Abstract

The integration of electric vehicles (EVs) and fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) requires accessible and profitable facilities for fast charging. To promote fast-charging stations (FCSs), a systematic analysis that encompasses both planning and operation is required, including the incorporation of multi-energy resources and uncertainty. This paper presents an optimization framework that addresses a joint strategy for the configuration and operation of an EV/FCEV fast-charging station (FCS) integrated with distributed energy resources (DERs) and hydrogen systems. The framework incorporates uncertainties related to solar photovoltaic (PV) generation and demand for EVs/FCEVs. The proposed joint strategy comprises a four-phase decision-making framework. Phase 1 involves modeling EV/FECE demand, while Phase 2 focuses on determining an optimal long-term infrastructure configuration. Subsequently, in Phase 3, the operator optimizes daily power scheduling to maximize profit. A real-time uncertainty update is then executed in Phase 4 upon the realization of uncertainty. The proposed optimization framework, formulated as mixed-integer quadratic programming (MIQP), considers configuration investment, operational, maintenance, and penalty costs for excessive grid power usage. A heuristic algorithm is proposed to solve this problem. It yields good results with significantly less computational complexity. A case study shows that under the most adverse conditions, the proposed joint strategy increases the FCS owner’s profit by 3.32% compared with the deterministic benchmark.

1. Introduction

The advancement of distributed energy resources (DERs) and green transportation technologies is an essential strategy to address global climate change. The energy sector is increasingly adopting high levels of integration of renewable energy due to its low carbon emissions, emphasizing the need to decarbonize the transport sector [1,2]. Recent data show that global greenhouse gas emissions reached a record high of 57.1 Gt CO2 in 2023, with the transport sector being the second-largest source, contributing 8.4 Gt CO2, i.e., 15% [3]. In contrast, the global EV and FCEV market has experienced substantial growth in recent years. Global EV sales increased by approximately 75% between 2015 and 2023, while the worldwide stock of FCEVs expanded by approximately 20% compared with 2022 [4]. Electrifying the transportation sector through the transition to electric vehicles (EVs) and fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) is considered a promising solution to significantly reduce the emissions of conventional fossil-fueled vehicles, especially when powered by renewable energy sources [5]. EVs rely on rechargeable batteries for propulsion, eliminating the need for internal combustion engines. In contrast, for traction, FCEVs convert hydrogen into electric power through fuel cells, providing advantages such as longer driving ranges, faster refueling, and no battery degradation issues [6]. With the proliferation of EVs and FCEVs, the environmental benefits will be maximized when paired with a clean energy supply, making it a crucial element in global efforts to mitigate global warming issues [7,8].

The design and provision of efficient and economical fast-charging facilities are critical milestones in ensuring reliable energy supply for EVs and FCEVs, minimizing operational costs, reducing negative impacts on the power grid [9], and enhancing their flexibility and resilience to threats [10]. Although fast-charging stations (FCSs) combined with DERs can ease quick recharging for EVs and lower hydrogen costs for FCEVs, these advantages are diminished if these stations depend solely on a conventional grid powered predominantly by fossil fuels. Therefore, integrating DERs can sustain and even improve the benefits of widespread adoption of EVs and FCEVs, ensuring a cleaner energy supply, leveraging the adverse impact of fast charging on the utility grid, and minimizing environmental impacts.

1.1. Literature Review

Recent studies have extensively investigated the deployment of EV charging infrastructure, focusing on optimal location and sizing strategies [11,12,13]. In [11], particle swarm optimization was applied to identify the optimal FCS sizes and locations, considering investment, operation, maintenance, grid loss, and reliability costs. Hashemian et al. proposed a mixed-integer linear programming model to jointly optimize locations and sizes of FCSs on coupled transportation–distribution networks with the aim of minimizing user travel and waiting times and enhancing the performance of the distribution network [12]. Furthermore, a two-stage method was introduced in [13] to determine the number and types of charging stations in parking areas, along with scheduling strategies to balance service quality and operational costs. While the authors addressed the joint siting and sizing of FCSs for EVs, the integration of FCEVs as an alternative to complement EV solutions and their associated refueling facilities remains an open research topic.

Building on efforts in EV infrastructure, a similar focus has been placed on hydrogen fueling systems for FCEVs. However, despite growing industrial interest, the hydrogen market still struggles to align investments between vehicle deployment and fueling infrastructure. To address this, [14] proposes a strategic deployment framework for hydrogen refueling stations in South Korea, employing three mathematical models to optimize placements on roads, highways, and bus networks. However, the high cost and extensive development needs of hydrogen production and distribution infrastructure pose major challenges to the rapid and sustainable adoption of FCEVs [15]. Consequently, Wijayasekera et al. analyzed the status and future prospects of hydrogen bus fleets, highlighting clean hydrogen production, fuel-cell advances, and strategies to enhance the environmental and economic viability of hydrogen-based public transport systems [16].

To meet the substantial power demands for both the rapid charging of EVs and the hydrogen refueling of FCEVs, FCS deployment requires either grid connection capacity upgrades or DER integration to buffer energy between the grid and the charging station. In [17], the authors addressed this challenge by formulating an optimization model to minimize energy storage system (ESS) costs, improve EV resilience, and reduce peak load, thus determining the optimal ESS size for fast-charging applications. Similarly, a methodology for the sizing of stationary ESSs in FCSs operating with limited grid connection capacity was proposed [18]. The approach incorporates acceptable waiting times for electric vehicles and conducts an economic assessment comparing the costs associated with the deployment of stationary ESSs against those of the upgrade of the grid infrastructure, aiming to identify the most cost-effective strategy to improve the performance and economic viability of FCSs. In [19], a flexible interconnection architecture with an electrical–hydrogen hybrid storage system and a hierarchical power management strategy was proposed to enable coordinated, real-time operation of a central railway power system. However, while storage technologies help smooth supply and demand, integrating renewable energy into FCSs can further enhance clean energy supply for EVs and FCEVs.

Further research has expanded the concept of FCSs by integrating renewable energy resources to improve economic performance and environmental sustainability. In [20], a cooperative energy management framework was introduced for a virtual energy hub which integrates electric buses, EVs, battery energy storage systems, and solar PV generation. The framework uses a three-stage decision-making model to optimize energy utilization, minimize costs, and improve grid support. In terms of the coupling of renewable generation and energy storage with FCSs, our previous study proposed an integrated framework for the optimal planning and operation of fast EV charging stations equipped with PV systems and ESSs, seeking to maximize profitability through optimal planning and energy management, accounting for investment, operational, and penalty costs [21]. However, the work did not consider the hydrogen system or the inherent uncertainties associated with solar PV output and EV charging demand. In [22], a coordinated operation model was proposed to align urban transportation networks and power distribution systems by leveraging hydrogen refueling service fees. The model was designed to minimize travel, operational, and environmental costs while simultaneously addressing uncertainties in renewable energy generation and optimizing fueling behaviors for hydrogen fuel-cell electric vehicles. The work targeted a city-wide network. Zhang et al. introduced a method to minimize the total installation cost of a hydrogen fueling station with PV systems while simultaneously maximizing revenue [23]. However, to attract private investment in public-like FCS projects, it is essential to address the underexplored challenge of co-optimizing FCS service components and DERs, such as renewable energy resources, ESSs, and hydrogen resources, for cost-effective long-term configuration and operation. Moreover, the explicit treatment of dynamic geographical impacts, renewable generation uncertainties, and stochastic EV/FCEV demand remains largely overlooked, representing a key gap that this study seeks to address. Table 1 summarizes the research gaps in the literature review.

