Abstract

World models are currently a mainstream approach in model-based deep reinforcement learning. Given the widespread use of Transformers in sequence modeling, they have provided substantial support for world models. However, world models often face the challenge of the seesaw phenomenon during training, as predicting transitions, rewards, and terminations is fundamentally a form of multi-task learning. To address this issue, we propose a Mixture-of-Experts-based world model (MoE-World), a novel architecture designed for multi-task learning in world models. The framework integrates Transformer blocks organized as mixture-of-experts (MoE) layers, with gating mechanisms implemented using multilayer perceptrons. Experiments on standard benchmarks demonstrate that it can significantly mitigate the seesaw phenomenon and achieve competitive performance on the world model’s reward metrics. Further analysis confirms that the proposed architecture enhances both the accuracy and efficiency of multi-task learning.

1. Introduction

World models are computational frameworks that can model environments and predict future states [1]. Their core purpose is to construct internal models through perception and experience, enabling reasoning, planning, and decision-making. By modeling both perceptual and temporal aspects of the environment, world models can process multimodal inputs such as images and text and support a wide range of downstream tasks [2], including planning, control, and decision-making. In embodied intelligence, they provide agents with predictive and causal understanding of physical environments [3], allowing more reliable interaction and adaptation [4].

Following Ha and Schmidhuber’s formulation [5], world models typically formulate reinforcement learning tasks as partially observable Markov decision processes (POMDPs). The training process generally consists of two stages. The first stage involves learning from world experiences, in which real-world interactions are sampled. During this stage, models are trained to abstract images into state representations, reconstruct states using observation models, handle state-sequence transitions, and predict rewards. The second stage focuses on learning behaviors, specifically through the Actor–Critic algorithm in reinforcement learning.

Currently, Transformer-based world models in the first stage predict rewards, terminations, and transitions based on the output of the Transformer [6], which use sequence modeling in the world model stage with an architecture resembling GPT [7,8,9], i.e., a stack of multiple Transformer decoder blocks. This is an example of hard parameter sharing, where a shared base layer is combined with separate tower networks for each task. This structure is suitable for scenarios where the tasks are highly correlated and follow similar distributions. However, the downside of this approach is that sharing parameters across multiple tasks can lead to the seesaw phenomenon [10], where some sub-tasks perform well while others perform poorly.

Prior studies have shown that Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architectures are particularly effective for such temporal multi-task learning settings, as expert specialization helps disentangle heterogeneous objectives and improves both sample efficiency and prediction accuracy. For example, expert-driven decomposition has been successfully applied in state abstraction for POMDPs, where separate expert policies guide agents toward more informative latent representations and reduce interference across learning objectives [11]. Inspired by these findings, introducing expert modules into world-model training provides a principled way to stabilize multi-task optimization.

Modern research leans towards soft parameter sharing, where each task has its own set of parameters and multiple sets of parameters are trained jointly. There is some interaction among the parameters of different tasks, often via gating mechanisms that model their relationships. This approach reduces task interdependency and minimizes the seesaw phenomenon. The MoE model is an example of such a structure [12,13].

Typically, a MoE model comprises multiple expert networks and a gating network. The gating network assigns weights to the outputs of the expert networks to produce the final result. This approach enhances the stability and efficiency of the training process. Consequently, MoE has been applied to various tasks in fields like natural language processing and computer vision, where it has demonstrated improved performance [14,15,16,17,18]. Our proposed method incorporates a MoE network into the world model to improve the precision and efficiency of training during the world experience phase.

We conduct experiments on the Atari 100k benchmark [19]. In terms of training duration, our method is more time-efficient due to the reduced depth of the shared layers and the addition of MoE layers, which enable parallel reasoning. As a result, the training time for the two-stage world model is significantly shorter than before. In terms of prediction accuracy, our method decreases the mean loss across various task test sets for most games, thereby improving model accuracy during the world experience learning phase. In terms of final rewards, the agents trained under the same conditions outperform the baseline in 19 games, in the human-normalized aggregate metric, our approach surpasses current state-of-the-art methods in mean, median, interquartile mean (IQM), and optimality gap. In summary, the key contributions of this work are as follows:

- We propose MoE-World, a temporally conditioned Mixture-of-Experts architecture designed specifically for world models, enabling expert specialization across state, reward, and termination predictions while preserving shared representations where beneficial.

