Abstract

Dysregulated lipid metabolism constitutes the fundamental etiology underlying the global burden of obesity and its associated metabolic disorders. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant reversible chemical modification on messenger RNA and influences virtually every aspect of RNA metabolism. Recent studies demonstrate that m6A mediates regulatory networks governing lipid metabolism and contributes to the pathogenesis of multiple metabolic diseases. However, the precise roles of m6A in lipid metabolism and related metabolic disorders remain incompletely understood. This review positions m6A modification as a central epigenetic switch that governs lipid homeostasis. We first summarize the molecular components of the dynamic m6A regulatory machinery and delineate the mechanisms by which it controls key lipid metabolic processes, with an emphasis on adipogenesis, thermogenesis and lipolysis. Building on this, we further discuss how dysregulated m6A acts as a shared upstream driver linking obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), and insulin resistance through tissue-specific and inter-organ communication mechanisms. We also evaluate the potential of targeting m6A regulators as therapeutic strategies for precision intervention in metabolic diseases. Ultimately, deciphering the complex interplay between m6A modification and lipid homeostasis offers a promising frontier for the development of epitranscriptome-targeted precision medicine against obesity and its associated metabolic disorders.

1. Introduction

Dysregulated lipid metabolism drives major metabolic disorders, with obesity and related pathologies—such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), and cardiovascular disease—representing a primary global health challenge [1,2,3]. As adipose tissue (AT) functions as a vital energy reservoir and endocrine signaling hub, its normal development, differentiation, and functionality are essential for the maintenance of system-wide metabolic homeostasis [4,5,6,7]. Therefore, a detailed understanding of the molecular machinery governing lipid metabolism is essential for developing effective disease prevention strategies and therapeutics.

Traditional research on metabolic diseases has largely focused on genetic predispositions and environmental influences, which exert their effects primarily through classical epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modifications [8]. However, the discovery of the epitranscriptome—representing a dynamic and reversible regulatory layer at the RNA level—has heralded a new era in molecular biology [9,10]. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is by far the most abundant and best-characterized internal eukaryotic mRNA modification [11]. This modification is not an indelible tag; rather, it is dynamically “written” by methyltransferases (e.g., METTL3, METTL14), “erased” by demethylases (e.g., FTO, ALKBH5), and recognized by a suite of binding proteins (e.g., YTHDF1-3, YTHDC1-2, IGF2BP1-3). This interplay determines the fate of target transcripts by modifying splicing, nuclear export, stability, and translation efficiency [12]. The seminal discovery that the fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene encodes an m6A demethylase provided the first direct link between epitranscriptomics and the pathophysiology of energy metabolism and obesity, igniting immense interest in the field [13]. More recent research has revealed that m6A modification is deeply involved in numerous processes such as lipolysis, thermoregulation, and adipocyte differentiation. Furthermore, it is intricately linked to the pathogenesis of obesity as well as other metabolic diseases such as steatotic liver disease [14,15,16]. Crucially, this regulatory system functions as a pivotal “metabolic rheostat” capable of sensing cellular energy status and modulating metabolic responses. By controlling the fate of key metabolic gene transcripts, it reprograms cellular metabolic pathways, thereby establishing a sophisticated feedback loop [14,17].

This review aims to comprehensively explore the pleiotropic roles of m6A RNA modification in lipid metabolism and related metabolic disorders. We first summarize the molecular components and dynamic regulatory mechanisms of the m6A machinery, followed by an in-depth analysis of its regulatory networks in key metabolic processes, including adipogenesis, AT browning, and thermogenesis. On this basis, we further discuss how the dysregulation of m6A acts as a convergent pathophysiological mechanism driving the development of obesity, MASLD, and insulin resistance. Finally, we discuss the therapeutic potential of targeting m6A regulators, along with current challenges in both research and clinical applications.

2. Molecular Mechanism of m6A Modification

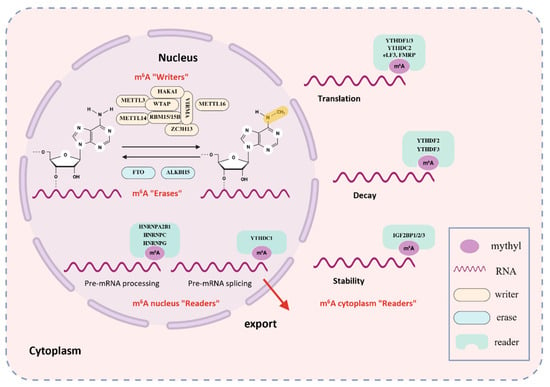

The m6A modification is predominantly found within a conserved consensus sequence, RRACH (where R = G or A; H = A, C, or U), and is enriched near stop codons and in 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR) of mRNA transcripts [18]. Its biological functions are mediated by a sophisticated molecular network comprising three key classes of proteins: “writers,” “erasers,” and “readers.” These three components work synergistically to dynamically regulate m6A modification, thereby influencing mRNA stability [19,20], splicing [21], translation [22,23], and degradation [24]. Consequently, m6A modification regulates the RNA fate, thereby affecting cellular functions and physiological processes [25] (As shown in Figure 1). While the majority of research has focused on mRNA, emerging evidence reveals that m6A modification also occurs on a wide array of other RNA species, including rRNA, snRNA, miRNA, lncRNA, and circRNA [26]. This broad involvement indicates that m6A plays a widespread role in cellular regulation, including the control of intricate metabolic networks. These findings open new perspectives for understanding how m6A contributes to metabolic homeostasis and the onset and disease progression.

Figure 1.

The Dynamic Modification Mechanism of m6A. m6A methylation is catalyzed by a multi-protein “writer” complex, primarily composed of METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, RBM15, VIRMA, and ZC3H13. METTL16 can also install m6A marks in specific contexts. These marks are removed by “erasers”, chiefly the demethylases FTO and ALKBH5. m6A sites on RNA are recognized by diverse “reader” proteins-including YTHDF1/2/3, YTHDC1/2, HNRNPA2B1/C, and IGF2BP1/2/3—which bind methylated transcripts and modulate their fate by affecting splicing, stability, translation, and degradation.

2.1. m6A Writers

The deposition of m6A is catalyzed by a multi-subunit methyltransferase complex (MTC) that is predominantly located in the nucleus. The catalytic core of this complex is a stable heterodimer composed of the core subunits Methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) and Methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14). METTL3 serves as the primary catalytic subunit responsible for transferring methyl groups from S-adenosylmethionine, while METTL14 functions as an RNA-binding scaffold that enhances the complex’s affinity for substrate RNA and activates METTL3 via allosteric regulation [27]. Additionally, m6A METTL-associated complexes (MACOMs) involved in localization and stabilization—such as WTAP [28], VIRMA [29], ZC3H13 [30], HAKAI [31], and RBM15/15B [32]—coordinate methylation within RRACH sequences. Among these, Wilms’ tumor 1-associating protein (WTAP) plays a critical role in directing the complex to nuclear speckles, which serve as RNA processing centers [28]. Vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated protein (VIRMA) guides preferential m6A methylation at the 3′UTR and near stop codons [29]. Zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 13 (ZC3H13) stabilizes the interaction between WTAP and RBM15 and helps to anchor the writer complex within the nucleus [30,33]. E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (HAKAI) is critical for maintaining MTC stability, although its precise mechanistic role in m6A deposition requires further investigation [31]. The RNA-binding proteins RBM15 and its paralog RBM15B facilitate substrate recognition; they bind to U-rich sequences on mRNA and recruit the writer complex to nearby adenosine residues for methylation [32]. Moreover, Methyltransferase-like 16 (METTL16) has been shown to catalyze methylation at the UACAGAGAA motif within a specific hairpin structure in the MAT2A 3′UTR [34].

2.2. m6A Erasers

The reversibility of m6A modification is ensured by two characterized demethylases, the FTO and AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5). FTO utilizes iron ions and 2-oxoglutarate (α-KG) as cofactors for its catalytic function. Through stepwise oxidation reactions, it first converts the methyl group in m6A into hydroxymethyladenosine (hm6A) and then, through oxidation, converts it into a formyl ester and thus brings about demethylation [35]. Importantly, FTO maintains broad substrate availability, targeting not only m6A but also other modifications such as N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am) and N1-methyladenosine (m1A) [35]. ALKBH5 exhibits catalytic activity similar to that of FTO, utilizing iron ions and α-KG to remove m6A modifications through oxidation. However, ALKBH5 is more specific, recognizing m6A solely on single-stranded RNA, and exhibits cell-type–dependent activity [36]. Despite both functioning as m6A demethylases, they are distinct in terms of substrate preference and cellular function. FTO acts more universally across various RNA modifications (m6A, m6Am, m1A), whereas ALKBH5 exhibits strong specificity for m6A. In certain disease conditions, such as cancer, both enzymes may coordinately orchestrate RNA metabolism through synergistic or overlapping activities, thus influencing disease development [37].

