Abstract

With the improvement of the internet and the widespread adoption of digital communication devices such as smartphones, VoIP has largely replaced traditional telephone systems. Many companies are deploying VoIP systems due to their scalability and low cost. In this paper, we address the issue of remote clients or traveling employees being unable to contact business partners due to specific phone numbers. We propose a reference phone number mechanism that combines a set of related business partners’ phone numbers to enhance call availability. To ensure the confidentiality of calls, we also designed an algorithm to integrate key exchange protocols into the proposed mechanism. The mechanism can flexibly customize the required security protocols. A performance analysis was conducted by deploying the proposed mechanism in a medium-sized company. The results prove that the mechanism is feasible and the effect is satisfactory.

1. Introduction

With the widespread deployment of optical fiber lines in wired networks and the vigorous development of 4G/5G mobile networks, the bandwidth of networks has increased significantly. Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) has almost replaced traditional phone systems such as the analog PBX phone system. People who own smartphones have mobile numbers, but in order to save communication costs, they still prefer to communicate through VoIP applications installed in their smartphones. Many companies have also deployed VoIP systems to reduce operating costs, especially for multinational companies that require overseas phone calls or video conferencing. Moreover, VoIP also provides scalability, allowing growing businesses to expand their branches and employees. The portability of virtual phone numbers like in VoIP applications also brings convenience to employees who frequently travel. In order to provide a stable and versatile method to perform the VoIP, many protocols have been invented to support VoIP services, such as H.323 [1], the Media Gateway Control Protocol (MGCP) [2], and SIP. Among all these protocols, 3GPP defines SIP [3] as one of the most important signaling protocols for the VoIP, because SIP has many advantages such as ease of implementation, support for multimedia communications, modularity, and extensibility. SIP has user-friendly syntax and operations similar to HTTP, making it rapid to understand and deploy. SIP supports multimedia communication sessions, including voice, video, instant messaging, and presence. The modular architecture of SIP allows for the addition of new features and functionalities through extensions and adjustments.

2. Background and Motivation

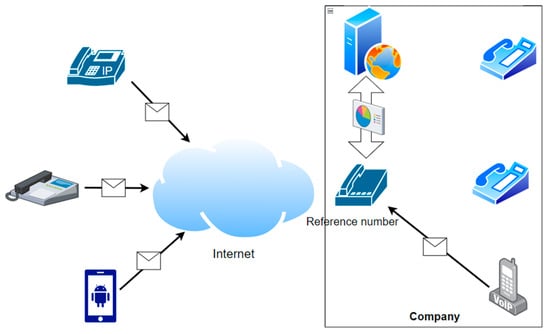

There has been a long-standing demand for secure VoIP communication between private companies and public institutions. Therefore, numerous encryption mechanisms have been designed and adopted to protect end-to-end communication. These encryption mechanisms require the establishment of a session between two user agents, in which the two user agents exchange certificates containing their public keys. That is, callers must remember the callee’s phone number to initiate a dial-up call. This presents a significant inconvenience for users who must communicate with a large number of customers or colleagues, as well as for engineers who are traveling or working remotely and need to temporarily reach out to operators in the data center. To offer users more convenient VoIP services, the need for virtual reference phone numbers arises. Figure 1 illustrates the demand structure. The diagram is drawn based on our real-world application scenario. Incoming and outgoing calls will be routed through a VoIP exchange, which manages reference numbers to efficiently establish calls. Within the company, the deployment is straightforward, as all telephone devices are wired to VoIP gateways, which connect to the exchange. Outside the company, users can initiate call setup using wired or wireless VoIP devices. Wired phone devices communicate through the internet provided by the local ISP, which is generally more stable. However, although wireless phone devices also rely on the internet provided by the local ISP, their operating environments are more complex, such as basements, elevators, vessels, and mountainous areas, which may increase the risk of call setup failure. Therefore, this paper focuses on the effectiveness of the reference number mechanism, while the influence of wireless end devices is beyond the scope of discussion. The reference phone numbers are virtual, meaning corresponding physical certificates cannot be exchanged to negotiate session keys. Therefore, to address this need, this article makes the following contributions:

Figure 1.

A virtual reference phone number to physical VoIP numbers.

