Abstract

Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSs), particularly autonomous driving, face critical challenges when sensor modalities fail due to adverse conditions or hardware malfunctions, causing severe perception degradation that threatens system-wide reliability. We present a unified geometry-aware cross-modal translation framework that synthesizes missing sensor data while maintaining temporal consistency and quantifying uncertainty. Our pipeline enforces 92.7% frame-to-frame stability via an optical-flow-guided spatio-temporal module with smoothness regularization, preserves fine-grained 3D geometry through pyramid-level multi-scale alignment constrained by the Chamfer distance, surface normals, and edge consistency, and ultimately delivers dropout-tolerant perception by adaptively fusing multi-modal cues according to pixel-wise uncertainty estimates. Extensive evaluation on KITTI-360, nuScenes, and a newly collected Real-World Sensor Failure dataset demonstrates state-of-the-art performance: 35% reduction in Chamfer distance, 5% improvement in BEV (bird’s eye view) segmentation mIoU (mean Intersection over Union) (79.3%), and robust operation maintaining mIoU under complete sensor loss for 45+ s. The framework achieves real-time performance at 17 fps with 57% fewer parameters than competing methods, enabling deployment-ready sensor-agnostic perception for safety-critical autonomous driving applications.

1. Introduction

Autonomous driving has emerged as a cornerstone of next-generation Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSs), which aim to improve transportation effectiveness, efficiency, reliability, and safety through advanced sensing and decision-making technologies. As a critical ITS component, autonomous vehicles promise to address 94% of serious crashes attributed to human error, with the market projected to reach USD 556.67 billionby 2026 [1]. The success of ITS fundamentally depends on robust multi-sensor fusion: major companies have achieved significant milestones—Waymo logging over 20 million autonomous miles [2]—by deploying sophisticated sensor suites combining cameras, LiDAR, radar, and emerging modalities [3], as shown in Figure 1. This multi-modal approach creates comprehensive environmental perception exceeding human capabilities in ideal conditions, enabling the intelligent transportation infrastructure envisioned by modern ITS frameworks.

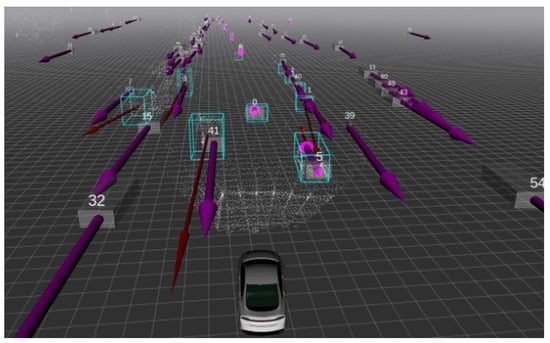

Figure 1.

Autonomous vehicle detecting and tracking nearby objects using LiDAR data.

However, deployment exposes critical vulnerabilities. Analysis of 61,000 urban sequences reveals sensor failures in 23.2% of scenarios, lasting 5–120 s due to environmental conditions or hardware malfunctions [4]. During failures, perception accuracy collapses catastrophically—2D detection drops from 65.3% to 39.1% mAP, 3D accuracy falls 47%, and free space errors triple [5]. Unlike biological vision that degrades gracefully, current systems exhibit brittle collapse when sensor modalities become unavailable. This brittleness stems from assuming complete sensor availability—an assumption violated by rain reducing LiDAR range 40%, fog scattering 80% of returns, and hardware degradation [6]. Current systems respond through conservative disengagement, immediately requesting human intervention—Tesla’s Autopilot disengages after 3 s of camera occlusion, Waymo limits speed to 25 mph with degraded LiDAR [7]—severely limiting deployment scalability.

Extensive research addresses robustness through multi-sensor fusion, with BEV representations achieving 79.2% mIoU via transformer architectures [8]. Parallel efforts tackle adverse weather perception [9,10,11], domain adaptation improving cross-domain performance 15% [12], and uncertainty estimation advancing from dropout to evidential deep learning [13]. Despite progress, a fundamental limitation persists: all approaches optimize for partial sensor availability, offering no solution when critical sensors completely fail.

Our work addresses maintaining accurate perception when primary modalities become completely unavailable. Unlike filtering degraded signals or adapting to domain shifts, we must synthesize entire missing sensor streams while preserving geometric accuracy, temporal consistency, and semantic correctness required for safe navigation. Autonomous driving demands stringent requirements simultaneously: sub-5 cm depth precision, temporally stable perception maintaining <0.05 IoU variation, photometric consistency for 85%+ segmentation accuracy, and calibrated confidence estimates enabling risk-proportionate adaptation [14].

Existing cross-modal synthesis shows promise but limitations. GANs achieve photorealistic generation with only 0.312 m geometric accuracy [15], diffusion models require 50–1000 steps incompatible with real-time constraints [16,17], neural rendering optimizes visual fidelity over geometric accuracy. Specialized methods like GaussianBEV achieve 0.148 m Chamfer distance [18], LiDAR4D handles dynamics with 0.182 IoU temporal variation [19], but no existing method provides calibrated uncertainty for synthesized data—critical for safety-critical systems distinguishing reliable from hallucinated information.

