Abstract

Hypertriglyceridaemia is the third most common aetiology of acute pancreatitis and a leading cause of recurrence in specialized lipid clinics. The risk of acute pancreatitis rises steeply once triglycerides exceed approximately 10 mmol/L (≈885 mg/dL). Still, clinically meaningful risk may occur at lower levels in the presence of chylomicronaemia, metabolic stress, or pregnancy. This mini-review synthesizes contemporary evidence on epidemiology, mechanistic links between triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and pancreatic injury, and the practical distinction between secondary (acquired) and genetic drivers of severe hypertriglyceridaemia. We summarize acute management strategies aimed at rapid triglyceride reduction (including insulin-based approaches and therapeutic plasma exchange in selected scenarios) and focus on long-term prevention of recurrence through lifestyle interventions, correction of secondary contributors, and triglyceride-lowering pharmacotherapy. Finally, we discuss emerging RNA-targeted therapies against apolipoprotein C-III and angiopoietin-like 3, which are reshaping prevention strategies for familial and persistent chylomicronaemia and may reduce pancreatitis burden in the highest-risk phenotypes.

1. Introduction

Hypertriglyceridaemia-associated acute pancreatitis (HTG-AP) is an increasingly recognised entity, linked to the rising prevalence of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and alcohol use. Across cohorts, HTG-AP accounts for roughly 2–10% of acute pancreatitis presentations but may be over-represented in younger patients and in recurrent disease [1,2,3]. Because triglyceride levels can fall rapidly with fasting and intravenous fluids, early sampling is essential, and chylomicronaemia should be suspected when serum appears lactescent. Clinically, the pancreatitis risk rises sharply once triglycerides exceed ~10 mmol/L (~885 mg/dL) and becomes particularly high above 20 mmol/L (~1770 mg/dL), especially in the presence of ‘second hits’ such as uncontrolled diabetes, pregnancy, alcohol, or certain medicines [4,5]. Current international pancreatitis guidance emphasizes supportive care, while triglyceride-specific interventions remain variably adopted due to limited randomized evidence [6,7]. This review summarizes risk epidemiology, mechanistic pathways, and a pragmatic approach to identifying secondary and genetic drivers of severe hypertriglyceridaemia, with a focus on preventing pancreatitis recurrence.

2. Materials and Methods

This narrative review was developed to support clinical decision-making in severe hypertriglyceridaemia and suspected HTG-AP. We searched PubMed and major society/regulatory websites (December 2010–December 2025) for English-language evidence using combinations of the terms ‘hypertriglyceridemia’, ‘chylomicronemia’, ‘familial chylomicronemia’, ‘acute pancreatitis’, ‘plasmapheresis/therapeutic plasma exchange’, ‘insulin’, ‘apolipoprotein C-III’, ‘ANGPTL3’, ‘olezarsen’, ‘volanesorsen’, and ‘plozasiran’. Priority was given to international guidelines, randomized trials, meta-analyses, and large observational cohorts; mechanistic studies were included when they clarified biological plausibility. Reference lists of eligible papers were hand-searched to identify additional key sources.

3. Epidemiology and Risk Gradient

Acute pancreatitis incidence varies widely by geography and case-mix, with contemporary global datasets highlighting substantial heterogeneity in aetiology and outcomes. Hypertriglyceridaemia is typically considered causative when triglycerides are ≥11.3 mmol/L (≥1000 mg/dL) and no alternative dominant aetiology is found, although some clinicians use a lower threshold (~10 mmol/L) when chylomicronaemia is evident [1,3]. Large population studies demonstrate a graded relationship between triglycerides and pancreatitis, with risk detectable even in the 2–10 mmol/L range in susceptible individuals and with the steepest rise at higher concentrations. In a Danish cohort, nonfasting triglycerides of 2.0–2.9 mmol/L were associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.3 (95% CI 1.3–4.0), while triglycerides ≥5.0 mmol/L were associated with an HR of 8.7 (4.9–15.5), corresponding to ~7 and 12 events per 10,000 person-years, respectively. Among hospitalised HTG-AP cohorts, recurrent pancreatitis is common, reflecting persistent or recurrent severe hypertriglyceridaemia and incomplete correction of secondary contributors [6,7].

Importantly, triglycerides may be a ‘marker and mediator’: they can reflect broader metabolic inflammation and simultaneously contribute directly to pancreatic lipotoxicity. Thus, risk assessment should integrate both the absolute triglyceride level and the clinical context (fasting status, glycaemic control, alcohol, pregnancy, renal function, and medications) [6,7].

4. Pathophysiological Links Between Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins and Pancreatic Injury

Severe hypertriglyceridaemia is usually characterized by circulating chylomicrons, with or without very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL). Chylomicrons increase plasma viscosity and may impair pancreatic microcirculation, predisposing to local ischaemia. Within the inflamed pancreas, hydrolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins by pancreatic lipase generates high local concentrations of unbound free-fatty acids, which can overwhelm albumin buffering, disrupt acinar and endothelial membranes, and amplify inflammation and microthrombosis. Mechanistic models support a central role for lipase-driven lipotoxicity in amplifying local and systemic inflammation. Clinically, the hyperchylomicronaemic state can also interfere with laboratory assays (e.g., spuriously low amylase in lipaemic serum), so diagnosis should not rely solely on enzyme levels [2].

