Abstract

Power converters are essential for solar energy systems but achieving over 96% efficiency at 1 kW and 300 kHz with compact magnetic and EMC compliance remains challenging for high-power-density PV applications. This study presents the design, modeling, and experimental validation of a 1 kW two-phase interleaved boost converter operating from 12 V input to 48 V/20 A output, featuring a single EE32 Litz-wound coupled-core inductor with coupling coefficient k = −0.475 that reduces per-phase current ripple to just 120 mA (0.6% relative) at full load, a load-selective active zero-current switching (ZCS) circuit activated above 5 A threshold via DCR sensing to minimize switching losses without light-load penalties, and digital peak-current control with 2P2Z compensator implemented on an XMC4200 microcontroller, ensuring robust stability. Experimental results demonstrate peak efficiency of 98.6% at approximately 190 W load, full-load efficiency of approximately 96% with total losses limited to 40 W dominated by conduction rather than switching, thermal rise below 80 °C on key components, voltage regulation with less than 1% deviation down to 2 A minimum load, and full compliance with electromagnetic compatibility standards, including EN 55014-1/2 and EN 61000-4-2 ESD testing. The novel integration of selective ZCS, single-core magnetic, and high-frequency operation outperforms prior interleaved boost converters, which typically achieve 94–97% peak efficiency at lower switching frequencies of 20–100 kHz using multiple inductors or complex always-active resonant networks, making this solution particularly suitable for compact photovoltaic micro-converters, electric vehicles, and industrial power supplies requiring high efficiency, reliability, and regulatory compliance.

1. Introduction

A primary concern in the study of solar system integration pertains to the spatial demands of the solar control system itself. Despite the presence of wiring management and storage mechanisms, the performance of the converter is evaluated based on its resilience and dependability. This approach aligns with market demands that emphasize safety and efficiency standards to ensure end-user security [1,2]. As is well known, transformers come in different types, which can be divided into DC converters [3] and AC converters [4]. The converters rating plays a crucial role in the operational performance of power systems, especially photovoltaic (PV) systems; the higher the converter rating is, the better the operational performance is, and the higher the resulting output is [5].

1.1. Current Challenges and Research Gap in the Existing Literature

Digital power supplies have found extensive use across a broad spectrum of applications, thereby demonstrating their versatility and widespread adoption. Consequently, the significance of high-power density and low-noise power sources cannot be overstated in ensuring optimal performance and efficiency [6]. Power converters play a crucial role in solar energy systems and a wide range of electrical applications. A variety of converter types are employed in this regard, including AC-DC [7], DC-AC [8], AC-AC [9], and DC-DC converters [10]. Furthermore, multilevel converter topologies offer significant advantages in power electronics, including higher voltage levels, reduced voltage stress on switching devices, an improved power factor, lower power losses, and smaller filter requirements [11,12]. Consequently, a plethora of advancements and enhancements have been proposed for this specific topology, garnering interest from both the industrial and academic sectors. This exemplifies the continuous evolution and refinement of digital power supplies to address the shifting requirements of diverse industries and research domains. The topology of the DC-DC interleaved converter technique has found wide application in scenarios that necessitate high-density power and thermal distribution. This technique has been particularly successful in compact high-power systems, including electric vehicle charging units, power walls, central processing unit power supplies, and 5G network servers, as outlined in [13]. Article [14] proposes a new design for a DC-DC converter specifically aimed at renewable energy applications (e.g., solar power or other low-voltage sources). In the proposed design, interference and a switching capacitor cell (dual-capacitor multiplier) are combined to produce a high step-up voltage gain without the need for a transformer or long duty cycle. A key advantage of this topology is that the input current becomes essentially ripple-free, reducing conduction losses and electromagnetic interference (EMI). Also, due to the lower output amplitude requirements, the transformer can be built with smaller components (and therefore cheaper and more compact). Another advantage highlighted is that the voltage stress on the switching elements (switches, diodes) remains low, allowing the use of low-resistance switches; this reduces losses and increases efficiency. In general, simulation results were presented that validate the performance of the proposed converter, showing that the designed architecture achieves high profitability, low stress on components, reduced size and cost, and suitable input current characteristics, making this proposed solution a promising solution for energy conversion from renewable energy. The completed article in [15] presents a new DC-DC converter topology designed for renewable energy systems and electric vehicles that need to efficiently step up a relatively low input voltage. In this proposed design, a dual-input architecture (i.e., the converter can accept two different DC sources), a voltage multiplier cell/diode multiplier, and a capacitor are combined to achieve high-voltage gain while using fewer semiconductor switches. This proposed design simplifies the number of switches required in the circuit, reduces cost and complexity, and helps to reduce voltage stress on switching devices. To demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed design, the authors developed a real-world hardware prototype and validated it in a “hardware-in-the-loop” setup using a real-time simulator (OPAL-RT OP5700), confirming that the converter can deliver high gain with good efficiency—approximately 97.09% under tested duty cycle and power rating. The authors believe that this designed topology (dual input, high gain, low number of switches) is particularly suitable for applications such as hybrid renewable energy systems or electric vehicles, where multiple power sources (e.g., battery + solar) may be available and where high voltage enhancement, high efficiency, and minimal stress on components are required.

Additionally, the reduction in power losses in interleaved converters on their magnetic core and electronic power semiconductor can be significantly minimized [16].

Interleaved DC-DC converters have been shown to enhance efficiencies in PV systems by increasing voltage gain, reducing current stress, improving soft switching capabilities, and minimizing energy losses. These converters employ coupled inductors and voltage multiplier cells to achieve a substantial increase in voltage without necessitating high duty cycles [17,18]. The interleaved structure has been demonstrated to reduce current stress, resulting in a 16% increase in voltage gain compared to other topologies [19]. Moreover, it enhances efficiency by reducing conduction losses and elevating overall system performance [20]. The efficacy of interleaved DC-DC converters in optimizing power extraction from PV arrays is attributable to their adept management of voltage gain, current stress, and switching conditions [21]. In [22], the authors address the challenge of providing “pulsation loads”—loads that require rapid bursts of high power (peaking in fractions of a second) but with low average power—which are common in systems such as ship rectifiers or hybrid power sources. Under these pulsed load conditions, conventional rectifier and capacitor systems struggle to perform; large capacitors are usually needed to compensate for instantaneous power spikes, resulting in bulky and expensive designs. To solve this problem, the authors propose a bidirectional DC-DC converter, parallel and interleaved, that acts as a power pulse buffer (PPB). The designed control strategy combines model predictive control (MPC) with a Weinberger monitor whose gains are adaptively adjusted in real time using a gradient regression algorithm (based on the consistency of gradient trends), enabling the estimation and compensation of perturbations (such as parasitic coefficient effects or voltage ripple) that degrade accuracy. By analyzing the pulsed load current into intermediate and dynamic (pulsating) components, the PPB is controlled so that its input current follows the pulsating component, while a buffer capacitor absorbs the ripple energy. Meanwhile, the main power supply handles the intermediate current requirements. This separation enables the system to provide stable DC output and smooth three-phase AC under pulsed load while significantly reducing DC voltage ripple and AC current distortion. Simulations and experimental verification (according to the article) show that this integrated control and converter topology can effectively suppress excesses, improve current tracking accuracy, and maintain stable operation even under challenging, rapidly changing pulsed loads—without the need for massive capacitors and avoiding excessive strain on switching devices. In [23], the authors present a non-isolated, nested boost transformer topology that combines magnetic coupling (coupled inductors/transformer-like coils) with voltage multiplier cells to achieve a high boost from a low input voltage to a much higher output voltage—without the need for extreme duty cycles or bulky isolation transformers. Its design uses a transformer with two primary windings (connected to ensure equal impedance) to distribute the current evenly, along with several secondary windings and an inductor coupled to three windings. These transformers boost the output voltage and help stabilize the voltage across the switches and diodes, keeping these voltages well below the output voltage. One of the most important advantages of this system is its ease of installation and flexibility; the output voltage gain can be modified by changing the ratio of the magnetic windings, by adding more secondary windings, or by introducing additional voltage multiplier cells, which allows designers options to balance the gain, number of components, and efficiency. A 1 kW prototype (48 V input → 400 V output, with 25 kHz switching) was built and a measured efficiency of approximately 95.12% was demonstrated under full load conditions. In general, this transformer topology provides a compelling solution for high-power and high-step-up DC applications (e.g., PV solar power systems, battery-powered DC inverters, and small DC buses) where galvanized insulation is not required. It provides high voltage step-up, balanced phase currents, low device stress, and high efficiency while keeping the design relatively compact and scalable. The article [24] explores how to improve the stability of small DC networks when they provide “constant power loads” (CPLs)—loads whose increasing negative impedance tends to destabilize conventional DC transformers. The authors propose using a two-phase interferometric boost converter (IBC) regulated by a digital controller based on the RST method (i.e., using carefully selected R, S, and T polynomials) instead of conventional PI controllers or slide-mode controllers. This RST-based control is designed by electrode placement and sensitivity shaping: the control parameters are set so that the closed-loop system keeps its electrodes in fixed positions (even under the destabilizing influence of CPLs), ensuring strong disturbance rejection, good robustness to parameter changes, and a rapid response to transient states. Through simulation studies, it has been shown that under sudden changes in load power (CPL variation), load type (from CPL to resistive), or input voltage, the IBC controller equipped with the RST controller maintains the DC bus voltage close to the reference value (with an overshoot of less than ±2%), and recovers its stability within tens of milliseconds. A balanced distribution of current between overlapping phases and good curbing of current ripple were also observed, which helps to reduce stress on components and improves efficiency under dynamic operating conditions. In [25], a strategy was presented to improve energy extraction from PV arrays under partial shading—a situation in which some PV modules are shaded, resulting in the creation of multiple local peaks in the power-voltage (P-V) curve and complicating conventional maximum power point tracking (MPPT).To address this problem, it was proposed to replace the traditional single-switch scheme (class booster switch or CBC) with multiple parallel branches: each PV string is connected to its own Interconnected Boost Switch (IBS), and each IBS is controlled independently using a fuzzy logic controller-based MPPT. This design allows each string of PV cells to operate at its optimal point, enabling the system not only to find a single global maximum power point (GMPP), but also to capture the maximum possible power from all the photovoltaic strings—which may be under different irradiance and shading conditions. Compared to the traditional CBC approach, the proposed fuzzy logic IBC and MPPT system provides higher total output power, better efficiency, more stable DC link voltage, less ripple and harmonic distortion, and improved power quality—both under uniform irradiation and under partial shading conditions. Work [26] proposes a new design for a bidirectional DC/DC converter, in which the number of parallel sub-converters (“multiplicity”) can be dynamically changed according to the operating duty cycle-rather than being fixed as in conventional multi-converter systems. The motivation behind this design is that the amount of current ripple on a DC bus depends not only on the number of parallel channels used, but also on the voltage ratio; as a result, a fixed multiplicity design does not guarantee minimal ripple under all conditions. Through this work, analytical expressions were deduced that relate the total current ripple to the duty cycle and the number of parallel branches, and it was shown that for each range of duty cycles, there is an optimal number of parallel branch transformers that reduce the ripple. Accordingly, a control method was designed that actively monitors the duty cycle, turning on/off the parallel transformer “branches” to maintain minimal ripple—complemented by a current compensation loop to maintain a balanced current distribution between the channels. The idea was validated through simulations and experiments on the prototype: the results showed that the “multi-variable crossover bidirectional converter” significantly reduces DC carrier current ripple compared to a fixed parallel converter, without increasing the switching frequency (which would lead to a deterioration in efficiency).

