Abstract

Establishing a reduced-order model (ROM) of the wind turbine generator system (WTGS) preserving transient characteristics is a fundamental requirement for the transient stability analysis of power systems. This study introduces a novel dimension reduction framework based on trajectory eigenvalues, integrated with virtual inertia control (VIC). The framework facilitates multi-timescale state variable partitioning through a reversible mapping, which is derived from eigenvalue dominance and participation metrics. Based on this, dimension reduction is performed using singular perturbation theory (SPT). Taking a direct-drive wind turbine generator as an example, this paper establishes a ROM of the WTGS with VIC preserving transient characteristics, based on the proposed reduction method. Comprehensive time-domain simulations in MATLAB/Simulink validate the model’s accuracy and computational efficacy.

1. Introduction

As the penetration rate of wind turbines continues to rise, the overall inertia level of the power system has declined relatively, severely deteriorating the system’s stability characteristics [1,2,3,4]. To ensure the safe and stable operation of the power system, wind turbines must be able to respond to changes in the grid. Wind turbines equipped with virtual inertia control can provide inertia support, directly responding to system frequency changes by adjusting their output power [5,6,7,8,9]. However, the response of wind turbines varies depending on their distance from the fault point, the severity of the fault, and the type of fault. Additionally, during the transient process, the inertia response characteristics of the grid become more complex and variable [10,11,12]. Due to the high order and complex structure of the FOM of WTGS incorporating virtual inertia, transient stability mechanism analysis becomes challenging and computationally intensive [13,14,15]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a ROM of WTGS that can precisely describe the transient characteristics of VIC under faults, to meet the computational and analytical requirements of renewable energy power systems.

Research into reduced-order modeling for WTGS has yielded various strategies, predominantly centered on simplifying the full-order model (FOM) according to specific analysis needs [16,17,18,19,20,21]. For instance, ref. [16] developed a unified DFIG model using an excitation–response approach to study rotor-speed-scale transients. Meanwhile, ref. [17] proposed a ROM for direct-drive turbines, that retains outer-loop control and VIC, and ref. [18] introduced a ROM for full-converter wind turbines aimed at transient stability analysis. Ref. [19] presented a reduced-order modeling approach for efficient modeling and dynamic stability analysis of a utility-scale hybrid grid-tied system utilizing the participation factor analysis and the residue-based method. Ref. [20] performed the detailed small-signal modeling of the DFIG integrated system by linearizing the dynamic characteristic equation at the steady-state value. Ref. [21] presents a wind turbine generator reduced-order model for time-domain simulations using selective modal analysis to reduce the model order by focusing on the most relevant modes and variables. Despite their utility, a common limitation of these approaches is their dependence on heuristic, multi-timescale simplification rules that lack a firm quantitative basis. Singular perturbation theory (SPT) offers a mathematically structured framework for timescale separation and has been widely adopted in power system model reduction [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Ref. [24] employed SPT to develop a ROM for DFIGs, thereby simplifying the original high-order model into a fast and a slow subsystem. Ref. [25] analyzed the time scales of the internal dynamic and electrical network dynamics of a battery energy storage system using SPT and derived the corresponding ROM. Ref. [26] proposed a dynamic integrated energy system model based on the SPT, which denotes the dynamic interactions of the multi energy systems. Ref. [27] introduced results in applying singular perturbation theory to obtain simplified power system models for stability analysis and control design. The topics include synchronous machine modeling, slow coherency and dynamic equivalence of large power networks, and transient stability analysis using direct methods. Ref. [28] proposed a nonlinear dynamic order reduction method for direct-drive wind turbine generators based on disturbed trajectory space decoupling, but it does not consider the impact of virtual inertia control on the system. From the downscaling processes proposed in the above literature, it can be seen that the key to implementing downscaling methods based on SPT lies in accurately dividing the original system into multiple time scales. A significant challenge arises from the escalating nonlinear and time-varying behaviors in modern power systems. This casts doubt on the ability of conventional reduction techniques to maintain the transient fidelity of the WTGS FOM, especially when simultaneously subjected to grid faults and the complex dynamics introduced by virtual inertia. The trajectory eigenvalue theory based on holistic restoration thinking can precisely reconstruct the complex dynamic response of the original system. This theory obtains holistic information by preserving the mapping of the perturbed state trajectory of the FOM, thereby alleviating the complexity of the original model while retaining its multiple nonlinear information [29]. Ref. [30] introduced the concept of the “trajectory cross-section virtual equilibrium point eigenvalue sequence” to study the oscillation damping and instantaneous frequency at the farthest point and the saddle point, revealing the intrinsic connection between large and small disturbance instability. Ref. [31] provided practical criteria for transient stability based on trajectory eigenvalues and designed an online prediction algorithm for transient stability. Trajectory eigenvalue theory has also made progress in the analysis and control of low frequency oscillation [32,33] and ultra-low frequency oscillation [34]; ref. [33] introduced a trajectory section eigenvalue method that can reflect the influences of complex models and fault scenarios and a trajectory reconstruction method is proposed to accomplish the decoupling of multi-eigenmodes in the time domain. However, this theory has not yet been applied in dimension reduction methods suitable for transient stability analysis [35]. However, existing SPT-based methods often overlook the influence of virtual inertia on trajectory eigenvalues under faults.