- We propose a mechanism for converting reference phone numbers to physical phone numbers and demonstrated its feasibility by implementing the mechanism.

- After deployment and application, as well as the statistical data analysis in this paper, the call success rate proves to be efficient and meets users’ expectations.

- The proposed mechanism is universal, meaning users have the flexibility to replace the key agreement algorithm or VoIP protocol with their preferred choices.

The structure of this article is as follows. Section 3 describes the necessary knowledge and related work. In Section 4, we propose architecture employing algorithmic reference phone numbers. The performance of the proposed approach is shown in Section 5, along with a discussion of its benefits and drawbacks. Section 6 concludes the work as well as some ideas for future research.

3. Preliminary and Related Work

3.1. SIP Overview

Table 200. OK to confirm session settings. A SIP transaction refers to a set of messages comprising a request and its associated response.

SIP message forwarding (called proxying) is a key feature of the SIP infrastructure. This forwarding process is provided by the proxy server and can be stateless or stateful. Stateless proxies do not maintain state information about SIP sessions and therefore tend to be more scalable. However, many standard application features, such as authentication, authorization, accounting, and call forking, require the proxy server to operate in a stateful mode by retaining different levels of session state information.

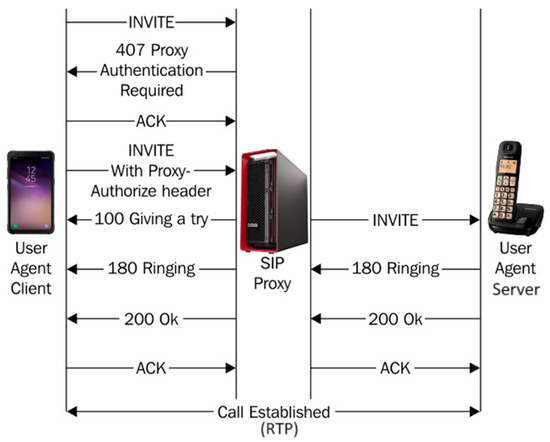

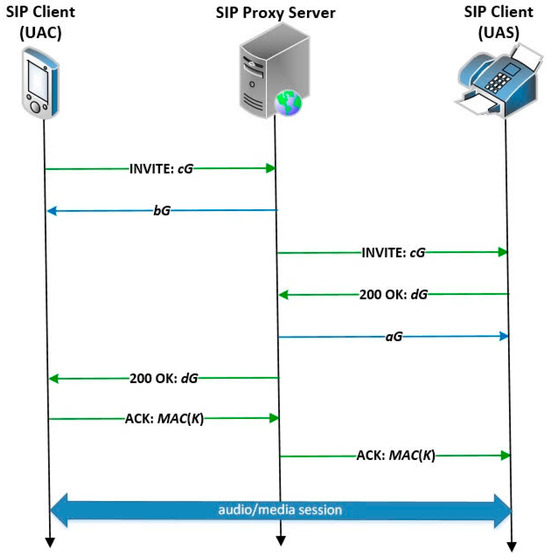

A typical message flow for a SIP proxy state with authentication enabled is shown in Figure 2. Two SIP user agents, designated as User Agent Client (UAC) and User Agent Server (UAS), represent the roles of caller and callee in a multimedia session. In this example [4,5], the UAC wants to establish a connection with the UAS and send an INVITE message to the agent. The proxy server responds with a 407 Proxy Authentication required session message to enforce proxy authentication, requiring the UAC to provide credentials to verify its claimed identity (e.g., based on the MD5 [6] digest algorithm). The UAC then retransmits the INVITE message and includes the generated credential in the Authorization header. After the proxy receives and verifies the UAC credential, it will send a 100 TRYING message to notify the UAC that the message has been received, and there is no need to worry about hop-by-hop retransmission. The proxy then looks for the contact address of the UAS’s SIP URI and, if available, forwards the message. In turn, the UAS acknowledges receipt of the INVITE message with a 180 RINGING message and causes the callee’s phone to ring. When the called party actually picks up the phone, the UAS returns 200 OK. Both the 180 RINGING and 200 OK messages are sent back to the UAC through the proxy.

Figure 2.

SIP stateful proxy for authentication.

The UAC then acknowledges the 200 OK message with an ACK message. After establishing a session, the two endpoints communicate directly point-to-point using media protocols such as RTP [7].

