Abstract

Nav1.5 is one of the nine voltage-gated sodium channel-alpha subunit (VGSC-α) family members. The Nav1.5 channel typically carries an inward sodium ion current that depolarises the membrane potential during the upstroke of the cardiac action potential. The neonatal isoform of Nav1.5, nNav1.5, is produced via VGSC-α alternative splicing. nNav1.5 is known to potentiate breast cancer metastasis. Despite their well-known biological functions, the immunological perspectives of these channels are poorly explored. The current review has attempted to summarise the triad between Nav1.5 (nNav1.5), breast cancer, and the immune system. To date, there is no such review available that encompasses these three components as most reviews focus on the molecular and pharmacological prospects of Nav1.5. This review is divided into three major subsections: (1) the review highlights the roles of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 in potentiating the progression of breast cancer, (2) focuses on the general connection between breast cancer and the immune system, and finally (3) the review emphasises the involvements of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 in the functionality of the immune system and the immunogenicity. Compared to the other subsections, section three is pretty unexploited; it would be interesting to study this subsection as it completes the triad.

1. Introduction

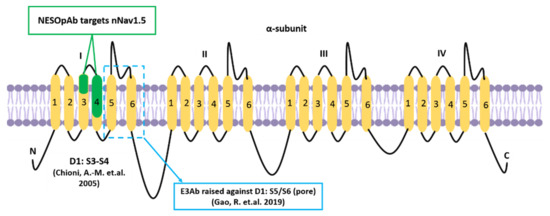

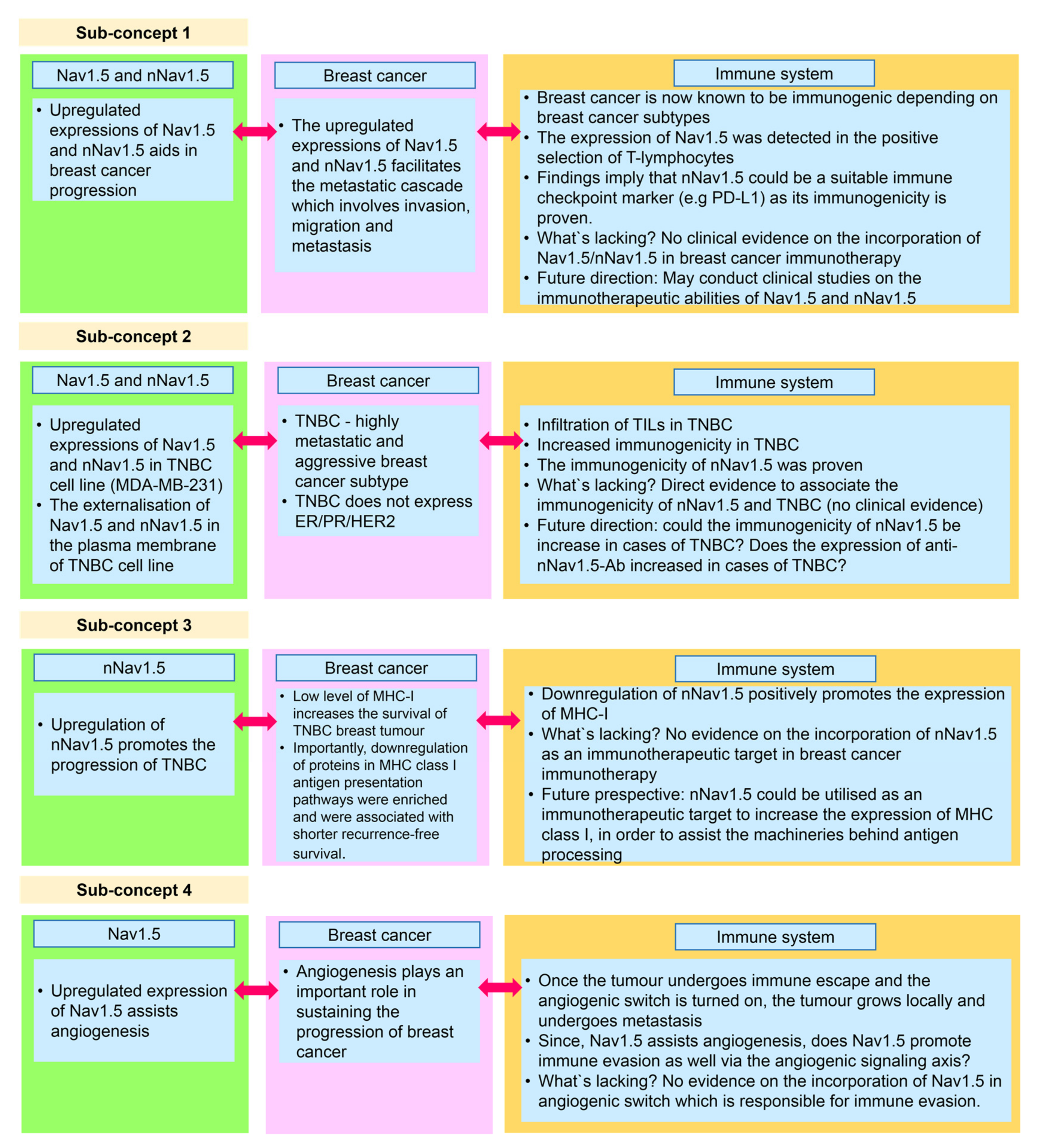

Nav1.5 (encoded by the SCN5A gene) is one of the nine members of the VGSC family. VGSCs are heteromeric membrane protein complexes. The VGSC structure is composed of one pore-forming α subunit and smaller β subunits. In total, there are nine α subunits (Nav1.1–Nav1.9) and four β subunits (β1–β4) [1] (Figure 1). In standard settings, VGSCs are responsible for the inward sodium current (INa) in excitable cells. As such, they induce fast depolarisation, thereby initiating a potential for the cells to react [2,3].

Figure 1.

The topology of a VGSC α subunit and β subunits. The figure was adapted and modified from Brackenbury and Isom [4] and recreated.

In terms of conformational change, VGSC transits between three distinct conformational states whenever there is a change in the membrane potential (depolarisation). These unique conformational figures are known as resting (closed), activated (open), and inactivated (closed) states [5]. Refractory is a term often associated with the functionality of VGSC. The term ‘refractory’ refers to a period of recovery from inactivation during which the channel is unable to open in response to depolarisation [6,7].

The Nav1.5 channel typically carries an inward sodium ion current (INa) which determines the sodium ion influx that functions to depolarise the membrane potential during the upstroke of the cardiac action potential [8]. Nav1.5 is important in regulating normal cardiac development, maintaining the heart‘s rhythm, and preventing various cardiac-related diseases [3]. The Nav1.5 channel is encoded by the SCN5A gene [9,10].

