Abstract

ChatGPT has emerged as a promising tool for enhancing clinical practice. However, its implementation raises critical questions about its impact on this field. In this scoping review, we explored the utility of ChatGPT in pharmacy practice. A search was conducted in five databases up to 23 May 2024. Studies analyzing the use of ChatGPT with direct or potential applications in pharmacy practice were included. A total of 839 records were identified, of which 14 studies were included: six tested ChatGPT version 3.5, three tested version 4.0, three tested both versions, one used version 3.0, and one did not specify the version. Only half of the studies evaluated ChatGPT in real-world scenarios. A reasonable number of papers analyzed the use of ChatGPT in pharmacy practice, highlighting both benefits and limitations. The studies indicated that ChatGPT is not fully prepared for use in pharmacy practice due to significant limitations. However, there is great potential for its application in this context in the near future, following further improvements to the tool. Further exploration of its use in pharmacy practice is required, along with proposing its conscious and appropriate utilization.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) holds real promise for medicine and health, whether in scientific research, clinical practice, or education, but there are still major challenges to optimizing its use [1,2]. Among them, the use of AI-based natural language models (NLM) is increasing in healthcare-related contexts that have historically comprised human-to-human interaction, once using algorithms to understand and generate human-like conversations [3]. These models, such as Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) or Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), have reached state-of-the-art performance over most computerized language processing tasks such as web search, automatic translation, automatic content generation, and question-answering [4].

On 30 November 2022, OpenAI released for public use the version of its AI-based large language model (LLM) for text generation, the ChatGPT [5]. This tool is based on GPT models and is trained to generate text similar to human-generated text from several hundred billion words of a vast crawl of websites and datasets, allowing the model to learn the nuances of natural language and generate coherent text [6]. ChatGPT can be used in multiple contexts, such as chatbots, virtual assistants, and customer services [7].

The use of chatbots with GPT models is useful in the healthcare field, helping to provide accurate information and answers to patients and healthcare professionals [3,8,9,10]. In addition, these chatbots can provide clinical and educational support, such as answering frequent basic questions, reviewing concepts, taking examinations for higher education students [9,10,11,12], as well as assisting researchers in scientific writing, supporting them in generating ideas, and improving the writing of their articles [9,10,13,14]. However, some articles have warned against the use of this AI, highlighting that it can provide answers that are not clinically accurate or ethically appropriate [15,16], impair students’ ability to think critically and make informed decisions [17], and pose risks to academic integrity and copyright infringement (plagiarism) [18,19].

In this article, we have focused on the potential use of ChatGPT in pharmacy practice. Pharmacy practice encompasses the “interpretation, evaluation, and implementation of medical orders; the dispensing of prescription drug orders; participation in drug and device selection; drug administration; drug regimen review; the practice of telepharmacy within and across state lines; drug or drug-related research; the provision of patient counseling; the provision of those acts or services necessary to provide pharmacist care in all areas of patient care, including primary care and collaborative pharmacy practice; and the responsibility for compounding and labeling of drugs and devices, proper and safe storage of drugs and devices, and maintenance of required records” [20]. Despite its limitations and potential biases, a published editorial suggested that ChatGPT could offer several benefits for pharmacy practice, such as answering clinical questions, informing pharmacists, and educating patients [21]. However, to date, there is no scoping review which synthesizes the findings of studies that investigated the utility of ChatGPT in the pharmacy practice. Thus, this scoping review aimed to explore the utility of ChatGPT in pharmacy practice. A synthesis of manuscripts describing its use is important for identifying future research opportunities and understanding the added value and implications for decision-making.

2. Methods

A scoping review was performed to provide structured and detailed findings on using ChatGPT in pharmacy practice. This review was conducted following the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and the protocol was registered into the Open Science Framework platform (https://osf.io/f5bv7, accessed on 19 June 2024).

