Abstract

Achieving reliable and real-time inverse kinematics (IK) for 6-degree-of-freedom (6-DoF) spherical-wrist manipulators remains a significant challenge. Analytical formulations often struggle with complex geometries and modeling errors, and standard numerical solvers (e.g., Levenberg–Marquardt) can stall near singularities or converge slowly. Purely data-driven approaches may require large networks and struggle with extrapolation. In this paper, we propose a low-latency, polynomial-based IK solution for spherical-wrist robots. The method leverages spherical coordinates and low-degree polynomial fits for the first three (positional) joints, coupled with a closed-form analytical solver for the final three (wrist) joints. An iterative partial-derivative refinement adjusts the polynomial-based angle estimates using spherical-coordinate errors, ensuring near-zero final error without requiring a full Jacobian matrix. The method systematically enumerates up to eight valid IK solutions per target pose. Our experiments against Levenberg–Marquardt, damped least-squares, and an fmincon baseline show an approximate 8.1× speedup over fmincon while retaining higher accuracy and multi-branch coverage. Future extensions include enhancing robustness through uncertainty propagation, adapting the approach to non-spherical wrists, and developing criteria-based automatic solution-branch selection.

1. Introduction

Inverse kinematics (IK) for 6-DoF robotic manipulators remains challenging. Analytical methods struggle with modeling errors and uncertainties, often requiring extensive calibration for real-world deployment. Numerical solvers depend heavily on initial joint-angle guesses and may fail to converge within practical time limits, especially near singularities. Meanwhile, purely data-driven neural networks demand large training datasets and exhibit poor generalization outside their sampled workspace.

We detail a hybrid polynomial–analytical IK method tailored for 6-DoF robots with a spherical wrist. We approximate the first three joints (positional subsystem) using polynomial fits in spherical coordinates, then solve the final wrist orientation through a closed-form technique. A short iterative process using partial-derivative evaluations from the polynomial fits refines each candidate solution to high accuracy. The algorithm updates each angle component-wise, avoiding the need for a full Jacobian-based method, and discards out-of-limit or divergent solutions. The approach systematically enumerates up to eight valid solutions, giving flexibility in workspace planning. Empirical results show superior speed, accuracy, and multi-solution coverage compared to a Levenberg–Marquardt baseline.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Classical IK Methods

Classical inverse kinematics is split between analytic closed-form solutions and iterative numerical schemes. While efficient, analytical methods typically require specialized manipulator geometry and can become infeasible with additional offsets or unusual link arrangements [1,2]. Numerical approaches such as Jacobian transpose/inverse or Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) are widely applicable but may struggle near singularities due to ill-conditioned equations [3,4,5], prompting refinements such as stabilized variants [6].

2.2. Computational Intelligence Methods

Data-driven approaches, including neural networks and fuzzy systems, address IK’s inherent nonlinearity by learning pose-to-joint mappings [7,8,9,10]. However, large datasets and memory footprints are often required to cover the manipulator’s entire workspace [11,12,13]. Extrapolation beyond the training domain remains a challenge, which can be especially problematic near singularities or mechanical limits.

2.3. Enhanced Numerical and Iterative Techniques

Refinements to classical solvers like the Crank-Nicolson approach [3] or advanced Jacobian-based formulations [5] improve stability and convergence speed; still, repeated matrix inversions can become computationally heavy for real-time tasks, and local minima or singular points can disrupt performance if no robust fallback is present [6].

2.4. Optimization and Meta-Heuristic Methods

Global search approaches such as firefly, particle swarm, or evolutionary algorithms attempt to mitigate local minima issues [14,15]. They can find solutions under complex constraints but often require significant compute time, making them less appealing for high-frequency control loops.

2.5. Hybrid Approaches for Complex IK

Research into hybrid methods combining partial geometric insights with optimization or data-driven techniques highlights possible synergy. Jin et al. [16] fused swarm optimization with partial analytics to handle singularities, while Rathnam et al. [17,18] used neural networks integrated with analytical solvers to reduce training overhead in 3D tasks. These strategies motivate our work, which pairs polynomial fittings for the first three joints with a direct wrist solver. Unlike regression-only IK mappers, the proposed approach retains analytical structure in the wrist and uses low-degree polynomials only where the kinematic decoupling is strongest, thereby reducing model size and improving extrapolation. Compared with prior hybrid schemes that still rely on global Jacobians or heavy numerical back-ends, our refinement is component-wise and avoids matrix inversions, trading a small offline fit for lighter online computation.

