Abstract

Modern cryptographic systems increasingly depend on certified hardware modules to guarantee trustworthy key management, tamper resistance, and secure execution across Internet of Things (IoT), embedded, and cloud infrastructures. Although numerous FIPS 140-certified platforms exist, prior studies typically evaluate these solutions in isolation, offering limited insight into their cross-domain suitability and practical deployment trade-offs. This work addresses this gap by proposing a unified, multi-criteria evaluation framework aligned with the FIPS 140 standard family (including both FIPS 140-2 and FIPS 140-3), replacing the earlier formulation that assumed an exclusive FIPS 140-3 evaluation model. The framework systematically compares secure elements (SEs), Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs), embedded Systems-on-Chip (SoCs) with dedicated security coprocessors, enterprise-grade Hardware Security Modules (HSMs), and cloud-based trusted execution environments. It integrates certification analysis, performance normalization, physical-security assessment, integration complexity, and total cost of ownership. Validation is performed using verified CMVP certification records and harmonized performance benchmarks derived from publicly available FIPS datasets. The results reveal pronounced architectural trade-offs: lightweight SEs offer cost-efficient protection for large-scale IoT deployments, while enterprise HSMs and cloud enclaves provide high throughput and Level 3 assurance at the expense of increased operational and integration complexity. Quantitative comparison further shows that secure elements reduce active power consumption by approximately 80–85% compared to TPM 2.0 modules (<20 mW vs. 100–150 mW) but typically require 2–3× higher firmware-integration effort due to middleware dependencies. Likewise, SE050-based architectures deliver roughly 5× higher cryptographic throughput than TPMs (∼500 ops/s vs. ∼100 ops/s), whereas enterprise HSMs outperform all embedded platforms by two orders of magnitude (>10 000 ops/s). Because the evaluated platforms span both FIPS 140-2 and FIPS 140-3 certifications, the comparative analysis interprets their security guarantees in terms of requirements shared across the FIPS 140 standard family, rather than attributing all properties to FIPS 140-3 alone. No single architecture emerges as universally optimal; rather, platform suitability depends on the desired balance between assurance level, scalability, performance, and deployment constraints. The findings offer actionable guidance for engineers and system architects selecting FIPS-validated hardware for secure and compliant digital infrastructures.

1. Introduction

In our hyper-connected world, the volume of digital data doubles approximately every two years, and the global number of connected devices has exceeded 15 billion, dramatically expanding the potential attack surface of modern infrastructures. As the Internet of Things (IoT) continues to integrate into critical systems–from industry to healthcare–cybersecurity has become one of the fundamental pillars of sustainable digital management and organizational competitiveness. Comprehensive analyses of IoT and cyber–physical systems (CPS) architectures highlight that the heterogeneous and layered nature of modern IoT infrastructures inherently complicates their defense against advanced cyber threats. Any unauthorized access, breach, or data corruption may lead to severe financial and reputational losses, as repeatedly demonstrated in both enterprise and industrial environments. Recent studies further emphasize that IoT networks remain particularly exposed due to heterogeneous communication protocols, distributed control systems, and inconsistent firmware security practices, which collectively complicate the adoption of unified cryptographic protection mechanisms [1].

Beyond software-level vulnerabilities, modern systems face increasingly sophisticated hardware-centric attack surfaces. Post-silicon analyses reveal a growing spectrum of side-channel, fault-injection, and microarchitectural attacks that can compromise even certified or theoretically robust security modules. These risks have been underscored in recent high-impact research, including demonstrations of practical leakage from commercial security tokens [2], power-side-channel detection challenges [3], deep-learning-assisted nonprofiled attacks [4], and the formalization of hardware fault adversary models that influence the trustworthiness of embedded cryptographic components [5]. Collectively, these findings reinforce that secure hardware design cannot rely solely on certification and must be contextualized within realistic adversarial environments.

Cryptography remains the cornerstone of data protection in distributed and interconnected systems, providing confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity for information exchanged across untrusted networks. In this context, cryptographic keys function as digital safes—central assets whose compromise may expose entire infrastructures. Thus, their secure storage and lifecycle management are paramount. The most reliable approach is to store keys within physically protected environments such as Hardware Security Modules (HSMs), Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs), or Secure Elements (SEs), all of which comply with formal certification standards, including FIPS 140-3 [6,7]. These standards define rigorous requirements for cryptographic module validation, encompassing physical tamper resistance, key isolation, deterministic self-tests, and systematic assurance of operational integrity [8]. As the cryptographic landscape shifts toward post-quantum algorithms, validation methodologies must also evolve; recent work has highlighted the growing challenges of testing and verifying post-quantum mechanisms in accordance with emerging NIST standards [9].

Although certified solutions exist, the prior literature typically examines them in isolation—focusing either on enterprise-grade HSMs or on low-cost embedded security modules [10,11]. Industrial implementations of cryptographic accelerators and secure sensing systems demonstrate promising performance–energy trade-offs for real-time protection in IoT-based infrastructures [12]. However, only a limited number of comparative studies provide a unified, cross-domain evaluation that spans IoT, embedded, cloud, and hybrid trusted-computing environments under a consistent evaluation framework aligned with the FIPS 140 standard family. This gap persists despite the increasing need for harmonized trust architectures that bridge hardware-anchored security with distributed cloud-based attestation, workload isolation, and runtime integrity verification.

Recent advances highlight the evolving nature of trusted-computing infrastructures across the entire deployment pipeline. At the supply-chain and provisioning stages, hardware-rooted frameworks such as PIT-Cerberus demonstrate the feasibility of preventing device tampering during transit through coordinated BIOS/BMC measurements and secure-boot extensions [13]. At the edge, trusted chips have been employed to ensure integrity and isolation of containerized workloads, supporting secure orchestration models for IoT edge computing nodes [14]. In cloud environments, virtual TPM architectures (e.g., SvTPM) leverage SGX enclaves to establish robust trust chains, provide rollback-resistant NVRAM abstractions, and extend TPM semantics to multi-tenant and virtualized workloads [15]. Complementing these capabilities, continuous runtime verification frameworks enforce zero-trust postures by integrating TPM-backed platform measurements with adaptive intrusion detection and cloud-scale policy evaluation [16].

Trusted execution environments (TEEs) have gained prominence as an intermediary trust layer between hardware-rooted mechanisms and distributed application stacks. TEEs have been applied to protect smart-contract-based IoT data trading through rollback-resistant state validation [17], to support robust and privacy-preserving blockchain consensus mechanisms [18], and to enable customizable, hardware-reconfigurable isolation environments on FPGA-SoC platforms [19]. These studies illustrate the growing complexity and diversity of trusted computing approaches, each addressing different portions of the hardware–edge–cloud trust continuum.

This study addresses the resulting design-space fragmentation by presenting a systematic comparison of hardware architectures designed to implement cryptographic functions certified under FIPS 140. The originality of this work lies in the use of a multi-criteria evaluation framework that jointly considers certification assurance, computational performance, physical protection, integration complexity, and total cost of ownership. By applying this framework to distinct hardware families—including enterprise HSMs, embedded TPMs, and lightweight SEs—this paper offers actionable insights for decision-makers and engineers selecting appropriate cryptographic platforms for IoT, industrial, and cloud-based systems. This research builds upon earlier efforts in secure sensing, trusted execution environments, and cryptographic acceleration for industrial IoT [8,12], contributing to a more unified understanding of hardware-based cybersecurity design.

Recent studies further demonstrate that chaotic-map-based cryptographic algorithms have evolved into a structured and rapidly advancing research area. Newly introduced multi-dimensional and hyperchaotic systems exhibit strong diffusion–confusion characteristics, high entropy, and validated NIST-SP800 randomness performance, as shown by coupling-enhanced cubic hyperchaotic maps designed for secure multi-image encryption [20]. Parallel developments in multi-media protection integrate dual-watermark mechanisms with chaotic-map encryption to enhance robustness against statistical and differential attacks [21]. Additionally, recent systematic evaluations of classical chaotic maps—including Henon, tent, and logistic models—provide rigorous statistical assessments (NPCR, UACI, PSNR, independence analysis) and highlight their applicability within lightweight cryptographic pipelines for embedded and IoT systems [22].

