Abstract

RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) technology has become an essential instrument in numerous industrial sectors, enhancing process efficiency and streamlining operations, allowing for the automated tracking of goods and equipment without the need for manual intervention. Nevertheless, the deployment of industrial IoT systems necessitates the establishment of complex sensor networks to enable detailed multi-parameter monitoring of items. Despite these advancements, challenges remain in item-level sensing, data analysis, and the management of power consumption. To mitigate these shortcomings, this study presents a holistic AI-assisted, semi-passive RFID-integrated multi-sensor system designed for robust food quality monitoring. The primary contributions are threefold: First, a compact (45 mm ∗ 38 mm) semi-passive UHF RFID tag is developed, featuring a rechargeable lithium battery to ensure long-term operation and extend the readable range up to 10 m. Second, a dedicated IoT cloud platform is implemented to handle big data storage and visualization, ensuring reliable data management. Third, the system integrates machine learning algorithms (LSTM) to analyze sensing data for real-time food quality assessment. The system’s efficacy is validated through real-world experiments on food products, demonstrating its capability for low-cost, long-distance, and intelligent quality control. This technology enables low-cost, timely, and sustainable quality assessments over medium and long distances, with battery life extending up to 27 days under specific conditions. By deploying this technology, quantified food quality assessment and control can be achieved.

1. Introduction

Ensuring food safety in modern supply chains faces a critical challenge: the disconnect between external logistics tracking and internal quality monitoring. While traditional supply chains rely on visual inspection or expiration dates, these methods fail to detect real-time spoilage caused by package seal failures or temperature abuse [1]. The core technical barrier lies in achieving continuous, item-level sensing of internal parameters (e.g., CO2, humidity) for sealed products. Existing passive RFID solutions often suffer from signal attenuation in liquid-rich food environments, while active tags are too costly and bulky for individual items. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a system that bridges these gaps by combining robust semi-passive sensing with intelligent data analysis.

Notwithstanding the amount of research that has already been done, there are still plenty of unsolved practical problems with product quality assessment sensing (QAS) techniques [2]. In these problems, one of the most important parts is a complete data analysis platform that could be used for data storage, visualization, and real-time analysis. These could be supported by cloud computing technologies, including cloud databases. Cloud databases are innovative solutions hosted on cloud platforms such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud Platform (GCP), and Microsoft Azure that provide scalable, flexible, and cost-effective data management [3]. Unlike traditional on-premise databases, cloud databases leverage the huge resources of cloud infrastructure to provide high performance and availability, making them ideal for handling large amounts of data and high transaction rates. They support a variety of data types and workloads, integrate seamlessly with other cloud services, and adhere to strong security standards, including data encryption and automatic updates [4]. Despite data sovereignty and security issues, cloud databases provide modern enterprises with comprehensive, efficient, and versatile data management solutions [5].

Regarding the supporting hardware for QAS, a complete implementation that integrates hardware, advanced data management, and artificial intelligence is conspicuously absent, despite substantial research in individual areas. To address these gaps, this paper proposes a unified framework that synergizes rechargeable semi-passive RFID hardware with an AI-enabled cloud platform, ensuring both reliable long-term sensing and intelligent data analysis.

The sensors used in this study are integrated with RFID tags and intended to track parameters at the item level. The study first presents a mains-powered reference system that complies with EPC Global Class 1 Generation 2 UHF RFID standards [6] and integrates several sensors with semi-passive RFID tags. It then explores a rechargeable and sustainable design to improve hardware adaptability across environments. Key aspects of this work include a compact PCB for monitoring low-volume items and a data structure aligned with EPC standards for efficient terminal information management. To support real-time analytics, a cloud data platform integrated with artificial intelligence (AI) is used to apply QAS to food items. While existing RFID-based sensing systems have shown promise, they often suffer from limited sensing duration, a lack of real-time analytics, and dependence on passive power. In contrast, this study presents a holistic system with the following key contributions: (1) Hardware Innovation: A compact, semi-passive UHF RFID multi-sensor tag is designed with an onboard power management system for rechargeable lithium batteries, solving the endurance and range limitations of traditional tags. (2) System Integration: A comprehensive AIoT cloud platform is developed to enable reliable data transmission, storage, and visualization, bridging the gap between physical sensing and digital management. (3) Intelligent Application: An AI-assisted quality assessment framework using LSTM models is implemented and validated through real-world food spoilage scenarios, demonstrating the system’s practical value in predictive quality analysis. By synergizing these hardware and software components, this paper provides a unified reference architecture for next-generation intelligent supply chains.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 details the onboard design of the semi-passive RFID tag-integrated sensor; Section 3 discusses the battery management system and conducts a parametric analysis; Section 4 describes the implementation and validation of the RFID-integrated sensor; Section 5 develops the IoT platform for big data storage and explores the application of AI-assisted big data analysis for target evaluation; and Section 6 concludes the paper and summarizes the findings.

2. Related Works

In recent years, non-destructive testing methods such as microwave spectroscopy have been widely explored [7,8,9]. However, these approaches typically require complex, immobile laboratory equipment, rendering them unsuitable for dynamic logistics chains [10]. Consequently, research has shifted towards RFID-integrated sensors. While recent studies have demonstrated the potential of passive RFID sensors for humidity and gas detection [11], they frequently face reliability issues when deployed on high-water-content food products due to severe RF energy absorption [12]. Furthermore, the lack of onboard data logging in passive tags limits the continuity of quality monitoring. This highlights a critical research gap: the need for a semi-passive architecture that combines the cost-effectiveness of RFID with the reliability of battery-assisted sensing.

