Abstract

Industrial predictive maintenance at the edge faces persistent challenges such as extreme class imbalance, limited labeled failure data, and the need for efficient yet scalable AI models. This paper proposes a transfer learning-based edge AI framework that addresses these challenges through a signal-to-image transformation and fine-tuning of deep residual networks (ResNet). One-dimensional sensor signals are converted into two-dimensional RGB images, enabling the use of powerful convolutional architectures originally trained on large-scale datasets. The approach emulates an edge–cloud synergy, where knowledge distilled from large pre-trained models is efficiently adapted and executed on resource-constrained edge environments. Trained on less than 5% of the original dataset, the model achieves a negative predictive value of 96.53%, significantly reducing classification cost and outperforming both conventional deep learning and traditional machine learning methods. The results demonstrate that transfer learning-driven edge intelligence offers a cost-effective, scalable, and generalizable solution for predictive maintenance and industrial automation under data scarcity.

1. Introduction

Failures in complex industrial systems can lead to substantial financial losses, extended operational downtime, and critical safety risks. To mitigate these risks, predictive maintenance (PdM) has therefore emerged as a proactive strategy that anticipates potential faults and schedules interventions before failures occur [1,2]. While traditional PdM approaches typically rely on machine learning models trained with large volumes of labeled data, they assume the availability of sufficient and balanced samples from both healthy and faulty system states [3,4]. However, in real-world industrial environments, failure events are inherently rare, expensive to replicate, and difficult to label—highly imbalanced datasets. This imbalance significantly undermines the generalization performance of standard classifiers, often leading to high false-negative rates, particularly when detecting rare but critical failures [5,6].

Moreover, acquiring a substantial amount of labeled failure data is especially challenging in safety-critical or high-reliability systems, where faults occur rarely and only over long operational lifespans [7,8]. Even when massive volumes of sensor data are collected, the vast majority of observations represent normal operating conditions, offering limited insight into the actual failure dynamics. In addition, conventional diagnostic pipelines often rely on manual feature engineering and extensive model tuning, which are not only time-consuming but also heavily reliant on domain expertise [9,10,11].

Machine maintenance can be effectively planned and potential failures can be predicted by leveraging data collected from internal and/or external sensors, which provide continuous insight into the system’s operational health [7,12]. In a typical predictive maintenance pipeline, raw sensor data is first recorded, then preprocessed through noise filtering and, when necessary, segmented into windows. Subsequently, feature extraction is performed to derive informative representations from the preprocessed signals. Finally, an appropriate classification or regression model is trained to learn the mapping between these features and their corresponding labels [9,13].

Recent progress in deep learning (DL) has transformed many aspects of predictive maintenance (PdM). Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), in particular, have become prominent because they can automatically extract multi-level feature representations from raw sensor inputs [14]. Despite their power, CNN-based models typically require large, well-balanced labeled datasets to achieve robust performance. When trained on limited or imbalanced data, they are highly susceptible to overfitting, which undermines their generalization ability and, consequently, limits their practical deployment in real-world industrial settings [15,16].

To address the limitations of conventional DL in data-scarce settings, transfer learning has emerged as a powerful and practical alternative. Within this approach, deep networks pre-trained on extensive datasets—such as ResNet [17,18] models originally trained on large-scale image collections like ImageNet [19]—are adapted to new tasks with relatively small sets of labeled samples. These models retain generalizable low-level features (e.g., edges, textures) from their source domain, which can be effectively reused in new tasks. By leveraging this knowledge, transfer learning not only reduces the need for extensive labeled data but also significantly enhances model performance in low-resource and highly imbalanced environments [20,21].

Many recent studies have used supervised or semi-supervised models for failure detection, but they usually require large and balanced datasets. In real industrial systems, failure samples are rare, so these methods often perform weakly. Most works depend on extracted features by the general approach or complex ensembles, and only a few explore the use of pre-trained convolutional networks to learn from limited data. In addition, many models are evaluated without cost-aware metrics, even though missing a failure is far more critical than a false alarm. Thus, there is a clear need for a scalable and data-efficient solution. To address this need, an image-based transfer learning framework designed for highly imbalanced failure prediction and suitable for edge deployment has been proposed in this study.

In this study, we propose an efficient failure detection framework that leverages transfer learning with a ResNet-18 architecture. To enable compatibility with image-based CNN models, one-dimensional sensor signals are first transformed into two-dimensional representations using a signal-to-image conversion process. The resulting images are then utilized to fine-tune a pre-trained ResNet-18 for fault classification.

We evaluate our method on the Scania Trucks Air Pressure System (APS) dataset [22,23], a publicly available benchmark that presents an extreme class imbalance scenario. The training set comprises 60,000 samples, with only 1000 (1.66%) belonging to the positive class (Failure Type 2, FT2) and the remaining 59,000 to the negative class (Failure Type 1, FT1), reflecting a highly imbalanced distribution.

This dataset exhibits extreme class imbalance, with only 1.66% of the training samples corresponding to failure events. This imbalance presents a realistic and challenging testbed for assessing the effectiveness of transfer learning in failure prediction tasks.

To further align with emerging trends [24,25] in edge intelligence and edge–cloud cooperation, this work contributes to the broader discourse on scalable AI for industrial automation. The proposed transfer learning-based framework offers a lightweight yet powerful alternative to conventional deep learning, enabling reliable inference under computational and data constraints typical of edge environments. By minimizing training requirements while maintaining high predictive accuracy, our approach demonstrates how edge-deployable AI models can support real-time predictive maintenance in smart manufacturing and industrial IoT systems. While we used a standard laptop for testing, the low parameter count and small memory footprint of the model indicate that it can be implemented on typical edge devices such as industrial micro-computers or ARM-based platforms.

The main contribution of the paper is three-fold.

- We present a novel signal-to-image transformation pipeline that enables the use of one-dimensional sensor signals as RGB image inputs for convolutional neural networks (CNNs).

