Abstract

A new type of household/therapeutic air freshener is proposed, in which beneficial components are released from compositions containing plant raw materials through induction heating under an alternating-frequency electromagnetic field. The composition is heated by metal elements (e.g., pieces of metal foil) included in its composition. The advantage of the proposed air freshener is the possibility of using a wide range of plant raw materials without prior additional processing. Another advantage of this air freshener is the possibility of controlling it via a smartphone, which is in line with the concept of a ‘smart home.’ The proposed approach bypasses labour-intensive production of simple oils, reduces the product cost, and expands the number of plants (helpful for small-scale cultivation in countries such as Kazakhstan). At the same time, however, it remains possible to use traditional compositions based on industrially produced aromatic oils. Specific examples of the implementation of the proposed method are presented. Prospects include programme-controlled emission of odours from polymer matrices, Internet of Things applications, implementation of sound–visual effects (colour–aroma–music), and even integration with neuromorphic materials.

1. Introduction

Aromatherapy products are currently widely used in clinical practice [1,2,3], including complementary therapy [4,5], and for correcting the psychophysiological state of users [6,7,8]. In particular, aromatherapy products are used to improve sleep quality [9,10,11], overcome anxiety [12,13], alleviate stress of various origins [14,15], etc.

One of the most common aromatherapy products is essential oils [16,17,18], which are also used in clinical practice [19,20]. The most common oils used are lavender [21,22], Melissa essential oil [23], bergamot [24], and citrus essential oils [25,26]. These oils are used, among other things, for massage [27,28] and inhalation [29,30,31]. In addition, aromatising products based on these oils are widely used for domestic purposes [32,33,34].

The production of essential oils is technologically quite complex [35,36,37], which determines the relatively narrow range of such oils that are actually used in practice. As shown in [38], the use of refined essential oils is not mandatory to achieve the goals set by aromatherapy. It is possible to extract aromatic substances directly from plant-based compositions by heating them in a high-frequency electromagnetic field. Similar methods are already widely used in practice. For example, Philip Morris Products SA has patented a tobacco heating system that also uses a high-frequency electromagnetic field to extract valuable components from plant-based raw materials [39]. The tobacco composition is heated by contact with a thin metal plate placed in a disposable cartridge (stick). Similar products have also been patented [40], which also involve the use of disposable elements (‘sticks’) containing a tobacco-based composition, with the difference that they are enclosed in a multilayer shell, one of the layers being electrically conductive (foil).

It should also be noted that heating substances in a high-frequency electromagnetic field is used for many other purposes [41,42,43], including in the food industry [44,45,46]. A very important issue here is the frequency of the electromagnetic field used. Direct heating of food products involves the use of a range corresponding to magnetrons. The use of low-frequency fields and currents is often much more convenient, which is also used in practice, including in the food industry [47,48]. However, direct heating with electric current is also far from always convenient, in particular due to the occurrence of parasitic electrode processes [49]. The use of compositions in which both a metal component with high electrical conductivity and a heated substance are present allows the use of a relatively low-frequency range (16 Hz) without direct contact between the substance and the electrodes. This approach is implemented in [39,40].

This paper proposes a specific device for extracting aromatic components from plant-based compositions, which can be used at least for domestic purposes (domestic air freshener). The advantage of this approach is that it eliminates the complex technological stages of essential oil production from the ‘plant cultivation–aromatic product consumption’ chain. Among other things, this makes it possible to utilise the potential of small farms, expand the range of plants used, and reduce the cost of aromatic products. The latter factor is very important for countries such as Kazakhstan, where aromatic products are widely available on the market but are unaffordable for most of the population due to their high prices. This approach has already been partially implemented in our work [49], where we proposed a device that uses a disposable cartridge filled with an electrically conductive composition containing salted plant material. The cartridge is equipped with contact pads to ensure the flow of current, which heats the composition. However, such a system has significant drawbacks: the contact pads of the device itself require regular cleaning, and the cartridge containing the electrically conductive liquid medium must be sealed to prevent it from drying out.

The proposed approach also involves integrating the developed air freshener with the increasingly popular concept of the ‘smart home’ [50,51,52]. This is ensured by the fact that the proposed equipment can be controlled directly from the user’s smartphone or iPhone, i.e., it uses the same approach as in previously developed circuits for other purposes [53,54].

2. Methods

Standard methods of designing and pre-testing electronic circuits were used with the help of EasyEda and VisualStudio 2022 v17.14 software products.

The electronic circuits were manufactured after the order was placed remotely on the website of the printed circuit board manufacturer JLCPCB.

To study the effectiveness of the high-frequency field on the plant-based composition, specially assembled equipment was used to record changes in the weight of the cartridge filled with the composition depending on the time and current in the inductance coil.

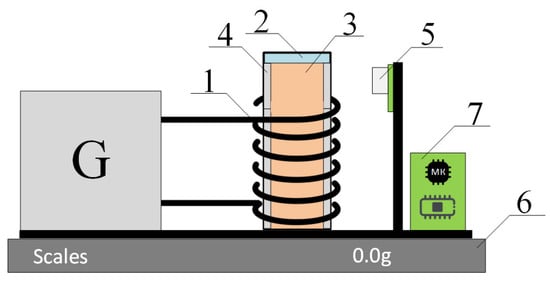

The general diagram of the equipment is shown in Figure 1, and its electronic diagram is shown in Figure 2. The equipment includes an inductance coil (1), inside which there is a cartridge (2) with the composition under study containing plant raw materials (3), as well as a shell made of foil (4), a temperature sensor (5), electronic scales (6), and a control circuit (7) identical to the control circuit in the final product.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the measuring equipment.

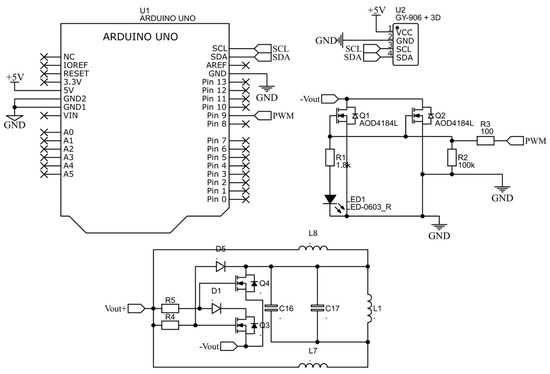

Figure 2.

Radio-electronic diagram of the measuring equipment.

The radio-electronic circuit consists of an Arduino Uno with a PWM output and an MLX90614 IR temperature sensor (GY-906 module) via I2C, as well as a driver node on a pair of AOD4184L MOSFETs (Q1, Q2) with circuits R1–R3 and an LED1 indicator, which generates Vout+/Vout− signals for the power section. The induction heater node consists of power MOSFETs Q3, Q4 (half-bridge/driver), their reverse diodes D1, D5, the resonant circuit L1–C16–C17, input chokes/filters L7, L8, gate resistors R4–R5 and the power supply bus. The power is regulated by the PWM duty cycle.