Substantial research has been conducted on the modeling and dimension reduction of wind power systems. Ref. [36] provided a comprehensive review of control strategies for wind turbines to deliver frequency support, highlighting their essential role in enhancing system inertia. Ref. [37] focused on the modeling and stability analysis of Doubly Fed Induction Generators (DFIGs), pointing out that the coupling between electromagnetic transients and mechanical dynamics is a critical factor that cannot be overlooked. Furthermore, Ref. [5] demonstrated that virtual inertia control is paramount for maintaining frequency stability in such systems, although its effectiveness is highly dependent on system parameters and operational states. Ref. [38] proposed a data-driven algorithm for model order reduction in large-scale wind farms and studies the effects that the obtained reduced-order model has when this is integrated into the power grid. These studies collectively emphasize the necessity of accurately capturing the dynamic behavior of VIC-equipped wind systems across different applications.

This paper bridges that gap by integrating VIC into a trajectory eigenvalue dominance analysis, enabling a more physically interpretable and accurate ROM suitable for high wind penetration systems. Unlike previous methods, our approach emphasizes the role of virtual inertia in the trajectory eigenvalue analysis. First, the FOM of WTGS incorporating virtual inertia control strategies is briefly introduced. Then, the dimension reduction method based on trajectory eigenvalue dominance is detailed and, based on this, a ROM of WTGS preserving transient characteristics is established. Finally, the accuracy and applicability of the proposed ROM under faults are verified through time-domain simulations.

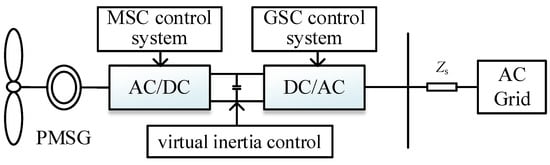

2. Control Strategy of WTGS with VIC

The architectural configuration of the WTGS enhanced with virtual inertia control is illustrated in Figure 1. The system architecture encompasses two main segments: the direct-drive wind turbine generator (D-WTG) segment and the alternating current (AC) grid interface segment. Core constituents of the WTGS include the permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG), the virtual inertia control module, the machine-side converter (MSC) complemented by its control mechanisms, and the grid-side converter (GSC) integrated with its corresponding control system [39].

Figure 1.

Structure diagram of WTGS grid-connected system considering VIC.

To ensure prompt system response, an auxiliary frequency regulation strategy is integrated into the virtual inertia control framework. This supplementary control methodology incorporates a reference signal that is algebraically combined with the DC voltage references [40,41], capitalizing on the transient energy storage characteristics of the DC bus capacitor to deliver immediate inertial support and damping to the power system.

The virtual inertia control module in the GSC control system employs virtual inertia control based on low-pass filter (VICLF). Drawing on the characteristics of low-pass filters (passing low frequencies and blocking high frequencies), VICLF ignores the high-frequency components of disturbances and only processes their low-frequency components. By introducing a delay element, VICLF can slow down the frequency response speed and enhance the system’s inertia effect. Its transfer function is expressed as

where K1 and w1 are the control coefficient and control parameter of VICLF, respectively.

The phase synchronization method uses droop control based on the active power-frequency droop characteristic. w0 is the reference value for frequency. The difference between the reference value P0 for active power and the actual value Pg is the active power deviation. The product of the power deviation and the droop coefficient a is the frequency adjustment term. The mathematical model for droop control is shown in Equation (2).

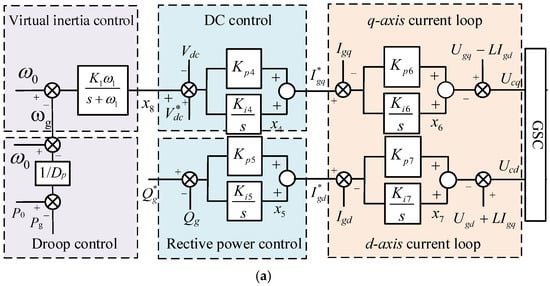

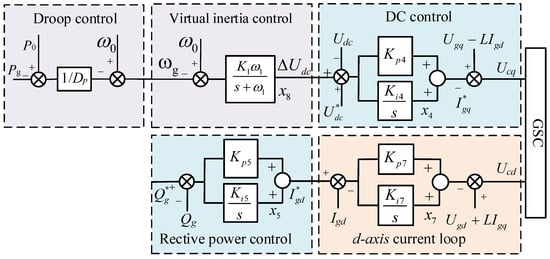

VIC couples the change in DC bus voltage with the change in grid angular frequency a, enabling the DC bus voltage to respond to frequency changes in the system and provide transient energy support for the system. The GSC and MSC control block diagram of the FOM with VIC is shown in Figure 2a,b. The converter is connected to the grid via an SRF-PLL, with its control structure shown in Figure 2c. Since the phase-locked loop is significant, it is retained in the model. The output x8 of VIC and the DC bus voltage reference value are used together as the setpoint for the DC voltage control outer loop. The difference between this setpoint and the actual DC bus voltage Vdc is calculated, followed by the output by the PI controller, and is then finally used as the reference value for the q-axis current control inner loop. and q-axis current actual values Igq are used to achieve current closed-loop control. The difference between the reactive power output of the WTGS and the reference value is calculated and, after passing through the PI controller, the reference value for the d-axis component of the grid-side current is obtained . This reference value is used together with the actual d-axis current value Igd to achieve closed-loop current control.

Figure 2.

The control diagram of WTGS FOM considering virtual inertia control. (a) GSC; (b) MSC; (c) PLL.