2.1. Databases and Search Strategy

A comprehensive search for relevant literature was conducted in the databases Medline (PubMed), Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, and LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature) until 23 May 2024, without date restriction and regardless of the study design and language. In addition, a manual search was carried out on the references of the selected studies. The full strategies search for all databases can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Study Selection

Eligible studies included original research that analyzed the use of ChatGPT by pharmacists within the context of pharmacy practice. Manuscripts that reported on ChatGPT through a descriptive approach, used other AI models, did not describe the use of ChatGPT, or excluded studies on the performance of ChatGPT in different fields of knowledge, were excluded. Preprints, reviews, comments, editorials, qualitative studies, chapters and books, and manuscripts that did not fit the review question were also excluded.

The manuscripts retrieved from the databases were allocated to the Rayyan QCRI web program [22] to exclude duplicate files (Phase 1), analyze the titles and abstracts of the articles (Phase 2), and analyze complete articles whose abstracts were previously selected (Phase 3). Two reviewers (T.M.L and M.B.V) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all studies identified by the searches and discussed any discrepancies arising from consensus. When it was not possible to obtain the full text, the corresponding authors were contacted via email or through the ResearchGate platform (www.researchgate.net, accessed on 10 July 2024).

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

The data were collected in a pre-formatted spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel®, including author; year; country; publication type (according to how it was indexed); study design (as described by authors); version/date of use of ChatGPT; context; objectives; the method used; outcome measures; main findings; and limitations. Two independent reviewers (M.B.V and T.M.L) extracted data, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. We also used Elicit (https://elicit.org/, accessed on 20 July 2024) and Scispace (https://scispace.com/, accessed on 20 July 2024) online tools to complement this process. A narrative and tabular synthesis of the results were provided according to the characteristics of the studies. The original ideas and concepts of the included studies were respected.

