Abstract

The DC collection system for wind farms serves as a critical component for power transmission, making its reliable operation paramount. Currently, research on the operational reliability of DC collection systems in wind farms remains largely confined to evaluation, with limited studies focused on enhancing reliability. This article introduces a Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) into the DC collection system from the perspective of improving reliability through the BESS. However, the introduction of a BESS significantly increases economic costs, with storage lifespan being a key factor affecting economic viability. To balance system reliability and BESS economics, this paper proposes a multi-objective configuration optimization method that accounts for the BESS lifespan, and employs the CRITIC-MARCOS integrated decision-making method to determine the optimal BESS configuration. Finally, the proposed method was validated in a 100 MW DC collection system for wind farms, offering valuable insights for BESS configuration schemes in such systems.

1. Introduction

With the increasing proportion of DC power sources and DC loads in the power system, DC grids have become a critical direction supporting the development of new power systems. Hence, constructing an efficient all-DC power system spanning from generation, to transmission, to consumption has become an inevitable choice to address future energy challenges. Against this backdrop, as the core hub connecting generation units and the transmission network, the reliable operation of the DC collection system is crucial for enhancing the efficiency of power collection and transmission in DC grids [1].

The collection system is a key link for power collection and transmission in wind farms. Traditional AC collection methods face growing limitations in large-scale wind power bases due to issues such as reactive power compensation, harmonic resonance, and long-distance transmission losses. In contrast, the DC collection system for wind farms rectifies the AC output from wind turbines, then boosts the voltage via DC/DC converters before collection and delivery [2]. This effectively avoids reactive power and harmonic issues, offering technical advantages such as a simple structure and flexible operation, making it more suitable for the efficient grid integration needs of future large-scale wind power [3].

However, the reliability of the DC collection system for wind farms is the foundation for its large-scale application. If a fault occurs in the DC collection system, it can lead to large-scale shutdowns of the wind farm, causing significant power loss and seriously threatening the security and stability of the power grid [4]. Therefore, assessing the reliability of the DC collection system for wind farms holds important theoretical significance and practical value for ensuring grid security and stability. Some scholars have already conducted research on the reliability evaluation of DC collection systems. For instance, references [5,6] employed analytical methods, specifically the Universal Generating Function method and reliability block diagrams, to analyze the mathematical models of different topologies of DC collection systems and subsequently evaluate system reliability. The studies [7,8], leveraging the advantages of both analytical and Monte Carlo methods, proposed improved reliability evaluation methods—the reliability block diagram–sequential Monte Carlo method and the fault tree–non-sequential Monte Carlo method, respectively—further optimizing the accuracy and speed of reliability evaluation for DC collection systems. A synthesis of existing research shows that the current focus on the reliability of DC collection systems for wind farms lies in improving the precision and efficiency of evaluation methods, while there remains a lack of exploration into how to enhance the system reliability itself.

The BESS, by virtue of its flexible regulation capability, demonstrates great potential in enhancing system power supply reliability and has been widely applied in AC systems. The study [9] analyzes the impact of factors such as BESS capacity and power on the reliability of hybrid wind–storage power systems. The results indicate that integrating the BESS can significantly improve system reliability, yet configuring the BESS solely for reliability benefits incurs excessive economic costs. To achieve a balance between system operational reliability and BESS configuration economics, numerous scholars are dedicated to constructing BESS planning models that consider both aspects. The study [10] establishes a multi-objective BESS configuration model, with the system loss of power supply probability and levelized cost of electricity as optimization objectives, but does not perform further decision-making on the Pareto solution set of the configuration results. The study [11] develops a multi-objective bi-level optimization configuration model for the BESS considering reliability, economy, and carbon benefits, solved using NSGA-II combined with sequential production simulation iteration.

However, most existing studies simplify the BESS battery lifespan to a fixed period, failing to fully account for the dynamic impact of frequent charging and discharging behaviors during actual operation on its lifespan and economics. Particularly under harsh operating conditions such as wind speed fluctuations and equipment failures, frequent deep charge–discharge cycles accelerate BESS life degradation. Therefore, the economic model in the study [12] employs the BESS loss cost to quantify degradation during operation, determining the configuration scheme via cumulative distribution curves. The study [13] introduces a BESS lifespan model based on the rain-flow counting method and employs a two-stage integrated decision-making method combining NASA-II and EWM-TOPSIS for the solution. The study [14] proposes an improved biogeography-based optimization algorithm to determine the optimal capacity and depth of discharge for a BESS in a microgrid, optimizing its economy and service life.

Both BESS life degradation and system reliability are influenced by the actual operating environment, especially the increased equipment failure rates and deteriorated system operating states caused by extreme weather. The study [15] focuses on Unmanned Observing Stations in extreme environments. It ensures the continuous and reliable operation of equipment under harsh conditions by constructing an electro-thermal coupling model that accounts for multiple weather impacts such as wind turbine icing and photovoltaic panel snow cover. The study [16] incorporates the influence of weather uncertainty into the capacity planning stage of large-scale hybrid wind–PV–storage power plants. Its optimization results verify the importance of capacity configuration under specific weather patterns for ensuring system reliability and economy.

In summary, the wind farm DC collection system is a critical link for enhancing wind power integration efficiency and constructing DC grids. However, existing research primarily focuses on improving reliability evaluation methods, with insufficient attention paid to proactively enhancing system operational reliability by configuring flexible resources such as a BESS. Although the BESS has been widely validated for improving power supply reliability, its existing configuration models are mostly built for AC systems. The optimization objectives (e.g., primary frequency regulation and reactive power support) fundamentally differ from the operational requirements of DC collection systems. Direct application to wind farm DC collection systems would lead to BESS configuration redundancy, limiting its engineering application value [17]. Furthermore, to avoid overly optimistic assessments of economic viability and reliability in the configuration schemes, it is necessary to account for dynamic life degradation during actual operation and the impact of extreme weather conditions. Therefore, it is essential to establish a BESS optimization configuration model tailored to the structural and operational characteristics of wind farm DC collection systems, in order to enhance system operational benefits and configuration rationality.

Addressing the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes a multi-objective optimal BESS configuration method suitable for wind farm DC collection systems. The main contributions are as follows:

- (1)

- A dynamic BESS lifespan model considering the influence of the State of Charge (SOC) is established. Building upon this, a whole-life-cycle economic model is constructed to more accurately reflect life degradation and economic costs under frequent charge–discharge behaviors.

- (2)

- A wind turbine output model based on the integration of K-means clustering and Markov chains was established, along with an equipment outage model refined by weather factors. The improvement in system reliability brought about by the BESS configuration was quantified using the sequential Monte Carlo method.

- (3)

- A multi-objective optimal BESS configuration model, balancing economy and reliability, is constructed and solved using MOPSO to obtain the Pareto front. Combined with the CRITIC-MARCOS integrated decision-making method, the optimal compromise solution balancing economy and reliability is selected from the set of non-dominated solutions.