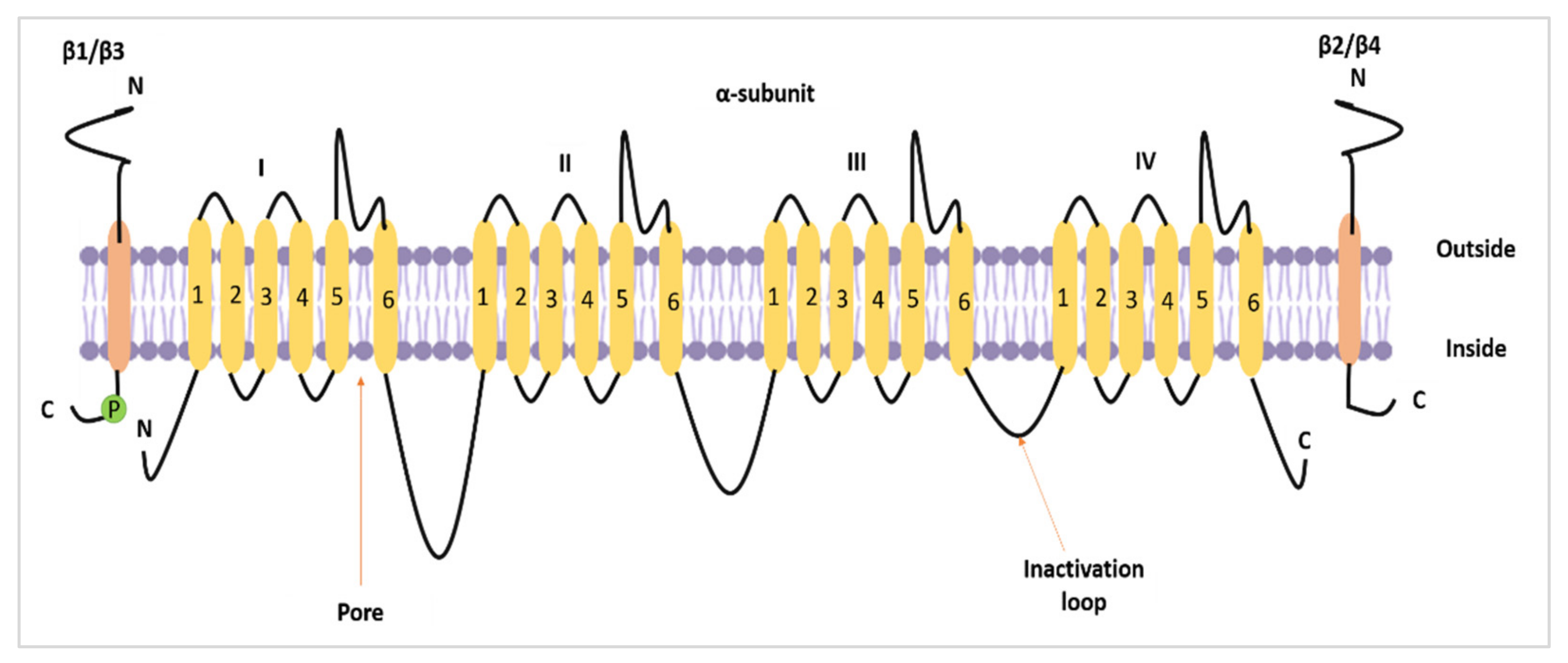

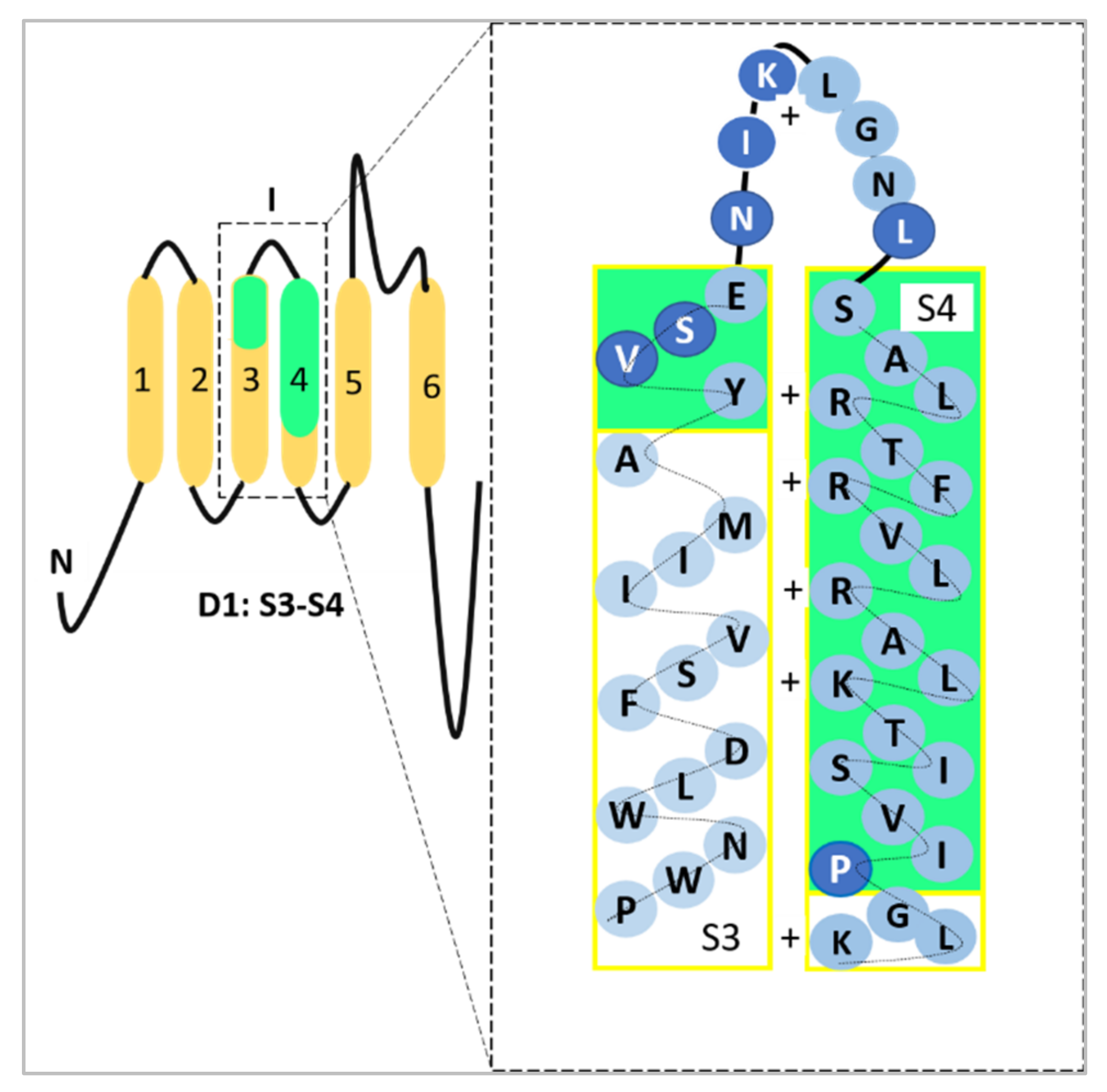

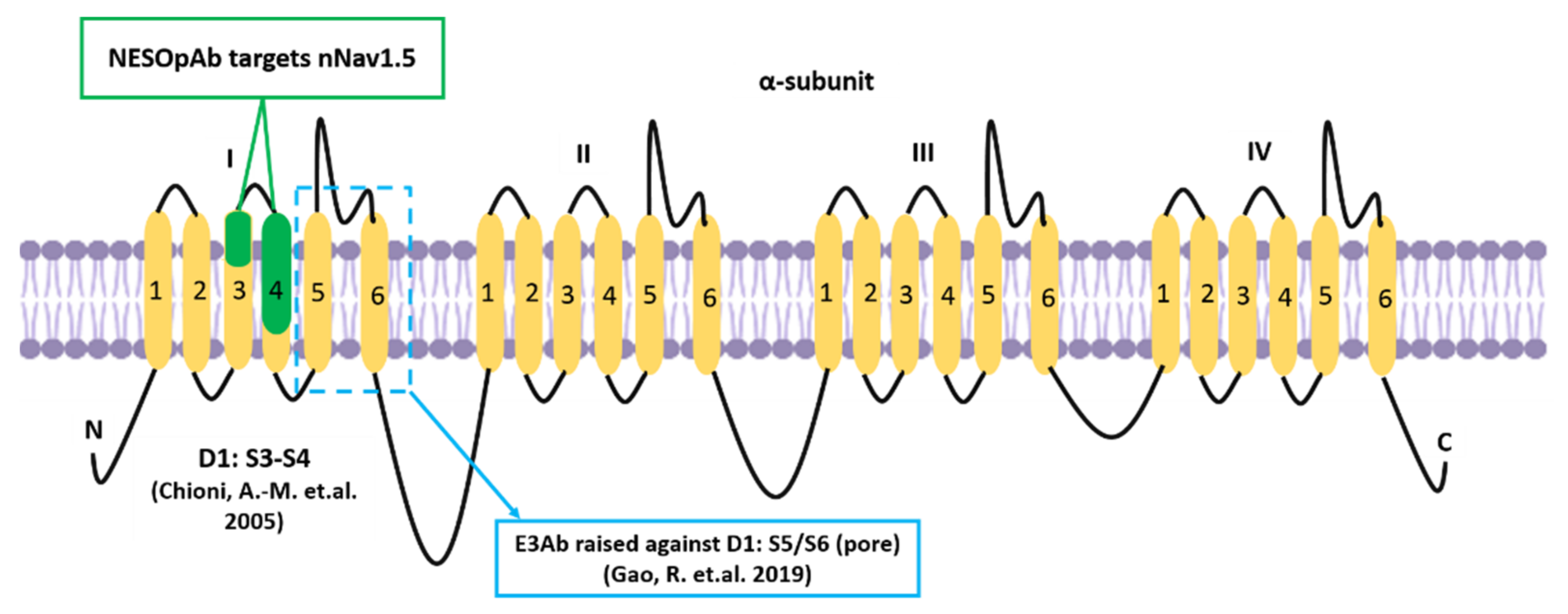

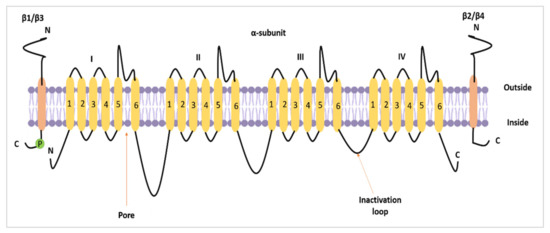

Alternative mRNA splicing allows further functional variation among α subunits of the VGSC family [11]. The neonatal isoform of Nav1.5, or neonatal Nav1.5 (nNav1.5), is produced as a result of VGSCα alternative splicing at domain 1: segment 3 (D1:S3) [12]. In breast cancer, the up-regulation of such an alternative splice-variant portrays onco-foetal gene expression since nNav1.5 would normally be expressed only during the foetal stage of human development [13,14]. The molecular differences between these two isoforms include the position of Nav1.5 (3′) and nNav1.5 (5′) on exon 6 and the seven amino acid changes in the sequence of nNav1.5 protein compared to Nav1.5 (Figure 2). The location of the alternative splicing is in the S3 and S4 regions of D1 in the protein, including the extracellular S3–S4 linker (Figure 2). The sequence differences between the two isoforms are located mainly in the C-terminal end of D1:S3 and the S3/S4 linker region of the channel, close to the four positively charged residues of the voltage-sensing S4 [12], as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A representation of the site where the D1:S3 splicing of Nav1.5 takes place. The seven amino acid difference has been highlighted in darker blue circles which could be observed in D1:S3–S4 and within the S3/S4 linker. The D1:S3–S4 sections have been highlighted in green to emphasise the exact location which represents nNav1.5. The four positively charged residues in S4 (voltage-sensor) were indicated as well. This image was adapted and modified from Onkal et al. [12] and recreated.

In short, the alternative splicing replaces a conserved negative aspartate residue in the ‘adult’ isoform with a positive lysine [12]. Due to the electrophysiological changes contributed from the Nav1.5 D1:S3 splicing, the charge reversal in nNav1.5 modifies the kinetics of the channel which results in the prolonged resultant current and thus causes an increased intracellular sodium ion (Na+) influx [12].

Aside from charge reversal and amino acid substitutions, there is one other feature that distinguishes Nav1.5 from nNav1.5. This feature is known as the ability to resist the suppressive effects of acidification. According to Onkal et al. [15], nNav1.5 showed more resistance against the suppressive effects of acidification than Nav1.5. Such resistance was associated with the difference in the charged amino acids of nNav1.5 and Nav1.5, which was mentioned earlier. It was postulated that the replacement of negatively charged aspartate to the positive lysine in the DI: S3–S4 region may decrease the effects of protonation on the activation of nNav1.5 [15]. Additionally, the residuals of acidic influence in S3–S4 may serve as crucial determinants of cationic effects pertaining to channel gating [16,17].

Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 have exhibited functional roles in assisting cancer progression, especially in breast cancer. The detection of these sodium channels, in association with breast cancer, was conducted using various modes of experiments such as in vitro [18], in vivo [19], and via the use of clinical samples [13,20]. In the midst of these oncological-based studies, another branch of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 began to expand. This branch focuses on the involvement of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 in the immune system’s functionality. Since there is a proven connection between breast cancer and the immune system [21], it would be interesting to review and discuss evidence supporting the connection between Nav1.5 (nNav1.5), breast cancer, and the immune system.

Therefore, in the current review, we have proposed and reviewed the triad encompassing Nav1.5, breast cancer, and the immune system (as depicted in the graphical abstract). To the best of our knowledge, there is no such review published to address the unique triad we propose in the present article. The available review papers only focus on the metastatic capacity of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 in potentiating breast cancer metastasis [22] and the pharmacological aspects of these sodium channels [23].

To obtain a clearer picture of the triad, we have subdivided the review into three major sections, which are (1) the roles of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 in potentiating the progression of breast cancer metastasis; (2) the general connection between breast cancer and the immune system; and (3) the involvements of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 in the functionality of the immune system and the immunogenicity of nNav1.5. Compared to the other subsections, section three is underexploited, and it would be interesting to study this particular subsection as it completes the triad between Nav1.5, breast cancer, and the immune system.

Finally, we aimed to reassemble the triad and highlight prospects that could serve as future perspectives to aid breast cancer immunotherapy.

3. The Connection between Breast Cancer and the Immune System

In 2011, the influential review by Hanahan and Weinberg [93] on the hallmarks of cancer was updated, whereby two more hallmarks of cancer were included. One of them was the evasion of immune destruction. The inclusion of the immunology perspective in understanding the progression of cancer is simply astounding and provides a more comprehensive interpretation of the disease.

The concept of metastasis is interconnected with the human immune system. During the metastatic cascade, cancer cells interact closely with the immune system and they influence each other, both within the tumour microenvironment and systemic circulation [94]. Thus, it can be said that the presence of migrating metastatic cancer cells may stimulate immune response within the human body [95,96,97]. The biomarkers present on these migrating cancer cells can be recognised by the immune cells and eventually trigger the immune system to produce antibodies to neutralise the expression of the biomarkers [95,98]. The crosstalk between cancer and immune cells contributes to another layer of complexity to our understanding of the formation of metastasis, but at the same time opens new therapeutic opportunities for patients such as cancer immunotherapy [96,99].

Breast cancer has traditionally been labelled as non-immunogenic or “cold”, meaning it does not provoke an immune response [21,100]. However, recent studies have proven otherwise. There are some astounding revelations that highlight the immunogenicity of breast cancer in various contexts [101,102]. One of those contexts is related to the heterogenicity of breast cancer. Breast cancer is made of a heterogeneous mixture of different molecular subtypes [21] and it has been reported that these subtypes contribute to the variation in the capabilities of inducing immune responses [103].

3.1. The Immunogenicity of Breast Cancer

A key insight is that the proportion of patients with tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) varies depending on the hormonal receptor profile of the tumour. Substantial lymphocytic infiltration promises a more favourable prognosis [104,105]. TILs, found in these tumours, signify that the immune cells have recognised the tumour cells, multiplied, and infiltrated them to prevent the progression of the tumour. Patients with hormone receptor-positive tumours are unlikely to have TILs in their tumours [106], whereas the triple-negative subtype has a robust tumour T-cell infiltrate compared to any other subtypes [105]. On the other hand, HER2-positive breast cancer has also been shown to have a large number of patients with significant TILs in their tumour. In HER2-positive breast cancer, the numbers of TILs can be further elevated via the presentation of trastuzumab treatment [106,107,108].

