Abstract

Accurate indoor floor classification is essential for wireless positioning systems. However, the performance of conventional received signal strength indictor (RSSI)-based fingerprinting approaches is often limited by signal fluctuations and insufficient feature representation. To address these challenges, this paper introduces a heterogeneous graph neural network (GNN) framework that models WiFi signals using two types of nodes: reference points and Media Access Control (MAC) address. The edges between reference points and MAC addresses are weighted by normalized RSSI values, allowing the model to capture signal strength interactions and perform relation-aware message passing. Through this graph-based representation, the model can learn spatial and signal dependencies more effectively than conventional vector-based approaches. The proposed model was extensively evaluated under both benchmark and practical settings. On small-scale datasets, it achieved performance comparable to that of a conventional convolutional neural network trained on large-scale datasets, confirming its effectiveness with limited samples. In addition, the proposed model consistently outperformed other models under noisy conditions, achieving 93.88% accuracy on the widely used UJIIndoorLoc dataset and 97.3% accuracy in real-time experiments conducted at a test site. These values are significantly higher than those achieved using conventional machine learning (ML) baselines, highlighting the ability of the proposed model to handle real-world signal variations. These findings highlight that the heterogeneous GNN effectively captures spatial and signal-level dependencies, offering a robust and scalable solution for accurate indoor floor classification. Overall, this work presents a promising pathway for improving the performance and reliability of future wireless positioning systems.

1. Introduction

Indoor localization plays a crucial role in diverse applications such as smart cities, smart healthcare, industry and logistics, sales and retail, travel and tourism, and public security [1]. In this context, the Global Positioning System (GPS) has been widely adopted for outdoor environments, where receivers operate passively by capturing satellite signals. However, owing to non-line-of-sight propagation, weak signal strength, and low positioning accuracy, GPS is not suitable for indoor applications [2]. Consequently, indoor environments require dedicated indoor positioning techniques capable of estimating user locations within buildings. Over the past decade, various technologies, algorithms, and methodologies have been proposed for indoor positioning, aimed at enhancing positioning accuracy and system reliability.

Indoor localization techniques can be divided into geometry-based ranging methods (e.g., time of arrival, time difference of arrival, and angle of arrival) and signal strength-based approaches [3,4]. Although ranging methods can achieve high accuracy, they typically require multiple synchronized reference nodes [5] or specialized antenna arrays [6], rendering their practical deployment challenging and expensive. Among signal strength-based methods, fingerprinting is a widely used approach that circumvents multipath effects by constructing a mapping between spatial locations and observable features such as WiFi, Bluetooth, or other radio-frequency signals [7]. In typical fingerprinting systems, received signal strength indicators (RSSIs) are collected at reference points (RPs) during the offline phase and used to train a pattern recognition algorithm. In the online phase, the trained algorithm estimates the user location based on newly observed RSSIs [8]. Notably, accurate estimation of the building and floor (for multi-building and multi-floor environments) is essential for reducing positioning errors [9]. The present work focuses on floor classification.

RSSI-based fingerprinting methods encounter several challenges: RSSI values are highly unstable owing to multipath propagation, shadowing, and device heterogeneity, resulting in inconsistent measurements even at the same location [10]. Conventional algorithms such as Bayesian inference [11], k-nearest neighbour (kNN) [12], and support vector machines [13] offer low computational complexity but remain sensitive to signal fluctuations, leading to unstable accuracy in practice. Recent advancements in deep learning have been explored to reduce computational complexity and storage, shorten training time, and mitigate RSSI fluctuations, thus addressing the limitations of traditional machine learning algorithms [14]. However, achieving high accuracy often comes at the cost of significant training overhead. Existing studies [9,15,16,17,18] have typically treated floor classification as an independent task, relying on conventional machine learning methods or additional hardware (e.g., barometers or channel state information). However, the performance of these techniques deteriorates when labelled data are limited.

Graph neural networks (GNNs) have emerged as powerful deep learning models for graph-structured and non-Euclidean data. Leveraging message-passing mechanisms, GNNs can effectively capture neighbourhood dependencies and learn expressive node and graph representations, achieving superior performance in node and graph classification tasks [19]. Recently, GNNs have been integrated into the FIS-ONE framework for indoor floor identification [20]. Moreover, IndoorGNN offers a supervised end-to-end classification approach by modelling WiFi RSSI vectors as homogeneous graph nodes with kNN-based dynamic edges [21]. Notably, most existing GNNs focus on homogeneous graphs with single-type nodes and edges, even though heterogeneous graphs contain richer structural and semantic information. Advances in heterogeneous graph [22] representation learning can effectively enhance the performance of complex network analysis [23].

To address the limitations of conventional fingerprinting methods in floor classification, this paper proposes a heterogeneous graph–based learning framework for floor classification. Instead of relying solely on raw RSSI vectors, the proposed approach transforms WiFi fingerprints into a heterogeneous graph and applies a graph convolutional network for relation-aware message passing. The feature representations associated with nodes are ultimately mapped to discrete floor predictions. Extensive experiments validate the effectiveness and practicality of the proposed framework. The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

- We propose a heterogeneous graph construction framework for floor classification, in which RPs and MAC addresses are explicitly represented as distinct node types connected through relation-specific edges. This formulation captures the multi-level dependencies inherent in WiFi fingerprinting data more effectively than traditional homogeneous graphs.

- Building on this structure, we develop a novel heterogeneous graph neural network (HeteroGNN) that introduces edge-type-conditioned message passing on a heterogeneous graph. This design enhances the discriminative capability of nodes.