Table 1.

Comparison of optimization problem and DER aspect in FCS configuration and operation. (HT: hydrogen storage tank; EL: electrolyzer; FC: fuel cell).

1.2. Contributions

Limited fast-charging infrastructure and economic viability remain the main barriers to large-scale adoption of EVs and FCEVs. To address these challenges, this study proposes a comprehensive framework for the joint optimization of FCS configuration and operation, integrating DERs and hydrogen systems. The framework considers the uncertainties associated with solar PV generation and EV charging [FCEV refueling] demands. The optimization problem is formulated as mixed-integer quadratic programming (MIQP), which is an NP-hard problem. To facilitate computational tractability, a relaxation approach is employed by treating integer variables as continuous and using the convexity of quadratic terms under certain conditions to enable efficient solution generation. The performance of this relaxation technique is benchmarked against an integer projection method to evaluate solution quality and practical feasibility. The specific contributions of this research study are as follows:

- Co-optimization of FCS configuration and operation: This study formulates a joint optimization framework for the optimal configuration and scheduling of an FCS integrated with DERs and hydrogen systems. The framework aims to maximize overall profit by integrating the costs associated with investment, operational, maintenance, and peak demand penalties. Its effectiveness is evaluated in dynamic geographical settings.

- Robust optimization under uncertainties: This study considers uncertainties in PV output and EV/FCEV charging demand and applies a robust optimization approach to help the FCS operator manage fluctuations and ensure stable profits.

- Real-world deployment considerations: The proposed framework uses a land-use cost function to optimize the economic installation of DERs across diverse area types. It also explicitly models grid capacity with overage peak penalties to meet practical utility integration requirements.

- Real-time adaptation strategy: A real-time strategy is proposed to update operational decisions in real time as uncertainties in PV output and EV/FCEV charging demand unfold throughout the day.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the system model of an FCS integrated with DERs and hydrogen systems. Section 3 presents the mathematical formulation of an optimization strategy for the joint configuration and operation of the FCS, considering uncertainties in renewable generation and EV/FCEV demand. Section 4 presents a case study and a discussion of the numerical results. Then Section 5 concludes the paper and summarizes key contributions and future research directions.

2. System Model

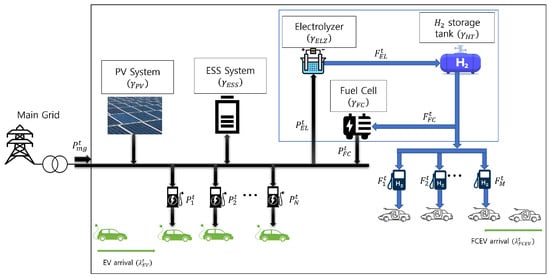

Figure 1 illustrates the system model of this work. We consider an FCS that integrates local power resources, a hydrogen system, and EV/FCEV chargers. Let and denote sets of fast chargers for EVs and hydrogen dispensers for FCEVs, respectively, where and are the numbers of chargers and hydrogen dispensers, respectively. The FCS local supply system comprises a solar PV generator, an ESS to manage energy dispatch by charging and discharging as needed to smooth system operations, and a stationary fuel cell (FC). The FCS also comprises a hydrogen system consisting of an electrolyzer, a hydrogen storage tank (HT), and a stationary FC for on-site hydrogen production, storage, and power conversion. This hybrid supply strategy improves operational flexibility and reduces grid dependence during peak periods.

Figure 1.

System model of the proposed framework for a fast-charging station.

During the long-term planning horizon, the FCS operator makes investment decisions in the capacity of the service and power components, while in the short-term operational period, it schedules electric power and hydrogen resources. The scheduling of daily operations is discretized into T intervals, i.e., . Each vehicle is assumed to complete its fast charging [refueling] in a single time slot , allowing for convenient scheduling and resource allocation. Each charger [dispenser] [] serves at most one EV [FCEV] per time slot, and the charging [refueling] process starts and ends within the same time slot.

Note that due to limited infrastructure, not all arriving vehicles can be served immediately. When arrivals exceed available chargers[dispensers], vehicles queue in waiting areas. If both service and waiting areas are full, additional arrivals are rejected.

- Operation model of EV Chargers and FCEV Hydrogen Dispenser

The EV fast charger power and FCEV dispenser hydrogen flow are modeled as non-deferrable, inelastic loads that must be met immediately upon request and cannot be shifted to another time. Consequently, the EV charging power in each charger and hydrogen flow in each FCEV dispenser are constrained by their respective rated capacities, ensuring compliance with equipment limits. They are formulated as follows:

Equations (1) and (2) enforce the technical specifications of the charging and refueling infrastructure, ensuring operational feasibility in all scenarios.

- FCS Power Supply Sources

The FCS is powered by a combination of solar PV output, main-grid electricity, and the energy supplied by the FC, if any. Given an investment decision in solar PV capacity , the available solar PV power in scenario s at time t is constrained by

In cases when solar PV and ESS energy is insufficient to meet the EV [FCEV] charging [refueling] demands, the FCS supplements its supply by purchasing electricity from the grid. The limit of the main-grid power purchase in scenario s at time t is defined as

where denotes the technical limit of the power line connecting the FCS to the grid. While the grid is assumed to supply total demand within this limit, exceeding it may trigger peak demand penalties or operational risks due to the high power requirements of EV chargers and electrolyzers. In contrast, solar PV generation does not incur fuel costs, making its marginal cost negligible. Hence, the FCS operator is incentivized to prioritize PV utilization over grid power to minimize operating costs and improve system sustainability.

- Energy Storage System (ESS)

To mitigate solar PV generation intermittency and ensure smooth power supply, the FCS operator actively manages ESS charging and discharging to balance supply and demand in real time. During long-term planning, the operator determines the ESS energy capacity and PCS capacity , which restrict the maximum allowable charge and discharge in each scenario s and time t as follows:

where and denote the charging and discharging power of the ESS, respectively.

The evolution of the ESS state of charge (SoC) is influenced by both the charging efficiency and the discharging efficiency . The SoC level and its constraint in s at t are defined as

where and denote the minimum and maximum levels of state of charge, respectively. Equation (9) enforces a cyclical SoC constraint, requiring the terminal SoC at the end of the day to match its initial value, ensuring inter-day operational independence and preserving long-term storage integrity.

- Hydrogen System Integration

During the long-term configuration horizon, the FCS operator also determines the capacities of key hydrogen components: the electrolyzer , HT , and FC . In the short-term operation period, the FCS operator manages the main-grid and solar PV power to run the electrolyzer, produce hydrogen for the refueling of FCEVs, and store any surplus. Stored hydrogen can be reconverted to electricity through the FC for grid export or peak demand supply, improving system flexibility and economic efficiency.

Electrolyzer Operation: Hydrogen is produced on site using an electrolyzer powered by solar PV and/or main-grid electricity. Let and denote the power consumption of the electrolyzer and the amount of hydrogen produced in s at t, respectively. Hydrogen production is modeled by

where , , and denote the electrolyzer efficiency, the hydrogen density, and the higher heating value of hydrogen, respectively. The operation of the electrolyzer is constrained by its power rating and hydrogen production as follows:

where denotes the maximum amount of hydrogen produced.

