Abstract

Medical image segmentation acts as a foundational element of medical image analysis. Yet its accuracy is frequently limited by the scale fluctuations of anatomical targets and the intricate contextual traits inherent in medical images—including vaguely defined structural boundaries and irregular shape distributions. To tackle these constraints, we design a multi-scale feature attention network (MFA-Net), customized specifically for thyroid nodule, skin lesion, and breast lesion segmentation tasks. This network framework integrates three core components: a Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (Bi-FPN), a Slim-neck structure, and the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM). CBAM steers the model to prioritize boundary regions while filtering out irrelevant information, which in turn enhances segmentation precision. Bi-FPN facilitates more robust fusion of multi-scale features via iterative integration of top-down and bottom-up feature maps, supported by lateral and vertical connection pathways. The Slim-neck design is constructed to simplify the network’s architecture while effectively merging multi-scale representations of both target and background areas, thus enhancing the model’s overall performance. Validation across four public datasets covering thyroid ultrasound (TNUI-2021, TN-SCUI 2020), dermoscopy (ISIC 2016), and breast ultrasound (BUSI) shows that our method outperforms state-of-the-art segmentation approaches, achieving Dice similarity coefficients of 0.955, 0.971, 0.976, and 0.846, respectively. Additionally, the model maintains a compact parameter count of just 3.05 million and delivers an extremely fast inference latency of 1.9 milliseconds—metrics that significantly outperform those of current leading segmentation techniques. In summary, the proposed framework demonstrates strong performance in thyroid, skin, and breast lesion segmentation, delivering an optimal trade-off between high accuracy and computational efficiency.

1. Introduction

Medical image segmentation serves as a pivotal stage in medical image processing, bearing significant relevance for disease detection and analytical assessment. In modern clinical workflows, medical image diagnosis remains predominantly a manual task—an approach that is not only time-intensive but also prone to variability stemming from individual interpretive biases. Even among trained specialists, diagnostic assessments can exhibit subtle differences tied to professional experience and skill proficiency [1]. To address these drawbacks, computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) platforms have been developed [2]. These systems provide a powerful utility for the screening and categorization of medical images, with the goals of alleviating clinicians’ workloads, reducing reliance on human operators, and enhancing the accuracy of diagnostic outcomes. A key element in advancing CAD systems resides in developing algorithms for the automated segmentation of medical images. This segmentation process forms an essential component of the medical image processing workflow and carries considerable significance for both clinical diagnostic applications and research initiatives.

Automated medical image segmentation has been the subject of extensive academic exploration, encompassing techniques grounded in both conventional machine learning and contemporary deep learning architectures. Taking skin lesion segmentation as an example, traditional machine learning methods [3,4,5,6,7] are generally categorized into four main types: deformable model-centered strategies [6,8], support vector machine-based approaches [3], region-oriented analytical methods [4], and saliency detection-driven techniques [5]. For thyroid nodule segmentation tasks, traditional approaches that depend on manually designed features are typically grouped into region-based algorithms [9], active contour-based methods [10], and conventional machine learning systems [9]. These traditional techniques are characterized by a strong reliance on hand-engineered feature descriptors, often accompanied by complex preprocessing or postprocessing procedures—limitations that often result in subpar performance in complex clinical environments. By contrast, deep learning models can autonomously learn high-level semantic representations with little human involvement, and they have shown better performance than traditional methods, leading to their broad use in medical image segmentation. To exemplify related research: Gu et al. [11] presented CA-Net, a model that integrates multiple attention mechanisms to enhance the network’s sensitivity to the spatial, channel, and scale attributes of input data. To capture more abundant high-dimensional features while maintaining spatial and visual context, Bi et al. [12] developed BPAT-Unet, which integrates a boundary point supervision module (for managing contour information) and an adaptive multi-scale fusion module (to enhance local feature representation). Peng et al. [13] proposed MshNet for more precise and interpretable segmentation in biomedical images; this network employs an advanced downsampling block that merges max-pooling and average-pooling operations, minimizing information loss during downsampling while preserving key feature details. To enable effective interaction between high-frequency and low-frequency information, Wu et al. [14] created MFMSNet, which embeds MF-Trans into skip connections to allow the transfer of attention guidance from high-frequency to low-frequency components. Gao et al. [15] designed a lightweight context task encoding module capable of extracting task-specific information from reference image-label pairs to generate compact task embeddings that guide segmentation of query images. Wazir et al. [16] proposed the MCADS decoder architecture, which enhances segmentation accuracy by better integrating multi-scale features through depth-to-space upsampling and attention mechanisms. Mozaffari et al. [17] proposed the BowNet model, which combines the global prediction capability of fully convolutional encoder-decoder networks with the full-resolution feature extraction capability of dilated convolutions. Mozaffari et al. [18] introduced MTCHPSO, which integrates the global optimisation capability of multi-seed heterogeneous exploration with precise segmentation performance achieved by fusing Otsu and Kapur segmentation criteria.

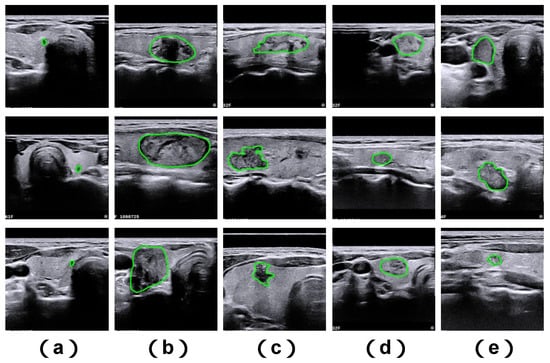

While current methodologies have enhanced performance in medical image analysis, segmenting medical images still poses notable challenges due to several key factors. First, the dimensions of clinically relevant objects within medical images may vary considerably (see Figure 1a,b). Second, ambiguous structural margins and complex geometries of segmentation targets often result in imprecise segmentation outcomes (see Figure 1c,d). Third, inadequate contrast levels make it difficult to differentiate between foreground anatomical targets and background image regions (see Figure 1e).

Figure 1.

Illustrative examples of challenging thyroid nodule cases sourced from the TNUI-2021 ultrasound dataset. Shown here are: (a) diminutive nodules, (b) large-sized nodules, (c) nodules with irregular structural shapes, (d) nodules characterized by indistinct boundary edges, and (e) nodules associated with poor image contrast. The ground truth segmentation boundary is marked using a green annotation.

To tackle the aforementioned challenges in medical image segmentation, we put forward a novel, high-efficiency multi-scale feature attention network (named MFA-Net) that generates high-caliber segmentation outputs. To better capture edge-related information, we design a hybrid attention mechanism: this component acquires task-tailored edge attention signals and reconstructs accurate boundary outlines. Next, a bidirectional feature pyramid network is embedded into the neck part of the network’s framework. This module incrementally merges top-down and bottom-up sampled feature maps via horizontal and vertical links, enabling efficient integration and exploitation of multi-scale feature representations. Finally, a slim-neck design approach is employed to adaptively merge multi-resolution features extracted from the backbone network; this lowers model complexity while maintaining segmentation performance, resulting in a lightweight network architecture. We assess the proposed MFA-Net using four publicly available biomedical image datasets, carrying out comprehensive comparisons with cutting-edge methods to verify its advantages. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- MFA-Net is a compact, lightweight model characterized by a small parameter size, fast inference speed, no need for pre-training, and high segmentation accuracy.