3. Results

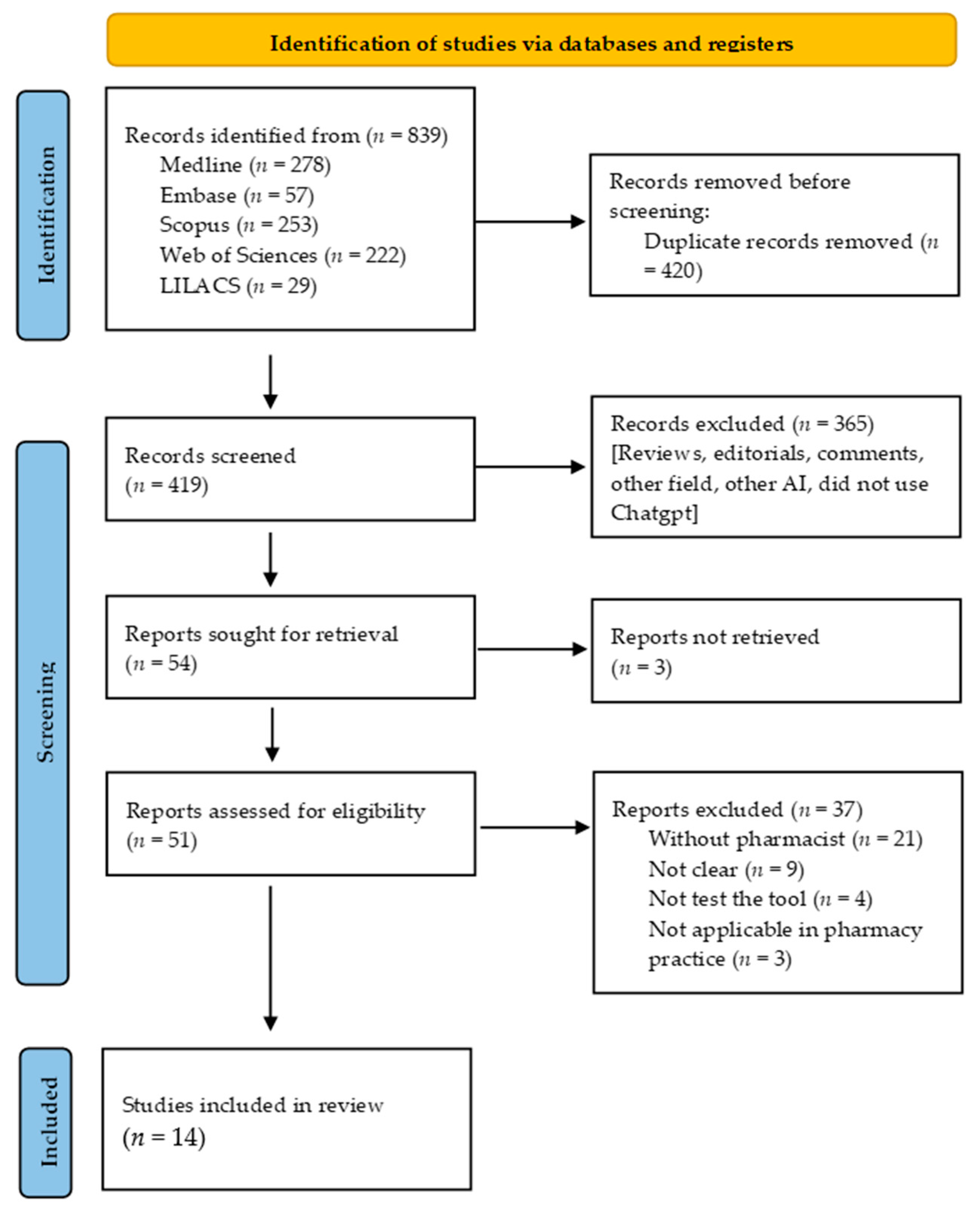

The electronic search identified 839 potentially relevant records. After removing duplicates and reviewing the titles and abstracts, 54 articles were selected for full-text examination. Three studies were not retrieved, and no relevant studies were identified in the reference lists of the included studies. Of these, 14 studies met the inclusion criteria for review [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the literature search.

Figure 1.

Study selection flowchart through literature search.

