Multi-Scale Quantitative Direction-Relation Matrix for Cardinal Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Direction-Relation Matrix and Its Extended Models

2.2. The Multi-Scale Pyramid Model of Cardinal Directions

3. Multi-Scale Quantitative Model for Cardinal Directions

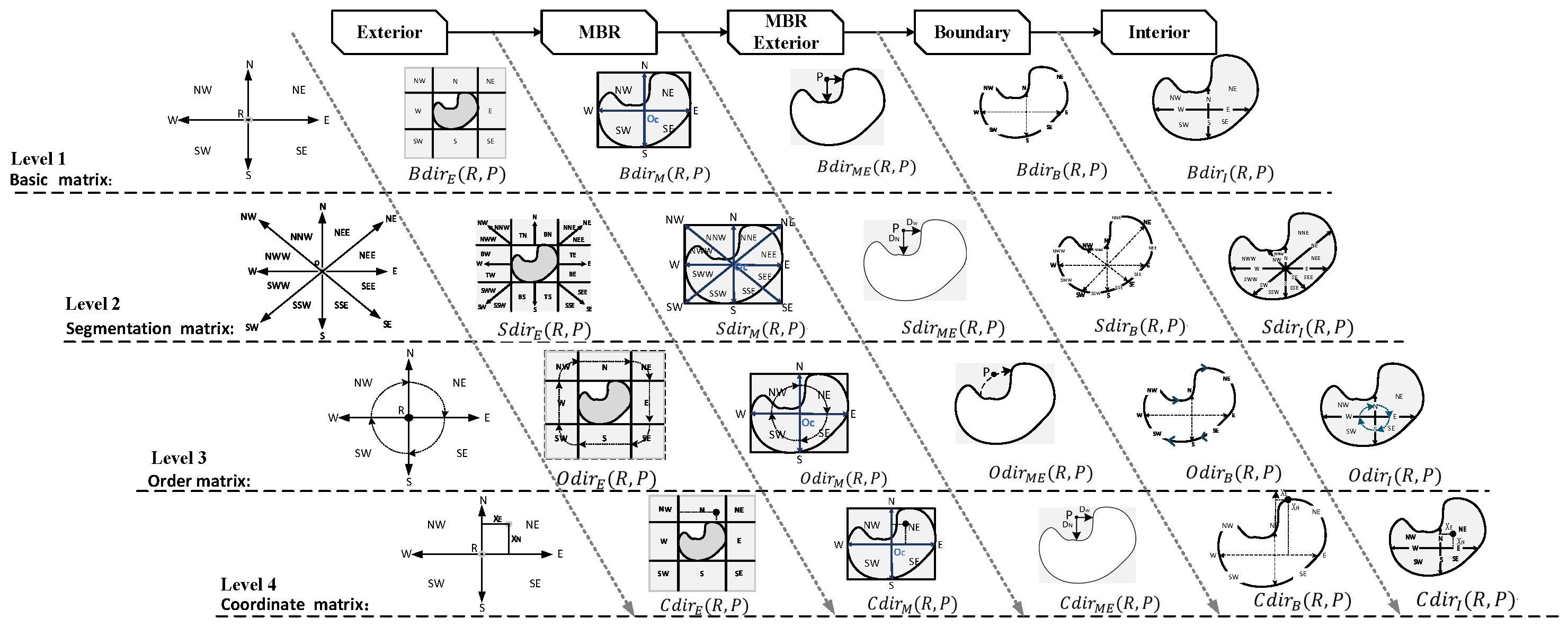

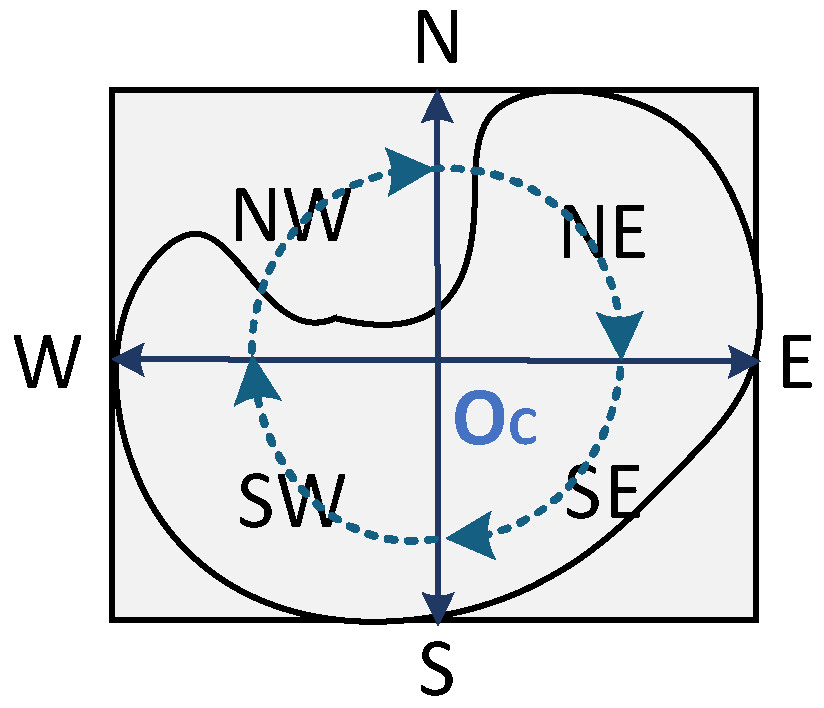

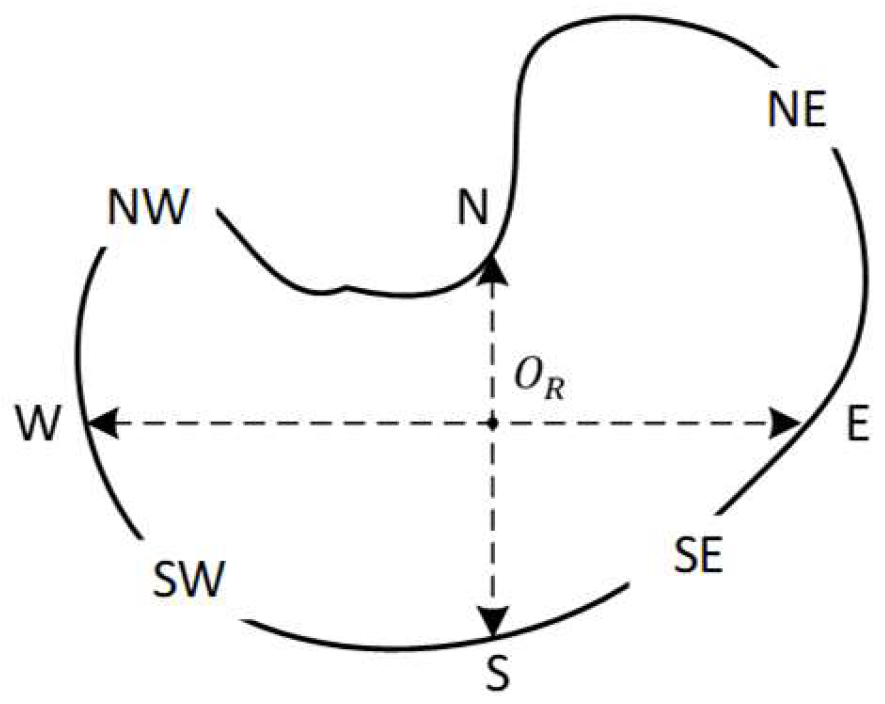

3.1. Framework of MultiScale Quantitative Model for Cardinal Directions

3.2. Direction-Relation Order Matrix

