Abstract

To address image degradation in optical telescopes with fast focal ratios—a problem caused by the misalignment of optical elements during assembly and observation—this study proposes a high-precision calibration method for image quality detection and correction. The method substitutes parallel laser beams for starlight to generate the incident wavefront required for calibration. Low-order aberrations resulting from system misalignment are calculated from the centroid coordinate offsets of laser spots on defocused planes, thereby enabling feedback-controlled alignment adjustments. Simulations and experiments were conducted on a single parabolic mirror system with a diameter (D) of 500 mm and a focal ratio of . The results indicate that for mirror tilt misalignments ranging from to , the estimated error for the Zernike coefficients – is below ( nm). This accuracy meets the alignment requirements for telescopes with fast focal ratios and eliminates the need for large flat mirrors and clear night skies, which are traditionally required for outdoor calibration. Consequently, the method provides a low-cost, high-precision solution for the real-time calibration of telescopes at remote sites, such as those in Antarctica.

1. Introduction

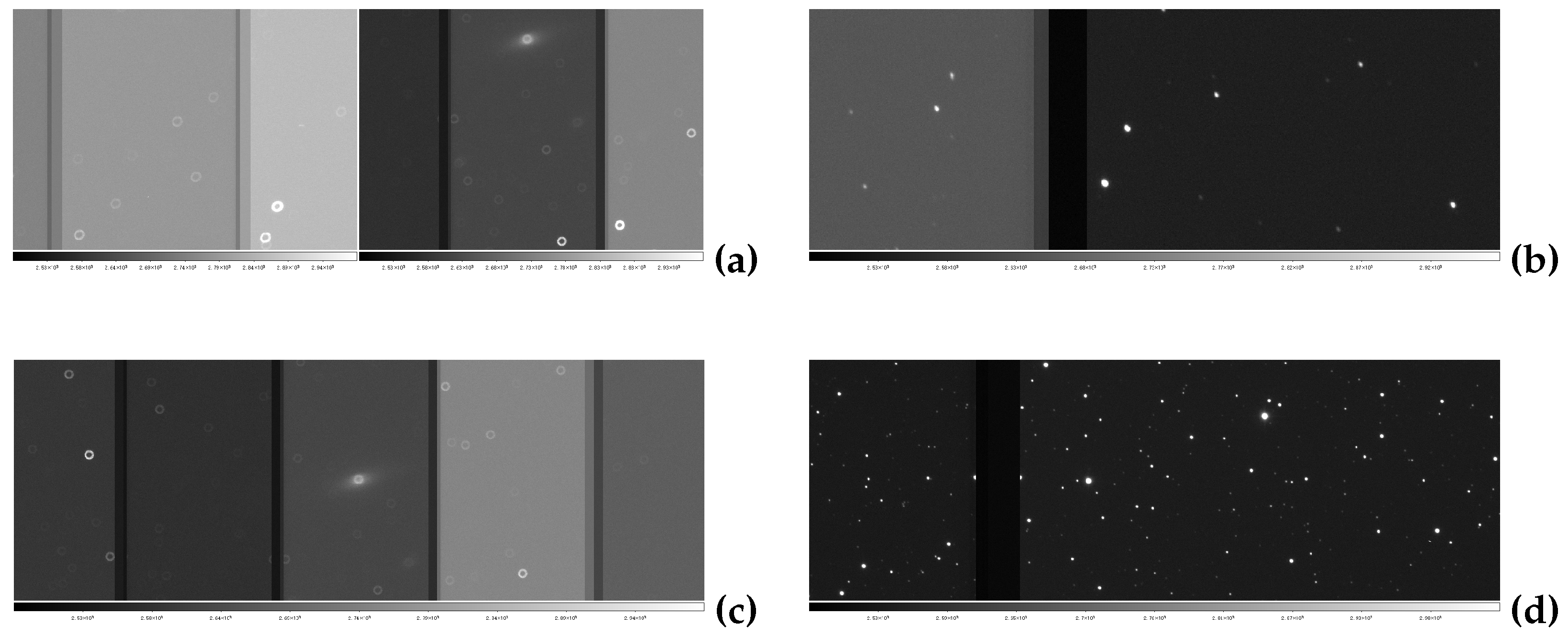

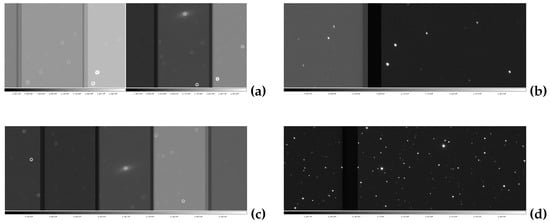

Advancements in telescope aperture, light-gathering power, and optical resolution have driven a trend toward faster focal ratios in primary mirror design [1]. This shift effectively shortens the tube length and enlarges the field of view for large and extremely large telescopes. However, optical systems with fast focal ratios are highly sensitive to alignment errors. During observations, variations in the zenith angle cause continuous changes in the angle between the optical axis and the direction of gravity [2]. This can readily induce support structure deformations, displacing optical components from the optical axis and resulting in image degradation. Consequently, high-precision active alignment methods are essential for online detection and real-time correction. To secure favorable observing conditions, large-aperture telescopes with fast focal ratios are typically sited at high-altitude locations characterized by limited transportation access and complex installation environments. Under such field conditions, performing precise optical alignment—particularly for astronomical telescopes—presents substantial challenges. Conventional instruments like interferometers or wavefront sensors often prove impractical in these settings; wavefront sensors, for instance, require bright guide stars for operation and are constrained by both sampling frequency and detection sensitivity. The following images illustrate the star-based alignment process implemented for the Ritchey–Chrétien Telescope: Figure 1a,b present defocused and in-focus stellar images exhibiting significant comatic aberration. Figure 1c,d show the corresponding defocused and in-focus images after correction of the secondary mirror misalignment, which now satisfy the specified imaging quality requirements.

Figure 1.

A comparison of stellar images before and after alignment correction: (a,b) (before) show evident coma aberration in both defocused and in-focus states, while (c,d) (after adjustment of secondary mirror misalignment) meet the required precision.

Furthermore, Antarctica serves as a prominent example [3,4,5], where telescopes operate unattended for extended periods with an annual maintenance window of only approximately 20 days due to the limited summer field season in the continent’s interior. The continuous daylight during polar summer further precludes star-based image quality assessment. Similarly, the “Sitian” Project [6], proposed by Chinese astronomers, plans to deploy hundreds of meter-class optical telescopes at international observatory sites, where on-site optical alignment presents a substantial challenge. In the alignment of fast focal ratio optical systems, installation errors of optical elements represent a primary source of system misalignment [7,8,9]. To ensure optical performance meets design specifications, it is essential to detect and correct positional, orientational, and tilt errors of optical components. Consequently, there is a critical need for a high-precision telescope alignment method capable of real-time image quality monitoring and wavefront correction, thereby maintaining high imaging accuracy during telescope tracking and ensuring the acquisition of high-quality astronomical data.

In recent years, telescope alignment methods have been predominantly categorized into two groups: those that calculate misalignment using intensity or positional features, and those that leverage characteristics of the intra-field distribution. As early as 2015, Li Zhengyang [10] introduced an active alignment method for wide-field telescopes based on Zernike polynomial decomposition. This approach determines misalignment in multi-degree-of-freedom optical systems by correlating misalignment errors with field-dependent characteristics, eliminating the requirement for direct wavefront detection or reconstruction. In 2016, Wu Zhixu et al. [11] proposed a wavefront recovery technique utilizing a single defocused image, which was successfully validated on the KDUST telescope. In contrast to traditional curvature wavefront sensors, this method simplifies wavefront retrieval from a single defocused frame.

In 2022, Wu Zhixu et al. [12] proposed an alignment method based on machine learning that utilizes stellar images from a science camera. The study theoretically established that the intra-field point spread function (PSF) distribution is closely related to the alignment state and employed a two-step neural network to learn this relationship. The resulting alignment achieved decentering errors below 5 m and tilt errors under 5 arcseconds. Similarly, in 2023, Zhang Miao et al. [13] leveraged PSF variations to identify misalignments of optical elements and developed a deep learning model to estimate telescope misalignment and enhance image quality.

In 2023, Chen Chao [3] proposed a novel method, termed the RSVA method, for assessing optical system image quality. Building upon this theoretical foundation, Chen Chao et al. [14] introduced in 2024 an SVA method for correcting misalignment in telescope optical systems. Utilizing only 10 rays, this method achieved a root mean square (RMS) secondary mirror misalignment below 1 m with a resolution of 3.6 arcseconds.

