Abstract

Ischemic heart disease remains the leading cause of cardiovascular mortality worldwide. In myocardial infarction (MI), extracellular vesicles (EVs)—particularly small EVs (sEVs)—transport therapeutic cargo such as miR-21-5p, which suppresses apoptosis, and other proteins, lipids, and RNAs that can modulate cell death, inflammation, angiogenesis, and remodeling. This review synthesizes recent mechanistic and preclinical evidence on native and engineered EVs for post-MI repair, mapping therapeutic entry points across the MI timeline (acute injury, inflammation, and healing) and comparing EV sources (stem-cell and non-stem-cell), administration routes, and dosing strategies. We highlight engineering approaches—including surface ligands for cardiac homing, rational cargo loading to enhance potency, and biomaterial depots to prolong myocardial residence—that aim to improve tropism, durability, and efficacy. Manufacturing and analytical considerations are discussed in the context of contemporary guidance, with emphasis on identity, purity, and potency assays, as well as safety, immunogenicity, and pharmacology relevant to cardiac populations. Across small- and large-animal models, EV-based interventions have been associated with reduced infarct/scar burden, enhanced vascularization, and improved ventricular function, with representative preclinical studies reporting approximately 25–45% relative reductions in infarct size in rodent and porcine MI models, despite substantial heterogeneity in EV sources, formulations, and outcome reporting that limits cross-study comparability. We conclude that achieving clinical translation will require standardized cardiac-targeting strategies, validated good manufacturing practice (GMP)-compatible manufacturing platforms, and harmonized potency assays, alongside rigorous, head-to-head preclinical designs, to advance EV-based cardiorepair toward clinical testing.

1. Introduction

MI remains a major global cause of morbidity and mortality despite improvements in timely reperfusion, with incident heart failure (HF) still frequent after MI: across contemporary cohorts, post-MI HF occurs in roughly 10–15% of patients at 1 year, escalating to nearly 25% in high-risk populations [1,2,3]. Although primary percutaneous coronary intervention reduces acute mortality, there is still no proven adjunct that consistently limits ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury or downstream microvascular obstruction (MVO) in randomized trials; large studies targeting mitochondrial permeability-transition pore opening or using remote ischemic conditioning showed no clinical benefit [4,5,6]. MVO detected by cardiac MRI remains a robust marker of adverse remodeling and outcomes after ST-elevation MI, underscoring the need for strategies that protect both myocardium and the microvasculature [7,8]. Unlike single-target pharmacologic or conditioning approaches, EVs deliver pleiotropic cargo capable of simultaneously addressing cardiomyocyte death, inflammation, and microvascular injury—potentially overcoming the limitations of single-mechanism interventions [9,10,11,12]. In this setting, EVs can transfer cardioprotective cargo and modulate post-MI repair in vivo; preclinical work shows EVs derived from cardiac or mesenchymal sources reduce infarct size and improve function, and bioengineering can further enhance targeting and potency [9,10,11,12]. Engineering strategies span (i) optimizing donor cell sources, (ii) preconditioning donor cells, (iii) molecular and surface engineering of EVs, and (iv) carrier engineering to enhance EVs delivery; collectively, these approaches have improved EV biodistribution and functional recovery in rodent MI models, and EV-based therapies have also shown benefit in selected large-animal (porcine) MI studies, but translation has not yet progressed to human MI trials and therefore remains at a preclinical stage [10,11,12,13,14]. Collectively, converging evidence supports EVs—especially engineered EVs—as a modular, microenvironment-responsive platform to address both myocyte death and microvascular injury after MI, but future trials must resolve manufacturing, dosing, and targeting at clinical scale [12,13,14].

2. Basic Mechanisms: EVs Biology and MI Pathophysiology

EVs are membrane-bound nanovesicles (~30–150 nm) that carry proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids within a protective lipid bilayer, enabling transfer of this cargo between cells and contributing to intercellular signaling in cardiovascular disease [15,16]. In MI, necrotic cardiomyocytes release damage-associated molecular patterns such as HMGB1, which activate pattern-recognition receptors and trigger an innate immune cascade characterized by rapid neutrophil influx within hours, followed by recruitment and phenotypic reprogramming of monocytes–macrophages over several days; these innate immune cells critically shape infarct expansion, resolution of inflammation, and scar formation [17,18,19]. EVs can modulate several steps in this injury–inflammation–repair sequence through distinct mechanisms, including anti-apoptotic, pro-angiogenic, and immunomodulatory effects, as demonstrated across preclinical models.

Anti-apoptotic effects of EVs have been primarily linked to microRNA cargo that inhibits cell death pathways. For instance, in rodent ischemia–reperfusion models, mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (MSC)–derived EVs enriched in miR-21a-5p exhibit anti-apoptotic effects by targeting pro-apoptotic genes; when miR-21a-5p is deleted or inhibited in the EVs source, cardioprotection is markedly attenuated, whereas restoring miR-21a-5p expression or delivering miR-21a-5p–loaded EVs rescues these benefits in vivo [20].

Building on these protective mechanisms, the pro-angiogenic effects of EVs support vascular repair and tissue perfusion post-MI. MSC–derived EVs also promote angiogenesis through miR-21a-5p [20], while reparative M2 macrophage–derived EVs enhance angiogenesis and improve functional recovery, in part via transfer of miR-132-3p that targets the anti-angiogenic protein thrombospondin-1 (THBS1); in contrast, pro-inflammatory macrophage EVs carry microRNAs and proteins that tend to sustain inflammatory signaling and impair vascular repair [21,22]. Similarly, the endothelial microRNA miR-126—strongly pro-angiogenic—contributes to cardioprotection when delivered via EVs: exosomes loaded with miR-126 (alone or in combination with miR-146a) enhance neovascularization, reduce infarct size, and improve cardiac function in rat MI and ischemia–reperfusion models, and plasma exosomes enriched in miR-126a-3p after remote ischemic preconditioning confer protection against MI/R injury [23,24]. These findings are corroborated in large-animal models, where EVs from cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs) delivered into infarcted pig hearts reduce scar size and improve left ventricular function, supporting a causal role for CDC-EVs in promoting repair [10].

Immunomodulatory effects of EVs further influence the inflammatory milieu, with macrophage-derived EVs playing a pivotal role based on polarization state. Reparative M2 macrophage EVs not only drive angiogenesis but also modulate anti-inflammatory pathways, such as through Y RNA fragments that enhance IL-10 expression and secretion to confer cardioprotection [21], whereas pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage EVs perpetuate inflammation [22].

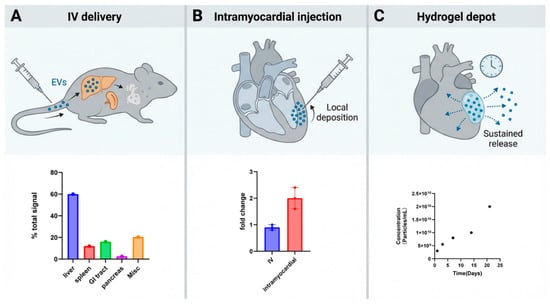

Although these mechanisms are encouraging, natural EVs carry only modest payloads, and unmodified EVs exhibit limited intrinsic cardiac targeting. After intravenous administration in small-animal models, most EVs accumulate in the liver, spleen, and other reticuloendothelial organs, with >70% hepatic uptake and <5% cardiac accumulation in rodent biodistribution studies [25], with relatively low uptake in the injured myocardium. EVs biodistribution is shaped by EVs surface molecules and target-cell receptors: for example, exosomal integrins can direct organotropic uptake, and cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) act as key receptors for EV internalization in multiple tissues [26,27]. However, available data indicate that, without additional engineering, systemically delivered EVs do not selectively home to cardiac tissue [15,16]. Therefore, delivery strategy is critical: in MI models, direct intramyocardial injection or local biomaterial depots—such as injectable shear-thinning hydrogels or fibrin-based cardiac patches—substantially increase local EVs retention, reduce fibrosis, and enhance functional benefit, while encapsulation of EVs in hydrogels (including EPC- or hiPSC-derived EVs) enables sustained release in the infarct zone [28]. Furthermore, engineering EVs membranes with targeting ligands or exploiting integrin–receptor interactions has been shown to enhance uptake by desired organs, providing a rationale for developing cardiac-targeted EV formulations [1,17,27]. Altogether, these mechanistic insights support the advancement of targeted EV therapies in MI while underscoring key translational challenges in biodistribution, dosing, and delivery. “Figure 1 illustrates the route-dependent biodistribution and retention of extracellular vesicles (EVs), highlighting the differences between systemic, intramyocardial, and hydrogel-encapsulated delivery strategies. This figure visually reinforces the importance of selecting the appropriate delivery method to achieve optimal EV retention and functional benefit in myocardial infarction (MI) models.”

