Abstract

This paper presents a computationally efficient two-stage analytical framework for predicting daylight performance in buildings. It is designed to support real-time applications in smart lighting and intelligent building management systems. This approach combines a facade lighting model—driven by solar geometry and atmospheric transmittance—with an interior light distribution module that represents the window as a discretized light source. This formulation provides a lightweight alternative to computationally intensive ray tracing methods. It allows rapid estimation of spatial lighting patterns with minimal input data. The framework is validated using a one-year measurement campaign with class A photometric sensors in three facade orientations. The facade module achieved an average relative error below 15%, while the interior lighting model yielded an RMSE of 83 lx (≈10% error). The integrated system demonstrated an overall average deviation of 18.6% under different sky and season conditions. Owing to its low computational complexity and physically transparent formulation, the proposed method is suitable for deployment in smart building platforms, including daylight-responsive lighting control, embedded energy management systems, and digital twins requiring fast and continuous simulation of daylight availability.

1. Introduction

Daylight availability is a key boundary condition influencing visual comfort, lighting energy demand [1,2,3,4], and operational performance in smart buildings [5]. As smart building systems are increasingly developed to rely on real-time sensing, predictive control, and simulation-based decision-making. For this purpose, fast and physically based daylight models are becoming essential components of daylight-responsive lighting, energy management, and intelligent building automation [5,6,7,8]. Conventional daylight simulation tools—such as Radiance, Daysim, or EnergyPlus [9]—provide high accuracy but are computationally intensive. These features limits their applicability in embedded controllers, digital twins, or continuous real-time operation [10,11].

Nowadays research has focused on simplified or reduced-order methods capable of estimating daylight availability with significantly lower computational effort [12]. Analytical and semi-empirical approaches offer promising alternatives. But many existing models need on complex sky formulations, require extensive parameterization, or lack a direct coupling between façade exposure and indoor light propagation. On the other hand, most lightweight daylight models have been developed primarily for design-stage evaluation. Their direct deployment in smart building platforms remains limited, as such applications require computationally inexpensive, deterministic, and on-device executable solutions. These limitations motivate the development of a computationally efficient daylight estimation method applicable to real-time building operation [9,13,14]. Such a model would provide a valuable analytical core for daylight-responsive control, indoor environmental monitoring, energy optimization, and predictive strategies implemented in IoT-based or embedded building systems [15,16]. Solar radiation reaching the Earth’s surface is the results of a complex chain of radiative interactions occurring as sunlight passes through the atmosphere. These include absorption by gases and aerosols, elastic and inelastic scattering mechanisms such as Rayleigh and Mie scattering [17]. At the surface level, solar radiation undergoes reflection, refraction, and transmission through dielectric materials such as glazing systems [18,19]. Together, these mechanisms determine the spectral distribution and intensity of daylight reaching building façades.

This study proposes a two-stage analytical framework that connects façade illuminance estimation with an indoor light-distribution model based on a discretized area-source formulation. The model is intentionally lightweight, enabling year-round simulations with high temporal resolution and minimal computational cost. The approach is experimentally validated through long-term measurements under real-sky conditions, achieving accuracy levels suitable for daylight-responsive lighting control.

1.1. Interaction of Solar Radiation with Buildings

The daylight transmission process begins in the atmosphere and continues as solar radiation enters the building envelope [20,21]. The passage is influenced by several architectural and material parameters. The orientation and dimensions of glazed openings need to be considered. The major orientation of windows (north, south, east, and west) determines the temporal distribution of direct solar gains throughout the day and year.

- Optical properties of glazing: The application of coatings, including low-emissivity coatings and reflective films, has been shown to modulate both visible light transmission and solar heat gain.

- Geometry and surface finishes: The distribution, reflection and attenuation of light within a given space are governed by factors including its internal layout, surface reflectivity and spatial configuration.

Together, these variables define the quantity, distribution and perceived quality of light in the indoor environment. They affect to visual comfort and functional performance.

The relevance of daylight modeling has been the subject of many studies in recent years. Strategic modeling of daylight distribution has been shown to serve several areas of building performance. The following key aspects highlight the multifaceted importance of this task.

These studies [15,16] examines the relationship between visual comfort and workplace lighting. Effective use of daylight has been shown to improve the quality of the work environment through the following mechanisms: the aim is to minimize visual fatigue, and increased concentration and productivity have been shown to be achieved, minimizing glare and high contrast zones is achieved by evenly distributing light spatially,

- Thermal comfort and energy consumption

Excessive solar gains can lead to overheating, increasing the need for cooling and reducing thermal comfort. Conversely, effective control of solar radiation—through shading systems, material selection and interior layout—can balance lighting and cooling requirements [22,23].

- Broader implications

Understanding the trajectory of sunlight, from its celestial origin to its manifestation in a given indoor environment, has implications that extend beyond the realm of architecture [8,15,24,25]. These include:

- Health and circadian regulation: The role of natural light in maintaining circadian rhythms is well documented and has a significant impact on mood, alertness, sleep quality, and overall well-being.

- Energy efficiency: Optimal design of daylighting systems has been shown to reduce the use of artificial lighting, thereby minimizing electricity consumption.

- Sustainability: Optimizing indoor daylighting conditions contributes to the integration of renewable energy strategies and supports environmental stewardship through passive design.

1.2. Motivation

The increasing emphasis on sustainable architecture and energy-efficient building operation has reinforced the need for accurate and physically grounded daylight modeling. Natural light directly affects visual comfort and task performance, while simultaneously reducing the demand for artificial lighting and overall building energy consumption. The primary motivation of this research is to develop a comprehensive daylight propagation model that represents the full optical pathway of sunlight—from its extraterrestrial origin, through atmospheric attenuation and façade transmission, to its spatial distribution within interior spaces.

The proposed framework enables the quantitative estimation of solar radiation incident on the building envelope and its subsequent propagation and attenuation inside rooms, providing a physically consistent basis for daylight-integrated building performance analysis. The overarching objective is to improve both energy efficiency and visual comfort by optimizing the interaction between natural and artificial lighting systems. Designed for broad applicability, the model can be applied across different climatic and geographical contexts and supports fast, computationally efficient daylight simulations suitable for real-time and control-oriented applications. This versatility supports its applicability in daylight-responsive lighting control, façade optimization, and building automation workflows.

2. Daylight Modeling Approaches in Buildings: A Review of Analytical and Data-Driven Methods

Currently, daylight distribution in buildings is modeled using a variety of approaches, including both specialized software tools and stand-alone algorithmic solutions. Each approach has its own advantages and limitations [6,15,26].

Specialized software [27] allows for fast and straightforward modeling of lighting conditions; however, it usually does not allow for easy generation of outputs suitable for subsequent algorithmic processing. In contrast, modeling with stand-alone algorithms is more complex due to the need to develop models independently. However, this method provides greater flexibility and easier exploitation of the results for various purposes, such as adaptive lighting control systems and related applications.

This section reviews representative techniques and methodological approaches used for daylight modeling in buildings.

The paper [28] presents a standardized daylight coefficient model (DDS) that unifies previous methods for dynamic simulations of building lighting. The proposed DDS format allows for efficient and accurate lighting simulations, especially under variable conditions, e.g., in urban environments or with different types of shading. The results show better performance compared to older methods (Daysim) and recommend DDS as a unified standard for daylight simulations.

The study [29] examines the daylight performance of office buildings with different atrium types, proportions (Well Index—WI) and roof opening designs (monitoring and horizontal skylights) to optimize energy efficiency. Climate-Based Daylight Modeling (CBDM) is applied in US Climate Zone 3 using spatial daylight autonomy (sDA) and annual solar exposure (ASE). The study validates the DIVA simulation tool through model comparisons and concludes that the Well Index effectively characterizes atrium proportions. The results provide architects with a database of atrium designs specific to daylight metrics and design parameters in US Climate Zone 3.

The paper [24] explores the integration of Building Information Modeling (BIM) with daylighting simulation tools to improve building performance analysis. It highlights how BIM, widely used in the AECO industry, can streamline the simulation process compared to traditional CAD-based workflows. The study focuses on the integration of daylighting analysis into BIM and presents a prototype that integrates Revit with Radiance and DAYSIM, discussing its development, validation, benefits, and challenges.