Owing to the high directionality of laser light, characterized by a typical divergence angle of less than a few milliradians, this paper proposes a structured-light-based mechanism for detecting alignment errors. The proposed system offers advantages such as structural simplicity and high alignment accuracy. It employs a laser source to substitute for the collimated light traditionally required in optical system alignment. The incident wavefront aberration coefficients can be determined by analyzing the coordinate shifts of the laser beam centers. Section 2 establishes the theoretical relationship between these coordinate shifts and wavefront reconstruction, while Section 3 presents the experimental validation and a corresponding analysis of the telescope alignment method.

2. Methodology

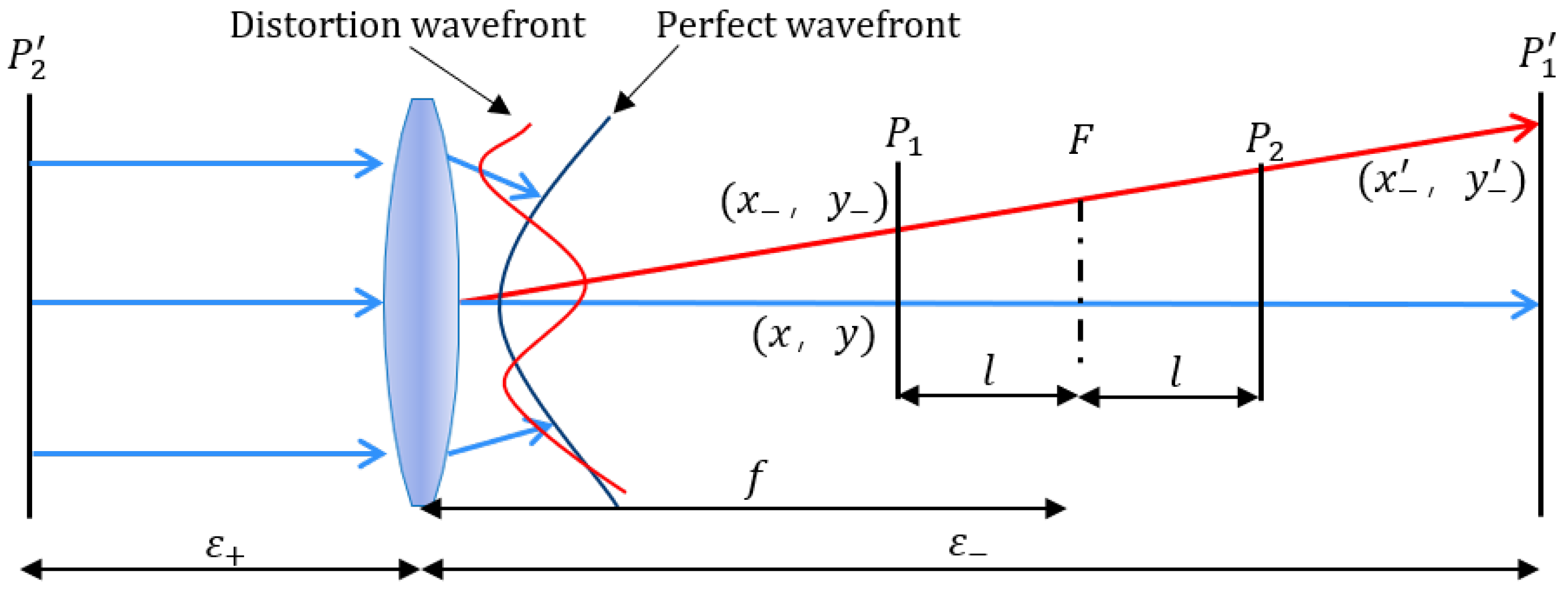

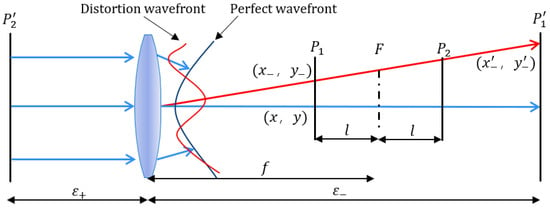

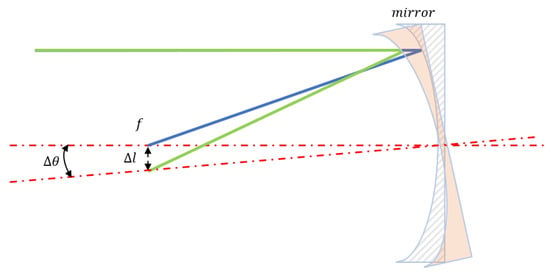

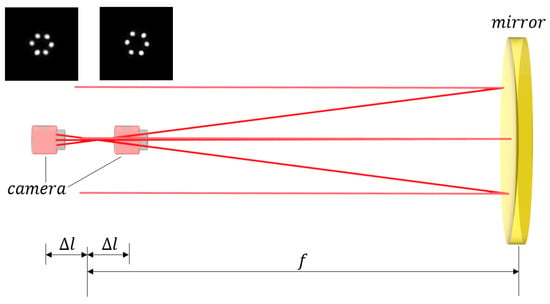

As shown in Figure 2, a laser beam is converged by an optical system with focal length f to the focal point F, passing through the defocused planes and . The defocus distance for both planes is set as l. The conjugate plane of is located upstream in the optical path, while the conjugate plane of is situated downstream. Let denote the distance from to the principal point of the optical system, and the distance from to the principal point.

Figure 2.

Coordinate distortion in the in-focus and conjugate planes induced by a wavefront error between two neighboring laser beams.

According to the Gaussian formula [15]:

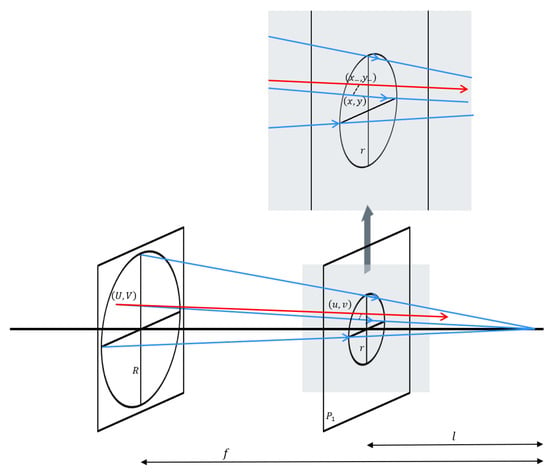

As shown in Figure 3, the radius of the optical system under test is R. The Cartesian coordinates on the wavefront aberration surface are denoted by , with normalized coordinates defined as and . Similarly, the Cartesian coordinates on the defocused plane are denoted by , with normalized coordinates and , where .

Figure 3.

Normalization of the coordinates of the defocused plane , red/blue arrows indicate distortion/perfect wavefront.

The aberration at a point on the wavefront aberration surface causes a laser beam deviation of . The coordinate distortions on defocused planes and are denoted by and , respectively, while those on the conjugate planes and are represented by and .

The normalized coordinate distortion in the conjugate plane corresponding to the defocused plane can be expressed as:

Similarly, the normalized coordinate distortion in the conjugate plane corresponding to defocused plane can be expressed as:

Therefore, the relationship between the wavefront aberration and the coordinate distortion in the defocused conjugate plane can be expressed as:

Since the coordinates on the defocused plane , and those on the conjugate plane , are related by a factor of , the relationship between the wavefront aberration and the coordinate distortion on the defocused plane can be derived as:

To achieve image quality calibration in the optical system, Zernike polynomials are employed to reconstruct the wavefront aberration of the mirror [16,17]. The wavefront under test is assumed to be expressible as a linear combination of basis functions. Defined as a set of orthogonal polynomials over the unit circle, Zernike polynomials decompose complex wavefront aberrations into a linear combination of basis functions, each corresponding to a specific aberration mode (e.g., defocus, astigmatism, or coma). Their lower-order terms correspond to the classical Seidel aberrations, making them a widely adopted mathematical model for aberration representation [18]. Using the polynomial forms obtained from optical simulation software or interferometric measurement data, the first nine Zernike coefficients and their corresponding interpretations are listed as Table 1:

Table 1.

The first nine Zernike coefficients and their meanings.

Wavefront reconstruction is performed using the first-order partial derivatives of the wavefront. To mitigate interpolation errors, the wavefront aberration is expanded using a subset of low-order Zernike polynomials. Let denote the Zernike polynomial, the Zernike coefficient, and i the term index of the Zernike polynomial:

The first-order partial derivatives of the wavefront aberration satisfy the following relationship:

The relationship between the coordinate offsets of the laser beam on the pre-focal and post-focal planes and the wavefront distortion can therefore be expressed in the following matrix form:

The constant is defined as , , , , leading to the following linear equation:

According to the least squares method, the Zernike coefficients of the wavefront aberration satisfy the following analytical relationship:

Thus, a theoretical relationship has been established between the wavefront of the optical system under test and the laser beam coordinate offsets.

