.

Each plot area was 6 m2. The seeding rate was determined according to the 1000-grain weight of each cultivar to ensure the basic seedlings of each cultivar at 300 plants per square meter. The drill sowing method was adopted to sow 6 rows in each plot with a row spacing of 20 cm. Granular urea (N, 46%), diammonium phosphate (N:P2O5 = 13%:44%), and potassium chloride (K2O, 60%) were applied as basal fertilizer at equal rates of 100 kg N·hm−2, 165 kg P2O5·hm−2, and 90 kg K2O·hm−2. At the stage of jointing on 28 April 2017 and 2018, granular urea at a rate of 100 kg N·hm−2 was applied as a side dressing. Irrigation was applied twice during the whole growing season of winter wheat: the overwintering irrigation at a quantity of 750 m3·hm−2 on 23 November 2016 and 2017, and the spring irrigation at a quantity of 750 m3·hm−2 of water at the jointing stage after side dressing fertilization.

2.3. Crop Measurements

2.3.1. Light-Saturated Maximum Gross CO2 Assimilation Rate

Light-saturated net CO2 assimilation rate (Ag,max, μmol·m−2s−1) measurements were performed on the latest fully expanded leaf from three individual plants of each treatment on sunny days between 9:00 and 11:30 a.m. at the jointing, anthesis, and grain-filling stages. The measurements were taken using an LI-6400 portable photosynthesis system (LiCor-6400XT, LI-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA). Settings in the leaf chamber are as follows: CO2 concentration was set at 415 μmol·mol−1 in aCO2 treatments and 550 μmol·mol−1 in eCO2 treatments, respectively; the photosynthetic active radiation was set to 1200 μmol·m−2s−1; the temperature inside the leaf chamber was set to a temperature consistent with the ambient atmospheric temperature.

2.3.2. NSC Measurement and Calculation

Plants were sampled at the anthesis stage, destructive sampling was performed on a 20 cm2 area of plants within each CO2 treatment, and after removing the soil from the roots, all the plants were separated according to the number of single stems. The number of plants and stems was recorded and converted to the number of plants and stems per unit area, and then 20 plants were taken according to the ratio of plants with different numbers of single stems to the total number of plants in the sample as the plant samples for the NSC measurement and calculation. Plant samples were separated into the leaf, stem, and ear (glumes and ear-stalks), and deactivated at 150 °C for 30 min, then dried at 80 °C to a constant weight. Samples were then ground and filtered through a 0.5 mm sieve to prepare the powdered material for NSC measurement. Soluble sugar contents were analyzed using an anthrone reagent according to the method from Mustroph et al. (2006) [13]. Sucrose content (SC) and starch content were measured using a resorcinol reagent and a 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid colorimetry reagent according to the procedures described by Wang et al. (2019) [14] and the adoption of a multimode microplate reader (Infinite 200 PRO Nano Quant, Tecan) to measure spectrophotometrically. The starch content was calculated as mg g−1 dry weight [15]. In this study, the sums of sugars and starch concentrations were estimates of NSC [16]. The transfer of organ NSC parameters were calculated according to the following equations [16,17]:

Organ NSC accumulation (TMNSC g·m−2) = Organ dry weight × Organ NSC content

Organ NSC partitioning index (%) = (Organ NSC accumulation/Plant NSC accumulation) × 100%

Apparent transferred mass of organ NSC (ATMNSC, g·m−2) = Organ NSC accumulation at anthesis − Organ NSC accumulation at maturity

Apparent ratio of transferred NSC from organ (ARNSC,%) = (Apparent transferred mass of organ NSC/Organ NSC accumulation at anthesis) × 100

Apparent contribution of transferred organ NSC to grain yield (ACNSC) = Apparent transferred mass of organ/Dry grain weight × 100

2.3.3. Measurement of Kernel Number and Kernel Weight

Wheat plant samples were collected at the ripening stage from six rows of 3 m length in the center of each plot were harvested at ground level to minimize edge effects. Separating all wheat ears from the plants, and all ears were dried in an oven at 105 °C for 30 min, and then at 80 °C until constant weight. Twenty ears were randomly selected from each experimental plot at the maturity stage, and three kernel-related traits were determined for each sampled ear: total kernel number, number of degenerated kernels, and number of fully filled kernels. The kernel number in each ear of these twenty individuals was recorded, and the kernel number per ear of every treatment was the mean kernel number for each ear of the 20 harvested individuals. After this, all the ears were threshed, and kernels were soaked in tap water of 1.00 specific gravity, and the number of degenerated kernels and filled kernels was recorded. All kernels were weighed after drying at 70 °C to constant weight, and the weight of each kernel and the kernel weight per ear were recorded.

2.4. Data Statistical Processing

Statistical analyses for all data generated in this study were performed using SPSS 18.0 version data statistical software and Excel 2016. The experiment was designed as a split-plot with the whole plots arranged in randomized complete blocks; levels of CO2 (ambient or elevated CO2) were the whole-plot treatment, and wheat cultivars were the split-plot treatment. A general linear model was used to estimate the main effects of CO2 and cultivars, as well as their interactions. ANOVA was used to test for statistical significance to determine differences between treatment means. The least significant difference (LSD) at p < 0.05 was used to compare the means between CO2 concentration and cultivar treatments.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Elevated CO2 on the Kernels of the Ear at the Ripening Stage

Elevated CO2 reduced the amount of degenerated kernels per ear of Shaanhan 8675 by 27.7% and 22.9% (p < 0.05) across two years, but increased filled kernels per ear by 9.3% and 9.8% (p < 0.05) (Table 2). However, in 2018, eCO2 increased the degenerated kernels per ear of Triumph while decreasing the filled kernels per ear by 12.1% (p < 0.05) (Table 2). When CO2 concentration increased to 550 µmol·mol−1, Shaanhan 8675 produced fewer degenerated kernels per ear than Triumph, while the results for filled kernels per ear were the opposite (Table 2). CO2 × cultivar interaction was detected for the kernel weight per ear and kernel weight per square meter. Elevated CO2 increased the kernel weight per ear and kernel weight per square meter of Shaanhan 8675 by an average of 13.4% and 25.6% (p < 0.05) across two years. However, eCO2 had no significant effect on kernel weight per ear or kernel weight per square meter of Triumph. Therefore, under the eCO2 treatment, these parameters of Shaanhan 8675 were an average of 45.3% and 38.7% (p < 0.05) higher than Triumph throughout the course of two years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of elevated CO2 on the kernels of the ear and kernel weight at the ripening stage.