- We design a temporally conditioned gating mechanism that enables dynamic routing across tasks, effectively mitigating the seesaw phenomenon during training. The proposed architecture assigns dedicated experts to each prediction objective while the gating network adaptively modulates cross-task dependencies through learned weighting, allowing specialization without losing beneficial shared structure.

- We demonstrate consistent improvements on the Atari 100k benchmark, showing superior sample efficiency and learning stability compared to baselines.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the materials and methods, including the dataset (Section 2.1), the proposed MoE-World architecture (Section 2.2), its mathematical formulation (Section 2.3), and the experimental configuration (Section 2.4). Section 3 reports the experimental results, covering training and inference behavior (Section 3.1), loss analysis (Section 3.2), and performance statistics on the test set (Section 3.3). Section 4 offers further discussion, and Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Materials and Methods

This study investigates multi-task learning in world models, focusing on the joint prediction of states, rewards, and terminations. The research problem centers on destructive interference arising from deep shared architectures, which destabilizes optimization. We hypothesize that introducing task-specific experts with temporally conditioned gating can mitigate this interference and improve sample efficiency. To test this hypothesis, we propose MoE-World, a Transformer-based Mixture-of-Experts framework with reduced shared depth and stacked expert layers. The method employs temporal gating, expert routing, and uncertainty-aware multi-task optimization. Experiments are conducted using the Atari Learning Environment, with IRIS [6] as the baseline and PyTorch 1.10.1 as the primary implementation tool.

2.1. Dataset

The Atari 100k benchmark plays a pivotal role in reinforcement learning research. It comprises a 26-game subset of the Atari Learning Environment (ALE), carefully selected to cover a broad spectrum of gameplay characteristics. Each agent is limited to 100,000 environment interactions, roughly equivalent to two hours of human gameplay, making sample efficiency a central challenge. Figure 1 shows examples from the first four games in the dataset.

Figure 1.

Examples from the first four games in the Atari 100k.

The Atari 100k dataset exhibits several notable characteristics. First, it demonstrates exceptionally high diversity. By encompassing a wide variety of Atari games that differ substantially in gameplay mechanics, objectives, and difficulty levels, the dataset includes a rich spectrum of scenarios and challenges. For example, in Ms. Pac-Man, the agent must navigate a maze as Pac-Man, aiming to consume all pellets while avoiding four differently colored ghosts; in contrast, in Breakout, the agent must precisely control a paddle to bounce a ball and eliminate rows of bricks. These two games impose fundamentally different decision-making demands on the agent. Second, the dataset features nontrivial complexity in both its state and action spaces. The high-dimensional state space is composed of raw pixel observations from the game screen, while the action space consists of discrete in-game operations—such as moving left, moving right, or firing. This intricate structure provides a highly challenging and valuable testbed for research in reinforcement learning algorithms.

Several representative baselines have been developed on this benchmark. SimPLe [19] employs a VAE-LSTM world model combined with PPO [20] for policy optimization. CURL [21] introduces contrastive representation learning to enhance sample efficiency. DrQ [22] improves performance stability by averaging gradients across multiple augmented views. SPR [23] utilizes self-predictive representations as an auxiliary objective to stabilize training. IRIS [6] further advances the world modeling stage by employing autoregressive Transformers to model complex state transitions.