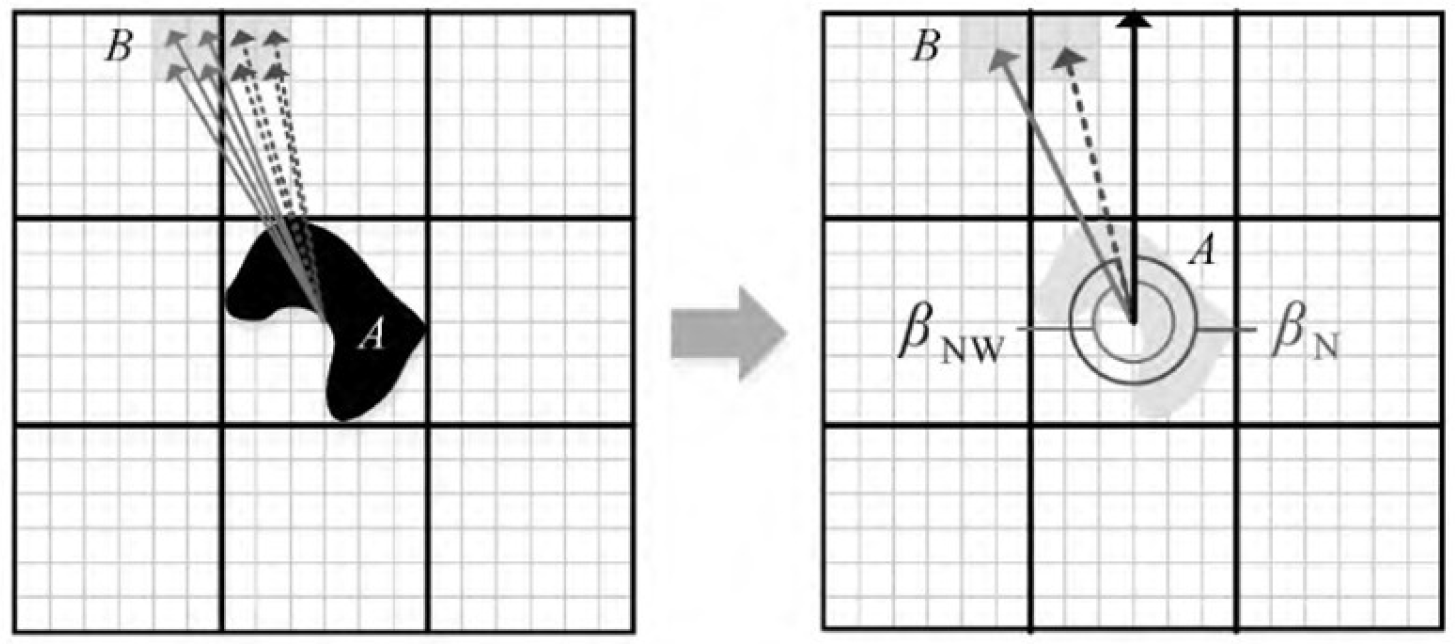

3.2.1. Point as Reference Object

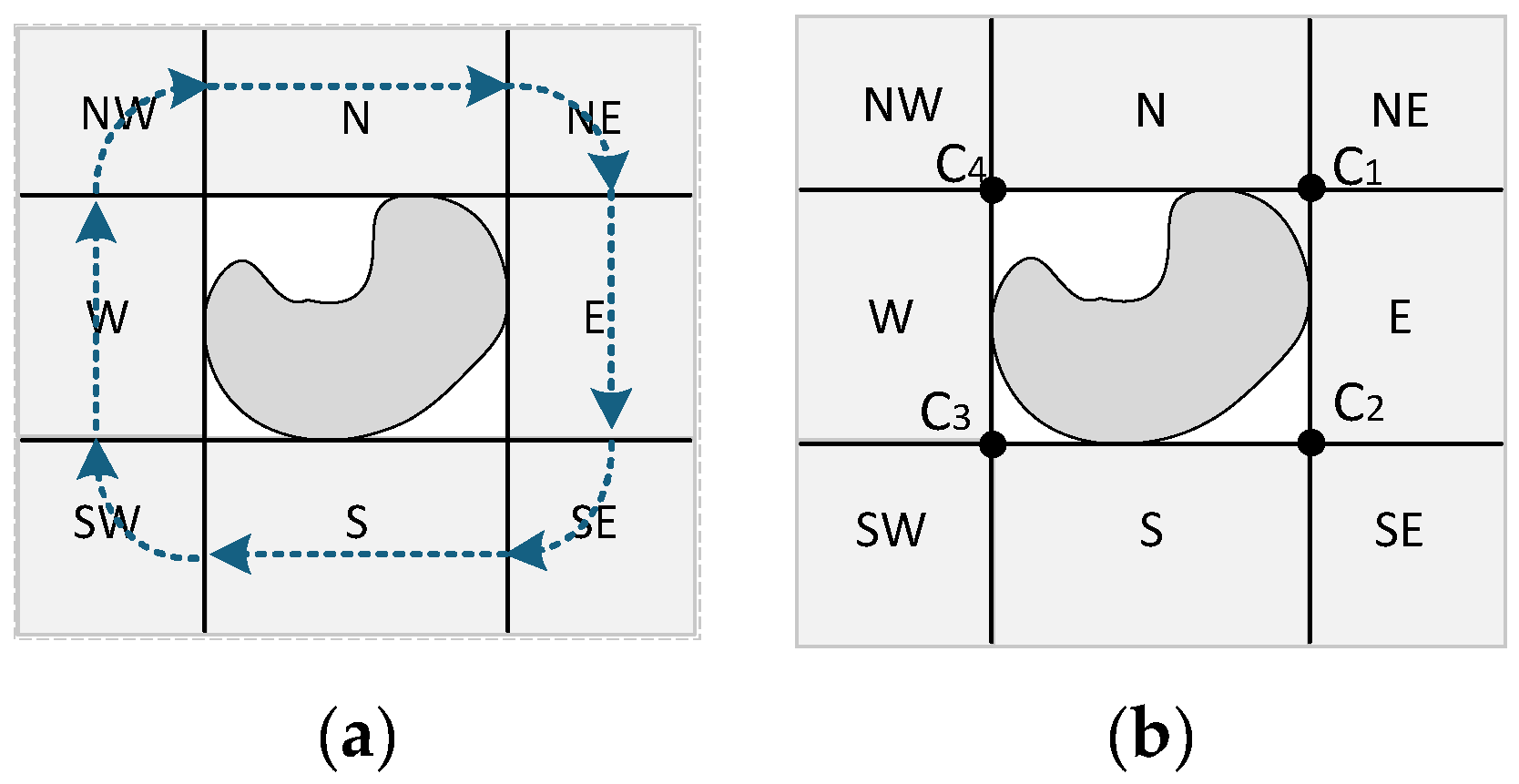

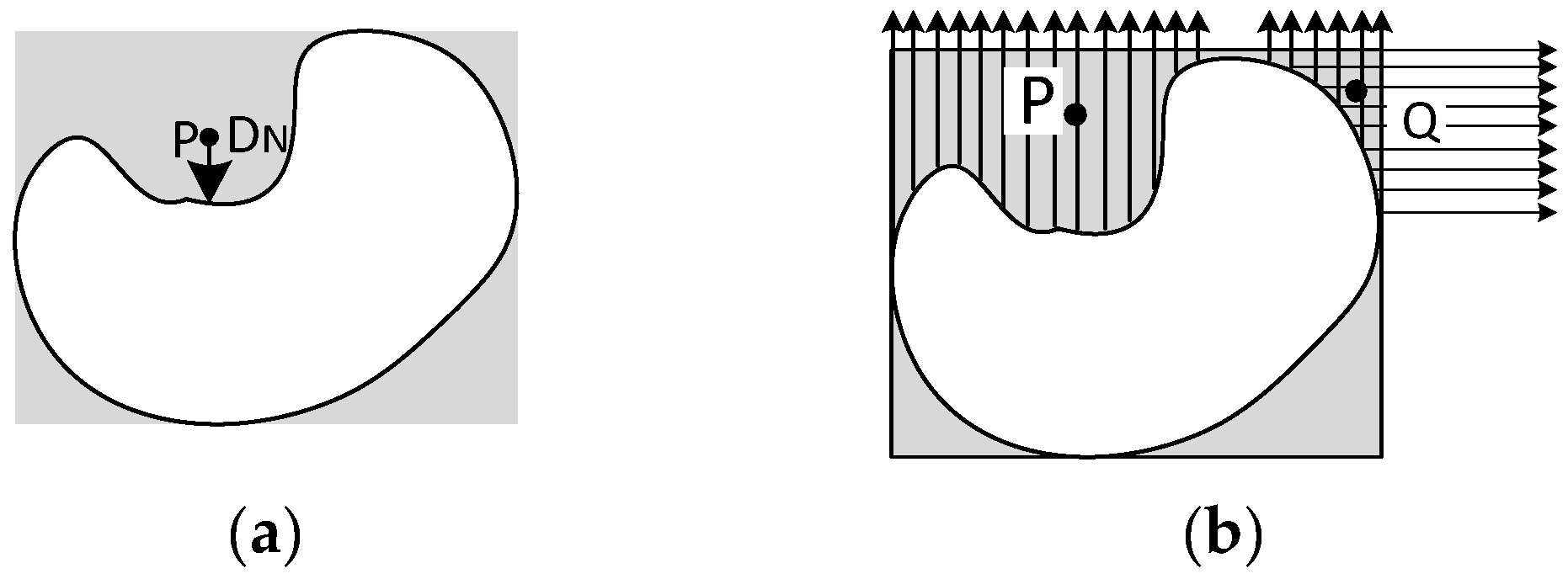

3.2.2. Lines/Polygons as Reference Object

- 1.

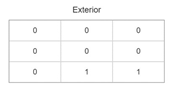

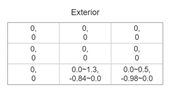

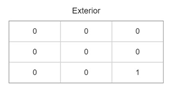

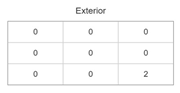

- Exterior region

- 2.

- MBR region

- (1)

- MBR overall order matrix

- (2)

- Local order matrix

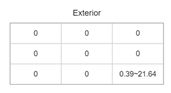

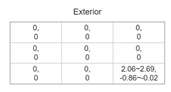

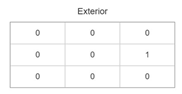

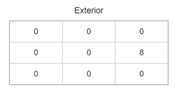

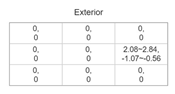

- MBR exterior

- Boundary

- Interior

3.3. Direction-Relation Coordinate Matrix

3.3.1. Point as Reference Object

- where the four parameters , , , and are the numbers of discretized points within several combined directional tiles. Unlike single coordinate sets of cardinal directional tiles, combined directional coordinates incorporate coordinate sets from two cardinal directions.

