Abstract

Estimated climate change scenarios demand robust coffee cultivars tolerant to supra-optimal temperatures, water deficit, diseases, and other stresses. Wild Coffea species represent important genetic resources for resilience. The study of variations in morphological structures associated with transpiration control, such as stomata, represents an important approach for identifying genotypes with greater stress tolerance. This study evaluated stomatal density and morphology in 48 wild accessions, 24 of Coffea racemosa and 24 of C. zanguebariae, from provinces of Mozambique. Leaf samples provided microscopic images to assess stomatal traits: density (SD), polar diameter (PD), equatorial diameter (ED), stomatal functionality (SF), and leaf dry mass. Principal components were analyzed for all 48 accessions and separately by species. Mean distribution independence was tested with the Mann–Whitney test (p < 0.05). Results revealed inter- and intraspecific variation. The ability to distinguish accessions varies with the set of traits and species. A significant negative correlation between ED and SF was shared by both species, suggesting a conserved functional pattern. This study discusses the differences in stomatal traits between wild and commercial coffee species and aspects related to possible alterations of stomatal structures during their adaptation to climate change. Additionally, it points to accessions with potential use in genetic breeding programs to increase stomatal function and the possible adaptation of new cultivars.

1. Introduction

The genus Coffea belongs to the Rubiaceae family and comprises at least 130 species [1]. Wild Coffea species show a morphological, genetic, and biochemical diversity, with some of which displaying better resistance to pests, diseases, and environmental constraints than C. arabica L. (Arabica coffee, with a wide number of cultivars) and C. canephora Pierre ex Froehner (Robusta coffee, dominated by Conilon and Robusta cultivars) that support the global coffee market [2,3].

Climate changes and global warming poses considerable challenges to coffee crop sustainability. The greater speed of temperature rise, climate instability, and change in rainfall temporal and spatial distribution [4,5] can endanger the adaptability of new cultivars in recent decades [6,7,8]. Under these scenarios, wild species constitute important genetic resources to develop new cultivars with greater resilience to climate change. In fact, underutilized wild coffee species, such as C. liberica Hiern., C. eugenioides Moore, C. racemosa Lour., and C. zanguebariae Lour., may have potential for economic exploration, helping to diversify the genetic base of coffee production, while offering new possibilities in genetic breeding programs [1,9]. The use of wild species may represent a key strategy to promote leaf anatomical modifications that improve plant adaptation to stress conditions, such as a reduction in stomatal density and an increase in stomatal efficiency [10].

In Mozambique, C. arabica has recently begun to be cultivated in regions with high edaphoclimatic diversity [11], but native species C. zanguebariae and C. racemosa (known as Inhambane coffee) [4,12] have been used for a long time. Despite the cultivation of native species, there remains the need for genotypes with higher productivity and adaptation to microregions and genetic diversity studies on the potential use of this material in breeding programs to guide strategies to develop new cultivars [13].

Commercial transactions in the German market in south-east Africa traded C. zanguebariae in 1893. Its cultivation began on Ibo Island (northeastern Mozambique) in 1920 as an indigenous variety of southern Tanzania, northern Zimbabwe, and northern Mozambique as a substitute for C. arabica [14,15]. The cultivation of C. zanguebariae on Ibo Island occurs in regions with an average annual rainfall of approximately 950 mm and an average annual temperature of 26 °C [4]. On the other hand, C. racemosa was described by Loureiro [12] based on a specimen of a herbarium sample from Mozambique. The originally identified species has been lost, being replaced by accessions from the district of Massingir (Gaza province) in southwestern Mozambique [15]. The name Inhambane coffee also commonly refers to C. racemosa, whose aroma quality has long been recognized [16], being related to the region of accession collection for this species: southern Mozambique [4]. This species cultivation occurs in regions with an average annual rainfall of approximately 807 mm and an average annual temperature of 22.9 °C [4].

Studies on the genetic divergence of coffee accessions, almost exclusively regarding C. arabica and C. canephora, are usually focused on agronomic phenotypic traits and ecophysiological characteristics, especially leaf anatomical variations [17,18,19]. This type of trait enables to assess the phenotypic plasticity or the adaptability of genotypes under intense environmental modifications [20]. These studies are essential to guiding plant breeding toward anatomical modifications that may favor the potential adaptation capability of new cultivars.

Variations in stomatal density and morphology have been reported in accessions of C. canephora and C. arabica [18,21,22], likely associated with distinct adaptation ability, even within species, although these species are more domesticated than C. zanguebariae and C. racemosa. In fact, stomatal control plays an important role in regulating gas exchange and water loss in plants, being directly influenced by variations in stomatal density and morphology [23]. Under environmental stress conditions such as drought, high temperatures, or excessive light, the ability to adjust stomatal density and aperture can lead to significant improvements in plant water-use efficiency [24]. Thus, genotypes with greater efficiency in this control tend to exhibit better physiological performance and increased resilience, especially in environments with irregular water availability or higher solar radiation intensity. Therefore, the analysis of stomatal traits represents a valuable tool for selecting more adaptable genetic materials, contributing significantly to breeding strategies in the face of climate change scenarios.

