Abstract

High-speed solid rotor induction motors (HS-SRIMs) are favored for their robust structure but suffer from significant eddy current losses at high speeds, leading to efficiency reduction and thermal challenges. This study establishes a comprehensive multi-objective optimization framework to address this issue. The eddy current loss characteristics are first investigated using finite element analysis (FEA), focusing on the impact of key parameters like air gap length and rotor slotting. A sensitivity analysis quantifies their influence on motor performance. Subsequently, the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) is employed for multi-objective optimization, aiming to minimize eddy current loss while maximizing efficiency and electromagnetic torque. The optimization results demonstrate a significant improvement: a reduction in eddy current loss of 59.8%, an increase in efficiency of 17.2%, and a boost in output torque of 50.8%. Coupled electromagnetic–thermal simulations further validate a substantial decrease in operating temperatures. The proposed method provides an effective design approach for high-performance HS-SRIMs.

1. Introduction

High-speed motors, characterized by their high power density and compact size, have become pivotal components in a wide range of modern industrial applications, including aerospace, precision machining, and energy systems [1]. Among the various high-speed motor topologies, the solid rotor induction motor (SRIM) has garnered significant attention due to its simple, robust, and monolithic rotor structure. This construction inherently eliminates the risks associated with rotor windings and permanent magnets, such as winding fatigue at high centrifugal forces and demagnetization, making it exceptionally suitable for high-speed operation [2,3].

However, the widespread adoption of high-speed SRIMs is impeded by a critical challenge: significant eddy current losses within the solid rotor. These losses, which increase proportionally with the square of the supply frequency, become the dominant source of inefficiency and heating at high speeds [4]. The resulting temperature rise not only reduces overall motor efficiency but can also degrade insulation materials, induce thermal stress, and ultimately compromise the motor’s operational reliability and lifespan [5]. Therefore, the effective mitigation of rotor eddy current losses is a fundamental requirement for advancing high-speed SRIM technology.

Traditional approaches to loss reduction have often relied on parametric studies of single variables, such as adjusting the air gap length or introducing rotor slotting [6,7]. While these methods can yield improvements in one aspect, they frequently lead to detrimental trade-offs in other critical performance metrics, such as electromagnetic torque and power factor. Furthermore, this design process is typically reliant on engineer experience and iterative finite element analysis (FEA), which is computationally expensive and prone to settling into local optima, making it ill-suited for complex multi-objective optimization problems [8,9,10]. It is worth noting that sophisticated modeling approaches, which accurately capture complex electromagnetic phenomena like the current displacement, are crucial not only for dynamic regimes such as direct starting [11] but also form the foundation for high-fidelity steady-state performance analysis and optimization.

In recent years, intelligent optimization algorithms have been increasingly applied to electrical machine design. For instance, sequential subspace and other multi-objective optimization strategies based on genetic algorithms have been successfully implemented for rim-driven thrusters and other motor types [12,13]. Furthermore, methods combining sensitivity analysis with advanced metaheuristics like the Multi-Objective Whale Optimization Algorithm (MOWOA) have demonstrated significant performance improvements in permanent magnet motor designs [14,15,16,17,18,19]. However, the majority of these sophisticated optimization studies focus heavily on permanent magnet machines, leaving a considerable gap in the systematic, multi-objective optimization of high-speed SRIMs.

Internationally, two research groups have been particularly influential in advancing SRIM technology. The group led by Prof. Pyrhönen in Finland has made profound contributions to the modeling and analysis of loss mechanisms in high-speed SRIMs. Their work on the “Virtual Permanent Magnet Harmonic Machine” model provides a sophisticated theoretical framework for extracting and mitigating rotor harmonic eddy current losses [20,21], and they have also explored innovative asymmetric windings to suppress current unbalance [22]. Concurrently, the group led by Prof. Gulbahce in Turkey has pioneered advanced rotor structuring techniques. Their research on axially slitted and shielded rotor designs, as well as slotted rotors aimed at improving efficiency and reducing harmonic effects, provides valuable practical pathways for performance enhancement [23,24]. Despite these significant contributions, a comprehensive design framework that integrates a systematic sensitivity analysis, a multi-objective optimization specifically targeting the trade-offs between eddy current loss, efficiency, and torque for HS-SRIMs, and a coupled electromagnetic–thermal validation remains largely unexplored.

To address this research gap, this study proposes a comprehensive multi-objective optimization framework for a high-speed SRIM. The work systematically investigates the characteristics of rotor eddy current losses and their sensitivity to key structural parameters, including air gap length, number of rotor slots, slot width, and slot depth. Building on this analysis, a multi-objective optimization is performed using the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), aiming to simultaneously minimize rotor eddy current loss while maximizing motor efficiency and electromagnetic torque. Finally, the optimized design is rigorously validated through coupled electromagnetic–thermal simulation, demonstrating significant improvements in both electromagnetic and thermal performance. The proposed methodology establishes a robust and efficient design approach for high-performance HS-SRIMs, effectively balancing multiple competing objectives.

