Abstract

Accurately classified surface water datasets are critical for hydrological modeling, environmental monitoring, and water resource management. Most large-scale datasets are raster-based, produced through pixel-level classification. Existing global vector datasets often struggle to capture small water bodies and maintain global consistency. Therefore, extracting vector features from Earth observation raster products and performing fine-grained classification is a promising approach, but fragmentation and the lack of object-level semantic labels remain key challenges. This study, based on the JRC Global Surface Water dataset, proposes a low-fragmentation global-scale vector dataset for river and lake classification. Our workflow integrates a fragment-aggregating strategy with a water body classification model. Specifically, we implemented a three-stage aggregation process using GIS-based hydrological constraints, classification buffering, and neighbor analysis to reduce fragmentation. A deep learning classifier combining convolutional feature extraction with Transformer-based contextual reasoning performs contour-informed classification of water bodies. Experiments show that the aggregation strategy reduces water body fragmentation by nearly 60%, while the classifier achieves an F1 score of 92.4%. These results demonstrate that our approach provides a transferable solution for constructing surface water classification datasets, delivering valuable resources for remote sensing, ecology, and hydrological decision-making.

1. Introduction

Surface water bodies are critical land cover types and surface features that support ecosystems, water resource assessment, and environmental evaluation. High-quality surface water body data not only provide support for understanding the current state of global water resources, but also serve as key inputs for model construction in various fields, such as hydrological simulation and prediction, disaster early warning and assessment, water body monitoring and management, and ecosystem protection and restoration [1,2]. Furthermore, factors such as climate change, rapid urbanization, population growth, and environmental degradation have led to a gradual reduction in global water resources [3,4], thus strengthening researchers’ demand for global-scale surface water body datasets with high spatial and semantic granularity.

Currently, global surface water datasets primarily come from remote sensing and are in raster format, which is a direct output of pixel classification. Raster data, due to its ease of processing and storage, is widely used in earth observation. However, in certain scenarios, such as hydrological network and topological relationship analysis, and GIS-based spatial analysis, vector data, with its clear topological structure, high geometric precision, and ability to store attribute information, is the preferred choice. Raster data inevitably stores background information and is difficult to manage at the object level, thus posing challenges to both storage and analysis. In the case of surface water datasets, vector-based data has the advantages of clear water body boundaries, ease of dynamic updates, and the ability to include semantic labels, making it essential for detailed-scale hydrological and water resource work.

Several global vector datasets of surface water currently exist, such as HydroRivers [5] and HydroLakes [6], which are primarily derived from HydroSHEDS [7], a gridded dataset with a resolution of 500 m that lacks coverage above 60° N latitude. The SRTM Water Body Data [8] offers higher positional accuracy but is limited to latitudes between 56° S and 60° N. The GRNWRZ V2.0 [9] employs an effective partitioning and coding method to generate multi-level river networks based on SRTM and ASTER GDEM data, but it only includes rivers and excludes other types of water bodies.

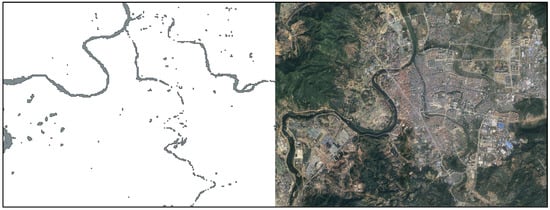

Existing surface water vector datasets face challenges in terms of coverage, spatial resolution, update frequency, and the representation of small water bodies. These limitations highlight the need for extracting and classifying surface water bodies from high-resolution remote sensing products through vectorization. However, two major challenges remain in this process: (1) The extraction process inevitably introduces a massive number of fragmented water body features, as shown in Figure 1, which hinder subsequent analysis due to broken connectivity and increased computational costs; (2) Vector features extracted from gridded data lack object-level semantic information, limiting their value for classification and interpretation.

Figure 1.

Example of fragmented water bodies introduced by vectorization include disconnected narrow river fragments, wide river and lake edge fragments, and isolated fragments.

These fragmented water bodies are often difficult to fully identify and integrate using traditional algorithms, which affects both classification quality and the reliability of downstream models [10,11]. Existing research addressing water body fragmentation and subtype classification primarily includes rule-based methods, object-oriented segmentation, and deep learning approaches. While some successes have been achieved through hydrological modeling in specific regions and methods based on high-resolution imagery, most approaches either lack scalability at the global level or are limited by computational inefficiency and insufficient performance in data-scarce regions. Furthermore, few studies have systematically addressed the structural reconstruction of fragmented water bodies before classification, especially when dealing with river fragmentations and isolated micro-fragments.

To solve these issues, we propose and implement an integrated methodological framework for post-processing surface water imagery datasets and develop a global-scale vector dataset for the classification of surface water bodies. Specifically, first we applied a three-stage progressive aggregation method that systematically reduced fragmentation by combining hydrological constraints, classification buffers, and topological neighbor analysis. We then developed a hybrid deep learning classification model, named Hybrid CNN-Transformer Classifier (HCTC), which combines local spatial feature extraction with global context reasoning to differentiate rivers from lakes. Through this process, we propose a Global Surface Water Classification Vector Dataset, v1.0 (GSWCVD v1.0).

The contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- We propose a method for extracting vector features from surface water remote sensing observation data products and constructing a water body classification vector dataset. The surface water classification model we developed demonstrated good classification performance.

- We establish a global surface water classification vector dataset based on the JRC GSW dataset, which provides better spatial completeness and semantic classification attributes for rivers and lakes.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses existing research and methods for handling fragmented water body features and surface water classification; Section 3 provides a detailed description of the data sources used in this study, the proposed progressive aggregation method, and the deep learning-based classification model; Section 4 presents the cross-validation and classification experimental results; Section 5 summarizes the contributions of the method, discusses its limitations, and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Work

2.1. Defragmentation Strategy

Fragmentation is a common issue in global surface water mapping. In many satellite-derived surface water datasets, continuous water systems are often incorrectly represented as numerous disconnected independent patches, particularly in narrow river networks, deltas, river-lake connections, and arid regions. Discontinuous pixel classification results can lead to severe fragmented water body issues during the vectorization process.

