Abstract

Background: Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIC (MPS IIIC) is a rare lysosomal storage disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the HGSNAT gene. Data from large patient cohorts remain scarce, particularly in Latin America. Methods: We retrospectively analyzed clinical, biochemical, and genetic data from patients diagnosed with MPS IIIC through the MPS Brazil Network. Diagnosis was based on reduced activity of acetyl-CoA:α-glucosaminide N-acetyltransferase (HGSNAT), elevated urinary glycosaminoglycans (uGAGs), and/or molecular genetics tests. Results: A total of 101 patients were confirmed with MPS IIIC, representing one of the largest cohorts worldwide. Females accounted for 60% of cases. The mean age at symptom onset was 5.4 ± 3.9 years, while the mean age at diagnosis was 11.7 ± 6.9 years, reflecting a 6-year diagnostic delay. Most patients initially presented with developmental delay (82%) and facial dysmorphism (80%), whereas behavioral manifestations were less frequently identified (25%), suggesting a milder phenotype than previously reported. Genetic information was available for 28% of patients, showing recurrent alleles (c.372-2A>G, c.252dupT) and several novel mutations, which expand the mutational spectrum of the disease. Genotype–phenotype similarities with Portuguese, Italian, and Chinese cases suggest shared ancestry contributions. Regional differences included earlier diagnoses in the North of Brazil and high consanguinity rates in the Northeast region. Conclusions: This study describes the largest Brazilian cohort of MPS IIIC, documenting novel variants and regional heterogeneity. Findings highlight diagnostic delays, ancestry influences, and the urgent need for disease-modifying therapies.

1. Introduction

Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) are a group of lysosomal storage disorders primarily caused by deficiencies in enzymes responsible for the degradation of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), formerly known as mucopolysaccharides [1]. The MPS are classified based on the presence of a specific enzyme deficiency underlying each disorder. In this work, we focus on Mucopolysaccharidosis type III C (MPS IIIC), a subtype of Mucopolysaccharidosis III (MPS III), or Sanfilippo Syndrome, characterized by impaired degradation of heparan sulphate [2].

Mutations in distinct genes lead to four subtypes of MPS III: MPS IIIA, caused by mutations in the SGSH gene, which encodes the enzyme N-sulfoglucosamine sulfohydrolase (EC 3.10.1.1; OMIM #252900); MPS IIIB, caused by mutations in the NAGLU gene, which encodes the enzyme N-alpha-acetylglucosaminidase (EC 3.2.1.50; OMIM #252920); MPS IIIC, caused by mutations in the HGSNAT gene, which encodes the enzyme heparan acetyl-CoA:alpha-glucosaminide N-acetyltransferase (EC 2.3.1.78; OMIM #252930); and MPS IIID, caused by mutations in the GNS gene, which encodes the enzyme N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfatase (EC 3.1.6.14; OMIM #252940) [3].

All subtypes of MPS III present with a similar clinical course. During the first six years of life, the predominant manifestations include delayed neuropsychomotor development and behavioral disturbances, often leading to misdiagnoses such as Autism Spectrum Disorder [4]. Between six and ten years of age, patients typically experience marked cognitive decline accompanied by progressive behavioral worsening [5]. After the age of ten, behavioral problems tend to decrease as severe neurodegeneration becomes established, ultimately leading to premature death, usually in the third decade of life [6].

Therapeutic management of MPS IIIC remains a major challenge in clinical practice. Approaches such as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using the native enzyme have shown limited or no success, and enzyme replacement therapy has likewise failed to achieve meaningful clinical benefits [7]. Despite these limitations, significant efforts have been directed toward developing effective alternatives for affected patients. Promising advances have been reported in the use of small molecules, including substrate reduction therapies [8,9], pharmacological chaperones to correct enzyme misfolding [10], anti-inflammatory strategies [11], inhibitors of protein aggregation to mitigate neurological damage (Monaco et al., 2020), and agents targeting oxidative stress [12]. Nevertheless, a major hope in the therapeutic landscape of MPS IIIC has emerged from gene therapy, which currently represents the most promising avenue for a disease-modifying treatment [7].

As information on MPS IIIC is scarce, this study provides a unique opportunity to advance the understanding of this pathology, particularly given the relatively large sample size identified in Brazil. Accordingly, our objective was to conduct a comprehensive survey of diagnostic data for MPS IIIC from 1983 to 2025, supported by the MPS Brazil Network. The MPS Brazil Network serves as a major reference center for the diagnosis of mucopolysaccharidoses in Brazil, offering biochemical analyses of enzymes and biomarkers by traditional and innovative methods such as tandem mass spectrometry [13]. Additional services include molecular analyses to identify pathogenic variants, as well as guidance in referring patients to specialized centers close to their home [14]. This paper reflects the extensive support our center has provided to physicians and patients throughout Brazil and Latin America for over four decades for the identification of MPS IIIC cases.

2. Methods

2.1. Retrospective Study

A retrospective study was conducted on patients diagnosed with MPS IIIC who were born between 1983 and 2025 and diagnosed by the MPS Brazil Network, operating at Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA) and at Casa dos Raros (Porto Alegre, Brazil, Rio Grande do Sul). To be included in the study, patients were required to demonstrate biochemical evidence of HGSNAT-deficient activity, increased urinary glycosaminoglycans (uGAGs) with predominance of heparan sulfate, and/or mutational analysis confirming pathogenic variants in the HGSNAT gene. HGSNAT enzyme activity was assessed in leukocytes using a fluorometric assay with a specific substrate, as previously reported [15] or in dried blood spot on filter paper, as previously described [13]. Molecular genetics analysis of the HGSNAT gene was performed on DNA extracted from peripheral blood using next-generation sequencing on the Ion Torrent S5 platform with a pre-validated NGS panel [14]. Patients’ medical records were reviewed for biochemical findings, medical history, clinical manifestations, and assessments. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (GPPG: 03-066). Written informed consent was obtained from a parent in the case of minors or patients with cognitive impairment, or directly from patients aged 18 years or older, authorizing also the use of images.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Results are presented as descriptive data. Correlations between two variables were assessed using Pearson’s correlation test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