In general, the interleaving operation of a multiphase converter has been shown to result in a reduction of peak ripple magnitude and enhanced control in the context of current control mode. For an N-phase interleaved converter, the peak current ripple magnitude is reduced by a factor of N, thereby extending the system bandwidth by N times [27].

In recent years, research on power conversion for solar and storage systems has increasingly focused on the adoption of wide-band gap (WBG) devices such as SiC and GaN. These devices enable higher switching frequencies, reduced conduction losses, and improved thermal behavior, making them ideal for compact, high-efficiency designs [28]. Concurrently, state-of-the-art digital control methodologies, encompassing generalized and finite-control-set MPC, have been implemented to optimize dynamic performance, current balancing, and fault tolerance in interleaved and multilevel converter systems [29,30]. Furthermore, the integration of smart control algorithms with digital microcontrollers affords greater flexibility, thereby enabling real-time monitoring, parameter tuning, and intelligent fault detection in renewable energy applications [31]. The integration of these innovations has the potential to enhance the efficiency of next-generation solar energy conversion systems, while also reducing electromagnetic interference and improving reliability.

The proposed study of the two phase’s interleaved boost DC-DC device structure illustrates the operation mode of the converter under current control mode. The converter incorporates a novel active zero-current switching (ZCS) circuit that combines the advantages of a Z-source network and interleaved parallel structure [32,33]. This configuration facilitates high-voltage gain, low-current stress on switches and automatic current sharing between inductors. Similarly, the interleaved boost converter with a single magnetic core contributes to common-mode noise reduction without the necessity of electromagnetic interference (EMI) filters, thereby enhancing power density [34]. In [35], the authors studied common problems when using conventional “strict switching” buck converters to convert DC power from renewable sources (such as photovoltaic panels, fuel cells, and batteries). It has been noted that these transformers often suffer from high conversion losses, large electromagnetic interference, large stress on the transforming elements, and reverse recovery losses in free diodes. To overcome these problems, a modified buck converter topology was proposed that included a “soft switching cell”: using passive components (inductors, capacitors, diodes) alongside active switches (such as MOSFETs), the converter could achieve zero-voltage switching (ZVS)—meaning that the MOSFETs switch when the voltage across them is close to zero. This soft-switching design significantly reduces switching losses, active switching stress, and EMI emissions. It also mitigates reverse recovery losses of free diodes by using a passive soft-switching cell consisting of a capacitor and two diodes. The design is validated through simulation (for solar, fuel cell, or battery sources), showing that a soft-switched buck converter is more efficient, has less electromagnetic noise and can be more compact (smaller size and less heat dissipation) compared to a conventional hard-switched buck converter. In summary, the proposed active ZCS control demonstrates significant performance improvements, rendering it suitable for a variety of renewable energy applications [36]. A series of conducted studies have been published that examine bidirectional converters with multi-mode control strategies. These control strategies include variable frequency control and phase-shift control. The objective of these studies is to optimize the performance of battery energy storage systems. The goal is to achieve zero-voltage switching and increased current rating [37]. In [38], the author compared a conventional Class E inverter-operating under ZVS-with several “improved” variants (specifically, second and third harmonic versions: Class EF2 inverter, Class EF3/Class E/F3 inverter, and the so-called “flat” Class E) under the same design constraints. By scanning parameters such as the switching frequency, duty cycle, capacitance ratio, and load impedance, they measure key performance metrics: output power capacity, efficiency, peak switching voltage and current, resonant capacitor stresses, and peak current/voltage in auxiliary networks. The results of the work show that some improved versions (particularly the EF2 and E/F3 in a specific configuration) can achieve much higher efficiency—around 90%—compared to around 80% for the conventional E-Class under optimal conditions. At the same time, these improved transformers offer 20–30% lower peak voltage and current (for a suitable capacity ratio), reducing stress on the transformers, which helps improve reliability and possibly size. Therefore, this work claims that enhanced harmonic (EF and E/F) inverters provide a more efficient and less stress-intensive alternative to the classic E-class—especially when the design parameters are carefully chosen—making them attractive for applications requiring high-frequency inverters with small size and good efficiency. In [39], the authors present a control strategy for a three-level active dual-bridge DC-DC converter that combines a three-level intermediate clamp topology with a sophisticated MPC method to achieve ZVS for all semiconductor switches and fast dynamic response under varying load or input conditions. The different connection modes of the three-level converter under single-phase shift modulation were analyzed, state-space equations were derived separately for each mode, and then a predictive control algorithm was constructed; at each switching period, the controller evaluates the cost function (measuring the error between the expected output voltage and its reference) and adjusts the phase-shift control variable accordingly to minimize that cost and enforce smooth switching. Simulations show that, compared with traditional control strategies (e.g., dual closed loop with PI), the MPC approach can greatly accelerate startup, e.g., reaching a stable output voltage in about 57.5 ms instead of about 224 ms, and recover more quickly from sudden load changes, all while maintaining ZVS and avoiding overshoot. In [40], the authors propose a novel DC-DC converter topology designed for PV power systems: a three-level QZ-source converter whose output stage uses a double cell arranged in a three-level structure. Unlike many high-gain converters, this design uses only one switch and avoids auxiliary switches, thus simplifying the circuit and control. By combining a QZ source network with a three-level output multiplier, the converter achieves high gain for high voltage (in the prototype: from 36 V input to about 720 V output) without the need for a transformer. Thanks to its design, the inverter also enjoys smooth switching conditions, reducing conduction, switching and ohmic losses, resulting in high efficiency (around 97.6% at full load in the 200 W prototypes) and reduced EMI compared to more complex topologies. Additional advantages: The converter has a common ground between the inputs and outputs (which helps reduce noise), low input current ripple, limited stress on the active and passive components (since the voltage/current stresses remain much lower than the output voltage), and a simple PWM-controlled linear structure—making it perfectly suited for PV power applications that require high-gain DC-DC conversion. In [41], the authors propose a new version of the Quadratic Boost Converter (QBC), specifically designed for renewable energy applications, such as PV power systems, electric vehicle charging stations, and micro-DC grids. The proposed design achieves high voltage gain (significantly raising the low input voltage to a much higher output voltage) by using a coupled inductor and active stabilization circuit, allowing the converter to operate without the need for excessive operating cycles-a common drawback of high-gain designs. Most importantly, the converter employs seamless switching technology: the leakage inductance of the coupled inductor ensures ZVS for the power switches when on, while the diodes activate at zero current (ZCS) when off. This seamless switching system significantly reduces switching losses and stress on semiconductor devices, thus improving the converter’s efficiency and lifespan. A prototype device with a power of 250 W was built and tested; the experimental results confirmed that the converter achieves the promised high gain and high efficiency (peak efficiency reaches approximately 97%) under practical operating conditions. The design also features relatively low voltage across switches; continuous operation (suitable for stable input sources such as photovoltaic cells); low electromagnetic interference; and a simpler, more compact, and non-isolated structure—all of which make it attractive for renewable energy conversion systems.