- We leverage a pre-trained ResNet-18 architecture to transfer low-level features (e.g., edges, color gradients, textures), improving failure classification performance in the presence of highly imbalanced data.

- We demonstrate that even when fine-tuned on a restricted subset of the training data, the proposed model achieves strong classification performance, highlighting its effectiveness in low-resource industrial settings.

The remaining sections of the paper are structured as follows: in Section 2, we have summarized the literature. In Section 3, we have described the dataset, metrics, the background methods including CNN and ResNet18 and the proposed method. In Section 4, experimental results are presented. In Section 5, the paper is concluded.

2. Literature Review

In recent years, the application of machine learning (ML) and DL methods for failure detection has gained significant momentum, particularly in the context of industrial applications. Accurate and timely failure identification is essential for minimizing unplanned downtime, reducing maintenance costs, and maintaining overall system reliability. However, one of the most persistent challenges in this domain is the imbalanced nature of failure datasets, where positive (faulty) instances are significantly outnumbered by normal ones. This section reviews key contributions to the field and highlights research gaps that motivate our proposed approach.

Freitas et al. (2023) proposed a three-stage data-driven framework for PdM in commercial vehicle turbochargers, emphasizing the importance of data preparation and domain understanding [26]. Although their work laid a solid foundation for model development, it stopped short of implementing ML algorithms for actual failure detection, leaving a gap in predictive performance evaluation using real-world datasets. In addition, the framework does not provide guidance on how the extracted features should be integrated into scalable, cost-efficient models, which limits its practical use in industrial deployment scenarios.

To address the issues of high dimensionality and imbalance, Mao and Cheng (2023) introduced a Modified Mahalanobis–Taguchi System (MMTS) [27]. Their approach combined ReliefF feature ranking and particle swarm optimization (PSO) to construct an effective classification model tailored to detect air pressure system (APS) faults in trucks. The MMTS demonstrated superior accuracy over conventional models, particularly in imbalanced scenarios, validating the efficacy of hybrid optimization for robust classification. However, the method still relies heavily on features by defined experts and assumes that the feature selection process can consistently capture rare failure patterns, which may limit its generalization in unexpected industrial conditions.

From a model interpretability perspective, Farea et al. (2025) developed an Explainable Boosting Machine (EBM) framework to detect APS failures using operational driving data from heavy-duty vehicles [28]. Their model obtained an accuracy of 91.4% and an F1-score of 0.80 while offering interpretable outputs that align with domain expert knowledge. This work underscores the growing importance of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in high-risk applications such as predictive maintenance. Thus, the reported performance still depends on the availability of representative failure examples, and the model may disturbance to generalize when only a very limited number of faulty samples are available in real-world.

Complementary to this, Mumcuoglu et al. (2024) proposed a semi-supervised anomaly detection architecture that leverages Long Short-Term Memory Autoencoders (LSTM-AE) and Transformer-based models (TranAD) [29]. By integrating Human Expert Analysis (HEA) with deep learning, their hybrid model achieved a 92.8% accuracy and an F1-score of 0.82, showing clear benefits in reducing false alarms and enhancing trustworthiness in imbalanced settings. At the same time, the reliance on expert feedback limits scalability and may not be feasible for continuous deployment.

Beyond model design, Shyalika et al. (2024) investigated the role of data enrichment techniques—such as augmentation, sampling, and imputation—in enhancing the performance of rare event prediction in manufacturing [30]. By applying these strategies across five industrial datasets and evaluating 15 learning models, their framework demonstrated that data enrichment can boost F1-scores by up to 48%, emphasizing the need for robust preprocessing in highly imbalanced environments. However, the benefit of these methods largely depends on how realistically the synthetic data represents actual failures, which is not always easy to ensure.

While these studies represent significant progress in failure detection, several gaps remain. Most approaches rely on either supervised or semi-supervised architectures and lack generalization capabilities across different domains or failure types. Few studies explore the potential of transfer learning for cross-domain feature adaptation in imbalanced settings. Moreover, although explainability has gained traction, many high-performing models remain opaque or overly complex for real-time industrial deployment.

In response to these challenges, our proposed method integrates transfer learning with uncertainty-aware classification and a re-routing mechanism for low-confidence predictions. This design not only improves detection performance under class imbalance but also mimics human-like decision reassessment, contributing to more interpretable and reliable fault diagnosis in critical systems.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, we present the methodological framework developed to address the challenges posed by highly imbalanced and data-constrained fault detection scenarios. The proposed approach combines transfer learning with a cost-sensitive classification strategy, enabling reliable failure prediction even with severely limited failure samples. To this end, one-dimensional sensor signals are transformed into two-dimensional color-encoded representations, making them compatible with convolutional neural networks. A pre-trained ResNet-18 architecture is subsequently fine-tuned on the converted data to capture relevant failure patterns while minimizing the risk of overfitting. The methodology is organized into five main components: (1) dataset description and preprocessing, (2) evaluation metrics tailored for imbalanced classification, (3) baseline CNN model, (4) ResNet-based transfer learning architecture, and (5) the proposed classification framework. Each component is detailed in the following subsections.

3.1. Dataset

The dataset employed in this study is the APS Failure at Scania Trucks dataset, which is openly accessible through the UCI Machine Learning Repository [22,23]. It contains sensor measurements obtained from heavy-duty Scania trucks operating under real-world conditions.

The focus of the dataset is the Air Pressure System (APS), a subsystem responsible for supplying compressed air to essential vehicle functions such as braking and gear shifting.

The dataset provides labeled examples for two classes based on expert evaluation. The positive class corresponds to failures occurring within a specific APS component, whereas the negative class refers to issues arising in other truck components unrelated to the APS. This dataset is a refined subset of a larger data collection, selected to ensure high relevance and reliability for predictive maintenance research.

The training set comprises 60,000 samples, with only 1000 (1.66%) belonging to the positive class (Failure Type 2, FT2), and the remaining 59,000 to the negative class (Failure Type 1, FT1), reflecting a highly imbalanced class distribution. The testing set contains 16,000 samples, similarly distributed. Each sample is described by 171 numerical features obtained from various sensors. However, there is a lot of missing data in the dataset. Six attributes with a large number of deficiencies were discarded. Other missing data was completed with the average of the numbers in the relevant feature.