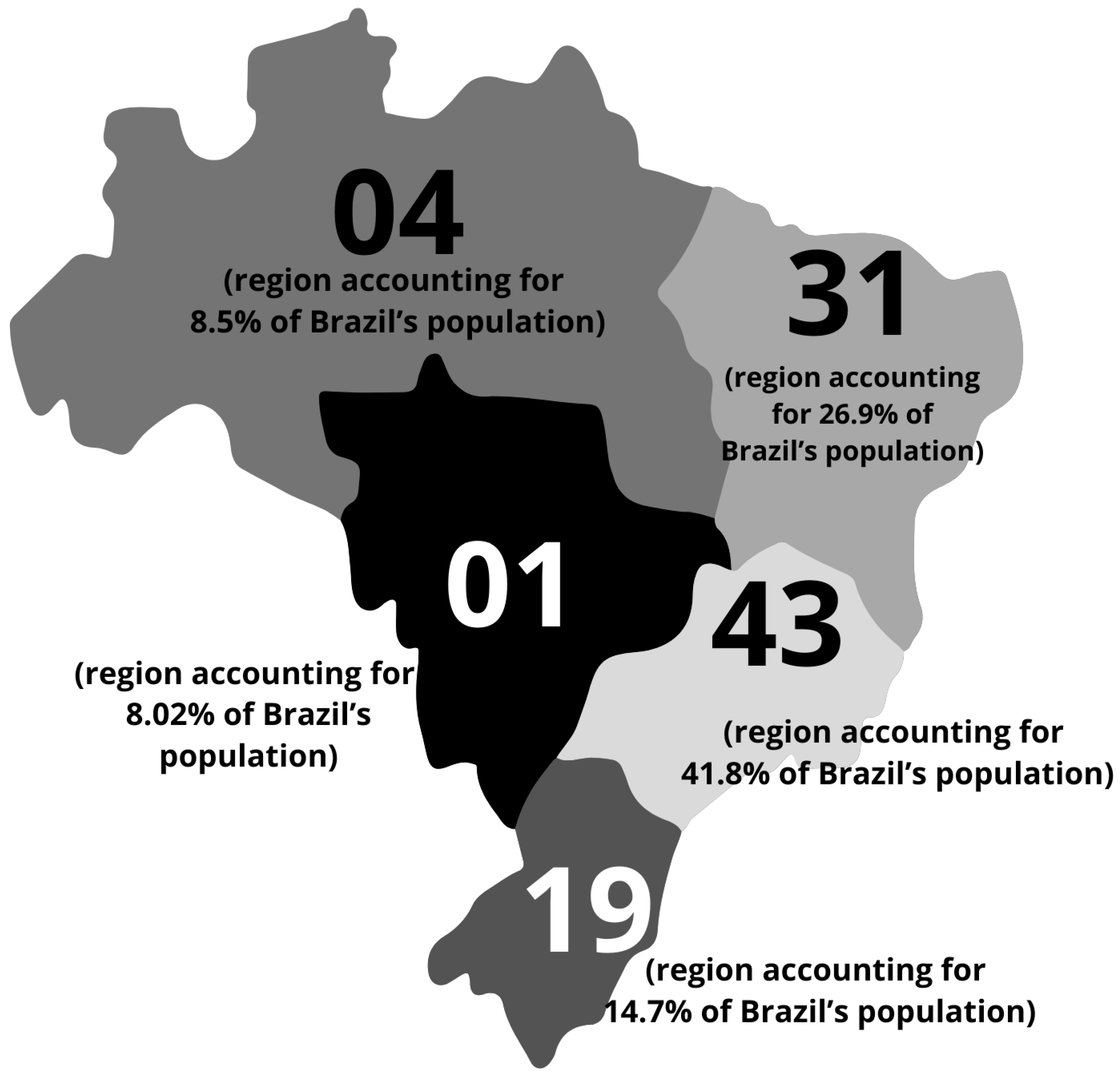

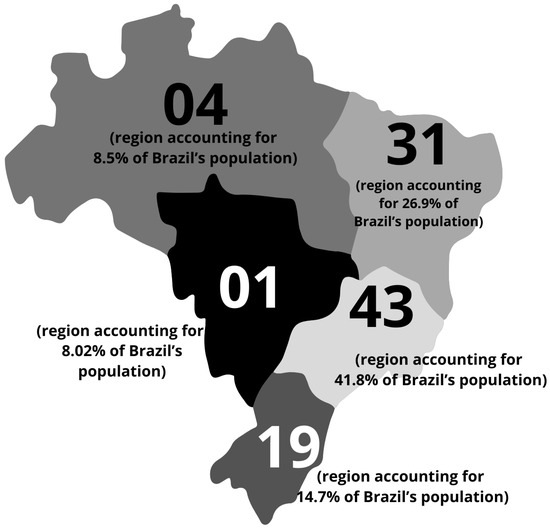

By 2025, the total number of confirmed MPS IIIC cases was 101 (Table 1). Among these patients, 60% (n = 59) were female and 40% (n = 42) were male. All patients were from Brazil. The geographic distribution of patients is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the population of patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis IIIC diagnosed through the MPS Brazil Network.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the Brazilian Mucopolysaccharidosis IIIC (MPS IIIC) population. Geographic distribution of patients diagnosed by the MPS Brazil Network across the Brazilian territory. The region with the highest prevalence of cases is the Southwest, accounting for 41.8% of all reported cases, followed by the Northeast (26.9%), South (14.7%), North (8.5%), and Midwest (8.5%).