1.2. Research Objectives and Main Contributions

In this paper, we present the investigation of a fully digital integrated interleaving DC-DC controller based on an Infineon XMC 4200 microcontroller unit (MCU) solution, from current control mode and compensators to the internal current slope generator. The integration of a 300 kHz pulse-width modulation (PWM) working frequency generator unit with interrupt manipulation in conjunction with the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) current prescheduled sampling was conducted. The impact of parasitic inductances (e.g., bond wires, package leads, and long metal traces) on power delivery was analyzed via signal-to-noise ratio measurements for the analog control circuitry and radio frequency propagation from power nodes. In addition, the utilization of high switching PWM has been employed to minimize losses in the inductor, copper, and magnetic core. This approach has been found to offer a substantial enhancement in packing density. The implementation of a specialized single ferrite EE32 core Litz-wire H-class insulation coupled inductor has been adopted in accordance with the IEC 60085 standard (Electrical insulation–Thermal evaluation and designation. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.) requirements.

Interleaved boost converters (IBCs) with soft-switching are well established for high-step-up PV applications. However, achieving > 96% efficiency at 1 kW and 300 kHz while maintaining compact single-core magnetic and EMC compliance remains challenging. Recent IBCs achieve high efficiency through ZVS/ZCS, but typically at lower frequencies (20–100 kHz) or require multiple inductors and complex always-active resonant networks that increase volume and light-load losses [42,43,44].

Key limitation of prior ZCS-IBC research (2020–2025): While demonstrate ZCS in multiphase IBCs, these employ continuous resonant operation across all loads, causing auxiliary losses at light loads (<20% rated power). High-frequency (fsw > 200 kHz) SiC (Science Citation Index)-based IBCs excel at >10 kW but remain costly for 1 kW PV micro-converters. No prior work has combined selective load-adaptive ZCS (>5 A threshold), a single Litz-wound coupled-core inductor, and digital peak-current control to achieve 98.6% peak/96% full-load efficiency at 300 kHz with 120 mA ripple and has passed EMC certification (EN 55014) [45,46].

This study’s novel contribution addresses this gap through a two-phase 12–48 V IBC integrating:

- Load-selective active ZCS (disabled below 5 A via DCR sensing), eliminating reverse recovery while avoiding light-load penalties.

- Single EE32 Litz-core coupled inductor (k = −0.475), enabling 300 kHz with 0.6% ripple.

- Digital 2P2Z peak-current control (XMC4200) with verified stability.

- Full experimental validation, including thermal, dynamic, and EMC testing.

1.3. Structure of the Paper

The paper is divided into seven sections. Following the introduction, the design and analysis are discussed in Section 2. Section 3 of this study focuses on the application of a Litz-wire-based coupled inductor design analysis. Section 4 provides a detailed operating principle of the proposed ZCS cell. Section 5 is devoted to an in-depth examination of peak current mode control integration. Section 6 of this study presents the efficiency and loss analysis. Section 7 provides the experimental results and analysis. Section 8 offers a synopsis of the conclusions that were derived from this experimental work.

2. Design and Analysis

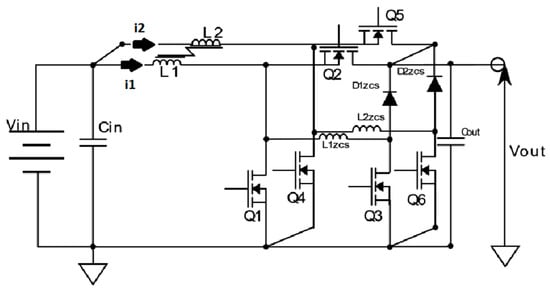

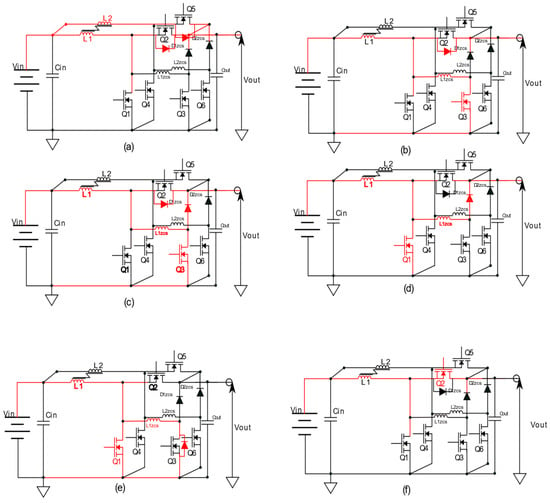

The working principle is illustrated by a simplified two-phase synchronous interleaved boost converter circuit in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the two phases interleaved buck boost converter with built-in ZCS circuit.

The built converter prototype is operating with a single core-coupled inductor, and the input current ripple is contingent on the coupled inductor configuration. In order to ensure that the phase shift between the coupled inductor windings does not exceed 180 degrees, it is necessary to ensure that the mutual inductance between the two inductors wound around the same core, which represents the coupling coefficient, takes a negative value, not with standing the argument in favor of non-inverted or the direct wounded inductor, where the coupling coefficient is positive.

The relationship between the voltage of the inversely coupled inductors and the currents that traverse the inductors for both phase 1 and 2 is expressed as follows:

where L1 and L2 are the self-inductance for the windings; M12 and M21 are the mutual inductance for each phase. These equations could be rearranged to show the inductors voltages under their matrix form by:

where vL1 is the voltage across the self-inductance of winding L1 in the coupled-core inductor of phase 1.

vL2 is the voltage across the self-inductance of winding L2 in the coupled-core inductor of phase 2.

i1 is the current flowing through the winding L1.

i2 is the current flowing through the winding L2.

By assuming that L1 = L2 and M12 = M21, the inductors voltages could be represented by:

where k is the coupling coefficient.

Equation (6) shows how to obtain the value k.

On this case, the mean value of the current by each inductor for both phases is:

where D is the duty cycle.

3. Application of a Litz-Wire-Based Coupled Inductor Design Analysis

Litz wires, a type of inductor, are composed of multiple insulated wires that are wound together to form a single unit. The company has gained renown for its superlative performance in high-frequency applications. A variety of studies on Litzwire windings based on Dowell’s [47] model have been presented [48].

Dowell’s equation was initially developed to calculate the variation in winding resistance with frequency for inductors with a wide foil. According to Dowell, the FR ratio, defined as the AC to the DC resistance ratio in multilayer transformer windings, could be represented by:

Dowell has deduced that the impedance ZW of multilayer winding as for the different parameters constructing the inductor core could be represented by:

With:

where D is the core coupling function; ρ is the resistivity; lT is the mean turn length; Nl is the number of turns per layer; a is the conductor breadth; b is the winding breadth; h is the height of a conductor; m is the number of whole layers in a winding portion; μ0 is the free air magnetic permeability; ωis the angular frequency.

The two terms of the equation representing the resistance ratio relating the resistance caused by the skin effect Rskin to the DC resistance ratio and the resistance caused by the proximity effect Rprox to the DC resistance ratio are, respectively, FRskin and FRprox.

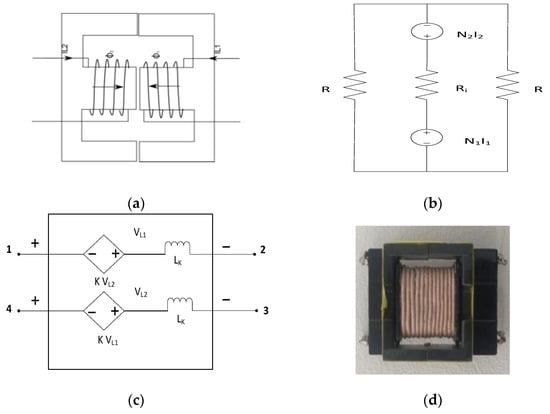

The core structure-winding model for the used inductor design is presented in Figure 2. As illustrated in the accompanying diagram, the windings are wound on the inner leg of the EE32 core, with an equal air gap.

Figure 2.

The core structure winding model of the magnetic part of the converter: (a) Coupled inductor with Litz-wire-based core inductor; (b) reluctance network model of the inductor core; (c) symmetric equivalent circuit of the inverted coupled inductor; (d) real built Litz-wire-based inversely coupled inductor.