2. Eddy Current Loss Characteristics of HS-SRIMs

2.1. Basic Parameters of the Motor

This study focuses on a high-speed smooth solid rotor induction motor with a rated power of 4 kW and a rated speed of 12,000 r/min. A simulation model was established using finite element software. The basic parameters of the motor are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Motor parameters.

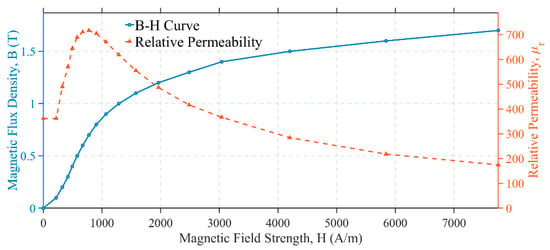

The B-H curve of 40# Steel is shown in Figure 1. Due to the magnetic saturation effect, its permeability varies with the change in magnetic field.

Figure 1.

The B-H curve of 40# Steel.

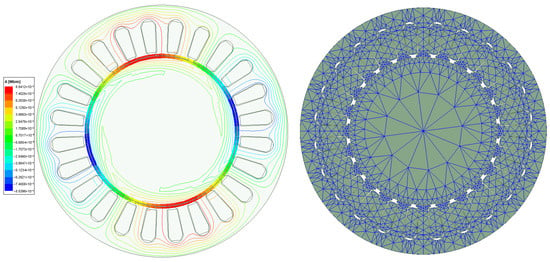

As shown in Figure 2, the magnetic flux line distribution of the prototype under rated operating conditions (slip s = 0.05) is presented. Owing to its characteristic of being both magnetically permeable and electrically conductive, the magnetic circuit and electric circuit in the rotor region are integrated into one, resulting in no fixed path for the magnetic flux lines. Induced eddy currents are generated in the solid rotor under the action of the magnetomotive force on the stator side, with a relatively obvious skin effect. A large amount of eddy current loss is thus produced on the rotor surface, and there is still no fixed path for the magnetic flux lines.

Figure 2.

Mesh Generation and Magnetic Flux Line Distribution of the Motor Under Rated Operating Conditions.

A finite element model was established in ANSYS Maxwell 2022 R1with automatic mesh generation. The final mesh for the motor cross-section comprised approximately 15,000 triangular elements. A key aspect of the meshing strategy was to ensure the accurate resolution of the eddy current distribution within the solid rotor. Given the high operating frequency (400 Hz), a significant skin effect is present. To adequately capture the rapid decay of electromagnetic fields within this depth, the mesh on the rotor surface was locally refined with three layers of elements. The thickness of the first layer was set to 2.5 mm, ensuring that multiple elements span the skin depth for high solution accuracy.

2.2. Material Properties and Temperature Dependence

The accurate modeling of electromagnetic and thermal behavior necessitates a precise definition of material properties, particularly their dependence on temperature.

Rotor Material: The rotor is constructed from 40# steel (AISI 1040). Its B-H curve, which exhibits nonlinear saturation characteristics, is directly imported from the ANSYS Maxwell material library. The electrical conductivity (σ) of 40# steel at 20 °C is 5.8 × 106 S/m. To account for temperature effects in the electromagnetic model, the conductivity is adjusted using a linear temperature coefficient (α) of 0.006/°C, as described by:

where T is the temperature in °C. This adjustment is crucial as the increase in rotor temperature significantly affects the eddy current distribution and loss.

Stator Material: The stator core is made of laminated silicon steel DW540_50. Its B-H curve, also accounting for magnetic saturation, is sourced from the ANSYS Maxwell material library. The core loss parameters (K~h~, K~c~, K~e~) for calculating hysteresis, eddy current, and excess losses are defined within the software’s Steinmetz model.

Implementation in Multiphysics Models:

(1) Electromagnetic (EM) Model: The temperature dependence of the rotor conductivity, as defined by Equation (1), is implemented in the Maxwell transient solver. For each time step, the solver considers the local temperature field (from the coupled thermal analysis) to update the electrical conductivity of the rotor, thereby creating an electro-thermal feedback loop. The stator windings’ resistivity is also defined with a temperature coefficient of 0.00393/°C to accurately compute copper loss.

(2) Thermal Model: In the ANSYS Workbench steady-state thermal analysis, the material properties are defined as temperature-dependent. The thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity of all materials (40# steel, DW540_50 lamination, copper, and insulation) are assigned from the ANSYS engineering data library, which incorporates standard temperature-variant data for these engineering materials.

2.3. Influence of Air Gap Length on Rotor Eddy Current Loss

In the electromagnetic design of HS-SRIMs, the air gap length has a significant impact on rotor eddy current loss and the overall performance of the motor: appropriately increasing the air gap length will increase the magnetic reluctance of the air gap magnetic field. When the stator excitation magnetomotive force remains unchanged, the amplitude of the air gap magnetic density decreases. Since the rotor eddy current loss is positively correlated with the square of the air gap magnetic density, the eddy current loss decreases accordingly.