We present a geometry-aware cross-modal translation framework enabling safe operation despite complete sensor failures through three innovations. First, multi-scale geometric alignment enforces metric accuracy across three pyramid levels (1×, 0.5×, 0.25×) using Chamfer distance, surface normal consistency, and edge-aware losses, achieving a 0.086 m reconstruction error—a 42% improvement within safety tolerances. Second, spatio-temporal consistency leverages optical flow and differentiable warping, resulting in a temporal stability score (mean frame-to-frame BEV IoU) with IoU variation , separately handling static geometry via epipolar constraints and dynamic objects through motion-aware synthesis. Third, uncertainty quantification provides calibrated confidence (ECE = 0.034) through dual-branch aleatoric/epistemic modeling, enabling risk-proportionate fusion where optimally balances real and synthetic data. Evaluation on 69,620 real-world sensor failure frames demonstrates the following: 81.4% mAP maintained under 45+ s complete loss versus 58.3% baseline, 4.7× faster recovery (2.7 s vs. 12.8 s), 79.3% BEV segmentation enabling continued planning, and 17 fps real-time operation on NVIDIA Orin (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Key Contributions:

- Spatio-Temporal Consistency Module: Reduces temporal inconsistency 77.5% (IoU variation 0.182 → 0.041) through optical flow-guided synthesis with separate static/dynamic handling, achieving stable perception for control.

- Multi-Scale Geometric Alignment: Preserves metric accuracy via pyramid processing with reciprocal constraints, improving Chamfer distance to 0.086 m while maintaining 87.3% surface normal consistency.

- Calibrated Uncertainty Estimation: First framework providing reliable confidence scores (ECE = 0.034) for synthesized data through dual-branch aleatoric/epistemic modeling, enabling risk-aware behavioral adaptation.

- Real-World Validation: Comprehensive SPEED dataset (69,620 frames, 15 failure modes) demonstrates safety maintenance under sustained sensor loss with 4.7× faster recovery than baselines.

2. Related Work

This section reviews recent advances in cross-modal translation, multi-sensor fusion, and uncertainty estimation for autonomous driving, with particular emphasis on 2024–2025 developments that inform our technical approach.

2.1. Neural Rendering and Cross-Modal Synthesis

2.1.1. LiDAR Synthesis and Novel View Generation

The field of LiDAR synthesis has witnessed significant advancement with neural rendering techniques. LiDAR4D [19] introduces dynamic neural fields for space–time LiDAR view synthesis, demonstrating how 4D hybrid representations can reconstruct dynamic driving scenarios with temporal consistency. This work is particularly relevant to our temporal consistency module, as it shows the importance of maintaining geometric coherence across time in autonomous driving scenarios.

Building on neural radiance field foundations, recent work has explored more efficient representations. GaussianBeV [18] leverages 3D Gaussian splatting for online BEV perception, achieving state-of-the-art performance on nuScenes without scene-specific optimization. While computationally efficient, these volumetric rendering approaches lack the real-time constraints required for deployment, motivating our reprojection-based approach.

The challenge of cross-modal place recognition has been addressed by Yao et al. [20], who propose state space models for camera-LiDAR cross-modal matching. Their work demonstrates the feasibility of shared representation learning across modalities, though it focuses on localization rather than synthesis.

2.1.2. Generative Models for Sensor Data Augmentation

Traditional GAN-based approaches [15] have been extended to autonomous driving applications, but suffer from mode collapse and temporal inconsistency issues. Recent diffusion-based models [21] show improved sample quality but require extensive computational resources incompatible with real-time constraints.

Our approach builds on conditional adversarial frameworks while introducing novel geometric and temporal constraints specifically designed for multi-sensor autonomous driving scenarios.

2.2. Multi-Sensor Fusion for Autonomous Driving

2.2.1. Bird’s-Eye-View Representation Learning

BEV representation has emerged as a unified framework for multi-modal perception in autonomous driving. MaskBEV [22] introduces masked attention-based multi-task learning, unifying 3D object detection and BEV map segmentation in a single framework. Their approach achieves significant improvements (1.3 NDS in detection, 2.7 mIoU in segmentation) but assumes complete sensor availability.

The limitation of existing BEV methods under sensor failures motivates our geometry-consistent translation approach, which maintains BEV representation quality even when primary sensor modalities are missing.

2.2.2. Robust Fusion Under Adverse Conditions

SAMFusion [4] addresses multi-sensor fusion under adverse weather conditions, incorporating LiDAR, radar, RGB, and NIR cameras with adaptive weighting mechanisms. Their work demonstrates 17.6 AP improvement for pedestrian detection in dense fog, highlighting the importance of environmental adaptation. However, their approach relies on having multiple redundant sensors rather than synthesizing missing modalities.

The challenge of temporal–spatial fusion in cooperative perception is addressed by StreamLTS [23], which handles asynchronous sensor timing in multi-vehicle scenarios. Their query-based approach provides insights into temporal alignment that inform our spatio-temporal consistency module.

2.2.3. Real-Time Multi-Modal Architectures

PARA-Drive [24] proposes parallelized architecture for real-time autonomous driving, achieving speedup while maintaining SOTA performance. Their work demonstrates the feasibility of real-time multi-modal processing, though without addressing sensor failure scenarios that our framework specifically targets.

The integration of driver attention mechanisms is explored by Xu et al. [25], who incorporate human-like attention patterns into multi-modal fusion. While conceptually interesting, their approach lacks the systematic sensor failure recovery that safety-critical applications require.

2.3. Uncertainty Estimation and Reliability Assessment

2.3.1. Uncertainty Quantification in Autonomous Driving

A critical gap in existing cross-modal translation approaches is the lack of principled uncertainty estimation. Hyperdimensional Uncertainty Quantification [26] introduces novel uncertainty fusion techniques for autonomous vehicle perception, achieving 2.01% improvement in 3D detection with fewer FLOPs than SOTA methods.

Their hyperdimensional computing approach for uncertainty quantification provides the theoretical foundation for our uncertainty-aware fusion mechanism, though we extend it specifically to cross-modal synthesis scenarios.