The study [30] proposes a novel AI-based method for real-time daylight analysis in buildings with different layouts. The development of a machine learning model to predict daylight performance was enabled by the definition of key design variables, with the useful daily illuminance (UDI) serving as the metric. Training and validation data generation was performed using the DIVA simulation tool for buildings in Ho Chi Minh City. The findings demonstrated a high degree of accuracy, highlighting the ability of the methodology to facilitate the creation of a versatile, data-driven framework for daylight analysis that is compatible with a variety of models and metrics.

The study [31] describe a new methodology for generating typical meteorological year (TMY) sets adapted for daylight modeling and climate-based building energy simulation (CBDM-BES). The use of Sandia’s method in conjunction with NSGA-II optimization is shown to improve energy prediction accuracy by minimizing the differences between predicted and actual energy consumption data over longer periods. As demonstrated in an application in Hong Kong, the method is effective in generating TMY sets that closely match actual energy consumption trends. Integrating this workflow into future parametric design processes has the potential to improve daylight energy performance analysis.

The study [32] provides a comprehensive overview of the evolution of light transmission algorithms used in daylight simulation tools. The current study proposes a chronological framework for the development of algorithms, identifies existing gaps in the field, and outlines promising future directions. In addition, an analysis of 50 common simulation tools is conducted, with an assessment covering algorithm type, accuracy, analytical capabilities, computation, software integration, and licensing. The aim of this study is to provide practitioners, especially those new to the field, with a deeper understanding and proficiency in the use of daylight simulation tools.

The paper [5] presents a comprehensive review of daylighting design in buildings, covering design principles, technologies, and evaluation methods. The study methodically compares a range of daylighting systems and prediction techniques, including scale models, full-scale field measurements, simulations, and manual calculations, highlighting their strengths, weaknesses, and limitations. Although simulations can provide accurate results, they require significant time and expertise to perform. The aim of this study was provided a framework to assist engineers, researchers, and designers in selecting appropriate daylighting strategies for different types of buildings to increase sustainability and reduce energy costs.

HVAC systems represent one of the major energy consumers in buildings, and their real-time operation and control have a decisive impact on overall energy efficiency. Modern buildings increasingly rely on building automation systems (BAS) and energy management control systems (EMCS), which enable supervisory and optimal control strategies to maintain comfort while minimizing energy use. As demonstrated in recent reviews [33], advanced control methods—often driven by predictive models and dynamic environmental data—play a central role in the broader development of intelligent and energy-aware building operation.

A recent study [34] has shown that Model Predictive Control (MPC), particularly when combined with weather forecasts, can substantially improve the energy efficiency of integrated room automation systems while maintaining thermal, air-quality, and lighting comfort. MPC-based controllers rely on dynamic building models and optimize HVAC, shading, and lighting actions in real time, often outperforming conventional rule-based strategies. These findings highlight the growing need for fast, reliable simulation models that can support predictive and stochastic control methods in smart building operation.

LED-based lighting systems are increasingly becoming the dominant technology in modern buildings due to their energy efficiency, long lifetime, and flexible tunability. Their adaptability enables advanced illumination control strategies, where lighting levels can be optimized in real time based on occupancy, daylight availability, and comfort requirements. Recent work [35] has demonstrated that intelligent LED control—supported by sensor arrays and daylight estimation—can significantly reduce power consumption while maintaining uniform illumination in occupied zones. These developments reinforce the need for fast and reliable daylight models that can support energy-aware lighting control in smart buildings.

Wireless, sensor-driven lighting systems are increasingly adopted as core infrastructure in intelligent buildings. By equipping each luminaire with embedded presence and light sensors and enabling wireless communication with a central controller, such systems support adaptive illumination control, indoor positioning, and data-driven analysis of building usage. Multivariable controllers use real-time occupancy and daylight measurements to dynamically adjust dimming levels, while sensor data streams enable additional services such as occupancy mapping and energy analytics. These developments reveal a strong dependence on accurate and fast daylight estimation, which forms a critical input for next-generation smart lighting and building automation platforms [36].

The study [37] demonstrate that energy-efficient smart LED lighting systems can significantly reduce power consumption while maintaining high levels of visual comfort. Modern implementations typically integrate wireless communication technologies such as ZigBee and Wi-Fi, enabling luminaires to adapt in real time to changing daylight levels, occupancy patterns, and user preferences. Sensor–actuator networks (WSANs) provide continuous measurements of environmental conditions and user interactions, allowing automated or hybrid control modes that optimize illumination and energy use. These developments reinforce the growing need for accurate, fast daylight-estimation models that can serve as core inputs for intelligent lighting control in commercial and residential smart buildings.

Smart cities rely on advanced information and communication technologies to optimize energy use across systems such as smart grids, smart buildings, and urban lighting. Effective energy management in these interconnected infrastructures requires accurate modeling of environmental variables, including lighting conditions, which directly affect comfort and operational efficiency. Recent research [38] has demonstrated that intelligent lighting-monitoring and control systems can significantly reduce energy consumption while maintaining acceptable illumination levels, highlighting the importance of fast, reliable models for integrating daylight information into urban-scale smart-building platforms.

Recent work [39] has explored the integration of lighting control with building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) to improve energy management in sustainable and smart buildings. By modeling the relationship between photovoltaic generation and lighting demand, these strategies dynamically adjust lighting loads to maintain visual comfort while responding to fluctuations in on-site energy production. Simulation studies demonstrate that such approaches can effectively regulate power consumption and illumination levels, highlighting the importance of accurate daylight and irradiance estimation as a foundation for next-generation energy-aware lighting systems.

The reviewed studies show that daylight modeling has evolved in several methodological directions, from high-precision ray tracing simulations to data-driven approaches, integrated BIM workflows, artificial intelligence techniques, and real-time control frameworks for smart buildings. Each method offers unique strengths and limitations, and no single approach can be considered universally optimal. The suitability of a particular technique depends on the modeling objective, the required accuracy, the computational budget, and the availability of environmental or geometric data. As a result, daylight modeling remains a broad and diverse research area, with individual contributions typically addressing specific challenges—from facade optimization at the design stage to predictive lighting control and energy-aware building operation. This diversity highlights the need for modeling approaches that balance physical consistency, computational efficiency, and applicability in different contexts of building performance and smart control.

Recent advances in daylight simulation have produced a range of physically based tools such as Radiance [40], Daysim [41], and EnergyPlus [42], which provide highly accurate results but require extensive computational effort and detailed input data.

Conversely, analytical and semi-empirical approaches (e.g., [14,43,44]) aim to simplify daylight prediction while maintaining sufficient physical accuracy for early-stage design.

Despite the availability of both simplified analytical approaches and high-fidelity ray-tracing tools, a practical gap remains between these two classes of daylight simulation methods. A significant number of approaches are focused on the utilization of complex sky models, which are hard to parameterize within operational settings. These models often show a lack of flexibility when it comes to different facade geometries or orientations. They are often deficient in establishing an explicit and unified coupling between exterior irradiance and interior light propagation.

To overcome these limitations, this study proposes a two-stage daylight simulation framework. In the initial phase, the facade illumination is determined for arbitrary surface orientation and slope using solar geometry and atmospheric transmittance models. In the second phase, the resulting luminous flux is propagated into the interior by representing the window as a discretized area light source. The overall formulation is intentionally lightweight and computationally efficient, making it suitable for management-oriented daylight analysis, rapid design iterations, and parametric optimization workflows.

Table 1 provides a brief overview of the most widely used daylight modeling approaches documented in the recent literature. The table offers a comprehensive analysis of these approaches, including their respective computational domains, validation strategies, and significant limitations. On the other hand, the proposed framework integrates year-round modeling at the facade level with spatial distribution of indoor light and empirical validation under real sky conditions. This achieves a balanced trade-off between prediction accuracy and computational efficiency.

Table 1.

Overview of representative daylight modeling approaches in recent research.

Compared to the literature reviewed, this study presents several distinct methodological contributions. It employs a two-stage analytical framework that directly links exterior façade lighting to interior light propagation through a unified physical formulation.