Over the past decade, the widespread adoption of RFID tags has given rise to various concepts blending the physical and virtual realms. One such prominent concept is the IoT, which envisions the expansion of the Internet into our everyday lives through a wireless network of uniquely identifiable devices. As the demand for RFID tags has increased significantly, the production cost of each tag has gradually decreased to 5 cents per tag [13]. In addition, in contrast to conventional methods of item and product identification, such as barcodes, RFID tags offer a greater capacity for information storage. This expanded storage capability enables the system to effectively execute tracking and tracing functions [14]. Furthermore, the concept of IoT enables all the uniquely identifiable devices to connect to each other and share information within the local wireless network [15], which means that it is possible to develop a system for monitoring all the parameters needed regarding food, including real-time quality indexes, transport information, origin information, and so forth, for ensuring food safety and reducing food waste.

While RFID technology is generally categorized into passive, semi-passive, and active modes [16], the specific requirements of food quality monitoring demand a tailored architectural choice. Passive tags, although cost-effective, suffer from limited read ranges and instability in liquid-rich environments (such as meat products) where RF energy is easily absorbed [17,18,19]. Conversely, active tags offer an extended range but are often hindered by high unit costs and bulky form factors, making them economically unviable for item-level tracking [20,21]. To bridge this gap, this study focuses on a semi-passive architecture [22,23,24,25,26,27]. By using an internal battery to power the circuit [28,29], this design supports robust data logging [30] and multi-sensor integration (e.g., temperature and humidity) [31,32], all while maintaining the backscatter communication efficiency of passive systems. This approach effectively resolves the trade-off between performance and power consumption, enabling continuous, long-term monitoring of internal package conditions.

Recent studies have explored the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into environmental quality monitoring systems to enhance prediction accuracy and support informed decision-making. Machine learning algorithms—such as decision trees, support vector machines (SVM), random forests, and least squares support vector machines (LS-SVM)—have been widely applied to the prediction of time-series sensor data [33,34,35]. These models are particularly effective in capturing nonlinear relationships and temporal dependencies among environmental variables, such as carbon dioxide concentration, temperature, and humidity. Building on this foundation, ref. [36] proposed a data fusion algorithm that integrates camera imagery and sensor inputs for lesion detection in food products. This demonstrates the potential of applying various AI models to predict collected data, thereby providing a theoretical basis for estimating food shelf life.

3. Sensor Design Methodology

3.1. RFID-Integrated Multi-Sensor

To fulfil the needs of the industrial production sector, a semi-passive RFID tag-integrated sensor system is proposed and developed. This system operates in the United Kingdom in accordance with European Telecommunication Standards Institute regulations and makes use of common frequency bands. It conforms to the EPCglobal Gen 2 (ISO/IEC 18000-6C) protocol [6], which guarantees dependable communication and effective data exchange. The 865 MHz to 868 MHz band is used for the system’s radio frequency activities, and an effective isotropically radiated power (EIRP) of 2 W is maintained throughout. Range and dependability are improved by the semi-passive RFID tags, which have a battery that powers the internal electronics but not the transmission. To improve functionality, these tags also allow the integration of several sensors. The system is designed to operate efficiently in both near-field and far-field settings. In near-field applications, it makes use of short-range magnetic field couplings to ensure safe data transmission, while in far-field applications, it uses long-range electromagnetic waves to provide wider coverage.

3.2. Communication Standards

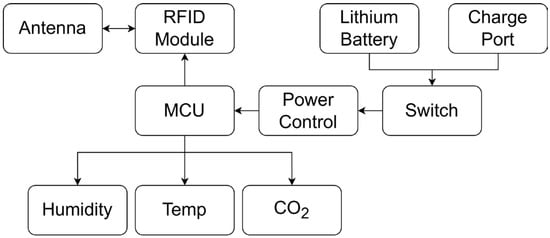

The proposed hardware architecture is detailed in Figure 1. Unlike generic passive tags, this design features a dedicated dual-mode power management module that switches between USB charging and lithium battery output. This ensures a stable voltage supply for the energy-intensive multi-sensor array (temperature, humidity, and CO2) without depleting the RF backscatter energy. The MCU acts as the central hub, managing sensor data acquisition and waking up the RFID module only when data transmission is triggered. Semi-passive RFID tags with sensor capabilities bring up new possibilities for applications requiring continuous, autonomous data gathering across medium-range to long-range distances [15]. These sensors improve tracking, asset monitoring, and environmental sensing capabilities by effectively gathering and transmitting real-time data on various parameters [19].

Figure 1.

Hardware framework for a semi-passive RFID integrated sensor.

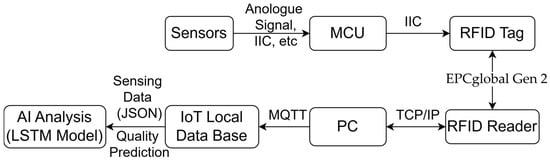

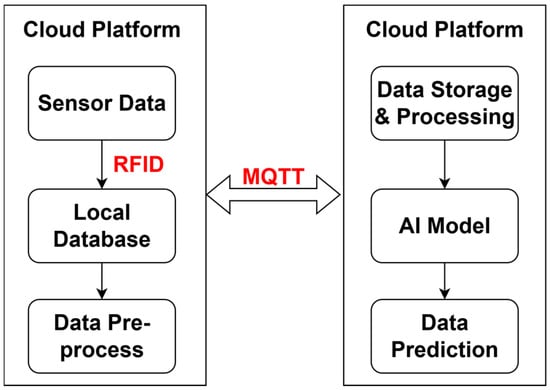

Figure 2 depicts the specific end-to-end data flow of the proposed system. Data collected from the specific food quality sensors are packetized by the MCU and transmitted via the EPC Gen2 protocol. Crucially, the diagram highlights the integration of the AIoT Cloud Platform, where raw sensing data are not only stored but also processed by the deployed LSTM machine learning model to generate real-time quality predictions. Moreover, in addition to utilizing EPCglobal Gen2, which allows unlimited user memory for communication between the RFID tag and the reader, the system employs the TCP/IP protocol for data transmission between the reader and the computer, facilitated by an RJ45 connector. Furthermore, the data collected by the computer are transmitted to the cloud IoT platform via Ethernet, utilizing the Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) protocol. It is important to note that the maximum data capacity is primarily dictated by the size of the cloud database. Consequently, the overall data capacity of the system is closely linked to the development costs of the cloud platform.