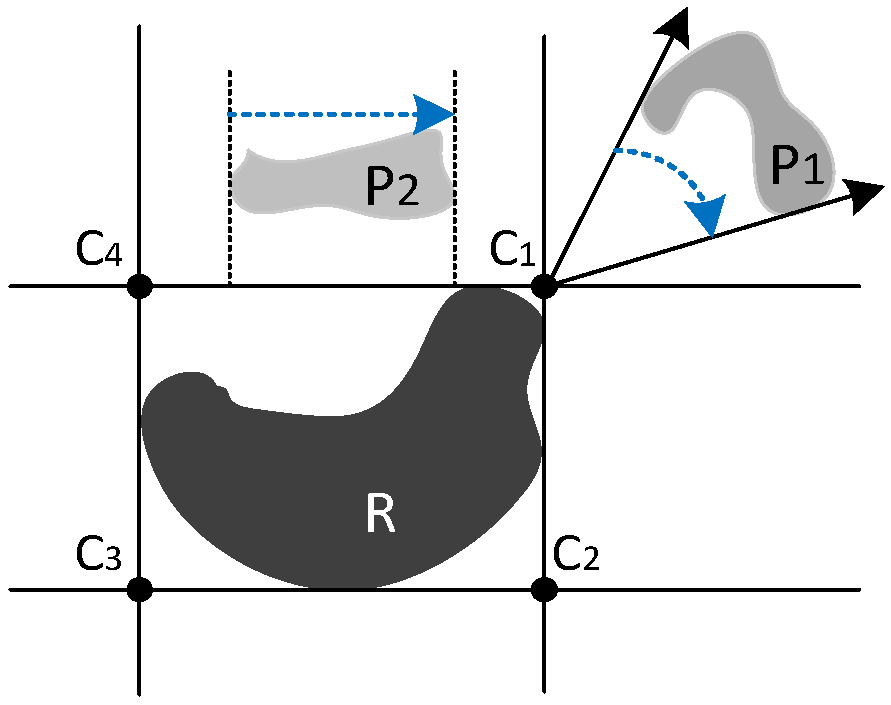

3.3.2. Line/Polygon as Reference Object

- 1.

- Exterior region

- (1)

- The coordinates for the four cardinal direction tiles are:

- (2)

- The coordinates for the four combined direction tiles are:

- 2.

- MBR region

- (1)

- MBR overall coordinate matrix

- (2)