2.3. m6A Readers

The functional effects of m6A are interpreted by a diverse group of “reader” proteins. Among these, the YT521-B homology (YTH) domain-containing family is the most extensively studied. These proteins directly recognize and bind to m6A-modified sites via a characteristic hydrophobic pocket within their YTH domain, which specifically accommodates the methylated adenosine [38]. Research indicates that YTHDF1 promotes the translation efficiency of m6A-modified mRNAs by binding to m6A modification sites and recruiting translation initiation factors such as eIF3. This process accelerates mRNA transport onto ribosomes, enabling m6A-labeled mRNAs to be prioritized for translation [24]. As a primary inducer of mRNA degradation, YTHDF2 recognizes m6A sites through its YTH domain, subsequently recruiting the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex to promote deadenylation and degradation of target mRNAs [24]. This mechanism is crucial for rapid cellular clearance of unnecessary mRNAs and dynamic regulation of gene expression programs. YTHDF3 exhibits more complex functions and is considered a synergistic partner of both YTHDF1 and YTHDF2. It can co-activate translation with YTHDF1 and synergistically promote mRNA degradation with YTHDF2, potentially acting as a regulator to accelerate the overall metabolic turnover of m6A-modified mRNAs [39]. In the nucleus, YTHDC1 is the primary m6A reader and has multiple functions. It regulates the alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs by recruiting or repelling splicing factors like SRSF3 and SRSF10 [40]. Additionally, YTHDC1 facilitates the nuclear export of mature m6A-modified mRNAs by interacting with export factors such as NXF1 [9]. Members of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (HNRNP) family, such as HNRNPA2B1 and HNRNPC, also recognize m6A sites in the nucleus. They regulate splicing and influence RNA secondary structure, thereby shaping subsequent RNA metabolic processes [41,42]. YTHDC2, another cytoplasmic YTH-domain protein, enhances translation efficiency by recognizing m6A marks within the coding sequence. Unlike other YTH proteins, it exhibits a lower binding affinity for m6A, suggesting it may bind to specific contexts or employ a distinct mode of action [43]. Furthermore, insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins 1–3 (IGF2BP1–3) directly bind m6A RNA through their KH domains. In an m6A-dependent manner, they stabilize thousands of potential target mRNAs and enhance their translation, thereby broadly influencing gene expression outcomes [44]. Furthermore, other proteins such as G3BP1 and FMR1 have also been identified as m6A readers that respectively regulate the stability and translation rate of modified mRNAs [45].

2.4. m6A Modification in the Regulation of Adipocyte Development and Metabolism

Adipocytes play a central role in energy storage, metabolic regulation, and endocrine function. Their plasticity—the ability to expand, remodel, and switch functions in response to physiological demands—is essential for maintaining metabolic homeostasis [46,47]. FTO, a classical mRNA m6A demethylase, was the first gene identified to have the strongest genetic association with polygenic obesity and has been repeatedly linked to obesity in numerous studies [48,49]. The discovery of FTO as the first m6A mRNA demethylase established the concept of reversible RNA modification, laying the groundwork for integrating RNA methylation into adipose biology research [21]. Increasing evidence further indicates that m6A modification regulates the expression of transcription factors and AT–specific genes, thereby shaping lipid metabolic processes. Its role in adipocyte development and metabolic function merits deeper exploration and understanding.

2.5. Regulation of Adipogenesis by m6A Modification

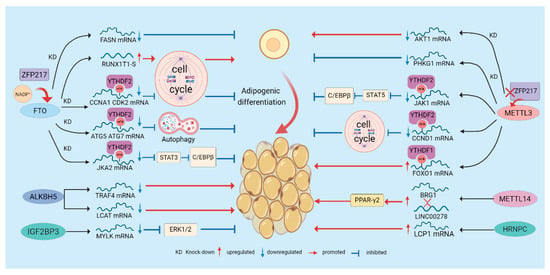

Adipogenesis, the differentiation of pre-adipocytes into mature, lipid-storing adipocytes, is a highly orchestrated process governed by a cascade of transcription factors and signaling pathways [50]. m6A modification exerts a critical bidirectional regulatory role in this process, highlighting the importance of maintaining balanced m6A levels in determining cell fate. Numerous functional studies show that FTO overexpression promotes adipogenesis by globally reducing cellular m6A levels, whereas FTO knockdown (KD) inhibits differentiation [51] (As shown in the left panel of Figure 2). Mechanistically, FTO modulates m6A marks near splice junctions to alter alternative splicing of the adipogenic regulator RUNX1T1, promoting production of a pro-adipogenic short isoform that drives mitotic clonal expansion(MCE)—a key early event in adipogenic commitment [52,53]. FTO also sustains cell-cycle progression by preserving expression of key regulators (e.g., CCNA2, CDK2). By preventing m6A accumulation on these transcripts, FTO averts YTHDF2-mediated decay and thereby supports cell-cycle progression and clonal expansion. Conversely, FTO KD increases m6A on these mRNAs, promoting YTHDF2-dependent degradation, prolonging the cell cycle, and inhibiting adipogenesis [54]. Autophagy is another FTO-regulated pathway: FTO deficiency elevates m6A on ATG5 and ATG7 mRNAs, triggering YTHDF2-dependent degradation, which suppresses essential autophagic activity and impairs adipocyte maturation [55]. Additionally, FTO modulates transcripts involved in lipid biosynthesis (e.g., FASN) and signaling pathways such as JAK2–STAT3–C/EBPβ; by altering m6A levels on these mRNAs, FTO affects their stability and expression to promote an adipogenic phenotype [56,57]. In contrast to FTO’s pro-adipogenic role, METTL3 acts as an adipogenesis suppressor in multiple models (As shown in the right panel of Figure 2). METTL3 cooperates with YTHDF1 to increase m6A on FOXO1 mRNA, enhancing its transcriptional activity and thereby inhibiting adipocyte differentiation [58]. In a model of pig bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells differentiating into adipocytes, METTL3 targets and inhibits the JAK1/STAT5/C/EBPβ signaling pathway through an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent mechanism, suppressing BMSC adipocyte differentiation [59]. This contrasts sharply with the positive regulation of a related pathway (JAK2–STAT3–C/EBPβ) by FTO, underscoring the finely tuned balance within the m6A regulatory system. More recent studies have shown that METTL3 KD reduces m6A modification of PHKG1 mRNA, leading to decreased PHKG1 expression. This reduction, in turn, upregulates downstream adipogenic genes and promotes adipocyte differentiation. In addition, loss of METTL3 decreases AKT1 expression in an m6A-dependent manner, which further favors adipogenic differentiation [60,61]. These discrepancies indicate that METTL3′s functional outcomes depend strongly on cell identity, the repertoire of target transcripts, and developmental or stimulatory context, underscoring the complex regulatory roles of m6A writers within adipogenic networks. Other m6A regulators also participate in adipogenesis. METTL14 modulates m6A on the long noncoding RNA LINC00278, enhancing its interaction with the chromatin remodeler BRG1 and activating the PPARγ2 pathway to promote adipogenesis, suggesting that writers can regulate adipogenesis via lncRNA-mediated epigenetic/chromatin mechanisms [62]. The demethylase ALKBH5 influences adipogenesis by modulating the stability of transcripts such as LCAT and TRAF4, indicating that distinct demethylases have specific roles in adipogenic regulation [63,64]. Reader proteins show diverse functions: YTHDC2 directly binds mRNAs of lipogenic genes (e.g., SREBP1, FASN, SCD1, ACC) and reduces their stability, thereby suppressing lipid biosynthesis [65]. HNRNPC binds an m6A motif in LCP1 mRNA to enhance its stability and modulate the cytoskeleton in a manner that favors adipogenesis [66]. IGF2BP3, in an m6A-dependent manner, stabilizes MYLK mRNA and subsequently suppresses ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which impedes adipogenic differentiation [67]. Together, these findings indicate that reader families act as selective “amplifiers” or “suppressors” of adipogenic fate by binding distinct sets of transcripts.

Figure 2.

Regulation of Adipogenesis by m6A Modification. m6A regulates adipogenesis through multiple mechanisms. “writers”, “erasers”, and “readers” dynamically modulate m6A modification, thereby influencing the degradation and translation of adipogenic regulators and affecting pathways such as the cell cycle and autophagy to control adipocyte differentiation. Moreover, certain regulatory factors or metabolites, such as NADP+ and ZFP217, can alter m6A modification and further modulate adipogenesis.

The adipogenic m6A network is further regulated upstream by metabolites and transcription factors: NADP+ acts as an allosteric activator of FTO, directly enhancing its demethylase activity and promoting adipogenesis, underscoring how metabolic state feeds back to epitranscriptomic enzymes [14]. The zinc-finger protein ZFP217 coordinates FTO activity by activating FTO transcriptionally and preserving FTO function post-transcriptionally via interaction with YTHDF2, thereby amplifying demethylation and driving adipogenesis. Conversely, ZFP217 loss upregulates METTL3, increases m6A on CCND1, promotes its degradation, and inhibits MCE and adipogenesis [68,69,70]. Finally, m6A is not confined to mRNA: METTL5-mediated m6A of 18S rRNA is critical for 80S ribosome assembly and selective translation. METTL5 loss selectively reduces the translational efficiency of key fatty acid metabolism enzymes (e.g., ACSL4), thereby inhibiting adipogenesis and highlighting rRNA m6A as an additional regulatory layer in lipid metabolism [71].