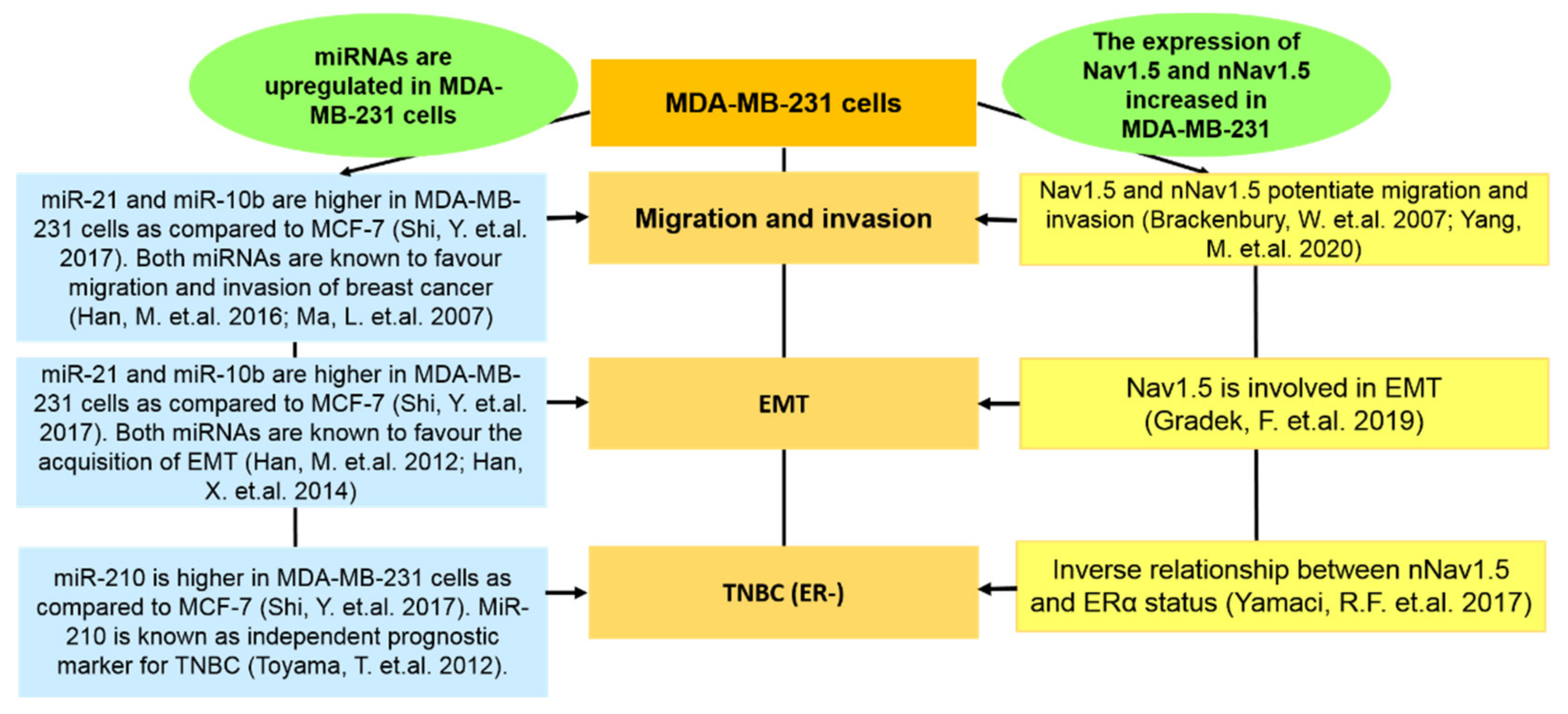

As discussed throughout the review, the MDA-MB-231 cell line is vastly utilised to demonstrate the role of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 in the context of breast cancer. Since the MDA-MB-231 cell line is a TNBC cell line, it is relevant for us to understand the basics of TNBC immunogenicity.

A recent study reported that TNBC cases with a low homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) exhibited a greater level of CD8+ T lymphocytes as compared to hormone receptor-positive cancer with a high HRD [102]. The study emphasised that the levels of HRD are inversely correlated with the immunogenicity in primary BRCA 1/2 breast cancers [102].

According to several sources, TNBC (highly metastatic) is more likely to be infiltrated with TILs as compared to other subsets. This is because TNBC is known to be immunogenic due to the presence of genetic instability, increased gene mutations, and chromosomal instability that may end up encoding peptide epitopes that appear foreign to the immune system, thus provoking it to induce an anti-tumour response [105,106,109,110]. In an article by Loi [105], the author suggested that if an immune response can be developed to prevent the progression of TNBC, which can be determined based on the presence of TILs at the time of diagnosis, the prognosis may be improved independently of the use of chemotherapy.

TNBC is also associated with another positive prognostic signature which is B cell-specific [111]. A gene expression study by Iglesia et al. [111] that focused on B cells indicated that the improved prognosis (metastasis-free survival) correlates well with B-cell gene expression, particularly in basal-like and HER2-enriched breast cancer subtypes. The presence of tumour-targeting B cells may elevate tumour inhibition via the production of antibodies (antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity) that are initiated by natural killer cells (NK cells). The presence of multiple different peptide antigens on TNBC may initiate the production of antibodies which attracts numerous innate immune cells. These innate immune cells are capable of presenting the antigens to be recognised by T cells. The activation of adaptive immune response can be further enhanced with the presence of cytokines produced by NK cells that are recruited via antibody Fc receptors [106].

Aside from the mentioned markers, there are several other examples, such as LINC00460. In a study by Cisneros-Villanueva et al. [112], the expression of LINC00460 modulates various immunogenic-related genes in BRCA cancer such as SFRP5, FOSL1, IFNK, CSF2, DUSP7, and IL1A. Interestingly, the expression of LINC00460 was increased in BL2 type TNBC, and it potentially regulates the WNT differentiation pathway. Via the activation of the WNT/β-catenin signalling axis, cancer cells are capable of retarding anti-tumour effects by excluding CD8+ T lymphocytes [113]. Interestingly, Nav1.5 was said to be involved in the progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma via the activation of the WNT/β-catenin signalling pathway [114].

The improvement in the stratification of breast cancer subtypes via gene profiling and high throughput imaging has definitely contributed to the separation of strongly and weakly immunogenic breast cancer subtypes [115].

3.2. The Role of the Immune System in the Progression and Elimination of Breast Tumours

The immune system plays an important role in both tumour progression and elimination. The interaction between the immune system and developing cancer cells, also known as immunoediting, consists of 3 phases: elimination, equilibrium, and escape [116,117]. During the early stages of breast tumour development, the acute inflammatory response results in the production of IL-12 and IFN-gamma, thus establishing a Th type 1 environment at the tumour site [118,119,120]. During this phase, dendritic cells began to mature, process the tumour-associated antigens, and migrate to the tumour-draining lymph nodes to present the foreign antigen to naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [121,122]. As a result, the immune response ultimately reduces the number of tumour cells and completes tumour rejection. However, the pressure it imposes leads to the selection of tumour cell variants that tend to escape detection by the immune response [93].

The process of immunoediting establishes a state of equilibrium (otherwise known as dormancy) [21]. As inflammation at the tumour site shifts from acute to chronic, the tumour microenvironment evolves to a Th type 2 profile, and the immune cells found in the microenvironment of breast cancer majorly consist of type 2 cells. Cytokines such as interleukin IL-10 and IL-6 are expressed by CD4+ Th2 cells in order to reduce the destruction of the immune system [123,124,125]. Innate immune cells and high levels of regulatory T-cells, on the other hand, secrete substances that both dampen the function of CD8 T cells and prevent their migration to the tumour site, thus producing only a small number of less active CD8 T cells that are available in order to induce tumour regression. The most unique aspect of breast cancer immunology is that breast carcinoma is able to influence the function of antigen-presenting cells (APC) by secreting substances that manipulate T cells to become type 2 immune cells rather than type 1 [21,106,116].

Immune escape mechanisms of breast cancer can be correlated with the characteristics of the subsets of the disease. In hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, a low level of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC class I) and absence of strong immunogenic tumour antigens contributes to the ability of the subset to survive unnoticed by the immune system. The presence of oestrogen (immunosuppressive) promotes tolerance of the weakly immunogenic cancer by polarising the immune system towards a type I immune response since most of the immune cells, including macrophages, T and B lymphocytes, and NK cells express ER [116].

In HER2-positive tumour cells, the presentation of MHC class I is inversely correlated with the expression of HER2 receptors [116,126]. In contrast, TNBC portrays a spectrum of MHC class I presentation and prominent tumour-associated antigen expression. Therefore, the concept of immune escape in TNBC focuses on the development of an immunosuppressed tumour microenvironment [127] that consists of immune checkpoint proteins such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) [128,129] and other components such as T regulatory cells [130] and myeloid-derived immunosuppressor cells (MDSCs) [131] which supports the progression of this metastatic subtype.

Abnormalities in the MHC class I may contribute to the survival of cancer cells [132]. Pertaining to VGSC, a neuron study showed that the blockade of action potentials with Tetrodotoxin resulted in a solid increase in the mRNA that encodes for MHC class I [133]. Such a finding implies the possibilities of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 in influencing the expression of MHC class I.

The prospects of immune escape and the angiogenic switch are closely connected as well. Tumour-associated macrophages and other immune cells tend to release pro-angiogenic factors that can stimulate the angiogenic switch that contributes to the progression of tumour mass. There are two models proposed to explain this phenomenon. The first model suggests that once the tumour undergoes immune escape and the angiogenic switch is turned on, the tumour grows locally and metastases [116]. Disseminated tumour cells (DTCs) are released at a later stage because DTCs do not have access to the bloodstream until the tumour has acquired its own set of blood vessels or vasculature. The second model, however, proposes the opposite. This model stipulates that the dissemination of cancer cells may take place at the beginning stage of cancer development [134] and continues throughout its progression. This implies that the role of immune escape is more essential than the role of the angiogenic switch because microscopic or smaller-sized tumours may have spawned across the circulation even before the angiogenic switch is activated [116].