Let us outline the main characteristics of the circuit used. A standard ZVS induction heater module was used, in which the resonant circuit is formed by a coil and two parallel capacitors of ≈330 nF each, i.e., the total equivalent capacitance is ≈0.66 μF, L ≈ 1.5 μH. The resonant frequency of the current is f0 ≈ 160 kHz, which is confirmed by measurements using an oscilloscope. At a supply voltage of U = 7.4 V, the no-load power is ≈4.27 W (no-load current 0.577 A), and in the presence of a heated object (mass of metal inclusions 2 grams) it is ≈4.54 W (no-load current 0.613 A).

It should also be noted that the maximum permissible drain-source voltage for the MOSFET 24N6LG (NTD24N06LG) is 60 V. Oscillographic measurements of the VDS(t) voltage on one of the transistors at Upit = 7.4 V showed:

- -

- A mode characteristic of the half-bridge mode of the ZVS inverter: the current in the circuit is close to sinusoidal, and the transistors switch at a low VDS(t) (a mode close to zero switching);

- -

- The maximum measured drain-source voltage value: VDS,max ≈ 39 V, which is significantly lower than the maximum permissible 60 V and provides a voltage margin of about 35%.

3. Results

3.1. Aromatiser Design

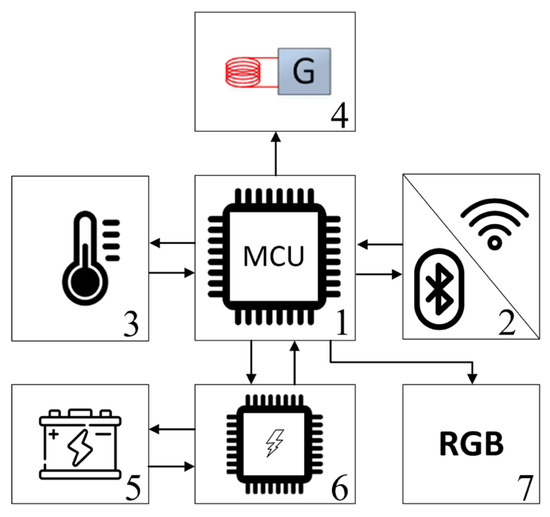

The design of the proposed type of aromatiser (Figure 3) involves heating a disposable cartridge filled with a plant-based composition. The cartridge is placed inside the coil of an induction heater (4). There are two cartridge designs. One uses a mixture of plant-based raw materials with metal inclusions, while the other uses a metal cartridge shell to provide heating.

Figure 3.

Functional diagram of the proposed type of air freshener; 1—microcontroller; 2—Bluetooth, Wi-Fi module; 3—temperature sensor; 4—induction heater; 5—rechargeable battery; 6—charge controller; 7—addressable RGB LED.

The air freshener is controlled by a microcontroller (1), which sets the frequency and current strength in the heater’s inductance coil (4). Specifically, these parameters are regulated as follows. The system operates in a closed temperature loop. The microcontroller controls the power supply to the induction heater via a MOSFET switch. The current temperature is read from an infrared sensor via the I2C interface, compared with the set value and fed to the PID controller. The output of the PID controller generates a PWM signal with the corresponding duty cycle (duty factor), thereby implementing pulse width modulation control of the heater power.

A temperature sensor is also connected to the microcontroller (1), providing the ability to adjust the heating mode of the cartridge with the initial raw material through feedback.

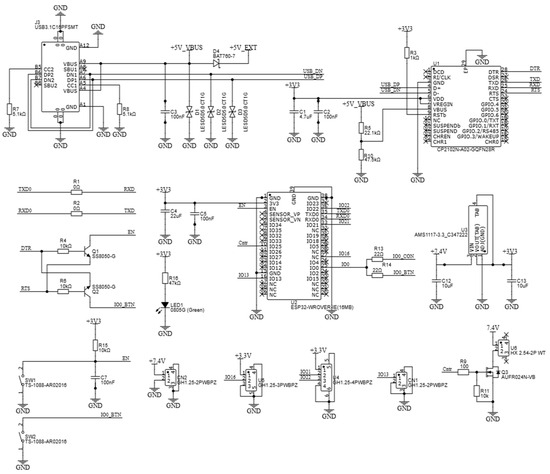

This design is implemented using the electronic circuit shown in Figure 4. Based on ergonomic considerations, we developed the following design for the proposed device (Figure 5). This figure emphasises that the aroma diffuser is controlled using a smartphone.

Figure 4.

Electronic diagram of the control unit of the air freshener.

Figure 5.

Design of the proposed device (comparison of dimensions with a smartphone designed to control the aroma diffuser).

This design involves the use of separate printed circuit boards that ensure the device functions in accordance with the methodology previously proposed in [38,55]. The device consists of two printed circuit boards, each of which performs its own task, but together they form a single intelligent control module for an induction heater with accurate charge accounting and an addressable LED strip.