3.2. Metrics

Evaluating classifier performance on imbalanced datasets requires more than simple accuracy, which can be misleading when the majority class dominates. Instead, a range of performance metrics tailored for class imbalance is adopted in this study. Let the confusion matrix be defined as the following table.

The following metrics have been computed from Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptions of a confusion matrix.

3.2.1. Precision (P)

Measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples among all predicted positives:

High precision indicates a low false alarm rate, which is essential in cost-sensitive industrial systems.

3.2.2. Recall (R)

Also termed sensitivity or the true positive rate, this measure reflects the model’s capability to correctly recognize genuine failures:

In predictive maintenance, recall is critical because missing a failure (false negative) could result in significant downtime or safety risk.

3.2.3. Specificity (S)

Also referred to as the true negative rate, specificity evaluates how well the model avoids false alarms:

This is especially important for avoiding unnecessary maintenance in healthy vehicles.

3.2.4. F1-Score (F1)

F1-score is computed as the harmonic mean between precision and recall:

This metric balances false positives and false negatives, making it suitable for imbalanced classification problems.

3.2.5. Accuracy (Ac)

In classification studies, accuracy is a standard metric that reflects how many instances were correctly labeled out of all predictions made. Mathematically, it is defined as

3.2.6. Negative Predictive Value (NPV)

Reflects the model’s ability to assign the negative label accurately among all predicted negatives:

A high NPV suggests reliability in identifying healthy (non-failing) vehicles.

3.2.7. Cost-Sensitive Metric

In real-world predictive maintenance applications, the costs associated with misclassification are inherently asymmetric. In particular, misclassifying a failed truck (FT2) as healthy (FT1) can result in severe safety risks, unexpected breakdowns, and significant financial losses. In contrast, misclassifying a healthy truck as failed leads primarily to unnecessary maintenance costs and minor operational inefficiencies. To better reflect this asymmetry in evaluation, we define a cost-sensitive loss metric as follows:

Here, the advised values [31] of the constant parameters by the literature have been utilized. represents the cost of a false positive (i.e., misclassifying a healthy truck as faulty), = 500 denotes the cost of a false negative (i.e., failing to detect a true fault). This sharp cost contrast (≫) emphasizes the critical importance of minimizing false negatives in safety-critical systems such as industrial vehicle fleets.

This asymmetric weighting scheme places greater emphasis on false negatives, aligning the evaluation metric with the real-world consequences of undetected failures. By assigning a significantly higher penalty to missed fault predictions, the cost metric offers a more realistic and deployment-oriented assessment of the model’s practical utility, especially in safety-critical and cost-sensitive industrial environment.

3.3. Convolutional Neural Network

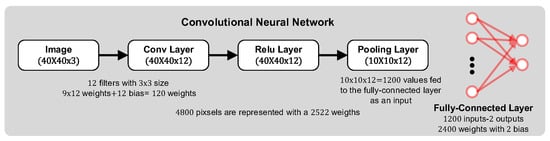

CNNs have emerged as a cornerstone in image-based learning tasks due to their ability to automatically extract spatial hierarchies of features through localized receptive fields and shared parameters [32]. These architectures are particularly advantageous when working with image data, as they reduce the number of trainable weights relative to fully connected networks, thereby mitigating overfitting and enhancing generalization performance [33]. A structure of CNN is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A simple convolutional neural network.

In the context of this study, a standard CNN model is employed as a baseline for performance comparison. Given that the original dataset comprises one-dimensional sensor signals, these signals are transformed into two-dimensional color images to enable spatial pattern learning within the CNN framework. This transformation allows the model to utilize convolutional operations to capture representative fault features.

A typical CNN architecture is composed of the following sequential components:

Convolutional Layer:

The convolutional layer performs a set of learnable filters across the spatial dimensions of the input image. For a given input , filter and bias the convolution operation is defined as:

where denotes the convolution operator and is the activation function, typically ReLU. These filters are responsible for detecting local patterns such as edges, corners, and textures [34].

Activation Layer (ReLU):

ReLU is used as the activation function to provide the model with non-linear transformation capability:

ReLU facilitates faster convergence during training and alleviates the vanishing gradient problem commonly encountered in deep networks [34].

Pooling Layer:

Pooling operations are employed to reduce the spatial resolution of feature maps, effectively lowering computational complexity and providing a form of translation invariance. Max pooling, the most common form, is defined as

where denotes the receptive region associated with position [34].

Fully Connected Layer:

Following the convolutional and pooling stages, the high-level feature maps are flattened and passed through one or more fully connected layers. These layers integrate the spatially distributed features and facilitate the final classification via a softmax or sigmoid activation function, depending on the nature of the task [34].

3.4. Residual Network (ResNet)

Conventional CNNs have demonstrated remarkable success in visual recognition tasks; however, their effectiveness tends to diminish in scenarios involving small-scale or imbalanced datasets. Moreover, as network depth increases, issues such as vanishing gradients and optimization instability emerge, often resulting in performance degradation. To address these limitations, Residual Networks (ResNets) [17,18] introduce a novel architectural paradigm that facilitates the training of very deep models through the use of identity shortcut connections, which bypass one or more layers. A residual block is formally expressed as

where is the input to the block, denotes the residual mapping to be learned (typically a series of convolution, batch normalization, and activation operations), and is the output. This structure enables the training of networks with significantly increased depth while maintaining stable convergence.

In this study, we adopt ResNet-18, a relatively lightweight architecture consisting of 18 layers, to strike a balance between computational efficiency and classification performance. The rationale for this choice is twofold:

- Computational Feasibility: Compared to deeper alternatives such as ResNet-50 or ResNet-101, ResNet-18 requires significantly fewer parameters and operations, making it more practical for real-time deployment on standard hardware platforms [35].