Parallel research on memristive chaotic systems has advanced rapidly as well. Recent works demonstrate memristive dynamical models exhibiting extreme multi-stability, high sensitivity to initial conditions, and strong entropy characteristics, which have been successfully applied to image-encryption pipelines and lightweight security primitives for embedded devices. Complementary circuit-level studies show that memristive chaotic oscillators can be reliably implemented in hardware, offering reproducible nonlinear behavior and practical feasibility for neuromorphic security architectures. Furthermore, multi-dimensional memristive chaotic controllers have been deployed in secure communication systems, demonstrating the applicability of these emerging architectures beyond simulation-based research.

Collectively, these results provide a substantially broader and more persuasive foundation for chaotic and memristive cryptographic research than previously reflected in the introduction. They reinforce the relevance of these emerging paradigms while clarifying why, despite their demonstrated potential, they remain unsuitable for certification-driven environments such as FIPS 140.

2. Overview

The protection of cryptographic assets has become a fundamental requirement in modern digital infrastructures, where the confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity of data rely heavily on validated and tamper-resistant hardware components. In this context, the Federal Information Processing Standard 140 (FIPS 140) plays a pivotal role. Published by the United States National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and adopted by the Canadian Communications Security Establishment, this standard defines rigorous security requirements for cryptographic modules, specialized hardware or software components that execute encryption, key generation, and secure key management [6,10,11].

FIPS-compliant modules undergo comprehensive testing through the Cryptographic Module Validation Program (CMVP), which verifies algorithm correctness, tamper resistance, and operational reliability. This certification ensures that devices meet internationally recognized assurance criteria for cryptographic systems [23]. The methodological setup draws inspiration from existing frameworks for multi-vendor interoperability and third-party sensor discovery in IoT ecosystems, ensuring that hardware and communication layers reflect realistic deployment conditions. Recent studies further emphasize that FIPS validation increasingly intersects with emerging cryptographic paradigms. In particular, post-quantum mechanisms require novel testing methodologies for algorithm correctness, entropy robustness, and implementation soundness, as demonstrated by PQC validation frameworks proposed in [9].

The relevance of standardized hardware protection has grown exponentially with the proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) and cyber–physical systems, where heterogeneous nodes—from microcontrollers to cloud platforms—demand unified trust anchors [24,25]. FIPS 140 offers this unified foundation by defining incremental assurance levels and standardized self-test procedures that ensure interoperability and reliability across domains. However, recent security research shows that hardware trust anchors must now address threats originating not only during operation but also throughout the device lifecycle. Supply-chain-oriented tamper-protection frameworks, such as PIT-Cerberus [13], highlight the need for cryptographic modules to integrate secure boot, provenance verification, and BMC/BIOS measurement processes aligned with FIPS zeroization and tamper-response requirements.

2.1. Algorithmic Outline of an FIPS 140-2/3-Compliant Hardware Solution

To illustrate the operational mechanisms of certified cryptographic modules, this subsection outlines the functional steps of a Hardware Security Module (HSM) compliant with FIPS 140-2/3. The following pseudocode examples use Python 3.12-style syntax for clarity.

2.1.1. Module Initialization (Power-On Self-Tests)

When powered on, the HSM automatically executes Known Answer Tests (KATs) for all approved algorithms (AES, RSA, HMAC, etc.). Any failure causes an immediate transition into an FIPS error state, halting all operations. Example code is at Listing 1.

| Listing 1. Halting all operations if any failure occurs during KAT. |

| if not KAT_passed: log(“FIPS self-test failure”) HSM.enter_error_state() halt_system() |

2.1.2. User Authentication

Before performing any sensitive operation, the HSM enforces authentication. At Level 2, role-based authentication is required; at Level 3, identity-based credentials are mandatory. Repeated authentication failures trigger full key zeroization (Listing 2).

| Listing 2. Full key zeroization. |

| if not authenticate(user_credentials): error_counter += 1 if error_counter >= 3: HSM.zeroize() # Immediate key destruction (FIPS) halt_system() deny_access() |

2.1.3. Access and Role Management

Only authorized roles can perform specific actions. A Security Officer manages configurations, while a Crypto Officer executes encryption or key operations. All events are logged for auditing and compliance (Listing 3).

| Listing 3. Logging of events. |

| if user.role not in allowed_roles: log_unauthorized_access(user.role) deny_access() else: execute_operation(user.request) |

2.1.4. Key Generation and Secure Storage

When generating a new cryptographic key, the HSM uses a deterministic random bit generator (DRBG) compliant with NIST SP 800-90A, seeded by hardware entropy (Listing 4).

| Listing 4. Generating a key using hardware entropy. |

| seed = HSM.read_hardware_entropy() # Verified entropy source AES_key = DRBG.generate(seed) # SP800-90A approved DRBG HSM.store_secure(AES_key, encrypt_with = “MasterKey”) |

Private keys are always encrypted by an internal Master Key and stored in protected nonvolatile memory. They never leave the module in plaintext form.

2.1.5. Data Encryption, Signing, and Integrity Verification

FIPS-approved algorithms are used exclusively for encryption, signing, and integrity validation (Listing 5).

| Listing 5. Encryption, signing, and integrity validation. |

| ciphertext = HSM.encrypt(plaintext, key_id, alg = “AES”) signature = HSM.sign(hash(plaintext), key_id) tag = HSM.compute_HMAC(ciphertext, key_id) |

These operations guarantee confidentiality, authenticity, and integrity according to FIPS 140 validation rules.

2.1.6. Zeroization and Tamper Response

The HSM immediately erases all keys if tampering or repeated authentication failure is detected (Listing 6).

| Listing 6. Failure detection and erasing keys. |

| if tamper_detected or error_counter >= 3: HSM.zeroize() |

This mechanism ensures that sensitive data cannot be recovered after a physical or logical breach. Recent fault-injection and side-channel research demonstrates that modern adversaries increasingly target physical leakage channels to bypass these protection mechanisms. Studies such as EUCLEAK [2], ADC-based SCA sensors [3], and neural-network-driven nonprofiled attacks [4] illustrate why FIPS modules must implement strong tamper-detection pathways validated under realistic adversarial conditions.

2.1.7. Continuous Compliance Verification

During operation, the HSM continuously ensures that only FIPS-approved algorithms are used and logs all events for traceability. Regular self-tests and audit logs guarantee continuous certification compliance [8,12]. Cloud-native environments extend this requirement further. Virtual TPM architectures such as SvTPM [15] and runtime-based zero-trust enforcement frameworks [16] demonstrate the necessity of continuous integrity verification even when cryptographic functionality migrates from hardware appliances to enclave-backed virtualized components.

2.2. Methodology for Comparative Evaluation

The second part of this section details the methodology used to compare secure hardware architectures supporting FIPS 140-certified operations. The analysis aimed to provide both quantitative and qualitative insights into certified hardware security.

2.2.1. Evaluation Criteria

A balanced set of criteria was established to reflect both technical and operational perspectives. Technical metrics include throughput, latency, entropy quality, and certification level, while operational factors cover cost, power consumption, and integration complexity [23,26]. This ensures a fair assessment of performance and deployability. Additionally, trusted execution environments (TEEs) represent an increasingly relevant dimension for comparative evaluation. Recent studies demonstrate their applicability for blockchain consistency [18], rollback-resistant IoT data trading [17], and runtime-reconfigurable FPGA–SoC isolation [19]. These developments broaden the design space of what constitutes an “FIPS-adjacent” trusted computing stack, motivating their inclusion in the comparative methodology.

2.2.2. Data Collection and Normalization

Data were gathered from vendor datasheets, CMVP certification records, Common Criteria listings, and the peer-reviewed literature [11]. Where quantitative data were missing, proxy values derived from comparable implementations were used. Qualitative labels such as “low latency” or “medium cost” were normalized to ordinal numerical scales to facilitate comparison.

2.2.3. Analytical Framework

All normalized data were consolidated into a comparison matrix summarizing certification level, performance, power efficiency, and total cost of ownership (TCO). Scatter and radar plots were generated to identify trade-offs and Pareto frontiers between compliance assurance and system efficiency. Cluster analysis further distinguished IoT-class secure modules from enterprise-grade Hardware Security Module (HSM)s.