However, an excessively large air gap length will disrupt the balance between the motor’s magnetic circuit and electric circuit: first, the air gap magnetic reluctance increases significantly, requiring the stator to provide a larger excitation magnetomotive force, which leads to a sharp increase in the excitation current (reactive current). This not only increases the stator copper loss but also reduces the power factor, resulting in a decrease in electrical energy utilization efficiency; second, the excessive reduction in air gap magnetic density weakens the motor’s electromagnetic torque output. When the volume and speed remain unchanged, the torque density decreases, failing to meet the high torque density requirements of high-speed motors.

Therefore, the air gap length must be adjusted within a reasonable range. Taking the prototype used in the research as an example, the minimum value of its air gap length is determined by mechanical safety.

where represents the dynamic eccentricity, which is generally 0.1% of the rotor diameter; represents the thermal expansion increment—for 40# Steel, it is approximately 0.02 mm when the temperature rises by 150 °C; and represents the assembly tolerance, which is generally 0.02 mm.

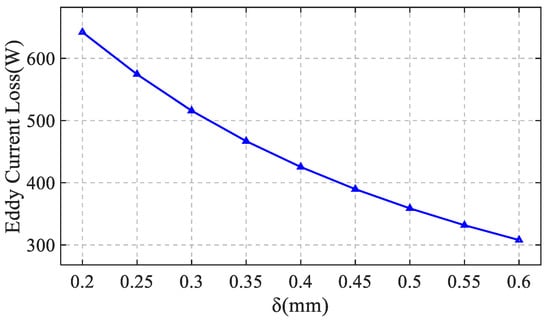

As shown in Figure 3, it presents the variation in the total rotor eddy current loss when the air gap length is changed. It can be seen from the figure that as the air gap length increases, the rotor eddy current loss decreases accordingly.

Figure 3.

Variation in Rotor Eddy Current Loss with Air Gap Length.

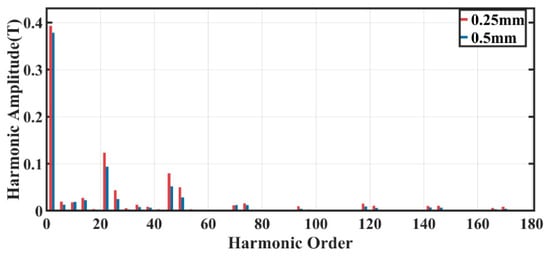

As shown in Figure 4, it presents the Fourier decomposition results of the radial magnetic density on the rotor surface when the air gap length is increased from 0.25 mm to 0.5 mm. The results show that when the air gap length increases, the air gap magnetic reluctance increases accordingly, the amplitude of each order of harmonics decreases, and the amplitude of high-order harmonics decreases more significantly.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Magnetic Field Amplitudes of Each Harmonic Order Under Different Air Gap Length.

2.4. Influence of Rotor Slotting Parameters on Rotor Eddy Current Loss

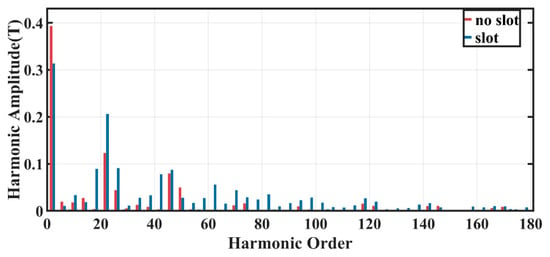

After the rotor is slotted, rotor tooth harmonics are introduced into the air gap magnetic field, with the harmonic order of kZ2 ± p and the rotor-side frequency of sf. As shown in Figure 5, it presents the comparison between the FFT decomposition of the radial magnetic density on the rotor surface when the rotor slot width b = 1.5 mm, slot depth h = 12 mm, and number of slots Z2 = 20, and the FFT decomposition of the radial magnetic density on the rotor surface when there is no slot.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Air Gap Magnetic Field Amplitudes of Each Harmonic Order Before and After Rotor Slotting.

2.4.1. Influence of Rotor Slot Number on Eddy Current Loss

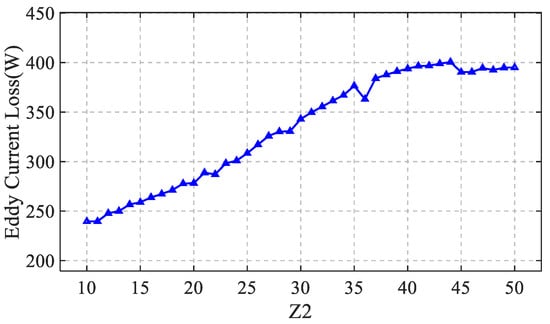

The number of poles of the motor used in the study is 4. Considering that the number of rotor slots increases from 10 to 50, the slot width is fixed at 1.5 mm and the slot depth is fixed at 12 mm. The rotor eddy current loss values under different numbers of rotor slots are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Eddy Current Loss at Different Rotor Slot Numbers.