The model operates at hourly resolution throughout the year (8760 h). This resolution allows for weather-based daylight prediction without relying on pre-computed sky models or ray tracing tools. It provides empirical validation under real sky conditions for three façade orientations (east, south and west), demonstrating average errors in the range of 10–15% for the façades and approximately 10% for the interior workspace plane. This approach achieves high computational efficiency—a complete annual simulation is performed in less than one minute on a standard computer. During the computation, accuracy consistent with established simulation tools such as Radiance, Daysim or Dialux is maintained.

The modular structure of the model allows for direct integration into adaptive daylighting management and building performance optimization workflows. This concept combines analytical methods and data-driven design tools. Together, these features make the proposed framework a computationally efficient, physically sound, and experimentally validated alternative to conventional daylighting simulation methods.

3. Daylight Model Background

3.1. Solar Geometry Modeling

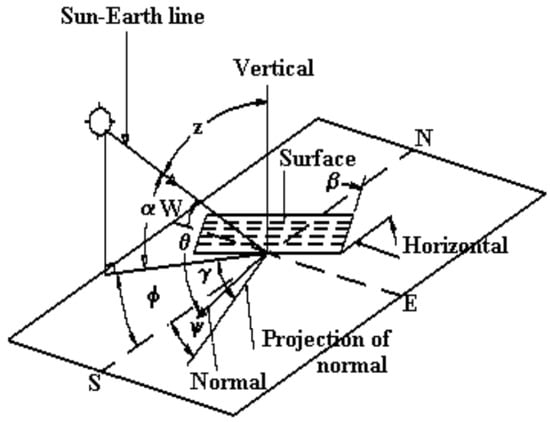

Accurate modeling of solar radiation incident on building envelopes depends on precise determination of the parameters of the sun’s position [45]. The geometric relationship between the Earth and the Sun determines the trajectory of the sun’s rays in the sky, which in turn affects the angular and temporal characteristics of the solar energy that falls on inclined surfaces (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Solar geometry [45].

This section outlines the basic geometric parameters [22,45,46,47,48] and their mathematical formulation for calculating the impact of solar radiation on building facades.

The following solar geometry parameters were used in the computational model:

Latitude (LAT)—The geographical latitude of the observation site, expressed in degrees. It defines the angular distance from the equator and directly influences the solar path across the sky.

Declination angle (δ)—The angular displacement of the Sun north or south of the celestial equator, which varies periodically due to the axial tilt and Earth’s orbit.

Solar altitude angle (α)—The angle between the Sun and the local horizon.

Zenith angle (z)—The complementary angle to the solar altitude, representing the angle between the Sun and the vertical direction.

Hour angle (h)—Represents the Sun’s angular displacement from the local meridian due to Earth’s rotation.

Solar azimuth angle (Φ)—The angle between true north and the horizontal projection of the Sun’s position.

Surface azimuth angle (ψ)—The azimuth orientation of the building surface, typically defined as 0° for north-facing, 90° for east, 180° for south, and 270° for west.

Surface tilt angle (β)—The inclination of the surface relative to the horizontal plane.

Angle of incidence (θ)—The angle between the incoming solar rays and the surface normal. It is a key determinant in calculating the effective irradiance on inclined surfaces and is calculated using (Equation (1)) [22,49]

This comprehensive formulation allows the determination of solar incidence angles on arbitrarily oriented and tilted surfaces throughout the entire year. The precision of these geometric inputs is critical for subsequent daylight modeling and energy performance evaluation.

The first stage of the proposed framework calculates the global façade illuminance based on the position of the sun, façade orientation, and atmospheric transmittance. The extraterrestrial illuminance (in lx) on a plane normal to the solar beam for day is obtained from (Equation (2)):

where represents the solar constant in photometric units, n is number of day.

This parameter corresponds to the extraterrestrial illuminance often denoted as in the literature [19,22].

3.2. Calculation of Global Irradiance Components

3.2.1. Atmospheric Transmittance

The reduction in solar irradiance due to the atmosphere is quantified by the beam transmittance and diffuse transmittance .

The Hottel model (1976) [50] is applied for the beam component, which provides robust empirical correlations as a function of altitude and zenith angle (Equation (3)):

where and are empirical coefficients determined by the site elevation (312 m above sea level).

For the diffuse component, the Liu–Jordan model (1960) [51] is employed, which assumes an isotropic sky luminance distribution (Equation (4)):

where is the diffuse-to-direct conversion factor depending on sky clarity (typically 0.1–0.3 under clear conditions).

Solar radiance incident on a building surface consists of three distinct components (Equation (5)): direct (beam), diffuse and reflected radiance. In order to accurately estimate the total global radiation on a sloped facade, it is necessary to quantify all three contributions based on the surface geometry and atmospheric transmittance characteristics.

This composite value defines the total illuminance (in lx) received by the façade at a given time and orientation. For the purposes of illuminance analysis and building performance modeling, irradiance in photometric units (lx) is preferred over radiometric units (W/m2) because it correlates directly with perceived luminance and visual comfort.

3.2.2. Beam Radiation (Direct Component)

This represents the solar radiation that reaches the surface without being scattered by the atmosphere. The beam irradiance on a tilted plane is calculated as follows (Equation (6)):

where is the extraterrestrial illuminance (lx), is the transmittance of the beam through the atmosphere (Hottel model [50]) (−) and is the angle of incidence of the sun on the surface (°).

3.2.3. Diffuse Radiation

The diffuse component results from scattering by air molecules, aerosols, and clouds. It is assumed to come from all directions in an isotropic manner. Diffuse radiation on an inclined plane is calculated using an isotropic sky model. Diffuse radiation on an inclined plane is calculated using an isotropic sky model (Equation (7)).

where —diffuse radiation on the horizontal plane (lx), is the extraterrestrial (non-surface) illuminance on the plane perpendicular to the sun’s rays on the nth day of the year (lx), —solar altitude (°), angle of inclination of the analyzed surface (°).

3.2.4. Reflected Radiation

Reflected radiation comes from solar energy that strikes the ground or surrounding objects and is then reflected towards the inclined surface. Reflected radiation originates from solar energy striking the ground or surrounding object and is then reflected towards the inclined surface. It is given by Equation (8):

where —reflected component of global solar radiation incident on an inclined surface (lx), —extraterrestrial illuminance on a perpendicular plane (from the previous formula) (lx), —height of the Sun above the horizon (°), —atmospheric transmittance for the direct component of solar radiation (−), —atmospheric transmittance for the diffuse component of radiation (−), —reflection factor (albedo) of the surrounding environment (−), —surface inclination to the horizontal (°).

3.3. Distribution of Light in Interior Spaces

The indoor illuminance model represents the second stage of the proposed daylight simulation framework. It calculates the distribution of illuminance on the working plane inside the reference room by propagating the transmitted façade flux through a discretized window area and accounting for first-order reflections from walls, floor, and ceiling surfaces. The formulation combines geometric optics with diffuse-reflectance theory to balance accuracy and computational simplicity.

3.3.1. Window as a Planar Lambertian Area Source

The transmitted luminous flux through the glazing is given by Equation (9):

where [lx] is the façade illuminance, [m2] is the window area, and [−] is the visible transmittance of the glazing (0.67).

The window is treated as a planar Lambertian emitter with uniform luminance over its surface. To capture spatial variation, the area is subdivided into N rectangular sub-elements i, each representing an elementary luminous patch of intensity (Equation (10)) assuming isotropic emission within the hemisphere.

3.3.2. Direct Illuminance at a Point

The direct illuminance [lx] at an interior point on the analysis plane (0.8 m above the floor) is computed as the superposition of contributions from all window sub-elements (Equation (11)):

where [m] is the distance from element to , and [°] is the angle between the normal of the emitting patch and the line connecting it to . This equation implements both the inverse-square attenuation and the cosine-law angular dependence.

3.3.3. Diffuse Interreflections from Interior Surfaces

The indoor environment is modeled as a closed cavity with diffuse (Lambertian) surfaces characterized by reflectance coefficients: (walls), (floor), and (ceiling). Each surface acts as a secondary luminous emitter re-radiating part of the incident light back into the space.