2.2.4. Limitations

This study acknowledges inherent limitations in comparative security evaluations. Performance varies with algorithm selection and test methodology, cost depends on market factors, and power usage is workload-dependent. To mitigate uncertainty, multiple independent data sources were cross-validated, emphasizing relative rather than absolute results [8]. Furthermore, post-silicon threat analyses reveal that evaluation frameworks must consider subtle hardware-level risks—from fault-injection adversaries [5] to emerging post-silicon tamper-resilience techniques [27]. As such, performance and certification values should be interpreted alongside realistic hardware attack models.

2.2.5. Synthesis

The algorithmic outline and methodology presented above jointly form the foundation of this study. They establish a transparent and reproducible framework for analyzing cryptographic hardware certified under FIPS 140-2/3, integrating operational rigor with practical deployability across embedded, industrial, and cloud environments [10,28].

3. Methods

The methodology adopted in this work was designed to ensure a comprehensive, structured, and reproducible comparison of hardware architectures supporting FIPS 140 certified cryptographic operations. Unlike descriptive reviews that merely summarize device characteristics, the proposed framework emphasizes traceability, interoperability, and consistency with international standards such as NIST SP 800-90A/B, ISO/IEC 19790, and the FIPS 140 specification series (FIPS 140-2 and FIPS 140-3) [6]. The methodological design builds upon prior work exploring the layered nature of IoT security architectures and aims to provide a unified model for assessing both hardware-based and software-assisted cryptographic modules. This approach was chosen because fragmented evaluations, while abundant in the literature, often fail to compare heterogeneous systems—ranging from low-power secure elements to enterprise-grade HSMs—under consistent evaluation metrics [10,24]. Moreover, recent studies on supply-chain tamper protection, virtual TPMs, and zero-trust cloud monitoring frameworks highlight that modern trust anchors span physical devices, firmware, and virtualized execution environments, which motivates a methodology explicitly capable of benchmarking both hardware-rooted and enclave-assisted cryptographic modules [13,15,16].

Recent research further highlights that cross-layer security integration across web-enabled and cloud-based IoT ecosystems requires a unified assessment methodology to ensure end-to-end trust. Accordingly, the central objective of this section is to define an evaluation framework capable of benchmarking the security, efficiency, and scalability of cryptographic components across diverse deployment environments.

3.1. Definition of Evaluation Criteria

Following multi-criteria decision-making principles established in industrial system evaluation research [26], this study defines a structured set of evaluation criteria encompassing both technical and operational dimensions. Technical factors include throughput, latency, entropy quality, and certification assurance, while operational factors involve cost, power consumption, maintainability, and integration complexity. Each metric reflects a critical determinant of system feasibility, aligning with empirical security evaluations in embedded contexts [1,29]. In addition, the criteria were designed to remain compatible with emerging validation practices for post-quantum cryptography, where standardized test batteries and correctness checks are being formalized for lattice-based KEMs and other PQC primitives [9]. Although the present work focuses on FIPS 140-validated classical cryptographic modules, the underlying methodology is thus positioned to accommodate PQC-capable hardware once standardized validation profiles become available.

The inclusion of explainable and transparent evaluation criteria follows emerging AI-driven frameworks for security assessment in 6G-IoT environments, ensuring interpretability of decisions in automated cryptographic systems. Performance metrics were derived from cryptographic workloads such as AES-GCM, RSA-2048, and ECDSA verification cycles, normalized per clock frequency. Certification level was represented as a categorical variable, with FIPS 140-3 levels (1–4) denoting progressive hardware isolation and tamper evidence [6]. The physical resilience of implementations—particularly for FPGA- and ASIC-based accelerators—was assessed using fault-attack analysis principles as described in [8]. Entropy-source evaluation followed NIST SP 800-90A/B/C guidelines [10,11], ensuring that hardware RNGs and DRBG subsystems satisfied minimum unpredictability requirements.

However, certification alone does not guarantee operational robustness. This study does not independently verify whether the evaluated DRBG implementations perform NIST-mandated continuous health tests during runtime (e.g., repetition count tests and adaptive proportion tests). Thus, the entropy-source assessment reflects certification claims rather than empirical validation. Similarly, side-channel resistance is not re-measured experimentally; instead, the presence of documented countermeasures and certified fault-detection or tamper-response mechanisms is interpreted in light of recent side-channel and leakage studies, including power analysis on commercial tokens, on-chip SCA-detection sensors, and deep-learning-assisted nonprofiled attacks [2,3,4].

Operational dimensions were extended to include safety-critical deployments such as IoT-enabled fire monitoring and healthcare telemetry systems, where both latency and reliability directly affect human safety. Integration complexity was adapted from interoperability frameworks proposed in [30], emphasizing interactions between firmware-layer controls and middleware security services. Total cost of ownership (TCO) was derived from hardware–software integration models [11,25], while sustainability considerations followed energy-aware security optimization research [23]. For edge-computing scenarios, additional attention was given to trusted-chip-based container protection and rollback-safe execution environments, which increasingly shape how hardware trust anchors are consumed by higher-layer services [14,17,19].

The choice of a weighted, multi-criteria scoring model is consistent with recent IoT platform and security evaluation studies that combine technical and operational indicators into a unified decision framework [26]. At the same time, the focus on cryptographic primitives and hardware roots of trust aligns with current work on deterministic cryptographic systems, lightweight cryptography for power-constrained microcontrollers, and unidirectional secure communication architectures in IoT deployments. These studies motivate the need for a structured comparison of FIPS 140-certified modules that goes beyond purely protocol-level or software-only analyses.

To ensure consistent cross-platform comparison, all evaluation dimensions in this study are expressed using a normalized five-point ordinal scale, where 1 denotes minimal capability or highest integration effort and 5 denotes maximal capability or lowest integration effort. This unified scoring model provides a reproducible basis for evaluating both technical and operational criteria.

Recent surveys underline that IoT security must be evaluated holistically across system layers, communication protocols, and deployment contexts rather than at the level of isolated hardware primitives [24]. Additional studies highlight that secure architectures for industrial and safety-critical applications require coordinated analysis of hardware trust anchors, firmware controls, and operational constraints [25]. Meanwhile, cloud- and blockchain-backed trust frameworks increasingly shape the security guarantees of modern IoT infrastructures. Trusted execution environments and enclave-based platforms, such as those used for IoT data trading and blockchain ledgers [17,18], further blur the boundary between pure hardware modules and virtualized roots of trust, which is reflected in the inclusion of both hardware and cloud-backed platforms in the comparative feature matrix.

These findings motivate the multi-dimensional evaluation model adopted in this study, which assesses FIPS 140-certified hardware roots of trust not only by their cryptographic capabilities but also by their system-level integration trade-offs.

Each metric was normalized to a five-point ordinal scale (1 = poor, 5 = excellent), and relative importance weights were assigned as follows: performance (25%), certification assurance (25%), integration complexity (20%), cost (15%), and energy efficiency (15%). This distribution reflects the balance between strong security guarantees and practical deployability observed across recent IoT and embedded security studies [28,31].

To eliminate ambiguity in Table 1, the compliance score used in this study is now formally defined. Each platform is evaluated against four mandatory FIPS 140-related requirement categories: secure boot or authenticated initialization, physical tamper protection, certified entropy source (RNG/DRBG), and authenticated key storage or a validated cryptographic boundary. Let k denote the number of categories satisfied by a given platform. The base compliance score is computed as:

Platforms that provide hardware-rooted tamper resistance or a certified HSM boundary receive a documented +0.5 adjustment:

This transformation converts categorical FIPS compliance properties into a normalized five-point ordinal score consistent with the evaluation methodology used throughout Section 3. Chaotic and hyperchaotic image-encryption schemes, including recent multi-image and dual-watermark constructions [20,21,22], are explicitly excluded from this scoring model. While they represent an active and promising research area, they lack standardized FIPS 140 validation paths and therefore cannot be meaningfully compared within the same compliance-centric framework.

Table 1.

Estimated implementation cost and compliance level for Selected Platforms.

A crucial clarification concerns cloud-based trusted execution environments. AWS Nitro Enclaves and similar technologies do not constitute FIPS-certified cryptographic modules; their FIPS compliance derives entirely from backend services such as AWS KMS or CloudHSM, which provide the actual validated cryptographic boundary. Accordingly, these platforms were evaluated separately from hardware-rooted trust anchors to avoid misclassifying enclave isolation mechanisms as certified cryptographic protections.