2.6. Task-Specific IK and Spherical Wrists

Many industrial arms adopt a spherical wrist layout, enabling simpler closed-form orientation solvers [1]. Additional specialized solutions target hardware constraints such as FPGA-based IK [19] or anchor-point modeling [20], or alternatively target specific tasks such as generative visual servoing [12]. Our approach extends this niche by providing a polynomial-based solution for the arm portion while relying on the well-understood wrist geometry.

3. Problem Statement

A robust, fast, and memory-efficient IK framework is critical for real-time 6-DoF manipulation. Classical analytical methods often fail when offsets or redundancies exist, while purely numerical solvers risk slow or non-convergent behavior near singularities. Data-driven neural networks add flexibility but can require large memory footprints and may degrade when extrapolating beyond their training domain.

Our goal is to develop an IK method that:

- Runs in Real-Time: Achieves millisecond-level solve times.

- Handles Singularity Neighborhoods: Avoids indefinite iteration or instability in kinematically challenging poses.

- Enumerates Multiple Solutions: Accounts for elbow-up/down and wrist flips, yielding up to eight distinct IK branches.

Hence, we propose a hybrid polynomial–analytical solution: the first three positional joints are solved using computationally efficient polynomial fitting on lower-dimensional spherical manifolds, whereas the wrist joints are resolved analytically. The solution is further refined using partial derivative-based iteration to ensure kinematic consistency and precision.

4. Proposed Methodology

This section outlines our hybrid polynomial–analytical inverse kinematics (IK) method, showing how four distinct polynomials address the first three (arm) joints . We further explain the iterative refinement strategy, which applies partial-derivative corrections for final precision. Joints 4–6 (the spherical wrist) are solved through a standard closed-form process.

4.1. Offline Phase: Data Collection and Polynomial Fitting

The offline phase systematically collects and prepares data to create four polynomial models, capturing the relationship between the first three joint angles and the end-effector spherical coordinates (azimuth, elevation, and radial distance). The collected data ensure accurate polynomial fits, enabling multiple valid solutions during the subsequent online inverse kinematics phase.

Rationale for Targeted Sweeps in Reduced Manifolds

By decomposing the workspace into lower-dimensional manifolds (azimuth, elevation, radial distance) and conducting targeted sweeps rather than a brute-force 3D grid search, we achieve the following:

- Data efficiency:

- –

- Fewer samples required ( vs )

- –

- Higher resolution per parameter with sparse sampling

- Improved joint-to-workspace mapping, resulting in:

- –

- Noise reduction through decoupled 1D/2D polynomial fits

- –

- Explicit coverage of elbow-up/down configurations

- Manifold-aware sampling:

- –

- Natural alignment with spherical kinematics

- –

- Built-in singularity detection via

Outcome. This approach yields a compact dataset that enables:

- Numerically stable polynomial inversion during online IK

- Multiple valid solutions with guaranteed physical feasibility

- Real-time performance through reduced computational complexity

Observation. For a robot with n joints, the minimum required samples scale as per manifold rather than for grid sampling, while still spanning the solution space through

under the assumption that the positional subspace decouples as in (2). The refinement process in the online stage then converges to the same solutions as grid-based initialization for the sampled workspace.

Algorithm 1 summarizes the offline data collection and polynomial fitting procedure.

| Algorithm 1 Data Collection and Polynomial Fitting |

|

Algorithm 2 summarizes the online inverse kinematics procedure (polynomial root finding, partial-derivative refinement, and solution filtering).

| Algorithm 2 6-DoF Spherical-Wrist IK with Four Polynomials, Partial-Derivative Refinement, and Multi-Solution Handling |

|

4.2. Mathematical Validity of Reduced Sampling

4.2.1. Chain Rule in Spherical Coordinates

The decomposition is valid because spherical coordinates naturally separate the kinematic relationships:

This triangular structure emerges because:

- Azimuth () depends only on the base rotation .