SIP proxy authentication is optional and usually occurs between the UA and its first-hop SIP proxy server. While the example above depicts a single SIP proxy on the path, in reality, multiple proxy servers often exist in the signal path. The message flow for multi-proxy servers is similar, except that proxy authentication usually only applies to the first hop.

3.2. RTP Overview

The Real-Time Transport Protocol (RTP) [5,8] defines a standardized packet format for transmitting audio and video over IP networks. RTP is widely used in communications and entertainment systems involving streaming media, such as telephones, video conferencing applications, television services, and web-based push-to-talk capabilities (Figure 1). Applications often run RTP on top of UDP to take advantage of its multiplexing and checksum services; both protocols contribute part of the functionality of the transport protocol.

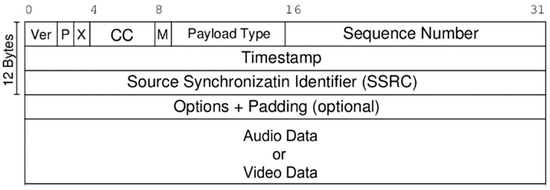

In addition, RTP is also used in conjunction with the RTP Control Protocol (RTCP). RTP carries media streams, while RTCP is used to monitor transmission statistics and quality of service (QoS) and to assist in the synchronization of multiple streams. RTP is initiated and received on even port numbers, and associated RTCP communications use the next higher odd port number. The RTP header has a minimum size of 12 bytes that can be increased with optional fields. The RTP header specification is shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

The location of RTP/RTCP in the protocol stack.

The payload type (PT) is a 7 bit field that indicates the format of the payload and determines its interpretation by applications. For example, when the value is assigned to 18, the audio codec uses G.729, and when the value is assigned to 34, the media codec uses H.323. In order to meet diverse encoding algorithms, it now also supports the dynamic binding of PT to media encoding. This means that before the establishment of an RTP session, the PT value used and its corresponding encoding format are specified. The audio/video data payload carries audio samples or compressed video data for playing audio and video services.

3.3. Related Work

Since SIP plays an important role in VoIP communications, the security of its application has also attracted the attention of researchers. To protect privacy and confidentiality, many studies have been proposed to validate UAS/UAC and encrypted RTP payloads.

In 2016, Zhang et al. [9] introduced an authentication protocol for SIP using smartcards and elliptic curve cryptography. This protocol eliminates the need for the SIP server to store passwords or verification tables, reducing energy consumption. Azrour et al. [10] used chaotic maps and smartcards to propose an efficient SIP authentication and key agreement protocol. However, modern communication devices no longer include smart cards. Meanwhile, Chaudhry et al. developed a lightweight privacy-preserving authentication and key agreement protocol [11] for SIP. Elliptic curve cryptography is utilized in their protocol to provide mutual authentication as well as to protect all known attacks, such as server impersonation attacks. Nikooghadam et al. [12] later performed a cryptanalysis of Chaudry et al.’s protocol and pointed out its weaknesses against offline password-guessing attacks. An improved lightweight authentication protocol was proposed to overcome the weaknesses of Chaudry et al.’s proposed protocol. They also used BAN logic [13] to prove the correctness of the proposed protocol. However, in 2019, Ravanbakhsh et al. [14] found that the protocol proposed by Nikooghadam et al. was insecure due to the lack of perfect forward secrecy [15]. Therefore, they presented an efficient two-factor authentication and key agreement protocol and used the AVISPA tool [16] to prove that it can defend against various active and passive attacks. Nevertheless, Nikooghadam et al. [17] proved that Ravanbakhsh et al.’s protocol did not provide perfect forward secrecy. Next, they proposed a secure two-factor authentication and key agreement scheme based on elliptic curve cryptography. They used the Scyther tool [18] to simulate and analyze the protocol to formally prove its robustness and security. In 2020, an advancement of an authenticated key agreement protocol for SIP, based on Dongqing et al.’s scheme [19], was introduced by Mahamood et al. [20]. Mahamood et al.’s scheme supports running over a WLAN or WAN but was found to be vulnerable to privileged insider attacks and secret disclosure. Furthermore, strict time synchronization is impractical in the real world.

