Abstract

Polyethylene film (PE) mulching produces substantial “white pollution,” prompting the use of biodegradable film (BF) alternatives, yet their performance in rice systems on Northeast black soils is still uncertain. We compared three BFs with different induction periods (45 d, BF45; 60 d, BF60; 80 d, BF80), PE and a no-film control (CK) to quantify their effects on soil hydrothermal conditions, rice growth, yield, grain quality, irrigation water use efficiency (IWUE) and soil C, N. Results showed that mulching increased soil temperature and soil moisture. Across the growing season, the mean soil temperature at the 0–5 cm depth under PE was 5.5% and 2.2–5.5% higher than that under CK and BFs, respectively. Specifically, compared with CK, PE increased grain yield by 31–77% and IWUE by 75–123%, while BFs improved yield by 25–73% and IWUE by 48–101%. PE only slightly outperformed BF80 in yield (by 2.3% in 2023 and 2.1% in 2024) but achieved higher IWUE (11.0–11.7%). Grain chalkiness and sensory scores under BFs were comparable to PE and better than CK. At 0–20 cm, PE increased SOC (2.3–6.8%) and the C/N ratio (0–0.8%) but reduced total nitrogen (TN) (2.7–3.9%) and total carbon (TC) (2.5–3.1%), whereas BFs increased Org-N by 0.4–4.2%, SOC by 2.9–7.1%, and TN by 0.2–0.7%, with BF80 showing the greatest stimulatory effect. Overall, BFs—particularly BF80—are promising substitutes for PE in black soil rice systems, supporting sustainable rice production with strong application potential.

1. Introduction

Global agricultural systems face the dual challenge of meeting rising food demand while reducing environmental impacts under conditions of climate change and resource scarcity [1]. Rice (Oryza sativa L.) serves as the primary dietary staple for over half the global population and is among the most water-intensive cereals, requiring 1200–1500 mm of water per growing season—two to three times more water per unit yield than wheat or maize [2]. Despite covering only about 14% of China’s arable land, the black soils (Chernozems) of the Northeast plain contribute nearly one-fifth of the nation’s rice production [3], in addition to 32.8% of maize and 45.8% of soybean output [4]. Owing to their high organic matter content, favorable structure, and strong water-holding capacity, these soils form a major grain production base and a strategic reserve for national food security [5,6,7]. However, their extremely slow formation renders them effectively non-renewable [8,9].

Decades of intensive cultivation, excessive fertilizer inputs, nutrient depletion, and insufficient organic amendments have led to soil acidification, structural degradation, and broader environmental problems that disrupt agroecosystem functioning [10,11]. Soil organic matter in the region has declined by 20–40% over the past three decades, and together with erosion and climate-induced hydrological changes, this deterioration threatens the long-term sustainability of rice production [12]. Empirical evidence indicates that each 0.5% decrease in black soil organic matter can cause more than a 15% yield loss, highlighting the pivotal role of soil fertility in maintaining productivity [13,14]. At the same time, climate change is intensifying hydrological variability, while the continued expansion of irrigated agriculture is exacerbating pressure on limited water resources [15,16], making water scarcity an increasingly binding constraint for rice cultivation in Northeast China. Protecting the black soils of the Northeast plain through effective soil and water conservation practices is therefore crucial for sustaining regional ecosystem health and national food security under mounting climate and water stress [17].

Plastic mulching has become an important practice for improving crop production in water-limited environments [18]. In China, it is used on around 13% of farmland and accounts for nearly 60% of global agricultural plastic film consumption [19]. Mulching conserves soil moisture, moderates soil temperature, suppresses weeds, and reduces competition for water and nutrients, thereby enhancing crop yields and water use efficiency [20,21]. In Northeast China, plastic films are widely applied in rice paddies to alleviate low early-season temperatures, improve seedling establishment, and reduce evaporative losses [22]. However, conventional polyethylene (PE) films degrade very slowly, leaving persistent residues (“white pollution”) that impair soil structure, reduce porosity, increase bulk density, alter microbial communities, and ultimately undermine soil fertility and crop productivity [23,24]. To mitigate these environmental risks, BF has emerged as a promising alternative, capable of decomposing into CO2, water, and biomass under field conditions [25]. Recent studies have demonstrated that BFs have the potential to improve soil properties and crop yields [26,27]. Nevertheless, most research has focused on dryland crops such as maize, potato, and wheat in arid or semi-arid regions [28] and systematic evaluations of BFs in cold-region paddy rice systems—particularly those in black soils—remain scarce. Moreover, few studies have combined multiple indicators, including water consumption, crop physiological traits, soil physico-chemical characteristics, and yield and quality, in a single study.

Despite their potential environmental advantages, BF performance in black soil paddy fields is strongly shaped by material properties, degradation dynamics, and local climate. A key knowledge gap concerns how BFs with different degradation induction periods affect the coupled processes of water use, soil hydrothermal conditions, crop physiology, and yield in Northeast China’s rice systems. We hypothesize that biodegradable films with longer induction periods more effectively improve soil thermal–moisture conditions, enhance rice productivity, and promote soil C and N cycling compared to short-period BFs and CK. Accordingly, the objectives of this study were to (1) quantify the effects of different BFs on soil hydrothermal conditions; (2) evaluate how these treatments influence rice growth, yield, quality, and irrigation water use efficiency; and (3) determine the changes in soil organic matter content under various treatments. By integrating agronomic, environmental, and soil quality metrics, this study evaluates the suitability of BFs for paddy rice cultivation in the black soils of Northeast China and provides technical guidance for replacing conventional plastic films in cold-region rice systems in line with national plastic pollution control policies and long-term food security goals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

The experiment was conducted at the Heilongjiang Water Conservancy Science and Technology Experiment Research Center (45°43′ N, 126°36′ E), located in Xin Nong Town, Daoli District, Harbin City, from May to September in 2023 and 2024. The region is characterized by a temperate monsoon climate, with an average annual temperature ranging from −4 °C to 5 °C. The frost-free period spans 130 to 140 days, and the annual average precipitation is between 400 and 650 mm, with 80% of the rainfall occurring from May to September.

The soil at the experimental site is classified as Haplic Phaeozem (Loamic) in accordance with the IUSS Working Group (2014, 2022), with a depth of 0–100 cm. The soil’s water-holding capacity is 0.36 cm3/cm3 (by volume), with a bulk density of 1.32 g/cm3 and a pH of 7.2. The organic carbon content in the 0–20 cm soil layer is 14.5 g/kg. Furthermore, the available nitrogen (N), available phosphorus (P2O5), and available potassium (K2O) concentrations in the 0–80 cm soil layer are 117.6 mg/kg, 24.1 mg/kg, and 284.7 mg/kg, respectively. Figure S1 presents the precipitation and daily mean temperature.

