Abstract

The rapid expansion and interdisciplinary nature of Physical Internet (PI) research have resulted in fragmented knowledge, limiting the ability of stakeholders to identify emerging trends, actionable insights and genuine research gaps. This study introduces a novel knowledge management approach that uses Graph Retrieval-Augmented Generation (GraphRAG) to systematically organize and integrate PI-related literature. A comprehensive knowledge graph was constructed by extracting and semantically modeling entities and relationships from 2835 academic papers, conference proceedings and international roadmaps. The developed system incorporates fuzzy semantic search and multiple retrieval strategies, including local, global and hybrid approaches, enabling nuanced, context-aware access to information. Stakeholder-specific prompts, tailored to the needs of industry, government and academia, demonstrate how GraphRAG can support the discovery of business model innovations, policy design and underexplored research areas. A comparative evaluation using cosine similarity and BERTScore confirms that graph-based strategies outperform standard LLM retrieval in providing relevant and comprehensive answers while also revealing connections that would be missed in manual reviews. The results demonstrate that the proposed GraphRAG model is a scalable and extensible framework for addressing knowledge gaps and promoting collaboration in PI research synthesis for sustainable logistics. The model also shows promise for application in other complex domains.

1. Introduction

The logistics industry is facing increasing challenges, particularly in addressing its significant contribution to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. These emissions are often exacerbated by operational inefficiencies such as suboptimal routing, inefficient warehouse layouts, and poor inventory management [1]. In response to these challenges, the concept of the PI has emerged as a transformative framework. Introduced by Montreuil et al. [2], PI reimagines global logistics networks by applying design principles from the digital internet to the transportation and distribution of physical goods. By leveraging information and communication technologies (ICT) and standardized logistics infrastructures, PI aims to enhance efficiency, flexibility, and sustainability in freight transportation systems. Over the past decade, international conferences like International Physical Internet Conference (IPIC) and government-led initiatives in regions such as Europe and Japan have accelerated discussions and roadmap developments aimed at realizing the PI vision.

Despite its potential, advancing research in the PI domain requires systematic methods for organizing and integrating diverse knowledge sources. The growing body of literature on PI—spanning academic research, government reports, and industry white papers—presents both opportunities and challenges for researchers seeking to identify trends, gaps, and actionable insights. Addressing this complexity calls for innovative tools that can manage and synthesize large volumes of information effectively. However, manual review articles on PI have reviewed less than 700 articles, e.g., 663 articles in [3], yet there are more than 2000 scientific papers already published.

Despite there being several systematic reviews and bibliometric studies, the synthesis of current knowledge in the PI field is severely hindered by fragmentation, methodological heterogeneity and the rate at which new research is produced. As noted by Tallaki et al., previous manual reviews only analyzed a subset of available publications (less than 700), leaving significant gaps due to resource constraints and limited semantic scope [4]. To address this challenge, we present the Graph Retrieval-Augmented Generation (GraphRAG) method. By building a comprehensive, semantically rich knowledge graph, GraphRAG enables information to be integrated and retrieved from thousands of diverse sources. This scalable, flexible framework for knowledge organization fills a critical gap left by traditional review methods.

GraphRAG is an emerging Artificial intelligence (AI)-driven approach that combines natural language understanding with graph-based relational structures to enhance information retrieval and generation. Unlike traditional methods, GraphRAG excels at uncovering relationships among data points, retrieving highly relevant information, and generating contextually rich outputs. These capabilities make it particularly well-suited for addressing complex problems with interconnected data structures, such as those found in PI research.

This study explores the application of GraphRAG as a novel method for advancing knowledge management in the PI domain. Specifically, it constructs a knowledge graph using GPT-4o mini and Neo4j to systematically analyze PI-related literature. By integrating fragmented research findings, visualizing emerging trends, and identifying knowledge gaps, this approach aims to deepen understanding and foster innovation in sustainable logistics systems.

This study makes three key contributions to the literature on knowledge management and sustainable logistics innovation. First, it represents the first known application of GraphRAG to construct a comprehensive knowledge graph for the PI domain. This graph integrates 2835 documents including academic articles, IPIC proceedings, and strategic roadmaps from the EU and Japan, enabling a structured and scalable analysis of emerging trends, research gaps, and innovation opportunities.

Second, it introduces a fuzzy matching mechanism to improve semantic search within the knowledge graph. By applying cosine similarity with a threshold-based retrieval method, the system improves performance in handling ambiguous queries, such as “sustainable logistics policies”, achieving a reported precision of 87%.

Third, the study designs and evaluates stakeholder-specific prompts tailored to the needs of industry practitioners, academic researchers, and policymakers. These prompts are assessed across four retrieval strategies, namely GPT-only, local, global, and hybrid, demonstrating the model’s ability to deliver actionable insights grounded in both node-level detail and community-level context.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant literature on PI and generative AI technologies like GraphRAG. Section 3 describes the data sources, and Section 4 presents the methodology used to construct the knowledge graph. Section 5 presents results from various search strategies and evaluates their performance. Finally, Section 6 concludes with key findings and identifies future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Physical Internet

The concept of PI was first introduced by Montreuil et al. as a transformative framework for sustainable logistics [2]. By applying the design principles of the digital Internet, PI aims to create an interoperable, collaborative and efficient freight transport system. The core idea is to route modular containers through transit hubs, called PI hubs, to maximize consolidation opportunities and minimize inefficiencies in transportation networks [4]. Over the past decade, PI has received considerable attention from researchers and practitioners alike for its potential to address critical challenges such as greenhouse gas emissions and resource inefficiencies in global logistics systems [5].