Here, Ri is the reluctance of the inner leg of the core while R is the reluctance of the outer legs of the core, hence:

By taking the winding ratio between the two windings 1:1 with respect to N1 = N2 = N, the equations can be represented under the matrix form to obtain the flux in the inner leg as follows:

where Δ = R(R + 2Ri).

With respect to Faraday’s law, the voltage across the coupled inductor can be represented by the following equations:

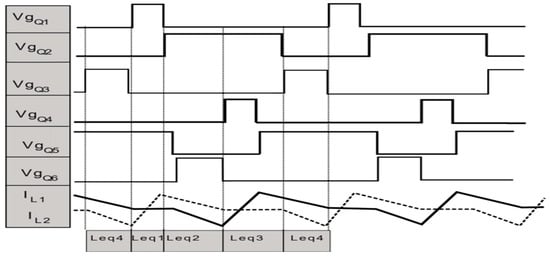

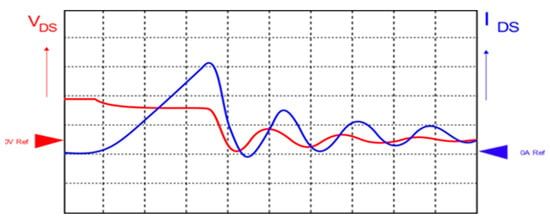

The following section will present the output current and the different gate signals driving the switches for the circuits that were previously presented in Figure 1. The purpose of this presentation is to show the waveform of the conducted inductor currents (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The different waveform signal driving the converter with the associated current for the coupled inductor on both phase 1 and phase 2.

For a given T on applied to the VgQ1, the peak current defined by IPK1 and IPk2, respectively crossing the two windings, could be given by:

The equivalent inductor variation on each step for the given cycle, illustrated above concerning the switching state of the converter within the same cycle, is expressed by:

D′ illustrates the E-core outer diameter.

It has been demonstrated that the activation of the auxiliary ZCS circuit proposed for this topology affects the current slope during the final step of the switching state. Consequently, the converter exhibited the capacity to attain elevated switching frequencies during its operation. Consequently, switching losses are minimized, and the resonant period that could be present at the end of the cycle under a valley oscillation is avoided (Figure 4). The equivalent inductance during the activation of the ZCS for this case presented in the figure above under Leq4 is expressed by:

Figure 4.

Low-side synchronous switch VDS and IDS waveform.

4. Operating Principle of the Proposed ZCS Cell

This section explains the operating mechanism of the proposed ZCS cell integrated into the interleaved boost converter. The converter operates in continuous conduction mode (CCM), and the auxiliary branch is activated to suppress the reverse-recovery current of the synchronous MOSFET and to minimize switching losses at a high switching frequency of approximately 300 kHz. The sequence of events within one switching period is divided into six stages, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

ZCS circuit-triggering process in conjunction to the switching steps during a working cycle: (a) Q2 and Q5 are ON and energy is stored in L1 and L2, (b) ZCS turn-off of Q2 and freewheeling through the corresponding diodes, (c) Conduction of Q3 and resonant discharge in the auxiliary branch and (d) ZCS turn-on of Q1 and energy transfer to the output; (e) Commutation of Q6 and redistribution of current between the interleaved legs, (f) end of the switching period and reset of the circuit for the next cycle.

- Stage 1: Freewheeling Interval (Figure 5a)

At the beginning of the cycle, Q2 is turned OFF. The inductor current continues flowing through the body diode of Q2 toward the output capacitor and load. Since the converter operates in CCM, the inductor current remains above zero and maintain uninterrupted conduction through the diode.

- Stage 2: Activation of the Auxiliary Switch Q3 (Figure 5b)

When Q3 is switched ON, the current in the ZCS inductor Lzcs begins to rise according to:

During this interval, Izcs progressively diverts the current flowing through the diode of Q2, thereby reducing the diode current and preparing Q2 for a zero-current transition.

- Stage 3: Zero-Current Condition of Q2 (Figure 5c)

As the current in Lzcs continues to rise, it eventually reaches the value of the main inductor current IL1. At this moment, the current through the body diode of Q2 is fully canceled. This achieves zero-current turn-off of Q2 and eliminates the reverse-recovery charge typically associated with diode conduction.

- Stage 4: Zero-Current Turn-On of Q2 (Figure 5d)

Once the current through Q2 becomes zero, Q3 is turned OFF and Q1 is immediately turned ON. Because Q2 was brought to zero current beforehand, Q1 turns ON under ideal ZCS conditions, significantly reducing switching losses.

Simultaneously, the drain–source voltage of Q2 transitions toward:

This transition is governed by the intrinsic output capacitances of the MOSFET.

After Q3 is turned OFF, the current in the ZCS inductor decays naturally. When Izcs reaches zero, the diode Dzcs becomes reverse-biased and turns OFF. At this moment, the auxiliary path is fully reset, ensuring that no circulating energy remains in the ZCS branch.

- Stage 6: Return to Steady CCM Operation (Figure 5f)

With the ZCS branch deactivated, Q1 continues to conduct the inductor current in standard CCM mode. When Q1 turns OFF later in the period, Q2 resumes its synchronous conduction until the next ZCS activation. The switching cycle then repeats identically in the following period.

5. Peak Current Mode Control Integration

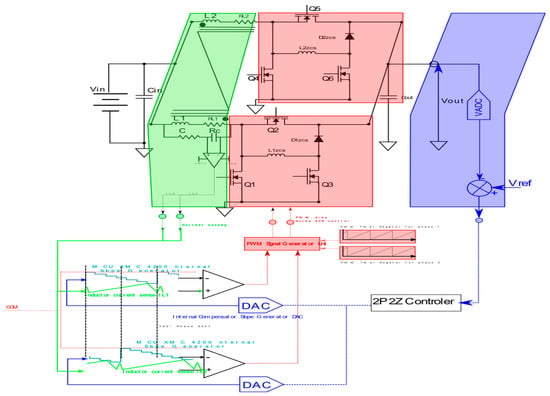

Figure 6 provides a synopsis of the control topology of the interleaved converter with CCM and peak current control mode. In order to guarantee the robustness and stability control of the entire system, including the current control, it is essential that the MCU controller is equipped with the requisite tools for this task. For the purpose indicated, the utilization of an Infineon XMC 4200 32-bit MCU has been determined to be the most suitable option [49].

Figure 6.

Peak-current code controller for interleaved converter topologies.

The latter is responsible for the utilization of various hardware tools that facilitate the development of different power converter topologies.

The comparator and slope generator are of the utmost importance. The comparator and slope generator are equipped with a 30.106 sample/s digital-to-analog converter integrated with a 20 ns speed comparator. In this particular case, the peripheral assists in the control of the slope reference, which, in turn, controls the current limit by triggering the PWM unit with a generated interrupt to update the PWM duty cycle calculation.

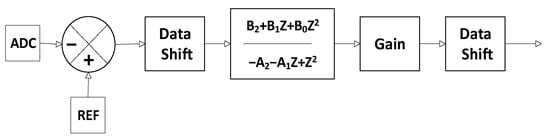

The definition of slope control compensation for peak current control is such that it ensures that no damping is added to the system response beyond what is required. This is because such damping can considerably affect the PWM duty cycle limitation, especially at maximum load. The solution under consideration employs a 2P2Z compensator. Figure 7 presents the loop control diagram of the control block.

Figure 7.

Interleaved converter control loop compensation diagram.

The digital controller illustrated in the above diagram is a type-II compensator. Its transfer function in discrete form can be expressed as follows:

After equation adjustment and manipulation, standard terms of the compensator are defined by:

Table 1 presents the constants defining the digital compensator transfer function, as specified in Equation (23). Each constant is accompanied by its corresponding hexadecimal value utilized in the control code implementation.

Table 1.

Digital compensator coefficients and code constants.

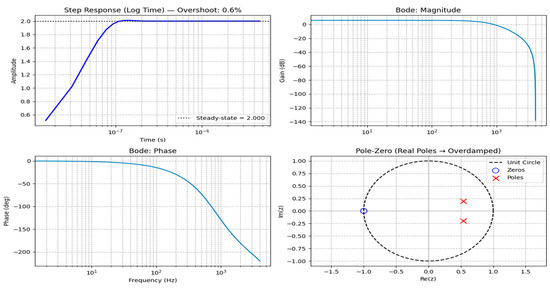

Figure 8 illustrates the stability of the designed digital compensator. The step response shows a fast transient with a steady state value of 2 and a very small overshoot of 0.6%, indicating a well-damped closed-loop behavior. The Bode magnitude and phase plots exhibit high low-frequency gain with adequate gain and phase margins over the relevant frequency range, confirming robust stability of the current mode control loop. The pole–zero map in the z-plane shows closed-loop poles located well inside the unit circle, which is consistent with an overdamped and stable response. Based on the given frequency response data, the system exhibits comfortable stability margins. At the gain intersection point—where the value is 0 dB—the phase is −98.7 degrees at 904.3 Hz, meaning the phase margin is approximately 81.3 degrees. This large positive phase margin indicates a highly stable, well-damped closed-loop response with minimal risk of oscillation. Conversely, when the phase approaches −180 degrees, the magnitude is extremely low (−138.1 dB) at a frequency of 3998 Hz, well below 0 dB. This means that the system never reaches −180 degrees of phase and unit gain simultaneously, giving it an infinite (or very large) gain margin. The large phase margin and large gain margin together confirm that the system is perfectly stable, resistant to transaction changes, and unlikely to experience any instability under normal operating conditions.