The first-order reflected illuminance at point is given by Equation (12):

where is number of reflecting surfaces (walls, floor, ceiling), is the reflectance of surface , [lx] is the illuminance incident on surface element , [m] is the distance from element to the evaluation point, and [°] is the incidence angle between the surface normal and the line toward .

In practice, is obtained from the direct component impinging on the surface during the first iteration.

Higher-order reflections are neglected to maintain computational efficiency; their influence is partly captured through the relatively high diffuse reflectance of the ceiling and walls.

3.3.4. Total Indoor Illuminance

The total illuminance at a given point is expressed as the sum of all contributions (Equation (13)) and captures both the direct daylight component transmitted through the window and the principal diffuse interreflections from surrounding surfaces.

3.4. Boundary Conditions and Model Parameters

The accuracy and reproducibility of the proposed daylight simulation framework depend strongly on the definition of boundary conditions and input parameters. All parameters were therefore explicitly specified and kept constant across all simulations to ensure comparability between the façade and interior modules.

- Geographical and temporal parameters

All simulations were conducted for the geographical coordinates of the experimental site: latitude , longitude , and altitude above sea level.

The time resolution was set to one hour, covering a full annual cycle of 8760 h (January–December). Solar position parameters—declination, hour angle, altitude, and azimuth—were computed for each time step based on local solar time, allowing for precise modeling of diurnal and seasonal variations.

- Environmental and optical boundary conditions

Atmospheric and surface parameters were selected according to regional climate characteristics and calibrated using local measurement data (Table 2):

Table 2.

Atmospheric and surface parameters.

- Geometrical and surface parameters

The reference test room used for the validation of the indoor illuminance model corresponds to a standard single-office geometry. Its dimensions and surface properties are summarized below:

The internal surfaces were modeled as Lambertian diffuse reflectors, and the window was treated as a planar luminous source with uniform emission over its area. These values ensure the physical realism of the façade irradiance computation and its propagation into the interior environment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Space parameters.

3.5. Model Assumptions, Simplifications, and Usability

To ensure computational efficiency and suitability for real-time building management and early design workflows, the proposed framework adopts a set of intentional modeling simplifications. These design decisions are guided by the operational constraints of intelligent building systems and conceptual design processes. These include numerical stability, deterministic behavior, and minimal data dependency.

- Rationale for the Isotropic Sky Model

The choice of the isotropic sky model of Liu and Jordan [51] represents a deliberate balance between radiometric accuracy and operational feasibility. While anisotropic formulations, such as the Perez model [52], provide a more detailed representation of circumsolar effects, they require additional site-specific atmospheric and radiometric inputs that are typically not available in standard building automation systems. As reported in the literature [53], the differences between sky models in real building environments are often obscured by other sources of uncertainty, including sensor noise, glazing aging, and unmodeled shading conditions.

A key characteristic of the proposed framework is its independence from measured meteorological irradiance data. In contrast to anisotropic sky formulations that rely on global horizontal irradiance (GHI) or direct normal irradiance (DNI) as required boundary conditions, this approach derives all irradiance quantities analytically. By integrating solar geometry with established atmospheric transmittance models (Hottel; Liu–Jordan), the irradiance field is reconstructed directly from physical principles.

As a result, GHI is not considered an external input, but rather an implicit result of the model formulation. This eliminates the dependency on radiometric sensors or weather station data and enables deterministic operation in sparse data environments. This feature makes the proposed framework particularly suitable for smart building applications, embedded control systems, and early design workflows where direct GHI/DNI measurements are typically not available. While anisotropic sky models can achieve higher peak accuracy when high-quality irradiance measurements are available, the proposed approach provides a robust, autonomous, and operationally viable alternative for practical real-world deployments.

In addition to the Perez formulation [52], several other anisotropic sky models—such as the Hay-Davies, Reindl, and Klucher approaches [53,54,55]—have been proposed to better represent the non-uniform luminance distribution of the sky. However, these formulations similarly rely on additional radiometric or atmospheric inputs, which increases the modeling complexity and computational demands. In sparse data environments and on low-power embedded hardware, the potential gains in radiometric accuracy are often outweighed by the need for deterministic behavior and operational robustness. As a result, the proposed framework represents a viable and well-justified choice for a sensor-independent analytical framework.

- Indoor Light Propagation and Geometric Range

The indoor daylight distribution is modeled using first-order diffuse interreflections, assuming Lambertian behavior of interior surfaces. This analytical treatment follows the fundamental principles established in benchmark test cases such as CIE 171:2006 [56]. This ensures that the dominant components of daylight penetration are captured with sufficient accuracy for functional performance assessment, while avoiding the computational burden associated with modeling higher-order interreflections.

- System-level determinism and computational constraints

By avoiding stochastic ray tracing, iterative sky luminance reconstruction, and complex branching logic, the framework achieves deterministic and low-latency execution. This feature is particularly important for embedded controllers, IoT gateways, and predictive control loops, where repeatability and numerical stability are more important than instantaneous peak accuracy.

- Glazing, spectral, and geometric simplifications

The daylight transmission through glazing is characterized using a broadband visible light transmittance factor, neglecting spectral dependencies. This simplification is suitable for lighting-based analyses and threshold-driven lighting control strategies (e.g., 300–500 lx). External obstacles and complex shading devices are not explicitly modeled to maintain general applicability and avoid site-specific ray tracing dependencies.

- Time resolution

Simulations are performed at an hourly time step, providing a practical balance between dynamic response and low computational overhead. This time resolution is sufficient for annual daylight assessment, early design exploration, and real-time smart building control applications.

Despite these simplifications, validation results (Section 5) demonstrate that the model reproduces measured façade and interior illuminance with errors below 15%, confirming its reliability for design-stage and control-oriented daylight analysis.

4. Model Implementation

To operationalize the proposed theoretical framework for solar radiation and indoor daylight distribution, a custom computational model was implemented in MATLAB R2022b [52]. The model integrates solar geometry evaluation, irradiance decomposition, façade illuminance calculation, and interior light propagation within a modular architecture. This structure ensures flexibility with respect to façade orientation, climatic conditions, and interior configurations while maintaining computational efficiency.

4.1. Model Architecture

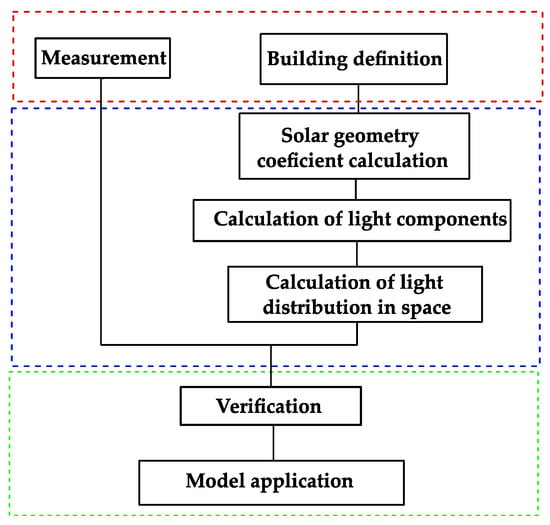

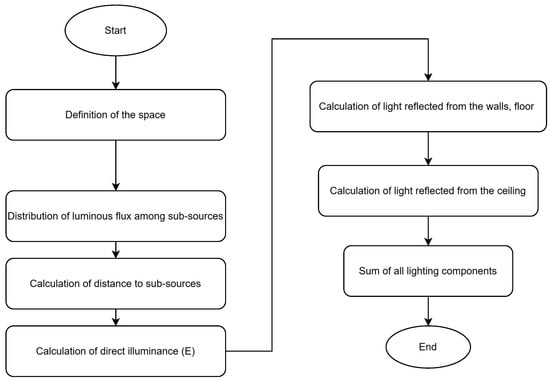

The complete simulation workflow is organized into a sequence of modular processing stages, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Model block diagram.

- Input collection:

Meteorological and geographic input data, including time, date, location, and atmospheric parameters, are imported or generated. Simulations are performed with hourly temporal resolution over a full year (8760 time steps) to capture seasonal and diurnal variability.