When the number of rotor slots increases from 10 to 35, the eddy current loss gradually rises. This is because, as the number of slots increases, the slot leakage reactance increases, leading to a corresponding increase in eddy current loss. However, when the number of slots reaches 36, the eddy current loss suddenly drops. The likely reason for this is that the change in slot count avoids resonance with the main stator harmonics, significantly enhancing the harmonic suppression effect. The resulting reduction in loss far exceeds the minor increase caused by leakage reactance, leading to a sudden decrease in loss.

When the number of slots increases from 36 to 44, the suppression effect on the main harmonics reaches its marginal limit, and the increase in leakage reactance once again becomes the dominant factor, causing the loss to resume an upward trend. At 45 slots, the slot count forms a more optimal match with another set of harmonics, again producing a significant harmonic shielding effect, resulting in a second sudden drop in loss.

As the number of slots increases from 45 to 50, the effects of harmonic suppression and the increase in leakage reactance reach a balance, causing the loss to enter a plateau phase and remain essentially unchanged. Therefore, throughout the increase in rotor slot count from 10 to 50, the two main factors influencing eddy current loss are slot leakage reactance and harmonic suppression.

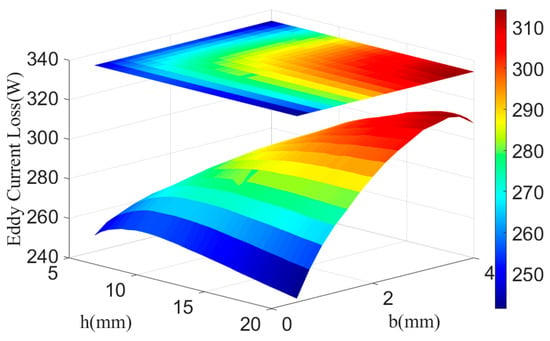

2.4.2. Influence of Rotor Slot Width and Depth on Eddy Current Loss

As illustrated in Figure 7, the eddy current loss exhibits a noticeable increasing trend with the growth of both rotor slot depth and width. The underlying mechanism can be attributed primarily to the reduction in the effective magnetic cross-sectional area of the rotor due to slotting. As more material is removed, the magnetic flux density within the remaining rotor core rises substantially under constant magnetomotive force, according to the principles of magnetic circuits. Since eddy current loss is proportional to the square of the magnetic flux density, this increase in density leads to a significant escalation in losses. Furthermore, the deeper and wider slots constrain the paths through which eddy currents can circulate, resulting in higher current density and additional losses. The slotting also modulates the airgap magnetic field, potentially introducing higher-order harmonics that further contribute to eddy current losses due to their elevated frequencies. This phenomenon highlights the critical trade-off in rotor design: while slotting can be beneficial for controlling certain aspects of motor performance, it simultaneously introduces increased losses due to elevated flux density and harmonic effects.

Figure 7.

Rotor Eddy Current Loss Magnitudes Under Different Rotor Slot Depths and Widths.

3. Multi-Objective Optimization of Solid Rotor Induction Motors Based on Evolutionary Algorithms

Modifying the structure of a solid rotor induction motor to reduce its rotor eddy current loss inevitably alters the motor’s efficiency and electromagnetic torque—two factors critical to motor performance that require comprehensive consideration. In traditional electromagnetic design processes, numerous empirical coefficients must be introduced for repeated iterative corrections. Due to the excessive reliance on initial values and empirical parameters, this design approach tends to trap the process in local optima. Consequently, it is only suitable for single-objective design problems and cannot effectively solve multi-objective optimization tasks. To address this limitation, this study proposes the use of co-simulation with Maxwell 2022 R1 and Optislang 2022 R1 software to perform multi-objective optimization of the solid rotor induction motor, focusing on three key performance indicators: rotor eddy current loss, efficiency, and electromagnetic torque.

The multi-objective optimization design of solid rotor induction motors falls under the category of multi-objective programming problems with multiple constraints. Such problems typically do not have an absolute optimal solution; instead, they yield a set of solutions with different performance priorities, tailored to specific application requirements. Its mathematical expression is as follows:

where F(x) denotes the objective function, x represents the optimization variable, n is the number of optimization objectives, g stands for the number of optimization variables, Ci(x) indicates the constraint condition, and k is the number of constraint conditions. After calculation by the optimization algorithm, Equation (3) can yield a series of solution sets that satisfy both the optimization function and the constraint conditions.

3.1. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

Parameter sensitivity analysis is a method to quantify the degree of influence of changes in model input parameters on output results, and it serves as a key bridge connecting “parameter settings” and “target performance” in applications such as motor optimization design.

The sensitivity analysis in this study was performed using the built-in methodology of OptiSlang 2022 R1 software. OptiSlang employs the Morris Method (a global screening method) and calculates the Coefficient of Prognosis (CoP) to quantify parameter sensitivity.