2.2. Methods

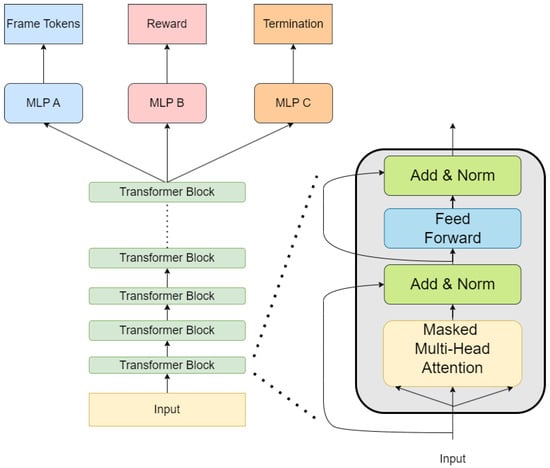

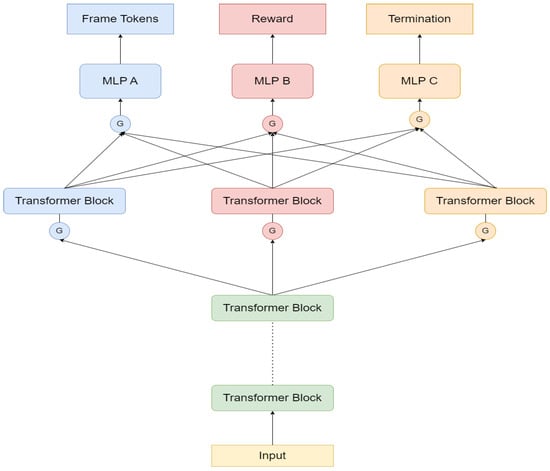

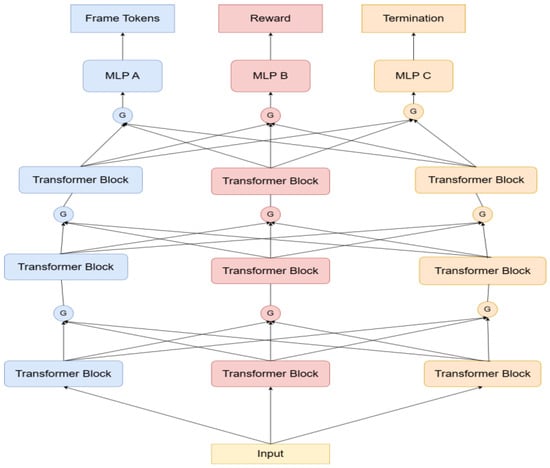

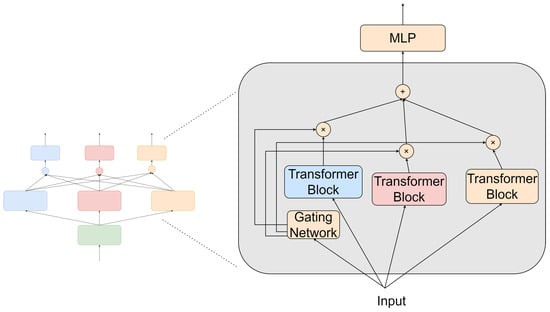

In MoE-World, each task is assigned an expert network to capture task-specific features, while a gating mechanism adaptively controls inter-task dependencies, thereby mitigating interference and alleviating the seesaw effect in multi-task optimization. Furthermore, to improve parameter efficiency and model generalization, the depth of the shared Transformer layers is reduced, and newly designed MoE layers are stacked to support multi-task world experience learning. The architecture of our baseline model [6] is shown in Figure 2. We reduce the depth of the shared Transformer layers to reduce parameter sharing and integrate a MoE layer on top. Figure 3 illustrates the network structure of the world experience stage multi-task learning with a single-layer MoE model, while Figure 4 shows the network structure of the world experience stage multi-task learning with a multi-layer MoE model.

Figure 2.

Multi-task learning network structure during the world-experience learning stage of IRIS.

Figure 3.

Multi-task learning network structure during the world-experience learning stage after adding a single-layer MoE layer.

Figure 4.

Multi-task learning network structure during the world-experience learning stage after adding multiple MoE layers.

The architecture of the MoE layer is depicted in Figure 5. The detailed structure of our proposed Transformer-based MoE layer consists of a single Transformer Block serving as the expert layer for the respective task, followed by a single-layer Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) acting as a gating layer to filter the expert output.