- We integrate a combined Convolutional Block Attention Module, which sequentially combines spatial and channel attention mechanisms. This improves the extraction of multi-scale contextual information and enhances the model’s capacity to capture detailed edge features in medical images.

- We utilize a simplified yet effective weighted bidirectional feature pyramid network. This module introduces learnable weighting factors to adaptively assess the significance of different input features, while repeatedly fusing multi-scale information in both top-down and bottom-up directions—ultimately further improving segmentation accuracy.

- The Slim-neck design paradigm is adopted to preserve inter-channel dependencies as much as possible under low computational overhead. This approach alleviates semantic degradation caused by spatial reduction and channel expansion in feature maps, thereby realizing a lightweight yet efficient network structure.

2. Related Work

2.1. Thyroid Nodule Segmentation

Thyroid nodule segmentation centers on pinpointing and outlining the structural regions of nodules in thyroid ultrasound images. Advancements in biomedical image processing have given rise to a suite of techniques that depend on manually engineered features for this objective. These approaches can be generally categorized into region-centric methods [8], level set-based solutions [9], and hybrid integrated systems [10]. For example, Chen et al. [9] put forward a voting-based multi-view ensemble learning framework. This system consolidates diagnostic outputs from a three-view thyroid ultrasound dataset, medical features derived via U-Net, and key features chosen using the mRMR (minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance) algorithm from statistical and texture feature sets. A more thorough overview of thyroid nodule segmentation methods is offered in [19].

In recent years, deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) have evolved quickly and gained widespread use in biomedical image analysis and clinical diagnosis—fueling the creation of diverse DCNN-based strategies for thyroid nodule segmentation. To demonstrate, Zhou et al. [20] built a tailored dual encoder-decoder network (H-Net) for this application: its left sub-network employs shallow CNN layers to capture fine-grained low-level details, while the right sub-network utilizes deep CNN layers to extract high-level semantic content. Nie et al. [21] proposed a novel N-shaped dense fully convolutional network (N-Net) for medical image segmentation, and additionally designed a Stackable Dilated Convolution (SDC) module to recover deep semantic information that may be discarded during bilinear upsampling. Wang et al. [22] introduced an iterative Edge Attention Network (EANet) for thyroid nodule segmentation, incorporating an Edge Attention Preserving (EAP) module to reduce noise and guide edge-focused processing toward boundary details. They also created a Multilevel Pairwise Regression (MPR) module to merge auxiliary edge and region signals, refining unclear structures through an iterative workflow that generates more distinct features and accurate saliency maps. Ali et al. [23] developed an encoder-decoder framework called CIL-Net, along with a Feature Improvement Block (FIB). This block uses multiple dilation rates to capture global contextual content, and applies BAM_CH channel attention and BAM_SP spatial attention to the output feature maps—maintaining inter-channel relationships and boosting feature representation quality. Tao et al. [24] proposed a Local and Context Adaptive Network (LCA-Net) for thyroid nodule segmentation, which merges locally extracted CNN features with global contextual information sourced from transformer architectures.

2.2. Skin Lesion Segmentation

Methods that utilize manually engineered features have been widely employed for skin lesion segmentation, with common strategies encompassing structured graph-based techniques [2] and machine learning-powered methods [3,4]. For example, Mirzaalian et al. [3] put forward a skin lesion segmentation approach that enhances color and contrast in dermoscopic images through a customized preprocessing pipeline. Patiniano [4] constructed a hyperpixel-focused segmentation framework for skin lesions. Ahn et al. [5] proposed a new skin lesion segmentation method that employs a saliency detection mechanism, combining sparse representation with background recognition. However, these methods—dependent on handcrafted features—often lack flexibility and struggle to generalize across varied application scenarios. To address these limitations, a large number of approaches based on deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) have been created. As an illustration, Wu et al. [25] developed a feature-adaptive transformer network (FAT-Net) using a conventional encoder-decoder architecture, adding a transformer sub-network to efficiently capture long-range feature associations and global contextual details. Qin et al. [26] introduced a cross-feature fusion network (CFF-Net) designed for skin lesion segmentation; its encoder comprises two parallel branches: a CNN pathway to extract fine-grained local features, and an MLP pathway to model overall spatial and channel correlations, thus enabling precise delineation of lesion boundaries. Feng et al. [27] put forward a skin lesion transducer network (SLT-Net) with a novel encoder-decoder structure for this task. The network uses CSwin-Unet as its encoder-decoder to capture long-range feature connections, and integrates a Multiscale Context Transformer (MCT) into skip connections to enhance cross-layer information exchange along the channel dimension.

2.3. Breast Lesion Segmentation

Recent advances in deep learning have driven the creation of several influential convolutional neural network architectures—such as U-Net [28], CE-Net [29], AttU-Net [30], and Unet++ [31]—which have been pivotal in advancing ultrasound breast segmentation. For example, Sun et al. [32] put forward a coarse-to-fine framework named CRSANet, which utilizes category-linked and spatial multi-scale contextual data to support thorough context understanding. Sun et al. [33] additionally proposed the Global-Local Fusion Network (GLFNet): a hybrid model built to mitigate the inherent constraints of CNNs and visual transformers. This network incorporates a global-local fusion block (GLFBlock) to merge global semantic content with local detailed features, thereby boosting segmentation accuracy. Zhang et al. [34] introduced a hierarchical attention-directed U-Net (HAU-Net) that includes a local-global converter module, composed of a local converter and a global converter. The local converter captures neighboring regional context, while the global converter models long-range feature associations; collectively, these elements enhance the network’s ability to segment breast lesions precisely. These integrated innovations have significantly improved both the accuracy and overall effectiveness of ultrasound breast segmentation approaches.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.1.1. Experimental Datasets

To assess the performance of MFA-Net in medical image segmentation, we trained the model using four publicly accessible datasets: TNUI-2021, TN-SCUI 2020, ISIC 2016, and BUSI. These datasets originate from different institutions and vary in composition and scale.

The TNUI-2021 dataset comprises 1381 thyroid nodule ultrasound scans, partitioned into 966 samples for training, 276 for validation, and 139 for testing. Every ultrasound image in this dataset has been manually labeled by a clinical expert, with nodule boundaries marked specifically for segmentation tasks.

The TN-SCUI 2020 dataset is derived from a competitive challenge focused on the segmentation and classification of thyroid nodules in ultrasound imagery [35]. It includes 7288 ultrasound images collected from subjects across diverse age groups, genders, and clinical settings, using a variety of ultrasound scanning devices. Each image is paired with detailed annotation of the targeted nodules. In our experimental setup, 5832 images were assigned to training, 728 to validation, and an additional 728 to testing.

The ISIC 2016 dataset is sourced from the public ISIC challenge, consisting of images gathered from multiple international clinical institutions using different imaging instruments [36]. Created for skin lesion segmentation tasks, it provides 900 training images and 379 validation images, each accompanied by a corresponding ground truth (GT) mask. The original image resolutions spanned a wide range (from 679 × 453 to 6748 × 4499), but all were standardized to a 256 × 256 pixel size. Lesion areas also varied substantially, accounting for 0.27% to 99.54% of the total image area.

The BUSI dataset consists of breast ultrasound images from 600 female patients aged 25 to 75 years [37]. In total, it includes 780 images: 133 normal (lesion-free) scans, 437 images of benign lesions, and 210 images of malignant lesions. Each image has an approximate resolution of 500 × 500 pixels. For the experiments in this study, only the images containing benign or malignant lesions were utilized: 517 samples were designated for training, 65 for validation, and 65 for testing.