However, the aforementioned protocols have all been analyzed for their security and performance theoretically, without being put into practice or applied in the real world. VOCAL Technologies, Ltd. (Buffalo, U.S.) [21] adheres to the standards outlined in RFC 3261 [3] and RFC 3329 [22] for implementing SIP-based VoIP services over TLS. SIPTRUNK [23] not only provides TLS security but also uses Real-Time Protocol (SRTP) [24] to secure the media sent during the connection. Leu et al. [25] establishes secure VoIP communication via SIP across wireless networks. Their protocol employs ECMQV for generating session keys to safeguard media packets and utilizes TLS to secure SIP signals. Despite this, none of these solutions provide the functionality mentioned in Section 2, providing convenient services. Therefore, in this study, we propose a mechanism that not only resolves this issue but also enhances the user-friendly aspect of VoIP services.

In 2022, Vicente Mayor et al. [26] introduced a framework integrating Voice over WiFi (VoWiFi) with Public Switched Telephone Networks (PSTNs) using their proposed Unified Call Admission Control (U-CAC) method. However, it cannot provide any encryption mechanism that will impact traffic analysis methods that the U-CAC system relies on. The architecture of VoWiFi to PSTN is exactly opposite to ours, which addresses more generalized issues. After that, Vicente Mayor et al. [27] further presented the Codec-Optimization CAC (CO-CAC) mechanism for VoIP in 5G/WiFi relay networks, optimizing codec settings dynamically to maximize the number of concurrent calls while maintaining acceptable speech quality. However, it is designed for scenarios where UAVs provide WiFi access and relay calls to a 5G backhaul network. Md Mehedi Hasan et al. [28] focused on ensuring QoS while exploring adaptive CAC mechanisms that dynamically reserve bandwidth to maintain service quality under high-load conditions in LTE and 5G networks. Nevertheless, none of the aforementioned approaches address the issue highlighted in this paper.

4. Proposed Method

4.1. The Architecture

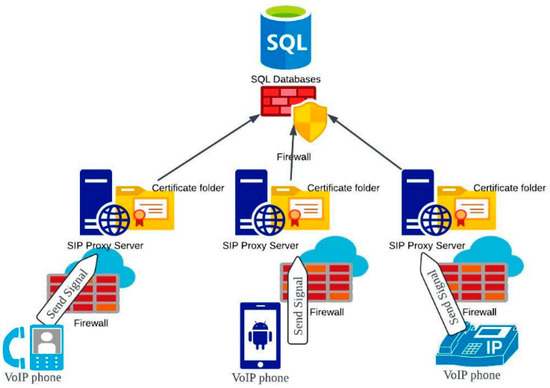

We implemented a realistic framework, as shown in Figure 4, to verify the practicality of the proposed mechanism and analyze its performance. The fundamental idea is comparable to that of a SIP proxy server that is commonly deployed. In order to establish a call session, each SIP proxy server provides authentication, grants access, and routes call setup signals to other servers where the callee is registered. Additionally, each SIP proxy server contains a directory that houses all user certificates, including the public key. The database containing information on SIP servers, agents, and related data is protected by a firewall. Communication ports have been modified to help prevent attacks targeted to compromise standard SQL and SIP settings. VoIP end devices register with the SIP proxy server over the Internet and set up a Transport Layer Security (TLS) tunnel before sending SIP signals. Additionally, each VoIP end device has a private key stored in secure memory.

Figure 4.

A realistic operational framework.

4.2. Algorithms

In order to protect the confidentiality of the session, we referred to [26] and adopted the ECMQV algorithm [29] to be integrated into the SIP protocol. The symbols, algorithm, and integrated protocol are illustrated in Table 1, Algorithm 1, and Figure 5, respectively.

| Algorithm 1: ECMQV algorithm |

| Input: A set of domain parameters (#E(Fp), q, h, G), private keys (a, c), and public keys (aG, cG, bG, dG) Output: A session key K

|

Table 1.

Domain parameters in elliptic curve cryptography.

Figure 5.

The standard SIP protocol integrates the ECMQV algorithm.