Figure 5.

MoE layer network structure.

2.3. MoE-World Mathematical Formulation

The MoE-World employs a task-aware gating mechanism to dynamically route input representations to specialized experts. The gating layer output corresponding to the k-th task is represented as follows:

Here, x denotes the input to the MoE layer, and represents the weight vector function that calculates the weights assigned to each expert for task k, which is derived by applying a linear transformation followed by a softmax activation function to the input x, as described in Equation (2).

is the matrix consisting of the outputs of all experts, as described in Equation (3):

where m represents the number of experts, and the final output of the k-th task is given by Equation (4):

where represents the last independent network of the k-th task, which consists of two layers of MLP.

For the loss function during the world experience learning phase, the current mainstream approach is to sum the losses across multiple tasks, as shown in Equation (5):

In this context, , , and represent the losses for transition, reward, and termination prediction, respectively. The predictions for these three are classified tasks. However, summing their losses can cause the model’s gradient updates to favor the tasks with larger loss values. Therefore, it is necessary to define weights for each task’s loss to balance the network’s learning. If the weights are set through manual adjustments or search methods, it can lead to a significant amount of additional computation. In multi-task learning, task uncertainty can be represented as the relative confidence across tasks [24]. We define homoscedastic uncertainty as task-related weighting.

We incorporate a learnable noise parameter into the loss function for each task to model task-specific uncertainty. This is achieved by defining a probabilistic model and maximizing the Gaussian likelihood to learn the task parameters. In classification tasks, the network output for each task is normalized using the Softmax function, which can be calculated as follows:

We model the classification using a learnable noise parameter to transform the classification model into a Boltzmann distribution, as shown in Equation (7):

The log-likelihood of the classification model is represented by Equation (8):

For computational convenience, an approximation is made as follows:

Therefore, after introducing homoscedastic uncertainty noise parameters for the three tasks, the loss function can be expressed in the form of a sum by utilizing the multiplicative property of joint distributions and splitting the log-likelihood, as shown in Equation (10):

After adding smoothing terms, the final loss is calculated as follows:

2.4. Experimental Configuration

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with four Nvidia TITAN XP 12GB GPUs. The implementation was developed using Python 3.9 and PyTorch 1.10.1 with CUDA 11.7 and cuDNN 8.5. The Atari Learning Environment was configured using ALE-py 0.7.4, atari-py 0.2.6, and AutoROM 0.4.2 for ROM management and environment initialization. Additional dependencies included Gym 0.19.0 for environment wrappers, NumPy 1.24.4 and SciPy 1.7.0 for numerical computation, and reliable 1.0.8 for statistical evaluation of Atari 100k performance metrics.

Experiments were performed on the Atari 100k benchmark, with each game trained once using seed 0 due to resource constraints. Training was performed on the four aforementioned TITAN XP GPUs, requiring approximately seven days per game. The optimal configuration used in our experiments is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The world model parameters incorporating the MoE.

Due to the high computational cost of training world models, we were unable to perform full multi-seed training across all 26 games. To partially mitigate this limitation, we adopt the evaluation protocol used in the prior actor–critic literature, such as TD3 [25], in which a model trained once is evaluated across multiple random seeds. In our experiments, each trained checkpoint is evaluated using five inference seeds and averaged over 100 episodes, which stabilizes performance indicators and reduces variance caused by environment stochasticity. This setup ensures a fair comparison with the IRIS baseline under identical training conditions.

3. Results

The reward results for the 26 games are shown in Table 2, with 19 games demonstrating rewards superior to the baseline model [6]. We compare MoE-World against a set of widely used baselines in pixel-based reinforcement learning. Among them, SimPle [19] was one of the first to use video prediction as a world model for Atari, showing that agents could learn policies by imagining future states. CURL [21] improves data efficiency in model-free settings by learning compact representations through contrastive learning. DrQ [22], now a standard baseline, stabilizes training with strong image augmentations during policy updates. Building on consistency-based learning, SPR [23] enforces self-predictive alignment in the representation space, which is particularly effective when data are scarce. The strongest current competitor, IRIS [6], leverages a Transformer-based world model with shared decoding layers and currently holds state-of-the-art results on Atari 100k. Against this set of mainstream baselines, MoE-World achieves optimal rewards in 13 out of the 26 Atari 100k games.