The process involves the following steps:

(1) Sampling: OptiSlang automatically generates a set of sample points within the predefined ranges of the input parameters (air gap length δ, number of rotor slots Z2, slot width b, and slot depth h) using an efficient Design of Experiments (DOE) strategy, such as the Monte Carlo or Latin Hypercube Sampling.

(2) Simulation: For each sample point, a finite element analysis (FEA) is conducted in Maxwell to compute the output responses (efficiency, eddy current loss, electromagnetic torque, etc.).

(3) Meta-modeling and Analysis: OptiSlang builds a mathematical meta-model (response surface) that approximates the relationship between the input parameters and each output response. The quality of this meta-model is assessed by the Coefficient of Prognosis (CoP). The CoP is a measure of the determinism of the relationship, ranging from 0% (completely stochastic) to 100% (perfectly deterministic). A high CoP value for an output (e.g., 79.7% for eddy current loss in Table 2) indicates that the variations in that output are largely explainable by the variations in the input parameters chosen for this study.

Table 2.

Coefficient of Performance.

(4) Sensitivity Index Calculation: The sensitivity of each output to each input parameter is then quantified. The values presented in Table 2 represent the contribution of each input parameter to the overall determinism (CoP) of the output. A higher value indicates a stronger influence of that parameter on the specific performance metric.

This methodology provides a robust and quantitative basis for ranking the influence of design parameters, ensuring that the subsequent multi-objective optimization focuses on the most critical variables.

In this section, a co-simulation approach using Optislang software and Maxwell software is adopted to conduct a sensitivity analysis of the HS-SRIM. The motor’s air gap length, number of rotor slots Z2, rotor slot width b, and slot depth h are taken as input parameters, while the rotor eddy current loss, motor efficiency , and electromagnetic torque Te are set as output results. The degree of influence of each parameter on each variable is presented in Table 2.

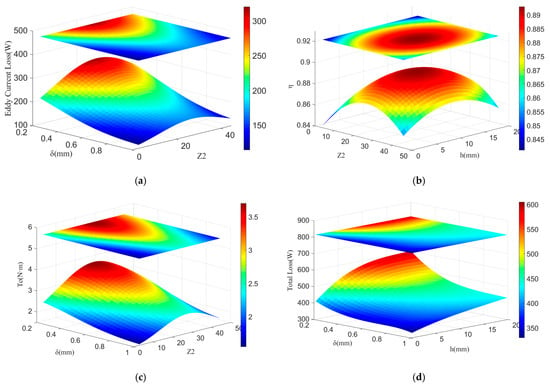

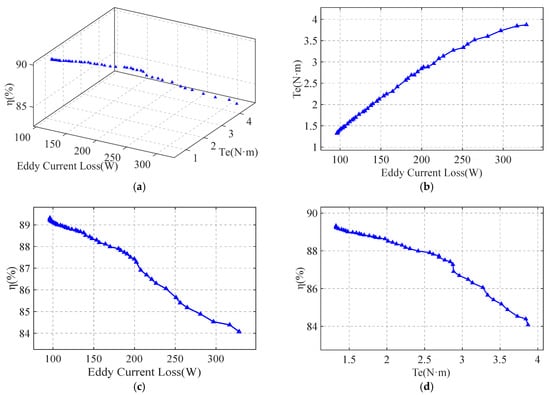

As can be seen from the above data, the number of rotor slots has the greatest impact on motor efficiency, while the air gap length has the most significant influence on eddy current loss and total loss. Regarding electromagnetic torque and output power, the air gap length and the number of rotor slots have a comparable impact on them. Since there are 6 possible pairwise combinations of variables and the amount of data results is too large to be fully presented, for each output result, the two variables with the greatest impact on it are selected, and the 3D surface plots are drawn as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Sensitivity Relationship Between Objective Quantities and Variables: (a) Rotor Eddy Current Loss; (b) Efficiency; (c) Electromagnetic Torque; (d) Total Loss.

3.2. Multi-Objective Optimization Function

When eddy current loss, efficiency, and electromagnetic torque are taken as the three optimization objectives, issues of inconsistent dimensions and numerical magnitudes arise. Therefore, normalization processing is required based on the results of previous finite element calculations.

(1) Maximum Efficiency Objective

(2) Maximum Electromagnetic Torque Objective

(3) Minimum Eddy Current Loss Objective

where f(x) represents the objective value at the current design point, fmin denotes the minimum value among all design points, and fmax stands for the maximum value among all design points. fmin and fmax are obtained through preliminary calculations using finite element software based on the ranges of optimization variables in Table 3, representing the minimum and maximum values of the objective quantities throughout the entire design process.

Table 3.

Feasible Ranges of Optimization Variables.

In summary, based on the above analysis of the influence of structural parameters (air gap length, rotor slotting parameters) on rotor eddy current loss, efficiency, and electromagnetic torque of the HS-SRIM, as well as the normalization processing of the three optimization objectives, the comprehensive multi-objective function constructed in this study is expressed as follows:

where represent the weight coefficients of the optimization objectives. These weight coefficients are selected according to specific application scenarios. In this study, the weight coefficients are set as .

