Abstract

Long COVID is defined as “the continuation or development of new symptoms 3 months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, with these symptoms lasting for at least 2 months with no other explanations”, as reported by the World Health Organization. A growing number of people are dealing with a variety of lingering symptoms even after recovering from an acute infection. These can include fatigue, muscle pain, shortness of breath, headaches, cognitive issues, neurodegenerative symptoms, anxiety, depression, and a feeling of hopelessness, and therapeutic options for long COVID are investigated. The potential of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) to improve chronic fatigue, cognitive impairments, and neurological disorders has been established; therefore, the use of HBOT to treat long COVID has also been studied. The aim of this literature search is to analyze the state of the art of a potential role of HBOT to improve chronic fatigue, cognitive impairments and neurological disorders. A literature analysis was performed, focusing on the clinical efficacy of HBOT for treating long COVID symptoms. The results from January 2021 to October 2025, using a standard registry database, showed 21 studies, including one case report, ten randomized controlled trial, eight systematic reviews and three studies regarding the molecular mechanism and markers changing after HBOT. They suggested that HBOT can improve quality of life, fatigue, cognition, neuropsychiatric symptoms and cardiopulmonary functions. HBOT is a safe treatment and has shown some benefits for long COVID symptoms. To precisely define indications, protocols, and post-treatment evaluations, we need to conduct more in-depth, large-scale studies.

1. Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the virus responsible for the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which has had a significant impact on health and well-being around the globe. As of March 2025, there have been over 777 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and roughly 7 million related deaths reported worldwide [1]. In terms of clinical presentation, COVID-19 primarily shows up with respiratory symptoms, but it can also lead to a wide range of complications outside the respiratory system. Among these, acute neurological issues affecting both the central and peripheral nervous systems have been noted, including problems with smell and taste, dizziness, polyneuropathies, and, in rarer cases, encephalitis and cerebrovascular incidents [2]. Recent studies show that about one-third of patients continue to experience neurobehavioral issues within the first six months after an acute infection [3]. Additionally, a significant number of people recovering from COVID-19—whether they had mild symptoms or were asymptomatic—report ongoing issues, which are grouped together under the term post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC), often referred to as “long COVID” [4,5]. This condition is a major and persistent public health challenge, with estimates suggesting that 10–30% of non-hospitalized individuals and 50–70% of those who were hospitalized may be affected [6]. Patients who show neurological symptoms—like issues with smell and taste (anosmia and dysgeusia), cognitive difficulties often called “brain fog,” trouble sleeping, overall weakness, and psychological challenges that can diminish both physical and mental well-being—are affected by NeuroCOVID [7,8]. There is an increasing amount of research highlighting a variety of neurological and neuropsychological problems linked to SARS-CoV-2 infection, which is helping to shed light on how COVID-19 affects the nervous system [9]. One of the most reported issues after a SARS-CoV-2 infection is olfactory dysfunction, which stands out as a significant and unique symptom. In comparison, typical upper respiratory viral infections—like those caused by the influenza virus, rhinovirus, and other human coronaviruses—usually lead to conductive olfactory dysfunction. This happens due to localized inflammation and swelling in the nasal mucosa [10]. Around two-thirds of patients who experience a loss of smell more than two years after their COVID-19 show either complete or partial recovery within three years. However, the remaining one-third still struggle with ongoing symptoms [11]. The exact molecular mechanisms behind the olfactory issues linked to COVID-19 are still not completely understood. Current research indicates that this condition arises from a mix of factors, such as the virus invading the olfactory epithelium, neuroinflammation caused by cytokines that impact olfactory neurons, disruption in neurotransmitter release, and vascular damage that leads to a lack of oxygen and nutrients in the olfactory