In Figure 2, the reference value expression for the q-axis current control inner loop of the VIC is expressed as

When the WTGS experiences a fault, it has difficulty delivering active power, and the high-voltage side DC bus voltage Vdc suddenly increases due to the accumulation of unbalanced power. At this point, the system frequency wg decreases. As can be seen from Equations (3) and (4), VIC provides temporary inertia support to the system by releasing the energy stored in the high-voltage side DC bus capacitor, thereby causing Vdc to decrease.

In summary, the state model of the WTGS with VIC can be mathematically represented by the following set of differential algebraic equations,

where f(X,U) and g(X,U) are the state equation and output equation of the WTGS with VIC, respectively; X is the corresponding state vector, with a total of 14 state variables, namely Igd, Igq, Vdc, Isd, Isq, ws, and x1–8. Igd and Igq are the d-axis and q-axis components of the grid-side current, Vdc is the DC-side voltage, Isd and Isq are the d-axis and q-axis components of the stator current, ωs is the rotor angular velocity, x1–8 are intermediate variables introduced by the PI controller in the converter control system, and U is the voltage vector at the grid-connection point of the WTGS.

3. Dimension Reduction Based on the Primary Degree of Trajectory Eigenvalue

To establish a wind turbine ROM suitable for fault scenarios and preserving transient characteristics with VIC, this paper proposes a dimension reduction method based on the primary degree of trajectory eigenvalue. This section first introduces the reduction process based on SPT. Then, by employing nonlinear function approximation on the non-equilibrium points of the perturbed state trajectory of the WTGS FOM incorporating VIC, the corresponding linearized model is obtained. New state variables are introduced to achieve mode decoupling of the FOM through a preserving mapping. The primary participation factor is defined by combining the dominance and participation factors of the trajectory eigenvalues to achieve a reversible inverse mapping of the D-PMSG state variables. Finally, all state variables of the WTGS are divided into multiple time scales. Based on this, a ROM of the WTGS preserving transient characteristics during faults is established using SPT.

The proposed dimension reduction method in this paper is applicable to transient stability analysis of WTGS and is based on the following three assumptions:

- (1)

- The system operates within the region where linearization remains valid near the non-equilibrium point.

- (2)

- The parameter settings for virtual inertia control fall within a reasonable range and do not lie within the range that could induce instability in the full-order model.

- (3)

- The reduced-order model is used for large disturbance analysis and the disturbance does not excite oscillations in the system.

3.1. Singular Perturbation Theory

The singular perturbation theory-based reduction methodology initiates by categorizing all state variables of the VIC-equipped WTGS FOM into two distinct groups: slow dynamics (Xslow) and fast dynamics (Xfast). This classification naturally leads to the partition of the corresponding state equations into two complementary subsets. The state equations related to slow variables are retained, and the state equations corresponding to fast variables are rewritten in singular perturbation form:

where ε is the singular perturbation parameter matrix reflecting the system characteristics.

Let ε = 0, Equation (7) degenerates from a differential equation into a steady-state equation, thereby obtaining the steady-state solution of each state variable in Xfast

Substituting Equation (8) into Equation (6) yields the ROM of WTGS:

Through the above reduction process, it can be seen that the key prerequisite for singular perturbation reduction is to quantitatively describe the influence of WTGS variables on the transient behavior of the system, so that fast and slow variable sets can be accurately divided.

3.2. Trajectory Eigenvalue Dominance Analysis

The trajectory eigenvalue method falls under the concept of segmented linearization, performing linearization at different time intervals to determine the system’s eigenvalues [42]. The piecewise linearized model can reflect the operational state at that point. Therefore, as long as the segmentation step size is sufficiently small, its results can sufficiently approximate the original trajectory. It is evident that, for a specific disturbance process, the aforementioned piecewise linearized model is completely equivalent to the original nonlinear model. This provides the feasibility for implementing the trajectory eigenvalue method. The simulation considers the nonlinear response of the state vector of the WTGS FOM incorporating VIC after encountering a fault, yielding the corresponding state trajectory. When no fault is applied, the system is in a balanced state. After the fault disappears, the system remains in a non-equilibrium operating state for a period of time. The WTGS state vector (non-equilibrium point) corresponding to the instant when the fault disappears is selected as the first linearization point.

Subsequently, z non-equilibrium points are sampled at time intervals of t = tc along the perturbed state trajectory of the WTGS as linearization points. According to Equation (10), a nonlinear function approximation is performed on the full-order WTGS model considering VIC at the non-equilibrium point, yielding the n × n -order state matrix and n × p -order input matrix [A, B] at the non-equilibrium point.

where and are the small perturbation of the m-th state variable and input variable, respectively, at the non-equilibrium point Xi. The resulting linearized state-space model at this point is expressed in terms of the full state deviation vector ΔX and input deviation vector ΔU:

As shown in (11), the rate of change of each state variable is a linear combination of all state variables and input quantities. Due to the cross-coupling between state variables and input quantities, it is difficult to directly separate the state variables that dominate the dynamic behavior of the system. To eliminate the mutual coupling between state variables, the state vector ΔX is transformed into a new state vector ΔZ, resulting in

In the equation, V is the characteristic matrix of the state matrix A at the non-equilibrium point.

After replacing the state variables, the new system state-space equation (diagonal canonical form) is obtained as

where Λ and BΛ are shown as below:

Equation (14) represents n decoupled first-order equations, which indicate that the state variables in the WTGS FOM are decoupled, i.e., the dynamic response of the transformed state variable ΔZi is determined solely by the corresponding trajectory eigenvalue λi.

