Abstract

Two series of tri(2-furyl)- and triphenylphosphine-gold(I) complexes, with pyridyl- and pyrimidine-thiolate ligands containing electron-donating (-CH3) and electron-withdrawing (-CF3) substituents were synthesized and investigated for cell viability inhibitions. Prior results indicate that several of the gold(I) complexes in these series have high antifungal properties. The observed link between antifungal and anticancer activity provided motivation to investigate their antiproliferative effects, reported here. The synthesized compounds from both series were characterized by 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry (MS), infrared and UV-Vis spectroscopy, and solution stability studies. In addition, an X-ray crystallographic study was conducted on one of the gold(I) complexes. Analyte solubilities in McCoy’s 5A cell media were evaluated by ICP-MS. Initial screening studies were conducted on the two series to evaluate cell viability using the SK-BR-3 cell line. All ten gold(I) complexes exhibited sub-µM cytotoxicity and the most potent representatives, one from each series, were selected for further evaluation in four additional cell lines. Half-maximal effective concentrations (EC50) were determined for the MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 malignant mammary cell lines as well as the two control cell lines, HEK293T and MCF10A, to probe for specificity. Results indicate significant selectivity towards inhibition of cancer cells compared to non-transformed for tri(2-furyl)- and triphenylphosphine-gold(I) complexes with the 3,5-dimethylpyrimidine thiolate ligand when dissolved in cell media. Additional studies including 1% DMSO as a solubilizing agent revealed its significant impact on cellular responses.

1. Introduction

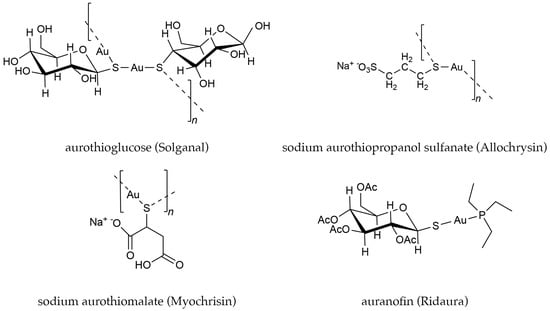

Gold(I) thiolate complexes have been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a chronic autoimmune disease that causes painful inflammation in the joints, since the early 1900s [1]. Early formulations of these drugs were water-soluble, injectable gold(I) salts, marketed under the common names Solganal, Allochrysin, and Myocrisin (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Examples of biologically active gold complexes.

In 1985, the phosphine gold(I) thiolate complex, auranofin ((2,3,4,6- tetra-O-acetyl-1- thio-β-D-glucopyranosato-S)(triethylphosphine) gold) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an oral medication for treating RA (Figure 1) [2,3]. The mechanism of the therapeutic effect of auranofin and other gold(I) drugs in the treatment of RA is still not completely understood. However, these drugs have been shown to have a wide range of medicinal effects, which has motivated numerous investigations into their possible treatment of other diseases, including cancer and parasitic diseases [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Recent efforts to repurpose auranofin for anticancer and antimicrobial properties have focused on mechanisms that induce apoptosis, including the inhibition of thioredoxin reductase [7,15,16,17,18,19]. Chemical proteomics analyses have confirmed the inhibitory effect of auranofin on TrxR and have also revealed effects on related pathways implicated in inflammation, glycogen metabolism, cellular differentiation, DNA replication, and selenoprotein synthesis [20,21]. A follow-up multifaceted proteome analysis to map redox-regulated cysteine residues revealed “massive changes in the redox state of the proteome” following a two-hour treatment with auranofin [22]. Interestingly, relative to the control, auranofin treatment resulted in a group of proteins that was oxidized and another group that was reduced. This intriguing result suggests that auranofin, and by extension, other phosphine gold(I) thiolate complexes, can participate in divergent but related pathways to increase reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in cell damage, and/or decrease ROS, which may ameliorate cell-damaging effects [4,23,24,25]. This complex response of the cell proteome to auranofin treatment makes mechanistic studies and the rational design of targeted gold-based drugs somewhat challenging, and suggests that a better understanding of these apparently divergent medicinal effects would be advantageous. These results also bring new insight into results from early clinical trials on treating RA with gold-based drugs, which showed that while 70–80% of patients experienced partial or complete remission of their arthritis, a significant number experienced side effects necessitating withdrawal from use [1].

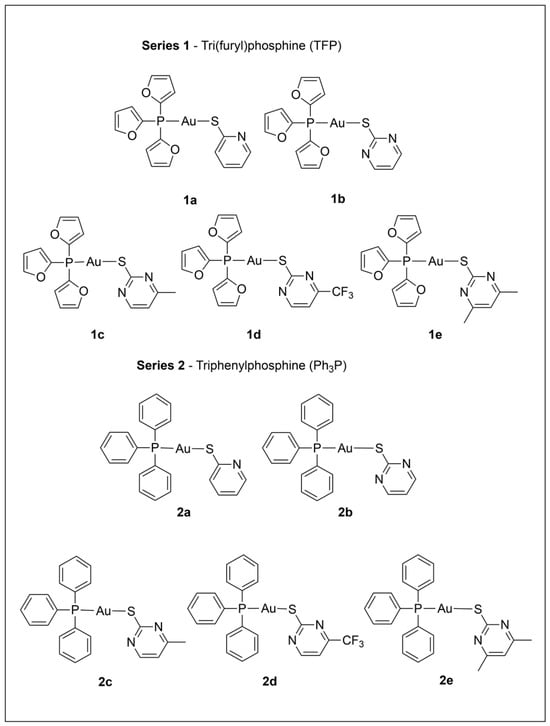

We recently investigated the antimicrobial properties of several of the tri(2-furyl)- and triphenylphosphine-gold(I) pyridyl- and pyrimidine-thiolate complexes depicted in Scheme 1, with 1b and 2a showing high antifungal activity (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration ≤ 1.25 µM) while not displaying cytotoxicity to mammalian cells at similar concentrations [26]. Several recent studies have noted a possible connection between antifungal and anticancer activity [27,28,29,30], and this provided additional motivation to investigate these gold complexes (Scheme 1) for their in vitro antiproliferative effects. Series 1 and Series 2 complexes in Scheme 1 contain tri(2-furyl) phosphine (TFP) and triphenylphosphine (PPh3), respectively. Relative to PPh3, TFP has a smaller cone angle and is a poorer π donor and a better π acceptor [31]. In addition, furyl rings vs. phenyl rings are expected to make the TFP ligand more polar. Each series includes the same set of thiolate ligands derived from pyridine and pyrimidine thiols, which are heterocyclic systems with a mobile hydrogen displaying tautomeric equilibria between the thiol and thione forms. These ligands, which contain sulfur and nitrogen donor atoms, are widely used in coordination chemistry for their versatile coordination behavior. Gold(I) is expected to preferentially bind to the sulfur [32], as is observed in Series 1 and 2. In addition, the nitrogen atoms in the ring can engage in hydrogen bonding [33,34], and have the potential to influence the hydrophilicity/lipophilicity balance of a metal complex, which is important for biological reactivity.

Scheme 1.

Numbering scheme and ligand abbreviations for the two series of gold(I) complexes studied. Abbreviations for thiolate ligands in the scheme caption: (a) Spy, (b) Spyrim, (c) SMepyrim, (d) SCF3pyrim, and (e) SMe2pyrim.

We recently investigated the antimicrobial properties of several of the tri(2-furyl)- and triphenylphosphine-gold(I) pyridyl- and pyrimidine-thiolate complexes depicted in Scheme 1, with 1b and 2a showing high antifungal activity (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration ≤ 1.25 µM) while not displaying cytotoxicity to mammalian cells at similar concentrations [26]. Several recent studies have noted a possible connection between antifungal and anticancer activity [27,28,29,30], and this provided additional motivation to investigate these gold complexes (Scheme 1) for their in vitro antiproliferative effects. Series 1 and Series 2 complexes in Scheme 1 contain tri(2-furyl) phosphine (TFP) and triphenylphosphine (PPh3), respectively. Relative to PPh3, TFP has a smaller cone angle and is a poorer π donor and a better π acceptor [31]. In addition, furyl rings vs. phenyl rings are expected to make the TFP ligand more polar. Each series includes the same set of thiolate ligands derived from pyridine and pyrimidine thiols, which are heterocyclic systems with a mobile hydrogen displaying tautomeric equilibria between the thiol and thione forms. These ligands, which contain sulfur and nitrogen donor atoms, are widely used in coordination chemistry for their versatile coordination behavior. Gold(I) is expected to preferentially bind to the sulfur [32], as is observed in Series 1 and 2. In addition, the nitrogen atoms in the ring can engage in hydrogen bonding [33,34], and have the potential to influence the hydrophilicity/lipophilicity balance of a metal complex, which is important for biological reactivity.