Table 2.

Returns on the 26 games of Atari 100K. Bold numbers indicate the top methods.

When evaluating an agent’s performance on the Atari 100k benchmark, a commonly used metric is the human-normalized aggregate score. This metric is calculated using the formula shown in Equation (12), where HNS denotes the Human-Normalized Score, is the score of the random strategy, and is the score of humans.

A comparison between our architecture and mainstream world model methods is presented in Table 3, showing the mean, median, IQM, and optimality gap aggregated across 26 games. Our architecture, MoE-World, achieves the highest performance.

Table 3.

HNS metrics of Atari 100k. MoE-World is optimal on all four metrics. An upward arrow indicates “larger is better,” while a downward arrow indicates the opposite. Same below for following tables. Bold indicates the best performance.

3.1. MoE-World in Training and Inference Time

The average training durations for the two stages of our proposed architecture, which encompasses a total of 26 games, are comprehensively detailed in Table 4. These durations provide valuable insights into the performance of our model during the training phase. A crucial aspect of our proposed structure is the incorporation of the MoE layer. Given the parallel inference mechanism of each expert within the MoE layer, we have strategically reduced the depth of the shared layer. This adjustment, coupled with the introduction of the MoE layer, serves to diminish both the training and inference times for the two stages of the world model. Consequently, this refinement significantly augments the overall efficiency of both the training and inference processes. The reduced depth of the shared layer enables the model to learn more quickly and efficiently, while the parallel inference of experts within the MoE layer further accelerates the training and inference times.

Table 4.

The average training time for the two stages before and after adding the MoE layer. The bolded numbers represent the methods that take less time.

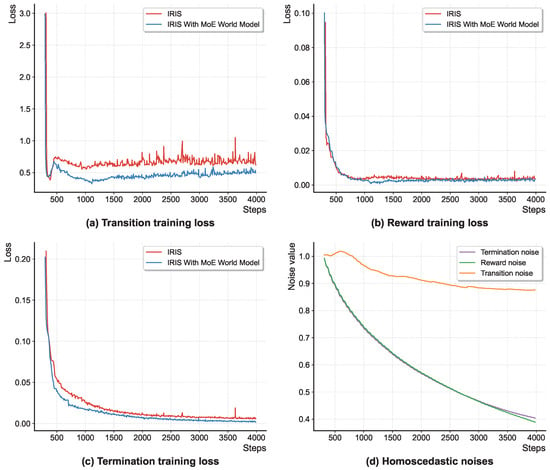

3.2. MoE-World in Loss Value

The changes in loss values for individual tasks during the training phase of the Breakout game, both before and after the incorporation of the MoE layer, are vividly illustrated in Figure 6a–c. A comparative analysis of these figures reveals that the initial approach, which involved sharing a solitary set of parameters across three tasks, led to fluctuations in loss values throughout the training process. This instability arises from the inherent inability of such a monolithic structure to simultaneously meet the diverse learning demands of all three tasks. Consequently, the training process experiences a seesaw effect, where the loss values for one task increase while those for another decrease, and vice versa.

Figure 6.

Multi-task learning training loss and homoscedastic noises.

However, the introduction of the MoE layer addresses this issue by stabilizing the loss values for each task during training. This stabilization suggests that the learning process of one task is now decoupled from the others, enabling the model to learn more effectively. Furthermore, the MoE layer enables the model to dynamically adapt to the changing demands of each task, leading to more stable and predictable loss values.

In addition to stabilizing the loss values, the MoE layer also exhibits adaptability to the inherent uncertainties of the tasks. This adaptability is demonstrated in Figure 6d, which illustrates the evolution of homoscedastic noise parameters () during the training process. These parameters are critical for assigning weights to the losses of different tasks during training. By adapting to the uncertainties of the tasks, the homoscedastic noise parameters enable the model to dynamically adjust the weights assigned to each task, leading to more effective and efficient learning.