Mechanistically, the ‘Free Fatty Acid–FFA-toxicity’ model has important therapeutic implications. Hydrolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins generates unbound FFAs that can exceed albumin binding capacity, trigger intracellular Ca2+ overload and mitochondrial dysfunction in acinar cells, injure the pancreatic microvascular endothelium, and promote capillary plugging and hypoperfusion. These events amplify local necroinflammation and systemic cytokine release, providing a rationale for rapid triglyceride lowering (to reduce further FFA generation) together with early, guideline-concordant supportive care [2,4].

5. Drivers of Severe Hypertriglyceridaemia and Pancreatitis Risk: Acquired and Genetic Contributors

Severe HTG potentially causing AP can be secondary (acquired) or primary genetic.

Secondary drivers commonly precipitate HTG-AP by pushing triglycerides above the chylomicronaemic threshold in individuals with underlying polygenic susceptibility [6]. The most frequent and clinically actionable contributors include uncontrolled diabetes (often with ketosis), excess alcohol intake, obesity and insulin resistance, diets high in refined carbohydrates and saturated fat, pregnancy (particularly the third trimester), chronic kidney disease and nephrotic syndrome, and untreated hypothyroidism [7,8].

Several medicines can also raise triglycerides or trigger pancreatitis through additional mechanisms, necessitating careful drug reconciliation [9,10].

In intensive care, propofol infusion can raise triglycerides and has been linked to pancreatitis; triglycerides should be monitored during prolonged or high-dose infusions [11,12,13].

Table 1 summarizes a pragmatic checklist of secondary drivers and typical clinical ‘red flags’. In practice, more than one secondary driver is often present, and their correction frequently yields the greatest absolute reductions in triglyceride [6,7,8].

Table 1.

Secondary drivers of severe hypertriglyceridaemia relevant to HTG-AP.

Severe hypertriglyceridaemia with chylomicronaemia can reflect either familial chylomicronaemia syndrome (FCS) or multifactorial/persistent chylomicronaemia. FCS is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by biallelic loss-of-function variants in genes required for intravascular triglyceride hydrolysis (e.g., LPL, APOC2, APOA5, GPIHBP1, LMF1). It often presents in childhood or adolescence with recurrent abdominal pain, eruptive xanthomata, lipaemia retinalis, and recurrent pancreatitis despite strict dietary fat restriction [14]. By contrast, multifactorial or persistent chylomicronaemia is far more common and results from polygenic predisposition compounded by secondary drivers; triglycerides may fluctuate widely and often respond (at least partially) to correction of acquired contributors and conventional pharmacotherapy [14].

A recent joint National Lipid Association/American Society for Preventive Cardiology consensus proposes a pragmatic umbrella term, persistent chylomicronemia (PC), defined as triglycerides ≥1000 mg/dL in more than half of measurements, and emphasises phenotype-based risk stratification. Genetic FCS remains rare (~1–10 per million), whereas multifactorial chylomicronemia is far more common (~1 in 500). The statement also highlights ‘alarm’ features (e.g., recurrent triglyceride-induced pancreatitis, childhood pancreatitis, family history of triglyceride-induced pancreatitis, or markedly reduced post-heparin LPL activity) that identify patients whose pancreatitis risk approaches that of FCS and who may benefit from expedited access to intensive triglyceride lowering (including apoC-III–targeted therapies) [15].

Because access to emerging RNA-targeted therapies is often restricted to genetically confirmed or strongly suspected FCS, early differentiation is clinically important. Simple clinical clues include early onset, very low LDL-C/apoB, minimal response to fibrates/omega-3, and recurrent pancreatitis at comparatively stable triglyceride levels. Scoring systems (e.g., the FCS score) can support triage for genetic testing [16]. These practical differentiating features are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Practical features distinguishing FCS from multifactorial/persistent chylomicronaemia in the setting of severe hypertriglyceridaemia.

6. Acute Management of HTG-AP

Initial management of HTG-AP follows general acute pancreatitis principles: early risk stratification, aggressive but judicious intravenous fluids, prompt analgesia, early enteral nutrition when feasible, and management of complications (organ failure, infection, necrosis) according to established guidelines. Triglyceride-specific treatment is typically considered when triglycerides are markedly elevated (commonly ≥11.3 mmol/L) and/or when chylomicronaemia is suspected to be contributory. In patients with concurrent diabetic decompensation, intravenous insulin addresses both hyperglycaemia and triglyceride-rich lipoprotein clearance through the upregulation of lipoprotein lipase [1,2,3,4,5,6].