2.2. Experimental Design

The rice variety Daohua Xiang No. 2 was used in the experiment. Planting was carried out on 20 May 2023 and 23 May 2024, with harvesting conducted on 22 September 2023 and 24 September 2024. The effects of black biodegradable film with varying induction periods—45 days (BF45), 60 days (BF60), and 80 days (BF80)—were investigated. In addition, a conventional black plastic film treatment (BN) and an untreated control group (CK) were included, resulting in five treatments, each with three replicates. The experimental design followed a completely randomized design (CRD). The biodegradable film used had a thickness of 0.01 mm and a width of 1.9 m. The procedures for film coverage and rice transplanting are depicted in Figure S2.

Before the rice was planted, the field was soaked for 3 days. Each plot had an area of 27.5 m2 (5 m × 5.5 m), consisting of a 5 m-long bed with a width of 1.5 m, separated by a 20 cm wide, 15 cm deep irrigation ditch between each bed. A 30 cm wide, 15 cm deep irrigation ditch was also constructed around the plot perimeter. Embankments, 0.5 m wide and 0.6 m high, with water barriers, were built between plots.

Rice was planted in the north–south direction, with a plant spacing of 12 cm and row spacing of 30 cm, at a density of 277,777 holes per hectare (4 plants per hole). Protective rows were placed around the plot perimeter. Furrow irrigation was used, with water applied to a depth of 3 cm above the bed surface. During the greening stage, a 3 cm water layer was maintained; irrigation during other growth stages was based on tensiometer readings. Irrigation was initiated when the tensiometer (Beijing Shunlong Technology Development Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) reading reached −15 kPa, except during the booting and flowering stages, when the threshold was −10 kPa. After pesticide application (acephate, total active ingredient content 30%; 450–675 g ha−1), a 4 cm water layer was maintained for 3 days. Fertilizers applied included urea (N 46%) at 190 kg/hm2, slow-release fertilizer (N 44%, with a 60-day release period) at 200 kg/hm2, and a mixture of humic acid fertilizer, enzyme bacteria, and Xin Balok fertilizer at 750 kg/hm2, all applied as a one-time base application (enzyme-activated organic compound fertilizer (N + P2O5 + K2O ≥ 30%; organic matter ≥ 10%) (Heilongjiang Dafeng Technology Development Co., Ltd., Harbin, China); humic acid bio-organic fertilizer (fulvic acid ≥ 12%; organic matter ≥ 40%; Bacillus megaterium + Paenibacillus mucilaginosus ≥ 0.5 × 100 M/g) (Shandong Quanlin Jiayou Modern Agriculture Co., Ltd., Shandong, China); X-Balok (organic matter content ≥ 30%; nitrogen, phosphorus and calcium content ≥ 5%) (Su Yuan Yuan Bioengineering Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China), (enzymes 375 kg/hm2 + organic fertilizer 300 kg/hm2 + Xin Balok 150 kg/hm2). The rice growth stages are detailed in Table S1.

2.3. Measurement

2.3.1. Meteorological and Soil Temperature Monitoring

Meteorological factors, including temperature and rainfall, were monitored using the automatic weather station at the Heilongjiang Water Conservancy Science and Technology Experiment Research Center. The period from May to September covers the entire rice growth cycle. Total rainfall during this period was 535 mm in 2023 and 414 mm in 2024. Soil temperature was monitored at a depth of 5 cm, in the center of each plot’s bed, avoiding the main root zone of the rice. A button-type soil temperature logger (HOBO MX2201; Onset, Bourne, MA, USA) was installed. The logger’s accuracy is ±0.5 °C, and soil temperature data were recorded hourly. Soil effectively accumulated temperature [29].

where Tn represents the effective accumulated temperature of the soil (°C), n is the total number of days, and Xi is the daily average soil temperature (°C).

2.3.2. Soil Moisture Content Measurement

Soil samples were collected during the rice tillering, jointing and booting, heading and flowering, and maturity stages. A soil auger was used to collect samples vertically between two rows at depths of 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, 20–30 cm, 30–50 cm, 50–70 cm, and 70–90 cm. Soil moisture content was determined by gravimetric measurements.

2.3.3. Rice Growth Parameters, Yield, and Quality

After the rice regreening stage, plant height was measured every 7 days by selecting 10 fixed hills per plot using a steel tape measure. During the tillering stage, the number of tillers was recorded every 7 days from 10 fixed hills. At maturity (just before rice harvest), 30 hills were randomly selected from each replicate to determine the effective tiller count.

At the tillering, jointing and booting, heading and flowering, and maturity stages, the average number of stems and tillers per plot was used to measure the leaf area from 5 selected hills. Leaf area was determined using the length-width coefficient method. The leaf area index (LAI) was calculated as follows [30]:

During the rice tillering, jointing and booting, heading and flowering, and maturity stages, five random hills were selected from each plot. The rice samples were dried using the oven-drying method. The samples were placed in an oven, heated at 105 °C for 0.5 h, after which the temperature was reduced to 80 °C and the samples were dried for 48 h until a constant weight was achieved. The aboveground and belowground dry matter masses were measured using an electronic balance.

At maturity (just before harvest), 30 random hills were selected from each plot to measure the number of effective panicles. From the average number of effective panicles per 30 hills, 5 hills were chosen to measure the number of grains per panicle and the seed-setting rate. After drying the rice (to a moisture content of 11–12%), the yield was determined. A random sample of 1000 grains were selected to measure the 1000-grain weight.

Quality indicators, including milling percentage, brown rice percentage, and chalky rice percentage, were measured according to the national standard GB/T17891-2017 “High-quality Rice” [31]. The amylose and protein content in polished rice was determined using a near-infrared grain analyzer (Inframatic 9500 Plus, Perten Instruments, Hägersten, Sweden). After cooking the polished rice, the rice cooking quality was evaluated using a rice taste meter (STA1A, Satake Corporation, Higashi-Hiroshima, Hiroshima, Japan).

2.3.4. Irrigation Water Use Efficiency [32]

2.3.5. Soil Carbon (C) and Nitrogen (N) Content Measurement

Soil samples were collected from the 0–5 cm and 5–20 cm soil depths in each plot. Three random sampling points were selected from each bed, and the samples from each layer were combined to form two composite samples corresponding to the 0–5 cm and 5–20 cm layers. The samples were air-dried by spreading them on kraft paper bags in a room and then ground using a ball mill. A suitable amount of the ground soil was weighed and analyzed for total carbon (C) and total nitrogen (N) content using a Vario EL Cube elemental analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). Approximately 5 g of air-dried soil, passed through a 2 mm sieve, was placed in a 50 mL beaker. Thirty milliliters of 0.2 mol/L hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution were added, and the mixture was thoroughly stirred before standing for 24 h. The sample was then rinsed with deionized water to remove the hydrochloric acid. After drying at 60 °C, the soil samples were ground again using a ball mill. A suitable amount was weighed, and the organic carbon (C) and organic nitrogen (N) content in the soil were determined using the Vario EL Cube elemental analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany).