Apart from a small number of genuine surface small water bodies, most fragmentation arises from errors during the remote sensing identification process. The causes primarily involve physical mechanisms and technical limitations [12]. Physical mechanisms include factors such as significant seasonal water level changes in some water bodies, shadowing during satellite imaging, and high turbidity water bodies having infrared reflectance similar to land. Technical limitations primarily refer to defects in image segmentation algorithms and the mixed pixel effect. Many methods have been proposed to address the issue of surface water fragmentation. For example, dynamically adjusting the convolution kernel size based on the fragment area, or merging fragments based on high-confidence water pixels and spectral similarity thresholds, but these methods struggle to handle complex boundary situations [13]. Using deep learning networks based on specific structures to achieve multi-scale information fusion for enhancing water body segmentation has significantly improved water body identification accuracy in complex terrains, but this method relies heavily on high-resolution remote sensing images [14]. Combining digital elevation models and hydrological analysis to determine whether fragmented water bodies are of the same origin can effectively recover water bodies cut off by bridges, dams, and other infrastructure, but this approach lacks generalizability [15,16]. Improving water occurrence thresholds based on water body characteristics, considering differences between actual historical water distribution data and the data to be processed, and combining water body features for judgment, provides high accuracy with a favorable accuracy-to-computation cost ratio. This method has great potential for wider application, but it has significant limitations in terms of time scale and depends on real data [17]. Using multi-source remote sensing images and pixel-level data fusion, along with semi-empirical thresholds to generate surface water body extents, is effective in eliminating cloud-covered images and performs well in many complex areas. However, for areas with low soil reflectance, such as fallow farmland and alluvial zones in certain regions, as well as desert areas lacking verification points, this method may misclassify non-water pixels as water, leading to high false positive rates [18].

Overall, existing methods have certain limitations [19], nearly all of them suffer from critical limitations when scaled to global extent. Physical/hydrological methods rely on additional high-quality auxiliary datasets that are either unavailable or inconsistent at a global scale, which leads to unstable performance. Morphological image processing methods are prone to change the shape of water features, which directly impact classification results. And deep learning driven multi-scale fusion methods dramatically increase computational cost. Therefore, when conducting global-scale water body defragmentation, we tend to analyze from a more fundamental perspective, and geo-knowledge-based constraints and hierarchical treatment approaches may have advantages in terms of cost-effectiveness. Developing aggregating strategies based on the spatial distribution patterns of fragmented water bodies through spatial analysis is crucial for mitigating their negative impact on classification results.

2.2. Water Body Subclassification

In the field of remote sensing water body classification, current research primarily focuses on two directions: threshold-based classification methods and classification methods based on machine learning and deep learning. Early efforts to distinguish water body subclasses from remote sensing images relied mainly on manual visual interpretation and historical data. However, these methods were inefficient and difficult to apply in areas lacking historical data [20]. Some rule-based methods use geometric features and empirically defined thresholds for automatic classification, but their parameters lack generalizability across different sensors and regions [21,22,23]. Additionally, these methods have lower accuracy when processing connected water body regions.

The rise of machine learning and deep learning techniques in image analysis and pattern recognition has significantly advanced water body classification [24,25], making data-driven approaches the mainstream path in water body classification research [26,27]. Among these approaches, CNNs (Convolutional Neural Networks) have been widely applied. For example, MRSE-Net [28], based on a CNN and an encoder–decoder architecture, demonstrates strong feature extraction capabilities. By introducing the SE attention mechanism, it greatly enhances the continuity of water body boundaries and achieves over 90% average accuracy in water body classification tasks using multi-source remote sensing images such as Landsat and Sentinel. W-Net [29,30], an end-to-end multi-feature fusion structure based on CNN, captures contextual information through a contracted network and achieves an IoU accuracy of 89% with only 2000 training samples. Many studies [1,31,32] have shown that integrating various morphological feature data and optimizing model architecture can significantly improve the recognition ability and generalization performance of water body classification models in complex scenarios. Recently, there have also been studies on surface water body extraction and classification based on shape and morphological methods, which have yielded promising results. For example, Ref. [33] employed mathematical morphological operators and an unsupervised approach to extract surface water bodies from a single band, achieving satisfactory outcomes. This fully demonstrates that contour information alone provides sufficient information for water body classification tasks.

In general, few studies focus on using more universal rules to handle fragmented water bodies. While many CNN-based methods have been proposed for water body classification, few studies have applied them to global-scale water body subclassification tasks. Even fewer studies systematically address the combined challenge of fragmentation and subclass labeling within a unified framework.

3. Materials and Methods

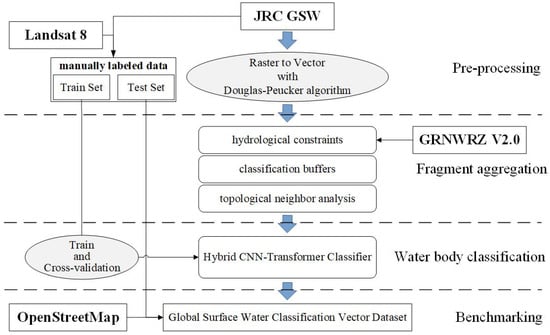

The source data used in this study is the JRC Global Surface Water (GSW) [34] dataset, specifically, we used the JRC Global Surface Water Mapping Layers, v1.4 Extent data product. Additionally, the GRNWRZ V2.0 [9] global river network dataset was used as auxiliary data, and for certain regions, Landsat 8 [35] imagery was employed as a reference for manual water body type labeling. During the process of extracting vectors from raster data, we applied the classic Douglas-Peucker algorithm for edge simplification to reduce vertex redundancy in the vector features. The deep learning classifier used was a hybrid architecture combining CNN and Transformer. Finally, partial manually labeled data and OSM data from certain regions were used as standards for benchmarking against the classification results. Figure 2 illustrates the workflow and the data used.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for constructing a global surface water classification vector dataset based on remote sensing data products. Solid rectangular boxes represent datasets, elliptical boxes represent computational steps, and rounded rectangular boxes represent the fragment aggregation and water body classification methods. Thin arrows denote data input flow.

3.1. Source Data and Pre-Processing

The JRC Global Surface Water (GSW) dataset is one of the most widely used global surface water remote sensing data products. Developed by the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission based on Landsat series satellite imagery, it covers a 34-year time span from 1987 to 2020 at a spatial resolution of 30 m. The dataset provides multiple products, including annual classifications, occurrence frequency, and seasonality indices, and serves as a fundamental resource for studying surface water dynamics.

The preprocessing stage mainly involved data format conversion, optimization, and label annotation. This stage consisted of multiple steps: (1) Collecting global surface water remote sensing data products and converting them into vector format; (2) Applying a contour simplification algorithm to smooth and simplify features; (3) Selecting representative regions for manual labeling to provide training and testing datasets for the classifier.

In this study, we used the JRC Global Surface Water Mapping Layers, v1.4 Extent as the primary dataset. This product includes all surface water bodies detected by JRC over the monitoring period. It consists of 504 raster tiles, each covering a 10° × 10° area, collectively spanning from 60° S to 80° N. The product contains a single band, in which the pixel values of 1 represent water, 0 represents no water, and 255 represents no data. After excluding tiles without water pixels, 353 raster files remained. Based on pixel values and the Douglas–Peucker algorithm, we were able to vectorize water bodies and simplify vertices efficiently.