3.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the segmentation capabilities of MFA-Net alongside comparative methods, we employed a suite of evaluation metrics in our experimental analyses, including precision, recall, Dice similarity coefficient, mean intersection over union (mIoU), inference latency, floating-point operations (FLOPs), and model parameter count. The specific calculation methodologies for these metrics are elaborated in the sections below:

In this context, TP, TN, FP, and FN denote the quantities of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. The effectiveness of the segmentation task was assessed using four key metrics: Precision, Recall, Dice similarity coefficient, and mean Intersection over Union (mIoU).

3.1.3. Implementation Details

All experimental implementations were carried out using the Python3.8.20 language and the PyTorch1.12.0 deep learning toolkit. The hardware setup included an 11th-gen Intel Core i5-11260H CPU (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (boasting a maximum clock speed of 2.60 GHz) paired with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050 (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) graphics card. To reduce computational load and memory consumption, input images were resampled to a resolution of 256 × 256 pixels. The AdamW optimization algorithm [38] was adopted, with an initial learning rate set to 0.001, and model training was conducted over 300 training cycles (epochs). A batch size of 32 was selected, as this configuration yielded the optimal utilization of GPU resources. By the completion of 300 epochs, all models had reached a stable convergent state, which allowed for a robust comparative evaluation of their performance.

3.1.4. Data Preprocessing

The present study employs a standardised data preprocessing workflow. The images are resized uniformly to a resolution of 256 × 256 pixels, and undergo a process of pixel value normalisation. During the training process, a parametric data augmentation pipeline is initiated. This includes the implementation of colour space perturbations, characterised by random hue shifts (±1.5% amplitude), saturation adjustments (±70% amplitude), and luminance transformations (±40% amplitude). Spatial geometric transformations encompass affine operations such as random horizontal flipping (50% probability), translation (maximum offset ±10%), and scaling (amplitude ±50%). Concurrently, mosaic enhancement is integrated to construct multi-scale contextual representations, which are progressively deactivated during the final 10 training epochs. The validation phase employs a deterministic preprocessing workflow, performing only image size standardisation and pixel value normalisation to eliminate the influence of random enhancements on evaluation outcomes. The processes of training and validation are achieved through distinct data processing pipelines configured within the framework. This ensures both the diversity of the training data and the accuracy and consistency of the evaluations.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. MFA-Net

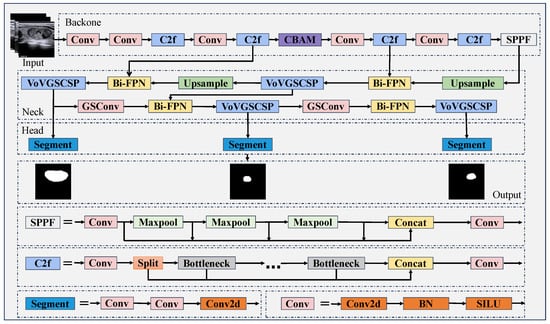

As depicted in Figure 2, the overall framework of our MFA-Net draws inspiration from YOLOv8, and it is structured into three core components: a backbone, a neck, and a head. In contrast to the base YOLOv8 architecture, MFA-Net incorporates a Convolutional Block Attention Module within the backbone—this modification enhances the model’s ability to capture fine-grained structural details and boundary cues in medical image data. Furthermore, the neck module employs a Bi-FPN, which enables efficient fusion of multi-scale features through coordinated top-down, bottom-up, and lateral connection pathways. A Slim-neck design is also embedded into the neck structure: this component optimizes feature extraction and integration processes while reducing the network’s architectural complexity, ultimately yielding a lightweight yet high-performance model. The specific design of each of these components will be elaborated upon in subsequent sections.

Figure 2.

MFA-Net structure diagram.

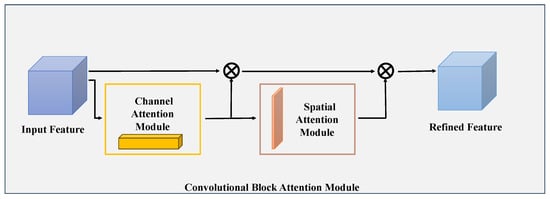

3.2.2. CBAM

Medical images are characterised by blurred boundaries, and conventional convolutional modules fail to adequately capture these details, rendering them vulnerable to interference from background noise. This results in segmentation outcomes characterised by smudged boundaries. In order to address the issue under consideration, the present study incorporates a convolutional block attention module into the backbone network with a view to enhancing boundary sensitivity. The channel attention module learns channel weights through global pooling and multilayer perceptrons, amplifying responses to boundary texture and edge gradient features while suppressing irrelevant background noise. The spatial attention module generates spatial weighting masks, focusing on lesion boundary regions and performing pixel-level weighting to compensate for the fixed receptive field limitation of conventional convolutions. The synergistic dual-channel attention mechanism enables the backbone network to output feature maps combining clear boundary details with accurate semantic attribution, thereby establishing a high-quality foundation for subsequent feature fusion in the neck network. The particulars of CBAM are delineated in the ensuing passages.

In deep learning, attention mechanisms enable models to focus on specific regions of an image (rather than processing the entire spatial domain) when executing a task. This capability supports the identification of key features relevant to segmentation while also enhancing the model’s ability to distinguish meaningful content from extraneous noise. Existing research highlights that the Spatial Attention Module (SAM) and Channel Attention Module (CAM) are two well-performing attention designs for feedforward neural networks (FFNs); both spatial and channel attention mechanisms have demonstrated strong proficiency in localizing target regions within feature maps. Numerous studies further indicate that a sequential application (channel attention first, followed by spatial attention) yields optimal learning performance—making this combined approach highly effective for target localization in feature maps.

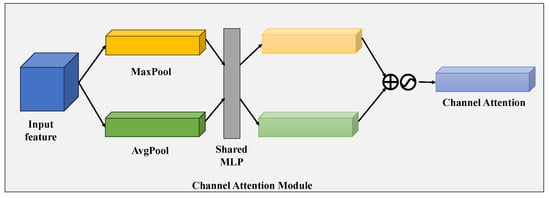

The Convolutional Block Attention Module is a representative attention-based framework that integrates a channel attention sub-module and a spatial attention sub-module [39]. To illustrate with the CAM of CBAM (as shown in Figure 3), we take an intermediate feature map as input: here, h and w represent the spatial height and width of each channel, respectively, and c denotes the total number of channels. First, average pooling and max pooling operations are applied to this feature map. The resulting pooled outputs are then fed into a shared multilayer perceptron (MLP), and a Sigmoid activation function is used to generate the final channel attention map. The specific mathematical formulation is provided in Equation (5).

Figure 3.

Diagram illustrating the channel attention sub-module, which leverages both the max-pooled and average-pooled results generated by a shared network architecture.

In this context, corresponds to the Sigmoid activation function, MLP stands for a shared multilayer perceptron, while and denote the feature map’s outputs after undergoing average pooling and max pooling operations, respectively.