- Robust Feature Extraction: ResNet-18 is pre-trained on the large-scale ImageNet dataset, which contains over 1 million annotated images across 1000 categories. The early convolutional layers of the network extract domain-agnostic features—such as edges, color gradients, and textures—that are broadly applicable to diverse data modalities once appropriately formatted [35].

To adapt the network for failure classification, the one-dimensional sensor signals are first transformed into two-dimensional color-encoded images. These images are then processed using the pre-trained ResNet-18 model. During this adaptation phase, the core convolutional layers are retained to preserve general visual feature representations, while the fully connected classification layers are fine-tuned on the target dataset to specialize in distinguishing between different failure types.

Experimental results indicate that ResNet-18 performs robustly even with a limited number of training samples and under severe class imbalance. This capability makes it particularly suitable for industrial scenarios where failure events are rare and data collection is constrained. In the subsequent section, the integration of ResNet-18 into the proposed classification framework is described in detail.

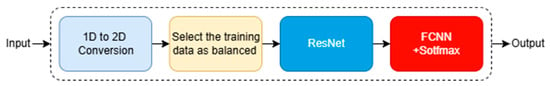

3.5. Proposed Method

In this study, we propose a transfer learning-based classification framework designed to address the challenges associated with failure detection in industrial systems, particularly those characterized by extreme class imbalance and limited labeled fault data. The proposed method integrates signal-to-image transformation, pre-trained deep feature extraction, and cost-aware training to address the primary constraints that hinder the performance of conventional machine learning and deep learning models in predictive maintenance scenarios. The general block diagram of the proposed method has been presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The general block diagram of the proposed method.

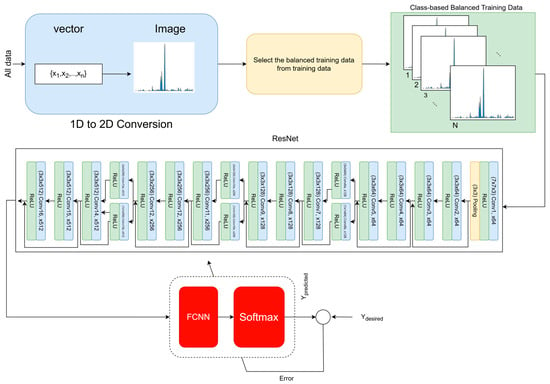

The overall pipeline is illustrated in Figure 3 and comprises the following stages:

Figure 3.

Proposed Framework.

- Signal-to-Image Conversion

Given that the original dataset consists of one-dimensional sensor readings, a critical pre-processing step involves transforming these time-series signals into two-dimensional color-encoded image representations. This conversion facilitates compatibility with convolutional architectures, which are inherently optimized for spatial pattern recognition. The transformation also enables the model to exploit the structural regularities in signal morphology through two-dimensional convolutions. Since the dataset consists of one-dimensional sensor measurements, each feature vector is transformed into a two-dimensional RGB image so that it can be processed by ResNet. The full procedure is as follows: the 1D vector is first normalized to , then reshaped into a compact 2D grid that preserves the original feature ordering. This grid is converted to a three-channel representation through a fixed colormap, producing an initial pseudo-image. Finally, the pseudo-image is resized to to match the input requirements of ResNet while keeping the relative spatial arrangement of features intact. This transformation enables the network to learn local co-activation patterns across neighboring features using 2D convolutions.

- 2.

- Feature Representation using ResNet-18

Following the image conversion, the resulting representations are processed through the ResNet-18. The initial convolutional layers, responsible for learning generic visual primitives such as edges, contours, and textures, are preserved, whereas the final fully connected classification layers are reinitialized and fine-tuned on the target dataset. This strategy not only reduces the number of parameters that need to be trained from scratch but also significantly enhances generalization in data-constrained environments.

- 3.

- Class-Rebalanced Training Approach

To counteract the adverse effects of class imbalance, the training process employs a rebalanced data sampling strategy in which an equal number of failure (FT2) and non-failure (FT1) samples are randomly selected. Experiments are conducted under varying sample approaches (e.g., 2000, 40, 20, 10 samples per class) to evaluate the stability and scalability of the proposed method in few-shot learning settings.

- 4.

- Cost-Sensitive Optimization

Recognizing the asymmetric risk associated with different types of misclassification, particularly the high operational cost of false negatives in safety-critical systems, a domain-specific cost metric is employed.

4. Results and Discussion

To validate the performance of the proposed failure detection framework, we conducted a series of experiments using the Air Pressure System (APS) dataset provided by Scania. The dataset consists of 60,000 training samples and 16,000 testing samples, each with 171 sensor-based features. Six features with substantial missing values were removed. The remaining missing entries were imputed using feature-wise mean values to maintain data integrity without introducing synthetic noise.

All signals were preprocessed and transformed into RGB image representations suitable for CNN input. The training datasets were constructed in multiple configurations to evaluate performance under varying sample constraints. Specifically, balanced training subsets with sizes of 2000, 40, 20, and 10 samples (equal number of FT1 and FT2) were randomly selected from the full dataset for few-shot learning scenarios.

The deep learning models were implemented in Python 3.10 using PyTorch 2.1.0 and trained on a standard laptop equipped with an Intel Core i7 processor (2.2 GHz) and 8 GB RAM. No GPU acceleration was utilized to emphasize the framework’s suitability for low-resource environments. The ResNet-18 architecture was selected due to its optimal trade-off between representational capacity and computational efficiency. A three-layer conventional CNN was used as a baseline for comparison.

In this work, no explicit cost-sensitive loss function is applied during training. All models, including ResNet, are optimized using standard cross-entropy loss. Cost sensitivity is introduced exclusively at the evaluation stage through the APS cost metric, where false negatives and false positives incur penalties of 500 and 10 units, respectively. This design aligns with the original APS challenge, in which the cost metric is used to assess operational risk rather than to modify the training objective.