Figure 1.

Route-dependent biodistribution/retention of EVs. (A) Following intravenous (IV) delivery, EVs enter systemic circulation and are predominantly sequestered by reticuloendothelial organs; the representative ex vivo organ distribution (bottom) illustrates liver- and spleen-dominant uptake with comparatively low cardiac signal, consistent with route-dependent EV biodistribution patterns reported in vivo. (B) With intramyocardial injection, EVs are deposited directly into the myocardium (top), resulting in higher early cardiac retention; the bottom bar plot summarizes a representative quantification showing increased heart-associated signal after intramyocardial administration compared with IV delivery (fold change relative to PBS control). (C) Hydrogel depot delivery places EVs within a local biomaterial reservoir adjacent to/within the myocardium (top), enabling sustained, localized availability over time (bottom), a strategy widely used to prolong EV exposure at target sites. EVs are released from the gel over time to permit cellular uptake. Cumulative EV release profile from the shear-thinning gel (n = 2) shows steady particle release over 21 days (bottom) [29].

3. Therapeutic Effects of EVs in Cardiac Repair

Across rodent and large-animal models of MI, therapeutic EVs from mesenchymal, progenitor, endothelial, and immune cells produce quantifiable improvements in infarct size, left-ventricular (LV) function, and angiogenesis. In a porcine permanent-ligation MI model, seven days of intravenous human mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)–derived small EVs reduced infarct size by approximately 30–40% at both 7 and 28 days compared with vehicle and lessened infarct transmurality and wall thinning, with relative preservation of regional LV wall thickening on cardiac MRI [30]. In acute and chronic porcine MI, intramyocardial delivery of cardiosphere-derived cell (CDC) exosomes reduced the infarct size–to–area-at-risk ratio from about 80% to roughly 60% at 48 h and attenuated the 1-month decline in LV ejection fraction (LVEF) by several percentage points compared with controls, while decreasing scar mass and increasing vessel density in treated segments [10].

In a rat MI model, human bone-marrow MSC–derived EVs significantly reduced fibrotic scar area and improved LV systolic function, accompanied by higher capillary and arteriolar densities in the peri-infarct zone on CD31/von Willebrand factor and α-smooth muscle actin staining, indicating robust pro-angiogenic remodeling [31]. Genetically engineered EVs further enhance these quantitative effects: in rats, MSC-EVs overexpressing hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) produced greater improvements in LVEF and fractional shortening, smaller fibrotic area, and increased capillary counts per high-power field than both PBS and unmodified MSC-EVs, in parallel with up-regulation of VEGF and related pro-angiogenic factors [32]. Likewise, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF)–induced up-regulation of miR-133a-3p in MSC-derived exosomes augmented their efficacy in rat acute MI, yielding additional gains in echocardiographic LV function, further reductions in TTC-defined infarct size, and higher CD31+ microvessel density compared with native EVs [33].

EVs from non-mesenchymal sources show similar quantitative trends. In a murine MI model, exosomes from human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived endothelial cells (hiPSC-ECs) improved myocardial contractile function, limited adverse LV remodeling, and reduced infarct size, while hiPSC-EC exosomes also directly enhanced endothelial tube formation in vitro, consistent with a pro-angiogenic profile [34]. M2 macrophage–derived exosomes injected at the onset of MI likewise improved echocardiographic indices of systolic function, reduced infarct size, and enhanced CD31+ vessel density in ischemic myocardium by delivering pro-angiogenic miR-132-3p to endothelial cells and suppressing the anti-angiogenic target THBS1 [22]. Collectively, these preclinical data indicate that natural EV preparations from MSCs, CDCs, hiPSC-ECs, and M2 macrophages can reduce infarct burden by up to roughly one-third in porcine MI and consistently improve LV function and histological measures of angiogenesis, whereas engineered EVs carrying HIF-1α or miR-133a-3p provide additional, quantifiable increments in functional recovery [1,2,3,4,5,6,7].

4. Engineering Strategies for Enhanced EV Efficacy

To unlock the therapeutic potential of EVs in MI, engineering strategies are being used to address key limitations—restricted effective cargo capacity suboptimal cardiac tropism,, and rapid clearance. Current efforts concentrate on (i) optimizing donor-cell sources; (ii) preconditioning donor cells to increase yield and enrich reparative cargo; and (iii) molecular engineering of EVs for enhanced efficacy to strengthen cardioprotective signaling and myocardial targeting. These strategies have led to significant improvements in the therapeutic efficacy of engineered exosomes. The table below summarizes various optimization approaches, detailing the exosome sources, engineering techniques, administration routes, experimental models, and the main therapeutic endpoints for MI treatment. It highlights the diverse strategies employed to enhance the functionality and targeted delivery of exosomes, demonstrating their potential to improve cardiac regeneration and repair. Table 1. Optimization strategies for exosome-based therapies in MI, detailing exosome sources, optimization strategies, administration routes, experimental models, and main therapeutic outcomes.

Table 1.

Optimization strategies for exosome-based therapies in MI.

4.1. Optimizing Donor-Cell Sources

The donor cell determines EVs yield and baseline cargo composition, thereby shaping therapeutic potential.

Among cell sources, MSCs are the most extensively used for therapeutic EV production because they expand readily and support scalable upstream/downstream bioprocessing—e.g., serum/xeno-free microcarrier bioreactors and tangential-flow filtration (TFF)—while generally exhibiting favorable immune profiles that ease allogeneic use [27,28,34]. For the mechanism, bone-marrow MSC–derived EVs (BM-MSC-EVs) can deliver miR-21-5p that suppresses PTEN and activates PI3K/AKT in cardiac recipient cells, limiting apoptosis (shown in vitro with BM-MSC-EVs) and, when miR-21-5p–rich MSC-EVs are applied in vivo, associating with smaller infarcts and improved left-ventricular function in rodent MI models (the in vivo benefit is not BM-specific and reported with alternative miR-21-5p targets as well) [44,48]. Adipose-derived MSC-EVs (AD-MSC-EVs) support neovascularization and post-MI repair; these effects are markedly enhanced when miR-126 is engineered/enriched in the vesicles, whereas native AD-MSC-EVs cargo varies across studies and consistent endogenous miR-126 or uniformly high VEGF content is not established [11,59]. Cardiac-progenitor–cell EVs (CPC-EVs) carry cardioprotective miRNA signatures and improve early function in rat MI, and a GMP-oriented CPC-EVs workflow (including TFF and release testing) has been described, although CPC expansion/yields are typically more demanding than for MSCs [60]. Endothelial/EPC-EVs are enriched for endothelial miRNAs such as miR-126 and show pro-angiogenic activity in vivo—including improved perfusion and function after MI with sustained intramyocardial delivery—yet large-scale culture and GMP standardization remain shared challenges across EV therapeutics [61]. In practice, MSC-EVs often provide a pragmatic platform balancing scalability, immune compatibility, and reparative cargo, while CPC-EVs and EC/EPC-EVs are pursued to emphasize targeted endpoints such as cardiomyocyte survival or angiogenesis [41,42,49,52].

4.2. Preconditioning Donor Cells

Beyond intrinsic cell-type features, preconditioning can further bias EVs payloads toward pro-repair signals. The current preconditioning approaches mainly include: (i) hypoxic preconditioning; (ii) drug/molecular preconditioning; and (iii) genetic engineering of donor cells.

4.2.1. Hypoxic Preconditioning

Culturing donor MSCs under physiological hypoxia (~1–5% O2 for 24–48 h) stabilizes HIF-1α expression, activates canonical hypoxia-inducible programs including upregulation of VEGF-A and CXCL12/SDF-1, enhances levels of hypoxia-responsive miR-210, and alters the molecular cargo of secreted EVs [12,13,29,35,36,62]. In rodent MI models, EVs derived from hypoxia-preconditioned MSCs reduce cardiomyocyte apoptosis and enhance post-MI cardiac function compared to those from normoxic MSCs, at least in part because hypoxia increases the loading of miR-210 and miR-125b-5p into these vesicles; knockdown of miR-125b-5p in these EVs diminishes cardioprotective effects in vivo [12,13]. For AD-MSC-EVs, hypoxia preconditioning augments angiogenic potential in vitro and in vivo, associated with increased miR-126-5p in non-cardiac diabetic wound models [29]. Collectively, hypoxia preconditioning shifts EV contents toward pro-angiogenic and pro-survival pathways (e.g., miR-210 and miR-125b-5p, with context-dependent miR-126-5p involvement), supporting improved tissue repair in preclinical MI models, though benefits vary by study and model.