3.2. Feature Matrix and Platform Comparison

To ground the analysis in concrete implementations, a comparative feature matrix was developed. It evaluates representative FIPS-certified platforms—from constrained IoT secure elements to enterprise and cloud-level modules—against key security mechanisms mandated by FIPS 140, including Secure Boot, tamper detection, secure storage, and Random Number Generator (RNG) certification.

Explanation of the Feature Matrix (Table 2).

Table 2.

Feature matrix comparing key FIPS-certified platforms.

ATECC608B/C: Provides firmware validation for secure startup and SP 800-90B-compliant RNG. Although lacking dedicated tamper sensors, it ensures key protection through secure storage and is certified under FIPS 140-3.

TPM 2.0 (Infineon SLB9672): Implements secure boot through Platform Configuration Registers (PCRs) and Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) integration. The module achieves FIPS 140-2 Level 3 tamper resistance, includes a dedicated cryptographic coprocessor, and employs an NDRNG validated under FIPS 140-2 standards.

NXP i.MX 8X + SE050: Combines a high-performance microcontroller with an FIPS 140-2 Level 3-certified secure element. The architecture supports Cryptographic Acceleration and Assurance Module(CAAM)-based secure boot, integrated HSM key management, and certified entropy generation, making it suitable for embedded industrial and automotive use.

AWS Nitro Enclaves: Implements logical isolation via the hypervisor rather than physical tamper detection. It relies on AWS KMS HSM instances for secure storage and cryptographic operations, with FIPS 140-3-certified RNG and key management at the cloud layer.

This matrix captures how hardware-level assurance (tamper detection, secure storage) contrasts with virtualized security approaches (attestation, isolation) across deployment tiers. The distinction is particularly important in light of recent SCA and fault-injection research on commercial tokens and embedded devices, which shows that physical exposure can undermine even formally validated modules if deployment conditions are not aligned with their assumed adversary models [2,5].

Integration complexity varies across platforms and is influenced by practical factors such as SDK maturity, the depth of middleware layers, and the amount of configuration required to expose cryptographic functions. For example, TPM 2.0 integration typically requires only minimal glue code to interface with PKCS#11 stacks, whereas SE050 deployments involve additional middleware layers for secure-channel establishment, APDU handling, and key-management abstractions, as documented in the Plug & Trust integration guide from NXP [32]. These observations reflect structural analysis of publicly available integration middleware rather than precise line-count measurements.

Cloud-based platforms such as AWS Nitro require no hardware integration but impose additional configuration overhead in IAM policies and KMS bindings. These metrics provide an objective basis for comparing integration complexity across heterogeneous platforms.

3.3. Data Collection and Validation

Data were collected from a combination of authoritative and peer-reviewed sources. Primary data originated from the NIST Cryptographic Module Validation Program (CMVP) and Common Criteria (CC) registries, ensuring traceability and reproducibility. Secondary data were compiled from empirical measurements, vendor specifications, and academic studies [1,10,12]. The dataset included both hardware modules (e.g., TPMs, SEs, HSMs) and software-certified cryptographic libraries (e.g., OpenSSL, wolfCrypt).

Performance indicators such as RSA signing throughput, AES – GCM latency, and RNG entropy were cross-validated against benchmark datasets published in [7,29]. Certification claims were verified through NIST CMVP listings and validated FIPS security policies. Qualitative parameters such as secure boot mechanisms, tamper response, and zeroization were examined with reference to embedded device security analyses [1,28]. Energy-consumption characteristics of secure elements and TPMs were corroborated by comparative analyses of hardware random-number generators in IoT devices [7]. Where available, additional qualitative information on side-channel countermeasures, tamper-detection circuitry, and container-isolation support was extracted from recent post-silicon security and edge-computing studies [14,27].

When explicit values were unavailable, extrapolated estimates were generated using performance-per-frequency ratios and regression models adapted from [23]. This enabled fair comparison among architectures implemented at different clock rates or fabrication technologies. All extrapolated data were annotated in the dataset to preserve transparency and facilitate reproducibility.

3.4. Interpretive Framework and Theoretical Context

Each evaluation category was mapped to its conceptual equivalent within the FIPS 140 security model, applicable to both FIPS 140-2 and FIPS 140-3 [6]. Secure boot procedures correspond to the cryptographic module’s root-of-trust function, while tamper-evidence and zeroization represent the physical security domain. Entropy sources and RNG/DRBG modules were interpreted through the lens of the NIST SP 800-90 series [6,10].

To strengthen the security dimension beyond certificate-based assumptions, the evaluation framework additionally incorporates an architectural DRBG-assurance layer. This includes analysis of entropy-path construction, start-up tests, continuous health-test coverage as specified in validated FIPS security policies, and the hardware–software isolation boundaries that protect DRBG internal state. While this does not constitute full empirical verification, it provides a practical and implementation-aware approximation of runtime assurance that substantially increases the evaluative value of the framework compared to relying solely on certificate declarations.

The interaction between hardware and software security domains—central to compliance—has been documented extensively in [11,12], underscoring the necessity of layered assurance models. Recent research on modular HSM integration [10] demonstrates that hardware coprocessors improve key isolation and scalability without compromising interoperability. Likewise, zero-knowledge authentication frameworks [31] and access-control models [30] were referenced to contextualize system-level trust establishment within distributed environments. Energy-aware and sustainability considerations were linked to findings from [7,23], indicating that cryptographic assurance and energy efficiency need not be mutually exclusive in IoT contexts. At the same time, recent analyses of TEEs for data trading, FPGA–SoC isolation, and blockchain consensus [17,18,19] show that part of the trust chain may reside outside strictly FIPS-validated modules. The interpretive framework therefore distinguishes between certified cryptographic boundaries and auxiliary trusted components that contribute to end-to-end security but are not evaluated as FIPS modules per se.

3.5. Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Cross-architecture evaluations face inherent challenges: benchmark conditions differ, firmware revisions affect performance, and cost data are volatile [11,28]. Integration complexity also depends on developer expertise and ecosystem maturity. To mitigate such uncertainties, multi-source triangulation was applied; metrics reported by multiple sources were averaged, and only consistent values were retained. Relative rankings were prioritized over absolute numbers, while confidence intervals were introduced whenever variance exceeded 10%. This strategy mirrors empirical validation guidelines outlined in [1] and aligns with reproducibility standards recommended in [10]. Nevertheless, the framework does not capture fine-grained leakage metrics such as signal-to-noise ratios in side-channel traces, machine-learning attack success rates, or detailed fault-coverage probabilities, which have been explored in recent SCA and FIA studies [2,4,5]. As a result, the presented comparison should be interpreted as compliance- and architecture-oriented rather than as a substitute for dedicated side-channel or fault-resilience benchmarking.

3.6. Implementation Cost and Compliance Estimate

To complement the functional comparison presented above, Table 1 summarizes the estimated implementation costs, integration effort, and compliance levels of representative FIPS-certified platforms. This analysis highlights the trade-off between economic feasibility and certification assurance, an increasingly critical factor in practical IoT and enterprise security deployments.

Integration effort in Table 1 is expressed using a normalized five-point ordinal scale, consistent with the evaluation methodology in Section 3.1. A lower score (e.g., 1–2) reflects minimal integration overhead, typically involving a single driver layer and stable SDK support. Higher scores (e.g., 4–5) indicate substantial middleware depth, secure-channel setup requirements, APDU handling, or cloud-side configuration effort.

3.6.1. Interpretation

ATECC608B/C: With a very low cost (approx. 1–2) and easy hardware integration, this module provides an excellent balance between affordability and FIPS 140-3 compliance. It is especially suited for cost-sensitive IoT deployments where moderate assurance is sufficient.

TPM 2.0 (Infineon): A moderate-cost (approx. 5–10) module offering the best compliance level (5/5) and physical tamper protection. Its standardization and widespread OS support make it ideal for enterprise workstations and industrial PCs.