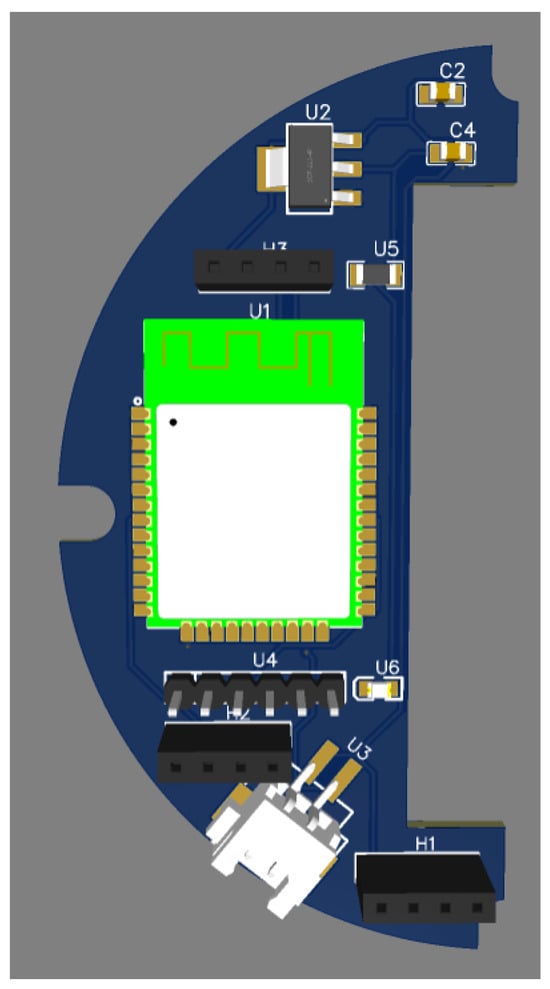

On the first, ‘control’ board (Figure 6), the ESP32 is located in the centre, powered by a 3.3 V AMS1117 linear regulator, which provides clean and stable power not only to the microcontroller itself, but also to the MLX90614 infrared sensor connected via the U3 connector via a two-wire I2C interface (SDA/SCL are pulled up to 3.3 V by 10 kΩ resistors), and the TI BQ27441 precision charge accounting module, which operates on the same bus and is powered from the same 3.3 V line. The 18650 battery with DW01/FS8205A protection is charged via TP4056, which is supplied with 5 V and ground via USB Type C, and on the CC lines via two 5.1 kΩ resistors. The ESP32 uses a timer to generate a 50 kHz PWM signal to control the MOSFET gate of the module’s ZVS key, while the heating algorithm is implemented as a PID controller that reads the evaporator temperature via I2C, corrects the duty cycle in real time, and ensures a smooth increase in power without current surges; at the same time, the TIM timer generates a single-wire DIN signal (800 kHz, 24 bits) for the WS2812 addressable LED strip, the level of which is converted from 3.3 to 5 V via a 74AHCT125 buffer, and the strip itself is powered by a separate step-up DC module up to 5 V. The logic for changing the display colours is implemented in a separate FreeRTOS task: blue-white gradient animation during warm-up, green flashing when the target temperature is reached, and energy-saving red pulsing when the charge level is <20%, at which point the ESP32 instantly resets the ZVS PWM and activates energy-saving mode. For additional diagnostics, the battery voltage is monitored redundantly via ADC with a 100 kΩ, 47 kΩ divider.

Figure 6.

Printed circuit board of the control unit of proposed type of air freshener.

The power of the induction heater is regulated by pulse width modulation of the power supply to the finished ZVS module. Let us specify some specific characteristics. The output of the PID controller forms a dimensionless control signal u(k) ∈ [0, 1], which is linearly converted into duty cycle:

The microcontroller uses a standard 8-bit hardware PWM with a counter range of from 0 to 255. Accordingly, the duty cycle step is ≈0.39%. At a module supply voltage of U = 7.4 V, the measured maximum power consumption was approximately 4.5 W. In a first approximation, the average power of the heater is proportional to the duty cycle; therefore, the power modulation range in the mode used is from 0 to ≈4.5 W with a step of about 0.02 W. In a more general case, when the module is powered from the nominal voltage, the upper power limit is limited by the rated value of ≈24 W. The duty cycle range of about 10–100% proved to be practically significant for thermal stabilisation tasks.

The specified temperature regime is ensured by feedback and temperature measurement with the MLX90614 sensor. A standard method is used, namely, the control error is determined as

where —set temperature, —measured temperature corresponding to k-th sampling.

The PID controller is implemented as a discrete algorithm (using a ready-made library similar to the AlexGyver PID implementation):

where I(k) is the integral component, D(k) is the differential component, u(k) is the control action, —sampling period, and , , —adjustable controller coefficients. The control signal u(k) is normalised in the range [0, 1] and sets the PWM duty cycle of the heater.

The following controller parameter values, selected experimentally, were used: , , . With these values, the settling time did not exceed 15 s, overshoot was no more than 5%, and the static temperature error in the operating range was around 3–4 °C, which is acceptable for the application in question.

Let us also consider the issue of ensuring uninterrupted power supply on the 3.3 V bus, which powers the ESP32, MLX90614 and BQ27441 modules. An AMS1117-3.3 linear regulator is used. The maximum total load current is estimated as:

Imax = IESP32,max + IMLX90614 + IBQ27441

Based on passport ratings and literature data:

- -

- ESP32 (Wi-Fi in transmission mode, peak): IESP32,max ≈ 240 mA;

- -

- MLX90614: IMLX90614 ≈ 1.5 mA;

- -

- BQ27441 (if powered from 3.3 V): IBQ27441 ≈ 0.093 mA.

Hence, in the worst case scenario,

Imax ≈ 0.24 A.

The AMS1117-3.3 regulator is rated for an output current of up to 1 A, i.e., it is used at about 24% of its rated capacity, with a fourfold current margin.

At an input voltage Vin = 7.4 V and an output Vout = 3.3 V, the voltage drop across the stabiliser ΔV = Vin − Vout = 4.1 V, and the power dissipation at maximum load: Pdiss ≈ 4.1 × 0.24 ≈ 0.98 W.

For the SOT-223 package, this provides a temperature rise of about 40–45 °C relative to the environment, which is significantly below the thermal protection limits and the maximum allowable temperature. Thus, the regulator operates with a current and temperature margin and provides a continuous 3.3 V power supply.

The 3.3 V bus after the AMS1117 does not contain any breakout keys; all microcircuits are permanently connected to the same bus. This combination ensures uninterrupted power supply and stable operation even with dynamic currents associated with the activation of the ESP32 radio path.

The printed circuit board on which the aroma diffuser control circuit is assembled is shown in Figure 6.

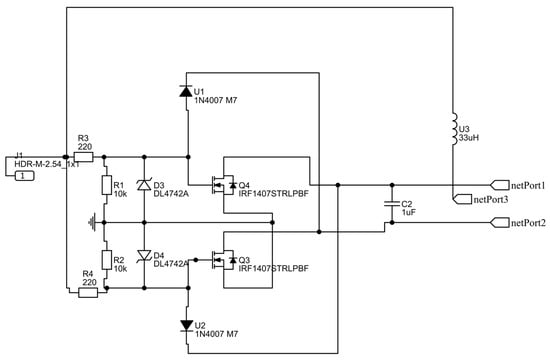

The second board (the circuit is shown in Figure 7) is designed as a fully autonomous power unit: two MOSFET transistors Q3 and Q4 form a half-bridge, their gates are cross-controlled via a push-pull driver divider on elements R1, R2, D3 and D4, which guarantees switching in zero voltage modes and minimises switching losses, and an LC circuit is connected to the output of the half-bridge—capacitor C2 and inductance coil L, tuned to a resonant frequency that allows the creation of a high-frequency current of the required amplitude for effective induction heating of the workpiece.

Figure 7.

Electronic diagram of an induction heater of the proposed type of air freshener.