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

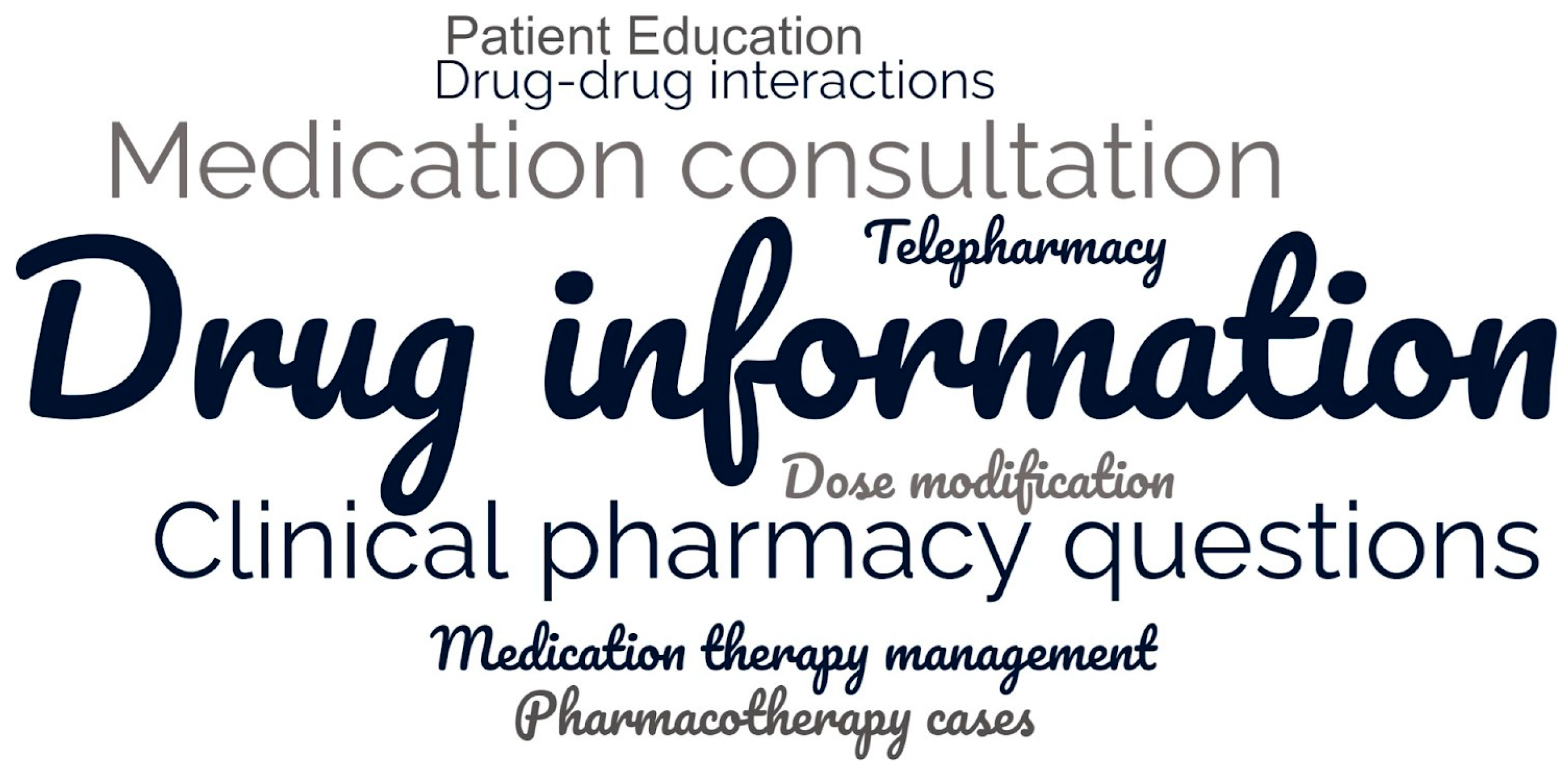

The characteristics of the fourteen studies included in this review are summarized in Table 1. All studies were published in English and reported between 2023 and 2024. Studies were conducted in Asia (n = 6) [23,24,25,28,29,34], North America (n = 4) [26,32,33,35], and Europe (n = 4) [27,30,31,36]. Thirteen studies [23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] were published as original articles (also called research articles and original research) and one as a brief report [26]. Study designs were classified as comparative studies (n = 5) [23,26,29,34,35], followed by cross-sectional studies (n = 3) [28,30,36]. Two studies did not specify the study design [32,33]. Six studies [24,28,29,32,34,36] used ChatGPT version 3.5, three studies [27,30,33] used version 4.0, and three studies [23,25,35] used both versions. One study used an older version [31], and another study did not describe the version used [26]. Four studies [30,31,34,35] tested ChatGPT in the drug information context, followed by clinical pharmacy questions [27,32] and medication consultation [28,29]. All contexts are illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

Figure 2.

Word cloud of contexts in which ChatGPT was tested. It was generated using the Word Clouds tool (available at https://www.wordclouds.com/, accessed on 10 August 2024).

3.2. Main Results of the Included Studies

Table 2 shows the objectives, methods and measured variables, main findings, and limitations of the fourteen studies included. The studies verified the utility of ChatGPT in: identifying drug interactions compared to recognized databases [23]; managing pharmacotherapy cases [24]; acting as a pharmacist in a service of telepharmacy [25]; creating patient education materials [26]; responding to questions asked to a pharmacist [27,28,34] or asked by pharmacists to other services [30]; resolving drug-related and pharmacy-based questions [31,32]; performing prescription review, patient medication education, adverse drug reaction recognition and causality assessment, and drug counseling [29]; optimizing medication therapy management [33]; providing drug safety information of non-prescription medications and supplements used by individuals with kidney disease [35]; intervening in the drug dose for hospitalized patients with renal dysfunction [36]. Only half of the studies evaluated ChatGPT in real-world scenarios [27,28,29,30,31,34,36].

Table 2.

Objectives, methods and measured variables, main findings, and limitations of the included studies.