- Computation of irradiance and illuminance:

Irradiance and illuminance components are calculated using the analytical formulations defined in Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3. Solar position parameters are obtained from the solar geometry model, irradiance components are derived using atmospheric transmittance and decomposition models, and interior light propagation is computed using the discretized window-as-area-source formulation. These formulations are applied directly within the simulation workflow without re-derivation.

- Verification:

The final stage of the workflow involves verification against real measured data. This step is used to assess predictive accuracy, validate the model assumptions, and evaluate suitability for smart building applications under real operating conditions.

Indoor illuminance is evaluated on a computational grid defined on a horizontal analysis plane at a height of 0.8 m. Figure 2 presents a schematic block diagram of the methodology, where dotted lines indicate boundaries between simulation stages and data exchange directions. Color coding distinguishes process categories: red denotes input parameters, blue represents computational procedures, and green indicates simulation outputs and validation results.

4.2. Simulation of Facade Daylight Distribution

The simulation of façade daylight distribution constitutes the initial stage of the proposed two-stage framework. In this step, the incident solar radiation on each building façade is evaluated with hourly resolution over the entire year. The computation of façade irradiance is achieved through the utilization of analytical formulations delineated in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2. Solar position parameters are obtained from the solar geometry model, while the direct, diffuse, and ground-reflected components of solar radiation are calculated using empirical atmospheric transmittance models. For each façade orientation and inclination, the individual components are corrected for the angle of incidence and combined to obtain the total global irradiance on the inclined surface. The simulations are performed for a selection of façade orientations corresponding to the building geometry. The resulting façade irradiance values are stored as façade-specific boundary conditions and subsequently used as input for the interior daylight distribution model. This approach facilitates the efficient and physically consistent estimation of façade daylight exposure while maintaining low computational complexity, rendering it suitable for real-time and control-oriented smart building applications.

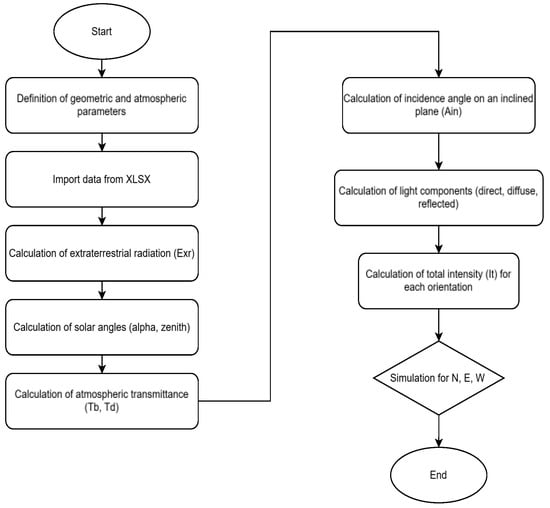

The block diagram of the computational algorithm for façade solar irradiance calculation is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Block diagram of the computational algorithm for façade-level daylight simulation.

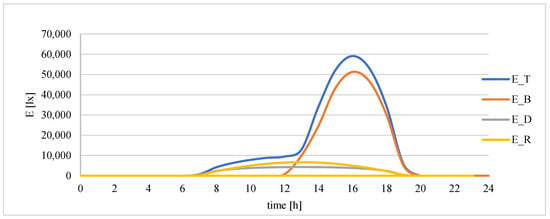

Figure 4 shows the simulated daily course of irradiance on a west-facing facade. It clearly shows how the orientation of the facade affects the magnitude and timing of each component.

Figure 4.

Daily course of irradiance on a west-facing façade.

Beam irradiance becomes dominant during the afternoon hours, when the Sun passes through the western sky. In the morning, the western facade receives minimal direct light, while diffuse and reflected components remain present throughout the day. In contrast, east-facing facades experience strong direct irradiance in the morning, and south-facing facades receive relatively balanced exposure throughout the daylight hours.

4.3. Simulation of Interior Daylight Distribution

The results of previous façade irradiance simulations were then used to define the light input for the indoor environment. These values were interpreted as light sources, corresponding to window, introducing daylight into the interior. This modeling strategy allows a physically coherent treatment of the daylight input, and the model is as close as possible to real lighting conditions.

The light input from the façades was thus converted into a uniform area source distributed over the window surface. The spatial distribution of the indoor lighting was then calculated with reference to a horizontal analytical plane located 0.8 m above floor level. This level is specified in the EN 12464-1 standard, which defines the standard workplace height for most occupied spaces. Although this reference height was primarily used, the model architecture supports adjustable height levels to accommodate alternative applications such as industrial, laboratory or storage environments.

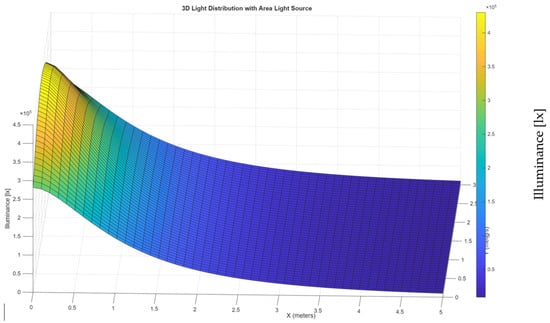

The simulation of the interior lighting distribution was performed using the inverse square law and cosines law, which governs the decrease in light intensity with distance from the emitting surface. This law forms the basis for calculating the contribution of each light sub-element in the window to each point in the room. Block diagram of algorithm is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Block diagram of algorithm.

The interior daylight simulation is conducted in accordance with a structured workflow. The geometry of the room, the aperture of the window, and the analysis plane are defined, and a uniform grid of observation points is generated on the working plane. The window surface is discretized into elementary area sources, with each emitting an equal portion of the transmitted luminous flux. For each observation point, direct illuminance contributions are computed using an inverse-square formulation with Lambertian cosine weighting. The approximation of indirect illumination is achieved through the utilization of first-order diffuse reflections from interior surfaces, characterized by empirical reflectance coefficients (, , ). The total illuminance distribution is obtained by superposition of direct and reflected components.

The spatial grid for analysis was defined with 0.25 m spacing along both room axes, producing a matrix of illuminance values on the working plane.

Figure 6 illustrates the spatial pattern of indoor daylight levels for the reference room geometry, highlighting the gradual decrease in illuminance from the window toward the rear wall. The results confirm that the model accurately reproduces both the magnitude and spatial gradient of daylight under real-sky boundary conditions.

Figure 6.

Simulated 3D illuminance distribution on the horizontal analysis plane (0.8 m height) obtained using the proposed two-stage daylight model.

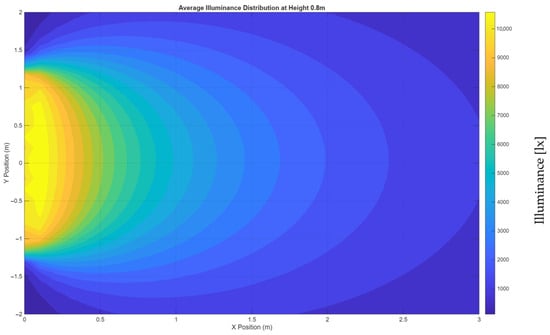

The heat map illustrates the spatial variation in indoor illuminance for the reference room geometry and façade orientation corresponding to the measurement campaign (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Simulated 2D illuminance distribution on the horizontal analysis plane (0.8 m height) obtained using the proposed two-stage daylight model.

The highest illuminance levels occur near the window due to direct daylight penetration, while a gradual decrease toward the rear wall reflects the influence of diffuse interreflections. The simulated pattern accurately reproduces the measured spatial gradient, capturing both the localized high-intensity zone adjacent to the façade and the uniform attenuation across the workspace.

Deviations remain below ±50 lx across most of the analysis plane, demonstrating strong agreement with the measured data and confirming the robustness of the window-as-area-source formulation.

5. Results and Model Validation

The final step before deploying the developed model in practical applications is to validate its accuracy using independent measured data. The main objective of this validation phase is to determine whether the model reliably predicts the spatial distribution of lighting and demonstrates sufficient accuracy and robustness for real-world implementation.

The model validation was performed at three different levels:

- Façade irradiance model,

- Interior light propagation model,

- Integrated end-to-end model.