4.2.2. Drug/Molecular Preconditioning

Pharmacologic (drug/molecular) priming of donor cells reliably reprograms the cargo of native EVs and can augment myocardial repair in rodent acute MI models, although the magnitude and mechanisms vary by agent and context. In rats, exosomes from atorvastatin-pretreated MSCs reduce infarct size and improve function via upregulated lncRNA H19/miR-675 signaling [38], and in an independent MI study, atorvastatin-primed MSC-EVs promote anti-inflammatory macrophage M2 polarization by delivering miR-139-3p that targets STAT1, thereby enhancing post-MI healing [15]. Beyond statins, nicorandil pretreatment produces MSC-exosomes enriched in miR-125a-5p that repress TRAF6/IRF5, driving M2 polarization and improving ventricular remodeling after MI in rats [16]. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) pharmacology has also been applied: Tongxinluo-pretreated MSCs yield exosomes carrying higher miR-146a-5p, which targets IRAK1/NF-κB p65 to lessen cardiomyocyte apoptosis and inflammation and to improve left-ventricular function in MI [17]. Finally, nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) preconditioning of human umbilical cord MSCs generates EVs enriched in miR-210-3p that targets EFNA3, promoting angiogenesis and reducing fibrosis with functional recovery in rat MI [18]. Collectively, across these original MI studies, pharmacologic priming can shift native EV miRNA/lncRNA payloads toward pro-repair programs.

4.2.3. Genetic Engineering of Donor Cells

Genetic modification of donor cells can be leveraged to engineer EVs toward three major therapeutic objectives in MI: suppressing cardiomyocyte death, improving cardiac targeting, and prolonging EV persistence via immune evasion. At the anti-apoptotic level, MSCs overexpressing miR-21-5p secrete EVs enriched in miR-21, which target and suppress pro-apoptotic genes such as PTEN and PDCD4 [46]. In rodent MI models, delivering these miR-21-rich EVs inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improves post-MI cardiac function, largely via EV-carried miR-21 downregulating YAP1 in recipient cardiomyocytes [63]. Similarly, EVs derived from MSCs engineered to overexpress miR-214-3p promote endothelial migration and tube formation and enhance cardiomyocyte survival under ischemia. In a rat acute MI model, treatment with miR-214-3p-enriched EVs reduces myocardial apoptosis, decreases infarct size, boosts peri-infarct angiogenesis, and improves cardiac function by transferring miR-214-3p that inhibits PTEN and activates AKT signaling [47]. Additional anti-death modifications include forced expression of the transcription factor GATA-4 in bone-marrow MSCs: exosomes from GATA-4-overexpressing cells carry increased levels of miR-330-3p, which inhibits ferroptosis in hypoxia/reoxygenation-injured cardiomyocytes by targeting the BAP1/SLC7A11 pathway [50]. Consistently, administering GATA4-engineered exosomes after MI reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improves cardiac function in infarcted hearts [51]. To improve targeting to the injured heart, donor cells can be engineered to present cardiac-homing ligands on EVs membranes. For example, an ischemic myocardium-homing peptide fused to the exosomal membrane protein Lamp2b in MSCs produces exosomes that accumulate more in the ischemic heart and provide greater therapeutic benefit in MI models [54]. Likewise, donor cells expressing a cardiomyocyte-specific binding peptide fused to Lamp2b generate EVs that are taken up more efficiently by hypoxic cardiomyocytes and show enhanced cardiac retention in vivo, leading to reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis [12]. Native homing receptors can also be exploited: cardiac progenitor cells overexpressing the chemokine receptor CXCR4 produce exosomes displaying CXCR4 on their surface; after systemic administration in MI rats, these CXCR4-bearing exosomes exhibit improved targeting to ischemic myocardium, resulting in smaller infarcts and better recovery of left ventricular function compared with control EVs [49]. Finally, engineering EVs to display “don’t-eat-me” signals can enhance immune evasion and prolong circulation. Overexpression of CD47 in EV-producing cells increases EVs surface CD47, enabling EVs to avoid macrophage-mediated phagocytosis [57]. Such CD47-decorated EVs persist longer in the bloodstream and accumulate more in the injured heart, translating into superior functional recovery after MI relative to unmodified EVs [57]. Collectively, these examples show that rational genetic engineering of donor cells to deliver anti-apoptotic cargo, cardiac-targeting ligands, or immune-evasive markers can markedly increase EV retention in infarcted myocardium and amplify their therapeutic efficacy in MI models.

4.3. Molecular and Surface Engineering of EVs

Beyond donor-cell programming, direct molecular engineering during or after EVs biogenesis enables precise loading of therapeutics and surface functionalization with targeting ligands. For small-molecule loading, heart-targeted EVs bearing a cardiac-targeting peptide (CTP) and co-loaded with curcumin and miR-144-3p displayed higher myocardial residence, lowered oxidative stress and apoptosis, and improved post-MI function in rodents, pointing to gains conferred by engineered surfaces plus exogenous payloads rather than native cargo alone [21]. A related two-step platform that briefly reduces mononuclear-phagocyte uptake using DOPE-PEG–CTP before administering curcumin-loaded EVs further enhanced antioxidant effects and left-ventricular performance in mouse MI, again emphasizing the value of pairing cardiac targeting with small-molecule encapsulation [39]. For protein cargo, umbilical-cord MSC–derived engineered nanovesicles covalently modified with a cardiac-homing peptide and loaded with placental growth factor (PLGF) increased cardiac retention, stimulated angiogenesis and cardiomyocyte proliferation, reduced fibrosis, and improved ventricular function in MI rodents, illustrating a feasible protein-loading path when combined with targeting chemistry [53]. Independent surface-functionalization strategies likewise improved delivery without altering native cargo: DOPE-NHS conjugation of the ischemic-myocardium homing peptide CSTSMLKAC to EVs increased cardiac accumulation and was associated with better ejection fraction, angiogenesis, and scar reduction after MI/I-R in rats [64], while exosomes presenting an ischemic myocardium-targeting peptide via donor-cell engineering achieved enhanced homing and therapeutic benefit in MI [54]. Donor-cell display of a cardiomyocyte-binding peptide (Lamp2b-fusion) increased uptake by hypoxia-injured cardiomyocytes, reduced apoptosis, and improved in vivo cardiac retention after intramyocardial delivery in rodents [4]. Collectively, these studies support molecular engineering—via exogenous small-molecule/protein loading and cardiac-focused surface functionalization—as a generalizable route to elevate EVs residence at the infarct and amplify therapeutic impact in MI.

5. Carrier Engineering to Enhance EV Delivery

Therapeutic performance of EVs–based interventions is often constrained by rapid systemic clearance and limited deposition at target sites. To address these barriers, this section focuses on carrier engineering to stabilize EVs, localize payloads, and enable programmable targeting while preserving biocompatibility. Current approaches fall into two categories: biomaterial carriers for localized EV delivery and synthetic or hybrid EV carrier systems.

5.1. Biomaterial Carriers for Localized EV Delivery

Embedding EVs in biocompatible hydrogels or scaffolds can create local depots that prolong residence and sustain release at the injury site, thereby enhancing functional benefit relative to bolus EVs. In rodent cardiac models, an injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) “ExoGel” loaded with MSC-derived exosomes and delivered into the pericardial space preserved wall thickness and reduced dilation versus controls; the same approach demonstrated feasibility and acute safety of intrapericardial delivery in a porcine model, but did not assess efficacy outcomes, aligning with the broader limitation that large-animal efficacy data remain sparse [56]. In osteoarticular repair, intra-articular EVs delivery improves cartilage structure and pain in rodent models, and combining EVs with HA can further support defect repair in rabbits, consistent with the depot concept [65,66]. Across tissues, hydrogels and related scaffolds generally act by stabilizing/retaining native vesicle cargo near the lesion rather than “increasing dose,” but head-to-head large-animal comparisons and standardized long-term safety remain sparse.