Evidence supporting therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) is mixed. In a randomized trial comparing TPE with intravenous insulin, TPE produced a numerically faster decline in triglycerides but did not improve clinical outcomes such as organ failure or intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay [17]. In a large contemporary observational analysis, early plasmapheresis was not associated with improved in-hospital outcomes after adjustment for baseline disease severity [18]. A meta-analysis of 15 studies (1 randomized, 2 prospective case-control, and 12 retrospective cohort studies) involving 909 patients with HTG-AP concluded that insulin-treatment was less effective than TPE in reducing triglyceride levels (Δ-TG) at 24 h (WMD, −666; 95%CI, −1130 to −201; p = 0.005), 48 h (WMD, −672; 95%CI, −1233 to −111), and by day 7 (WMD, −385; 95%CI, −711 to −60; p = 0.02), even if insulin-treatment was associated with fewer adverse events and lower costs [19]. Accordingly, current apheresis guidance reserves TPE for carefully selected, high-risk patients (e.g., refractory or extremely high triglycerides with evolving organ dysfunction), ideally within a multidisciplinary framework [20].

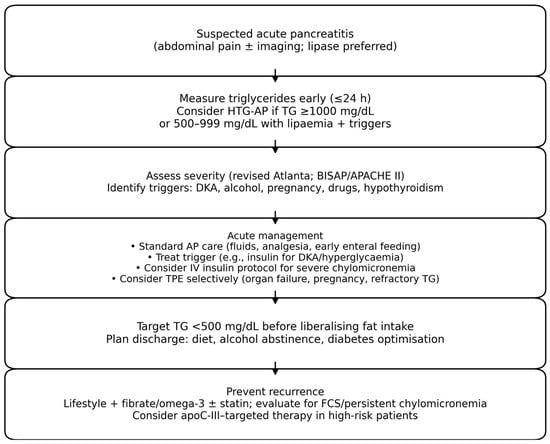

Key practical points include: (i) measure triglycerides early (ideally at presentation, before prolonged fasting); (ii) avoid intravenous lipid emulsions unless clinically necessary; (iii) consider stopping triglyceride-raising medications; and (iv) aim for rapid reduction to <5.6 mmol/L (<500 mg/dL) in high-risk scenarios, recognizing that targets and timelines vary across centers [6,7,8,19]. A pragmatic diagnostic and management pathway is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Pragmatic diagnostic and management algorithm for suspected hypertriglyceridaemia-associated acute pancreatitis (HTG-AP). Abbreviations: TG, triglycerides; TPE, therapeutic plasma exchange; FCS, familial chylomicronaemia syndrome.

7. Long-Term Prevention of Recurrence

Recurrent pancreatitis after an index HTG-AP episode is common and clinically meaningful, with prospective and retrospective cohorts reporting substantial readmission rates, particularly when post-discharge triglycerides remain elevated. Persistent hypertriglyceridaemia during follow-up, ongoing metabolic triggers (e.g., uncontrolled diabetes, obesity, alcohol exposure), and a higher comorbidity burden have been identified as key predictors of recurrence [21]. These data provide the clinical rationale for ongoing interventional trials, including the multicentre REDUCE randomised controlled trial protocol, which will test whether intensive triglyceride targets (<150 mg/dL) reduce recurrent HTG-AP compared with usual care (<500 mg/dL) [22].

Preventing recurrence requires a dual strategy: (i) sustained suppression of triglycerides below the chylomicronaemic range; and (ii) removal of precipitating ‘second hits’. After an HTG-AP episode, most experts target triglycerides <5.6 mmol/L (<500 mg/dL), and ideally <2.3 mmol/L (<200 mg/dL) when feasible, recognising that the achievable target depends on the underlying phenotype [6,7,8].

Lifestyle measures remain foundational: strict limitation of dietary fat (in particular in FCS patients, <10–15% of daily calories, typically ≤15–20 g/day of long-chain fat, to minimise chylomicron formation, eventually using medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) as calorie source), fat spreading evenly across meals/snacks and avoid “fat boluses” (single high-fat meals) to reduce acute TG spikes, complete avoidance of alcohol, reduction of refined carbohydrates (prioritising complex, high-fibre carbohydrates), avoidance of high-fructose foods/drinks (soft drinks/juices), increase of aerobic physical activity, weight loss, and optimisation of glycaemic control. In multifactorial hypertriglyceridemias, reducing simple sugars and achieving modest weight loss can lead to large reductions in triglyceride [23].

7.1. Conventional Pharmacotherapy

The most extensively studied lipid-lowering drugs do not produce a marked reduction in triglyceride levels, largely because patients with very high triglyceride levels are usually excluded from clinical trials evaluating these agents [24]. Fibrates are commonly used for severe hypertriglyceridaemia and can reduce triglycerides by 30–50% in multifactorial phenotypes [25], though the benefit could be limited in FCS [26]. High-dose prescription omega-3 fatty acids (e.g., icosapent ethyl or eicosapentaenoic/doxosahexaenoic fatty acids formulations, 4 g/day) can add a further 20–30% reduction [27]. Statins are not primary triglyceride-lowering agents but are essential for cardiovascular disease risk reduction in appropriate patients and may modestly lower triglycerides [28]; they are not associated with an increased risk of pancreatitis in meta-analyses of 16 randomized trials with 113.800 patients and may show a non-significant trend toward lower risk [29]. Ezetimibe can also mildly contribute to the plasma TG reduction, as well as bempedoic acid and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors [24].