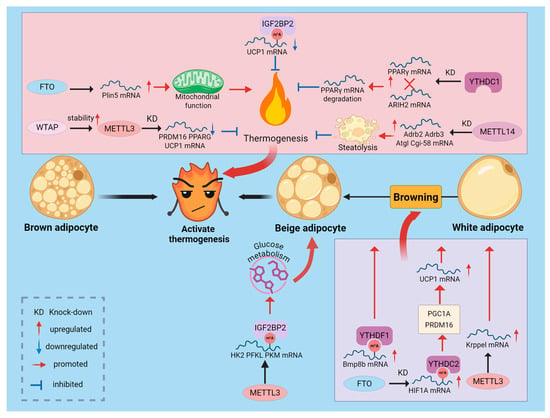

2.6. Regulation of Thermogenesis by m6A Modification

Mammals possess two main types of functional AT: white adipose tissue (WAT), which stores energy, and brown adipose tissue (BAT), which expends energy to generate heat. BAT uses uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) to convert chemical energy into heat, playing a critical role in maintaining body temperature and energy balance [72,73]. Additionally, under cold exposure or β3-agonist stimulation, WAT can transform into energy-expending beige adipose through a process called “browning,” offering a promising strategy to combat obesity. m6A modification acts as an energy switch, determining whether cells favor energy storage or expenditure. Genetic and molecular evidence directly implicates the m6A demethylase FTO in the regulation of thermogenesis. For example, functional variants at the FTO locus (e.g., rs1421085) have been shown to affect mitochondrial thermogenesis and browning in preadipocytes, suggesting a role for this locus in adipocyte fate determination [74]. Conversely, in animal and cellular models, FTO KD is typically associated with increased UCP1 expression and enhanced WAT browning, whereas FTO overexpression suppresses thermogenic phenotypes and favors maintenance of white adipocyte characteristics [75,76]. Mechanistically, FTO modulates thermogenic programs by altering m6A levels on key transcripts: One mechanistic study showed that FTO KD increases m6A on hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1A) mRNA; the modified transcript is recognized by the nuclear reader YTHDC2, which enhances HIF1A translation. Elevated HIF1A then activates thermogenic programs such as PGC1α and PRDM16, upregulating UCP1 and driving WAT browning [77]. In porcine adipocytes, FTO-mediated demethylation of Plin5 mRNA increases Plin5 protein levels, reduces lipid droplet size, enhances triglyceride turnover and mitochondrial respiratory function, and promotes thermogenesis [78]. Additionally, FTO has been reported to regulate BAT metabolism and WAT browning via miRNA expression changes, although the precise regulatory mechanisms remain to be elucidated [79].

In contrast to FTO, m6A writers generally promote thermogenesis in multiple contexts. Adipose-specific knockout(KO) of METTL3 substantially reduces tissue m6A levels and impairs BAT maturation and function, leading to decreased PRDM16, PPARγ, and UCP1 expression and compromised adaptive thermogenesis [80]. Concurrently, multiple studies demonstrate that METTL3 stabilizes or promotes translation of thermogenic transcripts (e.g., KLF9) and, together with readers such as IGF2BP2, maintains expression of glycolytic genes in beige adipocytes (HK2, PFKL, PKM), thereby supporting the substrate supply and energetic switch required for browning [81,82]. METTL14 deficiency reduces m6A content on mRNA for β-adrenergic receptor genes (ADRB2, ADRB3) and lipolytic genes (ATGL, CGI-58), increasing their translation and protein abundance in adipocytes. This augments β-adrenergic signaling and lipolysis, ultimately impairing thermogenic capacity [15]. Moreover, WTAP, a component that stabilizes the METTL3 complex, has been shown to participate in BAT development and energy metabolism by modulating writer complex stability and activity, underscoring the importance of complex integrity for thermogenic function [83].

m6A writers and erasers generate the epitranscriptomic “signal,” while distinct reader proteins determine how that signal is functionally interpreted. In adipocytes, YTHDF1 promotes the m6A-dependent translation of BMP8B, thereby inducing WAT browning [84]. By contrast, reader proteins such as IGF2BP2 can selectively modulate the translation or stability of mitochondrial proteins, including UCP1. IGF2BP2-deficient mice display increased UCP1 protein levels, enhanced translation of mitochondrial proteins, and resistance to HFD-induced obesity. In vitro reporter assays containing the UCP1 untranslated regions show that IGF2BP2 suppresses reporter translation, suggesting that IGF2BP2 binds UCP1 UTRs to reduce translation efficiency [85]. Moreover, SIRT7 deacetylates IGF2BP2 and thereby strengthens its inhibitory effect on UCP1 mRNA translation, suppressing brown adipose thermogenesis and revealing an upstream regulatory mechanism of IGF2BP2-mediated translational control [86]. Intriguingly, the circular RNA circ_0001874 interacts with IGF2BP2 and UCP1 to increase UCP1 translation and enhance thermogenesis [87]. Recent work also highlights the nuclear reader YTHDC1 as important for BAT development and PPARγ stability, revealing that readers can both regulate translation and influence protein homeostasis, including ubiquitination pathways [88]. Overall, a reader’s target specificity and functional domains determine whether an identical m6A mark is decoded to promote translation/stability or to trigger degradation/inhibit translation, thereby shaping thermogenic phenotypes.

In summary, m6A modification acts as a precise molecular regulator in thermogenesis control. The balance between FTO and METTL3/METTL14, along with selective recognition by downstream reader proteins, collectively determines the energy metabolic fate of AT (As shown in Figure 3). This complex, context-dependent regulatory network offers numerous potential targets for interventions aimed at increasing energy expenditure and treating obesity.

Figure 3.

Regulation of Adipose Thermogenesis by m6A Modification. m6A modification acts as an energy switch in the thermogenic process. FTO and METTL3/METTL14, by modulating m6A marks and leveraging selective recognition by distinct reader proteins, regulate the expression of thermogenesis-related genes, thereby influencing BAT thermogenesis and WAT browning.

2.7. Regulation of Lipolysis by m6A Modification

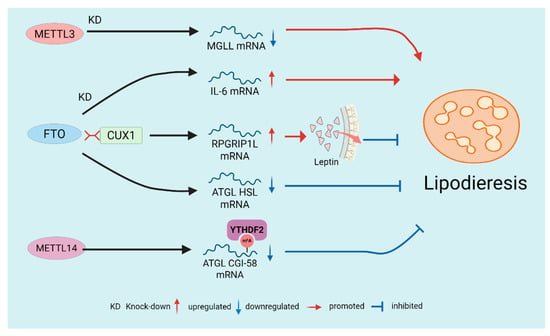

Lipolysis is the metabolic process of breaking down triglycerides (TG) stored in cellular lipid droplets. It is catalyzed by various lipases, including ATGL and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), which hydrolyze TG into free fatty acids and glycerol, resulting in reduced lipid droplet size [89]. Multiple studies have shown that m6A modification, through the coordinated action of writer and eraser enzymes with reader proteins, influences the breakdown of stored adipose, affecting both intracellular and extracellular lipid degradation(As shown in Figure 4). This highlights the role of m6A in energy mobilization and its potential as a target for managing lipid accumulation. Angiopoietin-like proteins 3, 4, and 8 (ANGPTL3, 4, 8) all contribute to triglyceride metabolism [90]. Notably, ANGPTL4 inhibits lipoprotein lipase, thereby suppressing extracellular lipolysis [91]. Studies show that injecting adenovirus encoding ANGPTL4 into adipose-specific FTO KO mice restores serum triglyceride levels and lipolytic capacity to levels comparable to controls [92]. This suggests that FTO KO affects ANGPTL4 levels in adipocytes and intracellular lipolysis. Furthermore, FTO KO increases IL-6 levels in 3T3-L1 cells, promoting the expression of lipolysis-related genes [93]. Research indicates that interactions at binding sites in FTO intron 1 with the transcription factor CUX1 upregulate RPGRIP1L, inhibiting leptin receptor transport and signaling, which reduces lipolysis [94]. Additionally, FTO reduces lipolysis by decreasing the expression of ATGL and HSL mRNA in AT [95]. Under intermittent hypoxia, downregulation of METTL3 alters m6A modifications and expression of MGLL mRNA, promoting lipolysis and demonstrating the context-dependent regulation of lipolysis by m6A [96]. Adipose-specific KO of METTL14 reduces m6A modifications, suppressing β-adrenergic signaling and lipolytic gene expression, which promotes obesity and liver lipid accumulation [15]. Recent studies reveal the underlying mechanism: YTHDF2 binds to m6A-modified transcripts, inhibiting the synthesis of key lipolytic factors such as ATGL and CGI-58, thereby suppressing lipolysis [97].