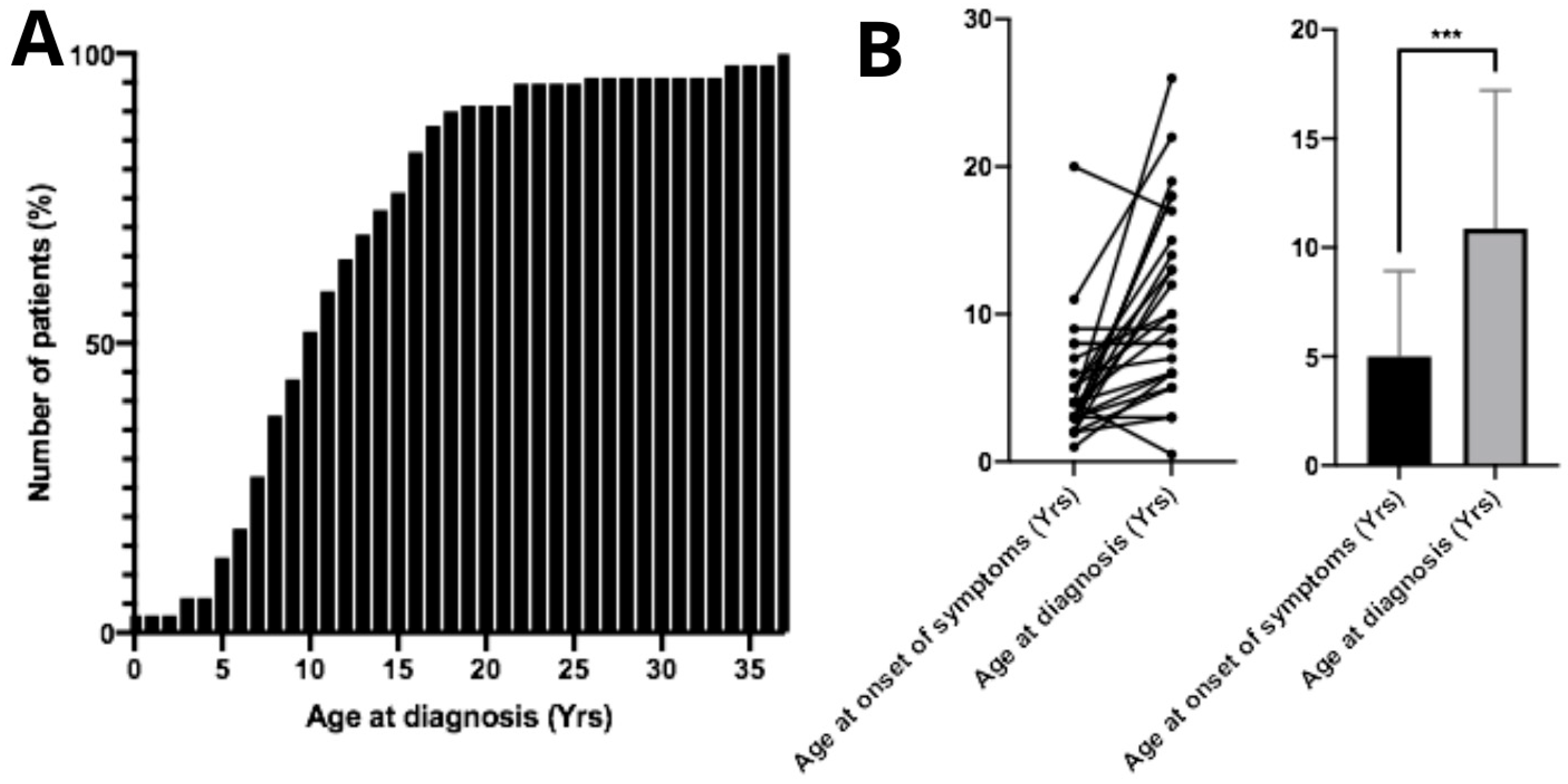

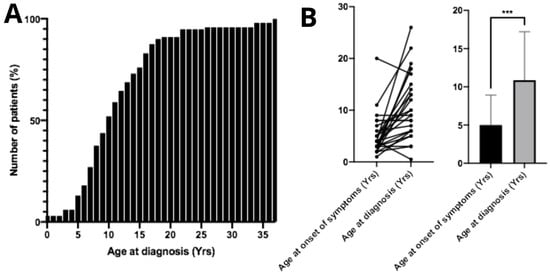

The mean age at diagnosis was 11.7 ± 6.92 years. Regarding the mean diagnostic age over the years, from 1983 to 2005 the average age at diagnosis was 9.25 years (n = 12); from 2006 to 2015 it increased to 11.74 years (n = 43); and from 2016 to 2025 the mean diagnostic age was 12.97 years (n = 34). From the diagnosed patients, only 13.5% (n = 13) were aged 5 years or younger at the time of diagnosis (Figure 2A). No correlation was found between age at diagnosis and patient gender (p > 0.05, n = 98). The mean age at symptom onset was 5.39 ± 3.91 years. The difference between mean age at symptom onset and mean age at diagnosis was statistically significant (p < 0.05, n = 26), demonstrating an average diagnostic delay of approximately 6 years (Figure 2B). Surprisingly, age of diagnosis of patients who had family members previously diagnosed with MPS IIIC did not show significant differences compared to the overall study population (p > 0.05, n = 26). Twenty-eight parents of MPS IIIC patients reported consanguineous marriage.

Figure 2.

Age at diagnosis and onset of first symptoms in patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIC. (A) Cumulative percentage of patients diagnosed according to age. The mean age at diagnosis among Brazilian patients is 11.7 ± 6.92 years. (B) A significant difference (*** p < 0.001) was observed between the age of symptom onset and the age at diagnosis, indicating a substantial diagnostic delay in these patients.