Thus, this study will provide newly information regarding stomatal traits of C. racemosa and C. zanguebariae accessions from Mozambique, and establish the following hypotheses: (i) stomatal density and morphology differ between C. racemosa and C. zanguebariae individuals, and (ii) differences in stomatal density and morphology occur at both interspecific and intraspecific levels.

2. Results

The evaluation of leaf traits indicated differences in the mean values among C. racemosa accessions (Table 1), as reflected by the wide amplitude of values among accessions, which exceeded the minimum significant difference. The equatorial diameter of the stomata (ED) had the highest coefficient of variation (CV) (60.5%), indicating greater variation in the equatorial diameter of stomatal cells among leaves of the same accessions. In contrast, stomatal density (SD) showed the lowest CV (25.2%), indicating the lowest variation in the structures between leaves of the same plant.

Table 1.

Evaluation of leaf dry mass (DM, g), stomatal density (SD, number of stomata mm2), equatorial diameter (ED, μm), polar diameter (PD, μm), and stomatal functionality (SF = PD/ED) from leaf samples collected in 24 accessions of Coffea racemosa. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation (n = 10).

Regarding dry mass (DM), the Cr2 genotype (0.15 g) showed a higher average than others, indicating a greater accumulation of biomass (Table 1). Conversely, Cr8, Cr10, Cr12, Cr15, Cr19, Cr23, and Cr24 (0.03 g) showed lower DM values, possibly associated with less favorable growth conditions or less efficient genetics.

In general, Cr8 showed the highest SD value (395.86), while Cr9 had the lowest mean value (116.25). This difference showed the possibility of adding Cr9, Cr17, and Cr20 into a group with statistically lower SD means than the others (Table 1). Regarding ED, the accessions Cr2, Cr1, Cr22, Cr21, Cr25, Cr17, Cr14, Cr15, Cr23, Cr24, and Cr9 showed higher absolute means, significantly differing from the other accessions. Moreover, ED showed the highest CV, evincing high variation, even in leaves of the same plant. Regarding polar diameter (PD), Cr 21, Cr2, Cr22, Cr15, and Cr17 showed a higher mean diameter than the others.

Considering stomatal functionality (SF), Cr1 and Cr2 had lower absolute means (Table 1), statistically differing from Cr8 and Cr10, which presented higher values.

As regards leaf traits in C. zanguebariae accessions, CV values (Table 2) remained relatively below those for C. racemosa (Table 1). Additionally, the amplitude between SD, ED, and SF means remained below the minimum significant difference, showing no statistically significant differences among the means.

Table 2.

Evaluation of leaf dry mass (DM, g), stomatal density (SD, number of stomata mm2), equatorial diameter (ED, μm), polar diameter (PD, μm), and stomatal functionality (SF = PD/ED) from leaf samples collected in 24 accessions of Coffea zanguebariae. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation (n = 10).

The highest DM was observed in Cz14 (0.23), a value that statistically differed from those for Cz11, Cz16, Cz22, Cz19, and Cz18, which had the lowest means of leaf dry mass (Table 2). Regarding PD, Cz3 (31.84) showed the highest value, indicating greater stomatal cell length, with a mean statistically similar to the other 13 accessions, which showed a mean above 27.88.

In general, the general means among the species showed that C. zanguebariae has a dry mass and stomatal size practically twice as large as C. racemosa. However, C. racemosa has higher density and stomatal functionality.

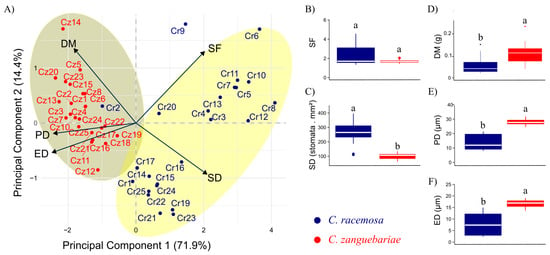

Considering both species together, the decrease in the initial variables for two principal components retained 86% (PC1 = 71.9% and PC2 = 14.4%) of the variability in the original dataset (Figure 1A). PD and ED showed a higher correlation with PC1, whereas DM, SF, and SD showed more balanced relations with the two components (despite a greater variation in the first component).

Figure 1.

Analysis of principal components (A) and boxplots (B–F) regarding five leaf traits in 48 accessions of Coffea belonging to two species: C. racemosa (Cr) and C. zanguebariae (Cz) sampled in Mozambique. DM: dry mass of leaves (g); SD: stomatal density (number of stomata mm2); PD: polar diameter of the stomata (μm); ED: equatorial diameter of the stomata (μm); SF: stomatal functionality. Different letters between the boxes (boxplot) indicate an independent distribution in the species according to the Mann–Whitney test at a significant level of 5%.