cells. Additionally, there is a persistent pro-inflammatory environment with continuous cytokine production [12]. Gaining a clear understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 infection affects the olfactory system is crucial for developing effective treatments aimed at restoring normal smell function [12,13,14]. Although most people recover fully from COVID-19, 6–12% of adults develop longer-lasting symptoms [15]. World Health Organization defined long COVID as “the continuation or development of new symptoms 3 months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, with these symptoms lasting for at least 2 months with no other explanation” [16]. Patients develop ongoing persistent symptoms including dyspnea, cough, fatigue, “brain fog”, cognitive dysfunction, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, palpitations, postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and rashes that continue for more than 12 weeks not explained by another alternative diagnosis [16]. Long COVID syndrome is well described worldwide with symptoms affecting quality of life and work–life. The exact causes of long COVID are debated and it is likely that multiple mechanisms are involved [17]. Moreover, factors like viral persistence, hypercoagulability, immune system issues, autoimmunity, and hyperinflammation have all been proposed; there are currently no effective treatment protocols that address the underlying problems associated with long COVID [16]. Available therapeutic choices for long COVID are largely insufficient, and a multidisciplinary assessment is often required in the management of those symptoms. COVID-19 alters the oxidative phosphorylation process in mitochondria, which may contribute to the onset of chronic neurological disorders associated with the infection [18]. Recent studies also reveal that nearly a third of COVID-19 patients develop long-term neurological problems, highlighting the crucial importance of studying mitochondrial mechanisms to mitigate the long-term neurological effects of COVID-19 [18]. Higher antioxidant activity has been observed to be associated with greater protection against COVID-19 infection. Compounds with antioxidant properties, which support mitochondrial balance, have been shown to improve the condition of COVID-19 patients [18]. Mitochondrial biological markers, including the amount of mtDNA, electron transport chain enzyme complexes, lactate and CoQ10 levels, and indicators of oxidative stress, are promising as indicators of disease severity and prognosis in COVID-19 patients who experience neurological problems [19]. Aging further exacerbates mitochondrial dysfunction, increasing susceptibility to severe forms of COVID-19 and associated neurological complications [20]. Therefore, addressing mitochondrial dysfunction represents a potential therapeutic approach to managing COVID-19-associated neurological symptoms [20]. Recent studies have shown that patients undergoing HBOT experienced notable improvements in various areas, including overall cognitive function, fatigue levels, attention span, executive function, energy, sleep quality, psychiatric symptoms, cardiopulmonary health, endurance, and pain management. HBOT is a non-invasive treatment that involves breathing 100% oxygen in a pressurized chamber. As the pressure rises, more oxygen gets dissolved into the blood plasma, which boosts the oxygen supply to the tissues [21]. HBOT demonstrated its benefits in neurological disorders and other syndromes characterized by chronic fatigue too [21]. HBOT has the potential to lower oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, enhance endothelial function, and ease long COVID symptoms. By boosting the amount of oxygen that gets dissolved in body tissues, the combined effects of hyperoxia and hyperbaric pressure can activate genes that respond to oxygen and pressure. This, in turn, sparks regenerative processes like the proliferation and mobilization of stem cells, along with the release of anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory factors, angiogenesis, and neurogenesis [22]. HBOT can improve cerebral blood flow, and it can induce neuroplasticity, improve cognitive function and reduce symptoms of long COVID [22]. All of this explains why the use of HBOT can provide significant benefits and could become a clinical treatment for those long COVID conditions that do not respond to other medical symptomatic therapies, with a significant improvement in global cognitive function, fatigue, attention, executive function, energy, sleep, psychiatric symptoms, cardiopulmonary function, endurance and pain. Here we aim to better investigate the state of the art and the efficacy and safety of HBOT for long COVID symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