Figure 8.

Stability analysis of the designed current mode compensator (step response, Bode magnitude/phase, and pole–zero map).

6. Efficiency and Loss Analysis

The efficiency and power losses of the proposed 12 V to 48 V, 1 kW two-phase interleaved boost converter with coupled inductors were evaluated using an analytical model that accounts for inductor copper losses, MOSFET conduction losses, switching losses, and auxiliary losses. The average and RMS currents in each element are first obtained from the converter operating conditions and are then used to compute the individual loss components.

The output and input currents are related to the output power by:

While the DC current per phase is:

For the coupled inductor, the peak-to-peak ripple current is given by:

The RMS value of the AC component is approximated as:

The RMS current in each inductor phase therefore becomes:

In coupled inductors, there are copper losses. Eddy currents, hysterical occurrences, and other changing magnetic field-related processes are responsible for the losses. A small amount of the energy may manifest as noise, but the majority of it is dissipated as heat [50,51]. Inductor copper losses are evaluated by splitting the Litz-wire resistance into a low-frequency DC part and a high-frequency AC part. The corresponding losses are:

So that the total copper loss is:

Synchronous rectifier MOSFET conduction losses are obtained from the RMS currents of the high side and low side devices. With the duty cycle D, the RMS currents are

And the total MOSFET conduction loss is:

Since zero-current switching is implemented, the remaining switching losses can be represented by a nearly constant switching energy per cycle:

where is the switching energy per switch.

The MOSFET gate drive losses are given by:

where is the on-resistance, and is the total gate drive. The MOSFET characteristics ( and ) are given in the datasheet of the MOSFET.

The equivalent capacitor resistance, which is often included in datasheets, is used to determine capacitor losses. The following formula is used to calculate capacitor losses as follows [52]:

where represents the capacitor’s RMS current value, and represents the equivalent capacitor resistance.

And all residual contributions (gate drive, core losses, and capacitor ESR) are grouped as:

The total converter loss is therefore

And the efficiency as a function of output power is calculated as:

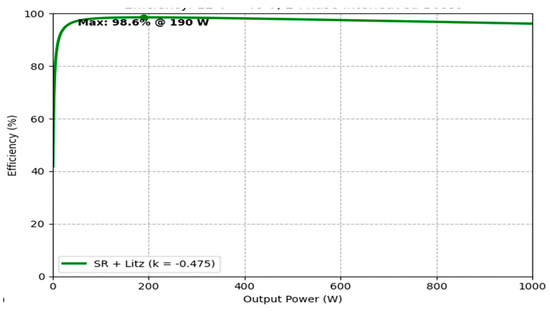

The Figure 9 shows the calculated efficiency of the interleaved 12 V to 48 V boost converter using synchronous rectification and Litz-wire coupled inductors over the output-power range from 0 to 1 kW. The converter reaches a maximum efficiency of about 98.6% at approximately 190 W and maintains efficiency close to 96% at 1 kW, demonstrating low total losses and high performance in the whole operating range.

Figure 9.

Efficiency of the proposed 12 V to 48 V, 2-phase interleaved boost converter (SR + Litz, k = −0.475).

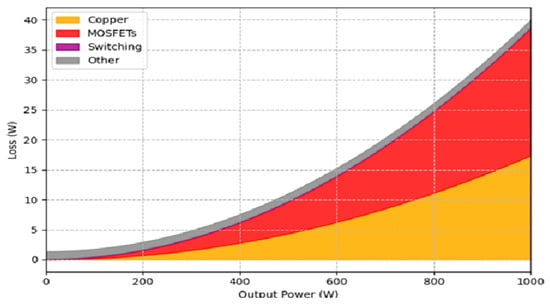

Figure 10 illustrates the power loss breakdown versus output power for the proposed 12 V to 48 V interleaved boost converter employing synchronous rectification and Litz-wire coupled inductors. The stacked areas depict inductor copper losses, MOSFET conduction losses, switching losses, and auxiliary losses (gate-drive, core, and capacitor ESR). At full 1 kW load, total losses reach approximately 40 W, predominantly from copper (≈17.4 W) and MOSFET conduction (≈21.3 W), while switching and other losses remain minimal (<2 W), confirming conduction dominance and effective ZCS suppression of switching losses.

Figure 10.

Loss breakdown of the proposed 12 V to 48 V, 1 kW interleaved boost converter (SR + Litz, k = −0.475).

Table 2 compares the designed work with some existing topologies. This comparison aims to demonstrate the significance of the designed topology compared to other existing topologies. The comparison in Table 2 highlights that the proposed two-phase interleaved structure with the active ZCS cell achieves a superior combination of high step-up ratio, active ZCS operation, very-low-output current ripple, and high efficiency at a rated power of 1 kW, when compared with previously reported converters operating under similar conditions. This confirms that the proposed topology is a strong candidate for medium-power applications such as photovoltaic and energy-storage systems, where high power density, reduced current ripple and high conversion efficiency are essential requirements.

Table 2.

Comparison between the proposed 2 phases IBC with other existing topologies.

7. Testing and Results Analysis

A comprehensive experimental testing program was conducted to evaluate the system’s performance characteristics, including its reliability and response time. The testing program also assessed the system’s compliance with safety regulations and manufacturing standards necessary for market certification.

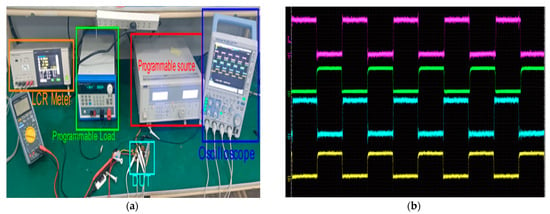

In the initial phase of the experiment, a series of tests were conducted on the constructed inductor to assess its various parameters. As illustrated in Figure 11, the test procedure involved the measurement of resistance and inductance using an LCR meter under various frequencies and voltages. The experimental protocol entails the application of varying voltages (1 V, 3 V, and 5 V Limit) across a spectrum of frequencies ranging from 10 kHz to 500 kHz.

Figure 11.

Litz wire inverse coupled inductor laboratory test.

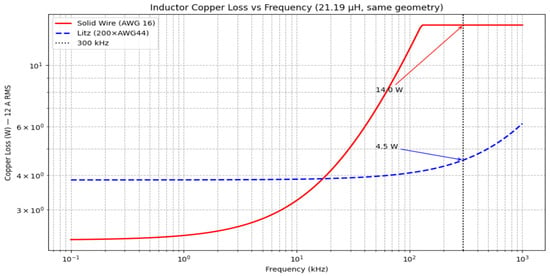

Figure 12 shows the calculated copper loss of the 21.19 µH inductor as a function of frequency for a solid AWG16 winding and a 200 × AWG44 Litz winding, assuming 12 A RMS. At the nominal switching frequency of 300 kHz, the solid wire exhibits an AC resistance of about 97 mΩ and a copper loss of ≈14 W, whereas the Litz wire exhibits about 31 mΩ and ≈4.5 W, corresponding to a 68% reduction in copper loss. This demonstrates the benefit of using Litz wire for the interleaved converter in terms of reduced inductor losses and improved efficiency.

Figure 12.

Calculated copper loss of the 21.19 µH inductor versus frequency for solid AWG16 wire and 200 × AWG44 Litz wire (12 A RMS).

As illustrated in Figure 13, the PWM signals are evident on the various switches for both phases 1 and 2. It is imperative to acknowledge that the utilized MCU (XMC4200 MCU) incorporates a configurable dead time option, which is managed through a predefined register. This feature is instrumental in the control of multiple converter topologies, a necessity in the proposed solution. The dead time is maintained between the PWM signal of the Q1 and Q2 gates of the first phase, in conjunction with the two other switches for phase 2, Q4 and Q5.

Figure 13.

The four PWM switch provided by the XMC 4200 MCU with built-in dead time: (a) Experimental setup including the LCR meter, programmable DC source, programmable electronic load, oscilloscope, and the DUT, (b) PWM gate signals generated by the XMC4200 MCU with built-in dead time: the magenta and green traces correspond to the high-side switches Q1 and Q4 of phases 1 and 2, while the cyan and yellow traces correspond to the low-side switches Q2 and Q5, respectively.