5. Reassembling the Triad and Future Perspectives

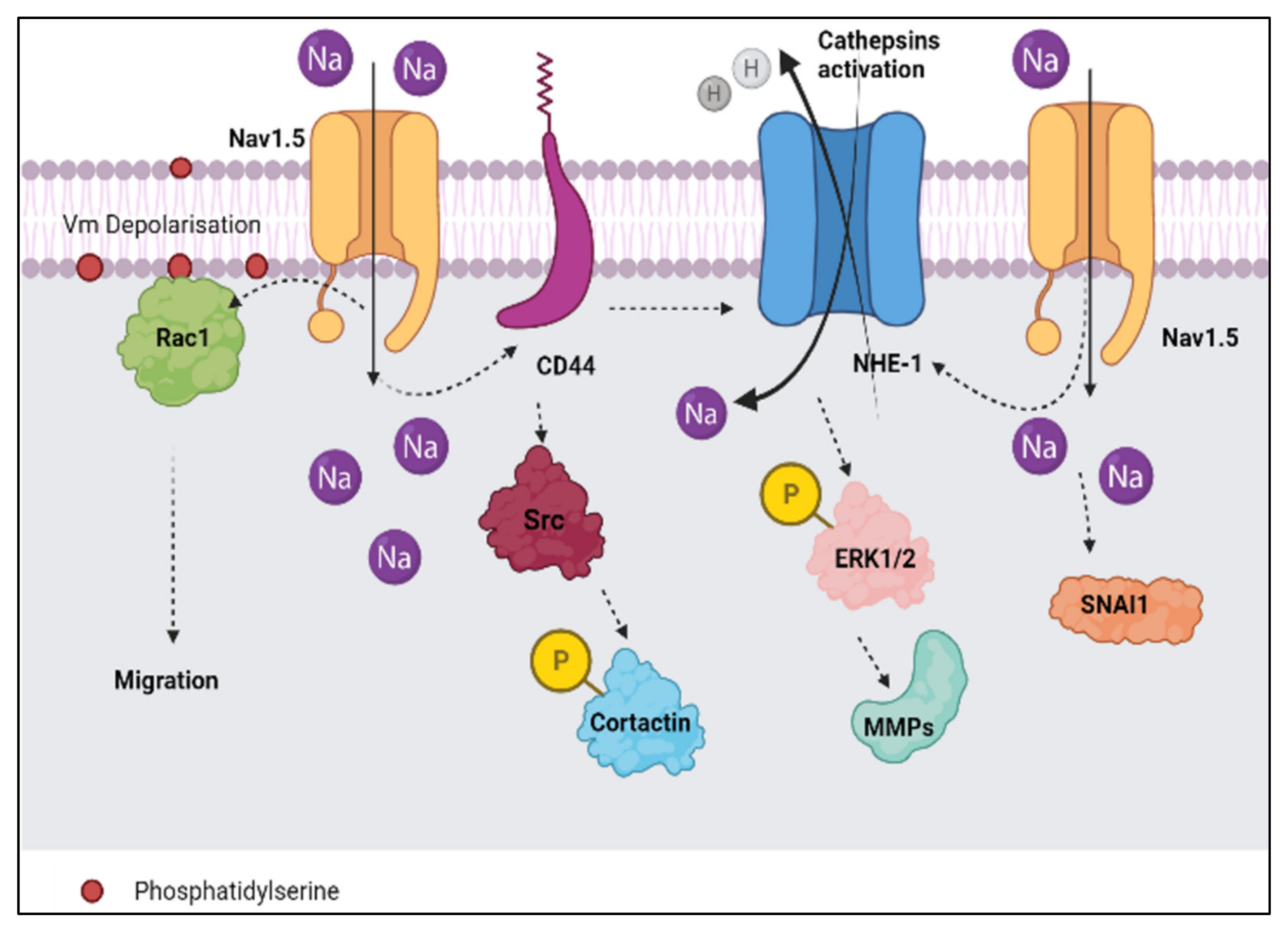

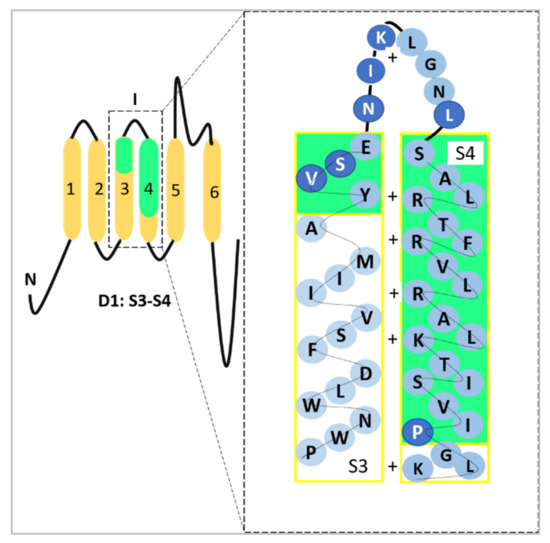

In the earlier subsections, we have analysed the triad in three dimensions, encompassing Nav1.5 (nNav1.5), breast cancer, and the immune system. Once the triad has been reassembled, we were able to derive several sub-concepts (Figure 8) that may play crucial parts in the overall concept of breast cancer immunotherapy.

Figure 8.

The summary of the sub-concepts that are derived from the triad.

5.1. Sub-Concept 1: Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 as Immunotherapeutic Targets in Combatting Breast Cancer

Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 have been known to potentiate the metastatic cascade which is necessary for breast cancer progression [18,49,70]. In terms of the immune system functionality, Nav1.5 plays an important role in the positive selection of CD4+ T-lymphocytes [140], whilst the immunogenicity of nNav1.5 validates its vulnerability towards immune responses [77]. In assembling this evidence, we propose that both Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 could play crucial parts in breast cancer immunotherapy. The positive selection of T-lymphocytes by Nav1.5 [140] could be used as a tool to increase the recruitment of CD4+ cells to reverse immunosuppression in breast cancer [169]. Since the immunogenicity of nNav1.5 is proven, the neonatal channel can be used as an immune checkpoint marker, such as in the case of PD-L1. Commercial production of antibodies against Nav1.5 [160] and nNav1.5 [161] could be incorporated in clinical studies to decipher the immunotherapeutic abilities of Nav1.5 and nNav.5 in combatting breast cancer progression.

Additionally, there is a lack of evidence to support the explanation surrounding the antigen processing machineries involving Nav1.5 and nNav1.5. This could also be an interesting prospect to study in the future.

5.2. Sub-Concept 2: Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 as Immunotherapeutic Targets in Combatting TNBC

The externalisation of Nav1.5 [64] in the plasma membrane of the TNBC cell line and the inverse relationship between ER status and nNav1.5 [13] have been demonstrated. It was emphasised that such externalisation contributes to the Na+ current, which is responsible for assisting breast cancer progression. This is definitely apt in the case of TNBC, as it does not express ER/PR/HER2, which increases the efficiency in the functional roles of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 in promoting breast cancer progression. The extensive use of MDA-MB-231 in demonstrating the actions of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 has sealed the connection of these sodium subunits and the progression of the TNBC subtype.

From an immunological perspective, TNBC is an immunogenic breast cancer subtype that exhibits increased infiltration of TILs [170]. However, there is no direct evidence that associates the natural immunogenicity of nNav1.5 and TNBC subtypes in clinical settings. Thus, the future perspectives here would be: (a) does the immunogenicity of nNav1.5 increase in the cases of TNBC and (b) does the level of anti-nNav1.5-Ab increase in the serum of TNBC breast cancer patients?

5.3. Sub-Concept 3: Blocking nNav1.5 to Increase MHC Class I Expression in Breast Cancer Immunotherapy for TNBC Patients

Currently, atezolizumab is provided for TNBC patients who expressed PD-L1 in their tumours. The prescription of atezolizumab highlights the incorporation of immunotherapy to assist conventional breast cancer treatments. In addition to infiltration of TILs, TNBC also possesses a low level of MHC class I proteins which is crucial for the survival of the subtype [171,172]. Since the downregulation of nNav1.5 rescues the expression of MHC class I [168], we believe that by targeting nNav1.5 using compatible immune checkpoint inhibitors, the progression of TNBC could be suppressed.

5.4. Sub-Concept 4: Role of Nav1.5 in Promoting Immune Evasion via Angiogenic Signalling Axis

The involvement of Nav1.5 in angiogenesis has been demonstrated by Andrikopoulos et al. [75]. Since there is an established ‘bridge’ connecting angiogenesis and immune evasion [173], we believe that it is possible that Nav1.5 (or nNav1.5) may modulate immune evasion by altering the angiogenic signalling axis.

Recently, Rajaratinam et al. [77] pointed out the upregulation of IL-6 and the significant positive correlation between anti-nNav1.5-Ab and IL-6 in the serum of breast cancer patients who did not receive treatment. This implies that the progression of metastasis is supported by the upregulation of IL-6 [77]. What is so unique about IL-6 is that it does not only promote breast cancer metastasis [174,175] and angiogenesis [176,177] but also contributes to immunosuppression [178]. Putting things into perspective, we believe that nNav1.5 might work along with immunosuppressive agents such as IL-6 and manipulate the angiogenic signalling axis in order to assist immune evasion in breast cancer.

Adopting the concept of immune evasion proposed by Hanahan and Weinberg [93] in their updated version of ‘Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation’, we believe that the potential of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 in evading the immune system remains underexploited. Numerous gaps remain unanswered when incorporating Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 into the notion of immune evasions pertaining to breast cancer and breast cancer immunotherapy, such as a) how does Nav1.5 (or nNav1.5) assist in immune evasion to rescue to the progression of breast cancer, b) does the expression of Nav1.5 influence angiogenesis, thus indirectly regulating immune evasion, and c) is there a link between nNav1.5 and Il-6 when it comes to immune evasion in breast cancer?

6. Limitation of the Review

As for the limitations of this review, we believe that there is a lack of information on the direct association between Nav1.5/nNav1.5 and breast cancer immunology. The lack of information may include the absence of investigation on the immunological pathways involved in the processing of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5. Additionally, there is a limited number of literature sources available on the in vivo investigations pertaining to nNav1.5 and the immunological areas which consist of MHC classes, macrophages, and regulatory T-cells under the context of nNav1.5.

7. Concluding Remarks

Throughout the review paper, we have discussed the various dimensions of the triad encompassing three main components which are Nav1.5 (nNav1.5), breast cancer, and the immune system. In a nutshell, the upregulation of Nav1.5, especially in its neonatal form, potentiates breast cancer metastasis. Since there is proven crosstalk between breast cancer metastasis and the immune system, the immunogenicity of nNav1.5 can be manipulated as a potential immunosurveillance marker to detect the progression of breast cancer metastasis. The involvement of Nav1.5 and its neonatal isoform in the immune system’s functionality is definitely a beneficial scope of study that requires more attention. Overall, the triad has contributed several valuable sub-concepts that could ultimately assist breast cancer immunotherapies involving Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 as their star casts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R., N.F.M., N.A.-A. and W.E.M.F.; methodology, H.R., N.F.M., N.A.-A. and W.E.M.F.; software (illustration), H.R. and W.E.M.F.; validation, N.F.M., N.A.-A. and W.E.M.F.; formal analysis, N.F.M., N.A.-A. and W.E.M.F.; data curation, H.R., N.F.M., N.A.-A. and W.E.M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R.; writing—review and editing, N.F.M., N.A.-A. and W.E.M.F.; supervision, N.F.M., N.A.-A. and W.E.M.F.; project administration, H.R. and W.E.M.F.; funding acquisition, W.E.M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review was funded by Universiti Sains Malaysia Research University Individual (RUI) grant (grant holder: Wan Ezumi Mohd Fuad, grant number 1001/PPSK/8012275).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleague, Ahmad Hafiz Murtadha for his valuable advice on the betterment of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brackenbury, W.J. Voltage-gated sodium channels and metastatic disease. Channels 2012, 6, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidmann, S. The effect of the cardiac membrane potential on the rapid availability of the sodium-carrying system. J. Physiol. 1955, 127, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veerman, C.C.; Wilde, A.A.; Lodder, E.M. The cardiac sodium channel gene SCN5A and its gene product NaV1.5: Role in physiology and pathophysiology. Gene 2015, 573, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brackenbury, W.J.; Isom, L.L. Na channel β subunits: Overachievers of the ion channel family. Front. Pharmacol. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.S.Y.; Kayani, K.; Whyte-Oshodi, D.; Whyte-Oshodi, A.; Nachiappan, N.; Gnanarajah, S.; Mohammed, R. Voltage-gated sodium channels as therapeutic targets for chronic pain. J. Pain Res. 2019, 12, 2709–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahern, C.A.; Payandeh, J.; Bosmans, F.; Chanda, B. The hitchhiker’s guide to the voltage-gated sodium channel galaxy. J. Gen. Physiol. 2016, 147, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catterall, W.A.; Wisedchaisri, G.; Zheng, N. The conformational cycle of a prototypical voltage-gated sodium channel. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utrilla, R.G.; Nieto-Marín, P.; Alfayate, S.; Tinaquero, D.; Matamoros, M.; Pérez-Hernández, M.; Sacristán, S.; Ondo, L.; De Andrés, R.; Díez-Guerra, F.J.; et al. Kir2. 1-Nav1.5 channel complexes are differently regulated than Kir2.1 and Nav1.5 channels alone. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