In the dispersion of accessions based on the evaluated traits, SD and SF constitute the main criteria for separating C. racemosa and C. zanguebariae accessions, as by projected them on opposite sides of the biplot. Accessions Cr8, Cr6, Cr10, and Cr12 stand out among those with the highest SD and SF. A single C. racemosa accession, Cr2, showed characteristics that brought it closer to C. zanguebariae accessions in the grouping, notably due to its lower SF and SD than the other accessions of its species.

This study obtained distinct subgroups of C. racemosa (Figure 1A): one with a higher SF and lower SD (Cr6 and Cr9), a second with higher SF and SD (Cr11, Cr10, Cr7, Cr5, Cr13, Cr4, Cr3, Cr8, and Cr12), a third with low SF and SD (Cr20 and Cr2), and finally, a subgroup with higher SD and lower SF (Cr17, Cr16, Cr14, Cr15, Cr1, Cr25, Cr24, Cr22, Cr19, Cr21, and Cr23).

The C. zanguebariae accessions showed a more clustered pattern, without clear subgroups (Figure 1A). Still, Cz 14 was separated from the others with the highest DM and lowest SD.

The SF failed to distinguish the two species (Figure 1B), but the SD displayed an independent distribution across species according to the Mann–Whitney test (Figure 1C). Except for Cr2 and Cr20, no other C. racemosa accession showed SD values as low as those of C. zanguebariae. DM behaved otherwise, as, despite the independent distribution, values overlapped between at least 50% of the accessions (Figure 1D). PD (Figure 1E) and ED (Figure 1F) showed a pattern similar of that of DM as regards lower values in C. racemosa, but with no or little overlap.

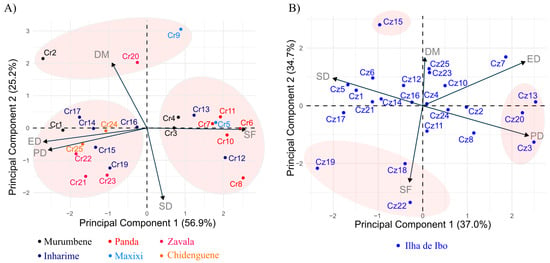

The individual dispersion of accessions in relation to the principal components by species (Figure 2) showed that the first two components represented 82.1% of the total variation for C. racemosa (Figure 2A) and 71.7% of the total variation for C. zanguebariae (Figure 2B). For C. racemosa, accessions such as Cr6, Cr11, Cr8, Cr12, Cr5, Cr7, and Cr13 showed higher SF, while others, such as Cr2, Cr20, and Cr9, showed similar DM. However, Cr9 had a higher SF and lower SD than the other two accessions. Conversely, accessions Cr1, Cr17, Cr14, Cr24, Cr16, Cr15, Cr25, Cr21, Cr22, Cr23, and Cr19 showed a higher PD and ED and lower SF. Notably, these groups of accessions did not correspond to the collection of single districts, since it included accessions from different districts (Figure 2A). The principal components showed a different pattern as regards C. zanguebariae: the first component gathered PD, ED, and SD, whereas the second component was strongly related to SF and DM (Figure 2B). However, as observed for C. racemosa, a lower discrimination occurred for DM and ED than for the other traits, with a total variation of less than two standard deviation units from the mean. Accessions Cz13, Cz20, and Cz23 had higher ED and DP and lower SD. Accessions Cz22, Cz19, and Cz18 showed higher SF, in which the SD of Cz19 exceeded that of the other two. Cz15 showed a higher DM and a high SD. Variations in SD, ED, and PD dispersed the other C. zanguebariae accessions.

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis for five leaf traits in 48 accessions of Coffea belonging to two species: (A) C. racemosa (Cr) and (B) C. zanguebariae (Cz), sampled in Mozambique. DM: dry mass of leaves (g); SD: stomatal density (number of stomata mm2); PD: polar diameter of the stomata (μm); ED: equatorial diameter of the stomata (μm); SF: stomatal functionality (PD/ED).

In C. racemosa, significant correlations were observed among stomatal traits (Table 3), notably a strong positive correlation between the ED and PD (r = 0.97; p < 0.01), as well as negative correlations between the ED and SF (r = −0.87; p < 0.01) and between the PD and SF (r = −0.77; p < 0.01). In C. zanguebariae, SD was negatively correlated with ED (r = −0.48; p < 0.05), and the ED also showed a negative correlation with SF (r = −0.61; p < 0.05). The negative correlation between ED and SF was the only significant relationship shared by both species, suggesting a conserved functional pattern.

Table 3.