Figure 2.

System data flow and communication protocols.

3.3. Data Security

To ensure end-to-end data security, specific security configurations were implemented at three distinct layers. (1) Tag Layer: The RFID communication utilizes the EPC Gen2 Access Password mechanism (32-bit) to lock the user memory bank. This prevents unauthorized writing or tampering of the sensor data stored on the tag [27]. (2) Transport Layer: Data transmission between the reader and the PC, as well as from the PC to the Cloud, is encapsulated within TLS 1.2 (Transport Layer Security) tunnels. This ensures that the sensing data remain encrypted and immune to eavesdropping during network transport [37]. (3) Application Layer: The MQTT connection to the IoT platform enforces strict identity verification using unique client IDs and token-based authentication, combined with Access Control Lists (ACLs) to strictly limit topic subscription permissions to authorized devices only [38]. This multi-layered approach effectively safeguards data integrity from the physical sensor node to the cloud database.

3.4. Semi-Passive RFID Circuitry Design

An essential part of semi-passive RFID circuitry that significantly improves their functioning and reliability is the consideration of battery power design [39]. Semi-passive RFID tags combine the advantages of passive and active RFID technologies by using a battery to power their internal circuitry and relying on reader signals for communication [40].

To provide resistance to physical stressors and environmental issues like temperature changes and humidity, safety and stability are of utmost importance in battery design. Additionally, a major consideration in battery power design is energy efficiency. While tags are within a reader’s range, power management techniques are used to reduce energy consumption and preserve power while the device is not in use. This frequently entails the use of energy-saving circuit designs and sleep modes, which only enable the tag’s sensors and communication capabilities when necessary. In this specific design, the PIC12LF1552 microcontroller was selected as the core controller due to its extremely low power technology, ensuring minimal energy drain during sleep modes. For environmental sensing, the system integrates an HDC2010 sensor for high-precision temperature and humidity monitoring, and a CCS811 digital gas sensor for equivalent carbon dioxide detection. As shown in the detailed circuit diagram in Figure 3, the MCU communicates with these sensors via the I2C interface. To further optimize power efficiency, the system utilizes the MCU’s interrupt-on-change feature: the MCU remains in deep sleep and is only triggered when the RFID module receives a specific interrogation command or when the sensor interrupt line signals a threshold breach. Moreover, the RFID tag’s battery integration needs to be implemented in a way that does not significantly enlarge the tag or alter its form factor. To keep semi-passive RFID tags useful and efficient for their intended uses, the entire design must carefully balance battery life, tag size, and functional capabilities.

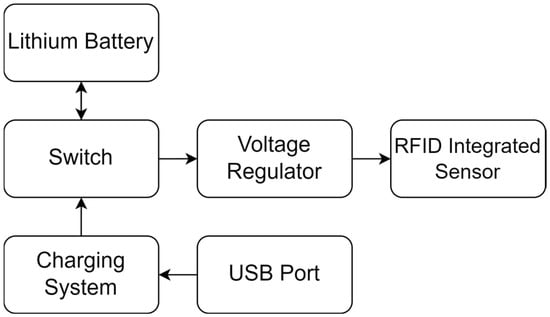

Figure 3.

Framework for semi-passive RFID circuitry.

The functioning and connectivity of the parts of a dual-mode power system for an RFID tag-integrated sensor are shown in a schematic flowchart in Figure 3. The switch in the system is an essential part that controls the lithium battery’s mode of operation, which can be either output or charging mode. When the switch is in charging mode, electricity may be transferred from a USB port to the lithium battery through the charging system, enabling the battery to recharge. On the other hand, the switch routes power from the lithium battery to a voltage regulator while it is in output mode. The function of the voltage regulator is to ensure that the RFID-integrated sensor operates properly by stabilizing and adjusting the battery’s output voltage to the necessary level.

3.4.1. Battery Power Supply

The battery market is a multi-billion-dollar industry, influencing economies worldwide and driving advancements in technology and infrastructure [41]. Integral to numerous technologies, including smartphones, laptops, electric vehicles (EVs), and renewable energy storage, the global significance of the battery market is undeniable [42]. Moreover, batteries play a crucial role in the transition to renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, which rely on efficient energy storage solutions [43]. In this study, the selection of an appropriate battery is critical for the functionality and efficiency of the system.