3. Experimentation

3.1. Experimental Procedure

In practical applications, the design of laser arrays must simultaneously consider the spatial and angular frequency characteristics, as well as the relationship between the aperture and optical aberrations.

In ray tracing, representative points, such as 0.707, are typically selected to evaluate the aberration distribution and the overall performance of the system. This is also a standard approach in optical design, balancing primary spherical aberration and higher-order spherical aberration to minimize residual wavefront error in the edge region. Furthermore, according to geometrical optics, in a system exhibiting only primary and secondary spherical aberration, the condition of zero marginal spherical aberration leads to the maximum residual aberration at the zone, where its magnitude equals of the higher-order spherical aberration at the marginal zone, with opposite sign. As Zernike polynomials constitute a set of orthogonal functions defined in polar coordinates with rotational symmetry, the spatial distribution of sampling points exerts a more direct influence on fitting accuracy than either the number of sampling points or concentric rings. On one hand, an even number of sampling points helps preserve symmetry, whereas an odd number can result in the absence of symmetric point pairs along certain directions, leading to accumulated errors. On the other hand, in the Zernike representation, the astigmatism terms— and —require high angular symmetry. If the number of sampling points is odd, it becomes challenging to accurately evaluate the integrals over symmetric angular intervals, thereby reducing the precision of the wavefront fit.

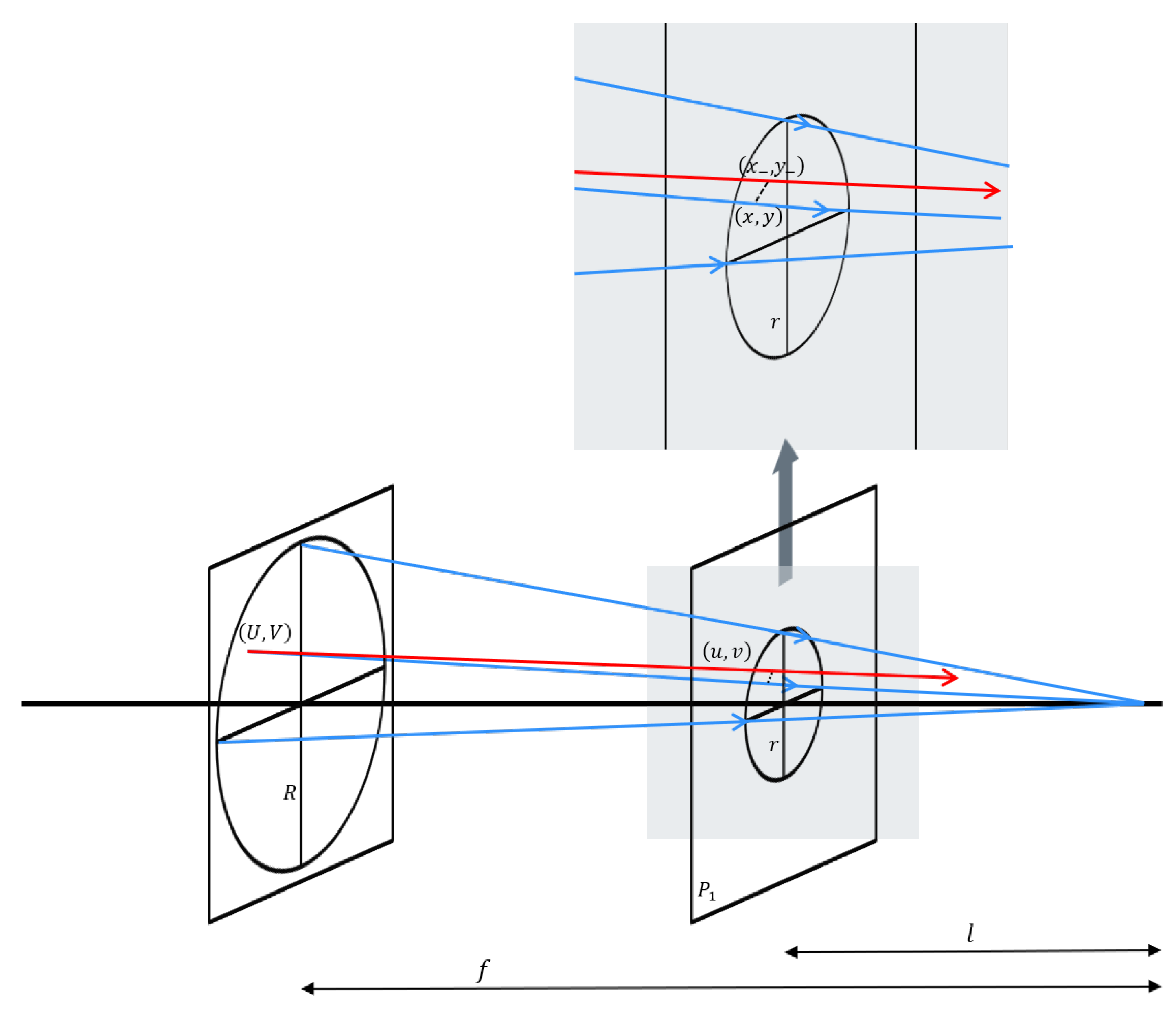

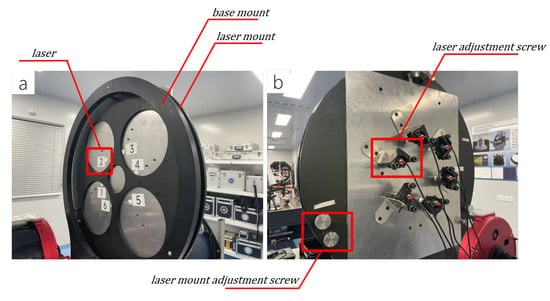

So in the experimental validation, six laser beams with a wavelength of nm and radius of 0.707 (assume that the radius of the optical system is 1) were employed to verify the proposed method. This configuration ensures adequate symmetry while simultaneously reducing experimental complexity and minimizing potential error sources. As shown in Figure 4, to adjust the direction and spatial coordinates of the parallel laser source, a dual-layer support structure is employed for the laser array, comprising a movable laser mount and a stationary base mount. Each laser is mounted on the laser mount via a screw mechanism incorporating an adjustment spring. The laser mount is aligned parallel to the base mount and secured by three circumferentially distributed push–pull screws. By adjusting these screws, the tilt of individual laser beams or the orientation of the entire laser array can be precisely controlled.

Figure 4.

Laser collimator parallel light source: (a) front; (b) back.