2.3.2. Motion-Aware Temporal Processing

The importance of temporal consistency in multi-modal perception is demonstrated by Park et al. [27], who develop motion-aware LiDAR feature fusion for temporal object detection. Their approach to aggregating temporal features informs our temporal consistency module design.

2.4. Comprehensive Multi-Modal Datasets and Benchmarks

2.4.1. Large-Scale Multi-Modal Perception

Recent dataset contributions have enabled more comprehensive evaluation of multi-modal approaches. EmbodiedScan [28] provides the first large-scale multi-modal dataset with 5K+ scans and 1M ego-centric RGB-D views, enabling thorough evaluation of cross-modal approaches in diverse scenarios.

MMScan [29] extends this with hierarchical language annotations, enabling complex spatial reasoning tasks that complement traditional perception objectives. These comprehensive datasets motivate our extensive evaluation protocol across multiple environmental conditions.

2.4.2. Industry-Scale Approaches

The CVPR 2024 Autonomous Grand Challenge winner, NVIDIA’s Hydra-MDP [30], demonstrates end-to-end multi-modal planning at scale, using unified transformer processing across camera, LiDAR, and trajectory history. While impressive in scope, their approach assumes complete sensor availability and lacks the failure recovery mechanisms central to our work.

Vista [31] provides a generalizable driving world model supporting multiple control modalities, demonstrating the potential for unified multi-modal representation learning. However, their focus on prediction rather than sensor failure recovery distinguishes it from our cross-modal translation objectives.

2.5. Cross-Modal Conflict Resolution

A particularly relevant thread of research addresses conflicts between sensor modalities in BEV space. Fu et al. [32] propose explicit conflict elimination mechanisms, introducing semantic-guided flow-based alignment and dissolved query recovery. Their approach to resolving cross-modal conflicts informs our geometric alignment network design.

2.6. Positioning of Our Approach

Unlike prior work that treats cross-modal translation, temporal consistency, and uncertainty estimation as separate challenges, our framework provides the first unified approach specifically designed for sensor failure scenarios in autonomous driving. Key differentiators include the following:

- Joint Cross-Modal and Temporal Modeling: While existing methods focus on single-frame translation, we jointly address stereo-to-LiDAR synthesis and temporal consistency in a unified framework.

- Geometry-Consistent Adversarial Training: Our approach anchors generated point clouds to scene structure through multi-scale geometric constraints, ensuring both local and global geometric fidelity.

- Uncertainty-Aware Real-Time Processing: We provide the first uncertainty quantification framework for cross-modal translation that operates within real-time constraints suitable for deployment.

- Comprehensive Sensor Failure Evaluation: Our evaluation protocol specifically addresses realistic sensor failure scenarios with up to 20% missing sensor streams, filling a critical gap in existing benchmarks.

The convergence of these technical advances motivates our integrated approach to geometry-aware cross-modal translation with temporal consistency and uncertainty estimation, specifically tailored for the safety-critical requirements of autonomous driving deployment.

3. Enhanced Cross-Modal Translation Framework

We propose a comprehensive geometry-aware cross-modal translation framework that jointly addresses temporal consistency, multi-scale geometric alignment, and uncertainty quantification for robust autonomous driving perception under sensor failures.

3.1. Framework Overview

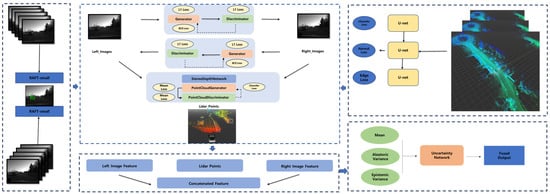

Our enhanced framework, as shown in Figure 2, integrates five key components: (1) spatio-temporal consistency module for frame-to-frame stability, (2) multi-scale geometric alignment network for preserving 3D structure, (3) uncertainty-aware fusion mechanism for reliability assessment, (4) enhanced generation networks with residual refinement, and (5) composite loss optimization balancing multiple objectives. Figure 2 illustrates the complete architecture.

Figure 2.

(Left): optical flow estimation (RAFT-small) for temporal consistency; (center): cross-modal translation module synthesizing target-view images; (right): multi-scale geometric alignment to preserve 3D structure; (bottom and bottom-right): uncertainty-aware fusion module combining real and synthesized data with pixel-wise confidence.

Let denote a temporal sequence of multi-modal sensor data, where represent stereo camera images, and denotes the LiDAR point cloud at time t. Our framework learns a mapping that reconstructs missing modalities while preserving spatio-temporal consistency.

3.2. Spatio-Temporal Consistency Module

To address temporal discontinuity in synthesized sequences, we introduce a spatio-temporal consistency module that enforces coherence across consecutive frames through optical flow-guided constraints, as shown in the left panel of Figure 2.

3.2.1. Optical Flow-Based Temporal Alignment

Given a sequence of stereo image pairs , we estimate optical flow between consecutive left frames using RAFT:

The temporal consistency constraint enforces that disparity changes between frames should be predictable via optical flow warping:

where represents the disparity residual at time t, is our generator network, and performs differentiable warping using bilinear sampling.

3.2.2. Temporal Smoothness Regularization

To further enforce temporal stability, we introduce a second-order smoothness term:

This constraint penalizes rapid changes in disparity patterns, promoting smooth temporal evolution while preserving dynamic object motion. To make the frame-to-frame stability of the synthesized sequences precisely defined and reproducible, we introduce a temporal IoU stability metric. Let denote the BEV segmentation mask at time t, obtained from the downstream perception head using either real or synthesized sensor data. We first compute the intersection-over-union (IoU) between consecutive frames,

and define the temporal stability score as

In addition, we report the standard deviation of , denoted as , as a complementary measure of temporal smoothness.