- We perform a comprehensive comparison with conventional convolutional neural networks (CNNs), showing that the proposed approach maintains strong robustness even on small datasets. The model shows robust noise resistance. Moreover, the proposed method is computationally efficient, requiring less training time and memory than CNNs, while achieving the smallest peak memory footprint among all evaluated models.

- In addition, the proposed method outperforms conventional homogeneous GNNs on the UJIIndoorLoc dataset. It also consistently outperforms traditional machine learning methods such as Random Forest, AdaBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost.

The remaining paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work in indoor localization and floor classification. Section 3 describes the experimental environment, data collection, and preprocessing. Section 4 outlines the proposed methodology, detailing the heterogeneous graph construction and HeteroGNN model. Section 5 presents the experimental results and provides a comprehensive comparison with baseline methods. Finally, Section 6 presents the concluding remarks and highlights potential directions for future research.

2. Related Work

First, we provide an overview of studies incorporating floor classification as a component of broader localization systems. Next, we focus on the limited studies that address floor classification directly, highlighting the contribution of the present study to the broader research domain.

2.1. Indoor Localization Systems Incorporating Floor Classification

Liu et al. [24] proposed an integrated indoor positioning approach that combined WiFi-aided magnetic field fingerprints and pedestrian dead reckoning (PDR), achieving a 93% floor detection accuracy. Mashuk et al. [25] integrated WiFi and Bluetooth fingerprinting with PDR to detect building occupancy patterns and demonstrated the feasibility of this approach. Hassen et al. [26] introduced a multi-floor pedestrian navigation service combining PDR with WiFi fingerprinting for positioning and validated its performance in a university building. Hao et al. [27] proposed a multi-floor localization method that combined multi-sensor fusion with WiFi fingerprinting and PDR. Luo et al. [28] introduced a multi-floor 3D target tracking system, which leveraged improved particle filtering and a combination of Kalman filtering with a floor-change detection algorithm to reduce cumulative errors in PDR trajectories. Zhou et al. [29] established a multi-floor localization method that fused visual images, WiFi, and LiDAR, achieving an average 3D localization error of 0.62 m and a floor accuracy of 89.22%. Shi et al. [30] reported a multi-floor localization system integrating smartphone sensors, pedestrian network matching, and Bi-LSTM, which achieved reliable and precise positioning in large-scale urban buildings [30]. In addition to multisensor fusion methods, a number of studies have leveraged machine learning techniques together with Wi-Fi RSSI fingerprints to jointly perform indoor localization and floor identification. Yan et al. [31] used an ensemble Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) preprocessing and floor-wise data partitioning to achieve more than 98% floor accuracy in a five-floor environment. Li et al. [32] proposed a hierarchical stagewise DNN framework that reduces 3-D localization error to 7.98 m. Overall, while various researchers have demonstrated effective multi-floor localization through sensor fusion and network matching, few studies have examined floor classification as an independent research focus, as discussed in Section 2.2.

2.2. Dedicated Indoor Floor Classification Approaches

Existing studies have primarily focused on floor classification as a secondary component within larger indoor localization systems, with dedicated research on it as a standalone task being notably scarce. Among representative work, Quezada-Gaibor et al. [9] introduced a lightweight hybrid model for WiFi-based indoor localization, combining a CNN for feature extraction with an extreme learning machine for classification. Their model achieved high accuracy while reducing testing time by up to 58%, making it suitable for devices with limited computational resources. Zhuo et al. [20] proposed FIS-ONE in 2023, a floor identification system using crowdsourced signals with only one labelled sample. Incorporating an attention-based GNN, their method improved performance by up to 23% in adjusted rand index and 25% in normalized mutual information over baselines. Xie et al. [16] proposed TransFloor, a system combining barometer-based and WiFi-based modules for crowdsourced delivery localization, achieving an average accuracy of 94.61%. Recently, Wu et al. [17] introduced a Bluetooth low energy beacon–based floor detection solution for a multi-floor lab [17]. This system used a mean filter to mitigate RSSI fluctuations, achieving an accuracy of 0.9877. However, it required the deployment of additional beacons. Ou et al. [18] developed Codar, a complex-valued LSTM–CNN that used channel state information to detect cross-floor intrusions. While this model exhibited high accuracy, its computational cost was not reported, and its hardware dependency was expected to limit large-scale deployment. Several studies have further explored machine learning models using Wi-Fi RSSI fingerprints to address floor classification as an independent prediction task. Razavi et al. [33] applied a K-means-based fingerprint clustering method to reduce database complexity while maintaining floor-estimation accuracy comparable to NN fingerprinting. Luckner et al. [34] evaluated Wi-Fi-based floor detection in a suburban multi-storey building using a Random Forest classifier with AdaBoost.M2, achieving accuracies of up to 99%. Yang et al. [35] proposed a radial basis function (RBF)–based multi-floor localization method that improves floor classification robustness through supervised calibration and update. Shao et al. [36] proposed Wi-Fi Autonomous Block Models to perform large-scale floor identification, achieving floor-level accuracies above 97% across multiple real-world buildings. Overall, while dedicated floor-classification methods have shown promise, most rely on conventional techniques or specific hardware and struggle to maintain high performance with limited data. This highlights the need for a more comprehensive solution that balances accuracy, computational efficiency, and hardware independence, which is the motivation for the present study.

3. System Design and Data Collection

This section describes the proposed floor-classification system, including the experimental environment, setup, hardware and software configurations, data collection methods, database structure, and complete floor-classification workflow.