All models were trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 16, and standard cross-entropy loss. Training was performed for up to 100 epochs, with early stopping based on validation loss to prevent overfitting. For ResNet-18 shown in Figure 3, the weights were initialized from ImageNet pretraining, and the final fully connected layer was replaced with a 2-unit classification head. A mild weight decay (0.0001) was applied to stabilize optimization, and the learning rate was kept constant throughout training for simplicity. These settings represent a standard and lightweight configuration commonly used in transfer-learning scenarios and were sufficient to achieve stable convergence on the APS dataset.

Performance was evaluated using both standard metrics (Precision, Recall, Specificity, F1-score, Ac, NPV) and a cost-sensitive metric designed to penalize FT2 misclassifications more heavily, reflecting the practical impact of rare failure events in real-world predictive maintenance settings.

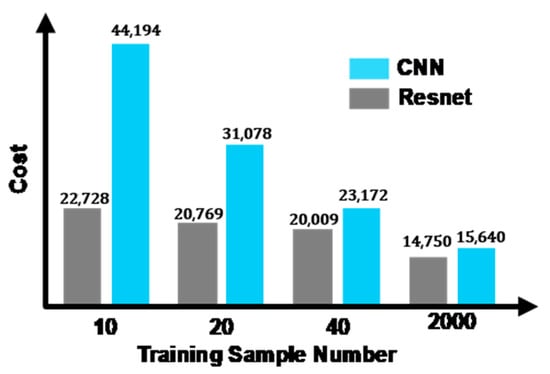

The proposed framework’s performance is investigated in two stages. We have compared ResNet-based proposed framework and a conventional CNN with three layers in the first stage. Obtained results are presented in Table 2. In addition, the comparisons of the costs are illustrated in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Comparison results in ResNet and CNN.

Figure 4.

Cost with respect to training sample number for ResNet and CNN.

Table 2 demonstrates that the proposed ResNet-based framework consistently outperforms the conventional CNN in terms of cost-efficiency and generalization across varying training sample sizes. Although CNN achieves slightly higher P, F1, and S in scenarios with extremely limited data (e.g., TSN = 10), it suffers from a notable decline in NPV and incurs significantly higher cost values. For instance, when only 10 training samples are used, the cost associated with the CNN reaches 44,194, whereas the ResNet model maintains a much lower cost of 22,728, indicating its superior robustness in cost-sensitive classification. This suggests that the CNN tends to overfit the minority class at the expense of false negatives in the majority class, which are heavily penalized by the domain-specific cost function. Furthermore, the ResNet model exhibits greater stability across different sample sizes, preserving a high level of recall (above 99.8%) and balanced NPV, even with only a handful of training examples. These findings validate the effectiveness of transfer learning in handling highly imbalanced datasets with limited failure data and underline the importance of using cost-aware metrics in evaluating classifier performance for predictive maintenance applications.

A close examination of the costs in Figure 4 across varying TSN reveals a critical insight into the comparative robustness of the evaluated models under data-scarce conditions. As expected, reducing the TSN leads to a substantial increase in classification cost, driven primarily by the heightened likelihood of misclassifying minority class instances (FT2), which are associated with a significantly higher penalty in the defined cost function. However, the rate and magnitude of cost escalation differ markedly between the two models. The CNN model exhibits a sharp and disproportionate increase in cost as TSN decreases from 15,640 at 2000 samples to 44,194 at 10 samples indicating a strong susceptibility to overfitting and reduced generalization capacity in low-data regimes. Conversely, the proposed ResNet-based approach demonstrates a more controlled and gradual increase in cost, ranging from 14,750 to 22,728 across the same TSN spectrum. This performance stability under severe data constraints underscores the effectiveness of transfer learning in retaining discriminatory power while minimizing high-cost misclassifications.

These results validate the proposed model’s suitability for real-world predictive maintenance applications, where failure data is inherently rare and the cost of incorrect predictions particularly false negative scan be prohibitively high. The consistent cost advantage observed for the ResNet model further highlights its potential as a resource-efficient and risk-aware solution in imbalanced and cost-sensitive classification environments.

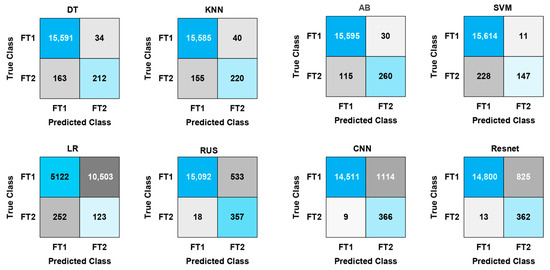

In the second stage, we have measured the performance of some well-known classifiers, including, k-nearest neighbors algorithm (KNN), support vector machine (SVM), decision tree (DT), logistic regression (LR), boost tree ensemble (RUS) and, adaboost (AB) to compare them with Resnet.

Table 3 presents a comparative analysis between the proposed ResNet-based model and a suite of conventional machine learning algorithms. All conventional methods were trained on the full dataset comprising 60,000 samples, whereas the ResNet and CNN models were trained using only 2000 balanced samples.

Table 3.

Comparison results of conventional machine learning methods with ResNet.

Although traditional methods such as DT, KNN, SVM, and AB achieve high values in conventional metrics such as Ac, P, and recall R, their associated cost values remain significantly higher than those of the ResNet model trained with only one-thirtieth of the data. For instance, SVM reaches a high Ac of 98.51% and an F1 of 99.24%, yet it incurs a cost of 114,110 due to a substantial number of high-penalty misclassifications involving the minority class. A similar pattern is observed in AB and KNN, with costs exceeding 57,000 and 77,000, respectively, despite their favorable metric profiles. This disconnect highlights the limitations of standard performance indicators in imbalanced, cost-sensitive domains.

LR performs the worst overall, exhibiting both the lowest S (1.16%) and Ac (32.78%), which translates into the highest observed cost (231,030). In contrast, RUSBoost, an ensemble model explicitly designed to address class imbalance, achieves the lowest cost (14,330) among traditional classifiers, closely followed by the proposed ResNet (14,750) and CNN (15,640), both trained on much smaller datasets.

