Abstract

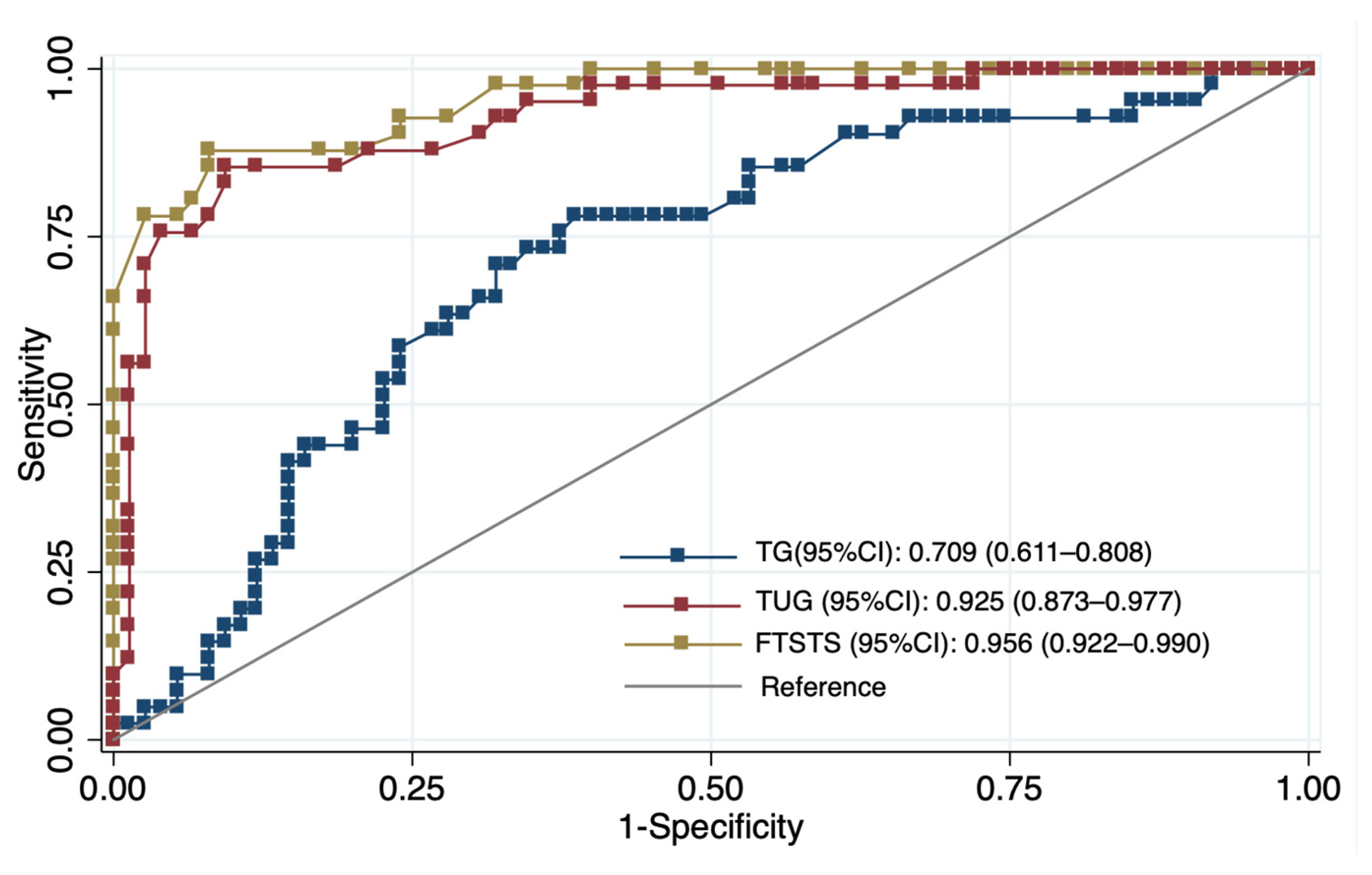

Background and Objectives: Metabolic syndrome (MetS) has been associated with reduced physical function in older adults, but the relative contributions of metabolic components, physiological responses, and functional performance to walking capacity remain unclear. Materials and Methods: This cross-sectional study included 116 community-dwelling adults aged ≥60 years (mean age 68.5 ± 5.5 years; 65.5% female). Walking capacity was evaluated using the six-minute walk test (6MWT) with associated physiological responses. Functional performance was assessed using the five-times-sit-to-stand test (FTSST), timed-up-and-go (TUG), and handgrip strength. Associations with six-minute walk distance (6MWD) were examined using hierarchical regression analyses, and discriminatory performance was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic analysis. Results: Participants with MetS demonstrated shorter 6MWD, slower FTSST and TUG performance, and higher dyspnea ratings compared to those without MetS (p < 0.05). Triglycerides were inversely associated with 6MWD in intermediate models (β = −0.33, p < 0.001), but after full adjustment, only ΔSBP (β = 0.76, p = 0.008) and FTSST (β = −24.45, p < 0.001) remained significant. The FTSST and TUG demonstrated excellent discriminatory ability, with AUC values of 0.956 (cut-off ≥ 15.5 s) and 0.925 (cut-off ≥ 13.7 s), respectively, whereas triglycerides showed moderate accuracy (AUC = 0.709) with a cut-off of ≥143 mg/dL. Conclusions: Walking capacity was more strongly associated with physiological and functional measures than with metabolic biomarkers. The FTSST and TUG showed strong discriminatory performance for low walking capacity, whereas metabolic markers provided complementary contextual information.