3.1. Environment and Experimental Setup

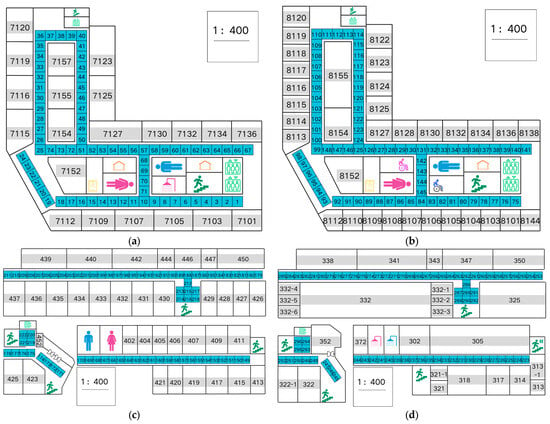

This study adopted the Communication Research Laboratory (CRL) database, established at Dongguk University, Seoul Campus. RSSI fingerprint data collection and real-time localization experiments were conducted within two academic buildings. A total of 296 RPs were defined, with 74 RPs per floor across four floors. Each RP block measured approximately 2 m × 2 m, with an inter-RP spacing of 4 m. As shown in Figure 1, the experimental environment included the 7th and 8th floors of the New Engineering Building and 3rd and 4th floors of Wonheung Hall.

Figure 1.

Floor plans of the experimental environment spanning multiple buildings and floors: (a) 7th and (b) 8th floors of the New Engineering Building; (c) 3rd and (d) 4th floors of Wonheung Hall. The blue colored areas indicate the RPs.

The RPs were numbered as follows: New Engineering Building 7th floor (RPs 1–74) and 8th floor (RPs 75–148), and Wonheung Hall 4th floor (RPs 223–296) and 3rd floor (RPs 149–222). Figure 1 also illustrates the spatial layout of the indoor test environment, which comprises two areas with distinct geometric characteristics. Figure 1a,b correspond to a regular rectangular region measuring 45 × 34 m, where 74 RPs were uniformly distributed on each floor. In contrast, Figure 1c,d represent an elongated and less regular floor layout with overall dimensions of 106 × 90 m, also configured with 74 uniformly arranged RPs per floor, but spanning a considerably larger spatial extent.

3.2. Hardware and Software Configurations

Hardware: An MSI GE75 laptop (MSI, New Taipei City, Taiwan) was used as the server for data processing. A custom-built robot was used for data collection and real-time localization. The robot included a Jetson Nano B01 (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA), a dual-band wireless network card, a display screen, a cooling fan, a ROS robotic driver board, motors with encoders, a tracked chassis, a battery, and a firmware base module, along with other essential components.

Software: The robot operated on Ubuntu 18.04 with Python 3.11.7. The server ran TensorFlow 2.14.0 and Python 3.11.7 on an Intel Core i7-8700K @ 3.70 GHz CPU and NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 Ti GPU. In terms of software functionality, the robot incorporated a custom-designed RSSI data collection program, while the server executed the data preprocessing module, a heterogeneous GNN-based floor classification program, and a real-time floor classification program.

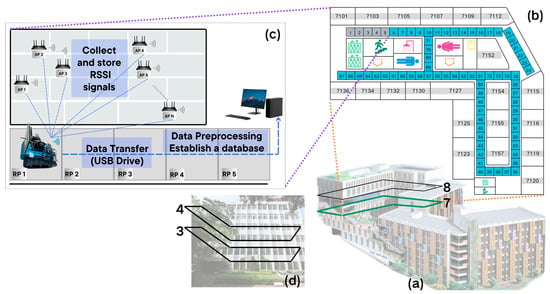

Figure 2 offers a clearer visualization of the localization scenario. Specifically, Figure 2a,d illustrate the New Engineering Building and Wonheung Hall, respectively. Numerical indicators 3, 4, 7, and 8 denote the corresponding floor levels within each building. Figure 2b depicts the 7th floor of the New Engineering Building, while Figure 2c illustrates the experiment conducted on the 7th floor. During data acquisition, the robot collected RSSI signals from multiple Access Points (APs). These data were transmitted to the server for preprocessing and database construction. Notably, the robot sequentially moved from RP1 to RP74 to complete data collection. For real-time floor classification, the robot collected RSSI signals from different APs at an unknown RP and transmitted them to the server, which performed real-time floor classification. The computed classification results were then displayed on the computer.

Figure 2.

Visualization of the localization scenario: Building layouts of the (a) New Engineering Building and (d) Wonheung Hall; (b) floor plan of the 7th floor in the New Engineering Building; and (c) data collection on the 7th floor.

3.3. Robot-Assisted Data Collection

The robot was remotely controlled, and a specialized program was run to initiate data collection. Once executed, the program automatically collected RSSI data for a predefined number of samples. Each data file contained the MAC addresses and corresponding RSSI values of all detectable WiFi signals at the given RP. The collected data were then automatically saved in a text (.txt) file within a designated folder. Following data collection, the program entered a verification phase. If a .txt file was found to be empty, it was automatically deleted, and a new file was generated at the same location. If the file contained data, the program was terminated. The data collection process explicitly considered temporal variations in RSSI measurements, defining the morning as 0:00–12:00 and the afternoon as 12:00–24:00. To capture potential time-of-day effects, data were collected independently in both periods. Moreover, the entire data collection campaign was conducted over a continuous period of four days.