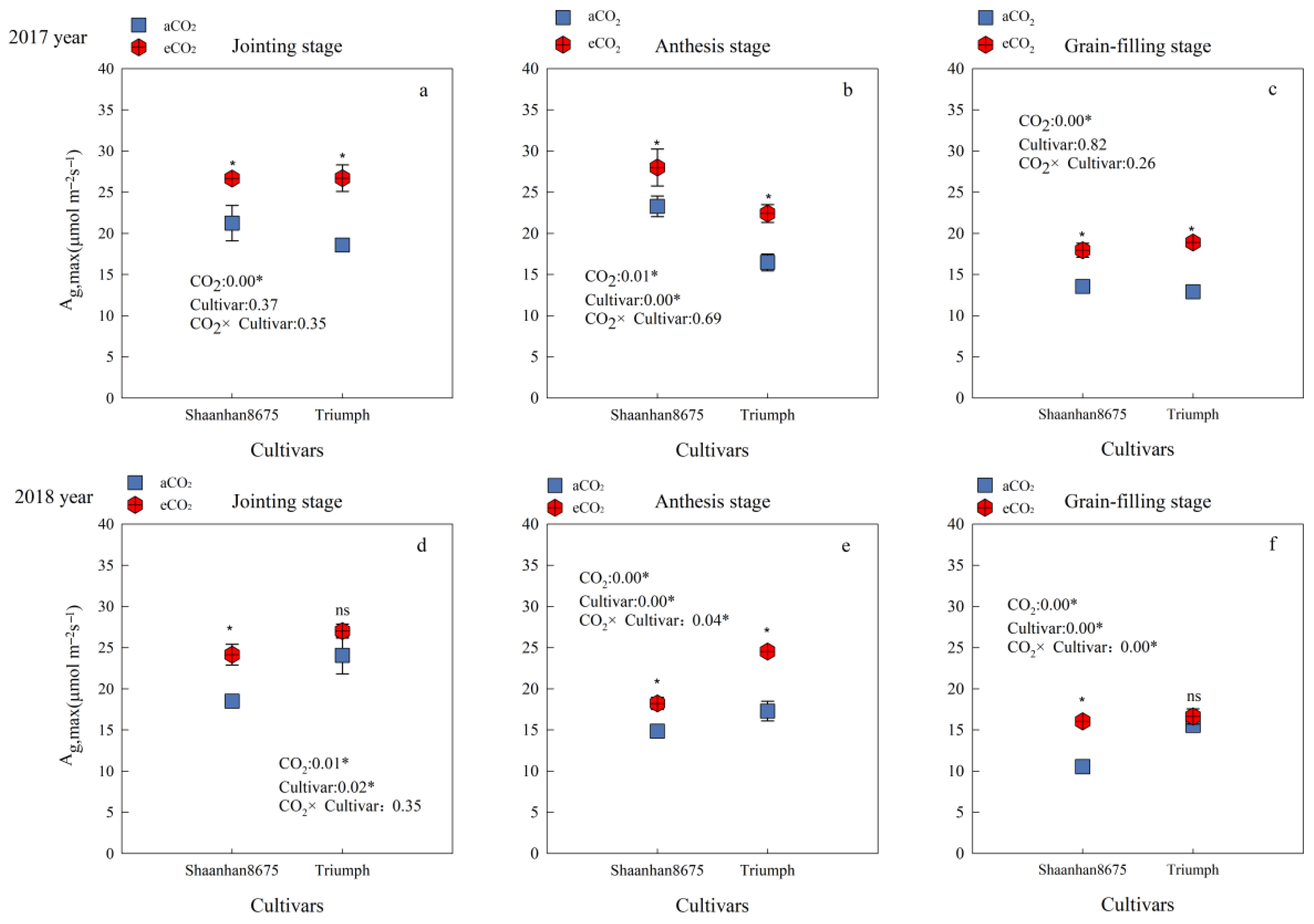

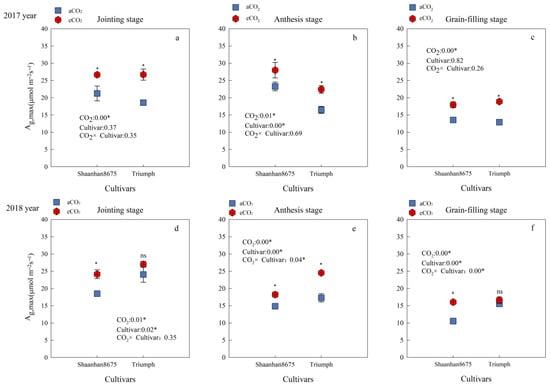

3.2. Light-Saturated Maximum Gross Photosynthetic Rate

Averaged across the jointing, anthesis, and grain-filling stages, eCO2 increased the Ag,max of Shaanhan 8675 by 26.1% and 35.2%, respectively, over the two years. eCO2 increased the Ag,max of Triumph by 42.1% (p < 0.05), averaged across the three key growth stages in 2017. However, in 2018, the Ag,max of Triumph increased by 41.9% (p < 0.05) only at the anthesis stage (Figure 3e). Cultivar differences showed that in 2017, the Ag,max of Shaanhan 8675 was higher than that of Triumph at the anthesis stage under eCO2 treatments (Figure 3b). However, the results were reversed in 2018 (Figure 3e).

Figure 3.

Effects of elevated CO2 on the Ag,max (μmol·m−2s−1) at three key growth stages of two winter wheat cultivars grown under either ambient CO2 (aCO2, 415 µmol·mol−1) or elevated CO2 (eCO2, 550 µmol·mol−1). Measurements were carried out on the last fully expanded leaf. Data represent the mean of three plants from each cultivar pot ± SD (standard error) bars. ANOVA results are also shown with * and ns indicating p < 0.05 and no significance, respectively. (a) 2017 year Jointing stage, (b) 2017 year Anthesis stage, (c) 2017 year Grain-filling stage, (d) 2018 year Jointing stage, (e) 2018 year Anthesis stage, (f) 2018 year Grain-filling stage.

3.3. NSC Accumulation and Allocation of Different Plant Tissues at the Anthesis Stage

There were significant interactions between CO2 and the cultivar for TMNSC (Table 3). Except for the TMNSC in the ear of Shaanhan 8675 in 2018, eCO2 significantly increased the TMNSC of Shaanhan 8675 organs in both years. As for Triumph, eCO2 increased TMNSC in the leaf by 43.5% (p < 0.05) in 2018 only (Table 3). When CO2 increased to 550 µmol·mol−1, TMNSC in the stem and ear of Shaanhan 8675 was significantly higher than that of Triumph across two years.