The subsequent chapters of this paper are organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the topology of the DC collection system with an integrated BESS. Section 3 elaborates on the multi-objective optimal configuration model considering BESS economics and system reliability. Section 4 describes the model solution process based on MOPSO and CRITIC-MARCOS. Section 5 validates the effectiveness of the proposed method through a case study. Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Topology of the DC Collection System for Wind Farms with a BESS

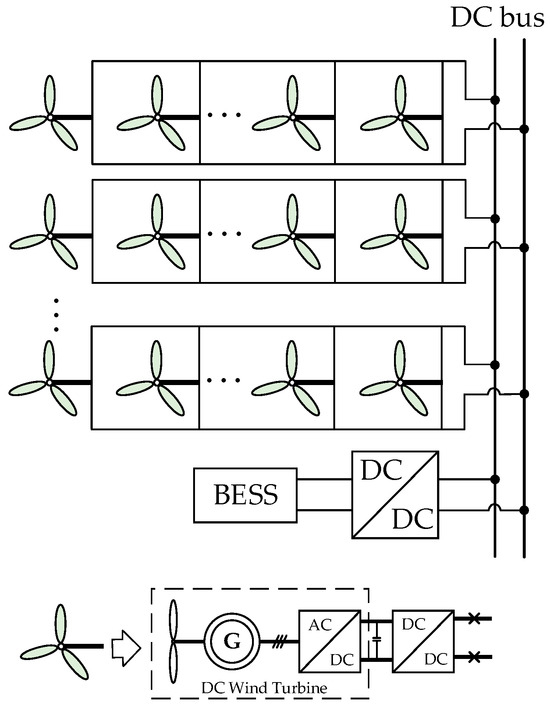

Common topologies for wind farm DC collection systems primarily include series, parallel, series–parallel, parallel–series, and matrix-interconnected types [18]. The series topology offers the advantages of a simple structure and low investment cost, but also exhibits significant reliability drawbacks. While the series–parallel topology improves system reliability to some extent, the entire wind farm may fail if an entire parallel cluster fails or if an interconnection fault occurs between parallel clusters. The matrix-interconnected topology, based on the series–parallel structure, incorporates additional switching devices to significantly enhance the reliability of the collection system. However, its numerous switching devices lead to complex control and high costs, imposing certain limitations in practical applications. The parallel topology connects wind turbines in parallel to form clusters, which are then further paralleled. This topology features a simple structure and offers numerous advantages, such as low coupling between turbines and high reliability. Therefore, this paper selects the parallel topology for the wind farm DC collection system as the research subject [3].

In the parallel topology, DC-based wind turbines, modified from direct-drive AC turbines, are employed to convert wind energy into DC power [4]. To enable DC output capability, an AC/DC rectifier is added in series to the direct-drive AC wind turbine; the DC voltage at the output of the machine-side rectifier typically ranges between 1 kV and 5 kV [19]. Due to the low voltage level at the output of the DC-based wind turbines, a DC/DC converter is connected in series after each turbine to boost the DC voltage level to ±30 kV, thereby avoiding significant power transmission losses. The power is then collected via a medium-voltage DC bus, with the topology illustrated in Figure 1 (where the arrow in the figure points to the detailed structural diagram of the DC-based wind turbine).

Figure 1.

DC parallel topology.

To achieve effective control of the overall system output, this paper opts to connect the BESS to the wind farm DC collection system in a centralized manner [20]. The BESS can be directly connected to the DC bus via a bidirectional DC/DC converter without the need for an inverter.

3. Multi-Objective Optimal Configuration Model for the BESS Considering Economics and System Reliability

To resolve the inherent conflict between the economic costs of the BESS and system reliability, and to achieve an effective trade-off between the two at the planning level, this section first constructs a BESS economic model that accounts for dynamic lifespan, based on the output model of the wind farm DC collection system. It then establishes a system reliability evaluation model to quantify the improvement in reliability resulting from the BESS configuration, ultimately providing a precise quantitative foundation for the multi-objective optimization.

3.1. BESS Economic Model Considering Service Life

The BESS responds in real time according to its operating state: when a system fault causes a power deficit and the BESS SOC permits, it immediately discharges to compensate for the power deficit. As its charging and discharging processes are entirely driven by random fluctuations in wind turbine output and occasional system faults, the BESS operating conditions exhibit strong non-periodicity and irregularity. This irregular operation accelerates the aging of the battery, significantly impacting its service life. To accurately quantify the impact of BESS life degradation on its whole-life-cycle economics and avoid overly optimistic planning configuration results, it is necessary to establish a BESS life prediction model that can reflect dynamic operating conditions and embed it within the economic evaluation framework.

3.1.1. BESS Charging/Discharging Model

As a key unit within the DC collection system for wind farms, the BESS features bidirectional power regulation capability, allowing it to flexibly respond to system power demands. During operation, the SOC of the BESS is updated according to the following equations [21]:

where SOC(t) denotes the SOC of the BESS at time t, Pc(t) and Pd(t) represent the charging and discharging power of the BESS at time t, respectively, denotes the time step, is the charging and discharging efficiencies, and Eb is the rated energy capacity of the BESS.

3.1.2. BESS Life Model Considering the Influence of the SOC

The service life of a BESS is influenced by factors such as the SOC, depth of discharge (DoD), and the number of charge–discharge cycles [22]. The traditional Ah-throughput model is a fundamental approach for assessing BESS service life. Its core assumption is that the total electrical energy a BESS can throughput over its lifetime is similar under different depths of discharge. The total energy throughput Ethrough is calculated as follows [23]:

where DoDi is the depth of discharge for the i-th test, Ni is the total number of cycles for the i-th test, and Nt is the total number of tests conducted at different depths of discharge.

However, the traditional Ah-throughput model does not fully consider the differential impact of the SOC on the rate of life degradation. Research indicates that under the same DoD, charge–discharge behaviors in the low SOC range cause more severe degradation to battery life. To characterize this dynamic aging behavior, this paper introduces a life degradation weight factor related to the SOC, to modify the traditional Ah-throughput model. This weight function is characterized by a piecewise linear function relating to the SOC(t) at time t:

Building on this, an improved Ah-throughput model considering the influence of the SOC is established. The equivalent life loss throughput ELoss over time T is defined as follows:

where P(t) is the charge–discharge power of the BESS at time t.

The degradation coefficient L is used to quantify the progress of BESS life consumption:

When L = 1, it means the BESS has reached its end of life. Therefore, the actual operating time it takes for L to accumulate from 0 to 1 is the BESS service life predicted by the model in this paper.

It is important to note that this model focuses on the coupled impact of the frequent charging and discharging behaviors of energy storage (driven by wind speed fluctuations and equipment failures) and the dynamic changes in the SOC on lifespan within the DC collection system of wind farms. To clearly quantify the dominant role of the SOC distribution and charging–discharging power in lifespan degradation, and avoid obscuring key mechanisms caused by the coupling of multiple factors (e.g., temperature), this model assumes that the energy storage system is equipped with an ideal thermal management system.

3.1.3. Objective Function of the BESS Economic Model

To comprehensively evaluate the economics of the BESS configuration, this paper selects two key indicators as optimization objectives: the Life Cycle Cost (LCC) and the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE). The LCC reflects all investment costs of the BESS over its project cycle, while the LCOE measures the techno-economic performance under different configurations [13]. The combination of both achieves a balance between investment feasibility and operational economy over a long time scale.

- LCC

The LCC is the sum of all expenses of the BESS over the entire project cycle Y (typically 20 years), including the initial investment cost Cinv, operation and maintenance cost COM, replacement cost CR, and recycling cost Crec [24]. The calculation formula is as follows:

where Pb is the rated power of the BESS, UE and UP are the unit energy capacity cost and unit power cost of the BESS, respectively, UOM,E and UOM,P are the unit energy maintenance cost and unit power maintenance cost of the BESS, respectively, y (1, 2, 3, …, Y) is the operating year of the BESS, r is the discount rate, Crep is the unit capacity battery procurement cost, k is the number of battery replacements, Nch is the battery replacement count, is the recovery factor, and Ctotal is the total cost over the entire life cycle of the BESS system.