In imbalanced classification problems—such as failure detection in predictive maintenance scenarios—the NPV represents a pivotal performance indicator, as it quantifies the proportion of true negatives among all negative predictions. High NPV is particularly desirable in contexts where failing to identify a faulty instance (i.e., a false negative) may lead to severe operational, financial, or safety-related consequences. Therefore, the ability of a classifier to confidently and accurately identify negative cases is as important as detecting the minority class.

As shown in Table 3, considerable discrepancies are observed in NPV across the evaluated models. While several conventional classifiers achieve near-optimal values in terms of precision, recall, and accuracy such as SVM (Ac: 98.51%, F1: 99.24%) and AdaBoost (Ac: 99.09%, F1: 99.54%) their NPV values are markedly lower, recorded at 39.20 and 69.33, respectively. This performance inconsistency reveals a latent vulnerability: these models are prone to misclassifying faulty instances as healthy, which could be detrimental in real-world deployments.

By contrast, the proposed ResNet-based framework achieves an NPV of 96.53%, approaching the highest score attained by CNN (97.60%), despite being trained on significantly fewer samples (2000 versus 60,000). Notably, ResNet achieves this high NPV without incurring a substantial cost, demonstrating a more favorable balance between reliability and economic efficiency. In comparison, CNN although slightly outperforming ResNet in NPV yields a higher cost, suggesting a trade-off between overly aggressive recall and increased misclassification penalties. Moreover, while RUSBoost, the best-performing classical method in terms of cost, yields a comparable NPV of 95.20, it does so using the entire dataset. ResNet, in contrast, maintains competitive performance under limited data availability, underscoring the effectiveness of transfer learning in enhancing generalization from small-scale training sets.

These findings establish NPV as a critical yet often underemphasized metric in the evaluation of classifiers for high-risk, cost-sensitive applications. The ability of the proposed framework to simultaneously sustain high NPV and minimize misclassification cost positions it as a promising and practically viable approach for deployment in industrial fault diagnosis systems. Hence, these findings underline the cost-efficiency and data-efficiency of the ResNet-based framework. Despite operating under limited data constraints, ResNet manages to outperform or closely match models trained on full datasets, especially in cost-critical failure detection tasks. The results validate the integration of transfer learning as a viable strategy for enhancing generalization while minimizing costly misclassifications in real-world industrial applications.

The confusion matrices are shown in Figure 5 give us to visualize the performance of all algorithms. RUS is a bit better than the proposed framework, the reason why RUS has utilized all data samples. We also show that P, R, S, F1 metrics are not convenient to measure the performance of the classifiers for this problem. For example, KNN is missed 42% FT2; however, its performance is very well regarding P, R, S, and F1 metrics. It should be noted that the classification performance of the ResNet trained with only ten samples is better than all algorithms except RUS.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrices for all methods.

A comparison of the total execution (TE) times shows a clear separation between classical tabular models and deep convolutional architectures. Methods such as DT, KNN, LR, and RUSBoost complete full-dataset training within 6–16 s, demonstrating their low computational overhead on structured data. SVM is noticeably slower but still capable of processing all 60,000 samples in under 90 s. In contrast, CNN-based models require significantly higher computational effort due to the image-based input representation and convolutional operations. Even when trained on a reduced subset of 2000 samples, the CNN and ResNet models exhibit total execution times of 221 and 521 s, respectively. This comparison highlights that while CNNs provide richer feature extraction capabilities, classical models remain substantially more efficient for large-scale tabular data, whereas deep models incur higher runtime costs that must be considered in resource-constrained or edge-oriented deployments.

Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed ResNet-based method against a diverse collection of previously published fault detection models, encompassing both traditional machine learning and modern deep learning approaches. While a majority of these studies report high performance in conventional metrics—such as Ac and F1—they frequently overlook cost-sensitive metrics or NPV, which are particularly vital in high-stakes predictive maintenance applications. Several recent studies—including those by Chen [36], Tanhandiki [37], and Hussain [38]—demonstrate strong classification performance with reported accuracies exceeding 98% and F1-scores above 97%. However, these works lack cost or NPV reporting, which limits their interpretability in contexts where the consequences of false negatives outweigh other classification errors. For instance, Hussain’s GB and AB models achieve accuracies of 98.44% and 97.56%, respectively, but provide no insights into their performance in minimizing undetected failures.

Table 4.

Comparative Performance Analysis of the Proposed Method Against Existing Published Studies.

In contrast, the proposed ResNet-based model demonstrates a more comprehensive performance profile. With an F1-score of 97.25%, accuracy of 94.76%, NPV of 96.53%, and a comparatively low cost of 14,750, it offers a well-balanced solution that addresses not only predictive capability but also operational risk and economic efficiency. This contrasts with alternative models such as the AB variant of the proposed method, which, while achieving higher accuracy (99.09%), results in a significantly higher cost (57,800) and substantially lower NPV (69.33%), highlighting the trade-off between aggressive classification and risk-sensitive performance. Furthermore, among the few published works that report cost explicitly—such as Kafunah’s DLWP-based methods [42]—the proposed ResNet model achieves substantially lower misclassification cost, despite being trained under more constrained data conditions. This reinforces its effectiveness in handling imbalanced, high-risk scenarios without relying on extensive computational or data resources.

To better understand how the proposed representation compares with conventional approaches, a direct 1D CNN baseline was also evaluated using the raw feature vectors. Although this model reached a relatively high accuracy of 97.66% and an NPV of 97.66%, it ultimately failed to identify any positive cases due to the severe 59:1 class imbalance in the APS dataset. As a result, the model produced an F1-score of 0 and a very high misclassification cost of 187,500. This outcome reflects a known issue in the APS dataset, where cost, not F1, is the most reliable evaluation metric, and it illustrates the limitations of relying solely on accuracy-based measures in highly skewed scenarios.