Table 3.

Effects of elevated CO2 on NSC accumulation and partitioning index of plant tissues at the anthesis stage.

Elevated CO2 significantly reduced PINSC in the stem but increased PINSC in the ear of Shaanhan 8675 in 2017. Elevated CO2 significantly increased the PINSC in the leaf but decreased the PINSC in the ear of Triumph in 2018. Cultivar difference results showed that the PINSC of Triumph leaf was higher than that of Shaanhan 8675 under eCO2 treatments in both years, whereas the PINSC of ear was opposite.

3.4. Sucrose Content and the Ratio of Sucrose to NSC of Organs at the Anthesis Stage

Elevated CO2 significantly increased the SC and the ratio of sucrose to NSC (RS) of Shaanhan 8675 organs in both years (Table 4). As for Triumph, eCO2 significantly decreased the SC and RS in the leaf and the stem in 2017. However, elevated CO2 increased the RS in the ears of Triumph across two experimental seasons (Table 4). The results of cultivar differences indicate that, when CO2 increased to 550 µmol·mol−1, except for the RS of the ears in 2018, the SC and RS of Shaanhan 8675 organs were significantly higher than those of Triumph in both years (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of elevated CO2 on sucrose content and the ratio of sucrose to NSC at the anthesis stage.

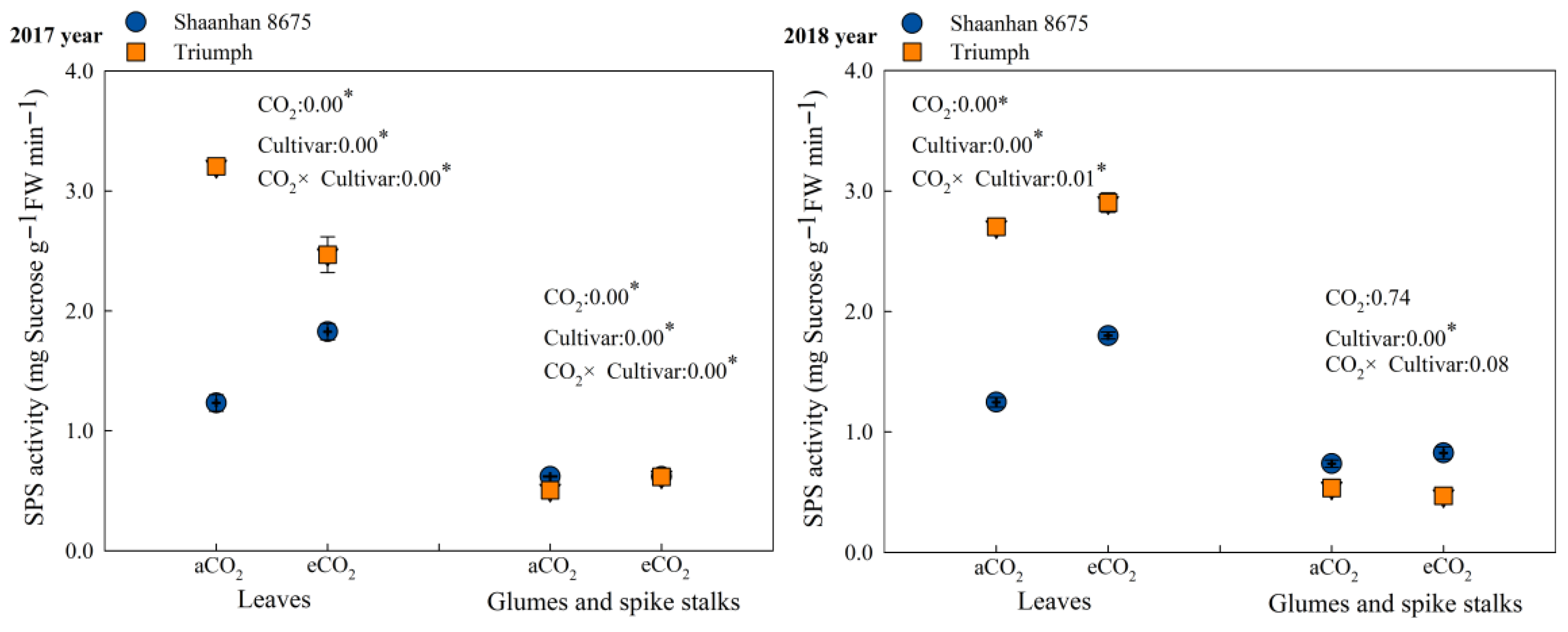

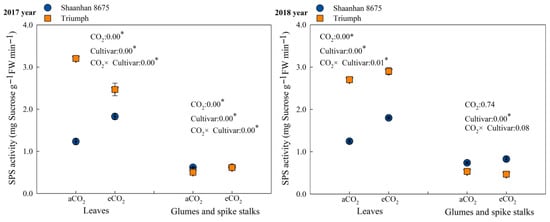

3.5. Effects of Elevated CO2 on SPS Activity in Leaves at the Anthesis Stage

Elevated CO2 concentration upregulated the activity of sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) (Figure 4) and significantly increased sucrose content in the leaves of Shaanhan 8675 at the anthesis stage (Table 3). This indicates that elevated CO2 promoted photosynthetic carbon assimilation in Shaanhan 8675 leaves during the flowering period and enhanced the storage of photosynthetic carbon assimilates in the form of sucrose. Consequently, this led to increased carbon export to sinks, thereby facilitating panicle development and reducing the number of abortive spikelets. In contrast, elevated CO2 exerted a downregulatory effect on SPS activity in the leaves of Triumph (Figure 4). This promoted sucrose degradation and starch synthesis, resulting in decreased sucrose content in Triumph leaves (Table 3). As a result, the export of photosynthetic carbon assimilates to sinks was reduced, which was unfavorable for panicle development.

Figure 4.

Effects of elevated CO2 on SPS (sucrose phosphate synthase) activity at the anthesis stage in the leaves of two winter wheat cultivars grown under either ambient CO2 (aCO2, 415 µmol·mol−1) or elevated CO2 (eCO2, 550 µmol·mol−1). Data represent the mean of three plants from each cultivar pot ± SD (standard error) bars. ANOVA results are also shown with * indicating p < 0.05.