- 2.

- LCOE

The LCOE represents the levelized cost of the BESS, calculated by normalizing the costs and electricity generation of the BESS over its entire life cycle. The calculation formula is as follows:

where Etotal is the present value of the total power generation over the entire life cycle of the BESS system, and E(y) is the power generation of the BESS in year y.

3.1.4. Constraints of the BESS Economic Model

The following constraints related to its charge–discharge power, SOC, and service life must be considered during BESS operation:

where SOCmax and SOCmin are the upper and lower limits of the BESS SOC, and Pc_max and Pd_max are the maximum allowable charge and discharge power of the BESS, respectively.

3.2. Reliability Evaluation Model for the DC Collection System of Wind Farms with a BESS

To quantify the improvement in system reliability achieved by BESS configuration, it is essential to fully account for the randomness and time-series characteristics of system operation, and to establish a reliability evaluation model that aligns with the operational behavior of the wind farm DC collection system.

3.2.1. Wind Turbine Output State Model

The first-order Markov chain (MC) is widely applied in wind speed prediction models because it preserves temporal correlations while significantly reducing modeling and simulation complexity. Considering that wind speed fluctuates frequently and exhibits strong randomness, directly constructing an MC based on wind speed would require a large number of discrete states to ensure accuracy. In contrast, the wind turbine output, after conversion via the turbine power–wind speed characteristic curve, can be described with fewer states, making it more suitable for representation by a finite-state MC. Therefore, this section combines K-means clustering analysis with an MC to construct the wind turbine output state model. The specific steps are as follows:

- Based on historical wind speed data, fit the scale parameter cw and shape parameter kw of the Weibull distribution [25], and generate an hourly wind speed time series that conforms to long-term statistical characteristics.

- Simulate a large amount of wind speed data using the Weibull distribution model.

- Convert the wind speed series into a wind turbine output series using the turbine power–wind speed characteristic curve.

- Set the initial number of clusters k = 2 and the maximum number of clusters Kmax. Apply the K-means clustering algorithm to cluster the wind turbine output series, dividing it into a finite set of output states.

- Calculate the silhouette coefficient (SC) for each k. A value closer to 1 indicates better clustering performance. Iteratively determine the optimal number of clusters kbest within Kmax.

- 6.

- Based on the clustered output states, calculate the transition probabilities between all states to establish the Markov chain transition probability matrix P describing the wind turbine output states.

3.2.2. Equipment Outage Model for the Wind Farm DC Collection System

This paper employs the classic two-state outage model (normal and fault) to describe the basic components of the system. Assuming that the component’s normal operation time τ1 and fault repair time 2 follow exponential distributions, cycling through sampling 1 and 2 can generate long-term time-scale sequences of equipment operating states [7].

where TMTTF is the Mean Time To Failure, TMTTR is the Mean Time to Repair, and and are random numbers uniformly distributed on [0, 1].

Based on the component-level outage model, the outage model for key equipment (such as DC wind turbine units, DC/DC converters, DC circuit breakers, etc.) is further constructed according to the series or parallel logic structure of their internal components [26].

First, the failure rate λi and repair rate μi for each component i are calculated based on the equipment’s TMTTF and TMTTR using the following formulas:

Then, based on the series or parallel structure of the equipment’s components, the reliability parameters of the equipment are calculated using the corresponding Formulas (12) and (13):

where λ and μ are the equivalent failure rate and repair rate of the equipment, respectively, and m is the number of components constituting the current equipment.

3.2.3. Equipment Reliability Model Considering Weather Factors

To avoid the long-term assessment results being overly optimistic, the impact of weather on the failure rate is considered. According to standards such as IEEE Standard 346, the actual climatic impact on the operation of power components can be classified into three levels, normal, adverse, and disastrous, with corresponding occurrence probabilities of 0.88, 0.1175, and 0.0025, respectively [27]. It is assumed that the duration of each weather level follows an exponential distribution [28]. The influence coefficients of the three climatic states on the equipment failure rate, denoted as Qt, are set to 1, 1.2, and 2, respectively. The weather-factor-corrected equipment reliability model is then given as follows:

where λw and μw are the equivalent failure rate and repair rate of the equipment considering weather factors, respectively.

3.2.4. Reliability Evaluation Based on Sequential Monte Carlo Simulation and Its Process

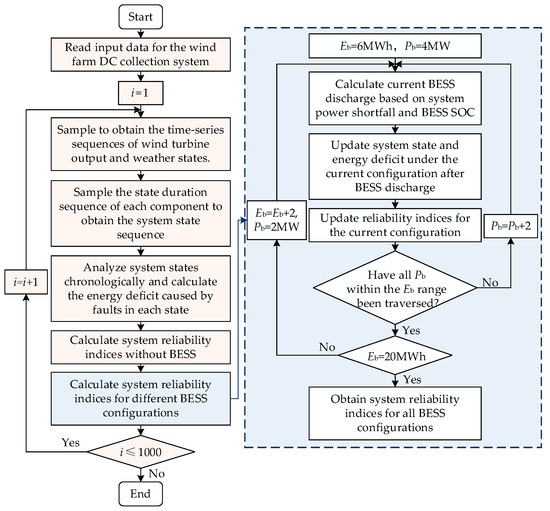

As an energy-limited component, the SOC of a BESS at any instant is highly dependent on its historical charge–discharge process, exhibiting a strong temporal correlation. Given the extremely low failure rate of BESS batteries, it is assumed that no random failure occurs before the end of its service life [29]. Therefore, the sequential Monte Carlo method is employed to simulate the time-series operating states of the system integrated with the BESS. The evaluation procedure is shown in Figure 2, and the core steps are as follows:

Figure 2.

Reliability assessment process for wind farm DC collection systems with a BESS.

- Input data related to the wind farm DC collection system (including number of wind turbines, turbine rated power, equipment reliability parameters, etc.), and set the simulation years to 1000 years.

- Initialize the simulation year counter i.

- Establish a wind turbine output state model. Then, based on the wind turbine output states and weather distribution probabilities, sample to obtain the time-series sequences of wind turbine output and weather states.

- Establish a weather-dependent equipment outage probability model. Sample to obtain the state duration times of each device in the system, and then merge them to form the system’s state duration sequence.

- Analyze the system state in chronological order and calculate the energy not supplied due to faults under different system states.

- Calculate the system reliability indices without a BESS.

- Calculate the system reliability indices under different BESS configurations. The specific steps are shown in the blue section on the right side of Figure 2:

- ①

- Set the initial rated energy capacity and power of the BESS as follows: Eb = 6 MWh and Pb = 4 MW.

- ②

- Calculate the current discharge power of the BESS based on the system’s power deficit caused by faults at the current time and the SOC of the BESS.

- ③

- After BESS discharge, update the system state and its energy not supplied situation under the current BESS configuration.

- ④

- Update the reliability indices under the current configuration.

- ⑤

- Determine if all allowable Pb values within the current range of Eb have been traversed. If yes, proceed to the next step; if not, update Pb.