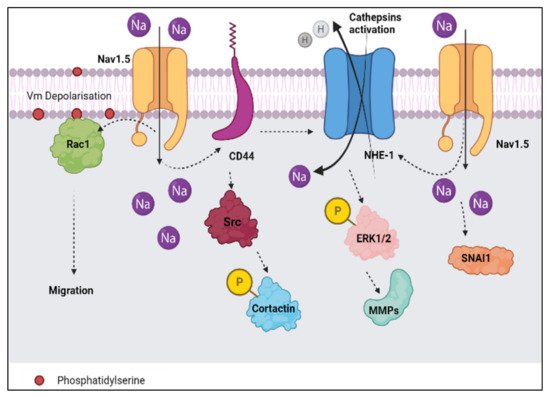

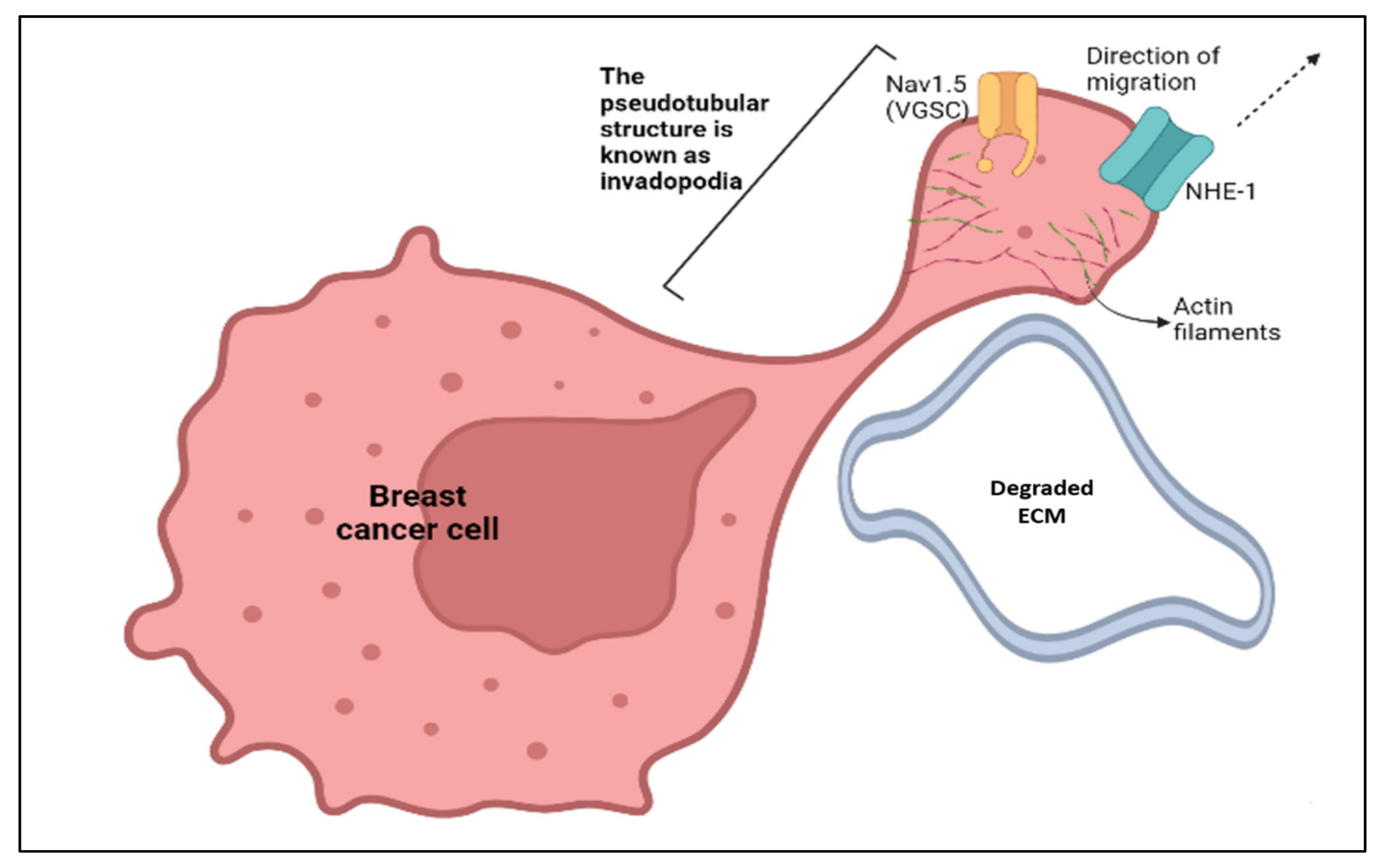

- Brisson, L.; Driffort, V.; Benoist, L.; Poet, M.; Counillon, L.; Antelmi, E.; Rubino, R.; Besson, P.; Labbal, F.; Chevalier, S.; et al. NaV1.5 Na+ channels allosterically regulate the NHE-1 exchanger and promote the activity of breast cancer cell invadopodia. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 4835–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Tan, H.; Sun, C.; Li, G. Dysfunctional Nav1.5 channels due to SCN5A mutations. Exp. Biol. Med. 2018, 243, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diss, J.K.J.; Fraser, S.P.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Voltage-gated Na+ channels: Multiplicity of expression, plasticity, functional implications and pathophysiological aspects. Eur. Biophys. J. 2004, 33, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onkal, R.; Mattis, J.H.; Fraser, S.P.; Diss, J.K.; Shao, D.; Okuse, K.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Alternative splicing of Nav1.5: An electrophysiological comparison of ‘neonatal’ and ‘adult’ isoforms and critical involvement of a lysine residue. J. Cell Physiol. 2008, 216, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

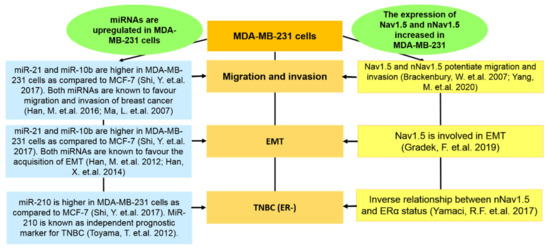

- Yamaci, R.F.; Fraser, S.P.; Battaloglu, E.; Kaya, H.; Erguler, K.; Foster, C.S.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Neonatal Nav1.5 protein expression in normal adult human tissues and breast cancer. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2017, 213, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Porath, I.; Thomson, M.W.; Carey, V.J.; Ge, R.; Bell, G.W.; Regev, A.; Weinberg, R.A. An embryonic stem cell–like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onkal, R.; Fraser, S.P.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Cationic modulation of voltage-gated sodium channel (Nav1.5): Neonatal versus adult splice variants—1. monovalent (H+) ions. Bioelectricity 2019, 1, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrikson, C.A.; Xue, T.; Dong, P.; Sang, D.; Marban, E.; Li, R.A. Identification of a surface charged residue in the S3–S4 linker of the pacemaker (HCN) channel that influences activation gating. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 13647–13654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, J.B.; Cha, A.; Latorre, R.; Rosenman, E.; Bezanilla, F. Deletion of the S3–S4 linker in the Shaker potassium channel reveals two quenching groups near the outside of S4. J. Gen. Physiol. 2000, 115, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackenbury, W.; Chioni, A.M.; Diss, J.K.J.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. The neonatal splice variant of Nav1.5 potentiates in vitro invasive behavior of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2007, 101, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.; Yang, M.; Millican-Slater, R.; Brackenbury, W.J. Nav1.5 regulates breast tumor growth and metastatic dissemination in vivo. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 32914–32929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S.P.; Diss, J.K.; Chioni, A.M.; Mycielska, M.E.; Pan, H.; Yamaci, R.F.; Pani, F.; Siwy, Z.; Krasowka, M.; Grzywna, Z.; et al. Voltage-gated sodium channel expression and potentiation of human breast cancer metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 5381–5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emens, L.A. Breast cancer immunotherapy: Facts and hopes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Wu, T.; Wu, W.; Chen, G.; Luo, X.; Jiang, L.; Tao, H.; Rong, M.; Kang, S.; Deng, M. The functional role of voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.5 in metastatic breast cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onkal, R.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Molecular pharmacology of voltage-gated sodium channel expression in metastatic disease: Clinical potential of neonatal Nav1.5 in breast cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 625, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GLOBOCAN 2020 Report by International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Malhotra, G.K.; Zhao, X.; Band, H.; Band, V. Histological, molecular and functional subtypes of breast cancers. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010, 10, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento, R.G.; Otoni, K.M. Histological and molecular classification of breast cancer: What do we know? Mastology 2020, 30, e20200024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørlie, T.; Perou, C.M.; Tibshirani, R.; Aas, T.; Geisler, S.; Johnsen, H.; Hastie, T.; Eisen, M.B.; Van de Rijn, M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10869–10874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørlie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Parker, J.; Hastie, T.; Marron, J.S.; Nobel, A.; Deng, S.; Johnsen, H.; Pesich, R.; Geisler, S.; et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8418–8423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Pegram, M. Research advances and new challenges in overcoming triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2021, 4, 517–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertucci, F.; Finetti, P.; Cervera, N.; Esterni, B.; Hermitte, F.; Viens, P.; Birnbaum, D. How basal are triple-negative breast cancers? Int. J. Cancer 2008, 123, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakha, E.A.; Elsheikh, S.E.; Aleskandarany, M.A.; Habashi, H.O.; Green, A.R.; Powe, D.G.; El-Sayed, M.E.; Benhasouna, A.; Brunet, J.S.; Akslen, L.A.; et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: Distinguishing between basal and nonbasal subtypes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 2302–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B.D.; Bauer, J.A.; Chen, X.; Sanders, M.E.; Chakravarthy, A.B.; Shyr, Y.; Pietenpol, J.A. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2750–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, B.D.; Jovanović, B.; Chen, X.I.; Estrada, M.V.; Johnson, K.N.; Shyr, Y.; Moses, H.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Pietenpol, J.A. Refinement of triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtypes: Implications for neoadjuvant chemotherapy selection. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.Y.; Jiang, Z.; Ben-David, Y.; Woodgett, J.R.; Zacksenhaus, E. Molecular stratification within triple-negative breast cancer subtypes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruijter, T.C.; Veeck, J.; De Hoon, J.P.; Van Engeland, M.; Tjan-Heijnen, V.C. Characteristics of triple-negative breast cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 137, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, S.; Besson, P.; Le Guennec, J.Y. Involvement of a novel fast inward sodium current in the invasion capacity of a breast cancer cell line. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2003, 1616, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isbilen, B.; Fraser, S.P.; Djamgoz, M.B. Docosahexaenoic acid (omega−3) blocks voltage-gated sodium channel activity and migration of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006, 38, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguy, A.; Hebert, T.E.; Nattel, S. Involvement of lipid rafts and caveolae in cardiac ion channel function. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 69, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, L.; Roger, S.; Bougnoux, P.; Le Guennec, J.Y.; Besson, P. Beneficial effects of omega-3 long-chain fatty acids in breast cancer and cardiovascular diseases: Voltage-gated sodium channels as a common feature? Biochimie 2011, 93, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanckaert, V.; Kerviel, V.; Lépinay, A.; Joubert-Durigneux, V.; Hondermarck, H.; Chénais, B. Docosahexaenoic acid inhibits the invasion of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through upregulation of cytokeratin-1. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 2649–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, N.N.; Huang, C.C. Interaction of integrin β1 with cytokeratin 1 in neuroblastoma NMB7 cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 1292–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, J.T.; Li, Y.; Mitchell, N.; Wilson, L.; Kim, H.; Tollefsbol, T.O. 2D difference gel electrophoresis analysis of different time points during the course of neoplastic transformation of human mammary epithelial cells. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andavan, B.; Shankar, G.; Lemmens-Gruber, R. Modulation of Nav 1.5 variants by src tyrosine kinase. Biophys. J. 2010, 98 (Suppl. 1), 310A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, M.A.; Ozpolat, B. Targeting of NaV1.5 channel in metastatic breast cancer models in vitro and in vivo mice as a novel therapy. In Proceedings of the ECCO: 2017 European Cancer Congress, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 27–30 January 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, A.L.; Evangelista, A.F.; Macedo, T.; Oliveira, R.; Scapulatempo-Neto, C.; Vieira, R.A.; Marques, M.M.C. Molecular characterization of breast cancer cell lines by clinical immunohistochemical markers. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 4708–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillet, L.; Roger, S.; Besson, P.; Lecaille, F.; Gore, J.; Bougnoux, P.; Lalmanach, G.; Le Guennec, J.Y. Voltage-gated sodium channel activity promotes cysteine cathepsin-dependent invasiveness and colony growth of human cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 8680–8691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, F.H.; Khajah, M.A.; Yang, M.; Brackenbury, W.J.; Luqmani, Y.A. Blockade of voltage-gated sodium channels inhibits invasion of endocrine-resistant breast cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 48, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Kozminski, D.J.; Wold, L.A.; Modak, R.; Calhoun, J.D.; Isom, L.L.; Brackenbury, W.J. Therapeutic potential for phenytoin: Targeting Nav1.5 sodium channels to reduce migration and invasion in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 134, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamarulzaman, N.S.; Dewadas, H.D.; Leow, C.Y.; Yaacob, N.S.; Mokhtar, N.F. The role of REST and HDAC2 in epigenetic dysregulation of Nav1.5 and nNav1.5 expression in breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2017, 17, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, S.P.; Hemsley, F.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester: Inhibition of metastatic cell behaviours via voltage-gated sodium channel in human breast cancer in vitro. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 71, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driffort, V.; Gillet, L.; Bon, E.; Marionneau-Lambot, S.; Oullier, T.; Joulin, V.; Collin, C.; Pagès, J.-C.; Jourdan, M.-L.; Chevalier, S.; et al. Ranolazine inhibits NaV1.5-mediated breast cancer cell invasiveness and lung colonization. Mol. Cancer 2014, 13, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, K.; Osaki, T.; Nakao, K.; Kawano, R.; Fujii, S.; Misawa, N.; Hayakawa, M.; Takeuchi, S. Electrophysiological measurement of ion channels on plasma/organelle membranes using an on-chip lipid bilayer system. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, M.B.; Evers, M.M.; Vos, M.A.; Bierhuizen, M.F. Biology of cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 expression. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 93, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhtar, N.F.; Sharuddin, N.A.; Wahab, N.C.; Dominguez, A.A.; Sarmiento, M.E.; Nor, N.M.; Yaccob, N.S. Evaluation of mouse polyclonal antibody against nNav1. 5 to recognize nNav1.5 protein in human breast cancer cells using fluorescence immunostaining. In Proceedings of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), Barcelona, Spain, 27 September–1 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrörs, B.; Boegel, S.; Albrecht, C.; Bukur, T.; Bukur, V.; Holtsträter, C.; Ritzel, C.; Manninen, K.; Tadmor, A.D.; Vormehr, M.; et al. Multi-omics characterization of the 4T1 murine mammary gland tumor model. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djamgoz, M.B.A.; Coombes, R.C.; Schwab, A. Ion transport and cancer: From initiation to metastasis. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2014, 369, 20130092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, S.P.; Ozerlat-Gunduz, I.; Brackenbury, W.J.; Fitzgerald, E.M.; Campbell, T.M.; Coombes, R.C.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Regulation of voltage-gated sodium channel expression in cancer: Hormones, growth factors and auto-regulation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2014, 369, 20130105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