Combined with the original motor design data, reference literature, and engineering experience, the feasible ranges of the optimization variables for the prototype in this study are shown in Table 3. The reason for setting Z2 to 5–50 is: A number of slots lower than 5 would result in a rotor design that is electromagnetically equivalent to a nearly smooth rotor, failing the purpose of introducing this design variable for harmonic control and performance optimization. At the rated speed of 12,000 r/min, the centrifugal forces on the rotor are immense. Increasing Z2 beyond 50 would result in rotor teeth that are critically thin and weak, posing a high risk of mechanical failure due to tensile stress exceeding the yield strength of the rotor material (40# steel). This limit was established based on engineering judgment, preliminary mechanical analysis, and standard practices for high-speed rotor design to ensure operational safety and reliability.

The setting of constraint conditions are as follows.

(1) Structural Constraint Conditions.

The rotor slot shape is a rectangular slot, and the number of slots, slot width, and slot depth should satisfy

where b denotes the rotor slots width, h denotes the rotor slots depth, and Z2 denotes the number of rotor slots.

(2) Magnetic Flux Density Constraint Conditions.

Improve the power density of the solid rotor induction motor, but excessive magnetic flux density will cause saturation of ferromagnetic materials, which in turn increases iron loss and affects the operating performance of the motor. Therefore, during the operation of the motor, the maximum magnetic flux density of the iron core is required not to exceed the saturation magnetic flux density point Bsrp of the ferromagnetic material, that is,

where is the magnetic flux density of the stator tooth, is the magnetic flux density of the stator yoke, and is the magnetic flux density of the rotor.

(3) Current Constraint Conditions.

Affected by the wire specifications, the maximum allowable current of the winding shall satisfy the following relationship

where Imax refers to the maximum allowable current of the winding, Sc refers to the cross-sectional area of the wire, and Jsmax refers to the maximum allowable current density of the wire, whose value is related to the motor’s operating state and heat dissipation structure.

(4) Rotor Mechanical Strength Constraint Conditions.

Constrained by the rotor’s mechanical strength, the rotor linear velocity shall satisfy the following relationship

where is the rotor angular velocity, and vmax is the maximum linear velocity allowed by the rotor material strength.

3.3. Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithm

By integrating the optimization design objectives, optimization variables, and constraints, the multi-objective optimization design model for the HS-SRIM is obtained as follows:

As can be seen from Equation (12), the multi-objective optimization design of the HS-SRIM is a complex nonlinear optimization problem, involving multiple optimization variables with mutual coupling between parameters and variables. The Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), the most commonly used in multi-objective evolutionary algorithms, is adopted for solving this problem, which can effectively obtain the Pareto optimal solution of the model. NSGA-II is based on the basic process of genetic algorithms and includes evolutionary operations such as selection, crossover, and mutation. It iteratively searches for the optimal solution by simulating the “survival of the fittest” mechanism in biological evolution. Different from single-objective genetic algorithms, NSGA-II introduces non-dominated sorting and crowding distance, which are specifically used to handle the problem of objective conflicts in multi-objective optimization. The NSGA-II was implemented using the built-in optimizer in Optislang. The specific parameters were: Population Size = 100, Number of Generations = 200, Crossover Probability = 0.9, Mutation Probability = 0.1.

3.4. Multi-Objective Optimization Scheme

In multi-objective optimization, points on the Pareto frontier represent Pareto optimal solutions. These solutions are characterized by the fact that the performance of any one objective cannot be further improved without deteriorating the performance of other objectives. The Pareto frontier describes the boundary of the optimal solution set in multi-objective optimization problems and reflects the trade-off relationships between different objectives. According to the multi-objective optimization algorithm and combined with the multi-objective optimization algorithm in Section 3.3, the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) evolutionary algorithm was used in Optislang software to optimize the solid rotor induction motor. Finally, the Pareto optimal frontier was obtained as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Pareto Optimal frontier: (a) Efficiency, Eddy Current Loss and Torque; (b) Torque and Eddy Current Loss; (c) Efficiency and Eddy Current Loss; (d) Efficiency and Torque.

Based on the Pareto optimal frontier and comprehensive consideration of optimization objectives, the optimized design scheme for the HS-SRIM is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Optimization Design Scheme.

As shown in Table 5, compared with the smooth solid rotor induction motor before optimization, the multi-objective optimized design scheme reduces the eddy current loss by 59.8%, increases the efficiency by 13.2%, and improves the torque by 50.8%.

Table 5.

Comparison of Motor Performance Indicators Before and After Optimal Design.

4. Rotor Temperature Rise Calculation and Analysis

This section focuses on temperature field calculation, aiming to verify the thermal reliability of the optimized HS-SRIM by calculating and comparing the temperature distribution of motor components before and after optimization. This analysis also reveals the internal heat distribution law of the motor, providing a necessary basis for evaluating the motor’s long-term stable operation performance and guiding subsequent improvements in thermal design.