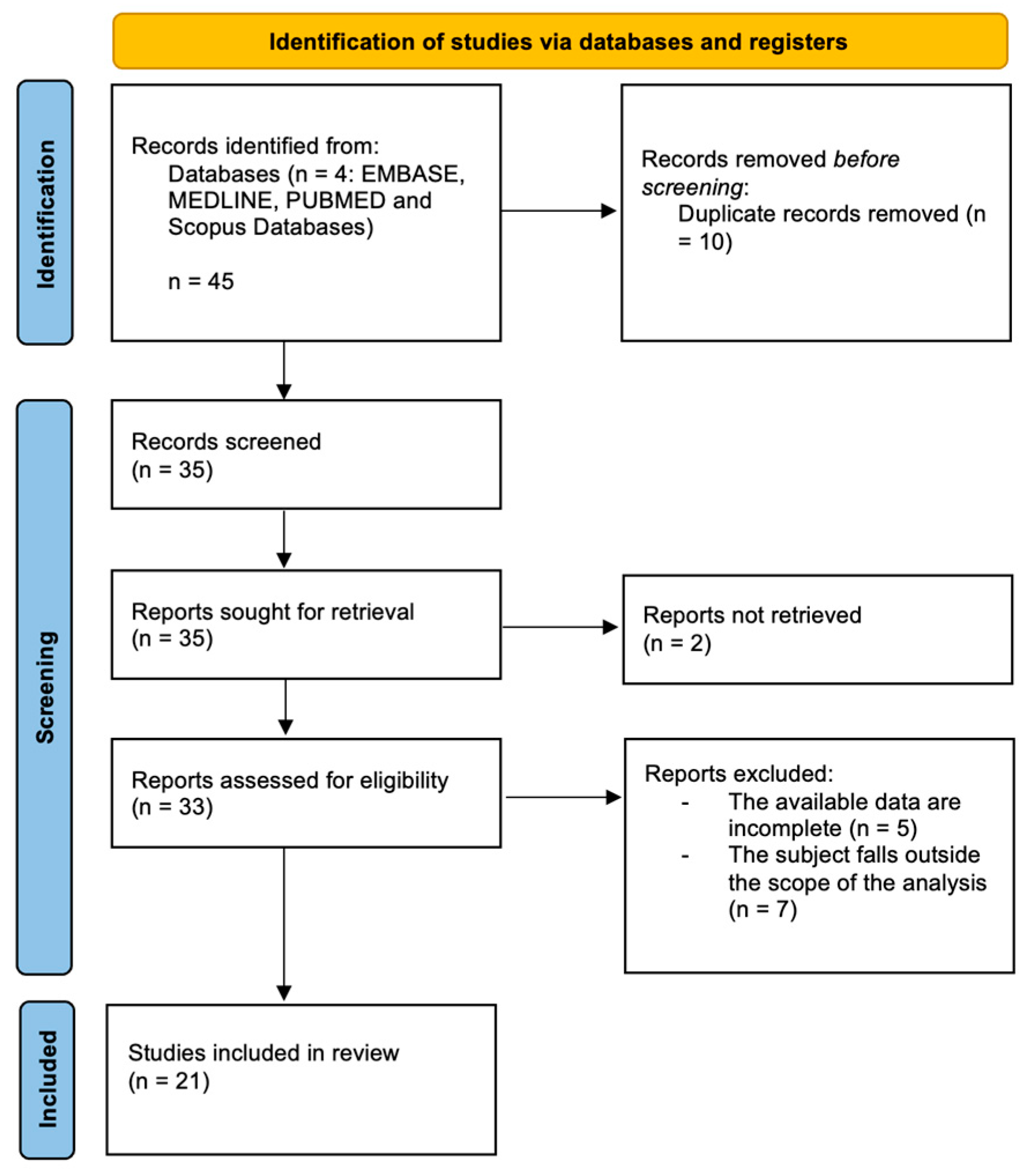

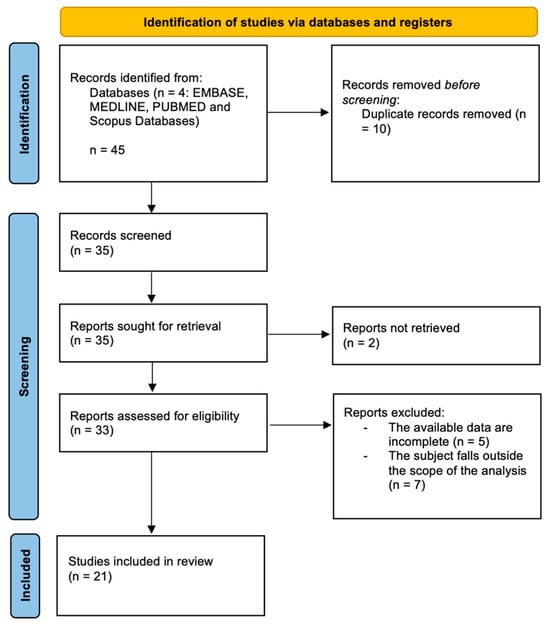

A scoping review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. A literature search was performed using MEDLINE, EMBASE, PUBMED and Scopus Databases. The search strategy was conducted using the following terms: long COVID AND hyperbaric oxygen therapy OR HBOT. Study selection: the results were extrapolated from January 2021 and October 2025. All the clinical and case reports included an abstract available in English language, description of referred symptoms, treatment performed, outcome and follow-up on individual patients. We excluded articles with lacking information. This review included randomized controlled trials, observational studies, case reports and systematic reviews enrolling human participants with long COVID characterized by fatigue, myalgia, dyspnea, headache, cognitive impairment, neurodegenerative symptoms, anxiety, depression, and sense of despair, which were treated with HBOT. This review is limited to human studies and research papers written in English. Abstracts, reviews, editorials, and opinion articles without data were excluded. Title and abstract were watchfully examined by two authors (F.Z. and C.F.) independently, and disagreements were resolved by a discussion with a third author (F.P.). Full text of the included studies was reviewed, and data extraction was performed using a standard registry database. Epidemiologic and clinicopathologic data, registered in each study, included age, sex, clinical symptoms, treatment performed, outcome and follow-up. Studies were considered for inclusion if they included adults (aged 18 years and over) who suffered from the continuation or development of new symptoms three months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection. We included studies that investigated how hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) affects long COVID in our analysis. However, we decided to leave out any studies that met any of these criteria: (1) those not focused on long COVID; (2) those missing important safety and efficacy information about HBOT; (3) abstracts, editorials, or letters; (4) duplicate studies.