Studies used several methods and measured variables to analyze ChatGPT. The studies that compared ChatGPT 4.0 with version 3.5 showed that version 4.0 has superior performance for pharmacy practice [23,25,35]. Moreover, some studies showed positive results with ChatGPT use: it was capable of generating clinically relevant pharmaceutical information [24]; ChatGPT maintained excellent accuracy in medication counseling [29]; ChatGPT answered 100% of the questions on pharmacy calculation correctly [32]; and ChatGPT successfully identified drug interactions, provided therapy recommendations, and formulated a general management plan in 100% of patient cases [33].

However, the studies also highlighted important limitations related to its use: a lack of a patient-centered and individualized approach that a human pharmacist would provide [25]; the variable accuracy scores prevent the routine use of ChatGPT to produce medication-related patient education materials at this time [26]; ChatGPT did not provide better answers than those recorded by the pharmacists, especially for prescription-related questions [27]; ChatGPT did not perform well on questions about drug–herb interactions and those related to the hospital setting [28]; ChatGPT was weak in prescription review, patient medication education, and adverse drug reaction recognition and causality assessments [29]; ChatGPT showed a lower accuracy in questions regarding drug causality [30]; ChatGPT answered the majority of real-world drug-related questions wrong or partly wrong [31]; ChatGPT scored low in drug information enhanced prompt and patient case categories [32]; ChatGPT exhibited a lower percentage of correct answers for drug–drug interactions, adverse drug effects, and for drug dosage [34]; ChatGPT did not show good concordance with Micromedex when used as drug information sources for medication safety of non-prescription medications and supplements in individuals with kidney disease [35]; and ChatGPT’s performance in clinical rule-guided dose interventions for hospitalized patients with renal dysfunction was poor [36]. Studies also addressed ethical concerns and privacy issues with sharing patient information with ChatGPT [25,27].

The main limitations reported by the studies included were: theoretical analyses that do not necessarily represent real-world scenarios [23,32,33,35], small sample sizes [24,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,34], comparison made with few databases [23,26,35], variable answers in different time points [24,31]. Additionally, since the tool is continually updated, the study results may no longer reflect the current performance of the tool at the time of reading the articles [23,36].

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to discuss the use of ChatGPT in pharmacy practice. Fourteen relevant studies were identified on this question. ChatGPT was tested in various contexts, including drug information, medication consultation, clinical pharmacy questions, pharmacotherapy cases, drug–drug interactions, telepharmacy, patient education, dose modification, and medication therapy management. However, only half of the studies evaluated ChatGPT’s performance in real-world scenarios. Researchers must be engaged in designing future studies with real-world data. Moreover, studies used various methods and measured variables to analyze ChatGPT, making them quite heterogeneous and producing different results. Methodological standardization is important to enable more reliable comparisons between studies. Finally, the studies showed that ChatGPT is not fully prepared for use in pharmacy practice as this AI still has important limitations; however, there is great potential for its use in this context in the near future after improvements to this tool.

A preview study sought to summarize studies on the use of ChatGPT in pharmaceutical services [37]. Although this is a narrative review and presents methodological flaws, the findings were similar to our study, showing that ChatGPT is a promising tool which can assist pharmacists with certain tasks, but it provides inaccurate and uncertain information, highlighting that the tool cannot replace professional pharmacists.

Three studies used both versions (3.5 and 4.0) of ChatGPT in their analysis, highlighting the superiority of version 4.0. Overall, ChatGPT-4.0 has a more current knowledge base due to a later data cut-off and benefits from more frequent updates and improvements compared to ChatGPT-3.5 (updated until September 2021) [7]. However, the recent version is paid, which could be a limiting factor for its use in daily practice. Pharmacists can benefit from similar AI models, such as Google Gemini and Microsoft Copilot, as they have more up-to-date databases than ChatGPT-3.5. Moreover, new studies should be performed to elucidate the differences between the versions of ChatGPT.