The validation of each component was performed independently, as practical use cases may only require partial simulation. For example, in cases where measured external lighting data are available, it is not necessary to simulate the façade irradiance; instead, it is sufficient to execute the interior light propagation module. Conversely, in cases where indoor measured data are not available, a comprehensive simulation is necessary, covering everything from the sun position to the indoor light distribution. This modular approach to validation ensures that the model is adaptable to changing input data availability and specific application requirements.

The validation was based on experimental data obtained from a test building. Comparisons were made for specific sensor locations and at different times to assess: the accuracy of the model interpretation (i.e., whether the predicted trends correspond to the measured lighting dynamics), and the computational robustness under different daylight conditions, such as clear or cloudy sky scenarios.

To verify the accuracy of the proposed two-stage daylight model, a year-long measurement campaign was conducted in a full-scale reference room located in Central Europe. The data from Section 3.4 were used as input data for parameterization. Illuminance measurements were performed using a Mavospec Base spectroradiometer (GOSSEN Photo- und Lichtmesstechnik GmbH, Germany) equipped with class A photometric sensors in compliance with DIN 5032-7/CIE 69 standards (measurement accuracy ±3%). The spectroradiometer covers the visible spectral range of 380–780 nm with a nominal spectral resolution of 10 nm, and was calibrated against national metrology standards prior to the measurement campaign to ensure traceable accuracy.

A total of 12 calibrated sensors were used during the measurements:

- Three façade sensors were positioned at the center of each window to record exterior illuminance, and

- Nine interior sensors were arranged in a grid on the horizontal analysis plane at a height of 0.8 m, following the EN 12464-1 [57] workplace lighting standard.

Measurements were acquired every minute and subsequently aggregated into hourly values to match the simulation time step, resulting in 8760 hourly records for the facade orientation.

This setup enabled simultaneous monitoring of both façade exposure and indoor daylight distribution under real-sky conditions throughout the validation period.

The dataset covers the entire year, including clear, partly cloudy, and overcast conditions. Each orientation was monitored for at least one month per season to capture characteristic solar angles and sky conditions. The experimental setup was calibrated before each campaign, and uncertainty propagation was quantified using the manufacturer’s calibration data.

The validation results are presented through graphical plots that facilitate a visual comparison of simulated and measured lighting values. These graphical outputs allow for easy identification of differences and patterns. In addition, quantitative error metrics were used, including: the root mean square error (RMSE) and the relative error (% deviation).

These indicators provide a clear measure of the model’s performance under different lighting conditions and support its calibration for practical deployment—especially in intelligent lighting control systems or in the design of energy-efficient buildings with respect to daylight.

5.1. Façade Model Validation

The façade model reproduces the measured daily and seasonal illuminance trends with a high degree of consistency across all investigated orientations. The mean relative error ranges from 9.7% for the east-facing façade to 14.3% for the west-facing façade, corresponding to RMSE values between 4725 and 5225 lx. The slightly higher deviations observed for the west façade are mainly attributable to partial afternoon shading caused by nearby vegetation and adjacent structures. These site-specific obstructions were intentionally excluded from the geometric representation in order to preserve the general applicability of the model.

Model validation was conducted using long-term measurements collected over a full calendar year for façades oriented east, south, and west. Annual evaluation ensures representative coverage of recurring solar trajectories, while short-term variability is dominated by stochastic weather conditions. To capture this variability, a subset of days was randomly selected each month, encompassing a wide range of solar positions and atmospheric states. Overall, the façade sub-model demonstrates good agreement with field measurements and provides reliable boundary conditions for subsequent interior illuminance simulations

As shown in Table 4, a summary of the monthly validation results for each facade orientation is presented.

Table 4.

Results of façade model validation.

For west-facing façades, higher deviations were observed during summer, mainly due to local shading by vegetation and adjacent structures.

Conversely, the south and east façades exhibited larger differences during winter and transition months.

These discrepancies are attributed to site-specific environmental factors such as terrain morphology, nearby buildings, and vegetation, which introduce dynamic and irregular shading effects not parameterized in the model.

Accurate representation of such effects would require detailed 3D environmental scans, which are impractical for generalized daylight simulations.

Despite these limitations, the façade model achieved high correlation with measured data and is considered reliable for estimating façade-level solar exposure.

Its flexible formulation allows direct conversion of illuminance outputs to irradiance (W/m2), enabling its integration into building energy simulations and assessments of façade-integrated photovoltaic (PV) systems.

The model can therefore serve as a consistent bridge between daylight performance prediction and solar energy potential analysis on vertical surfaces.

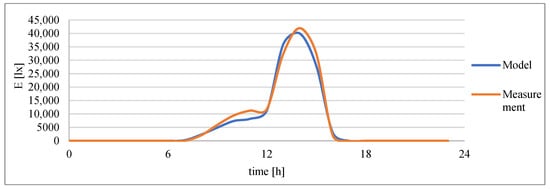

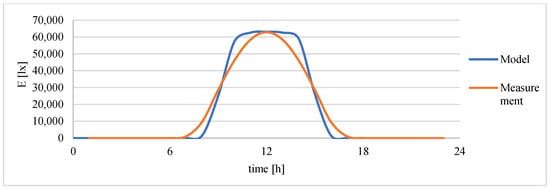

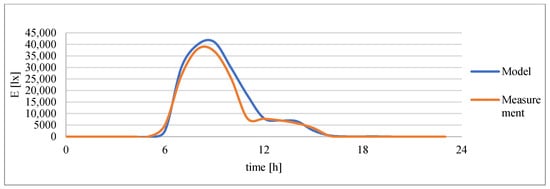

The diurnal variations in measured and simulated irradiance for three representative orientations are shown in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10. A strong temporal agreement between measured and predicted values is evident across all cases. As expected, the west façade (Figure 8) reaches its maximum in the afternoon and early evening, the south façade (Figure 9) peaks around midday with the highest overall exposure, and the east façade (Figure 10) shows a morning maximum followed by gradual decline. Minor discrepancies are consistent with the unmodeled shading effects discussed above, while the overall temporal correlation confirms that the façade model is physically consistent, generalizable, and robust for practical daylight and solar-energy applications.

Figure 8.

West façade light intensity profile.

Figure 9.

South façade light intensity profile.

Figure 10.

East façade light intensity profile.

5.2. Interior Light Distribution Validation

Using the simulated façade illuminance as boundary input, the interior daylight distribution was evaluated for the reference test-room geometry.

Illuminance was assessed on the horizontal analysis plane at 0.8 m height, corresponding to the standard working-plane level defined in EN 12464-1.

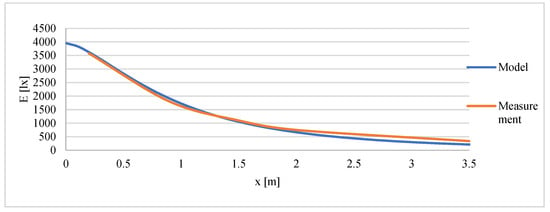

The model successfully reproduced both the magnitude and spatial pattern of measured illuminance, maintaining high stability across the full dynamic range of exterior daylight levels (1–60 klx).

The overall (RMSE) was approximately 73 lx, and the mean relative error was 9.24%, indicating excellent quantitative agreement with the experimental data.

The discretized window-as-area-source formulation thus provides robust predictions of spatial daylight gradients within the occupied zone. Slight deviations in the rear part of the room (below 50 lx under clear-sky conditions) were mainly attributed to the first-order reflection assumption and the omission of higher-order interreflections. The achieved accuracy remains within the 10–15% tolerance recommended by CIE guidelines, confirming the suitability of the model for design-stage daylight simulations and daylight-responsive control analysis.

The methodology underlying this analysis is based on the observation that the relationship between the luminous flux of an area source and the resulting indoor illuminance is approximately linear.

As summarized in Table 5, the model maintains comparable relative accuracy across the entire illuminance range. This consistency confirms the robustness and generalizability of the indoor illuminance model in practical architectural and energy applications.

Table 5.

Interior light distribution results.