3. Results

The search algorithm and review results, following PRISMA 2020 guidelines, are outlined in Figure 1. The initial search found 45 studies on the MEDLINE, EMBASE, PUBMED and Scopus databases. The removal of duplicates identifies 35 publications. All 35 papers were screened in title and abstract, and 33 manuscripts were reviewed in full text. Of these, 21 studies meet the inclusion criteria, while the remaining 12 studies were excluded. The included studies are heterogeneous, so a formal meta-analysis could not be appropriately performed. The data collected from each study were transcribed in a tabular form. Of the 21 studies selected, one was a case report [23], 10 were randomized controlled trials (Table 1), seven were systematic reviews (Table 2) and three studies regarding the molecular mechanism and markers changing after HBOT (Table 3). Several differences can be identified among the studies: some report positive results, others do not. A general summary can be reported as follows.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow-chart.

Table 1.

Randomized controlled trial evaluated in the text.

Table 2.

Systematic reviews evaluated in the manuscript.

Table 3.

Studies regarding the molecular mechanism and markers changing after HBOT.

3.1. HBOT Protocol

There were significant differences in HBOT treatment protocols among the several investigations included (see Table 1). The methods of HBOT therapy vary throughout the studies (see Table 1 and Table 2). The length of each session, the total number of sessions, and the timing of the therapy following a COVID-19 infection all depend on the pressure that is applied. The studies that used pressures usually more than 2.0 ATA and longer treatment plan had better results. On the other hand, the studies that used lower pressures or did not treat people for as long did not produce promising findings. The interval between contracting COVID-19 and initiating HBOT varies across studies, making it difficult to compare the effects of HBOT. In conclusion, since a universal protocol for the management of patients with post-COVID-19 sequelae using HBOT has not yet established, it is difficult to achieve an effective comparison among the different populations analyzed in the studies reported in our literature search.

Characteristics of Patients: The recruited patients in different studies were all quite different. Some studies included adult patients, while others included younger patients. In addition, the number of males and females in each trial varied. COVID-19 symptoms patients experienced when they first became ill also differed among studies. Some patients referred severe symptoms, others milder symptoms. They also had other co-morbidities. The main problems that patients had after they got COVID-19 were different in each study. Several studies focused on issues with thinking and feeling exhausted. Studies that looked at patients who still had problems with not getting oxygen to their tissues or problems with small blood vessels often had better results with HBOT COVID-19 treatment. COVID-19 patients who experienced these issues were more likely to respond to therapy. Some studies looked at people of certain ages or genders but this was not done very often. The sample sizes for these studies by age or gender were just too small to make strong comparisons between subgroups, like age or gender. (see Table 1 and Table 2). Across the studies included in this review, individual patient clinical characteristics were frequently unreported, with most articles providing only aggregate descriptions of symptoms that improved or not following HBOT. This heterogeneity in reporting, together with the lack of standardized outcome measures and treatment protocols, substantially limits comparability across studies and increases the risk of bias. Consequently, while symptom-specific treatment effects may be inferred, universally generalizable conclusion cannot be drawn.

3.2. Outcome Results

The reported results were influenced by differences in measurements taken in different studies. Consistent changes in results can be observed based on subjects’ self-reported information, such as their reasoning ability, level of fatigue, and level of well-being. Physical parameters, such as lung function tests and imaging studies, do not show significant changes after the use of HBOT. The fact that the trials [29,35] are still ongoing and did not all follow up with the people over time could have also made it harder to figure out what the results really meant and to compare them to each other. Here we are looking at the effects of HBOT, and the results of HBOT can be different as we can see in the conclusions reported among Table 1 and Table 2. Hadanny et al. [24], van Berkel et al. [25], Robbins et al. [27], Zant et al. [28], Leitman et al. [30], Gonevski et al. [32] and Lindenmann et al. [33], Mrakic-Sposta et al. [39], Pan et al. [40], and Jermakow et al. [41] all reported positive outcomes following HBOT in the patient cohorts, with statistically significant improvements observed in quality of life, cognitive abilities, attention, left ventricular systolic function, and physical fatigue. These outcomes pertain to symptoms that had worsened following COVID-19. Conversely, Kjellberg et al. [26] described high frequency of adverse events following HBOT and D’Hoore et al. [31] reported no significant differences in subjective symptoms, functional scores, and cognitive performance between any groups analyzed.

3.3. Design of the Study

One more cause of variability in stated results found was study design. Uncontrolled tests and observational studies reported favorable impacts of HBOT more often than did randomized controlled trials, especially those using placebo treatments. Inconsistencies across the literature were exacerbated by sample size constraints and methodical heterogeneity as well. Future research should prioritize well-designed, standardized studies with larger sample sizes and clearly defined clinical and methodological parameters to adequately assess the efficacy of structured HBOT treatment protocols.