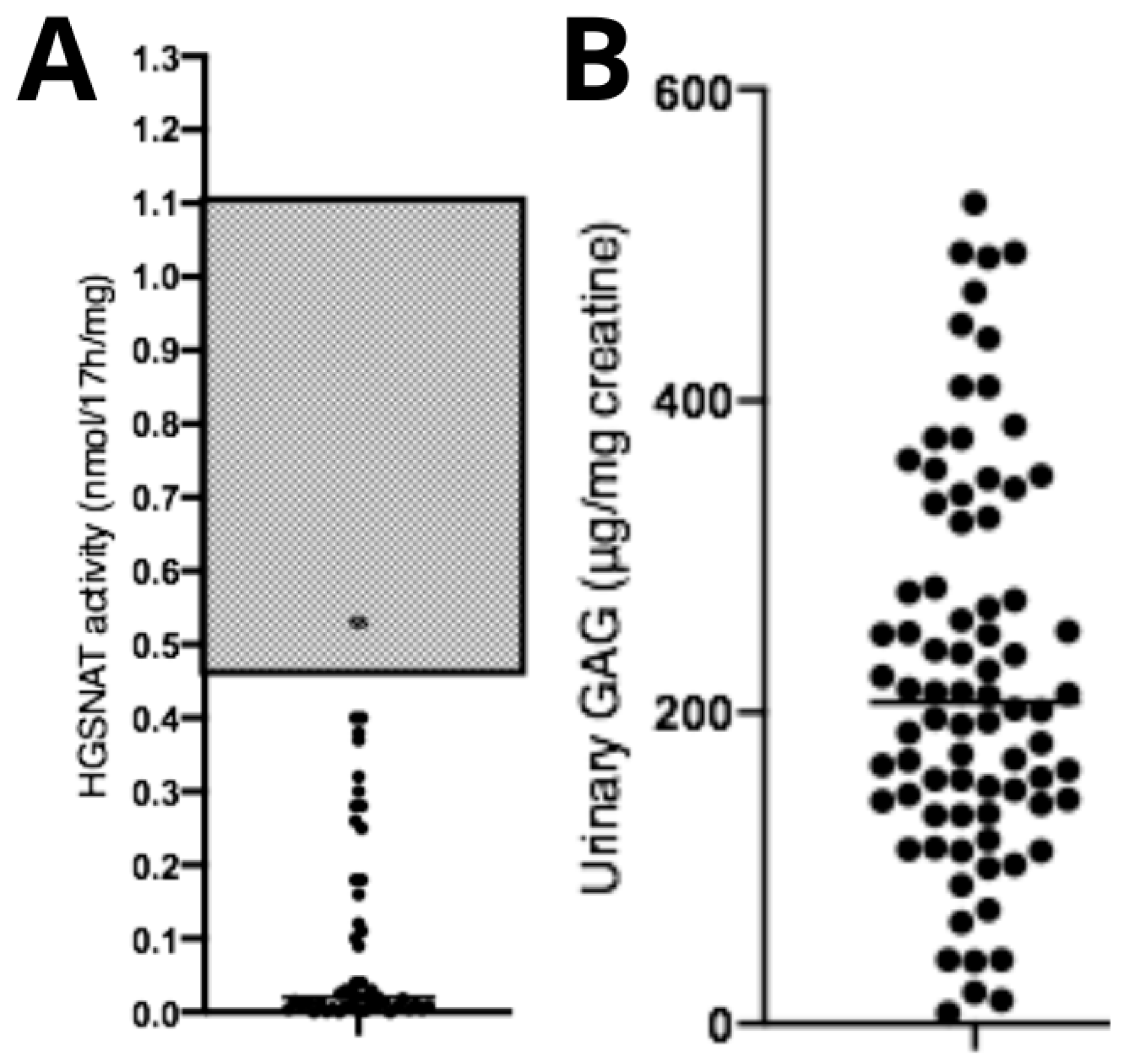

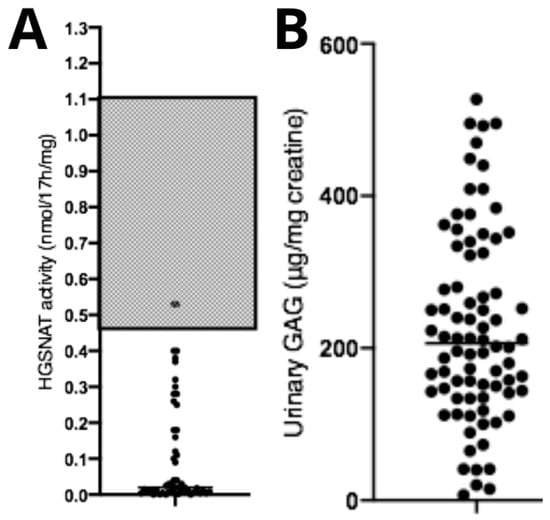

Diagnostic confirmation tests showed reduced HGSNAT enzymatic activity (0.11 ± 0.15 nmol/17 h/mg) (Figure 3A) and elevated urinary GAG concentration (226 ± 125.3 μg/mg creatinine—reference levels are age-dependent) (Figure 3B). No correlations were observed between age at diagnosis and HGSNAT enzyme activity (p > 0.05, n = 95), between uGAGs and HGSNAT enzyme activity (p > 0.05, n = 95), or between uGAGs and age at diagnosis (p > 0.05, n = 79).

Figure 3.

Biochemical data from patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIC. (A) Data showing reduced enzymatic activity compared with the typical reference range (gray area), and (B) a significant increase in urinary GAGs compared with normal reference values (not shown in the figure, as they fall below the displayed range and are age-dependent). Dots represent the patients values of uGAGs.

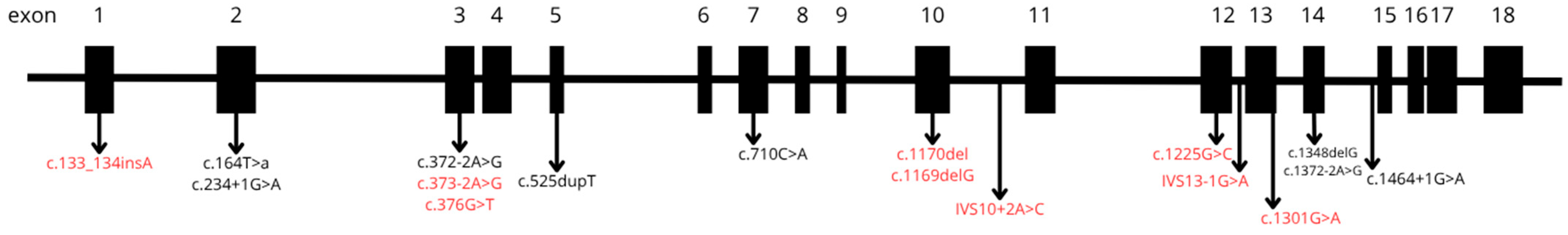

In twenty-eight percent (n = 28) of patients we had sample available and it was possible to perform molecular genetics investigation, with pathogenic variations being identified. The most frequent variants (n = 4 alleles) were c.372-2A>G and c.252dupT (p.Val176fs), followed by c.1169delG (p.Trp390fs) (n = 3), c.1348delG (p.Asp450fs) (n = 3), c.164T>A (p.Leu55Ter) (n = 3), IVS10-2A>C (n = 3), c.133_134insA (p.Arg45fs) (n = 2), and c.376G>T (p.Glu126Ter) (n = 2). Additionally, the following variants were each observed in a single patient: c.1170del (p.Trp390Cysfs*17), c.1225G>C (p.Gly409Arg), c.1301G>A (p.Cys434Tyr), c.1464+1G>A, c.1757 (p.Ser586Phe), c.234+1G>A, c.373-2A>G, and c.710C>A (p.Pro237Gln). The localization and structural alterations of these pathogenic variants are illustrated in Figure 4 and Table 1.