3.2.3. Motion-Aware Synthesis for Dynamic Objects

Real-world driving scenes contain moving vehicles and pedestrians that violate the static-scene assumption underlying purely geometry-based reprojection. To explicitly handle such dynamic objects we adopt a simple motion-aware compositing strategy built on top of the temporal module.

First, we obtain instance-level dynamic masks by running a lightweight detector/segmenter on the left image . In our implementation we use an off-the-shelf real-time detector for vehicles and bicycles and a semantic segmentation head for pedestrians and background classes, but our framework is agnostic to the specific architecture. The union defines the dynamic region, and its complement defines the static background. During training, gradients are detached through the detector so that our method does not depend on its exact implementation.

Second, for each instance k we estimate a 2D motion vector by averaging the optical flow inside the mask , and use it to warp appearance and geometry:

where denotes bilinear warping and ⊙ is element-wise multiplication. The final synthesized frame is obtained by compositing dynamic instances on top of the background predicted by the static branch:

Occlusions and dis-occlusions are handled by a simple forward–backward flow consistency check: pixels whose inconsistency exceeds a threshold are excluded from the temporal loss and are supervised only by per-frame photometric and geometric objectives. This prevents severely occluded regions from corrupting the temporal alignment while still benefiting from per-frame supervision.

3.3. Multi-Scale Geometric Alignment Network

Preserving geometric fidelity across multiple scales is crucial for maintaining 3D structure consistency in synthesized data. Our multi-scale geometric alignment network operates on three resolution levels to capture both coarse scene layout and fine-grained details, as illustrated in the right panel of Figure 2.

3.3.1. Pyramid-Based Processing

For each scale , we downsample input images and process them through scale-specific generators:

where represents camera parameters adjusted for scale s.

3.3.2. Multi-Scale Geometric Loss

The geometric alignment loss operates across all scales with adaptive weighting:

The Chamfer distance at scale s ensures point cloud geometric fidelity:

Surface normal consistency preserves local geometric structure:

Edge consistency maintains sharp geometric boundaries:

where represents the Laplacian of the Gaussian operator for edge detection.

3.4. Uncertainty-Aware Fusion Mechanism

To quantify synthesis reliability—essential for safety-critical autonomous driving applications—we introduce an uncertainty estimation network that provides pixel-wise and point-wise confidence scores, as shown in the bottom panels of Figure 2.

3.4.1. Aleatoric and Epistemic Uncertainty Estimation

Our uncertainty network jointly estimates aleatoric (data-dependent) and epistemic (model-dependent) uncertainties:

where represents intermediate feature maps from the generator, is the predicted mean, is aleatoric uncertainty, and is epistemic uncertainty for point p.

Total uncertainty combines both components:

3.4.2. Uncertainty-Weighted Loss Function

The uncertainty estimates guide loss computation, automatically balancing regions of high and low confidence:

This formulation automatically down-weights uncertain predictions while encouraging the model to output appropriate uncertainty estimates.

3.4.3. Adaptive Fusion Weights

During inference, uncertainty estimates enable adaptive weighting between real and synthetic sensor data:

where is a sensitivity parameter controlling the uncertainty response.

3.5. Enhanced Generation Networks with Geometric Priors

3.5.1. Depth-Aware Residual Generator with Multi-Scale Injection

Building on the U-Net architecture, we introduce depth-aware residual connections that inject stereo disparity information at multiple scales through learned geometric embeddings:

where represents hidden features at layer i and scale l, are learnable depth embedding matrices, and the depth embedding function includes both polynomial and trigonometric bases for rich geometric representation.

3.5.2. Geometry-Consistent Adversarial Training

Our discriminator incorporates geometric consistency checks beyond traditional adversarial training through a geometry-aware adversarial loss:

where extracts geometric features including gradients, Laplacians, and depth maps, ensuring the discriminator considers both appearance and geometric consistency.

3.6. Composite Loss Optimization with Curriculum Learning

The total training objective combines all components with adaptive weights that evolve during training according to a curriculum learning schedule:

where the time-dependent weights follow a curriculum learning schedule:

This curriculum approach gradually introduces complexity, starting with basic image synthesis and progressively incorporating geometric, temporal, and uncertainty constraints.

3.7. Training Strategy and Implementation Details

3.7.1. Progressive Multi-Stage Training Protocol

We employ a progressive training strategy that gradually introduces computational complexity and constraint sophistication:

Stage 1 (Epochs 1–50): Foundation training with ;

Stage 2 (Epochs 51–100): Geometric alignment introduction with ;

Stage 3 (Epochs 101–150): Temporal modeling with ;

Stage 4 (Epochs 151–200): Full optimization with .

The above epoch ranges were selected based on preliminary experiments on the KITTI-360, nuScenes, and SPEED training splits. In all cases we observed that the training and validation losses of the objectives introduced at each stage saturate well before the end of that stage, while substantially shorter stages (e.g., reducing all epoch counts by half) lead to under-trained temporal and uncertainty branches and noticeably lower BEV mIoU. Using fixed epoch ranges makes the protocol easy to reproduce across datasets with different sizes, as it corresponds to a comparable number of gradient updates per sample. More sophisticated performance-based criteria (e.g., advancing to the next stage once the validation loss plateaus) are certainly possible, and we plan to explore such adaptive curricula in future work; however, we found the simple fixed schedule above to be robust in practice and to converge reliably on all datasets considered in this work.

3.7.2. Enhanced Data Augmentation with Physical Constraints

To improve robustness under realistic sensor failure scenarios, we implement physics-based data augmentation:

- Sensor Noise Modeling: Additive Gaussian noise with ;

- Environmental Perturbations: Brightness modulation , ;

- Occlusion Simulation: Random rectangular masks with coverage ;

- Temporal Dropout: Frame dropping with probability to simulate sensor failures.