As shown in Figure 5, the caller sends a SIP invite message containing his/her ephemeral public key cG. A SIP proxy server checks its database and the directory containing public keys. If the callee exists, the SIP proxy server will respond to the caller with the callee’s static public key (bG) and forward the INVITE message to the callee. After receiving the INVITE message, the callee will reply with a SIP 200 OK message including his/her ephemeral public key dG. The SIP proxy server will return the caller’s static public key (aG) to the callee and transfer the 200 OK message to the caller. The caller uses the callee’s temporary and static public key received from the SIP proxy server paired with its own long- and short-term private key to calculate the Q-point. The session key K is then generated by hashing the extracted x-coordinate of the Q point. Finally, the caller sends the message authentication code of the session key MAC(K) which is produced by encrypting 16 bytes of zeros. The callee verifies the MAC by calculating the common session key.

Next, the pseudocode proposed in Algorithm 2 is used to solve the virtual reference phone number that does not have a corresponding public key. When a caller dials a reference phone number, the SIP proxy server searches for the group it represents. For example, a reference phone number 77777 may represent a group of numbers (70001, 70002, 70003, or 70004) with related services. If the SIP proxy server cannot find its group, the number may be wrong, and Algorithm 2 returns 0, which will be converted into an SIP 404 Not Found message to the caller. If the group exists, the algorithm checks the status of the numbers in the group one by one. When the algorithm finds an available number, then it searches the directory for the corresponding certificate. If the certificate is not found, −1 is returned, which is converted into an SIP 403 Forbidden message. If all the conditions are met, the number is passed back to the SIP proxy server; otherwise, the SIP proxy server will obtain 1 and interpret it as an SIP 486 Busy message. As a result, when the SIP proxy server obtains an available number n, it will send the static public key of n to the caller and proceed with the process, as illustrated in Figure 5.

| Algorithm 2: Reference Phone Number algorithm |

| Input: A reference phone number R Output: A real number n or 1 or 0

|

5. Result Analysis and Performance Comparison

5.1. Result Analysis

The experimental environment was set up as follows. A hypervisor VMware ESXi 6.5 was installed and configured on a 1U rack Dell PowerEdge R450 server with DDR4-2400 64 GB Memory and Intel Xeon Silver 4210 2.20 GHz, 10 cores. Then, we created and configured five virtual machines on the ESXi management console, including four SIP proxy servers and one RTP relay server running on the Ubuntu 18.04 operating system. The SIP proxy server was developed and modified from the free open-source framework—Asterisk. A MySQL database virtual machine was created using a 1U rack Dell PowerEdge R350 server with Intel Xeon E-2300 3.1G 8 cores and DDR4-3200 16 GB, and the virtual machine hypervisor VMware ESXi 6.5 was installed.

The deployment of terminal devices has become complex due to the presence of wired and wireless (mobile) equipment. The smartphone model was the HTC U20, equipped with a MicroSD card that has encryption capabilities, and we installed a customized VoIP application designed by us. The conceptual diagram is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

This schematic illustrates that the smartphone is equipped with a MicroSD card featuring encryption capabilities. For details, refer to [30].

A wired desk phone connects to a custom VoIP gateway equipped with a Hardware Security Module (HSM) for key exchange and encryption. The conceptual diagram is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

This schematic illustrates a VoIP phone connecting to a VoIP gateway equipped with HSM. For details, refer to [31].