Figure 4.

Regulation of Lipolysis by m6A Modification. The demethylase FTO generally suppresses lipolysis by influencing multiple downstream targets, including ANGPTL4, IL-6, leptin signaling, and lipolytic enzyme genes. In contrast, the writer enzymes (METTL3/METTL14) typically promote lipolysis by modulating m6A modifications and subsequently regulating lipolysis-related genes.

2.8. Interactions Between m6A Modification and Adipokines

AT is also a vital endocrine organ that secretes adipokines in the form of hormones or cytokines, influencing metabolism, inflammation, and immune function locally and systemically. In obesity, AT dysfunction alters its endocrine profile, a key pathophysiological mechanism underlying obesity-related metabolic syndrome. Emerging evidence indicates that m6A and adipokines interact through mutual regulation, forming a complex feedback loop that influences systemic metabolism and inflammation (Table 1). This implies that interventions targeting m6A could broadly affect endocrine signaling and immune responses related to lipid metabolism. Adiponectin (APN) is an endogenous protein secreted by WAT that enhances energy utilization and insulin sensitivity while exhibiting anti-inflammatory properties [98]. AdipoAI, identified by Yu et al., is an orally active adiponectin receptor agonist that mimics APN’s anti-inflammatory effects [99]. Their study suggests that lncRNAs may participate in AdipoAI’s anti-inflammatory process in LPS-induced macrophages via competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks and m6A epigenetic regulation, indicating a potential link between m6A modification and APN’s anti-inflammatory actions. Leptin is a hormone secreted by adipocytes that crosses the blood-brain barrier and regulates appetite and energy expenditure through the hypothalamus [100]. Studies report that FTO mediates leptin resistance in HFD-induced obesity. The mechanism involves enhanced FTO/CX3CL1 pathway activity, which upregulates hypothalamic SOCS3 expression, impairing leptin signal transduction and the STAT3 pathway, leading to leptin resistance and obesity [101]. Additionally, research shows that inhibiting FTO in HFD-fed mice increases leptin levels in epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT), along with elevated inflammatory markers (MCP1, TNF-α), impacting lipid metabolism [102]. Plin5 is a scaffold protein important for lipid droplet formation. Wei et al. found that leptin regulates Plin5 m6A methylation by promoting FTO expression, affecting lipid metabolism and energy expenditure [78]. Resveratrol (RSV) exerts multiple anti-inflammatory effects. Supplementation with RSV has been reported to ameliorate HFD-induced disturbances in lipid metabolism, an effect that may be associated with reduced m6A RNA methylation and increased PPARα mRNA expression [103]. The adipokine resistin is closely associated with hepatic steatosis and other fatty liver diseases. Research demonstrates that melatonin in adipocytes enhances m6A RNA demethylation to promote resistin mRNA degradation, thereby alleviating endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated liver steatosis [104]. Retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4) functions not only as a vitamin A transporter but also as an adipokine that contributes to and exacerbates disturbances in glucose and lipid homeostasis [105]. Recent studies have linked RBP4 expression and stability to alterations in m6A [106]. These findings suggest that m6A modification may affect lipid metabolism by regulating RBP4 levels, although the precise mechanisms remain to be elucidated. IL-6 and TNF-α are major pro-inflammatory adipokines. Numerous studies have shown that the levels of m6A regulators—writers, erasers, and readers—change in response to TNF-α stimulation. Conversely, TNF-α concentrations are modulated by alterations in m6A regulator expression, indicating bidirectional crosstalk between TNF-α and the m6A machinery that together shape disease progression [107]. Moreover, perturbations in METTL3 or METTL14 alter the mRNA stability and translation of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, thereby either amplifying or attenuating inflammatory signaling [108,109].

Table 1.

Interactions between m6A Modification and Major Adipokines, with Potential Therapeutic Implications.

In summary, m6A modifications and adipokines form a tightly integrated “Adipo–m6A axis.” Adipokines (e.g., leptin, TNF-α, RBP4) can modulate m6A writers and erasers in a tissue and context-dependent manner, while m6A reciprocally regulates the protein expression and function of these factors by altering their mRNA stability, splicing, nucleo-cytoplasmic transport, and translation. Certain small molecules (for example, resveratrol, melatonin, or adiponectin receptor agonists) may tilt the m6A balance to produce multi-target effects and potentially reprogram this network.

3. m6A Modification in the Regulation of Metabolic Diseases

Dysregulation of the m6A modification network serves as a shared pathophysiological basis for various metabolic diseases, linking local lipid metabolism disruptions to systemic metabolic dysfunction. In humans, FTO expression levels correlate with higher serum leptin and lower high-density lipoprotein levels in obese individuals, highlighting the close relationship between m6A RNA methylation and glucose-lipid metabolism [110]. Notably, overall m6A levels often decrease in tissues from obese and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients, indicating that m6A dysregulation is a key feature of these disease states [111].

3.1. Role of m6A in Hepatic Lipid Homeostasis and Fatty Liver-Related Diseases

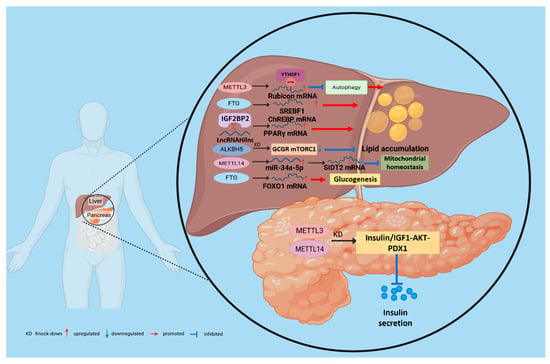

Given the liver’s role as the central organ of systemic energy metabolism, the dysregulation of its m6A epitranscriptome has been established as a key factor in the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis. Multiple studies have revealed multilayered effects of m6A on hepatocellular lipid metabolism via distinct molecular pathways: The demethylase FTO reduces global m6A levels in hepatocytes, decreases mitochondrial content, and promotes lipid accumulation; FTO also decreases m6A methylation on SREBF1 and ChREBP mRNAs, stabilizing these transcripts of key lipogenic transcription factors and thereby promoting steatosis [112,113]. Conversely, m6A “writers” also play critical roles in NAFLD: overall m6A levels are increased in NAFLD mouse models and in hepatocytes treated with free fatty acids, METTL3 directly methylates Rubicon mRNA, and YTHDF1 binds the m6A-marked transcript to enhance its stability; this suppresses autophagy and leads to lipid-droplet accumulation [114]. Notably, METTL3 functions in a cell-type-dependent manner: hepatocyte-specific METTL3 KO reduces overall m6A levels and produces NAFLD-like pathology [115], whereas myeloid-specific METTL3 deletion protects against age-related and diet-induced obesity and NAFLD [116]. This stark contrast highlights that the biological outcomes of m6A modulation are strictly determined by the cellular context. To provide a clear overview of these complexities, we have summarized the consensus and cell-type-specific roles of major m6A regulators in Table 2. Beyond METTL3 and FTO, other m6A regulators contribute to pathology through diverse pathways: METTL14 disrupts mitochondrial homeostasis by modulating the miR-34a-5p/SIDT2 axis [117]; Hepatocyte-specific ALKBH5 deletion reduces glucose and lipid levels by inhibiting GCGR and mTORC1 signaling; targeted downregulation of ALKBH5 reverses T2DM and MAFLD phenotypes in diabetic mice, suggesting therapeutic potential [118]. In addition, noncoding RNAs participate in m6A-mediated networks: the lncRNA Hilnc interacts with IGF2BP2 to regulate PPARγ mRNA stability, thereby contributing to hepatic steatosis [119]. At the signaling level, METTL3 increases m6A methylation of DDIT4 mRNA, thereby modulating mTORC1 and NF-κB pathways. METTL3 KD reduces lipid accumulation and inflammatory activity in hepatocytes from NAFLD patients [116], indicating that m6A regulates the fate of energy-metabolism transcripts and, via autophagy, mitochondrial function, and inflammatory–stress pathways, collectively controls hepatic lipid homeostasis (Figure 5).

Table 2.

Summary of Cell-Type-Specific Roles of m6A Regulators.

Figure 5.

m6A-mediated regulatory mechanisms of metabolic diseases in the liver and pancreas. m6A “writers,” “erasers,” and “readers” dynamically regulate methylation, thereby modulating the degradation and translation of downstream effectors and controlling pathways such as mitochondrial homeostasis, autophagy, lipid accumulation, and inflammation that together determine hepatic metabolic balance. Furthermore, m6A influences pancreatic β-cell proliferation and insulin secretory capacity, thereby affecting insulin resistance and the progression of T2D.