Hydrogen Storage Tank (HT) operation: The HT enables the temporal decoupling of hydrogen production and consumption. Its hydrogen mass state evolves with the inflows of the electrolyzer and the outflows to both the FCEV and the FC and accounts for dissipation losses . The state of hydrogen mass in s at time t is defined as

The HT must operate within the safe operating limits as given by

where and represent the minimum and maximum states of the hydrogen mass, respectively. Similarly to the ESS, the storage level at the end of the day is equal to its initial level, ensuring inter-day consistency and long-term system reliability. That is,

Stationary Fuel-Cell (FC) Operation: The hydrogen produced is used primarily to meet the FCEV demand. However, it can also be consumed by an FC to generate electricity, either for grid export or internal use during peak-load periods. The linear relationship between the hydrogen consumed by the FC, , and the power produced, , in scenario s at time t is described as

where the operation of the FC is based on its efficiency . The two limit constraints of FC operation are

3. Proposed Optimization Strategy for Joint Configuration and Operation of FCSs

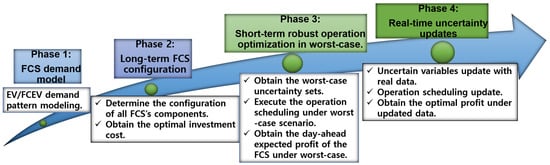

This section describes the proposed robust optimization framework for the joint capacity configuration and operational scheduling of a grid-connected FCS integrated with DERs, accounting for uncertainties in renewable generation and charging demands. The proposed framework consists of a four-phase decision-making process, as shown in Figure 2. Phase 1 captures the time-varying demand for EVs and FCEVs based on stochastic arrival patterns. This information is then fed into Phase 2, which addresses a long-term investment planning problem to determine the optimal configuration of FCS components, ensuring that investment cost efficiency aligns with projected demand. Phase 3 formulates a robust short-term operational scheduling model for energy and hydrogen resources, accounting for worst-case deviations in load demand and renewable generation within a defined uncertainty set. Phase 4 integrates real-time data assimilation to dynamically update operational decisions, thereby improving the adaptability and responsiveness of the system to evolving conditions.

Figure 2.

Four-phase decision-making process to develop robust optimization for both the configuration and operation of FCSs.

3.1. Phase 1: Modeling of EV and FCEV Demand Patterns

The arrival processes of EVs and FCEVs at the FCS are modeled as independent Poisson processes [24] with time-varying rates and , respectively. The instantaneous energy demand associated with each arriving EV or FCEV is characterized by a Gaussian distribution , where and denote the mean and standard deviation of the demand, respectively, capturing the variability in service requirements.

Let [] denote random variables representing the rapid charging demand of EVs [FCEVs], and and represent the expected total charging demand for EVs and FCEV in one time slot, respectively. Given the installed number of fast chargers and hydrogen dispensers , the total expected energies required by the FCS to meet EV and FCEV fast-charging processes in time slot t are defined as

Let [] represent the rated capacity at which power [hydrogen] is provided by the fast charger [hydrogen dispenser]. The hydrogen power and the hydrogen dispenser power rate are converted to the amount of hydrogen and the hydrogen dispenser rate using the electrolyzer, respectively.

Analogously, the expression for the expected amount of power delivered by the FCS to supply the expected demand for an EV during the charging process is obtained as , where . Also, the expected hydrogen energy value of an FCEV can be re-expressed as , where . The expected amount of power [hydrogen] for a fast charger [] to supply the charging demand of an EV [FCEV] at t is given by

Note that in our case study, to determine the expected power utilization for the fast charger and the expected hydrogen utilization for the hydrogen pump, it is assumed that and .

3.2. Phases 2 and 3: Joint Optimization Framework

This section formulates the proposed joint optimization problem that co-optimizes the long-term capacity configuration and the short-term operational decisions of the FCS.

3.2.1. Long-Term Investment Problem for Configuration

In this work, Phase 2 formulates a long-term configuration model to determine the optimal configuration of all FCS components to meet the projected demand. This configuration phase establishes the system capacity needed to support operational decisions in Phase 3.

The objective of the FCS configuration model is to determine investment decisions that minimize total cost, comprising capital investment, expected operational cost, maintenance cost, and peak demand penalties while maximizing operational profit. The decision variables for the configuration phase are defined by the set , where the symbols represent the number of EV chargers, the hydrogen dispensers, the solar PV capacity, the ESS capacity, the PCS capacity, the electrolyzer capacity, the stationary fuel-cell capacity, the hydrogen storage tank capacity, and the total required land area, respectively. These decision variables should be non-negative.

The long-term capital investment cost is formulated as

where the C parameters represent the capital costs per unit of the corresponding components. The coefficients , , and denote the second-order, first-order, and fixed coefficients of the land cost function.

In practice, marginal investment costs tend to increase with the increase in FCS capacity, primarily due to land acquisition costs, which are highly sensitive to geographical and environmental factors. To capture this variability, a dynamic land cost model is incorporated into the FCS configuration framework. Specifically, the cost of the land is modeled as a quadratic function, reflecting the non-linear relationship between the area of the land and the associated cost. This formulation accounts for both physical configuration constraints and regional economic factors influencing land prices [25].

The total requirement for land size is calculated as the sum of the unit land areas of all installed components, defined as

where the L parameters represent the unit sizes of the occupational area for the corresponding components. Furthermore, the investment cost of the FCS should be less than the total budget B, as expressed in

3.2.2. Short-Term Operational Scheduling of FCS

Following the long-term configuration decisions established in Phase 2, the FCS operator optimizes short-term operations, focusing on efficient resource utilization and reliable service delivery. The day-ahead schedule is performed to maximize daily profit by balancing operating revenue against operating cost with the objective of providing sufficient energy for quick charging and hydrogen refueling to reduce vehicle delay, rather than fully charging or refueling each vehicle.

Assuming that solar PV production can be accurately forecast, a finite set of solar PV generation scenarios is considered to represent a typical daily solar profile. Note that previous studies showed that solar power forecasts typically achieve a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) ranging from 6% to 13% [26]. At the beginning of each operational day, the FCS operator determines an optimal energy management strategy for each scenario and time slot . The operational scheduling decision variables are defined by a set , representing the power from the main grid, the solar PV output, the ESS charging power, the ESS discharge power, the electrolyzer power demand, the stationary fuel-cell power output, the amount of hydrogen produced, the amount of hydrogen consumed by the stationary fuel cell, the necessary power for the fast charging of an EV at a fast charger, and the demand for the hydrogen refueling of an FCEV at a hydrogen dispenser at time t in scenario s, respectively.

- FCS Operation Cost

To meet the daily charging demands of EVs and the hydrogen refueling of FCEVs, the FCS incurs various operational costs. These include purchases of electricity from the main grid and degradation costs associated with the ESS and hydrogen system. The expected total daily operating cost of the FCS, , is a linear function of the operational variables over all scenarios and time intervals . It is defined as

where , and denote the realization probability of stochastic variables, the unit cost of the electricity in the grid, and the degradation cost of the ESS and the hydrogen system, respectively. The FCS is required to maintain a balance between supply and demand. That is,

The left and right sides of the balance equation represent demand and supply, respectively.