Matrices with Pearson’s correlation coefficients between five leaf traits in two species of Coffea: C. racemosa and C. zanguebariae in Mozambique. DM: dry mass of leaves (g); SD: stomatal density (stomata mm2); PD: polar diameter of the stomata (μm); ED: equatorial diameter of the stomata (μm); SF: stomatal functionality (μm).

3. Discussion

This study evaluated traits related to the density and size of stomata in 48 accessions of Coffea of two wild species. The results showed greater variations among C. racemosa accessions than among C. zanguebariae ones (Figure 1A). However, this research found groups of accessions with different aptitudes for a certain number of traits within each species. Such studies of traits related to stomata can provide insights associated with the potential for adaptation of a given accession or species. Several studies of other species reported this phenomenon, obtaining evidence of possibly exploiting genetic effects linked to the adaptation of stomatal structures to increase the resilience of plants to climate change [25,26,27]. In fact, stomatal size and density are key determinants of maximum stomatal conductance, gs [28,29]. For example, in a wide number of species it was observed that elevated air CO2 concentration can alter stomatal traits and function, namely by reducing stomatal opening and reducing SD, thus reducing gs [30,31,32]. These findings evidence the potential and importance of prospecting stomatal traits from the wild accessions evaluated in the present study, aiming to incorporate climate change resilience into future coffee cultivars.

Regarding the potential of stomatal traits to discriminate accessions, the four traits (PD, ED, SD, and SF) were important for distinguishing species (vector length in Figure 1A). However, within species, SF contributed the most to discriminating accessions. This may occur because of the more pronounced negative correlation between SF and PD or ED in C. racemosa compared with C. zanguebariae, in addition to the strong positive correlation between PD and ED in C. racemosa compared with the weaker correlation observed in C. zanguebariae (Table 3). In other words, in C. racemosa, higher PD values result in higher ED values and consequently lower SF values, whereas in C. zanguebariae, this tendency is less evident. The ratio between PD and ED, which determines SF, can vary under water deficit conditions, as demonstrated by Melo et al. [33]. In an assessment of the Siriema coffee cultivar under both water-stressed and non-stressed conditions, notable contrasts in ED and PD were observed: PD increased while ED decreased under water deficit, resulting in a rise in SF from 1.46 to 1.75 [33]. These findings support the use of SF as a parameter to infer the potential adaptation of genotypes to water-limited environments.

In C. racemosa, several accessions stood out for their combination of high stomatal density (SD) and elevated stomatal functionality (SF), traits that may be associated with greater gas exchange capacity and faster stomatal responses. Studies about SF in model plants reported that SF (as result of stomatal size structures) may represent an important indicator of plant responses to environmental stresses, as higher SF values suggest an enhanced capacity for CO2 uptake per stomatal opening [34]. This characteristic can contribute to increased rates of CO2 assimilation while minimizing water loss during stomatal activity. Accessions such as Cr8, Cr6, and Cr10 exhibited a combination of high SD and SF, simultaneously, suggesting greater efficiency in transpiration regulation under variable environmental conditions. Studies in rice, wheat, and Arabidopsis have shown that smaller, more elongated stomata (with higher PD/ED ratios) promote better control over transpiration and faster closure [35,36].

Accordingly, accessions Cr6 and Cr8, which combine small stomata with high functionality, may reflect a similar anatomical mechanism with adaptive potential under drought. In contrast, C. zanguebariae accessions showed larger stomata, lower density, and reduced functionality. Despite the higher dry mass observed in some accessions (such as Cz14), this set of traits may indicate a lower capacity for transpiration control, associated with a greater number of stomata per leaf and a higher potential for water loss during stomatal opening [37].

Findings in Coffea spp. also reported some changes promoted by elevated air CO2, but with species-dependent impacts on SD reduction, and an almost invariant gs [21,38]. Furthermore, stomatal traits can also respond to other environmental conditions in Coffea spp. Studies on C. arabica have showed that SD tends to increase with the increase in photosynthetically active radiation [39]. Also, high temperatures can promote changes in a species-dependent manner. These included increases in SD and stomatal index in C. canephora cv. Conilon CL153, whereas the opposite patterns were observed in C. arabica genotypes [17,40]. These findings were suggested to reflect different temperature sensing of stomata among Coffea species/genotypes, with implications for the control of transpiration (together with stomata opening extend) and, thus, of water-use efficiency.

High levels of anatomical differences among species of Coffea, including C. racemosa, C. arabica, and C. liberica, also point to relevant phenotypic plasticity [41]. Studies on variation in stomatal structures between accessions within species have also reported variability in C. arabica and C. canephora [18,22,42]. However, studies on the intraspecific variation in traits related to the anatomy of stomata involving C. racemosa or C. zanguebariae remain scarce in the literature. Regarding the possibility of relating phenotypic variation to phenotypic plasticity (the ability of an organism to modify its phenotype in response to environmental changes), Valladares et al. [43], in a review on methodologies for quantifying phenotypic plasticity, emphasized the nonlinearity in the relationship between variation and plasticity. Although phenotypic variation is a prerequisite for phenotypic plasticity within a population, conclusions about the potential plasticity of the accessions investigated here can only be drawn after studies assess their performance across multiple environments.