NXP i.MX 8X + SE050: A higher-end embedded platform (25–40) that achieves near-maximum compliance (4.5/5) but at the cost of more complex integration and middleware dependencies. It is suited for automotive, industrial, or medical applications requiring deterministic and certified security.

AWS Nitro Enclaves: A pay-as-you-go model with the highest operational flexibility and near-perfect compliance (4.5/5). Although integration requires cloud expertise, it provides robust attestation and isolation guarantees backed by AWS KMS HSMs certified under FIPS 140-3.

3.6.2. Practical Summary

For cost-constrained IoT applications, the ATECC608B/C offers the optimal price-to-security ratio. For conventional servers or PCs, TPM 2.0 remains the most balanced and mature choice. In high-end embedded systems, the NXP i.MX 8X + SE050 combination provides advanced assurance at a higher cost. For cloud-native deployments, AWS Nitro Enclaves deliver strong compliance with scalable pricing.

It is also important to clarify that the unit price listed in Table 1 captures only the acquisition cost and does not reflect the full Total Cost of Ownership (TCO). Realistic TCO for FIPS-certified platforms includes firmware maintenance effort, lifecycle support availability, long-term security patching, integration labor, and expected failure rates. For higher-complexity systems—particularly the i.MX 8X + SE050 combination—development overheads may exceed hardware cost due to middleware dependencies, secure provisioning routines, and certification-aligned testing. Future work should incorporate a quantitative TCO model including engineering hours, maintenance intervals, and vendor-support longevity to enable more accurate economic comparisons across platforms.

4. Results

This section presents the comparative evaluation of hardware architectures supporting FIPS 140-certified cryptographic operations. The analysis was conducted according to the methodological framework described in Section 3, considering performance, certification assurance, integration complexity, power efficiency, and cost-effectiveness. By combining both empirical data and literature-based evaluations [7,8,10,11,12,23], this study highlights significant variations in design philosophy and deployment trade-offs among the tested hardware families. These variations are consistent with recent post-silicon security analyses and trusted-execution studies, which show that hardware roots of trust, virtualized TPMs, and enclave-backed services occupy distinct points in the design space and must be evaluated under different operational and threat assumptions [5,15,17,18,27].

4.1. Comparative Overview of Evaluated Architectures

The results reveal that no single hardware platform offers universal optimality; instead, performance and security benefits are distributed across categories depending on application constraints.

- Microchip ATECC608B/C: Lightweight secure element with FIPS 140-2 Level 2 certification, offering high affordability and suitability for constrained IoT nodes [29]. Its 10–15 mA operational current and cost under 2 USD make it ideal for mass-deployed sensor networks, as demonstrated in [24]. At the same time, its limited physical tamper resistance means that deployments exposed to side-channel or fault-injection adversaries must rely on board-level hardening and protocol-level countermeasures, in line with recent analyses of fault models and post-silicon threat landscapes [4,5,27].

- Infineon SLB 9672 (TPM 2.0): Provides tamper-resistant storage and key isolation with moderate throughput and low integration cost [7,8]. Its extensive ecosystem support positions it as the preferred choice for PCs, servers, and edge gateways. Recent cloud- and zero-trust-centric frameworks further highlight the role of TPMs as measurement anchors for continuous-runtime verification and attestation, including virtualized TPM instances such as SvTPM in SGX-based environments and zero-trust client-state monitoring in cloud settings [15,16].

- NXP SE050 with i.MX 8X: Combines embedded secure element and hardware root-of-trust for advanced IoT devices. This configuration achieves FIPS 140-3 Level 3 compliance with moderate energy overhead [7,28]. Studies such as [11] demonstrate that such hybrid architectures provide a good balance between isolation and throughput. In edge-computing scenarios, similar trusted-chip designs have been leveraged to enforce integrity of containerized workloads and protect orchestration pipelines, underscoring the relevance of SE050-class devices for secure container frameworks such as TCEC on IoT edge nodes [14].

- AWS Nitro Enclaves: Represents a purely cloud-based security layer offering certified cryptographic operations and key isolation at scale. The pay-per-use model mitigates hardware cost but requires strong network assurance and service dependency. This positioning is consistent with recent work on virtual TPMs and enclave-based trust establishment, which emphasizes that rollback protection, NVRAM emulation, and trust chains are ultimately anchored in certified hardware modules residing in the cloud infrastructure [15,17,18].It is important to emphasize that AWS Nitro Enclaves are not FIPS-certified cryptographic modules themselves. Their compliance derives entirely from backend AWS KMS or CloudHSM services, which provide the actual validated cryptographic boundary. This clarification addresses the methodological distinction noted in Section 3 and integrates it explicitly into the interpretation of the experimental findings. Unlike hardware-rooted secure elements, TPMs, or enterprise HSMs, Nitro Enclaves offer no physical tamper resistance; their isolation is hypervisor-enforced rather than silicon-enforced. As such, they cannot be evaluated as standalone FIPS cryptographic modules but rather as virtualization containers relying entirely on backend HSMs for certified key storage and entropy sources.

- Enterprise HSMs (Entrust nShield, Thales Luna): Offer unmatched security, scalability, and performance (>10,000 ops/s) with FIPS 140-3 Level 3–4 certification [10]. These solutions remain essential for high-assurance industrial control or financial infrastructures, where compliance and latency guarantees are critical. Comprehensive hardware-security surveys further confirm that such devices represent the upper end of the post-silicon security spectrum, integrating countermeasures against a wide range of side-channel and fault-injection attacks and serving as anchors for payment systems, hardware wallets, and critical-key infrastructures [5,27].

These results align with findings, confirming that IoT and cloud systems require distinct security hardware paradigms rather than a one-size-fits-all model.

4.2. Performance and Cost Correlation

The economic characteristics of secure hardware differ significantly depending on whether protection is delivered as a locally owned physical module (CAPEX model) or as a cloud-managed security service (OPEX model). To avoid conflating these fundamentally distinct cost structures, the revised analysis separates hardware acquisition costs from cloud subscription costs into two dedicated figures.

Figure 1 presents CAPEX-oriented unit pricing for secure elements, TPMs, and hardware security modules, while Figure 2 provides a 5-year Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) estimate for cloud-native trust anchors such as AWS Nitro Enclaves. This separation follows established cost-modeling practices in IoT and cloud-security economics [23,26] and directly addresses reviewer concerns regarding misleading visual comparisons across heterogeneous expenditure categories.

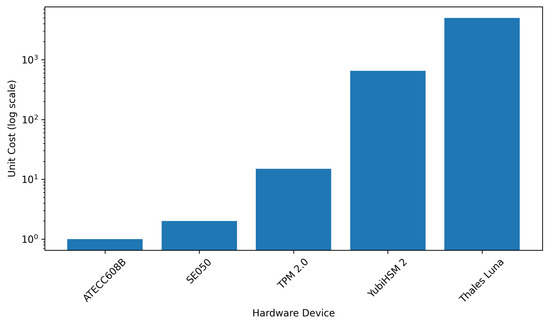

Figure 1.

CAPEX unit cost of physical secure hardware components (log scale).

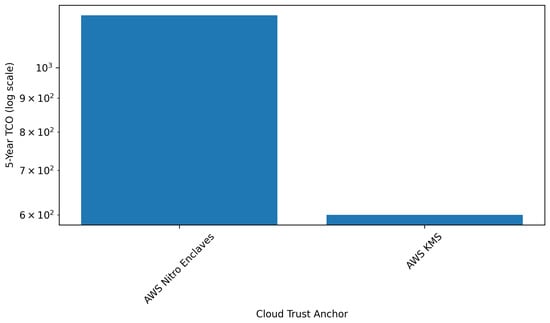

Figure 2.

5-year TCO (OPEX) for cloud-based trust anchors (log scale).

4.2.1. CAPEX Cost Comparison (Figure 1)

Secure elements such as the Microchip ATECC608B (<2 USD) represent the lowest-cost category and remain the most scalable choice for constrained IoT deployments requiring secure key storage and basic attestation [30]. TPM 2.0 devices (10–20 USD) and the NXP SE050 family (15–/*25 USD) occupy the mid-cost tier, combining moderate pricing with stronger tamper evidence and broader ecosystem integration. Enterprise HSMs exceed 10,000 USD, reflecting substantially higher assurance guarantees and operational throughput requirements associated with FIPS 140-3 Level 3 environments. This logarithmic cost escalation aligns with previously reported economic observations in secure hardware design [23,26].