As future scenarios become more complex, the need for larger-capacity batteries becomes increasingly critical. The onboard battery is required to support the stable operation of the MCU when multiple sensors are activated, either simultaneously or sequentially, to ensure uninterrupted data collection and processing. Considering these factors, the CR2032 battery, with a capacity of just 0.675 watt-hours [44], is clearly insufficient for applications that need ongoing observation, like food safety surveillance. This insufficiency highlights the necessity to explore alternative power sources that offer higher energy densities and longer life spans to meet the escalating demands of advanced electronic devices. Such advancements are essential for the sustainability and operational efficiency of next-generation technologies. Considering these requirements, AA-sized batteries were selected due to their greater energy capacity and compatibility with the system’s design. These batteries provide a significantly higher watt-hour rating compared to the CR2032, thereby enabling prolonged operation and more reliable performance of the MCU and the integrated sensors under demanding conditions. Ultimately, considering aspects such as environmental protection, sustainable development, and the need for compact design, green and rechargeable lithium batteries were selected as the optimal power source for this project. Lithium batteries offer superior energy density and rechargeability, supporting the project’s objectives of sustainability and long-term functionality. To further extend the operational lifespan beyond battery selection, a rigorous power control strategy was implemented in both circuit design and firmware: (1). Duty Cycling of Gas Sensors: Metal oxide gas sensors like the CCS811 typically require high current for their heating elements. To mitigate this, the sensor was configured to Drive Mode 3 (Low Power Pulse Heating Mode), which performs a measurement every 60 s. This reduces the average power consumption from the milliwatt range to the microwatt range, aligning with the slow biological progression of food spoilage. (2). Deep Sleep Implementation: Utilizing the PIC12LF1552’s extreme low power (XLP) architecture, the MCU enters a deep sleep state (consuming less than 50 nA) immediately after data packetization is complete. A watchdog timer is employed to wake the system strictly for the scheduled measurement intervals. (3). Peripheral Power Gating: The hardware circuit design minimizes leakage current by disabling the I2C pull-up resistors and putting the HDC2010 humidity sensor into a distinct standby mode (0.5 µA) when idle. This holistic approach ensures that the high energy density of the lithium battery is utilized efficiently.

3.4.2. Charging Circuitry

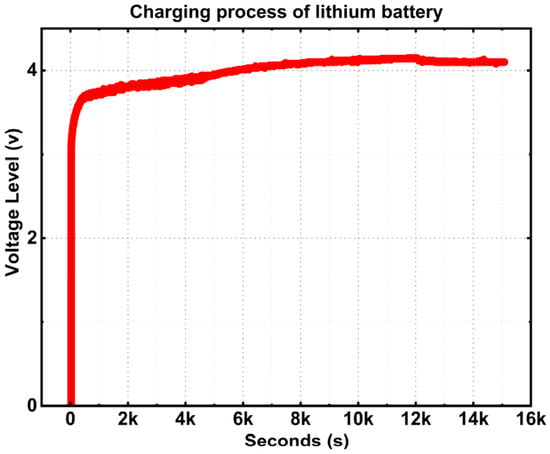

The proposed and developed semi-passive RFID tag-integrated charging circuit incorporates a charge management controller within the PCB. This controller optimizes the charging of rechargeable lithium batteries. This enhancement greatly improves operating dependability and prolongs the system’s lifespan. The tactile switch that lets the user quickly flip between charging and RFID detection modes is one notable feature of the design. By avoiding interference between the two operations, this innovation enhances both the efficiency of the charging process and RFID performance. The device also has two colored LEDs that show the operating readiness and charge state of the battery visually, making maintenance and monitoring easy. By lowering the demand for throwaway batteries, the system promotes environmental sustainability and guarantees an uninterrupted source of power for RFID tags. It works well with applications that need to function consistently over an extended period, such as inventory management and asset monitoring. Figure 4 presents the charging process of the battery. Since the battery has a built-in boost circuit, the battery voltage can instantly rise from 0 to 3.7 V during the initial period, until the battery voltage stabilizes at 4.1 V after being fully charged in 3.4 h.

Figure 4.

Charging performance of the lithium battery.

3.5. Investigation on Operation Time and Charging Time

An assessment of battery performance in a semi-passive RFID system with integrated charging circuitry is thoroughly made. CR2032 coin cells, AA batteries, and rechargeable lithium batteries are the three battery types that are examined in the study to ascertain how long they would last for a variety of sensing activities. This test compares endurance and reliability to identify the optimal battery type for different RFID applications. It is anticipated that the results will offer significant perspectives that will enhance the design of RFID systems, guarantee little downtime, and boost charging effectiveness.