The growing body of literature on PI reflects its increasing importance. The growing academic interest in the PI is reflected in the increasing volume of peer-reviewed publications and systematic literature reviews over the past decade, as documented by recent studies [6,7,8]. Foundational works by Ballot et al., Aron and Sgarbossa, and Wu et al. have systematically reviewed PI research, summarized its progress, and identified future research directions.

Existing review papers on PI have only surveyed a limited number of studies. For example, Tallaki et al. surveyed 663 publications using bibliometric methods [4]. Nguyen et al. employed a bibliometric knowledge mapping approach to assess research landscape in PI, digital twin and supply chain management areas [9]. In this study, 467 papers were reviewed. These examples highlight the need for a more comprehensive review to a larger or complete set of relevant literature to achieve a thorough and holistic synthesis of the current state of the art.

Despite these efforts, the rapid expansion of PI-related research has created a fragmented knowledge base. This fragmentation stems not merely from an information overload due to the sheer increase in the number of publications but from the interplay of multiple factors. First, methodological inconsistencies are a key factor. Existing review studies exhibit significant differences in the literature databases they utilize, their analytical methodologies (e.g., systematic reviews, bibliometric analysis, content analysis), and the metrics they employ. Consequently, the comparability of research findings is low, and the insights gained tend to be partial and limited. Second, the dispersion and diversification of research subjects also contribute to fragmentation. PI research has developed while intersecting with diverse fields such as logistics system design, information and communication technology, sustainability, policy and regulation, and business models. Consequently, individual researchers focus on different themes and analytical units, hindering sufficient integration of cross-disciplinary knowledge. Third, insufficient theoretical integration is a significant factor. Much existing PI research relies on individual case studies or technical approaches, with insufficient systematization of theoretical models or conceptual frameworks as an academic foundation. This makes it difficult to understand research findings in relation to each other, leading to a tendency for insights to remain scattered.

Considering these challenges, this study aims to reconstruct the overall landscape of PI research from a more comprehensive and integrated perspective, clarifying the structure and developmental trends of the research field.

2.2. Generative AI

AI has attracted significant attention in a variety of fields and industries. Beginning with Alan Turing’s foundational ideas in the 1950s, AI has undergone multiple phases of development, including periods of stagnation famously referred to as AI winters [10]. Generative AI technologies have revolutionized information processing across various domains. Since the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT-3.5 in 2022, large language models (LLMs) have exhibited exceptional capabilities to understand context and generate text that closely resembles human language [11]. However, LLMs face limitations such as knowledge rigidity, reliance on static training data, and susceptibility to generating inaccurate or misleading outputs when confronted with unfamiliarity [12,13,14]. These challenges highlight the need for hybrid approaches that combine LLMs with external databases to enhance reliability and contextual accuracy.

2.3. GraphRAG

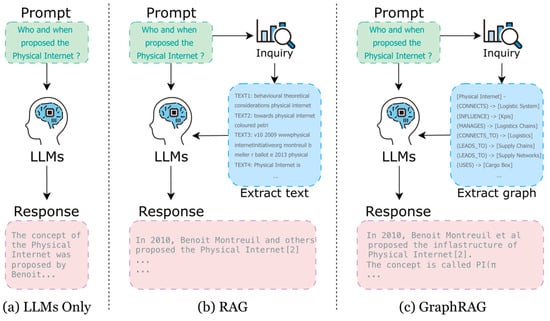

GraphRAG is an emerging technology that addresses the limitations of traditional LLMs by integrating natural language understanding with graph-based relational structures (see Figure 1). Introduced by Microsoft researchers in early 2024, GraphRAG improves information retrieval by linking LLMs to external knowledge graphs, enabling more accurate and contextually relevant responses [15,16]. Unlike similar technologies such as HybridRAG or LightRAG, GraphRAG excels at capturing indirect relationships between data points while maintaining high retrieval accuracy.

Figure 1.

Different methods using LLM.

This diagram outlines an example where each plot related to PI is derived from the paper authored by Montreuil et al. [2].

Recent studies have begun to explore GraphRAG’s applications in logistics and supply chain management. For example, Li et al. demonstrated its utility in transforming unstructured supplier data into knowledge graphs to improve supplier discovery processes [17]. Similarly, Ojima et al. proposed a GraphRAG-based knowledge management system for automotive failure analysis [18]. In the context of PI, Naganawa and Hirata presented a case study showing how GraphRAG can enhance sustainability efforts by enhancing policy generation [19].