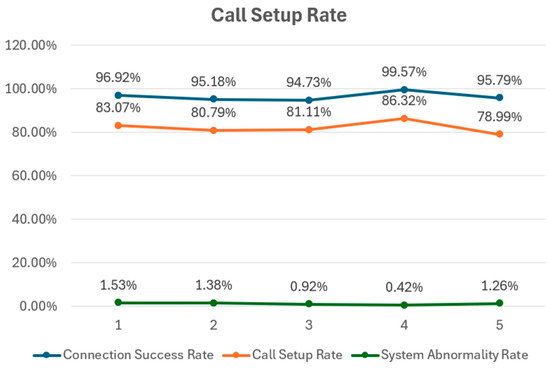

The proposed system was deployed in an organization with more than 200 employees. The statistical results of call establishment success are presented in Table 2. The author divided the status of calls into 12 categories. “Successful Call Setup” means that the communicating parties successfully conducted a conversation. “Missed Call” means the called party did not answer the call. “Line Busy” indicates that the callee’s line was currently in use or occupied. “Offline” means that the callee was not registered to the SIP proxy server. “Callee No Response” means that the SIP proxy server forwarded the INVITE signal to the callee, but the callee did not respond for some unknown reason. “Wrong Number” means the caller dialed a phone number that does not exist. “Call Rejected” means the callee hung up the phone directly. “Call Forbidden” means the callee’s account was illegal or the callee’s certificate did not exist. “System Service Abnormality” means that the SIP proxy server could not process SIP signals normally. “ACK timeout” refers to the situation where, after receiving an SIP 200 OK response, the system waited for the final SIP ACK signal for a duration that exceeded the specified time limit. “Unstable Network, Msg Lost” indicates that the SIP signal was lost or could not be successfully delivered due to unstable network conditions. All remaining cases are classified as “Other” status. The statistical data collection period was from 15 to 19 January. In order to evaluate the trend changes, the “Connection Success Rate” is defined as the following equation,

and the equation for “Call Setup Rate” is defined as follows.

Table 2.

Statistics of call status.

Additionally, the equation of “System Abnormality Rate” is defined below.

The trend of call success rate is shown in Figure 8, the call connection success rate is as high as over 95%, which means users could smoothly access services and initiate calls. As we can see, the call was not dialed to a specific callee, but to a reference phone number that multiple callees could respond to. As a result, callers experienced fewer busy lines. However, an idle number does not guarantee that the callee was necessarily available at their seat, so there is still a possibility that missed calls happened. Since the caller may have been in an unstable or poor network environment, and SIP signals may have sometimes been lost. States 4 and 10 can be classified as the aforementioned situations. Definitely, even with a reference phone number, callers may have still dialled the wrong number. Overall, the probability that users were able to find the callee and establish a call is about 80%, indicating that customers or employees traveling abroad would usually be able to reach a business partner when making a phone call, thereby improving service satisfaction.

Figure 8.

Statistical trend line chart.

5.2. Performace Comparison

- (1)

- Call success rate

In [26], the percentage of successful calls is simply defined as follows:

where is the number of successful/acceptable calls, is the number of calls admitted by call admission control (CAC), and is the number of calls rejected by CAC.

The result shows that CAC mechanisms significantly improve call success rates compared to systems without admission control. With a unified CAC in basic mode, it maintained a 40% success rate for 80 users. With a unified CAC in advanced mode, there was a 0% call failure for 80 users, meaning all calls succeeded.

In [27], the call success rate is calculated as follows:

where refers to the number of calls accepted by CO-CAC, refers to calls canceled due to falling below the minimum speech quality threshold, and is the total number of calls made during the simulation.

The results indicate that for 0 to 50 users, the success rate remained at nearly 100%, as the network was not congested. In the range of 50 to 100 users, the system maintained an almost perfect success rate by dynamically adjusting bandwidth allocation. However, as the number of users increased to 100–200, the success rate gradually declined due to call rejections caused by network limitations. Beyond 200 users, approximately 30% of call attempts were rejected as the system reached its capacity limits.

U-CAC [26] and CO-CAC [27] operate in fundamentally different environments—CO-CAC is optimized for UAV-based VoWiFi-5G networks, whereas U-CAC is designed for corporate VoIP infrastructures. Due to the differences in application scenarios, a direct comparison is not entirely meaningful. However, we provide an analysis based on a common evaluation criterion, namely the call success rate. The results indicate that our mechanism maintained a higher success rate even with over 200 users. Furthermore, both mechanisms [26,27] remain at the academic research stage and have not yet been deployed in real-world environments. In contrast, our mechanism has been implemented in practical settings, demonstrating its feasibility.

- (2)