5.2. Synthetic and Hybrid EV Carrier Systems

Engineering carriers can add control and targeting beyond passive depots. Hybrid vesicles formed by fusing EV membranes with liposomes preserve EVs’ biocompatibility while improving nucleic-acid loading and delivery; for example, MSC exosome–liposome hybrids transfected large Cas9-GFP plasmids into human HEK293T cells more efficiently than plasmid alone, supporting the principle though in vivo efficacy remains to be established [67]. From a translational perspective, such hybrids could in principle exploit existing liposomal manufacturing platforms, but scalable, GMP-compliant fusion processes that preserve EVs surface markers and cargo composition have not yet been standardized, and batch-to-batch variability remains a concern. Clinically, their most realistic near-term application may be ex vivo gene editing or local administration where high nucleic-acid payloads are needed, rather than repeated systemic dosing of a complex chimeric biological–synthetic drug product. External-field guidance is another approach: magnetically steerable, muscle-derived exosomes tethered to ferromagnetic nanotubes were directed to dystrophic muscle in mice and enhanced tissue repair in a Duchenne muscular dystrophy model, illustrating on-demand localization after systemic dosing [68]. However, translation will require scalable production of ferromagnetic nanotubes with tightly controlled magnetic properties and rigorous toxicology of long-term nanotube retention in muscle and off-target organs. In patients, clinically acceptable magnetic-steering paradigms would likely be limited to anatomically accessible muscle groups or organs that can be bracketed by external magnets, and integration with imaging for real-time field placement will be needed. Compared with untargeted EVs infusion, magnetic guidance may be particularly advantageous when focal delivery to relatively superficial tissues is sufficient to achieve therapeutic benefit. Biomimetic cloaking further extends this concept: platelet-membrane–exosome hybrids showed superior ischemic-heart targeting with reduced macrophage clearance and improved repair in mouse MI [69]; more recently, neutrophil-derived apoptotic body–membrane–fused exosomes leveraged inflammation-homing signals to adhere to injured endothelium and improved function and remodeling in MI mice [55]. For both strategies, manufacturing at scale will depend on reliable sourcing and processing of human platelets or neutrophil-derived apoptotic bodies, stringent pathogen screening, and control of prothrombotic or proinflammatory components. In terms of clinical positioning, platelet cloaking may be preferable when prolonged circulation and homing to thrombus-associated or ischemic vascular lesions are desired, whereas neutrophil-mimetic exosomes may be better suited for acute, highly inflamed myocardial tissue where transient adhesion to activated endothelium is critical. Direct head-to-head comparisons and standardized safety assays for thrombosis, immunogenicity, and off-target inflammation will be essential before either biomimetic cloak can Sbe advanced toward early-phase clinical trials.

6. Manufacturing and Quality Control of Clinical-Grade EVs

Scalable, reproducible manufacturing and rigorous quality control (QC) are prerequisites for translating EV therapies to patients. Recent primary studies demonstrate that switching from planar (2D) culture and ultracentrifugation to bioreactors and modern downstream processing can increase EVs output while maintaining identity and bioactivity, whereas field guidelines (e.g., MISEV2018/2023) outline minimal characterization requirements for clinical development [70,71,72]. To place these considerations in the context of practical bioprocess design, Table 2 summarizes commonly used EVs isolation and purification methods, highlighting their typical applicability, purity, yield, and potential impact on EV biological function.

Table 2.

Overview of common EVs isolation and purification methods: applicability, purity, yield, and impact on EV function.

6.1. Scalable Production Methods

Multiple 3D culture platforms now support clinically relevant EV yields. In umbilical-cord MSCs (UC-MSCs), a hollow-fiber bioreactor increased exosome yield ~7.5-fold versus matched 2D flasks while preserving vesicle size/markers and enhancing function in vivo, providing sufficient material to support weekly intra-articular injections over a 4-week osteochondral defect study in 15 rabbits without depleting production capacity [81]. Stirred-tank reactors (STRs) with microcarriers have also been operated under xenogeneic-free conditions to enable continuous EV harvests; in one controlled STR workflow using Wharton’s jelly MSCs, the process achieved ~1.26 × 104 particles per cell per day with high particle-to-protein ratios and intact uptake/activity readouts [71]. In the same system, a representative 3-day production phase from ~6 × 107 cells yielded ~2.1 × 1012 particles, illustrating that even small-scale STR runs can supply 1012-level EV quantities suitable for preclinical and early-phase clinical investigations [71]. Beyond upstream culture, coupling 3D production with tangential-flow filtration (TFF) downstream has delivered order-of-magnitude gains in recovered EVs and improved bioactivity compared with 2D plus ultracentrifugation [70]. Collectively, these primary data support hollow-fiber and microcarrier-STR platforms as viable routes to mitigate the yield bottleneck relative to flasks while maintaining EV attributes within tested contexts.

6.2. Advanced Purification Technologies

Downstream choices involve trade-offs between throughput, purity, and scalability. Differential ultracentrifugation (DUC) is widely used but can co-isolate protein/lipoprotein contaminants from biofluids and media [75,82]. In head-to-head studies, size-exclusion chromatography (SEC)—often preceded by TFF/ultrafiltration for volume reduction—improves purity and/or recovery relative to DUC and precipitation kits, and can be completed within hours at lab scale [75,82,83,84,85]. Hybrid trains such as TFF → SEC or SEC → ultracentrifugation further reduce soluble proteins and apolipoproteins in plasma-derived sEVs [83,84]. Immunoaffinity capture (e.g., anti-tetraspanin) isolates marker-defined subpopulations but, by design, excludes other EV subsets and currently poses scale/cost constraints despite promising high-throughput formats [47,49]. Emerging label-free microfluidic/acoustofluidic approaches can separate EVs from lipoproteins continuously, but typical μL–mL per hour throughputs remain a limitation for large-volume manufacturing [86]. In practice, platform selection should align with intended clinical dose and batch size; scalable combinations such as TFF pre-concentration with SEC polishing are increasingly favored when both yield and purity are required [41,44,46].

6.3. Robust Quality Control (QC) Frameworks

For clinical-grade EVs, QC spans identity, purity, safety, and (ideally) potency. MISEV2018/2023 recommends orthogonal characterization of size/concentration (e.g., nanoparticle tracking analysis), morphology (TEM/cryo-EM), and protein markers (≥1 transmembrane/GPI-anchored such as CD9/CD63/CD81, plus negative markers to flag contaminants) [72,73]. Safety testing typically includes sterility, mycoplasma, and endotoxin assays under GMP-compliant conditions; recent large-scale manufacturing studies of UC-MSC sEVs demonstrate that such release panels can be met in practice, with Wharton’s jelly MSC–derived sEV batches fulfilling predefined endotoxin, mycoplasma, and sterility criteria, although the precise numeric limits remain process- and jurisdiction-dependent [71,87]. Related hollow-fiber bioreactor workflows for bone marrow MSC-EVs produced under current GMP procedures further exemplify scalable, clinically oriented manufacturing strategies [88]. Potency assays (e.g., endothelial tube formation, migration, macrophage modulation) are widely used to benchmark bioactivity during process development, and recent primary work demonstrates assayable changes in angiogenesis-related activity with defined manufacturing variables such as culture substrate stiffness or other controlled mechanical cues [89]. Nevertheless, no individual in vitro potency assay has been prospectively validated as a surrogate for clinical benefit in EVs trials, and available data linking assay readouts to patient outcomes remain sparse and indication-specific [90]. This lack of clinically validated potency metrics constitutes a major translational bottleneck, complicating cross-study comparability, dose selection, and regulatory acceptance of EVs products [90]. Together, adherence to MISEV-guided identity/purity characterization, GMP-aligned sterility, mycoplasma, and endotoxin controls, and fit-for-purpose, mechanism-informed potency assays currently provide a defensible minimum QC framework for clinical-grade EVs, but this framework will need to be iteratively refined as outcome-linked potency criteria and pharmacodynamic biomarkers are established in larger, well-controlled clinical studies [71,72,73,87,88,89,90].

7. Challenges and Future Prospects

Despite encouraging preclinical signals and tangible progress in EV engineering and manufacturing, several barriers still hinder the translation of EVs therapies for post-MI repair.

7.1. Challenges of Quality Control

EVs preparations are intrinsically heterogeneous in size, composition, and biogenesis and are frequently admixed with non-vesicular extracellular particles (e.g., lipoproteins), so heterogeneity and co-isolates themselves constitute a central QC challenge by complicating standardization, release testing, and lot-to-lot comparability [72]. From a QC standpoint, side-by-side single-particle studies show that the isolation workflows summarized in Section 6 (e.g., ultracentrifugation, SEC, density gradients, TFF-SEC, TIM4-affinity) yield EVs populations with different co-isolate burdens and detectable subpopulations and can bias single-particle readouts—for example, higher apparent “EVs-positive” flow-cytometric events after ultracentrifugation than after SEC or TIM4-based capture due to non-EVscontaminants [91]. Single-EVs analyses further demonstrate biological heterogeneity (e.g., uneven tetraspanin distribution; only a subset of vesicles carrying detectable DNA cargo), but they also reveal pronounced method-dependent detection, underscoring how difficult it is to define QC thresholds that are robust across platforms and protocols [92,93]. MISEV2023 explicitly acknowledges these issues and cautions that no single quantitative readout—including the often-used particle-to-protein ratio—can be treated as a universal purity metric; instead, it recommends context-specific multi-assay panels together with improved removal and quantitative measurement of co-isolates such as albumin and ApoB-containing lipoproteins [72,84]. Collectively, ongoing adoption of single-particle methods and quantitative immunoassays alongside advanced omics is needed to define critical quality attributes with higher precision [72,84,91], but the field still lacks consensus, operational CQAs and acceptance criteria that can be applied consistently across manufacturing processes, indications, and clinical centers, as also emphasized by recent EV therapeutics reviews that frame EVs as biopharmaceuticals whose “process defines the product” and highlight heterogeneity- and co-isolate–driven challenges for regulatory quality assessment [94,95].