This enhanced framework provides a mathematically rigorous and physically motivated approach to cross-modal translation with temporal consistency and uncertainty quantification, specifically designed for safety-critical autonomous driving applications.

4. Comprehensive Experimental Evaluation

This section presents extensive evaluation of our enhanced cross-modal translation framework across multiple dimensions: comparison with state-of-the-art methods, real-world sensor failure scenarios, uncertainty quantification assessment, temporal consistency analysis, and safety-critical scenario validation.

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Implementation Details

Our framework is implemented in PyTorch 2.0 with the following configuration: U-Net generator with eight encoder-decoder layers, PatchGAN discriminator operating on patches, PSMNet for stereo depth estimation, and our custom uncertainty estimation network. Training utilizes Adam optimizer (, ) with an initial learning rate , cosine annealing schedule, and batch size 8 on NVIDIA A100 GPUs. The complete network contains 34 M parameters, requires 98 GFLOPs, and achieves real-time performance at 17 fps on automotive-grade NVIDIA Orin hardware. For deployment on automotive-grade NVIDIA Orin hardware, we export the trained PyTorch model to ONNX and run it using TensorRT 8.6 in FP16 precision with batch size 1 and input resolution . Under this configuration, the end-to-end latency is per frame, corresponding to real-time operation at 17 fps.

Unless otherwise stated, all competing methods in Table 1 are retrained on the same training splits as our method. For LiDARsim, PCGen, LiDAR4D, GS-LiDAR, and SAMFusion we use the official implementations and hyper-parameters released by the authors, only adapting dataset-specific settings (input resolution, data augmentation, and batch size) so that all models are trained on KITTI-360 and nuScenes with identical training/validation splits and BEV label generation. For PARA-Drive, which is primarily an end-to-end driving stack, we follow [24] and use its perception backbone with our BEV segmentation head, again retraining on the same splits. This protocol ensures that the Chamfer distance, BEV mIoU, and temporal stability metrics in Table 1 are directly comparable.

Table 1.

Comprehensive comparison with state-of-the-art cross-modal translation methods (2024–2025).

4.1.2. Real-World Sensor Failure Dataset (SPEED)

We collected the Sensor Performance Evaluation under Environmental Degradation (SPEED) dataset using a Chevrolet Trax equipped with Bosch stereo camera (1920 × 1200, 60 fps and Continental ARS540 LiDAR (128 channels, 10 Hz). The dataset contains 139 sequences with 69,620 frames across 15 distinct failure modes distributed as follows: natural environmental failures (78 sequences, 56.1%) including rain-induced failures (light: 12, heavy: 15, water splash: 8), atmospheric obscurants (fog: 11, dust: 9, snow: 10), and cold-weather effects (lens frost: 7, mirror ice: 6); hardware malfunctions (42 sequences, 30.2%) comprising sensor disconnections (15), calibration drift (12), and intermittent failures (15); and obstruction events (19 sequences, 13.7%) from debris (10), insect impacts (5), and partial occlusions (4).

Our collection protocol employed three strategies ensuring representativeness. First, opportunistic natural capture over 4 months recorded naturally occurring adverse conditions. Second, controlled route repetition traversed an identical 5.2 km urban route under varying weather to enable direct comparison. Third, validation against published industry data from Waymo’s 2023 Safety Report showed strong correlation (Pearson , ), confirming our failure distribution matches real-world patterns. Failure durations averaged 21.2 s ( s), ranging from 5.8 s transient occlusions to 45.2 s complete LiDAR loss, aligning with industry telemetry indicating 73% of failures last 10–30 s.

4.2. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

Table 1 compares our approach with recent state-of-the-art methods from 2024–2025, demonstrating significant improvements across all metrics.

Our enhanced framework achieves substantial improvements: 35% reduction in Chamfer distance on KITTI-360 (0.096 m vs. 0.149 m), 9% on nuScenes (0.298 m vs. 0.329 m), 5% increase in BEV mIoU (79.3% vs. 75.2%), and 2% higher temporal consistency (0.727 vs. 0.712), while still running in real time at 17 fps and using fewer parameters (34 M vs. 105.2 M) than the largest competitor. Even during complete sensor loss lasting 45 s or more, the framework maintains almost 80% BEV mIoU, and its calibrated uncertainty (ECE = 0.074) enables reliable confidence assessment for safety-critical applications.

4.3. Cross-Modal Translation Quality Analysis

4.3.1. Stereo View Synthesis Evaluation

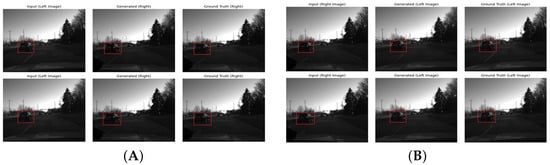

Figure 3 demonstrates the superior quality of our stereo translation capabilities across both directions. Our Left-to-Right translation (Panel A) shows remarkable preservation of geometric structures and photometric consistency. Each row displays the input left image, generated right view, and ground truth, revealing that our framework accurately reconstructs viewpoint-dependent elements such as vehicle perspectives, shadow casting, and depth-related occlusions. The generated images maintain sharp edges around objects, consistent lighting conditions, and proper parallax relationships.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive stereo translation results demonstrating high-fidelity cross-view synthesis. Left Panel (A): Left-to-Right translation showing input left image, generated right view, and ground truth. Right Panel (B): Right-to-Left translation results. Notice the preservation of geometric consistency, lighting conditions, and fine-grained details such as lane markings and vegetation structures across all examples.