To further interpret the classification outcomes, we briefly examined the misclassified samples. We observed that most errors occur in regions where sample measurements lie close to the decision boundary, making them inherently ambiguous. These instances typically exhibit incomplete or weak patterns rather than clear fault signatures. Such borderline cases explain why a small number of FP and FN predictions remain even after model optimization. Their presence is expected in high-dimensional sensor datasets, and the APS cost metric provides a practical way to account for their impact on real-world decision-making.

The comparative findings underscore the practical advantages of the ResNet-based framework in delivering robust, cost-aware, and risk-sensitive classification performance. By incorporating underutilized but critical metrics such as NPV and misclassification cost, the proposed approach addresses important gaps in the current literature and advances the applicability of deep learning in real-world predictive maintenance systems.

5. Conclusions

This study presents an effective framework for failure classification in highly imbalanced datasets, addressing three major challenges in predictive maintenance: data imbalance, insufficient failure samples, and model selection complexity. By transforming one-dimensional signal features into color images and employing a pre-trained ResNet-18 architecture, the proposed method achieves reliable classification performance even when trained on as few as 10 samples.

Experimental results demonstrate that the framework outperforms conventional CNNs and traditional machine learning models under limited-data scenarios, achieving superior cost efficiency and competitive performance metrics. Unlike most existing methods, which either rely on large labeled datasets or extensive training resources, our approach demonstrates high scalability and practicality, particularly in industrial environments where failure data is rare and expensive to collect.

In addition, although the present study focuses on supervised learning under limited failure data, the results highlight the importance of generalization to unseen domains and zero-fault conditions in real industrial settings. Many real-world PdM systems must operate for long periods without labeled failures, and sensor distributions may change across environments. Recent advances in out-of-distribution learning and zero-fault recognition, such as relation-based feature modeling and synthetic data augmentation demonstrate promising strategies for handling these challenges. Integrating such techniques into our transfer learning framework represents a clear direction for future work and may further improve robustness when failure samples are extremely scarce or unavailable.

By minimizing the need for large-scale data acquisition and preprocessing, the proposed framework offers a cost-effective and data-efficient solution for real-world fault detection applications. These results suggest that transfer learning with ResNet can be a viable and powerful tool for industrial predictive maintenance, opening new pathways for robust and scalable deployment in critical systems. Future work will explore domain adaptation strategies to enhance cross-system generalization and reduce dependency on system-specific data characteristics. Additionally, integrating explainable AI techniques will be considered to improve transparency and support human-in-the-loop decision-making. Finally, expanding the framework to handle multi-class failure scenarios could further increase its applicability in complex industrial systems.

Author Contributions

A.C. and H.B. jointly developed the core concept of the study. A.C. designed the methodology and implemented the software. Validation was performed by A.C. and H.B. A.C. led the formal analysis, while H.B. and A.C. conducted the investigation. J.W. and D.R. provided resources. H.B. oversaw data preparation. D.R. coordinated the technical infrastructure. A.C. and D.R. prepared the initial manuscript draft, with A.C. and H.B. contributing to revisions and editing. A.C. generated the visualizations. J.W. and D.R. supervised the research processes. Project administration was carried out by D.R., and J.W. secured the funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by Science Foundation Ireland grant 13/RC/2094_P2 and co-funded under the European Regional Development Fund through the Southern & Eastern Regional Operational Programme to Lero—the Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Software lero.ie.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The study utilizes the APS Failure at Scania Trucks dataset, which can be accessed through the UCI Repository [22,23].

Acknowledgments

The authors have carefully reviewed, refined, and approved the final manuscript and accept full responsibility for its content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Akpudo, U.E.; Hur, J.-W. Towards Bearing Failure Prognostics: A Practical Comparison between Data-Driven Methods for Industrial Applications. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2020, 34, 4161–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallioris, P.; Aivazidou, E.; Bechtsis, D. Predictive Maintenance in Industry 4.0: A Systematic Multi-Sector Mapping. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 50, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucar, A.; Karakose, M.; Kırımça, N. Artificial Intelligence for Predictive Maintenance Applications: Key Components, Trustworthiness, and Future Trends. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mba, D.; Lin, T.; Yang, Y.; Loukopoulos, P. Just-in-Time Learning Based Probabilistic Gradient Boosting Tree for Valve Failure Prognostics. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 150, 107253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, M.; Cavique, L. Mitigating False Negatives in Imbalanced Datasets: An Ensemble Approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 262, 125674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wong, A.K.C.; Kamel, M.S. Classification of Imbalanced Data: A Review. Int. J. Patt. Recogn. Artif. Intell. 2009, 23, 687–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T.P.; Soares, F.A.; Vita, R.; Francisco, R.d.P.; Basto, J.P.; Alcalá, S.G. A Systematic Literature Review of Machine Learning Methods Applied to Predictive Maintenance. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 137, 106024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Oh, J.; Park, J. Maintenance Time Prediction for Predictive Maintenance of Ship Engines. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.T.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X.B. Artificial Neural Networks in Condition Monitoring and Fault Diagnosis of Nuclear Power Plants: A Concise Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Nuclear Engineering, Virtual Conference, 4–5 August 2020; American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME): New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 83778, p. V002T08A032. [Google Scholar]

- Langone, R.; Cuzzocrea, A.; Skantzos, N. Interpretable Anomaly Prediction: Predicting Anomalous Behavior in Industry 4.0 Settings via Regularized Logistic Regression Tools. Data Knowl. Eng. 2020, 130, 101850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafraz, G.; Behnamnia, A.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Balapour, A.; Meghrazi, A.; Rabiee, H.R. Domain Adaptation and Generalization of Functional Medical Data: A Systematic Survey of Brain Data. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaswad, S.; Xiang, Y. A Review on Condition-Based Maintenance Optimization Models for Stochastically Deteriorating System. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 157, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Guchhait, P.K.; Banerjee, R.; Srivastava, A.K.; Vishwakarma, D.N.; Saket, R.K. A Comprehensive Review of Condition Based Prognostic Maintenance (CBPM) for Induction Motor. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 90690–90704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafatelis, A.S.; Nomikos, N.; Giannopoulos, A.; Alexandridis, G.; Karditsa, A.; Trakadas, P. Towards Predictive Maintenance in the Maritime Industry: A Component-Based Overview. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.O.A.; Wong, M.D.; Nandi, A.K. Effects of Deep Neural Network Parameters on Classification of Bearing Faults. In Proceedings of the IECON 2016-42nd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Florence, Italy, 23–26 October 2016; pp. 6329–6334. [Google Scholar]