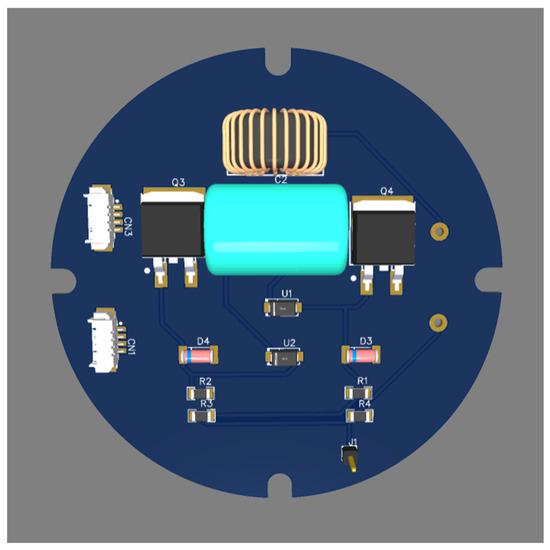

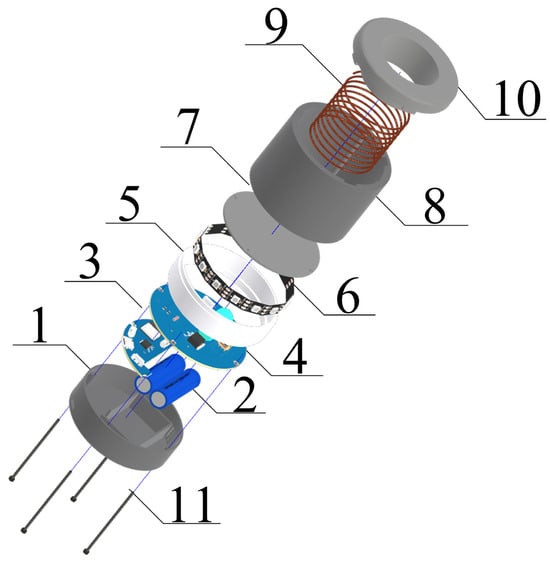

The circuit diagram of the induction heater printed circuit board is shown in Figure 8. The assembly diagram of the aromatiser is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Printed circuit board of an induction heater.

Figure 9.

Fragrance assembly diagram: 1—lower part of the housing; 2—batteries; 3—control unit; 4—induction heater board; 5—light diffuser; 6—LED strip; 7—inner cover of the housing; 8—main body of the housing; 9—induction heater coil; 10—upper cover of the housing; 11—screws for fastening the parts of the housing.

3.2. Test Results

A series of calorimetric experiments was conducted to preliminarily assess the efficiency and transmitted heat power. A sample of aluminium foil with a mass of m = 2 g was used. Under fixed heating conditions, the sample temperature increased by ΔT ≈ 30 °K over Δt = 52 s. Assuming a specific heat capacity of c ≈ 900 J/(kg·K), we obtain:

Q = m·c·ΔT = 0.002·900·30 = 54 J,

Pout = Q/Δt ≈ 54/52 ≈ 1.0 W.

At the same time, the input power in the same mode was Pin ≈ 4.54 W. The efficiency estimate is therefore

η ≈ Pout/Pin ≈ 1.0/4.54 ≈ 23%.

Thus, the efficiency of the proposed device is relatively low, but this is compensated by the possibility of using cartridges of various designs that utilise metal foil. In particular, there is a variant in which the composition used was placed in a conductive foil shell. This variant is convenient in many ways from the point of view of mass production of disposable cartridges. Along with it, a variant can also be used in which the initial raw material containing an aromatic component is mixed with metal particles (metal filings, foil shavings, etc.), which are also capable of providing heating through interaction with a high-frequency field. Both of these variants were tested during the tests.

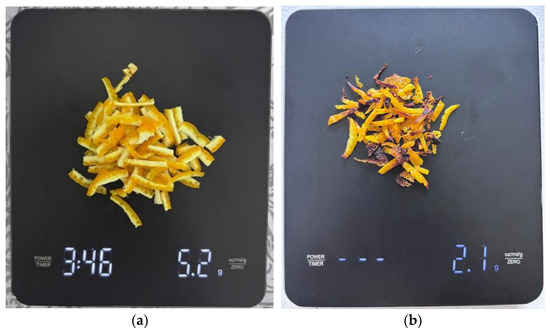

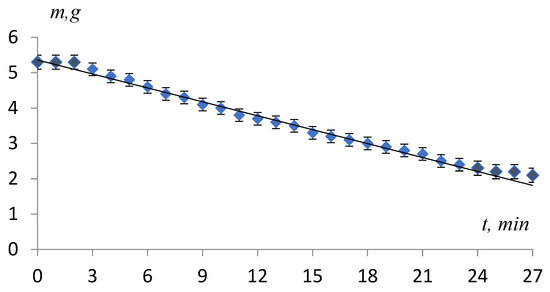

Let us consider the second one. The tests used a composite material consisting of a mixture of chopped orange peel and chopped metal foil. Figure 10 shows photographs of this composite before and after heating in a high-frequency field (the equipment described in Section 2 was used to monitor changes in the mass of the composite). The dependence of the composite mass on time is shown in Figure 11. This dependence was obtained under the following experimental conditions. Pre-prepared pieces of orange peel were mixed with finely chopped pieces of aluminium foil and placed in a glass test tube. The test tube was placed inside the induction coil of the heater, and the entire assembly was placed on the platform of an electronic balance. The mixture was heated to 75 °C and maintained at this temperature for 26 min, with the temperature controlled by an IR sensor via feedback.

Figure 10.

Photograph of the initial composite containing shredded orange peel and shredded aluminium foil; (a) before heating; (b) after heating.

Figure 11.

Dependence of composite mass on heating time .

The photographs in Figure 10 clearly show that there is a change in the volume of the composite due to moisture evaporation, which is also accompanied by the evaporation of volatile aromatic substances. More precisely, the evaporation of the entire complex of substances contained, for example, in orange peel automatically ensures the release of substances that provide aromatisation. This is also evidenced by the immediate perception of the smell by any consumer. For household aromatisation, nothing more is required. Figure 11 confirms that this process can take place under conditions close to the standards established for household appliances of a similar purpose. Figure 11 also shows that there is a section where the dependence of the composite mass on time is linear, which greatly simplifies calculations.

The illustrative experiment thus confirms the expected result. Any plant material, including those containing aromatic components, can be heated by a high-frequency electromagnetic field through contact with metal elements. The nature of these elements (outer shell or metal particles mixed with the raw material) is secondary, as it only determines the heating mode.

An additional experiment was also conducted to evaluate efficiency in operating mode. Orange peel (mass 3 g) wrapped in aluminium foil (mass 0.6 g) was used. The sample was heated from an initial temperature Tstart = 32.5 °C to a final temperature Tend = 70.3 °C. The heating time was 5.14 min. The measured value of the current in the empty coil I0 was 0.73 A, and the value of the current I1 when the peel wrapped in foil was placed in the coil was 0.80 A. The supply voltage was 7.4 V, as before. The following heat capacity values were used in the calculations: cAl ≈ 900 J/kg.K for foil and c1 ≈ 3800 J/kg for peel. The latter value was chosen based on analogy with moistened biotissue. Calculations performed using the standard method with the above parameters give the following value for the power input to the sample: Pout ≈1.46 W. The power consumed by the coil is Pin ≈ 5.39 W. Therefore, the efficiency of the device under consideration is approximately 25%.