4. Discussion

Research on long COVID has had a slow and challenging start, and there is still not a full understanding of its complex biological processes. One proposed explanation involves immune system issues, such as abnormal T-cell activity, changes in gut bacteria, autoimmune reactions, problems with blood vessel function, issues with mitochondrial health, lingering virus, or problems with brain signaling [25]. All these changes may lead to the development of highly heterogeneous symptoms, which nonetheless share a common denominator: the underlying COVID-19 infection.

4.1. Neurological Symptoms

A potential explanation of the persistence of neurological symptoms, for example, might be an association with dysautonomia or autonomic dysfunction, caused by a malfunction of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) [42]. Dysautonomia contributes to cerebral hypoperfusion that leads to an overactive sympathetic system and concomitant reduced parasympathetic activity [43,44].

Because of the lack of clear understanding, treatment options for long COVID are limited and no standard therapy has been established. These patients could benefit from vagal nerve stimulation and oxygen treatment [45]. In fact, there is a growing need to find more effective treatments for this condition. Common approaches include ways to manage symptoms, rest, and coping strategies [41].

4.2. Actual Application and Potential Role of HBOT

In the search for an effective treatment, hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) has emerged as a promising option due to its potential to address the effects of COVID-19. Several studies have shown impressive improvements in various areas, such as quality of life, physical health, memory, concentration, and heart and lung function (see Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3). Many studies have highlighted the effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) in helping post-COVID-19 patients with cognitive issues, likely by improving brain plasticity and reducing brain inflammation. HBOT has been used in clinical settings since 1957 for conditions like heart surgery, decompression sickness, carbon monoxide poisoning, air embolism, and infections that thrive without oxygen. This therapy involves breathing in nearly 100% oxygen inside a pressurized chamber, which is more than two times the normal atmospheric pressure. This allows oxygen to dissolve in the blood at levels about 11–14 times higher than under normal conditions. The shift between high oxygen and normal oxygen levels helps the body improve oxygen delivery to areas with low oxygen, supports tissue repair and growth, and helps control inflammation. Currently, HBOT is recognized for treating conditions like diabetic foot ulcers, radiation injury, and decompression sickness. On a molecular level, HBOT increases oxygen levels in tissues and activates genes involved in regenerative processes, such as stem cell growth, anti-inflammatory pathways, new blood vessel formation, and better mitochondrial function [46]. Moreover, HBOT can affect blood flow to the brain and its structure, which supports brain plasticity and cognitive abilities [47]. Randomized controlled trials have further confirmed the therapeutic benefits of HBOT for post-COVID-19 patients, helping to relieve a range of ongoing physical, cognitive, and psychological symptoms, including issues with memory, heart function, and changes in brain connections [48].

4.3. Molecular Mechanisms of COVID-19 Acute Phase

Many of the studies we looked at suggest that hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) can be very helpful in managing long COVID symptoms. To better understand this, we need to consider the acute phase of COVID-19, marked by widespread inflammation, increased clotting, and blockages in both central and peripheral blood vessels (see Table 3). This widespread inflammatory response, often called a cytokine storm, is characterized by high levels of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α. These factors can lead to small areas of tissue death and inflammation in the brain, causing localized oxygen shortages [35].

4.4. What About Long COVID?

Long COVID, when symptoms last more than three months after a probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, often includes issues like memory problems, fatigue after exertion, sleep issues, loss of taste and smell, and other systemic challenges. Data shows that out of 80 million people infected between 2020 and 2023, about 54% reported ongoing fatigue, often along with physical pain, cognitive struggles, or breathing issues three months after their infection [35]. Among Italian patients, 53% reported fatigue and 22% reported chest pain after two months; in a British group of 100 survivors, more than two-thirds had persistent fatigue after 4–8 weeks [35]. Like chronic fatigue syndrome, pro-inflammatory components through cytokines like TNF-α and IL-7 are also thought to impair the normal function of the central nervous system in post-COVID syndrome, leading to the various symptoms mentioned [35]. Since HBOT is increasingly used in several neurological diseases and syndromes with chronic fatigue or cognitive issues, it would make sense to apply this therapy to post and long COVID patients [35]. In fact, most studies found that HBOT can improve quality of life, fatigue, cognition, mental health symptoms, and heart and lung function.