- ⑥

- Determine if the current BESS configuration has reached the maximum value set for the Eb range. If yes, proceed to step ⑦; if not, update Eb and Pb.

- ⑦

- Update the system reliability indices under different BESS configurations for the current simulation year.

- Check if the simulation year count is less than the set simulation years. If yes, go to step 3; otherwise, end the loop.

3.2.5. System Reliability Objective Functions

To comprehensively evaluate the improvement in system reliability brought by the BESS, a complementary set of indicators is required. While the Expectation of Fault Blocked Power (EFBP) [8] can intuitively reflect the energy loss caused by faults, it cannot characterize the duration and frequency of power outages. Therefore, this paper combines the EFBP with the Average Service Availability Index (ASAI) to jointly form the reliability evaluation objectives, comprehensively measuring the system reliability level from both the energy and time dimensions.

- Expectation of Fault Blocked Power (EFBP)

The EFBP represents the expected value of the electrical energy that the system is unable to deliver to the grid connection point within a specified period (typically one year) due to equipment failures. This indicator is calculated based on the time-series sequence of system states obtained from sequential Monte Carlo simulation. The calculation method is as follows:

where Ns denotes the number of simulation years, and ei represents the expected energy not supplied in the i-th year.

- 2.

- Average Service Availability Index (ASAI)

The ASAI indicates the system’s ability to maintain normal power supply over a specified duration. It is defined as the ratio of the duration during which the system is unaffected by faults to the total required power supply duration. This indicator focuses on evaluating power supply continuity from the time dimension. Its calculation formula is as follows:

where ti is the duration of the system’s normal output state i, and R is the set of system states without faults.

3.2.6. System Reliability Constraints

- Power Balance Constraint of the Power System

In the DC collection system for wind farms, the active power delivered to the grid connection point at any time must be supported by the combined output of the wind turbines and the discharge power of the BESS. The balance relationship is as follows:

where Ps(t) is the total power delivered by the wind farm DC collection system at time t, and Pw(t) is the output power of the wind turbine units at time t.

- 2.

- Wind Turbine Unit Operation Constraint

The output power of wind turbine units is limited by their physical characteristics and wind speed, and must satisfy the following:

where Pw,max denotes the maximum output power of the wind turbine unit.

4. Solution of the Multi-Objective Optimal Configuration Model for a BESS

The BESS multi-objective optimal configuration model constructed in this paper aims to minimize the EFBP, LCC, and LCOE, while maximizing the ASAI. Due to the inherent conflicts and constraints among these optimization objectives, the Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO) algorithm is employed to solve the Pareto front of the model. Furthermore, to address the limitation that the Pareto front cannot provide a unique engineering solution, this paper integrates the CRITIC weighting method with the MARCOS comprehensive evaluation method for integrated decision-making to obtain the optimal BESS configuration scheme.

4.1. Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm

To balance multiple conflicting objectives, the MOPSO algorithm introduces an external archive and Pareto dominance relations to solve for the Pareto front, which represents the best trade-offs among different objectives. This front consists of a series of non-dominated solutions, where further optimization of any single objective can only be achieved at the expense of degrading others.

In this study, each particle represents a BESS configuration scheme. The particle position x denotes the specific values of the solution, and the velocity v controls the search direction and step size. The algorithm iteratively updates the particle positions and velocities to gradually approach the Pareto optimal solution set. The update strategies for v and x of particle p at the d-th iteration are as follows:

where denotes the inertia weight, c1 and c2 represent the individual and global best acceleration factors, respectively, r1 and r2 are random numbers between [0, 1], denotes the individual best position of particle p at the d-th iteration, and represents the best position found by all particles up to the d-th iteration.

4.2. Multi-Objective Decision-Making Method

Since the solution set of the Pareto front possesses the characteristic of being non-dominated, with each scheme emphasizing different objectives, it is difficult to judge their superiority directly. Moreover, significant intrinsic correlations exist among the indicators; direct scheme selection would lead to insufficient objectivity of the results.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes an integrated decision-making method combining the Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation (CRITIC) objective weighting method and the Measurement of Alternatives and Ranking according to Compromise Solution (MARCOS) method—termed the CRITIC-MARCOS method. This approach leverages the advantages of both algorithms: the CRITIC method objectively calculates weights by quantifying the volatility and conflicting nature of each indicator’s data, effectively mitigating the impact of indicator correlations on the objectivity of evaluation results [30]. Subsequently, the weights derived from the CRITIC method are incorporated into the MARCOS method, which achieves a comprehensive ranking of alternatives by calculating their relative closeness to the ideal and anti-ideal solutions [31]. The specific steps of the CRITIC-MARCOS method are as follows:

- Construct Decision Matrix and Standardization

An initial m × n decision matrix X is constructed with the m schemes from the Pareto front as rows and the n indicators as columns.

where xij represents the data of the j-th performance indicator for the i-th BESS scheme.

The benefit-type indicators B (a larger indicator value is better) and cost-type indicators C (a smaller indicator value is better) are standardized using the following processing, obtaining the standardized indicator data and the standardized matrix .

- 2.

- Indicator Variability Analysis

The standard deviation δj is used to represent the difference and fluctuation of values within each indicator in the CRITIC method.

where is the mean value of the j-th indicator.

- 3.

- Indicator Conflict Analysis

The correlation coefficient rjk is used to represent the correlation between indicator j and indicator k. Conflict reflects the degree of correlation between different indicators; if a significant positive correlation is present, the conflict value is smaller.

- 4.

- Calculate Weight Values

The amount of information Cj for each indicator is calculated based on δj and rjk. A larger Cj implies the indicator contains more information and should be assigned a greater weight.

- 5.

- Establish Extended Matrix

The positive ideal solution (AI) and the negative ideal solution (AAI) are introduced into matrix to form the normalized decision matrix Xk.

Based on the indicator type, AAI and AI are defined by Equations (28) and (29).

- 6.

- Determine Weighted Normalized Decision Matrix

Xk is multiplied by the weight vector to obtain the weighted normalized decision matrix .

- 7.

- Calculate Utility Degrees

The utility degrees and of alternative Ki are calculated relative to the positive and negative ideal solutions.

where Si, Sai, and Saai represent the sum of elements in the i-th, ai-th, and aai-th rows of the weighted matrix V, respectively.

- 8.

- Determine Utility Function for Alternatives

The utility function represents the distance of an alternative relative to the positive and negative ideal solutions. The best alternative is characterized by being the closest to the positive ideal solution while simultaneously being the farthest from the negative ideal solution. The calculation of the utility function is shown in Equation (33).

where and are the utility functions related to the ideal and negative ideal solutions, respectively.

Finally, the Pareto front solutions based on the utility function values are ranked; the solution with the highest utility value is the optimal configuration scheme.

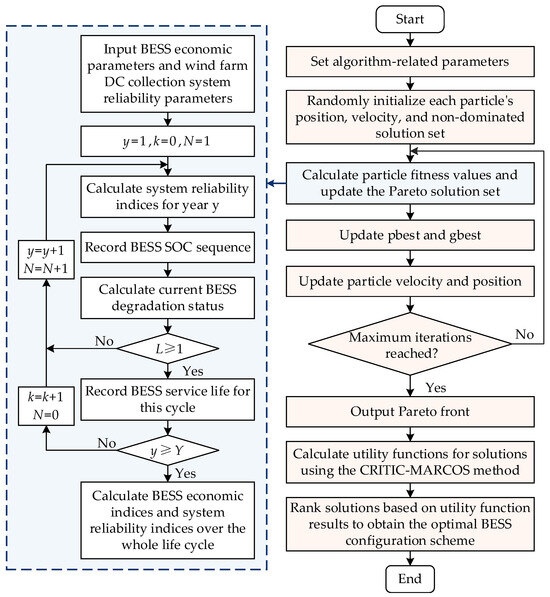

4.3. Algorithm Flow

The solution process for the BESS configuration in the wind farm DC collection system in this paper is shown in Figure 3, with the specific steps as follows:

Figure 3.