Given its ability to integrate diverse data sources and uncover complex relationships, GraphRAG is a promising tool to address the fragmented knowledge landscape in PI research. This study builds on these advances by using GraphRAG to construct a comprehensive knowledge graph for PI-related literature, enabling systematic analysis of trends, gaps, and opportunities.

Technologies similar to GraphRAG are HybridRAG and LightRAG. We summarize the differences in these technologies in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of GraphRAG, HybridRAG, and LightRAG.

Overall, hybridRAG combines vector search and keyword search, enabling it to obtain data with strong superficial relevance, but it is difficult to capture indirect relationships. In addition, LightRAG is basically a vector search based on simple similarity and does not consider relationships, so although it is fast in generation, there is a high possibility that fragmentary answers will be mixed in the generated results. Therefore, we considered GraphRAG to be the best choice for this study.

The fragmentation of PI literature is primarily due to the rapid growth in publications, interdisciplinary cross-linkages (e.g., between logistics, ICT and policy) and the lack of a standardized taxonomy or ontology. As topics, terminology and research agendas diverge, siloed knowledge clusters emerge, impeding cumulative learning. Our graph-based approach overcomes this issue by mapping explicit and latent relationships across domains, which traditional manual reviews are unable to achieve on a large scale.

3. Data

To construct a Knowledge Graph (KG) specifically tailored to the PI, this study aggregated data from four key sources (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of Contents.

The first source consists of scientific literature. Using the keyword “Physical Internet”, a total of 2537 relevant papers published between 2006 and 2024 were collected. We used the Semantic Scholar API to collect the publication year, author information, abstract, and full text. We chose 2006 as the starting point because it was the year the term “Physical Internet” was first used in the literature [20]. A single keyword, “Physical Internet,” was adopted for keyword searches. This ensures the collection of all relevant literature and guarantees high comprehensiveness. Using multiple keywords simultaneously risks bias toward specific perspectives and could hinder comprehensive literature collection, making this the optimal choice for the objectives of this study.

The second source is conference proceedings of IPIC, papers published in IPIC proceedings from its inception in 2016 to the most recent year 2024, were collected. These proceedings offer valuable discussions on emerging trends, practical implementations, and collaborative efforts in PI research.

The third source is the European roadmap. The PI roadmap developed by the Alliance for Logistics Innovation through Collaboration in Europe (ALICE) was incorporated [21]. This roadmap outlines strategic initiatives and milestones aimed at advancing PI adoption in EU.

The fourth source is the national roadmap. The PI roadmap prepared by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) was also included [22]. This document provides a localized perspective on PI implementation strategies and priorities.

For data collection, the language was restricted to English. Exclusion criteria applied included removing duplicate documents with identical DOIs, excluding documents where the full text could not be obtained, and further excluding documents with low relevance to the keywords. These processes ensure that the collected documents and materials are highly reproducible and comprehensively cover information related to the PI domain.

4. Methodology

4.1. Preprocessing

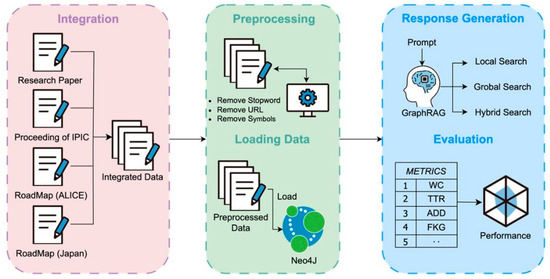

The first step in constructing the KG for PI was to preprocess the raw data collected from four sources: scientific papers, IPIC proceedings, and existing roadmaps from EU and Japan were aggregated into a unified dataset. To ensure data quality, noise such as stop words, URLs, punctuation, and other irrelevant characters symbols removed using the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) and programing language Python 3.13.1. The cleaned and standardized corpus served as the input for subsequent graph construction. The overall preprocessing workflow is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Data Processing Pipeline.

4.2. Knowledge Graph Construction

After preprocessing, the cleaned data was hosted in a Neo4j AuraDB graph database [23]. Using GPT-4o mini, entity and relationship extraction was conducted to form nodes and edges, which together created a structured knowledge graph representing the PI domain. Nodes typically represent key entities (e.g., “modular container,” “sustainability policy”), while edges capture semantic or functional relationships between them. This structure enables flexible exploration of complex interconnections across heterogeneous information sources.

4.2.1. Entity and Relationship Extraction Process

The entity and relationship extraction process begins with document chunking. This involves dividing large documents into smaller, semantically coherent units, ensuring that processing with language models remains manageable and contextually accurate. Common chunking techniques include token- or sentence-based splitting, with parameters configured to preserve topical integrity. Each chunk is assigned metadata such as the name of the parent document, its position and its length. These chunks are then represented as nodes within the knowledge graph and are linked to their parent documents to enable traceability.