Figure 11 provides a visual comparison of measured and simulated illuminance for a representative case (7000 lx façade level). The alignment of the two curves demonstrates the model’s capability to reproduce spatial and temporal illuminance patterns with high accuracy. The minor deviations observed are well within acceptable limits. This feature confirming that the model is physically consistent, computationally stable, and robust enough for practical lighting design, daylight-controlled systems, and performance optimization.

Figure 11.

Comparison measured and simulated illuminance for 7000 lx.

5.3. Combined Validation Methodology

The complete two-stage simulation chain, coupling the validated façade and interior modules through the glazing transmittance, was applied to evaluate the overall daylight performance of the reference room.

This integrated framework combines the prediction of façade irradiance with the simulation of indoor illuminance. It forms a continuous end-to-end workflow that represents the transformation of solar radiation from exterior incidence to interior light distribution.

The validation of the combined model followed the same experimental configuration and climatic datasets as those used for the individual sub-models, ensuring consistency across all levels of comparison.

The facade model provided the irradiance boundary conditions for the interior module. The daylight attenuation through the glazing was represented by the visible light transmittance, which took into account absorption and multiple internal reflections within the triple glazing. The described validation procedure aimed to realize both the temporal and spatial behavior of daylight in the reference room. This included the evaluation of daily and seasonal lighting patterns, the interaction between facade exposure and interior light distribution, and the overall stability of the model under different sky conditions. The results of this combined validation are presented in the following section.

5.3.1. Selection of Reference Space and Facade Orientation

A single reference room was selected for the combined validation experiment. The space, located on the west side of the building. The geometric parameters are (5 m × 3 m × 3 m) with a 2.5 m × 2.0 m window as the only source of daylight. The use of an identical geometric model ensured a clear connection between the simulated and measured conditions. This approach minimizing potential differences due to parameter mismatches.

5.3.2. Measurement of External and Internal Illuminance

To ensure statistical and seasonal representativeness, measurements were performed on randomly selected days in different seasons—winter, spring, summer and autumn. For each selected day, hourly measurements were taken of:

- External irradiance on the west facade and

- Indoor illuminance on the work surface.

To remove short-term meteorological variability and increase the robustness of the comparison, hourly averages were calculated.

5.3.3. Integrated Façade–Interior Chain Validation

The façade irradiance predicted by the first-stage model was used as boundary input for the second, indoor module responsible for simulating the spatial light distribution. The integrated simulation chain thus describes the complete process of solar radiation transfer—from exterior illuminance on the façade to interior illuminance at the working plane.

The comparison between measured and simulated indoor illuminance yielded an average RMSE of 118 lx and a mean relative error of 15.8% over the full annual dataset. These deviations are lower than in the preliminary validation (132 lx, 18.6%) due to the improved treatment of diffuse interreflections and ceiling contribution in the indoor model. Although the integrated error remains slightly higher than that of the individual sub-models—façade (9.7–14.3%) and interior (≈9.2%)—the results are well within the 20% tolerance recommended by the CIE for field-validated daylighting simulations.

5.3.4. Conclusion of the Combined Validation

The comprehensive validation confirmed that the two-stage analytical framework accurately captures the coupled transformation of solar radiation—from façade to interior illuminance distribution.

The facade model achieved outdoor illuminance with average errors below 12%, while the interior model achieved RMSE ≈73 lx and average error ≈9.2%, maintaining linear behavior over the entire illuminance range (1–60 klx).

The integrated system preserved overall consistency, achieving RMSE ≈ 118 lx (mean error ≈ 15.8%), which represents a significant improvement compared with the initial configuration and remains acceptable for design-stage analysis.

These findings verify that the proposed framework is physically consistent, computationally efficient, and robust for predicting daylight availability in both façades and interior environments. It provides a practical foundation for architectural daylight design, energy simulation, and daylight-responsive lighting control in early-stage and operational contexts.

6. Discussion

The daylight simulation model developed in this study provides a physically consistent and computationally efficient framework for estimating both the availability and spatial distribution of daylight. This approach describes the complete daylight path—from the incident solar radiation on the building facade to its propagation and distribution in the indoor environment. The framework is organized into two interconnected sub-models, allowing for flexible deployment depending on the desired level of detail, available input parameters, and intended use in smart building design or operation analysis.

6.1. Accuracy and Predictive Performance

In Table 6, is a summary of the quantitative validation results for all three levels of modeling—facade irradiance, interior light distribution, and the combined simulation model is presented.

Table 6.

Summary of model validation performance across all levels.

The facade irradiance model showed a relative error ranging from 9.68% to 14.25% depending on orientation and seasonal conditions with a root mean square error ranging from approximately 4700 to 5200 lx. The findings indicate a strong correlation between the measured and simulated values in all cardinal directions.

The interior light distribution model was validated under controlled conditions using different illumination levels. The root mean square error of the model was found to be approximately 73 lx with an average relative error of ~9.2%. These results confirm the linear and consistent behavior of the model over a wide dynamic range.

Finally, a combined validation was performed. The analysis yielded a RMSE of 118 lx and a relative error of 15.8%. Despite the compound uncertainties (e.g., weather variability, spatial constraints), the residual error remains within acceptable limits for the purposes of architectural daylighting analysis and energy simulation.

The validation results confirm that the proposed two-stage model reliably simulates both the solar radiation dynamics and the indoor lighting distribution under real-world conditions. his makes the framework suitable for practical applications such as daylighting design optimization, lighting management strategy development, and supporting sustainability certification.

6.2. Discussion of Error Factors

The deviations between measured and simulated data were analyzed and grouped into two main categories: environmental factors and physical-model factors.

- Environmental factors

Short-term variations in global illuminance due to transient cloud cover, reflections from nearby buildings, and partial shading from surrounding vegetation were identified as the dominant external sources of error. Such effects produce temporal fluctuations that cannot be captured by the isotropic-sky assumption adopted in the model. Because the framework intentionally excludes detailed geometric modeling of adjacent objects to preserve generality, these environmental effects appear as localized biases, particularly on the west façade during late-afternoon periods.

- Physical-model factors

The slight deviations can be largely attributed to the necessary simplifications used in the analytical model. These include the assumption of Lambertian surface reflectance and the simplified description of the spectral and angular behavior of the glazing. A small additional contribution comes from the sensor calibration drift (below 2%), which introduces systematic uncertainty into the reference measurements.

The sensitivity analysis shows that the model is particularly affected by atmospheric conditions and surface optical properties. A decrease in atmospheric transmittance of 0.05 leads to an increase in the facade-related error of approximately 3%, while a change in wall reflectance of 0.1 leads to a 2–3% increase in the intrinsic error. This confirms that atmospheric purity and surface reflectance are the dominant factors affecting the accuracy of daylight prediction.

Together, these effects explain the observed deviations in the range of approximately 15–19%. Importantly, this level of agreement remains within the 20% tolerance recommended by the CIE for daylight models validated under real outdoor conditions. Although the average deviation of the proposed concept (approximately 18–19%) may at first glance appear to be relatively high, it should be considered in the context of the methodology used. Such a level of deviation is comparable to values commonly reported for simplified daylighting models used in practice.

Further reduction in the average bias is possible without fundamentally changing the analytical nature of the model. Potential improvements include the introduction of simple anisotropic sky corrections, finer discretization of the window opening, improved characterization of surface reflectance, and more detailed treatment of the spectral properties of the glazing. While more advanced simulation tools can achieve lower absolute errors, CIE validation studies still report differences of 10–30% between measured and simulated indoor illuminance, often at significantly higher computational costs.

The accuracy achieved should therefore be considered in relation to the intended use of the model. For applications such as rapid daylight estimation in smart building control, optimization, and embedded systems, the balance between computational efficiency and prediction accuracy is more important than achieving the lowest possible error under idealized conditions.

However, this finding is consistent with empirical studies by [53] who noted that isotropic models exhibit their highest errors on vertical surfaces under low solar altitudes. For smart lighting control, where the system reacts to functional thresholds rather than absolute luminance gradients, this error margin is acceptable. The stability, speed, and minimal data dependency provided by the isotropic model outweigh the need for instantaneous radiometric precision in closed-loop control applications. The observed deviations are primarily associated with the model assumptions outlined in Section 3.5.