Expanding each differential equation in Equation (13) and performing a Laplace transform on each equation yields the s-domain expression shown in Equation (16).

where bЛij is the element of BЛ at the i-th row and j-th column and νji is the element of V at the i-th row and j-th column. Further expanding Equations (16) and (17) yields

The time-domain solution of the state variables is obtained by applying the inverse Laplace transform to Equation (19).

In Equation (20), the li,jh term represents the primary effect of the trajectory eigenvalue λi on the state variable ΔX under the action of νii and bЛih. Therefore, it is defined as the sub-contribution index. λi usually appears in complex form, so the sub-contribution index calculation formula in complex form shown in Equation (21) is given.

The trajectory eigenvalues affect each state variable in the WTGS FOM. By summing the sub-dominance of the trajectory eigenvalues λi for all state variables, the dominance of λi for ΔX can be calculated, as shown in Equation (22).

where n denotes the number of state variables and p denotes the number of input variables.

The right eigenvector ψi of the feature matrix V, combined with the left eigenvector ϕiTF, defines the participation factor pki = ϕki × ψki, which represents the degree of mutual participation between the i-th trajectory eigenvalue λi and the k-th state variable ΔXk. Traditional eigenvalue dominance only considers the influence of eigenvalues on system output, severing the connection between the dominance of eigenvalue and state variables. If the dominance Li corresponding to the trajectory eigenvalue λi is a large value, the participation factors of each state variable in the trajectory eigenvalue λi may be small values. In this case, the subsequent WTGS fast and slow variable set partitioning will yield an incorrect result. Therefore, the dominance and participation factors of the trajectory eigenvalue λi can be coupled to strengthen the association between the trajectory eigenvalue and the state variables.

Combining the participation factor corresponding to λi with the contribution index, we obtain

where γi represents the degree of participation of the kth state variable and the ith trajectory eigenvalue when considering the dominance of the trajectory eigenvalue in WTGS, which is defined as the primary participation factor. By calculating all γi values, we can determine the participation degree of the trajectory eigenvalue λi in all state variables. The higher the participation degree, the stronger the correlation between the two. By defining the primary participation factor, we have completed the reverse mapping from the state trajectory eigenvalue to the state variables, enabling a quantitative analysis of each state variable’s influence on the system’s transient behavior. This provides an intuitive basis for the multi-timescale partitioning of state variables in the WTGS framework, which incorporates VIC considerations.

3.3. Multi-Time Scale Partitioning Criteria

Iterate through each primary contributing factor of the trajectory eigenvalue. If the corresponding γki value of the WTGS state variable ΔXk in any trajectory eigenvalue is greater than 0.05, it is considered a slow variable; otherwise, it is considered a fast variable, thereby completing the division into fast and slow variables. The threshold of 0.05 originates from a sequential analysis of the maximum values of dominant participation factors, calculating the contribution threshold as , where denotes maximum primary participation factor. This implies that when data falls below 10% of the average value, its influence can be disregarded. We referenced the statistical concept of contribution and applied this method to model analysis [43]. The multi-timescale division of the WTGS state variable considering VIC also needs to follow the following criteria:

- (1)

- To maintain the stability of the WTGS ROM, all trajectory eigenvalues must be less than zero.

- (2)

- After completing the fast and slow variable set partitioning of WTGS, the steady-state solution of the state variables in Xfast can be obtained as shown in (8).

- (3)

- To enhance simulation speed, while ensuring the above two aspects are maintained, the order of the WTGS ROM should be minimized as much as possible.

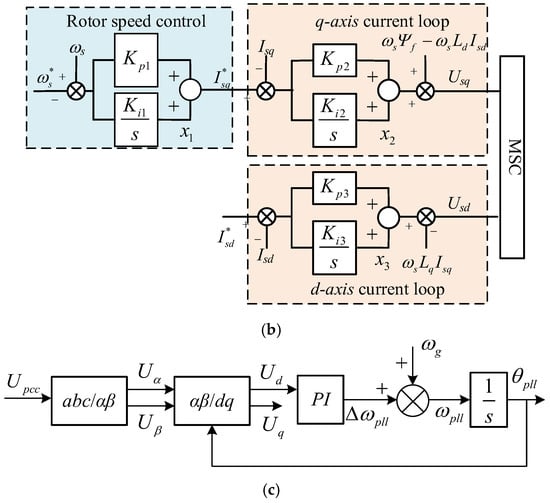

3.4. WTGS with VIC FOM Reduction Process

In summary, the dimension reduction process of the WTGS FOM with VIC is shown in Figure 3, with the specific steps as follows:

Step 1: Select a non-equilibrium point on the perturbed state trajectory of the WTGS FOM and obtain the linearized model of the WTGS FOM at the non-equilibrium point through nonlinear function approximation.

Step 2: Decouple the mode solutions of the linearized model at the non-equilibrium point. Define the primary participation factors based on the dominance and participation factors of the trajectory eigenvalues, thereby completing the quantitative analysis of the WTGS state variables on the system’s transient behavior.

Step 3: Divide the WTGS model into fast and slow variables based on the criteria for multi-timescale partitioning.

Step 4: Based on the results of the fast and slow variable partitioning in Step 3, perform dimension reduction on the WTGS FOM incorporating VIC using SPT.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of WTGS FOM reduction considering VIC.