- Peak Penalty and Maintenance Cost

To ensure a smooth power supply and reflect the pricing structures of the main grid, a peak demand penalty is applied when the grid power usage reaches its maximum demand. The peak penalty is defined as

where and denote the cost of peak and the peak power of the main grid, respectively.

The FCS manages system maintenance to ensure long-term reliability and continuous operation. Its maintenance cost is modeled as a linear function of the configuration decision variables . That is,

where the parameters represent the maintenance fees for each component.

- FCS Operation Profit

By providing rapid charging and refueling services to EVs and FCEVs, the FCS generates revenue by charging and hydrogen refueling fees. In addition, it can earn revenue by selling surplus solar PV and FC power to the main grid. The expected daily revenue of the FCS, , across all scenarios and time slots is defined as

where , , and denote the service fee to charge an EV, the service fee to fuel an FCEV, the price to sell the power back to the main grid, the surplus solar PV power, and the FC output, respectively. The expected operational profit of the FCS, , which is the difference between operational revenue and operational cost, is also obtained as

3.2.3. Joint Configuration and Operation Optimization Problem

The complete set of decision variables for this joint optimization framework is denoted by . A time discount factor is introduced to adjust the daily operating profit to the total operating horizon. That is, , where M and denote the life time of the FCS and the interest rate in period m, respectively. Based on the defined cost components and the dynamics of the system, the objective function of the joint configuration and operation optimization problem is formulated as

The proposed framework in Equation (32) attempts to obtain the long-term optimal configuration of the FCS that maximizes its overall profit while accounting for both the long-term investment in infrastructure and the short-term operational scheduling, maintenance cost, and the peak penalty in all scenarios over the planning horizon. It is subject to constraints on the charger [dispenser] (Equations (1) and (2)), power supply (Equations (3) and (4)), ESS (Equations (5)–(9)), hydrogen system operation (Equations (10)–(18)), land area (Equation (24)), investment budget (Equation (25)), and power balance (Equation (27)). The proposed problem inherently enforces mutual exclusivity for ESS charging–discharging and electrolyzer–fuel-cell operation. Specifically, the investment cost, degradation cost, and balance equation naturally discourage simultaneous charging and discharging, as well as simultaneous operation of the electrolyzer and fuel cell, since concurrent operation would increase total system costs.

The proposed optimization problem involves configuration variables with integer values, such as the number of EV chargers [FCEV dispensers] , while the land cost in the investment cost function is defined by a quadratic expression, introducing non-linearity into the model. As a result, the problem is classified as an MIQP problem, which is NP-hard. Since a quadratic function is convex when its Hessian is positive semidefinite, the land cost function remains convex when [25,27]. To solve this problem efficiently, the integer variables and are relaxed to continuous values, making Equation (32) a convex optimization problem. Then an integer projection technique [24] is applied to recover feasible integer decisions and confirm if the relaxed solution is a good suboptimal solution.

3.2.4. FCS Operation Scheduling Under Uncertainty

Traditional approaches typically define uncertain parameters using uncertainty sets based on a predicted profile [28,29]. Although perfect foresight of solar PV generation and EV/FCEV demand is used, in practice, forecast errors are inevitable due to weather fluctuations and behavioral variations. To address this, we formulate a robust optimization framework that captures the worst-case operational scenarios for the FCS.

Let denote the set of worst-case uncertainty variables, where each variable represents the actual realization within its corresponding set of uncertainties. The uncertainty sets for solar PV output , EV charging demand , and FCEV refueling demand are defined as

respectively, where , and denote the lower and upper prediction limits of solar PV output and the charging [refueling] demand of EVs [FCEVs], respectively, consistent with their installed capacities. For each set of uncertain variables, an uncertainty budget is defined by a pair of bounds and , which represent the deviation level of the uncertain variables from their nominal forecast values. These uncertainty sets are constructed based on the prediction limits of the uncertain variables [30]. For example, and indicate that the daily output of the solar PV system can vary between 90% and 110% of its nominal forecast, representing the worst case for the PV system with a level of uncertainty of 10%. Expanding the set by decreasing or increasing results in a more conservative but robust solution.

- FCS Operation under Worst-Case Uncertainty

To evaluate system resilience, we reformulate the short-term operational scheduling problem, under worst-case conditions, to incorporate variability in solar generation and charging [refueling] demand. The expected operational revenue under the worst-case uncertainty, , in all scenarios at time T is defined as

The profit is revenue minus cost, that is,

Similarly to the optimization without uncertainty, the power balance and hydrogen mass dynamics accounting for worst-case deviations are given as

- Short-Term FCS Scheduling under Worst-Case Uncertainty

Now, we define the robust joint configuration and operation problem, which aims to maximize the expected profit under the worst-case realization of uncertainties, as

where represents the set of all investment and operational decision variables under uncertainty.

In this framework, Phase 1 defines the FCS demand profile, Phase 2 determines the fixed long-term configuration for the investment period, and Phase 3 manages the day-ahead scheduling under worst-case uncertainty. This robust formulation ensures feasible, near-optimal operation for all realizations within the specified uncertainty sets, maintaining economic viability and operational resilience despite prediction errors in solar generation and EV/FCEV demand.

3.3. Phase 4: FCS Real-Time Operation

Although worst-case modeling provides a conservative baseline, real-time operations follow stochastic patterns. We define a real-time uncertainty set to capture the actual values of solar PV power output, the charging demand of EVs and the hydrogen demand of FCEVs. This paper presents a simulation for real-time uncertainty realization using a normal Gaussian distribution, where the degree of uncertainty is reflected in the MAPE. The FCS operator captures the real-time variables and updates the operational schedule using the real-time adjustment mechanism, retaining the robustness of the day-ahead plan while maximizing actual profits under stochastic conditions. The MAPE is defined as

where n, , and denote the number of observations, the actual value at time t, and the forecast value at t, respectively.

Algorithm 1 shows real-time operation. It first updates the problem in Equation (40) by (i) adjusting the main-grid power demand and then the equations for (ii) balance and (iii) hydrogen mass flow, considering the real-time variables . The (i) adjusted main-grid power demand is given by

where , and denote the increase in the power of the main grid due to the decrement of solar PV power in real time, the reduction in the power of the main grid due to the increase in PV power, the decrease in the power of the main grid due to the increase in the demand of EVs, the increase in the power of the main grid due to the increase in the demand of EVs, the decrease in the power of the main grid due to the decrease in the demand of FCEVs and the increase in the main grid due to the increase in the demand of FCEVs, respectively. Note that cannot be negative and should always be constrained by the limits imposed by the power line capacity. The updated (ii) balance and (iii) hydrogen mass equations are

With these updated equations, optimal scheduling, i.e., Equation (40), is re-executed at each time slot to obtain the final refined profit, considering real-time updates.

| Algorithm 1 Real-time adjustment for FCS operation |

|

4. Case Study

This section evaluates the proposed joint configuration and profit maximization framework for an FCS integrated with DERs under uncertainties of demand and solar PV energy. Day-ahead scheduling simulations were implemented in AMPL with the Gurobi solver [31], while real-time uncertainty tracking and sensitivity analyzes were performed in MATLAB R2024b. All simulations were performed under an academic license on a Windows 10 computer with an Intel® Core™ i7-9700K @ 3.60 GHz CPU and 64 GB of RAM. For a typical scenario in this study, the simulation time was 12 min. We note that computation time may vary based on case parameters and computational tools.