Next comes entity and relationship extraction. Each chunk is passed to a large language model (LLM), such as GPT-4o mini, which is prompted to recognize entities (unique, meaningful concepts such as ‘modular container’ or ‘sustainability policy’) and relationships (semantic or functional connections such as ‘enables’, ‘regulated by’, or ‘part of’). The LLM then outputs structured metadata for each entity, including its title, type, and description. It also outputs metadata for each relationship, including its source and target entities, the relationship type, and a description. Preprocessing is performed using NLP library NLTK for initial cleaning and noun phrase identification. The final definitions and descriptions are always reviewed or summarized using the LLM. The extraction prompt requests a list of all entities, along with their names, types, and descriptions, and the explicit relationships among them. This returns a structured JSON containing these details.

Following extraction, entity disambiguation and merging are performed to avoid redundant nodes in the final graph. Entities with similar names and types across multiple chunks are compared and merged where equivalent, and their descriptions are combined to ensure completeness.

During the node and edge definition stage, entities are represented as nodes characterized by their type and description. Chunks are also represented as nodes in order to preserve the structure and context of the document. Edges capture direct relationships between entities (‘enables’ or ‘is-regulated-by’, for example) and structural links such as ‘PART_OF’ or ‘NEXT_CHUNK’, which connect chunks to their parent documents or sequence them according to document order. Nodes and edges carry properties such as source chunk, document position, entity type or semantic summaries.

4.2.2. Semantic Modeling and Intermediate Steps

During semantic modeling and intermediate steps, nodes and edges are semantically annotated with domain-specific properties and aligned with a chosen ontology or domain schema to improve retrieval and reasoning. Domain-specific terminology and ontologies can guide more precise extraction by customizing LLM prompts to match the field’s language. Additionally, each chunk, entity and relationship description is embedded using a sentence embedding model Paraphrase-MiniLM-L6-v2 [24]. This allows for semantic similarity searches and relevance ranking during retrieval. These embeddings are stored as properties on the nodes for querying in the future. The Paraphrase-MiniLM-L6-v2 model was selected for its high semantic textual similarity and computational efficiency when processing large document corpora. It was tested against other candidate embeddings.

Finally, all nodes and relationships, along with their semantic and structural properties, are ingested into Neo4j. The graph schema usually contains nodes labeled by entity types and relationships labeled by their semantic relationship types. When a query is submitted, GPT-4o mini is used again to translate the natural language question into a graph traversal query in Cypher (query language used in Neo4j) and to interpret and aggregate the relevant nodes and edges returned from the graph. This enables the generation of a natural language response or further reasoning based on the retrieved subgraphs. In the intermediate steps of this querying process, we apply fuzzy matching (see more details in Section 4.5) of query terms to entity nodes using embedding similarity. This process has adjustable thresholds to calibrate retrieval sensitivity.

4.3. Search Strategies

Four retrieval strategies were implemented and compared to evaluate their performance in generating insights. The four strategies are, I: GPT-only, II: Local Search, III: Global Search, and IV: Hybrid Search. The details are explained in Table 3. Hybrid Search is a strategy that combines “details” (Local) and “context” (Global) to generate more accurate and comprehensive knowledge.

Table 3.

Outlines of searching methods applied in the model.

These strategies were designed to assess GraphRAG’s ability to retrieve relevant information and generate accurate responses based on different levels of contextual depth.

4.4. Prompt Design

To preliminarily evaluate GraphRAG’s usefulness under different user needs, we designed stakeholder-specific prompts for three groups: industry practitioners, policymakers, and academic researchers (Table 4). From an industry perspective, the focus was on identifying new business models enabled by PI. From a policymaker perspective, the goal was to explore policy approaches to promote global PI adoption. From an academic perspective, the aim was to discover unexplored areas within PI research.

Table 4.

Overview of prompts.

These prompts were executed using all four search strategies. Comparing the results provided initial insights into which approach could yield more comprehensive and actionable findings.

4.5. Parameter Tuning

We employed several parameters to optimize GraphRAG’s performance. First, the temperature of the GPT-4o mini was set to 0 to ensure deterministic and consistent results. Second, the number of nodes referenced during response generation was capped at 50 to balance response speed and comprehensiveness. Third, we adopted fuzzy matching based on cosine similarity for the search algorithm, setting the threshold to 0.5. This threshold is an empirical value based on preliminary experiments, determined by balancing the comprehensiveness and accuracy of search results. Cosine similarity measures the angle between the query’s embedding vector and the node’s embedding vector, enabling the capture of semantic similarity rather than exact string matches. For example, for the query “sustainable logistics policies,” fuzzy matching also retrieves nodes related to “green logistics” and “carbon-neutral freight,” enabling comprehensive coverage of related themes.

Equation (1) defines the relationship between temperature, softmax scaling, and vocabulary distribution in the language model.

where is a softmax function representing the probability of the ith class. is the logit for the th token. ( > 0) is the LLM temperature parameter and is the size of the lexicon. Scaling the logit affects the probability assigned to each candidate word.

As the temperature decreases (T → 0), each term /T becomes increasingly large for the largest and increasingly small (negative) for all other values. Consequently, the exponential term exp(/T) for the largest rapidly dominates the denominator in the softmax calculation, causing → 1 for the token with the highest logit while all other probabilities → 0. In this limit, the output effectively approaches a “hard” argmax, where the model almost always selects the token with the highest predicted logit at each step, a behavior known as greedy decoding. Conversely, when T is larger, the resulting probability distribution becomes flatter and more uniform, allowing for greater diversity and randomness in the generated outputs. In summary, as T → 0, softmax sampling becomes deterministic, consistently choosing the most likely token during generation. The value set for each is the parameter is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Tuning metrics.