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a major global public health concern defined by the coexistence of central obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and impaired glucose regulation. Individuals with MetS are at substantially increased risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease and experience significantly higher healthcare utilization and costs [1]. Beyond cardiometabolic morbidity, MetS has also been associated with poorer mental health and reduced health-related quality of life [2]. Current management strategies focus primarily on lifestyle modification, including weight control, dietary improvement, increased physical activity, and smoking cessation, with pharmacological treatment commonly required to manage individual metabolic abnormalities [3]. Despite these evidence-based strategies, the functional consequences of MetS, particularly its impact on mobility in older adults, remain incompletely understood.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is increasingly recognized as a multisystem disorder affecting multiple organs, including the heart, liver, vasculature, kidneys, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and immune system [4]. Evidence from prior studies indicates that these widespread effects are linked to chronic low-grade inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, hormonal dysregulation, and metabolic disturbances that promote oxidative stress, lipotoxicity, and glucotoxicity [4,5]. Several circulating biomarkers have been proposed to reflect this metabolic and inflammatory milieu, including triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), C-reactive protein (CRP), leptin, and adiponectin [6]. In individuals with MetS, elevated TG and LDL-C, reduced HDL-C, and increased CRP are commonly observed and are widely interpreted as indicators of metabolic and inflammatory stress [7,8]. Prior literature suggests that such dysregulated biomarker profiles may be associated with endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance, and impaired lipid metabolism, which may in turn contribute to vascular impairment, hepatic steatosis, and altered skeletal muscle metabolism [9,10,11].

Growing evidence indicates that MetS is associated with impaired physical function beyond its cardiometabolic complications. Previous studies have shown that MetS is linked to subclinical vascular abnormalities [12], elevated oxidative and inflammatory burden [5], frailty, sedentary behavior, and reduced muscle strength [13,14]. Individuals with MetS commonly exhibit poorer mobility, weaker lower-extremity power, reduced balance, and lower cardiorespiratory fitness [15,16,17]. These functional limitations may result from impaired oxygen delivery, neuromuscular inefficiency, and reduced physiological resilience [18,19]. Consequently, older adults with MetS may experience early mobility decline and increased vulnerability to disability.

The six-minute walk test (6MWT) is a widely used and well-validated measure of submaximal exercise capacity in older adults and individuals with cardiometabolic disorders [20]. The 6MWT correlates closely with maximal oxygen uptake and is sensitive to limitations in endurance and overall mobility [21,22]. In addition to reflecting cardiopulmonary capacity, the 6MWT captures functional aspects of daily ambulation and has been shown to identify early mobility decline in older individuals with metabolic abnormalities [23,24]. However, walking capacity is influenced not only by endurance but also by lower-limb strength, balance, and movement control [20,25]. Because walking performance is also influenced by lower-limb strength, balance, and movement control, complementary functional assessments such as the five-times-sit-to-stand test (FTSST), the timed-up-and-go test (TUG), and handgrip strength are commonly used to capture these additional functional domains [26]. Together, these measures provide a more comprehensive assessment of physical function and are practical tools for detecting early functional decline in community-dwelling older adults.

Although previous studies have explored associations between MetS and functional capacity, relatively few have simultaneously examined metabolic components, physiological responses to exertion, and multiple functional performance measures within a single analytic framework [15,16,17]. In addition, existing evidence remains inconsistent regarding whether metabolic biomarkers or functional parameters are more strongly associated with walking capacity in older adults [24,27]. Consequently, the relative contributions of metabolic factors compared with cardiovascular responsiveness and functional performance remain insufficiently defined.

To our knowledge, this study is among the few to concurrently examine the associations between MetS components, physiological responses during the 6MWT, and multiple functional performance measures in community-dwelling older adults. Consequently, the principal objective of this study was to investigate the correlations among MetS components, physiological responses and functional performance, evaluated through 6MWD, FTSST, TUG, and handgrip strength. The secondary aim was to evaluate the discriminatory performance of selected metabolic and functional measures for identifying walking capacity. By integrating metabolic, physiological, and functional domains, this study provides additional evidence to support hypothesis-driven screening approaches for mobility limitation in older adults with metabolic abnormalities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the Dongjen Health Promotion Center, a community-based primary healthcare facility in Phayao Province, northern Thailand. The sample size was calculated using GPower software (version 3.1.9.7) for multiple linear regression analysis. A medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) was assumed according to Cohen’s conventions [28], with a two-sided significance level of 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.90. Based on these parameters, a minimum sample size of 116 participants was required. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Phayao (Approval No. HREEC-UP-HSST 1.2/047/68). All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Participants were eligible if they were community-dwelling adults aged 60 years or older, were independent in activities of daily living, and could ambulate independently without walking aids. Exclusion criteria included: (1) musculoskeletal disorders associated with severe pain (e.g., osteoarthritis, gout, rheumatoid arthritis); (2) cognitive impairment, functionally identified as inability to comprehend and execute standardized instructions during the screening interview; (3) recent lower-limb injury or surgery; and (4) uncontrolled hypertension, unstable coronary artery disease, respiratory disease, or active infection.

Participants were classified as having MetS or non-MetS using the updated National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) criteria [29]. MetS was defined by the presence of at least three of the following components: (1) waist circumference (WC) ≥ 102 cm in men or ≥88 cm in women; (2) TG ≥ 150 mg/dL; (3) HDL-C < 40 mg/dL in men or <50 mg/dL in women; (4) blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg; and (5) fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥ 100 mg/dL.