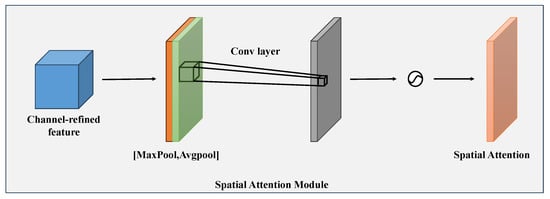

For the SAM integrated into CBAM (illustrated in Figure 4), the input is similarly an intermediate feature map . To begin, average-pooling and max-pooling operations are executed along the channel axis, yielding two dimensionally compressed feature vectors. These vectors are then concatenated in a channel-wise manner to form a 2D feature map. Next, a convolutional layer is employed to match the spatial structure of this map to the original input; this is followed by a Sigmoid activation function to produce a spatial attention map. Finally, this attention map is multiplied with the input feature map on an element-wise basis to generate the module’s output. The mathematical expression corresponding to this process is provided in Equation (6).

where denotes the convolution operation and the size of the convolution kernel is n × n.

Figure 4.

Visual schematic of the spatial attention sub-module. This module leverages two feature outputs generated via channel-wise pooling, which are subsequently fed into a convolutional layer for further processing.

The CBAM module integrates channel and spatial attention in a mutually reinforcing fashion. As illustrated in Figure 5, the input feature map is first subjected to element-wise multiplication with the channel attention map , yielding a channel-optimized feature map . This intermediate map is then multiplied element-wise by the spatial attention map , resulting in the final refined output . By capturing feature information across both channel and spatial domains, this dual-attention framework strengthens the model’s capacity to detect edge-associated details. The mathematical formulations corresponding to these operations are provided in Equations (7) and (8).

Figure 5.

High-level diagram of the CBAM framework. This module consists of two sequentially arranged sub-components: a channel attention sub-module and a spatial attention sub-module. Through these two sub-components, CBAM dynamically optimizes the intermediate feature maps corresponding to each convolutional block in a task-adaptive manner.

In this context, refers to the input feature map, while ⊗ signifies the operation of element-wise multiplication. denotes the weight parameters derived from the channel attention mechanism, and represents the feature map that has been optimized via channel attention processing. Correspondingly, stands for the weight parameters generated by the spatial attention mechanism, and is the end result after spatial attention refinement—which also functions as the comprehensive output of the CBAM module.

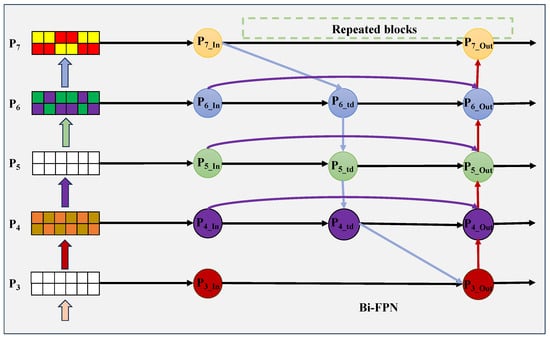

3.2.3. Bi-FPN

The management of clinical medical images poses a considerable challenge due to the considerable variations in size that are observed. The conventional Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) utilises a unidirectional fixed-weight feature fusion approach, which is incapable of balancing the contribution of features across different image scales. Consequently, it is unable to resolve issues such as the submergence of minute lesions’ superficial details or the incomplete segmentation of large lesions’ deep contours due to missing fine features. The Bi-FPN bidirectional weighted fusion mechanism has been developed to address this challenge, and has thus been incorporated into the cervical network. The model establishes a ’top-down + bottom-up’ bidirectional cross-scale connection, thereby enabling the bidirectional transmission and mutual refinement of both deep semantic features and shallow detail features. Concurrently, learnable weight parameters are configured for each fusion branch, thereby enabling the model to adaptively allocate weights to features across different scales during training. This approach involves the enhancement of the weighting of shallow, high-resolution features for small lesions, with the objective of preserving detail, while simultaneously amplifying the weighting of deep semantic features for large lesions, with the aim of refining their contours. This mechanism ensures that the feature requirements of lesions of all sizes are effectively met, thereby preventing missed detections and accuracy degradation caused by size variations. A comprehensive introduction to Bi-FPN is provided hereafter.

To enhance the model’s capacity to integrate contextual information and multi-scale feature representations, MFA-Net adopts a Bi-FPN as its feature fusion backbone. PANet fuses features across all scales using uniform weighting, thereby neglecting the unique contributions of different resolution levels. In contrast, Bi-FPN implements a lightweight normalized weighted fusion mechanism. This method learns a set of weight coefficients corresponding to each input feature path, enabling the network to dynamically assess the significance of features from various scales during the fusion process [40]. The mathematical expression describing this weighted feature fusion strategy is provided in Equation (9):

Here, O represents the fused feature output, is the feature from the i-th input branch, denotes the learnable weight of that branch, sums the weights of all input branches, and ensures numerical stability.

Moreover, Bi-FPN reduces the growth of extra parameters through cross-scale connections and an advanced bidirectional fusion mechanism. As shown in Figure 6, Bi-FPN extends PANet by keeping the bottom-up flow and adding same-level skip connections between output and input nodes. This promotes cross-scale feature exchange and fusion with lower computational cost while strengthening representational capacity. Therefore, the Bi-FPN used in this work offers a more efficient feature fusion scheme. Additionally, MFA-Net integrates low-level feature maps containing rich spatial and geometric details into the fusion process, which helps improve the segmentation precision of small structures.

Figure 6.

Bi-FPN structure for multi-scale feature fusion.

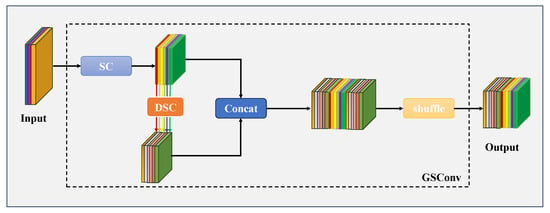

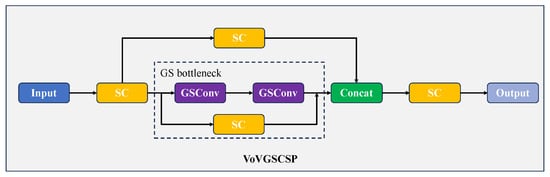

3.2.4. Slim-Neck

The irregular shapes and low contrast of medical images can introduce redundant background information, which can interfere with feature extraction. The conventional neck networks’ convolutional modules are subject to certain limitations. Sparse channel convolution (SC) preserves feature correlations; however, it incurs high computational complexity and sluggish inference speeds. Conversely, dense channel convolution (DSC) simplifies computation but severes channel associations, resulting in semantic information loss and inadequate adaptation to low-contrast image feature confusion and irregular nodule edge detection demands. In order to address this issue, the present study employs the Slim-neck paradigm, which is centred on GSConv and VoVGSCSP, in combination with Bi-FPN to construct a neck network. GSConv extracts and fuses features through a ’SC+DSC’ dual-channel approach, achieving complementary feature enhancement via concatenation and reshuffling. This approach preserves channel correlations while reducing computational load, enhancing lesion-background discrimination and mitigating low-contrast noise interference. VoVGSCSP is a development of GSConv, leading to the establishment of an iterative residual architecture. It has been demonstrated that multiple rounds of GS bottleneck feature extraction enhance irregular edge detection, while residual branches preserve original spatial information to prevent detail loss, ultimately generating feature maps rich in both semantic and spatial detail. The neck layer employs a feature transformation that maximises channel dimensions while minimising width and height dimensions to compress redundant information. The substitution of conventional Conv modules with GSConv has been demonstrated to result in model lightweighting and enhanced segmentation accuracy, thereby effectively addressing the challenges posed by feature extraction in scenarios where low contrast and irregular shapes are prevalent. The following essay provides a comprehensive overview of the subject known as the slim-neck.