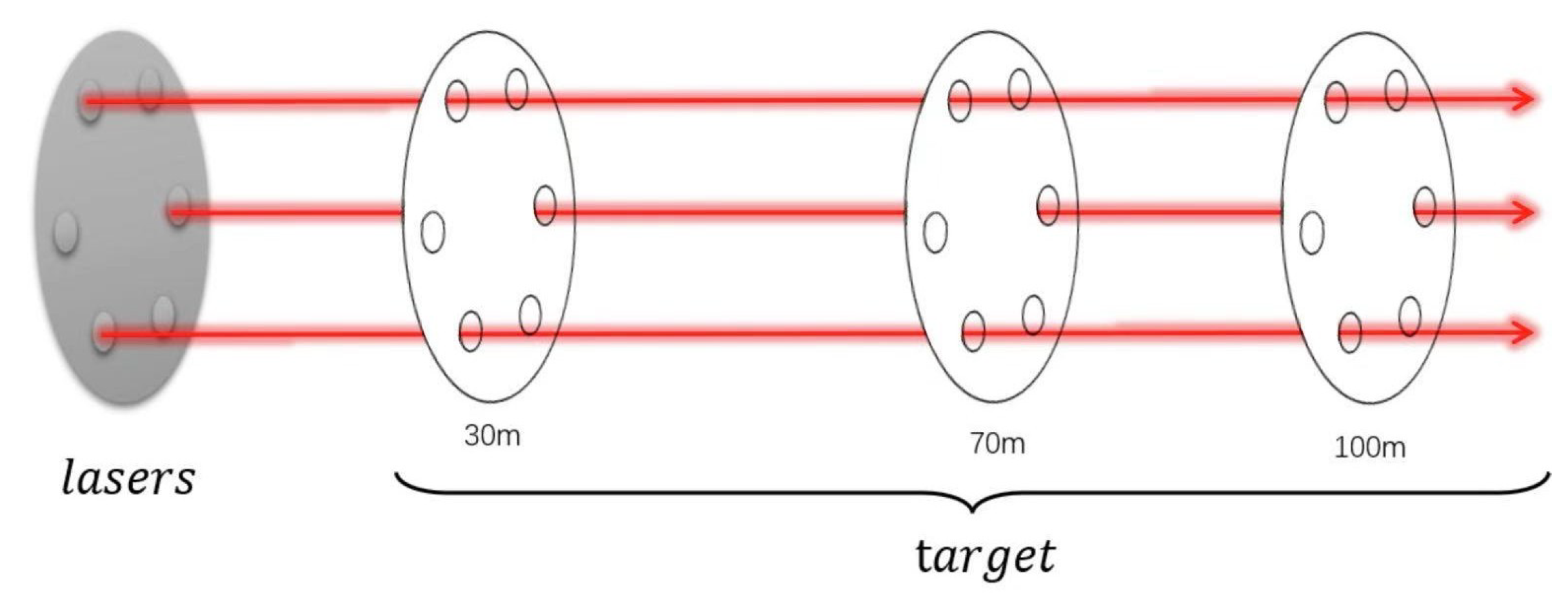

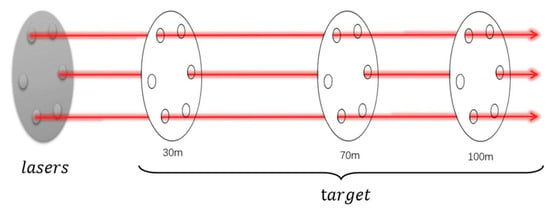

To ensure high parallelism of the laser array, pre-alignment is conducted by adjusting the tilt and pitch of each laser unit using control knobs. A custom-fabricated laser source with adjustable focus is employed, enabling control over the focal position and, consequently, the resulting spot size according to the working distance. In the experimental setup, each laser beam exhibits a diameter of approximately 1 mm. Collimation targets marked with corresponding serial numbers are positioned at distances ranging from 30 to 100 m as shown in Figure 5. By sequentially adjusting the tilt of each laser unit, all beams are precisely aligned with their designated target points. This procedure maintains the parallelism of the laser array within 3–5 arcseconds, satisfying the telescope’s alignment specifications. For verification, the collimation targets are subsequently replaced with plane mirrors: when the laser beams are mutually parallel, the spots of the incident and reflected beams coincide precisely.

Figure 5.

Using a target in collimation.

First, the aligned parallel laser beam array is directed onto the concave mirror, and a camera captures one pre-focal and one post-focal image at equal defocus distances. The images are then preprocessed to accurately extract the centroid coordinates of the laser spots. Wavefront reconstruction is subsequently performed using the extracted coordinates. To facilitate observation of aberration effects on imaging, controlled perturbations are intentionally introduced into the optical system. Since the mirror tilt angle cannot be directly measured, the displacement of the spot centroids serves as an indirect indicator of the mirror’s tilt magnitude.

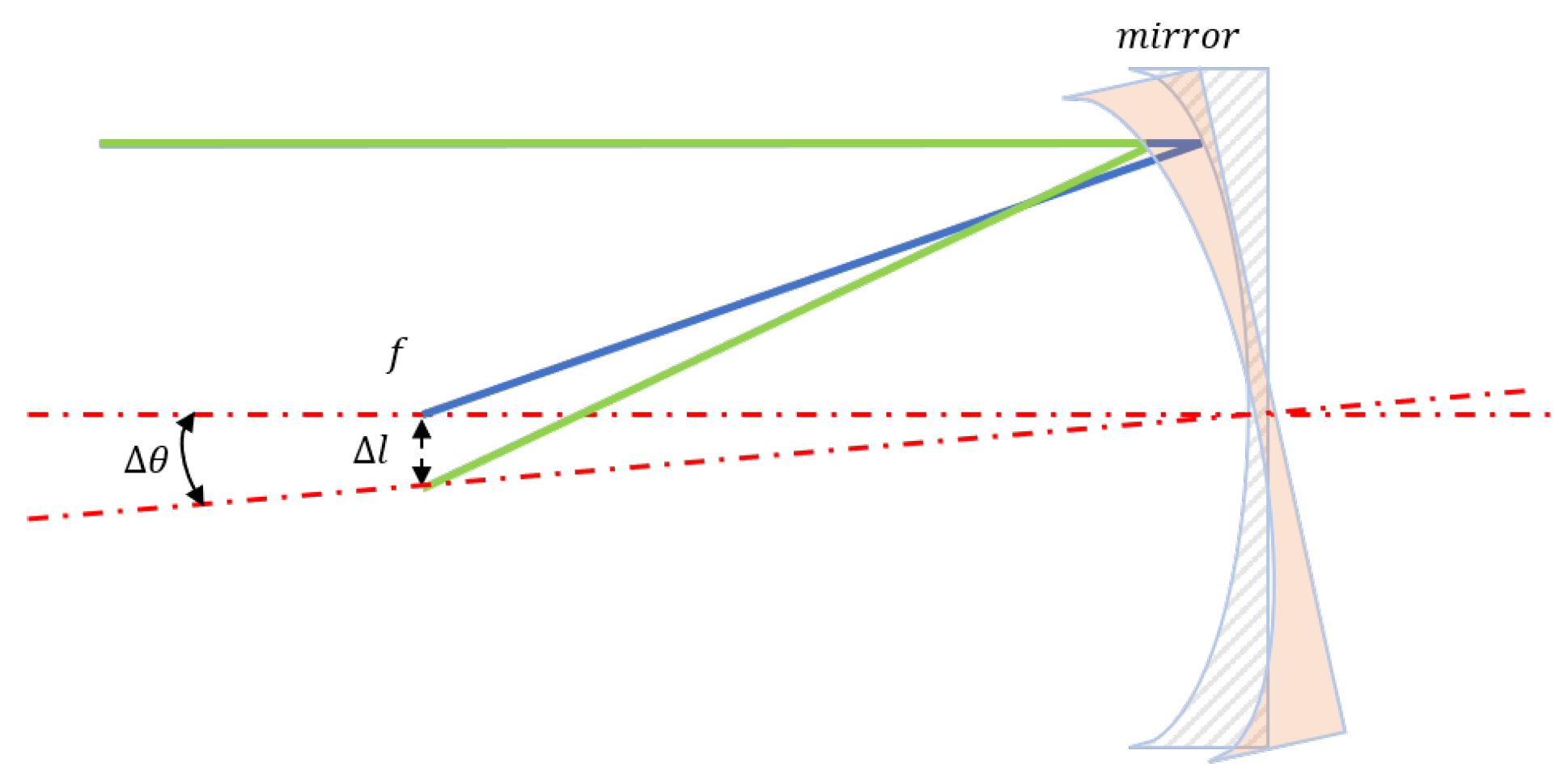

As shown in Figure 6, the blue line corresponds to the incident ray, the green line represents the reflected ray after mirror translation, and the red dashed line indicates the surface normal passing through the mirror’s center. The relationship between the displacement of the spot centroid on the camera and the tilt angle of the concave mirror is described by Equation (11).

where f is the focal length of the concave mirror, is the displacement of a spot centroid on the camera, and is the tilt angle of the concave mirror.

Figure 6.

The tilt of the mirror and the movement of the center of mass of the light spot.