4.5. What Could Be Future Directions in Therapy?

Even though the cause of long COVID is largely unknown, viral persistence, increased clotting, immune dysfunction, autoimmune reactions, and excessive inflammation have been proposed as possible causes [49]. Considering our current understanding of long COVID symptoms, HBOT has emerged as a potential treatment option [50]. The overall hypothesis about how HBOT helps long COVID is that it can reduce oxidative stress and long-term inflammation, improve issues with blood vessel function, and thus alleviate symptoms of long COVID. HBOT increases the amount of oxygen dissolved in body tissues; the combined effect of high oxygen and high pressure can trigger genes that respond to oxygen and pressure, leading to regenerative processes like stem-cell growth and anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic factors, new blood vessel growth, and brain cell growth [51]. HBOT can improve blood flow to the brain’s affected areas and maintain the integrity of brain structures, therefore supporting brain plasticity and improving cognitive function. Additionally, HBOT has positive effects on mitochondrial function, a key part of proper muscle function. It can also increase the number of satellite cells and regenerate muscle fibers, which promotes muscle strength. In previously published studies reviewed in this paper, HBOT has been shown to reduce inflammatory responses and cytokine levels, decrease tissue damage by lowering oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species, improve immune system function, and work together with antibiotics to have a synergistic effect against infections. It can also reduce platelet activation and aggregation in the lungs and improve lung tissue microcirculation. Although HBOT has shown several benefits for prolonged COVID symptoms, it is still difficult to debate whether HBOT treatment for prolonged COVID is effective or not. It has been shown to be effective in reducing or modifying many multi-organ symptoms in a lasting way and without side effects, but more rigorous large-scale randomized clinical trials are needed to establish guidelines, treatment protocols, and post-treatment assessments. We believe that the difficulty in diagnosing the syndrome and the lack of access to many healthcare facilities that offer hyperbaric chambers as a therapeutic option prevent clinicians from providing specific recommendations. [52].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.B. and A.M.; Methodology: F.Z., F.C. and M.d.V.; Data curation: F.P., C.F. and C.P.; Writing—original draft preparation: F.Z.; Writing—review and editing: F.Z. and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge financial support under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.1, Call for tender No. 104 published on 2 February 2022 by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR), funded by the European Union-NextGenerationEU-Project Title-Mapping NEUROCOVID via neurobiology and neurovolatilome in Post-COVID-19 patients-CUP B53D23018450006-Grant Assignment Decree No. 1110 adopted on 20 July 2023 by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Corona-Virus (COVID-19) Dashboard > About [Dashboard]. 2023. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/more-resources (accessed on 1 February 2026).