Figure 4.

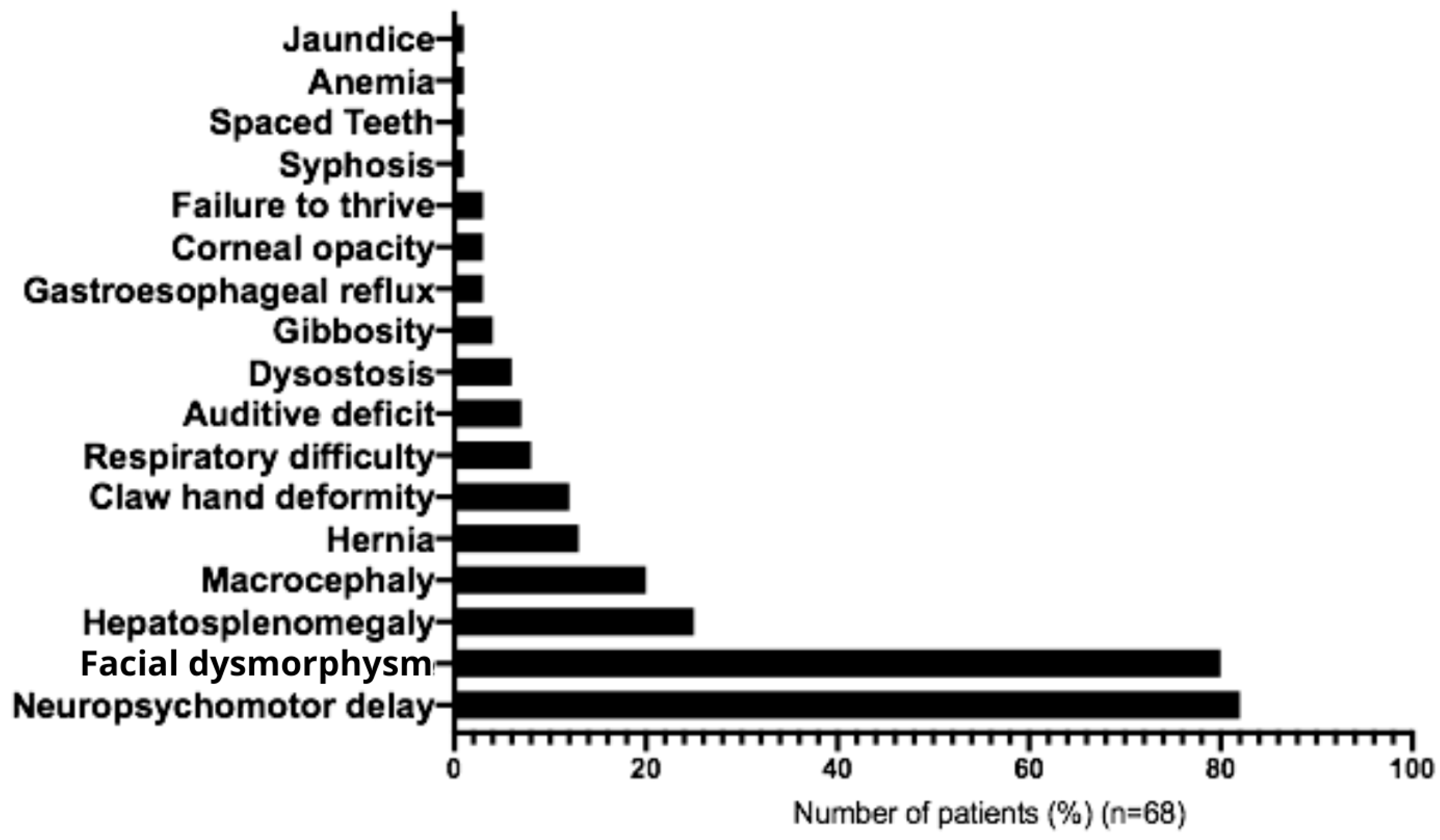

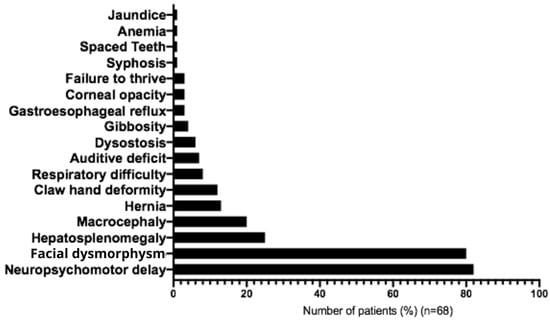

Clinical features observed in Brazilian patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIC at diagnosis.

The most frequent initial symptoms associated with MPS IIIC were developmental delay (82%), facial dysmorphism (80%), hepatosplenomegaly (25%), macrocephaly (20%), umbilical hernia (13%), joint contractures (12%), recurrent respiratory problems (9%), hearing impairment (7%), and bone dysplasia (6%) (Figure 5 and Table 2). In most cases, clinical diagnostic hypotheses correctly suggested mucopolysaccharidosis type III (90%), followed by unspecified mucopolysaccharidosis (40%), mucopolysaccharidosis type II (10%), and adrenoleukodystrophy (10%) (Table 3). Main behavioral symptoms reported were agitation (61.5%), aggressive behavior (38.5%), hyperactivity (20%), and autistic behavior (7%) (Table 1). The following medications were most commonly used for management of symptoms: carbamazepine (23%), Chlorpromazine (20%), Risperidone (17%), Periciazine (8.5%), Haloperidol (8.5%), Fluoxetine (6%), Amitriptyline (6%) and Valproic Acid (6%) (Table 4).

Figure 5.

Pathogenic variants identified in patients diagnosed by the MPS Brazil Network. Newly identified variants not previously described in the scientific literature are shown in red.

Table 2.

Signs and Symptoms in Brazilian patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis IIIC.

Table 3.

Initial diagnostic hypotheses on Brazilian patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIC.

Table 4.

Main medications prescribed for symptomatic management in patients with MPS IIIC.