Herein, we report on the synthesis, characterization, and cell viability inhibitions of the phosphine gold(I) thiolate complexes shown in Scheme 1. The syntheses of 2a, 2b, 2d, and 2e were reported previously [35,36], and were included in this study to facilitate the comparison of two different phosphine ligands with an identical set of thiolate ligands. The structural characterization of these complexes is supported by NMR and IR spectroscopies, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), and X-ray crystallography data (for one member of Series 1). Moreover, we utilize inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to determine the accurate solubilities of these complexes in cell media. The study was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, we investigated the cytotoxic effects of Series 1 and 2, as well as auranofin and cisplatin controls, against the SK-BR-3 (ATCC HTB-30) breast cancer cell line. In the second phase, we identified a top candidate from each series and measured half-maximal effective concentrations (EC50) against the malignant mammary cell lines MCF7 (ATCC HTB-22) and MDA-MB-231 (ATCC HTB-26), as well as the mammary epithelial cell line MCF10A (ATCC CRL-10317) and the non-transformed fibroblast cell line HEK293T (ATCC CRL-11268). These four cell lines represent both hormone receptor-positive (MCF7) [37], and more aggressive triple-negative (MDA-MB-231) [38], breast cancer subtypes; moreover, MCF10A [39] and HEK293T [40] serve as non-malignant controls to evaluate the selectivity of the candidate gold compounds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

For syntheses of phosphine gold(I) thiolate complexes, reagent-grade chemicals, including acetonitrile, ether, ethyl acetate, methylene chloride, methanol, heptane, hexane, and pentane, were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratory Company (Tewksbury, MA, USA). Tri(2-furyl) phosphine, triphenylphosphine (99% pure), and triethylamine were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 2-Mercaptopyridine (98%), 2-mercaptopyrimidine (98%), and 2-mercapto-4-methylpyrimidine hydrochloride (99%) were purchased from Alfa Aesar/Thermo Fisher (Tewksbury, MA, USA); 2-mercapto-4-(trifluoromethyl) pyrimidine (95%) and 4, 6-dimethyl-2-mercaptopyrimidine (98%) were purchased from Matrix Scientific (Elgin, SC, USA). Tetrahydrothiophene gold(I) chloride (Au(tht)Cl) was prepared according to the literature [41]. Cisplatin was purchased from Strem Chemicals (Newburyport, MA, USA), and auranofin was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY, USA). Trace metal nitric acid (HNO3, 70% v/v) and trace metal hydrochloric acid (HCl, 36% v/v) for ICP-MS sample preparation were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) and Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), respectively. Nanopure water (18.2 MΩ) used for sample preparation was generated in-house using a Barnstead GenPure Pro Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) Water Purification System. The ICP-MS external and internal calibration standards were purchased from Inorganic Ventures (Christiansburg, VA, USA). For cell viability studies, all five cell lines (SK-BR-3, MCF7, MDA-MB-231, HEK293T, and MCF10A) and FBS were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). Media components included the following: DMEM from Corning (Corning, NY, USA), DME-F12 from Cytiva (Marlborough, MA, USA), fetal bovine serum from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA), horse serum from Cytiva (Marlborough, MA, USA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin from Gibco (Billings, MT, USA), 20 ng/mL EGF from EMD Millipore Corp (Burlington, MA, USA), 100 ng/mL chloera toxin from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), 0.01 mg/mL insulin from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and 500 ng/mL hydrocortisone from ACROS (Geel, Belgium). CellTiter Blue and Trypan Blue dyes were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Methanol (LC-MS grade) and acetic acid were also purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Sodium iodide calibrant was purchased from Waters (Milford, MA, USA). (Ph3P)AuCl and (TFP)AuCl [42] were prepared under N2 from equal molar mixtures of Au(tht)Cl and the respective phosphine in CH2Cl2 solution. The gold(I) products were isolated as powders by the addition of hexane; the formation of the desired products was confirmed by 1H, 31P{1H}, and 13C{1H} NMR spectroscopy.

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of Phosphine Gold(I) Thiolate Complexes

All the phosphine gold(I) thiolate complexes shown in Scheme 1 (1a–1e and 2a–2e) were prepared in a similar fashion. The simplified molecular input line entry (SMILE) notations for all ten gold compounds are listed in Table S1. Reactions were carried out under N2; isolation and recrystallization steps were conducted in the air. First, 0.54 mmol of thiol was dissolved in approximately 20 mL de-gassed CH2Cl2 at 0 °C, followed by the addition of NEt3 (90 µL, 0.65 mmol). The mixture was stirred until the solution became colorless and was transferred via cannula to a flask containing 0.54 mmol of (TFP)AuCl (for Series 1) or (Ph3P)AuCl (for Series 2) and stirred at room temperature (~23 °C) overnight. The reaction mixture was transferred to a separatory funnel, washed with 3 × 20 mL of water to remove triethylammonium chloride, and dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate. The solution was filtered and concentrated in vacuo. The addition of hexane precipitated the phosphine gold(I) thiolate complex. All complexes were recrystallized from CH2Cl2/heptane by slow evaporation of CH2Cl2. The tri(2-furyl) phosphine gold(I) thiolates (1a–1e) were obtained as pale-yellow crystals in 67–73% yield, and the triphenylphosphine gold(I) thiolates (2a–2e) were obtained as colorless crystals in 62–98% yield. Elemental analyses were determined by Galbraith Labs (Knoxville, TN, USA) (Table S2).

Melting points measured on a Capillary Melting Point Apparatus A388 from Thomas Hoover (Philadelphia, PA, USA), along with compound yields and spectral assignments, are available in Table S3.

NMR spectra were recorded on an Agilent/Varian Inova instrument (Santa Clara, CA, USA) and processed with MNova11 (Mestrelab Research, Santiago de Compostela, Spain); chemical shifts are reported in ppm. 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz) are referenced using the residual solvent peak of CDCl3 at 7.26 ppm. 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz) spectra are externally referenced to 85% H3PO4 at (0 ppm). 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz) spectra are referenced on the solvent, CDCl3 at 77.0 ppm (Figure S1). The same instrument was utilized for the collection of 1H and 31P NMR spectra to determine the stability of the complexes in DMSO-d6 over a 72 h time period (Figure S2).

The IR spectra were collected on solid samples using a Bruker ALPHA-P ATR spectrometer (Billerica, MA, USA) in the 4000–400 cm−1 wavenumber range (Figure S3).

2.3. X-Ray Crystallography

SC-XRD data were collected using a Bruker D8 QUEST ECO diffractometer (Madison, WI, USA) with a sealed tube source (Mo-Kα, λ = 0.71073 Å). Crystals of 1d were obtained from methylene chloride/heptane. A crystal was mounted on a dual-thickness MiTeGen Micro Loop (MiTeGen, Ithaca, NY, USA). No decomposition or degradation of the crystal was observed during data collection, which was conducted at room temperature. The resulting structure was solved by direct methods using the APEX 3 Crystallography Software Suite version 6 (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). Further refinements were made with the XL refinement package in Olex2-1.5 [43,44]. Disorder in the CF3 group was modeled by assigning one-half occupancy to each fluorine part. All hydrogen atoms were calculated by the software and finally refined [43,44,45]. Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center deposition number for 1d: 2184235 (Table S4).