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were processed using Microsoft Excel 2019, and graphs were generated with Origin 2021. Variance analysis was conducted using SPSS 24 software.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Changes in Soil Temperature and Moisture Content Under Plastic Mulch Coverage

3.1.1. Soil Temperature and Effective Accumulated Temperature Status

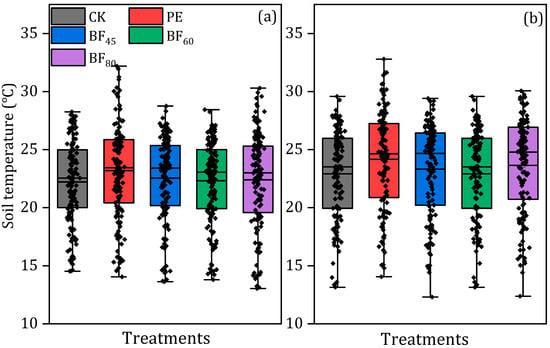

Statistical analysis revealed that the soil water and thermal environment were significantly enhanced by plastic mulch. Among biodegradable films, BF80 consistently showed the greatest warming effect, while conventional plastic film (PE) achieved the highest overall soil temperatures (Figure 1). In 2023, the daily mean soil temperature increases under BF45, BF60, and BF80 were 2.1, 1.7, and 2.9 °C, respectively, and 2.1, 2.4, and 2.7 °C in 2024. For daily maximum temperatures, increases were 2.2, 2.5, and 3.5 °C in 2023, and 3.4, 2.8, and 3.4 °C in 2024 for BF45, BF60, and BF80. PE consistently produced the most significant warming, with daily mean temperatures exceeding CK by 3.9 °C in 2023 and 3.4 °C in 2024 (Figure S1). Effective accumulated temperature at 5 cm soil depth during the greening and tillering stages is shown in Table 1. In both years, all BF treatments increased effective accumulated temperature relative to CK, with a more pronounced response during the cooler tillering stage in 2024. In 2023, BF45, BF60, and BF80 increased all-day effective accumulated temperature by 104.1, 77.5, and 103.9 °C, respectively, during greening, and by 102.5, 90.5, and 172.6 °C during tillering. In 2024, the corresponding increases were 75.9, 66.7, and 98.2 °C during greening and 135.3, 173.2, and 152.0 °C during tillering. These patterns indicate that the effects of BFs on soil heat accumulation varied with growth stage and year. During the tillering stage, PE consistently produced higher accumulated temperatures than the biodegradable films, reaching 754.0 °C in 2023 and 736.1 °C in 2024.

Figure 1.

Soil temperature at a 5 cm depth from rice transplanting to the end of the tillering stage under different treatments in 2023 (a) and 2024 (b). Different letters within the same growth stage indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Soil effective accumulated temperature in 2023 and 2024.

3.1.2. Soil Moisture Content

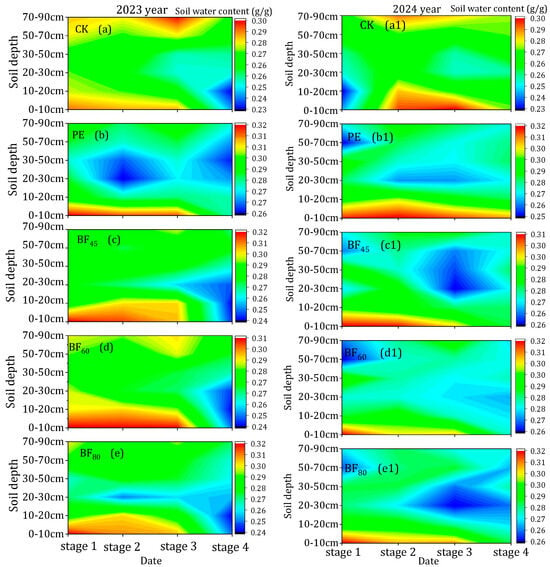

As shown in Figure 2a–e1, plastic mulching markedly altered the distribution of soil moisture across different soil layers (0–90 cm) at different stages in 2023 and 2024. The most significant differences were observed during the tillering stage. In 2023, PE showed a 3.8% increase, while BF80 had a 4.1% increase. In 2024, PE increased surface soil moisture by 11.8% relative to CK, compared with 9.9% in 2023. In later stages, the differences between treatments and CK were smaller. For instance, in the ripening stage of 2024, PE increased surface moisture by 4.5% relative to CK. The greatest differences were observed in the early stages, with PE showing 5.6% higher moisture than CK during the jointing–booting stage in 2024 and 5.2% higher in 2023. By the ripening stage, the differences narrowed to 3.5–4.0% in 2023 and 3.9–4.5% in 2024.

Figure 2.

(a–e1) Soil moisture content at different growth stages of rice over two years. Note: stage 1—tillering stage; stage 2—jointing–booting stage; stage 3—heading–flowering stage; stage 4—ripening stage.

3.2. Changes in Rice Growth, Yield, Rice Quality, and Irrigation Water Use Efficiency Under Mulching Conditions

3.2.1. Plant Height and Leaf Area

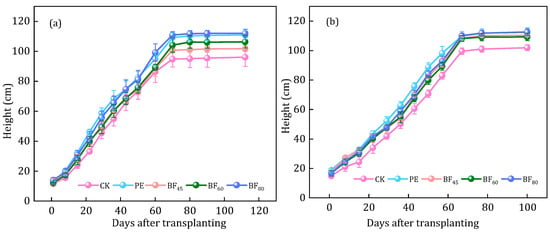

Plant height responses to mulching treatments over two years are presented in Figure 3. In both years, plants grown under BFs were taller than CK. In 2023, final plant height reached 101.6 cm (BF45), 105.6 cm (BF60), and 112.0 cm (BF80), while PE attained 110.0 cm, comparable to BF80. In 2024, differences among mulched treatments narrowed, with BF80, BF45, and BF60 reaching 111.6, 110.3, and 109.3 cm, respectively. These results indicate that longer induction periods promoted greater plant height, particularly in 2023, although the advantage diminished slightly in 2024. Overall, BF80 consistently produced the tallest plants, while PE displayed similar performance by the second year.

Figure 3.

Plant height from transplanting to maturity under different treatments in 2023 year (a) and 2024 year (b).

Mulching also had a marked effect on canopy development, as reflected in the leaf area index (LAI) shown in Table 2. Across both years, mulching significantly increased LAI at tillering, jointing–booting, and heading–flowering compared with CK. Among biodegradable films, BF80 generally maintained the highest LAI across stages, with only minor differences from BF45 in 2024. During the heading–flowering stage, LAI under biodegradable films was 27–106% higher than CK. In 2023, LAI values reached 5.06 (BF45), 5.55 (BF60), and 5.94 (BF80), compared with 6.71 under PE; in 2024, the corresponding values were 5.11, 4.96, and 5.18 for BFs, while PE remained highest at 5.90.