Across Brazilian regions, we observed significant differences in the mean age at diagnosis, patient journey, and prevalence of consanguinity (Table 5). The patient journey was defined as the interval between the mean age at symptom onset and the mean age at diagnosis. Among regions with more than one representative patient, the North region had the lowest mean age at diagnosis (6.25 years, n = 4) and the shortest patient journey (3.25 years), followed by the South (10.2 years, n = 19; patient journey of 4.7 years), the Northeast (12 years, n = 31; patient journey of 7.7 years), and the Southeast (13 years; patient journey of 8.8 years). Regarding consanguinity, the highest prevalence was found in the Northeast (54% of reported unions, n = 24), followed by the Southeast (43%, n = 16) and the South (37.5%, n = 8).

Table 5.

Regional differences in Brazil regarding to diagnosis of MPS IIIC.

4. Discussion

We performed a retrospective analysis of patients diagnosed with MPS IIIC through the MPS Brazil Network, including data from 101 individuals. According to previous research by our group, the incidence of MPS IIIC in Brazil is 0.07 per 100,000 live births [20], a rate comparable to that reported in Australia (0.07:100,000) and Taiwan (0.03:100,000) [21,22]. Conversely, higher incidences have been described in France (0.15:100,000) [23], Portugal (0.12:100,000), the Czech Republic (0.42:100,000), and the Netherlands (0.21:100,000) [21]. Among the aforementioned studies, relevant comparisons were identified regarding the populations of patients with MPS IIIC. Considering the number of patients born in Brazil during the time period, we reach a minimal incidence of 0.09 in 100,000.

Besides frequency, other comparisons can be made: one of them refers to the age at diagnosis. In our cohort, the mean age at diagnosis was 11.7 ± 6.92 years. Similar results were reported in earlier studies, such as 12 years in France [23] and in the Netherlands [24]. More recent investigations, however, indicate a substantial reduction in diagnostic age, with reports of 4 years (range: 2–6) in Colombia [25], 7.6 ± 4.5 years in China [26], and similar findings in Korea [27]. Kuiper et al. [28] reported that the diagnostic odyssey remains high (33 months), highlighting the need for standardized guidelines and diagnostic workflows to address this issue. Our findings indicate a marked diagnostic delay in the Brazilian population, with values comparable to those reported in previous decades, despite the fact that diagnostic hypotheses proposed by Brazilian physicians were predominantly related to Mucopolysaccharidosis III (90%). Most of the physicians from the MPS Brazil network are medical geneticists, which suggests that knowledge of MPS III among this group is high, but it usually takes a lot of time to have these patients referred to a geneticist, possibly due to the unspecific symptoms. We searched for explanations for the diagnostic delay, but, surprisingly, we could not find differences in the time to diagnosis when comparing less developed regions of the country, such as the Northeast, with regions that have more resources, such as the Southeast. The time when patients were diagnosed also did not prove to be different, as the results for recently diagnosed patients are similar to those for patients diagnosed three or four decades ago.

In our study, the mean age at symptom onset was 5.39 ± 3.91 years, suggesting that the Brazilian cohort presents a comparatively milder phenotype. This is later than the averages reported in other countries, such as the Netherlands (3.5 years, range: 1–6) [24], Greece (2.5 years) [23], Korea (2.8 ± 0.8 years) [27], China (4.2 ± 2.5 years) [26], and the earlier of 4 years [29]. These data may also explain in part the apparent “diagnostic delay” observed in Brazil or may occur as a consequence of it.

In our cohort, the main findings in later symptom onset patients were primarily characterized by neurodevelopmental delay (82%), facial dysmorphism (80%), and hepatosplenomegaly (25%). By contrast, previous studies describing earlier onset patients reported a predominance of neurodevelopmental delay, behavioral problems, and diarrhea [24]. Behavioral manifestations, emphasized in the literature as highly prevalent [24,26,27], were observed in 25% of our patients. This discrepancy may reflect a comparatively milder phenotype in our population, or the fact that in many cases, we might not have a complete description of the symptoms. The fact that gastrointestinal manifestations, frequently reported in MPS IIIC populations worldwide [30,31], were underrepresented in our cohort, could also suggest that.

Among the pathogenic variants identified in Brazilian patients, several novel variants not previously reported in the literature were observed: c.133_134insA (p.Arg45fs), c.373-2A>G, c.1301G>A (p.Cys343Tyr), c.1169delG (p.Trp390fs), IVS10+2A>C, c.378G>T (p.Glu126Ter), c.1225G>C (p.Gly409Arg), c.1757C>T (p.Ser586Phe), c.376G>T (p.Glu126Ter), IVS13-1G>A, and c.1170del (p.Trp390Cysfs*17). Previously reported mutations identified in Brazilian patients include c.1348delG (p.Asp450fs), c.525dupT (p.Val176fs), c.234+1G>A, and c.164T>A (p.Leu55Ter) [16]. The phenotypic manifestations previously observed in these patients are consistent with those described in our cohort. Genotype–phenotype correlations were observed with Portuguese variants, namely c.372-2A>G and c.525dupT (p.Val176Cysfs*16), in relation to patients from our cohort [16,18]. Similarly, the pathogenic variants c.1464+1G>A (reported in Italian patients) [17] and c.710C>A (p.Pro237Gln) (described in Chinese patients) [19] also showed phenotypic features comparable to those observed in the Brazilian population. Although several studies have demonstrated a genotype-phenotype correlation [32,33,34], our statistical analysis did not reveal any significant associations for the novel variants identified in our cohort. Nevertheless, the presence of these variants in Brazil requires further investigation through ancestry-based analyses.

Although no specific treatment is currently available for MPS IIIC [35], several tools for symptomatic management have been described. Among the main clinical concerns is the control of behavioral manifestations. In our cohort, therapeutic approaches included antihistamines, melatonin, chloral hydrate, and benzodiazepines, consistent with previous reports in the literature [36]. As previously reported by our group, achieving homogeneous outcomes in patients with MPS III is not always feasible [4]. A notable example is the strong adherence to fluoxetine use among patients with MPS IIIA [37], whereas in our cohort, adherence to this medication was limited. The use of D1 dopamine receptor antagonists has recently been proposed for managing Autism Spectrum Disorder–related symptoms in these patients [38]; however, further clinical studies are required to confirm this hypothesis.