4. Verification of Dimension Reduction Method

For validation purposes, a comprehensive simulation model of the WTGS power generation system was developed within the MATLAB/Simulink (2024b) environment. The wind power generation unit was interconnected with an equivalent grid model with nominal power 1000 MW and frequency modulation coefficient KG = 20 p.u. Detailed system parameters employed in the simulations are comprehensively presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

System simulation parameters.

4.1. Analysis of the Reduction Results

Validation of the proposed reduction method is conducted by introducing a severe three-phase-to-ground fault at the WTGS point of common coupling. The fault is initiated at t = 1.0 s, persists for 0.2 s, and the total simulation duration is 3 s. We recorded the dynamic response of the WTGS FOM equipped with VIC. From this response, eight non-equilibrium points are selected for analysis, commencing from the instant of fault clearance and spaced at a constant time interval Δt. These points are used to compute the primary participation factors of each state variable, as listed in Table 2. The resulting slow and fast variable sets, determined via a threshold of 0.05 on the maximum primary participation factor, are shown in Table 3. The ROM is then constructed using SPT by retaining slow variables and neglecting fast dynamics.

Table 2.

The maximum primary participation factor of each variable.

Table 3.

Results of fast and slow variables set division.

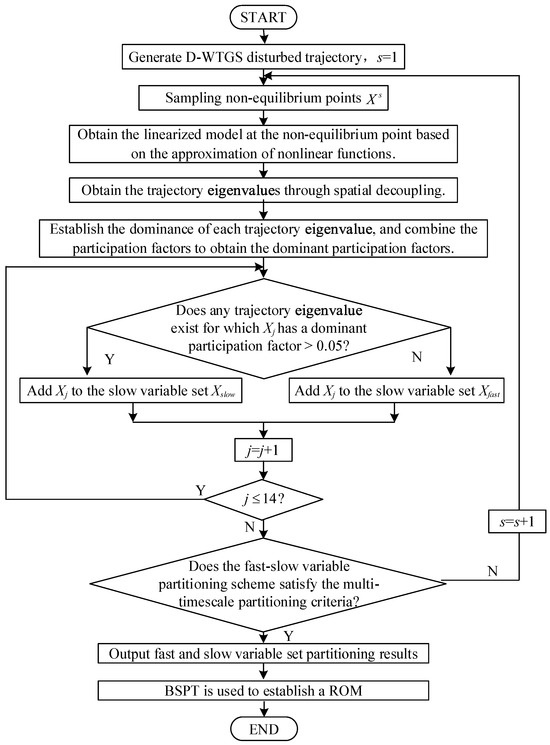

After reducing the order of the WTGS FOM with VIC according to SPT, the WTGS ROM ignores the rotor dynamics, MSC, and its control system, retains the intermediate capacitor, and ignores only the inner loop control of the q-axis in the control structure of the GSC. The remaining control strategies, especially the VIC, are retained. The control block diagram of the GSC with VIC in ROM is shown in Figure 4. The dynamic equations before and after reduction are shown in Appendix A.

Figure 4.

The GSC control diagram of WTGS ROM considering VIC.

4.2. Influence of VIC Parameters on Primary Contributing Factors

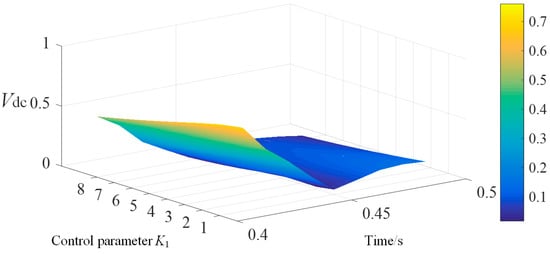

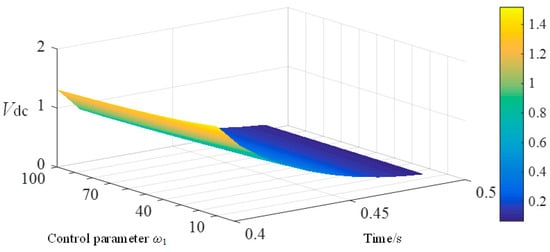

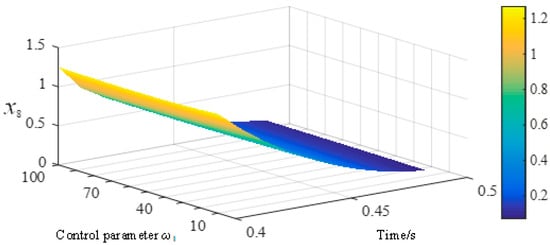

To clarify the impact of key parameters of the VIC on the DC bus voltage Vdc after fault clearance, a quantitative analysis of the maximum value of the primary contributing factors to Vdc was conducted. The effects of the control coefficient K1 and control parameters w1 on the maximum value of the primary contributing factors to the variable Vdc after fault clearance are illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 5.

The maximum value primary participation factor of Vdc with K1 changing after fault cleared.

Figure 6.

The maximum value primary participation factor of Vdc with w1 changing after fault cleared.

As shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, the maximum value of the primary contributing factor of the WTGS DC bus voltage Vdc is significantly influenced by the control coefficient K1 and control parameters w1, with its value consistently exceeding 0.05. Following fault clearance, this value increases over time as K1 and w1 increase. These results demonstrate that, within a certain timeframe after fault clearance, the system exhibits strong nonlinear response, with the DC bus voltage Vdc being significantly affected by VIC.