- Latency and Computational cost

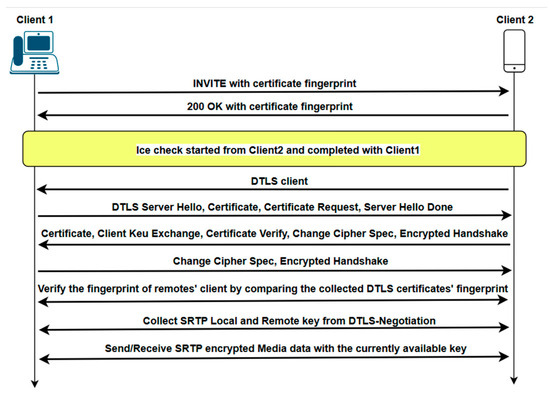

We used DTLS-SRTP as the comparative benchmark to explain the theoretical latency and computational overhead, as practical results vary in real-world scenarios. As you can see in the following flowchart (Figure 9), DTLS-SRTP requires an additional process, which involves a complete TLS protocol to negotiate the cipher suite. Additionally, after receiving certificates, clients must validate them by querying a Certificate Authority (CA). These signaling messages introduce greater overhead compared to the proposed mechanism. In the proposed mechanism, the protocol adds only two additional signal messages (see Figure 5), which can be considered equivalent to the certificate signal message in the TLS protocol. Therefore, the additional overhead introduced by this component is considered to be negligible. To generalize this concept into a mathematical formulation, latency is defined as follows:

where n denotes the total number of signal messages, and τi represents the transmission time of the i-th signal message.

According to [32], prior research has shown that the primary overhead incurred during SSL processing occurs in the session negotiation phase. Approximately 70% of the total processing time of an HTTPS transaction is attributed to SSL processing. For simplification, assuming each τi is 20 ms, the total overhead amounts to 140 ms when considering the following flowchart, which includes seven additional signal messages. Compared to DTLS-SRTP, the proposed mechanism introduces only two additional signal messages, resulting in an increased latency of 40 ms, as calculated using Equation (1) under the same assumption.

Figure 9.

DTLS-SRTP flowchart. For details, refer to [33].

According to [26], the proposed mechanism, which utilizes ECMQV with the Secp521r1 elliptic curve, incurs a computational cost of approximately 0.9875 s to complete the key agreement process. In contrast, DTLS-SRTP is assumed to generate a key using ECDH, requiring approximately 0.806 s. However, DTLS-SRTP incurs additional computational overhead for certificate validation, cipher suite negotiation, and other related operations. Consequently, the proposed mechanism demonstrates greater efficiency.

6. Conclusions

In order to solve the issue of not being able to reach the relevant business personnel by phone while other personnel are available to answer the call, this study presents a practical VoIP service that improves call availability by utilizing reference phone numbers. The system can be built on the traditional SIP VoIP framework. By incorporating the proposed algorithms into existing servers and terminals, upgrading services can be seamlessly integrated. We also analyzed the performance of the reference phone number mechanism through actual deployment, and the mechanism showed satisfactory results, proving its practicality. As future work, research will be conducted on transferring calls from landline numbers to mobile numbers while implementing the corresponding key exchange mechanisms to ensure call security.

Funding

There is no funding for this research.