5. Conclusions

This study reports the largest cohort of Brazilian patients with MPS IIIC to date, providing new insights into the epidemiology, clinical features, and genetic spectrum of the disease in the country. Our findings highlight a later mean age at symptom onset and a significant diagnostic delay compared with more recent international reports, although the diagnostic hypotheses raised by physicians were largely accurate. The identification of several novel pathogenic variants expands the known mutational spectrum of HGSNAT and underscores the genetic heterogeneity of MPS IIIC in Brazil. Moreover, the genotype–phenotype correlations observed with Portuguese, Italian, and Chinese variants suggest possible founder effects and emphasize the need for ancestry-based analyses to clarify the distribution of these mutations in the Brazilian population. Despite advances in symptomatic management, the absence of disease-modifying therapies remains a critical challenge. It is important to highlight that the results presented in this study are limited by the lack of longitudinal follow-up regarding each patient’s clinical course. A properly designed natural history study will be required to address this point, as the methodological objective of the present report is restricted to the epidemiological characterization of the population, as previously stated. Taken together, our results reinforce the importance of early recognition, biochemical and genetic diagnosis, and continued investment in therapeutic research to improve outcomes for patients with MPS IIIC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H.A.M. and R.G.; Methodology, Y.H.A.M., A.C.B.-F. and R.G.; Validation, P.F.V.d.M. and R.G.; Formal analysis, Y.H.A.M., A.C.B.-F. and K.M.-T.; Investigation, Y.H.A.M., M.F.A.A., S.S.d.S.-L., F.d.O.P., A.C.B.-F. and G.B.; Data curation, Y.H.A.M., F.d.O.P., A.C.B.-F., F.B.-P., K.M.-T., F.M.S., F.B.T., E.M.R., P.F.V.d.M., C.A.K., E.K.E., M.R.-G., G.B. and R.G.; Writing–original draft, Y.H.A.M., M.F.A.A., S.S.d.S.-L. and R.G.; Writing–review & editing, Y.H.A.M., C.F.M.d.S., F.d.O.P., A.C.B.-F., F.B.-P., K.M.-T., F.M.S., F.B.T., E.M.R., P.F.V.d.M., C.A.K., E.K.E., M.R.-G. and G.B.; Visualization, R.G.; Supervision, R.G.; Project administration, R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank CNPq, CAPES and FAPERGS for financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the the Ethics Committee of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (protocol code GPPG: 03-066 and 14 February 2003l).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Federhen, A.; Pasqualim, G.; de Freitas, T.F.; Gonzalez, E.A.; Trapp, F.; Matte, U.; Giugliani, R. Estimated birth prevalence of mucopolysaccharidoses in Brazil. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2020, 182, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, Y.H.A.; de Souza, C.F.M.; Kubaski, F.; Trapp, F.B.; Burin, M.G.; Michelin-Tirelli, K.; Leistner-Segal, S.; Facchin, A.C.B.; Medeiros, F.S.; Giugliani, L.; et al. Sanfilippo syndrome type B: Analysis of patients diagnosed by the MPS Brazil Network. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2022, 188, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, Y.H.A.; Trapp, F.B.; Dos Santos-Lopes, S.S.; da Silva, K.B.L.; Baldo, G.; Giugliani, R.; de Oliveira Poswar, F. Survey of Patients with Sanfilippo Type a (MPS IIIA) Disease Diagnosed by the MPS Brazil Network. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2025, 197, e64026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, Y.H.A.; Baldo, G.; Giugliani, R.; Poswar, F.O.; Sobrinho, R.P.O.; Steiner, C.E. Schizophreniform presentation and abrupt neurologic decline in a patient with late-onset mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIB. Psychiatr. Genet. 2021, 31, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesley, C.; Moraitou, M.; Winchester, B.; Schulpis, K.; Dimitriou, E.; Michelakakis, H. Sanfilippo B syndrome: Molecular defects in Greek patients. Clin. Genet. 2004, 65, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valstar, M.J.; Ruijter, G.J.; van Diggelen, O.P.; Poorthuis, B.J.; Wijburg, F.A. Sanfilippo syndrome: A mini-review. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2008, 31, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, B.S.; Davison, J.; Jones, S.A.; Baruteau, J. Novel therapies for mucopolysaccharidosis type III. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2021, 44, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, T.; Kawashima, T.; Sakamoto, M. Rhodamine B inhibition of glycosaminoglycan production by cultured human lip fibroblasts. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1991, 111, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakóbkiewicz-Banecka, J.; Piotrowska, E.; Narajczyk, M.; Barańska, S.; Wegrzyn, G. Genistein-mediated inhibition of glycosaminoglycan synthesis, which corrects storage in cells of patients suffering from mucopolysaccharidoses, acts by influencing an epidermal growth factor-dependent pathway. J. Biomed. Sci. 2009, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenti, G.; Andria, G.; Valenzano, K.J. Pharmacological Chaperone Therapy: Preclinical Development, Clinical Translation, and Prospects for the Treatment of Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2015, 23, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfi, A.; Richard, M.; Gandolphe, C.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Thérond, P.; Scherman, D. Neuroinflammatory and oxidative stress phenomena in MPS IIIA mouse model: The positive effect of long-term aspirin treatment. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2011, 103, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matalonga, L.; Arias, A.; Coll, M.J.; Garcia-Villoria, J.; Gort, L.; Ribes, A. Treatment effect of coenzyme Q(10) and an antioxidant cocktail in fibroblasts of patients with Sanfilippo disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2014, 37, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubaski, F.; Sousa, I.; Amorim, T.; Pereira, D.; Silva, C.; Chaves, V.; Brusius-Facchin, A.C.; Netto, A.B.O.; Soares, J.; Vairo, F.; et al. Pilot study of newborn screening for six lysosomal diseases in Brazil. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023, 140, 107654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusius-Facchin, A.C.; Siebert, M.; Leão, D.; Malaga, D.R.; Pasqualim, G.; Trapp, F.; Matte, U.; Giugliani, R.; Leistner-Segal, S. Phenotype-oriented NGS panels for mucopolysaccharidoses: Validation and potential use in the diagnostic flowchart. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2019, 42, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muschol, N.; Storch, S.; Ballhausen, D.; Beesley, C.; Westermann, J.C.; Gal, A.; Ullrich, K.; Hopwood, J.J.; Winchester, B.; Braulke, T. Transport, enzymatic activity, and stability of mutant sulfamidase (SGSH) identified in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type III A. Hum. Mutat. 