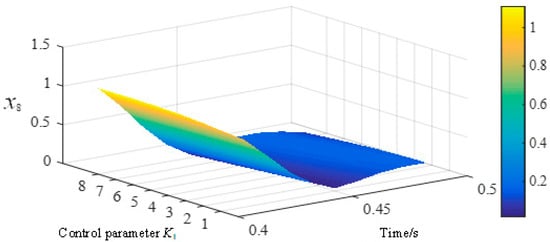

To further clarify the impact of key parameters of VIC on the control loop, the state variable x8 related to the VIC loop was selected for quantitative analysis. Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the impact of control coefficients K1 and control parameters w1 on the maximum value of the primary contributing factor of state variable x8 after fault cleared.

Figure 7.

The maximum value primary participation factor of x8 with K1 changing after fault cleared.

Figure 8.

The maximum value primary participation factor of x8 with w1 changing after fault cleared.

As shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8, the maximum change in the primary participating factor of the WTGS state variable x8 is similar to the dynamic influence of VIC on Vdc. The above results prove that, during the transient response process after the fault is cleared in the system, the variable x8 output by VIC is significantly engaged. Retaining the WTGS ROM with VIC can accurately characterize the effect of virtual inertia through the fault process.

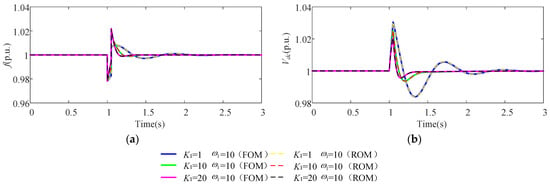

4.3. Comparison of Dimension Reduction Effects with Different Control Coefficients k1

Multiple fault scenarios were implemented on the test system to comprehensively assess the accuracy and robustness of the proposed VIC-integrated WTGS model. This evaluation was conducted through extensive time-domain simulation.

The total simulation time is set to 3 s. The scenario 1 setup: At t = 1 s, the voltage at the PCC of the WTGS drops to 0.2 p.u., with a fault duration of 0.1 s. For VIC, the control parameters w1 remained unchanged, while the control coefficients K1 were gradually increased. Figure 9a,b compare the transient response curves of the DC-side voltage Vdc and grid frequency of variables between the FOM and the ROM of the WTGS, both incorporating VIC, where solid lines represent the dynamic response curves of the WTGS FOM under different VIC parameter controls and dashed lines represent the dynamic response curves of the WTGS ROM under different VIC parameter controls. As shown in Figure 9, the dynamic responses of all variables in the WTGS ROM closely match those of the FOM. Additionally, as it increases, the grid frequency of both the WTGS FOM and its ROM reaches a higher minimum point during the fault process and the sudden increase in the high-voltage side DC bus voltage decreases. For the larger K1, the voltage increase during the fault is smaller, demonstrating the effect of VIC. With the decrease in K1, more time is needed to restore it to stable. After the fault is cleared, the fluctuations in the aforementioned variables are significantly reduced, indicating that the system’s inertia effect is enhanced.

Figure 9.

Dynamic response of (a) frequency and (b) DC voltage under varying virtual inertia gain K1.

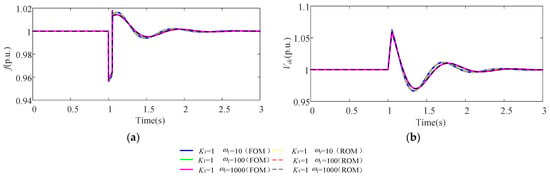

4.4. Comparison of Dimension Reduction Effects with Different Control Parameters w1

Scenario 2 setup: When t = 1 s, the voltage at the grid connection point of the test system WTGS drops to 0.5 p.u. and the fault duration is 0.1 s. For VIC, the control coefficient remains unchanged and the control parameter is gradually increased. The transient response is shown in Figure 10. As shown in Figure 10, the dynamic responses of all variables in the WTGS ROM are consistent with those of the WTGS FOM. For the influence of VIC, as w1 increases, the recovery speed of grid frequency and high-voltage side DC bus voltage in both the WTGS FOM and its ROM after fault clearance significantly slows down and the amplitude decreases, indicating that the system’s inertia effect has strengthened.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the transient response of (a) frequency and (b) DC voltage under different ω1.

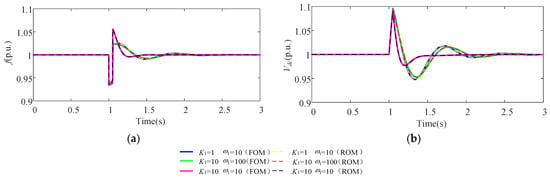

4.5. Comparison of Dimension Reduction Effects with Different Voltage Drop Depths

Scenario 3 setup: When t = 1 s, the voltage at the grid connection point of the WTGS test system drops to 0.8 p.u. and the fault duration is 0.1 s. For VIC, the control coefficient K1 and control parameter w1 are set to different values and the transient response is shown in Figure 11. As shown in Figure 11, the dynamic responses of the variables in the WTGS ROM are consistent with those of the WTGS FOM. Similarly to the dynamic response patterns of the system in the aforementioned fault scenario involving VIC, as w1 and K1 increase, the inertia effect of the system strengthens.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the transient response of (a) frequency and (b) DC voltage under different voltage drop depths.