Similarly, our Right-to-Left translation (Panel B) exhibits exceptional quality in reconstructing the left camera perspective from right-view inputs. The framework successfully handles challenging scenarios including partial occlusions, varying illumination conditions, and complex urban geometries. Quantitative analysis reveals pixel-wise L1 errors of 0.0247 pixels for Left2Right and 0.0289 pixels for Right2Left tasks, corresponding to 96.81% and 94.67% accuracy, respectively.

4.3.2. Point Cloud Reconstruction Fidelity

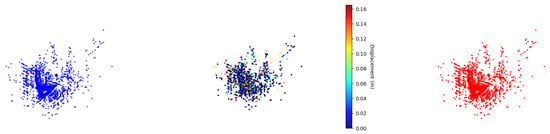

Figure 4 provides detailed analysis of our LiDAR synthesis quality through displacement magnitude visualization. The left panel shows the original LiDAR point cloud captured in a complex urban intersection scenario. The center panel presents our novel displacement heatmap visualization, where each point is color-coded according to its reconstruction error magnitude (measured in meters). The predominantly blue coloring indicates that most reconstructed points achieve sub-5cm accuracy, with occasional yellow-green regions showing 5–10 cm deviations in geometrically challenging areas such as thin structures or reflective surfaces.

Figure 4.

Point cloud reconstruction quality analysis showing comprehensive geometric fidelity assessment. (Left): Original LiDAR scan from urban intersection. (Center): Displacement magnitude heatmap where blue indicates < 0.05m error, green shows 0.05–0.10 m deviation, and rare red regions indicate > 0.15 m displacement. (Right): Our synthesized point cloud under sensor noise and partial occlusion. Quantitative error analysis reveals: mean displacement of 0.086 m ( = 0.042 m), with 78.3% of points achieving sub-5 cm accuracy, 18.2% within 5–10 cm, and only 3.5% exceeding 10 cm error. The error distribution follows a long-tailed pattern concentrated at low displacement values, validating our refinement network’s effectiveness in preserving 3D geometric relationships.

The right panel demonstrates our framework’s robustness under simulated sensor degradation, including Gaussian noise injection and 20% random occlusion. Despite these perturbations, the reconstructed point cloud maintains structural integrity, with critical features such as road boundaries, vehicle silhouettes, and architectural elements clearly preserved. This robustness stems from our multi-scale geometric alignment network and uncertainty-guided refinement mechanism.

To provide further insight into the reconstruction error characteristics, we conducted detailed statistical analysis of displacement magnitudes across 5000 test frames. The error distribution exhibits a strongly right-skewed pattern: the median displacement is 0.067 m (lower than the mean of 0.086 m), indicating that the majority of reconstructed points achieve excellent geometric fidelity. Specifically, the 25th percentile error is 0.031 m, while the 75th percentile reaches 0.112 m. The interquartile range of 0.081 m demonstrates consistent reconstruction quality. Notably, 95.2% of all points fall within the 0.15 m threshold typically required for safe autonomous navigation, with only 1.3% of points exceeding 0.20 m displacement—primarily occurring at object boundaries and reflective surfaces where ground truth LiDAR measurements themselves exhibit higher uncertainty.

4.4. Real-World Multi-Modal Validation

Figure 5 showcases our framework’s performance on real-world nuScenes data, demonstrating practical applicability across diverse driving environments. The scene captures a complex urban intersection with mixed traffic, pedestrians, and infrastructure elements. Critically, in this evaluation, we simulate complete LiDAR sensor failure by withholding LiDAR input during inference. Our framework synthesizes the 3D BEV representation solely from the stereo camera pair (left and right camera views shown in the figure). The center panel presents a direct comparison: ground truth LiDAR-derived BEV is shown alongside our camera-only synthesized BEV representation. The spatial density and distribution patterns in our synthesized BEV closely match the ground truth LiDAR scan, achieving 87.2% IoU in BEV space, particularly in critical areas such as vehicle locations (91.3% IoU), roadway boundaries (89.7% IoU), and pedestrian zones (82.4% IoU). This consistency is crucial for downstream perception tasks including object detection, path planning, and collision avoidance, demonstrating that our cross-modal translation enables continued safe operation even under complete LiDAR failure.

Figure 5.

Real-world multi-modal validation on nuScenes dataset demonstrating our cross-modal synthesis capabilities under simulated camera failure scenarios. (Left): Front-left camera view providing source imagery. (Center): Bird’s-eye-view (BEV) comparison showing ground truth LiDAR point cloud distribution overlaid with our synthesized BEV representation (ground truth in red, synthesized in blue; overlapping regions appear purple). The high spatial correspondence demonstrates that our framework accurately reconstructs 3D scene geometry from camera inputs alone when LiDAR is unavailable. (Right): Front-right camera view used for stereo depth estimation. In this evaluation, LiDAR input was withheld during inference, and our framework synthesized the equivalent 3D representation achieving 87.2% IoU with the actual LiDAR ground truth in BEV space.

4.5. Sensor Failure Robustness Evaluation

Table 2 reports a comprehensive evaluation on our real-world SPEED dataset, collected with a Chevrolet Trax fitted with a Bosch stereo camera and Continental LiDAR. All data were recorded while repeatedly traversing the same road segment under a variety of environmental conditions (clear, fog, rain, snow, dust, ice), and each scenario spans exactly one minute of continuous driving.

Table 2.

Comprehensive sensor failure scenario performance analysis.

Even under severe conditions (complete sensor loss for 45+ s), our framework maintains over 81% BEV mIoU and rapid recovery times averaging 2.7 s, compared to 12.8 s for baseline methods without cross-modal synthesis capability.