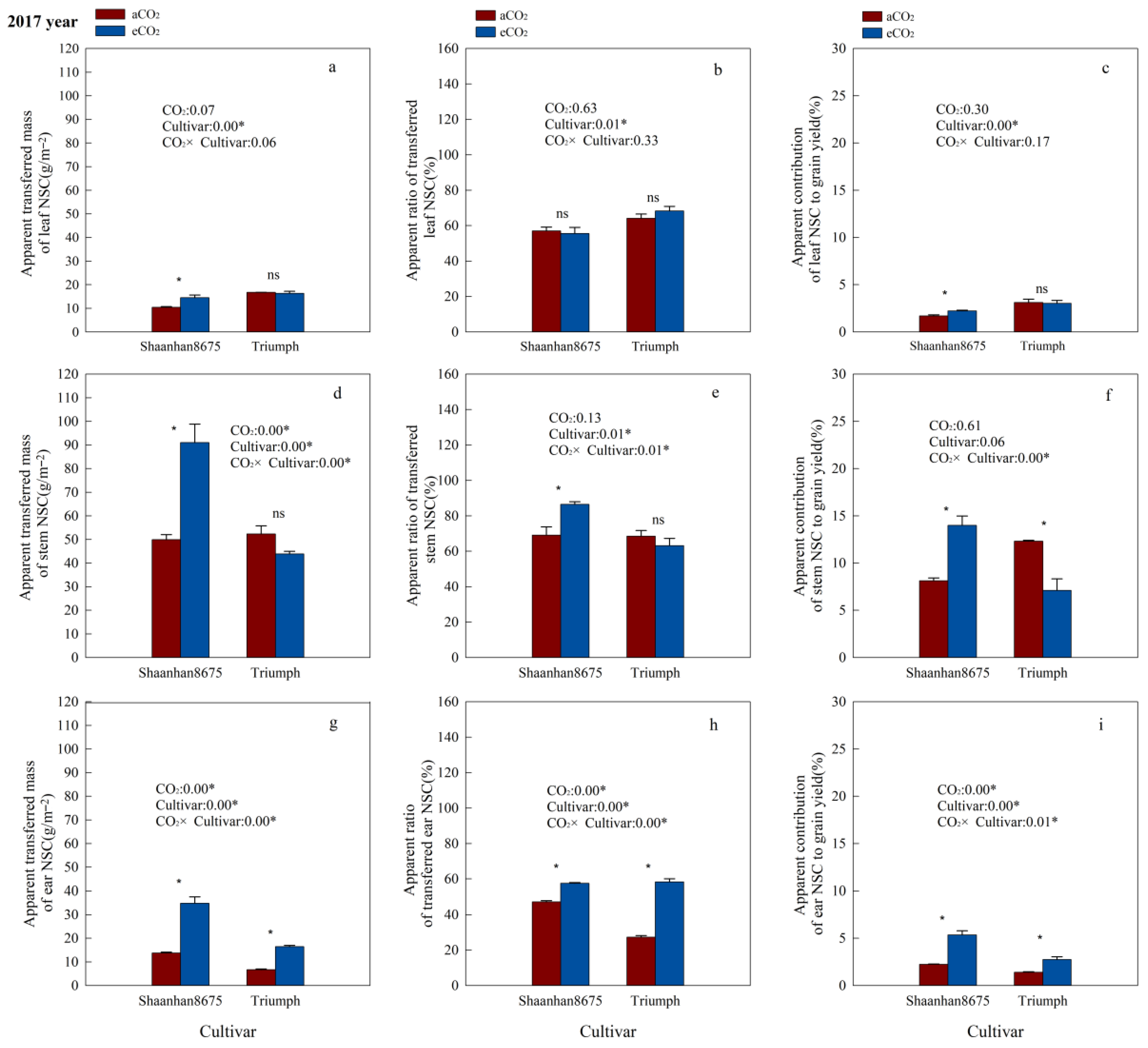

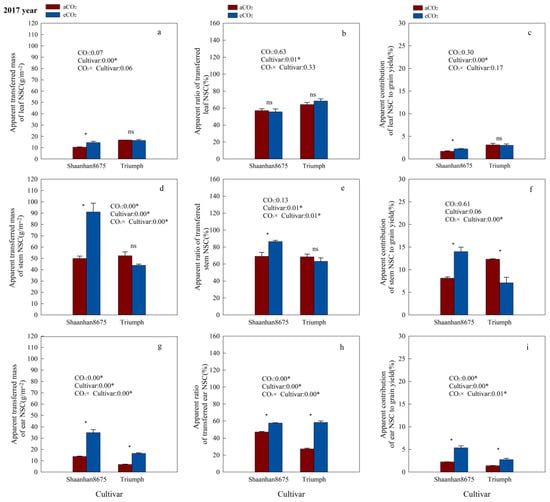

3.6. Effects of Elevated CO2 on the Contribution of NSC in Plant Tissues to Grain Yield

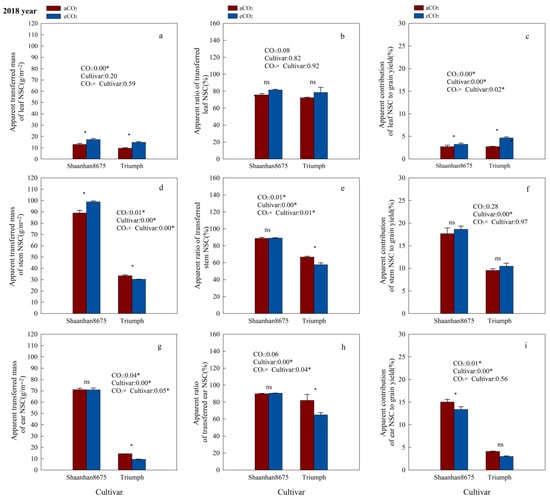

Elevated CO2 significantly increased the ATMNSC and ACNSC in leaves of Shaanhan8675 in both years (Figure 5a,c and Figure 6a,c), and significantly increased the ATMNSC, ARNSC, and ACNSC in stems and ears of Shaanhan 8675 in 2017 (Figure 5a,c,d–i). However, except for the stem ATMNSC, which was significantly increased by eCO2 (Figure 6d), we did not observe any significant effect of eCO2 on NSC translocation parameters in the stems and ears of Shaanhan 8675 in 2018 (Figure 6e–h). Furthermore, eCO2 increased ATMNSC, ARNSC, and ACNSC in the ears of Triumph by 145.3%, 114.1%, and 96.5% (p < 0.05) in 2017 (Figure 5g–i). In contrast, elevated CO2 in 2018 significantly decreased the ATMNSC and ARNSC in the ears and stems of Triumph (Figure 6d,e,g,h).