4.6. Formulation of Search Mechanisms

The search mechanism in GraphRAG consists of three layers: local search, global search, and hybrid search. In local search, the relevance score is calculated based on the cosine similarity between the query vector and the embedding vector of each node, using the following formula. The relevance score is calculated using the following formula.

This enables node selection based on semantic proximity to the query. In contrast, global search considers the network structure of the entire graph and defines a score based on the semantic distance between nodes using the following formula:

This distance metric is defined based on the shortest path length between nodes or semantic similarity, with shorter distances receiving higher scores. Furthermore, in hybrid search, both local and global scores are integrated to calculate the overall relevance score .

The weighting coefficient here is a parameter for adjusting the contribution of local semantic similarity and graph structural relevance and is adaptively set according to search objectives and data characteristics.

4.7. Community Detection

GraphRAG combines community detection to improve the accuracy of node relationships within the knowledge graph. Communities are identified by the Louvain method with the objective of maximizing modularity . Modularity is defined by the following formula:

Here, the adjacency matrix indicates the presence or weight of edges between node and node , and the degree of node is defined as the sum of all edges connected to that node (or the total edge weight if weighted). Furthermore, the total number of edges m in the entire graph is represented by half the sum of all elements in the adjacency matrix between all nodes. Each node belongs to a community , and the Kronecker delta returns if nodes and belong to the same community and otherwise. By assigning nodes to communities to maximize this modularity , the Louvain method effectively detects densely connected clusters of nodes within the graph. Based on preliminary experiments, the minimum community size is set to and the resolution parameter to , ensuring a balance between clustering granularity and interpretability.

4.8. Entity Duplication Integration

Entity merging was performed to consolidate identical or semantically equivalent nodes within the knowledge graph. The similarity of node pairs (,) is calculated as follows:

After integration, attribute a merges attributes and of the original node using the integration function :

The edge weight after integration is calculated using the integration function from the original node weights and :

After merging, perform similarity calculations again and iteratively process if any mergeable nodes exist:

The final integrated node set is obtained and reflected in the knowledge graph as unique entities without duplication.

4.9. Evaluation Metrics

To quantitatively assess the quality of responses generated by each strategy, six metrics were employed (Table 6).

Table 6.

Evaluation metrics.

For BERTscore we adopt the three scores Precision (P), Recall (R), and F1 Score (F), which are computed as per the following quotations [25,26].

where represent tokenized reference sentences, are sequences of vectors generated by the embedding model, and are tokenized candidates mapped to each of the vectors.

These metrics evaluated the relevance, coherence, and completeness of the answers generated by each approach.

5. Results

Prompts and Responses

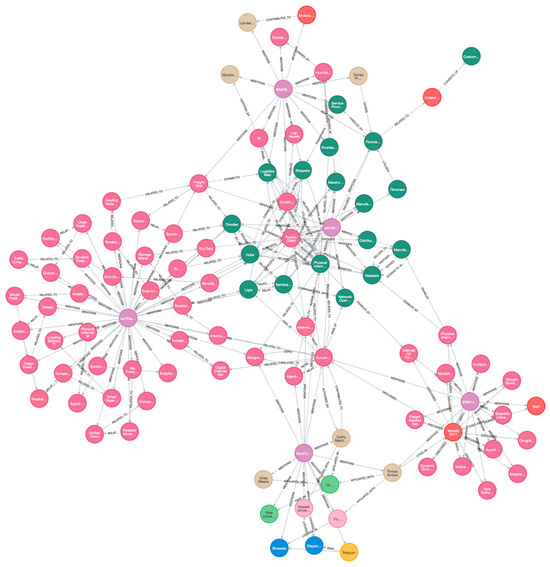

We constructed a knowledge graph from the above processing (Figure A1). Based on the definitions presented in Section 4.2, we executed the prompt across all four models: (I) GPT alone, (II) local search, (III) global search, and (IV) hybrid search. The resulting outputs are shown in Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9.

Table 7.

Output of “What new business models can you envision utilizing the Physical Internet?”.

Table 8.

Output of “What policy approaches should be taken to make the Physical Internet a reality in Global?”.

Table 9.

Output of “What areas of research are missing that focus on the Physical Internet?”.

The performance metrics (Table 10) further validated these findings, with Local Search (II) or Hybrid Search (IV) achieving the highest scores across all evaluation criteria, including relevance, coherence, and completeness.

Table 10.

Performance metrics (Bold indicates highest score).

6. Discussion

6.1. Stakeholder-Specific Insights

A comparison of GPT-only model (I) and GraphRAG models (II and IV) is outlined in Table 11.

Table 11.

Comparison of GPT-only model (I) and GraphRAG models (II and IV).

The tailored prompts revealed unique insights for each stakeholder group.