- Pennacchia, F.; Zoccali, F.; Petrella, C.; Talarico, G.; Rusi, E.; Zingaropoli, M.A.; Ruqa, W.A.; Bruno, G.; Capuano, R.; Catini, A.; et al. Insight into NeuroCOVID: Neurofilament light chain (NfL) as a biomarker in post-COVID-19 patients with olfactory dysfunctions. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Ssentongo, P.; Ba, D.M. Association of Long COVID with mental health disorders: A retrospective cohort study using real-world data from the USA. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e079267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Author Correction: Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groff, D.; Sun, A.; Ssentongo, A.E.; Ba, D.M.; Parsons, N.; Poudel, G.R.; Lekoubou, A.; Oh, J.S.; Ericson, J.E.; Ssentongo, P.; et al. Short-term and Long-term Rates of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2128568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, S.; Hosoya, T.; Iwai, H.; Yasuda, S. Long COVID: Mechanisms of disease, multisystem sequelae, and prospects for treatment. Immunol. Med. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Davis, H.; McCorkell, L.; Soares, L.; Wulf-Hanson, S.; Iwasaki, A.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2148–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbato, C.; Petrella, C.; Minni, A. Insights into Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of NeuroCOVID. Cells 2024, 13, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, A.; Shah, M.; Ahmad, S.A.; Premraj, L.; Wildi, K.; Li Bassi, G.; Pardo, C.A.; Choi, A.; Cho, S.M. Pathogenesis Underlying Neurological Manifestations of Long COVID Syndrome and Potential Therapeutics. Cells 2023, 12, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Ruqa, W.; Barbato, C.; Minni, A. Long-term neurological and otolaryngological sequelae of COVID-19: A retrospective study. Explor. Med. 2025, 6, 1001310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscolo-Rizzo, P.; Spinato, G.; Hopkins, C.; Marzolino, R.; Cavicchia, A.; Zucchini, S.; Borsetto, D.; Lechien, J.R.; Vaira, L.A.; Tirelli, G. Evaluating long-term smell or taste dysfunction in mildly symptomatic COVID-19 patients: A 3-year follow-up study. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2023, 280, 5625–5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Zaikos, T.; Kilner-Pontone, N.; Ho, C.Y. Mechanisms of COVID-19-associated olfactory dysfunction. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2024, 50, e12960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bartheld, C.S.; Butowt, R. New evidence suggests SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasion along the nervus terminalis rather than the olfactory pathway. Acta Neuropathol. 2024, 147, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruqa, W.A.; Pennacchia, F.; Rusi, E.; Zoccali, F.; Bruno, G.; Talarico, G.; Barbato, C.; Minni, A. Smelling TNT: Trends of the Terminal Nerve. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Long COVID Collaborators; Hanson, S.W.; Abbafati, C.; Aerts, J.G.; Al-Aly, Z.; Ashbaugh, C.; Ballouz, T.; Blyuss, O.; Bobkova, P.; Bonsel, G.; et al. Estimated global proportions of individuals with persistent fatigue, cognitive, and respiratory symptom clusters following symptomatic COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021. JAMA 2022, 328, 1604–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A Long COVID Definition: A Chronic, Systemic Disease State with Profound Consequences; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.E.; Gurdasani, D.; Helbok, R.; Ozturk, S.; Fraser, D.D.; Filipović, S.R.; Peluso, M.J.; Iwasaki, A.; Yasuda, C.L.; Bocci, T.; et al. COVID-19-associated neurological and psychological manifestations. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2025, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, H.B.; Durhuus, J.A.; Andersen, O.; Straten, P.T.; Rahbech, A.; Desler, C. Mitochondrial dysfunction in acute and post-acute phases of COVID-19 and risk of non-communicable diseases. npj Metab. Health Dis. 2024, 2, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hingole, P.; Saha, P.; Das, S.; Gundu, C.; Kumar, A. Exploring the role of mitochondrial dysfunction and aging in COVID-19-Related neurological complications. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Ozigbo, A.A.; Varon, J.; Halma, M.; Laezzo, M.; Ang, S.P.; Iglesias, J. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species: A Unifying Mechanism in Long COVID and Spike Protein-Associated Injury: A Narrative Review. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.A.; Wainwright, S.; Kelly, M.P.; Albert, P.; Byrne, R. Hyperbaric oxygen effectively addresses the pathophysiology of long COVID: Clinical review. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1354088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.Q.; Liu, D.Y.; Shen, T.C.; Lai, Y.R.; Yu, T.L.; Hsu, H.L.; Lee, H.M.; Liao, W.C.; Hsia, T.C. Effects of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy on Long COVID: A Systematic Review. Life 2024, 14, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaiyat, A.M.; Sasson, E.; Wang, Z.; Khairy, S.; Ginzarly, M.; Qureshi, U.; Fikree, M.; Efrati, S. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment for long coronavirus disease-19: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2022, 16, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadanny, A.; Zilberman-Itskovich, S.; Catalogna, M.; Elman-Shina, K.; Lang, E.; Finci, S.; Polak, N.; Shorer, R.; Parag, Y.; Efrati, S. Long term outcomes of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in post COVID condition: Longitudinal follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Berkel, J.; Lalieu, R.C.; Joseph, D.; Hellemons, M.; Lansdorp, C.A. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for long COVID: A prospective registry. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellberg, A.; Hassler, A.; Boström, E.; El Gharbi, S.; Al-Ezerjawi, S.; Kowalski, J.; Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A.; Bruchfeld, J.; Ståhlberg, M.; Nygren-Bonnier, M.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for long COVID (HOT-LoCO), an interim safety report from a randomised controlled trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, T.; Gonevski, M.; Clark, C.; Baitule, S.; Sharma, K.; Magar, A.; Patel, K.; Sankar, S.; Kyrou, I.; Ali, A.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for the treatment of long COVID: Early evaluation of a highly promising intervention. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, e629–e632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zant, A.E.; Figueroa, X.A.; Paulson, C.P.; Wright, J.K. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy to treat lingering COVID-19 symptoms. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 2022, 49, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellberg, A.; Abdel-Halim, L.; Hassler, A.; El Gharbi, S.; Al-Ezerjawi, S.; Boström, E.; Sundberg, C.J.; Pernow, J.; Medson, K.; Kowalski, J.H.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen for treatment of long COVID-19 syndrome (HOT-LoCO): Protocol for a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase II clinical trial. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e061870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitman, M.; Fuchs, S.; Tyomkin, V.; Hadanny, A.; Zilberman-Itskovich, S.; Efrati, S. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on myocardial function in post-COVID-19 syndrome patients: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’hoore, L.; Germonpré, P.; Rinia, B.; Caeyers, L.; Stevens, N.; Balestra, C. Effect of normobaric and hyperbaric hyperoxia treatment on symptoms and cognitive capacities in Long COVID patients: A randomised placebo-controlled, prospective, double-blind trial. Diving Hyperb. Med. 2025, 55, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonevski, M. Rationale and analysis of the effect of hbot therapy in the recovery of long COVID patients. Georgian. Med. News 2024, 350, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmann, J.; Porubsky, C.; Okresa, L.; Klemen, H.; Mykoliuk, I.; Roj, A.; Koutp, A.; Kink, E.; Iberer, F.; Kovacs, G.; et al. Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Hyperbaric Oxygenation in Patients with Long COVID-19 Syndrome Using SF-36 Survey and VAS Score: A Clinical Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorenshtein, A.; Liba, T.; Leibovitch, L.; Stern, S.; Stern, Y. Intervention modalities for brain fog caused by long-COVID: Systematic review of the literature. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 2951–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, J.; Gao, J.; Tang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Efficacy and safety of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for long COVID: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e08386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, M.T.; Rinneberg, G.; Koch, A.; Meyringer, H.; Loew, T.H.; Kjellberg, A. Is there a rationale for hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the patients with Post COVID syndrome? A critical review. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 274, 1797–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joli, J.; Buck, P.; Zipfel, S.; Stengel, A. Post-COVID-19 fatigue: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 947973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora, F.V.; Santos, A.C.F.F.; Zamora, A.V.; Galvao, L.K.C.S.; Pimenta, N.D.S.; Salles, J.P.C.E.A.; Carneiro, V.B.; Starling, C.E.F. Hyperbaric Oxygen Treatment for Long-COVID syndrome: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence on Cognitive Decline. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 2025, 52, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrakic-Sposta, S.; Vezzoli, A.; Garetto, G.; Paganini, M.; Camporesi, E.; Giacon, T.A.; Dellanoce, C.; Agrimi, J.; Bosco, G. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Counters Oxidative Stress/Inflammation-Driven Symptoms in Long COVID-19 Patients: Preliminary Outcomes. Metabolites 2023, 13, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.Q.; Tian, Z.M.; Xue, L.B. Hyperbaric Oxygen Treatment for Long COVID: From Molecular Mechanism to Clinical Practice. Curr. Med. Sci. 2023, 43, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermakow, N.; Brodaczewska, K.; Kot, J.; Lubas, A.; Kłos, K.; Siewiera, J. Bayesian Modeling of the Impact of HBOT on the Reduction in Cytokine Storms. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarroch, E.E. The central autonomic network: Functional organization, dysfunction, and perspective. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1993, 68, 988–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarroch, E.E. Postural tachycardia syndrome: A heterogeneous and multifactorial disorder. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2012, 87, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitiello, A. Long COVID Syndrome and Role of Autonomic Nervous System. Rev. Med. Virol. 2026, 36, e70101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylikoski, J.; Lehtimäki, J.; Pääkkönen, R.; Mäkitie, A. Prevention and Treatment of Life-Threatening COVID-19 May Be Possible with Oxygen Treatment. Life 2022, 12, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Villalobos, I.; Casanova-Maldonado, I.; Lois, P.; Prieto, C.; Pizarro, C.; Lattus, J.; Osorio, G.; Palma, V. Hyperbaric Oxygen Increases Stem Cell Proliferation, Angiogenesis and Wound-Healing Ability of WJ-MSCs in Diabetic Mice. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Daugherty, W.P.; Sun, D.; Levasseur, J.E.; Altememi, N.; Hamm, R.J.; Rockswold, G.L.; Bullock, M.R. Protection of mitochondrial function and improvement in cognitive recovery in rats treated with hyperbaric oxygen following lateral fluid-percussion injury. J. Neurosurg. 2007, 106, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efrati, S.; Fishlev, G.; Bechor, Y.; Volkov, O.; Bergan, J.; Kliakhandler, K.; Kamiager, I.; Gal, N.; Friedman, M.; Ben-Jacob, E.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen induces late neuroplasticity in post stroke patients--randomized, prospective trial. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Lan, C.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Mei, Q.; Feng, H.; Wei, S.; et al. Effect of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy on Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 5501–5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelin, D.; Wirtheim, E.; Vetter, P.; Kalil, A.C.; Bruchfeld, J.; Runold, M.; Guaraldi, G.; Mussini, C.; Gudiol, C.; Pujol, M.; et al. Long-term consequences of COVID-19: Research needs. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, D.C.; Wainwright, S. Hyperbaric Oxygen Treatment of Long COVID: Review of the Evidence and Perspective. Med. Res. Arch. 2025, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collettini, A.; Zoccali, F.; Barbato, C.; Minni, A. Hyperbaric Oxygen in Otorhinolaryngology: Current Concepts in Management and Therapy. Oxygen 2024, 4, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.