Figure 5.

Effects of elevated CO2 on the ATMNSC (apparent transferred mass of organ NSC), ARNSC (apparent ratio of transferred NSC from organ), and ACNSC (apparent contribution of transferred organ NSC to grain yield) of organs in two winter wheat cultivars grown under either ambient CO2 (aCO2, 415 µmol·mol−1) or elevated CO2 (eCO2, 550 µmol·mol−1) in 2017. Data represent the mean of three plants from each cultivar pot ± SD (standard error) bars. ANOVA results are also shown, with * indicating p < 0.05 and ns indicating no significance. (a) Apparent transferred mass of leaf NSC (g/m−2); (b) Apparent ratio of transferred leaf NSC (%); (c) Apparent contribution of leaf NSC to grain yield (%); (d) Apparent transferred mass of stem NSC (g/m−2); (e) Apparent ratio of transferred stem NSC (%); (f) Apparent contribution of stem NSC to grain yield (%); (g) Apparent transferred mass of ear NSC (g/m−2); (h) Apparent ratio of transferred ear NSC (%); (i) Apparent contribution of ear NSC to grain yield (%).

Figure 6.

Effects of elevated CO2 on the ATMNSC (apparent transferred mass of organ NSC), ARNSC (apparent ratio of transferred NSC from organ), and ACNSC (apparent contribution of transferred organ NSC to grain yield) of organs in two winter wheat cultivars grown under either ambient CO2 (aCO2, 415 µmol·mol−1) or elevated CO2 (eCO2, 550 µmol·mol−1) in 2018. Data represent the mean of three plants from each cultivar pot ± SD (standard error) bars. ANOVA results are also shown, with * indicating p < 0.05 and ns indicating no significance. (a) Apparent transferred mass of leaf NSC (g/m−2); (b) Apparent ratio of transferred leaf NSC (%); (c) Apparent contribution of leaf NSC to grain yield (%); (d) Apparent transferred mass of stem NSC (g/m−2); (e) Apparent ratio of transferred stem NSC (%); (f) Apparent contribution of stem NSC to grain yield (%); (g) Apparent transferred mass of ear NSC (g/m−2); (h) Apparent ratio of transferred ear NSC (%); (i) Apparent contribution of ear NSC to grain yield (%).

Additionally, we observed notable cultivar variations in NSC translocation parameters at the 550 µmol·mol−1 CO2 concentration. Shaanhan 8675 leaves had lower ATMNSC, ARNSC, and ACNSC compared to Triumph in 2017 (Figure 5a–c). Nonetheless, the ATMNSC, ARNSC, and ACNSC of Shaanhan 8675 stems and ears were higher than those in the stems and ears of Triumph in both years (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

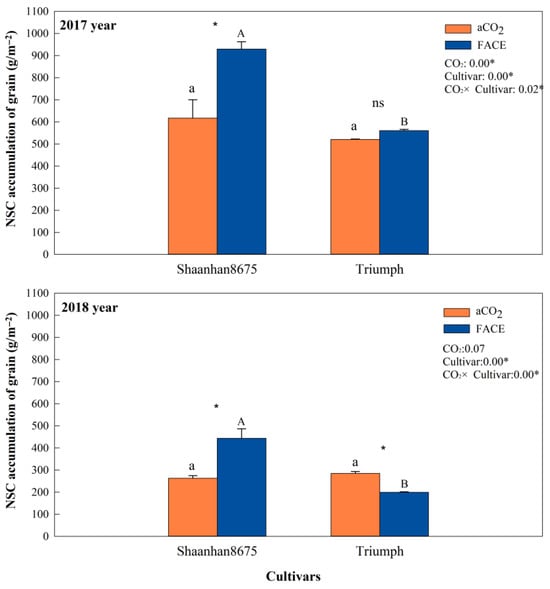

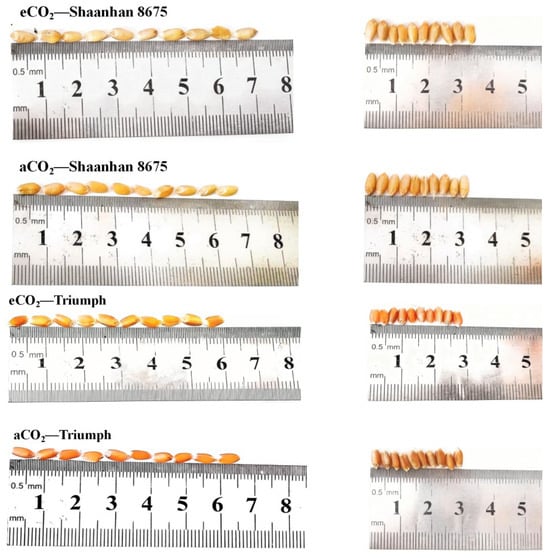

3.7. Effects of Elevated CO2 on Grain NSC Accumulation at Ripening Stage

Elevated CO2 increased grain NSC accumulation in Shaanhan 8675 by 50.6% and 69.0% across two years (Figure 7). Regarding the multiple-ear cultivar Triumph, eCO2 decreased grain NSC accumulation (30.0%, p < 0.05) in 2018. When CO2 concentration increased to 550 µmol·mol−1, the grain NSC concentration of Shaanhan 8675 was significantly higher than that of Triumph across two years. In Figure 8, the grain photographs of the two cultivars also demonstrate that elevated CO2 exerted significantly different effects on the two ear-type cultivars.

Figure 7.

Effects of elevated CO2 on NSC (non-structural carbohydrate) accumulation of grain in two winter wheat cultivars grown under either ambient CO2 (aCO2, 415 µmol·mol−1) or elevated CO2 (eCO2, 550 µmol·mol−1) in 2017 and 2018. Data represent the mean of three plants from each cultivar pot ± SD (standard error) bars. Upper- and lower-case letters within each treatment indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between cultivars under the eCO2 and aCO2 treatments. ANOVA results are also shown, with * indicating p < 0.05 and ns indicating no significance.

Figure 8.

Effects of elevated CO2 on grain in two winter wheat cultivars grown under either ambient CO2 (aCO2, 415 µmol·mol−1) or elevated CO2 (eCO2, 550 µmol·mol−1). Grain photographs of Shaanhan 8675 and Triumph captured from horizontal and vertical angles.