For quantitative comparison of the discrepancies between the transient responses of the full-order and reduced-order WTGS models incorporating VIC, the following evaluation metric is established:

Mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) is utilized to quantify the deviation between FOM and ROM responses, taking VIC into account.

To further evaluate the accuracy of the WTGS model proposed in this paper, the MAPE evaluation index for each variable under different operating conditions was calculated according to Equation (24) and the results are shown in Table 4. The results indicate that, when the test system encounters different faults and the VIC is set with different parameters, the dynamic response of the ROM is highly similar to the FOM, confirming that the proposed ROM can accurately characterize the dynamic response of WTGS under different operating conditions.

Table 4.

MAPE evaluation index of WTGS ROM considering VIC.

5. Conclusions

This paper has developed a dimension reduction methodology for virtual inertia-controlled wind turbine systems, grounded in trajectory eigenvalue analysis. The technique employs a structure-preserving mapping of the disturbed system trajectory and a novel composite metric blending eigenvalue dominance and state participation, which collectively facilitate a physically interpretable separation of state variables across multiple time scales. Application of singular perturbation theory then yields a reduced-order model that faithfully captures essential transient dynamics during faults. Time-domain simulations under diverse fault conditions demonstrate a close agreement between the ROM and the full-order model, affirming the method’s precision and its potential for enhancing stability analysis in power systems with high wind penetration. This paper considers the frequency response characteristics of generators while simplifying the frequency response of loads [44]. Subsequent research will further refine the frequency response characteristics of the power grid, particularly the impact of load characteristic variations on the wind turbine reduced-order model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.W. and L.L.; methodology, Y.K. and Q.Z.; software, S.Y. and T.W.; validation, B.W., L.L. and Y.G.; formal analysis, L.L. and T.W.; investigation, Q.Z. and S.Y.; resources, Y.K. and T.W.; data curation, B.W. and Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, B.W. and L.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.K., L.L., Q.Z. and X.W.; visualization, Y.G. and T.W.; supervision, B.W. and T.W.; project administration, L.L. and X.W.; funding acquisition, B.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the State Grid Shaanxi Electric Power Corporation Science and Technology Project [grant number 5226SX22001Q].

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Biyang Wang, Li Li, Yu Kou, Qinglei Zhang were employed by the company State Grid Shaanxi Electric Power Corporation and Dispatch and Control Center of State Grid Shaanxi Electric Power Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from State Grid Shaanxi Electric Power Corporation Science and Technology Project [grant number 5226SX22001Q]. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Appendix A

Corresponding to Figure 2, the dynamic equations of a wind turbine are as follows.

The machine side (permanent magnet synchronous motor),

The equation of machine-side controller,

The equation of capacitor,

The equation of grid-side controller,

The model after dimension reduction via the proposed method is

References

- Meegahapola, L.; Sguarezi, A.; Bryant, J.S.; Gu, M.; Conde, D.E.R.; Cunha, R.B. Power system stability with power-electronic converter interfaced renewable power generation: Present issues and future trends. Energies 2020, 13, 3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xu, T.; Guo, Q.; Li, Y.; Lin, W.; Yi, J.; Li, W. Analysis on Blackout in Great Britain Power Grid on August 9th, 2019 and Its Enlightenment to Power Grid in China. Proc. Chin. Soc. Electr. Eng. 2019, 39, 6183–6191. [Google Scholar]

- Shobug, M.A.; Chowdhury, N.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Sanjari, M.J.; Lu, J.; Yang, F. Virtual inertia control for power electronics-integrated power systems: Challenges and prospects. Energies 2024, 17, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Xiaotong, W.; Zichang, H. Research on transient characteristic analysis and transient stability mechanism of distributed condenser. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2025, 40, 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, N.K.; Islam, S.; Podder, A.K.; Roy, T.K.; Muyeen, S.M. Virtual inertia support in power systems for high penetration of renewables—Overview of categorization, comparison, and evaluation of control techniques. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 129190–129216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamrakar, U.; Shrestha, D.; Maharjan, M.; Bhattarai, B.P.; Hansen, T.M.; Tonkoski, R. Virtual inertia: Current trends and future directions. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wen, Y.; Chi, F.; Wang, K.; Li, L. Research Framework and Prospect on Power System Inertia Estimation. Proc. Chin. Soc. Electr. Eng. 2021, 41, 6842–6855. [Google Scholar]

- Baruwa, M.; Fazeli, M. Impact of Virtual Synchronous Machines on Low-Frequency Oscillations in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 1934–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, K.Y.; Sarimuthu, C.R.; Lim, J.M.Y. Virtual inertia-based inverters for mitigating frequency instability in grid-connected renewable energy system: A review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhuo, F.; Yi, H.; Wu, J.; Wang, F.; Zeng, Z. Analysis of dynamic frequency performance among voltage-controlled inverters considering virtual inertia interaction in microgrid. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 4135–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Q.; Milano, F.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, W. Nonlinear Virtual Inertia Control of WTGs for Enhancing primary Frequency Response and Suppressing Drivetrain Torsional Oscillations. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 4102–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Ye, H.; Song, W.; Zhou, G. Virtual inertia control strategy in microgrid based on virtual synchronous generator technology. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 27949–27957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Li, H.; Tang, Y.; Blaabjerg, F. Distributed power system virtual inertia implemented by grid-connected power converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 8488–8499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosi, D.; Ciupageanu, D.A.; Vaccaro, A.; Barelli, L. Impact analysis of wind power generation on steady-state and transient stability of a national power system—The Romanian case study. Wind. Energy Eng. Res. 2025, 3, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskito, F.; Wijaya, F.D.; Firmansyah, E. Review of Virtual Inertia Based on Synchronous Generator Characteristic Emulation in Renewable Energy-Dominated Power Systems. Electricity 2025, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhang, R.; Hu, J. Modelling of DFIG-based WT for Power System Transient Responses Analysis in Rotor Speed Control Timescale. Proc. Chin. Soc. Electr. Eng. 2021, 41, 3037–3045. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.; Geng, H.; He, C.; Li, J. Modelling of DFIG-Based Wind Turbine for Transient Synchronization Stability Analysis. In Proceedings of the PEDG 2025-2025 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems, Nanjing, China, 22–25 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Cai, X.; Wang, N. Dynamic model of DFIG wind turbines for power system transient stability analysis. Proc. Chin. Soc. Electr. Eng. 2016, 36, 5449–5460. [Google Scholar]