2.2. Demographic, Anthropometric, and Metabolic Assessment

Baseline demographic, anthropometric, and metabolic data were collected from all participants. Age and sex were obtained through structured interviews. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2), and WC was measured at the midpoint between the lowest rib and the iliac crest using a non-elastic tape. Physical activity was assessed using the Thai version of the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ, version 2) [30]. GPAQ results were expressed as continuous data in metabolic equivalent (MET)-minutes per week according to World Health Organization guidelines.

For metabolic assessment, after an 8–12 h overnight fast, venous blood samples were collected, and serum was used for biochemical analysis. FBG, TG and HDL-C were measured using enzymatic methods on an automated Sysmex BX-Series chemistry analyzer with commercially available reagents (DiaSys Diagnostic Systems GmbH, Holzheim, Germany) under standard quality control procedures.

2.3. Functional Assessments

All functional assessments, including the 6MWT, FTSST, TUG, and handgrip strength, were administered by licensed physical therapists with over five years of clinical experience. Functional-test assessors were blinded to participants’ metabolic and laboratory data to minimize measurement bias.

6MWT: Functional exercise capacity was assessed using the 6MWT conducted along a 30 m indoor corridor. Participants were instructed to walk as far as possible within six minutes without running [20]. Before and immediately after the test, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate (HR), and peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) were measured using an automated sphygmomanometer (Omron Health Care, Kyoto, Japan) and a pulse oximeter (Nellcor™, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Perceived dyspnea and leg fatigue were rated on the modified Borg scale (0–10). The total 6MWD was recorded, and physiological responses were expressed as the change between pre- and post-test values (ΔSBP, ΔHR, ΔSpO2).

FTSST: Lower-limb strength and balance were assessed using the FTSST. Participants sat on a 43 cm armless chair with arms crossed and completed five sit-to-stand cycles as quickly as possible without arm support. Timing started at “go” and ended upon sitting after the fifth stand, with total time recorded using a stopwatch [31].

TUG: Mobility and dynamic balance were assessed using the TUG. Participants started seated in the same chair and, on the word “go,” stood up, walked three meters at a comfortable pace, turned around, walked back, and sat down. The total time to complete the task was recorded using a stopwatch [32].

Handgrip strength: Upper-limb strength was assessed using a handgrip dynamometer (TKK 5001; Takei Scientific Instruments, Niigata, Japan). Participants stood with the dominant arm in a neutral position and performed a maximal isometric contraction for about 3 s. Three trials were performed with 15 s rest intervals, and the highest value was recorded for analysis [33].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as frequency (%) for categorical variables. Between-group comparisons (MetS vs. non-MetS) were conducted using appropriate statistical tests based on data distribution: independent t-tests for normally distributed variables (e.g., BMI, WC, SBP, DBP, 6MWD), Mann–Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed variables (e.g., FBG, HDL-C, TG, FTSST, TUG, dyspnea, physical activity), and chi-square (χ2) tests for categorical variables. Because sex distribution differed significantly between groups, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was additionally conducted for functional and physiological performance outcomes (6MWD, FTSST, TUG, handgrip strength, dyspnea, and leg fatigue), with sex included as a covariate.

Associations between TG levels and metabolic, physiological, and functional outcomes were examined using Spearman’s rank correlation. Simple and multiple linear regression analyses were then performed with TG as the independent variable. All adjusted models included age, sex, BMI, and physical activity as covariates due to their known influence on metabolic and functional outcomes. Results are presented as standardized regression coefficients (β) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). To identify determinants of walking capacity, hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted using 6MWD as the dependent variable. Model 1 included demographic and anthropometric variables (age, sex, BMI, physical activity). Model 2 added metabolic biomarkers (TG, HDL-C, FBG). Model 3 further incorporated physiological responses (ΔSBP, ΔHR, ΔSpO2) and functional performance (FTSST). Because FTSST and TUG were highly correlated (r = 0.864, p < 0.001), only FTSST was retained to avoid multicollinearity and redundancy. All regression models were evaluated for linearity, normality of residuals, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity using residual plots and variance inflation factors (VIFs). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were performed to assess the discriminatory ability of TG, FTSST, and TUG for walking capacity [34]. The area under the curve (AUC) with 95% CI, optimal cutoff values, sensitivity, specificity, and Youden’s J index were calculated. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 174 community-dwelling older adults were approached and screened for eligibility at community health centers. Following the screening process, 58 individuals were excluded due to cognitive impairment (n = 6), mobility-limiting conditions (n = 9), incomplete laboratory data (n = 30), or other reasons including declining participation or medical contraindications identified during preliminary assessment (n = 13). The remaining 116 participants were included in the final analysis. Based on metabolic syndrome criteria, 58 participants were classified into the MetS group and 58 into the non-MetS group. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 116 participants. The MetS group had a significantly higher proportion of females than the non-MetS group (77.6% vs. 53.4%, p = 0.006), while age did not differ between groups (p > 0.05). Compared with individuals without MetS, those with MetS showed higher BMI, WC, SBP, FBG, TG, and TG/HDL-C ratio, as well as lower HDL-C levels (p < 0.05). DBP and physical activity levels were comparable between groups, as reflected by similar GPAQ scores (1412 ± 1434 vs. 1307 ± 682 MET-min/week; p = 0.594). Additionally, the MetS group exhibited significantly shorter 6MWD, slower FTSST and TUG performance, and higher dyspnea ratings (p < 0.05, sex-adjusted ANCOVA). Handgrip strength and leg fatigue did not differ significantly between groups (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by metabolic syndrome status.