After data collection, data preprocessing was performed, followed by the generation of the RSSI database. The database consisted of four main components: Floor Labels, Location Labels (representing RPs), MAC Addresses, and RSSI Values. The first column contained the floor labels, which were categorized into four levels: 3rd, 4th, 7th, and 8th. Similarly, the second column contained location labels, ranging from 1 to 296, with 74 locations per floor. The first row represented the MAC addresses, while the lower-right section of the table contained the RSSI values. The database was stored as an .xlsx file using Microsoft Excel.

3.4. Classification Workflow

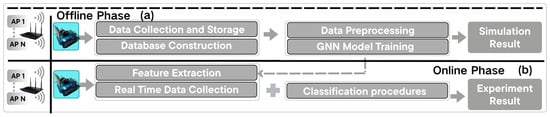

Figure 3 illustrates the robot-assisted WiFi-based floor classification system using a heterogeneous GNN. The operational workflow consisted of two main phases: offline training and online real-time localization.

Offline Phase:

- RSSI Data Collection: The robot sequentially collected RSSI signals and floor information from all available APs at each RP to construct the RSSI database.

- Data Preprocessing and Model Training: Prior to being input into the heterogeneous GNN for training, the collected data underwent preprocessing. The heterogeneous GNN was trained to perform floor classification based on the processed RSSI data.

Online Phase (Real-Time Floor Classification):

- Real-Time RSSI Data Acquisition: The robot scanned nearby WiFi signals and transmitted the data to the server. During this process, it recorded the floor information along with the MAC addresses and corresponding RSSI values.

- Graph Construction: A heterogeneous graph was constructed using MAC and RP nodes, with edge features encoding their multi-level relationships. This structured representation served as the input to the heterogeneous GNN model.

- Heterogeneous-GNN-Based Floor Classification: The constructed heterogeneous graph was fed into the pre-trained heterogeneous GNN to perform floor-level classification. The system output the predicted floor label in real time.

This structured workflow enabled efficient and accurate floor classification through a heterogeneous-GNN-based approach.

Figure 3.

Workflow of the robot-assisted WiFi-based floor classification system using heterogeneous GNN: (a) Offline phase. (b) Online phase.

4. Methodology

4.1. Graph-Based Modelling of RSSI Data

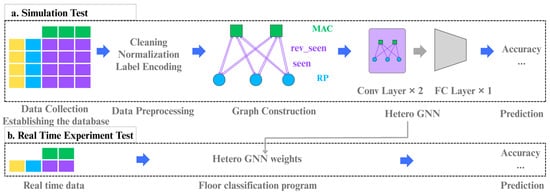

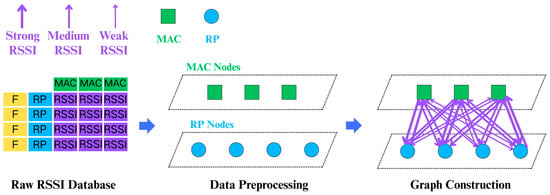

We modelled the RSSI fingerprinting problem as a classification task on a heterogeneous graph. Unlike approaches that directly use raw RSSI vectors, the proposed method explicitly constructed multiple types of nodes and edges, allowing the model to capture the multi-level relationships inherent in WiFi signal strength and spatial structure. Figure 4 illustrates the overall framework of the proposed heterogeneous-graph-based approach for RSSI fingerprinting, divided into (a) simulation test and (b) real-time experiment test.

Figure 4.

Two-stage framework for floor classification using a heterogeneous graph.

The process began with data preprocessing. Invalid RSSI values and those equal to 0 were discarded, and only signals within the [0, 100] range were retained. RP and MAC addresses were converted into a uniform string format for consistent numbering. This preprocessing yielded two distinct node sets for graph construction: RPs, representing the sampled locations, and MACs, indicating individual WiFi MAC addresses.

Following preprocessing, we constructed a heterogeneous graph with two node types: RPs and MACs. RP–MAC edges were created whenever an RP observed a given MAC, modelled as two directed relations: RP→ MAC (‘seen’) and MAC →RP (‘rev_seen’). Edge weights were defined as the corresponding RSSI values linearly normalized to [0, 1]. Formally, the heterogeneous graph was defined as , where denotes the set of nodes, with representing RPs and representing MACs; and denotes the set of directed edges. The overall process is illustrated in Figure 5, and the detailed procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Heterogeneous graph construction | ||

| Require: Long table with tuples (, , ) (concatenated from train and test); bounds [, ] | ||

| Ensure: Heterogeneous where = and | ||

| 1. | Filter invalid/zero | |

| 2. | Extract node sets | |

| 3. | Map each | Assign IDs |

| 4. | Edges → | |

| 5. | Edges → | |

| 6. | for | |

| 7. | Combine edges | |

| 8. | return | Final heterogeneous graph |

Figure 5.

Schematic of heterogeneous graph construction, consisting of RP, MAC, and floor nodes, with weighted edges.

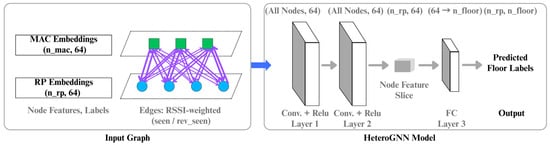

4.2. Heterogeneous GNN

For floor classification, we implemented a heterogeneous GNN model. The model architecture is illustrated in Figure 6, displaying its components from node embedding to final classification. The model began with a node embedding layer, where each RP and MAC node was assigned a 64-dimensional trainable embedding. All initial embeddings were parameterized using a standard initialization method. Feature propagation and aggregation were performed using two graph convolution layers. These layers were designed to maintain independent parameters for different edge types, enabling relation-aware message passing across the heterogeneous graph. The message-passing rules were defined as follows: For RP– MAC edges, RSSI edge weights were used to propagate signal features between RP and MAC nodes. Upon completion of the two-layer message passing, the aggregation and classification phase commenced. Hidden representations of the RP nodes, indicating the nodes for which we aimed to predict floor labels, were extracted. A single fully connected (Linear) layer was then applied to these RP node representations to perform the final classification, which yielded the predicted floor labels. Detailed operations of the proposed model are summarized in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 HeteroGNN for floor classification | ||