Table 2.

Leaf Area Index (LAI) under different treatments over two years.

3.2.2. Tillering and Dry Matter Accumulation

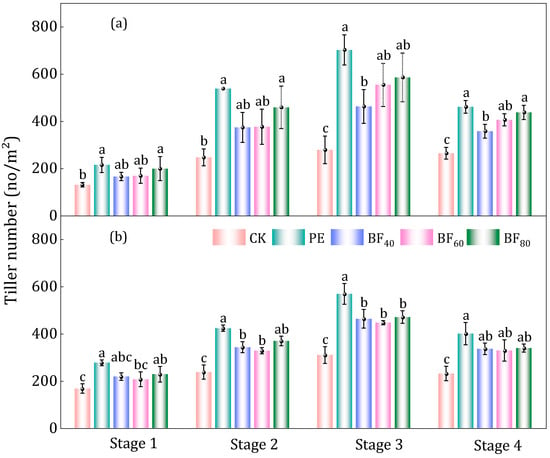

Mulching treatments significantly increased both the total tiller number during the tillering stage and the number of effective tillers at maturity compared with CK (Figure 4). PE produced the highest tiller numbers and effective tillers. In 2023, BF45, BF60, and BF80 increased tiller numbers by 66%, 99%, and 110% relative to CK (279 tillers/m2) and effective tillers by 35%, 54%, and 65% over CK (265 tillers/m2), with the magnitude of increase rising progressively with longer induction periods. In 2024, the corresponding increases were 50%, 44%, and 52% for tiller number and 45%, 42%, and 47% for effective tillers relative to CK (309 and 231 tillers/m2, respectively); although the differences among BFs were smaller, BF80 still produced the greatest enhancement. Across both years, the PE treatment showed the strongest promotion of tillering, with tiller numbers 152% and 84% higher and effective tillers 74% and 73% higher than CK, outperforming all BFs.

Figure 4.

Rice tiller number in 2023 year (a) and 2024 year (b). Note: Stage 1: Early tillering stage, Stage 2: Mid-tillering stage, Stage 3: Late tillering Stage, Stage 4: Effective tillers at maturity. Note: Letters denote statistical differences among groups. Means sharing the same letter are not significantly different, whereas means with different letters differ significantly.

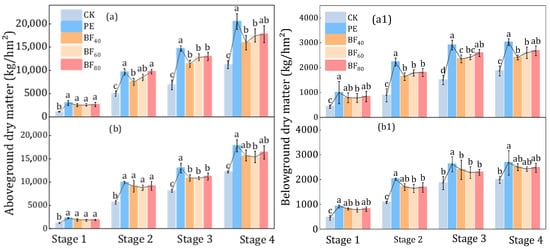

Above- and belowground dry matter accumulation is shown in Figure 5a,b,a1,b1. Across both years, mulching significantly increased dry matter compared with CK, with PE consistently producing the highest values. In 2023, BF45, BF60, and BF80 increased aboveground dry matter by 51%, 72%, and 96% at jointing–booting; by 60%, 86%, and 88% at heading–flowering; and by 43%, 56%, and 58% at maturity, respectively, relative to CK. Meanwhile, belowground dry matter increased by 56.7%, 61.1%, and 72.5% at heading–flowering and by 29.1%, 39.2%, and 43.4% at maturity, showing an increasing trend with longer induction periods. In 2024, BF80 achieved the highest aboveground dry matter at maturity, 34% greater than CK, whereas belowground dry matter under BF80 was slightly lower than under BF45. At maturity, aboveground dry matter under PE was 83% and 46% higher than CK in 2023 and 2024, respectively, and its belowground biomass was 7.0–25.5% greater than that of the BFs, confirming the stronger overall biomass accumulation under PE.

Figure 5.

Aboveground and belowground dry matter accumulation of rice in 2023 year (a) and 2024 year (b). Note: (a) 2023 year and (b) 2024 year, Stage 1: Tillering stage, Stage 2: Jointing–booting stage, Stage 3: Heading–flowering stage, Stage 4: Ripening stage. Letters denote statistical differences among groups. Means sharing the same letter are not significantly different, whereas means with different letters differ significantly.

3.2.3. Yield, Irrigation Water Use Efficiency (IWUE) and Rice Quality

As shown in Table 3 and Table 4, mulching treatments significantly affected rice yield and irrigation water use efficiency (IWUE) in both 2023 and 2024. Mulching increased yield mainly by increasing the number of productive panicles and grains per panicle, with little change in grain filling percentage and 1000-grain weight. The number of grains per panicle was consistently higher under BFs than under CK, whereas grain filling percentage showed a slight reduction (1.6–2.1% lower than CK in 2023 and 1.2–1.6% lower in 2024), although these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). In 2023, yields under BF45, BF60 and BF80 were 54%, 61% and 73% higher than CK, with BF80 achieving the maximum increase. In 2024, yield gains of BFs declined to 25–28% above CK, but BF80 still maintained the lead among BFs. PE achieved the highest yield overall, with increases of 77% and 31% over CK in 2023 and 2024, respectively. Compared with BF80, PE increased grain yield by only 2.3% and 2.1% in 2023 and 2024, respectively, but increased IWUE by 11.0% and 11.7%. Overall, IWUE increased by 48–101% under BFs and by 75–123% under PE relative to CK.

Table 3.

Yield and yield components under different treatments.

Table 4.

Irrigation water use efficiency under different treatments.

With respect to quality (Table 5), milling performance was similar among treatments. The milled rice rate differed by no more than 0.5%, and the head rice rate under BFs was only 1.0–1.8% higher than CK and close to PE. In contrast, appearance quality improved under mulching. In 2023, BFs reduced chalky grain percentage by 8–51% and chalkiness degree by 19–32% relative to CK. In 2024, the reductions were 9–28% and 3–26%, with BF60 giving the lowest values in both years. PE showed milling and appearance quality comparable to BFs. Nutritional and eating quality changed little, protein and amylose contents were almost unchanged, and starch content under BFs increased only slightly (up to 1.5% higher than CK in 2024). Sensory scores were higher under BFs than CK by about 0.3–2.9% in 2023 and 1.5–2.6% in 2024, with BF60 and BF45 giving the highest scores in each year, but differences among BFs treatments were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Table 5.

Quality of grinding and appearance, nutritional and taste quality under different treatment conditions.