4.1. Simulation Setting

This study considers a grid-connected FCS with a 10-year investment horizon [21,32]. The proposed FCS integrates a solar PV system, an ESS, a PCS, and a hydrogen system consisting of an EL, an HT, and an FC. Daily operations are scheduled over a one-day horizon with a 10-minute resolution, i.e., 144 time slots, enabling the fine-grained scheduling of charging and refueling activities. The maximum power exchange with the main grid is 1500 kW, and any overage peak is penalized at 3.82 USD/kW [33]. The price of land acquisition is set at 645 USD/m2, 603 USD/m2, and 458 USD/m2 for commercial, industrial, and residential areas, respectively [34].

Table 2 presents the Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) time-of-use (TOU) electricity pricing scheme for business electric vehicles [33], adopted to model the costs of purchasing electricity from the grid. Annual maintenance costs for all system components, including chargers, dispensers, PV panels, the ESS, the PCS, the EL, the HT, the FC, and land, were estimated by annualizing capital investments at a discount rate of 5.5%.

Table 2.

PG&E time-of-use pricing rate for business EVs.

The ESS operates within an SoC range of [0.2, 0.8], with charging () and discharging () efficiencies of 95% [35]. The initial and final SoCs are set to 20% of capacity, and the degradation cost of the ESS is set to 0.0035 USD/kWh [36]. For hydrogen production, storage, and conversion on site, the electrolyzer efficiency () is 85% [37], and the FC efficiency () ranges from 50 to 60% [37,38]. The HT operates within a state-of-hydrogen (SoH) range of [0.2, 0.8], with initial and final SoHs at 20% of capacity. The hydrogen dissipation rate is [39], with = 39.75 kg/m3 [40] and = 3.4 kWh/m3 [41]. Table 3 presents the capital cost parameters for the FCS components for investment optimization. Additional parameters are presented in Appendix A in Table A1.

Table 3.

FCS components capital cost parameters for the simulations.

Due to limited real-world FCS demand data, the EV charging and FCEV refueling profiles are derived from general vehicle travel patterns in the 2009 NHTS [47]. The analysis considers commute trips with stochastic arrivals modeled by Poisson processes with rates and , respectively, for EVs and FCEVs. EV chargers are rated at 150 kW [43] and hydrogen dispensers at 5 kg [44]. EVs consume 0.15 kWh/km [48] and pay 0.33 USD/kWh [49] for the charging service, while FCEVs consume 6.67 g/km [50] and pay 3.9254 USD/kg for the fueling service [51].

4.2. FCS Configuration Result

The optimal configuration of the FCS with integrated DERs was evaluated under varying investment budgets. The integer variables and , representing the number of EV fast chargers and hydrogen dispensers, define the FCS infrastructure but introduce computational complexity. To enable tractability, these variables were relaxed to continuous values, and the resulting solutions were validated against an integer projection method to assess suboptimality. The configuration also determines the capacities of the DER components and the hydrogen infrastructure to maximize profitability and ensure reliable service.

4.2.1. Configuration of Service Provision Capacity

The primary objective of the FCS is to provide rapid charging and hydrogen refueling services, so the number of chargers ( and ) has the highest priority. Table 4 presents the results of the configuration of the service capacity for relaxation and projection techniques, under investment budgets ranging from USD 5 million to USD 20 million in a commercial area with a land curvature coefficient set to to replicate the parcel sizes observed for FCS capacity areas in the region. This table shows that the relaxation technique yields fractional solutions, which are impractical, while the integer projection provides practical, implementable values for and . With increasing budgets, and converge to four and five units, indicating a service investment threshold. The total projection results show that increases from three to four at USD 10 million and then stabilizes, while remains at five units, reflecting the higher profitability and flexibility of off-peak hydrogen refueling production.

Table 4.

FCS service capacity configuration using the relaxation technique and the integer projection technique.

4.2.2. Configuration of DER Power Capacity

Table 5 and Table 6 present the DER configurations and the corresponding expected profits by budget, obtained using the relaxation and integer projection techniques, respectively. Although, the number of chargers[dispensers] can not be installed with fractional numbers, Table 5 utilizes them to compare the two techniques. In general, relaxation and integer projection techniques show nearly identical configurations, with a maximum profit deviation of only 0.07%, confirming that integer projection provides a good suboptimal solution.

Table 5.

DER configuration using relaxation technique.

Table 6.

DER configuration using integer projection technique.

Minimal deployment of hydrogen infrastructure is observed across all budget levels. The investments focus on electrolyzers for immediate hydrogen production, with no capital allocated to the HT or the FC. This reflects an on-demand fueling strategy for FCEVs, which prioritizes direct use over storage. The high cost and low efficiency of the components of the hydrogen system likely contribute to their demotion. The results show a consistent prioritization of the solar PV system, the ESS, and the PCS as budgets increase, reaffirming their importance in achieving economic and environmental objectives.

4.3. Numerical Results for FCS Operation

To evaluate the proposed real-time adjustment framework (Phase 4), two base cases are defined in Table 7. Here, W0 and R0 represent deterministic scenarios with perfect foresight. W1–W4 correspond to increasing levels of day-ahead uncertainty in different worst-case realizations, while R1–R4 represent increasing levels of real-time uncertainty in realizations. The degree of uncertainty is reflected by the relative uncertainty set in the worst case and the MAPE in real time. The W0–W4 cases serve as baseline benchmarks to assess the impact of the adjustment strategy in each real-time uncertainty realization in R0–R4. Additionally, the impact of a specific real-time realization on W0 is used as another benchmark to evaluate the performance gain of the adjustment strategy compared with its impact on W1–W4.

Table 7.

Numerical analysis case description.

The uncertainty of solar PV output is assumed to be higher than that of EV [FCEV] demand, as PV generation is subject to weather driven intermittency, while charging [fueling] demand can be reasonably anticipated from daily historical patterns [30,52].

To assess the response of the FCS to uncertainties, Table 8 shows the expected profits for each scenario in both the worst-case scenario and the real-time realization. The analysis proceeds from the top to the bottom of the table to evaluate the impact of the adjustment strategy when actual realization conditions deviate from the expected worst-case scenarios. The worst-case profit column shows the sensitivity to the uncertainty set with a steady decline from W0 to W4, reflecting the increasing conservativeness of baseline planning as the degree of worst-case uncertainty increases. Across columns R0–R4, each represents a distinct real-time adjustment under the corresponding real-time uncertainty realization. In cell W0–R0, the profit matches closely the deterministic case profit in cell W0-Worst-case Profit, as real-time realization R0 aligns with the day-ahead forecast, without a gain. When W1–W4 are updated with the same deterministic real-time information, the adjusted profit remains conservative compared with the deterministic case and decreases from top to bottom as the day-ahead worst-case level increases, despite the absence of uncertainty on day D. Column R1 represents a scenario with real-time uncertainty levels of 5% MAPE for PV generation and 1% for EV [FCEV] demand. When W0–W4 are updated with R1, the adjusted profit in cell W0–R1 is lower than the adjusted profit in cell W1–R1, this is because cell W0–R1 corresponds to a case where the operator predicted a deterministic operation but on day D there is uncertainty in real time. In contrast, in cell W1–R1, the highest adjusted profit is observed in this column, which assumes a matching worst-case real-time prediction error (5% and 1%). The profit then decreases from cell W2–R1 to cell W4–R1, as their respective worst-case assumptions exceed the actual real-time uncertainty in R1. Similarly, realizations R2, R3, and R4, in their respective columns, produce their highest adjusted profits when matched with W2, R3, and R4, respectively, confirming that a closer alignment between the modeled worst-case scenarios and the realized uncertainty leads to superior performance. Case W4–R4 exhibits the highest economic performance, achieving a profit gain of 3.32% and a payback period of 4.43 years. The payback period is calculated according to the method in [53]. For other cases, the gain decreases and the period increases. This underscores the effectiveness of adaptive real-time operational adjustments in improving financial viability in highly uncertain environments. The FCS operator whose worst-case predictions match the actual degree of uncertainty in real time can achieve the highest profits.