Data Availability Statement

All research data are included within the content of the research.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the support provided to all users of this system.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- ITU-T. Packet-Based Multimedia Communications Systems; ITU-T Recommendation H.323; International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ITU-T. Gateway Control Protocol; ITU-T Recommendation H.248; International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, J.; Schulzrinne, H.; Camarillo, G.; Johnston, A.; Peterson, J.; Sparks, R.; Handley, M.; Schooler, E. SIP: Session Initiation Protocol; RFC 3261; Internet Engineering Task Force: Fremont, California, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.; Nahum, E.; Schulzrinne, H.; Wright, C. The Impact of TLS on SIP Server Performance. In Proceedings of the Principles, Systems and Applications of IP Telecommunications (IPTComm’10), New York, NY, USA, 2–3 August 2010; pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zourzouvillys, T.; Rescorla, E. An Introduction to Standards-Based VoIP: SIP, RTP, and Friends. IEEE Internet Comput. 2010, 14, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivest, R. The MD5 Message-Digest Algorithm; RFC 1321; Internet Engineering Task Force: Fremont, California, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schulzrinne, H.; Casner, S.; Frederick, R.; Jacobson, V. RTP: A Transport Protocol for Real-Time Applications; RFC 3550; Internet Engineering Task Force: Bangkok, Thailand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S. Real-Time Transport Protocol (RTP). In Multicasting on the Internet and Its Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Liping, Z.; Shanyu, T.; Shaohui, Z. An Energy Efficient Authenticated Key Agreement Protocol for SIP-Based Green VoIP Networks. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2016, 59, 126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Azrour, M.; Ouanan, M.; Farhaoui, Y. A New Efficient SIP Authentication and Key Agreement Protocol Based on Chaotic Maps and Using Smart Card. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computing and Wireless Communication Systems (ICCWCS’17), New York, NY, USA, 14–16 November 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, S.A.; Naqvi, H.; Sher, M.; Farash, M.S.; Hassan, M.U. An Improved and Provably Secure Privacy-Preserving Authentication Protocol for SIP. Peer-Peer Netw. Appl. 2017, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikooghadam, M.; Jahantigh, R.; Arshad, H. A Lightweight Authentication and Key Agreement Protocol Preserving User Anonymity. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 13401–13423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, M.; Abadi, M.; Needham, R. A Logic of Authentication. ACM Trans. Comput. Syst. 1990, 8, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanbakhsh, N.; Mohammadi, M.; Nikooghadam, M. Perfect Forward Secrecy in VoIP Networks through Designing a Lightweight and Secure Authenticated Communication Scheme. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 11129–11153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffie, W.; Van Oorschot, P.C.; Wiener, M.J. Authentication and Authenticated Key Exchanges. Des. Codes Cryptogr. 1992, 2, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armando, A.; Basin, D.; Boichut, Y.; Chevalier, Y.; Compagna, L.; Cuéllar, J.; Drielsma, P.H.; Héam, P.C.; Kouchnarenko, O.; Mantovani, J. The AVISPA Tool for the Automated Validation of Internet Security Protocols and Applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Aided Verification, Edinburgh, UK, 6–10 July 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Nikooghadam, M.; Amintoosi, H. Perfect Forward Secrecy via an ECC-Based Authentication Scheme for SIP in VoIP. J. Supercomput. 2020, 76, 3086–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremers, C. Scyther, Semantics and Verification of Security Protocols. Ph.D. Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Ma, M. A Provably Secure Anonymous Mutual Authentication Scheme with Key Agreement for SIP Using ECC. Peer-Peer Netw. Appl. 2018, 11, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Hassan, M.; Chaudhry, S.; Irshad, A. An Improved SIP Authenticated Key Agreement Based on Dongqing et al. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2020, 110, 2087–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vocal Technologies Ltd. Secure SIP. Available online: https://vocal.com/sip/secure-sip/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Roach, A.B. Security Mechanism Agreement for the Session Initiation Protocol (SIP); RFC 3329; Internet Engineering Task Force: Bangkok, Thailand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- SIPTRUNK. A Brief Guide to SIP Security. Available online: https://www.siptrunk.com/2019/08/a-brief-guide-to-sip-security/ (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Carrara, T.T.; Housley, R.; Kalt, C.J.; Lazzaro, J.C.R. The Secure Real-time Transport Protocol (SRTP); RFC 3711; Internet Engineering Task Force: Bangkok, Thailand, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, W.-B.; Leu, J.-S. Implementing a Secure VoIP Communication over SIP-Based Networks. Wirel. Netw. 2018, 24, 2915–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, V.; Estepa, R.; Estepa, A.; Madinabeitia, G. Unified Call Admission Control in Corporate Domains. Comput. Commun. 2020, 150, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, V.; Estepa, R.; Estepa, A. O-CAC: A New Approach to Call Admission Control for VoIP in 5G/WiFi AV-Based Relay Networks. Comput. Commun. 2023, 197, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Kwon, S. Joint Call Admission Control and Load-Balancing in Ultra-Dense Cellular Networks: A Proactive Approach. Wirel. Netw. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, I.; Seroussi, G.; Smart, N. Advances in Elliptic Curve Cryptography; London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; Volume 317. [Google Scholar]

- HTC. Inserting SIM and SD—HTC U20 5G. Available online: https://www.htc.com/tw/support/htc-u20-5g/howto/inserting-sim-and-sd.html (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Yeastar. VoIP Gateways. Available online: https://www.yeastar.com/voip-gateways/ (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Kulin, M.; Kazaz, T.; Mrdovic, S. SIP Server Security with TLS: Relative Performance Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2012 IX International Symposium on Telecommunications (BIHTEL), Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 25–27 October 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R. WebRTC: Overview and Analysis of WebRTC Security. MatrixSust Blog. 2014. Available online: https://matrixsust.blogspot.com/2014/05/webrtc-overview-and-analysis-of-webrtc.html (accessed on 8 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).