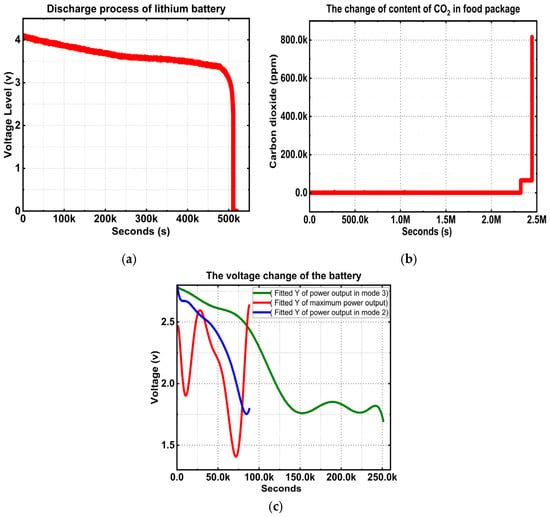

The voltage fluctuations for a button battery of the CR2032 type under real-life operation circumstances are shown in Figure 5c. This test distinguishes between three different modes of operation: mode 1 (for sampling data ten times per second), mode 2 (for sampling data once per second), and mode 3 (for sampling data once per minute). It is significant to note that readings obtained prior to this voltage threshold are the only ones displayed in the data, as the device components become unusable at voltages lower than 1.8 volts. It appears that the battery operates for the greatest amount of time in Mode 3, lasting around three days. Figure 5b illustrates the operational status of a sensor powered by two AA batteries, configured to mode 3. The sensor functioned optimally for up to 2,324,000 s, consistently registering a carbon dioxide concentration of 400 ppm, which corresponds to the average outdoor air level (0.04% of the air consists of carbon dioxide molecules). Beyond this point, due to insufficient battery voltage to support normal circuit operation, the sensor’s data registers defaulted to 1, resulting in abnormally high values being transmitted to the terminal. However, the battery life span under these conditions reached approximately 27 days, which is generally adequate for monitoring most types of food. The performance of the lithium battery is shown in Figure 5a under mode 2. After undergoing a gradual decline, the battery voltage abruptly drops to 0 volts from around 2.5 volts, and the battery is capable of sustaining circuit operations for a duration of up to six days. Based on these empirical results, the overall power consumption profile of the system can be quantified. Using the stable discharge period of the AA batteries (approx. 648 h with a standard 2500 mAh capacity) as a reference, the average power consumption of the complete system is estimated to be approximately 11.5 mW. This power profile is dominated by the periodic activation of the metal-oxide gas sensor (CCS811) and RF transmission bursts (reaching ~30 mA), while the MCU and semi-passive RFID module maintain minimal consumption (micro-ampere range) during sleep intervals. This analysis confirms that the proposed dual-mode power supply effectively manages the high energy demand of gas sensing, which is unattainable for passive tags.

Figure 5.

Battery performance of three types of batteries: (a) lithium battery; (b) AA battery; (c) CR2032.

4. RFID Sensor Implementation

4.1. Sensor Circuitry and RFID Platform

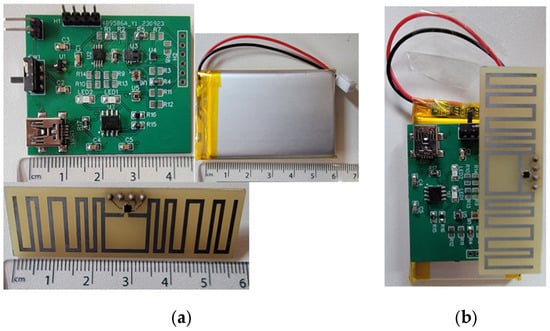

Figure 6a shows three main hardware parts of the fabricated semi-passive RFID integrated sensor and their sizes, including the battery, main PCB for data collection and processing, and antenna for RFID communication. The assembled hardware is shown in Figure 6b.

Figure 6.

Fabricated semi-passive RFID integrated multi-sensor: (a) sizes of each hardware; (b) appearance of assembled hardware.

In this design, the main PCB consists of a charging circuit with a micro-USB port for voltage supply and a sensing module integrated with three sensors, including gas, relative humidity, and temperature. In addition, an extension interface, a voltage input port for the battery, and a port for connecting the antenna are provided. The specifications of the sensors used in this research are presented in Table 1. To ensure the reliability of the specifications listed in Table 1, a comparative validation process was conducted prior to deployment. For temperature and humidity, the onboard HDC2010 sensor was cross-verified against a secondary reference sensor (AHT20) in a controlled chamber. The readings demonstrated high correlation, with deviations falling within the acceptable range (±0.3 °C and ±3% RH), confirming the baseline accuracy. Regarding the gas sensor (CCS811), verifying the absolute concentration of complex spoilage volatiles is challenging without invasive chromatography. Therefore, data reliability was established through experimental repeatability. Multiple identical sensor nodes were deployed in parallel meat packages under the same conditions. The high consistency of the observed gas accumulation trends across these trials confirms that the sensor outputs represent a stable and reproducible biological progression rather than random noise.

Table 1.

Specifications of sensors.

The rationale for selecting sensors with such high resolution lies in the requirement for early-stage spoilage prediction. Microbial metabolism in food generates volatile gases and heat, but these changes are minute during the initial lag phase. A standard resolution sensor might only trigger an alarm when spoilage is advanced and irreversible. In contrast, the 1 ppm resolution of the gas sensor enables the system to capture the ‘onset point’ of spoilage—the slight deviation from the baseline—providing valuable lead time for the AI model to predict shelf life. Furthermore, despite their high precision, these sensors employ MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) technology. Unlike laboratory-grade gas analyzers, which cost thousands of dollars, these MEMS sensors are mass-produced for the consumer electronics market, maintaining a low bill of materials cost that is economically feasible for item-level deployment in high-value food supply chains.

The logical integration between the sensor array and the RFID backscatter communication is achieved through a dual-interface shared memory architecture. The NXP UCODE I2C was selected as the RFID transponder chip, which supports both RF access and I2C access. During operation, the MCU wakes up periodically to poll the sensors via the I2C bus. The collected temperature, humidity, and gas concentration data are formatted into a hexadecimal string and written directly into the user memory bank of the RFID chip through the secondary I2C interface. Consequently, the external RFID reader does not require custom commands; it simply performs a standard ‘Read’ operation on the user memory bank to retrieve the latest environmental status. This method effectively decouples the sensing frequency from the reading frequency, ensuring data availability even when the reader is not present.

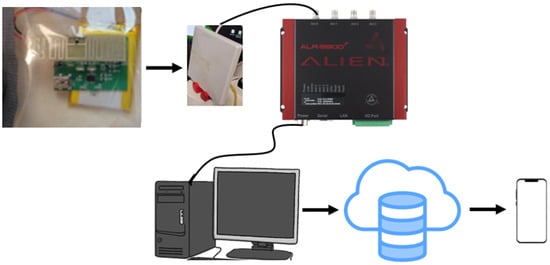

As Figure 7 shows, for the purpose of product QAS, food products are used for detection, and by using the Alien 9900+ UHF RFID reader (Alien Technology, Morgan Hill, CA, USA) with a 30 dBm output and a 5 dBi circularly polarized UHF RFID reader antenna made by Alien Technology, USA, the data are collected and preliminary processed by the local edge computing.