BESS optimization configuration solution process for wind farm DC collection systems.

- Set the algorithm parameters (including population size, particle dimension, iteration count, archive size, etc.).

- Initialize the position, velocity, and non-dominated solution set for each particle.

- Calculate the fitness value of each particle by integrating the BESS economics and system reliability evaluation process, and update the Pareto solution set based on the dominance principle.

- Update the personal best value and the global best value.

- Update the particle velocity and position according to Equations (18) and (19).

- Check if the iteration count is met. If yes, output the Pareto front; otherwise, return to step 3.

- Use the CRITIC-MARCOS method to calculate the utility function for each scheme in the Pareto front solution set.

- Rank the schemes according to the utility function results and select the optimal BESS configuration scheme.

This BESS configuration method considers the impact of service life on BESS cost during actual operation. Considering that its life degradation accumulates over the operation process, it is necessary to dynamically analyze the changes in BESS configuration and economic costs. Therefore, during the optimization iteration process, the degradation coefficient of the BESS is calculated annually, as shown in the sub-process within the blue section on the left side of Figure 3, with the following steps:

- Input the economic parameters of the BESS and the reliability parameters of the wind farm DC collection system without the BESS.

- Initialize the simulation year y, the BESS replacement count k, and the BESS service life N.

- Calculate and update the system reliability indices for year y.

- Record the SOC sequence of the BESS during its operation.

- Calculate the current degradation coefficient L of the BESS battery based on the throughput method.

- Check if the BESS service life degradation coefficient L has reached the upper limit. If L ≥ 1, replace the BESS battery, reset L = 0, and update k = k + 1.

- Record the service life N of the BESS for this cycle.

- Check if the current simulation year has reached the BESS system project cycle duration Y. If yes, output the BESS economic indicators and system reliability indicators over the entire life cycle; otherwise, update y, k, and N, return to step 3, and enter the next cycle.

5. Case Analysis

To verify the effectiveness and engineering applicability of the proposed BESS configuration optimization model and solution method, a case study is conducted based on a wind farm DC collection system with an installed capacity of 100 MW and a voltage rating of ±30 kV. First, the basic parameters of the BESS and the system are described. Next, the influence of the BESS configuration scale is quantitatively analyzed from three dimensions: BESS lifespan, economics, and system reliability. Finally, the MOPSO algorithm and the CRITIC-MARCOS integrated decision-making method are employed to solve for the optimal BESS configuration scheme that balances economy and reliability. The superiority of the proposed method in resolving multi-objective conflicts is demonstrated through comparison with single-objective optimization results.

5.1. Case Study Parameters

The wind farm DC collection system adopts a parallel topology. Twenty wind turbines, each with a unit capacity of 5 MW, are divided into four clusters, with five turbines per cluster. The reliability parameters of key equipment within the system are listed in Table 1 [4,7,26,32].

Table 1.

Reliability parameters of key equipment in wind farm DC collection systems.

The BESS employs Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries, known for their mature technology and cost-effectiveness. Relevant parameters are listed in Table 2 [24], and the relationship between the DoD and equivalent cycle life is shown in Table 3 [33]. To avoid additional aging caused by temperature fluctuations, this paper assumes an ideal thermal management system that can stabilize the operating temperature of the battery within the optimal range of 25 ± 5 °C.

Table 2.

LiFePO4 battery parameters.

Table 3.

Equivalent cycle life of a BESS at different depths of discharge.

5.2. Wind Turbine Output State Modeling Process and Results

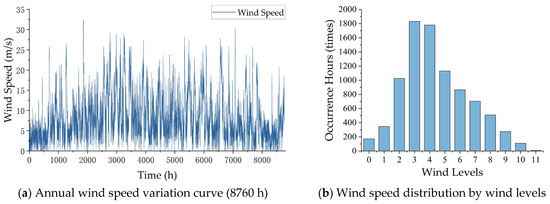

To accurately characterize the wind turbine output characteristics, this section selects the full-year historical wind speed data (totaling 8760 hourly samples) from a wind farm in Northwest China as the foundational dataset for constructing the wind speed model and the wind turbine output state model.

5.2.1. Wind Speed Data Generation and Fitting Based on Weibull Distribution

As shown in Figure 4, the wind conditions in the region where the wind farm is located are complex, encompassing various typical states such as calm and stormy winds. Fitting the historical wind speed data of the wind farm using MATLAB R2018b software yields the scale parameter and shape parameter of the Weibull distribution as 8.4068 and 1.5044, respectively. Therefore, the wind speed expression is as follows:

where F is a random number uniformly distributed over [0, 1].

Figure 4.

Annual wind speed analysis.

The annual wind speed series is simulated based on Equation (39). The resulting temporal variation curve of the simulated wind speed is shown in Figure 4a; the distribution of this simulated wind speed series within the 0~11 wind scale interval (corresponding to a wind speed range of 0~36.9 m/s) is shown in Figure 4b.

5.2.2. Wind Turbine Output State Results Based on K-Means and Markov Chain

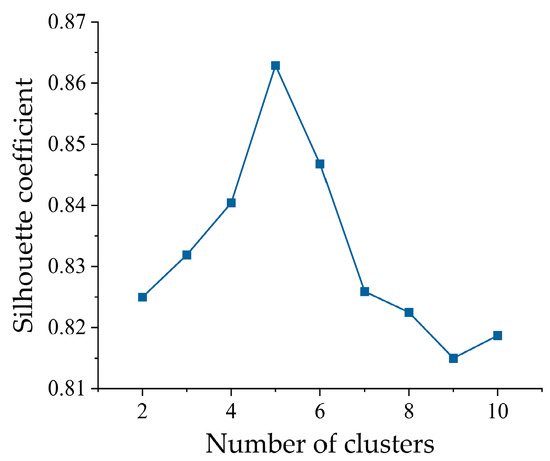

The corresponding output power of the wind turbines is calculated based on the Weibull-simulated wind speed series, and the output results are clustered. The results are shown in Figure 5:

Figure 5.

SC values under different cluster numbers.

As can be seen from Figure 5, when the number of wind power clusters is five, the SC value is the highest at 0.8629, indicating the best clustering effect under this condition. Therefore, k = 5 is selected as the optimal number of clusters. The power cluster centers and the corresponding state probabilities for a single 5 MW wind turbine at this point are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Clustering results of output power for a single wind turbine.

Based on the clustering results, the system state transition probability matrix P is obtained using the MC, as shown in Equation (40):

5.3. Analysis of the Impact of BESS Configuration on Its Lifespan and Economics

To clarify the necessity of introducing dynamic lifespan parameters into the economic model, this section quantitatively analyzes the impact of different power and capacity configurations on the actual service life of the BESS based on an SOC-dependent BESS lifespan model, and further evaluates their effects on the LCC and LCOE.