The Slim-neck is a lightweight network architecture built mainly with GSConv and VoVGSCSP components, where GSConv acts as its central functional module [41]. Its main objective is to reduce the computational inefficiencies of CNNs during the inference stage. In a typical CNN backbone, spatial information is gradually shifted into the channel dimension as the input image is processed. However, the combined steps of spatial compression and channel expansion often result in partial loss of semantic content. Channel-dense convolution (SC) maximizes the preservation of inter-channel associations, while channel-sparse convolution (DSC) completely breaks these links. GSConv achieves a balanced middle ground: it cuts down computational costs while still maintaining the continuity of channel connections. The computational complexity (measured in FLOPs) of these convolution variants is defined mathematically in Equations (10)–(12).

In this notation, W and H correspond to the width and height of the resulting feature map after convolution. and denote the dimensions of the convolution kernels, stands for the count of input channels (which aligns with the channel number of the input feature map), and refers to the count of output channels.

Specifically, the GSConv module first applies a standard convolution to input feature maps to generate one feature set, then leverages depthwise separable convolution (DSC) to create a second feature set. These two groups are concatenated and subsequently subjected to channel shuffling, enabling information from standard and DSC convolutions to intermix. This facilitates a more uniform distribution of feature information across channels. The structure is shown in Figure 7. Typically, features are forwarded to the neck, where channel dimensions are expanded to a maximum while spatial dimensions are compressed—this reduces redundant information. In our work, traditional CNN blocks in the neck are replaced with GSConv, which streamlines the network architecture and boosts segmentation performance.

Figure 7.

GSConv Framework Design. The segment labeled “SC” (highlighted in blue) corresponds to a conventional 2D convolutional layer, which is sequentially followed by batch normalization and an activation function. The segment denoted “DSC” (displayed in orange) represents a depthwise separable 2D convolutional layer, and this component is similarly followed by batch normalization and an activation function in sequence.

As illustrated in Figure 8, the VoVGSCSP module realizes iterative feature integration based on GS bottlenecks, incorporating GSConv into its design. The initial processing step involves a convolution (Conv) operation, followed by feature extraction executed via a sequence of consecutive GS bottleneck modules. Simultaneously, residual features (corresponding to a single convolution operation) are extracted from a separate branch. Afterward, the two groups of output feature maps are fused and processed through an additional convolution operation, producing the final output (comprising channels total). This module achieves a favorable balance between segmentation accuracy and inference speed, delivering robust performance while cutting down on both computational overhead and structural complexity. At its core, the GS bottleneck stacks GSConv layers to enhance feature processing capabilities and strengthen the model’s learning capacity; the VoVGSCSP module, by contrast, uses diverse structural designs to improve feature utilization efficiency and overall network performance. Together, these components embody the Slim-neck design philosophy: minimizing computational load and inference delay without compromising segmentation quality. Additionally, their modular structure allows for flexible architectural adjustments to suit the requirements of specific tasks.

Figure 8.

Structure of VoVGSCSP.

3.2.5. Loss Function Design

This study employs a unified binary cross-entropy loss with logits (BCEWithLogitsLoss) as the core segmentation loss function for three medical image segmentation tasks: thyroid nodules (two datasets), dermatological conditions, and breast cancer. Its fundamental mathematical expression is presented in Equation (13):

In this context, N signifies the total number of cropped pixels within the target bounding box, while ranges from 0 to 1, representing the ground truth mask label for the i-th pixel (where 1 indicates the lesion area and 0 indicates the background area). denotes the model’s output prediction value (logits) prior to sigmoid activation, where denotes the sigmoid activation function. This function maps logits to the interval [0,1] in order to represent the probability that a pixel belongs to the region of the lesion.

In order to counterbalance the loss contributions from lesions of varying sizes and to prevent large lesions from dominating gradient updates, this study introduces a bounding box area normalisation strategy to the base loss function. The final calculation of the segmentation loss is given by Equation (14):

In the formula, M denotes the number of positive sample anchor points within a batch; represents the area of the kth lesion target box; signifies the pixel-wise BCEWithLogits loss within the kth target box; and denotes the mean calculation of pixel losses within the target box.

The fundamental rationale for the selection of BCEWithLogitsLoss in this study is as follows: Firstly, all three types of medical images share the common characteristics of blurred lesion boundaries and low distinguishability from surrounding tissues. It is evident that BCEWithLogitsLoss possesses the property of per-pixel loss calculation, thus enabling precise constraints on the classification results of each pixel as either lesion or background. This approach has been demonstrated to enhance the accuracy of pixel-level prediction in regions characterised by blurred boundaries, thereby preventing the occurrence of ‘blurring’ or ‘discontinuities’ at lesion edges in segmentation results. Secondly, in image segmentation tasks, the application of sigmoid activation to model-output logits prior to the calculation of loss frequently results in the phenomenon of vanishing gradients. This is due to the convergence of values towards 0 or 1. By contrast, BCEWithLogitsLoss directly calculates loss on logits, thereby circumventing this issue. When employed in conjunction with the optimisation strategy of ‘bounding box cropping + area normalisation’, it serves to further suppress background noise interference on gradients, thereby enhancing the stability of segmentation model training. Thirdly, none of the three segmentation tasks demonstrate extreme category imbalance (no orders-of-magnitude difference in lesion area proportion), thus eliminating the necessity for loss functions such as Dice Loss, which are designed for highly imbalanced scenarios. Furthermore, BCEWithLogitsLoss demonstrates high computational efficiency, facilitating collaboration with lightweight network architectures to satisfy the inference speed requirements for real-time clinical diagnosis.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Thyroid Nodule Segmentation Experiment

Table 1 benchmarks MFA-Net against a selection of state-of-the-art image segmentation approaches, including U-Net [28], CE-Net [29], AttU-Net [30], U-Net++ [31], Dense-Unet [42], H-Net [20], N-Net [21], CRSA-Net [32], EA-Net [22], Swin-Unet [43] and TransUnet [44]. Segmentation performance is assessed using four key indicators: Dice similarity coefficient, mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), precision, and recall. Detailed quantitative outcomes are presented in Table 1. As observed, MFA-Net delivers competitive performance in terms of Dice, mIoU, precision, and recall when evaluated on the TNUI-2021 and TN-SCUI 2020 datasets.

Table 1.

Quantitative performance benchmarking of various methods on the TNUI-2021 and TN-SCUI 2020 datasets.