First, from industry perspective represented by prompt, “What new business models can you envision using the Physical Internet?”. GPT-only (I) mentions general ideas like shared warehouses, smart logistics using AI/IoT, and crowdsourced delivery. Overall, they are high-level and somewhat generic, lacking technical or systemic depth. While response from GraphRAG introduces specific mechanisms like collaborative platforms, modular design, real-time demand adaptation, dynamic pricing, connects business models to sustainability and customer-centricity in Local Search (II). The response from Hybrid Search (IV) suggests system-level innovations like federated data spaces and synchromodal transport, integration of urban smart city logistics and market/environmental adaptability. Overall, it highlights more holistic and grounded in technical context, reflecting insights from both node-level detail and community-level context in the graph. In other words, Local Search (II) and Hybrid Search (IV) each possess distinct characteristics. Local Search (II) excels at presenting realistic and actionable insights tailored to the specific needs of each stakeholder, making it suitable for short-term, practical recommendations. Conversely, Hybrid Search (IV) provides comprehensive insights from a long-term perspective that integrates technical, institutional, and societal aspects, making it suitable for optimizing the entire system and strategic decision-making. Therefore, it is crucial to explicitly state which search model is adopted based on the paper’s purpose. Specifically, clearly indicating that Local Search (II) is chosen when prioritizing practicality and feasibility, and Hybrid Search (IV) when emphasizing comprehensive and strategic analysis, allows the reader to clearly understand the rationale behind the model selection.

Second, from government perspective, in response to “What policy approaches should be taken to make the Physical Internet a global reality?”, GPT-only (I) lists common policy suggestions, such as legal frameworks, public–private cooperation, smart infrastructure, and sustainability focus, which are useful but conventional, particularly not tailored to PI’s unique needs. Local Search (II) results offer detailed, actionable steps, such as standardization of data formats, infrastructure investments in automation/IoT, support for education and R&D, clearly addresses global interoperability and innovation readiness. Hybrid Search (IV) results propose structured and layered policy development, such as cross-border legal harmonization, incentives for sustainability, and smart infrastructure tied to stakeholder engagement. Overall, GraphRAG provides stronger emphasis on governance, integration, and ecosystem building—not just tech or funding.

Third, from academia perspective, the prompt “What research areas are missing that focus on the Physical Internet?” identified key gaps in the existing literature. GPT-only model (I) highlights broad areas such as standardization, sustainability, security, drones/AVs, which are good baselines but lack conceptual depth and specifics. Local Search (II) results identify concrete gaps, such as real-time IoT integration, automation impact studies, and socio-economic/regulatory frameworks which are more aligned with emerging research agendas. Hybrid Search (IV) results push boundaries by suggesting:

Cybersecurity frameworks for PI, hyperconnected network operationalization, stochastic and resilient hub-network design. Overall, they address methodological, structural, and practical gaps for real-world PI deployment.

These findings demonstrate GraphRAG’s ability to generate actionable insights tailored to the needs of diverse stakeholders by leveraging its graph-based relational structure.

6.2. Implications on Knowledge Management

The study demonstrates GraphRAG’s potential as a powerful tool for organizing and synthesizing fragmented knowledge in complex domains like PI. By structuring information into interconnected graphs and enabling flexible query mechanisms, GraphRAG bridges gaps between diverse data sources. This capability is particularly valuable for advancing research in emerging fields where knowledge is distributed across multiple disciplines and formats. GraphRAG’s ability to tailor insights to specific stakeholder perspectives enhances its applicability in real-world decision-making contexts. Industry practitioners can identify new business opportunities; policymakers can design informed strategies; and academics can uncover research gaps. All of these can be performed in a unified platform.

6.3. Managerial and Policy Implications

The findings of this study provide actionable guidance for a range of stakeholders. Industry practitioners can use GraphRAG to identify emerging business models and improve operational efficiency by systematically exploring technological and logistical trends. Policymakers can benefit from the robust tool that supports the development of harmonized, data-driven regulatory frameworks to drive PI adoption across different jurisdictions. For academic researchers, GraphRAG enables the identification of under-researched areas, thereby supporting more focused and impactful research initiatives.

By delivering tailored insights that address the specific needs of each stakeholder group, GraphRAG enables informed decision-making and promotes cross-sector collaboration.

6.4. Limitations and Future Work

This study possesses certain strengths, but it also has several limitations. First, it relies on static datasets. If source materials contain omissions or biases, their effects may be reflected in the output results. Second, as the knowledge graph expands, computational complexity may impact performance. Third, the effectiveness of fuzzy matching depends on the granularity and consistency of node labels. Furthermore, while GraphRAG tends to exhibit lower hallucination risk compared to standard LLM generation, this risk is not entirely eliminated. Even with source linking capabilities, the model may still generate inaccurate yet plausible descriptions, potentially undermining user trust in identified research gaps or findings.