- Elevation () depends primarily on the shoulder joint for the spherical wrist considered here; coupling terms are negligible in the sampled workspace.

- Radius (r) depends on the planar arm configuration ().

4.2.2. Block-Diagonal Jacobian Structure

The Jacobian matrix in -space has the following block-diagonal form:

For a spherical wrist, the orientation subspace decouples from the first three joints, justifying this block-diagonal layout. This structure guarantees that:

- Joint corrections can be computed independently per subspace

- Null spaces do not interact across different joints

4.2.3. Completeness of Spherical Basis Functions

The spherical-coordinate basis vectors form a complete basis for :

With and , the basis vectors are:

- Azimuthal basis:

- Elevation basis:

- Radial basis:

This ensures all reachable workspace points can be expressed through the reduced coordinates.

Conclusions: The reduced sampling is mathematically equivalent to 3D grid sampling because:

- The chain rule justifies independent parameter sweeps.

- The Jacobian structure permits separate error correction.

- The spherical basis guarantees complete workspace coverage.

4.3. Online Phase: Polynomial Inversion + Partial-Derivative Refinement + Wrist Solutions

- Partial-Derivative Refinement.

During the online loop, a global Jacobian is neither formed nor inverted. Instead, each joint angle is updated based on spherical-coordinate errors. For instance, uses the azimuth error and incorporate partial derivatives to correct the radial dimension. If any derivative is near zero, the code omits or clamps that update to avoid numerical instability.

- Overall Flow.

Offline: (1) sample on the spherical manifolds; (2) fit low-order polynomials ; (3) store coefficients and partial derivatives. Online: (1) convert the target pose to spherical coordinates; (2) solve the four polynomials for the arm roots; (3) refine each arm root with the per-joint partial-derivative updates (clamping/skipping near singularities); (4) solve the wrist in closed form; (5) filter joint limits, validate via forward kinematics, and return up to eight solutions. This flow keeps the online loop lightweight and hardware-friendly.

4.4. Final Multi-Solution Output

If multiple real roots exist for , the solver can produce up to four valid arm configurations; coupled with two wrist solutions, up to eight full 6-DoF solutions may emerge. Any out-of-range angles or nonconvergent results are discarded, leaving the final set of valid solutions. In many typical poses, fewer than eight survive; still, the framework is designed to systematically account for all potential branches.

5. Results and Performance Analysis

To evaluate the performance of the proposed inverse kinematics (IK) method, a comprehensive comparison was conducted against a standard numerical optimization-based IK solver. This section details the experimental setup for the benchmark and presents a detailed analysis of the results.

5.1. Benchmark: Optimization-Based IK Solver Setup

The benchmark solver was designed to find the optimal joint configuration for the 6-DOF KUKA Rhino manipulator. The optimization problem is formulated to find the joint configuration that minimizes a weighted sum of the squared position and orientation errors. Given a desired end-effector pose and the robot’s forward kinematics map , the objective function is defined as

where is the squared Euclidean distance for position and is the angular error in radians, calculated as the angle of the relative rotation matrix . As such, the target pose contains the desired rotation and position . The weighting factors and balance the contribution of the position and orientation components. This minimization is subject to box constraints defined by the KUKA Rhino’s joint limits () and a nonlinear inequality constraint to ensure solution smoothness by limiting the maximum joint displacement between consecutive configurations to 0.2 radians (). The problem was solved using MATLAB’s fmincon function with a sequential quadratic programming (SQP) algorithm configured with an optimality tolerance of and a constraint tolerance of . A multi-start strategy was employed, initiating five searches per trajectory point: one warm start from the previous solution and four from random configurations. All computations were performed on a workstation equipped with an AMD Ryzen 5 7000 series processor (six cores, twelve threads, up to 4.5 GHz) and 16 GB of DDR5 RAM while running MATLAB R2023b.