3.3. MoE-World in Mean and Standard Deviation of Test Set Loss

The mean and standard deviation of the test set loss in the training termination prediction task before and after adding the MoE layer are shown in Table 5. The mean loss of the test set for 20 games is smaller. The mean and standard deviation of the test set loss for the Transition prediction task are shown in Table 6, with the mean loss of the test set for 22 games being smaller. The mean and standard deviation of the test set loss for the reward prediction task are shown in Table 7, with the mean loss of the test set for 22 games being smaller. Therefore, using a mixed-experts structure can enhance the accuracy during the world model’s experience learning phase.

Table 5.

The mean and standard deviation of termination predictions on the test set before and after adding the MoE layer, where the bolded numbers represent the methods with a smaller mean loss on the test set.

Table 6.

The mean and standard deviation of transition predictions on the test set before and after adding the MoE layer, where the bolded numbers represent the methods with a smaller mean loss on the test set.

Table 7.

The mean and standard deviation of reward predictions on the test set before and after adding the MoE layer, where the bolded numbers represent the methods with a smaller mean loss on the test set.

For the training-termination prediction task, across 20 games, the mean test-set loss decreases after MoE integration. This reduction in mean loss indicates that the model is better able to predict the termination of training for each game, leading to more accurate and efficient training processes. Similarly, for the transition prediction task involving 22 games, Table 6 shows a reduction in the mean test set loss post-MoE integration. This improvement suggests that the model is better able to predict state transitions in each game, yielding more accurate and reliable simulations. Analogously, Table 7 demonstrates a decrease in the mean test set loss for the reward prediction task, spanning 22 games. This reduction in mean loss indicates that the model is better able to predict the rewards associated with each action in each game, leading to more effective and efficient decision-making.

Collectively, these findings underscore the efficacy of the MoE structure in enhancing accuracy during the world model’s experience-learning phase. By incorporating a MoE layer, we enable the model to adapt to the changing demands of each task, yielding more stable and predictable performance across a wide range of games.

4. Discussion

A key limitation of multi-task learning in world models arises from hard parameter sharing, whereby the optimization of one objective can negatively affect the learning of others, leading to what is known as negative transfer or destructive interference [26]. The IRIS baseline, characterized by deep shared Transformer layers, exemplifies this limitation. Our results demonstrate that replacing this architecture with a shallow shared encoder and a MoE layer effectively alleviates task interference. Reduced test losses across state, reward, and termination predictions in most Atari 100k games, together with smoother task-specific convergence in Figure 6a–c, provide empirical evidence that expert specialization via gating successfully regulates inter-task dependencies.

Beyond architectural improvements, loss weighting plays a crucial role in multi-task optimization. Conventional loss summation neglects task-scale discrepancies and uncertainty, often allowing high-variance tasks to dominate the training process. Our homoscedastic uncertainty weighting addresses this by introducing learnable noise parameters (, , ), enabling the model to adaptively balance loss magnitudes. As illustrated in Figure 6d, the model autonomously down-weights the high-magnitude state prediction task, preventing it from overshadowing reward and termination learning. This principled, data-driven balancing mechanism significantly contributes to the stability and efficiency of MoE-World.

The broader implications of these findings extend to sample-efficient reinforcement learning. Superior results across aggregate performance indicators, including median score, IQM, and optimality gap (Table 3), demonstrate that MoE-World not only achieves higher peak performance but also provides more reliable behavior across diverse environments. At the same time, MoE-World shows favorable computational characteristics: despite the common perception that Mixture-of-Experts architectures introduce additional overhead, our implementation reduces wall-clock training time through parallel expert execution (Table 4). Furthermore, the model exhibits a smaller parameter footprint than IRIS, decreasing from 8,448,005 to 7,662,098 parameters (a 9.3% reduction). This reduction arises from replacing IRIS’s ten sequential Transformer blocks with a shallower architecture composed of five shared Transformer layers and three expert-specific layers; although a gating network is added, the overall depth is reduced. These properties collectively highlight the computational practicality and scalability of the proposed framework for large-scale and real-time deployment.