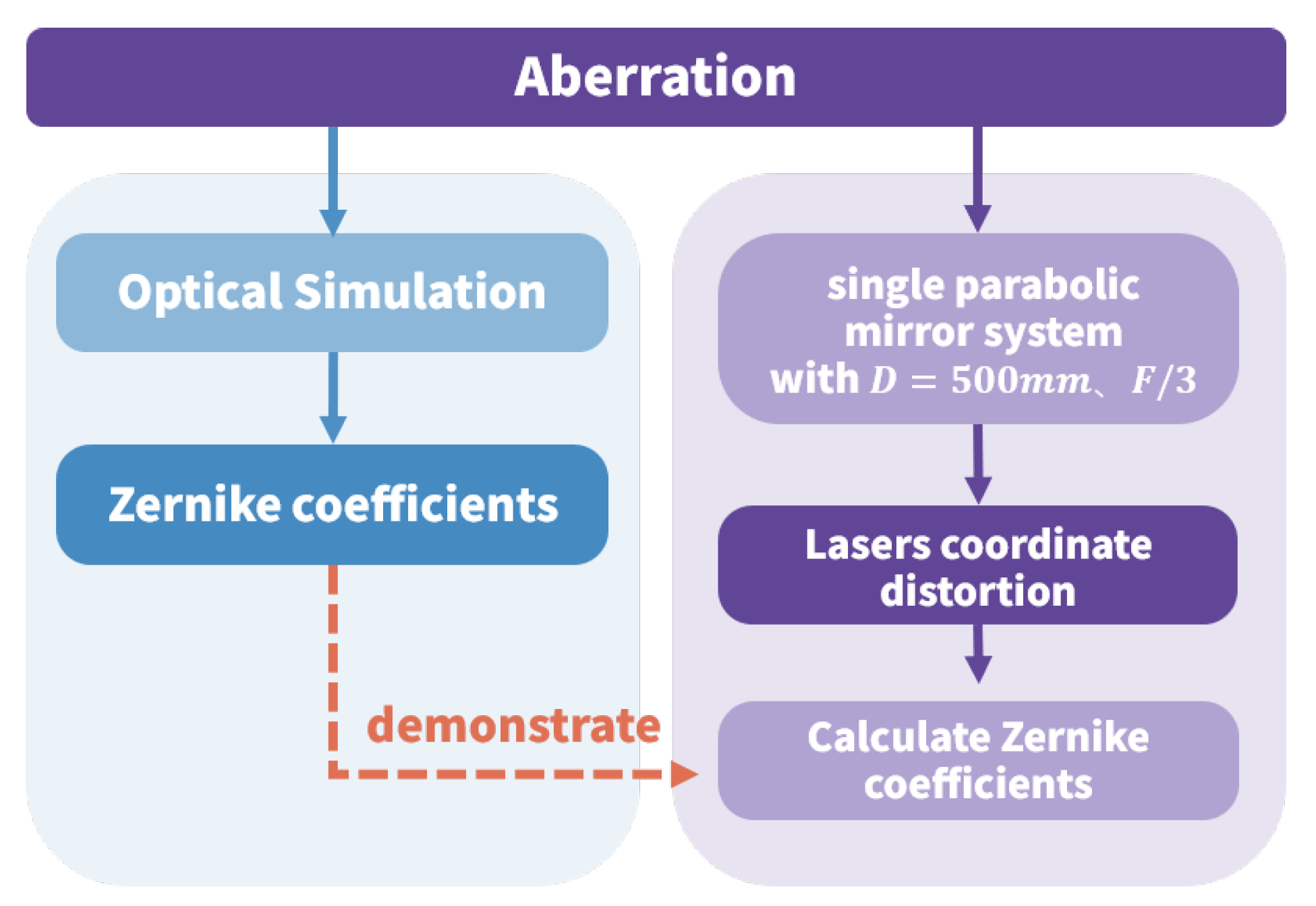

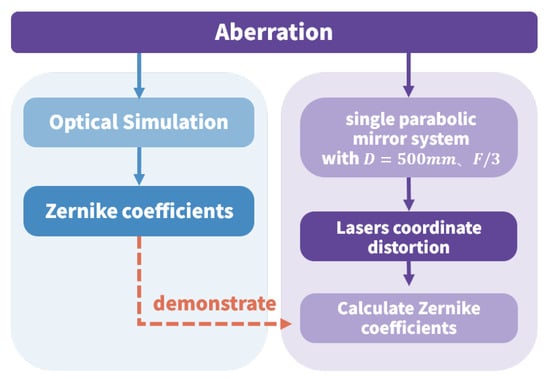

The experimental process was simulated using mathematical modeling and optical design software to validate the result accuracy. To emulate a realistically misaligned telescope, misalignment parameters were introduced into the optical design model, and the resulting laser spot displacements at the defocused plane of the target imaging system were statistically analyzed. Zernike coefficients were subsequently calculated using Equation (10) to further verify the experimental accuracy. The corresponding workflow is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Tested process.