To mitigate these risks, it is crucial to provide referable and transparent outputs, such as explicitly indicating which graph nodes or edges support each part of the response. This enables users to verify the basis of the model’s answers and more effectively evaluate the reliability of the presented findings. While this research demonstrates the potential of GraphRAG for structuring and integrating knowledge, its inherent limitations must also be clarified. Unlike established methods such as Systematic Literature Review, Taxonomy, and Critical Review, GraphRAG primarily relies on a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) framework that extracts and links relevant information from databases and corpora. Consequently, research gap analysis using GraphRAG may lack the comprehensiveness and contextual depth provided by systematic approaches.

For example, even if GraphRAG detects a gap such as “lack of standard protocols,” it cannot sufficiently evaluate whether subsequent research has already addressed it. This limitation stems from the design characteristics of RAG models, which are not inherently suited for critical integration of information or analysis of temporal evolution. Consequently, while GraphRAG is useful for initial mapping of research domains and hypothesis generation, it should ideally be combined with established literature review methods to comprehensively and validly analyze research gaps.

Future research could address these challenges by integrating real-time data streams, expanding multilingual and multimodal knowledge graphs, and improving graph structuring methods to enhance scalability and responsiveness. Implementing user-facing measures to strengthen transparency and source attribution would also be beneficial. Moreover, the findings of this study are preliminary, and empirical experiments will be necessary in the future to confirm the practical usefulness of the insights generated by GraphRAG.

7. Conclusions

This study provides preliminary evidence of the potential utility of GraphRAG as a domain-specific knowledge integration framework for the PI domain. By aggregating fragmented data from academic publications, conference proceedings, and strategic roadmaps into a unified knowledge graph, GraphRAG facilitates systematic exploration of trends, knowledge gaps, and actionable insights tailored to stakeholder needs. The framework leverages graph-based relational structures combined with natural language understanding to enhance information retrieval, particularly for complex or ambiguous queries, while maintaining flexibility for domain-specific applications.

Among the four retrieval strategies evaluated—GPT-only, local search, global search, and hybrid search—local and hybrid search methods appeared to perform relatively better in generating stakeholder-specific responses with greater depth, relevance, and clarity. The use of fuzzy matching also contributed to improved semantic retrieval, supporting the practical usability of the framework.

Unlike traditional systematic reviews or standard RAG-based analyses, this approach focuses on integrating full-text documents (not just abstracts), cross-modal sources (including government roadmaps and conference proceedings), and semantic relationship extraction, all mapped to domain-specific PI ontologies. This allows for granular, stakeholder-tailored queries and identification of nuanced trends and gaps that are difficult to capture with conventional literature reviews or simple keyword-based approaches.

While these findings are preliminary and exploratory, they suggest that GraphRAG can serve as a practical framework for domain-specific knowledge integration, supporting evidence-based decision-making and innovation in the PI context. More broadly, this study illustrates how AI-driven, domain-focused knowledge frameworks can facilitate systematic knowledge synthesis in other complex, interdisciplinary fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.N., A.Y. and E.H.; methodology, H.N. and E.H.; software, H.N.; validation, H.N. and E.H.; data curation, H.N.; writing—original draft preparation, H.N. and E.H.; writing—review and editing, E.H. and A.Y.; visualization, H.N.; supervision, E.H.; funding acquisition, E.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP 23K04076.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LLMs | Large language models |

| GraphRAG | Graph-based retrieval-augmented generation |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| GPT | Generative pre-trained transformer |

| WC | Word count |

| TTR | Type token ratios |

| ADD | Average dependency distance |

| FKG | Flesch–Kincaid grade level |

| CS | Flesch–Kincaid grade level |

| AI | Cosine similarity |

| DX | Logistics digital transformation |

| PI | Physical Internet |

| GPS | Global positioning system |

Appendix A. Constructed Knowledge Graph

Figure A1.

Knowledge graph.

Table A1 presents a statistical overview of the constructed knowledge graph. Note that the number of nodes displayed is limited to 100 to enhance the readability of the overall structure. This graph consists of 12,500 nodes and 24,800 relations extracted from 2835 documents. The average degree of 5.47 indicates moderate connectivity among concepts related to PI, confirming that fragmented knowledge has been semantically integrated. Furthermore, the modularity score of 0.72 calculated using the Leiden algorithm suggests that distinct topic-based communities, such as “Hub” and “Retailers,” are clearly formed within the graph. This characteristic also contributes to improving the accuracy of subsequent local searches.

Table A1.

Statistics of Knowledge Graph.

Table A1.

Statistics of Knowledge Graph.