5.2. Trajectory Tracking Performance

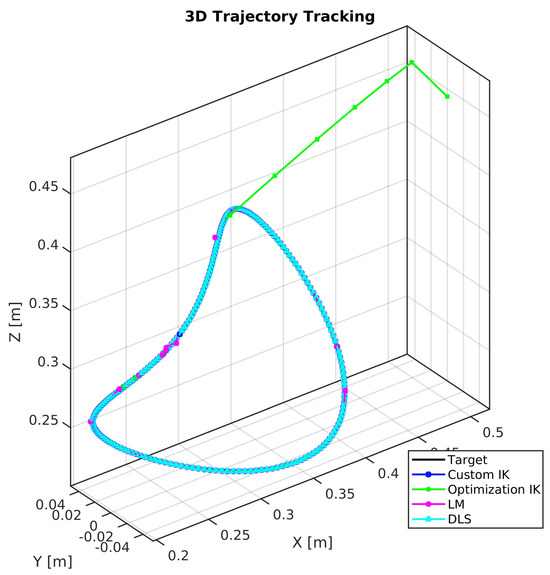

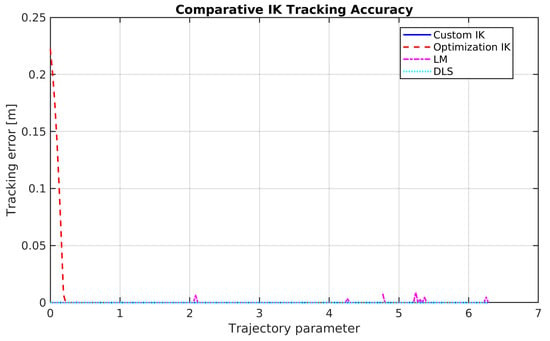

The proposed custom IK method demonstrated exceptional precision, achieving a mean and maximum tracking error of effectively zero (<10−6 m) across all 200 trajectory points, as illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2. In contrast, the optimization-based solver, while maintaining a low median error of m, exhibited significant spikes, with a maximum deviation of 0.2223 m whenever it fell into a local minimum. The LM baseline achieved very small medians ( m) but occasionally diverged to 2.62 m near singularities; the DLS baseline was stable and low-error (max m) but returned only a single branch. These observations highlight the superior accuracy and reliability of the proposed solver across the workspace.

Figure 1.

Three—dimensional visualization of the target trajectory versus paths achieved by all IK solvers (Custom, fmincon, LM, DLS).

Figure 2.

Comparative IK tracking accuracy over the trajectory (custom, fmincon, LM, DLS).

5.3. Computational Efficiency

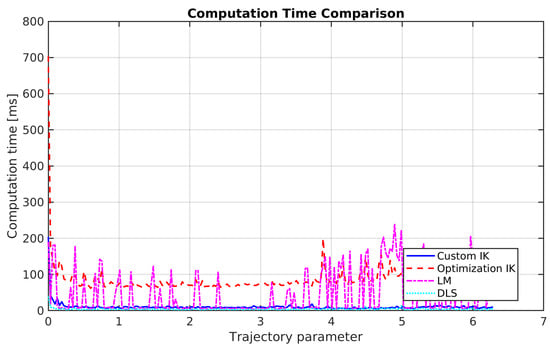

As shown in Figure 3, the proposed custom IK was substantially more efficient. It recorded a mean computation time of 10.48 ms per point (median 9.01 ms; 95th 14.07 ms). The optimization-based solver averaged 85.32 ms per point (median 77.01 ms; 95th 125.09 ms). DLS was the fastest (median 3.49 ms; 95th 7.07 ms), but is single-branch; LM showed wide timing dispersion (median 7.90 ms; 95th 172.49 ms) and intermittent large errors. The custom method remains the best balance of speed, accuracy, and multi-branch coverage.

Figure 3.

Computation time comparison of custom, fmincon, LM, and DLS.

5.4. Complexity and Baseline Context

The offline stage fits low-order polynomials (degree 3–4) per joint manifold. Online, each candidate arm solution is refined with a small and fixed number of iterations (typically <10) using only per-joint partial derivatives and no matrix inversions, meaning that runtime scales linearly with the number of candidate branches. We also tested Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) and a simple damped least-squares (DLS) baseline; LM remained sensitive near singularities (wide error and time dispersion), while DLS was fast but returns only a single branch and has higher residuals than the custom solver. A closed-form solver for this arm exists and aligns with our wrist solution; for completeness, it is discussed as a future comparative baseline.