5.3.1. Impact of BESS Configuration on Lifespan

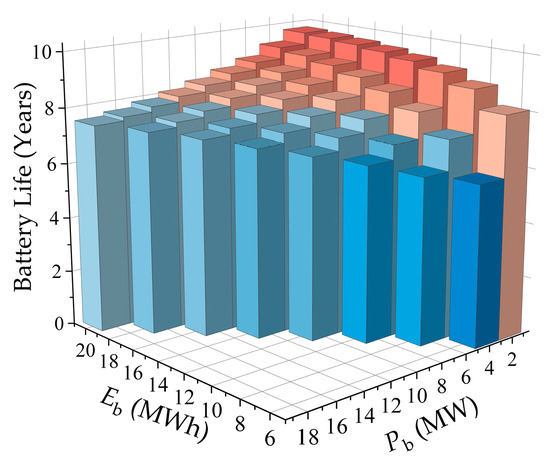

Based on the BESS lifespan model considering SOC influence constructed in this paper, the impact of different power and capacity configurations on BESS service life was analyzed. The results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

BESS lifespan under different configurations.

Analysis of Figure 6 shows that the BESS service life is closely related to its configuration scale. When Pb is constant and Eb decreases, the lifespan generally shows a declining trend. For example, when Pb = 4 MW, its service life decreases from 9.27 years to 5.88 years as Eb decreases. The main reasons are twofold: firstly, a reduction in Eb lowers Ethrough (total throughput energy), and secondly, a smaller Eb implies deeper discharge depths and more frequent operation at a low SOC, which, according to Equation (4), significantly increases the life degradation rate.

Similarly, when Eb is constant, the service life decreases as Pb increases. For instance, when Eb = 18 MWh, the lifespan decreases from 9.73 years to 7.39 years as Pb increases. This is because an increase in Pb not only enhances the energy throughput capacity per unit time but may also lead to more frequent operation in the low SOC range during charging and discharging, accelerating life degradation. These results verify the necessity of embedding a dynamic lifespan model into the optimization framework: BESS service life is not fixed but is closely related to its configuration scale.

5.3.2. Impact of BESS Configuration on Economics

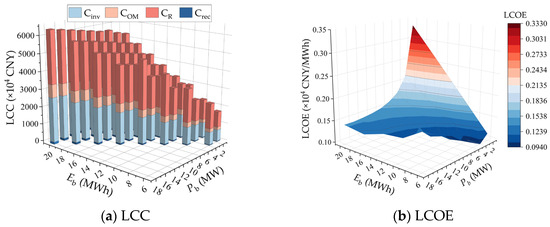

Building on the above research, the impact of configuration on the LCC and LCOE is further analyzed, with results shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Economic performance metrics for different BESS configurations.

Figure 7 shows the LCC and LCOE results for BESS operation under different configurations. It can be observed that the LCC of the BESS generally increases with the size of the BESS configuration, while the LCOE increases as the ratio of Eb to Pb decreases. The overall trends for both are relatively smooth, but when BESS life degradation is severe, both the replacement cost and the LCOE show significant increases. When the BESS configuration is 6 MW/8 MWh, the service life is only 5.88 years. Ignoring life degradation would underestimate the LCC by 622.21 million RMB and the LCOE by 14.73%. This indicates that the relationship between configuration scale and service life should be fully considered in the economic optimization of BESS configuration.

5.4. Analysis of the Impact of BESS Configuration on the Reliability of the Wind Farm DC Collection System

To validate that the saturation trend of reliability improvement is primarily determined by the inherent physical characteristics of the BESS configuration and remains relatively independent of variations in external environmental conditions, this paper defines three typical simulation scenarios. These scenarios are designed to analyze the consistency and differences in the impact of the BESS configuration on reliability and economy under different assumptions:

Scenario 1 (baseline scenario, without wind speed variation or weather influence): Wind turbines are assumed to operate at a constant power output (50% of rated power), and the failure rates of all equipment remain at the nominal values listed in Table 1.

Scenario 2 (considering wind speed variation, but not weather influence): The wind turbine output power is calculated based on wind speed time-series data generated from a Weibull distribution, while equipment failure rates remain constant.

Scenario 3 (considering both wind speed variation and weather influence): Building upon Scenario 2, the weather influence coefficient Qt is introduced to dynamically adjust the equipment failure rates.

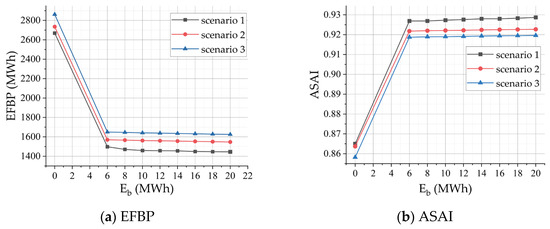

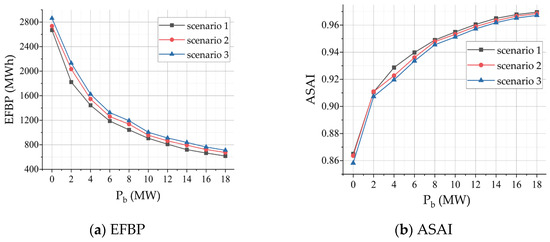

Simulations are conducted under these three scenarios to analyze the influence on the reliability indices EFBP and ASAI, for cases where Pb is held constant while Eb varies, and where Eb is held constant while Pb varies, respectively.

5.4.1. Impact of BESS Rated Capacity on System Reliability

Taking a BESS with Pb = 4 MW as an example, the impact of the BESS capacity configuration on system reliability under the three scenarios is analyzed. As shown in Figure 8, the improvement trends of the reliability indicators follow the same pattern across all three scenarios. As Eb increases to 6 MWh, the system reliability indicators show significant improvement: across the three scenarios, the EFBP indicator decreases by an average of 1182.76 MWh, and the ASAI indicator increases by an average of 0.0601. This indicates that within this capacity range, the BESS plays a significant role in improving system reliability. However, with a further increase in Eb, the improvement in system reliability indicators shows obvious saturation. Under the three scenarios, the EFBP stabilizes at 1445.7 MWh, 1546.9 MWh, and 1625 MWh, respectively, while the ASAI stabilizes at 0.9287, 0.9227, and 0.9196, respectively. This is because, in these scenarios, the rated power Pb is relatively small, and the amount of energy that the energy storage system can supplement to the system per unit time has also reached its limit.

Figure 8.

System reliability metrics vs. BESS capacity curve.

5.4.2. Impact of BESS Rated Power on System Reliability

The ability of the BESS to improve reliability is limited not only by its capacity but also by its rated power. The experiment in Figure 9 simulates the reliability of the wind farm DC collection system under the three scenarios, with Eb held constant at 20 MWh while Pb is varied.

Figure 9.

System reliability metrics vs. BESS power curve.

As the energy storage rated power Pb increases to 18 MW, the EFBP decreases by an average of 2087.10 MWh, and the ASAI increases by an average of 0.1061 across the three scenarios. The simulation results in Figure 9 are similar to those in Figure 8: the improvement trends of the reliability indicators are consistent across all three scenarios, and a saturation trend in reliability enhancement is also observed. However, both the rate and extent of saturation are significantly less pronounced than in Figure 8. This is because a larger Pb not only allows for more energy to be provided per unit time but also shortens the charging time during fault periods. Nonetheless, as Pb increases, the magnitude of power deficits in the system that exceed Pb continuously decreases. Consequently, the improvement effect on reliability indicators gradually diminishes, and the rate of change of the curves slows down.