3.2. Associations Between Triglyceride Levels and Physiological-Functional Outcomes

The correlations showed that TG was positively associated with WC (rho = 0.20, p = 0.029) and moderately associated with poorer functional performance, including slower FTSST (rho = 0.41, p < 0.001) and slower TUG times (rho = 0.47, p < 0.001). TG was also negatively correlated with 6MWD (rho = −0.49, p < 0.001) and inversely correlated with ΔSBP (rho = −0.27, p = 0.004). Meanwhile, associations with HDL-C, FBG, ΔHR, ΔSpO2, handgrip strength, dyspnea and leg fatigue were not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations between triglyceride levels and metabolic, physiological, and functional outcomes among community-dwelling older adults (n = 116).

After adjustment for age, sex, BMI, and physical activity, TG levels remained inversely associated with ΔSBP (β = −0.286, 95% CI: −0.467 to −0.105, p = 0.003). A positive association with ΔSpO2 was also observed (β = 0.224, 95% CI: 0.037 to 0.411, p = 0.019), whereas no significant association with ΔHR was found (p = 0.261). Regarding functional capacity, higher TG levels were associated with shorter 6MWD (β = −0.382, 95% CI: −0.556 to −0.207, p < 0.001), slower FTSST performance (β = 0.291, 95% CI: 0.122 to 0.460, p = 0.001), and longer TUG time (β = 0.316, 95% CI: 0.152 to 0.480, p < 0.001). TG was also associated with weaker handgrip strength (β = −0.038, 95% CI: −0.063 to −0.013, p < 0.001). In contrast, no significant associations were observed for perceived dyspnea (p = 0.060) or leg fatigue (p = 0.885) (Table 2).

3.3. Predictors of Six-Minute Walk Distance

In the hierarchical regression analysis, Model 1, which included demographic and anthropometric variables, explained a small proportion of variance in 6MWD (adjusted R2 = 0.050, p = 0.035). In this model, female sex was associated with shorter walking distance (β = −27.88, p = 0.018), whereas higher physical activity levels (GPAQ) were positively associated with 6MWD (β = 0.012, p < 0.05). The addition of metabolic biomarkers in Model 2 significantly improved model fit (adjusted R2 = 0.213, p < 0.001), with TG emerging as a negative predictor of 6MWD (β = −0.33, p < 0.001), while FBG showed a nonsignificant trend (β = −0.34, p = 0.071). When physiological (ΔSBP, ΔHR, ΔSpO2) and functional (FTSST) variables were included in Model 3, the explanatory power increased markedly (adjusted R2 = 0.657, p < 0.001). In the final model, ΔSBP was positively associated with 6MWD (β = 0.76, p = 0.008), whereas longer FTSST times were strongly associated with shorter walking distance (β = −24.45, p < 0.001). In contrast, TG, HDL-C, and FBG were no longer significant predictors after accounting for physiological and functional variables (Table 3). Assessment of model assumptions indicated heteroskedasticity, and robust standard errors were applied. No evidence of multicollinearity was observed (VIF < 2).

Table 3.

Multiple regression predicting six-minute walk distance (6MWD) among community-dwelling older adults (n = 116).

3.4. Discriminatory Accuracy for Identifying Low Walking Capacity

The ROC analysis revealed clear differences in discriminatory performance between functional tests and metabolic biomarkers. The FTSST (AUC = 0.956, 95% CI 0.922–0.990) and TUG (AUC = 0.925, 95% CI 0.873–0.977) demonstrated excellent ability to distinguish individuals with low walking capacity. In contrast, triglycerides showed only fair discriminatory performance (AUC = 0.709, 95% CI 0.611–0.808). Based on Youden’s index, the optimal cut-off values were FTSST ≥ 15.5 s (sensitivity 90.20%, specificity 76.00%), TUG ≥ 13.7 s (sensitivity 85.40%, specificity 81.3%), and TG ≥ 143 mg/dL (sensitivity 70.70%, specificity 68.00%) (Figure 1, Table 4).

Figure 1.

ROC curves demonstrating the discriminative ability of triglycerides (TG), the five-times-sit-to-stand test (FTSST), and the timed-up-and-go test (TUG) to identify low six-minute walk distance (n = 116).

Table 4.

ROC analysis for identifying low walking capacity among community-dwelling older adults (n = 116).

4. Discussion

Our main findings can be summarized as follows. First, older adults with MetS exhibited less favorable metabolic profiles, attenuated cardiovascular responses during the 6MWT, and poorer functional performance than those without MetS. Second, functional measures, particularly FTSST performance and SBP response, emerged as the strongest determinants of 6MWD in adjusted models, while TG levels provided complementary metabolic context. Third, the FTSST showed excellent discriminative accuracy for identifying low walking capacity, while TG demonstrated moderate accuracy and did not independently predict mobility limitation, supporting the use of functional tests as sufficient tools for identifying impaired walking capacity, with TG providing complementary metabolic context.