Table 8.

Optimal profit realization under proposed robust optimization (commercial area).

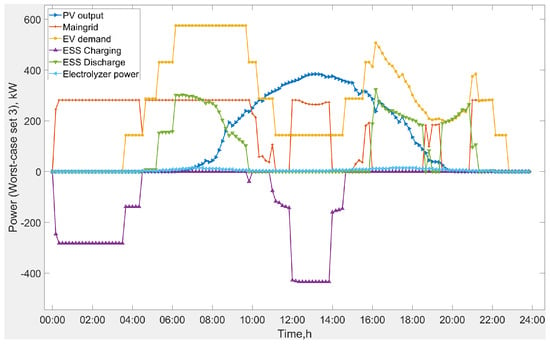

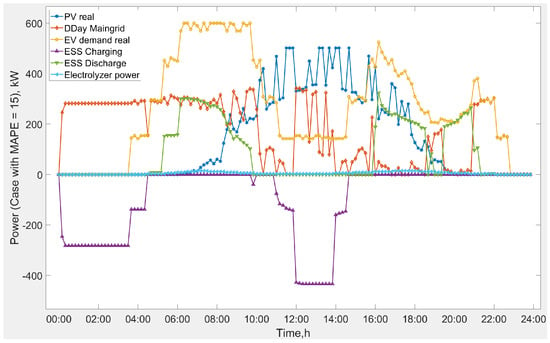

4.4. FCS Power Scheduling

This section analyzes the day-to-day operational strategy of the FCS under the proposed robust optimization framework. Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the power scheduling results for the worst-case scenario for the day ahead and the real-time adjustment scenario, respectively. In both cases, we use case W3 with an investment budget of USD 15,000,000; that is, the solar PV output varies within [85%,115%] and the demand for EV/FCEV fluctuates within [97%, 103%].

Figure 3.

Day-ahead power scheduling under the worst-case robust optimization with case W3 and a budget of USD 15,000,000.

Figure 4.

FCS optimal scheduling under the real random uncertain variable for the proposed strategy.

As shown in Figure 3, solar PV output peaks between 11:00 and 16:00, consistently with typical patterns of diurnal irradiance. These high-output periods also align with the off-peak period of the PG&E TOU pricing scheme for business EVs, allowing for the cost-effective charging of the ESS from the main grid and the solar PV surplus. The solar PV output in the other periods is mainly allocated to EV charging, electrolyzer operation for hydrogen production, and ESS charging. In the early morning and evening, when the PV output is low, the system relies on ESS discharge and grid electricity to supply EV charging and the electrolyzer. In particular, EV charging demand peaks in the late morning and evening, reflecting commuter behavior. This operational dynamic underscores the importance of flexible and reliable supply coordination to manage temporal demand fluctuations.

In practice, real-time operational uncertainties cannot be fully captured by worst-case sets alone. Figure 4 shows the scheduling of FCS power and hydrogen resources using the real-time data update approach. Compared with the structured patterns in Figure 3, Figure 4 shows pronounced fluctuations in solar PV output, EV charging, and FCEV refueling demands. This variability propagates through the system, affecting the utilization of the grid. The effectiveness of the real-time data update and adjustment strategy is demonstrated by its ability to manage increased grid interaction, enabling the FCS to draw more flexibly from the main grid in response to periodic fluctuations.

4.5. Geographical Dynamic Response on FCS Configuration

The geographic location, particularly the associated land lease costs, significantly influences the FCS configuration. To account for their differing land price dynamics, this paper categorizes locations into three types: commercial, industrial, and residential zones.

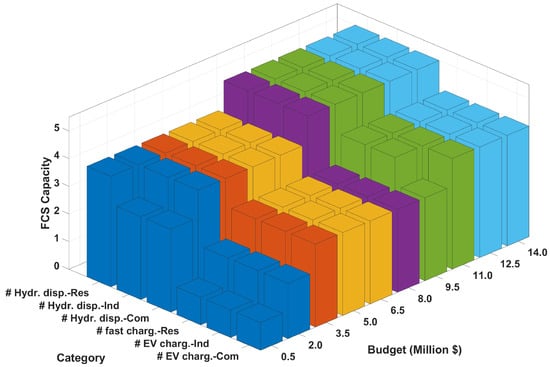

Figure 5 shows the relationship between the investment budget and the location-dependent service capacity, represented by and . The number of fast EV chargers [FCEV dispensers] exhibits location-specific variations. In the high-cost commercial zone, a limited budget results in fewer chargers [dispensers] compared with the residential or industrial zones. However, the number of chargers [dispensers] converges across all location types when the budget is sufficiently large. Once the infrastructure reaches its operational threshold, additional budget increases no longer result in more service components, indicating that further investments do not yield further returns.

Figure 5.

FCS configuration: Service capacity planning.

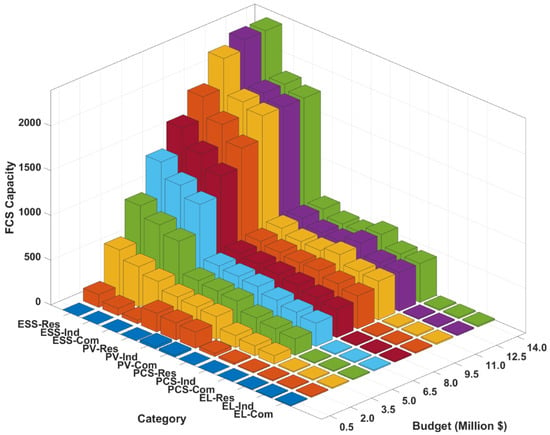

Figure 6 shows the allocation of the investment budget to the components of DERs. Except for the electrolyzer, all component capacities exhibit significant and steady growth with the increase in the budgets, with residential areas demonstrating the highest expansion rates. This is because of the lower land lease costs in residential zones, which facilitates greater deployment of DER systems under a fixed budget. This trend underscores the strategic emphasis on the adoption of decentralized renewable energy, especially in areas with favorable land economics. In contrast, investments in hydrogen production infrastructure remain minimal across all budgets and location types. This means that hydrogen production is dimensioned only to meet baseline FCEV refueling needs, with no prioritization for surplus generation or energy arbitrage. The saturation of solar PV, ESS, PCS, and hydrogen subsystem capacities at higher budgets indicates that capacity expansion becomes economically unjustified beyond certain thresholds.

Figure 6.