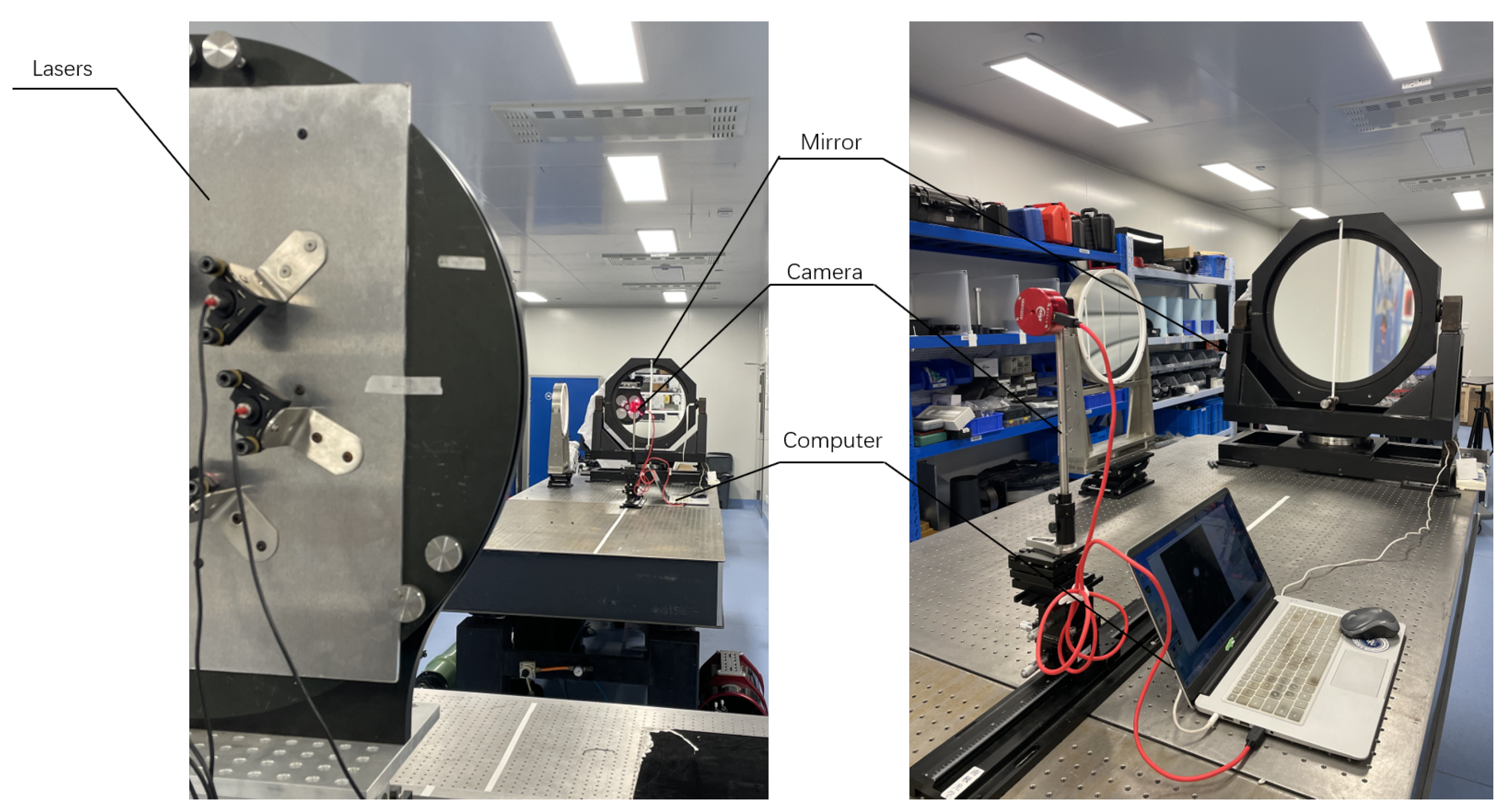

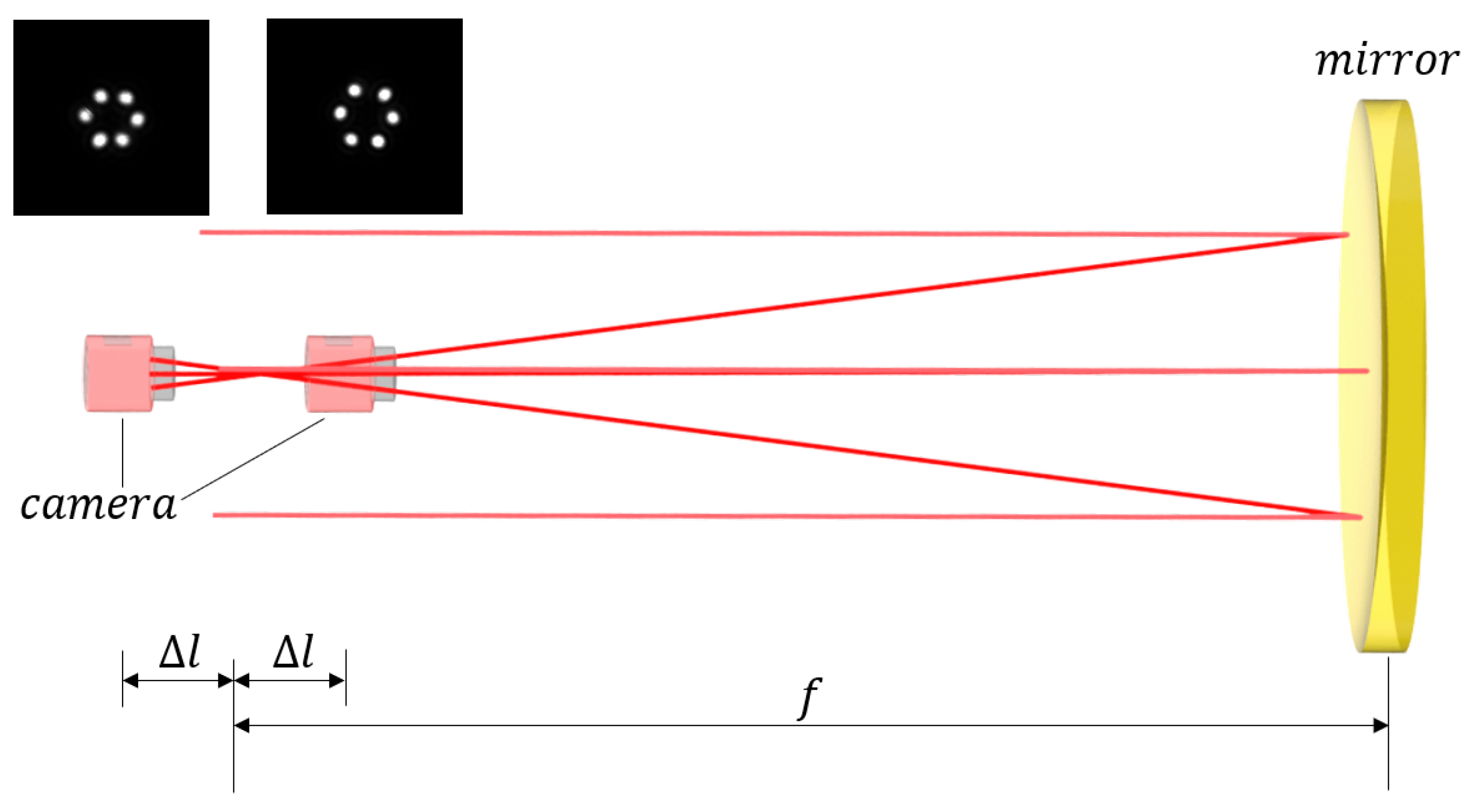

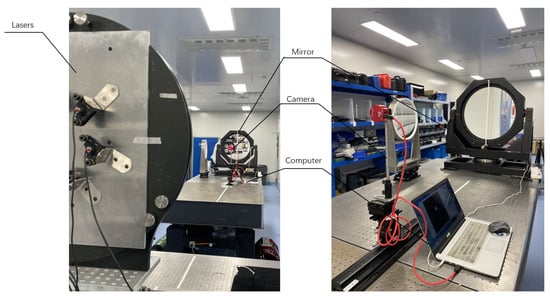

3.2. Experimental System

To meet the verification requirements for alignment methods of optical systems with fast focal ratios, a coaxial optical system comprising a laser array, a concave mirror, and a camera was constructed based on a single parabolic mirror system with a diameter of mm and a focal ratio of . The experimental setup is shown in Figure 8, and the corresponding optical layout is presented in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Physical system.

Figure 9.

Tested system design.

3.3. Experimental Result

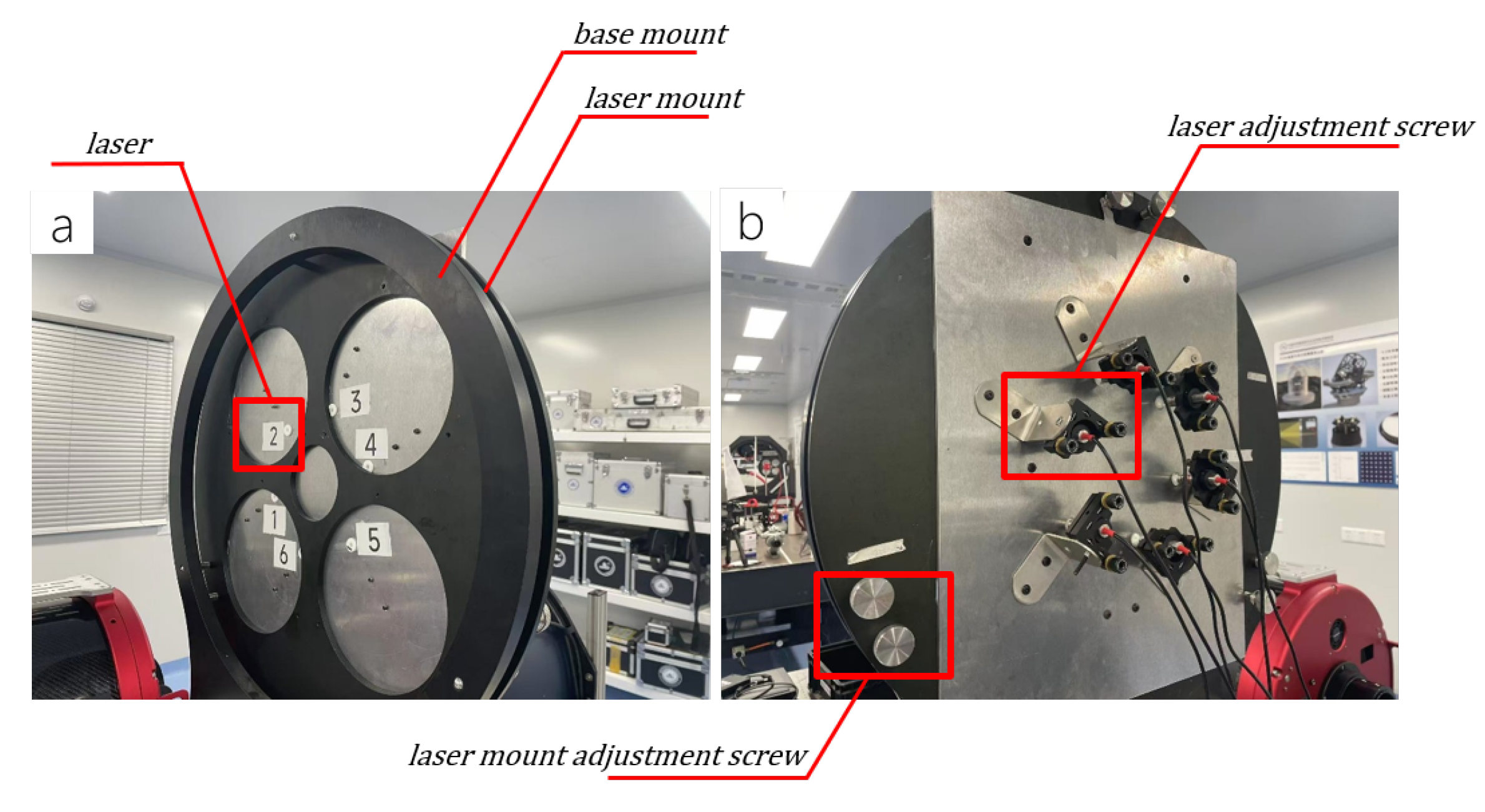

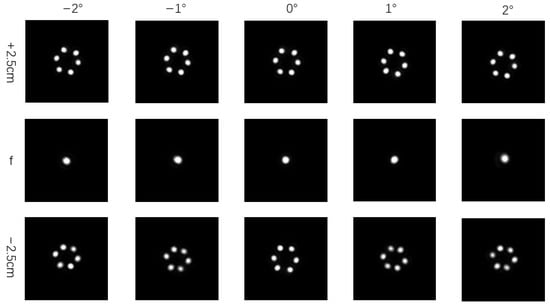

The centroid positions of the laser spots at different tilt angles along the X-axis, obtained using this method, are shown in Figure 10. The camera features a resolution of pixels and a pixel pitch of 3.76 m.

Figure 10.

Experimental results.

Due to laser diffraction effects, spot edge extraction significantly influences centroid localization accuracy. Established techniques—including median filtering [19,20], morphological opening, and closing operations [21,22,23]—were employed for image preprocessing, yielding satisfactory results. The laser spot centroid, corresponding to its grayscale center of mass, was calculated using the grayscale centroid method [24,25,26], which offers advantages in computational speed and precision.