In a study with 43 genotypes of C. canephora in Brazil, Dubberstein et al. [22] showed the mean values of 282 stomata per mm2 of leaf area, with a mean equatorial diameter of 25.7 μm and a mean polar diameter of 16.9 μm. Pérez-Molina et al. [18], in a study with genotypes of C. arabica var. Catucaí, indicated an average stomatal density of 158 stomata per mm2 of leaf area. Considering these values as a reference, the stomatal density values in this study showed that C. zanguebariae had a lower stomatal density than the C. arabica and C. canephora commercial cultivars, and a stomatal functionality close to that of C. canephora (Table 2). C. racemosa has a stomatal density close to C. canephora (262.8 stomata per mm2) and greater stomatal functionality (2.27) (Table 1). This may indicate greater adaptive plasticity and water-use efficiency in C. racemosa, reinforcing its potential as a donor of alleles for drought tolerance in breeding programs. Indeed, this species has already been identified as a source of desirable traits, such as early fruit maturation, drought resistance [44,45], and greater tolerance to pests [46].

The correlation analyses support these interpretations. In both species, the negative correlation between stomatal equatorial diameter (ED) and stomatal functionality (SF) indicates a conserved functional pattern, in which narrower stomata tend to be more elongated, favoring greater control over transpiration. This relationship aligns with patterns reported in species adapted to water-stressed environments [29,47]. Similar structural adaptations were also observed in Pancratium maritimum, a coastal species exhibiting unique inter-stomatal connections composed of pectins and extensins, which appear to modulate stomatal aperture and enhance water-use control under harsh conditions [48]. Therefore, the levels of modification observed in leaf structures, such as stomatal density and morphology, may represent promising targets for future research aiming to deepen the understanding of the transmission potential of these traits in breeding crosses and to evaluate the enhancement of adaptive capacity in these genotypes.

Genetic divergence studies between different species of Coffea have shown a considerable difference between C. racemosa × C. zanguebariae [4] and between C. racemosa × C. arabica [3]. However, comparative studies between C. zanguebariae and commercial species seem scarce. The differences among C. racemosa accessions in this study corroborate the possibility of high intraspecific genetic diversity, including stomatal density and morphology traits (Figure 1A). On the other hand, the smallest intraspecific variation among C. zanguebariae accessions may suggest a lower genetic variation for these traits. However, it should be underlined that this study had limitations regarding the scope of its collection area, especially for C. zanguebariae. Thus, complementary studies that integrate anatomical, molecular, physiological, and environmental data will be essential for a more accurate assessment of the genetic variability of C. racemosa and C. zanguebariae. This integrated approach may support more effective strategies for the development of cultivars with enhanced resilience to climate-related stresses.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Characterization of the Experimental Area

From 2023 to 2024, randomly distributed samples of wild populations were collected at their natural sites in southern Mozambique for C. racemosa in Chidenguele (Gaza province), Murumbene, Maxixi, Inharrime, Panda, and Zavala (all from Inhambane province), and in northeastern Mozambique for C. zanguebariae on Ibo Island (Cabo Delgado province), with the specific coordinates identified at the collection sites gives in Table 4. Specimens from the National Herbarium were also searched at the Institute of Agrarian Research of Mozambique (created in 1967) to obtain additional information on habitat, vegetation, environment, morphology, and cultivation. The sampled plants are commonly collected by local harvesters and used either for self-consumption or for sale in local markets.

Table 4.

Localization of the collected of 24 accessions of C. racemosa (Cr) and 24 accessions of C. zanguebariae (Cz) from several regions in Mozambique.

4.2. Dry Mass and Leaf Anatomy

Samples of C. racemosa were collected in December 2023 and those C. zanguebariae in February 2024, all during the fruit maturation phase. All leaf samples were collected from different positions around the plant, using the third and/or fourth pair of leaves (counted from the apex) from plagiotropic branches in the middle-third part of the plant canopy. For leaf dry mass estimation (DM, g), eight leaves were used per plant (each plant corresponds to an accession). For the determination of dry mass, the leaves were kept in a forced-air oven at 60 °C until a constant mass was observed. The final value of DM was obtained from the mean of eight sampled leaves.