2.4. ICP-MS

Analyses were carried out on Agilent ICP-MS 7900 (Santa Clara, CA, USA) to determine the solubility of the phosphine gold(I) thiolate complexes in McCoy’s 5A cell medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS). For solubility measurements, saturated solutions in McCoy’s 5A cell culture media (devoid of cells) for each complex were analyzed via ICP-MS. Concentrated hydrochloric and nitric acids were used to fully digest the saturated complex cell media solutions overnight at room temperature. The overnight digestion time was sufficient to fully dissolve all the gold in the solution, and no pressure- or microwave-assisted digestion was needed. Gold complexes were added to media individually in a microcentrifuge tube, sonicated for 60 min, and then shaken for 24 h to ensure each complex concentration surpassed its solubility limit; the presence of the undissolved complex as a visible pellet verified the saturation of the complex solution for ICP-MS analysis of the supernatant. Digestion of 500 µL aliquots of the saturated solution supernatant with 300 µL of HNO3 and 1000 µL of HCl was performed in 15 mL Eppendorf tubes overnight. The digested samples were properly diluted for analysis within the linear range of the ICP-MS. The Au standard (1002 ± 7 µg/mL) was diluted to produce an external calibration curve with ten concentrations from 1 to 10 ppb (ng/mL) (Figure S4), which was used to determine the concentration of Au in each solution and calculate the solubilities of each gold(I) complex in the cell culture media. All diluted digest samples, calibrants, continuing calibration verification samples (CCV), internal standards, and solvent blanks included 2.1% (v/v) HNO3 and 2.1% (v/v) HCl. All continuing calibration verification (CCV) data points were within 10% consistency throughout the entire ICP-MS data acquisition period, and hence no data points were rejected. The 50 ppb (ng/mL) Bi internal standard was used to correct for the drift in instrument response factor. Sample and calibration point intensities were solvent-blank-corrected after correcting for the internal standard. Each analyzed sample injection measured 197Au with seven 50-scan averages (0.5 s integration per scan). All internal standards and gold intensity (counts/s) relative standard deviations were within 2%, and no data points were rejected in the final ICP-MS analyses. Microsoft Excel (Version 2405) was used for ICP-MS data analysis and plotting.

2.5. LC-MS

Purities of 1e and 2e were determined with LC-MS and ESI-MS. To evaluate complex purities with LC-MS, each gold complex was dissolved in 18.2 MΩ water (to a final gold complex concentration of 0.1 µM), and 2 µL of each solution was injected onto a C18 trap and subsequent analytical columns (Waters ACQUITY UPLC M-Class HSS T3 C18, 100 µm × 150 mm, 100 Å pore size, 1.8 µm particle size). LC-MS mobile phase polarity was changed over time using a binary solvent system comprising Solvent A (18.2 MΩ H2O) and Solvent B (CH3CN). A 5 min isocratic trapping period (1% B) at a flow rate of 5 µL/min on the trap column was followed by a 45 min separation at an LC flow rate of 0.5 µL/min (Table S5). For the evaluation of stability, each complex was individually dissolved (99% 18.2 MΩ H2O: 1% CH3CN) to a final concentration of 0.5 µM and subjected to analysis after 72 h using the same LC-MS solvent composition and flow rates. Mass spectra were acquired using the Waters Synapt G-2 Traveling Wave Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Quadrupole-Time-of-Flight (Milford, MA, USA) system. All mass spectrometer settings were kept consistent with the ESI-MS section of this work. Data was collected in 1s scan times in the MSE mode using an ion mass-dependent energy ramp of 10V–40V. Waters MassLynx software V4.2 (Milford, MA, USA) was utilized for data acquisition/analysis and control of instrument parameters. Microsoft Excel (Version 2405) and Inkscape (Version 0.92.3) were used for data plotting and visualization (Figure S5).

2.6. ESI-MS

Purities of phosphine gold(I) thiolate complexes were confirmed utilizing ESI-MS in positive-ion mode. Mass spectrometry data were monitored in real-time to ensure proper and consistent generation of ESI-generated ions. For all ESI-MS experiments reported here, a spray solution consisting of 99% 18.2 MΩ H2O and 1% CH3CN was used to replicate the initial LC-MS mobile phase composition. Each Au complex was dissolved in 99% H2O and 1% CH3CN and immediately placed in a pulled glass capillary for purity analysis. Data was collected over 8 s with an average scan time of 1 s. The ESI mass spectra (Figure S6) at 1.5 kV ionization source potential showed no major contaminants or reaction side products. Minor ion molecule reaction and rearrangement products, consistent with previously reported ESI mass spectra of gold(I) thiolate complexes [46,47], were observed.

All ESI-MS analyses were performed in the sensitivity (V) mode. Before each MS data acquisition, external calibration curves were generated using twelve sodium iodide ion clusters (NaxIx−1 where 14 ≥ x ≥ 2, excluding x = 3), which yielded mass measurement accuracies of better than 5 parts-per-million (ppm). The source parameters were kept constant, using the following settings: source temperature 40 °C, sampling cone 40 °C, source offset 80 V, backing pressure ~3 mbar, source pressure ~5 × 10−3 mbar, desolvation temperature 40 °C, purge nitrogen gas flow 100 mL/h, desolvation nitrogen gas flow of 100 L/h, and sample spray voltage 1.5 kV. All other instrument parameters were kept at the automatically optimized default settings.

2.7. UV-Vis

Stabilities of gold(I) complexes in cell media with 1% (v/v) DMSO were studied with a Thermo Varioskan LUX Multimode Microplate Reader (Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with SkanIt software (version 6.1). UV-Vis analyses required higher concentrations of gold(I) complexes, necessitating the use of DMSO to increase the complexes’ solubilities. Each gold(I) complex was dissolved in 1% DMSO and cell media to a final concentration of 5 µM for UV-Vis analysis. Each solution was added to a 96-well plate in triplicate. Each data set also included background spectra from twelve additional wells serving as blanks, including three empty wells, three wells with an equal volume of DMSO, three wells containing cell media, and three wells containing cell media with 1% DMSO. The average signal from the empty wells was subtracted from the average signal measured for all other wells. UV-Vis absorbance spectra were acquired from 250 to 500 nm immediately after sample preparation and after 72 h (Figure S7).

2.8. Cell Viability Measurements

All cell lines were obtained from commercial sources and have been used in similar studies [48,49,50]. Initial 3-point dose–response experiments with the SK-BR-3 cell line were conducted to screen the two series of complexes. These studies were conducted in the absence of DMSO. All cell counts were made with Trypan blue dye and a hemocytometer (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA, USA). Exponentially growing cells were seeded in 96-well microplates by adding 20,000 cells (200 cells per µL) to each well and subsequently allowing 24 h for the cell population to adhere to the well walls before the introduction of the treatment. For each cell viability analysis, 24 h after seeding, the medium in each well was replaced with the prepared treatment solutions of each complex. The 96-well plates were then incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for an additional 72 h. Auranofin (0.5 µM) and cisplatin (5 µM) were used as positive controls.

After obtaining the initial screening cell viability measurements, 1e and 2e were selected for further study for more in-depth cell viability assessments on the MCF10A, HEK293T, MDA-MB-231, and MCF7 cell lines, with solutions made by direct dissolution of 1e and 2e in cell media across the target concentrations (viz., 0.01 µM, 0.03 µM, 0.06 µM, 0.1 µM, 0.33 µM, 0.66 µM, 0.75 µM, and 1 µM), along with a second analogous solution set incorporating a nominal volume (1% v/v) of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in cell media to study the effects of DMSO on cell viability experiments. These four solution sets (1e without DMSO, 1e with DMSO, 2e without DMSO, and 2e with DMSO) were employed in cell viability analyses over a 72 h incubation period. The observation period of 72 h is a conventional practice in evaluating gold(I) complexes and is attributed to the protracted presence of gold in the body post-treatment [51,52,53,54]. Three types of control wells were designated as follows: the blank control, which contained only cell media without any gold complex or cells added, the control population, which contained cells without any drug or DMSO, and the final control, which contained the same number of cells and the same percentage of DMSO (1% v/v) without any gold complex added. These controls were included to account for the natural absorbance of the cell media, measure the maximum fluorescence anticipated for the initial number of cells unperturbed, and account for the anticipated cell morbidity caused by the presence of DMSO. Auranofin was included in the cell viability assays to validate the observed cellular responses; cell viability measurements for the auranofin control were consistent with previously reported values [48,50]. CellTiter Blue was utilized for cell viability measurements, following the manufacturer’s recommended volumes and incubation times. After adding the CellTiter Blue and incubating the plate for four hours (37 °C, 5% CO2), fluorescent measurements were made of each well with respective excitation and emission wavelengths of 560 nm and 590 nm. The relative intensity of the control populations in each well was accounted for, and measurement values were adjusted accordingly. This process was completed in triplicate for each treatment regime. Determination of EC50 was derived from eight-point dose–response curves spanning concentrations from 0.01 µM to 1 µM for each of the four solution sets. Each dose response was fit to a sigmoidal function using GraphPad Prism 10.3.0 (San Diego, CA, USA), with all the treatments producing R2 values of ≥0.98 and relative standard deviations ≤ 10% between sample replicates (Figure S8).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization and Assessment of Purity for Series 1 and 2