5.5. Error Variability and Singularities

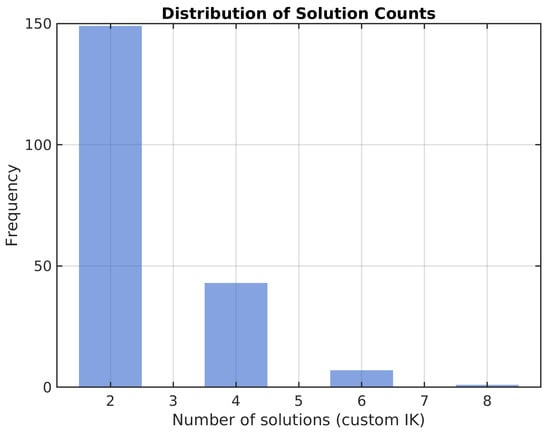

Across the 200-point trajectory, the positional error distribution for the custom IK had a standard deviation below m, with a maximum error below m; the optimization baseline showed a standard deviation on the order of m, consistent with the 0.2223 m spikes. The refinement loop omits or clamps updates when , preventing numerical blow-up near singularities; near such poses, the method may return fewer valid branches (reflected in Figure 4) but retains finite errors.

Figure 4.

Distribution of solution counts for the custom inverse kinematics solver.

5.6. Joint Space Behavior and Continuity

An examination of the joint-space paths reveals notable differences in smoothness and continuity. The custom IK produced smooth and continuous joint trajectories, characteristic of a solution that implicitly minimizes joint velocities. The optimization-based solver’s trajectories were less smooth and had occasional oscillations, suggesting solutions that, while locally optimal for the pose, may be suboptimal in terms of joint-space smoothness.

5.7. Custom IK Solver Characteristics

As depicted in Figure 4, the proposed IK solver consistently identified a small number of distinct inverse kinematics solutions for each evaluated point. With a mean solution count of 2.6, this finding suggests a robust and well-defined analytical process, yielding a predictable and manageable set of kinematic configurations for a given end-effector pose.

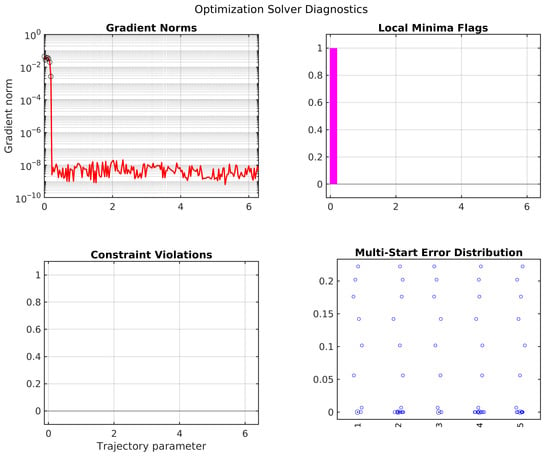

5.8. Optimization Solver Diagnostics and Solution Quality

Analysis of the optimization solver’s diagnostics (Figure 5) provides key insights into its behavior. The solver successfully found a solution for all 200 points. While gradient norms were generally low, indicating convergence, the solver converged to a suboptimal local minimum (i.e., a solution with higher tracking error than the custom IK’s) in 3.5% of cases (7 out of 200). In these same instances, the solver failed to meet the optimality tolerance, indicated by high final gradient norms. Encouragingly, no constraint violations were observed, demonstrating the solver’s effectiveness at adhering to joint limits.

Figure 5.

Optimization solver diagnostics: solution quality, local minima, constraint adherence, and multi-start results.