| Require: Heterograph with node types , edge types , and edge weights | ||

| Require: #classes , embedding dim , hidden dim h, epochs , #bases | ||

| Require: RP labels ; RP masks | ||

| Ensure: Trained parameters ; RP logits | ||

| 1. | Initialize learnable embeddings , | |

| 2. | Define and | |

| 3. | Define linear head | =nn.Linear |

| 4. | Convert G to homogeneous graph with node-type vector and edge-type vector ; carry | |

| to homogeneous(…, edata=[’’], store_type=True) | ||

| 5. | function FORWARD | |

| 6. | Build by scattering rows of , onto nodes of by | |

| 7. | ||

| 8. | ||

| 9. | slice RP nodes only | |

| 10. | return | |

| 11. | end function | |

| 12. | Training | |

| 13. | for to do | |

| 14. | FORWARD | |

| 15. | CE | CrossEntropy on RP train mask |

| 16. | Update with Adam step on | opt over embeddings+ + |

| 17. | Compute on and on | |

| 18. | end for | |

| 19. | return , | |

Figure 6.

Architecture of the proposed heterogeneous GNN model.

4.3. Training and Evaluation

4.3.1. Training Setup

The heterogeneous GNN model was trained with parameters defined to optimize its performance for floor classification. The loss function was cross-entropy loss, a standard choice for multi-class classification. The Adam optimizer was used with a learning rate of and weight decay of to prevent overfitting. The data split for training and validation was performed on the RP nodes within the training set, with 80% allocated for training and 20% for validation using stratified sampling to preserve class distributions. The model was trained for 50 epochs, with the training and validation accuracies reported every five epochs to monitor progress.

4.3.2. Evaluation

The trained model was applied to the dedicated test set to predict floor labels for RP nodes. Model performance was assessed using two primary evaluation metrics: floor classification accuracy, indicating the proportion of correctly predicted floors; and a classification report, which provided more detailed insights, including precision, recall, and F1-score for each floor class. This evaluation scheme helped comprehensively assess the model performance in classifying floor locations.

As detailed in Section 5, the proposed model was compared against two baseline models, CNN and HomoGNN, using both the self-collected CRL database and public UJIIndoorLoc dataset. In addition, the five traditional machine learning classifiers— Random Forest, AdaBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost—were also evaluated on the UJIIndoorLoc dataset for comparison.

5. Numerical Results

This section presents a detailed analysis of the experimental results for the proposed HeteroGNN. We first describe the experimental setup, including the datasets and evaluation metrics. Next, we compare the performance of HeteroGNN with two baseline models, CNN and HomoGNN, across different tasks, and discuss the implications of the results.

5.1. Dataset and Model Description

To benchmark the performance of the proposed HeteroGNN model, we constructed a dedicated dataset for the experiments. As described in Section 3, the experimental environment consisted of four floors with 296 RPs and 1533 MAC addresses. Multiple measurements were conducted at each RP, yielding 8880 samples. Each sample contained the floor label, RP identifier, and set of visible MAC addresses with their corresponding RSSI values. These samples were subsequently partitioned into training and testing subsets of different sizes for simulation-based evaluation. For computational convenience, the raw RSSI values (originally measured in dBm) were transformed into a positive scale by subtracting their absolute values from 100 (i.e., 100 − |RSSI in dBm|). Table 1 lists the characteristics of the constructed CRL database.

Table 1.

Characteristics of CRL database.

To assess the generalizability of the proposed model, it was evaluated on the public UJIIndoorLoc dataset [37]. This dataset contains 21,048 records collected from three multi-floor buildings at Universitat Jaume I, Spain. It includes 933 RPs and more than 500 attributes, of which 520 represent WiFi RSSI measurements from different APs. The training and validation sets contain 19,937 and 1111 samples, respectively, spanning multiple floors across the three buildings. These characteristics make UJIIndoorLoc a widely adopted benchmark for multi-building and multi-floor indoor localization.

Among baselines, the CNN model was adapted from the architecture proposed by Sinha et al. [38] for indoor positioning, modified for floor classification. The model consisted of three convolutional layers, each followed by a dropout layer to prevent overfitting. The layers incorporated 32, 64, and 128 filters with a kernel size of 3 × 3, and the model included max-pooling layers to reduce dimensionality. The input data were reshaped into 40 × 40 single-channel images, suitable for the CNN architecture. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer and sparse categorical cross-entropy loss, with a constant learning rate of 0.001.

The HomoGNN was inspired by the work of Vishwakarma et al. [21], in which WiFi MAC addresses were modelled as nodes in a static graph. In our implementation, a static weighted graph was constructed with MAC addresses as nodes, with edges reflecting their correlation based on an RSSI threshold. The adjacency matrix was normalized and symmetrized, and both the original and propagated features were concatenated and passed to a multi-layer perceptron for classification. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer and cross-entropy loss.