3.8. Correlation Analyses

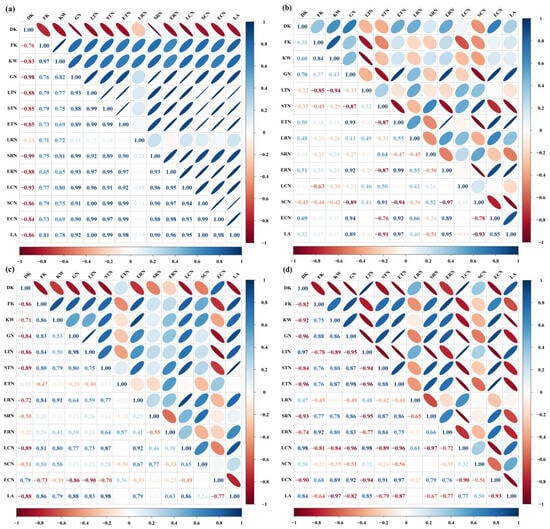

Elevated CO2 significantly enhanced the kernel weight of Shaanhan 8675 (Table 2). To identify the primary drivers behind this yield improvement, correlation analyses were conducted. The results revealed a significant positive relationship between kernel weight and grain NSC accumulation. Furthermore, grain NSC accumulation was positively correlated with the ATMNSC, ARNSC, and ACNSC in various organs, as well as with the Ag,max of the flag leaf during the grain-filling period (Figure 9a,c). However, eCO2 did not exert a significant effect on the kernel weight of Triumph (Table 2). Correlation analysis indicated that grain NSC accumulation in Triumph was positively associated with the ATMNSC, ARNSC, and ACNSC of the ear, as well as the Ag,max of the flag leaf during the grain-filling period. Notably, no significant correlation was found between kernel weight and grain NSC accumulation (Figure 9b). Grain NSC accumulation was positively correlated with the ATMNSC, ARNSC, and ACNSC of the ear, as well as the ATMNSC and ARNSC of the stem (Figure 9d).

Figure 9.

Correlation analysis between the grain NSC accumulation and NSC transfer-related parameters in 2017 (a,b) and 2018 (c,d). Positive values > 0.80 and negative values > −0.80 indicate a significant positive and negative correlation between the parameters, respectively. DK—degenerated kernels ear−1; FK—filled kernels ear−1; KW—kernel weight ear−1; GN—grain NSC accumulation; LTN—apparent transferred mass of leaf NSC; STN—apparent transferred mass of stem NSC; ETN—apparent transferred mass of ear NSC; LRN—apparent ratio of transferred NSC from leaf; SRN—apparent ratio of transferred NSC from stem; ERN—apparent ratio of transferred NSC from ear; LCN—apparent contribution of transferred leaf NSC to grain yield; SCN—apparent contribution of transferred stem NSC to grain yield; ECN—apparent contribution of transferred ear NSC to grain yield; LA—light-saturated net CO2 assimilation rate of flag leaves during the grain-filling period.

4. Discussion

Understanding how crop genotypes interact with rising atmospheric CO2 to modulate carbon metabolism and yield formation is central to breeding climate-resilient wheat [18]. Recent evidence highlighted that ear architecture critically influences grain yield potential, primarily by shaping sink strength and carbohydrate partitioning efficiency [19]. Large-ear cultivars, characterized by fewer but larger spikes with high assimilate demand per ear, were hypothesized to benefit more from CO2 fertilization due to their enhanced capacity for carbon accumulation and remobilization [20,21]. Using a two-year FACE experiment, we tested this hypothesis by comparing the physiological responses of a large-ear (Shaanhan 8675) and a multiple-ear (Triumph) wheat cultivar under ambient (aCO2, ~415 µmol·mol−1) and elevated CO2 (eCO2, ~550 µmol·mol−1).

4.1. The Effects of Elevated CO2 on Carbon Metabolism

The large-ear wheat cultivar Shaanhan 8675 exhibited consistent responsiveness to eCO2 across varying inter-annual meteorological conditions. Elevated CO2 significantly enhanced the Ag,max and NSC accumulation in various organs of Shaanhan 8675 over both experimental years. Concurrently, eCO2 significantly increased the SC in all organs, establishing a strong physiological basis for efficient NSC translocation [22]. Crucially, eCO2 upregulated SPS activity in Shaanhan 8675 leaves, promoting sucrose synthesis and facilitating phloem loading. Consequently, pre-anthesis NSC reserves, particularly in stems and ears, were efficiently remobilized during the grain-filling phase [23], as evidenced by significant increases in ATMNSC, ARNSC, and ACNSC. This robust source–sink coordination translated into 50.6% and 69.0% higher grain NSC accumulation, reduced spikelet abortion, and a 13.4% and 25.6% increase in kernel weight across years. These findings align with previous studies showing that eCO2 enhances carbon assimilation and carbohydrate accumulation in C3 plants [22], thereby promoting more effective carbon redistribution [24]. In contrast, Triumph exhibited highly variable responses contingent on inter-annual environmental conditions. In 2017, despite the moderate stimulation of Ag,max, NSC accumulation in vegetative organs was limited. Instead, SC and the RS declined in leaves and stems, possibly because of feedback inhibition or greater respiratory carbon loss [25]. These effects may have been worsened by Triumph’s high tiller number and complex canopy. Sucrose serves as the main form of carbohydrate storage and transport in wheat organs [26]. Adequate sucrose levels are essential for maintaining osmotic balance during the translocation of carbohydrates from source to sink tissues [27]. Therefore, the ears of Triumph exhibited higher NSC translocation efficiency under eCO2 conditions. However, although ear RS increased, grain NSC accumulation and yield showed no significant improvement. In 2018, a year with higher precipitation during the grain-filling period, eCO2 failed to enhance flag leaf Ag,max during the grain-filling period, and instead, reduced NSC translocation from stems and ears. This led to a 30.0% decline in grain NSC and a significant increase in degenerated kernels, ultimately decreasing kernel weight. The observed differences in Ag,max between the two years may be explained by environmental variability. In 2018, the Ag,max of Triumph flag leaves under aCO2 conditions was higher than that in 2017, resulting in a smaller relative enhancement under eCO2, and thus, a nonsignificant difference when compared to 2018. This phenomenon could be influenced by higher precipitation during the grain-filling period in 2018 compared to 2017. Increased soil moisture can alter plant water use efficiency and indirectly affect leaf net photosynthetic rates [28]. For winter wheat grown under long-term eCO2 conditions, soil moisture status may modulate the magnitude of the CO2 fertilization effect [29]. Additionally, different cultivars exhibited varied responses to eCO2 and other environmental factors [30], which likely explains why the performance trend of Shaanhan 8675 differed from that of Triumph. The differing responses of Triumph across the two years highlight a key limitation of the multiple-ear strategy; although beneficial under favorable conditions, it is more sensitive to environmental variability under elevated CO2, likely due to poor coordination between source and sink tissues and less efficient carbon redistribution.