3.3. Soil Carbon (C) and Nitrogen (N) Content

Soil C and N contents at 0–5 and 0–20 cm depths are shown in Table 6 and Table 7. In the surface 0–5 cm layer, mulching treatments had little effect on soil organic carbon (SOC), total carbon (TC), or nitrogen fractions, and no significant differences were detected among CK, PE, and the BF treatments. In contrast, at 0–20 cm depth, both PE and BFs slightly increased SOC relative to CK in both years, with SOC under BF treatments being about 3–7% higher than CK and generally comparable to or slightly higher than that under PE, particularly for BF80. Organic N (Org-N) was also marginally higher under BFs than under CK and PE in 2024 (≈4% increase), whereas total N (TN) under BF treatments tended to be slightly lower than CK (about 3–7% reduction), indicating that BFs promoted carbon accumulation more than nitrogen retention. For TC, values under BFs were similar to CK and consistently higher than under PE in 2023, while in 2024 TC decreased across all treatments but remained lowest under PE and slightly higher under BFs. The C:N ratio was close to 12.0 for all treatments in 2023, but in 2024 it increased under BFs by roughly 3–5% compared with CK and PE.

Table 6.

Soil C and N content at 0–5 cm depth under different treatments over two years.

Table 7.

Soil C and N content at 0–20 cm depth under different treatments over two years.

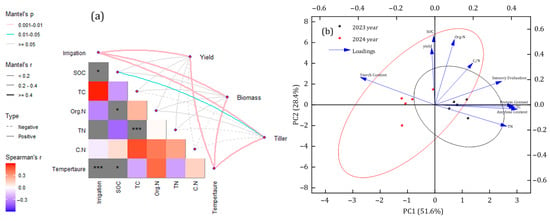

To explore differences among samples from different years and reveal relationships between key variables, we conducted correlation analysis and a principal component analysis (PCA). Temperature and irrigation volume are positively correlated with yield (Figure 6a). Figure 6b displays the PCA results, where PC1 and PC2 explain 51.6% and 28.4% of the total variance in the data, respectively. Soil organic carbon (SOC) and total carbon (TC) showed positive correlations with rice growth and quality traits, indicating that abundant soil organic matter plays a beneficial role in rice development. Meanwhile, organic nitrogen (Org-N) exhibited a negative correlation with rice growth. It should be emphasized that this does not imply that high nitrogen levels per se inhibit rice development but rather that excessive Org-N supply, which can disrupt the optimal soil C:N balance, may induce physiological trade-offs in rice plants (e.g., altered nutrient allocation or reduced resource use efficiency) and thus potentially exert an inhibitory effect on growth. The C/N ratio and total nitrogen (TN) content are also closely related to rice yield and quality, which requires further in-depth study to systematically elucidate the complex relationships between soil properties, yield, and quality throughout the entire rice growth process.

Figure 6.

(a,b) Correlation analysis among soil properties, Yield, Biomass and Tiller; Principal component analysis (PCA) based on Yield, Soil organic carbon (SOC), Total carbon (TC), Organic nitrogen (Org-N), Total nitrogen (TN), Carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C/N), Protein Content, Starch content, Amylose content, and Sensory evaluation under different mulching conditions. Note: * and *** indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Film Mulching on Soil Temperature and Soil Moisture Content

Plastic mulching reduces soil evaporation and improves the water use efficiency with limited water resources in arid and semi-arid regions while simultaneously increasing soil temperature and improving the thermal environment for crop growth [33]. Our results indicated that the warming effect of mulch film primarily occurs during the early growth stages of rice (Table 1). However, PE exhibited the most pronounced warming effect, while the warming effect of BFs increased with longer induction periods (Figure 1). Similar conclusions were drawn by [34], who reported that plastic mulching increased soil temperature during all growth stages except at the ripening stage, with significant differences from the control, especially in the 0–0.25 m soil layer. Additionally, significant warming effects from plastic mulching were observed during the seedling and jointing stages of wheat, particularly in the 10 cm and 20 cm soil layers [35].

During the tillering stage, the effective accumulated soil temperature at 5 cm under film treatments showed significant differences compared to CK (Table 1). This is likely because the film suppresses soil evaporation, reducing latent heat loss and altering soil–atmosphere energy partitioning, which contributes to higher surface soil temperature. Additionally, plastic mulching reduces soil evaporation, reallocating more surface energy to sensible heat flux, which contributes to the increase in surface temperature during the early growth stages of crops [36]. However, in the later stages of rice growth, plant canopy coverage and the degradation of BFs gradually diminish their warming and moisture retention performance [37], which explains the smaller differences in soil temperature observed toward ripening.

In the surface soil layer (0–20 cm), mulching markedly enhanced soil moisture compared with CK, with significant differences among cover types (Figure 2a–e1). The film forms a semi-enclosed system with the soil surface, limiting direct evaporation, while condensed water on the underside of the film re-infiltrates into the topsoil. PE consistently maintained the highest moisture content throughout the growing season, whereas BFs retained slightly less moisture, and CK had the lowest values. Among the biodegradable treatments, BF80 generally exhibited the best moisture-retention performance, reflecting its longer induction period and slower loss of film integrity. In deeper soil layers (>30 cm), no consistent pattern in moisture among treatments was observed across the two years, suggesting that mulching mainly modifies the hydrothermal regime of the plow layer rather than the subsoil. Previous studies have also shown that mulching improves soil moisture by reducing evapotranspiration; however, during the later growth stages, the degradation of BFs enhances soil evaporation, leading to increased moisture loss [38,39]. Conversely, studies indicated that PE and BFs reduce moisture content in deeper soil layers; the primary reason is that they promote increased absorption of soil moisture by the root system [40]. Moreover, the effectiveness of mulching is also influenced by the type of field, with paddy fields (flooded fields) generally retaining more moisture due to continuous water supply, while dryland fields experience more rapid moisture loss due to lack of irrigation, thus altering the benefits of mulching in different field types. Therefore, a more detailed analysis of the effects of mulching on soil moisture and temperature is necessary to fully understand its potential and limitations across different cropping systems and environmental conditions.

4.2. Effect of Mulching on Rice Growth, Yield, IWUE, and Rice Quality

Film mulching improves the soil hydrothermal environment, thereby promoting crop growth and yield. In this study, all mulched treatments increased plant height and canopy development relative to CK, and the effect was most evident in the early growth stages (Figure 3, Table 2). Among the BFs, BF80 generally produced the greatest increases in plant height and LAI, whereas PE consistently showed the largest overall enhancement across both years. This indicates that BFs, particularly those with longer induction periods, can approach but do not fully match the growth-promoting effect of PE in the cool conditions of Northeast China. Similarly, Reference [40] found that mulching provides the foundation for main seedling establishment and canopy development. In addition, mulching significantly increased dry matter (Figure 2), with PE consistently outperforming BFs. In 2023, BF60 had the greatest increase, while in 2024, BF80 was the most effective, showing 34% higher dry matter than CK. PE achieved the highest dry matter, 83% and 46% greater than CK in 2023 and 2024, respectively. Reference [41] indicated that compared to uncovered plots, plastic film coverage significantly increased root biomass and root dry weight by 35.06% and 37.32%, respectively. This is attributed to the mulching creating favorable soil conditions that promote root proliferation, thereby increasing rice yields [42]. In conclusion, PE or BFs, especially those with longer induction periods, can significantly enhance early-stage plant growth and canopy expansion. However, their advantages diminish over time, and PE continues to be the most reliable option for optimizing plant growth in the long term.