5.2. Simulation and Experimental Results

5.2.1. Performance Evaluation Across Different Dataset Scales

To evaluate the scalability and robustness of the proposed model, we conducted experiments across datasets of varying sizes. Table 2 lists the classification accuracies achieved using the CNN, HomoGNN, and HeteroGNN models, trained on subsets of varying size (N = 100–5000 samples per floor). As the simulations and experiments required a larger dataset than that available, data augmentation algorithms [38] were applied for N > 1000. As expected, the performance of all models improved with the increase in training data. Although the CNN achieved moderate accuracy with smaller datasets (e.g., 36.5% with 100 samples), its performance significantly improved as the data size increased, reaching above 97% with 5000 samples. In contrast, the HomoGNN consistently exhibited high accuracy even with limited data, achieving over 91% accuracy with only 100 samples and maintaining above 98% on larger datasets. Notably, HeteroGNN demonstrated the best overall performance, achieving high floor-classification accuracy even with small datasets. Overall, the GNN-based models (HomoGNN and HeteroGNN) outperformed the CNN, especially when training data was scarce. The CNN required a larger dataset to achieve comparable accuracy. HeteroGNN consistently outperformed the other models, highlighting its effectiveness in capturing complex relationships within the data.

Table 2.

Model performance across multiple datasets with different sample sizes.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed models in real-world settings, we conducted a real-time experiment by randomly selecting a range of samples from 100 to 5000, distributed across the four floors in the test environment. Each neural network model was trained offline on the prepared dataset and subsequently deployed to perform floor classification under live conditions. The results are summarized in Table 2. The CNN achieved an average classification accuracy of 95.7%, with the HomoGNN displaying a slightly higher value of 96.1%. HeteroGNN demonstrated the best overall performance, attaining 97.3% accuracy in the real-time experiment. These findings highlight the effectiveness and practical applicability of GNN-based models, especially HeteroGNN, in real-world indoor floor classification under noisy and dynamic wireless conditions.

5.2.2. Model Size and Parameter Comparison

To further assess the efficiency of the models, we analysed their sample complexity and parameter sizes (Table 3). The results highlight significant differences in the amount of training data required to achieve high performance. The CNN model required approximately 4800 training samples to reach 97% accuracy, with a network size of 13.2 M trainable parameters. Even at a lower accuracy target of 95%, the CNN still required approximately 3000 samples, indicating high data dependency. In contrast, HomoGNN achieved 97% accuracy with only 450 samples and 0.28 M parameters, while 200 samples were sufficient to reach 95%. HeteroGNN demonstrated the highest sample efficiency, attaining 97% accuracy with only 95 samples and maintaining strong performance with a compact model size of 0.15 M parameters. These findings indicate that GNN-based models, particularly HeteroGNN, are considerably more sample-efficient and lightweight than the CNN. These features represent critical advantages in real-world applications, where data collection can be costly or challenging.

Table 3.

Sample complexity and network size.

The results in Table 4 show substantial differences in computational demands: the CNN exhibited markedly higher training time and memory usage, while both GNN-based models were able to achieve faster training and substantially lower memory consumption. Although HeteroGNN was not the fastest model in terms of total training time, it still maintained a highly competitive computational profile with the smallest peak memory footprint among all evaluated architectures.

Table 4.

Comparison of training time and peak memory consumption across different neural network models.

5.3. Robustness to Noise

The use of different sensing devices (i.e., user terminals) may also affect the performance of indoor localization methods. Lu et al. [39] demonstrated that using a robot versus a smartphone for collecting Wi-Fi RSSI fingerprints can lead to noticeably different positioning results, with the robot-assisted system achieving higher accuracy under identical processing pipelines. In our study, we used a consistent sensing device—the robot platform.

To evaluate the robustness of the models against signal fluctuations, controlled noise was introduced into the RSSI data. Specifically, noise was simulated by adding a random variable, drawn from a uniform distribution, to a subset of the RSSI measurements. This procedure was applied consistently to both the training and testing datasets, with each model being trained and evaluated on the same dataset size (N = 5000) per floor. According to the noise analyses reported in [40,41,42], introducing controlled RSSI perturbations is a widely adopted approach in fingerprinting-based localization, and noise levels of up to ±5 dB were therefore considered in our study to reflect typical variations observed in indoor wireless environments. For each noise level, 1000 RSSI values were randomly selected and perturbed from the training dataset of each floor, ensuring a reproducible assessment of robustness.

As outlined in Table 5, the CNN exhibited gradual performance degradation as the noise increased, with accuracy dropping from 97.3% at 0 dB to 96.3% at 5 dB. HomoGNN demonstrated greater stability, maintaining accuracies exceeding 97.0% across all noise levels. HeteroGNN achieved the highest robustness, sustaining near-perfect performance with 99.7% accuracy at 0 dB and 98.9% at 5 dB. These findings highlight that GNN-based approaches, particularly HeteroGNN, are highly resilient to realistic signal variations, underscoring their suitability for deployment in practical indoor environments.

Table 5.

Model performance under varying noise conditions.

5.4. Cross-Dataset Evaluation (UJIIndoorLoc)

As shown in Table 6, to establish a fair baseline, we reproduced the HomoGNN model using the official source-code [21] implementation reported in the original work. The reproduced HomoGNN achieved 89.3% classification accuracy on the same dataset. In contrast, the conventional CNN achieved 87.1%. Notably, HeteroGNN outperformed both baselines, achieving a classification accuracy of 93.9%. As presented in Table 7, for a more comprehensive comparison across different classes of models, we additionally implemented several widely used machine learning classifiers on the UJIIndoorLoc dataset. Specifically, Random Forest, AdaBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost were evaluated under the same experimental settings, achieving classification accuracies of 91.2%, 71.7%, 89.0%, 90.1%, and 87.1%, respectively. These results further confirmed that the proposed HeteroGNN still achieved superior performance compared with a wide range of machine learning models.