Although MoE-World introduces a tailored Mixture-of-Experts architecture for learning temporally structured world models, two main limitations remain. First, the performance of the framework depends on appropriate expert capacity and gating stability; extreme task imbalance or highly noisy trajectories may lead to suboptimal expert routing. Second, while the architecture reduces destructive interference, it also introduces additional structural complexity compared to fully shared models, requiring careful tuning of expert depth, routing mechanisms, and the number of tasks per expert.

A limitation of this study lies in the restricted exploration of MoE configurations. Prior work such as STORM [27] indicates that fewer Transformer layers may even improve performance, with models using two layers outperforming deeper four- and six-layer variants. Inspired by this finding, future extensions of MoE-World may explore reducing the number of shared layers or rebalancing the shared-to-expert ratio. However, because task characteristics vary substantially across domains, such architectural adjustments require systematic empirical validation. These additions clarify the computational implications of our design, outline the scope of the current contribution, and highlight promising directions to broaden the applicability and robustness of MoE-based world models.

Future research should further align with these limitations by exploring computationally lighter MoE variants and scalable routing mechanisms, as well as studying adaptive expert allocation conditioned on environmental dynamics. In addition, extending uncertainty modeling to heteroscedastic forms may yield better input-dependent loss balancing. Finally, validating the framework in non-Atari domains such as 3D navigation or robotic control would help assess whether the proposed principles generalize beyond discrete-action settings and support broader real-world applicability.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces MoE-World, a Mixture-of-Experts architecture tailored for multi-task learning in world models. By combining expert specialization with homoscedastic uncertainty weighting, the approach mitigates destructive interference and improves the stability of world-model training. Experiments on the Atari 100k benchmark demonstrate consistent gains in sample efficiency and convergence across a broad set of tasks.

While MoE-World clearly benefits multi-task world models, broader comparisons with general-purpose MoE architectures remain an open direction for future work. Existing MoE variants are primarily designed for static, non-temporal supervised learning and do not incorporate mechanisms for recurrent latent dynamics or sequential prediction. In contrast, MoE-World explicitly operates on temporally structured objectives and decouples the learning of states, rewards, and terminations. Conducting a full comparison would require adapting conventional MoE designs to support temporal routing and world-model dependencies, which we plan to address in future work.

Looking ahead, extending MoE-World to dynamic environments, exploring heteroscedastic uncertainty to enable more nuanced loss balancing, and evaluating the architecture in continuous control, robotic control, or 3D simulation settings may further test its generalization capabilities. Additionally, analyzing the learned gating behavior could provide insights into how modular world models share knowledge across tasks. Future work will explore these directions in embodied simulators and robotic control environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.T. and Y.L.; methodology, Y.L.; software, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.T. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, C.T., Y.W., W.H., and Q.Z.; supervision, Q.Y., X.Z., and W.Z.; project administration, Q.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Technology Innovation 2030—Major Projects (Grant No. 2022ZD0205000).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MoE | Mixture of Experts |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| POMDPs | Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes |

| IQM | Interquartile Mean % TLA & Three letter acronym % LD & Linear dichroism |

References

- Wei, Z.; Sun, T.; Zhou, M. LIRL: Latent Imagination-Based Reinforcement Learning for Efficient Coverage Path Planning. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, R.; Asfandiyarov, R.; Carballo, A.; Fujii, K.; Ohtani, K.; Takeda, K. Open-Vocabulary Predictive World Models from Sensor Observations. Sensors 2024, 24, 4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Zhang, Y.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zong, Z.; Feng, J.; Yuan, Y.; Su, H.; Li, N.; Sukiennik, N.; et al. Understanding World or Predicting Future? A Comprehensive Survey of World Models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 58, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Bai, Y.; Liang, X.; Li, G.; Gao, W.; Lin, L. Aligning Cyber Space with Physical World: A Comprehensive Survey on Embodied AI. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2025. early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.; Schmidhuber, J. Recurrent World Models Facilitate Policy Evolution. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31, 2455–2467. [Google Scholar]