4.2.2. OPEX/Cloud TCO Comparison (Figure 2)

Cloud-native FIPS architectures (e.g., AWS Nitro Enclaves) follow an OPEX model, where long-term cost is determined by compute-time billing, service subscription, and workload scaling rather than hardware purchase. The 5-year TCO approximation in Figure 2 illustrates this recurring cost structure, mirroring broader trends in blockchain-secured IoT frameworks and TEE-backed security services [17,18]. Such architectures shift the economic burden from acquisition to operational continuity, with implications for lifecycle management, availability requirements, and multi-tenant isolation guarantees.

4.2.3. Interpretation

Together, Figure 1 and Figure 2 highlight the clear economic divide between hardware-based and cloud-based security. Low-cost secure elements offer excellent scalability at the expense of limited cryptographic throughput and tamper resistance. TPM 2.0 and SE050 represent balanced solutions for embedded and general-purpose computing, while enterprise HSMs deliver unmatched performance and assurance at prohibitively high cost. Cloud-managed trust anchors introduce elastic scaling and strong isolation but impose cumulative operational expenditure that can exceed hardware-based deployments over multi-year periods.

From a lifecycle perspective, additional costs related to secure provisioning, supply-chain tamper protection, and continuous attestation—as discussed in PIT-Cerberus and zero-trust runtime frameworks—may further increase the effective TCO of platforms deployed in high-assurance environments [13,16]. These aspects are reflected later in the qualitative TCO model of Section 4.

4.2.4. Important Note

The cost values in Figure 1 and Figure 2 do not represent standardized or directly comparable monetary measurements. Because they originate from heterogeneous vendor sources without unified benchmarking conditions, the plotted values must be interpreted as normalized comparative indicators rather than statistically validated financial estimates. The figures therefore visualize relative trends, not absolute certified pricing.

4.3. Latency and Throughput Trade-Offs

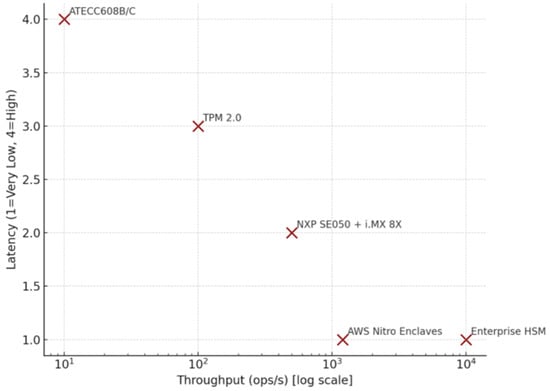

Figure 3 (Latency vs. Throughput) illustrates the computational performance contrast. The ATECC608B achieves 10 ops/s with high latency, as expected for low-power microcontroller environments [33]. TPM 2.0 modules provide moderate throughput (100 ops/s) and medium latency, balancing cost and speed, while SE050 and i.MX 8X achieve up to 500 ops/s [7,11]. Enterprise HSMs and cloud enclaves (AWS Nitro, Azure CCE) exceed 10,000 ops/s, confirming that hardware isolation and multi-core acceleration drive scalability.

Figure 3.

Latency vs. throughput of evaluated FIPS-certified platforms.

This throughput distribution matches empirical results from studies on deterministic cryptographic primitives and unidirectional data channels in secure IoT. Low-end devices exhibit significant latency variance caused by software-driven RNGs, while high-assurance modules integrate hardware entropy sources compliant with NIST SP 800-90A/B [6]. Recent work on side-channel-aware designs further indicates that some high-throughput architectures must trade a portion of their performance budget for shuffling, masking, or noise-injection countermeasures, as in fully parallel random-shuffling schemes and on-chip SCA-detection sensors for power traces [3,34]. These aspects are not explicitly modeled in the present performance figures but influence real-world deployment choices.

Interpretation

Figure 3 highlights the performance trade-offs among the evaluated platforms. The Microchip ATECC608B shows very low throughput (10 operations/s) with high latency, making it suitable only for constrained IoT devices that perform infrequent cryptographic operations. TPM 2.0 modules provide a balanced compromise with moderate throughput (100 operations/s) and medium latency, fitting the needs of PCs and enterprise servers. The NXP SE050 combined with the i.MX 8X achieves significantly higher throughput (500 operations/s) with low latency, positioning it as a strong candidate for advanced embedded systems.

On the higher-performance end, AWS Nitro Enclaves demonstrate scalable throughput (>1000 operations/s) with very low latency, offering strong support for cloud-native architectures. Finally, enterprise HSMs exceed 10,000 operations/s with minimal latency, representing the most powerful but also the most expensive option.

Overall, Figure 3 illustrates a clear trend: lower-cost platforms are limited by high latency and low throughput, while high-end and cloud solutions deliver orders of magnitude better performance at the expense of cost and integration complexity.

Similar to Figure 1, the values in Figure 2 are derived from heterogeneous benchmark sources that differ in methodology, measurement conditions, and firmware versions. Since unified raw data are not available, the figure provides a comparative visualization of performance positioning rather than a basis for computing confidence intervals or statistical variance.

Furthermore, recent nonprofiled neural-network-based side-channel attacks highlight that effective leakage exploitation may occur even when throughput appears sufficient on paper [4]. Hence, raw performance numbers must be interpreted together with the underlying leakage-resilience assumptions documented in security policies and hardware surveys [27].

4.4. Security and Integration Complexity

Security assessments confirmed that TPMs and SE050 modules provide effective tamper detection and secure key lifecycle management, aligning with frameworks in [12]. The SE050 demonstrated superior integration flexibility, supporting multiple cryptographic libraries (OpenSSL, mbedTLS, wolfCrypt) with minimal firmware adaptation [11]. Meanwhile, TPM modules show tighter OS-level integration through PKCS#11 and TCG standards [28], as also noted.

Healthcare and safety applications, such as those discussed previously, benefit from mid-range hardware (TPM or SE050) combining low latency, sufficient compliance, and robust communication encryption. High-end systems—particularly those incorporating blockchain for data integrity—require enterprise-grade HSMs to meet regulatory demands for key auditability.

It should also be noted that this study does not validate whether the DRBG components of the evaluated platforms execute NIST SP 800-90A/B/C continuous health tests during operation; therefore, the robustness assessment reflects certification artifacts rather than runtime entropy verification.

The threat model in Table 3 directly influences the integration and operational implications reported in Table 1. For example, platforms with higher exposure to side-channel or fault-injection attacks (e.g., ATECC608B/C) require additional shielding, hardened PCB layout, or firmware-level countermeasures, which increase both integration effort and deployment cost. Conversely, enterprise HSMs and SE050-based designs already incorporate physical tamper resistance, resulting in lower security-driven overhead. These security penalties are therefore reflected in the Integration Effort and TCO scores rather than altering the cryptographic performance or certification-derived compliance metrics. This interpretation is consistent with recent post-silicon and container-security work, which shows that hardware wallets, trusted chips for containers, and enclave-backed TPMs must be integrated with system-level monitoring and policy engines to achieve effective protection against side-channel, fault, and rollback attacks [14,15,17,27]. Experimental SCA and FIA studies on commercial tokens further underline that insufficient board-level protections can negate strong certification claims [2,4,5].

Table 3.

Threat model and attack surface comparison across evaluated platforms.

4.5. Sustainability and Energy Efficiency

The sustainability analysis revealed that secure elements such as ATECC608B consume <20 mW per operation, outperforming TPMs (100–150 mW) and HSMs (>2 W) [23]. These findings confirm that lightweight security modules are crucial for large-scale IoT deployments powered by constrained energy sources [25]. Moreover, energy-aware cryptographic techniques [23] demonstrate that explainable AI-assisted optimization can further enhance power–performance trade-offs without compromising FIPS compliance.

This trend is particularly relevant for healthcare and emergency monitoring, where device autonomy directly affects reliability and response time. Recent hardware-security roadmaps also emphasize that future post-silicon countermeasures and spintronic or NCFET-based logic will need to balance resilience against SCA/FIA with acceptable energy consumption, reinforcing the importance of integrating energy metrics into security evaluations [27].