Drug information sources assist pharmacists in improving patient safety, minimizing drug-related issues to the patient, and rational use of drugs by both physician and patient [38]. Four studies tested the ChatGPT in this field. Although ChatGPT has the potential to deliver drug information, its current performance is unreliable, with a significant risk of patient harm due to inaccurate or incomplete content. In addition, two studies explore the potential of ChatGPT in answering clinical pharmacy questions. Both studies underscore the importance of continuous updates and refinements to improve the accuracy and safety of AI tools in clinical practice. On the other hand, two studies evaluated the performance of ChatGPT in medication consultation questions, suggesting that ChatGPT has the potential to be a valuable tool. Then, users should be cautious with the outputs generated by ChatGPT and use them carefully.

Surprisingly, only one study included in this review explored the use of ChatGPT to predict and explain drug–drug interactions. Compared with other AI models, ChatGPT had lower specificity and accuracy to provide this information for pharmacists. These findings were similar to those presented in another study that assessed ChatGPT’s ability to detect drug interactions using a simulated patient. ChatGPT is a partially effective tool for explaining common drug–drug interactions, with about 50% of the correct answers being inconclusive, emphasizing that further improvement is required for potential use by patients [39]. Pharmacists should use ChatGPT cautiously and compare their responses generated with other consolidated tools, such as Micromedex [40] and UptoDate [41].

Moreover, one study tested the ChatGPT for patient education involving pharmacists with promising results. It is known that patient education provided by pharmacists brings benefits, promoting autonomy, empowerment, and self-management [42]. The use of ChatGPT in patient education has demonstrated potential across various medical fields, including dermatology [43], ophthalmology [44], and general medical education [45], although there are concerns about the accuracy and potential bias of the information generated by ChatGPT as well as ethical concerns such as privacy issues. Future studies should focus on improving the capabilities of ChatGPT to assist the pharmacist in generating patient education.

Before applying it in pharmacy practice, it is very important to test the ChatGPT in real-world scenarios, as a barrier to its use is the uncertainty of how it behaves in clinical practice [46]. Future studies should further explore real-world scenarios, as well as utilize larger sample sizes, compare ChatGPT to a broader range of data sources, conduct longitudinal evaluations to assess ChatGPT’s accuracy over time, and standardize methodologies for evaluating the tool.

This scoping review has some limitations. Although a comprehensive literature search was used, some studies may have been missed because they were not indexed in the searched databases, published on the websites, or published in non-Roman characters. In addition, the number of publications regarding ChatGPT in the healthcare field is rapidly increasing within a brief timeframe. It is worth noting that some studies of interest that emerged after the set search period may not have been included.