FCS configuration: Power and hydrogen capacity planning.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Fast-charging stations (FCSs) are crucial to accelerating the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) and fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). Efficient configuration and operational strategies enhance financial viability, attract private investment, and ensure adequate supply to meet the growing demand for EV charging and FCEV refueling. This study proposed an integrated optimization framework for the joint configuration and operation of FCSs that incorporate distributed energy resources (DERs), including solar PV generation, energy storage systems (ESSs), power conversion systems (PCSs), electrolyzers (ELs), hydrogen storage tanks (HTs), and stationary fuel cells (FCs). Using robust optimization to account for uncertainties in solar PV output and EV [FCEV] charging [refueling] demand, the proposed framework aims to maximize FCS profit while considering investment, peak demand penalties, and operating and maintenance costs. The proposed problem is formulated as a mixed-integer quadratic programming (MIQP) model to ensure a practical, real-world context. To enhance tractability, the MIQP model was relaxed to a convex formulation, enabling efficient computation and scalability. A projection technique confirmed that the relaxed solution remained a good suboptimal solution with a negligible performance gap (<0.1%). The framework effectively determined optimal investment and real-time power scheduling strategies for different budget levels and uncertainty scenarios. Under the most adverse conditions, the real-time adaptation approach achieved a 3.32% increase in operational profit compared with the deterministic benchmark. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed real-time strategy in managing uncertainties more efficiently than static worst-case models, underscoring the practical value of integrating robust optimization with data-driven uncertainty modeling for multi-energy FCS systems.

However, the proposed framework heavily relies on the accuracy of forecasts, particularly for PV output and EV/FCEV arrival patterns. Therefore, future work will focus on enhancing the framework’s robustness, allowing it to perform effectively even with inaccurate forecasts. Another avenue for future research is analyzing the impact of FCS integration on distribution systems to increase hosting capacity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.N.H. and S.-G.Y.; methodology, L.F.N.H. and S.-G.Y.; software, L.F.N.H.; validation, L.F.N.H. and S.-G.Y.; formal analysis, S.-G.Y.; investigation, L.F.N.H. and S.-G.Y.; resources, S.-G.Y.; data curation, L.F.N.H. and S.-G.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F.N.H., K.-M.S. and S.-G.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.F.N.H., K.-M.S. and S.-G.Y.; visualization, L.F.N.H., K.-M.S. and S.-G.Y.; supervision, S.-G.Y.; project administration, S.-G.Y.; funding acquisition, S.-G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) of the Republic of Korea (RS-2025-24523505); in part by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. RS-2024-00398166); and in part by G-LAMP Program of NRF grant funded by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea (No. RS-2025-25441317).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| t | Index of time on an operational day |

| s | Index of scenarios |

| T | Time during the operation period |

| Duration of each time index | |

| Index of fast EV chargers [FCEV hydrogen dispenser] | |

| Investment cost of the FCS [USD] | |

| Total maintenance cost of the FCS components [USD] | |

| Operation cost of the FCS [USD] | |

| Capital cost per unit of the x component [USD per unit] | |

| where | |

| Price of purchasing power from the main grid [USD/kW] | |

| Degradation price for ESS [hydrogen system] | |

| Main-grid overage power price [USD/kW] | |

| Price of charging [refueling] an EV [FCEV] at the FCS [USD/kWh] [USD/kg] | |

| Price of selling back electricity to the main grid [USD/kW] | |

| Maintenance cost of the x component [USD/kW], | |

| where | |

| Revenue of the FCS [USD] | |

| FCS profit [USD] | |

| Invested capacity for the x component, | |

| where | |

| Unit area size of the x component [], | |

| where | |

| Total compact land area for all FCS components | |

| Number of fast chargers [hydrogen dispensers] for EVs [FCEVs] | |

| EV [FCEV] arrival rate at the FCS | |

| Random variable for rapid EV [FCEV] charging [refueling] demand | |

| Expected amount of power delivered by a fast charger at time t | |

| in scenario s [kW] | |

| Expected amount of hydrogen delivered by a hydrogen dispenser at time t | |

| in scenario s [kg] | |

| Rated capacity of a fast EV charger [FCEV dispenser] [kW] [kg] | |

| Solar PV generation at time t in scenario s [kW] | |

| Power purchased from the main grid at time t in scenario s [kW] | |

| ESS charging [discharging] power at time t in scenario s [kW] | |

| Power consumed by the electrolyzer at time t in scenario s [kW] | |

| Power produced by the FC at time t in scenario s [kW] | |

| Main-grid peak power demand [kW] | |

| Hydrogen produced by the the electrolyzer at time t in scenario s [kg] | |

| Hydrogen consumed by the FC at time t in scenario s [kg] | |

| The lower [upper] limit of main-grid power purchase [kW] | |

| The ESS state of charge at time t in scenario s | |

| The HT hydrogen mass flow at time t in scenario s | |

| The minimum [maximum] level of the state of charge of the ESS [kWh] | |

| The minimum [maximum] level of the hydrogen mass in the HT [kg] | |

| Hydrogen higher heating value [kWh/] | |

| Density of hydrogen [kg/] | |

| Efficiency of x, where | |

| Hydrogen dissipation rate | |

| Realization probability in scenario s |

Appendix A. Additional Parameters for Simulations

Table A1.

Additional parameters for simulations.

Table A1.

Additional parameters for simulations.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum main-grid power | 0 kW | |