7.2. Emerging and Recently Approved Therapies Targeting ApoC-III and ANGPTL3

Apolipoprotein C-III (apoC-III) is a key inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase and hepatic clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Well-known TG-lowering drugs, such as prescription omega-3 fatty acids [30] and fibrates, significantly reduce TG plasma levels [31]. RNA-targeted therapies that suppress apoC-III can markedly lower triglycerides and are now clinically available for FCS in selected jurisdictions. In the APPROACH trial, the antisense oligonucleotide volanesorsen reduced triglycerides by 77% at 3 months, and 77% of participants achieved triglycerides < 750 mg/dL, but intensive platelet monitoring is required because of thrombocytopenia risk [32]. Newer agents aim to improve the efficacy–tolerability balance: in a phase 2b trial, olezarsen lowered triglycerides by 43.5% at 6 months (vs. 6.2% with placebo), and pancreatitis episodes were less frequent (11 with placebo vs. 1 in each active-dose group) [33]. In the PALISADE trial, the small interfering RNA plozasiran reduced triglycerides by 80.2% at 10 months (vs. 18.9% with placebo) and was associated with lower pancreatitis incidence (odds ratio 0.17) [34]. The regulatory status of these agents continues to evolve across regions.

ANGPTL3 inhibition represents an alternative pathway by enhancing lipoprotein lipase activity. In a phase 2 trial, evinacumab reduced triglycerides in some severe hypertriglyceridaemia phenotypes, though effects were attenuated in classic FCS. Further outcome-focused studies are warranted to define which genetic and clinical subgroups derive the greatest pancreatitis risk reduction [35].

Table 3 provides a concise overview of emerging and recently approved triglyceride-lowering therapies, including their mechanisms of action and current regulatory status.

Table 3.

Novel triglyceride-lowering therapies relevant to HTG-AP: mechanism of action, approval status, and key evidence.

8. A Special Situation: The Pregnancy-Associated Severe Hypertriglyceridaemias

Pregnancy-associated severe hypertriglyceridaemia warrants proactive monitoring and multidisciplinary management, particularly in women with prior HTG-AP or suspected FCS [43]. Similarly, diabetic ketoacidosis with severe hypertriglyceridaemia can present with abdominal pain and pancreatitis; insulin remains central to management [44]. In a retrospective series of 116 pregnancies among 49 women with chylomicronemia (20 FCS, 29 MCS), at least one acute pancreatitis episode occurred in 42% of women with FCS versus 10% with MCS, and pancreatitis complicated 17% versus 5% of pregnancies; prematurity was common (56% in FCS vs. 19% in MCS), whereas miscarriage and fetal growth restriction rates were similar between groups [45]. Case-based evidence also supports structured multidisciplinary pathways: a 2025 report and systematic review of 23 pregnancies treated with regular apheresis found a mean triglyceride reduction of 45.1% per session (highest with centrifugation–filtration plasmapheresis: 68.3 ± 7.2%), no maternal deaths, but pancreatitis still occurred in 17.4% (mean triglycerides at onset 45.20 ± 4.65 mmol/L) [46].

9. Discussion

Hypertriglyceridaemia-related pancreatitis is a relatively rare but dramatic clinical complication of severe triglyceride-rich lipoprotein dysmetabolism and, importantly, it is often preventable [47]. In particular, severe forms of primitive massive hypertriglyceridemia should be screened as well as secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia [7].

After an index episode, recurrence can also frequently be avoided through phenotype-driven detection and sustained management of severe hypertriglyceridaemia, together with systematic removal of precipitating ‘second hits’ [48,49] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hypertriglyceridemia-related pancreatitis: main points.

In clinical practice, this work-up should start with a structured search for primitive massive hypertriglyceridaemia—most importantly familial chylomicronaemia syndrome (FCS) due to biallelic variants affecting the LPL pathway—because these patients carry a high lifetime recurrence risk and may benefit from early specialist referral, genetic confirmation, and access to targeted RNA-based therapies [15,50]. In this context, scientific societies are validating clinical scores to more easily and early identify subjects potentially affected by FCS [51,52,53,54].

Conversely, most cases reflect multifactorial or persistent chylomicronaemia, where genetic susceptibility is amplified by ‘second hits’. The most frequent triggers include uncontrolled diabetes or insulin deficiency, excess alcohol intake, obesity and metabolic dysfunction, and pregnancy-related triglyceride surges—particularly in the third trimester—often requiring multidisciplinary management [6,7,8]. Other secondary drivers that should be actively screened include hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, and chronic kidney disease [55], and iatrogenic lipid-raising exposures such as oral oestrogens, retinoids, glucocorticoids, atypical antipsychotics, HIV protease inhibitors, and continuous propofol infusion in critically ill patients [56,57]. Importantly, documenting and addressing these reversible contributors is central to long-term prevention: the same patient may transition between moderate hypertriglyceridaemia and extreme levels depending on metabolic control, medication changes, and dietary adherence, underscoring the need for repeated assessment over time rather than a single ‘snapshot’ measurement.

Across guideline statements and technical reviews, the key practical message is to treat both the ‘fuel’ (triglyceride-rich lipoproteins) and the ‘second hits’ that precipitate attacks [7,48]. Early supportive care remains central, while triglyceride-lowering interventions are adjunctive and should be individualized to severity, comorbidity, and local expertise [54]. Secondary contributors (alcohol, uncontrolled diabetes, obesity, pregnancy, renal dysfunction) [55] and triglyceride-raising medications should be systematically sought and corrected, and drug causality considered when the temporal relationship is compelling [56,57].