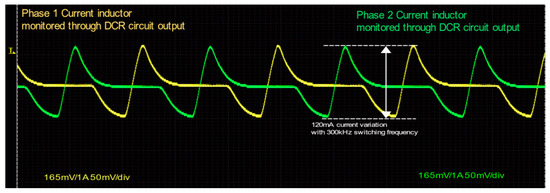

The direct current resistance (DCR) circuit for high-side current sensing is a cost-effective solution that has been applied to the prototype for the inductors’ current sensing in conjunction with the main output device’s current consumption. The circuit has been simulated for the values of the components, checked for limitations, and implemented. The output of the operational amplifier (op amp) is a 165 mV conversion ratio for 1 A passing through the inductor. This value is determined in relation to the hardware requirements. The 32-bit ADC pin on the XMC 4200 MCU is constrained to 3.3 V for maximum analog inputs. For a 20 A current limitation on the device itself and a maximum power output of 1 kW, the perfect conversion ratio is approximately 165 mV. As illustrated in the above figure, the output of the operational amplifier (op amp) targeting the MCU ADC has been plotted. This figure demonstrates the various waveforms of each inductor current with reference to the PWM switching sequence previously discussed. It has been determined that, at a constant load of 20 A, the current ripple on each inductor (a single ferrite core Litz wire coupled) is approximately 120 mA. This calculation is based on a 300 kHz switching frequency and 48 V output voltage reference.

One important advantage of the proposed interleaved boost converter with a coupled inductor is the low-output current ripple. To quantify this effect, the theoretical peak to peak output current ripple (ΔIout,pp) is evaluated using the effective differential inductance Ldiff. The differential inductance is obtained in the aiding configuration (opposing in operation due to reversed winding polarity) as Laiding = Ldiff = 2L(1 + ∣k∣) = 2 × 21.19 × (1 + 0.475) = 62.5 μH.

In the above configuration, L = 21.19 μH is the self-inductance of each winding, and k = −0.475 is the measured coupling coefficient. With Vin = 12 V, duty cycle D = 0.75, switching frequency fs = 300 kHz, and Ldiff = 62.5 μH, the analytical expression ΔIout,pp = Vin × D/(4 × fs × Ldiff) gives ΔIout, pp ≈ 120 mA. This value is in excellent agreement with the measured output current ripple shown in Figure 14, confirming that the low-output current ripple predicted by the interleaving and coupling theory is effectively achieved in the implemented prototype (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

DCR phase’s inductor current output monitoring.

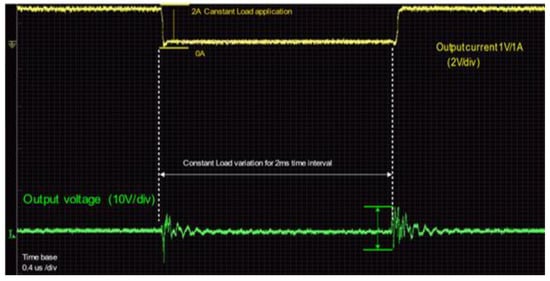

As demonstrated in Figure 15, the system stability response is depicted under constant output voltage reference (24 V) and variable constant load over a predetermined time interval.

Figure 15.

System stability checks with constant voltage reference and 2 A load shutdown and start-up step configuration.

Initially, the converter is connected with a constant load with 2 A references. Subsequently, the programmable load is configured to deactivate the load and reactivate it within a time span of 2 milliseconds. The experimental results demonstrate the system’s capacity to maintain stability during periods of load variation, thereby ensuring that the voltage remains within the pre-set reference range.

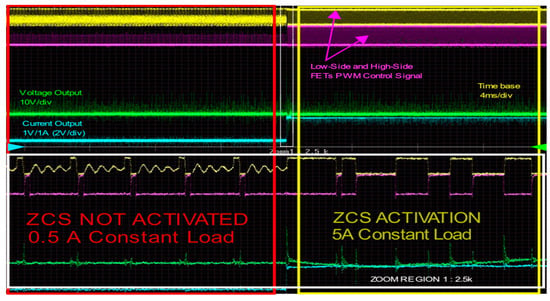

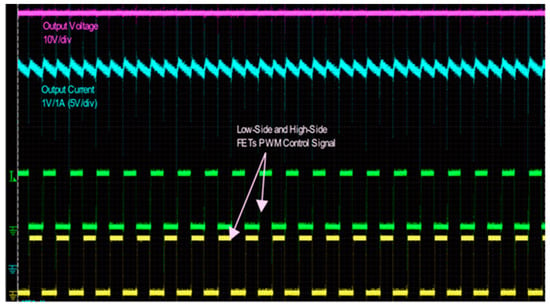

As previously mentioned, under conditions of low demand, there is a possibility that the active ZCS circuit may be deactivated. As demonstrated by the findings of the conducted experiments, the deactivation of the active ZCS at low loads has been shown to enhance the efficiency of the converter. As illustrated in Figure 16, the ZCS circuit is activated during periods of high current demand. The DCR circuit previously illustrated in Figure 6, utilized for the inductor current sense, is employed in conjunction with a numerically integrated threshold limit of 5 A. Upon the occurrence of this limit during a fixed time interval (100 µs), the PWM signal intended for the regulation of Q3 and Q6 is activated on the PWM control unit.

Figure 16.

ZCS circuit system triggering (ZCS is activated for 5 A load reference).

One of the tests performed involves the application of a full load test to the converter. The converter is subjected to a constant load of 20 A, in accordance with the technical requirements. As illustrated in Figure 17, the output current waveform was recorded during a 48 V output voltage reference with a 12 V input constant source and a constant programmable load of 20 A.

Figure 17.

Full load 20 A output current with 48 V voltage reference.

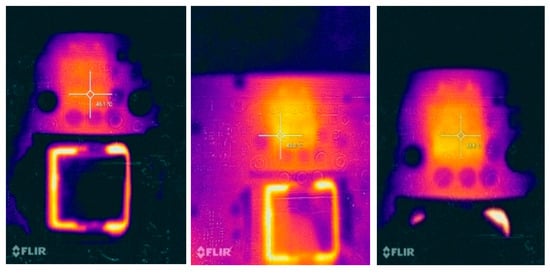

Concurrently, thermal imaging was conducted to assess the temperature rise ratio during the test. This evaluation aimed to evaluate the hardware components’ layout from a lateral perspective and the thermal dissipation on the studied region of the high-power side of the converter from another (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

FLIR thermal imaging for hardware temperature check.

An additional evaluation method employed to assess system stability involves the variation of both the output voltage and current. In this experiment, the converter is synchronized with the programmable load, whereby the variation in the current load is applied concurrently with the voltage output variation. As demonstrated in Figure 19, the behavior of the converter and its stability during the execution of this test are illustrated. As illustrated, the figure demonstrates the activation of the ZCS circuit. Initially, the programmable load is set to 0.5 A. Subsequently, an internal interrupt triggers the voltage reference linked to the ZCS circuit activation comparator with a 5 A load.

Figure 19.

System stability check with load variation and voltage reference variation.

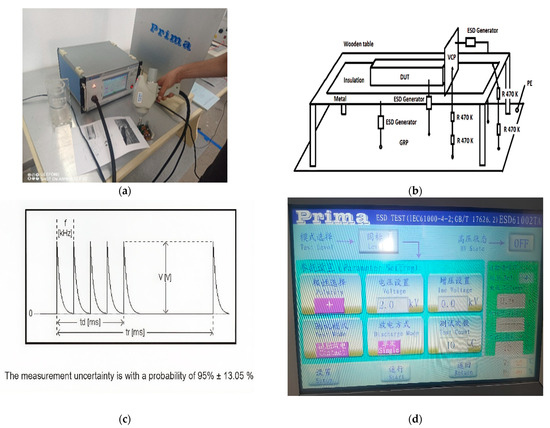

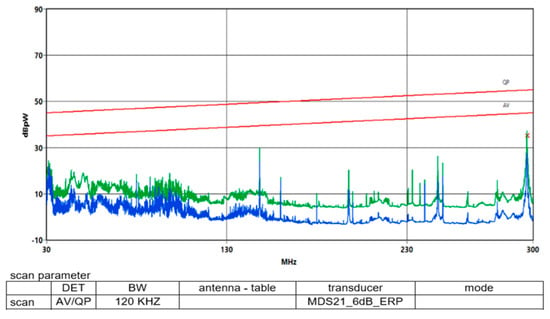

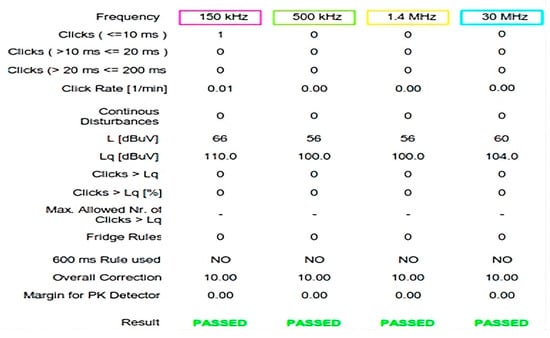

In accordance with applicable safety standards, the converter underwent various tests, in addition to the performance evaluations carried out in the laboratory. Specifically, the tests encompassed the standards for electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) applicable to household appliances, electric tools, and analogous equipment. The testing of emission requirements was conducted in accordance with the provisions stipulated in EN 55014-1, while the mitigation of interference phenomena was addressed by the guidelines outlined in EN 55014-2. The Electrostatic Discharge (ESD) test was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the EN 61000-4-2 standard. As illustrated in Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22, the test reports for ESD, EMI, and EMI-click noise confirm the converter’s successful performance in various noise click frequency tests.