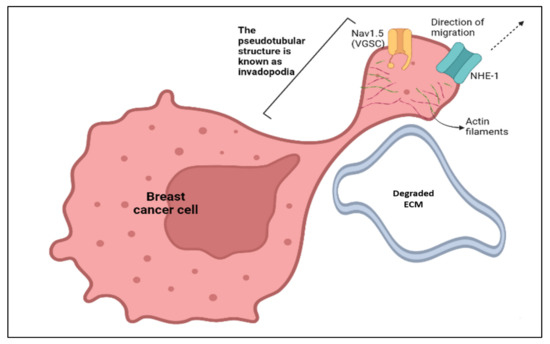

- Eddy, R.J.; Weidmann, M.D.; Sharma, V.P.; Condeelis, J.S. Tumor cell invadopodia: Invasive protrusions that orchestrate metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisson, L.; Gillet, L.; Calaghan, S.; Besson, P.; Le Guennec, J.-Y.; Roger, S.; Gore, J. NaV1.5 enhances breast cancer cell invasiveness by increasing NHE1-dependent H+ efflux in caveolae. Oncogene 2011, 30, 2070–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.; McFarlane, S.; Mulligan, K.; Gillespie, H.; Draffin, J.E.; Trimble, A.; Ouhtit, A.; Johnston, P.G.; Harkin, D.P.; McCormick, D.; et al. Cortactin underpins CD44-promoted invasion and adhesion of breast cancer cells to bone marrow endothelial cells. Oncogene 2006, 25, 6079–6091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, S.; McFarlane, C.; Montgomery, N.; Hill, A.; Waugh, D.J. CD44-mediated activation of α5β1-integrin, cortactin and paxillin signaling underpins adhesion of basal-like breast cancer cells to endothelium and fibronectin-enriched matrices. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 36762–36773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, P.; Driffort, V.; Bon, É.; Gradek, F.; Chevalier, S.; Roger, S. How do voltage-gated sodium channels enhance migration and invasiveness in cancer cells? Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2015, 1848, 2493–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Lin, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, Q. CD44 Targets Na+/H+ exchanger 1 to mediate MDA-MB-231 cells’ metastasis via the regulation of ERK1/2. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 916–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioni, A.M.; Shao, D.; Grose, R.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Protein kinase A and regulation of neonatal Nav1.5 expression in human breast cancer cells: Activity-dependent positive feedback and cellular migration. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradek, F.; Lopez-Charcas, O.; Chadet, S.; Poisson, L.; Ouldamer, L.; Goupille, C.; Jourdan, M.L.; Chevalier, S.; Moussata, D.; Besson, P. Sodium channel Nav1.5 controls epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and invasiveness in breast cancer cells through its regulation by the salt-inducible kinase-1. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20130105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Sarkissyan, M.; Vadgama, J.V. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and breast cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungefroren, H.; Witte, D.; Lehnert, H. The role of small GTPases of the Rho/Rac family in TGF-β-induced EMT and cell motility in cancer. Dev. Dyn. 2018, 247, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Chen, R.; Su, W.; Li, P.; Chen, S.; Chen, Z.; Chen, A.; Li, S.; Hu, C. IBP regulates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and the motility of breast cancer cells via Rac1, RhoA and Cdc42 signaling pathways. Oncogene 2014, 33, 3374–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parri, M.; Chiarugi, P. Rac and Rho GTPases in cancer cell motility control. Cell Commun. Signal. 2010, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; James, A.D.; Suman, R.; Kasprowicz, R.; Nelson, M.; O’Toole, P.J.; Brackenbury, W.J. Voltage-dependent activation of Rac1 by Nav1. 5 channels promotes cell migration. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 3950–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubriac, J.; Han, S.; Grahovac, J.; Smith, E.; Hosein, A.; Buchanan, M.; Basik, M.; Boucher, Y. The crosstalk between breast carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and cancer cells promotes RhoA-dependent invasion via IGF-1 and PAI-1. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 10375–10387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulong, C.; Fang, Y.J.; Gest, C.; Zhou, M.H.; Patte-Mensah, C.; Mensah-Nyagan, A.G.; Vannier, J.P.; Lu, H.; Soria, C.; Cazin, L.; et al. The small GTPase RhoA regulates the expression and function of the sodium channel Nav1. 5 in breast cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 44, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, C.D.; Vaske, C.J.; Schwartz, A.M.; Obias, V.; Frank, B.; Luu, T.; Sarvazyan, N.; Irby, R.; Strausberg, R.L.; Hales, T.G.; et al. Voltage-gated Na+ channel SCN5A is a key regulator of a gene transcriptional network that controls colon cancer invasion. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 6957–6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maishi, N.; Annan, D.A.; Kikuchi, H.; Hida, Y.; Hida, K. Tumor endothelial heterogeneity in cancer progression. Cancers 2019, 11, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulos, P.; Fraser, S.P.; Patterson, L.; Ahmad, Z.; Burcu, H.; Ottaviani, D.; Diss, J.K.J.; Box, C.; Eccles, S.A.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Angiogenic functions of voltage-gated Na+ channels in human endothelial cells: Modulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 16846–16860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, C.F.; Szot, C.S.; Wilson, T.D.; Akman, S.; Metheny-Barlow, L.J.; Robertson, J.L.; Freman, J.W.; Rylander, M.N. Cross-talk between endothelial and breast cancer cells regulates reciprocal expression of angiogenic factors in vitro. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 113, 1142–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaratinam, H.; Rasudin, N.S.; Al Astani, T.A.D.; Mokhtar, N.F.; Yahya, M.M.; Wan Zain, W.Z.; Asma-Abdullah, N.; Mohd Fuad, W.E. Breast cancer therapy affects the expression of antineonatal Nav1.5 antibodies in the serum of patients with breast cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulos, P.; Kieswich, J.; Harwood, S.M.; Baba, A.; Matsuda, T.; Barbeau, O.; Jones, K.; Eccles, S.A.; Yaqoob, M.M. Endothelial angiogenesis and barrier function in response to thrombin require Ca2+ influx through the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 18412–18428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastraioli, E.; Fraser, S.P.; Guzel, R.; Iorio, J.; Bencini, L.; Scarpi, E.; Messerini, L.; Villanacci, V.; Cerino, G.; Ghezzi, N.; et al. Neonatal Nav1. 5 protein expression in human colorectal cancer: Immunohistochemical characterization and clinical evaluation. Cancers 2021, 13, 3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.N.; Li, L.; Golovina, V.A.; Platoshyn, O.; Strauch, E.D.; Yuan, J.X.J.; Wang, J.Y. Ca2+-RhoA signaling pathway required for polyamine-dependent intestinal epithelial cell migration. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001, 280, C993–C1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodossiou, T.A.; Ali, M.; Grigalavicius, M.; Grallert, B.; Dillard, P.; Schink, K.O.; Olsen, C.E.; Wälchli, S.; Inderberg, E.M.; Kubin, A.; et al. Simultaneous defeat of MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 resistances by a hypericin PDT–tamoxifen hybrid therapy. NPJ Breast Cancer 2019, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Saxena, N.K.; Davidson, N.E.; Vertino, P.M. Restoration of tamoxifen sensitivity in estrogen receptor–negative breast cancer cells: Tamoxifen-bound reactivated ER recruits distinctive corepressor complexes. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 6370–6378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sakamoto, T.; Niiya, D.; Seiki, M. Targeting the Warburg effect that arises in tumor cells expressing membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 14691–14704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatenby, R.A.; Gillies, R.J. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzel, R.M.; Ogmen, K.; Ilieva, K.M.; Fraser, S.P.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Colorectal cancer invasiveness in vitro: Predominant contribution of neonatal Nav1. 5 under normoxia and hypoxia. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 6582–6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiden, C.; Ungefroren, H. The ratio of RAC1B to RAC1 expression in breast cancer cell lines as a determinant of epithelial/mesenchymal differentiation and migratory potential. Cells 2021, 10, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Ye, P.; Long, X. Differential expression profiles of the transcriptome in breast cancer cell lines revealed by next generation sequencing. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 804–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Wang, F.; Gu, Y.; Pei, X.; Guo, G.; Yu, C.; Li, L.; Zhu, M.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Y. MicroRNA-21 induces breast cancer cell invasion and migration by suppressing smad7 via EGF and TGF-β pathways. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Bi, X.; Bao, J.; Zeng, N.; Zhu, Z.; Mo, Z.; Wu, C.; Chen, X. MiR-21 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression in third-sphere forming breast cancer stem cell-like cells. Cancer Sci. 2012, 103, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Teruya-Feldstein, J.; Weinberg, R.A. Tumour invasion and metastasis initiated by microRNA-10b in breast cancer. Nature 2007, 449, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Yan, S.; Weijie, Z.; Feng, W.; Liuxing, W.; Mengquan, L.; Qingxia, F. Critical role of miR-10b in transforming growth factor-β1-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2014, 21, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, T.; Kondo, N.; Endo, Y.; Sugiura, H.; Yoshimoto, N.; Iwasa, M.; Takahashi, S.; Fujii, Y.; Yamashita, H. High expression of microRNA-210 is an independent factor indicating a poor prognosis in Japanese triple-negative breast cancer patients. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 42, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell Press 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinay, D.S.; Ryan, E.P.; Pawelec, G.; Talib, W.H.; Stagg, J.; Elkord, E.; Lichtor, T.; Decker, W.K.; Whelan, R.L.; Kumara, H.S.; et al. Immune evasion in cancer: Mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 35, S185–S198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burks, J.; Reed, R.E.; Desai, S.D. Free ISG15 triggers an antitumor immune response against breast cancer: A new perspective. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 7221–7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomberg, O.S.; Spagnuolo, L.; De Visser, K.E. Immune regulation of metastasis: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic opportunities. Dis. Model. Mech. 2018, 11, dmm036236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Nam, J.S. The force awakens: Metastatic dormant cancer cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Singh, M.; Santos, G.S.; Guerlavais, V.; Carvajal, L.A.; Aivado, M.; Zhan, Y.; Oliveira, M.M.; Westerberg, L.S.; Annis, D.A.; et al. Pharmacologic activation of p53 triggers viral mimicry response thereby abolishing tumor immune evasion and promoting antitumor immunity. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 3090–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.S.; June, C.H.; Langer, R.; Mitchell, M.J. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti-Mays, M.E.; Balko, J.M.; Gameiro, S.R.; Bear, H.D.; Prabhakaran, S.; Fukui, J.; Disis, M.L.; Nanda, R.; Gulley, J.L.; Kalinsky, K.; et al. If we build it they will come: Targeting the immune response to breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2019, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.D.; Chou, J.A.; Black, M.A.; Chifman, J.; Alistar, A.; Putti, T.; Zhou, X.; Bedognetti, D.; Hendrickx, W.; Pullikuth, A.; et al. Immunogenic subtypes of breast cancer delineated by gene classifiers of immune responsiveness. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016, 4, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraya, A.A.; Maxwell, K.N.; Wubbenhorst, B.; Wenz, B.M.; Pluta, J.; Rech, A.J.; Dorfman, L.M.; Lunceford, N.; Barrett, A.; Mitra, N.; et al. Genomic signatures predict the immunogenicity of BRCA-deficient breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 4363–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerl, D.; Smid, M.; Timmermans, A.M.; Sleijfer, S.; Martens, J.W.M.; Debets, R. Breast cancer genomics and immuno-oncological markers to guide immune therapies. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 52, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, S.M.; Paish, E.C.; Powe, D.G.; Macmillan, R.D.; Grainge, M.J.; Lee, A.H.; Ellis, I.O.; Green, A.R. Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes predict clinical outcome in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 1949–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, S. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, breast cancer subtypes and therapeutic efficacy. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e24720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disis, M.L.; Stanton, S.E. Triple-negative breast cancer: Immune modulation as the new treatment paradigm. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2015, 35, e25–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, H.; Horii, R.; Ito, Y.; Iwase, T.; Ohno, S.; Akiyama, F. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes affect the efficacy of Trastuzumab-based treatment in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2018, 25, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasniqi, E.; Barchiesi, G.; Pizzuti, L.; Mazzotta, M.; Venuti, A.; Maugeri-Saccà, M.; Sanguineti, G.; Massimiani, G.; Sergi, D.; Carpano, S.; et al. Immunotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: State of the art and future perspectives. J. Hematol. Oncol 2019, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budczies, J.; Bockmayr, M.; Denkert, C.; Klauschen, F.; Lennerz, J.K.; Györffy, B.; Dietel, M.; Loibl, S.; Weichert, W.; Stenzinger, A. Classical pathology and mutational load of breast cancer–integration of two worlds. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2015, 1, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, S.; Cibulskis, K.; Rangel-Escareño, C.; Brown, K.K.; Carter, S.L.; Frederick, A.M.; Lawrence, M.S.; Sivachenko, A.Y.; Sougnez, C.; Zou, L.; et al. Sequence analysis of mutations and translocations across breast cancer subtypes. Nature 2012, 486, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesia, M.D.; Vincent, B.G.; Parker, J.S.; Hoadley, K.A.; Carey, L.A.; Perou, C.M.; Serody, J.S. Prognostic B-cell signatures using mRNA-seq in patients with subtype-specific breast and ovarian Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 3818–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Villanueva, M.; Hidalgo-Pérez, L.; Cedro-Tanda, A.; Peña-Luna, M.; Mancera-Rodríguez, M.A.; Hurtado-Cordova, E.; Rivera-Salgado, I.; Martínez-Aguirre, A.; Jiménez-Morales, S.; Alfaro-Ruiz, L.A.; et al. LINC00460 is a dual biomarker that acts as a predictor for increased prognosis in basal-like breast cancer and potentially regulates immunogenic and differentiation-related genes. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Tanegashima, T.; Sato, E.; Irie, T.; Sai, A.; Itahashi, K.; Kumagai, S.; Tada, Y.; Togashi, Y.; Koyama, S.; et al. Highly immunogenic cancer cells require activation of the WNT Pathway for immunological escape. Sci. Immunol. 2021, 6, eabc6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Dai, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, Y. Knockdown of Nav1. 5 inhibits cell proliferation, migration and invasion via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2020, 52, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, J.P.; Derakhshandeh, R.; Jones, L.; Webb, T.J. Mechanisms of immune evasion in breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhoul, I.; Atiq, M.; Alwbari, A.; Kieber-Emmons, T. Breast cancer immunotherapy: An update. Breast Cancer Basic Clin. Res. 2018, 12, 1178223418774802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, D.; Gubin, M.M.; Schreiber, R.D.; Smyth, M.J. New insights into cancer immunoediting and its three component phases—Elimination, equilibrium and escape. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2014, 27, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, J.; Ge, S.; Chen, C.; Li, S.; Wu, X.; Feng, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, D. Saikosaponin A inhibits breast cancer by regulating Th1/Th2 balance. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgovanovic, D.; Song, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Roles of IFN-γ in tumor progression and regression: A review. Biomark. Res. 2020, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Jasinska, J.; Breiteneder, H.; Kundi, M.; Pehamberger, H.; Scheiner, O.; Zielinski, C.C.; Wiedermann, U. Delayed tumor onset and reduced tumor growth progression after immunization with a Her-2/neu multi-peptide vaccine and IL-12 in c-neu transgenic mice. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2007, 106, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiuz, R.; Brousse, C.; Ambrosini, M.; Cancel, J.C.; Bessou, G.; Mussard, J.; Sanlaville, A.; Caux, C.; Bendriss-Vermare, N.; Valladeau-Guilemond, J.; et al. Type 1 conventional dendritic cells and interferons are required for spontaneous CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell protective responses to breast cancer. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2021, 10, e1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidhardt-Berard, E.M.; Berard, F.; Banchereau, J.; Palucka, A.K. Dendritic cells loaded with killed breast cancer cells induce differentiation of tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Breast Cancer Res. 2004, 6, R322–R328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomes, S.M.; Kannan, Y.; Pelly, V.S.; Entwistle, L.J.; Guidi, R.; Perez-Lloret, J.; Nikolov, N.; Müller, W.; Wilson, M.S. CD4+ Th2 cells are directly regulated by IL-10 during allergic airway inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, M.; Anguita, J.; Nakamura, T.; Fikrig, E.; Flavell, R.A. Interleukin (IL)-6 directs the differentiation of IL-4–producing CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 185, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, S.; Rincón, M. The two faces of IL-6 on Th1/Th2 differentiation. Mol. Immunol. 2002, 39, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Song, I.H.; Park, I.A.; Heo, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-A.; Ahn, J.-H.; Gong, G. Differential expression of major histocompatibility complex class I in subtypes of breast cancer is associated with estrogen receptor and interferon signaling. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 30119–30132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, T.J.; Christenson, J.L.; Greene, L.I.; O’Neill, K.I.; Williams, M.M.; Gordon, M.A.; Nemkov, T.; D’Alessandro, A.; Degala, G.D.; Shin, J.; et al. Reversal of triple-negative breast cancer EMT by miR-200c decreases tryptophan catabolism and a program of immunosuppression. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, S.; Dushyanthen, S.; Beavis, P.A.; Salgado, R.; Denkert, C.; Savas, P.; Combs, S.; Rimm, D.L.; Giltnane, J.M.; Estrada, M.V.; et al. RAS/MAPK activation is associated with reduced tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer: Therapeutic cooperation between MEK and PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Du, C.; Yuan, M.; Fu, P.; He, Q.; Yang, B.; Cao, J. PD-1/PD-L1 counterattack alliance: Multiple strategies for treating triple-negative breast cancer. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 1762–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plitas, G.; Konopacki, C.; Wu, K.; Bos, P.D.; Morrow, M.; Putintseva, E.V.; Chudakov, D.M.; Rudensky, A.Y. Regulatory T cells exhibit distinct features in human breast cancer. Immunity 2016, 45, 1122–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Coloma, C.; Santaballa, A.; Sanmartín, E.; Calvo, D.; García, A.; Hervás, D.; Cordon, L.; Quintas, G.; Ripoll, F.; Panadero, J.; et al. Immunosuppressive profiles in liquid biopsy at diagnosis predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 139, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, F.; Aptsiauri, N. Cancer immune escape: MHC expression in primary tumours versus metastases. Immunology 2019, 158, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, H.; Schmidt, H.; Cavalie, A.; Jenne, D.; Wekerle, H. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I gene expression in single neurons of the central nervous system: Differential regulation by interferon (IFN)-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 185, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartkopf, A.D.; Brucker, S.Y.; Taran, F.A.; Harbeck, N.; Von Au, A.; Naume, B.; Pierga, J.Y.; Hoffmann, O.; Beckmann, M.W.; Rydén, L.; et al. Disseminated tumour cells from the bone marrow of early breast cancer patients: Results from an international pooled analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 154, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