- Local coordinate matrix

3.4. Comparison and Conversion Between Order Matrix and Coordinate Matrix

4. Experimental Evaluations and Results

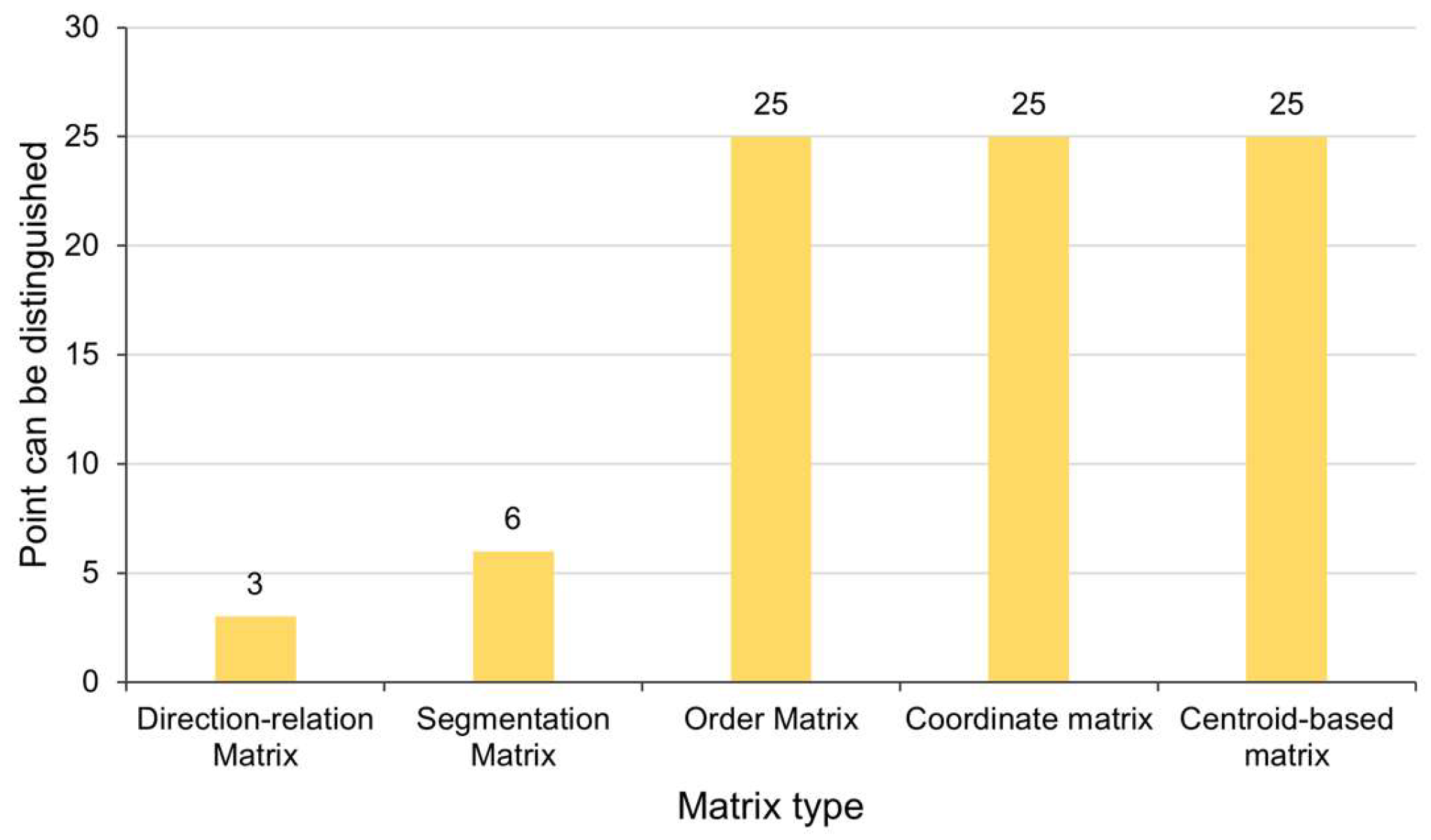

4.1. Expressive Power Analysis and Evaluation of the Accuracy of the Multi-Scale Quantitative Model Description

4.1.1. Rotate the Target Around the Reference Polygon

4.1.2. Moving the Target Across the Reference Polygon

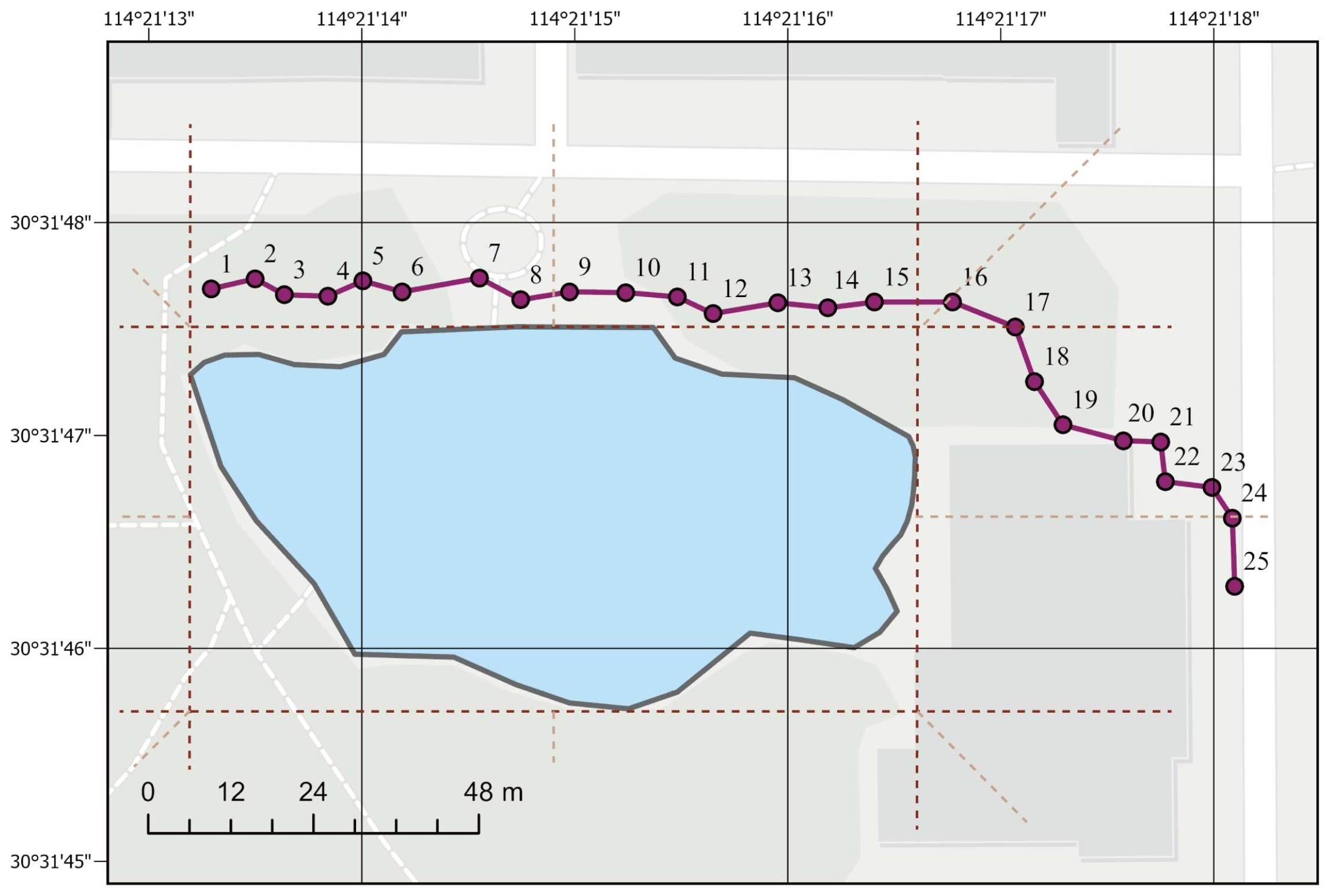