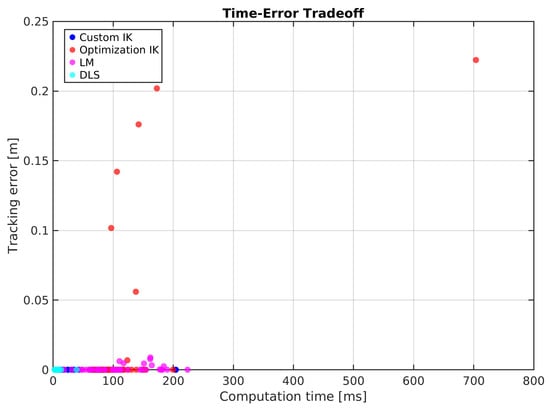

5.9. Time–Error Tradeoff

The time-=error tradeoff plot in Figure 6 provides a clear summary of the performance comparison. The custom IK occupies the ideal region of the plot, consistently delivering high accuracy (low error) at very low computational cost. The optimization-based solver’s results are scattered, showing both higher computation times and wide variance in the tracking error. For LM, the points are concentrated near low error, but include several high-error and high-time outliers. DLS clusters at low time and modest error, but only yields one branch. Overall, the custom method remains the best choice for this application.

Figure 6.

Time—error tradeoff: performance comparison of custom, fmincon, LM, and DLS.

5.10. Summary of Performance Metrics

Clarifications. Custom positional errors are bounded by the solver tolerance ( m); the mean/median/percentile values reported come from forward-kinematics validation over 200 points (max m). “Mean solutions/point” counts distinct feasible IK branches per pose after removing out-of-limit or duplicate configurations. “Validated solutions” denotes the fraction of targets producing a feasible branch that passes the final FK check (200/200 for all methods; LM statistics exclude candidate solves with > m residual before validation). Timings measure solver runtime only (no plotting or I/O) and use a warm-started optimizer (previous solution plus four random initializations) on the AMD Ryzen 5/16 GB workstation noted above; MATLAB’s default PRNG was used without a fixed seed. Optimization median errors are very small but exhibit rare spikes to 0.2223 m, captured by the max entry. Levenberg–Marquardt (RVC ikine) remains sensitive near singularities (max error 2.62 m despite low median), while a simple damped least-squares baseline converged quickly (median 3.49 ms) but with higher residuals than the custom solver while returning only one branch. Local-minima flags for fmincon, LM, and DLS indicate cases in which the final residual exceeded the custom solution; constraint checks were instrumented for fmincon and replayed on the returned LM/DLS trajectories without detecting limit violations.

The overall performance metrics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of performance metrics for the 200-point trajectory.

6. Discussion

The results demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed custom IK solver over the generalized optimization-based approach for the KUKA Rhino manipulator. The custom method’s ability to achieve near-perfect tracking accuracy with significantly lower computational overhead highlights its efficiency and reliability. While the optimization solver is robust in its ability to find a valid solution for every point, its performance is inconsistent: rare local minima produce error spikes up to 0.22 m despite sub-centimeter medians, and mean computation time is about eight-fold higher. The custom solver’s roughly 8.1× speedup, tight timing dispersion (median 9.01 ms, 95th percentile 14.07 ms), and predictable multi-branch coverage (mean of 2.6 distinct solutions per pose) make it better suited for real-time control and motion planning. DLS attains slightly lower residuals at a single branch, but lacks branch diversity, while LM occasionally matches the custom accuracy but diverges near singularities. Furthermore, the smoother joint-space trajectories generated by the custom solver are highly desirable for practical robotics, leading to reduced mechanical stress and more fluid robot motion. In summary, for this specific manipulator, the proposed method provides a faster, more accurate, and more reliable solution.

Limitations and Future Work

This study is focused on a specific robotic manipulator and trajectory. Future work could investigate the performance of the solvers on different robot configurations, more complex trajectories, and in the presence of noise or uncertainties. Further research could also explore methods to improve the robustness and efficiency of optimization-based IK solvers, such as incorporating problem-specific knowledge into the optimization algorithm or developing more efficient global optimization techniques. Extension to non-spherical wrists or redundant manipulators would require coupling terms in (2), and may motivate additional manifolds or lightweight Jacobian regularization; we leave this to a follow-up paper focused on non-spherical arms. Near singularities, the refinement step clamps or skips updates when is small and relies on multiple root candidates to switch branches safely; incorporating a damped least-squares wrist fallback is a planned robustness extension. For deployment, a lightweight embedded/FPGA implementation is feasible because the online loop uses only polynomial evaluations, partial-derivative updates, and a closed-form wrist solver; porting and benchmarking on embedded hardware are planned as future work.