For anatomical analysis, two additional leaves from each accession were used. To obtain epidermal impressions, a solution of colorless enamel was fixed in the central part of the leaf for five minutes. After drying, they were mounted on semi-permanent slides with transparent adhesive tape. These epidermal leaf imprints were then examined and documented, using an optical microscope (Optika Microscopes Italy (Ponteranica, Italy), Model: B-290TB, magnification = 40×) and photographed with an attached camera. Five distinct and randomly selected points on the abaxial surface of the leaf epidermis were sampled for each slide, totaling 10 images per plant. Thus, the data of this study considered 480 images of leaf epidermis (240 for each wild species). The images were evaluated using Anati Quanti2 software (version 2.0) [49] for the following traits: stomatal density (the number of stomata per mm2—SD); polar diameter of the stomata (PD, μm); equatorial diameter of the stomata (ED, μm); and stomatal functionality (SF). They were expressed using the ratio between polar and equatorial diameters, following Castro et al. [50].

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Data on dry mass (DM) and stomatal parameters were expressed as means and standard deviations for each accession (24 of C. racemosa and 24 C. zanguebariae). The minimum significant distance to define the differences between means was estimated according to HSD Tukey’s test at a 5% significance level (α = 0.05). Based on the means, the five variables were standardized for principal component analysis (PCA). The first two principal components were used to construct boxplot charts. A PCA was first carried out for all 48 accessions. Then, subsequent PCAs were performed for each accession. The independence between the species datasets was tested using the Mann–Whitney test at a 5% significance level.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between pairs of traits within each species were also estimated and tested using the t-test at a 5% significance level. The analyses and construction of graphs were carried out on R Core Team [51] based on the functions available in the stats, extra fact, and ggplot2 packages.

5. Conclusions

The wild species C. racemosa and C. zanguebariae differ in their stomatal density and morphology. Individuals of C. racemosa tend to have higher density and stomatal functionality compared to those of C. zanguebariae. At the intraspecific level, C. racemosa accessions show more pronounced variation than C. zanguebariae accessions. The findings confirm the two initial hypotheses of this research and show wild accessions with potential use in coffee breeding programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.J.A., L.O.E.S. and F.L.P.; Field collection and laboratory analysis, N.J.A., G.L., A.F.S., T.F.H., S.J.J., and S.A.B.; Formal analysis, N.J.A., L.O.E.S., J.C.R. and F.L.P.; Resources, F.L.P.; Data curation, N.J.A., L.O.E.S., J.C.R. and F.L.P.; Writing—original draft preparation, N.J.A., L.O.E.S., J.C.R. and F.L.P.; Writing—review & editing, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received funding support from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Espírito Santo—FAPES (Proc. 2022-WTZQP and Proc. 2024-9H43M for F.L.P.; Proc. 2022-M465D for L.O.E.S.) and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—CNPq (Proc. 309535/2021-2 for F.L.P.), United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), OIKOS Institute, Lúrio University, Association of Coffee Producers of Ibo-Cabo Delgado, Coffee Producers of Inhambane and Gaza, Institute of Agricultural Research of Mozambique, the Agrarian Institute of Panda—Inhambane. Support provided by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. (FCT), Portugal, through the projects CEF (UIDB/00239/2020, https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00239/2020), GeoBioTec, (UIDP/04035/2020, https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04035/2020), and the Associate Laboratory TERRA (LA/P/0092/2020, https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0092/2020) to J.C.R. is also greatly acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Davis, A.P.; Rakotonasolo, F. Six new species of coffee (Coffea) from northern Madagascar. Kew Bull. 2021, 76, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICO-International Coffee Organization-Monthly Coffee Market Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.ico.org/documents/cy2024-25/cmr-0525-e.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Tapaça, I.D.P.E.; Mavuque, L.; Corti, R.; Pedrazzani, S.; Maquia, I.S.; Tongai, C.; Partelli, F.L.; Ramalho, J.C.; Marques, I.; Ribeiro-Barros, A.I. Genomic evaluation of Coffea arabica and its wild relative Coffea racemosa in Mozambique: Settling resilience keys for the coffee crop in the context of climate change. Plants 2023, 12, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.P.; Gargilo, R.; Almeida, I.N.M.; Caravela, M.I.; Denison, C.; Moat, J. Hoot Coffee: The identity, climate profiles, agronomy, and beverage characteristics of Coffea racemosa and C. zanguebariae. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 740137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W.; Nayak, M.A.; Azam, M.F. Intensifying spatially compound heatwaves: Global implications to crop production and human population. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 932, 172914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, S.C.; Chakraborty, S.; Dreccer, M.F.; Howden, S.M. Plant adaptation to climate change: Opportunities and priorities in breeding. Crop Pasture Sci. 2012, 63, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromdijk, J.; Long, S.P. One crop breeding cycle from starvation? How engineering crop photosynthesis for rising CO2 and temperature could be one important route to alleviation. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20152578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palit, P.; Kudapa, H.; Zougmore, R.; Kholova, J.; Whitbread, A.; Sharma, M.; Varshney, R.K. An integrated research framework combining genomics, systems biology, physiology, modelling and breeding for legume improvement in response to elevated CO2 under climate change scenario. Curr. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.P.; Chadburn, H.; Moat, J.; O’Sullivan, R.; Hargreaves, S.; Nic, L.E. High extinction risk for wild coffee species and implications for coffee sector sustainability. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, aav3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitaloka, M.K.; Caine, R.S.; Hepworth, C.; Harrison, E.L.; Sloan, J.; Chutteang, C.; Phunthong, C.; Nongngok, R.; Toojinda, T.; Ruengphayak, R.; et al. Induced genetic variations in stomatal density and size of rice strongly affects water use efficiency and responses to drought stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 801706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, T.M.; Reckziegel, R.B.; Paulino, J. Soil organic carbon in tropical shade coffee agroforestry following land-use changes in Mozambique. Agrosys Geosci. Environ. 2025, 8, e70043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, J. Flora Cochinchinensis; Ulyssipone, Typis, et Expensis Academicis: Lisbon, Portugal, 1790. [Google Scholar]