5. Conclusions

ChatGPT has shown potential as a tool in pharmacy practice. However, certain concerns have been noted during its application. Whether ChatGPT represents a disruptive or destructive innovation depends on how it is integrated into pharmacy workflows. If used thoughtfully and ethically, it could be a disruptive innovation, positively transforming practices by improving efficiency and decision-making. On the other hand, if misused or relied upon excessively without proper oversight, it could lead to destructive outcomes. Further research is encouraged to gain a deeper understanding of the use of ChatGPT in real-world scenarios as well as to promote conscientious, appropriate, and ethical utilization.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/scipharm92040058/s1, Table S1: Electronic databases search strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.V., A.R.B. and T.d.M.L.; methodology, M.B.V. and T.d.M.L.; formal analysis, M.B.V. and T.d.M.L.; investigation, M.B.V., M.B. and T.d.M.L.; resources, M.B.V., A.R.B. and T.d.M.L.; data curation, M.B.V. and T.d.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.V., M.B. and T.d.M.L.; writing—review and editing, A.R.B.; visualization, M.B.V., A.R.B. and T.d.M.L.; supervision, M.B.V., A.R.B. and T.d.M.L.; project administration, M.B.V. and T.d.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Sao Paulo (USP) and Fluminense Federal University (UFF). A.R.B. is thankful to CNPq, for the Research Productivity Scholarship (Process 303862/2022-0), and to FAPESP (Process 2024/01920-0).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rajpurkar, P.; Chen, E.; Banerjee, O.; Topol, E.J. AI in Health and Medicine. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.S.; Zary, N. Applications and Challenges of Implementing Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Integrative Review. JMIR Med. Educ. 2019, 5, e13930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korngiebel, D.M.; Mooney, S.D. Considering the Possibilities and Pitfalls of Generative Pre-Trained Transformer 3 (GPT-3) in Healthcare Delivery. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, A.; PourNejatian, N.; Shin, H.C.; Smith, K.E.; Parisien, C.; Compas, C.; Martin, C.; Costa, A.B.; Flores, M.G.; et al. A Large Language Model for Electronic Health Records. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, N.; Cherian, J.M.; Sudharson, N.A.; Varghese, K.G.; Wadhwa, S. AI Is Now Everywhere. Br. Dent. J. 2023, 234, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Lin, Y. The Benefits and Challenges of ChatGPT: An Overview. FCIS 2023, 2, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Introducing the OpenAI API. Available online: https://openai.com/product (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Moons, P.; Van Bulck, L. ChatGPT: Can Artificial Intelligence Language Models Be of Value for Cardiovascular Nurses and Allied Health Professionals. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2023, 22, e55–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns. Healthcare 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, T.; Athaluri, S.A.; Singh, S. ChatGPT in Medicine: An Overview of Its Applications, Advantages, Limitations, Future Prospects, and Ethical Considerations. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1169595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.; Tan, S.; Tan, S. ChatGPT: Bullshit Spewer or the End of Traditional Assessments in Higher Education? J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6, 342–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurzo, A.; Strunga, M.; Urban, R.; Surovková, J.; Afrashtehfar, K.I. Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Dental Education: A Review and Guide for Curriculum Update. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S. ChatGPT and the Future of Medical Writing. Radiology 2023, 307, e223312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, N. To ChatGPT or Not to ChatGPT? The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Academic Publishing. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahan, P.; Treutlein, B. A Conversation with ChatGPT on the Role of Computational Systems Biology in Stem Cell Research. Stem Cell Rep. 2023, 18, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.R. The Future of AI in Medicine: A Perspective from a Chatbot. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 51, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, S. ChatGPT Open Artificial Intelligence Platforms in Nursing Education: Tools for Academic Progress or Abuse? Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 66, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebrenz, M.; Schleifer, R.; Buadze, A.; Bhugra, D.; Smith, A. Generating Scholarly Content with ChatGPT: Ethical Challenges for Medical Publishing. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e105–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dis, E.A.M.; Bollen, J.; Zuidema, W.; Van Rooij, R.; Bockting, C.L. ChatGPT: Five Priorities for Research. Nature 2023, 614, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resources. National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Available online: https://nabp.pharmacy/news-resources/resources/ (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Jairoun, A.A.; Al-Hemyari, S.S.; Shahwan, M.; Humaid Alnuaimi, G.R.; Zyoud, S.H.; Jairoun, M. ChatGPT: Threat or Boon to the Future of Pharmacy Practice? Res. Social. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 975–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ashwal, F.Y.; Zawiah, M.; Gharaibeh, L.; Abu-Farha, R.; Bitar, A.N. Evaluating the Sensitivity, Specificity, and Accuracy of ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, Bing AI, and Bard Against Conventional Drug-Drug Interactions Clinical Tools. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 2023, 15, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dujaili, Z.; Omari, S.; Pillai, J.; Al Faraj, A. Assessing the Accuracy and Consistency of ChatGPT in Clinical Pharmacy Management: A Preliminary Analysis with Clinical Pharmacy Experts Worldwide. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 1590–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzari, F.H.; Bazzari, A.H. Utilizing ChatGPT in Telepharmacy. Cureus 2024, 16, e52365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covington, E.W.; Watts Alexander, C.S.; Sewell, J.; Hutchison, A.M.; Kay, J.; Tocco, L.; Hyte, M. Unlocking the Future of Patient Education: ChatGPT vs. LexiComp® as Sources of Patient Education Materials. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2024, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, A.; Fallet, C.; Sadeghipour, F.; Perrottet, N. Assessing the Applicability and Appropriateness of ChatGPT in Answering Clinical Pharmacy Questions. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2024, 82, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-Y.; Hsu, K.-C.; Hou, S.-Y.; Wu, C.-L.; Hsieh, Y.-W.; Cheng, Y.-D. Examining Real-World Medication Consultations and Drug-Herb Interactions: ChatGPT Performance Evaluation. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e48433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Estau, D.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Qin, J.; Li, Z. Evaluating the Performance of ChatGPT in Clinical Pharmacy: A Comparative Study of ChatGPT and Clinical Pharmacists. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montastruc, F.; Storck, W.; de Canecaude, C.; Victor, L.; Li, J.; Cesbron, C.; Zelmat, Y.; Barus, R. Will Artificial Intelligence Chatbots Replace Clinical Pharmacologists? An Exploratory Study in Clinical Practice. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 79, 1375–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morath, B.; Chiriac, U.; Jaszkowski, E.; Deiß, C.; Nürnberg, H.; Hörth, K.; Hoppe-Tichy, T.; Green, K. Performance and Risks of ChatGPT Used in Drug Information: An Exploratory Real-World Analysis. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, F.; Gehres, A.; Wai, D.; Song, L. Evaluation of ChatGPT as a Tool for Answering Clinical Questions in Pharmacy Practice. J. Pharm. Pract. 2024, 37, 8971900241256731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosan, D.; Padua, P.; Khan, R.; Khan, H.; Verzosa, C.; Wu, Y. Effectiveness of ChatGPT in Clinical Pharmacy and the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Medication Therapy Management. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. (2003) 2024, 64, 422–428.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, A.H. The Promise and Challenges of ChatGPT in Community Pharmacy: A Comparative Analysis of Response Accuracy. Pharmacia 2024, 71, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.S.; Barreto, E.F.; Miao, J.; Thongprayoon, C.; Gregoire, J.R.; Dreesman, B.; Erickson, S.B.; Craici, I.M.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Evaluating ChatGPT’s Efficacy in Assessing the Safety of Non-Prescription Medications and Supplements in Patients with Kidney Disease. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241248082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nuland, M.; Snoep, J.D.; Egberts, T.; Erdogan, A.; Wassink, R.; van der Linden, P.D. Poor Performance of ChatGPT in Clinical Rule-Guided Dose Interventions in Hospitalized Patients with Renal Dysfunction. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 80, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noviani, L.; Rachmawati, P.; Irawan, A. A Literature Review: Chatgpt, What Will the Future of Pharmacy Practice Bring—A Threat or a Benefit? J. Popl. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 30, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation. mHealth—Use of Mobile Health Tools in Pharmacy Practice. Available online: https://www.fip.org/files/content/publications/2019/mHealth-Use-of-mobile-health-tools-in-pharmacy-practice.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Juhi, A.; Pipil, N.; Santra, S.; Mondal, S.; Behera, J.K.; Mondal, H. The Capability of ChatGPT in Predicting and Explaining Common Drug-Drug Interactions. Cureus 2023, 15, e36272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micromedex. Available online: https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/ (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- UpToDate. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/ (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Pulvirenti, M.; McMillan, J.; Lawn, S. Empowerment, patient centred care and self-management. Health Expect. 2014, 17, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, H.; Mondal, S.; Podder, I. Using ChatGPT for Writing Articles for Patients’ Education for Dermatological Diseases: A Pilot Study. Indian. Dermatol. Online J. 2023, 14, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momenaei, B.; Mansour, H.A.; Kuriyan, A.E.; Xu, D.; Sridhar, J.; Ting, D.S.W.; Yonekawa, Y. ChatGPT enters the room: What it means for patient counseling, physician education, academics, and disease management. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2024, 35, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, B.; Supti, T.; Alzubaidi, M.; Shah, H.; Alam, T.; Shah, Z.; Househ, M. The Pros and Cons of Using ChatGPT in Medical Education: A Scoping Review. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2023, 305, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Montomoli, J.; Bellini, V.; Bignami, E. Evaluating the Feasibility of ChatGPT in Healthcare: An Analysis of Multiple Clinical and Research Scenarios. J. Med. Syst. 2023, 47, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Österreichische Pharmazeutische Gesellschaft. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).