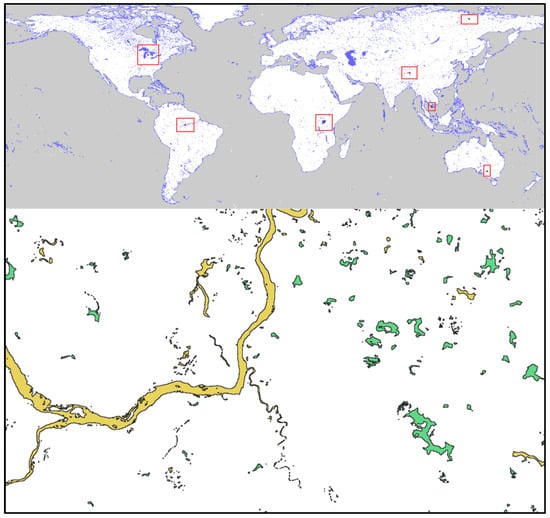

According to [34,36], we selected seven representative regions: the Amazon River floodplain, the Mekong Delta, parts of the Tibetan Plateau, parts of the Arctic Circle, the East African Rift Lakes Region, parts of Australia, and the North American Great Lakes Region. A detailed description of these regions is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected regions for manual labeling to construct training and testing datasets for the classifier. The chosen regions were distributed globally and selected to ensure representativeness.

Within these seven regions, manual classification and labeling of surface water vector features were performed. An example is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the seven selected regions on the full raster imagery and examples of manual annotations. The red boxes indicate the locations of the seven regions. And yellow represents river features, and green represents lake features.

3.2. Aggregation of Fragmented Water Bodies

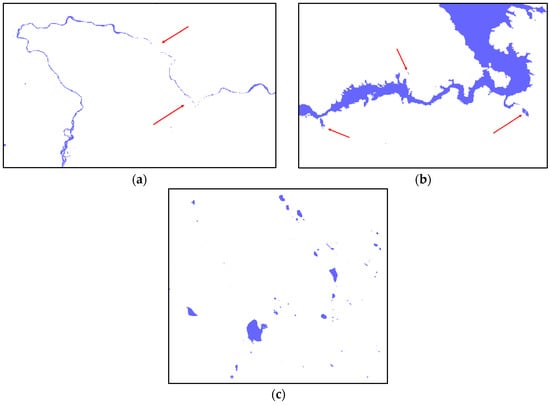

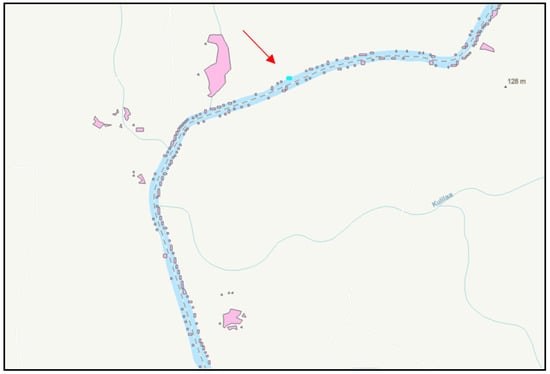

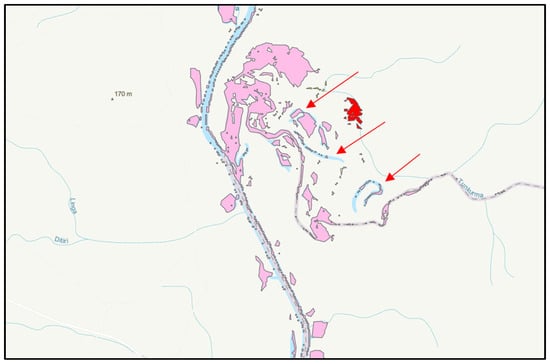

The fragmented features from vectorization process can be categorized into three main types: disconnected narrow river fragments, wide river and lake edge fragments, and isolated fragments. Figure 4 illustrates typical examples of these three categories.

Figure 4.

(a) Disconnected narrow river fragments; (b) Wide river and lake edge fragments; (c) Isolated fragments. Red arrows indicate examples of these fragmented features.

To address these three types of fragmentation, we adopted a three-stage approach to identify and aggregate fragmented water bodies. This is a progressive, multi-tiered feature integration strategy that transitions from strong constraints based on a priori knowledge to weaker constraints based on spatial neighbor relationships. The method consists of three stages, “river network constraint—classification buffer—topological neighbor”, and is designed to systematically restore the spatial integrity of global water landscapes while minimizing mis-aggregation errors.

In the first stage, we employed the GRNWRZ V2.0 global river network dataset to restore hydrological connectivity disrupted by narrow river fragmentations. GRNWRZ V2.0 provides a seven-level classification system based on river basin characteristics: L1 represents rivers draining into the same ocean or inland basin, L2 distinguishes exorheic basins by drainage area or endorheic basins by catchment extent, while L3–L7 are further subdivided according to decreasing basin size [9]. Through comparative experiments and analysis, we found that the L5 river network data strikes a balance: it ensures coverage of all major rivers within the study area while effectively distinguishing between interconnected lakes and independent rivers.

A 150 m buffer was constructed around the river network, and all water body features within this buffer were labeled as rivers. Fragmented water bodies intersecting the buffer were assumed to originate from the corresponding river, and fragments within the same buffer zone were considered hydrologically related. Figure 5 shows a schematic diagram of the aggregation strategy. The main rationale behind this step is that narrow river fragments are usually derived from the river itself, either as a result of seasonal water level fluctuations or as errors introduced during remote sensing extraction. This stage is particularly effective in addressing linear fragmentation along narrow river channels and reconstructing the continuity of original river features.

Figure 5.

River network-constrained fragment aggregation strategy. Pink polygons represent water body features, the light blue area indicates the river network buffer, and the red arrow points to an example of a target fragment. Aggregating the narrow river fragments through the buffer. The main objective is to restore hydrological connectivity in narrow, fragmented river channels.

In the second stage, to address wide river and lake edge fragments, we applied a classification buffer approach. In this stage, a 180 m buffer was created around water body features labeled as rivers in the first stage, while a 120 m buffer was constructed for unlabeled water body features. Fragments whose buffers intersected were aggregated into the same feature. Figure 6 illustrates the aggregation strategy. The underlying principle is that two or more spatially proximate water body fragments are highly likely to have originated from the same continuous water system. Similarly, extremely small fragments along the edges of larger rivers or lakes are very likely to be part of the same water body, primarily due to remote sensing observation errors. This stage effectively reduces fragmentation in independent water body data.

Figure 6.

Classification buffer aggregation strategy. Pink polygons represent water body features, the light blue areas indicate the buffers, and red arrows point to examples of fragments to be aggregated. The main goal is to eliminate noise along the edges of large water surfaces.