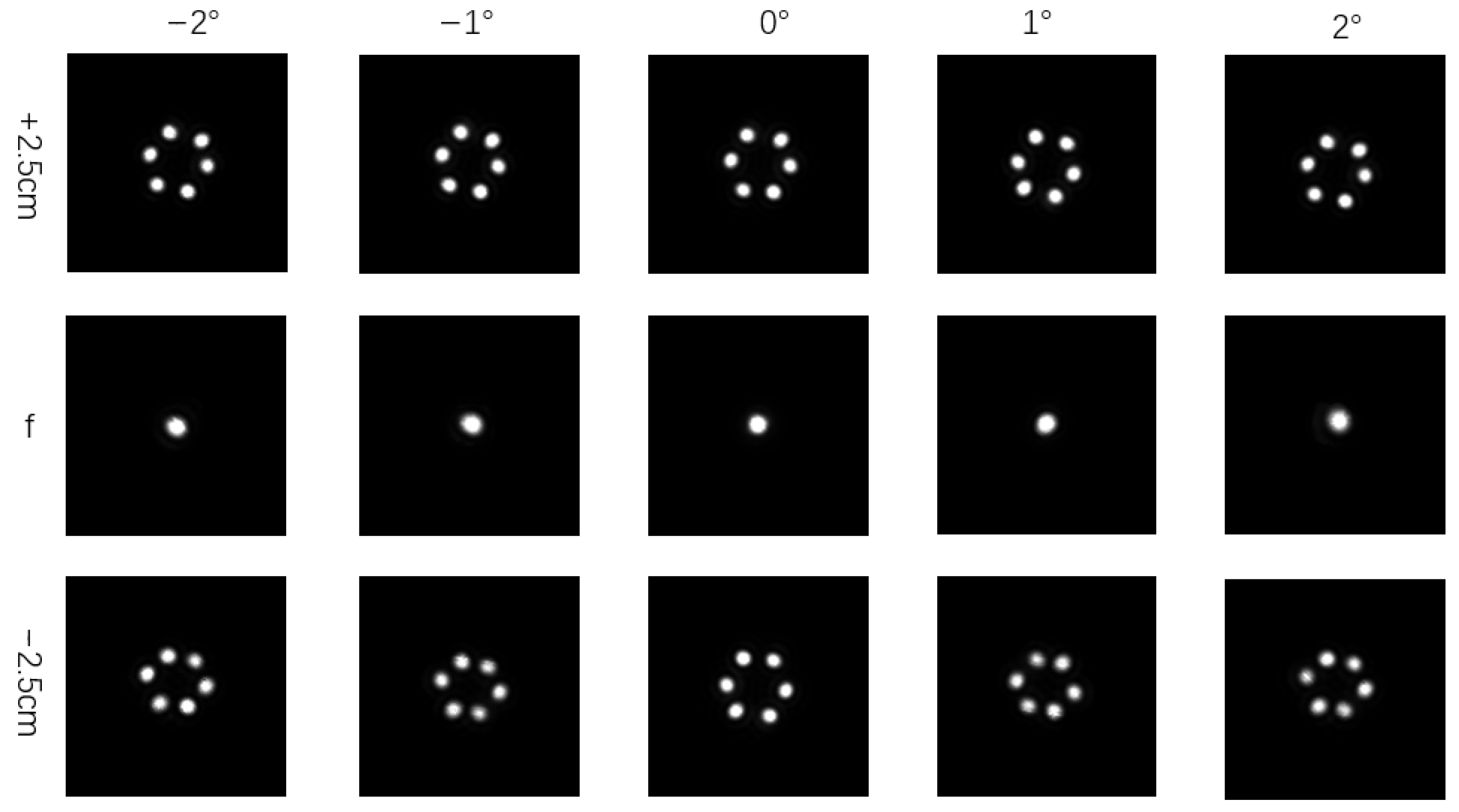

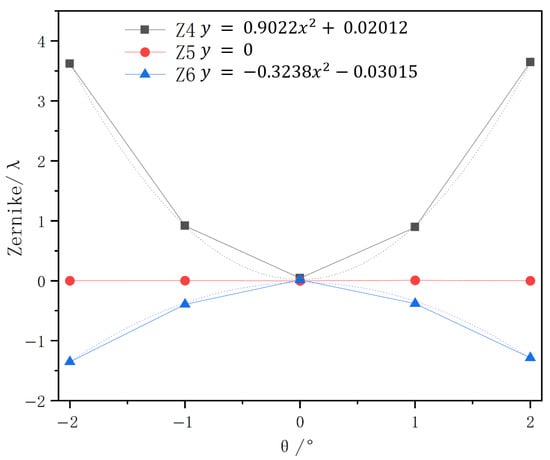

Based on the acquired defocused images, laser spot displacements were calculated and used to determine the Zernike coefficients for terms to . The corresponding results are presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Experimental results and fitting curves.

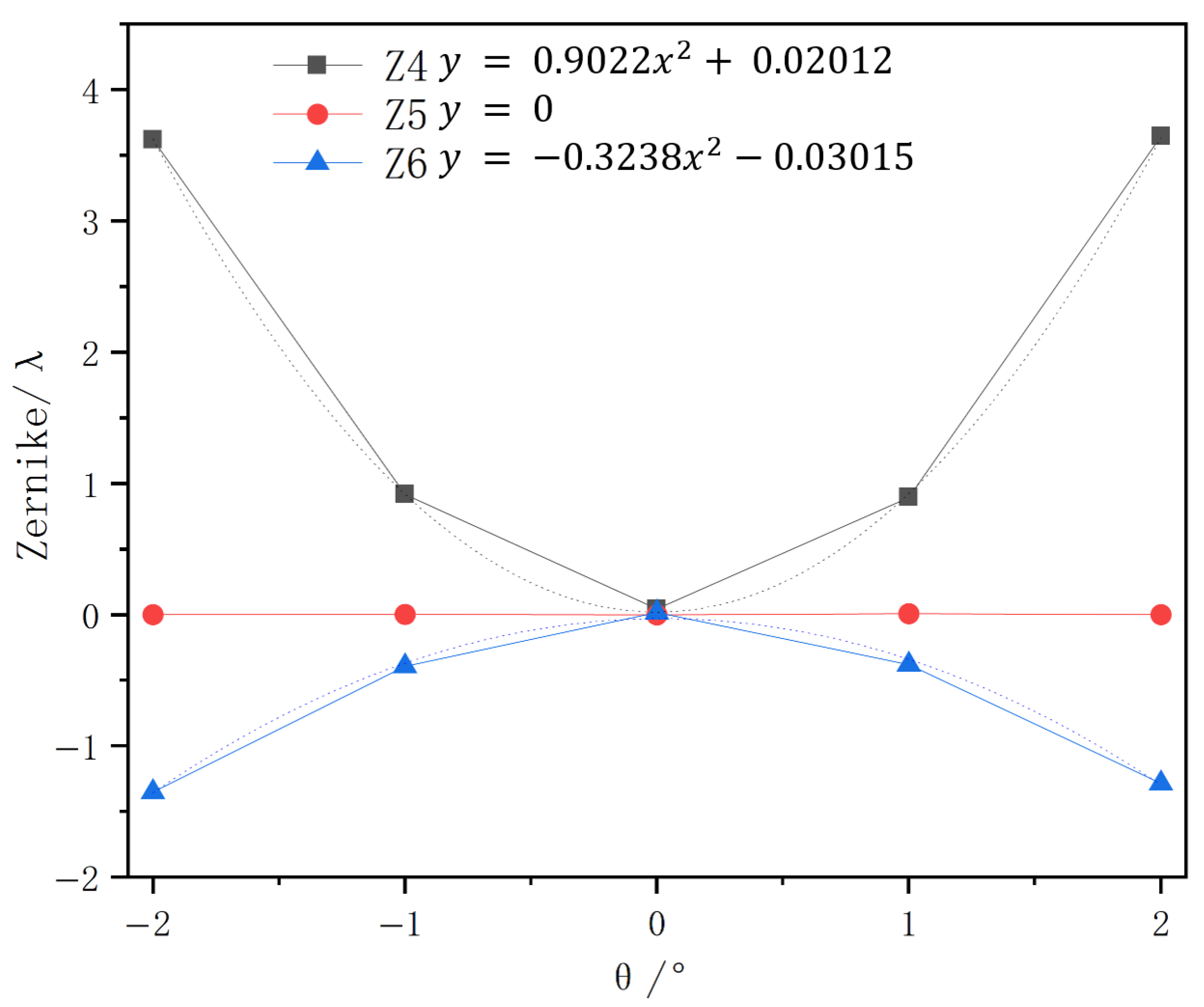

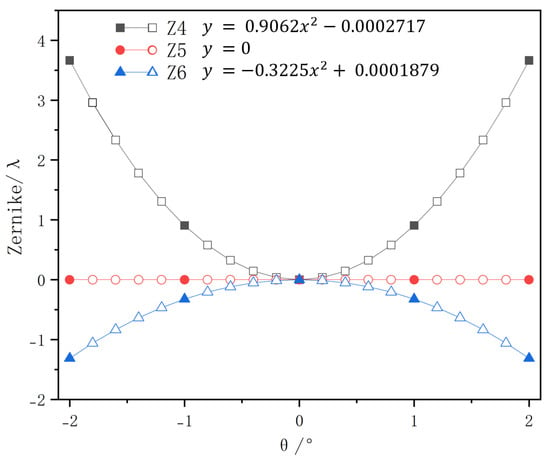

Meanwhile, an equivalent simulation model was constructed using optical simulation software. By systematically rotating the primary mirror to different tilt angles and employing the built-in wavefront fitting function of the Ansys Zemax Optic Studio, the corresponding Zernike coefficients under identical offset conditions to the experiment were obtained. The simulation results are presented in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Simulation results and fitting curves.