7.2. In Vivo Targeting and Biodistribution

After intravenous dosing, native EVs display predominant liver/spleen (mononuclear phagocyte system) uptake with relatively low myocardial accumulation, as shown by quantitative imaging and ex vivo analyses in rodents; systematic reviews reach similar conclusions across models [16,64]. Surface engineering can improve—but not abolish—this pattern: cardiotropic peptide display (e.g., CSTSMLKAC fused to LAMP2b) increases cardiac localization and modestly improves post-MI function in mice, yet off-target hepatic and splenic deposition remains substantial [64,96]. Whole-body, time-resolved quantification is increasingly feasible: PET/SPECT studies (e.g., ^89Zr-labeled engineered EVs) enable route-dependent kinetic profiling in rodents and non-human primates, while iron-oxide approaches enable MRI tracking with variable sensitivity and standardization [40,54]. Together, these data support a realistic expectation that targeting augments rather than transforms biodistribution, and that quantitative nuclear imaging will be valuable for dose/route optimization prior to clinical translation [16,64,96,97].

7.3. Immunogenicity and Safety Assessment

Although EVs are endogenous in origin, immune effects depend on source, dose, purity, and engineering. Tumor-derived EVs can induce neutrophil extracellular traps and accelerate thrombosis in vivo, demonstrating immunostimulatory potential in certain contexts [98], and recent reviews further highlight EVs as central mediators of cancer-associated thrombosis [99]. However, long-term immunogenicity and tumorigenicity datasets for therapeutic EVs, especially engineered products, remain limited and warrant cautious interpretation of current safety profiles. Overall, rigorous control of non-native carryover (e.g., serum-derived vesicles, lipoproteins, endotoxin) and fit-for-purpose immunogenicity panels aligned with MISEV2023 are needed to de-risk development [72,84].

7.4. Clinical Bottlenecks

Progress to late-phase trials is constrained by cGMP manufacturing, validated analytics, and agreed potency criteria. Comparative studies show that upstream culture and isolation choices (e.g., 3D versus 2D expansion, TFF-SEC versus ultracentrifugation) shift apparent yields, purity, and composition, potentially confounding biological readouts [72,91,100]. 3D and perfusion-like systems can increase EV output and, in some reports, augment functional activity in rodent MI, but results are not uniform across platforms and indications [100]. Potency assays remain under qualification: for MSC-EVs, CD73 ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity is mechanistically attractive yet has not consistently correlated with immunomodulatory potency across lots and assays, underscoring the need for validated, fit-for-purpose functional tests rather than single surrogates [101]. Clinically, most EVs trials remain early-phase with heterogeneous endpoints and few qualified translational biomarkers, supporting calls for harmonized CQAs, process controls, and consensus endpoints (e.g., via MISEV2023 and regulator-informed guidance) [102]. Phase I EVs trials should prioritize safety and biodistribution assessments (for instance, using radiolabeled EVs to enable whole-body tracking of EVs distribution and clearance) [103]. Phase II efficacy trials should incorporate rigorous imaging endpoints, such as cardiac MRI to quantify infarct size reduction and improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at ~3–6 months [104]. Additionally, consensus potency assays should be established through collaborative working groups (e.g., ISEV and ISCT) to define standardized, mechanism-informed potency metrics and accelerate regulatory acceptance of EV therapeutics.

7.5. Clinical Translation: Registered Interventional Studies in Cardiovascular Disease

As of December 2025, EsV-based cardiac repair remains predominantly preclinical, with only a limited number of registered interventional studies directly testing EV-containing products in cardiovascular indications (Table 3). Most are early-phase and emphasize safety/tolerability, with exploratory imaging or biomarker readouts rather than definitive clinical efficacy endpoints. For example, SECRET-HF evaluates repeated intravenous infusions of an EV-enriched secretome from iPSC-derived cardiovascular progenitor cells in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, using serious adverse events as the primary outcome over a short follow-up window, alongside exploratory bioactivity/potency and immunologic measures [105]. In the ischemic heart disease setting, a first-in-human intracoronary infusion study administers an EV-containing biological drug (PEP) immediately after PCI/stent placement, with dose-limiting toxicities and maximum tolerated dose as the primary endpoint and cardiac MRI-based scar size and ejection fraction as secondary measures [106]. Another small randomized study in CABG candidates with recent Q-wave MI and severely reduced LVEF evaluates intracoronary/intramyocardial delivery of mesenchymal stem cell–derived exosomes (with or without mitochondria), using ejection fraction and allergic reactions as primary outcomes at 3 months [107]. Beyond the heart, EV-based approaches have also been tested in vascular-complication contexts such as chronic ulcers—conditions that often overlap with peripheral ischemia—where topical plasma-derived exosomes were evaluated with ulcer size metrics as primary outcomes [108]. Collectively, these studies underscore both the promise and the current limitations of translation: the clinical pipeline is still sparse, heterogeneous in product definition and route, and largely focused on establishing safety, dosing feasibility, and measurable target engagement. Standardized product characterization aligned with MISEV principles, harmonized potency assays, and clinically meaningful endpoint strategies will be essential for EV therapeutics to progress beyond proof-of-concept. As shown in Table 3, the clinical trials involving exosome-based therapies in cardiovascular and vascular complications are still in early phases, with a focus on safety, tolerability, and exploratory endpoints.

Table 3.

Overview of Clinical Trials Involving Exosome-Based Therapies in Cardiovascular and Vascular Complications.

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The recent advancements in EVs engineering, particularly for MI therapy, show considerable promise but also underscore the need for clear priorities in translation. Studies have highlighted the potential of EVs to modulate the critical stages of post-MI repair, including inflammation, tissue regeneration, and microvascular recovery. These vesicles, derived from both stem-cell and non-stem-cell sources, have demonstrated the ability to reduce infarct size, enhance vascularization, and improve cardiac function in preclinical models. The therapeutic efficacy of EVs can be further enhanced through bioengineering techniques such as optimizing donor cell sources, preconditioning, surface ligand modification, and the use of biomaterial depots to prolong myocardial residence. For basic and translational researchers, the key takeaway is to delineate the mechanistic pathways and standardize engineering strategies so that different EVs platforms and models can be compared in a rigorous and reproducible manner.

Positioned within the broader landscape of post-MI cardioreparative strategies, EV-based therapeutics occupy a distinct middle ground between cell therapies and conventional biologics/small molecules. Compared with cell transplantation, EVs offer a cell-free, potentially off-the-shelf modality that can recapitulate key paracrine benefits while avoiding issues such as poor engraftment and cell-related arrhythmogenic risk. In contrast to single-target proteins or small molecules, EVs can deliver modular, multi-component cargo (RNAs, proteins, lipids) that may better match the multi-phase biology of post-MI repair. However, EVs share—and in some respects amplify—translational hurdles, including manufacturing and batch consistency at scale, uncertainty in effective dosing and biodistribution, and regulatory classification that depends on source, manipulation, and intended use. Clarifying these comparative advantages and constraints is essential to define where EVs are most likely to add value clinically—most plausibly as adjuncts to reperfusion and guideline-directed therapy, initially in well-defined patient subsets and with imaging-anchored endpoints.

For clinicians and trial designers, the main message is that EVs are currently best positioned as adjuncts to contemporary MI care, and that future clinical studies should refine patient selection, dosing regimens, and clinically meaningful endpoints such as infarct size and ventricular function. For bioengineers, industry partners, and regulators, the critical next steps are to converge on scalable manufacturing, robust potency assays, and pragmatic safety monitoring frameworks that can support progression to late-phase trials.