For acute triglyceride lowering in HTG-AP, the evidence base remains heterogeneous. In a small randomized comparison, therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) achieved a faster early reduction in triglycerides than insulin infusion, but did not demonstrate consistent superiority for clinically meaningful outcomes [52]; similarly, observational cohorts and meta-analyses yield mixed results and are prone to confounding by indication [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. More recent retrospective comparisons and outcome analyses suggest broadly comparable clinical outcomes between extracorporeal approaches, with rapid biochemical improvements but an uncertain effect on organ failure or mortality, reinforcing a selective, individualized use in severe or refractory presentations [66]. Therefore, most contemporary guidance supports insulin-based protocols as first-line triglyceride-lowering therapy, reserving TPE or hemofiltration for severe disease with organ failure, refractory or extreme hypertriglyceridaemia, or when insulin is contraindicated, preferably within experienced centres [20]. New studies are trying to identify new (probably) most effective TPE protocols to improve prognosis in HTG-AP patients [67]. For long-term prevention, triglyceride-modifying outcome trials and emerging apoC-III/ANGPTL3–targeted approaches help frame the achievable magnitude of triglyceride lowering and the residual pancreatitis risk, but HTG-AP–specific prospective outcome data are still limited [36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. On the other hand, it remains unclear whether optimizing triglyceride levels per se reduces the risk of recurrent pancreatitis compared with a more conservative approach. This question is being addressed in an ongoing clinical trial enrolling 256 Chinese participants with hypertriglyceridemia-associated acute pancreatitis, who are randomized to either intensive triglyceride-lowering therapy (targeting TG <150 mg/dL) or usual care (targeting TG < 500 mg/dL) [22]. Finally, validated acute pancreatitis severity scores and broad reviews remain useful for bedside prognostication and for aligning HTG-AP management with general acute pancreatitis pathways [68].

Despite substantial advances in phenotyping and TG-lowering options, major evidence gaps persist: most interventional studies in HTG-AP remain small, heterogeneous, and focused on biochemical endpoints rather than patient-centered outcomes (persistent organ failure, necrosis, mortality), limiting confidence in the incremental value of strategies such as TPE over intensive medical therapy. Moreover, clinically relevant thresholds and definitions (e.g., “HTG-AP” attribution, “persistent chylomicronaemia”) are not yet fully harmonised across guidelines and studies, complicating risk stratification and cross-cohort comparisons. Finally, while apoC-III–targeted agents provide the strongest pancreatitis-prevention signal in FCS, high-quality data are still needed to define generalizability, optimal sequencing, and cost-effective implementation in broader multifactorial chylomicronaemia populations.