A comparison between experimental and simulation results reveals that the quadratic coefficient difference between the experimentally fitted tilt angle–Zernike coefficient curve and the simulation curve is less than 0.01. The estimation error for Zernike coefficients – remains below ( nm). These results demonstrate that the laser beam alignment method can effectively detect mirror misalignment in optical systems and provides the feasibility for self-calibration of such systems. As shown in the comparison Table 2, the proposed method facilitates the measurement of low-order aberrations induced by alignment errors [26,27,28]. Unlike stellar sources, our laser bundle is weather-independent and provides immediate data; compared to interferometric testing, our method does not rely on large-aperture flat mirrors or an interferometer, thereby significantly simplifying the alignment process and reducing its complexity. It substantially simplifies the telescope collimation process and enables high-precision optical system adjustment at field sites.

Table 2.

Performance and Characteristics of Alignment Methods.

4. Conclusions

To address image degradation in optical telescopes caused by misaligned optical elements, this study proposes a structured-light-based alignment method for fast focal ratio systems. The theoretical relationship between low-order aberrations and laser spot displacements was established, followed by comprehensive simulation and experimental validation. Within a mirror tilt range of , the estimation error for Zernike coefficients – remained below ( nm). These results demonstrate that the proposed method can accurately detect system misalignment and quantify low-order aberrations introduced during telescope alignment, thereby establishing a foundation for subsequent closed-loop correction using feedback control systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. and Z.L.; software, H.Y.; methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, H.G.; writing—review and editing, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Research Project of the Education Department of Jilin Province, grant number JJKH20250500BS.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Cui, X.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Chu, Y.-Q.; Yang, S.-H.; Li, G.-P.; Qi, L.; Zhang, L.-P.; Su, H.-J.; Yao, Z.-Q.; Xing, X.-Z.; et al. The Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fiber Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST). Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 36, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.-Q.; Wang, Z.-C.; Chen, B.-G.; Li, H.-W.; Chen, T.; An, Q.-C.; Fan, L. Review of the active control technology of large aperture ground telescopes with segmented mirrors. Chin. Opt. 2020, 13, 1194–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. The Antarctic Wide-Field Optical System Research. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Andreas, K.; Martin, M.-R.; Yang, C.-W.; Hans, G.-L.; Michael, K.; Astrophysikalisches, I.-P.; Universität, P. Astrochemistry and Astrophotonics for an Antarctic Observatory. EAS Publ. Ser. 2009, 40, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksaker, N.; Bayazit, M.; Kurt, Z.; Yerli, S.-K.; Aktay, A.; Erdoğan, M.-A. Astronomical site selection for Antarctica with astro-meteorological parameters. Exp. Astron. 2024, 58, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-F.; Soria, R.; Wu, X.-F.; Wu, H.; Shang, Z.-H. The SiTian Project. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2021, 93, e20200628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.-C.; Zhang, H.-F.; Wu, X.-X.; Wang, J.-L.; Chen, T.; Hong, W.-L. Photonics Large-Survey Telescope Internal Motion Metrology System. Photonics 2023, 10, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.-B.; Zhang, A.; Xian, H. Research on telescope alignment using a generic wavefront sensorless method based on images with different sampling parameters. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 187, 112756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, M.; Guthery, C.; Chambouleyron, V.; Clem, R.-J.; Wallace, J.-K.; Delorme, J.-R.; Troy, M.; Wenger, T.; Echeverri, D.; Finnerty, L.; et al. Keck Primary Mirror Closed-loop Segment Control Using a Vector-Zernike Wavefront Sensor. Astrophys. J. 2024, 967, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Y.; Yang, X.-Y.; Cui, X.-Q. Alignment metrology for the Antarctica Kunlun Dark Universe Survey Telescope. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 449, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-X.; Bai, H.; Cui, X.-Q. Wave-front Sensing by Single Defocuesd Image. Prog. Astron. 2016, 34, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.-X.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Tang, R.-X.; Li, Z.-Y.; Yuan, X.-Y.; Xia, Y.; Bai, H.; Li, B.; Chen, Z.; Cui, X.-Q.; et al. Machine Learning for Improving Stellar Image-based Alignment in Wide-field Telescopes. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2022, 22, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Jiang, P.; Li, Z.-Y.; Xiang, W.-N.; Lv, J.-M.; Sun, R. Perception of misalignment states for sky survey telescopes with the digital twin and the deep neural networks. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 44054–44075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Li, Z.-Y.; Liu, T.-T.; Cong, J.-N.; Han, Z.-J.; Li, X.-Y.; Yuan, X.-Y.; He, L. A machine learning-based method for resolving secondary mirror misalignment in telescope optical systems. RAS Tech. Instruments 2024, 3, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Xia, Y.; Han, Z.-J.; Tang, R.-X.; Wu, Z.-X.; Yuan, X.-Y. Telescope alignment based on the structured lighting of collimated laser beam bundles. In Proceedings of the Advances in Optical and Mechanical Technologies for Telescopes and Instrumentation V, Montréal, QC, Canada, 17–22 July 2022; p. 1218860. [Google Scholar]

- Roddier, C.; Roddier, F. Wave-front reconstruction from defocused images and the testing of ground-based optical telescopes. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1993, 10, 2277–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yang, Z.-M.; Zhang, Y.-F. Modal wavefront reconstruction by Schwarz-Christoffel mapping and Zernike circle polynomials for noncircular pupils. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 184, 108643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.-K.; Ji, F.; Ke, X.-Z. Research on the application of Zernike polynomials in optical systems. Opt. Commun. Technol. 2025, 49, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, G.-S.; He, Q.; Wei, Y.-C.; Mo, D.-H.; Li, J. Edge Detection System Based on Ethernet and FPGA Image Processing. Instrum. Tech. Sens. 2023, 10, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y.-K.; Chen, X.-R.; Li, Y.-G. Median filtering detection based on multiple residuals in spatial and frequency domains. Signal Image Video Process. 2025, 19, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.-Y.; Liu, S.-D. Dynamic Window-based Adaptive Median Filter Alogorithm. Open Cybern. Syst. J. 2015, 9, 1502–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Sun, L.-M.; Chen, J. A Hybrid Decision-Making Adaptive Median Filtering Algorithm with Dual-Window Detection and PSO Co-Optimization. Modelling 2025, 6, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echavarría, A.-G.; Ugarte, J.-P.; Tobón, C. The fractional Fourier transform as a biomedical signal and image processing tool: A review. Modelling 2020, 40, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.-L.; Hu, Z.-W.; Ji, H.-X. Laser spot center positioning algorithm based on Gaussian fitting. Appl. Opt. 2012, 33, 985–990. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R.-H.; Liu, H.-S.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, Z.-R.; Jin, G. High-precision laser spot center positioning method for weak light conditions. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, Z.-H.; Guo, P.; Zhang, Y.-C.; Chen, S.-Y. Research of the High Precision Laser Spot Center Location Algorithm. Trans. Beijing Inst. Technol. 2016, 36, 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.-G.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y.-Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.-M.; Du, M.; Guan, W.; Su, Y.; Zuo, X.-Z.; Shi, Y.-H. Alignment technology of off-axis Cassegrain optical system. Opt. Technol. 2024, 50, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Z.-Y.; Yan, C.-X.; Li, X.-B.; Hu, C.-H.; Wang, Y. Application of modified sensitivity matrix method in alignment of off-axis telescope. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2015, 23, 2595–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.