Despite these opportunities, translating EVs-based therapies into routine clinical practice remains a significant challenge. Key issues include variability in EVs preparations arising from the inherent heterogeneity of EVs populations and differences in isolation and engineering methods, as well as incomplete standardization of quality-control measures such as identity, purity, and potency assays. Looking ahead, several concrete research avenues must be pursued to address these gaps: refining EVs isolation and characterization to improve reproducibility and reduce batch-to-batch variation; advancing targeted delivery systems and dosing strategies to ensure efficient homing to ischemic myocardium; and integrating quantitative imaging approaches (e.g., PET/SPECT) to track EVs biodistribution and guide optimization of delivery routes and doses. Ultimately, the successful translation of EVs-based therapies for post-MI cardiac repair will depend on rigorous preclinical studies with well-defined endpoints, coupled with the establishment of scalable, GMP-compatible manufacturing and safety-monitoring frameworks that can support large-scale, late-phase clinical trials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. and Z.W.; methodology, H.L., J.X., X.W. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.H., H.L., J.X., X.W., J.L., N.X., Q.L., L.Y., Z.W. and Y.W.; data curation, Y.H.; supervision, Z.W.; funding acquisition, Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Johansson, S.; Rosengren, A.; Young, K.; Jennings, E. Mortality and morbidity trends after the first year in survivors of acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2017, 17, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Hammonds, K.; Talha, K.M.; Alhamdow, A.; Bennett, M.M.; Bomar, J.V.A.; A Ettlinger, J.; Traba, M.M.; Priest, E.L.; Schmedt, N.; et al. Incident heart failure and recurrent coronary events following acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Hear. J. 2025, 46, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Abramov, D.; Naseer, M.U.; Van Spall, H.G.C.; Ahmed, F.Z.; Lawson, C.; Dafaalla, M.; Kontopantelis, E.; O Mohamed, M.; Petrie, M.C.; et al. 15-Year trends, predictors, and outcomes of heart failure hospitalization complicating first acute myocardial infarction in the modern percutaneous coronary intervention era. Eur. Hear. J. Open 2025, 5, oeaf013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cung, T.-T.; Morel, O.; Cayla, G.; Rioufol, G.; Garcia-Dorado, D.; Angoulvant, D.; Bonnefoy-Cudraz, E.; Guérin, P.; Elbaz, M.; Delarche, N.; et al. Cyclosporine before PCI in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausenloy, D.J.; Yellon, D.M. Targeting Myocardial Reperfusion Injury—The Search Continues. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1073–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausenloy, D.J.; Kharbanda, R.K.; Møller, U.K.; Ramlall, M.; Aarøe, J.; Butler, R.; Bulluck, H.; Clayton, T.; Dana, A.; Dodd, M.; et al. Effect of remote ischaemic conditioning on clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction (CONDI-2/ERIC-PPCI): A single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Yang, R.; A, X.; Tian, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Zhao, L.; et al. Long-term prognostic role of persistent microvascular obstruction determined by cardiac magnetic resonance for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am. Hear. J. 2025, 290, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Yin, Q.; Yang, Y.; Miao, H.; Han, S.; Chi, Q.; Lv, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Integrating angio-IMR and CMR-assessed microvascular obstruction for improved risk stratification of STEMI patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.G.-E.; Cheng, K.; Marbán, E. Exosomes as Critical Agents of Cardiac Regeneration Triggered by Cell Therapy. Stem Cell Rep. 2014, 2, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallet, R.; Dawkins, J.; Valle, J.; Simsolo, E.; De Couto, G.; Middleton, R.; Tseliou, E.; Luthringer, D.; Kreke, M.; Smith, R.R.; et al. Exosomes secreted by cardiosphere-derived cells reduce scarring, attenuate adverse remodelling, and improve function in acute and chronic porcine myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, L.; Lionetti, V.; Cervio, E.; Matteucci, M.; Gherghiceanu, M.; Popescu, L.M.; Torre, T.; Siclari, F.; Moccetti, T.; Vassalli, G. Extracellular vesicles from human cardiac progenitor cells inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 103, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentkowski, K.I.; Lang, J.K. Exosomes Engineered to Express a Cardiomyocyte Binding Peptide Demonstrate Improved Cardiac Retention in Vivo. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.G.; Ciullo, A.; Marbán, E.; Ibrahim, A.G. Extracellular Vesicles as Therapeutic Agents for Cardiac Fibrosis. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castilla, P.E.M.; Tong, L.; Huang, C.; Sofias, A.M.; Pastorin, G.; Chen, X.; Storm, G.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Wang, J.-W. Extracellular vesicles as a drug delivery system: A systematic review of preclinical studies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 175, 113801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ali, S.R.; Takeda, K.; Vahl, T.P.; Zhu, D.; Hong, Y.; Cheng, K. Extracellular vesicle therapeutics for cardiac repair. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2024, 199, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Jordan, V.; Blenkiron, C.; Chamley, L.W. Biodistribution of extracellular vesicles following administration into animals: A systematic review. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foglio, E.; Pellegrini, L.; Russo, M.A.; Limana, F. HMGB1-Mediated Activation of the Inflammatory-Reparative Response Following Myocardial Infarction. Cells 2022, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciortan, L.; Macarie, R.D.; Barbu, E.; Naie, M.L.; Mihaila, A.C.; Serbanescu, M.; Butoi, E. Cross-Talk Between Neutrophils and Macrophages Post-Myocardial Infarction: From Inflammatory Drivers to Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Anzai, A.; Katsumata, Y.; Matsuhashi, T.; Ito, K.; Endo, J.; Yamamoto, T.; Takeshima, A.; Shinmura, K.; Shen, W.; et al. Temporal dynamics of cardiac immune cell accumulation following acute myocardial infarction. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, K.M.; Haar, L.; McGuinness, M.; Wang, Y.; Lynch, T.L.L., IV; Phan, A.; Song, Y.; Shen, Z.; Gardner, G.; Kuffel, G.; et al. Exosomal miR-21a-5p mediates cardioprotection by mesenchymal stem cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 119, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambier, L.; De Couto, G.; Ibrahim, A.; Echavez, A.K.; Valle, J.; Liu, W.; Kreke, M.; Smith, R.R.; Marbán, L.; Marbán, E. Y RNA fragment in extracellular vesicles confers cardioprotection via modulation of IL-10 expression and secretion. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017, 9, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, Z.; Xiao, B.; Huang, R. M2 macrophage-derived exosomes promote angiogenesis and improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Biol. Direct 2024, 19, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, S. Plasma Exosomes at the Late Phase of Remote Ischemic Pre-conditioning Attenuate Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Through Transferring miR-126a-3p. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 736226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafei, S.; Khanmohammadi, M.; Ghanbari, H.; Nooshabadi, V.T.; Tafti, S.H.A.; Rabbani, S.; Kasaiyan, M.; Basiri, M.; Tavoosidana, G. Effectiveness of exosome mediated miR-126 and miR-146a delivery on cardiac tissue regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 390, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiklander, O.P.B.; Nordin, J.Z.; O’Loughlin, A.; Gustafsson, Y.; Corso, G.; Mäger, I.; Vader, P.; Lee, Y.; Sork, H.; Seow, Y.; et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 26316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianson, H.C.; Svensson, K.J.; van Kuppevelt, T.H.; Li, J.-P.; Belting, M. Cancer cell exosomes depend on cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans for their internalization and functional activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17380–17385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.-L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Ceder, S.; et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedillo-Servin, G.; Louro, A.F.; Gamelas, B.; Meliciano, A.; Zijl, A.; Alves, P.M.; Malda, J.; Serra, M.; Castilho, M. Microfiber-reinforced hydrogels prolong the release of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles to promote endothelial migration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2023, 155, 213692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.W.; Wang, L.L.; Zaman, S.; Gordon, J.; Arisi, M.F.; Venkataraman, C.M.; Chung, J.J.; Hung, G.; Gaffey, A.C.; Spruce, L.A.; et al. Sustained release of endothelial progenitor cell-derived extracellular vesicles from shear-thinning hydrogels improves angiogenesis and promotes function after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, C.J.; Li, R.R.; Yeung, T.; Mazlan, S.M.I.; Lai, R.C.; de Kleijn, D.P.V.; Lim, S.K.; Richards, A.M. Systemic Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Reduce Myocardial Infarct Size: Characterization With MRI in a Porcine Model. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 601990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, S.; Zhang, L.; Duan, L.; Wang, X.; Min, Y.; Yu, H. Extracellular vesicles derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promote angiogenesis in a rat myocardial infarction model. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 92, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Shen, H.; Shao, L.; Teng, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, Z.; Shen, Z. HIF-1α overexpression in mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes mediates cardioprotection in myocardial infarction by enhanced angiogenesis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Sun, L.; Zhao, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, W.; et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor facilitates the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes in acute myocardial infarction through upregulating miR-133a-3p. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, L.; Ma, T.; Liu, Z.; Gao, L. Exosomes secreted by endothelial cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells improve recovery from myocardial infarction in mice. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H.; Chen, H.; Deng, J.; Xiao, C.; Xu, M.; Shan, L.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Z. Exosomes secreted by FNDC5-BMMSCs protect myocardial infarction by anti-inflammation and macrophage polarization via NF-κB signaling pathway and Nrf2/HO-1 axis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Meng, Q.; Sun, J.; Shao, L.; Yu, Y.; Huang, H.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. MicroRNA-132, Delivered by Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes, Promote Angiogenesis in Myocardial Infarction. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 3290372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, M.R.; Ikeda, G.; Tada, Y.; Jung, J.; Vaskova, E.; Sierra, R.G.; Gati, C.; Goldstone, A.B.; von Bornstaedt, D.; Shukla, P.; et al. Exosomes From Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Cardiomyocytes Promote Autophagy for Myocardial Repair. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2020, 9, e014345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghua, W.; Zhijian, G.; Chahua, H.; Qiang, L.; Minxuan, X.; Luqiao, W.; Weifang, Z.; Peng, L.; Biming, Z.; Lingling, Y.; et al. Plasma exosomes induced by remote ischaemic preconditioning attenuate myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury by transferring miR-24. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Guo, D.; Liu, G.; Chen, G.; Hang, M.; Jin, M. Exosomes from MiR-126-Overexpressing Adscs Are Therapeutic in Relieving Acute Myocardial Ischaemic Injury. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Chang, S.; Xu, R.; Chen, L.; Song, X.; Wu, J.; Qian, J.; Zou, Y.; Ma, J. Hypoxia-challenged MSC-derived exosomes deliver miR-210 to attenuate post-infarction cardiac apoptosis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.-P.; Tian, T.; Wang, J.-Y.; He, J.-N.; Chen, T.; Pan, M.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.-X.; Qiu, X.-T.; Li, C.-C.; et al. Hypoxia-elicited mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes facilitates cardiac repair through miR-125b-mediated prevention of cell death in myocardial infarction. Theranostics 2018, 8, 6163–6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.P.; Boon, R.A. Exosomes and non-coding RNA, the healers of the heart? Cardiovasc. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Huang, P.; Chen, G.; Xiong, Y.; Gong, Z.; Wu, C.; Xu, J.; Jiang, W.; Li, X.; Tang, R.; et al. Atorvastatin-pretreated mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote cardiac repair after myocardial infarction via shifting macrophage polarization by targeting microRNA-139-3p/Stat1 pathway. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Tang, R.; Xu, J.; Jiang, W.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ning, Y.; Huang, P.; Xu, J.; Chen, G.; et al. Tongxinluo-pretreated mesenchymal stem cells facilitate cardiac repair via exosomal transfer of miR-146a-5p targeting IRAK1/NF-κB p65 pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, Y.; Li, C.; Qi, X.; Xu, R.; Dong, L.; Jiang, Y.; Gong, Q.; Wang, D.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, C.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles from NMN Preconditioned Mesenchymal Stem Cells Ameliorated Myocardial Infarction via miR-210-3p Promoted Angiogenesis. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2023, 19, 1051–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Jiao, Z.; Dong, N.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L. Localized injection of miRNA-21-enriched extracellular vesicles effectively restores cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Theranostics 2019, 9, 2346–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.; Hong, X.; Du, W.; Duan, R.; Jiang, J.; Ji, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Exosomes derived from mir-214-3p overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells promote myocardial repair. Biomater. Res. 2023, 27, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.-T.; Xiong, Y.-Y.; Ning, Y.; Tang, R.-J.; Xu, J.-Y.; Jiang, W.-Y.; Li, X.-S.; Zhang, L.-L.; Chen, C.; Pan, Q.; et al. Nicorandil-Pretreated Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Facilitate Cardiac Repair After Myocardial Infarction via Promoting Macrophage M2 Polarization by Targeting miR-125a-5p/TRAF6/IRF5 Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 2005–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciullo, A.; Biemmi, V.; Milano, G.; Bolis, S.; Cervio, E.; Fertig, E.T.; Gherghiceanu, M.; Moccetti, T.; Camici, G.G.; Vassalli, G.; et al. Exosomal Expression of CXCR4 Targets Cardioprotective Vesicles to Myocardial Infarction and Improves Outcome after Systemic Administration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Li, S.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Yan, D.; He, J. GATA-4 overexpressing BMSC-derived exosomes suppress H/R-induced cardiomyocyte ferroptosis. iScience 2024, 27, 110784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.-G.; Li, H.-R.; Han, J.-X.; Li, B.-B.; Yan, D.; Li, H.-Y.; Wang, P.; Luo, Y. GATA-4-expressing mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction via secreted exosomes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.-Y.; Kim, H.; Mun, D.; Yun, N.; Joung, B. Co-delivery of curcumin and miRNA-144-3p using heart-targeted extracellular vesicles enhances the therapeutic efficacy for myocardial infarction. J. Control. Release 2021, 331, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Xu, X.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, R.; Duan, S.; Zhang, L. Engineered nanovesicles mediated cardiomyocyte survival and neovascularization for the therapy of myocardial infarction. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2024, 243, 114135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Meng, Q.; Yu, Y.; Sun, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, T.; et al. Engineered Exosomes With Ischemic Myocardium-Targeting Peptide for Targeted Therapy in Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2018, 7, e008737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Su, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, Y.; Yu, Q.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y. Neutrophil-derived apoptotic body membranes-fused exosomes targeting treatment for myocardial infarction. Regen. Biomater. 2024, 12, rbae145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, G.; Zhu, D.; Huang, K.; Caranasos, T.G. Minimally invasive delivery of a hydrogel-based exosome patch to prevent heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2022, 169, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, F.; Xiong, W.; Song, S.; Yin, Y.; Hu, J.; Yang, K.; Yang, L.; et al. Mononuclear phagocyte system blockade using extracellular vesicles modified with CD47 on membrane surface for myocardial infarction reperfusion injury treatment. Biomaterials 2021, 275, 121000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.-X.; Xiao, Y.-Y.; Jiang, W.-J.; Yang, X.-Y.; Tao, H.; Mandukhail, S.R.; Qin, J.-F.; Pan, Q.-R.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Zhao, L.-X.; et al. Exosomes derived from induced cardiopulmonary progenitor cells alleviate acute lung injury in mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2024, 45, 1644–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wang, L.; Wei, Y.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Walcott, G.P.; Menasché, P.; Zhang, J. Exosomes secreted by hiPSC-derived cardiac cells improve recovery from myocardial infarction in swine. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaay1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-C.; Stice, J.P.; Chen, L.; Jung, J.S.; Gupta, S.; Wang, Y.; Baumgarten, G.; Trial, J.; Knowlton, A.A. Extracellular Heat Shock Protein 60, Cardiac Myocytes, and Apoptosis. Circ. Res. 2009, 105, 1186–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Z.A.; Kott, K.S.; Poe, A.J.; Kuo, T.; Chen, L.; Ferrara, K.W.; Knowlton, A.A. Cardiac myocyte exosomes: Stability, HSP60, and proteomics. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2013, 304, H954–H965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Hu, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Ma, H.; Huang, K.; Li, Z.; Su, T.; Vandergriff, A.; Tang, J.; et al. microRNA-21-5p dysregulation in exosomes derived from heart failure patients impairs regenerative potential. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 2237–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Z.; Wang, C. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal mir-21-5p inhibits YAP1 expression and improves outcomes in myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergriff, A.; Huang, K.; Shen, D.; Hu, S.; Hensley, M.T.; Caranasos, T.G.; Qian, L.; Cheng, K. Targeting regenerative exosomes to myocardial infarction using cardiac homing peptide. Theranostics 2018, 8, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; He, T.; Xing, J.; Zhou, Q.; Fan, L.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Wu, D.; Tian, Z.; Liu, B.; et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes protect cartilage damage and relieve knee osteoarthritis pain in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Ren, X.; Afizah, H.; Lai, R.C.; Lim, S.K.; Lee, E.H.; Hui, J.H.P.; Toh, W.S. Intra-Articular Injections of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes and Hyaluronic Acid Improve Structural and Mechanical Properties of Repaired Cartilage in a Rabbit Model. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2020, 36, 2215–2228.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharehchelou, B.; Mehrarya, M.; Sefidbakht, Y.; Uskoković, V.; Suri, F.; Arjmand, S.; Maghami, F.; Siadat, S.O.R.; Karima, S.; Vosough, M. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome and liposome hybrids as transfection nanocarriers of Cas9-GFP plasmid to HEK293T cells. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0315168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; Secchi, V.; Macchi, M.; Tripodi, L.; Trombetta, E.; Zambroni, D.; Padelli, F.; Mauri, M.; Molinaro, M.; Oddone, R.; et al. Magnetic-field-driven targeting of exosomes modulates immune and metabolic changes in dystrophic muscle. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 1532–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhu, D.; Cores, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Mei, X.; Cheng, X.; Su, T.; et al. Platelet membrane and stem cell exosome hybrids enhance cellular uptake and targeting to heart injury. Nano Today 2021, 39, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraszti, R.A.; Miller, R.; Stoppato, M.; Sere, Y.Y.; Coles, A.; Didiot, M.-C.; Wollacott, R.; Sapp, E.; Dubuke, M.L.; Li, X.; et al. Exosomes Produced from 3D Cultures of MSCs by Tangential Flow Filtration Show Higher Yield and Improved Activity. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 2838–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulpiano, C.; Salvador, W.; Franchi-Mendes, T.; Huang, M.-C.; Lin, Y.-H.; Lin, H.-T.; Rodrigues, C.A.V.; Fernandes-Platzgummer, A.; Cabral, J.M.S.; Monteiro, G.A.; et al. Continuous collection of human mesenchymal-stromal-cell-derived extracellular vesicles from a stirred tank reactor operated under xenogeneic-free conditions for therapeutic applications. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.; O’Driscoll, L.; Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W. MISEV2023: An updated guide to EV research and applications. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodi, Z.; Pelyhe, C.; Terezia Nagy, C.; Brenner, G.B.; Almasi, L.; Kittel, A.; Mancek-Keber, M.; Ferdinandy, P.; Buzas, E.I.; Giricz, Z. Isolation of High-Purity Extracellular Vesicles by the Combination of Iodixanol Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation and Bind-Elute Chromatography From Blood Plasma. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böing, A.N.; van der Pol, E.; Grootemaat, A.E.; Coumans, F.A.W.; Sturk, A.; Nieuwland, R. Single-step isolation of extracellular vesicles by size-exclusion chromatography. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 23430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busatto, S.; Vilanilam, G.; Ticer, T.; Lin, W.-L.; Dickson, D.W.; Shapiro, S.; Bergese, P.; Wolfram, J. Tangential Flow Filtration for Highly Efficient Concentration of Extracellular Vesicles from Large Volumes of Fluid. Cells 2018, 7, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Valero, A.; Monguió-Tortajada, M.; Carreras-Planella, L.; La Franquesa, M.; Beyer, K.; Borràs, F.E. Size-Exclusion Chromatography-based isolation minimally alters Extracellular Vesicles’ characteristics compared to precipitating agents. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ströhle, G.; Gan, J.; Li, H. Affinity-based isolation of extracellular vesicles and the effects on downstream molecular analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 7051–7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meggiolaro, A.; Moccia, V.; Brun, P.; Pierno, M.; Mistura, G.; Zappulli, V.; Ferraro, D. Microfluidic Strategies for Extracellular Vesicle Isolation: Towards Clinical Applications. Biosensors 2022, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Freitas, D.; Kim, H.S.; Fabijanic, K.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Martin, A.B.; Bojmar, L.; et al. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Wu, X. Exosomes produced from 3D cultures of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in a hollow-fiber bioreactor show improved osteochondral regeneration activity. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2019, 36, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takov, K.; Yellon, D.M.; Davidson, S.M. Comparison of small extracellular vesicles isolated from plasma by ultracentrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography: Yield, purity and functional potential. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1560809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, J.Z.; Lee, Y.; Vader, P.; Mäger, I.; Johansson, H.J.; Heusermann, W.; Wiklander, O.P.B.; Hällbrink, M.; Seow, Y.; Bultema, J.J.; et al. Ultrafiltration with size-exclusion liquid chromatography for high yield isolation of extracellular vesicles preserving intact biophysical and functional properties. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2015, 11, 879–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter-Ovanesyan, D.; Gilboa, T.; Budnik, B.; Nikitina, A.; Whiteman, S.; Lazarovits, R.; Trieu, W.; Kalish, D.; Church, G.M.; Walt, D.R. Improved isolation of extracellular vesicles by removal of both free proteins and lipoproteins. eLife 2023, 12, e86394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Greening, D.W.; Zhu, H.-J.; Takahashi, N.; Simpson, R.J. Extracellular vesicle isolation and characterization: Toward clinical application. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Bachman, H.; Ouyang, Y.; Huang, P.-H.; Sadovsky, Y.; Huang, T.J. Separating extracellular vesicles and lipoproteins via acoustofluidics. Lab A Chip 2019, 19, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Soder, R.; Abhyankar, S.; Home, T.; Pathak, H.; Shen, X.; Godwin, A.K.; Abdelhakim, H. Large-scale manufacturing of immunosuppressive extracellular vesicles for human clinical trials. Cytotherapy 2025, 27, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobin, J.; Muradia, G.; Mehic, J.; Westwood, C.; Couvrette, L.; Stalker, A.; Bigelow, S.; Luebbert, C.C.; Bissonnette, F.S.-D.; Johnston, M.J.W.; et al. Hollow-fiber bioreactor production of extracellular vesicles from human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells yields nanovesicles that mirrors the immuno-modulatory antigenic signature of the producer cell. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powsner, E.H.; Kronstadt, S.M.; Nikolov, K.; Aranda, A.; Jay, S.M. Mesenchymal stem cell extracellular vesicle vascularization bioactivity and production yield are responsive to cell culture substrate stiffness. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2025, 10, e10743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, S.G.; Clos-Sansalvador, M.; Sanroque-Muñoz, M.; Pan, L.; Franquesa, M. Functional and potency assays for mesenchymal stromal cell–extracellular vesicles in kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2024, 38, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Shiba, T.; Yoshida, T.; Bolidong, D.; Kato, K.; Sato, Y.; Mochizuki, M.; Seto, T.; Kawashiri, S.; Hanayama, R. Precise analysis of single small extracellular vesicles using flow cytometry. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tian, Y.; Xue, C.; Niu, Q.; Chen, C.; Yan, X. Analysis of extracellular vesicle DNA at the single-vesicle level by nano-flow cytometry. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizenko, R.R.; Brostoff, T.; Rojalin, T.; Koster, H.J.; Swindell, H.S.; Leiserowitz, G.S.; Wang, A.; Carney, R.P. Tetraspanins are unevenly distributed across single extracellular vesicles and bias sensitivity to multiplexed cancer biomarkers. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashique, S.; Anand, K. Radiolabelled Extracellular Vesicles as Imaging Modalities for Precise Targeted Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibanez, B.; Aletras, A.H.; Arai, A.E.; Arheden, H.; Bax, J.; Berry, C.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Croisille, P.; Dall’Armellina, E.; Dharmakumar, R.; et al. Cardiac MRI Endpoints in Myocardial Infarction Experimental and Clinical Trials: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Schmidt, K.F.; Farhoud, M.; Zi, T.; Jang, S.C.; Dooley, K.; Kentala, D.; Dobson, H.; Economides, K.; Williams, D.E. In vivo tracking of [89Zr]Zr-labeled engineered extracellular vesicles by PET reveals organ-specific biodistribution based upon the route of administration. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2022, 112–113, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikita, T.; Miyata, M.; Watanabe, R.; Oneyama, C. In vivo imaging of long-term accumulation of cancer-derived exosomes using a BRET-based reporter. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, A.C.; Mizurini, D.M.; Gomes, T.; Rochael, N.C.; Saraiva, E.M.; Dias, M.S.; Werneck, C.C.; Sielski, M.S.; Vicente, C.P.; Monteiro, R.Q. Tumor-Derived Exosomes Induce the Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps: Implications For The Establishment of Cancer-Associated Thrombosis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, V.H.; Rondon, A.M.R.; Gomes, T.; Monteiro, R.Q. Novel Aspects of Extracellular Vesicles as Mediators of Cancer-Associated Thrombosis. Cells 2019, 8, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ji, Y.; Chi, B.; Xiao, T.; Li, C.; Yan, X.; Xiong, X.; Mao, L.; Cai, D.; Zou, A.; et al. A 3D culture system improves the yield of MSCs-derived extracellular vesicles and enhances their therapeutic efficacy for heart repair. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, F.N.; Tertel, T.; Stambouli, O.; Wang, C.; Dittrich, R.; Staubach, S.; Börger, V.; Hermann, D.M.; Brandau, S.; Giebel, B. CD73 activity of mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicle preparations is detergent-resistant and does not correlate with immunomodulatory capabilities. Cytotherapy 2022, 25, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]