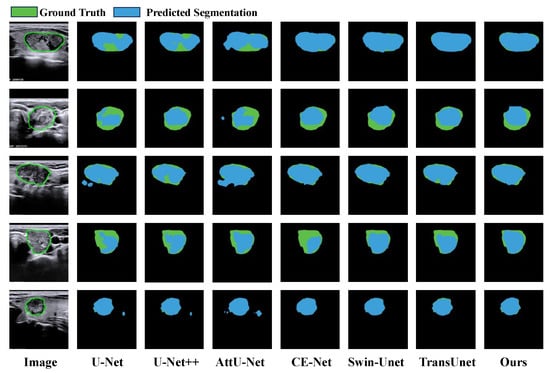

The quantitative segmentation results on the TNUI-2021 dataset are summarized in Table 1. Our proposed MFA-Net obtains the best scores across all metrics—Dice, mIoU, Precision, and Recall—on this dataset. Compared with H-Net [20], MFA-Net raises the Dice coefficient by 3.4% (from 0.921 to 0.955), mIoU by 3.9% (from 0.875 to 0.914), Precision by 9.0% (from 0.875 to 0.965), and Recall by a similar margin (from 0.852 to 0.946). Moreover, qualitative segmentation examples are shown in Figure 9. Key observations include the following: (1) U-Net [28] tends to under-segment, as seen in column 2 (rows 1, 2, 4) where predictions are smaller than true targets. (2) U-Net++ [31] shows mild under-segmentation in column 3 (rows 1, 2, 4). (3) AttU-Net [30] yields inconsistent results, over-segmenting in column 4 (rows 1–3, 5) while under-segmenting in the same column (rows 1, 2, 4). (4) CE-Net [29] suffers from severe under-segmentation, illustrated in column 5 (rows 2, 4) where predictions are markedly smaller than ground truth. (5) Swin-Unet [43] exhibits undersegmentation, as demonstrated in rows 2–4 of the sixth column, where the segmented regions are smaller than the actual annotated areas. (6) TransUNet [44] displays similar undersegmentation flaws, with its segmentation results failing to fully encompass the boundaries of the actual lesions. Corresponding visualisation results are shown for samples in rows 2–4 of the seventh column. (7) In contrast, MFA-Net provides more accurate thyroid nodule segmentation, aligning better with ground-truth boundaries. This visual analysis further confirms the effectiveness of MFA-Net for thyroid nodule segmentation.

Figure 9.

Qualitative result comparison on the TNUI-2021 dataset. Regions colored blue and green correspond to model predictions and the ground truth, respectively. The leftmost column shows the original input image; the subsequent five columns exhibit sample segmentation results from U-Net, CE-Net, AttU-Net, U-Net++, Swin-Unet, TransUnet and our proposed MFA-Net.

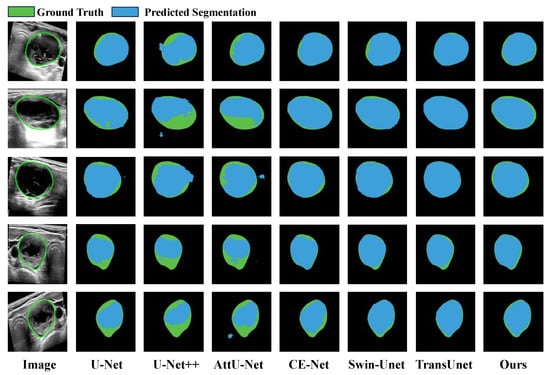

Our MFA-Net was also tested on the TN-SCUI 2020 dataset. A quantitative comparison of all competing methods is provided in Table 1, where MFA-Net attains the highest scores in Dice, mIoU, Recall and Precision among all approaches. Relative to CRSA-Net [32], MFA-Net improves Dice by 9.5% (0.876 → 0.971), mIoU by 13.0% (0.814 → 0.944), Precision by 11.3% (0.868 → 0.981), and Recall by 8.9% (0.873 → 0.962). Furthermore, seven typical visual examples are displayed in Figure 10 for qualitative comparison. The visualizations reveal that both U-Net++ [31] and AttU-Net [30] are unable to segment edge regions accurately, frequently resulting in over-segmentation because they cannot capture stable edge features. By contrast, MFA-Net segments edge areas more faithfully, a benefit largely credited to its incorporated CBAM attention mechanism. Overall, the visual evidence confirms that MFA-Net produces more accurate and dependable segmentation results.

Figure 10.

Qualitative comparison of segmentation outputs on the TN-SCUI 2020 dataset. Blue and green regions correspond to model-predicted results and the reference ground truth, respectively. The leftmost column presents the original input image; the five subsequent columns display sample segmentation results generated by U-Net, CE-Net, AttU-Net, U-Net++, Swin-Unet, TransUnet and our proposed MFA-Net.

In terms of efficiency, we compared MFA-Net with other competing methods on the TN-SCUI 2020 dataset based on inference time, floating-point operations (FLOPs), and parameter count, as summarized in Table 2. The table shows that MFA-Net has the fewest parameters among all compared models—just 23% of U-Net’s parameter size—delivering state-of-the-art performance with substantially reduced parameterization. During testing, MFA-Net also achieved competitive efficiency, with an inference time of 1.9 ms per image and 11.2 G FLOPs. These outcomes demonstrate that MFA-Net offers lower model complexity and faster inference relative to several alternative segmentation approaches.

Table 2.

On the TN-SCUI 2020 dataset, a quantitative comparison is conducted regarding inference time, FLOPs, and parameter counts between our proposed MFA-Net and other methods.

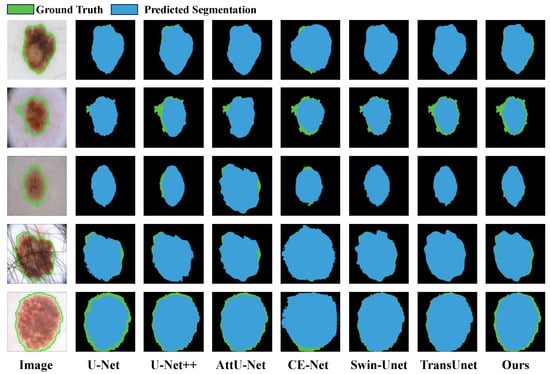

4.2. Skin Lesion Segmentation Experiment

We conducted a quantitative benchmark of MFA-Net against cutting-edge approaches for skin lesion segmentation, such as U-Net [28], CE-Net [29], AttU-Net [30], U-Net++ [31], FAT-Net [25], CFF-Net [26], Swin-Unet [43] and TransUnet [44]. The corresponding evaluation results are presented in Table 3. On the ISIC 2016 dataset, MFA-Net reaches scores of 0.976 (Dice), 0.953 (mIoU), 0.970 (precision), and 0.981 (recall), indicating higher accuracy than the other approaches. Relative to CE-Net [29], MFA-Net improves the Dice coefficient by 3.3% (0.943 → 0.976) and mIoU by 6.0% (0.893 → 0.953), while precision and recall increase by about 3.8% (0.932 → 0.970) and a similar margin (0.943 → 0.981), respectively. Visual examples are provided in Figure 11. We observe the following: (1) U-Net [28] tends to under-segment, producing regions smaller than the ground truth, as seen in column 2, rows 2, 4, 5; (2) U-Net++ [31] also under-segments, shown in column 3, rows 2–5; (3) AttU-Net [30] yields mild under-segmentation in column 4, rows 2–5; (4) CE-Net [29] exhibits over-segmentation in column 5, rows 4–5, and slight over-segmentation in rows 1–3 of the same column, with predictions often smaller than ground truth; (5) Swin-Unet [43] exhibits dual issues of under-segmentation and over-segmentation: under-segmentation manifests as predicted regions smaller than actual annotated regions, exemplified in rows 2 and 5 of the sixth column; over-segmentation occurs when predicted regions exceed true lesion boundaries, as seen in rows 3 and 4 of the sixth column; (6) TransUNet [44] similarly exhibits segmentation bias, with undersegmentation observed in row 2 of the seventh column and oversegmentation in row 4 of the same column; (7) In contrast, MFA-Net delivers more accurate segmentations even for images with ambiguous boundaries or irregular shapes, as illustrated by the five sample outputs in the figure.

Table 3.

Quantitative performance benchmarking of our proposed MFA-Net against multiple state-of-the-art methods on the ISIC 2016 dataset.

Figure 11.