Table 6.

Neural network model performance on the UJIIndoorLoc dataset.

Table 7.

Ensemble model performance on the UJIIndoorLoc dataset.

To comprehensively assess model performance, we compiled a classification report (Table 8), which provided detailed insights. HeteroGNN consistently demonstrated superior performance across all metrics, achieving a higher F1-score [43] and recall [43] for nearly every category. Although HomoGNN displayed a significant improvement over the baseline CNN, its performance was less robust, particularly for classes 0 and 4, where its F1-scores were lower. These results indicate that the heterogeneous graph structure effectively captures complex relationships within the data, leading to more balanced and accurate classification across all categories. In addition, as illustrated in Table 9, the evaluation of several representative machine learning classifiers (Random Forest, AdaBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost) showed notably lower performance, particularly on classes 0 and 4, further underscoring the stronger category-level consistency and discriminative capacity achieved by the proposed HeteroGNN.

Table 8.

Comparative analysis of F1-score and recall of neural network models on the UJIIndoorLoc dataset.

Table 9.

Comparative analysis of F1-score and recall of ensemble models on the UJIIndoorLoc dataset.

6. Conclusions

We established a novel heterogeneous GNN (HeteroGNN) for indoor floor classification. This approach explicitly modelled the relationships among RPs and MAC addresses as a heterogeneous graph. Extensive experiments were conducted to evaluate our GNN-based models against a conventional CNN and HomoGNN on two distinct datasets: our custom CRL database and the public UJIIndoorLoc database. HeteroGNN frequently demonstrated superior performance over the CNN and HomoGNN. Specifically, the proposed model achieved a classification accuracy of 93.88% on the UJI dataset. Its effectiveness was further validated in a real-time experiment on an unseen subset of the CRL database, where it achieved a high classification accuracy of 97.3%. Moreover, HeteroGNN demonstrated strong robustness to noise and maintained high accuracy even with small-scale samples, requiring only one-tenth of the data required by the CNN. It also offered clear computational advantages, including faster training and a substantially smaller memory footprint compared with the CNN-based baseline. In addition, the proposed model outperformed five traditional machine learning classifiers—Random Forest, AdaBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost—on the UJIIndoorLoc dataset, further confirming its strong discriminative capability. Overall, these results underscore the advantages of using heterogeneous graph structures to capture the complex relational features of WiFi RSSI data. The proposed framework, outperforming both CNN-based methods and homogeneous GNNs, offers a practical solution for scenarios where data collection is costly and signals are unstable. Future work will be aimed at exploring alternative graph designs and large-scale deployment to further enhance the capabilities of the proposed framework.

Author Contributions

H.L. and S.-H.H. served as the primary investigators. H.L. led data collection and computational tasks, including code development, simulations, and experiments. S.-H.H. was responsible for research design and supervision, providing guidance throughout the project. Numerical findings were mutually verified by H.L. and S.-H.H. Both authors contributed to preparing, reviewing, revising, and finalizing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Farahsari, P.S.; Farahzadi, A.; Rezazadeh, J.; Bagheri, A. A survey on indoor positioning systems for IoT-based applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 7680–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, N.H.; Sunar, N.; Ariffin, S.H.; Wong, K.Y.; Aun, Y. Indoor positioning system: A review. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Qu, W.; Qiu, T.; Zhao, L.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Wu, D.O. Indoor intelligent finger-print-based localization: Principles, approaches and challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2020, 22, 2634–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.; Moon, S.; Chu, M.; Bae, S.; You, C.; Liu, H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, D.J.; et al. Performance analysis of 3D localization for a launch vehicle using TOA, AOA, and TDOA. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2018, 103, 1443–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazik, P.; Rajagopal, N.; Sinopoli, B.; Rowe, A. Ultrasonic time synchronization and ranging on smartphones. In Proceedings of the 21st IEEE Real-Time and Embedded Technology and Applications Symposium, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–16 April 2015; pp. 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, K.J.; Lee, S.; Jang, B.J. AoA-based local positioning system using a time-modulated array. J. Electromagn. Eng. Sci. 2017, 17, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Alexander, I.; Lai, C.; Wu, P.Y.; Wu, R.B. Optimization and evaluation of multi-detector deep neural network for high-accuracy Wi-Fi fingerprint positioning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 15204–15214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabati, M.; Ghorashi, S.A. A real-time fingerprint-based indoor positioning using deep learning and preceding states. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 118889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada-Gaibor, D.; Torres-Sospedra, J.; Nurmi, J.; Koucheryavy, Y.; Huerta, J. Lightweight hybrid CNN-ELM model for multi-building and multi-floor classification. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Localization and GNSS (ICL-GNSS), Tampere, Finland, 7–9 June 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, M.T.; Yuen, B.; Dong, X.; Lu, T.; Westendorp, R.; Reddy, K. Re-current neural networks for accurate RSSI indoor localization. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 10639–10651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.; Einahrawy, E.; Martin, R.P.; Ju, W.H.; Krishnan, P.; Krishnakumar, A.S. Bayesian indoor positioning systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings IEEE 24th Annual Joint Conference of the IEEE Computer and Communications Societies, Miami, FL, USA, 13–17 March 2005; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 1217–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zhang, B.; Li, C. A feature-scaling-based k-nearest neighbor algorithm for indoor positioning systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2015, 3, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.L.; Fu, L.C.; Lian, F.L. WLAN location determination in e-home via support vector classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control, Taipei, Taiwan, 21–23 March 2004; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Volume 2, pp. 1026–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Nessa, A.; Adhikari, B.; Hussain, F.; Fernando, X.N. A survey of machine learning for indoor positioning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 214945–214965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.S. Automatic building and floor classification using two consecutive multi-layer perceptron. In Proceedings of the 2018 18th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), Pyeongchang, Republic of Korea, 17–20 October 2018; pp. 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Luo, H.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, H.; Zhao, F.; Li, Z.; Ye, Q.; Rong, B.; Gao, J. TransFloor: Transparent floor localization for crowdsourcing instant delivery. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2023, 6, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, H.; Roddelkopf, T.; Thurow, K. BLE beacon-based floor detection for mobile robots in a multi-floor automation laboratory. Transp. Saf. Environ. 2024, 6, tdad024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, C. Codar: Complex-valued neural network for crossing-floor intrusion detection via WiFi. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025—2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Hyderabad, India, 6–11 April 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Shen, X.; Xia, S. GLoc: GNN in indoor localization. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 15090–15100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, W.; Chiu, K.H.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Z.; Chan, S.H.; Ha, S.; Lee, C.H. FIS-ONE: Floor identification system with one label for crowdsourced RF signals. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 43rd International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Hong Kong, China, 18–21 July 2023; pp. 418–428. [Google Scholar]