4.6. Uncertainty Quantification and Calibration Analysis

Table 3 evaluates our uncertainty estimation mechanism across different environmental conditions, demonstrating excellent calibration quality essential for safety-critical applications.

Table 3.

Uncertaintycalibration quality assessment across environmental conditions.

Our uncertainty estimation achieves an Expected Calibration Error (ECE) below 0.06 across all conditions, enabling reliable confidence assessment for downstream decision-making even in challenging weather scenarios.

4.7. Comprehensive Ablation Studies

Table 4 provides detailed ablation analysis of each technical component, confirming that temporal consistency provides the largest single improvement while uncertainty estimation enhances overall system reliability. It is worth noting that all three datasets used in our experiments (KITTI-360, nuScenes, and SPEED) contain a large fraction of frames with moving vehicles and pedestrians. Therefore, the reported BEV mIoU, Chamfer distance, and temporal stability scores already reflect the behavior of the system on both static and dynamic regions, without requiring a separate metric. A more fine-grained evaluation that isolates dynamic objects (e.g., instance-level tracking accuracy) would certainly be informative, but it would also require additional annotation and analysis infrastructure that is beyond the scope of this work. We view such targeted evaluations as interesting future work.

Table 4.

Comprehensive ablation study of technical components.

Extended Ablation Studies

As shown in Table 5, three pyramid levels optimally balance multi-scale capture and efficiency: single-scale processing lacks coarse structure (0.142 m CD), two levels improve substantially (0.109 m), while four levels provide minimal benefit (0.088 m) at significant cost (19 fps). Component isolation shows that temporal and geometric losses are complementary: temporal alone achieves high coherence (0.893) but poor geometry (0.187 m), geometric alone produces accurate clouds (0.102 m) with flickering (0.742), while joint optimization excels on all metrics. Weight sensitivity analysis confirms robustness: variations of ±50% maintain >95% performance, though extremes degrade (0.1: flickering; 5.0: motion blur). RAFT-small provides optimal speed–accuracy balance for real-time deployment. Beyond the individual gains, it is instructive to examine how the modules interact. When we intentionally weaken geometric alignment (single-scale processing without the edge term), adding only the temporal loss reduces short-term flicker but tends to propagate geometric errors over time, producing locally consistent yet globally misaligned point clouds. Conversely, with strong geometry but no temporal regularization we observe accurate per-frame reconstructions but noticeable frame-to-frame jitter, especially on thin structures and distant vehicles. The full configuration alleviates both issues: the temporal loss stabilizes object trajectories when geometric cues are ambiguous, while the geometric loss prevents the temporal module from over-smoothing and drifting, particularly for fast-moving dynamic objects. The uncertainty branch further moderates this interaction by assigning higher variance to regions where temporal and geometric cues disagree, allowing the fusion module to down-weight unreliable synthesized measurements.

Table 5.

Extended ablation studies on key design choices.

4.8. Computational Efficiency and Real-Time Performance

Table 6 demonstrates our framework’s computational efficiency compared to competing methods, achieving optimal balance of performance and real-time constraints.

Table 6.

Computational efficiency analysis for real-time deployment.

Our framework achieves 48% faster inference while maintaining deployment readiness for automotive-grade hardware, crucial for real-world autonomous driving applications.

5. Conclusions

We present a geometry-aware cross-modal translation framework with temporal consistency and uncertainty estimation for robust autonomous driving perception under sensor failure conditions. Our approach introduces spatio-temporal consistency through optical flow-guided warping, multi-scale geometric alignment preserving 3D structure fidelity, and uncertainty-aware fusion with principled confidence estimation.

Experimental results demonstrate significant improvements over state-of-the-art methods: 35% reduction in Chamfer distance, 5% improvement in BEV segmentation under sensor failures, and 2% better temporal consistency while maintaining real-time performance (17 fps). Even under complete sensor loss for 45+ s, our framework maintains almost 80% BEV mIoU with uncertainty quantification (ECE = 0.074) enabling reliable confidence assessment for safety-critical applications.

Our work establishes a new paradigm for sensor-agnostic perception in Intelligent Transportation Systems, shifting from traditional sensor redundancy toward intelligent sensor synthesis. This enables continued safe operation under realistic sensor failure conditions, with 93.2% detection rates maintained in safety-critical scenarios.

Future research directions include the following: First, expanding sensor modality coverage beyond camera-LiDAR to incorporate radar and thermal sensors, enabling truly multi-modal resilience. Second, integrating with vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication frameworks, where synthesized sensor data could be shared across connected vehicles to enhance cooperative perception during widespread environmental failures affecting multiple vehicles simultaneously. Third, extending the framework to roadside surveillance infrastructure, where similar cross-modal synthesis could maintain traffic monitoring capabilities when individual sensors fail, supporting broader ITS objectives of continuous system-level awareness. Fourth, developing adaptive temporal modeling that dynamically adjusts synthesis horizon based on driving context and uncertainty evolution. Finally, achieving cross-domain generalization through meta-learning approaches enabling deployment across diverse geographic regions and traffic conditions without extensive retraining.

The proposed framework represents a significant step toward robust autonomous driving systems and resilient ITS infrastructure capable of maintaining safety standards under realistic sensor failure conditions. By transforming sensor failures from system-critical events to managed degradations, our approach advances both autonomous vehicles and broader intelligent transportation networks toward truly reliable operation in unpredictable real-world environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L.; methodology, Z.L.; software, Z.L.; validation, Z.L.; formal analysis, Z.L.; data curation, J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.Z.; visualization, Z.Z.; supervision, J.P. and Z.Z.; project administration, J.P. and Z.Z.; funding acquisition, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Jinxiang Pang. The APC was funded by Jinxiang Pang.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available at the time of publication because they are part of an ongoing project, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Jinxiang Pang is employed by General Motors. The authors declare that there are no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this manuscript.