In this study, we report on a small, targeted library consisting of the two series of gold(I) complexes shown in Scheme 1 that incorporate subtle variations in the steric and electronic properties of the phosphine and thiolate ligands. The complexes in Series 1 and Series 2 contain tri(2-furyl) phosphine (TFP) and triphenylphosphine (PPh3), respectively, and the same set of thiolate ligands: (a) Spy, (b) Spyrim, (c) SMepyrim, (d) SCF3pyrim, and (e) SMe2pyrim. The thiolate ligands, which are derived from pyridine and pyrimidine thiols, vary in terms of the number and placement of substituent groups on the ring (e.g., electron-donating -CH3 and electron-withdrawing -CF3 groups). The study design included assessing the solubility of all ten gold complexes in cell media and an initial screening for relative cytotoxicity against a single breast cancer cell line, SK-BR-3. This information was then used to identify one candidate in each series for further evaluation against two additional malignant mammary cell lines (MCF7 and MDA-B-231) as well as two control cell lines (a normal breast cell model, MCF10A, and human embryo kidney cells, HEK293T) to probe for specificity.

The gold(I) complexes were prepared by reaction of equimolar amounts of the deprotonated thiol, and (TFP)AuCl (Series 1) or (Ph3P)AuCl (Series 2). Prior to conducting cell viability experiments, all ten gold complexes were characterized by 1H, 13C{1H}, 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy (Figure S1), FTIR spectroscopy (Figure S3), ESI-MS (Figure S6), and thermal conductivity detector-based elemental analysis (Table S2). The S-pyridine and S-pyrimidine ligands typically display a variety of coordination modes with transition metals, but with gold(I), they most frequently behave as anionic ligands coordinated in a monodentate fashion through the sulfur donor atom. The FTIR spectra for Series 1 and Series 2 are consistent with this mode of coordination (Figure S3). The absence of ν(N-H) near 3150–3050 cm−1 and the absence of ν(S-H) (which generally appears as a broad, weak band between 2600 and 2400 cm−1) are consistent with deprotonation of the S-pyridine and S-pyrimidine molecules and formation of thiolate ligands coordinated to gold(I). The 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra (Figure S1) are also consistent with gold(I) being coordinated to one phosphine and one thiolate ligand. All complexes display a single sharp resonance in their 31P{1H} NMR spectra (Figure S1), with the TFP (in 1a–1e) and Ph3P (in 2a–2e) resonances appearing at −23.4 to −24.2 ppm and 38.1 to 38.3 ppm, respectively. The 31P{1H} NMR spectral resonances for Series 1 and 2 complexes are shifted several ppm downfield relative to (TFP)AuCl (−29 ppm) and (Ph3P)AuCl (31 ppm), respectively, consistent with the substitution of a chloride ligand by thiolate [35,55,56]. The purity of the complexes was established by elemental analyses (Table S2) and ESI-MS (Figure S6). Experimental values for the elemental analyses of C, H, and N were within 0.4–0.6% of their calculated values. The ESI mass spectra at 1.5 kV ionization source potential showed no major contaminants or reaction side products. Moreover, experimentally observed isotopic patterns and measured masses agreed with their respective theoretical values (Figure S6). Specifically, calculated mass measurement errors for all gold complexes were less than 5 ppm, in agreement with the elemental analysis results (Table S2).

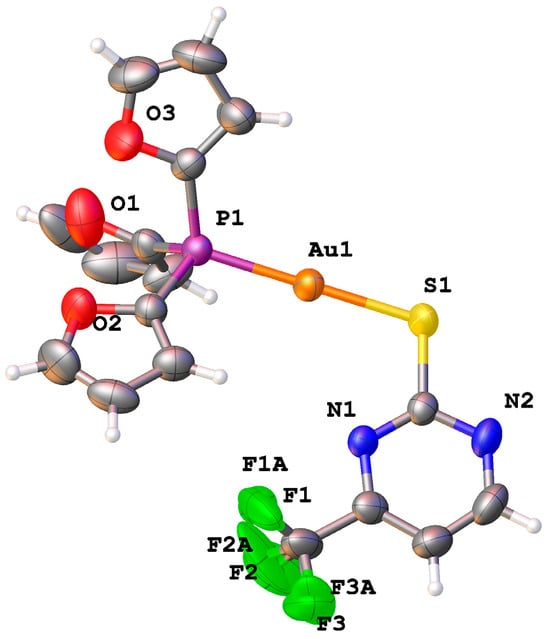

3.2. X-Ray Structure

Complex 1d was characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Figure 2 shows the molecular structure for 1d displayed as an Oak Ridge Thermal Ellipsoid Plot (ORTEP) diagram, and crystal data are provided in Table S4. The Au-P (2.2451(14) Å) and Au-S (2.2927(14) Å) bond distances and the P-Au-S angle (178.35(6)°) are typical for phosphine gold(I) thiolate complexes. The CF3 group exhibits positional disorder in the F atoms. The intramolecular Au-N distance of 3.226(4) Å is close to the sum of the Au-N van der Waals radii (3.21 Å); however, Au-N interactions do not appear to contribute significantly to the structural properties, given the linear geometry at gold.

Figure 2.

ORTEP diagram (50% thermal ellipsoids) for 1d (TFP)Au(SCF3pyrim). Color scheme: C (gray); N (blue); O (red); P (purple); S (yellow); F (green); Au (orange).

3.3. Solubility and Stability of Series 1 and 2 in Cell Media

The solubility of each complex in McCoy’s 5A cell medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS was determined using ICP-MS. The known gold–complex stoichiometry of 1:1 and quantitative determination of gold concentrations in media saturated with each complex were utilized to determine the solubility of each complex in separate experiments (Table 1). The ICP-MS calibration curve (Figure S4) indicated a high degree of linearity (e.g., R2 = 0.9995). Based on the replicate ICP-MS measurements and including error propagations, relative uncertainties for solubility values at the 95% confidence level (CL = 95%, n = 48) were less than 2% (Table 1). Solubilities for the examined gold(I) complexes ranged from ~1.07 µM (for 2b) to ~36.8 µM (for 1b); auranofin’s solubility in the cell culture medium at the 95% confidence level (95%) was 43.6 ± 0.5 µM. On average, gold complexes with the TFP ligand exhibited slightly greater solubility (average 14.8 µM) than the PPh3 complexes (average 4.6 µM), consistent with the greater degree of hydrophilicity for the furyl vs. phenyl rings.

Table 1.

Solubility limits for gold complexes and auranofin in McCoy’s 5A cell medium at the 95% confidence level, determined by quantification of gold in replicate ICP MS measurements.

Stability of the gold complexes in cell media over a 72 h time frame was assessed by UV-Vis spectroscopy. Since UV-Vis analyses require higher concentrations, 1% (v/v) DMSO was added to achieve 5 μM concentrations of the gold complexes. All UV-Vis absorbance spectra were acquired immediately after sample preparation and compared with corresponding data collected after 72 h. No significant changes were observed in the UV-Vis spectra during the 72 h period (Figure S7).

3.4. Phase 1: Cytotoxicity of Series 1 and 2 Against the SK-BR-3 Breast Cancer Cell Line

The initial cytotoxicity screening of Series 1 and 2 was made against the breast cancer cell line, SK-BR-3, at three concentrations (viz., 0.125, 0.25, and 0.5 µM). The cell viability measurements were acquired using a fluorescent assay (CellTiter Blue), and all cell viability results were normalized based on the fluorescence observed from the control samples. The results shown in Table 2 demonstrate that all 10 complexes show antiproliferative activity at 0.5 µM concentrations. The observed respective average cell viabilities against SK-BR-3 for Series 1 and 2 were 59 ± 5% and 49 ± 8%. Auranofin (0.5 µM) and cisplatin (5 µM) were included as positive controls against SK-BR-3, and these complexes exhibited cell viability reductions of 47.1 ± 1.3% and 49.9 ± 3.8%, respectively, consistent with the literature values [15,16]. Further, complexes 2b, 2d, and 2e showed cell viability reductions larger than 50% (viz., 100% − 48.5% ≅ 52.5%, 100% − 49.9% ≅ 50.1%, and 100% − 48.7% ≅ 52.3%, respectively) at the 0.5 µM concentration level.