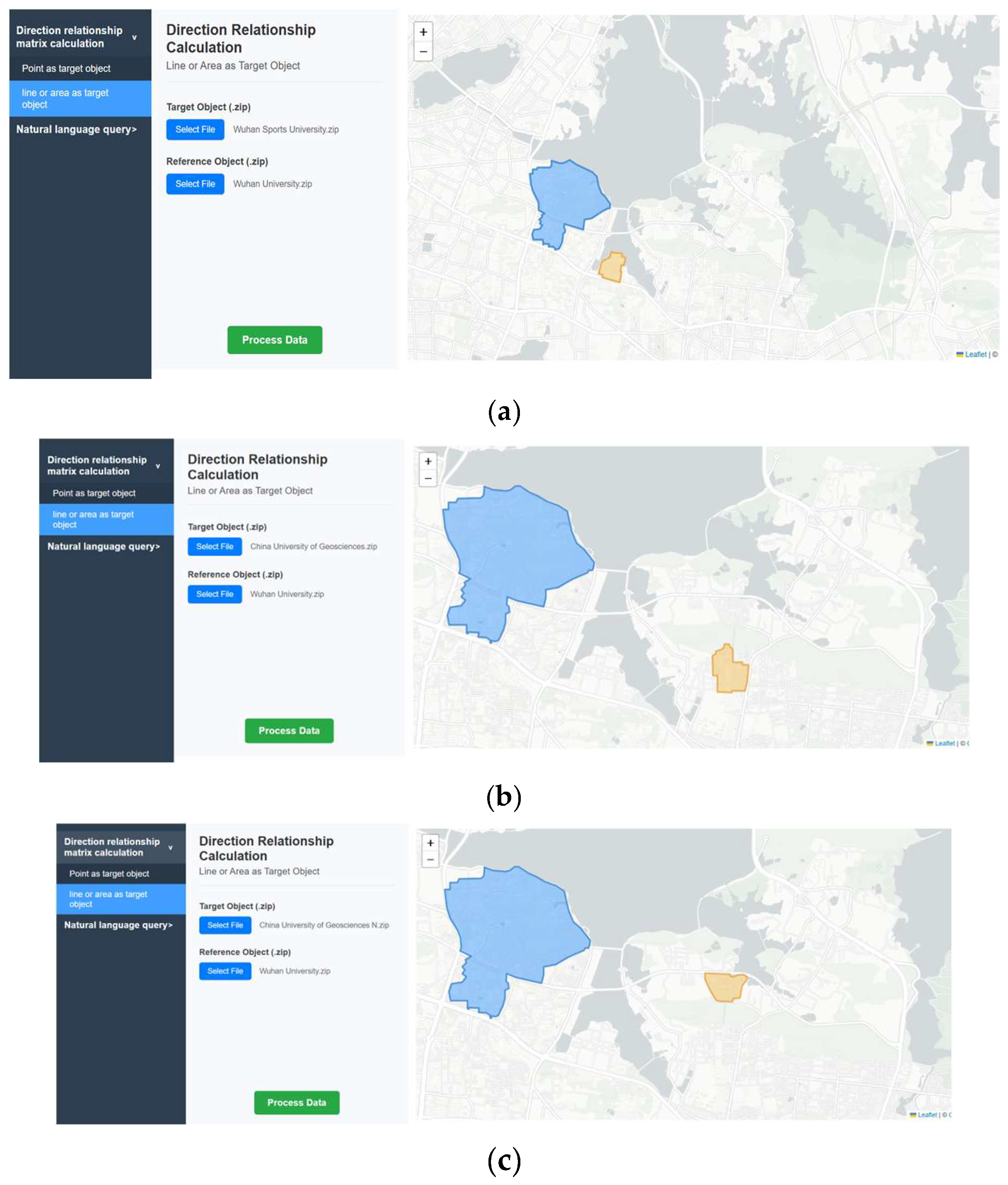

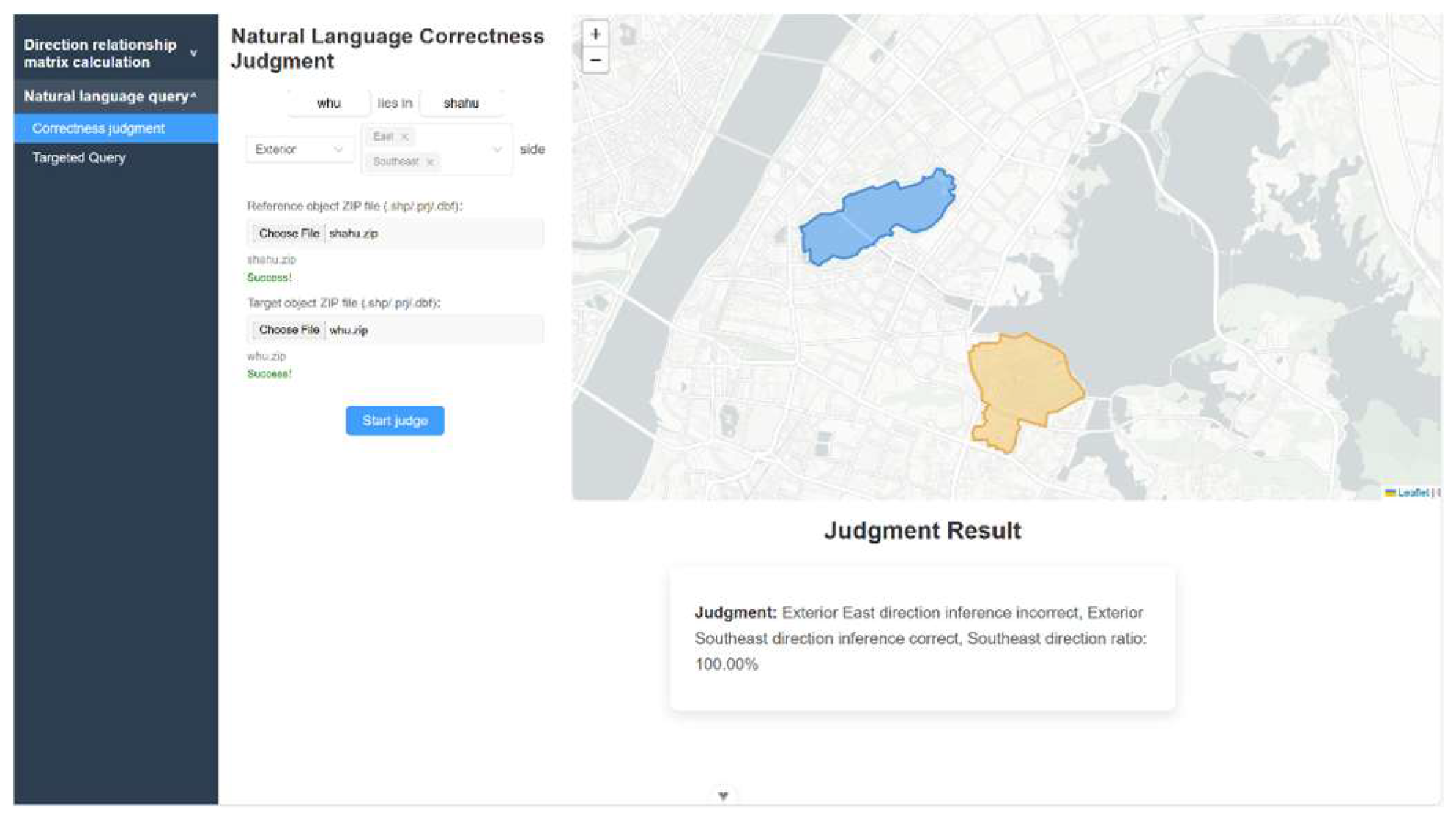

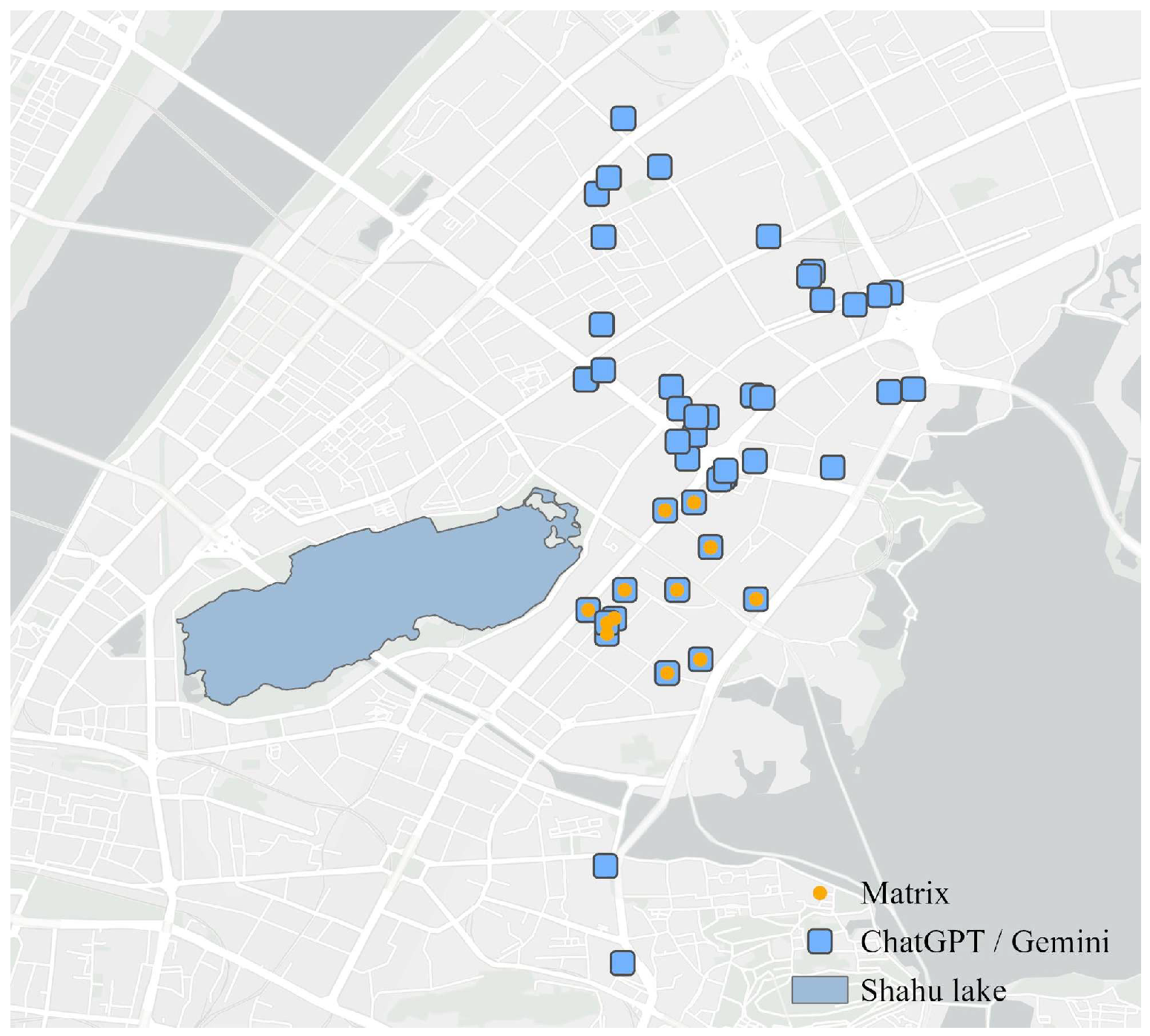

4.2. Application Experiments

5. Conclusions and Discussion

- By integrating both order and coordinate quantitative parameters, the proposed models facilitate the soft classifications of qualitative directional relationships, effectively addressing the limitations of hard classification within the same directional tile. This approach achieves a significantly higher degree of accuracy compared to traditional qualitative description matrices.

- The quantitative models not only enable highly accurate characterization of qualitative directional relationships but also serve as the computational parameters for other qualitative direction-relation matrices, thereby establishing a bridge from precise quantitative coordinate descriptions to qualitative directional semantics.