- Navarini, L.; Scaglione, D.; Del Terra, L.; Scalabrin, S.; Mavuque, L.; Turello, L.; Nguenha, R.; Luongo, G. Mozambican Coffea accessions from Ibo and Quirimba Islands: Identification and geographical distribution. AoB Plants 2024, 16, plae004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridson, D.M.; Polhill, R.M.; Verdcourt, B. “Coffea” in Flora of Tropical East Africa, Rubiaceae; East African Governments: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 703–723. [Google Scholar]

- Bridson, D.M. “Coffe” in Flora Zambesiaca; Pope, G.V., Ed.; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Richmond, UK, 2003; pp. 452–463. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcellos, E. Catálogo da Exposição Colonial—Algodão, Borracha, Cacau e Café; Sociedade de Geographia de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 1906; 138p. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, W.P.; Silva, J.R.; Ferreira, L.S.; Machado Filho, J.A.; Figueiredo, F.A.; Ferraz, T.M.; Bernado, W.P.; Bezerra, L.B.S.; Abreu, D.P.; Cespom, L.; et al. Stomatal and photochemical limitations of photosynthesis in coffee (Coffea spp.) plants subjected to elevated temperatures. Crop Pasture Sci. 2018, 69, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Molina, J.P.; de Toledo Picoli, E.A.; Oliveira, L.A.; Silva, B.T.; de Souza, G.A.; Santos Rufino, J.L.; Pereira, A.A.; Ribeiro, M.F.; Malvicini, G.L.; Turello, L.; et al. Treasured exceptions: Association of morphoanatomical leaf traits with cup quality of Coffea arabica L. cv. “Catuaí”. Food Res. Inter. 2021, 141, 110118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.O.E.; Schmidt, R.; Almeida, R.N.; Feitoza, R.B.B.; Cunha, M.; Partelli, F.L. Morpho-agronomic and leaf anatomical traits in Coffea canephora genotypes. Ciênc. Rural 2023, 53, e20220005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompelli, M.; Martins, S.; Celin, E.; Ventrella, M.; DaMatta, F. What is the influence of ordinary epidermal cells and stomata on the leaf plasticity of coffee plants grown under full-sun and shady conditions? Braz. J. Biol. 2010, 70, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, J.C.; Rodrigues, A.P.; Semedo, J.N.; Pais, I.P.; Martins, L.D.; Simões-Costa, M.C.; Leitão, A.E.; Fortunato, A.S.; Batista-Santos, P.; Palos, I.M.; et al. Sustained photosynthetic performance of Coffea spp. under long-term enhanced [CO2]. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubberstein, D.; Oliveira, M.G.; Aoyama, E.M.; Guilhen, J.H.; Ferreira, A.; Marques, I.; Ramalho, J.C.; Partelli, F.L. Diversity of leaf stomatal traits among Coffea canephora Pierre ex A. Froehner genotypes. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haworth, M.; Marino, G.; Materassi, A.; Raschi, A.; Scutt, C.P.; Centritto, M. The functional significance of the stomatal size to density relationship: Interaction with atmospheric [CO2] and role in plant physiological behaviour. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Ding, R.; Du, T.; Kang, S.; Tong, L.; Li, S. Stomatal conductance drives variations of yield and water use of maize under water and nitrogen stress. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 268, 107651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, L.C.; Lau, O.S. Stomatal development in the changing climate. Development 2024, 151, dev202681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.L.; Erberich, J.M.; Lopez, L.; Weiß, C.L.; Amador, G.; Fung, H.F.; Latorre, S.M.; Lasky, J.R.; Burbano, H.A.; Expósito-Alonso, M.; et al. Century-long timelines of herbarium genomes predict plant stomatal response to climate change. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 1641–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Z.; Ma, G.; Bai, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, M.; Su, L.; Zhou, H. The influence of leaf anatomical traits on photosynthesis in Catimor type Arabica coffee. Beverage Plant Res. 2024, 4, e002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, F.I.; Kelly, C.K. The influence of CO2 concentration on stomatal density. New Phytol. 1995, 13, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, P.J.; Beerling, D.J. Maximum leaf conductance driven by CO2 effects on stomatal size and density over geologic time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 10343–10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, F.I. Stomatal index are sensitive to increase in CO2 from pre-industrial levels. Nature 1987, 327, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Rogers, A. The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO2]: Mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possell, M.; Hewitt, C.N. Gas exchange and photosynthetic performance of the tropical tree Acacia nigrescens when grown in different CO2 concentrations. Planta 2009, 229, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, E.F.; Fernandes-Brum, C.N.; Pereira, F.J.; Castro, E.M.D.; Chalfun-Júnior, A. Anatomic and physiological modifications in seedlings of Coffea arabica cultivar Siriema under drought conditions. Ciênc. Agrotec. 