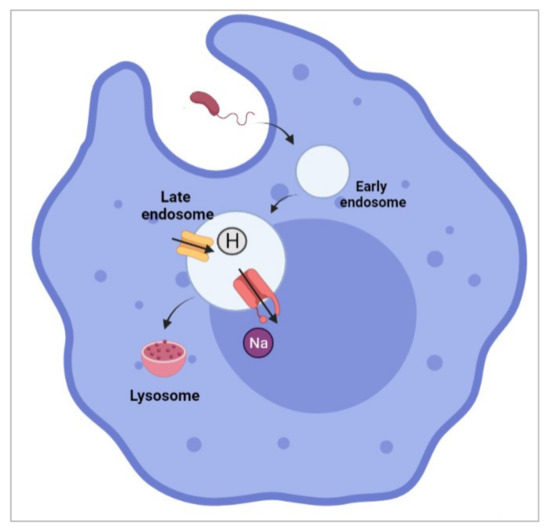

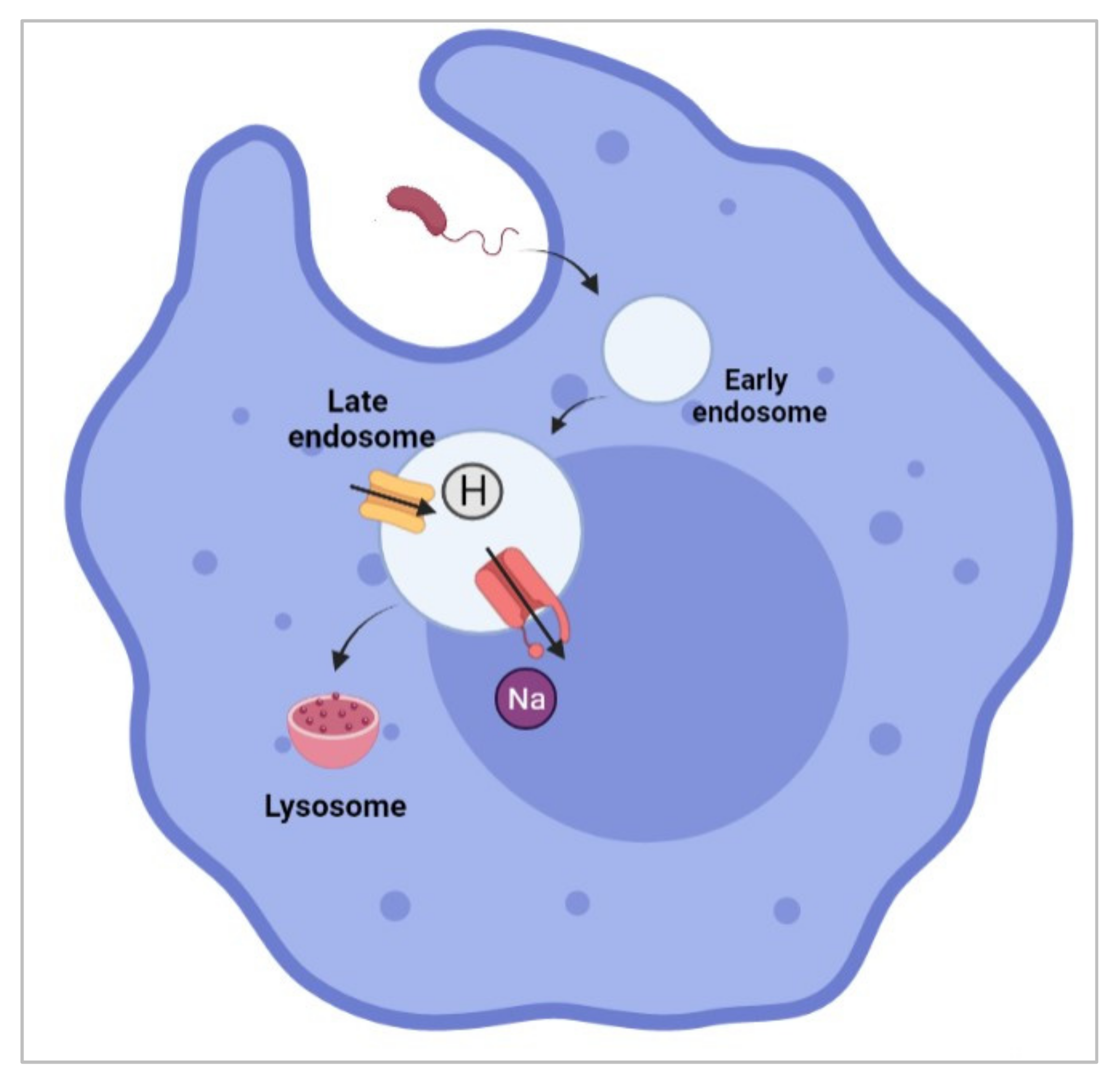

- Carrithers, M.D.; Dib-Hajj, S.; Carrithers, L.M.; Tokmoulina, G.; Pypaert, M.; Jonas, E.A.; Waxman, S.G. Expression of the voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.5 in the macrophage late endosome regulates endosomal acidification. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 7822–7832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrithers, L.M.; Hulseberg, P.; Sandor, M.; Carrithers, M.D. The human macrophage sodium channel NaV1.5 regulates mycobacteria processing through organelle polarization and localized calcium oscillations. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 63, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, J.A.; Newcombe, J.; Waxman, S.G. Nav1.5 sodium channels in macrophages in multiple sclerosis lesions. Mult. Scler. J. 2013, 19, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Kainz, D.; Khan, F.; Lee, C.; Carrithers, M.D. Human macrophage SCN5A activates an innate immune signaling pathway for antiviral host defense. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 35326–35340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieczorek, M.; Abualrous, E.T.; Sticht, J.; Álvaro-Benito, M.; Stolzenberg, S.; Noe, F.; Freund, C. Major Histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II proteins: Conformational plasticity in antigen presentation. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.L.; Donermeyer, D.L.; Allen, P.M. A Voltage-gated sodium channel is essential for the positive selection of CD4+ T Cells. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S.P.; Diss, J.K.; Lloyd, L.J.; Pani, F.; Chioni, A.M.; George, A.J.T.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. T-lymphocyte invasiveness: Control by voltage-gated Na+ channel activity. FEBS Lett. 2004, 569, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáspár, R., Jr.; Krasznai, Z.; Márián, T.; Trón, L.; Recchioni, R.; Falasca, M.; Moroni, F.; Pieri, C.; Damjanovich, S. Bretylium-induced voltage-gated sodium current in human lymphocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Mol. Cell Res. 1992, 1137, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieri, C.; Recchioni, R.; Moroni, F.; Balkay, L.; Márián, T.; Trón, L.; Damjanovich, S. Ligand and voltage gated sodium channels may regulate electrogenic pump activity in human, mouse and rat lymphocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989, 160, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Liang, S.; Jiang, F.; Xu, J.; Zhu, W.; Qian, W.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, J.; Niu, L.; et al. 2003–2013, a valuable study: Autologous tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cell immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells improves survival in stage IV breast cancer. Immunol. Lett. 2017, 183, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, K.; Guan, X.-X.; Li, Y.-Q.; Zhao, J.-J.; Li, J.-J.; Qiu, H.-J.; Weng, D.-S.; Wang, Q.-J.; Liu, Q.; Huang, L.-X.; et al. Clinical activity of adjuvant cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy in patients with post-mastectomy triple-negative breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 3003–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, L.J.; Weisdorf, D.J.; DeFor, T.E.; Vesole, D.H.; Repka, T.L.; Blazar, B.R.; Burger, S.R.; Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A.; Keever-Taylor, C.A.; Zhang, M.-J.; et al. IL-2-based immunotherapy after autologous transplantation for lymphoma and breast cancer induces immune activation and cytokine release: A phase I/II trial. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003, 32, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arab, A.; Behravan, J.; Razazan, A.; Gholizadeh, Z.; Nikpoor, A.R.; Barati, N.; Mosaffa, F.; Badiee, A.; Jaafari, M.R. A nano-liposome vaccine carrying E75, a HER-2/neu-derived peptide, exhibits significant antitumour activity in mice. J. Drug Target. 2018, 26, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Di, L.; Song, G.; Yu, J.; Jia, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, H.; Liang, X.; Che, L.; et al. Selections of appropriate regimen of high-dose chemotherapy combined with adoptive cellular therapy with dendritic and cytokine-induced killer cells improved progression-free and overall survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: Reargument of such contentious therapeutic preferences. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2013, 15, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmieciak, M.; Basu, D.; Payne, K.K.; Toor, A.; Yacoub, A.; Wang, X.-Y.; Smith, L.; Bear, H.D.; Manjili, M.H. Activated NKT Cells and NK Cells render T cells resistant to myeloid-derived suppressor cells and result in an effective adoptive cellular therapy against breast cancer in the FVBN202 transgenic mouse. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Mardiana, S.; House, I.G.; Sek, K.; Henderson, M.A.; Giuffrida, L.; Chen, A.X.; Todd, K.L.; Petley, E.V.; Chan, J.D.; et al. Adoptive cellular therapy with T cells expressing the dendritic cell growth factor Flt3L drives epitope spreading and antitumor immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Miao, L.; Liu, Q.; Musetti, S.; Li, J.; Huang, L. Combination immunotherapy of MUC1 mRNA nano-vaccine and CTLA-4 blockade effectively inhibits growth of triple negative breast cancer. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, E.; Savas, P.; Policheni, A.N.; Darcy, P.K.; Vaillant, F.; Mintoff, C.P.; Dushyanthen, S.; Mansour, M.; Pang, J.-M.B.; Fox, S.B.; et al. Combined immune checkpoint blockade as a therapeutic strategy for BRCA1-mutated breast cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Niu, Z.; Hou, B.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, H. Enhancing triple negative breast cancer immunotherapy by ICG-templated self-assembly of paclitaxel nanoparticles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1906605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahavi, D.; Weiner, L. Monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy. Antibodies 2020, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.M.; Carroll, E.; Nanda, R. Atezolizumab for the treatment of breast cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2020, 20, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, M.T.; Lenkiewicz, E.; Malasi, S.; Basu, A.; Yearley, J.H.; Annamalai, L.; McCullough, A.E.; Kosiorek, H.E.; Narang, P.; Wilson Sayres, M.A.; et al. The association of genomic lesions and PD-1/PD-L1 expression in resected triple-negative breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2018, 20, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Lu, W.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J. Immunotherapeutic interventions of triple negative breast cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA Approves Atezolizumab for PD-L1 Positive Unresectable Locally Advanced or Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2019/atezolizumab-triple-negative-breast-cancer-fda-approval (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Mavratzas, A.; Seitz, J.; Smetanay, K.; Schneeweiss, A.; Jäger, D.; Fremd, C. Atezolizumab for use in PD-L1-positive unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Future Oncol. 2020, 16, 4439–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Cao, T.; Chen, H.; Cai, J.; Lei, M.; Wang, Z. Nav1.5-E3 antibody inhibits cancer progression. Transl. Cancer Res. 2019, 8, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioni, A.-M.; Fraser, S.P.; Pani, F.; Foran, P.; Wilkin, G.P.; Diss, J.K.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. A novel polyclonal antibody specific for the Nav1.5 voltage-gated Na+ channel ‘neonatal’ splice form. J. Neurosci. Methods 2005, 147, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.Z.; Zeng, F.; Lei, M.; Li, J.; Gao, B.; Xiong, C.; Sivaprasadarao, A.; Beech, D.J. Generation of functional ion-channel tools by E3 targeting. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izdebska, M.; Zielińska, W.; Krajewski, A.; Hałas-Wiśniewska, M.; Mikołajczyk, K.; Gagat, M.; Grzanka, A. Downregulation of MMP-9 enhances the anti-migratory effect of cyclophosphamide in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Xu, L.; Ye, M.; Liao, M.; Du, H.; Chen, H. Formononetin inhibits migration and invasion of MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 breast cancer cells by suppressing MMP-2 and MMP-9 through PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Horm. Metab. Res. 2014, 46, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Wang, J.; Shen, Y.; Lei, M.; Wang, Z. Functional expression of voltage-gated sodium channels Nav1. 5 in human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2009, 29, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, S.P.; Onkal, R.; Theys, M.; Bosmans, F.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Neonatal NaV1.5: Pharmacological distinctiveness of a cancer-related voltage-gated sodium channel splice variant. Br. J. Pharmacol. accepted; epub ahead of print. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Pestka, S.; Jubin, R.G.; Lyu, Y.L.; Tsai, Y.C.; Liu, L.F. Chemotherapeutics and radiation stimulate MHC class I expression through elevated interferon-beta signaling in breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtadha, A.H.; Azahar, I.I.; Sharudin, N.A.; Has, A.T.; Mokhtar, N.F. Influence of nNav1. 5 on MHC class I expression in breast cancer. J. Biosci. 2021, 46, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Liao, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, D.; He, C.; Chen, F.; Yang, L.; Wu, W.; Chen, J.; Lin, L.; et al. Blocking the recruitment of naive CD4+ T Cells reverses immunosuppression in breast cancer. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomioka, N.; Azuma, M.; Ikarashi, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Sato, M.; Watanabe, K.I.; Yamashiro, K.; Takahashi, M. The therapeutic candidate for immune checkpoint inhibitors elucidated by the status of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). Breast Cancer 2018, 25, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusenbery, A.C.; Maniaci, J.L.; Hillerson, N.D.; Dill, E.A.; Bullock, T.N.; Mills, A.M. MHC Class I Loss in triple-negative breast cancer: A potential barrier to PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2021, 45, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.H.; Hood, B.L.; Beck, H.C.; Conrads, T.P.; Ditzel, H.J. Leth-Larsen, R. Downregulation of antigen presentation-associated pathway proteins is linked to poor outcome in triple-negative breast cancer patient tumors. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1305531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schito, L. Bridging angiogenesis and immune evasion in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2018, 315, R1072–R1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.-Y.; Wei, X.-H.; Li, S.-J.; Liu, Y.; Hu, H.-L.; Li, Z.-Z.; Kuang, X.-H.; Wang, L.; Shi, X.; Yuan, S.-T.; et al. Adipocyte-derived IL-6 and leptin promote breast cancer metastasis via upregulation of lysyl hydroxylase-2 expression. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Yang, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Ju, J.; Zhang, H.; Ma, J. Ilamycin C induces apoptosis and inhibits migration and invasion in triple-negative breast cancer by suppressing IL-6/STAT3 pathway. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.H.; Rao, L.; Luo, L.F.; Chen, K.; Ran, R.Z.; Liu, X.L. Long non-coding RNA NKILA inhibited angiogenesis of breast cancer through NF-κB/IL-6 signaling pathway. Microvasc. Res. 2020, 129, 103968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Q.; Su, Q.; Wei, W.; Du, J.; Wang, H. Activation of GPER suppresses migration and angiogenesis of triple negative breast cancer via inhibition of NF-κB/IL-6 Signals. Cancer Lett. 2017, 386, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, R.; Ye, Y.; Liu, P.; Yu, W.; Wei, F.; Ren, X.; Yu, J. Interleukin-6 trans-signaling pathway promotes immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells via suppression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 in breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).