3.2. Role of m6A in Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes

Insulin resistance, a hallmark of T2D, arises from an impaired response to insulin in peripheral tissues such as the liver and skeletal muscle. Ectopic lipid accumulation in these tissues, a process driven by m6A modifications, is a direct cause of insulin resistance. For example, the overexpression of FTO in skeletal muscle enhances adipogenesis and oxidative stress, thereby impairing the insulin signaling pathway [120]. Secondly, m6A directly regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis. FTO drives excessive glucose production in the liver by demethylating and thereby upregulating the expression of the transcription factor FOXO1, which is a key mechanism underlying fasting hyperglycemia [121]. m6A modification also plays a decisive role in pancreatic β-cell development, differentiation, and functional maintenance. Loss of METTL3 disrupts cell fate decisions in pancreatic bipotent progenitors, impairing their differentiation into endocrine or ductal lineages and leading to abnormal islet architecture [122]. Acute deletion of METTL14 induces endoplasmic reticulum stress by activating the IRE1α/sXBP1 signaling pathway, resulting in impaired glucose tolerance [123]. In addition, IGF2BP2 recognizes and binds m6A-modified transcripts, such as PDX1, enhancing their stability and translation to sustain insulin secretion in β cells. Conversely, loss or dysfunction of IGF2BP2 reduces PDX1 expression, limits β-cell proliferation, and compromises insulin secretory capacity (Figure 5). Consistently, pancreatic islets from patients with T2D exhibit globally reduced m6A levels, which closely correlate with β-cell dysfunction and failure [124,125].

3.3. m6A-Mediated Inter-Organ Communication

Traditional models of metabolic disease have often focused on cell-autonomous defects within a single organ. However, maintaining metabolic homeostasis in an organism is highly dependent on a complex communication network between different organs. Emerging research reveals a revolutionary concept: m6A modification acts as a key mechanism governing this inter-organ dialogue. By controlling the expression of signaling molecules secreted by specific organs, m6A modification translates the epitranscriptomic state of one organ into systemic signals that influence whole-body metabolism(As shown in Figure 6). This perspective reflects the multifactorial nature of metabolic diseases and provides a more comprehensive framework for precision medicine. This paradigm shift enables a deeper understanding of how metabolic disorders propagate across tissues and supports the development of interventions that target upstream regulatory signals.

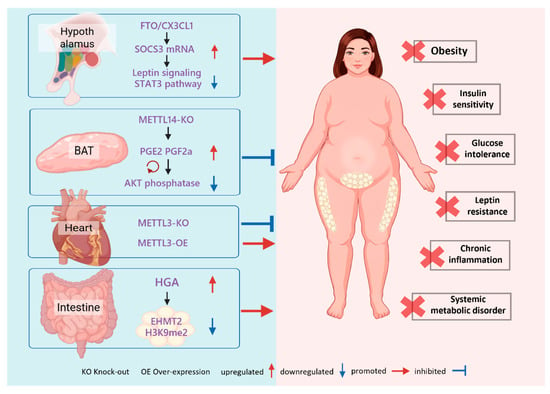

Figure 6.

m6A-Mediated Systemic Regulation. m6A modification serves as a systemic bridge by controlling organ-specific secretomes. Hypothalamic FTO drives obesity through the SOCS3-STAT3 axis, whereas BAT-specific METTL14 deficiency improves insulin sensitivity by boosting prostaglandin secretion. In the heart, METTL3 levels positively correlate with diet-induced metabolic disturbances. Additionally, gut-derived HGA signals to white adipose tissue to induce metabolic dysregulation via m6A modulation.

3.3.1. Beyond Cell Autonomy

The consequences of dysregulated m6A in a specific tissue extend far beyond the tissue itself. For instance, AT dysfunction is known to increase the release of free fatty acids and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which directly triggers insulin resistance in the liver and muscles—a classic example of pathological inter-organ communication [93,126]. However, recent studies suggest that the regulatory role of m6A is more proactive and profound. This modification can directly encode and dispatch regulatory signals, effectively transforming tissues like adipose into endocrine signaling hubs governed by the epitranscriptome.

3.3.2. BAT-Systemic Axis

Studies have found that the adipose-specific KO of METTL14 in BAT significantly improves systemic insulin sensitivity. Notably, this effect is independent of the classical thermogenic function mediated by UCP1. The underlying molecular mechanism involves the METTL14-mediated m6A modification of mRNAs encoding prostaglandin synthases (PTGES2 and CBR1). This methylation marks the transcripts for degradation facilitated by the reader proteins YTHDF2/3. Consequently, when METTL14 is knocked out, these mRNAs are stabilized, leading to increased synthesis and secretion of prostaglandins PGE2 and PGF2α from BAT. These prostaglandins then enter the circulation and act on distal tissues, where they enhance insulin signaling by inhibiting an AKT phosphatase, thereby improving systemic glucose homeostasis [127,128]. This discovery demonstrates that the epitranscriptomic state of BAT can directly regulate whole-body metabolism through the secretion of lipid signaling molecules.

3.3.3. Heart as an m6A-Regulated Endocrine Organ

Compelling evidence also emerges from studies on the heart. Mice with a cardiomyocyte-specific KO of METTL3 were found to be resistant to weight gain, obesity, and glucose intolerance induced by a Western diet. Conversely, overexpressing METTL3 in the myocardium exacerbated these metabolic disorders. Studies indicate that m6A methylation critically regulates FGF1, and that cardiac expression of FGF1 may have important effects on whole-body metabolism [129]. These findings reveal that the heart can secrete m6A-regulated factors that modulate systemic energy balance and adaptive responses to nutritional challenges. Consequently, the heart should be regarded as an active endocrine node within the metabolic regulatory network. Although cardiac factors such as ANP/BNP, FGF16, and YBX1 have been implicated in cardiac disease, the full repertoire of heart-derived metabolic signals remains incompletely characterized [130,131,132]. Future studies combining cardiomyocyte-specific KO models with secretome/proteomic profiling could identify additional m6A-regulated secreted mediators and better define the heart’s endocrine potential.

3.3.4. Gut–Microbiota–Adipose Tissue Axis as a Potential Regulatory Pathway

Interactions between the host epitranscriptome and the gut microbiota represent a complex and critical dimension of metabolic regulation. Recent work has reshaped our view of the gut–liver and gut–adipose axes, revealing the microbiota as a powerful regulator of the host m6A methylation landscape [133]. Evidence indicates that the gut microbiome is essential for maintaining normal m6A topology in the mouse cecum and liver. In germ-free mice, loss of microbial signals causes marked rearrangements of m6A patterns, which impair the translation efficiency of transcripts involved in lipid metabolism, inflammation, and circadian regulation [134].These findings define a novel “microbiota–m6A–lipid metabolism” axis: dysbiosis perturbs lipid homeostasis not only via microbial metabolites but also by ‘hijacking’ the host epitranscriptomic machinery and rewriting metabolic programs at the level of post-transcriptional modification.

At the molecular level, this communication is primarily mediated by bioactive molecules derived from the microbiota. Diet-induced dysbiosis, for example, following a HFD, results in the release of specific bacterial metabolites (such as homogentisic acid, HGA) and cell-wall components (e.g., lipopolysaccharide, LPS) into the circulation, where they act as distal signaling molecules. These microbial signals target distal organs such as AT, provoking inflammation and directly reshaping the host m6A methylation landscape [135,136,137]. For example, exogenous HGA has been shown to increase m6A modification of the methyltransferase EHMT2 in eWAT, reducing EHMT2 protein abundance and downstream H3K9me2 levels, thereby precipitating metabolic dysfunction [135]. This mechanism delineates a novel pathological axis that links external environmental triggers (diet), intermediate mediators (microbiota and microbial metabolites such as HGA), and internal regulatory circuits (m6A-mediated epitranscriptomic cascades). Recent studies further demonstrate the pathogenic role of this axis in metabolic disease: distinct microbial signatures can differentially modulate the activity of m6A writers or erasers, alter the stability of mRNAs encoding key adipogenic and lipolytic genes, and thereby drive obesity and metabolic dysfunction [138,139]. Together, these observations suggest that the gut microbiota functions as an external “writer” of the host metabolic code, and that its perturbation can directly misprogram host metabolic programs.

Based on these findings, interventions targeting this axis hold substantial clinical promise. Chen et al. provide evidence that probiotic interventions or other microbiome-targeted therapies can restore host m6A homeostasis and thereby ameliorate lipid metabolic disturbances [140]. These observations are reshaping the etiological framework for metabolic diseases, suggesting that systemic disorders such as T2D or MASLD may not always originate from intrinsic defects in symptomatic organs (e.g., pancreas or liver), but can instead begin with m6A dysregulation in the gut—a “signaling organ” that triggers distal cascade effects. Accordingly, future therapeutic strategies should shift from solely treating insulin resistance or hepatic steatosis toward developing agents that precisely target m6A pathways in the gut as a signaling organ. This organ-centric, epitranscriptomic communication paradigm aims to correct aberrant inter-organ signaling and thereby open promising new avenues for precision therapies against obesity and metabolic-associated liver disease.

4. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting the m6A Pathway

Given the central regulatory role of m6A in obesity and metabolic diseases, targeting its pathway has become a novel and highly attractive area for drug development. Current research primarily focuses on creating small-molecule inhibitors of m6A writer and eraser enzymes (Table 3). However, these approaches differ conceptually: while inhibiting writers or erasers directly alters m6A abundance and causes broad, global effects—an approach suited to diseases driven by a single dominant mechanism—targeting readers enables more selective, transcript-specific ‘fine-tuning’ with substantial therapeutic potential but greater development challenges.

Table 3.

Drugs and Compounds Targeting the m6A Pathway for Metabolic Disease Research.

4.1. Development of FTO Inhibitors for m6A Modulation

As the m6A modulator with the strongest genetic association to obesity, FTO is the most extensively studied drug target in this field. Significant progress has been made in the development of FTO inhibitors. Several natural compounds have been identified as having FTO-inhibitory activity, including epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) from green tea and rhein from the traditional Chinese medicine rhubarb [141,146]. While they have shown potential to inhibit adipogenesis and improve metabolism in preclinical studies, these compounds generally suffer from insufficient potency and selectivity. Through drug repositioning and structure-based design, several existing drugs have been found to inhibit FTO. Examples include entacapone, used for Parkinson’s disease, and meclofenamic acid, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug [121,142]. These repurposed drugs offer the potential to accelerate the transition to clinical studies. Concurrently, a series of highly selective small molecules developed through crystal structure analysis and rational design (e.g., FB23, FB23-2, N-CDPCB, CHTB) have demonstrated controllable inhibitory activity and pharmacological effects in vitro and in in vivo oncology models [143]. These compounds have laid the chemical foundation for more potent and selective FTO inhibitors. It is important to note, however, that in vivo validation of these candidates in the context of metabolic diseases is still very limited, with most studies focusing on cancer or proof-of-concept applications [147,148].

4.2. Development of METTL3 Inhibitors for m6A Modulation

Although the development of METTL3 inhibitors has been predominantly focused on oncology, their potential application in metabolic diseases is beginning to gain attention. STM2457 has been reported as a highly potent and selective small-molecule inhibitor of METTL3 [149]. In mouse models of HFD-induced obesity and MASLD, treatment with STM2457 significantly reduced hepatic lipid deposition, decreased body weight, improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, and lowered liver transaminases and triglyceride levels. These results indicate that pharmacological inhibition of METTL3 can reverse lipid metabolism disorders under certain experimental conditions [144]. Furthermore, the natural product quercetin has also been identified as having METTL3-inhibitory activity [145]. However, applying METTL3 inhibitors to metabolic diseases presents unique challenges. As previously discussed, METTL3 can exert opposing effects in different cell types (e.g., hepatocytes versus myeloid cells). Consequently, systemic inhibition of METTL3 could produce complex or even detrimental net effects. Future therapeutic strategies will likely require the development of cell-type-specific delivery systems to achieve precise and beneficial interventions.

4.3. Exploring m6A Reader Protein Modulation

Compared to inhibitors of writer or eraser enzymes, which alter global m6A levels, targeting reader proteins offers a more nuanced intervention strategy. By inhibiting or activating a specific reader protein, it is theoretically possible to influence only the subset of RNAs bound by that reader. This approach could lead to more precise therapeutic effects with a reduced risk of off-target complications [150]. However, the development of potent and specific small-molecule modulators for m6A reader proteins is still in its infancy. This represents a significant knowledge gap and a critical future direction for drug discovery in this field.

4.4. Challenges and Future Directions for m6A-Targeted Therapies

Despite its promise, translating m6A-targeted therapies from bench to bedside faces multiple challenges that must be addressed through precision strategies and emerging technologies to achieve clinically translatable interventions: (1) Long-term safety: Because m6A is a fundamental layer of RNA regulation, chronic or global modulation may perturb tumor suppression, neurodevelopment, immune function, and cardiovascular homeostasis, potentially increasing risks such as cancer progression, enhanced inflammation, or stem-cell dysfunction [151,152,153]. These concerns mandate a shift toward precision targeting and comprehensive safety assessment, including long-term animal studies and biomarker monitoring. (2) Specificity: Achieving high selectivity for target enzymes (e.g., FTO, ALKBH5) or individual reader proteins is essential to minimize off-target effects. Emerging tools based on CRISPR–Cas13 enable site- or transcript-specific installation or removal of m6A, providing powerful approaches for target validation and specificity optimization [154,155]. Cas13-based systems have demonstrated in vivo RNA-regulatory activity in animal models of antiviral defense and inflammation, offering proof-of-concept for functional validation [156]. Such programmable systems can help bridge the gap between global intervention risks and precision therapeutics by enabling specificity optimization. (3) Tissue and cell-type targeting: Because m6A regulators have divergent roles across tissues and cell types, strategies that deliver therapeutics precisely to target tissues (e.g., adipose depots or hepatic macrophages) are essential and represent a key means to reduce risks associated with global m6A modulation. Current delivery platforms—including lipid nanoparticles, membrane-modified or cell membrane–coated nanoparticles, exosome–liposome hybrids, and other biomimetic nanoparticles—provide promising frameworks for m6A-targeted interventions [157,158,159]. However, these delivery systems must be co-designed with specific m6A targets and regulatory strategies, and their tissue specificity, safety, and controllability should be rigorously evaluated in preclinical studies to advance m6A-targeted therapies toward precise and translatable clinical applications.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This review describes m6A RNA modification as a central component of the epitranscriptome and highlights its pivotal role in regulating lipid metabolism and related metabolic diseases. From controlling adipocyte differentiation and function to mediating complex inter-organ communication and driving the pathophysiology of systemic metabolic disorders (Figure 6), the m6A regulatory network exerts critical control over metabolic homeostasis.

Despite rapid progress over the past decade, several crucial regions in the landscape of m6A remain to be explored: (1) Cell-Type-Specific m6A Profiles and Functions: Current studies predominantly rely on whole tissues or homogenized cell lines. There is an urgent need to utilize high-resolution technologies such as single-cell sequencing to map cell-type-specific m6A methylation patterns (methylomes) and their dynamic changes across various metabolic tissues (e.g., adipose, liver, pancreas) and cell types (e.g., adipocytes, hepatocytes, macrophages, endothelial cells, β-cells) in both healthy and diseased human states. This will help explain why the same m6A regulator produces markedly different effects in different cells. (2) Molecular Messengers in Inter-Organ Communication: Beyond the identified BAT-prostaglandin axis, the identities of other m6A-regulated organokines, their secretion mechanisms, and their modes of action in distal target organs remain a significant “black box.” Elucidating these pathways is a key priority for future research. (3) Crosstalk with Other Epigenetic Modifications: The m6A modification does not exist in isolation. How it interacts—either synergistically or antagonistically—with DNA methylation, histone modifications, and other RNA modifications (e.g., m5C, m1A) to form a higher-order regulatory network for gene expression is still largely unknown. (4) Translation from Animal Models to Humans: The vast majority of current findings are derived from mouse models. The extent to which these discoveries can be translated to human physiology and pathology requires rigorous validation through more extensive human cohort studies and analysis of clinical samples.

In conclusion, a deeper understanding of the m6A epitranscriptome not only offers new perspectives and targets for lipid metabolism research but also provides a novel key to unraveling the complex pathogenesis of obesity and metabolic diseases. Precisely modulating this dynamic regulatory network may enable new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for obesity, T2D, and fatty liver disease and will be instrumental in advancing our understanding and treatment of metabolic syndrome.

Author Contributions

Q.Z. and L.Z. conceptualized the manuscript. Q.Z. investigated and wrote the original draft. Y.H. and M.L. created the figures and tables. H.Y., L.Z. and Y.Z. revised the manuscript. L.Z. and Y.Z. provided guidance for the entire study. All individuals who qualify for authorship are listed as authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32372834, 32502861), the Science and technology research project of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (No. KJQN202500210), Chongqing Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System (CQMAITS202513), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2025M780244), the Collection, Utilization and Innovation of Germplasm Resources by Research Institutes and Enterprises of Chongqing, China (cqnyncw-kqlhtxm), the Chongqing Science and Technology Innovation Special Project (No. CSTB2022TIAD-CUX0013) and the Chongqing Graduate Student Research Innovation Project (No. CYS25175).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| 3′-UTRs | 3′ untranslated regions |

| α-KG | 2-oxoglutarate |

| ALKBH5 | AlkB homolog 5 |

| ANGPTL3, 4, 8 | Angiopoietin-like proteins 3, 4, and 8 |

| APN | Adiponectin |

| AT | adipose tissue |

| BAT | brown adipose tissue |

| ceRNA | competing endogenous RNA |

| EGCG | epigallocatechin gallate |

| eWAT | epididymal white adipose tissue |

| FASN | fatty acid synthase |

| FTO | fat mass and obesity-associated |

| HAKAI | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase |

| HFD | high-fat diet |

| HGA | homogentisic acid |

| HIF1A | hypoxia-inducible factor 1α |

| HNRNP | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein |

| HSL | hormone-sensitive lipase |

| IGF2BP1–3 | insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins 1–3 |

| KD | knockdown |

| KO | knockout |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| m1A | N1-methyladenosine |