Figure 7.

Experimental setup for food quality monitoring.

To fully fulfil their promise in real-time monitoring and decision-making processes, semi-passive RFID devices require robust data management and accessibility. An Internet of Things (IoT) platform designed expressly to achieve these goals has been developed. This platform provides full data storage, processing, and visualization capabilities by serving as a central repository for all RFID reader data. Users can access the platform and analyze large datasets in an intuitive graphical format via a secure login interface.

Furthermore, this IoT platform’s usability is further increased with the addition of a specially designed mobile application. Users can remotely monitor data and control the system due to the application’s straightforward platform access. For users who are constantly on the go and need to make choices quickly based on the most recent information from their RFID systems, this mobile functionality is quite helpful. The app ensures users have all the information they need at their fingertips, with features including real-time data streaming, system alert notifications, and capabilities for in-depth data analysis.

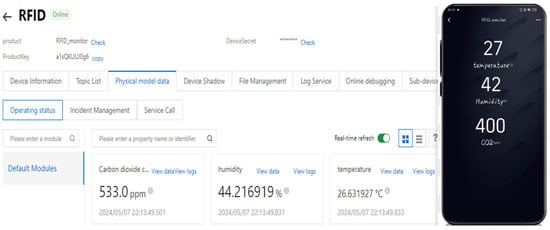

4.2. AIoT Big Data Platform

The visualization shown in Figure 8 is the front-end representation of a robust backend architecture hosted on the Alibaba Cloud IoT Platform. The underlying technology relies on a Publish/Subscribe messaging model utilizing the MQTT protocol. Specifically, the RFID reader acts as an edge gateway, encapsulating the raw sensor data (Temperature, Humidity, carbon dioxide) into a standardized JSON payload. This payload is published to a specific cloud topic. The cloud platform then parses this JSON data to update the ‘Device Shadow’—a virtual JSON document dynamically representing the state of the physical sensor. The mobile application and web dashboard shown in the figure maintain a persistent WebSocket connection to this Device Shadow, allowing for the millisecond-level real-time synchronization of data curves and numerical values observed in the interface.

Figure 8.

IoT platforms on website and mobile phone.

The platform features a simple and clear interface that allows users to access, visualize, and analyze data from desktop computers and mobile devices. This dual accessibility ensures users have the flexibility to interact with their data, choosing the device that best suits their needs at any time. In addition, mobile applications developed specifically for this platform provide greater user convenience by providing real-time data updates and mobile phone information notifications. The application ensures that users stay connected to their data, thereby helping to respond immediately to the occurrence of any abnormal data. The IoT platform proposed in this study can be regarded as a key tool in the field of RFID applications, aiming to achieve efficient data processing. The platform is also well-suited for a variety of RFID applications, including asset tracking, inventory management, and environmental monitoring, to provide accurate data collection and instant access.

4.3. AI Embedded

To support intelligent decision-making and predictive analytics, the proposed AIoT platform incorporates a machine learning module for real-time shelf-life estimation based on time-series sensor data. To accurately predict the spoilage trend, a Stacked Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network was constructed using the TensorFlow/Keras framework. The algorithmic implementation proceeds in three stages: (1) Data Preprocessing: The raw multi-variate sensor data (Carbon dioxide, Temperature, Humidity) are first normalized using min–max scaling to the range [0, 1]. A sliding window approach (sequence length = 10 time steps) is applied to transform the time-series data into supervised learning sequences. The dataset is then strictly partitioned into 80% for training and 20% for testing without shuffling, preserving the temporal order of the series. (2) Model Architecture: The proposed model features a progressively narrowing architecture to extract hierarchical features. It consists of a first LSTM layer with 64 neurons (returning sequences), followed by a second LSTM layer with 32 neurons. The output is then fed into a fully connected (Dense) layer with 16 neurons (ReLU activation) before reaching the final output layer. (3) Training Configuration: The model is trained for 50 epochs with a batch size of 32, utilizing the Adam optimizer. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) serves as the loss function during the training process. To strictly quantify the prediction performance, the Coefficient of Determination (R2) and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) are calculated on the inverse-transformed (unscaled) test data to reflect the real-world accuracy of the system.

Once validated, the trained LSTM model is deployed within the IoT cloud architecture to estimate the remaining shelf life in real time. The system is configured to trigger immediate alerts when the predicted spoilage index exceeds safety thresholds. This capability effectively transforms the system from a passive monitoring tool into a proactive predictive analytics platform. Figure 9 illustrates this complete data processing pipeline. Regarding the experimental data acquisition, the three key parameters—temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide concentration—were continuously transmitted to the AIoT platform over a six-day period. The sampling interval was set to one second to capture minute metabolic changes. Throughout this duration, the stable MQTT connectivity ensured zero data loss, maintaining full consistency between the edge sensors and the cloud database visualization shown in the web and mobile interfaces.

Figure 9.

The whole process of processing data using AI.