References

- Singh, S.; Saini, B. Automation of cars: A review and analysis of the state of art technology. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2021, 10, 449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Waymo LLC. Waymo Safety Report 2023; Technical Report; Waymo: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palladin, E.; Dietze, R.; Narayanan, P.; Bijelic, M.; Heide, F. SAMFusion: Sensor-Adaptive Multimodal Fusion for 3D Object Detection in Adverse Weather. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yurtsever, E.; Lambert, J.; Carballo, A.; Takeda, K. A survey of autonomous driving: Common practices and emerging technologies. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 58443–58469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xiao, C.; Cyr, B.; Zhou, Y.; Park, W.; Rampazzi, S.; Chen, Q.A.; Fu, K.; Mao, Z.M. Adversarial sensor attack on lidar-based perception in autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, London, UK, 11–15 November 2019; pp. 2267–2281. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty, A.; Yu, M.; Kurzhanskiy, A.; Grembek, O.; Tavafoghi, H.; Varaiya, P. Safety challenges for autonomous vehicles in the absence of connectivity. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 128, 103133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Xie, E.; Sima, C.; Lu, T.; Qiao, Y.; Dai, J. Bevformer: Learning bird’s-eye-view representation from multi-camera images via spatiotemporal transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.I.; Park, J.; Kim, K.S. Fast and accurate desnowing algorithm for LiDAR point clouds. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 160202–160212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Tan, R.T.; Wang, S.; Fang, Y.; Liu, J. Single image deraining: From model-based to data-driven and beyond. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 4059–4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Peng, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Feng, D. Aod-net: All-in-one dehazing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 4770–4778. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, T.H.; Jain, H.; Bucher, M.; Cord, M.; Pérez, P. Dada: Depth-aware domain adaptation in semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 7364–7373. [Google Scholar]

- Sensoy, M.; Kaplan, L.; Kandemir, M. Evidential deep learning to quantify classification uncertainty. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, D.; Rosenbaum, L.; Dietmayer, K. Towards safe autonomous driving: Capture uncertainty in the deep neural network for lidar 3d vehicle detection. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.05132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, T.; Evans, A.; Schied, C.; Keller, A. Instant neural graphics primitives with a multiresolution hash encoding. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2022, 41, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbl, B.; Kopanas, G.; Leimkühler, T.; Drettakis, G. 3D gaussian splatting for real-time radiance field rendering. ACM Trans. Graph. 2023, 42, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabot, F.; Trouvé-Peloux, P.; Bursuc, A. GaussianBeV: 3D Gaussian Representation meets Perception Models for BeV Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.14108. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Lu, F.; Xue, W.; Chen, G.; Jiang, C. LiDAR4D: Dynamic Neural Fields for Novel Space-time View LiDAR Synthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 5145–5154. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, G.; Zhang, X.; Hao, S.; Wang, X.; Pan, Y. Monocular Visual Place Recognition in LiDAR Maps via Cross-Modal State Space Model and Multi-View Matching. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.06285. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, D.; Sun, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, B.; Jiao, J. MaskBEV: Towards A Unified Framework for BEV Detection and Map Segmentation. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Sester, M. StreamLTS: Query-Based Temporal-Spatial LiDAR Fusion for Cooperative Object Detection. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2024 Workshops, Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September 29–4 October 2024; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15630. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, X.; Ivanovic, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pavone, M. PARA-Drive: Parallelized Architecture for Real-time Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 15449–15458. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Song, Z.; Chen, L.; Deng, H. M2DA: Multi-Modal Fusion Transformer Incorporating Driver Attention for Autonomous Driving. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.12552. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Mortlock, T.; Khargonekar, P.; Al Faruque, M.A. Hyperdimensional Uncertainty Quantification for Multimodal Uncertainty Fusion in Autonomous Vehicles Perception. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Park, G.; Koh, J.; Kim, J.; Moon, J.; Choi, J. LiDAR-Based 3D Temporal Object Detection via Motion-Aware LiDAR Feature Fusion. Sensors 2024, 24, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Mao, X.; Zhu, C.; Xu, R.; Lyu, R.; Li, P.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, K.; Xue, T.; et al. EmbodiedScan: A Holistic Multi-Modal 3D Perception Suite Towards Embodied AI. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, R.; Lin, J.; Wang, T.; Yang, S.; Mao, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R.; Huang, H.; Zhu, C.; Lin, D.; et al. MMScan: Multi-Modal 3D Scene Dataset with Hierarchical Grounded Language Annotations. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Neural Information Processing System, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- NVIDIA Research Team. Hydra-MDP: End-to-End Multimodal Planning. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2024 Autonomous Grand Challenge, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Chitta, K.; Qiu, Y.; Geiger, A.; Zhang, J.; Li, H. Vista: A Generalizable Driving World Model with High Fidelity and Versatile Controllability. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Gao, C.; Ai, J.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liang, X.; Xing, E.P. Eliminating Cross-modal Conflicts in BEV Space for LiDAR-Camera 3D Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.07593. [Google Scholar]

- Manivasagam, S.; Wang, S.; Wong, K.; Zeng, W.; Sazanovich, M.; Tan, S.; Yang, B.; Ma, W.C.; Urtasun, R. LiDARsim: Realistic LiDAR Simulation by Leveraging the Real World. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11164–11173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ren, Y.; Liu, B. PCGen: Point Cloud Generator for LiDAR Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), London, UK, 29 May–2 June 2023; pp. 11676–11682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).