Table 2.

Individual cell viability results for SK-BR-3 after incubation of 1a–1e and 2a–2e in McCoy’s 5A media for 72 h (0.5 µM). For comparison, auranofin (0.5 µM) and cisplatin (5 μM) results are also included in the last two rows. All cell viability values are reported at the 95% confidence level (for n = 15).

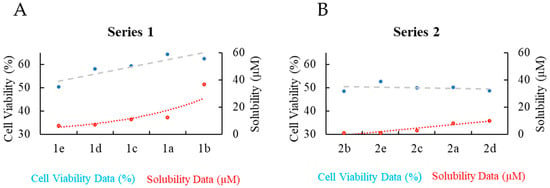

To examine the differences in activity between Series 1 and 2 in more detail, the cell viability and solubility data were plotted in the dual-axis charts shown in Figure 3. There is a wider range of cell viability for Series 1 (50.4 ± 1.9 to 64.4 ± 1.1%) than Series 2 (48.5 ± 1.7 to 51.9 ± 7.0%). For Series 1, there is a trend between solubility and cell viability, with the less soluble complexes showing higher cytotoxicity (Figure 3A). Series 2 is, on average, more cytotoxic and less soluble than Series 1, but there is little variation in either property within the series (Figure 3B). Solubility in aqueous solution is expected to be inversely correlated with lipophilicity [57,58], and the balance between lipophilicity and hydrophilicity plays an important role in the transport of molecules through biological membranes [59,60]. McKeage et al. investigated the correlation between lipophilicity and cytotoxicity for a series of cationic gold(I) complexes, and they found a parabolic dependence between lipophilicity (log Kw) and logarithmic IC50 values, where the activity reached a maximum at an intermediate value of log Kw. Moreover, there was a linear relationship between cellular uptake and logarithmic IC50 values. Additional studies have shown a parabolic relationship between antitumor activity and drug lipophilicity, with the highest activity occurring at an intermediate value of lipophilicity [59,61,62]. The data shown in Figure 3 suggest that differences in cytotoxicity between Series 1 and 2, and within Series 1, may be related to slight differences in cellular uptake due to the subtle influence of ligand substituents on the hydrophilic–lipophilic balance of the complexes. Based on these SK-BR-3 breast cancer cell viability results, complexes 1e and 2e (the closest analog of 1e in series 2) were selected for additional cell viability studies in phase 2.

Figure 3.

Dual-axis charts showing cell viability results for SK-BRK-3 (blue circles) and solubility in cell media (red circles) for (A) Series 1 and (B) Series 2; sorted by solubility. Dotted lines are trendlines.

3.5. Phase 2: Cytotoxicity and Selectivity of 1e and 2e for MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 Breast Cancer Cell Lines

Prior to conducting additional cell studies, the purity and stability of 1e and 2e were further evaluated with LC-MS and NMR spectroscopy. Based on the observed LC peaks (Figure S5) and direct infusion MS data (Figure S6), both complexes were >95% pure. LC-MS data confirmed the absence of impurities and the presence of expected ion-molecule reaction products within the parent molecules’ LC elution times. Hence, LC-MS results were consistent with the IR and NMR spectroscopy data, and other analytical characterizations (vide infra) in confirming the purity of 1e and 2e. Using an optimized solvent gradient (Table S5), ultra-performance LC (UPLC) ESI-MS analyses of 1e and 2e dissolved in 99% 18.2 MΩ H2O: 1% CH3CN to a final concentration of 0.5 µM (Figure S5) confirmed stability over 72 h, ≥95% purity, and correct chemical identities of the examined gold compounds. Finally, in addition to the UV-Vis analyses described above for the evaluation of stability of Series 1 and 2 in cell media with 1% (v/v) DMSO added, the stability of 1e and 2e in neat DMSO-d6 was evaluated by 1H and 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy, which confirmed the stability of the complexes over a 72 h testing period (Figure S2), i.e., no spectral changes were noted in any of the NMR spectra as a function of time.

In phase 2, cell viability assessments for 1e and 2e were conducted on four cell lines, including two mammary malignant cell lines (MCF7, MDA-MB-231), one mammary epithelial cell line (MCF10A), and one non-transformed fibroblast cell line (HEK293T). Two different solution sets were prepared for each cell viability assessment: one set with the direct dissolution of complexes in cell media across the target concentrations (0.01 μM to 1 μM) and another analogous solution set that included 1% v/v DMSO to enhance the solubility of 1e and 2e. These two sets of experimental conditions were used to evaluate the influence of DMSO on the cellular responses. Although DMSO is commonly employed to prepare treatment solutions of organic and inorganic compounds with low aqueous solubility, there is evidence in the recent literature that DMSO can influence the cell viability results [63,64,65,66,67,68]. Other studies have shown that impurities in DMSO may complicate reactivity studies involving metal ions [69]. Although the concentration of DMSO in many cell viability studies is typically no more than 1%, several studies suggest that concentrations greater than 0.3% may have detrimental effects. Other studies conclude that blank control experiments containing the same level of DMSO as the test solutions are necessary and sufficient to establish the effect of DMSO [49].

The results of EC50 studies against four cell lines, with direct dissolution of 1e and 2e in cell media and in the absence of DMSO, are shown in Table 3. The eight-point dose–response curves, spanning a concentration range of 0.01 µM to 1 µM, which were used for the determination of EC50, are shown in Figure S8A,C. EC50 values, derived from sigmoidal fits of the dose–response curves, range from 0.05 ± 0.01 µM for 2e against MDA-MB-231 to 0.31 ± 0.03 µM for 1e against MCF7. Further, dose–response data indicate that, regardless of the concentration level, treatments of non-transformed epithelial (MCF10A) and fibroblast cells (HEK293T) with 1e or 2e resulted in mostly unperturbed cell populations (cell viabilities greater than 80%). Thus, 1e and 2e exhibited a significant selectivity towards inhibition of the cancer cell lines as compared to non-transformed cells. Auranofin has been tested against the MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines in numerous studies, without DMSO or with low levels of DMSO, with IC50 values in the range of 0.6–1.5 µM and 0.47–1.0 µM for MCF7 and MDA-MB-231, respectively [50,70,71,72]. It is noteworthy that 1e and 2e appear to be more active than auranofin against these two breast cancer cell lines.

Table 3.

EC50 values for 1e and 2e dissolved in cell media; concentrations expressed in µM for each solution after 72 h.

3.6. Further Discussion on the Influence of 1% DMSO on the Cytotoxicity and Selectivity of 1e and 2e for MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 Breast Cancer Cell Lines

The second set of cytotoxicity studies on the same four cell lines was carried out for 1e and 2e dissolved in cell media containing 1% (v/v) DMSO. Control experiments on our cell populations treated with cell media containing 1% DMSO (i.e., without any gold complexes) establish that there is no significant reduction in cell viability for any of the four cell lines (≤10% cell viability reduction). Further, the gold(I) complexes in Series 1 and 2 are stable in cell media with 1% DMSO as well as in neat DMSO solutions, ruling out the possibility of 1e and 2e reacting with DMSO to form decomposition products.

The results of EC50 studies against the four cell lines in the presence of 1% DMSO and the gold complexes 1e and 2e (see Table 4) indicate significantly altered results. A comparison of the data in Table 3 and Table 4 suggests that 1e and 2e are more cytotoxic to MCF7 in the presence of 1% DMSO than in the absence of DMSO. The opposite is true for the MDA-MB-231 cell line, where 1e and 2e are more cytotoxic in the absence of DMSO. Beyzavi et al. reported cell viability studies (with 1% DMSO) on a related series of gold(I) thiolate complexes that included the diphenyl-2-pyridylphosphine ligand and similar thiolates to those in Series 1 and 2. In their studies, the gold complexes with the Spy and Spyrim ligands had an average IC50 concentration of 6.7 µM for the MCF-7 cell line following a 72 h treatment period [73]. In contrast, our results on a similar set of gold(I) complexes, 1e and 2e, demonstrate EC50 concentrations against the MCF7 cell line that are an order of magnitude lower after a 72 h treatment.