The thermal analysis was conducted using a steady-state thermal module in ANSYS Workbench 2022 R1. The accuracy of the simulation is highly dependent on the temperature-dependent thermal properties of the motor components.

The following materials were assigned to the respective parts, with their thermal properties (thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity) defined as functions of temperature, sourced directly from the ANSYS Engineering Data Material Library:

(1) Stator and Rotor Core: The laminated silicon steel (DW540_50) and the solid 40# steel rotor were assigned the thermal properties of the built-in material “Steel (Structural)” or its equivalent. This material model accounts for the decrease in thermal conductivity and the increase in specific heat with rising temperature.

(2) Stator Winding: The copper windings were assigned the properties of “Copper” from the ANSYS library. The model includes the well-known decrease in copper’s thermal conductivity as temperature increases.

(3) Insulation: The slot insulation and impregnating varnish were modeled using the thermal properties of “Epoxy Resin” or a similar electrical insulation material from the library, which defines its moderate thermal conductivity.

The heat generation sources, namely the rotor eddy current loss, stator core loss, and winding Joule loss, were mapped from the electromagnetic simulation as volumetric heat generation rates to their respective regions in the thermal model.

The main heat sources inside the motor come from losses. Excessively high temperature rise will have a serious impact on the motor’s operating performance and service life. In this section, ANSYS Workbench is used to establish a one-way electromagnetic–thermal coupled finite element model of the solid rotor induction motor. To facilitate analysis and solution, the following assumptions are made:

(1) The temperature distribution of the motor is symmetric along the circumferential direction, and the boundary conditions of the motor are the same in the circumferential direction;

(2) The air temperature and thermal resistance of the air gap inside the motor are the same;

(3) Small components such as chamfers, keyways, screws, and gaskets on the parts are ignored;

(4) The winding insulation layer is assumed to be uniform; the winding is equivalent to the center of the slot, and the insulation and air are equivalent to the outer layer of the slot;

(5) The internal temperature of the motor is symmetrically distributed along the axial direction;

(6) Mechanical losses are distributed to each component of the motor in proportion;

(7) It is assumed that the heat inside the motor is exchanged only through heat conduction and heat convection, and the influence of radiant heat transfer is ignored.

The heat transfer parameters of each motor component are shown in Table 6. Among them, x, y, and z represent the circumferential, radial, and axial directions of the motor, respectively. Since the stator is formed by laminating silicon steel sheets, its axial heat transfer coefficient differs from those in the circumferential and radial directions.

Table 6.

Heat Transfer Coefficients in the Motor.

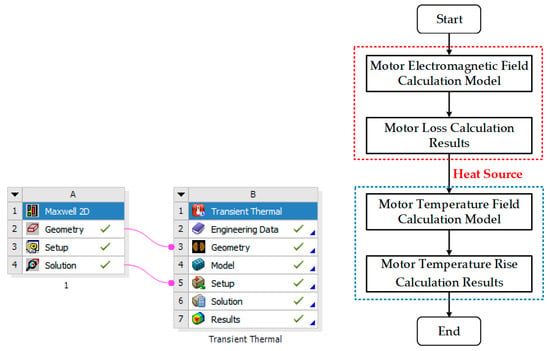

Since the time of the electromagnetic transient process is far shorter than that of the temperature transient process, the losses of each component during the motor’s steady-state operation can be treated as thermal loads when calculating the temperature field. The one-way electromagnetic–thermal coupling finite element model is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

One-way Electromagnetic–thermal Coupled Finite Element Model.

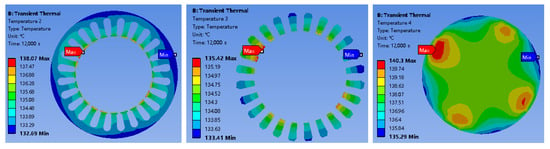

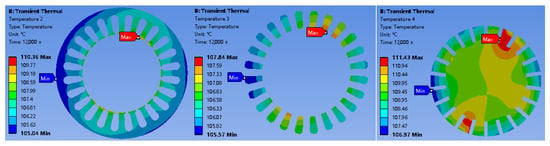

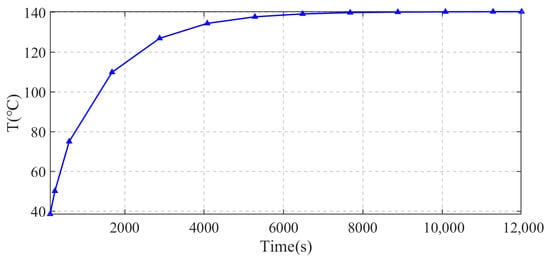

Using the one-way electromagnetic–thermal coupling model, calculations were performed on both the unoptimized motor and the optimized motor. The initial temperature of the motor was set to 22 °C, the total simulation duration was 12,000 s, and an electrical cycle after the motor reached stable operation was selected for thermal load import. Under rated operating conditions, the temperature diagrams of each component of the solid rotor induction motor obtained through the one-way coupling model calculation are shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Temperature of Each Component of the HS-SRIM Before Optimization.