Qualitative result comparison on the ISIC 2016 dataset. Blue and green regions correspond to model-predicted outputs and the reference ground truth, respectively. The leftmost column shows the original input image; the subsequent five columns exhibit sample segmentation results produced by U-Net, CE-Net, AttU-Net, U-Net++, Swin-Unet, TransUnet and our proposed MFA-Net.

4.3. Breast Nodule Segmentation Experiment

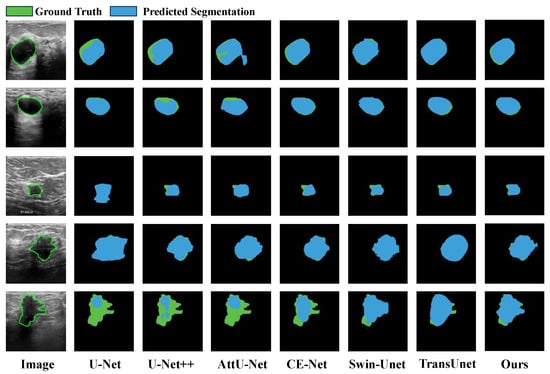

To evaluate MFA-Net’s performance in breast lesion segmentation, we conducted a quantitative benchmark against several cutting-edge segmentation methods—including U-Net [28], CE-Net [29], AttU-Net [30], U-Net++ [31], CRSA-Net [32], GLF-Net [33], Swin-Unet [43] and TransUnet [44]—using the public BUSI dataset. The evaluation results are presented in Table 4. Among all compared models, MFA-Net attains the top scores in Dice (0.846) and Precision (0.918). As illustrated in rows 3–5 of Figure 12, the other six networks face challenges when processing irregularly shaped lesions: they generate both over-segmented and under-segmented results, as they lack the ability to effectively capture multi-scale feature information. By contrast, MFA-Net (integrated with a Bi-FPN module) segments such irregular lesion shapes with higher accuracy. The qualitative segmentation results further verify that our approach produces more refined and accurate segmentation outputs.

Table 4.

Quantitative performance benchmarking of our proposed MFA-Net against multiple state-of-the-art methods on the BUSI dataset.

Figure 12.

Qualitative result comparison on the BUSI dataset. Blue and green regions correspond to model predictions and the reference ground truth, respectively. The leftmost column shows the original input image; the five subsequent columns exhibit sample segmentation outputs generated by U-Net, CE-Net, AttU-Net, U-Net++, Swin-Unet, TransUnet and our proposed MFA-Net.

4.4. Robustness Analysis

Table 5 presents the quantitative performance of the proposed MFA-Net across four public medical image datasets. All metrics are reported in mean ± standard deviation format to ensure statistical integrity. Results demonstrate that the model achieves outstanding segmentation performance across diverse datasets, exhibiting exceptional stability and generalisation capability. Specifically, on the ISIC 2016 dataset, MFA-Net delivers the most prominent performance, achieving Dice similarity coefficients, mIoU, precision, and recall of 0.981 ± 0.004, 0.963 ± 0.007, 0.981 ± 0.009, and 0.981 ± 0.004 respectively. The extremely low standard deviation (≤0.009) indicates negligible performance fluctuation across five independent replicate experiments, demonstrating excellent robustness. On the TN-SCUI 2020 dataset, the model similarly delivered highly competitive results, achieving a Dice coefficient of 0.966 ± 0.003 and mIoU of 0.935 ± 0.005, further validating its effectiveness on high-quality medical image data. Even on the relatively complex BUSI dataset, the model maintained solid performance, achieving a Dice coefficient of 0.853 ± 0.007 and precision of 0.897 ± 0.027. Although the standard deviation for some metrics was slightly higher compared to other datasets, it remained within a low range (≤0.027), demonstrating the model’s ability to sustain stable performance on challenging datasets. In summary, the model’s consistently strong performance across four datasets fully demonstrates that the proposed MFA-Net possesses robust adaptability and generalisation capabilities for medical image segmentation tasks, laying a solid foundation for its potential clinical applications.

Table 5.

Quantitative Performance of MFA-Net on Various Medical Image Datasets (Mean ± Standard Deviation).

4.5. Ablation Experiments

We performed ablation experiments on the TNUI-2021 dataset using MFA-Net, with results presented in Table 6. YOLOv8 acted as the baseline model. First, we added the CBAM to the baseline (denoted as Baseline + CBAM). This improved both mIoU and Recall by 0.5% on TNUI-2021, as CBAM assists the network in focusing more effectively on lesion boundaries. The complex mixing of foreground and background with similar contrast often complicates edge information extraction; CBAM resolves this by fusing spatial and channel attention, producing clearer edge features. Next, we constructed Baseline + CBAM + Slim-neck by incorporating both the CBAM and Slim-neck modules. Compared to Baseline + CBAM, this configuration increased mIoU by 1.2% and Recall by 1.1%, while cutting parameters by 5% relative to the original baseline—validating the Slim-neck’s contribution to model lightweighting. Finally, MFA-Net combines CBAM, Slim-neck, and Bi-FPN with the baseline. When compared to the baseline, MFA-Net improves mIoU by 2.9%, Precision by 1.7%, Dice by 1.6%, and Recall by 1.6% on TNUI-2021. Integrating these modules strengthens the interaction between low-level and high-level CNN features, enhances localization performance, and boosts the utilization efficiency of spatial and channel feature maps. Overall, the ablation study findings confirm that each component of MFA-Net makes a significant contribution to improving the performance of medical image segmentation tasks.

Table 6.

Ablation experiments were carried out on the TNUI-2021 dataset.