Our study demonstrated that older adults with MetS exhibited consistently poorer functional capacity—including shorter 6MWD, slower FTSST and TUG performance, and higher dyspnea ratings—compared with those without MetS. These findings align with previous work indicating that MetS is associated with reduced aerobic capacity, slower gait speed and diminished lower-extremity strength [16,17,35]. The higher dyspnea ratings observed in our MetS group may be partly explained by earlier reports suggesting reduced ventilatory and cardiovascular responsiveness during activity, alongside increased metabolic demand and breathing effort [36,37]. Although our study did not directly assess ventilatory mechanics, these theoretical mechanisms are consistent with the broader literature. The poorer FTSST and TUG performance also agree with prior findings linking abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia and impaired glucose regulation to reduced movement efficiency and impaired mobility [15,38,39]. In contrast, handgrip strength did not differ between groups, supporting evidence that upper-limb strength has only a weak association with metabolic risk and mobility [40]. Likewise, the lack of group differences in leg fatigue suggests that subjective perceptions of exertion may be less sensitive than objective lower-limb performance tests, consistent with reports that gait characteristics often remain stable despite experimentally induced fatigue [41].

In regression analyses, TG was initially associated with shorter walking distance, slower functional performance and a blunted SBP response. However, these associations were substantially attenuated in fully adjusted models, and TG demonstrated only moderate discriminatory ability (AUC = 0.709). These results indicate that TG does not function as an independent determinant of 6MWD in this study. Prior research similarly shows that TG lose predictive value for mobility once central obesity, blood pressure and functional performance are considered [16,27]. Studies reporting inverse relationships between the TG/HDL-C ratio and muscle strength [42] further support the interpretation that triglyceride-related dysregulation may relate more to muscle quality than to walking-specific performance. Additional evidence indicates that combinations of MetS components contribute to functional disability [43], reinforcing that metabolic burden is multidimensional rather than driven by TG alone.

The potential mechanism underlying the role of TG in walking capacity in older adults remains unclear. Several biological pathways have been proposed to contribute to functional decline associated with metabolic abnormalities. These include endothelial dysfunction related to dyslipidemia and reduced nitric oxide bioavailability [7,44], intramuscular lipid accumulation and lipotoxicity that impair muscle contractile efficiency [45], and reduced mitochondrial oxidative capacity that limits ATP production and endurance [46,47]. Microvascular dysregulation, including impaired capillary recruitment and restricted oxygen delivery during exertion, has also been documented in individuals with metabolic dysregulation [5,48]. The multisystem effects of metabolic syndrome, such as vascular stiffness, chronic low-grade inflammation, and disrupted muscle vascular crosstalk, may further exacerbate mobility limitations in older adult [27,49]. Hypertriglyceridemia may also impair exercise tolerance through alterations in blood rheology, including increased plasma viscosity and erythrocyte aggregation [50]. Hyperglycemia-induced disturbances in redox balance and oxidative stress may worsen both vascular and muscular function [51,52]. Although these mechanisms were not directly evaluated in the present study, they remain plausible pathways that may contextualize the observed associations and guide future research aimed at clarifying these metabolic effects.

Our hierarchical regression analyses showed that ΔSBP and FTSST were the strongest determinants of 6MWD. These results are consistent with earlier studies emphasizing the importance of cardiovascular responsiveness and lower-limb functional performance in sustaining walking capacity [53,54,55,56]. An adequate rise in SBP during activity reflects preserved autonomic regulation, vascular compliance and the capacity to augment cardiac output [57]. In contrast, the blunted SBP response observed in the MetS group may signify impaired baroreflex sensitivity, increased arterial stiffness or reduced vasomotor responsiveness [58,59]. These cardiovascular abnormalities are well-described consequences of metabolic dysregulation and have been linked to reduced aerobic capacity and diminished exercise tolerance in aging population [37,60].

The discriminative analyses indicate that functional performance measures are the strongest indicators of low walking capacity in older adults, whereas metabolic markers provide complementary contextual information. TG levels demonstrated moderate discriminative ability in ROC analysis (AUC = 0.709), with an optimal cut-off value of 143 mg/dL, yielding balanced sensitivity (70.7%) and specificity (68.0%). This threshold is close to the clinical definition of hypertriglyceridemia (≥150 mg/dL) [61]. However, TG showed weaker performance than functional measures and did not remain independently associated with walking capacity in fully adjusted models, suggesting that metabolic biomarkers alone provide limited explanatory value. Although triglycerides did not enhance discrimination beyond functional tests, modest elevations may reflect underlying cardiometabolic alterations that have been associated in prior studies with reduced skeletal muscle energy metabolism and impaired oxygen utilization [47,62,63,64].

In contrast, functional measures demonstrated excellent discriminative performance. The FTSST (AUC = 0.956, 95% CI 0.922–0.990) and the TUG (AUC = 0.925, 95% CI 0.873–0.977) accurately identified individuals with low walking capacity, with optimal thresholds of 15.5 s and 13.7 s, respectively. These cut-off values are consistent with previous evidence linking prolonged FTSST and TUG times to reduced mobility and increased fall risk among community-dwelling older adults [65,66]. The superior performance of these tests likely reflects their ability to capture integrated functional capacity, including lower-limb strength, balance, coordination, and movement efficiency, which are essential for gait performance and functional independence [67].