- Micheli, V.; Alonso, E.; Fleureet, F. Transformers Are Sample-Efficient World Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2209.00588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training; OpenAI: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language Models Are Unsupervised Multitask Learners. OpenAI Blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Olivas, E.S.; Guerrero, J.D.M.; Martinez-Sober, M.; Magdalena-Benedito, J.R.; Serrano, L. Handbook of Research on Machine Learning Applications and Trends: Algorithms, Methods, and Techniquesl; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miuccio, L.; Riolo, S.; Samarakoon, S.; Bennis, M.; Panno, D. On Learning Generalized Wireless MAC Communication Protocols via a Feasible Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning Framework. IEEE Trans. Mach. Learn. Commun. Netw. 2024, 2, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazimeh, H.; Zhao, Z.; Chowdhery, A.; Sathiamoorthy, M.; Chen, Y.; Mazumder, R.; Hong, L.; Chi, E.H. Dselect-k: Differentiable Selection in the Mixture of Experts with Applications to Multi-Task Learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 29335–29347. [Google Scholar]

- Kudugunta, S.; Huang, Y.; Bapna, A.; Krikun, M.; Lepikhin, D.; Luong, M.T.; Firat, O. Beyond Distillation: Task-Level Mixture-of-Experts for Efficient Inference. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.03742. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, Z.; Yi, X.; Chen, J.; Hong, L.; Chi, E.H. Modeling Task Relationships in Multi-Task Learning with Multi-Gate Mixture-of-Experts. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (KDD ’18), London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1930–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhao, M.; Gong, X. Progressive Layered Extraction (PLE): A Novel Multi-Task Learning Model for Personalized Recommendations. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Virtual Event, Brazil, 22–26 September 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedus, W.; Zoph, B.; Shazeer, N. Switch Transformers: Scaling to Trillion Parameter Models with Simple and Efficient Sparsity. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2022, 23, 5232–5270. [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme, C.; Puigcerver, J.; Mustafa, B.; Neumann, M.; Jenatton, R.; Pinto, A.S.; Keysers, D.; Houlsby, N. Scaling Vision with Sparse Mixture of Experts. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 8583–8595. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, B.; Riquelme, C.; Puigcerver, J.; Jenatton, R.; Houlsby, N. Multimodal Contrastive Learning with LiMoE: The Language-Image Mixture of Experts. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 9564–9576. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, L.; Babaeizadeh, M.; Milos, P.; Osinski, B.; Campbell, R.H.; Czechowski, K.; Erhan, D.; Finn, C.; Kozakowski, P.; Levine, S.; et al. Model-Based Reinforcement Learning for Atari. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1903.00374. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskin, M.; Srinivas, A.; Abbeel, P. CURL: Contrastive Unsupervised Representations for Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 13–18 July 2020; pp. 5639–5650. [Google Scholar]

- Yarats, D.; Kostrikov, I.; Fergus, R. Image Augmentation Is All You Need: Regularizing Deep Reinforcement Learning from Pixels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR, Vienna, Austria, 4 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, M.; Anand, A.; Goel, R.; Hjelm, R.D.; Courville, A.C.; Bachman, P. Data-Efficient Reinforcement Learning with Self-Predictive Representations. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2007.05929. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, A.; Gal, Y.; Cipolla, R. Multi-Task Learning Using Uncertainty to Weigh Losses for Scene Geometry and Semantics. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7482–7491. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, S.; Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor-Critic Methods. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 1587–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Jin, X.; Du, Y.; Zhang, N.; Hao, H. Adaptive Hard Parameter Sharing Method Based on Multi-Task Deep Learning. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Sun, J.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, G. Storm: Efficient Stochastic Transformer Based World Models for Reinforcement Learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 27147–27166. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).