In the third stage, aimed at addressing isolated fragments, we employed a GIS-based nearest neighbor analysis. In this stage, water body features not labeled as rivers after the first two stages were analyzed using neighborhood relationships and a distance threshold. The goal was to enhance global connectivity and improve the classification value of very small water bodies. In reality, small water bodies are often separated by bridges, walkways, ditches, or appear fragmented in remote sensing imagery due to clouds, shadows, snow/ice, or noise. This stage is designed to handle fragmentation of relatively isolated water body features. A distance threshold of 150 m was set, and nearest neighbor searches were conducted using Euclidean distance. Figure 7 illustrates the aggregation strategy. The main principle is that geographically adjacent water body fragments are often homologous in natural formation processes. Aggregating small nearby fragments before classification improves practical relevance and ensures greater logical consistency.

Figure 7.

Fragment aggregation strategy based on neighbor analysis. The main objective is to reduce fragmentation of isolated water bodies. Fragments of the same color belong to the same aggregated water body object, and the red circles highlight examples of these aggregated fragments.

It is worth noting that to ensure metric accuracy during geometric operations, we mitigated the projection distortion inherent in the source WGS 1984 geographic coordinate system (EPSG:4326) by dynamically projecting each tile to its corresponding UTM zone based on the tile’s centroid . The selection criteria are described in Equations (1) and (2).

In these equations, represents the longitude of the tile center, and represents the latitude of the tile center. UTM divides zones at 6° intervals, with EPSG codes ranging from 32,601 to 32,660 in the Northern Hemisphere and from 32,701 to 32,760 in the Southern Hemisphere. After processing, all vector features were reprojected back to WGS 1984.

These three steps can significantly reduce the number of fragmented water bodies. The combination of hydrological priors and spatial reasoning enables this method to be reliably applied under diverse climatic and topographic conditions. The aggregated water body dataset produced through this process forms a solid foundation for subsequent river and lake classification. Furthermore, although this strategy for mitigating fragmentation at the global scale cannot guarantee perfectly accurate aggregation results, the aggregation operations do not significantly alter the shape factors of independent water body fragments. In other words, they do not affect subsequent classification results, making this a highly reliable aggregation approach.

3.3. Subtype Classification of Water Bodies

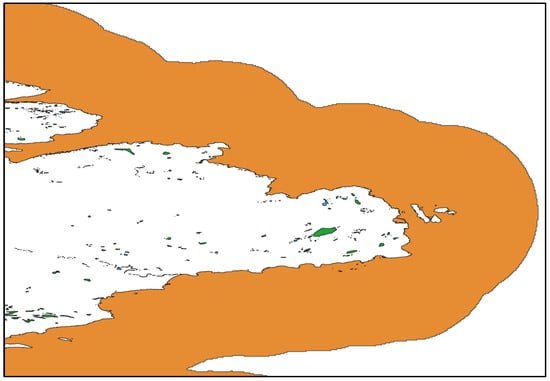

Surface water body subtypes generally include rivers, lakes, wetlands, canals, and others. In this study, only rivers and lakes are considered. Surface water bodies were classified into these two primary subtypes based on morphological characteristics, hydrological dynamics, and limnological properties. Lakes are defined as relatively stationary natural or artificial water bodies, surrounded by land, and typically replenished by precipitation, groundwater, or inflowing rivers. Water is discharged from lakes either through evaporation or outflowing rivers, and their surface area can range from 0.03 km2 to several tens of thousands of km2. Rivers, in contrast, are continuous and directional, flowing from high to low elevations and ultimately discharging into oceans, lakes, or other water bodies. Rivers are usually elongated and meandering in shape. Detailed definitions of each subtype are provided in Table 2. Other water body subtypes and potential directions for future research are discussed in detail in Section 5. In addition, the final classification results in this study include an “Other” category, which does not correspond to actual surface water. This category primarily represents buffers established along land coastlines in the JRC GSW dataset, as shown in Figure 8.

Table 2.

Definition of subtypes of water bodies in this research.

Figure 8.

Buffers established along land coastlines in the JRC GSW dataset (the orange area). These do not represent real surface water and can be filtered out by the classifier and will be excluded in the final mapping product.

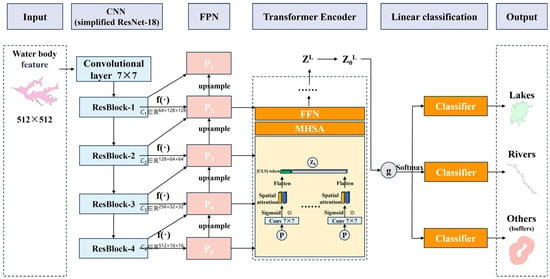

To achieve fine-grained classification of surface water body subtypes, we employed a hybrid CNN-Transformer architecture classifier, referred to as the Hybrid CNN-Transformer Classifier (HCTC). This model combines the local feature extraction capability of CNNs with a lightweight Transformer architecture capable of capturing long-range spatial dependencies and contextual relationships. The network architecture of HCTC is illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Structure of the HCTC. The method uses a simplified ResNet-18 network as the feature extractor, incorporating multi-scale fusion via a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN), spatial attention mechanisms to highlight key regions, and Transformer modules for global context modeling. Different colors differentiate the functional modules of the network, and arrows indicate the direction of data flow, and the ellipsis indicates that the Spatial Attention mechanism is applied identically to all multi-scale feature levels.

This hybrid design is specifically intended to handle the complexity of water body contours: rivers are typically elongated and meandering, whereas lakes tend to be more rounded and enclosed. The model employs a simplified ResNet-18 network, with the average pooling and fully connected layers removed, retaining only the feature extraction portion. Features from different levels are projected to a unified channel dimension using 1 × 1 convolutions and then upsampled layer by layer for top-down fusion. Subsequently, a spatial attention mechanism emphasizes important regions, and a Transformer encodes the global context, compensating for the local limitations of the CNN. The aggregated features are finally fed into a linear classification head for three-class prediction: rivers, lakes, and other.

All water body features are resampled to 512 × 512 images for input to the model. Initial low-level features are obtained through a 7 × 7 convolution followed by max pooling, and multi-level features are progressively extracted through the four residual blocks of ResNet-18.

In which , , , and .

To leverage information at multiple scales, we adopted the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) concept. Features from different layers are projected to a unified dimension through 1 × 1 convolutions and then progressively upsampled in a top-down manner and summed. Specifically, the high-level semantic features are upsampled and added to the corresponding low-level detailed features to generate the multi-scale feature maps :

where denotes the 1 × 1 convolution mapping. This results in a set of multi-scale fused features , which incorporate both low-level details and high-level semantic information. Then we apply the spatial attention mechanism independently to each feature map to enhance salient regions and suppress irrelevant areas:

where represents the attention-enhanced feature maps, denotes the convolution operation, is the Sigmoid activation, is the attention weight map, and denotes element-wise multiplication. This process highlights water body boundaries and main shapes while attenuating interference.