7. Conclusions

The custom IK solver significantly outperformed the optimization-based solver in terms of accuracy, computational efficiency, and joint space smoothness for the tested robotic system. While the optimization-based solver demonstrated robustness in finding solutions, its limitations in terms of accuracy, smoothness, and speed highlight the advantages of a specialized custom IK algorithm that leverages the specific kinematic structure of the robot.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.D.; methodology, M.M.D.; software, M.M.D.; validation, M.M.D. and P.S.; formal analysis, M.M.D.; investigation, M.M.D.; resources, P.S.; data curation, M.M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.D.; writing—review and editing, P.S. and M.M.D.; visualization, M.M.D.; supervision, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 4.0 for the purpose of language polishing. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No AI-based tools were used for drafting code or text beyond standard editing assistance.

References

- Sciavicco, L.; Siciliano, B. A solution to the inverse kinematics problem for redundant robots. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1988, RA-4, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Wu, H. Closed-form solution of inverse kinematics for a 4-DOF manipulator. J. Mech. Robot. 2013, 5, 041004. [Google Scholar]

- Drexler, M. Precision and convergence of Crank-Nicolson methods for solving inverse kinematics problems. J. Appl. Math. Phys. 2016, 4, 1283–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Hock, J.; Sedo, R. Jacobian transpose methods for robot inverse kinematics. Mech. Mach. Theory 2018, 126, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, P.; Li, Z.; Zhu, J. Improved Jacobian-based methods for inverse kinematics with bi-directional node positioning technique. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2019, 121, 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zakharov, O.V.; Seliverstova, L.V. Positional Control of 6-DoF Robot Based on an Optimal Inverse Kinematics. In Proceedings of the International Russian Smart Industry Conference (SmartIndustryCon), Sochi, Russia, 24–30 March 2024; pp. 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ning, W.; Wang, Z. Inverse kinematics of a robotic manipulator using back-propagation neural network with Levenberg-Marquardt training. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2017, 95, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Du, C.; Wu, Z. A second-order recurrent neural network for solving the inverse kinematics problem of redundant manipulators. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part B Cybern. 2006, 36, 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Mary, A.; Anbarasan, S. Design and implementation of a PD-like fuzzy logic controller for trajectory tracking of robot manipulators. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 93, 545–551. [Google Scholar]

- Hendarto, R.; Rachmadita, F.; Hariadi, R. ANFIS-based inverse kinematics for PUMA 560 robotic arm. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2015, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Libera, P.D.; Carli, D. Gaussian Process Regression for inverse dynamics in robotics. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 1312–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Perovic, G.; Piqué, F. Mitigating Stochasticity in Visual Servoing of Soft Robots Using Data-Driven Generative Models. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 2341–2349. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann, E.; Polte, M. Increasing the Absolute Position Accuracy of Industrial Robots by Means of a Deep Continual Evidential Regression Model. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 4774–4780. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Barragan, O.; Perez-Oria, J.; Escalera, D. Firefly algorithm for inverse kinematics in robotic systems. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2019, 52, 100604. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, R.; Adams, A.; Kapoor, R. Sparse hierarchical IK for humanoid robots. Auton. Robot. 2020, 44, 923–939. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Zhou, L.; Xue, S. Particle swarm optimization combined with analytical methods for inverse kinematics. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 35571–35582. [Google Scholar]

- Rathnam, R.; Godfrey, W.W. Neural network-based inverse kinematics for 2D and 3D robotic systems. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2019, 120, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rathnam, R.; Godfrey, W. Data Driven Approach for Inverse Kinematics in 2D and 3D. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Technologies (CICT), Jabalpur, India, 15–17 December 2023; Volume 2023, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Lin, H. FPGA-based inverse kinematics system for SCARA robots. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2018, 62, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Z.; Liu, L. Anchor point and virtual link methods for redundant manipulator inverse kinematics. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 874–885. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.