2004, 23, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.; de Medeiros, P.F.V.; Leistner-Segal, S.; Dridi, L.; Elcioglu, N.; Wood, J.; Behnam, M.; Noyan, B.; Lacerda, L.; Geraghty, M.T.; et al. Molecular characterization of a large group of Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIC patients reveals the evolutionary history of the disease. Hum. Mutat. 2019, 40, 1084–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, A.O.; Filocamo, M.; Di Rocco, M.; Sersale, G.; Lübke, T.; di Natale, P.; Cosma, M.P.; Ballabio, A. Mutational analysis of the HGSNAT gene in Italian patients with mucopolysaccharidosis IIIC (Sanfilippo C syndrome). Hum. Mutat. 2007, 28, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, M.F.; Lacerda, L.; Prata, M.J.; Ribeiro, H.; Lopes, L.; Ferreira, C.; Alves, S. Molecular characterization of Portuguese patients with mucopolysaccharidosis IIIC: Two novel mutations in the HGSNAT gene. Clin. Genet. 2008, 74, 194–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Tang, Y. Identification and characterization of novel genetic variants in the first Chinese family of mucopolysaccharidosis IIIC (Sanfilippo C syndrome). J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josahkian, J.A.; Trapp, F.B.; Burin, M.G.; Michelin-Tirelli, K.; Magalhães, A.P.P.S.; Sebastião, F.M.; Bender, F.; Mari, J.F.; Brusius-Facchin, A.C.; Leistner-Segal, S.; et al. Updated birth prevalence and relative frequency of mucopolysaccharidoses across Brazilian regions. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2021, 44, e20200138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poupetová, H.; Ledvinová, J.; Berná, L.; Dvoráková, L.; Kozich, V.; Elleder, M. The birth prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders in the Czech Republic: Comparison with data in different populations. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010, 33, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Lin, S.P.; Chuang, C.K.; Niu, D.M.; Chen, M.R.; Tsai, F.J.; Chao, M.C.; Chiu, P.C.; Lin, S.J.; Tsai, L.P.; et al. Incidence of the mucopolysaccharidoses in Taiwan, 1984–2004. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2009, 149A, 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Héron, B.; Mikaeloff, Y.; Froissart, R.; Caridade, G.; Maire, I.; Caillaud, C.; Levade, T.; Chabrol, B.; Feillet, F.; Ogier, H.; et al. Incidence and natural history of mucopolysaccharidosis type III in France and comparison with United Kingdom and Greece. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2011, 155A, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijter, G.J.; Valstar, M.J.; van de Kamp, J.M.; van der Helm, R.M.; Durand, S.; van Diggelen, O.P.; Wevers, R.A.; Poorthuis, B.J.; Pshezhetsky, A.V.; Wijburg, F.A. Clinical and genetic spectrum of Sanfilippo type C (MPS IIIC) disease in The Netherlands. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008, 93, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabarcas, L.; Ramón, J.L.; Espinosa, E.; Guerrero, G.P.; Martínez, N.; Santamaría, N.; Lince, I.; Reyes, S. Historia natural de la mucopolisacaridosis III en una serie de pacientes colombianos [Natural history of mucopolysaccharidosis type III in a series of Colombian patients]. Rev. Neurol. 2024, 78, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Gao, X.; Lu, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhang. Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIC in chinese mainland: Clinical and molecular characteristics of ten patients and report of six novel variants in the HGSNAT gene. Metab. Brain Dis. 2023, 38, 2013–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Yang, A.; Noh, E.S.; Kim, C.; Bae, G.Y.; Lim, H.H.; Park, H.D.; Cho, S.Y.; Jin, D.K. Natural History and Molecular Characteristics of Korean Patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis Type III. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuiper, G.A.; Meijer, O.L.M.; Langereis, E.J.; Wijburg, F.A. Failure to shorten the diagnostic delay in two ultra-orphan diseases (mucopolysaccharidosis types I and III): Potential causes and implications. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Kamp, J.J.; Niermeijer, M.F.; von Figura, K.; Giesberts, M.A. Genetic heterogeneity and clinical variability in the Sanfilippo syndrome (types A, B, and C). Clin. Genet. 1981, 20, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, F.; Hoffmann, S.; Kunzmann, K.; Ries, M. Challenging behavior in mucopolysaccharidoses types I-III and day-to-day coping strategies: A cross sectional explorative study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Ramaswami, U.; Cleary, M.; Yaqub, M.; Raebel, E.M. Gastrointestinal Manifestations in Mucopolysaccharidosis Type III: Review of Death Certificates and the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beesley, C.E.; Jackson, M.; Young, E.P.; Vellodi, A.; Winchester, B.G. Molecular defects in Sanfilippo syndrome type B (mucopolysaccharidosis IIIB). J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2005, 28, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.G.; Aronovich, E.L.; Whitley, C.B. Genotype-phenotype correspondence in Sanfilippo syndrome type B. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998, 62, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogalingam, G.; Weber, B.; Meehan, J.; Rogers, J.; Hopwood, J.J. Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIB: Characterisation and expression of wild-type and mutant recombinant alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase and relationship with sanfilippo phenotype in an attenuated patient. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1502, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyazidi, A.S.; Muthaffar, O.Y.; Baaishrah, L.S.; Shawli, M.K.; Jambi, A.T.; Aljezani, M.A.; Almaghrabi, M.A. Current Concepts in the Management of Sanfilippo Syndrome (MPS III): A Narrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e58023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escolar, M.L.; Jones, S.A.; Shapiro, E.G.; Horovitz, D.D.G.; Lampe, C.; Amartino, H. Practical management of behavioral problems in mucopolysaccharidoses disorders. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 122S, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuozzo, A.; Montefusco, S.; Cacace, V.; Sofia, M.; Esposito, A.; Napolitano, G.; Nusco, E.; Polishchuk, E.; Pizzo, M.T.; De Risi, M.; et al. Fluoxetine ameliorates mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2022, 30, 1432–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risi, M.; Cusimano, L.; Bujanda Cundin, X.; Pizzo, M.; Gigante, Y.; Monaco, M.; Di Eugenio, C.; De Leonibus, E. D1 dopamine receptor antagonists as a new therapeutic strategy to treat autistic-like behaviours in lysosomal storage disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 2980–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.