5. Results and Discussions

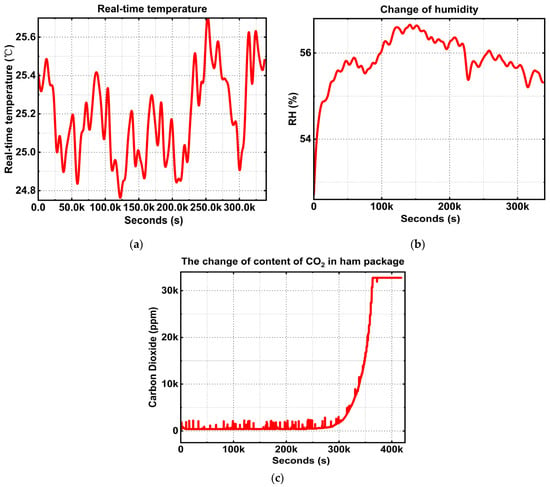

To validate the system’s performance, a spoilage test was conducted on a sealed meat product. The experiment was performed in a controlled laboratory environment with a constant ambient temperature of 25 °C to isolate internal metabolic changes from external weather fluctuations. As shown in Figure 10a,b, despite the constant external environment, the internal package temperature rose by approximately 0.8 °C, and relative humidity increased by 4%. These variations are attributed to the heat and moisture generated by microbial aerobic respiration. Figure 10c illustrates the drastic rise in equivalent carbon dioxide concentration. A significant surge is observed around the 300,000th second, marking the onset of rapid spoilage. It is important to note that the final flatline in the carbon dioxide graph represents the sensor’s saturation point (maximum detection limit), indicating that the actual concentration inside the package had exceeded the sensor’s dynamic range due to severe decomposition. The proposed semi-passive RFID integrated sensor can thus offer item-level and environmental sensing for the food industry.

Figure 10.

Collected data: (a) temperature; (b) relative humidity; (c) CO2 concentration.

Beyond the numerical values, these experimental results provide profound insights into the system’s potential for industrial application. Firstly, the ability to capture the sharp ‘inflection point’ of carbon dioxide concentration demonstrates the early warning capability of the platform; the system detected significant metabolic activity well before visual signs of spoilage appeared, confirming its superiority over traditional static expiration dates. Secondly, the seamless continuity of the uploaded data over the six-day period verifies the robustness of the AIoT architecture, proving that the proposed semi-passive design can maintain stable MQTT connectivity without data loss. Finally, the successful comprehensive recording of the spoilage process validates the energy efficiency of the hardware, as the dual-mode power supply effectively supported the energy-intensive gas sensor throughout the entire monitoring lifecycle.

6. Conclusions

In summary, this study presents a UHF RFID tag-integrated multi-sensor system with an AIoT platform. By utilizing RFID tag-integrated sensors and an AIoT platform, the study demonstrates potential for flexible, timely, and cost-effective multi-sensor data storage, analysis, and visualization. Notably, the compact size and low power consumption of the semi-passive RFID sensing circuitry make it suitable for long-term sensing and parameter monitoring in confined spaces.

Furthermore, the integration of the AI-driven predictive model (LSTM) distinguishes this work from traditional identification-focused RFID systems. By successfully processing time-series data from semi-passive sensors to predict spoilage trends, the proposed solution shifts the paradigm from reactive monitoring to proactive quality management. This synergistic approach—combining low-power hardware, cloud architecture, and intelligent analytics—provides a novel and scalable reference architecture for the next generation of smart food supply chains.