| m6A | N6-methyladenosine |

| m6Am | N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine |

| MACOM | m6A-METTL associated complex |

| MASLD | metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MCE | mitotic clonal expansion |

| METTL3 | Methyltransferase-like 3 |

| METTL14 | Methyltransferase-like 14 |

| METTL16 | Methyltransferase-like 16 |

| MTC | methyltransferase complex |

| NADP+ | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NAFLD | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| RBP4 | Retinol-binding protein 4 |

| RSV | Resveratrol |

| TG | triglycerides |

| T2D | type 2 diabetes |

| UCP1 | uncoupling protein 1 |

| VIRMA | Vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated protein |

| WAT | white adipose tissue |

| WTAP | Wilms’ tumor 1-associating protein |

| YTH | YT521-B homology |

| ZC3H13 | Zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 13 |

References

- Gupta, A.; Shah, K.; Gupta, V. Interconnected epidemics: Obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases—Insights from research and prevention strategies. Discov. Public Health 2025, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.; Gakidou, E.; Lo, J.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, N.; Abbasian, M.; Abd ElHafeez, S.; Abdel-Rahman, W.M.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of adult overweight and obesity, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: A forecasting study for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busebee, B.; Ghusn, W.; Cifuentes, L.; Acosta, A. Obesity: A review of pathophysiology and classification. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2023, 98, 1842–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakers, A.; De Siqueira, M.K.; Seale, P.; Villanueva, C.J. Adipose-tissue plasticity in health and disease. Cell 2022, 185, 419–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Liu, R.; Meng, Y.; Xing, D.; Xu, D.; Lu, Z. Lipid metabolism and cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20201606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrig, F.; Schulze, A. The multifaceted roles of fatty acid synthesis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 732–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cypess, A.M.; Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J.; Kazak, L.; Chang, D.C.; Krakoff, J.; Tseng, Y.; Scheele, C.; Boucher, J.; Petrovic, N.; et al. Emerging debates and resolutions in brown adipose tissue research. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, A.M. An overview of epigenetics in obesity: The role of lifestyle and therapeutic interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundtree, I.A.; Evans, M.E.; Pan, T.; He, C. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell 2017, 169, 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.S.; Roundtree, I.A.; He, C. Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, R.M.; Morgan, M.A.; Shatkin, A.J. Influenza viral mRNA contains internal N6-methyladenosine and 5′-terminal 7-methylguanosine in cap structures. J. Virol. 1976, 20, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, D.; Liu, T.; Chen, J.; Yu, J.; Yi, P. N6-methyladenosine-mediated gene regulation and therapeutic implications. Trends Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Dai, Q.; Zheng, G.; Yang, Y.; Yi, C.; Lindahl, T.; Pan, T.; Yang, Y.; et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Song, C.; Wang, N.; Li, S.; Liu, Q.; Sun, Z.; Wang, K.; Yu, S.C.; Yang, Q. NADP modulates RNA m6A methylation and adipogenesis via enhancing FTO activity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 1394–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Ren, D.; Ky, A.; MacDougald, O.A.; O’Rourke, R.W.; Rui, L. Adipose METTL14-elicited n6-methyladenosine promotes obesity, insulin resistance, and NAFLD through suppressing β adrenergic signaling and lipolysis. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2301645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Cai, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, K.; Sun, K.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Gu, C.; Huang, X.; et al. Dysregulated m6A modification promotes lipogenesis and development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 2342–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, G. Metabolic control of m6A RNA modification. Metabolites 2021, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.D.; Saletore, Y.; Zumbo, P.; Elemento, O.; Mason, C.E.; Jaffrey, S.R. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 2012, 149, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Hou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Cao, X. The RNA helicase DDX46 inhibits innate immunity by entrapping m6A-demethylated antiviral transcripts in the nucleus. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertero, A.; Brown, S.; Madrigal, P.; Osnato, A.; Ortmann, D.; Yiangou, L.; Kadiwala, J.; Hubner, N.C.; de Los, M.I.; Sadee, C.; et al. The SMAD2/3 interactome reveals that TGFbeta controls m6A mRNA methylation in pluripotency. Nature 2018, 555, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosovic, M.; Molares, H.C.; Gregorova, P.; Hrossova, D.; Kudla, G.; Vanacova, S. N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO targets pre-mRNAs and regulates alternative splicing and 3′-end processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 11356–11370. [Google Scholar]