Each attention-enhanced feature map is flattened into a sequence of tokens. These sequences are then concatenated to form a unified multi-scale sequence. Since the number of tokens from low-level features (high resolution) is significantly larger than that from high-level features, there is a risk of semantic information being overwhelmed. To address this, we prepend a learnable [CLS] token to the sequence. Learnable positional encodings are added to retain spatial structure information. The final input to the Transformer is defined as

The Transformer encoder then processes this sequence. Through the multi-head self-attention (MHSA) mechanism, the [CLS] token dynamically interacts with tokens from all scales, aggregating the most relevant features for classification—whether they are fine-grained boundaries from or global shapes from . Finally, the output state of the [CLS] token will be used for the final prediction.

Each encoder layer consists of an MHSA and an FFN. The number of Transformer encoder layers was set to 4. This depth was empirically determined to strike an optimal balance between capturing global contextual dependencies and maintaining computational efficiency, while avoiding overfitting on the available dataset.

The multi-head self-attention is formulated as

where , , , and are learnable parameters. is the scaling factor. The update of an encoder layer can be expressed as

The final global context representation is the output sequence of the last encoder layer. We extract the first token (corresponding to the [CLS] token) as the global semantic representation of the water body:

Finally, the object-level global feature vector is fed into a classification head, consisting of a linear transformation and a softmax activation, to yield the predicted probabilities:

where , are parameters of the classification layer. And is the final classification results.

The overall model architecture and principles are as described above. The model was trained and tested on manually labeled data from the 7 regions introduced earlier. The manually labeled dataset contains over 1300 Lake instances, over 600 River instances, and only 78 Other instances corresponding to coastal buffer areas. Due to the extreme class imbalance, weighted cross-entropy was applied during training to mitigate the issue. The class weights were set as

These weights were calculated based on the inverse square root of the sample counts for each class. Additional hyperparameter settings of the model are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Partial hyperparameter settings of the model.

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of Fragmented Water Body Aggregation

We evaluated the quality of the aggregated water body dataset by comparing the degree of fragmentation before and after applying the three-stage aggregating strategy. The evaluation was conducted in the previously selected and manually labeled 7 regions. By referring to the Landsat 8 imagery used during the manual labeling stage, we determined the number of fragmented water bodies that were correctly aggregated into their corresponding surface water body objects. Three evaluation metrics were used: Aggregating Rate, Aggregating Accuracy, and False Aggregating Rate. The Aggregating Rate is defined as the proportion of fragmented water bodies reduced by the aggregating operation relative to the total number of fragments. Aggregating Accuracy and False Aggregating Rate, respectively, denote the proportion of correctly and incorrectly aggregated fragments relative to the total number of fragments reduced through aggregating. The quantitative results for each of the three stages across the test regions are presented in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 4.

Aggregation results of river network constraint in labeled regions.

Table 5.

Aggregation results of classification buffering in labeled regions.

Table 6.

Aggregation results of neighbor analysis in labeled regions.

It can be observed that the three-stage aggregating strategy significantly reduced the number of fragmented water bodies, while keeping the overall False Aggregating Rate below 12%. More specifically, the river network constrained stage, which imposed the strongest prior constraints, achieved the highest number of correctly aggregated fragments, owing to the guidance provided by hydrological priors. In contrast, the neighbor analysis stage exhibited the highest relative False Aggregating Rate. This outcome mainly arises from the fact that, in reality, very small water bodies that are geographically close are not necessarily hydrologically connected, meaning that fragmentation is inherently higher in certain regions. On the other hand, treating these small, nearby but unconnected fragments as a single water object can still provide analytical and observational value. Moreover, although the proximity analysis stage produced the highest false aggregating rate, the absolute number of affected fragments was relatively small, since most fragmented water bodies were instead associated with disconnected river segments or large water surface edges. Overall, the three-stage aggregating strategy proves to be a robust approach for mitigating fragmentation in global surface water data products. Compared to methods that rely on high-quality auxiliary data or additional computational costs, this approach we proposed utilizes only two publicly available global datasets and relies solely on GIS-based spatial analysis to achieve robust global-scale surface water fragment aggregation. This ensures high computational efficiency and complete reproducibility while maintaining a low false aggregation rate.

In addition, to determine the optimal parameter settings for the aggregation strategy, we conducted a parameter sensitivity analysis, focusing on the trade-off between aggregation quality and error rates.

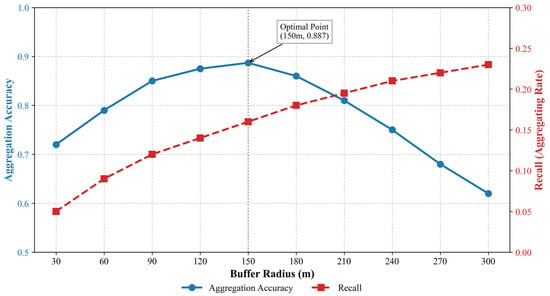

Figure 10 illustrates the impact of varying the buffer radius on the performance of the river network constraint stage. The experiments were conducted with buffer radii ranging from 30 m to 300 m, set at intervals of 30 m to align with the spatial resolution of the source raster data.

Figure 10.

Impact of buffer radius on defragmentation performance in the first stage of aggregation.

As shown in the figure, the Recall (red line) exhibits a continuous upward trend as the buffer radius increases, indicating that wider buffers capture more fragmented water bodies. However, the Aggregation Accuracy (blue line) follows an inverted V-shape trend. Initially, accuracy improves as the buffer effectively covers spatial deviations inherent in the raster vectorization process. The accuracy peaks at 0.887 when the buffer radius is 150 m. Beyond this point, the accuracy declines sharply. This drop occurs because an excessively large buffer begins to incorrectly aggregate hydrologically independent water bodies—such as floodplain lakes or adjacent ponds—into the river network, thereby introducing significant noise.

Based on these quantitative results, 150 m was selected as the optimal threshold for the river network constraint, as it maximizes the correct identification of river fragments while maintaining a low false aggregation rate.

For the subsequent stages, unlike the systematic deviation correction in Stage 1, the aggregation logic relies on local geometric proximity, which exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity. Therefore, instead of seeking a global optimum via sensitivity analysis, we employed a resolution-constrained approach. Additionally, a detailed discussion regarding this aspect, as well as future research directions, is provided in Section 5.3.

4.2. Evaluation of Subtype Classification

To evaluate the generalization capability of HCTC across diverse geographical regions, we employed a leave-one-region-out 7-fold cross-validation strategy. As shown in Table 7, the model achieved a mean accuracy of 94.92% with a standard deviation of ±0.71%, demonstrating robust cross-regional performance. Subsequently, we trained the model on data from all seven regions, randomly selecting 10% of the samples for testing, and compared HCTC with several established deep learning models. The results are shown in Table 8.

Table 7.

Cross-validation results. In each fold of the 7-fold cross-validation, data from six regions were used for training, while the remaining region was held out as the test set to evaluate the model’s generalization performance.