The average rice yield over the two study years ranked as PE > BF80 > BF60 > BF45 > CK, indicating that BFs significantly improved yield compared with the control but remained inferior to PE (Table 4). It is noteworthy that temperature had a greater positive effect on production-related indicators, such as tiller number, biomass, and yield, than other soil nutrients (S0C, TC, Org.N, TN, C.N) (Figure 6a); the correlation coefficients were all 0.751 (p < 0.05). Thiss is because in Northeast China, where early-season temperatures are relatively low, mulching improves the thermal and hydrological conditions of the soil, thereby facilitating rice emergence and promoting subsequent crop growth and yield [43,44].

Across both years, mulching significantly increased rice yield over CK, mainly through greater productive panicle number. In 2023, PE, BF80, and BF60 raised panicle number by 55–74%, while in 2024, the increase was 40–73%. Reference [45] also found that compared to PE film, the two BFs increased yields by 8.87% and 6.74%, respectively. Reference [40] indicated that plastic mulching increased average maine yield by 26.74% compared to the CK. This may be due to the provision of favorable water and thermal conditions. In contrast, grains per panicle, grain filling, and 1000-grain weight varied little among treatments. The superior performance of PE and BF80 was linked to their ability to maintain favorable soil temperature and moisture during early growth, supporting tiller initiation and survival. BF45 degraded earlier, reducing panicle formation. These results confirm that yield gains from mulching in Northeast China rice systems are primarily attributable to enhanced tillering and panicle density rather than changes in grain size or filling. Therefore, studies validated that plastic mulching technology enhances crop yields and improves crop quality. Across two seasons, BF increased IWUE 48–101% versus CK, with longer induction periods generally performing better; PE remained highest (Table 4). Film mulching increases crop WUE by approximately 45–106% across different mulching methods and field conditions in China, while acknowledging potential environmental trade-offs (e.g., residual plastic pollution) [46]. Our ranking of PE ≥ BF > CK mirrors dry-seeded rice trials where both PE and biodegradable films improved water productivity relative to no mulching, although PE typically led to IWUE [47].

Previous research has shown that the application of PBAT/PLA lignin-based biodegradable film in melon cultivation can significantly enhance both yield and fruit quality [48]. This study showed that BFs had minimal effects on milling and nutritional quality but significantly improved appearance and eating quality (Table 5). Milling performance was stable across treatments, while chalky grain percentage and chalkiness degree were markedly reduced under BFs, with BF60 (2023) and BF45 (2024) showing the lowest values. These results are consistent with reports that hydrothermal conditions during grain filling strongly influence chalk formation [49,50,51]. By moderating soil temperature and moisture, BFs likely enhanced assimilate translocation and starch deposition, thereby reducing chalkiness. Importantly, BFs performed comparably to PE, confirming no disadvantage in processing or appearance quality. Nutritional traits such as protein and amylose contents remained stable, while starch content increased slightly but non-significantly under BFs. Sensory evaluation indicated consistent improvements over CK, with the best performance observed in BF60 (2023) and BF45 (2024). These enhancements may reflect more favorable starch structural properties and pasting behavior under improved hydrothermal conditions [52,53,54].

Overall, BFs maintained milling and nutritional stability while improving appearance and eating quality to levels comparable with PE mulching. This supports their role as a sustainable alternative for rice cultivation. Future studies should focus on the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying these effects, particularly the regulation of starch biosynthesis and chalkiness-related genes under variable field environments [55,56]

4.3. Effect of Mulching on Soil Carbon (C) and Nitrogen (N) Content

Mulching had little effect on soil C and N in the very surface layer; at 0–5 cm, SOC, TC, and N fractions did not differ significantly among CK, PE, and BF treatments. By contrast, clear effects emerged in the 0–20 cm plow layer (Table 7), where SOC was consistently higher under BFs than under CK (BF80 > BF60 > BF45), and generally not lower than under PE. In 2024, Org-N was slightly higher and TN slightly lower under BFs than under CK and PE, resulting in a modestly higher C:N ratio, especially under BF80, indicating relatively greater C accumulation under biodegradable mulching. Overall, longer-induction BFs not only sustain crop production but also promote SOC build-up in the plow layer compared with no mulching and, in some cases, with PE. This is consistent with studies reporting that biodegradable or degradable films foster SOC accrual via enhanced microbial C use efficiency and aggregate protection, and can even reduce SOC decomposition compared with PE under warming scenarios [57]. In parallel, film mulching is known to reshape microbial activity and C/N cycling—mechanisms that plausibly underlie our SOC gains under BF. References [58,59] observed similar increases in soil organic carbon storage under film-covered rice cultivation, largely due to the increased surface soil temperature, which accelerates the mineralization of soil organic matter and promotes rice growth and aboveground biomass. This, in turn, results in greater photosynthate transfer to the roots, leading to substantial increases in organic carbon deposition in film-covered systems [60]. Additionally, BF significantly increased SOC storage and reduced carbon loss in arid agroecosystems. This was due to improved soil temperature and moisture conditions, which enhanced microbial activity and more efficiently converted organic carbon, promoting microbial carbon accumulation [61,62].

Overall, our results demonstrated that the established water-saving advantage of film mulching, while showing that BFs deliver substantial IWUE improvements over CK and tangible SOC benefits, narrowing (though not eliminating) the performance gap to PE. In contexts where plastic pollution and end-of-life costs weigh heavily, BF with longer induction periods offers a pragmatic balance between water efficiency and soil carbon stewardship [56]. In summary, plastic mulching enhances rice yield and improves soil conditions; this phenomenon is also found in maize and peanut [63,64]. Rice production, nutritional quality, and soil environment are significantly correlated. In this study, correlation analysis indicates that SOC had a positive impact on yield, with a correlation coefficient of 0.391 (Figure 6a). PCA analysis also indicated that SOC positively influences yield (Figure 6b). SOC plays an essential role in maintaining soil fertility and boosting crop productivity [65]. Yield is negatively correlated with protein content and amylose content, possibly because increases in grain yield are generally attributed to a dilution effect that reduces protein content [66,67].

5. Conclusions

This study compared conventional polyethylene (PE) film with biodegradable films (BFs) of different induction periods in a cold-region paddy rice system on black soils. Both PE and BFs improved soil hydrothermal conditions, enhanced rice growth, and significantly increased yield and IWUE relative to the no-mulch control, with PE giving the highest values and BF80 achieving yields only slightly lower than PE. BFs had little effect on milling and nutritional quality but improved appearance and eating quality. BF treatments—especially BF80—raised SOC and C:N in the 0–20 cm layer, indicating greater soil carbon accumulation. Overall, BFs with longer induction periods provide a practical compromise between agronomic performance and environmental impact, offering substantial gains in yield, IWUE, and soil carbon while reducing long-term plastic pollution.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants15030358/s1.