Overall, these results indicate that TG, the FTSST and the TUG represent complementary dimensions of mobility limitation in older adults. TG reflects systemic metabolic burden, while FTSST and TUG directly capture neuromuscular and balance-related determinants of walking capacity. Integrating metabolic and functional assessments may therefore enhance early detection of mobility decline. In resource-limited primary care and community settings, combining simple functional tests with routine lipid profiling may provide a practical and cost-effective approach to identify at-risk individuals and guide timely interventions.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference between metabolic abnormalities, cardiovascular responses, and functional performance. Second, cognitive status was not formally assessed using standardized neurocognitive instruments; although participants were able to follow test instructions, subtle cognitive impairments that may influence mobility cannot be fully excluded. Third, several clinical and behavioral factors that may affect both metabolic status and mobility, including medication use, habitual diet, objectively measured physical activity, and inflammatory markers, were not comprehensively assessed. The absence of these variables may partly explain the attenuation of triglyceride-related associations in adjusted models. Fourth, dyspnea and leg fatigue were assessed using subjective ratings, which may limit sensitivity for detecting exertional abnormalities. Fifth, although both men and women were included, the study was not powered for sex-stratified analyses, and the modest sample size and single-center recruitment may limit generalizability. Finally, mechanistic physiological measures, such as endothelial function, skeletal muscle composition, mitochondrial activity, and blood rheology, were not directly evaluated. Future longitudinal studies with comprehensive metabolic and physiological assessments are needed to clarify causal pathways linking metabolic dysregulation to mobility decline.

5. Conclusions

MetS was associated with reduced walking capacity and poorer functional performance in community-dwelling older adults. TG showed limited independent association with walking capacity, whereas functional measures, particularly the FTSST and systolic blood pressure response during the 6MWT, were the strongest indicators of mobility limitation, supporting the use of simple functional tests for clinical identification of impaired walking capacity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and C.K. (Chiraphat Kloypan); methodology, A.S., C.K. (Chiraphat Kloypan), and T.P.; validation, A.S., T.P. and C.K. (Chiraphat Kloypan); formal analysis, A.S. and T.P.; investigation, A.S., C.K. (Chiraphat Kloypan), T.P., B.S. and C.K. (Chonticha Kaewjoho); resources, B.S. and C.K. (Chonticha Kaewjoho); data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and C.K. (Chiraphat Kloypan); writing—review and editing, A.S., C.K. (Chiraphat Kloypan), B.S., T.P. and C.K. (Chonticha Kaewjoho); visualization, A.S., C.K. (Chiraphat Kloypan), and T.P.; supervision, C.K. (Chiraphat Kloypan); project administration, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Research Grant of the School of Medicine, University of Phayao, Thailand (grant number MD68-07).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Phayao (protocol code HREEC-UP-HSST 1.2/047/68; date of approval: 4 March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions related to participant privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all study participants, the trained village health volunteers, and the staff of the Dongjen Health Promotion Center, Phayao, Thailand, for their cooperation and support throughout the data collection process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 6MWD | Six-Minute Walk Distance |

| 6MWT | Six-Minute Walk Test |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| FBG | Fasting Blood Glucose |

| FTSST | Five-Times-Sit-to-Stand Test |

| GPAQ | Global Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| HDL-C | High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| MET | Metabolic Equivalent of Task |

| MetS | Metabolic Syndrome |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| SpO2 | Peripheral Oxygen Saturation |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TG/HDL-C | Triglyceride-to-HDL Cholesterol Ratio |