4.2. Intraspecific Variation in Response to Elevated CO2

Intraspecific variation in crop responses to eCO2 has been widely documented [6]. Our findings demonstrate that ear architecture fundamentally modulates wheat’s responsiveness to eCO2 through the integrated regulation of photosynthesis, NSC metabolism, and sink development. Under an eCO2 environment, Shaanhan 8675 consistently exhibited higher NSC and sucrose levels in stems and ears than Triumph, along with superior NSC translocation parameters (ATMNSC, ARNSC, and ACNSC). This finding aligns with previous studies showing that effective grain filling depends largely on the efficient transport of sucrose from source to sink tissues [31]. The greater increase in grain NSC concentration observed in Shaanhan 8675 compared to Triumph can be attributed to the superior NSC translocation efficiency in its stems and ears (Figure 6). Thus, efficient NSC transport within stems and ears appears to be a key determinant of improved grain-filling performance in wheat. This supports earlier findings that the remobilization of pre-anthesis NSC reserves stored in stems is a primary mechanism driving grain filling [32]. Moreover, prior research has confirmed that photosynthesis in the ears contributes significantly to the carbohydrate pool translocated to developing grains during the grain-filling period [33]. Under eCO2 conditions (550 µmol·mol−1), Shaanhan 8675 exhibited higher grain NSC concentrations than Triumph. Enhanced grain NSC accumulation facilitates the reduction in degenerated kernels and promotes the formation of more filled kernels per ear [34]. As a result, Shaanhan 8675 had fewer degenerated kernels and more filled kernels compared to Triumph (Table 2). The increased number of filled kernels contributed to Shaanhan 8675 achieving significantly higher kernel weight across both experimental years. Correlation analyses further clarified these divergences; in Shaanhan 8675, kernel weight was strongly and positively linked to grain NSC accumulation, which in turn correlated with the ATMNSC, ARNSC, and ACNSC in the stems and ears and with the flag leaf Ag,max during the grain-filling stage. In Triumph, however, no such relationship existed between the grain NSC and kernel weight in either year, implying a decoupling between carbon supply and grain-filling efficiency, likely due to insufficient sink strength or impaired translocation pathways. This physiological advantage facilitated more efficient carbon allocation to grains, reducing spikelet degeneration and increasing the number of filled kernels, both of which were key drivers of its yield gain. This conclusion corroborates previous reports showing that wheat cultivars with high kernel weight tend to store more NSC in stems before anthesis and exhibit higher NSC levels per spikelet [32].

4.3. Implications and Limitations

Collectively, our study provides compelling evidence that selecting large-ear wheat cultivars with strong sink capacity and efficient NSC remobilization traits can enhance yield stability and responsiveness under elevated CO2 scenarios. This supports a strategic shift toward optimizing ear architecture in breeding programs targeting climate resilience. It is important to acknowledge certain limitations of this study. A primary limitation lies in the methodology used to assess CO2 assimilation rates. In this work, net CO2 assimilation rates were measured using an LI-6400XT portable photosynthesis system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). However, as leaf respiration was not simultaneously measured, the data obtained reflect only net photosynthesis and not gross CO2 assimilation rates. This introduces a potential bias in our photosynthetic measurements and limits our ability to definitively determine which of the two wheat cultivars exhibited superior photosynthetic performance under elevated CO2 conditions. Future studies should, therefore, incorporate measurements of dark respiration to enable more accurate estimation of gross CO2 assimilation. Additionally, the number of wheat cultivars included in this study was limited. Only two cultivars, Triticum aestivum L. cv. Shaanhan 8675 (a large-ear type) and cv. Triumph (a multiple-ear type), was examined. The use of just one representative cultivar per ear type constrains the generalizability of the findings and may limit the representativeness of the results across broader genetic backgrounds. Despite these limitations, the current study provides valuable insights into how different ear types respond to elevated CO2, particularly in terms of NSC dynamics and grain filling. To build upon these findings, future research will focus on expanding the number of cultivars evaluated, including additional large-ear and multiple-ear wheat types, to better capture intraspecific variability and enhance the reliability and applicability of the conclusions.