6.3. Computational Efficiency and Applicability

Each full-year daylight simulation, covering 8760 hourly time steps, was completed in under 60 s on a standard workstation. This corresponds to a computational speed-up of more than two orders of magnitude compared to detailed ray-tracing tools such as Dialux [58], when run at comparable temporal resolution and under equivalent boundary conditions.

This level of efficiency makes the framework well suited for rapid parametric studies, iterative façade optimization, and the development of real-time daylight control strategies—tasks that are generally impractical when using conventional simulation software. At the same time, the analytical formulation preserves physical transparency, which facilitates model calibration and straightforward coupling with energy simulation workflows and building automation systems.

Overall, the method offers a practical compromise between computational speed and physical consistency, making it particularly suitable for early design decision-making and dynamic daylight management applications.

To further assess computational performance and predictive accuracy, the proposed analytical framework was benchmarked against the commercially available software DIALux evo 12, which employs a hybrid ray-tracing and radiosity engine.

Under identical boundary conditions and geometry, DIALux required approximately 18 min to complete a single hourly daylight simulation, whereas the proposed model performed this task (8760 h) in less than 1 min.

This represents a computational acceleration of roughly 18× per hourly step, while maintaining comparable accuracy: the mean deviation between DIALux and the proposed model results was within 8–12% across all orientations (Table 7).

Table 7.

Comparison of computational performance and accuracy.

Such consistency confirms that the simplified analytical approach retains the essential physical realism of established simulation tools, while offering significantly higher speed and easier integration into parametric design optimization and real-time daylight-control applications.

When extended to an annual daylight simulation (8760 hourly steps), the computational difference becomes even more pronounced.

The proposed model performs the full-year simulation in less than one minute on a standard workstation while DIALux evo 12 would require approximately 157,680 min (≈2628 h ≈ 110 days) for the same time resolution.

Considering only daylight hours (≈4380 h per year at 48° N latitude), the total DIALux runtime still amounts to about 55 days, compared with under 60 s for the proposed method.

These results indicate a computational acceleration relative to conventional ray-tracing software, while preserving a mean relative deviation of only 8–12%.

The marginal loss in photometric precision is far outweighed by the substantial gain in performance, enabling the proposed framework to be applied in real-time daylight control, sensitivity analysis, and climate-based annual optimization.

A direct comparison with Radiance was not included in this study, primarily because high-resolution ray-tracing simulations require extensive computation time and detailed material modeling, which would contradict the intended focus on lightweight, real-time-capable daylight estimation. Additionally, Radiance benchmarking is most meaningful under controlled test cases rather than full-year simulations. For this reason, a targeted benchmarking study using Radiance and DIALux—based on selected representative hours and sky conditions—will be conducted as part of future work.

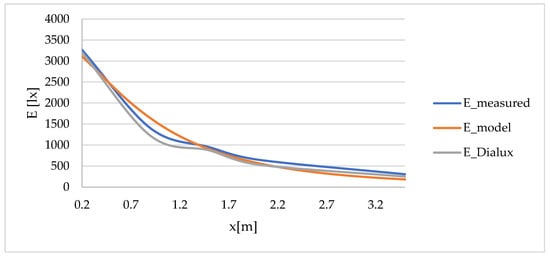

Figure 12 illustrates the horizontal illuminance distribution along the central axis of the reference room, comparing measured data, the proposed two-stage model, and DIALux evo simulations. The x-axis represents the distance from the façade [m], and the y-axis shows the illuminance on the working plane.

Figure 12.

Comparison of measured and simulated horizontal illuminance profiles along the room depth.

Experimental measurements (E_measured, blue line) are compared with predictions from the proposed analytical model (E_model, orange line) and DIALux evo (E_DIALux, gray line). The measured curve shows the expected exponential decrease in illuminance from the window toward the rear wall, which both models reproduce accurately.

The analytical model exhibits a slightly faster decay within the first meter from the façade, corresponding to the omission of higher-order interreflections, while DIALux predicts marginally higher values near the window due to its detailed ray-tracing of secondary reflections. Beyond 1.5 m from the façade, the three profiles converge closely, with deviations below 10%. This agreement confirms that the proposed analytical framework achieves nearly the same predictive accuracy as DIALux while being over several orders of magnitude faster in computation.

6.4. Computational Complexity Analysis

The low computational complexity of the proposed solution is attributable to its analytical formulation and the absence of iterative numerical procedures. The illuminance of the facade, the transmitted luminous flux, and the luminance of the window are calculated using algebraic formulas based on solar geometry and the principles of light transmission. Utilizing these assumptions, it can be concluded that there is no requirement for additional numerical integration, stochastic sampling, or convergence loops. This approach contributes to reduced computational complexity.

The calculation of light propagation inside a space is based on the calculation of contributions from N elementary surface sources and reflections, followed by the summation of contributions at interior points plane. The calculation of each source contribution is based on the inverse square law and the cosine law. Consequently, the overall computational complexity is linearly scalable as .

The calculation and approximation of reflected illumination is achieved through the utilization of first-order diffuse reflections. This approach circumvents the utilization of recursive ray interactions and matrix solutions, which are characteristic of radiosity or ray tracing methods. Conversely, physical tools such as Radiance necessitate Monte Carlo ray sampling. The proposed approach itself is linearly scalable and enables fully deterministic evaluation for year-round simulations (8760 time steps) within a few seconds, rendering it suitable for real-time smart building control and embedded applications.

6.5. Sensitivity and Limitations

The discrepancies observed between measured and simulated illuminance values are mainly caused by external environmental factors that are not explicitly represented in the analytical model. During the summer period, partial shading from vegetation and nearby buildings has a noticeable impact on façade illuminance, particularly in the afternoon. In addition, irregular features of the surrounding built environment—such as neighboring structures, uneven terrain, or reflective surfaces—create non-uniform boundary conditions that are difficult to describe within a simplified analytical framework.

Further uncertainty arises from the treatment of glazing. In practice, glazing systems exhibit manufacturer-specific spectral transmittance characteristics and angular dependence. Although the current implementation applies a static correction for triple glazing with a visible transmittance of 0.67, a more detailed optical description would improve predictive accuracy, especially for spectrally resolved daylight assessments or coupled building energy simulations.

The handling of diffuse and reflected radiation is also intentionally simplified, relying on uniform surface reflectance values and Lambertian scattering assumptions. While this approach provides sufficient accuracy for most architectural applications, more advanced techniques such as radiosity or ray tracing would be required to capture higher-order interreflections and complex light–surface interactions in geometrically irregular or highly reflective spaces.

These limitations stem from the deliberate design choice to prioritize computational efficiency and real-time applicability. To maintain linear computational complexity and deterministic execution times, the model adopts simplified physical assumptions, including an isotropic diffuse sky representation, first-order diffuse reflections, and Lambertian surface behavior. Although these simplifications can reduce accuracy under specific conditions—such as very bright sky states or interiors with highly reflective materials—they enable performance levels that are not achievable with conventional simulation approaches.

Importantly, these trade-offs are consistent with the intended application of the framework, namely rapid daylight estimation for smart building control, embedded systems, and optimization workflows. At the same time, several targeted enhancements have been identified that could improve accuracy without compromising the model’s core advantages. These include simplified anisotropic sky corrections, adaptive window discretization, more detailed spectral glazing models, and hybrid analytical–data-driven extensions. The integration of such features is expected to further improve predictive performance while preserving the computational efficiency that underpins the proposed approach.

6.6. Practical Applications

Notwithstanding the above simplifications, the proposed daylight simulation model demonstrates broad practical applicability across several domains of architectural design and building performance analysis.

Daylight assessment during the early design phases is a critical component of architectural decision-making, as it directly affects both the functional and visual quality of indoor environments.

The proposed framework can therefore be applied in the following areas:

- Façade-integrated photovoltaic systems

The estimation of solar energy yield can be performed through direct radiometric conversion of façade irradiance predicted by the model, enabling integrated assessments of energy and lighting performance.

- Daylight-responsive lighting control

The model supports the calibration and optimization of sensor-based lighting algorithms in intelligent building systems, where real-time or predictive control strategies depend on accurate daylight availability data.

- Architectural optimization