- Coots, R.A.; Liu, X.M.; Mao, Y.; Dong, L.; Zhou, J.; Wan, J.; Zhang, X.; Qian, S.B. m6A facilitates eIF4f-independent mRNA translation. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 504–514.e7. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, I.; Tzelepis, K.; Pandolfini, L.; Shi, J.; Millan-Zambrano, G.; Robson, S.C.; Aspris, D.; Migliori, V.; Bannister, A.J.; Han, N.; et al. Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m6A-dependent translation control. Nature 2017, 552, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Gomez, A.; Hon, G.C.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Fu, Y.; Parisien, M.; Dai, Q.; Jia, G.; et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 2014, 505, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsen, T.W. Molecular biology. Internal mRNA methylation finally finds functions. Science 2014, 343, 1207–1208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Weng, H.; Chen, J. m6A modification in coding and non-coding RNAs: Roles and therapeutic implications in cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Doxtader, K.A.; Nam, Y. Structural basis for cooperative function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 methyltransferases. Mol. Cell 2016, 63, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, X.L.; Sun, B.F.; Wang, L.; Xiao, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.J.; Adhikari, S.; Shi, Y.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Y.S.; et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA n6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Liu, J.; Cui, X.; Cao, J.; Luo, G.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, T.; Gao, M.; Shu, X.; Ma, H.; et al. VIRMA mediates preferential m6A mRNA methylation in 3′UTR and near stop codon and associates with alternative polyadenylation. Cell Discov. 2018, 4, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.; Lv, R.; Ma, H.; Shen, H.; He, C.; Wang, J.; Jiao, F.; Liu, H.; Yang, P.; Tan, L.; et al. Zc3h13 regulates nuclear RNA m6A methylation and mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 1028–1038.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawankar, P.; Lence, T.; Paolantoni, C.; Haussmann, I.U.; Kazlauskiene, M.; Jacob, D.; Heidelberger, J.B.; Richter, F.M.; Nallasivan, M.P.; Morin, V.; et al. Hakai is required for stabilization of core components of the m6A mRNA methylation machinery. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, D.P.; Chen, C.K.; Pickering, B.F.; Chow, A.; Jackson, C.; Guttman, M.; Jaffrey, S.R. m6A RNA methylation promotes XIST-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature 2016, 537, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuckles, P.; Lence, T.; Haussmann, I.U.; Jacob, D.; Kreim, N.; Carl, S.H.; Masiello, I.; Hares, T.; Villasenor, R.; Hess, D.; et al. Zc3h13/flacc is required for adenosine methylation by bridging the mRNA-binding factor rbm15/spenito to the m6A machinery component wtap/fl(2)d. Genes. Dev. 2018, 32, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendleton, K.E.; Chen, B.; Liu, K.; Hunter, O.V.; Xie, Y.; Tu, B.P.; Conrad, N.K. The u6 snRNA m6A methyltransferase METTL16 regulates SAM synthetase intron retention. Cell 2017, 169, 824–835.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, L.H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Yan, N.; Amu, G.; Tang, X.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structural insights into FTO’s catalytic mechanism for the demethylation of multiple RNA substrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2919–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Tam, N.Y.; McDonough, M.A.; Schofield, C.J.; Aik, W.S. Mechanisms of substrate recognition and n6-methyladenosine demethylation revealed by crystal structures of ALKBH5-RNA complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 4148–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zha, X.; Li, M.; Xia, X.; Wang, S. Insights into the m6A demethylases FTO and ALKBH5: Structural, biological function, and inhibitor development. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhong, X.; Xia, M.; Zhong, J. The roles and mechanisms of the m6a reader protein YTHDF1 in tumor biology and human diseases. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 26, 1270–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, B.S.; Ma, H.; Hsu, P.J.; Liu, C.; He, C. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N6-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Adhikari, S.; Dahal, U.; Chen, Y.S.; Hao, Y.J.; Sun, B.F.; Sun, H.Y.; Li, A.; Ping, X.L.; Lai, W.Y.; et al. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, C.R.; Goodarzi, H.; Lee, H.; Liu, X.; Tavazoie, S.; Tavazoie, S.F. HNRNPA2b1 is a mediator of m6A-dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell 2015, 162, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Dai, Q.; Zheng, G.; He, C.; Parisien, M.; Pan, T. N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature 2015, 518, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Chen, H.; Li, K.; Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Tan, H. The biological function of the n6-methyladenosine reader YTHDC2 and its role in diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Weng, H.; Sun, W.; Qin, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; Zhao, B.S.; Mesquita, A.; Liu, C.; Yuan, C.L.; et al. Recognition of RNA N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edupuganti, R.R.; Geiger, S.; Lindeboom, R.; Shi, H.; Hsu, P.J.; Lu, Z.; Wang, S.Y.; Baltissen, M.; Jansen, P.; Rossa, M.; et al. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) recruits and repels proteins to regulate mRNA homeostasis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taura, D.; Noguchi, M.; Sone, M.; Hosoda, K.; Mori, E.; Okada, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Homma, K.; Oyamada, N.; Inuzuka, M.; et al. Adipogenic differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells: Comparison with that of human embryonic stem cells. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Xie, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Xu, K.; Fu, M.; Thompson, W.E.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.E. Derivation of adipocytes from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2005, 14, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, S.K.; Alsafar, H.; Sajini, A.A. FTO m6A demethylase in obesity and cancer: Implications and underlying molecular mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Yu, G.; Zhu, X.; Peng, T.; Lv, Y. Critical roles of FTO-mediated mRNA m6A demethylation in regulating adipogenesis and lipid metabolism: Implications in lipid metabolic disorders. Genes Dis. 2022, 9, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota De Sa, P.; Richard, A.J.; Hang, H.; Stephens, J.M. Transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis. Compr. Physiol. 2017, 7, 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Guo, F.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Chai, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, R. The demethylase activity of FTO (fat mass and obesity associated protein) is required for preadipocyte differentiation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, B.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X.; Xiao, W.; Hao, Y.; Ping, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 1403–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkestein, M.; Laber, S.; McMurray, F.; Andrew, D.; Sachse, G.; Sanderson, J.; Li, M.; Usher, S.; Sellayah, D.; Ashcroft, F.M.; et al. FTO influences adipogenesis by regulating mitotic clonal expansion. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Liu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Bi, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Cai, M.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; et al. FTO regulates adipogenesis by controlling cell cycle progression via m6A-YTHDF2 dependent mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2018, 1863, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Bi, Z.; Yao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shi, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y. m6A mRNA methylation controls autophagy and adipogenesis by targeting atg5 and atg7. Autophagy 2020, 16, 1221–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Z. Fat mass and obesity-associated protein regulates lipogenesis via m6A modification in fatty acid synthase mRNA. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Guo, G.; Bi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, N.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. m6A methylation modulates adipogenesis through JAK2-STAT3-c/EBPbeta signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2019, 1862, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, J.; Yuan, J.; Ding, R.; Yang, G.; Cao, J.; Zhao, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, P.; et al. Harnessing engineered exosomes as METTL3 carriers: Enhancing osteogenesis and suppressing lipogenesis in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for postmenopausal osteoporosis treatment. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 32, 101648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Bi, Z.; Wu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. METTL3 inhibits BMSC adipogenic differentiation by targeting the JAK1/STAT5/c/EBPbeta pathway via an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent manner. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 7529–7544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, M.; Wang, M.; Han, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Tian, T.; Pang, W.; Cai, R. Profiling of m6A methylation in porcine intramuscular adipocytes and unravelling PHKG1 represses porcine intramuscular lipid deposition in an m6A-dependent manner. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 272, 132728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Cai, D.; Liu, J.; Hu, H.; You, R.; Pan, Z.; Chen, S.; Xu, K.; Dai, W.; Zhang, S.; et al. Deletion of mettl3 in mesenchymal stem cells promotes acute myeloid leukemia resistance to chemotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ren, Z.; Mao, R.; Yi, W.; Wang, B.; Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y. LINC00278 and BRG1: A key regulatory axis in male obesity and preadipocyte adipogenesis. Metabolism 2025, 168, 156194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, X.; Guo, L.; Ye, C.; Liu, A.; Wang, X.; Ye, M.; Fan, Z.; Luan, K.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C.; et al. ALKBH5 regulates chicken adipogenesis by mediating LCAT mRNA stability depending on m6A modification. BMC Genomics 2024, 25, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, S.; Li, J.; Cai, Z.; Pan, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, Z.; Ye, G.; Zheng, G.; Li, M.; Liu, W.; et al. TRAF4 acts as a fate checkpoint to regulate the adipogenic differentiation of MSCs by activating PKM2. EBioMedicine 2020, 54, 102722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Liu, C.; Xu, L.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, W.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, J.; Meng, M.; Zheng, Y.; et al. N6-methyladenosine reader protein YT521-b homology domain-containing 2 suppresses liver steatosis by regulation of mRNA stability of lipogenic genes. Hepatology 2021, 73, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Cui, Y.; Yue, L.; Zhang, T.; Huang, C.; Yu, X.; Ma, D.; Liu, D.; Cheng, R.; Zhao, X.; et al. m6A reader HNRNPC facilitates adipogenesis by regulating cytoskeletal remodeling through enhanced lcp1 mRNA stability. Aging Dis. 2024, 16, 1080–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; He, W.; Fan, S.; Li, H.; Ye, G. IGF2BP3-mediated enhanced stability of MYLK represses MSC adipogenesis and alleviates obesity and insulin resistance in HFD mice. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xiang, H.; Zhong, Z.; Peng, Y.; Jiang, S. The emerging role of zfp217 in adipogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Yang, Y.; Wei, H.; Xie, X.; Lu, J.; Zeng, Q.; Peng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, S.; Peng, J. Zfp217 mediates m6a mRNA methylation to orchestrate transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation to promote adipogenic differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 6130–6144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, R.; Jiang, Q.; Cai, M.; Bi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. ZFP217 regulates adipogenesis by controlling mitotic clonal expansion in a METTL3-m6A dependent manner. RNA Biol. 2019, 16, 1785–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Chen, B.; Wei, W.; Guo, S.; Han, H.; Yang, C.; Ma, J.; Wang, L.; Peng, S.; Kuang, M.; et al. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) in 18s rRNA promotes fatty acid metabolism and oncogenic transformation. Nat. Metab. 2022, 4, 1041–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothwell, N.J.; Stock, M.J. Diet-induced thermogenesis. Adv. Nutr. Res. 1983, 5, 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cypess, A.M.; Lehman, S.; Williams, G.; Tal, I.; Rodman, D.; Goldfine, A.B.; Kuo, F.C.; Palmer, E.L.; Tseng, Y.H.; Doria, A.; et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, N.; Yin, N.; Liu, R.; He, Y.; Li, D.; Tong, M.; Gao, A.; Lu, P.; Zhao, Y.; et al. The rs1421085 variant within FTO promotes brown fat thermogenesis. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 1337–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tews, D.; Fischer-Posovszky, P.; Fromme, T.; Klingenspor, M.; Fischer, J.; Ruther, U.; Marienfeld, R.; Barth, T.F.; Moller, P.; Debatin, K.M.; et al. FTO deficiency induces UCP-1 expression and mitochondrial uncoupling in adipocytes. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 3141–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claussnitzer, M.; Dankel, S.N.; Kim, K.; Quon, G.; Meuleman, W.; Haugen, C.; Glunk, V.; Sousa, I.S.; Beaudry, J.L.; Puviindran, V.; et al. FTO obesity variant circuitry and adipocyte browning in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhuang, L.; Chen, W.; Zeng, B.; Liao, X.; Guo, G.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. M6a methylation promotes white-to-beige fat transition by facilitating hif1a translation. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e52348. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.; Sun, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Sun, C. Leptin reduces plin5 m6A methylation through FTO to regulate lipolysis in piglets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronkainen, J.; Mondini, E.; Cinti, F.; Cinti, S.; Sebert, S.; Savolainen, M.J.; Salonurmi, T. Fto-deficiency affects the gene and MicroRNA expression involved in brown adipogenesis and browning of white adipose tissue in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhu, F.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Jia, L.; Xie, L.; Chen, Z. METTL3 is essential for postnatal development of brown adipose tissue and energy expenditure in mice. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, R.; Yan, S.; Zhou, X.; Gao, Y.; Qian, Y.; Hou, J.; Chen, Z.; Lai, K.; Gao, X.; Wei, S. Activation of METTL3 promotes white adipose tissue beiging and combats obesity. Diabetes 2023, 72, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ping, X.; Wang, D.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; et al. RNA m6 a methylation regulates glycolysis of beige fat and contributes to systemic metabolic homeostasis. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2300436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Zhou, L.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Gao, M.; Gao, L.; Xu, Y.; et al. WTAP regulates postnatal development of brown adipose tissue by stabilizing METTL3 in mice. Life Metab. 2022, 1, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Zhou, X.; Wu, C.; Gao, Y.; Qian, Y.; Hou, J.; Xie, R.; Han, B.; Chen, Z.; Wei, S.; et al. Adipocyte YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA-binding protein 1 protects against obesity by promoting white adipose tissue beiging in male mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]