2014, 38, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, L.T.; Caine, R.S.; Gray, J.E. Impact of stomatal density and morphology on water-use efficiency in a changing world. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittberner, H.; Korte, A.; Mettler-Altmann, T.; Weber, A.P.; Monroe, G.; Meaux, J. Natural variation in stomata size contributes to the local adaptation of water-use efficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 4052–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Dun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D.; Xiong, D.; Cui, K.; Peng, S.; Huang, J. Effect of stomatal morphology on leaf photosynthetic induction under fluctuating light in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 754790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennajeh, M.; Vadel, A.M.; Cochard, H.; Khemira, H. Comparative impacts of water stress on the leaf anatomy of a drought-resistant and a drought-sensitive olive cultivar. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, W.P.; Martins, M.Q.; Fortunato, A.S.; Rodrigues, A.P.; Semedo, J.N.; Simões-Costa, M.C.; Pais, I.P.; Leitão, A.E.; Colwell, F.; Goulao, L.; et al. Long-term elevated air [CO2] strengthens photosynthetic functioning and mitigates the impact of supra-optimal temperatures in tropical Coffea arabica and C. canephora species. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, F.S.; Wolfgramm, R.; Gonçalves, F.V.; Cavatte, P.C.; Ventrella, M.C.; DaMatta, F.M. Phenotypic plasticity in response to light in the coffee tree. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 67, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, W.P.; Vieira, H.D.; Teodoro, P.E.; Partelli, F.L.; Barbosa, D.H.S.G. Assessment of genetic divergence among coffee genotypes by Ward-MLM procedure in association with mixed models. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, R.; Cardoso, A.A.; Silva, M.M.; Oliveira, L.A.; Avila, R.T.; Martins, S.C.; DaMatta, F.M. Leaf hydraulic properties are decoupled from leaf area across coffee species. Trees 2020, 34, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto, N.J.; Ferreira, A.; Barros, A.I.R.; Aoyama, E.M.; Silva, L.O.E.; Rakocevic, M.; Ramalho, J.C.; Partelli, F.L. Plant morphological and leaf anatomical traits in Coffea arabica L. cultivars cropped in Gorongosa Mountain, Mozambique. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Sanchez-Gomez, D.; Zavala, M.A. Quantitative estimation of phenotypic plasticity: Bridging the gap between the evolutionary concept and its ecological applications. J. Ecol. 2006, 94, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazuoli, L.C.; Maluf, M.P.; Filho, O.G.; Filho, H.M.; Silvarolla, M.B. Breeding and biotechnology of coffee. In Coffee Biotechnology and Quality, Proceedings of the 3rd International Seminar on Biotechnology in the Coffee Agro-Industry, Londrina, Brazil; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Geromel, C.; Ferreira, L.P.; Bottcher, A.; Pot, D.; Pereira, L.F.P.; Leroy, T.; Vieira, L.G.E.; Mazzafera, P.; Marraccini, P. Sucrose metabolism during fruit development in Coffea racemosa. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2008, 152, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.C.; Souza, B.H.; Carvalho, C.H.; Guerreiro Filho, O. Characterization and levels of resistance in Coffea arabica × Coffea racemosa hybrids to Leucoptera coffeella. J. Pest. Sci. 2025, 98, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sack, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, K.; Zhang, Q.; He, N.; Yu, G. Relationships of stomatal morphology to the environment across plant communities. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridis, P.; Georgiadou, X.; Shtein, I.; Pouris, J.; Panteris, E.; Rhizopoulou, S.; Constantinidis, T.; Giannoutsou, E.; Adamakis, I.-D.S. Stomata in Close Contact: The Case of Pancratium maritimum L. (Amaryllidaceae). Plants 2022, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, T.V.; Sant’Anna-Santos, B.F.; Azevedo, A.A.; Ferreira, R.S. Anati Quanti: Software de análises quantitativas para estudos em anatomia vegetal. Planta Daninha 2007, 25, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, E.M.; Pereira, F.J.; Paiva, R. Histologia Vegetal: Estrutura e Função dos Órgãos Vegetativos; Ed. da UFLA: Lavras, Brazil, 2009; 234p. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).