- Vishwakarma, R.; Joshi, R.B.; Mishra, S. IndoorGNN: A graph neural network based approach for indoor localization using WiFi RSSI. In International Conference on Big Data Analytics; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 150–165. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Zheng, Y.; Li, N.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Piao, J.; Quan, Y.; Chang, J.; Jin, D.; He, X.; et al. A survey of graph neural networks for recommender systems: Challenges, methods, and directions. ACM Trans. Recomm. Syst. 2023, 1, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, R.; Yuan, G.; Zhu, M.; Meng, F.; Ma, H.; Qiao, S. Heterogeneous graph neural networks analysis: A survey of techniques, evaluations and applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 8003–8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Motta, G.; Dong, J. Wi-Fi-aided magnetic field positioning with floor estimation in indoor multi-floor navigation services. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Congress on Internet of Things (ICIOT), Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Mashuk, M.S.; Pinchin, J.; Siebers, P.O.; Moore, T. A smart phone based multi-floor indoor positioning system for occupancy detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium (PLANS), Monterey, CA, USA, 23–29 April 2018; pp. 216–227. [Google Scholar]

- Hassen, W.F.; Najjar, F.; Nabi, M.A.; Kriaa, S.; Kosch, H.; Brunie, L. Multi-floor pedestrian navigation service based on a hybrid indoor positioning system. In Proceedings of the 2018 14th International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications (WiMob), Limassol, Cyprus, 15–17 October 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Z.; Dang, J.; Cai, W.; Duan, Y. A multi-floor location method based on multi-sensor and WiFi fingerprint fusion. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 223765–223781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C. Indoor multi-floor 3D target tracking based on the multi-sensor fusion. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 36836–36846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Xu, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, C. Multi-floor indoor localization based on multi-modal sensors. Sensors 2022, 22, 4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Teng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, R.; Li, Q. Autonomous multi-floor localization based on smartphone-integrated sensors and pedestrian indoor network. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Qi, G.; Kang, B.; Wu, X.; Liu, H. Extreme learning machine for accurate indoor localization using RSSI fingerprints in multifloor environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 14623–14637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kim, K.S.; Tang, Z.; Smith, J.S. Hierarchical Stage-Wise Training of Linked Deep Neural Networks for Multi-Building and Multi-Floor Indoor Localization Based on Wi-Fi RSSI Fingerprinting. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 25, 23341–23351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, A.; Valkama, M.; Lohan, E.S. K-means fingerprint clustering for low-complexity floor estimation in indoor mobile localization. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), San Diego, CA, USA, 6–10 December 2015; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Luckner, M.; Górak, R. Comparison of floor detection approaches for suburban area. In Asian Conference on Intelligent Information and Database Systems, Proceedings of the 8th Asian Conference, ACIIDS 2016; Da Nang, Vietnam, 16 March 2016, Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 782–791. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Yu, Y.; Li, B. Multi-floor indoor localization based on RBF network with initialization, calibration, and update. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 7977–7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Luo, H.; Zhao, F.; Tian, H.; Huang, J.; Crivello, A. Floor identification in large-scale environments with Wi-Fi autonomous block models. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 18, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sospedra, J.; Montoliu, R.; Martínez-Usó, A.; Avariento, J.P.; Arnau, T.J.; Benedito-Bordonau, M.; Huerta, J. UJIIndoorLoc: A new multi-building and multi-floor database for WLAN fingerprint-based indoor localization problems. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Busan, Republic of Korea, 27–30 October 2014; pp. 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, R.S.; Lee, S.M.; Rim, M.; Hwang, S.H. Data augmentation schemes for deep learning in an indoor positioning application. Electronics 2019, 8, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Hwang, S.-H. Robot-Assisted RSSI Data Collection for Indoor Fingerprint-Based Positioning. ICT Express 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, T.; Wang, W.; Tu, Z. Multiple fingerprints-based indoor localization via GBDT: Subspace and RSSI. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 80519–80529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sospedra, J.; Moreira, A. Analysis of sources of large positioning errors in deterministic fingerprinting. Sensors 2017, 17, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Z. FCLoc: A novel indoor Wi-Fi fingerprints localization approach to enhance robustness and positioning accuracy. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 23, 7153–7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).