Table 8.

Comparison of classification performance of different models. The model was trained on all manually labeled data, with 10% of the data randomly selected for testing. Bold values indicate the best performance in each column.

As shown in Table 8, HCTC outperformed almost all models across the three evaluation metrics, achieving an Accuracy of 93.28%, a Recall of 91.54%, and an F1 score of 92.40%. HCTC demonstrated outstanding classification capability, thereby supporting the overall reliability of the dataset. Its superior performance can be attributed to the complementarity between the local features extracted by the ResNet-18 backbone and the global contextual information captured by the Transformer Encoder and spatial attention mechanism. The latter effectively compensates for the limitations of CNNs in modeling large-scale river network topological structures. It is worth noting that although the ViT model achieved a slightly higher Recall of 92.65% compared to HCTC, its lack of convolutional inductive bias resulted in unstable performance on certain underrepresented objects, such as narrow rivers. This ultimately resulted in fluctuations of up to nearly four percentage points in the F1 score across multiple experiments. In contrast, HCTC exhibited greater stability, with fluctuations of all three metrics remaining within three percentage points. Slightly higher variability was observed in the leave-one-region-out cross-validation, which can be attributed to shared characteristics within individual regions. However, considering the dataset scale, HCTC is the most suitable and robust model.

To verify the effectiveness of the key components in our proposed HCTC method, specifically the integration of the Transformer architecture, the FPN, and the Spatial Attention mechanism, we conducted a series of ablation experiments. We designed four variants to evaluate the contribution of each module:

- ResNet-18 (CNN Baseline): A pure CNN model using ResNet-18 as the backbone, followed by global average pooling and a linear classification head, without any Transformer components.

- HCTC w/o FPN: A model that uses the Transformer encoder but operates only on the single-scale feature map from the last layer of the backbone, removing the multi-scale fusion.

- HCTC w/o Attention: A model that includes both FPN and Transformer but excludes the spatial attention mechanism, directly flattening and concatenating the feature maps.

- HCTC (Full Model): The proposed full architecture integrating ResNet-18, FPN, Spatial Attention, and the Transformer encoder.

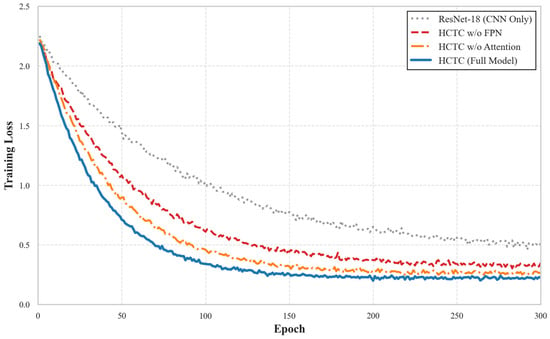

The results are presented in Table 9. The baseline ResNet-18 achieved an F1 score of 85.12%, showing clear limitations in distinguishing complex water bodies due to its restricted receptive field. Introducing the Transformer structure together with FPN (w/o Attention) already brought a noticeable improvement, raising the F1 score to 88.65%. This demonstrates that even without spatial attention, the ability of the Transformer to capture long-range dependencies and the multi-scale representations provided by FPN help the model better separate rivers from lakes and recognize fragmented water boundaries. When Spatial Attention is removed but FPN is retained (w/o FPN → w/o Attention comparison), the F1 score further increases to 90.90%. The gain mainly comes from the multi-scale fusion capability of FPN, which enriches the semantic content of feature tokens before they are sent to the Transformer. This indicates that multi-scale information contributes more significantly to classification performance than local spatial reweighting. Finally, adding the Spatial Attention mechanism (Full Model) yields the best performance, reaching an F1 score of 92.40%. This confirms that filtering noisy background responses before feature serialization enables the Transformer to concentrate more effectively on meaningful topological structures of water bodies. And Figure 11 shows how the training loss decreases as the number of epochs increases in the ablation study.

Table 9.

Ablation study on different components of the HCTC.

Figure 11.

Training loss convergence curves for different model variants. The HCTC (Full Model) demonstrates the fastest convergence rate and the lowest final loss, validating the effectiveness of the integrated architecture.

5. Discussion

Vector datasets of surface water bodies extracted from raster-based products can effectively address the incompleteness of existing datasets and represent a promising approach for future dataset construction. And a robust water body classifier can efficiently and accurately provide object-level semantic information. In this study, we developed a strategy based on GIS and spatial analysis principles to aggregate fragmented water bodies from vector datasets derived from the JRC GSW product. Furthermore, we constructed a deep learning classifier with a hybrid CNN–Transformer architecture to categorize vectorized water polygons. Validation against manually labeled data confirmed the effectiveness of our approach. Consequently, we present the Global Surface Water Classification Vector Dataset V1.0 (GSWCVD V1.0).

5.1. Fragment Aggregation Strategy

In global surface water mapping, fragmentation caused by discontinuous pixel-level classification results is an inevitable issue, and it is unrealistic to expect a complete solution through manual, rule-based, or heuristic approaches. However, applying a progressive fragmentation aggregation strategy—moving from strong priors to weaker spatial constraints—has proven to be a highly reliable way to mitigate fragmentation. First, based on hydrological priors, fragmented river segments aligned with known river features can be aggregated into continuous river objects, achieving significant progress in reconstructing narrow and fragmented rivers. Nevertheless, in complex riverine environments or regions with sparse river networks, such as the Mekong Delta and the North American Great Lakes region, the number of fragments that can be aggregated is very limited in this step. Therefore, the next step is to design a buffering-based method grounded in the principle of spatial autocorrelation to aggregate fragmented water bodies. This step primarily targets small fragments distributed along the edges of wide water surfaces. Finally, by applying nearest neighbor analysis to aggregate isolated fragments and construct new hydrological connectivity, the overall degree of fragmentation can be further reduced.

Validation with manually labeled data demonstrates that this three-stage progressive aggregation strategy can reduce fragmentation by nearly 60% while keeping the overall False Aggregation Rate below 12%. This not only substantially decreases the computational burden of subsequent classification (one of the main obstacles in this study and similar work) but also enhances the overall value of the classification results.

5.2. Water Body Classification

In terms of water body classification, we introduced the Hybrid CNN-Transformer Classifier (HCTC). This model combines the local feature extraction capability of CNNs with the long-range contextual reasoning ability of Transformer. Specifically, we integrated ResNet-18 with a Feature Pyramid Network to extract multi-level features, which are further processed via spatial attention and multi-head self-attention mechanisms. Experimental results demonstrate that this strategy outperforms conventional baselines, including plain CNNs and pure Vision Transformers (ViT), achieving significant improvements in distinguishing morphologically complex riverine features. Finally, we provided the GSWCVD V1.0 dataset. Admittedly, the current binary classification simplifies the hydrological reality, inevitably generalizing transitional features such as reservoirs or seasonal wetlands. Nevertheless, this object-level vector dataset provides a distinct advantage over raster products for dynamic monitoring. By encapsulating water bodies as discrete vector objects, it enables the precise tracking of morphological evolution thereby offering actionable insights for assessing the impacts of global climate change on water resources.