- Molęda, M.; Małysiak-Mrozek, B.; Ding, W.; Sunderam, V.; Mrozek, D. From Corrective to Predictive Maintenance—A Review of Maintenance Approaches for the Power Industry. Sensors 2023, 23, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targ, S.; Almeida, D.; Lyman, K. Resnet in Resnet: Generalizing Residual Architectures. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Learning Representations, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2–4 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Karayalcin, S.; Perin, G.; Picek, S. Resolving the Doubts: On the Construction and Use of ResNets for Side-Channel Analysis. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, W.; Tao, L.; Ma, J. Transfer Learning Strategies for Deep Learning-Based PHM Algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tony, L.; Jonas, B. APS Failure at Scania Trucks [Dataset]. 2016. UCI Machine Learning Repository. Available online: https://doi.org/10.24432/C51S51 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Kelly, M.; Longjohn, R.; Nottingham, K. The UCI Machine Learning Repository. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Hu, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Jia, L. Network Traffic Prediction for Multiple Providers in Digital Twin-Assisted NFV-Enabled Network. Electronics 2025, 14, 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; Shao, D.; Kit, F.C.; Dong, C. HyADS: A Hybrid Lightweight Anomaly Detection Framework for Edge-Based Industrial Systems with Limited Data. Electronics 2025, 14, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, T.N.; Gaspar, R.; Lins, R.G.; Junior, E.J.H. Data-Driven Methodology for Predictive Maintenance of Commercial Vehicle Turbochargers. In Proceedings of the 2023 15th IEEE International Conference on Industry Applications (INDUSCON), São Bernardo do Campo, Brazil, 22–24 November 2023; pp. 807–814. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, T.; Cheng, L. Truck APS Fault Detection Based on Modified Mahalanobis-Taguchi System. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th Information Communication Technologies Conference (ICTC), Nanjing, China, 17–19 May 2023; pp. 379–383. [Google Scholar]

- Farea, S.M.; Mumcuoglu, M.E.; Unel, M. An Explainable AI Approach for Detecting Failures in Air Pressure Systems. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 173, 109441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumcuoglu, M.E.; Farea, S.M.; Unel, M.; Mise, S.; Unsal, S.; Cevik, E.; Yilmaz, M.; Koprubasi, K. Detecting APS Failures Using LSTM-AE and Anomaly Transformer Enhanced with Human Expert Analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 165, 108811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyalika, C.; Wickramarachchi, R.; El Kalach, F.; Harik, R.; Sheth, A. Evaluating the Role of Data Enrichment Approaches towards Rare Event Analysis in Manufacturing. Sensors 2024, 24, 5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.F.; Nascimento, M.A. IDA 2016 Industrial Challenge: Using Machine Learning for Predicting Failures. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Intelligent Data Analysis (IDA 2016); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R.K.G.; Togashi, K. Convolutional Neural Networks: An Overview and Application in Radiology. Insights Imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, W.; Peng, S.; Zhou, J. A Survey of Convolutional Neural Networks: Analysis, Applications, and Prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 6999–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Deveci, M.; Parmar, M. A Review of Convolutional Neural Networks in Computer Vision. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inneci, T.; Badem, H. Detection of Corneal Ulcer Using a Genetic Algorithm-Based Image Selection and Residual Neural Network. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; Wu, Q. Distributed Classification by Divide and Conquer Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Computing and Machine Intelligence (ICMI), Mt Pleasant, MI, USA, 13–14 April 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tanhandiki, K.; Dallakehnejad, M.; Rahimi Asiabaraki, H. Reducing Air Pressure System Repair Costs in Scania Trucks through Deep Learning. J. Eng. Appl. Res. 2024, 1, 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.A.; Prasad V, P.N.S.B.S.V.; Kodali, R.; Rapaka, L.; Sanki, P.K. Predicting and Categorizing Air Pressure System Failures in Scania Trucks Using Machine Learning. J. Electron. Mater. 2024, 53, 3603–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamm, S.; Kumar, P.; Jazdi, N.; Weyrich, M. An Architecture for Adaptive Machine Learning Models Using Adversarial and Transfer Learning. Procedia CIRP 2023, 120, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilet, C.; Guyomard, M.; Destercke, S.; Fillatre, L. Classifieur Minimax Discret Randomisé Pour La Détection de Classes Rares et La Présence de Probabilités a Priori Imprécises. In Proceedings of the 29th GRETSI Symposium on Signal and Image Processing, Grenoble, France, 1 September 2023; Available online: https://gretsi.fr/data/colloque/pdf/2023_gilet1254.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Cao, B.; Fan, J. Improving the Accuracy of Learning Example Weights for Imbalance Classification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2022), New Orleans, LA, USA, 25–29 April 2022; OpenReview: Alameda, CA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://openreview.net/ (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Kafunah, J.; Ali, M.I.; Breslin, J.G. Handling Imbalanced Datasets for Robust Deep Neural Network-Based Fault Detection in Manufacturing Systems. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muideen, A.A.; Lee, C.K.M.; Chan, J.; Pang, B.; Alaka, H. Broad Embedded Logistic Regression Classifier for Prediction of Air Pressure Systems Failure. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Khan, M.; Khan, M.; Dawood, H.; Dawood, H.; Daud, A. Secure Explainable-AI Approach for Brake Faults Prediction in Heavy Transport. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 114940–114950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafunah, J.; Ali, M.I.; Breslin, J.G. Uncertainty-Aware Ensemble Combination Method for Quality Monitoring Fault Diagnosis in Safety-Related Products. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 1975–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).