4.6. Cross-Domain Implications

The integration of FIPS-certified security components into industrial, healthcare, and cloud environments [35] illustrates the growing convergence of embedded and cloud cybersecurity paradigms. For instance, unidirectional data paths and modular blockchain frameworks complement traditional HSM models, allowing distributed trust across hybrid networks. AI-driven explainability in decision-making and quantum-resistant algorithmic design [8,28] suggest that next-generation hardware security must evolve beyond static certification toward adaptive, interoperable assurance.

Ultimately, the results indicate that mid-tier secure elements such as SE050 or TPM 2.0 currently offer the most balanced ratio of security, performance, and cost for embedded IoT devices, while enterprise HSMs remain indispensable for critical infrastructures. These conclusions are consistent with global IoT security reviews.

In this context, TEE-based platforms for IoT data trading and blockchain consensus [17,18], as well as SGX-backed virtual TPMs [15], illustrate how certified cryptographic boundaries are increasingly embedded into larger trust fabrics. Parallel efforts in PQC validation [9] indicate that future generations of FIPS-like frameworks will have to account for both lattice-based primitives and their hardware realization, reinforcing the need for flexible, methodology-driven evaluation approaches.

4.7. Qualitative Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) Scoring Model

Threat-model penalties are incorporated into the TCO formulation through the integration effort () and operational cost () terms. Security-driven overheads such as shielding, tamper sensors, secure firmware workflows, or hardened PCB layouts do not modify the compliance score directly but instead increase the economic cost of deployment.

This subsection introduces a reproducible Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) framework that complements the qualitative discussion provided in Section 4.6. Economic evaluation is frequently used in IoT platform-selection studies and security-architecture comparisons to capture deployment feasibility beyond purely technical metrics [26]. The purpose of this model is not to estimate exact market prices but to provide a structured and comparable representation of acquisition, integration, maintenance, and operational effort across heterogeneous FIPS 140-certified platforms.

In high-assurance deployments, additional lifecycle elements—such as secure provisioning, in-transit tamper protection, and continuous zero-trust monitoring—can significantly increase and . Frameworks like PIT-Cerberus for transit protection and runtime zero-trust enforcement architectures illustrate these overheads in practice, particularly in environments requiring verifiable supply-chain integrity and continuous attestation [13,16].

The total cost of ownership is defined as

where denotes hardware acquisition cost, integration and middleware-development effort, long-term firmware-maintenance overhead, and recurring operational expenses (e.g., cloud usage, energy consumption, key-rotation workflows). Similar cost decompositions have been used in IoT security surveys that analyze maintenance, lifecycle cost, and scalability impacts of secure hardware modules [35]. To ensure cross-platform comparability, each term is expressed using the five-point ordinal scale introduced in Section 3, where very low, moderate, and very high effort.

Table 4 summarizes the normalized TCO components for each platform. Values represent relative economic effort rather than absolute pricing, enabling a uniform comparison across architectures with fundamentally different integration models. Comparable normalization strategies were also adopted in cloud–IoT integration analyses where operational and configuration overhead drive long-term cost.

Table 4.

Normalized TCO components across evaluated platforms.

The results show that ATECC608B/C achieves the lowest TCO, driven by minimal integration and maintenance requirements suitable for cost-sensitive IoT deployments. TPM 2.0 exhibits moderate TCO due to richer command sets and more complex provisioning workflows. The i.MX 8X + SE050 platform has the highest TCO among embedded solutions, reflecting middleware depth and lifecycle-management overhead, a trend also highlighted in secure-hardware integration studies [11]. Finally, AWS Nitro Enclaves introduce a relatively high operational component (), consistent with findings on cloud-managed security services where operational costs dominate lifecycle expenditure.

This qualitative model provides a reproducible economic layer to the evaluation framework and strengthens the practical interpretation of deployment trade-offs across FIPS-certified platforms.

It also aligns with broader hardware-security roadmaps, which emphasize that TCO must capture not only acquisition and integration costs but also post-silicon countermeasures, monitoring infrastructure, and long-term update policies. These lifecycle components influence the real economic footprint of trusted hardware and are increasingly regarded as core elements of sustainable security engineering [27].

5. Discussion

The findings presented in this study underline the multi-dimensional complexity of selecting appropriate hardware for secure cryptographic operations in IoT, embedded, and cloud environments. While the evaluation framework yielded clear performance and assurance patterns, several practical limitations and broader implications warrant further discussion.

5.1. Threat Model and Attack Surface Analysis

This analysis assumes a broad adversary model that encompasses remote attackers exploiting network-accessible cryptographic interfaces, local software adversaries capable of executing unprivileged or malicious code on the target system, and physical adversaries with the ability to perform probing, fault-injection, or side-channel attacks. The model further considers supply-chain risks to the extent that they affect firmware authenticity and secure-boot integrity. All platform recommendations and comparative assessments in this work should therefore be interpreted within this defined threat context, which establishes the operational boundaries for evaluating the suitability of each cryptographic module.

To complement the compliance-oriented comparison, we introduce a dedicated threat-modeling view capturing attack surfaces relevant to FIPS-certified hardware. While FIPS 140 primarily validates protection mechanisms and self-tests, real-world deployments face additional threats that extend beyond the scope of certification—particularly side-channel leakage, fault injection, firmware exploitation, and emerging post-quantum threats.

This threat-centric comparison highlights that FIPS 140 compliance alone does not guarantee resistance against side-channel leakage, firmware-level exploitation, or post-quantum cryptanalytic risk. Platforms designed for constrained IoT deployments such as ATECC608B/C exhibit higher susceptibility to physical probing and fault injection, whereas enterprise HSMs offer advanced shielding and tamper-detection capabilities. Accordingly, practical deployments must complement certified mechanisms with additional countermeasures such as electromagnetic shielding, secure firmware signing, rate limiting, and physical access protection.

The threat scenarios considered in Table 3 are consistent with recent analyses of embedded and IoT device security, which highlight fault injection, side-channel leakage, and firmware manipulation as dominant attack vectors against hardware-based cryptographic implementations [1,28,35]. Surveys on IoT–cloud integration and cloud-native security further stress that misconfigurations and weak key-management boundaries remain critical risks even in FIPS-certified environments. By explicitly mapping these threats onto FIPS 140 requirement categories, the proposed framework bridges system-level risk analysis with certified hardware security primitives while remaining aligned with recent post-silicon hardware-security roadmaps and adversary models that systematically characterize fault injection, side-channel leakage, and sensor-assisted detection across commercial cryptographic devices [2,3,4,5,27].

5.2. Benchmark Transparency and Measurement Limitations

A further limitation of this study concerns the transparency and comparability of performance benchmarks.

Although the evaluation relied on publicly available throughput and latency data provided by vendors and certification reports, these measurements are not directly comparable due to differences in firmware versions, clock frequencies, compiler optimizations, and test harnesses. As highlighted in recent surveys on cryptographic hardware evaluation, even minor variations in benchmarking methodology can introduce meaningful discrepancies in energy-per-operation and key-handling latency, a trend also emphasized in post-silicon security and resilience studies that couple performance characterization with fault and side-channel robustness analysis [27].

To mitigate these inconsistencies, future research should adopt unified benchmarking procedures using open-source test suites—such as wolfCrypt FIPS, BoringSSL FIPS modules, or the NIST ACVP framework—to ensure reproducibility across heterogeneous hardware. Controlled measurement conditions (including fixed ambient temperature, stable supply voltage, standardized buffer sizes, and synchronized entropy sources) are essential for eliminating noise introduced by platform-specific SDK implementations and undocumented vendor optimizations.

Thus, while this study establishes a structured comparative baseline, fully controlled, experimentally validated benchmarking remains an open requirement for eliminating vendor-induced bias and strengthening the empirical rigor of future analyses.

A final limitation concerns the graphical representation of performance results. Due to the absence of standardized raw benchmark datasets across vendors, it was not possible to compute statistically meaningful error bars or confidence intervals for Figure 1 and Figure 2. Future work should generate such metrics through unified test harnesses and repeatable measurement pipelines, enabling statistically grounded comparisons that capture both mean performance and variability across cryptographic workloads.