It is also worth noting that GSWCVD V1.0 occupies a distinct position compared with existing mainstream global vector datasets such as HydroRivers and HydroLakes, making direct quantitative comparison methodologically challenging. For example, HydroRivers focuses on major river networks and is composed of line features representing river centerlines, while HydroLakes focuses on static water bodies larger than 0.1 km2. In contrast, GSWCVD V1.0 is a pixel-derived vector dataset based on Earth observation imagery, inherently capturing finer-grained details and dynamic ephemeral waters that are often omitted or generalized in static hydrological databases. Therefore, a systematic quantitative comparison would be difficult to implement and potentially misleading; instead, these datasets serve complementary roles. As a result, rather than a replacement, GSWCVD V1.0 serves as a complementary resource that meets the need for fine-grained water body information and object-level semantic classification.

The rationale behind selecting a hybrid architecture over currently mainstream pure ViT variants (such as Swin Transformer [37]) lies in the specific scientific nature of river-lake classification. While window-based architectures like Swin Transformer have achieved state-of-the-art results in general vision tasks, they face limitations in this specific domain for two reasons:

First, from a morphological perspective, rivers are often characterized by elongated, meandering shapes with high aspect ratios. Window-based attention mechanisms partition the image into local grids, which risks severing the spatial connectivity of long rivers in the early feature extraction stages. In contrast, HCTC employs a standard Global Self-Attention mechanism after the CNN backbone. This ensures that the connectivity between distant parts of a water body—such as a wide, lake-like river segment and its connected narrow channels—is explicitly modeled within the global context, which is crucial for correct subtype identification.

Second, from the perspective of data efficiency and inductive bias, surface water classification datasets typically lack the massive scale of datasets like ImageNet-21k. As observed in Section 4.2, the pure ViT baseline exhibited high recall but relatively lower stability (lower precision and F1 score) compared to HCTC. This fluctuation can be attributed to the lack of intrinsic inductive biases (e.g., locality and translation invariance) in pure Transformers, making them prone to overfitting or instability on smaller datasets. The ResNet backbone in HCTC introduces these necessary inductive biases, ensuring rapid convergence and robust generalization even with limited training samples. Furthermore, considering the computational cost for global-scale mapping, the lightweight HCTC offers a superior trade-off between accuracy and efficiency compared to heavy ViT models.

5.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Work

Future work will mainly focus on three aspects: the further refinement of the fragmentation aggregation strategy, the development of more fine-grained water body classification methods, and the deep integration of the two at the global scale.

For the aggregation strategy, a critical issue lies in the choice of buffer widths and distance thresholds. Given the massive data volume at the global scale, these parameters are difficult to determine solely through comparative experiments and validations, which calls for more precise design. Since the source JRC GSW dataset has a spatial resolution of 30 m, the relevant parameters must be set as multiples of 30 m. If the buffer is too wide, non-river water bodies near rivers may be incorrectly aggregated into river features, whereas if it is too narrow, fragmented edges of wide rivers may not be adequately covered. Currently, the aggregation parameters for classification buffering and neighbor analysis are set as fixed global thresholds based on the spatial resolution of the source raster. While this heuristic approach provides a robust baseline, it does not account for the spatial heterogeneity of global water bodies. Since the aggregation strategy relies on fixed distance thresholds, it may perform poorly in extreme arid zones, where seasonal river interruptions often create dry gaps exceeding the buffer width, leading to under-aggregation. Conversely, in dense urban water networks or paddy field regions, high spatial proximity may cause distinct water bodies to be incorrectly merged.

The optimal aggregation threshold is highly dependent on diverse factors, including local topography, climatic zones, and human interventions. Therefore, conducting a simple global sensitivity analysis to find a “one-size-fits-all” parameter for these stages provides limited scientific value. Future research will focus on developing spatially adaptive aggregation algorithms. By incorporating auxiliary variables such as terrain slope, water recurrence frequency, and regional climate classifications, we aim to dynamically adjust buffer widths and neighbor distance thresholds, thereby addressing the complex non-linear relationships between fragmentation patterns and geographic environments.

On the other hand, at the global scale of vector extraction and dataset construction, the large data volume poses a major challenge, making parameter settings in the edge simplification stage—used to reduce redundant vertices—equally important. In general, edge simplification algorithms include area-threshold, angle-threshold, and distance-threshold methods. However, area-threshold approaches tend to substantially alter polygon shapes, while angle-threshold methods perform inconsistently when applied to elongated features, making both unsuitable for this work. Distance-threshold methods are more appropriate but still impose additional burdens. Both the JRC GSW dataset and the GSWCVD V1.0 proposed in this study are based on EPSG:4326 (WGS 1984), the most widely used geographic coordinate system. As a geocentric system expressed in angular units, EPSG:4326 introduces severe projection distortions across latitudes. To address this issue, this study re-projects map tiles into appropriate UTM coordinate systems during simplification. Looking ahead, projection-aware analyses and parameter designs represent a promising direction for further research.

With respect to water body classification, although our model achieved excellent results in distinguishing rivers from lakes, extending this approach to more complex categories such as wetlands, and reservoirs remains challenging. The primary limitation lies in relying solely on contour features for classification, which inherently constrains the model’s capacity. In fact, while vector datasets hold unique value, the process of deriving vector features from raster data inevitably discards surface and background information that could be highly informative for object-level classification.

Relying solely on contour features constrains the model’s ability to distinguish transitional or ambiguous morphologies. For instance, reservoirs often exhibit river-like branching combined with lake-like surface areas, leading to potential misclassification. Similarly, narrow, elongated tectonic lakes or oxbow lakes may be misidentified as river segments due to their high aspect ratios. These cases highlight the necessity of incorporating texture and background information in future iterations.

An optimal classification framework should therefore include three stages: (1) pixel-level classification based on raster data; (2) object-level classification guided by vector contour features; (3) rule-based integration of the two results. This constitutes a key direction for our future research and the design principle of subsequent dataset versions. Moreover, such fine-grained classification methods could also guide the design of fragmentation aggregation strategies. As discussed in Section 4, aggregating isolated small water bodies is particularly challenging, and this is precisely where surface and background information could provide valuable support.