Figure 20.

Interleaved converter EN 61000-4-2 ESD laboratory test. (a) Photo of the ESD test setup on the table (DUT, generator, ground plane, etc.), (b) EN 61000-4-2 standard test schematic (table, VCP, HCP, GRP, ESD gun), (c) pulse waveform diagram, (d) screenshot of the ESD generator display (showing test voltage and settings).

Figure 21.

Interleaved converter EN 55014-1 EMI-Disturbance laboratory test report.

Figure 22.

Interleaved converter EN 55014-1 EMI-click noise laboratory test report.

In Figure 21, the two red straight lines represent the EN 55014-1 radiated-emission limits, where the upper line is the quasi-peak (QP) limit and the lower line is the average (AV) limit over the 30–300 MHz range. The blue curve shows the measured quasi-peak emission of the interleaved converter, while the green curve corresponds to the measured average emission. Both measured curves remain below the respective limit lines across the entire frequency range, confirming that the proposed converter complies with the EN 55014-1 EMI radiated-disturbance requirements

8. Conclusions

This work demonstrated the development and experimental evaluation of a 1 kW two-phase interleaved boost converter incorporating a Litz-wire coupled inductor and an active ZCS cell. The prototype achieved 98.6% peak efficiency, 96% full-load efficiency, and ~120 mA output-current ripples at a high switching frequency of 300 kHz. Loss analysis indicated that total losses at 1 kW were approximately 40 W, dominated by conduction rather than switching losses due to effective ZCS activation above the 5 A threshold. Thermal characterization confirmed a maximum temperature rise below 80 °C during continuous 20 A operations. Dynamic tests showed output-voltage deviations of less than 1% during load steps, while EMI and ESD evaluations verified full compliance with EN 55014-1/2 and EN 61000-4-2 standards. These results confirm that the proposed converter meets the requirements for compact, high-efficiency power-conversion systems in photovoltaic, industrial, and embedded energy applications.

In the future, further experimental tests will be conducted on the topology designed in this paper to determine its operational performance and robustness compared to existing topologies. Additionally, this designed topology will be applied to other energy systems to assess its effectiveness in improving the characteristics of those systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B., H.B., D.K., M.M., and N.B.; methodology, S.B., H.B., and D.K.; software, S.B., H.B., D.K., and M.M.; validation, S.B., H.B., D.K., and M.M.; formal analysis, S.B., H.B., D.K., M.M., and N.; investigation, S.B., H.B., D.K., M.M., and N.; resources, S.B., H.B., D.K., and M.M.; data curation, S.B., H.B., D.K., and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B., H.B., D.K., M.M., and N.B.; writing—review and editing, S.B., H.B., D.K., M.M., and N.B.; visualization, S.B., H.B., D.K., and N.B.; supervision, S.B., H.B., D.K., M.M., and N.B.; project administration, S.B., H.B., and D.K.; funding acquisition, H.B. and N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was fully supported by the Experimental—Demonstration project PN-IV-P7-7.1-PED-2024-0567 (Improving the Fuel Cell Hybrid Electric Vehicle Drivetrain by Implementing a Novel Optimal Real-Time Power Management Strategy), contract no. 58PED, 2024–2025.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The presented study has been carried in conjunction with the EEL (Electrical & Electronic laboratories) of SAMHA (SAMSUNG HOME APPLIANCES); the authors gratefully acknowledge the EEL team for their technical support and expertise, particularly in conducting the EMI and EMC testing procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Mansour Madaciis employed by the company (SAMHA R&I Group) SAMSUNG HOME APPLIANCES. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DC | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| PV | Photovoltaic system |

| ZCS | Zero-current switching |

| EMI | Electromagnetic interference |

| PWM | Pulse-width modulation |

| CCM | Continuous conduction mode |

| DCR | Direct current resistance |

| EMC | Electromagnetic compatibility |

| AC | Alternative current |

| WBG | Wide-band gap |

| MPC | Model predictive control |

| ADC | Analog-to-digital converter |

| MCU | Microcontroller unit |

| FET | Field-effect transistor |

| ESD | Electrostatic discharge |

| LCR | Inductance (L), capacitance (C), and resistance (R) |

References

- Palleswari, Y.T.R.; Vanitha, R. A Novel Hybrid High Gain DC-DC converter for Renewable Energy Applications. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2022, 12, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, K.; Raghuveer Raj, J.; Ramesh, C.B. Experimental Evaluation of Matrix Converter for Wind Energy Conversion System Under Various Abnormal Conditions. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2014, 4, 15–22. Available online: https://www.ijrer.com/index.php/ijrer/article/view/977 (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Laxmanrao, S.P.; Ciji, P.K.; Birendra, K.S.; Athulya, J.V. Simulation and Control of DC/DC Converter for MPPT Based Hybrid PV/Wind Power System. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2014, 4, 801–809. Available online: https://www.ijrer.com/index.php/ijrer/article/view/1543 (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Vendoti, S.; Kunche, G.; Balaga, G.; Bollu, N.K.; Keta, A.K. Fuel Cell Fed EV Motor Using Novel High Gain Landsman Converter With Energy Management System. Int. J. Smart Grid-ijSmartGrid 2025, 9, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavya, S.; Kanakasabapathy, P.; Saikat, C.; Sanjib, K.P. Stability Assessment in Radial Distribution Systems: Leveraging Artificial Neural Networks for High Penetration of Solar PV and EVs. Int. J. Smart Grid-ijSmartGrid 2025, 9, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, M.K.; Le Van, D.; Nguyen, A.T.; Doan, D.T. A New Design of IoT-Based Network Architecture for Monitoring and Controlling Power Consumption in Distribution Grids. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2021, 11, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, S.; Said, D.; Larbi, C.-A. Second Order Sliding Mode Control of DC-DC converter used in the Photovoltaic System according an Adaptive MPPT. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2016, 6, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsokhiry, F.; Adam, G.P. Multi-Port DC-DC and DC-AC Converters for Large-Scale Integration of Renewable Power Generation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chennapragada, A.; Kadapa, H.R. PSO supported Dual Matrix Converter for Doubly fed Induction Generated Driven by variable speed wind turbine system. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2020, 10, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanhu, C.B.; Srutisagar, P.; Swaraj, S. Performance Analysis of a Fuel Cell Connected to a DC-DC Boost Converter. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2024, 14, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latreche, K.; Taleb, R.; Bentaallah, A.; ToubalMaamar, A.E.; Helaimi, M.; Chabni, F. Design and Experimental Implementation of Voltage Control Scheme Using the Coefficient Diagram Method Based PID Controller for Two-Level Boost Converter with Photovoltaic System. Electr. Eng. Electromech 2024, 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adapa, S.K.; Dondapati, R.K.; Korada, P.K.; Setty, S.; Peethala, V. Whale Optimization-Based PI Control for DFIG Wind Energy Systems with Modular Multilevel Grid-Side Converter. Int. J. Smart Grid-ijSmartGrid 2025, 9, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, S.; Kamel, C.; Ben Saad, K. Multiphase Interleaved Bidirectional DC-DC Converter for Electric Vehicles and Smart Grid Applications. Int. J. Smart Grid-ijSmartGrid 2020, 4, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, J.E.; Abbas, H.V. Interleaved High Step-up DC-DC Converter with Diode-Capacitor Multiplier Cell and Ripple-Free Input Current. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2015, 5, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, S.; Saikumar, B. Modelling and Real-time Validation of a Two–input High–gain DC–DC Converter with a Reduced Number of Switches. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2023, 13, 1160–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guepratte, K.; Jeannin, P.-O.; Frey, D.; Stephan, H. High Efficiency Interleaved Power Electronics Converter for Wide Operating Power Range. In Proceedings of the 2009 Twenty-Fourth Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, Washington, DC, USA, 15–19 February 2009; pp. 413–419. [Google Scholar]