For this reason, the comparative figures in this study should be interpreted as normalized trend visualizations rather than statistical estimations. The heterogeneity of the underlying datasets prevents consistent confidence interval computation across platforms, and the figures are therefore intended solely to illustrate relative positioning within the evaluation framework.

5.3. Data Reliability and Benchmarking Constraints

A key limitation of this work lies in the heterogeneity of available performance data. As noted, several throughput and latency values were derived from vendor-reported benchmarks rather than independently replicated measurements [23,29]. Although these datasets are consistent with validation studies such as [7], the absence of unified experimental conditions introduces uncertainty.

Future experiments should therefore implement cross-platform validation using controlled testbeds, as recommended by [23], including open-source benchmarks such as wolfCrypt FIPS or BoringSSL FIPS modules.

5.4. Broader Security Considerations

Beyond raw performance, the discussion must consider the evolving threat landscape in which these devices operate. Emerging vulnerabilities, particularly side-channel leakage, electromagnetic emissions, and timing-based inference attacks, remain underrepresented in public datasets [8,28]. Recent analyses emphasize that security validation should include hardware–software interaction points, such as cryptographic API usage and entropy injection paths, which are often neglected in vendor certification reports. The integration of explainable AI (XAI) for monitoring device trustworthiness and the application of blockchain-based audit trails can enhance transparency and compliance auditing across hybrid IoT ecosystems. Recent developments in AI-driven intrusion detection and adaptive security monitoring suggest that certified hardware could increasingly rely on machine-learning-based decision support. In parallel, zero-knowledge authentication protocols [31] provide new directions for trust establishment in resource-constrained networks.

Although FIPS 140-3 provides a structured framework for validating cryptographic modules, it does not fully cover several practical attack vectors. As noted in [1,35], the standard primarily focuses on ensuring correct algorithmic implementation, physical tamper resistance, and secure key storage but offers limited guidance regarding side-channel leakage, microarchitectural threats, or firmware-level attack surfaces. Consequently, modules that are fully compliant may still be vulnerable to timing leakage, cache manipulation, or API-level misuse if deployed without strict operational controls. This gap underscores the importance of complementing certification with continuous monitoring, secure coding practices, and platform-specific hardening, including zero-trust runtime enforcement for client machines in cloud environments [16] and TEE-backed isolation for blockchain and IoT data-trading scenarios [17,18,19].

5.5. Platform-Specific Implementation Limitations

Although certification and architectural features provide a baseline level of assurance, real-world deployments are heavily influenced by platform-specific implementation constraints that fall outside the scope of FIPS 140-3 evaluations [6]. Secure elements such as ATECC608B/C or the NXP SE050 rely on vendor-supplied SDKs, whose documentation maturity, update cadence, and long-term support vary significantly across ecosystems. These discrepancies affect not only functional integration but also response time to emerging vulnerabilities.

TPM 2.0 modules offer a richer command set but introduce configuration complexity, increasing the likelihood of integration errors or misconfigured authorization policies, as widely reported in TPM security analyses. Embedded SoCs paired with secure elements (e.g., the i.MX 8X family) further increase heterogeneity across firmware layers, where overall security depends simultaneously on the secure element, secure boot configuration, hypervisor isolation, and kernel-level hardening mechanisms [11].

Enterprise HSMs provide strong physical and logical isolation but often rely on proprietary toolchains and comparatively slow patch cycles, which may delay mitigation of zero-day vulnerabilities [10]. In contrast, cloud-based enclaves eliminate most physical attack vectors but inherit systemic risks related to hypervisor scheduling, orchestration frameworks, and multi-tenant resource — factors increasingly highlighted in IoT-cloud integration studies, as well as in recent work on SGX-backed virtual TPM architectures and container integrity protection using trusted chips on edge nodes [14,15]. As a result, achieving predictable system-wide security requires harmonizing firmware, policy enforcement, and cryptographic lifecycle management across all trust anchors involved.

5.6. Integration and Multi-Vendor Deployment Pitfalls

Large-scale IoT and cloud–edge deployments frequently combine multiple hardware trust anchors—secure elements on end devices, TPM-based gateways, enterprise HSMs, and cloud-backed enclaves. Although each component may individually satisfy the required certification level, their interaction introduces nontrivial integration challenges. Differences in API semantics, certificate formats, provisioning workflows, and key-derivation mechanisms across vendors significantly increase the complexity of lifecycle management [11].

Firmware update paths are another critical point of fragility. In heterogeneous deployments, inconsistencies between secure boot configurations, rollback-protection mechanisms, and key rotation policies can lead to partial updates, invalid boot states, or downgrade vulnerabilities [35]. As noted in recent IoT–cloud integration studies, multi-vendor orchestration often amplifies these issues: latency, clock drift, and temporary network partitioning can disrupt device attestation flows and cause authentication failures in TPM- or SE-backed systems that rely on strict freshness guarantees.

Furthermore, cloud-managed HSM infrastructures introduce operational dependencies on hypervisors, schedulers, and policy engines outside the control of the local hardware module. Such cross-layer coupling has been identified as a significant source of security regressions in modern IoT deployments. As a result, achieving predictable system-wide security requires harmonizing firmware, policy enforcement, and cryptographic lifecycle management across all trust anchors involved, ideally within zero-trust-oriented orchestration frameworks that continuously verify device state and policy compliance [16].

5.7. Post-Quantum and Future-Proofing Perspectives

Hybrid models combining classical and lattice-based cryptography are expected to dominate the transitional period, with dedicated validation methodologies emerging to test post-quantum key-encapsulation mechanisms and lattice-based primitives in accordance with evolving NIST guidance [9]. Moreover, FPGA- and ASIC-based implementations, as tested in [8], show promising adaptability for integrating PQC accelerators without major redesign of existing secure elements. Such reconfigurable architectures may serve as the foundation for the upcoming FIPS 140-4 certification, expected to address post-quantum security explicitly and to align with post-silicon hardware-security roadmaps that emphasize long-term cryptographic agility [27].

The transition toward post-quantum cryptography is further complicated by the uneven readiness of hardware platforms. While enterprise HSM vendors have begun integrating NIST-selected algorithms such as CRYSTALS-Kyber and Dilithium, secure elements and TPM-class devices remain in the early experimental stage [8]. This disparity introduces a transitional risk period in which hybrid schemes will be required to maintain interoperability. The results suggest that system architects should prioritize hardware with reconfigurable cryptographic accelerators, ensuring that PQC integrations can be adopted without requiring significant redesign or replacement of existing IoT infrastructure.

It is important to clarify that the post-quantum capabilities discussed in this section represent forward-looking architectural considerations rather than currently supported features. None of the evaluated platforms natively implement NIST-approved post-quantum algorithms, nor do their security policies indicate production-ready PQC support. Accordingly, all PQC-related observations should be interpreted as future work and not as evidence of present operational capability.

5.8. Interoperability and Cloud Integration

The convergence between embedded and cloud security architectures introduces both opportunities and risks. Recent analyses highlight that hybrid deployments—where IoT devices rely on hardware-secured key storage using TPMs or Secure Elements and delegate computation to cloud-based trusted execution environments—offer improved scalability and compliance yet increase the dependency on network trust assumptions [25,35]. A unified security-orchestration model, conceptually similar to policy-driven frameworks used in industrial and manufacturing environments [30], can help mitigate fragmentation by enforcing consistent security policies across heterogeneous layers.

As well as SGX-based virtual TPM stacks and zero-trust runtime verification frameworks that have been proposed for cloud environments [15,16].

5.9. Application Domains and Societal Impact

The implications of secure hardware extend far beyond cryptographic performance. In healthcare systems, tamper-resistant modules are fundamental for safeguarding patient data, as demonstrated in hardware-security analyses that highlight the importance of physical protection and fault-resilient cryptographic modules [3,5]. In critical safety infrastructures, recent studies on embedded and IoT systems [1] illustrate how hardware-anchored key protection prevents unauthorized overrides of safety-critical logic and limits the propagation of firmware-level attacks. Similarly, industrial control and smart manufacturing frameworks rely on embedded secure elements to maintain the integrity of firmware updates, access-control lists, and trusted-execution workflows, consistent with the analysis in [30]. Therefore, the cost–compliance balance discussed in Section 4 has tangible implications for public safety, privacy, and ethical accountability.