5. Conclusions

In our case, the increase in grain NSC concentration and kernel weight of the large-ear wheat cultivar Shaanhan 8675 showed consistent stability across different inter-annual meteorological conditions. This consistency can be attributed to enhanced NSC accumulation and translocation in its vegetative organs under eCO2. Furthermore, eCO2 improved both the efficiency of NSC accumulation and its transport within Shaanhan 8675, which helped maintain a higher photosynthetic rate in the flag leaf during the grain-filling period. This sustained photosynthetic capacity contributed to more effective grain filling. Additionally, under eCO2 conditions, Shaanhan 8675 consistently exhibited higher grain NSC concentrations and kernel weights than Triumph across both experimental years. This was primarily due to greater NSC accumulation and more efficient redistribution from stems and ears in Shaanhan 8675 compared to Triumph. These results indicate that Shaanhan 8675 exhibited a positive physiological response to eCO2, particularly in terms of photosynthetic efficiency and carbon metabolism. In contrast, the multiple-ear cultivar Triumph showed variability in physiological responses between years, likely influenced by inter-annual climatic differences. These findings support our hypothesis that CO2 enrichment has a significant positive effect on NSC availability and remobilization from source organs to grains in the large-ear wheat cultivar Shaanhan 8675. This study provides valuable insights for future wheat breeding programs aimed at developing cultivars adapted to elevated CO2 environments. It highlights the potential to exploit the beneficial effects of climate change on wheat productivity through the selection and cultivation of genotypes with improved carbon utilization efficiency under future atmospheric conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.X. and Y.L.; methodology, Y.L.; software, Y.L., H.Y. and Y.X.; validation, Y.L. and H.Y.; formal analysis; investigation, B.S.; resources, H.X., Y.L. and Z.Z.; data curation, Y.L. and Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. and H.X.; visualization, Y.L., H.Y. and Q.W.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by CAAS Center for Science in Agricultural Green and Low Carbon (CAAS-CSGLCA-202301), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP) from Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and China’s 14th National Key R&D Program project (2023YFF0805900).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fahad, S.; Khan, F.A.; Pandupuspitasari, N. Suppressing photorespiration for the improvement in photosynthesis and crop yields:A review on the role of S-allantoin as a nitrogen source. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 237, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture. Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Khan, A.; Lv, Z. Effect of multigenerational exposure to elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration on grain quality in wheat. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 157, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dier, M.; Sickora, J.; Erbs, M. Positive effects of free air CO2 enrichment on N remobilization and post-anthesis N uptake in winter wheat. Field Crops Res. 2019, 234, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, O.; Hlavacova, M.; Klem, K. Combined effects of drought and high temperature on photosynthetic characteristics in four winter wheat genotypes. Field Crops Res. 2018, 223, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.; Gamage, D.; Ratnasekera, D. Effect of elevated carbon dioxide on plant biomass and grain protein concentration differs across bread, durum and synthetic hexaploidy wheat genotypes. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 87, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asseng, S.; Kassie, B.T.; Labra, M.H.; Amador, C.; Calderini, D.F. Simulating the impact of source-sink manipulations in wheat. Field Crops Res. 2017, 202, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, D. An indica rice genotype showed a similar yield enhancement to that of hybrid rice under free air carbon dioxide enrichment. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-barbero, E.L.; Pérez, P.; Martínez-carrasco, R. Screening for higher grain yield and biomass among sixty bread wheat genotypes grown under elevated CO2 and high-temperature conditions. Plants 2021, 10, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, M.K.; Sharma, N.; Adavi, S.B. From source to sink: Mechanistic insight of photoassimilates synthesis and partitioning under high temperature and elevated CO2. Plant Mol. Biol. 2022, 110, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranjuelo, I.; Cabrera-Bosquet, L.; Morcuende, R.; Perez, P. Does ear C sink strength contribute to overcoming photosynthetic acclimation of wheat plants exposed to elevated CO2? J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 3957–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba, J.; Pérez, P.; Morcuende, R. Acclimation to elevated CO2 is improved by low Rubisco and carbohydrate content, and enhanced Rubisco transcripts in the G132 barley mutant. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 137, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mustroph, A.; Boamfa, E.I.; Laarhoven, L.J.J. Organ-specific analysis of the anaerobic primary metabolism in rice and wheat seedlings. I: Dark ethanol production is dominated by the shoots. Planta 2006, 225, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Li, Q.; Tian, F. Wheat NILs contrasting in grain size show different expansion expression, carbohydrate and nitrogen metabolism that are correlated with grain yield. Field Crops Res. 2019, 241, 107564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleary, B.V.; Charmier, L.M.J.; Mckie, V.A. Measurement of starch: Critical evaluation of current methodology. Starch-Stärke 2019, 71, 1800146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Cui, K.; Wei, D. Relationships of non-structural carbohydrates accumulation and translocation with yield formation in rice recombinant inbred lines under two nitrogen levels. Physiol. Plant. 2011, 141, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Wu, B.; Gao, Y. Effects of nitrogen and phosphorus on the regulation of nonstructural carbohydrate accumulation, translocation and the yield formation of oilseed flax. Field Crops Res. 2018, 219, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.; Voss-Fels, K.P.; Messina, C.D.; Tang, T.; Hammer, G.L. Tackling G × E × M interactions to close on-farm yield-gaps: Creating novel pathways for crop improvement by predicting contributions ofgenetics and management to crop productivity. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 1625–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, H.; Li, T. TaCol-B5 modifies spike architecture and enhances grain yield in wheat. Science 2022, 376, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gaju, O.; Reynold, M.P.; Sparkes, D.L. Relationships between physiological traits, grain number and yield potential in a wheat DH population of large spike phenotype. Field Crops Res. 2014, 164, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Lu, F.; Pan, J. The effects of cultivar and nitrogen management on wheat yield and nitrogen use efficiency in the North China Plain. Field Crops Res. 2015, 171, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichert, H.; Hoegy, P.; Mora-Ramirez, I. Grain yield and quality responses of wheat expressing a barley sucrose transporter to combined climate change factors. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 5511–5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, J.; Lin, Y. Sucrose nonfermenting-1-related protein kinase 1 regulates sheath-to-panicle transport of nonstructural carbohydrates during rice grain filling. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 1694–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranjuelo, I.; Erice, G.; Sanz-Saez, A. Differential CO2 effect on primary carbon metabolism of flag leaves in durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.). Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 2780–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, M.W. Plant development and crop productivity. In Handbook of Agricultural Productivity; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 151–183. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B.; Zhang, L.; He, Z. Understanding the regulation of cereal grain filling: The way forward. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 526–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Duan, Y.; Liu, D. Physiological and transcriptome analysis of response of soybean (Glycine max) to cadmium stress under elevated CO2 concentration. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 448, 130950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Santana, T.A.; Oliveira, P.S.; Silva, L.D. Water use efficiency and consumption in different Brazilian genotypes of Jatropha curcas L. subjected to soil water deficit. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 75, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.P.; He, C.L.; Guo, L.L.; Hao, L.H.; Cheng, D.J.; Li, F.; Peng, Z.P.; Xu, M. Soil water status triggers CO2 fertilization effect on the growth of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum). Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 291, 108097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lam, S.K.; Li, P. Early-maturing cultivar of winter wheat is more adaptable to elevated [CO2] and rising temperature in the eastern Loess Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 332, 109356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Zhang, J.H.; Wang, Z.Q. Activities of fructan-and sucrose-metabolizing enzymes in wheat stems subjected to water stress during grain filling. Planta 2004, 220, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, X. Effect of non-structural carbohydrate accumulation in the stem pre-anthesis on grain filling of wheat inferior grain. Field Crops Res. 2017, 211, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Bragado, R.; Vicente, R.; Molero, G.; Serret, M.D.; Maydup, M.L.; Araus, J.L. New avenues for increasing yield and stability in C3 cereals: Exploring ear photosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2020, 56, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashiwagi, J.; Yoshioka, Y.; Nakayama, S.; Inoue, Y.; An, P.; Nakashima, T. Potential importance of the ear as a post-anthesis carbon source to improve drought tolerance in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2021, 207, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.