| Maximum main-grid power | 1500 kW | |

| Maximum solar PV power | 600 kW | |

| Electrolyzer power rating | 130 kW | |

| Electrolyzer hydrogen rating | 65 kg | |

| Fuel-cell power rating | 130 kW | |

| Electrolyzer hydrogen rating | 65 kg | |

| Hydrogen tank hydrogen rating | 1600 kg | |

| ESS maximum capacity | 2400 kWh | |

| EV charger power rate | 150 kW | |

| Hydrogen dispenser rate | 5 kg | |

| Maximum number of EV fast chargers | 15 | |

| Maximum number of hydrogen dispensers | 15 |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Tracking Clean Energy Progress 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-clean-energy-progress-2023 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Tracking SDG7 The Energy Progress Report 2024. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/cdd62b11-664f-4a85-9eb6-7f577d317311/SDG7-Report2024-0611-V9-highresforweb.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report 2024, United Nations Environment Programme. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/46404 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global EV Outlook 2024: Moving Towards Increased Affordability. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/a9e3544b-0b12-4e15-b407-65f5c8ce1b5f/GlobalEVOutlook2024.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Efstathiou, C.I.; Arunachalam, S.; Arter, C.A.; Buonocore, J. Assessing the tradeoffs in emissions, air quality and health benefits from excess power generation due to climate-related policies for the transportation sector. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 064007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Singla, M.K.; Safaraliev, M.; Singh, K.; Odinaev, I.; Menaem, A.A. Advancements and challenges of fuel cell integration in electric vehicles: A comprehensive analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 88, 1386–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayani, R.; Soofi, A.F.; Waseem, M.; Manshadi, S.D. Impact of transportation electrification on the electricity grid—A review. Vehicles 2022, 4, 1042–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelis, E.D.; Carnevale, C.; Marcoberardino, G.D.; Turrini, E.; Volta, M. Low Emission Road Transport Scenarios: An Integrated Assessment of Energy Demand Air Quality GHG Emissions and Costs. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, S.; Di Febbraro, A.; Sacco, N. Management of public transportation demand and maximization of operator revenues using car sharing as a supplement to public transport systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 Smart City Symposium Prague (SCSP), Prague, Czech Republic, 26–27 May 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Qiu, J.; Liu, G.; Yao, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Lu, X. A Fuzzy Logic Approach to Power System Security with Non-Ideal Electric Vehicle Battery Models in Vehicle-to-Grid Systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 21876–21891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silapan, S.; Patchanee, S.; Kaewdornhan, N.; Somchit, S.; Chatthaworn, R. Optimal sizing and locations of fast charging stations for electric vehicles considering power system constraints. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 139620–139631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemian, S.N.; Latify, M.A.; Yousefi, G.R. PEV fast-charging station sizing and placement in coupled transportation-distribution networks considering power line conditioning capability. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 4773–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, G.; Calderaro, V.; Mancarella, P.; Galdi, V. Two-stage stochastic sizing and packetized energy scheduling of BEV charging stations with quality of service constraints. Appl. Energy 2020, 260, 114262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Eom, M.; Kim, B.I. Development of strategic hydrogen refueling station deployment plan for Korea. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 19900–19911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolou, D.; Casero, P.; Gil, V.; Xydis, G. Integration of a light mobility urban scale hydrogen refuelling station for cycling purposes in the transportation market. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 5756–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayasekera, S.C.; Hewage, K.; Razi, F.; Sadiq, R. Fueling tomorrow’s commute: Current status and prospects of public bus transit fleets powered by sustainable hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 66, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Bui, V.H.; Kim, H.M. Optimal sizing of battery energy storage system in a fast EV charging station considering power outages. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2020, 06, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryden, T.S.; Hilton, G.; Dimitrov, B.; de León, C.P.; Cruden, A. Rating a stationary energy storage system within a fast electric vehicle charging station considering user waiting times. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2019, 5, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, M.; Ge, Y.; Shi, W.; Yang, K.; Su, X.; Ding, Y.; Wang, K.; Hu, H.; et al. Flexible Architecture and Hierarchical Power Management for Electrical-Hydrogen Hybrid Storage System Empowered Hub Railway Power System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025. Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedmanesh, A.; Muttaqi, K.M.; Sutanto, D. A cooperative energy management in a virtual energy hub of an electric transportation system powered by PV generation and energy storage. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2021, 7, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimwe H, L.F.; Yoon, S.G. Combined optimal planning and operation of a fast EV-charging station integrated with solar PV and ESS. Energies 2021, 14, 3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Li, G.; Li, P.; Xia, S.; Zhu, Z.; Shahidehpour, M. Coordinated operation of hydrogen-integrated urban transportation and power distribution networks considering fuel cell electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 88, 2652–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Chen, G.; Dong, Z. Planning of hydrogen refueling stations in urban setting while considering hydrogen redistribution. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 58, 6332–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Cai, L.; Pan, J. Expanding EV charging networks considering transportation pattern and power supply limit. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 10, 2898–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; Yoon, S.G. Profit-sharing rule for networked microgrids based on Myerson value in cooperative game. IEEE Access 2020, 9, 5585–5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massucco, S.; Mosaico, G.; Saviozzi, M.; Silvestro, F. A hybrid technique for day-ahead PV generation forecasting using clear-sky models or ensemble of artificial neural networks according to a decision tree approach. Energies 2019, 12, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.P.; Vandenberghe, L. Convex Optimization; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Omer, J.; Poss, M. Combinatorial robust optimization with decision-dependent information discovery and polyhedral uncertainty. Open J. Math. Optim. 2023, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Tan, Y.; Peng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Nakanishi, Y.; Li, Z. Robust coordinated optimization with adaptive uncertainty set for a multi-energy microgrid. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 14, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Dong, Z.Y.; Wong, K.P. Robust coordination of distributed generation and price-based demand response in microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 9, 4236–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourer, R.; Gay, D.M.; Kernighan, B.W. A modeling language for mathematical programming. Manag. Sci. 1990, 36, 519–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Chen, H.; Shahidehpour, M.; Gan, W.; Yan, M.; Chen, L. Distributed expansion planning of electric vehicle dynamic wireless charging system in coupled power-traffic networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 3326–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacific Gas and Electric Company TOU Pricing Scheme. Available online: https://www.pge.com/tariffs/en.html?vnt=tariffs (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Jin, Y.; Acquah, M.A.; Seo, M.; Han, S. Optimal siting and sizing of EV charging station using stochastic power flow analysis for voltage stability. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 10, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Qiu, J.; Tao, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, J. Customized coordinated voltage regulation and voyage scheduling for all-electric ships in seaport microgrids. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2024, 15, 1515–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.P.; Li, P.; Li, Z.L.; Xia, J. Data-driven risk-adjusted robust energy management for microgrids integrating demand response aggregator and renewable energies. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 14, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, M.A.H.; Bauman, J. A comprehensive review of DC fast-charging stations with energy storage: Architectures, power converters, analysis. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2020, 7, 45–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, B.C.; Son, Y.G.; Zhao, D.; Singh, C.; Kim, S.Y. A bi-level approach for networked microgrid planning considering multiple contingencies and resilience. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 5620–5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Taweel, N.A.; Khani, H.; Farag, H.E. Analytical size estimation methodologies for electrified transportation fueling infrastructures using public–domain market data. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2019, 5, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Energy Density of Hydrogen: A Unique Property. Available online: https://demaco-cryogenics.com/blog/energy-density-of-hydrogen/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Gabbar, H.A.; Abdussami, M.R.; Adham, M.I. Optimal planning of nuclear-renewable micro-hybrid energy system by particle swarm optimization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 181049–181073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory. 2024 Annual Technology Baseline: Commercial Battery Storage. Available online: https://atb.nrel.gov/electricity/2024/commercial_battery_storage (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Ibrahim, A.; El-Kenawy, E.S.M.; Eid, M.M.; Abdelhamid, A.A.; El-Said, M.; Alharbi, A.H.; Khafaga, D.S.; Awad, W.A.; Rizk, R.Y.; Bailek, N.; et al. A recommendation system for electric vehicles users based on restricted Boltzmann machine and waterwheel plant algorithms. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 145111–145136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayyas, A.; Mann, M. Manufacturing competitiveness analysis for hydrogen refueling stations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 9121–9142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Jang, G.; Jung, S. A study on sizing of substation for PV with optimized operation of BESS. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 214577–214585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory. 2024 Annual Technology Baseline: Commercial PV. Available online: https://atb.nrel.gov/electricity/2024/commercial_pv (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Trends, Summary of Travel. n.d. 2009 National Household Travel Survey. Available online: https://nhts.ornl.gov/2009/pub/stt.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Yang, Q.; Sun, S.; Deng, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, M. Optimal sizing of PEV fast charging stations with Markovian demand characterization. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 10, 4457–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Park, S.; Choi, J.K. Battery-wear-model-based energy trading in electric vehicles: A naive auction model and a market analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 15, 4140–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, H. Hydrogen refueling of a fuel cell electric vehicle. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 75, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalatbarisoltani, A.; Kandidayeni, M.; Boulon, L.; Hu, X. Comparison of decentralized ADMM optimization algorithms for power allocation in modular fuel cell vehicles. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2021, 27, 3297–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Dong, Z.Y. Robustly coordinated operation of a multi-energy micro-grid in grid-connected and islanded modes under uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2019, 11, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Yoon, G.; Kang, B.; Choi, M.I.; Park, S.; Park, J.; Park, S. Enhancing electric vehicle charging infrastructure: A techno-economic analysis of distributed energy resources and local grid integration. Buildings 2024, 14, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).