5. Conclusions

This work introduces a novel, high-efficiency multi-scale feature attention network (MFA-Net) tailored for precise, robust segmentation of biomedical images—especially those with ambiguous boundaries or irregular morphologies. The framework integrates three core components: the Convolutional Block Attention Module, a Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (Bi-FPN), and a Slim-neck structure. In the backbone, CBAM utilizes both channel and spatial attention mechanisms to refine focus on edge regions, thus enhancing the extraction of local and global feature representations. In the neck, Bi-FPN boosts cross-scale connectivity by removing single-input nodes, adding additional connections between input and output nodes at the same level, and treating each bidirectional path as a reusable feature-network layer. This enables more seamless multi-scale information interaction and fusion. The Slim-neck, constructed based on GSConv, maintains inter-channel correlations while cutting down computational costs; it mitigates semantic information loss induced by spatial compression and channel expansion, resulting in a lightweight network architecture. Moreover, the cross-stage VoVGSCSP module adopts single-step aggregation to optimize feature fusion across distinct network stages. Comprehensive experiments on four public biomedical image datasets demonstrate that MFA-Net achieves state-of-the-art performance: Dice coefficients of 95.5% on TNUI-2021, 97.1% on TN-SCUI 2020, 97.6% on ISIC 2016, and 84.6% on BUSI. Notably, it secures the top Dice score (95.5%) on the TNUI-2021 dataset. Both qualitative and quantitative comparisons validate that MFA-Net outperforms existing leading methods. As a dependable biomedical image analysis tool for computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems, MFA-Net can provide valuable insights for subsequent surgical planning, aiding clinicians in the diagnosis and treatment of conditions like thyroid, skin, and breast cancers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T. and J.Z.; methodology, H.T. and J.Z.; software, H.T.; validation, H.T., M.L. and S.L.; formal analysis, H.T. and H.J.; investigation, H.T.; resources, H.J.; data curation, H.T.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.; writing—review and editing, H.T., M.L. and J.Z.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, H.J. and J.Z.; project administration, H.J. and J.Z.; funding acquisition, H.J. and J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the School Fund of Hebei Normal University (No. L2023T06).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it only used publicly available medical image datasets, which do not contain identifiable patient information.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study only used publicly available medical image datasets, which do not require informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are publicly available. The TNUI-2021, TN-SCUI 2020, ISIC 2016, and BUSI datasets can be accessed at the following links: TNUI-2021: https://github.com/zxg3017/TNUI-2021- (accessed on 9 January 2026); TN-SCUI 2020: https://tn-scui2020.grand-challenge.org/Dataset/ (accessed on 9 January 2026); ISIC 2016: https://challenge.isic-archive.com/data/#2016 (accessed on 9 January 2026); BUSI: https://scholar.cu.edu.eg/?q=afahmy/pages/dataset (accessed on 9 January 2026).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Park, H.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.G.; Ro, Y.M.; Shin, D.; Lee, S.R.; Kim, S.H.; Kong, M. Endometrium segmentation on transvaginal ultrasound image using key-point discriminator. Med. Phys. 2019, 46, 3974–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, K. Computer-aided diagnosis in medical imaging: Historical review, current status and future potential. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2007, 31, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaalian, H.; Lee, T.K.; Hamarneh, G. Skin lesion tracking using structured graphical models. Med. Image Anal. 2016, 27, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patiño, D.; Avendaño, J.; Branch, J.W. Automatic skin lesion segmentation on dermoscopic images by the means of superpixel merging. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Granada, Spain, 16 September 2018; pp. 728–736. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, E.; Kim, J.; Bi, L.; Kumar, A.; Li, C.; Fulham, M.; Feng, D.D. Saliency-based lesion segmentation via background detection in dermoscopic images. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2017, 21, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, H.; Cao, C.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, D. RVLSM: Robust variational level set method for image segmentation with intensity inhomogeneity and high noise. Inf. Sci. 2022, 596, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Z.; Xie, H.; Feng, T.; Lu, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, R. Leukocyte image segmentation based on adaptive histogram thresholding and contour detection. Curr. Bioinform. 2020, 15, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Multi-modal medical image segmentation based on vector-valued active contour models. Inf. Sci. 2020, 513, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, X.; Jin, J.; Shen, Y. Computer aided diagnosis of thyroid nodules based on the devised small-datasets multi-view ensemble learning. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 67, 101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, P.; Illanes, A.; Arens, C.; Hansen, C.; Friebe, M. Active contours extension and similarity indicators for improved 3D segmentation of thyroid ultrasound images. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2017: Imaging Informatics for Healthcare, Research, and Applications, Orlando, FL, USA, 11–16 February 2017; Volume 10138, p. 1013803. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, R.; Wang, G.; Song, T.; Huang, R.; Aertsen, M.; Deprest, J.; Ourselin, S.; Vercauteren, T.; Zhang, S. CA-Net: Comprehensive attention convolutional neural networks for explainable medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 40, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Cai, C.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, G.; Shu, H.; Ni, X. BPAT-UNet: Boundary preserving assembled transformer UNet for ultrasound thyroid nodule segmentation. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 238, 107614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yu, D.; Guo, Y. MShNet: Multi-scale feature combined with h-network for medical image segmentation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 79, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Lu, X.; Yao, Z.; Ma, Y. MFMSNet: A Multi-frequency and Multi-scale Interactive CNN-Transformer Hybrid Network for breast ultrasound image segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 177, 108616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhou, M.; Metaxas, D.N. Show and Segment: Universal Medical Image Segmentation via In-Context Learning. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 20830–20840. [Google Scholar]

- Wazir, S.; Kim, D. Rethinking Decoder Design: Improving Biomarker Segmentation Using Depth-to-Space Restoration and Residual Linear Attention. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 30861–30871. [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffari, M.H.; Lee, W.S. Encoder-decoder CNN models for automatic tracking of tongue contours in real-time ultrasound data. Methods 2020, 179, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffari, M.H.; Lee, W.S. Convergent heterogeneous particle swarm optimisation algorithm for multilevel image thresholding segmentation. IET Image Process. 2017, 11, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Gao, J.; Zhao, D. A review of the application of deep learning in medical image classification and segmentation. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Nie, X.; Li, Z.; Lin, X.; Xue, E.; Wang, L.; Lan, J.; Chen, G.; Du, M.; Tong, T. H-Net: A dual-decoder enhanced FCNN for automated biomedical image diagnosis. Inf. Sci. 2022, 613, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Zhou, X.; Tong, T.; Lin, X.; Wang, L.; Zheng, H.; Li, J.; Xue, E.; Chen, S.; Zheng, M.; et al. N-Net: A novel dense fully convolutional neural network for thyroid nodule segmentation. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 872601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Huang, S.; Yang, D. EANet: Iterative edge attention network for medical image segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 127, 108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Wang, M.; Xie, J. CIL-Net: Densely Connected Context Information Learning Network for Boosting Thyroid Nodule Segmentation Using Ultrasound Images. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 1176–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Dang, H.; Shi, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Ren, S. Local and context-attention adaptive LCA-Net for thyroid nodule segmentation in ultrasound images. Sensors 2022, 22, 5984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chen, S.; Chen, G.; Wang, W.; Lei, B.; Wen, Z. FAT-Net: Feature adaptive transformers for automated skin lesion segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 76, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Zheng, B.; Zeng, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Genovese, A.; Piuri, V.; Scotti, F. Dynamically aggregating MLPs and CNNs for skin lesion segmentation with geometry regularization. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 238, 107601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Ren, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. SLT-Net: A codec network for skin lesion segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 148, 105942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing And Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Z.; Cheng, J.; Fu, H.; Zhou, K.; Hao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Gao, S.; Liu, J. Ce-net: Context encoder network for 2d medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2019, 38, 2281–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support: 4th International Workshop, DLMIA 2018, and 8th International Workshop, ML-CDS 2018, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2018, Granada, Spain, 20 September 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Fu, C.; Xu, S.; Wen, Y.; Ma, T. CRSANet: Class Representations Self-Attention network for the segmentation of thyroid nodules. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 91, 105917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Fu, C.; Xu, S.; Wen, Y.; Ma, T. GLFNet: Global-local fusion network for the segmentation in ultrasound images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 171, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lian, J.; Yi, Z.; Wu, R.; Lu, X.; Ma, P.; Ma, Y. HAU-Net: Hybrid CNN-transformer for breast ultrasound image segmentation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 87, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jia, X.; Ni, D.; Noble, A.; Huang, R.; Tan, T.; Van, M. Thyroid nodule segmentation and classification in ultrasound images. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Lima, Peru, 4–8 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman, D.; Codella, N.C.F.; Celebi, E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.; Mishra, N.; Halpern, A. Skin Lesion Analysis toward Melanoma Detection: A Challenge at the International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) 2016, hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC), 2016. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.01397. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dhabyani, W.; Gomaa, M.; Khaled, H.; Fahmy, A. Dataset of breast ultrasound images. Data Brief 2020, 28, 104863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loshchilov, I. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, Q. Slim-neck by GSConv: A lightweight-design for real-time detector architectures. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2024, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, H.; Qi, X.; Dou, Q.; Fu, C.W.; Heng, P.A. H-DenseUNet: Hybrid densely connected UNet for liver and tumor segmentation from CT volumes. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 37, 2663–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.