- Magableh, M.A.K.; Radwan, A.A.A.; Mohamed, Y.A.R.I.; El-Saadany, E.F. A novel reduced-order modeling approach of a grid-tied hybrid photovoltaic–wind turbine–battery energy storage system for dynamic stability analysis. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2024, 5, 1459–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Wang, P.; Liu, D.; Sun, A.; Yang, D.; Yan, G. Modeling and small-signal stability analysis of doubly-fed induction generator integrated system. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2023, 6, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulgar-Painemal, H.A.; Sauer, P.W. Reduced-order model of type-c wind turbine generators. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 81, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.S. Singular Perturbation Theory: Mathematical and Analytical Techniques with Applications to Engineering; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.C. Relative perturbation theory: I. Eigenvalue and singular value variations. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 1998, 19, 956–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, X.; Hu, J.; Kang, Y. Modeling and Transient Stability Analysis for Type-3 Wind Turbines Using Singular Perturbation and Lyapunov Methods. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 8075–8086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yida, Y.; Linjun, W.; Jiayan, A. A generic ROMing hierarchy for power electronic interfaced generators with the quasiconstant-power feature. Proc. CSEE 2017, 37, 3993–4001. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, F.; Ju, P.; Shahidehpour, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Shi, X. Singular perturbation for the dynamic modeling of integrated energy systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 35, 1718–1728l. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.H.; Winkelman, J.R.; Pai, M.A.; Sauer, P.W. Singular perturbation analysis of large-scale power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 1990, 12, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Jiao, D.; Wang, Z. Nonlinear Dynamic Order Reduction Method of Direct Driven Wind Turbine Based on Disturbed Trajectory Space Decoupling. Proc. Chin. Soc. Electr. Eng. 2023, 43, 8206–8216. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Xue, Y.; Chen, G. Oscillation Analysis Based on Trajectory Modes Decoupled in Space and Mode-energy-sequence Part One Theoretical Basis. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2019, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Hao, L.; Wu, Q.H.; Jiang, L. Annotation for FEP and DSP in terms of trajectory section eigenvalues. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2010, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.; Shen, C.; Liu, F.; Ni, J. A practical criterion for trajectory eigenvalues based transient stability analysis. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2012, 36, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Bin, Z. Trajectory section eigenvalue method for nonlinear time-varying power system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 107, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, Z.; Xue, Y. A method to extract instantaneous features of low frequency oscillation based on trajectory section eigenvalues. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2019, 7, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Bin, Z. Analysis of Mode Interaction in Ultra-low Frequency Oscillation Based on Trajectory Eigenvalue. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2020, 8, 1208–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Yang, F.; Wang, J. A contingency screening method based on trajectory eigenvalues. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2013, 37, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.H.; Wu, Y.K. Overview of frequency control technologies for wind power systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Computer, Consumer and Control (IS3C) Taichung City, Taiwan, China, 13–16 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ostadi, A.; Yazdani, A.; Varma, R.K. Modeling and stability analysis of a DFIG-based wind-power generator interfaced with a series-compensated line. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery 2009, 24, 1504–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Mao, J.; Junyent-Ferré, A.; Scarciotti, G. Model order reduction of large-scale wind farms: A data-driven approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 40, 3487–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, R.T.; Dotta, D.; Wilches-Bernal, F.; Leonardi, B. Second Generation Wind Turbine Generators Generic Models in the Power System Toolbox. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, Portland, OR, USA, 5–10 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Xiong, L.; Zhang, D.; Hao, J.; Tang, Z. Virtual Inertia Control Strategy for Grid-tied Photovoltaic Power Generation System. High Volt. Eng. 2020, 46, 3743–3751. [Google Scholar]

- Khayat, Y.; Golestan, S.; Guerrero, J.M.; Vasquez, J.C.; Bevrani, H. DC-Link Voltage Control Aided for the Inertial Support during Severe Faults in Weak Grids. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2021, 9, 7296–7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chung, C.; Wong, K. Analytical calculation of power system trajectory eigenvalues and its error analysis. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2008, 32, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jalajakshi, V.; Myna, A.N. Importance of statistics to data science. Glob. Transit. Proc. 2022, 3, 326–331. [Google Scholar]

- Haro-Larrode, M.; Santos-Mugica, M.; Etxegarai, A.; Eguia, P. Methodology for tuning MTDC supervisory and frequency-response control systems at terminal level under over-frequency events. Energies 2020, 13, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.