Table 4.

EC50 values for 1e and 2e dissolved in cell media and with 1% DMSO added; concentrations expressed in µM for each solution after 72 h.

Significantly, the results shown in Table 4 indicate considerable toxicity for 1e and 2e toward the noncancerous cell lines, MCF10A and HEK293T, in the presence of 1% DMSO. What might be responsible for this effect? It is interesting to note that DMSO can influence the fluidity and permeability of biological membranes [74,75,76]. In addition, studies have demonstrated that certain ovarian cancer cells (IGROV1), which are known to have greater membrane fluidity, are more sensitive to auranofin treatment [77]. Taken together, our data suggest that the presence of 1% DMSO in the cell media may alter the cell membranes in some way that increases the toxicity of 1e and 2e toward the non-transformed cell lines. These results provide a cautionary note that the combination of DMSO and active compounds may change their mechanisms of cytotoxicity.

4. Conclusions

Based on prior results that indicated that 1b and 2a show very high antifungal activity while not displaying cytotoxicity to mammalian cells at similar concentrations, ten phosphine gold(I) complexes with two different phosphine ligands (TFP and PPh3) and five different pyridine and pyrimidine thiolate ligands were synthesized and evaluated for antiproliferative activities. The purity and stability of the synthesized gold(I) complexes were determined with NMR and IR spectroscopies, elemental analysis, ESI-MS, and LC-MS. Complex 1d was also characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Their solubility in aqueous cell media was also determined.

The complexes with the SMe2pyrim ligand, 1e and 2e, exhibited high cytotoxicity against the SK-BR-3 cell line, and these two complexes were selected for additional evaluation against four cell lines. The results of EC50 studies in cell media with no added DMSO indicate significant selectivity towards inhibition of the two mammary malignant cell lines, MCF7 and MDA-MB-231, as compared to the two non-transformed cells, MCF10A and HEK293T. Further, the data indicate that, regardless of the concentration level, neither the 1e nor 2e complexes reduced cell viability below 80% in the treatments of the noncancerous mammary epithelial cell line (MCF10A) or the non-transformed fibroblast cell line (HEK293T). In parallel studies conducted with 1% DMSO, both 1e and 2e inhibited the proliferation of the cancerous and non-transformed cells with minimal differences.

The data presented in this study strongly suggest the need for incorporating dual cell viability experiments into future investigations involving gold complexes. Specifically, these experiments should encompass both DMSO-assisted and DMSO-free conditions during the solvation of complexes. Such a comprehensive approach will offer valuable insights into the underlying reasons for the observed impact of DMSO on cell viability results. Furthermore, this methodology will enable the identification and exclusion of complexes that exhibit inherent insolubility at target concentrations, thus refining the selection of candidates for future studies. This dual experimental design, comparing the effects of the complexes with and without DMSO, will contribute to the establishment of robust protocols for assessing the cytotoxic potential of gold complexes and enhance the reliability and reproducibility of results in this field. Thus, it is important for future studies to consider the solubility limits of potential drug candidates and carefully assess the influence of DMSO on the measured cell viability outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biom16010154/s1, Figure S1: 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectra for 1a–1e; 2a–2e in CDCl3; Figure S2: 1H, and 31P NMR 72-h spectra for 1e and 2e; Figure S3: Attenuated total reflectance (ATR)-FTIR spectra for 1a–1e; 2a–2e; Figure S4: Calibration curve for ICP-MS analyses of gold concentrations; Figure S5: UPLC-ESI-MS data for 1e and 2e; Figure S6: Positive-ion mode ESI-MS mass spectra for 1a–1e; 2a–2e; Figure S7: UV-Vis spectra for 1a–1e and 2a–2e; Figure S8: Eight-point dose-response curve for 1e, 1e with DMSO, 2e, and 2e with DMSO; Table S1: Simplified molecular input line entry (SMILE) for 1a–1e; 2a–2e; Table S2: Elemental analyis data for 1a–1e; 2a–2e; Table S3: Yields, melting points, and spectral assignments for 1a–1e; 2a–2e; Table S4: Crystal data and details of the structure determination of 1d; Table S5: Optimized LC gradient used for purity and stability LC MS of 1a–1e; 2a–2e. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

K.L.W.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, visualization, and writing. S.P.: investigation, methodology, and writing. D.S.: investigation and methodology. C.W.: investigation and methodology. S.M.: investigation. R.A.V.: investigation. B.Z.: investigation. A.A.L.A.: investigation. J.T.: conceptualization, funding, methodology. M.R.M.B.: conceptualization, funding, methodology, and writing. A.E.B.: conceptualization, funding, methodology, and writing. T.S.: conceptualization, funding, methodology, and writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Baylor University and the University of Maine, General Research Funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Abbreviations

Au(tht)Cl, tetrahydrothiophene gold(I) chloride; CCV, continuing calibration verification; CDCl3, deuterated chloroform; CL, confidence level; ESI-MS, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry; FBS, fetal bovine serum; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; FTIR, Fourier transform infrared; HCl, hydrochloric acid; HNO3, nitric acid; ICP-MS inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry; IR, infrared spectroscopy; LC, liquid chromatography; MS, mass spectrometry; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; ppb, parts per billion; PPh3, triphenylphosphine; RA, rheumatoid arthritis TFP, (tri(2-furyl) phosphine; TrxR, thioredoxin reductase.