4. Discussion

The proposed approach, at a minimum, allows for a significant expansion of the range of plant raw materials used for domestic room fragrancing and in aromatherapy.

Existing products intended for aromatisation, including those used in the home, are based on fairly complex technological processes involved in obtaining refined aromatic oils (the list of such oils is essentially identical to that used in aromatherapy [18,19]). From the end consumer’s point of view, this is unnecessary. The aromatic component can be obtained directly from the raw plant material—especially if the consumer is only interested in room fragrancing.

Expanding the range of raw plant materials, in turn, allows for a significant expansion of the possibilities of aromatherapy, which are currently largely limited to industrially produced essential oils [18,19]. The most controversial issue from the point of view of using the proposed design for aromatherapy (with a focus on the direct use of natural plant raw materials) is the question of its inherent technological variation, which can be quite significant. However, this problem can also be solved by software means, since the aroma diffuser is controlled via the user’s smartphone or iPhone. Feedback for solving this problem can be implemented in the future, for example, using diagnostics of the gas flow formed when the composition used is heated, based on dielectric permeability. Sensors measuring dielectric permeability at different frequencies [54] are capable of providing sufficiently detailed information about variations in the composition of the gas phase caused by technological variation in the raw materials. This creates an opportunity to integrate the proposed approach with the concept of the IoT, as well as with the concept of the smart house. It is worth emphasising that this concept is focused on a very wide range of different technologies aimed at maximising resource savings [56,57] and improving the comfort of housing, including taking into account the psychological characteristics of consumers [58,59]. The effect of aromatic oils on the psychophysiological state of the user is fully consistent with the solution of such tasks [31].

It should be noted, however, that in order to use the proposed design, it is not strictly necessary to focus on the direct use of natural plant raw materials in accordance with the method described above. The proposed design itself only ensures the evaporation of aromatic components from the cartridge, which can be manufactured using any suitable technology. In particular, it is possible to use a cartridge in which a particular sorbent is saturated with industrially produced aromatic oil and mixed with conductive particles.

Thus, there are two extreme cases. In the first, natural plant raw materials undergo only minimal processing. In the second, industrially produced essential (aromatic) oils are still used. Between these two extreme cases, there is a very wide range of different options, focused, for example, on natural hydrolates.

Natural hydrolate is a product obtained by steam distillation during the processing of essential oil raw materials. It contains water-soluble biologically active substances and essential oils that have a multifaceted healing effect on the body [60,61]. The essential oils contained in natural hydrolates stabilise the product and allow it to retain its quality and healing properties for 1–2 years when stored under the right conditions [62]. It is important that the essential oils contained in hydrolates are in the form of a suspension due to their extremely fine dispersion; therefore, they do not form films and easily pass through mucous membranes, skin, etc. [63]. Experience with hydrolates shows that they rarely cause allergic reactions, unlike essential oils, and are not toxic even in high concentrations [64].

The use of natural hydrolates and similar products allows for a fairly wide range of designs for disposable cartridges saturated with aromatic components. For example, there is a variant that uses a ‘dry’ cartridge, which is activated by moistening. Such a cartridge can be implemented, for example, on the basis of highly swelling polymer hydrogels. Such gels have been actively researched in recent decades [65,66,67]. A distinctive property of hydrogels is their ability to absorb up to 1000 grams of liquid per gram of dry matter [68]. It has also been proven that it is possible to obtain such materials with predetermined properties, up to the possibility of implementing neuromorphic materials [69,70]. This makes it possible to create a hydrophobic-hydrophilic environment using a dried gel saturated with substances such as natural hydrolates, followed by saturation of the cartridge with water immediately before use. This approach also allows the use of additional stimuli to separate the aromatic component from the hydrophobic-hydrophilic polymer matrix, for example, electric current [71,72].

There is a wide class of polymer hydrogels that undergo phase transitions close to abrupt ones [73,74], and the nature of such transitions can vary due to the formation of complexes between linear macromolecules and cross-linked networks [75,76,77]. The abrupt nature of the change in the characteristics of hydrogels saturated with aromatic components makes it possible to significantly modernise the proposed type of fragrance. In particular, various colour-music devices are well known [78,79]. When sufficiently high rates of separation of the aromatic component from the polymer matrix are achieved, it becomes possible to implement similar devices in which a complex symphony based on the harmony of colour, aroma and music is realised. Such systems can serve not only for entertainment, but are also of interest from the point of view of correcting the psychophysiological state of users [80,81].

Manipulation of polymer matrices containing aromatic components is also of interest in terms of developing neuromorphic materials for various purposes. Such materials have been actively developed recently [82,83], but, as noted in [84], there is a problem with their practical implementation. At this stage of research, computing systems based on such materials cannot compete with computers based on classical electronic components that follow binary logic. Consequently, the development of simple systems in which neuromorphic materials can demonstrate their inherent advantages is a pressing issue [84]. To manipulate polymer matrices based on polymer hydrogels, it may be possible in the future to use the properties that form the basis for the synthesis of organic electronic components [85,86] used for neuromorphic materials, which are characterised by great diversity [87]. In this case, a polymer matrix saturated with aromatic components can itself serve as part of an electronic circuit used, for example, to correct the psychophysiological state of users. At the same time, there is no need to provide complex electrical contact with the base part of the circuit (which can lead to the appearance of parasitic electrolytic processes), since it is possible to use, for example, optoelectronic communication [88,89].

From the point of view of the current situation in countries such as Kazakhstan, the development of devices such as the one proposed in this work is of interest in another respect. Namely, Kazakhstani chemical schools have currently developed a whole range of new functional polymer materials [90]. However, their implementation in practice is hampered by economic factors. The implementation of devices such as the one proposed in this work creates an opportunity for the implementation of new polymer materials as well. The most significant factor here is the relatively small production volumes, which allow the use of products from experimental production facilities.

5. Conclusions

A new type of air freshener design has been proposed, based on the release of volatile substances from virtually any type of composite containing electrically conductive inclusions under the influence of high-frequency electromagnetic fields. This design allows for the implementation of both household air fresheners and aromatherapy equipment. Such composites can be either direct mixtures of plant raw materials with metal inclusions or innovative polymer matrices based on polymer hydrogels or other promising materials.