- By integrating these two quantitative descriptive matrix models with the original multi-scale qualitative direction-relation pyramid model, we build a comprehensive directional relationship pyramid model that spans from quantitative to qualitative analysis, transitioning from precise coordinate-based descriptions to nuanced, fuzzy directional relationship semantics. This establishes a robust framework for the transformation of qualitative directional relationship semantics.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nedas, K.A.; Egenhofer, M.J. Spatial-scene Similarity Queries. Trans. GIS 2008, 12, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, H.T.; Egenhofer, M.J. Similarity of Spatial Scenes. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Spatial Data Handling, Delft, The Netherlands, 12–16 August 1996; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1998; pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, A.U. Qualitative Spatial Reasoning: Cardinal Directions as an Example. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 1996, 10, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.K.; Egenhofer, M.J. Consistent Queries over Cardinal Directions across Different Levels of Detail. In Proceedings of the 11th International Workshop on Database and Expert Systems Applications, 4–8 September 2000; IEEE: London, UK, 2000; pp. 876–880. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Fonseca, F. TDD: A Comprehensive Model for Qualitative Spatial Similarity Assessment. Spat. Cogn. Comput. 2006, 6, 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Janowicz, K.; Mai, G. Making Direction a First-class Citizen of Tobler’s First Law of Geography. Trans. GIS 2019, 23, 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.K.; Egenhofer, M.J. Similarity of Cardinal Directions. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 2121, pp. 36–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Guo, R. A Formal Description Model of Directional Relationships Based on Voronoi Diagram. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2003, 28, 468–471. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y. A Qualitative Description Model of Detailed Direction Relations. J. Image Graph. 2004, 12, 1496–1503. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, L.; He, Z. A Two-Tuple Model Based Spatial Direction Similarity Measurement Method. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2021, 50, 1705–1716. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, R.K. Similarity Assessment for Cardinal Directions Between Extended Spatial Objects. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Maine, Orono, ME, USA, 2000; pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Ouyang, J.; Huo, L.; Li, S. Similarity of Direction Relations in Spatial Scenes. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2012, 8, 8589–8596. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, L.; Gong, X.; Wu, L. A Quantitative Calculation Method of Spatial Direction Similarity Based on Direction Relation Matrix. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2015, 44, 813. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Liu, J.; Yan, H.; Lu, X. An Improved Model for Calculating the Similarity of Spatial Direction Based on Direction Relation Matrix. J. Geomat. Sci. Technol. 2018, 35, 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H. Theoretical system and potential research issues of spatial similarity relations. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2023, 52, 1962–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Egenhofer, M.J. Query processing in spatial-query-by sketch. J. Vis. Lang. Comput. 1997, 8, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ai, T.; Stoter, J.; Zhao, X. Data Matching of Building Polygons at Multiple Map Scales Improved by Contextual Information and Relation. Isprs J. Photogramm. 2024, 92, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xie, Z.; Wu, L. Spatial Scene Matching Based on Multiple level Relevance Feedback. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2018, 43, 1422–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Shao, Q.; Deng, M.; Mei, X.; Hou, J. High-Resolution Remote Sensing Image Retrieval via Land-Feature Spatial Relation Matching. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 20, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dai, X.; Zhou, X.; Sun, G.; Deng, M. Semantic Understanding of Geo-Objects’ Relationship in High Resolution Remote Sensing Image Driven by Dual LSTM. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2021, 25, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Nong, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X. Spatial Relation Ship Detection Method of Remote Sensing Objects. Acta Opt. Sin. 2021, 41, 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Li, S. Reasoning about Cardinal Directions between Extended Objects: The NP-Hardness Result. Artif. Intell. 2011, 175, 2155–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liang, F.; Sun, Y. Integrating Spatial Relations into Case-Based Reasoning to Solve Geographic Problems. Knowl. Based Syst. 2012, 33, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Li, J.; Qu, S. A Qualitative Reasoning Method for Cardinal Directional Relations under Concave Landmark Referencing. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2018, 43, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Hao, Z. Reasoning with the Original Relations of the Basic 2D Rectangular Cardinal Direction Relation. J. Xi’An Jiaotong Univ. 2020, 54, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, H.; Zhang, P. Question-Guided Spatial Relation Graph Reasoning Model for Visual Question Answering. J. Image Graph. 2022, 27, 2274–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Formalizing Natural-language Spatial Relations between Linear Objects with Topological and Metric Properties. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2007, 21, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H. Quantitative Relations between Spatial Similarity Degree and Map Scale Change of Individual Linear Objects in Multi-Scale Map Spaces. Geocarto Int. 2015, 30, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasardani, M.; Winter, S.; Richter, K. Locating Place Names from Place Descriptions. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 27, 2509–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Liu, P.; Jin, C.; Xu, D.; Wang, F. A Hand-drawn Map Retrieval Method Based on Open Area Spatial Direction Relation. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2017, 46, 1899–1909. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; Gao, S.; Nie, Y.; Majić, I.; Janowicz, K. Foundation Models for Geospatial Reasoning: Assessing the Capabilities of Large Language Models in Understanding Geometries and Topological Spatial Relations. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. IJGIS 2025, 39, 1866–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, W.; Chiang, Y.Y.; Chen, M. Geolm: Empowering Language Models for Geospatially Grounded Language Understanding. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.14478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.C.; Yin, H.; Fu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Yang, R.; Kautz, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, S. Spatialrgpt: Grounded Spatial Reasoning in Vision-Language Models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 135062–135093. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, M.; Li, Z. A Statistical Model for Directional Relations between Spatial Objects. Geoinformatica 2008, 12, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemura, C.M.; Cesar, R.M., Jr.; Bloch, I. Modeling and Measuring the Spatial Relation “along”: Regions, Contours and Fuzzy Sets. Pattern Recognit. 2012, 45, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Chen, J.; Du, D. Qualitative Extension Description for Cardinal Directions of Spatial Objects. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2001, 30, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Haar, R. Computational Models of Spatial Relations; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Peuquet, D.; Zhang, C. An Algorithm to Determine the Directional Relationship between Arbitrarily-Shaped Polygons in the Plane. Pattern Recognit. 1987, 20, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadias, D.; Theodoridis, Y. Spatial Relations, Minimum Bounding Rectangles, and Spatial Data Structures. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 1997, 11, 111–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Qin, K.; Meng, L. A Qualitative Matrix Model of Direction-Relation Based on Topological Reference. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2014, 43, 396–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kulik, L.; Klippel, A. Reasoning about Cardinal Directions Using Grids as Qualitative Geographic Coordinates. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 1661, pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Kwan, M.; Yu, Y.; Xie, L.; Qin, K.; Zhang, T. A Multiscale Pyramid Model of Cardinal Directions for Different Scenarios. Trans. GIS 2025, 29, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Meng, L.; Qin, K. A Coordinate-Based Quantitative Directional Relations Model. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design, Piscataway, NJ, USA, 12–14 December 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 483–488. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Ai, T. Automatic Extraction of Skeleton and Center of Area Feature. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2004, 29, 443–446. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Ai, T. Center Point Extraction of Simple Area Object Using Triangulation Skeleton Graph. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2020, 45, 337–343. [Google Scholar]

| Scene | Direction-Relation Matrix | Segmentation Matrix | Order Matrix | Coordinate Matrix | Centroid-Based Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scene 1 | |||||

| Scene 2 | |||||

| Scene 3 | |||||

| Scene 4 | |||||

| Scene 5 | |||||

| Scene 6 | |||||

| Scene 7 | |||||

| Scene 8 | |||||

| Scene 9 | |||||

| Scene 10 | |||||

| Scene 11 | |||||

| Scene 12 | |||||

| Scene 13 | |||||

| Scene 14 | |||||

| Scene 15 | |||||

| Scene 16 | |||||

| Scene 17 | |||||

| Scene 18 | |||||

| Scene 19 | |||||

| Scene 20 | |||||

| Scene 21 | |||||

| Scene 22 | |||||

| Scene 23 | |||||

| Scene 24 | |||||

| Scene 25 |

| Point | Order Matrix | Coordinate Matrix | Centroid-Based Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | |||

| P2 | |||

| P3 | |||

| P4 | |||

| P5 | |||

| P6 | |||

| P7 | |||

| P8 | |||

| P9 | |||

| P10 | |||

| P11 | |||

| P12 |

| Scene | Basic Matrix | Segmentation Matrix | Order Matrix | Coordinate Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |  |  |  |

| 2 |  |  |  |  |

| 3 |  |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tang, X.; Kwan, M.-P.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Xie, L.; Qin, K.; Lu, B. Multi-Scale Quantitative Direction-Relation Matrix for Cardinal Directions. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2026, 15, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010011

Tang X, Kwan M-P, Zhang Y, Yu Y, Xie L, Qin K, Lu B. Multi-Scale Quantitative Direction-Relation Matrix for Cardinal Directions. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2026; 15(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Xuehua, Mei-Po Kwan, Yong Zhang, Yang Yu, Linxuan Xie, Kun Qin, and Binbin Lu. 2026. "Multi-Scale Quantitative Direction-Relation Matrix for Cardinal Directions" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 15, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010011

APA StyleTang, X., Kwan, M.-P., Zhang, Y., Yu, Y., Xie, L., Qin, K., & Lu, B. (2026). Multi-Scale Quantitative Direction-Relation Matrix for Cardinal Directions. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 15(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010011