References

- Healy, M.L.; Lim, K.K.T.; Travers, R. Jacques Forestier (1890–1978) and gold therapy. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 12, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. FDA Media 24 May 1985—Approval of Auranofin. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/177921/download (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Sutton, B.M.; McGusty, E.; Walz, D.T.; DiMartino, M.J. Oral gold. Antiarthritic properties of alkylphosphinegold coordination complexes. J. Med. Chem. 1972, 15, 1095–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, J.; Clauss, G.; Fontes, J.V.; Oliveira, L.S.; Abbehausen, C. Oxidative Stress Mechanism by Gold Compounds: A Close Look at Total ROS Increase and the Inhibition of Antioxidant Enzymes. Chem. Asian J. 2025, 20, e202400792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmert, C.; Gornitzka, H.; Deraeve, C.; Stigliani, J.L. Current state of the art of gold complexes as antileishmanial agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 528, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belza, J.; Trávníček, Z.; Vančo, J.; Čajan, M.; Hošek, J.; Dvořák, Z. Gold(I) N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes with 7-Azaindoles Demonstrates In Vitro Antiproliferative Effects on Ovarian Cancer Cells and Anti-inflammatory Activity. Organometallics 2024, 43, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.J.; Kim, I.Y.; Lee, D.M.; Park, Y.J.; Cho, M.-Y.; Jin, H.J.; Choi, K.S. Dual inhibition of thioredoxin reductase and proteasome is required for auranofin-induced paraptosis in breast cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangamani, S.; Mohammad, H.; Abushahba, M.F.; Sobreira, T.J.; Hedrick, V.E.; Paul, L.N.; Seleem, M.N. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of auranofin against multi-drug resistant bacterial pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22571–22584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Aggarwal, S.; Celaje, J.J.A.; Ihara, S.; Ang, J.; Eremin, D.B.; Land, K.M.; Wrischnik, L.A.; Zhang, L.; Fokin, V.V.; et al. Gold(I) Phosphine Derivatives with Improved Selectivity as Topically Active Drug Leads to Overcome 5-Nitroheterocyclic Drug Resistance in Trichomonas vaginalis. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 6608–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Ortiz, N.; Lopez-Gonzales, E.; Woods, B.; Stürup, S.; De Graaf, I.A.M.; Groothuis, G.M.M.; Casini, A. Ex vivo toxicological evaluation of experimental anticancer gold(i) complexes with lansoprazole-type ligands. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 8, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambini, V.; Tilio, M.; Maina, E.W.; Andreani, C.; Bartolacci, C.; Wang, J.; Iezzi, M.; Ferraro, S.; Ramadori, A.T.; Simon, O.C.; et al. In vitro and in vivo studies of gold(I) azolate/phosphane complexes for the treatment of basal like breast cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 155, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Ott, I. On the medicinal chemistry of gold complexes as anticancer drugs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 1670–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galassi, R.; Luciani, L.; Wang, J.; Vincenzetti, S.; Cui, L.; Amici, A.; Pucciarelli, S.; Marchini, C. Breast Cancer Treatment: The Case of Gold(I)-Based Compounds as a Promising Class of Bioactive Molecules. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landini, I.; Massai, L.; Cirri, D.; Gamberi, T.; Paoli, P.; Messori, L.; Mini, E.; Nobili, S. Structure-activity relationships in a series of auranofin analogues showing remarkable antiproliferative properties. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 208, 111079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamberi, T.; Chiappetta, G.; Fiaschi, T.; Modesti, A.; Sorbi, F.; Magherini, F. Upgrade of an Old Drug: Auranofin in Innovative Cancer Therapies to Overcome Drug Resistance and to Increase Drug Effectiveness. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 42, 1111–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roder, C.; Thomson, M.J. Auranofin: Repurposing an Old Drug for a Golden New Age. Drugs RD 2015, 15, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromer, S.; Arscott, L.; Williams, C.J.; Schirmer, R.; Becker, K. Human placenta thioredoxin reductase—Isolation of the selenoenzyme, steady state kinetics, and inhibition by therapeutic gold compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 20096–20101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Selvaraju, K.; Saei, A.A.; D’Arcy, P.; Zubarev, R.A.; Arnér, E.S.; Linder, S. Repurposing of auranofin: Thioredoxin reductase remains a primary target of the drug. Biochimie 2019, 162, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saei, A.A.; Gullberg, H.; Sabatier, P.; Beusch, C.M.; Johansson, K.; Lundgren, B.; Arvidsson, P.I.; Arner, E.S.J.; Zubarev, R.A. Comprehensive chemical proteomics for target deconvolution of the redox active drug auranofin. Redox Biol. 2020, 32, 101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P.; Beusch, C.M.; Gencheva, R.; Cheng, Q.; Zubarev, R.; Arner, E.S.J. Comprehensive chemical proteomics analyses reveal that the new TRi-1 and TRi-2 compounds are more specific thioredoxin reductase 1 inhibitors than auranofin. Redox Biol. 2021, 48, 102184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saei, A.A.; Lundin, A.; Lyu, H.; Gharibi, H.; Luo, H.Q.; Teppo, J.; Zhang, X.P.; Gaetani, M.; Vegvari, A.; Holmdahl, R.; et al. Multifaceted Proteome Analysis at Solubility, Redox, and Expression Dimensions for Target Identification. Adv. Sci. 2024, 15, 2401502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.Y.; Park, S.H.; Park, W.H. Anti-Cancer Effects of Auranofin in Human Lung Cancer Cells by Increasing Intracellular ROS Levels and Depleting GSH Levels. Molecules 2022, 27, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatem, E.; El Banna, N.; Heneman-Masurel, A.; Baïlle, D.; Vernis, L.; Riquier, S.; Golinelli-Cohen, M.-P.; Guittet, O.; Vallières, C.; Camadro, J.-M.; et al. Novel Insights into Redox-Based Mechanisms for Auranofin-Induced Rapid Cancer Cell Death. Cancers 2022, 14, 4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Bouzakoura, S.; de Mey, S.; Jiang, H.; Law, K.; Dufait, I.; Corbet, C.; Verovski, V.; Gevaert, T.; Feron, O.; et al. Auranofin radiosensitizes tumor cells through targeting thioredoxin reductase and resulting overproduction of reactive oxygen species. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 35728–35742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frei, A.; Elliott, A.G.; Kan, A.; Dinh, H.; Braese, S.; Bruce, A.E.; Bruce, M.R.; Chen, F.; Humaidy, D.; Jung, N.; et al. Metal Complexes as Antifungals?—From a Crowd-Sourced Compound Library to First In Vivo Experiments. JACS Au 2022, 2, 2277–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, N.; Erofeev, A.; Timoshenko, R.; Vaneev, A.; Garanina, A.; Salikhov, S.; Grammatikova, N.; Levshin, I.; Korchev, Y.; Gorelkin, P. Investigation of the Antifungal and Anticancer Effects of the Novel Synthesized Thiazolidinedione by Ion-Conductance Microscopy. Cells 2023, 12, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, N.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, X.; Zhu, Q. Repurposing antifungal drugs for cancer therapy. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 48, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadavakollu, S.; Stailey, C.; Kunapareddy, C.S.; White, S. Clotrimazole as a Cancer Drug: A Short Review. Med. Chem. 2014, 4, 722–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, M.; Konarzewska, P.; Roberge, J.Y.; Han, G.-S.; Wang, Y.; Carman, G.M.; Xue, C. The Anticancer Drug Bleomycin Shows Potent Antifungal Activity by Altering Phospholipid Biosynthesis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00862-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, N.G.; Keay, B.A. 2-Furyl Phosphines as Ligands for Transition-Metal-Mediated Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 997–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrián-Blasco, E.; Gascón, S.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Laguna, M.; Cerrada, E. Novel Gold(I) Thiolate Derivatives Synergistic with 5-Fluorouracil as Potential Selective Anticancer Agents in Colon Cancer. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 8562–8579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Mansour, M.A.; Lachicotte, R.J.; Gysling, H.J.; Eisenberg, R. A Gold(I) Mononuclear Complex and Its Association into Binuclear and Cluster Compounds by Hydrogen Bonding or Metal Ion Coordination. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 5520–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onaka, S.; Yaguchi, M.; Yamauchi, R.; Ozeki, T.; Ito, M.; Sunahara, T.; Sugiura, Y.; Shiotsuka, M.; Nunokawa, K.; Horibe, M.; et al. The effect of carbon chain length of the diphosphine ligand on the aurophilic interaction. Synthesis and X-ray structural study for a series of Au(I) compounds with Ph2P–R–PPh2 and S-(CH2)n-py ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 690, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, P.D.; Tiekink, E.R.T. Triorganophosphinegold(I) complexes of pyridine-2-thionate and pyrimidine-2-thionate. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1993, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz Lang, E.; Fernandes, R.M., Jr.; Lemos, S.S.; Schulz Lang, L.; Burrow, R.A. (4,6-Dimethylpyrimidine-2-thiolato)(triphenylphosphine)gold(I). Acta Crystallogr. 2002, 58, m469–m470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.; Santell, R.; Haslam, S.; Helferich, W. Estrogenic effects of genistein on the growth of estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 3833–3838. [Google Scholar]