Overall, we believe that the GSWCVD V1.0 dataset and its construction methodology hold substantial potential for applications in surface water dynamics analysis, water resource management and allocation modeling, ecological and biodiversity studies, remote sensing training data, decision support, and public management platforms. Looking ahead, we plan to further refine the fragmentation aggregation strategy and expand the water body classification workflow, with the ultimate goal of providing a more accurate and semantically detailed global surface water body classification vector dataset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Dinan Wang, Pengxiang Li and Zeqiang Chen; methodology, Dinan Wang and Pengxiang Li; validation, Dinan Wang; investigation, Pengxiang Li; resources, Dinan Wang and Pengxiang Li; data curation, Dinan Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Dinan Wang; writing—review and editing, Zeqiang Chen and Weibo Su; supervision, Zeqiang Chen and Weibo Su; project administration, Weibo Su; funding acquisition, Weibo Su. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2021YFF0704400), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41971351, 42001372).

Data Availability Statement

The produced Global Surface Water Classification Vector Dataset, v1.0 are (will be) openly available at: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17179940.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used DeepSeek-R1 for the purposes of language polishing and checking grammar only. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. Additionally, this work was aided by the use of open-source software, including QGIS 3.40.12 and Python 3.10 libraries such as rasterio, GDAL, Shapely, and GeoPandas for data processing. We thank the open-source community for its significant contributions and support to scientific research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Rishikeshan, C.; Ramesh, H. An automated mathematical morphology driven algorithm for water body extraction from remotely sensed images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 146, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogno, P.; Klein, I.; Kuenzer, C. Remote sensing of surface water dynamics in the context of global change—A review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi Garajeh, M.; Haji, F.; Tohidfar, M.; Sadeqi, A.; Ahmadi, R.; Kariminejad, N. Spatiotemporal monitoring of climate change impacts on water resources using an integrated approach of remote sensing and Google Earth Engine. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, F.; Livneh, B.; Rajagopalan, B.; Wang, J.; Cretaux, J.F.; Wada, Y.; Berge-Nguyen, M. Satellites reveal widespread decline in global lake water storage. Science 2023, 380, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B.; Grill, G. Global river hydrography and network routing: Baseline data and new approaches to study the world’s large river systems. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 27, 2171–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messager, M.L.; Lehner, B.; Grill, G.; Nedeva, I.; Schmitt, O. Estimating the volume and age of water stored in global lakes using a geo-statistical approach. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B.; Verdin, K.; Jarvis, A. New global hydrography derived from spaceborne elevation data. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2008, 89, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA JPL. NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Water Body Data Shapefiles & Raster Files [Data Set]; NASA JPL: La Cañada Flintridge, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Dong, B.; Fan, J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; et al. A data set of global river networks and corresponding water resources zones divisions v2. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Fan, L.; Zhao, J.; Huang, S.; Geiß, C.; Wang, L.; Taubenböck, H. Mapping of small water bodies with integrated spatial information for time series images of optical remote sensing. J. Hydrol. 2022, 614, 128580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Fan, L.; Wu, Y.; Sun, W.; Yang, G. Recognition of small water bodies under complex terrain based on SAR and optical image fusion algorithm. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R. Water body extraction from high spatial resolution remote sensing images based on enhanced U-Net and multi-scale information fusion. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Gao, G.; Huang, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D. Extraction of water bodies from high-resolution remote sensing imagery based on a deep semantic segmentation network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Xiang, L.; Steffen, H.; Jia, L.; Deng, F.; Wang, W.; Hu, K.; Guo, J.; Nong, A.; Cui, H. A new and robust index for water body extraction from Sentinel-2 imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Brakenridge, G.R.; Kettner, A.; Bates, B.; Nelson, J.; McDonald, R.; Huang, Y.F.; Munasinghe, D.; Zhang, J. Estimating floodwater depths from flood inundation maps and topography. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2018, 54, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, I.; Uereyen, S.; Sogno, P.; Twele, A.; Hirner, A.; Kuenzer, C. Global WaterPack-The development of global surface water over the past 20 years at daily temporal resolution. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Pi, X.; Luo, Q.; Li, W. Reconstruction of long-term high-resolution lake variability: Algorithm improvement and applications in China. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 297, 113775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markert, K.N.; Williams, G.P.; Nelson, E.J.; Ames, D.P.; Lee, H.; Griffin, R.E. Dense Time Series Generation of Surface Water Extents through Optical–SAR Sensor Fusion and Gap Filling. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, D.; Wang, L.; Li, D. Enhancing surface water mapping and monthly dynamics monitoring with a stepwise gap-filling method. Int. J. Digit Earth 2024, 17, 2413882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Z. Water body classification from high-resolution optical remote sensing imagery: Achievements and perspectives. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 187, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, O.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Lu, F. The performance of Landsat-8 and Landsat-9 data for water body extraction based on various water indices: A comparative analysis. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. Remote-sensing extraction of small water bodies on the loess plateau. Water 2023, 15, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulbure, M.G.; Broich, M.; Stehman, S.V.; Kommareddy, A. Surface water extent dynamics from three decades of seasonally continuous Landsat time series at subcontinental scale in a semi-arid region. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 178, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, J. MFCA-Net: A deep learning method for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, K.; Wang, L.; Su, F.; Chen, X. Semantic segmentation of high-resolution remote sensing images based on a class feature attention mechanism fused with Deeplabv3+. Comput. Geosci. 2022, 158, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Fang, Y.; Tong, B.; Li, X.; Zeng, T. Multiscale normalization attention network for water body extraction from remote sensing imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, X.; Xiao, Y. A novel hybrid model based on CNN and multi-scale transformer for extracting water bodies from high resolution remote sensing images. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 10, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Hua, Z. MRSE-Net: Multiscale residuals and SE-attention network for water body segmentation from satellite images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 5049–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambhate, D.; Sharma, R.; Clark, J.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Subramani, D. W-net: A deep network for simultaneous identification of gulf stream and rings from concurrent satellite images of sea surface temperature and height. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambe, R.G.; Talbar, S.N.; Chavan, S.S. Deep multi-feature learning architecture for water body segmentation from satellite images. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2021, 77, 103141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdianpari, M.; Granger, J.E.; Mohammadimanesh, F.; Warren, S.; Puestow, T.; Salehi, B.; Brisco, B. Smart solutions for smart cities: Urban wetland mapping using very-high resolution satellite imagery and airborne LiDAR data in the City of St. John’s, NL, Canada. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qin, Q.; Yésou, H.; Ledauphin, T.; Koehl, M.; Grussenmeyer, P.; Zhu, Z. Monthly estimation of the surface water extent in France at a 10-m resolution using Sentinel-2 data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 244, 111803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benali, A. Water bodies extraction using mathematical morphology. Space Sci. Technol. 2024, 30, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekel, J.F.; Cottam, A.; Gorelick, N.; Belward, A.S. High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 2016, 540, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center, E.R.O.a.S.E. Landsat 8-9 Operational Land Imager/Thermal Infrared Sensor Level-2, Collection 2 [Dataset]; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, D.; Trigg, M.; Ikeshima, D. Development of a global ~90 m water body map using multi-temporal Landsat images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 171, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.