Based on the comprehensive multi-scenario comparative analysis, it is evident that, regardless of variations in external environmental stresses, increases in BESS capacity and power consistently improve system reliability, and all exhibit a distinct saturation characteristic. Therefore, when planning BESS configuration, the marginal benefits of reliability should be considered to achieve an optimal balance between reliable system operation and economic efficiency.

Given that Scenario 3 simulates the most stringent operating conditions, performing optimal configuration based on the evaluation results from this scenario can prevent the planning scheme from being overly idealistic. Thus, the subsequent optimization and decision analysis in this section are all based on the evaluation results from Scenario 3.

5.5. Analysis of BESS Optimal Configuration, Balancing BESS Economics and System Reliability

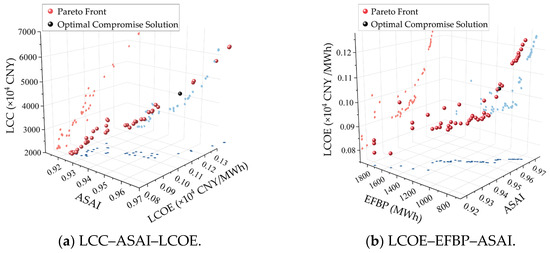

Based on the solution obtained by the MOPSO algorithm, the Pareto front across the four dimensions of the EFBP, ASAI, LCC, and LCOE was obtained, as shown in Figure 10. The four-dimensional Pareto front is decomposed into two three-dimensional fronts for display, and the solution set is projected onto three planes to reflect the relationship between the two indicators belonging to each plane.

Figure 10.

Pareto frontier results of multi-objective optimization.

It can be seen from Figure 10 that the system reliability increases with rising BESS cost, showing a gradual saturation trend. Consistent with the conclusion in Section 5.3, because the energy deficit of the system within a certain period is limited, continuously increasing the BESS configuration can improve system reliability, but the result is excessively high economic costs.

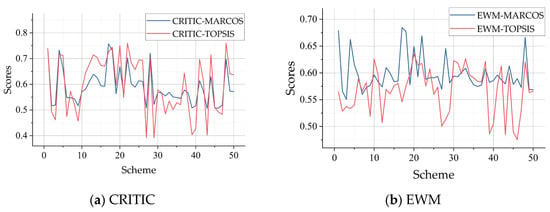

To determine the optimal compromise solution from the Pareto front, this paper employs the CRITIC-MARCOS method to rank the 50 non-dominated solutions. The obtained optimal compromise solution is illustrated in Figure 10. To verify the effectiveness and practicality of the CRITIC-MARCOS method for multi-objective decision-making in energy storage, a comparison is made with the EWM-TOPSIS method from reference [13]. The following two comparative analyses are designed: Figure 11a compares the ranking results of MARCOS and TOPSIS under CRITIC weighting, and Figure 11b compares the ranking results of MARCOS and TOPSIS under EWM weighting.

Figure 11.

Comparison of MARCOS and TOPSIS evaluation results.

Figure 11a shows that the scoring trends of CRITIC-MARCOS and TOPSIS are largely consistent, indicating the good validity and reliability of this method. In contrast, Figure 11b reveals more significant discrepancies between the trends of the two curves under EWM weighting, and the fluctuations in the TOPSIS results are notably greater than those of MARCOS under both weighting schemes. This is primarily attributed to two reasons: Firstly, regarding the weighting method, EWM relies solely on the degree of indicator variation without considering inter-indicator correlations, making it more sensitive to the decision model. In contrast, the CRITIC method, which measures both variability and conflict, yields more robust weights. Secondly, at the evaluation algorithm level, TOPSIS calculates based on Euclidean distance and is sensitive to linear weight superposition, whereas MARCOS synthesizes positive and negative ideal solutions through a nonlinear utility function. Consequently, MARCOS’s nonlinear evaluation mechanism is better suited for handling complex trade-off relationships such as “economy–reliability.” Therefore, the CRITIC-MARCOS method demonstrates stronger adaptability and decision-making advantages when solving multi-objective configuration problems for energy storage in wind farms.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, the optimal compromise solution selected from the Pareto front is defined as Configuration Scheme 1; the optimal decision point considering only the reliability indices EFBP and ASAI was selected as Configuration Scheme 2; and the optimal decision point considering only the economic indices LCC and LCOE was selected as Configuration Scheme 3. The calculated indicator results for the three configuration schemes are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Performance metrics for three configuration schemes.

The comparison reveals that, relative to the extreme alternatives, Scheme 1 achieves an excellent balance. Compared to Scheme 2, it secures significant economic benefits, including a 32.10% reduction in the LCC and an 25% reduction in the LCOE, with only a minor compromise in reliability: a 0.0127 decrease in the ASAI and a 187.33 MWh increase in the EFBP. Compared with Scheme 3, at the cost of an increase of CNY 1989.36 × 104 in the LCC and 0.0216 × 104 CNY/MWh in the LCOE, Scheme 1 achieves a significant improvement in reliability: a 41.05% reduction in the EFBP and a 4.13% increase in the ASAI. These results fully validate that the proposed optimization model and decision-making method can effectively guide planners in identifying the optimal trade-off between economic viability and reliability for BESS configuration in wind farm DC collection systems.

6. Conclusions and Recommendation

6.1. Conclusions

Aiming at the lack of systematic methods for enhancing operational reliability in wind farm DC collection systems through BESS configuration, this paper proposes a multi-objective optimization configuration method that accounts for the dynamic lifespan of the BESS and employs the CRITIC-MARCOS integrated decision-making framework for scheme selection. The following conclusions are drawn:

- The BESS can significantly improve the reliability of the wind farm DC collection system. However, the enhancement capability saturates when the rated capacity and rated power of the BESS increase beyond a certain threshold.

- Degradation considering the State of Charge (SOC) factor during BESS operation significantly impacts its service life. The case study demonstrates that under an unreasonable configuration (e.g., 4 MW/6 MWh), the BESS lifespan attenuation can reach 34.76%. Therefore, the optimization model considering BESS lifespan can prevent overly optimistic economic costs in planning results.

- The multi-objective optimization model and the CRITIC-MARCOS integrated decision-making framework constructed in this paper exhibit good feasibility and effectiveness. The MOPSO algorithm can effectively solve the Pareto front for economy and reliability, while the CRITIC-MARCOS method enables objective and comprehensive ranking of non-dominated solutions, providing an optimal scheme with both a theoretical foundation and practical value for engineering applications.

6.2. Recommendation

The method proposed in this paper provides a practical decision-making approach for BESS optimal configuration in wind farm DC collection systems, balancing economic cost and operational reliability. However, this study has certain limitations in model construction and solution methods, which warrant further deepening and extension. At the model level, the system reliability model does not account for the impact of temperature on the energy storage lifespan, and it has not yet covered scenarios of sustained faults and multi-equipment cascading failures triggered by extreme weather. There is room for improvement in characterizing system resilience [34]. Regarding the solution algorithm, the convergence performance and Pareto front distribution quality of the employed Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO) algorithm are significantly influenced by the parameter settings when handling high-dimensional, non-convex optimization problems, making it prone to local optima. Although the CRITIC-MARCOS decision method offers the advantage of objective weighting, it is relatively sensitive to the normalization of indicator data, and its linear weighted aggregation approach struggles to fully capture the complex nonlinear trade-offs among indicators.