- Pratelli, G.; Carlisi, D.; Di Liberto, D.; Notaro, A.; Giuliano, M.; D’Anneo, A.; Lauricella, M.; Emanuele, S.; Calvaruso, G.; De Blasio, A. MCL1 Inhibition Overcomes the Aggressiveness Features of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Han, B.; Yu, Y.; Yao, W.; Bose, S.; Karlan, B.Y.; Giuliano, A.E.; Cui, X. Evaluation of MCF10A as a Reliable Model for Normal Human Mammary Epithelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Khoshbakht, T.; Hussen, B.M.; Jamal, H.H.; Taheri, M.; Hajiesmaeili, M. A Comprehensive Review on Function of miR-15b-5p in Malignant and Non-Malignant Disorders. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 870996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uson, R.; Laguna, A.; Laguna, M.; Briggs, D.A.; Murray, H.H.; Fackler, J.P., Jr. (Tetrahydrothiophene)Gold(I) or Gold(III) Complexes. Inorg. Synth. 1989, 26, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.E.; Sykora, R.E.; Assefa, Z. Synthesis, X-ray crystallography, and photoluminescence studies of four coordinate gold(I) complexes with the weak Lewis base tri-2-furyl phosphine ligand. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2013, 406, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourhis, L.J.; Dolomanov, O.V.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.; Puschmann, H. The anatomy of a comprehensive constrained, restrained refinement program for the modern computing environment—Olex2 dissected. Acta Crystallogr. A Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazimi, S.G.T.; Iqbal, M.S.; Mulligan, C.C.; Frank Shaw, C.; Iram, F.; Stelmack, A.R.; Campbell, I.S. Ligand Exchange/Scrambling Study of Gold(I)-Phosphine Complexes in the Solid Phase by DESI-MS Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 30, 2289–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiji, W.; Takayuki, K.; Nobuko, K.; Motohiro, S.; Masami, N.; Yasushi, K.; Shozo, Y. Aggregation through the Quadrupole Interactions of Gold(I) Complex with Triphenylphosphine and Pentafluorobenzenethiolate. Chem. Lett. 2003, 32, 1070–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curado, N.; Dewaele-Le Roi, G.; Poty, S.; Lewis, J.S.; Contel, M. Trastuzumab gold-conjugates: Synthetic approach and in vitro evaluation of anticancer activities in breast cancer cell lines. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 1394–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langsjoen, R.M.; Auguste, A.J.; Rossi, S.L.; Roundy, C.M.; Penate, H.N.; Kastis, M.; Schnizlein, M.K.; Le, K.C.; Haller, S.L.; Chen, R.; et al. Host oxidative folding pathways offer novel anti-chikungunya virus drug targets with broad spectrum potential. Antivir. Res. 2017, 143, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.S.; Shin, S.; An, H.G.; Kwon, T.U.; Baek, H.S.; Kwon, Y.J.; Chun, Y.J. Synergistic Induction of Apoptosis by the Combination of an Axl Inhibitor and Auranofin in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Biomol. Ther. 2020, 28, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, B.R.; Granda, J.L.; Freyberg, R.H. Gold metabolism in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with gold compounds—Reinvestigated. Arthritis Rheum. 1972, 15, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyberg, R.H.; Block, W.D.; Levey, S. Metabolism, toxicity and manner of action of gold compounds used in the treatment of arthritis. I. Human plasma and synovial fluid concentration and urinary excretion of gold during and following treatment with gold sodium thiomalate, gold sodium thiosulfate, and colloidal gold sulfide. J. Clin. Investig. 1941, 20, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, N.L. Metabolism and distribution of gold compounds. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 1979, 5, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Graham, G.G.; Champion, G.D.; Ziegler, J.B. The cellular metabolism and effects of gold complexes. Met. Based Drugs 1994, 1, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanaswamy, R.; Young, M.A.; Parkhurst, E.; Ouellette, M.; Kerr, M.E.; Ho, D.M.; Elder, R.C.; Bruce, A.E.; Bruce, M.R.M. Synthesis, Structure, and Electronic Spectroscopy of Neutral, Dinuclear Gold(I) Complexes. Gold(I)-Gold(I) Interactions in Solution and in the Solid State. Inorg. Chem. 1993, 32, 2506–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Pascariu, A.; Höcher, T.; Siehl, H.-U.; Berger, S. Electronic Properties of Furyl Substituents at Phosphorus and Their Influence on 31P NMR Chemical Shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8434–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.P.; Young, R.J. Getting physical in drug discovery: A contemporary perspective on solubility and hydrophobicity. Drug Discov. Today 2010, 15, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, C.; Ooi, K.; Tiekink, E. Gold-Based Medicine: A Paradigm Shift in Anti-Cancer Therapy? Molecules 2018, 23, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeage, M.J.; Berners-Price, S.J.; Galettis, P.; Bowen, R.J.; Brouwer, W.; Ding, L.; Zhuang, L.; Baguley, B.C. Role of lipophilicity in determining cellular uptake and antitumour activity of gold phosphine complexes. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2000, 46, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaian, R.; Mot, A.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu, R.; Ionut, I.; Stana, A.; Oniga, O.; Nastasa, C.; Benedec, D.; Tiperciuc, B. Study of the Relationships between the Structure, Lipophilicity and Biological Activity of Some Thiazolyl-carbonyl-thiosemicarbazides and Thiazolyl-azoles. Molecules 2015, 20, 22188–22201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansch, C.; Steward, A.; Anderson, S.; Bentley, D. Prabolic Dependence of Drug Action upon Lipophilic Character as revealed by a Study of Hypnotics. J. Med. Chem. 1968, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, C.; Kunz, P.C.; Kassack, M.U.; Hamacher, A.; Bohler, P.; Watjen, W.; Ott, I.; Rubbiani, R.; Spingler, B. Gold(I) complexes of water-soluble diphos-type ligands: Synthesis, anticancer activity, apoptosis and thioredoxin reductase inhibition. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 9212–9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Villagrán, M.; Paulus, L.; Leger, D.Y.; Therrien, B.; Liagre, B. Dimethyl Sulfoxide: A Bio-Friendly or Bio-Hazard Chemical? The Effect of DMSO in Human Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes. Molecules 2022, 27, 4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.; Cetto, A.; Campbell, M.; Scoggins, S.; Stultz, L.; Hanson, P. DMSO reduces the cytotoxicity of anticancer ruthenium complex KP1019 in yeast. Micropubl. Biol. 2021, 2021, 10–17912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Abreu Costa, L.; Henrique Fernandes Ottoni, M.; Dos Santos, M.G.; Meireles, A.B.; Gomes de Almeida, V.; De Fátima Pereira, W.; Alves de Avelar-Freitas, B.; Eustáquio Alvim Brito-Melo, G. Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) Decreases Cell Proliferation and TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2 Cytokines Production in Cultures of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes. Molecules 2017, 22, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanslick, J.L.; Lau, K.; Noguchi, K.K.; Olney, J.W.; Zorumski, C.F.; Mennerick, S.; Farber, N.B. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) produces widespread apoptosis in the developing central nervous system. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, E.A.; Demir, S.; Aliyazicioglu, Y. In vitro Cytotoxic Effect of Ethanol and Dimethyl Sulfoxide on Various Human Cell Lines. KSU Tarim Doga Derg. 2020, 23, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangweni, N.F.; Dludla, P.V.; Chellan, N.; Mabasa, L.; Sharma, J.R.; Johnson, R. The Implication of Low Dose Dimethyl Sulfoxide on Mitochondrial Function and Oxidative Damage in Cultured Cardiac and Cancer Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garusinghe, G.S.P.; Bessey, S.M.; Boyd, C.; Aghamoosa, M.; Frederick, B.; Bruce, M.R.M.; Bruce, A.E. Identification of dimethyl sulfide in dimethyl sulfoxide and implications for metal-thiolate disulfide exchange reactions. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 40603–40606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Moles, M.; Olmos, M.E.; López-de-Luzuriaga, J.M.; Ott, I.; Gimeno, M.C. A dual approach to cancer treatment: Gold(I) terpyridine derivatives as DNA binders and inhibitors of mammalian thioredoxin reductase. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 4802–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Enríquez, S.; Robledo-Cadena, D.X.; Pacheco-Velázquez, S.C.; Vargas-Navarro, J.L.; Padilla-Flores, J.A.; Kaambre, T.; Moreno-Sánchez, R. Repurposing auranofin and meclofenamic acid as energy-metabolism inhibitors and anti-cancer drugs. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.J.; Kwon, Y.J.; Baek, H.S.; Cho, E.; Kwon, T.U.; Chun, Y.J. Combination treatment with auranofin and nutlin-3a induces synergistic cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells. J. Toxicol. Env. Health Part A 2019, 82, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereidoonnezhad, M.; Ahmadi Mirsadeghi, H.; Abedanzadeh, S.; Yazdani, A.; Alamdarlou, A.; Babaghasabha, M.; Almansaf, Z.; Faghih, Z.; McConnell, Z.; Shahsavari, H.R.; et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of thiolate gold(i) complexes as thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) and glutathione reductase (GR) inhibitors. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 13173–13182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, M.; Matsuzaki, T.; Ozeki, N.; Katano, H.; Koga, H.; Takebe, T.; Yoshikawa, H.Y.; Sekiya, I. Cell membrane fluidity and ROS resistance define DMSO tolerance of cryopreserved synovial MSCs and HUVECs. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gironi, B.; Kahveci, Z.; McGill, B.; Lechner, B.-D.; Pagliara, S.; Metz, J.; Morresi, A.; Palombo, F.; Sassi, P.; Petrov, P.G. Effect of DMSO on the Mechanical and Structural Properties of Model and Biological Membranes. Biophys. J. 2020, 119, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Truong, K.D. Comparative cytotoxic effects of methanol, ethanol and DMSO on human cancer cell lines. Biomed. Res. Ther. 2020, 7, 3855–3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oommen, D.; Dodd, N.J.F.; Yiannakis, D.; Moyeed, R.; Jha, A.N. Linking genotoxicity and cytotoxicity with membrane fluidity: A comparative study in ovarian cancer cell lines following exposure to auranofin. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2016, 809, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.