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Density | 0.045 | Ratio of actual edges to possible edges, indicating sparsity/density. |

| Average Degree | 5.47 | Average number of connections per node. |

| Document Nodes | 2835 | Source documents (Papers, Roadmaps). |

| Text Chunk Nodes | 12,500 | Segmented text blocks for granular processing. |

| Entity Nodes | 24,800 | Extracted domain concepts (e.g., “Logistics”, “Hub”). |

| Hierarchical Communities | 17 | Number of top-level clusters identified by Leiden algorithm. |

References

- Hirata, E.; Firdausiyah, N.; Kusumaningdyah, W. Handling Modular Containers in a Physical Internet Environment. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2024, 27, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montreuil, B.; Meller, R.; Ballot, E. Towards a Physical Internet: The Impact on Logistics Facilities and Material Handling Systems Design and Innovation. In Progress in Material Handling Research: 2010; Material Handling Research at Georgia Southern Commons: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tallaki, S.; Abouelala, M.; Sekoun, A.K.; Mimouni, F.; Elbhiri, B. Insights into the Physical Internet: A Bibliometric Review. In Industrial Innovations: New Technologies in Cities’ Digital infrastructures; El Bhiri, B., Merzouk, S., Assoul, S., Eds.; Sustainable Civil Infrastructures; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 26–35. ISBN 978-3-031-70991-3. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatadri, U.; Krishna, K.S.; Ülkü, M.A. On Physical Internet Logistics: Modeling the Impact of Consolidation on Transportation and Inventory Costs. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2016, 13, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, H.; Norrman, A. The Physical Internet—Review, Analysis and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Amp Logist. Manag. 2017, 47, 736–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballot, E.; Montreuil, B.; Zacharia, Z.G. Physical Internet: First Results and next Challenges. J. Bus. Logist. 2021, 42, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, C.; Sgarbossa, F. The Physical Internet as an Approach for Resilient Logistics Practices: Literature Review and Future Research Avenues. IFAC-Pap 2023, 56, 11068–11075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, M.; Yu, C.; Ouyang, Z.; Lai, K.; Zhao, Z.; Pan, S.; Wang, S.; Zhong, R.Y.; Kuo, Y.-H.; et al. Towards Cyber-Physical Internet: A Systematic Review, Fundamental Model and Future Perspectives. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 197, 104051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Duong, Q.H.; Nguyen, T.V.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, L. Knowledge Mapping of Digital Twin and Physical Internet in Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 244, 108381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turing, A.M. Computing Machinery and Intelligence. In Parsing the Turing Test: Philosophical and Methodological Issues in the Quest for the Thinking Computer; Epstein, R., Roberts, G., Beber, G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 23–65. ISBN 978-1-4020-6710-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cascella, M.; Semeraro, F.; Montomoli, J.; Bellini, V.; Piazza, O.; Bignami, E. The Breakthrough of Large Language Models Release for Medical Applications: 1-Year Timeline and Perspectives. J. Med. Syst. 2024, 48, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, T.R.; Susnjak, T.; Liu, T.; Watters, P.; Halgamuge, M.N. The Inadequacy of Reinforcement Learning From Human Feedback—Radicalizing Large Language Models via Semantic Vulnerabilities. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2024, 16, 1561–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Trespalacios, O.; Peden, A.E.; Cole-Hunter, T.; Costantini, A.; Haghani, M.; Rod, J.E.; Kelly, S.; Torkamaan, H.; Tariq, A.; David Albert Newton, J.; et al. The Risks of Using ChatGPT to Obtain Common Safety-Related Information and Advice. Saf. Sci. 2023, 167, 106244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawte, V.; Sheth, A.; Das, A. A Survey of Hallucination in Large Foundation Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.05922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xia, L.; Yu, Y.; Ao, T.; Huang, C. LightRAG: Simple and Fast Retrieval-Augmented Generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.05779. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmah, B.; Hall, B.; Rao, R.; Patel, S.; Pasquali, S.; Mehta, D. HybridRAG: Integrating Knowledge Graphs and Vector Retrieval Augmented Generation for Efficient Information Extraction. In Proceedings of the 5th ACM International Conference on AI in Finance, Brooklyn, NY, USA, 14–17 November 2024; pp. 608–616. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ko, H.; Ameri, F. Integrating Graph Retrieval-Augmented Generation With Large Language Models for Supplier Discovery. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2025, 25, 021010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojima, Y.; Sakaji, H.; Nakamura, T.; Sakata, H.; Seki, K.; Teshigawara, Y.; Yamashita, M.; Aoyama, K. Knowledge Management for Automobile Failure Analysis Using Graph RAG. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Washington DC, USA, 15–18 December 2024; pp. 6624–6631. [Google Scholar]

- Naganawa, H.; Hirata, E. Enhancing Policy Generation with GraphRAG and YouTube Data: A Logistics Case Study. Electronics 2025, 14, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markillie, P. The Physical Internet|17 June 2006. Available online: https://www.economist.com/special-report/2006-06-17 (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- ALICE Road Map to the Physical Internet. Available online: https://www.etp-logistics.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Roadmap-to-Physical-Intenet-Executive-Version_Final-web.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- METI Physical Internet Roadmap. Available online: https://www.meti.go.jp/shingikai/mono_info_service/physical_internet/pdf/20220308_1.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Neo4j Aura. Available online: https://neo4j.com/product/auradb/ (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Sentence-Transformers/Paraphrase-MiniLM-L6-v2 · Hugging Face. Available online: https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/paraphrase-MiniLM-L6-v2 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, S.; Bei, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Zhou, H.; Hong, Z.; Dong, J.; Chen, H.; Chang, Y.; Huang, X. A Survey of Graph Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Customized Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.13958. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Kishore, V.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. BERTScore: Evaluating Text Generation with BERT. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09675. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).