Author Contributions

Y.Z.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Software, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. X.L.: Writing—review and editing, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. K.Z.: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. S.F.: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. C.D.: Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. X.C.: Software, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. Y.H.: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. B.W.: Software, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. Y.S.: Software, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. F.W.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Software, Resources, Formal analysis. X.G.: Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. H.W.: Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported financially by the National Key Research & Development Program of China (2022YFD1500402), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51809225), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020T130559, 2019M651977), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (BK20180929).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available at this stage because the dataset is still being curated and is being used in ongoing manuscript preparation and submission.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the individuals and funding projects that have contributed to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rosegrant, M.W.; Cline, S.A. Global Food Security: Challenges and Policies. Science 2003, 5652, 1917–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, B.A.M.; Humphreys, E.; Tuong, T.P.; Barker, R. Rice and Water. Adv. Agron. 2007, 92, 187–237. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Li, N.; Yang, X.; Sun, Z. For the protection of black soils. Nat. Food 2025, 6, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, L.; Jamshidi, A.H.; Niu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X. Assessment of the degree of degradation of sloping cropland in a typical black soil region. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 2220–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sui, Y.; Yu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Chu, H.; Jin, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, G. Soil carbon content drives the biogeographical distribution of fungal communities in the black soil zone of northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 83, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Deng, X.; Yue, H. Black soil conservation will boost China’s grain supply and reduce agricultural greenhouse gas emissions in the future. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hu, T.; Chen, J. Effects of artificial grassland establishment on soil nutrients and carbon properties in a black-soil-type degraded grassland. Plant Soil 2010, 333, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Lv, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiao, X.; Sui, Y. Pedogenesis of typical zonal soil drives belowground bacterial communities of arable land in the Northeast China Plain. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Guan, D.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, B.; Ma, M.; Qin, J.; Jiang, X.; Chen, S.; Cao, F.; Shen, D.; et al. Influence of 34-years of fertilization on bacterial communities in an intensively cultivated black soil in northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 90, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, J.N.; Townsend, A.R.; Erisman, J.W.; Bekunda, M.; Cai, Z.; Freney, J.R.; Martinelli, L.A.; Seitzinger, S.P.; Sutton, M.A. Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: Recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science 2008, 320, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvi, H.U.A.; Tahjib Ul Arif, M.; Azim, M.A.; Tumpa, T.A.; Tipu, M.M.H.; Najnine, F.; Dawood, M.F.A.; Skalicky, M.; Brestič, M. Rice and food security: Climate change implications and the future prospects for nutritional security. Food Energy Secur. 2023, 12, e430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.M.; Zhang, X.P.; Deng, W.; Fang, H.J. Black soil degradation by rainfall erosion in Jilin, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2003, 14, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadis, A.; Lafuente, F.; Turrión, M. Effect of land use, time since deforestation and management on organic C and N in soil textural fractions. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 183, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, T.; Liu, X.; Song, Y.; Tan, S.; Chen, Y.; Yan, P.; Wang, X. Effects of substituting synthetic nitrogen with organic amendments on crop yield, net greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprint: A global meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2023, 301, 109035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, C. How does straw-incorporation rate reduce runoff and erosion on sloping cropland of black soil region? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 357, 108676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.; Liu, J.; Scanlon, B.R.; Jiao, J.J.; Jasechko, S.; Lancia, M.; Biskaborn, B.K.; Wada, Y.; Li, H.; Zeng, Z.; et al. The changing nature of groundwater in the global water cycle. Science 2024, 383, eadf0630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tilman, D.; Jin, Z.; Smith, P.; Barrett, C.B.; Zhu, Y.; Burney, J.; D’odorico, P.; Fantke, P.; Fargione, J.; et al. Climate change exacerbates the environmental impacts of agriculture. Science 2024, 385, eadn3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, Z.; Wollmann, C.; Schaefer, M.; Buchmann, C.; David, J.; Troger, J.; Munoz, K.; Fror, O.; Schaumann, G.E. Plastic mulching in agriculture. Trading short-term agronomic benefits for long-term soil degradation? Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, H.; Wang, E.; He, W.; Hao, W.; Yan, C.; Li, Y.; Mei, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; et al. An overview of the use of plastic-film mulching in China to increase crop yield and water-use efficiency. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1523–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Wu, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, R.; Hao, R.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Qin, X.; Song, F.; et al. Effects of plastic film mulching on yield, water use efficiency, and nitrogen use efficiency of different crops in China: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2024, 312, 109407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Yao, Z.; Yan, C.; Liu, Q.; Ding, X.; He, W. Maize yield reduction is more strongly related to soil moisture fluctuation than soil temperature change under biodegradable film vs plastic film mulching in a semi-arid region of northern China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 287, 108351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.E.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, W. Plastic Film Mulching Improved Maize Yield, Water Use Efficiency, and N Use Efficiency under Dryland Farming System in Northeast China. Plants 2022, 11, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Yin, R.; Cai, W. Residual plastic film decreases crop yield and water use efficiency through direct negative effects on soil physicochemical properties and root growth. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, R.; Jones, D.L.; Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yan, C. Behavior of microplastics and plastic film residues in the soil environment: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 134722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campanale, C.; Galafassi, S.; Di Pippo, F.; Pojar, I.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F. A critical review of biodegradable plastic mulch films in agriculture: Definitions, scientific background and potential impacts. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 170, 117391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchaleaume, F.; Angellier-Coussy, H.; César, G.; Raffard, G.; Gontard, N.; Gastaldi, E. How Performance and Fate of Biodegradable Mulch Films are Impacted by Field Ageing. J. Polym. Environ. 2018, 26, 2588–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Flury, M.; Schaeffer, S.M.; Chang, Y.; Tao, Z.; Jia, Z.; Li, S.; Ding, F.; Wang, J. Agronomic performance of polyethylene and biodegradable plastic film mulches in a maize cropping system in a humid continental climate. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, X.; Wang, X.; Yuan, M.; Gao, M.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Zong, R.; Sun, C.; Zhang, M.; Li, Q. Effects of long-term biodegradable film mulching on yield and water productivity of maize in North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 304, 109094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Li, X.; Aimůnek, J.; Shi, H.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y. Evaluating the effects of biodegradable and plastic film mulching on soil temperature in a drip-irrigated field. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 213, 105116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Zhao, S.; Li, Y. Study on the Natural Ventilation Characteristics of a Solar Greenhouse in a High-Altitude Area. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 17891-2017; High Quality Paddy. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2017. Available online: https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=56C97D505F4880DE76E2D49C7DA0C872&refer=outter (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Li, J.; He, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lu, Y. Effects of Biodegradable Film Mulching and Water-Saving Irrigation on Soil Moisture and Temperature in Paddy Fields of the Black Soil Region. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Yan, C.; Liu, Q.; Ding, W.; Chen, B.; Li, Z. Effects of plastic mulching and plastic residue on agricultural production: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhao, L.; Feng, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, L. Effects of different colors of film mulch on soil temperature and rice growth in a non-flooded condition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 6352–6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Pan, X.; Gao, C.; Wang, Y.; He, F. Effects of tillage and mulching measures on soil moisture and temperature, photosynthetic characteristics and yield of winter wheat. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 201, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Qin, F.; Feng, J.; Huang, J. Regional climate effects of plastic film mulch over the cropland of arid and semi-arid regions in Northwest China using a regional climate model. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2020, 139, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Jia, Z. Hydrothermal effects on maize productivity with different planting patterns in a rainfed farmland area. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 205, 104794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Hu, C.; Oenema, O. Soil mulching significantly enhances yields and water and nitrogen use efficiencies of maize and wheat: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Fan, B.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Guo, L. Effects of mulching biodegradable films under drip irrigation on soil hydrothermal conditions and cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) yield. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wei, T.; Han, Q.; Ren, X.; Jia, Z. Effects of different film mulching methods on soil water productivity and maize yield in a semiarid area of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ren, L.; Zhang, N.; Liu, E.; Sun, S.; Ren, X.; Jia, Z.; Wei, T.; Zhang, P. Can soil organic carbon sequestration and the carbon management index be improved by changing the film mulching methods in the semiarid region? J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 1541–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Yan, C.; Whalen, J.K.; He, W.; Liu, H.; Cui, J.; Gong, D.; Mancl, K.; Liu, Q.; Mei, X. Biodegradable mulch films support root proliferation and yield in water-saving rice production. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Ding, R.; Kang, S. Plastic mulch decreases available energy and evapotranspiration and improves yield and water use efficiency in an irrigated maize cropland. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 179, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Fan, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Zheng, X.; Lin, H.; Guo, L. Testing biodegradable films as alternatives to plastic films in enhancing cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) yield under mulched drip irrigation. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 192, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Han, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhao, F.; He, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. PBAT/PLA humic acid biodegradable film applied on solar greenhouse tomato plants increased lycopene and decreased total acid contents. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 871, 162077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Mao, X.; Li, S.; Huang, X.; Che, J.; Ma, C. A Review of Plastic Film Mulching on Water, Heat, Nitrogen Balance, and Crop Growth in Farmland in China. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; He, W.; Chen, G.; Yan, C.; Gao, H.; Liu, Q. Dry Direct-Seeded Rice Yield and Water Use Efficiency as Affected by Biodegradable Film Mulching in the Northeastern Region of China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, X.; Olasupo, I.O.; Feng, Q.; Wang, L.; Lu, L.; Xu, J.; Sun, M.; Yu, X.; Han, D.; et al. Effects of biodegradable films on melon quality and substrate environment in solar greenhouse. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Long, C.; Deng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zeng, Y. Physiological Basis of High Nighttime Temperature-Induced Chalkiness Formation during Early Grain-Filling Stage in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Agronomy 2023, 13, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, T.; Miyazaki, M.; Shigemitsu, T.; Nakata, M.; Kuroda, M.; Kondo, M.; Masumura, T. Effect of high temperature stress during ripening on the accumulation of key storage compounds among Japanese highly palatable rice cultivars. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 95, 103018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yin, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, K.; Shen, Y.; Ding, Y.; Tang, S. Effects of High Temperature on Rice Grain Development and Quality Formation Based on Proteomics Comparative Analysis Under Field Warming. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 746180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Du, Y.; Zeng, M.; Deng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Zeng, Y. Relationship between Chalkiness and the Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Rice Starch at Different Nighttime Temperatures during the Early Grain-Filling Stage. Foods 2024, 13, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patindol, J.A.; Siebenmorgen, T.J.; Wang, Y.J. Impact of environmental factors on rice starch structure: A review. Starch—Stärke 2015, 67, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ge, J.; Xu, K.; Gao, H.; Liu, G.; Wei, H.; Zhang, H. Differences in starch structure, thermal properties, and texture characteristics of rice from main stem and tiller panicles. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 99, 105341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, X.; Zheng, M.; Hu, R.; Dong, J.; Zhou, L.; Liu, W.; Liu, D.; Yang, W. Genes controlling grain chalkiness in rice. Crop J. 2024, 12, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Liu, Q.; Gong, D.; Liu, H.; Luo, L.; Cui, J.; Qi, H.; Ma, F.; He, W.; Mancl, K.; et al. Biodegradable film mulching reduces the climate cost of saving water without yield penalty in dryland rice production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 197, 107071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Min, W.; Flury, M.; Gunina, A.; Lv, J.; Li, Q.; Jiang, R. Impact of long-term conventional and biodegradable film mulching on microplastic abundance, soil structure and organic carbon in a cotton field. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 356, 124367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Huang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Long, J.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Zhang, D. Effects of plastic film mulching on soil microbial carbon metabolic activity and functional diversity at different maize growth stages in cool, semi-arid regions. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1492149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Dannenmann, M.; Lin, S.; Saiz, G.; Yan, G.; Yao, Z.; Pelster, D.E.; Tao, H.; Sippel, S.; Tao, Y.; et al. Ground cover rice production systems increase soil carbon and nitrogen stocks at regional scale. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 4831–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.X.; Chang, Q.S.; Guo, Q.S. Different light-quality colored films affect growth, photosynthesis, chloroplast ultrastructure, and triterpene acid accumulation in Glechoma longituba plants. Photosynthetica 2023, 61, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, N.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Uwiragiye, Y.; Fallah, N.; Crowther, T.W.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; et al. Degradable film mulching increases soil carbon sequestration in major Chinese dryland agroecosystems. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Tang, Y.; Feng, S. Rice Cultivation under Film Mulching Can Improve Soil Environment and Be Beneficial for Rice Production in China. Rice Sci. 2024, 31, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F. Long-term plastic film mulching increased maize yield and water use efficiency. Field Crops Res. 2025, 333, 110105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Lai, H.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Yang, D.; Li, X. The impacts of soil tillage combined with plastic film management practices on soil quality, carbon footprint, and peanut yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 148, 126881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Feng, H.; Wu, S.; Meng, Q.; Siddique, K.H.M. Effects of organic amendments and ridge–furrow mulching system on soil properties and economic benefits of wolfberry orchards on the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 827, 154317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Wang, Z.; Huang, M.; Hui, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; He, H.; Zhang, X.; Diao, C.; Cao, H.; et al. Plastic film mulch increased winter wheat grain yield but reduced its protein content in dryland of northwest China. Field Crops Res. 2018, 218, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.S.; Le Gouis, J.; Daniel, D.; Brancourt-Hulmel, M. Optimal numbers of environments to assess slopes of joint regression for grain yield, grain protein yield and grain protein concentration under nitrogen constraint in winter wheat. Field Crops Res. 2009, 113, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.