It has been shown that further research in polymer science aimed at using high-frequency electromagnetic fields for the controlled release of volatile substances from polymer composites and hydrogels is of interest. Such materials can serve as the basis for the creation of innovative controlled aromatisation systems and functional coatings, as well as find applications in related fields of petrochemistry and polymer raw material processing. The implementation of the developed approaches opens up new opportunities in the formation of technological solutions, providing a link between fundamental research and practical industrial tasks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K., P.G., G.S., E.D. and I.S.; Formal analysis, E.K., G.S., E.D. and I.S.; Funding acquisition, G.S.; Investigation, K.K., E.D. and I.S.; Methodology, E.K., P.G., G.S., E.D. and I.S.; Project administration, G.S.; Resources, K.K. and I.S.; Software, K.K. and I.S.; Supervision, G.S.; Validation, K.K. and I.S.; Visualization, K.K. and I.S.; Writing—original draft, E.K., K.K., P.G., G.S., E.D. and I.S.; Writing—review and editing, E.K., E.D. and I.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR24992883).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Farrar, A.J.; Farrar, F.C. Clinical Aromatherapy. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 55, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhan, S.E.; Sheafer, H.; Tepper, D. The Effectiveness of Aromatherapy in Reducing Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Res. Treat. 2016, 2016, 8158693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, B.; Ernst, E. Aromatherapy: A systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2000, 50, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farahani, M.A.; Afsargharehbagh, R.; Marandi, F.; Moradi, M.; Hashemi, S.M.; Moghadam, M.P.; Balouchi, A. Effect of aromatherapy on cancer complications: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 47, 102169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouya, S.; Ahmadidarehsima, S.; Badakhsh, M.; Balouchi, A. Effect of aromatherapy interventions on hemodialysis complications: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2018, 32, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Vidaña, D.I.; Ngai, S.P.C.; He, W.; Chow, J.K.W.; Lau, B.W.M.; Tsang, H.W.H. The effectiveness of aromatherapy for depressive symptoms: A systematic review. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 5869315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, N.N.; Campanelli, S.E.; da Silva, C.R.; da Silva França, R.C.; de Sousa Rosso, I.C.A. Psychological and neurophysiological effects of inhaled aromatherapy. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babakhanian, M.; Ghazanfarpour, M.; Kargarfard, L.; Roozbeh, N.; Darvish, L.; Khadivzadeh, T.; Dizavandi, F.R. Effect of aromatherapy on the treatment of psychological symptoms in postmenopausal and elderly women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Menopausal Med. 2018, 24, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, E.; Samancioglu, S.; Ozden, D.; Bakir, E. Effects of aromatherapy on sleep quality and anxiety of patients. Nurs. Crit. Care 2017, 22, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genç, F.; Karadağ, S.; Akça, N.K.; Tan, M.; Cerit, D. The effect of aromatherapy on sleep quality and fatigue level of the elderly: A randomized controlled study. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 34, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.X.J.; Cai, J.S.; Ignacio, J. Effectiveness of aromatherapy on anxiety and sleep quality among adult patients admitted into intensive care units: A systematic review. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 76, 103396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barati, F.; Nasiri, A.; Akbari, N.; Sharifzadeh, G. The effect of aromatherapy on anxiety in patients. Nephrourol. Mon. 2016, 8, e38347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.K.; Lim, S.; Song, J.A.; Kim, M.E.; Hur, M.H. The effects of aromatherapy essential oil inhalation on stress, sleep quality and immunity in healthy adults: Randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 12, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.C.; Fang, S.H.; Fang, L. The effects of aromatherapy in relieving symptoms related to job stress among nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2015, 21, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, C.; Nakagawa, S.; Hirata, N.; Ohta, S.; Shimoeda, S. Evaluating the effect of aromatherapy on a stress marker in healthy subjects. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2019, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Al-Wabel, N.A.; Shams, S.; Ahamad, A.; Khan, S.A.; Anwar, F. Essential oils used in aromatherapy: A systemic review. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M. Aromatherapy and methods of applying essential oils. Arch. Physiother. Glob. Res. 2018, 22, 25–31. Available online: https://publisherspanel.com/api/files/view/2330861.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Liang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chi, P.; Liu, H.; Jing, Z.; Cao, H.; Du, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, X.; Zhang, W.; et al. Essential oils: Chemical constituents, potential neuropharmacological effects and aromatherapy—A review. Pharmacol. Res.-Mod. Chin. Med. 2023, 6, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, L.K.; Gholap, A.D.; Hatvate, N.T.; Naren, P.; Khan, S.; Chavda, V.P.; Balar, P.C.; Gandhi, J.; Khatri, D.K. Essential oils for clinical aromatherapy: A comprehensive review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 330, 118180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, D.P.; Damasceno, R.O.S.; Amorati, R.; Elshabrawy, H.A.; de Castro, R.D.; Bezerra, D.P.; Nunes, V.R.V.; Gomes, R.C.; Lima, T.C. Essential Oils: Chemistry and Pharmacological Activities. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikmoradi, A.; Seifi, Z.; Poorolajal, J.; Araghchian, M.; Safiaryan, R.; Oshvandi, K. Effect of inhalation aromatherapy with lavender essential oil on stress and vital signs in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: A single-blinded randomized clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifi, Z.; Bikmoradi, A.; Bazrafshan, M.R.; Poorolajal, J.; Araghchian, M.; Kashfi, S.H.; Kavi, E.; Jokar, M. The Effect of Inhalation Aromatherapy with Lavender Essential oil on Pain Severity of Patients After Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery: A Single-blind Randomised Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiskaramian, A.; Gholami, M.; Yarahmadi, S.; Baharvand, P.A.; Birjandi, M. Effect of aromatherapy with Melissa essential oil on stress and hemodynamic parameters in acute coronary syndrome patients: A clinical trial in the emergency department. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 44, 101436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, E.; Kuchta, K.; Kimura, M.; Rauwald, H.W.; Kamei, T.; Imanishi, J. Effects of bergamot (Citrus bergamia (Risso) Wright & Arn.) essential oil aromatherapy on mood states, parasympathetic nervous system activity, and salivary cortisol levels in 41 healthy females. Forsch. Komplementärmedizin/Res. Complement. Med. 2015, 22, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, N.; Abootalebi, M.; Jamalimoghadam, N.; Kasraeian, M.; Emamghoreishi, M.; Akbarzadeh, M. Investigation of the effect of aromatherapy with Citrus aurantium blossom essential oil on premenstrual syndrome in university students: A clinical trial study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2018, 32, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Sebghatollahi, Z.; Kamal, M.; Dhyani, A.; Shrivastava, A.; Singh, K.K.; Sinha, M.; Mahato, N.; Mishra, A.K.; Baek, K.H. Citrus essential oils in aromatherapy: Therapeutic effects and mechanisms. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gok Metin, Z.; Arikan Donmez, A.; Izgu, N.; Ozdemir, L.; Arslan, I.E. Aromatherapy massage for neuropathic pain and quality of life in diabetic patients. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2017, 49, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyed-Rasooli, A.; Salehi, F.; Mohammadpoorasl, A.; Goljaryan, S.; Seyyedi, Z.; Thomson, B. Comparing the effects of aromatherapy massage and inhalation aromatherapy on anxiety and pain in burn patients: A single-blind randomized clinical trial. Burns 2016, 42, 1774–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedigan, F.; Sheridan, H.; Sasse, A. Benefit of inhalation aromatherapy as a complementary treatment for stress and anxiety in a clinical setting–A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2023, 52, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aćimović, M. Essential oils: Inhalation aromatherapy—A comprehensive review. J. Agron. Technol. Eng. Manag. 2021, 4, 547–557. [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara, Y.; Shigetho, A.; Yoneda, M.; Tuchiya, T.; Yamada, H.; Matumura, T.; Hirano, M. Versatile psychophysiological potencies of essential oils, when seen as a function of behavioral task assigned to the participants after inhalation. Int’l J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2015, 3, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.; Pino, J.A.; Rodríguez, A.; Rodríguez, M. Volatile compounds in commercial air fresheners: A comparative study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 30239–30247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A. Fragranced consumer products: Exposures and effects from emissions. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. 2016, 9, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.M.; Waring, M.S.; DeCarlo, P.F. Real-time transformation of outdoor aerosol components upon transport indoors measured with aerosol mass spectrometry. Indoor Air 2016, 27, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangaleela, S.; Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Kesika, P.; Bharathi, M.; Kunaviktikul, W.; Klunklin, A.; Chanthapoon, C.; Chaiyasut, C. Essential oils, phytoncides, aromachology, and aromatherapy—A review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, I.; Parmar, V.M.; Mandavgane, S.A. Current trends in essential oil (EO) production. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 15311–15334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, Z.A.A.; Ahmad, A.; Setapar, S.H.M.; Karakucuk, A.; Azim, M.M.; Lokhat, D.; Rafatullah, M.; Ganash, M.; Kamal, M.A.; Ashraf, G.M. Essential oils: Extraction techniques, pharmaceutical and therapeutic potential-a review. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018, 19, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimenov, I.; Kadyrzhan, K.; Kabdushev, S.; Bakirov, A.; Kopishev, E. New Equipment for Aromatherapy and Related Mobile App: A Tool to Support Small Peasant Farms in Kazakhstan in Crisis. In Robotics, Machinery and Engineering Technology for Precision Agriculture. In Robotics, Machinery and Engineering Technology for Precision Agriculture: Proceedings of XIV International Scientific Conference “INTERAGROMASH 2021”; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip Morris Products S.A. Aerosol Generating Device That Adapts to the Surrounding Air. South Korea Patent No. 89173, A24F40/48, 20 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Blandino, T.P.; Wilke, A.P.; Frater, J.J.; Paprocki, B.J. Article for Use with Apparatus for Heating Smokable Material. European Patent Patent No. 3367830B1, A24F 47/00, 7 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Horikoshi, S.; Catalá-Civera, J.M.; Schiffmann, R.F.; Fukushima, J.; Mitani, T.; Serpone, N. Microwave Chemical and Materials Processing; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, E. Application of microwave heating in polymer synthesis: A review. Results Chem. 2023, 6, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Talreja, S. Green chemistry and microwave irradiation technique: A review. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2022, 34, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Mu, R.; Li, G.; Li, M.; Lv, W. Research progress in fluid and semifluid microwave heating technology in food processing. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3436–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hay, M.M. 5—Principles of microwave heating for the food industry. Emerg. Therm. Process. Food Ind. 2023, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, P.; Kulawik, P.; Zając, M.; Migdał, W. Microwave applications in the food industry: An overview of recent developments. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 7989–8008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, N.K.; Lai, Q.D.; Le, T.K.P.; Le, N.T. Influences of AC frequency and electric field strength on changes in bioactive compounds in Ohmic heating of pomelo juice. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 72, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, M.; Du, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Ling, B. Recent advances in food processing by radio frequency heating techniques: A review of equipment aspects. J. Food Eng. 2023, 357, 111609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabdushev, S.; Kadyrzhan, K.; Vitulyova, Y.; Bakirov, A.; Yevstifeyev, V.; Suleimenov, I. Means of aromatherapy of mass use as a tool for correcting the psychophysiological state of society. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Robotics, Automation and Artificial Intelligence (RAAI), Singapore, 9–11 December 2022; pp. 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kong, M.; Jung, S.; Jeoung, J.; Kang, H.; Hong, T. Technological applications of social robots to create healthy and comfortable smart home environments. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, N.U.; Ahmed, I.; Adnan, M.; Ali, M.; Naeem, F. Experts and intelligent systems for smart homes’ transformation to sustainable smart cities: A comprehensive review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Han, J. Smart home advancements for health care and beyond: Systematic review of two decades of user-centric innovation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e62793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimenov, I.E.; Kabdushev, S.B.; Kadyrzhan, K.; Shaltikova, D.B.; Moldakhan, I. New technologies for measuring viscosity: Using mobile applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Computer and Technology Applications, Antalya, Turkey, 14–16 April 2020; pp. 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimenov, I.E.; Mun, G.A.; Kabdushev, S.B.; Alikulov, A.; Shaltykova, D.B.; Moldakhan, I. The design of viscometer with smartphone controlling. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2022, 27, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, G.A.; Suleimenov, I.E.; Kabdushev, S.B.; Baipakbayeva, S.T.; Kadyrzhan, K.N.; Yegemberdiyeva, Z.; Grigoryev, P.E.; Konshin, S.V.; Sergeyevna, V.Y. Fragrance Device (35745). RSE «National Institute of Intellectual Property». 2022. Available online: www.kazpatent.kz (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Salthammer, T.; Gu, J.; Wientzek, S.; Harrington, R.; Thomann, S. Measurement and Evaluation of Gaseous and Particu-late Emissions from Burning Scented and Unscented Candles. Environ. Int. 2021, 155, 106590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimenov, I.; Egemberdieva, Z.; Bakirov, A.; Baipakbayeva, S.; Kopishev, E.; Mun, G. Efficiency Problem of renewable energetics systems in the context of «smart house» concept. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 164, 13002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuldna, P.; Peterson, K.; Kuhi-Thalfeldt, R. Knowledge brokering on emissions modelling in Strategic Environmental Assessment of Estonian energy policy with special reference to the LEAP model. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 54, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Hong, S.-H.; Bong, C.-K.; Cho, M.-H. Characterization of air freshener emission: The potential health effects. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 40, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, C.A.; Sousa, A.C.A.; Caramelo, D.; Delgado, F.; de Oliveira, A.P.; Pastorinho, M.R. Chemical profile and eco-safety evaluation of essential oils and hydrolates from Cistus ladanifer, Helichrysum italicum, Ocimum basilicum and Thymbra capitata. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 175, 114232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruas, A.; Graça, A.; Marto, J.; Gonçalves, L.; Oliveira, A.; da Silva, A.N.; Pimentel, M.; Moura, A.M.; Serra, A.T.; Figueiredo, A.C.; et al. Chemical Characterization and Bioactivity of Commercial Essential Oils and Hydrolates Obtained from Portuguese Forest Logging and Thinning. Molecules 2022, 27, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aćimović, M.; Tešević, V.; Smiljanić, K.; Cvetković, M.; Stanković, J.; Kiprovski, B.; Sikora, V. Hydrolates: By-products of essential oil distillation: Chemical composition, biological activity and potential uses. Adv. Technol. 2020, 9, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, C.S.; Gameiro, J.A.; Roseiro, L.B.; Figueiredo, A.C. Hydrolates: A review on their volatiles composition, biological properties and potential uses. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 1661–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiljanić, K.; Prodić, I.; Trifunovic, S.; Krstić Ristivojević, M.; Aćimović, M.; Stanković Jeremić, J.; Lončar, B.; Tešević, V. Multistep Approach Points to Compounds Responsible for the Biological Activity and Safety of Hydrolates from Nine Lamiaceae Medicinal Plants on Human Skin Fibroblasts. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Das, S.; Nandi, A.K. A review on recent advances in polymer and peptide hydrogels. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 1404–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoun, E.A.; Kenawy, E.-R.S.; Chen, X. A review on polymeric hydrogel membranes for wound dressing applications: PVA-based hydrogel dressings. J. Adv. Res. 2017, 8, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimenov, I.E.; Guven, O.; Mun, G.A.; Uzun, C.; Gabrielyan, O.A.; Kabdushev, S.B.; Agibaeva, L.; Nurtazin, A. Hysteresis Effects During the Phase Transition in Solutions of Temperature Sensitive Polymers. Eurasian Chem. J. 2017, 19, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laftah, W.A.; Hashim, S.; Ibrahim, A.N. Polymer Hydrogels: A Review. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2011, 50, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hao, S.; Dkhil, B.; Tian, B.; Duan, C. Ferroelectric materials for neuroinspired computing applications. Fundam. Res. 2024, 4, 1272–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, W.; Zeng, J.; Fan, F.; Gu, J.; Chen, X.; Yan, L.; Xie, G.; Liu, S.; Yan, Q.; et al. 90% yield production of polymer nano-memristor for in-memory computing. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanjai; Sinha, A.; Kalambate, P.K.; Mugo, S.M.; Kamau, P.; Chen, J.; Jain, R. Polymer hydrogel interfaces in electrochemical sensing strategies: A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 118, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budtova, T.; Suleimenov, I.; Frenkel, S. Electrokinetics of the contraction of a polyelectrolyte hydrogel under the influence of constant electric current. Polym. Gels Netw. 1995, 3, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Liao, B.; Zhao, K.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, L. Review of the Perspectives and Study of Thermo-Responsive Polymer Gels and Applications in Oil-Based Drilling Fluids. Gels 2023, 9, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, H. Studies on the phase transition of hydrogels and aqueous solutions of thermosensitive polymers. Polym. J. 2018, 50, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoskoltseva, O.A.; Chernikova, E.V.; Rogacheva, V.B.; Zezin, A.B. Competitive interactions in hydrogel-interpolyelectrolyte complex systems. Polym. Sci. Ser. B 2015, 57, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelmanovich, S.G.; Parke-Houben, R.; Frank, C.W. Competitive swelling forces and interpolymer complexation in pH- and temperature-sensitive interpenetrating network hydrogels. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurkeeva, Z.S.; Mun, G.A.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V.; Kan, V.A.; Shaikhutdinov, E.M. Interpolymer Complex Formation Between Linear and Crosslinked Poly(acrylic acid) and Poly(vinyl ether of ethyleneglycol). Eurasian Chem. J. 2000, 2, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, K. Instruments to Perform Color-Music: Two Centuries of Technological Experimentation. Leonardo 1988, 21, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C.; Di Stefano, N. Coloured hearing, colour music, colour organs, and the search for perceptually meaningful correspondences between colour and sound. Iperception 2022, 13, 20416695221092802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, A.; Collis, C.; Nitins, T.; Ryan, M.; Harrington, S.; Duncan, B.; Carter, J.; Luck, E.; Neale, L.; Butler, D.; et al. Defining entertainment: An approach. Creat. Ind. J. 2014, 7, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.H.; Kim, S. Research trends in entertainment robots: A comprehensive review of the literature from 1998 to 2024. Digit. Bus. 2025, 5, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumyusenge, A.; Melianas, A.; Keene, S.T.; Salleo, A. Materials Strategies for Organic Neuromorphic Devices. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2021, 51, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, F.; Basaran, A.C.; Schuller, I.K. Thermal Management in Neuromorphic Materials, Devices, and Networks. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2205098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimenov, I.; Gabrielyan, O.; Kopishev, E.; Kadyrzhan, A.; Bakirov, A.; Vitulyova, Y. Advanced Applications of Polymer Hydrogels in Electronics and Signal Processing. Gels 2024, 10, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, V.; Ingebrandt, S. Biologically sensitive field-effect transistors: From ISFETs to NanoFETs. Essays Biochem. 2016, 60, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Koutsouras, D.A.; Kazemzadeh, S.; van de Burgt, Y.; Yan, F.; Gkoupidenis, P. Electrolyte-gated transistors for synaptic electronics, neuromorphic computing, and adaptable biointerfacing. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauhausen, I.; Coen, C.; Spolaor, S.; Gkoupidenis, P.; van de Burgt, Y. Brain-Inspired Organic Electronics: Merging Neuromorphic Computing and Bioelectronics Using Conductive Polymers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2307729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, S.; Huang, W.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, W. Wearable in-sensor reservoir computing using optoelectronic polymers with through-space charge-transport characteristics for multi-task learning. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Kim, J.; Kwon, S.M.; Jo, J.; Park, S.K.; Kim, Y. Recent Progress of Optoelectronic and All-Optical Neuromorphic Devices: A Comprehensive Review of Device Structures, Materials, and Applications. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2000119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidullayeva, A.K.; Tuleyeva, R.N.; Mussalimova, M.; Taubatyrova, A.; Toleutay, G.; Bektenov, N.A. Sustainable Dynamic Polymer Networks for Packaging: Development and Prospects of Bio-Based Vitrimers. Chem. J. Kazakhstan 2025, 4, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).