10. Conclusions

HTG-AP is a clinically important and often preventable cause of acute pancreatitis and recurrence. Risk is driven by chylomicronaemia and modulated by secondary triggers; systematic evaluation and correction of acquired contributors are therefore essential. Distinguishing FCS from multifactorial/persistent chylomicronaemia guides genetic testing, specialist referral, and access to emerging therapies. While supportive care remains the cornerstone of acute management, selected patients may benefit from rapid triglyceride-lowering using insulin-based regimens, with TPE reserved for severe or refractory cases. RNA-targeted therapies against apoC-III and ANGPTL3 pathway modulation represent a step change for the highest-risk phenotypes and may substantially reduce pancreatitis burden when integrated into comprehensive prevention programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, F.F. and A.F.G.C., writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, F.F. and A.F.G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The graphical abstract was created using Google Collaboratory (Google Notebook).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tenner, S.; Vege, S.S.; Sheth, S.G.; Sauer, B.; Yang, A.; Conwell, D.L.; Yadlapati, R.H.; Gardner, T.B. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines: Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 119, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pretis, N.; Amodio, A.; Frulloni, L. Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical management. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2018, 6, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.B.; Langsted, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Nonfasting Mild-to-Moderate Hypertriglyceridemia and Risk of Acute Pancreatitis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1834–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.L.; McNabb-Baltar, J. Hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2020, 20, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindkvist, B.; Appelros, S.; Regnér, S.; Manjer, J. A prospective cohort study on risk of acute pancreatitis related to serum triglycerides, cholesterol and fasting glucose. Pancreatology 2012, 12, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxbaum, J.L.; Gardner, T.B.; Chari, S.T. Updates from the 2025 IAP Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. Pancreas 2026, 55, e147–e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Párniczky, A.; Mikó, A.; Uc, A.; Singh, A.N.; Elhence, A.; Saluja, A.; Masamune, A.; Abu Dayyeh, B.K.; Davidson, B.; Wilcox, C.M.; et al. IAP/APA/EPC/IPC/JPS Working Group. International Association of Pancreatology Revised Guidelines on Acute Pancreatitis 2025: Supported and Endorsed by the American Pancreatic Association, European Pancreatic Club, Indian Pancreas Club, and Japan Pancreas Society. Pancreatology 2025, 25, 770–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, S.S.; Morris, P.B.; Agarwala, A.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Birtcher, K.K.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Ladden-Stirling, A.B.; Miller, M.; Orringer, C.E.; Stone, N.J. 2021 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the management of ASCVD risk reduction in patients with persistent hypertriglyceridemia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 960–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnon, A.L.; Lavoie, A.; Frigon, M.P.; Michaud-Herbst, A.; Tremblay, K. A Drug-Induced Acute Pancreatitis Retrospective Study. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 2020, 1516493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goraya, M.H.N.; Abbasi, E.U.H.; Amin, M.K.; Inayat, F.; Ashraf, M.J.; Qayyum, M.; Hussain, N.; Nawaz, G.; Zaman, M.A.; Malik, A. Acute pancreatitis secondary to tamoxifen-associated hypertriglyceridemia: A clinical update. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 29, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.W.; Lau, A.K.; Tanios, M.A. Propofol-Associated Hypertriglyceridemia and Pancreatitis in the Intensive Care Unit: An Analysis of Frequency and Risk Factors. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2005, 25, 1348–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heybati, K.; Deng, J.; Xie, G.; Poudel, K.; Zhou, F.; Rizwan, Z.; Brown, C.S.; Acker, C.T.; Gajic, O.; Yadav, H. Propofol, Hypertriglycerridemia, and Acute Pancreatitis: A Multicenter Epidemiologic Analysis. Ann. Am. Thor. Soc. 2025, 22, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdul Razzak, I.; Korchemny, N.; Smoot, D.; Jose, A.; Jones, A.; Price, L.L.; Jaber, B.L.; Moraco, A.H. Parameters Predictive of Propofol-Associated Acute Pancreatitis in Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Intens. Care Med. 2025, 40, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, C.; Ciciola, P.; D’Errico, G.; Di Taranto, M.D.; Fortunato, G.; Gross, C.; Garn, J.; Iannuzzo, G.; Di Minno, M.; Calcaterra, I. Genetic Assessment and Clinical Correlates in Severe Hypertriglyceridemia: A Systematic Review. Genes 2025, 16, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadatagah, S.; Larouche, M.; Naderian, M.; Nambi, V.; Brisson, D.; Kullo, I.J.; Duell, P.B.; Michos, E.D.; Shapiro, M.D.; Watts, G.F.; et al. Recognition and management of persistent chylomicronemia: A joint expert clinical consensus by the National Lipid Association and the American Society for Preventive Cardiology. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2025, 19, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulin, P.; Dufour, R.; Averna, M.; Arca, M.; Cefalù, A.B.; Noto, D.; D’Erasmo, L.; Di Costanzo, A.; Marçais, C.; Walther, L.A.A.-S.; et al. Identification and diagnosis of patients with familial chylomicronaemia syndrome (FCS): Expert panel recommendations and proposal of an “FCS score”. Atherosclerosis 2018, 275, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubensek, J.; Andonova, M.; Jerman, A.; Persic, V.; Vajdic-Trampuz, B.; Zupunski-Cede, A.; Sever, N.; Plut, S. Comparable Triglyceride Reduction with Plasma Exchange and Insulin in Acute Pancreatitis—A Randomized Trial. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 870067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Huang, W.; Wu, D.; Hong, D.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Qin, K.; Guo, F.; et al. Early Plasmapheresis Among Patients with Hypertriglyceridemia-Associated Acute Pancreatitis. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2320802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Cai, W.; Yang, X.; Camilleri, G.