- Kulasekaran, P.S.; Dasarathan, S. Design and Analysis of Interleaved High-Gain Bi-Directional DC–DC Converter for Microgrid Application Integrated with Photovoltaic Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekik, A.; Azar, A.; Hameed, I.; Hamida, M.; Amara, K.; Denoun, H.; Kamal, N. Enhancing Photovoltaic Efficiency with the Optimized Steepest Gradient Method and Serial Multi-Cellular Converters. Electronics 2023, 12, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasian, S.; Farsijani, M.; Tavakoli Bina, M.; Abrishamifar, A.; Hosseini, A.; Shahirinia, A. An Interleaved Non-isolated High Gain Soft Switching DC–DC Converter with Small Input Current Ripple. IET Power Electron. 2023, 16, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Jouzdani, M.; Shaneh, M.; Nouri, T. Design of an Interleaved High Step-Up DC-DC Converter with Multiple Magnetic Devices for Renewable Energy Systems Applications. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2022, 2022, 2645938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganga Bhavani, C.; Bhanu Prasad, N.; Ravi Kishore, D. A Novel Interleaved High-Voltage Gain Boost Converter for Solar PV. In Artificial Intelligence and Communication Technologies; Hiranwal, S., Mathur, G., Eds.; Soft Computing Research Society: New Delhi, India, 2023; pp. 991–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Wang, T.; Qin, F.; Hu, H. Investigation of Pulse Power Smoothing Control Based on a Three-Phase Interleaved Parallel Bidirectional Buck-Boost DC–DC Converter. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, T.C.; Mario da Silva, R.; Silva, W.W.A.G.; Maia, N.J.; Tofoli, F.L.; Ribeiro, E.R. Non-Isolated High Step-Up DC-DC Interleaved Boost Converter Based on Coupled Inductors and Voltage Multiplier Cells. Energies 2025, 18, 5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammaa, A.A.; Farh, H.M.H.; Omotoso, H.O.; Ibrahim, A.-W.; Abdurraqeeb, A.M.; Alshaabani, A. RST-Controlled Interleaved Boost Converters for Enhanced Stability in CPL-Dominated DC Microgrids. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samawi, A.A.; Atiyah, A.S.; Al-Jrew, A.H. Power Optimization of Partially Shaded PV System Using Interleaved Boost Converter-Based Fuzzy Logic Method. Eng 2025, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Fan, S.; Zhao, K.; Sun, L. Variable Multiple Interleaved Bi-Directional DC/DC Converter with Current Ripple Optimization. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botker, T.L.; Zhang, H. Charge Pump Having Very Low Voltage Ripple. U.S. Patent 6,661,683, 9 December 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, W.; Lu, J.; Taghizadeh, F.; Bai, F.; Seagar, A. Integration of SiC Devices and High-Frequency Transformer for High-Power Renewable Energy Applications. Energies 2023, 16, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmidene, A.; Bennasr, H.; M’sahli, F. Implementation of Generalized Model Predictive Control Algorithm for DC-DC Boost Converter on STM32. Electrica 2024, 24, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalón, A.; Burgos-Mellado, C.; Rivera, M.; Zuloaga, R.; Levis, H.; Wheeler, P.; García, L.Y. Real-Time Model Predictive Control for Two-Level Voltage Source Inverters with Optimized Switching Frequency. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athwer, A.; Darwish, A. A Review on Modular Converter Topologies Based on WBG Semiconductor Devices in Wind Energy Conversion Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, T.; Sasaki, M.; Imaoka, J.; Yamamoto, M.; Nakano, A. Balanced Two-Phase Interleaved Boost Converter with Integrated Magnetics for Common-Mode Noise Reduction. IEEJ J. Ind. Appl. 2023, 12, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Hong, D.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D. A Novel Two-Phase Interleaved Parallel Bi-Directional DC/DC Converter. Arch. Electr. Eng. 2024, 70, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondzik, A.; Piróg, S.; Stala, R.; Penczek, A.; Gucwa, P. DC-DC Boost Converter with Reduced Switching Losses in Wide Range of Voltage Gain. Energies 2023, 16, 4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, G.; Kiran Kumar, M.; Govardhan Rao, K.V.; Anuradha Devi, T.; Rami Reddy, C.; Thulasi, B.; Basem, A.; Pidikiti, T.; Naga, S.K.C. Mitigation of Switching Losses and Electro Magnetic Interference with Buck Converter for Renewable Energy Applications. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2025, 15, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakasegawa, E.; Chishiki, R.; Sedutsu, R.; Soeda, T.; Haga, H.; Kennel, R.M. Comparison of Interleaved Boost Converter and Two-Phase Boost Converter Characteristics for Three-Level Inverters. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.-Y.; Liu, K.-H.; Chen, L.-X.; Chen, C.-Y.; Shih, C.-H.; Lin, J.-T. Multi-Mode Control of a Bidirectional Converter for Battery Energy Storage System. Energies 2022, 15, 8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashique, R.H.; Maruf, M.H.; Sourov, K.M.S.H.; Islam, M.M.; Islam, A.; Rabbani, M.; Islam, M.R.; Khan, M.M.; Shihavuddin, A. A Comparative Performance Analysis of Zero Voltage Switching Class E and Selected Enhanced Class E Inverters. Electronics 2021, 10, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tan, L.; Li, J.; Ji, C. Research on model predictive control strategy of three-level dual-active bridge DC-DC converter. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezhdar, M.M.; Rezvanyvardom, M.; Setoudeh, F.; Horri, A.; Tavakoli, M.B. Analysis, design and control of A high step-up three level Quasi-Z-Source PWM DC-DC converter for photovoltaic applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghabsi, F.; Sahid, M.R.; Ayop, R.; Alanssari, A.; Al Takrouri, M.; Swadi, M.; Sahhouk, M.A.; Malik, H.; Jadoun, V.K. High gain and high efficiency soft switching quadratic boost converter for renewable energy applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerai, A.A.; Shah, S.J.; Maheshwari, L.; Khan, K.A.; Makda, I.; Qamar, H.; Usman, A. Comparative Performance Analysis of GaN FET and Silicon MOSFET in Closed-Loop Synchronous Buck Converter for Electric Vehicle Auxiliary Power Module. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Workshop on Control and Modeling for Power Electronics (COMPEL), Lahore, Pakistan, 24–27 June 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; He, L. Analyses and Design of a High Power Bidirectional 48V-12V DCDC Converter System for Electric Vehicle Application. In Proceedings of the IECON 2021–47th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Toronto, ON, Canada, 13–16 October 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, B.G.; Kalavathi, M.S. Experimental Analysis of an Interleaved Boost Converter for Electric Vehicle Applications. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Res. 2024, 12, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, F.J.; Sharma, S.R. Comparison of Highly Compact Interleaved 48 V–12 V DC–DC Converters for Vehicle Systems (Student Project Report). Paderborn University, Paderborn, Germany, 2022. Available online: https://ei.uni-paderborn.de/fileadmin-eim/elektrotechnik/fg/lea/Lehre/Projekte/Finish/Comparison_of_Highly_Compact_Interleaved_48V-12V_DC-DC_Converters_for_Vehicle_Systems_SoSe_21.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Webb, S.; Liu, Y.-F. A Zero Inductor-Voltage 48V to 12V/70A Converter for Data Centers with 99.1% Peak Efficiency and 2.5kW/in3 Power Density. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 15–19 March 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1858–1865. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, S.; Chu, M.; Wang, W.; Wan, P.; Peng, X.; Lu, H.; Li, P. Modelling and Optimization of Winding Resistance for Litz Wire Inductors. IET Power Electron. 2021, 14, 1834–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Shen, Z. Modeling of Litz Wire Winding AC Resistance Based on Improved Segmented Equivalent Circuit. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 1135–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunathan, K.R. History of Microcontrollers: First 50 Years. IEEE Micro 2021, 41, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, T.; Delshad, M.; Adib, E.; Yazdani, M.R. A New Simple-Structure Passive Lossless Snubber for DC–DC Boost Converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 2207–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, R.; Ibrahim, N.F.; Mahmoud, M.M.; Alkuhayli, A.; Khaled, U.; Beroual, A.; Saleeb, H.M.I. Enhanced Multiphase Interleaved Boost Converter Interface for Grid-Connected PV Power System. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 151940–151954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, N.; Jafari, A.; Soleimanzadeh, R.; Bollier, N.; Abeyratne, S.G.; Matioli, E. Hard-Switching Losses in Power FETs: The Role of Output Capacitance. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 7604–7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Yang, S.P.; Huang, C.M.; Hu, P.Y. High Step-Up Interleaved DC–DC Converter with Voltage-Lift Capacitor and Voltage Multiplier Cell. Electronics 2025, 14, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Yang, S.P.; Huang, C.M.; Huang, P.S. Analysis and Design of a New High Voltage Gain Interleaved DC–DC Converter with Three-Winding Coupled Inductors for Renewable Energy Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.; Liu, H.D.; Lin, C.H.; Lu, S.D.; Yang, S.J.; Sarwar, A. A Novel High-Voltage Gain Step-Up DC–DC Converter with Maximum Power Point Tracker for Solar Photovoltaic Systems. Processes 2023, 11, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Todd, R.; Forsyth, A.J. Predicting SiC MOSFET Behavior Under Hard-Switching, Soft-Switching, and False Turn-On Conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 9001–9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. Digital-Based Zero-Current Switching (ZCS) Control Schemes for Three-Level Boost Power-Factor Correction (PFC) Converter. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).