Author Contributions

Z.C. contributes to the design and implementation of the sensors and AIoT platform. Z.W. and J.G. contribute to the overall design of the RFID and AIoT systems. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lang, T.; Barling, D. Food security and food sustainability: Reformulating the debate. Geogr. J. 2012, 178, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Wu, Z.; Gray, J.; Meng, Z. An RFID-Powered Multi-Sensing Fusion Industrial IoT System for Food Quality Assessment and Sensing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 20, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunamurthy, A.; Yuvaraj, M.; Shahithya, J.; Thenmozhi, V. Cloud Database: Empowering Scalable and Flexible Data Management. Quing Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. 2023, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Alam, M.A. Comparative Study of Traditional Database and Cloud Computing Database. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Sci. 2017, 8, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, C.; Castiglione, A.; Frattini, F.; Cinque, M.; Yang, Y.; Choo, K.K. On data sovereignty in cloud-based computation offloading for smart cities applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 6, 4521–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RFID Standard. Available online: https://www.gs1.org/sites/default/files/docs/epc/uhfc1g2_2_0_0_standard_20131101.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Zoughi, R. Microwave Non-Destructive Testing and Evaluation Principles; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnadottir, S.G.; Lunde, K.; Alvseike, O.; Mason, A.; Al-Shamma’a, A. Assessing quality parameters in dry-cured ham using microwave spectroscopy. Meat Sci. 2015, 108, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmer, O.; Daschner, F.; Knochel, R. UWB-sensors in food quality management—The way from the concept to market. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Ultra-Wideband, Hannover, Germany, 10–12 September 2008; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Z.; Wu, Z.; Gray, J. Microwave sensor technologies for food evaluation and analysis: Methods, challenges and solutions. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2018, 40, 3433–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulloni, V.; Marchi, G.; Gaiardo, A.; Valt, M.; Donelli, M.; Lorenzelli, L. Applications of chipless RFID humidity sensors to smart packaging solutions. Sensors 2024, 24, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Feng, J.; Gameiro, M.G.; Tian, Y.; Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ding, J.; He, Q. RFID-based sensing in smart packaging for food applications: A review. Futur. Foods 2022, 6, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Srinivasan, K. RFDrive: Tagged Human-Vehicle Interaction for All. ACM J. Comput. Sustain. Soc. 2024, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juels, A.; Rivest, R.L.; Szydlo, M. The blocker tag: Selective blocking of RFID tags for consumer privacy. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Washingtion, DC, USA, 27–30 October 2003; pp. 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Feng, Q.; Fan, T.; Lei, Q. RFID technology and its applications in Internet of Things (IoT). In Proceedings of the 2012 2nd International Conference on Consumer Electronics, Communications and Networks (CECNet), Yichang, China, 21–23 April 2012; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 1282–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Faghri, A.; Li, X.; Bahrami, H. Recent advances in passive and semi-passive direct methanol fuel cells. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2012, 62, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colella, R.; Sabina, S.; Mincarone, P.; Catarinucci, L. Semi-passive RFID electronic devices with on-chip sensor fusion capabilities for motion capture and biomechanical analysis. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 11672–11681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; He, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X.; Fu, Z.; Zuo, L. Design of an embedded CMOS temperature sensor for passive RFID tag chips. Sensors 2015, 15, 11442–11453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Occhiuzzi, C.; Rida, A.; Marrocco, G.; Tentzeris, M. RFID passive gas sensor integrating carbon nanotubes. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2011, 59, 2674–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, L.T.; Chen, M.; Zhao, S.; Guo, M.; Zhang, Y. Real-time locating systems using active RFID for Internet of Things. IEEE Syst. J. 2014, 10, 1226–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, T.; Jansen, D.; Speletz, H.; Fleiner, B.; Bau, D.; Kreker, A.; Riske, A. Active RFID sensor with integrated file system for logistic applications. In Proceedings of the European Workshop on Smart Objects: Systems, Technologies and Applications, Ciudad, Spain, 15–16 June 2010; VDE: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Solar, H.; Beriain, A.; Berenguer, R.; Sosa, J.; Montiel-Nelson, J.A. Semi-passive UHF RFID sensor tags: A comprehensive review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 135583–135599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, W.; Naeem, M.; Zeadally, S. On-demand sensing and wireless power transfer for self-sustainable industrial internet of things networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 7075–7084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedermann, R.; Lang, W. Semi-passive RFID and beyond: Steps towards automated quality tracing in the food chain. Int. J. Radio Freq. Identif. Technol. Appl. 2007, 1, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Mao, L.; Chen, L.; Xie, S. Locatable-body temperature monitoring based on semi-active UHF RFID tags. Sensors 2014, 14, 5952–5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Li, Z. RFID tag as a sensor-a review on the innovative designs and applications. Meas. Sci. Rev. 2016, 16, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounsi, W. Security and Privacy Controls in RFID Systems Applied to EPCglobal Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Brest, Brest, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Athalye, A.; Savic, V.; Bolic, M.; Djuric, P.M. Novel semi-passive RFID system for indoor localization. IEEE Sens. J. 2012, 13, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Mei, N.; Zhang, Z. A UHF semi-passive RFID system with photovoltaic/thermoelectric energy harvesting for wireless sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 13th International Conference on ASIC (ASICON), Chongqing, China, 29 October–1 November 2019; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Feldhofer, M.; Aigner, M.; Baier, T.; Hutter, M.; Plos, T.; Wenger, E. Semi-passive RFID development platform for implementing and attacking security tags. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions, London, UK, 8–10 November 2010; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.M.; Feng, P.; Wu, N.J. Passive and semi-passive wireless temperature and humidity sensors based on epc generation-2 uhf protocol. IEEE Sens. J. 2014, 15, 2403–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, A.; Hanhikorpi, M.; Bertuccelli, F.; Colonna, A.; Malik, W.; Ranasinghe, D.; López, T.S.; Yan, N.; Tavilampi, M. Sensor-Enabled RFID Tag Handbook; IST-2005; BRIDGE: Brussels, Belgium, 2008; p. 33546. [Google Scholar]

- Deleawe, S.; Kusznir, J.; Lamb, B.; Cook, D.J. Predicting air quality in smart environments. J. Ambient. Intell. Smart Environ. 2010, 2, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Mihara, K.; Wen, J. Time series prediction of CO2, TVOC and HCHO based on machine learning at different sampling points. Build. Environ. 2018, 146, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, W.; Vong, C.; Yang, J.; Wong, P. Least squares support vector prediction for daily atmospheric pollutant level. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/ACIS 9th International Conference on Computer and Information Science, Yamagata, Japan, 18–20 August 2010; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yan, F.; Li, B.; Yu, B.; Zhou, X.; Tang, X.; Jia, T.; Lv, C. A Multimodal Data Fusion and Embedding Attention Mechanism-Based Method for Eggplant Disease Detection. Plants 2025, 14, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar, R.K.; Bhatia, S.; Papenja, R. Comparison of WWW security Protocols: Secure Sockets Layer (SSL), Transport Layer Security (TLS), & Secure HTIP (S-HTIP). Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2013, 4, 443–447. [Google Scholar]

- Dikii, D.I. Remote Access Control Model for MQTT Protocol. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference of Russian Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (EIConRus), Moscow, Russia, 27–30 January 2020; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 288–291. [Google Scholar]

- Janek, A.; Steger, C.; Preishuber-Pfluegl, J.; Pistauer, M. Power management strategies for battery-driven higher Class UHF RFID tags supported by energy harvesting devices. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Workshop on Automatic Identification Advanced Technologies, Alghero, Italy, 7–8 June 2007; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Janek, A.; Steger, C.; Weiss, R.; Preishuber-Pfluegl, J.; Pistauer, M. Lifetime extension of semi-passive UHF RFID tags using special power management techniques and energy harvesting devices. In Proceedings of the AFRICON 2007, Windhoek, South Africa, 26–28 September 2007; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Pohl, O.; Bhatt, A.I.; Collis, G.E.; Mahon, P.J.; Rüther, T.; Hollenkamp, A.F. A review on battery market trends, second-life reuse, and recycling. Sustain. Chem. 2021, 2, 167–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, C. Lithium-ion battery costs and market. Bloom. New Energy Financ. 2017, 5, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, U.; Kalam, A.; Shi, J. A review of key functionalities of battery energy storage system in renewable energy integrated power systems. Energy Storage 2021, 3, e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CR2032. Available online: https://www.farnell.com/datasheets/2612182.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.