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Mukherjee, R.; Huang, W.; Sutton, R. Insulin or blood purification treatment for hypertriglyceridaemia-associated acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreatology 2022, 22, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly-Smith, L.; Alquist, C.R.; Aqui, N.A.; Hofmann, J.C.; Klingel, R.; Onwuemene, O.A.; Patriquin, C.J.; Pham, H.P.; Sanchez, A.P.; Schneiderman, J.; et al. Guidelines on the Use of Therapeutic Apheresis in Clinical Practice—Evidence-Based Approach from the Writing Committee of the American Society for Apheresis: The Ninth Special Issue. J. Clin. Apher. 2023, 38, 77–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Guan, L.; Li, X.; Xu, X.; Zou, Y.; He, C.; Hu, Y.; Wan, J.; Huang, X.; Lei, Y.; et al. Recurrence for patients with first episode of hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis: A prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2023, 17, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, G.; Deng, L.; Sheng, J.; Zhu, C.; Sheng, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, D.; et al. Prevention of recurrence of hypertriglyceridemia-associated acute pancreatitis by controlling triglyceride levels: Protocol for a multicentre, randomised controlled trial (REDUCE). BMJ Open 2025, 15, e093011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufs, U.; Parhofer, K.G.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Hegele, R.A. Clinical review on triglycerides. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 99–109c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raschi, E.; Casula, M.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Corsini, A.; Borghi, C.; Catapano, A. Beyond statins: New pharmacological targets to decrease LDL-cholesterol and cardiovascular events. Pharmacol. Therap 2023, 250, 108507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirillo, A.; Zambon, A.; Catapano, A.L. Fibrates: Do They Still Have a Role in Therapy in 2025? Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2025, 28, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, N.; Shen, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, B.E.; Li, X. Association Between Omega-3 Fatty Acid Intake and Dyslipidemia: A Continuous Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Am. Heart Ass. 2023, 12, e029512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, R.; Viljoen, A.; Wierzbicki, A.S. Pharmacological treatment options for severe hypertriglyceridemia and familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 11, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk: The Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiss, D.; Tikkanen, M.J.; Welsh, P.; Ford, I.; Lovato, L.C.; Elam, M.B.; LaRosa, J.C.; DeMicco, D.A.; Colhoun, H.M.; Goldenberg, I.; et al. Lipid-Modifying Therapies and Risk of Pancreatitis. JAMA 2012, 308, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahebkar, A.; Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Pirro, M.; Banach, M.; Sirtori, C.R.; Ruscica, M.; Reiner, Ž. Effect of statin therapy on plasma apolipoprotein CIII concentrations: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2018, 12, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebkar, A.; Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Katsiki, N.; Reiner, Ž.; Banach, M.; Pirro, M.; Atkin, S.L. Effect of fenofibrate on plasma apolipoprotein C-III levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. BMJ Open 2019, 8, e021508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witztum, J.L.; Gaudet, D.; Freedman, S.D.; Alexander, V.J.; Digenio, A.; Williams, K.R.; Yang, Q.; Hughes, S.G.; Geary, R.S.; Arca, M.; et al. Volanesorsen and Triglyceride Levels in Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroes, E.S.; Alexander, V.J.; Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Hegele, R.A.; Arca, M.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Soran, H.; Prohaska, T.A.; Xia, S.; Ginsberg, H.N.; et al. Balance Investigators. Olezarsen, Acute Pancreatitis, and Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1781–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, G.F.; Rosenson, R.S.; Hegele, R.A.; Goldberg, I.J.; Gallo, A.; Mertens, A.; Baass, A.; Zhou, R.; Muhsin, M.; Hellawell, J.; et al. Plozasiran for Managing Persistent Chylomicronemia and Pancreatitis Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenson, R.S.; Gaudet, D.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Baum, S.J.; Bergeron, J.; Kershaw, E.E.; Moriarty, P.M.; Rubba, P.; Whitcomb, D.C.; Banerjee, P.; et al. Evinacumab in severe hypertriglyceridemia with or without lipoprotein lipase pathway mutations: A phase 2 randomized trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogacci, F.; Norata, G.D.; Toth, P.P.; Arca, M.; Cicero, A.F.G. Efficacy and Safety of Volanesorsen (ISIS 304801): The Evidence from Phase 2 and 3 Clinical Trials. Curr. Atheroscl. Rep. 2020, 22, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas, S.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Alexander, V.J.; Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Dibble, A.; Li, L.; Witztum, J.L.; Hegele, R.A. Differential effects of volanesorsen on apoC-III, triglycerides, and pancreatitis in familial chylomicronemia syndrome diagnosed by genetic or nongenetic criteria. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2025, 19, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. TRYNGOLZA (Olezarsen) Injection, for Subcutaneous Use: Prescribing Information. 2024. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/218614s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. Tryngolza (Olezarsen): EPAR—Medicine Overview. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/tryngolza (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Sydhom, P.; Al-Quraishi, B.; Gohar, A.; El-Shawaf, M.; Shehata, N.; Ataya, M.; Sydhom, M.; Awwad, N.; Motawade, H.; Naji, N.; et al. The Efficacy and Safety of Plozasiran on Lipid Profile in Dyslipidemic Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2025. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, P.M.; Nardelli, N.; Schreier, L. Inhibition of angiopoietin-like protein 3 as a target for managing hypertriglyceridemia. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diab. Obes. 2025. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmark, B.A.; Marston, N.A.; Bramson, C.R.; Curto, M.; Ramos, V.; Jevne, A.; Kuder, J.F.; Park, J.G.; Murphy, S.A.; Verma, S.; et al. Effect of Vupanorsen on Non–High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Statin-Treated Patients with Elevated Cholesterol: TRANSLATE-TIMI 70. Circulation 2022, 145, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, A.; Preda, S.D.; Mota, M.; Iliescu, D.G.; Zorila, L.G.; Comanescu, A.C.; Mitrea, A.; Clenciu, D.; Mota, E.; Vladu, I.M. Dyslipidemia in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Molecular Alterations and Clinical Implications. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frise, C.J.; Ashcroft, A.; Jones, B.A.; Mackillop, L. Pregnancy and ketoacidosis: Is pancreatitis a missing link? Obstet. Med. 2016, 9, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larouche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Brisson, D.; Laflamme, N.; Audet-Verreault, N.; Sharon, C.; Charrière, S.; Rama, M.; Collin-Chavagnac, D.; Moulin, P.; et al. Course of Pregnancies and Occurrence of Acute Pancreatitis in Women with Chylomicronemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2026, 111, e455–e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Xia, P.; Yue, C.; Xia, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, L.; Song, Y.; Gao, J.; Li, N.; Li, X.; et al. A multidisciplinary management model for severe gestational hypertriglyceridemia: Using plasmapheresis to prevent pancreatitis in pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2025, 25, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trikudanathan, G.; Yazici, C.; Phillips, A.E.; Forsmark, C.E. Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2024, 167, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, N.S.R.; Nelson, A.J.; Brett, T.; Hespe, C.M.; Watts, G.F.; Nicholls, S.J. Hypertriglyceridaemia: A practical approach for primary care. Austr. J. Gen. Pract. 2025, 54, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegele, R.A. Approach to the Adult Patient with Chylomicronemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, dgaf701, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, F.; Hegele, R.A.; Garg, A.; Patni, N.; Gaudet, D.; Williams, L.; Khan, M.; Li, Q.; Ahmad, Z. Familial chylomicronemia syndrome: An expert clinical review from the National Lipid Association. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2025, 19, 382–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegele, R.A.; Ahmad, Z.; Ashraf, A.; Baldassarra, A.; Brown, A.S.; Chait, A.; Freedman, S.D.; Kohn, B.; Miller, M.; Patni, N.; et al. Development and validation of clinical criteria to identify familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS) in North America. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2025, 19, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.S.; Moulin, P.; Dibble, A.; Alexander, V.J.; Li, L.; Gaudet, D.; Witztum, J.L.; Tsimikas, S.; Hegele, R.A. Brief communication: Strong concordance of the North American Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome Score with a positive genetic diagnosis in patients from the Balance study. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2025, 19, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Lipid Association. North American Familial Chylomicronemia Calculator (NAFCS Scoring Tool). Available online: https://www.lipid.org (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Bashir, B.; Kwok, S.; Wierzbicki, A.S.; Jones, A.; Dawson, C.; Downie, P.; Jenkinson, F.; Delaney, H.; Mansfield, M.; Datta, D.; et al. Validation of the familial chylomicronaemia syndrome (FCS) score in an ethnically diverse cohort from UK FCS registry: Implications for diagnosis and differentiation from multifactorial chylomicronaemia syndrome (MCS). Atherosclerosis 2024, 391, 117476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindato, E.M. Acute Pancreatitis: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e99233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, D.; Kanji, S.; Yazdi, F.; Barbeau, P.; Rice, D.; Beck, A.; Butler, C.; Esmaeilisaraji, L.; Skidmore, B.; Moher, D.; et al. Drug induced pancreatitis: A systematic review of case reports to determine potential drug associations. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, J.; Marino, D.; Badalov, N.; Vugelman, M.; Tenner, S. Drug-Induced Acute Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Classification (Revised). Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, e00621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Cao, L.; De-Madaria, E.; Capurso, G.; Stoppe, C.; Wu, D.; Huang, W.; Chen, Y.; et al. Triglyceride-lowering therapies in hypertriglyceridemia-associated acute pancreatitis in China: A multicentre prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.; Horibe, M.; Sanui, M.; Sasaki, M.; Sugiyama, D.; Kato, S.; Yamashita, T.; Goto, T.; Iwasaki, E.; Shirai, K.; et al. Plasmapheresis therapy has no triglyceride-lowering effect in patients with hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis. Intensiv. Care Med. 2017, 43, 949–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.H.; Yu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Xia, L.; Liu, P.; Zeng, H.; Zhu, Y.; Lv, N.H. Emergent Triglyceride-lowering Therapy with Early High-volume Hemofiltration Against Low–Molecular-Weight Heparin Combined with Insulin in Hypertriglyceridemic Pancreatitis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 50, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Peng, J.M.; Zhu, H.D.; Zhang, H.M.; Lu, B.; Lii, Y.; Qian, J.M.; Yu, X.Z.; Yang, H.; Wu, D. Continuous intravenous infusion of insulin and heparin vs plasma exchange in hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis. J. Dig. Dis. 2018, 19, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araz, F.; Bakiner, O.S.; Bagir, G.S.; Soydas, B.; Ozer, B.; Kozanoglu, I. Continuous insulin therapy versus apheresis in patients with hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 34, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dichtwald, S.; Meyer, A.; Zohar, E.; Ifrach, N.; Rotlevi, G.; Fredman, B. Hypertriglyceridemia Induced Pancreatitis: Plasmapheresis or conservative management? J. Intensiv. Care Med. 2022, 37, 1174–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C.B.; Leveno, M.; Quinn, A.M.; Burner, J. Effect of TPE vs medical management on patient outcomes in the setting of hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis with severely elevated triglycerides. J. Clin. Apher. 2021, 36, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Yu, S.; Wu, X.; Huang, L.; Huang, S.; Huang, Y.; Ding, J.; Li, D. Clinical analysis of the therapeutic effect of plasma exchange on hypertriglyceridemic acute pancreatitis: A retrospective study. Transfusion 2022, 62, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mederos, M.A.; Reber, H.A.; Girgis, M.D. Acute Pancreatitis. JAMA 2021, 325, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, T.; Li, C.; Long, Y.; Zou, X.; Dong, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, Z.; et al. Effect of plasmapheresis versus standard medical treatment in patients with hypertriglyceridemia-associated acute pancreatitis complicated by early organ failure (PERFORM-R): Study design and rationale of a multicenter, pragmatic, registry-based randomized controlled trial. Pancreatology 2025, 25, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.U.; Johannes, R.S.; Sun, X.; Tabak, Y.; Conwell, D.L.; Banks, P.A. The early prediction of mortality in acute pancreatitis: A large population-based study. Gut 2008, 57, 1698–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.