| TUG | Timed-Up-and-Go Test |

| VO2max | Maximal Oxygen Uptake |

| WC | Waist Circumference |

References

- Ricardo, S.; Araujo, M.; Santos, L.; Romanzini, M.; Fernandes, R.; Turi-Lynch, B.; Codogno, J. Burden of metabolic syndrome on primary healthcare costs among older adults: A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2024, 142, e2023215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limon, V.M.; Lee, M.; Gonzalez, B.; Choh, A.C.; Czerwinski, S.A. The impact of metabolic syndrome on mental health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamooya, B.M.; Siame, L.; Muchaili, L.; Masenga, S.K.; Kirabo, A. Metabolic syndrome: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and current therapeutic approaches. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1661603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, A.; Delgado, V.; Valkovic, L.; Lima, J.A.C.; Nagel, E.; Ibanez, B.; Raman, B. Multiorgan Imaging for Interorgan Crosstalk in Cardiometabolic Diseases. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, 1454–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesa, C.M.; Zaha, D.C.; Bungău, S.G. Molecular Mechanisms of Metabolic Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, U.A.; Gerszten, R.E. Molecular Biomarkers for Cardiometabolic Disease: Risk Assessment in Young Individuals. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1663–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talayero, B.G.; Sacks, F.M. The role of triglycerides in atherosclerosis. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2011, 13, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Buring, J.E.; Cook, N.R.; Rifai, N. C-Reactive Protein, the Metabolic Syndrome, and Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Events. Circulation 2003, 107, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgado, F.; Valado, A.; Metello, J.; Pereira, L. Laboratory markers of metabolic syndrome. Explor. Cardiol. 2024, 2, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chait, A.; den Hartigh, L.J. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 522637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finelli, C.; Tarantino, G. What is the role of adiponectin in obesity related non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Poole, J.C.; Topel, M.L.; Bidulescu, A.; Morris, A.A.; Patel, R.S.; Binongo, J.G.; Dunbar, S.B.; Phillips, L.; Vaccarino, V.; et al. Subclinical Vascular Dysfunction Associated with Metabolic Syndrome in African Americans and Whites. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 4231–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kobori, T. Nutrient deficiency and physical inactivity in middle-aged adults with dynapenia and metabolic syndrome: Results from a nationwide survey. Nutr. Metab. 2025, 22, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Li, M.; Cao, J.; Zeng, L.; Jiang, C.; Lin, F. Association of metabolic syndrome severity with frailty progression among Chinese middle and old-aged adults: A longitudinal study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninx, B.W.; Nicklas, B.J.; Newman, A.B.; Harris, T.B.; Goodpaster, B.H.; Satterfield, S.; de Rekeneire, N.; Yaffe, K.; Pahor, M.; Kritchevsky, S.B. Metabolic syndrome and physical decline in older persons: Results from the Health, Aging And Body Composition Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2009, 64, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, D.L.; Tibana, R.A.; Teixeira, T.G.; Vieira, D.C.; Tarja, V.; Nascimento Dda, C.; Silva Ade, O.; Funghetto, S.S.; Coura, M.A.; Valduga, R.; et al. Elderly women with metabolic syndrome present higher cardiovascular risk and lower relative muscle strength. Einstein 2013, 11, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vieira, D.C.; Tibana, R.A.; Tajra, V.; Nascimento Dda, C.; de Farias, D.L.; Silva Ade, O.; Teixeira, T.G.; Fonseca, R.M.; de Oliveira, R.J.; Mendes, F.A.; et al. Decreased functional capacity and muscle strength in elderly women with metabolic syndrome. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Collins, K.H.; Herzog, W.; MacDonald, G.Z.; Reimer, R.A.; Rios, J.L.; Smith, I.C.; Zernicke, R.F.; Hart, D.A. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and musculoskeletal disease: Common inflammatory pathways suggest a central role for loss of muscle integrity. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harridge, S.D.R.; Lazarus, N.R. Physical activity, aging, and physiological function. Physiology 2017, 32, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautmans, I.; Lambert, M.; Mets, T. The six-minute walk test in community dwelling elderly: Influence of health status. BMC Geriatr. 2004, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasekaba, T.; Lee, A.L.; Naughton, M.T.; Williams, T.J.; Holland, A.E. The six-minute walk test: A useful metric for the cardiopulmonary patient. Intern. Med. J. 2009, 39, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, P.; McBurnie, M.A.; Bittner, V.; Tracy, R.; McNamara, R.; Arnold, A.; Newman, A. The 6-min Walk Test: A quick measure of functional status in elderly adults. Chest 2003, 123, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strath, S.; Swartz, A.; Parker, S.; Miller, N.; Cieslik, L. Walking and metabolic syndrome in older adults. J. Phys. Act. Health 2007, 4, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ubuane, P.; Animasahun, B.; Ajiboye, O.; Kayode-Awe, O.; Ajayi, O.; Njokanma, F. The historical evolution of the six-minute walk test as a measure of functional exercise capacity: A narrative review. J. Xiangya Med. 2018, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikli, R.E.; Jones, C.J. Development and validation of criterion-referenced clinically relevant fitness standards for maintaining physical independence in later years. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, K.Y.; Shin, D.W.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, S.H.; Yun, J.M.; Cho, B. Association of metabolic syndrome with mobility in the older adults: A Korean nationwide representative cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Grundy, S.M.; Cleeman, J.I.; Daniels, S.R.; Donato, K.A.; Eckel, R.H.; Franklin, B.A.; Gordon, D.J.; Krauss, R.M.; Savage, P.J.; Smith, S.C.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of the Metabolic Syndrome. Circulation 2005, 112, 2735–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaturapatporn, D.; Hathirat, S.; Manataweewat, B.; Dellow, A.C.; Leelaharattanarak, S.; Sirimothya, S.; Dellow, J.; Udomsubpayakul, U. Reliability and validity of a Thai version of the General Practice Assessment Questionnaire (GPAQ). J. Med. Assoc. Thai 2006, 89, 1491–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Bermejo, L.; Adsuar, J.C.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Barrios-Fernández, S.; Garcia-Gordillo, M.A.; Pérez-Gómez, J.; Carlos-Vivas, J. Test-retest reliability of five times sit to stand test (FTSST) in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biology 2021, 10, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, T.; Giladi, N.; Hausdorff, J.M. Properties of the ‘timed up and go’ test: More than meets the eye. Gerontology 2011, 57, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Pan, L.; Wang, D.; Liu, F.; Du, J.; Pa, L.; Wang, X.; Cui, Z.; Ren, X.; Wang, H.; et al. Normative values of hand grip strength in a large unselected Chinese population: Evidence from the China National Health Survey. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1312–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.J.; Rikli, R.E. Measuring functional. J. Act. Aging 2002, 1, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Ku, M.; Kiyoji, T.; Isobe, T.; Sakae, T.; Oh, S. Cardiorespiratory fitness is strongly linked to metabolic syndrome among physical fitness components: A retrospective cross-sectional study. J. Physiol. Anthr. 2020, 39, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babb, T.G. Obesity: Challenges to ventilatory control during exercise—A brief review. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2013, 189, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.; Egaña, M.; Baldi, J.C.; Lamberts, R.; Regensteiner, J.G. Cardiovascular control during exercise in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 654204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhynehart, A.; Dunlevy, C.; Hayes, K.; O’Connell, J.; O’Shea, D.; O’Malley, E. The Association of Physical Function Measures with Frailty, Falls History, and Metabolic Syndrome in a Population with Complex Obesity. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2021, 2, 716392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Z.; Wong, M.W.K.; Lim, J.Y.; Merchant, R.A. Frailty and Quality of Life in Older Adults with Metabolic Syndrome—Findings from the Healthy Older People Everyday (HOPE) Study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muollo, V.; D’Emanuele, S.; Ghiotto, L.; Rudi, D.; Schena, F.; Tarperi, C. Evaluating handgrip strength and functional tests as indicators of gait speed in older females. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1497546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M.; Klemetson, B.; Scott, D.; Murtishaw, A.S.; Navalta, J.W.; Kinney, J.W.; Landers, M.R. Effects of Fatigue on Balance in Individuals with Parkinson Disease: Influence of Medication and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Genotype. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2018, 42, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liao, J.; Liu, Y. Triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio was negatively associated with relative grip strength in older adults: A cross-sectional study of the NHANES database. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1222636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Liang, W.; Huang, H.; Huang, K.; Zeng, L.; Yang, L. Association of metabolic syndrome components and their combinations with functional disability among older adults in a longevity-associated ethnic minority region of Southwest China. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1635390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.J.; Hopman, M.T.; Padilla, J.; Laughlin, M.H.; Thijssen, D.H. Vascular adaptation to exercise in humans: Role of hemodynamic stimuli. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 495–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meex, R.C.R.; Blaak, E.E.; van Loon, L.J.C. Lipotoxicity plays a key role in the development of both insulin resistance and muscle atrophy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.V.; Distefano, G.; Lui, L.-Y.; Cawthon, P.M.; Kramer, P.; Sipula, I.J.; Bello, F.M.; Mau, T.; Jurczak, M.J.; Molina, A.J.; et al. Role of Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Mitochondrial Oxidative Capacity in Reduced Walk Speed of Older Adults with Diabetes. Diabetes 2024, 73, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itani, S.I.; Ruderman, N.B.; Schmieder, F.; Boden, G. Lipid-induced insulin resistance in human muscle is associated with changes in diacylglycerol, protein kinase C, and IkappaB-alpha. Diabetes 2002, 51, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolka, C.M. The Skeletal Muscle Microvasculature and Its Effects on Metabolism. In Microcirculation Revisited—From Molecules to Clinical Practice; Lenasi, H., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barazzoni, R.; Bischoff, S.; Boirie, Y.; Busetto, L.; Cederholm, T.; Dicker, D.; Toplak, H.; Van Gossum, A.; Yumuk, V.; Vettor, R. Sarcopenic obesity: Time to meet the challenge. Obes. Facts 2018, 11, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, J.; Connes, P.; Varlet-Marie, E. Alterations of blood rheology during and after exercise are both consequences and modifiers of body’s adaptation to muscular activity. Sci. Sports 2007, 22, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, T.V.; Prioletta, A.; Zuo, P.; Folli, F. Hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and its role in diabetes mellitus related cardiovascular diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 5695–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, K.; Mohapatra, L.; Wal, P.; Parveen, A.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, V. Deciphering the mechanisms and effects of hyperglycemia on skeletal muscle atrophy. Metab. Open 2024, 24, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvestan, J.; Kovacikova, Z.; Linduska, P.; Gonosova, Z.; Svoboda, Z. Contribution of lower limb muscle strength to walking, postural sway and functional performance in elderly women. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2021, 29, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, J.-J.; Sun, J.; Bao, Z.-J.; Wang, Z. Impact of lower limb muscle strength on walking function beyond aging and diabetes. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 030006052092882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.B.; Haggerty, C.L.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Nevitt, M.C.; Simonsick, E.M. Walking Performance and Cardiovascular Response: Associations with Age and Morbidity—The Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2003, 58, M715–M720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.; Collier, Z.; Reisman, D.S. Beyond steps per day: Other measures of real-world walking after stroke related to cardiovascular risk. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyner, M.J.; Casey, D.P. Regulation of increased blood flow (hyperemia) to muscles during exercise: A hierarchy of competing physiological needs. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 549–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endukuru, C.K.; Gaur, G.S.; Yerrabelli, D.; Sahoo, J.; Vairappan, B. Impaired baroreflex sensitivity and cardiac autonomic functions are associated with cardiovascular disease risk factors among patients with metabolic syndrome in a tertiary care teaching hospital of South-India. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 2043–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Galbreath, M.M.; Shibata, S.; Jarvis, S.S.; VanGundy, T.B.; Meier, R.L.; Vongpatanasin, W.; Levine, B.D.; Fu, Q. Relationship Between Sympathetic Baroreflex Sensitivity and Arterial Stiffness in Elderly Men and Women. Hypertension 2012, 59, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monahan, K.D. Effect of aging on baroreflex function in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007, 293, R3–R12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhofer, K.G.; Laufs, U. The diagnosis and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2019, 116, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Aggarwal, S.; Kumar, R.; Sharma, G. Association of atherosclerosis with dyslipidemia and co-morbid conditions: A descriptive study. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2015, 6, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonen, A.; Parolin, M.L.; Steinberg, G.R.; Calles-Escandon, J.; Tandon, N.N.; Glatz, J.F.; Luiken, J.J.; Heigenhauser, G.J.; Dyck, D.J. Triacylglycerol accumulation in human obesity and type 2 diabetes is associated with increased rates of skeletal muscle fatty acid transport and increased sarcolemmal FAT/CD36. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 1144–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.L. Arterial stiffness and hypertension. Clin. Hypertens. 2023, 29, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalwi, A.A.; Alharbi, A.A. Optimal procedure and characteristics in using five times sit to stand test among older adults: A systematic review. Medicine 2023, 102, e34160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, E.; Galvin, R.; Keogh, C.; Horgan, F.; Fahey, T. Is the Timed Up and Go test a useful predictor of risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta- analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.E.; Chun, H.; Kim, Y.-S.; Jung, H.-W.; Jang, I.-Y.; Cha, H.-M.; Son, K.Y.; Cho, B.; Kwon, I.S.; Yoon, J.L. Association between Timed Up and Go Test and subsequent functional dependency. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.