Future research can be conducted in the following directions: (1) The optimization objectives can be extended from steady-state reliability to system resilience, investigating the role of a BESS in supporting the rapid recovery of DC collection systems and maintaining power supply to critical loads. (2) Hybrid intelligent algorithms incorporating mechanisms such as multi-population strategies and scenario decomposition can be explored to enhance search efficiency in high-dimensional solution spaces and improve the quality of the Pareto front. (3) Improved evaluation methods combining fuzzy logic and dynamic weighting can be investigated to enhance the selection robustness of configuration schemes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F. and Y.H.; methodology, Y.H.; validation, Y.H.; formal analysis, Y.H.; investigation, Y.F. and X.B.; resources, Y.F.; data curation, Y.H. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.F. and X.B.; visualization, Y.H.; supervision, Y.F. and X.B.; project administration, Y.F.; funding acquisition, Y.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Tianshan Talent Training Program under 2022TSYCLJ0019 and the 2025 Xinjiang Autonomous Region Major Science and Technology Special Project under Grant 2025A01006.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Junyi Liu is employed by the company Shiyan Power Supply Company, State Grid Hubei Electric Power Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Bai, X.; Fan, Y.; Hou, J. Reliability assessment method of wind power DC transmission system based on level fault tree analysis. Energy 2025, 327, 136426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fan, Y.; Hou, J.; Bai, X. Reliability Evaluation of DC/DC Converter in Direct Current Collection System of Wind Farm Considering the Influence of Control Strategy. Processes 2023, 11, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, D.; Fan, Y.; Hou, J.; Lu, J.; Sun, Y.; Li, X. Bipolar DC/DC converter and short-circuit current limitation for DC-integrated wind farm transmission system. High Volt. Eng. 2025, 51, 605–618. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Fan, Y.; Lu, J.; Hou, J.; Wang, Y.; Bai, X. Optimal design method for topology of onshore wind power DC collection system. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2023, 47, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R.; Abeynayake, G.; Mu, Q.; Liang, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y. Reliability and economic evaluation of offshore wind power collection system based on universal generating function. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.; Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Reliability and economy assessment of offshore wind farms. J. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1554–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Fan, Y.; Hou, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J. Reliability evaluation of direct current gathering system in onshore wind farm based on reliability block diagram-sequential monte carlo. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 40, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fan, Y.; Bai, X.; Hong, Y. Reliability evaluation of DC collection system in wind farms based on FTA-NSMC method. Smart Power 2025, 53, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.; Pan, X.; Wu, F.; Xue, F.; Li, W.; Xie, D. Adequacy assessment for power systems with wind power and energy storage integration based on Well-Being theory. Power Syst. Technol. 2016, 40, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Jia, P.; Yue, Z.; Yao, M. Configuration planning and operation strategy of off-grid wind solar storage hybrid energy system based on hydrogen fuel energy storage. J. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2025, 31, 138–149. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.; Wang, W.; Li, P.; Zhang, J. Joint planning and configuration of wind-solar-storage capacity for large-scale renewable energy bases based on multi-objective optimization. Power Syst. Technol. 2025, 49, 4477–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Liu, F. Optimal configuration of energy storage in distribution feeders considering economy and reliability. Electr. Power Eng. Technol. 2024, 43, 56–66+87. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Liu, M.; Lin, S.; Li, L. Two-stage multi-strategy decision-making framework for capacity configuration optimization of grid-connected PV/battery/hydrogen integrated energy system. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112862. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Cheng, S.; Chen, C.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ghiasi, M. Modified Biogeography Optimization Strategy for Optimal Sizing and Performance of Battery Energy Storage System in Microgrid Considering Wind Energy Penetration. Batteries 2023, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Li, Z.; Tian, X.; Su, J.; Chang, X.; Xue, Y.; Li, Z.; Jin, X.; Wang, P.; Sun, H. A two-stage distributionally robust low-carbon operation method for antarctic unmanned observation station integrating virtual energy storage and hydrogen waste heat recovery. J. Apenergy 2025, 400, 126578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, S.O.; Tomomewo, O.S.; Mann, M.; Van der Watt, J.; Salehfar, H. Optimal Sizing and Techno-Economic Evaluation of a Utility-Scale Wind–Solar–Battery Hybrid Plant Considering Weather Uncertainties, as Well as Policy and Economic Incentives, Using Multi-Objective Optimization. Energies 2025, 18, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yuan, X.; Yu, Z.; Ge, L. Comments on power quality enhancement research for power grid by energy storage system. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2019, 43, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R.; Liang, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y. Overview of offshore wind power collection system. Electr. Power Constr. 2021, 42, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Fan, Y.; Hou, J.; Lu, J.; Xuan, D. Impedance modeling and small disturbance stability analysis of DC pooling wind power system. High Volt. Eng. 2025, 51, 1632–1644. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ding, Y. Wind power fluctuation smoothing control strategy based on improved adaptive wavelet packet. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 566–573. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Hou, X.; Li, D. Optimal economic planning method of energy storage system to improve grid reliability. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Cheng, J.; Li, X.; Yu, J. Research on optimization method of primary frequency regulation configuration of wind storage system considering discharge loss of energy storage. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2022, 43, 416–423. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, X.; Duan, J.; Xie, L. Economic dispatch model considering battery lifetime for microgrid. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2015, 35, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Economic Analysis of Wind Storage Based on the Trend of Energy Storage. Ph.D. Thesis, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, D.; Byalsky, M.; Yahalom, A. Valuation of Wind Energy Turbines Using Volatility of Wind and Price. Electronics 2021, 10, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Fan, Y.; Lu, J.; Hou, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. Reliability assessment method for the integrated DC/DC converter of boost full bridge isolated converter applicable to the DC collection system of wind farms. Power Syst. Technol. 2025, 49, 2928–2937. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J.; Feng, Z.; Ji, W.; Ye, X.; Huang, X. Evaluation of supply and demand fitness for highway self-consistent energy systems based on sequential Monte-Carlo. J. Chang. University. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2024, 44, 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Lin, S.; Qu, Y.; Yang, A.; Chang, J. Reliability assessment of wind turbine competing failures considering extreme weather shock process. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2024, 44, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jeng, S.-L.; Tan, C.M.; Chen, P.-C. Statistical distribution of lithium-ion batteries useful life and its application for battery pack reliability. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basílio, M.P.; Pereira, V.; Costa, H.G.; Santos, M.; Ghosh, A. A Systematic Review of the Applications of Multi-Criteria Decision Aid Methods (1977–2022). Electronics 2022, 11, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stević, Ž.; Pamučar, D.; Puška, A.; Chatterjee, P. Sustainable supplier selection in healthcare industries using a new MCDM method: Measurement of alternatives and ranking according to compromise solution (MARCOS). Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 140, 106231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Huang, M.; Qiang, D. Reliability modeling of battery energy storage system and its effect on the reliability of distribution system. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2013, 41, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, H. Intelligent Optimization and Predictive Control Technology. Ph.D. Thesis, Xiangtan University, Xiangtan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Xue, Y.; Li, Z.; Jin, X.; Wang, P. Resilience-Oriented Asynchronous Decentralized Restoration Considering Building and E-Bus Coresponse in Electricity-Transportation Networks. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 11701–11713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.