Figure 12.

Temperature of Each Component of the HS-SRIM After Optimization.

As shown in Figure 13, taking the curve of the pre-optimization maximum rotor temperature versus time as an example, the thermal time constant τ is approximately 1250 s. The total simulation time of 12,000 s exceeds 5τ (i.e., 6250 s), thus confirming that the temperatures presented in Figure 11 and Figure 12 represent steady-state values.

Figure 13.

Curve of Maximum Rotor Temperature vs. Time Before Optimization.

The maximum temperatures of each component before and after optimization are shown in Table 7. It can be seen that after optimization, the maximum temperature of the stator of the solid rotor induction motor decreased by 20%, the maximum temperature of the copper windings decreased by 23.1%, and the maximum temperature of the rotor decreased by 17.7%. This indicates that the multi-objective optimization scheme for the HS-SRIM (with rotor slotting optimization as the core) has achieved significant effects. It not only directly reduces the maximum temperature of the rotor itself by reducing the rotor eddy current loss, but also indirectly improves the overall heat conduction and heat balance inside the motor, resulting in a significant decrease in the maximum temperature of key components such as the stator and copper windings. This result fully verifies the effectiveness of the optimization scheme in improving the thermal performance of the motor, which can provide more reliable thermal protection for the long-term stable operation of the motor under rated working conditions and avoid problems such as accelerated insulation aging and reduced mechanical strength caused by local high temperatures.

Table 7.

Maximum Temperatures of Various Motor Components Before and After Optimization.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a comprehensive investigation into the eddy current loss characteristics and multi-objective optimization of a HS-SRIM was conducted. The following key conclusions can be drawn:

(1) Eddy current loss in the solid rotor is significantly influenced by structural parameters, including air gap length, number of rotor slots, slot width, and slot depth. Increasing the air gap length reduces eddy current loss but may adversely affect electromagnetic torque and efficiency. Rotor slotting introduces trade-offs between harmonic suppression and increased leakage reactance, leading to non-monotonic changes in loss with slot number.

(2) A sensitivity analysis revealed that the air gap length has the most substantial impact on eddy current loss and total loss, while the number of rotor slots most significantly affects motor efficiency. Electromagnetic torque and output power are comparably influenced by both air gap length and slot number.

(3) A multi-objective optimization framework based on the NSGA-II algorithm was successfully implemented, integrating electromagnetic and thermal performance objectives. The optimized design achieved a remarkable reduction in rotor eddy current loss by 343.4 W, an increase in efficiency by 17.2%, and an improvement in output torque by 0.97 N·m.

(4) Thermal analysis via electromagnetic–thermal coupling simulation confirmed the effectiveness of the optimization, showing significant temperature reductions in the stator, windings, and rotor. This validates the improved thermal management and operational reliability of the optimized motor.

(5) The proposed methodology demonstrates a robust and efficient approach for the design of high-performance HS-SRIMs, balancing multiple competing objectives and providing a Pareto optimal solution set adaptable to specific application requirements.

Future work may include experimental validation of the optimized design, extension to other types of high-speed motors, and incorporation of more complex thermal or mechanical constraints to further enhance practical applicability.

Author Contributions

This research article contains the authors’ contributions to the writing and completion of such an academic achievement project. The authors Y.D. and J.Z. mainly completed the physical model design, data analysis and writing of the article. The authors Y.X., H.W. and J.T. mainly performed literature retrieval, the literature summary and literature analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Throughout the writing of this dissertation I have received a great deal of support and assistance. I want to thank my supervisor, Jinggong Zhao, whose expertise was invaluable in formulating the research questions and methodology. Your insightful feedback pushed me to sharpen my thinking and brought my work to a higher level.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| b | Rotor slot width [mm] |

| B | Magnetic flux density [T] |

| Bsrp | Saturation flux density of ferromagnetic material [T] |

| Bst | Magnetic flux density of the stator tooth [T] |

| Bsy | Magnetic flux density of the stator yoke [T] |

| Br | Magnetic flux density of the rotor [T] |

| f | Frequency [Hz] |

| F(x) | Objective function vector |

| h | Rotor slot depth [mm] |

| I | Current [A] |

| J | Current density [A/m2] |

| Jsmax | Maximum allowable current density of the wire [A/m2] |

| n | Number of optimization objectives |

| p | Number of pole pairs |

| Z2 | Number of rotor slots |

| s | Slip |

| Sc | Cross-sectional area of the wire [mm2] |

| T | Temperature [°C] |

| Te | Electromagnetic torque [N·m] |

| v | Velocity [m/s] |

| vmax | Maximum linear velocity allowed by the rotor material [m/s] |

| Air gap length [mm] | |

| Efficiency [%] | |

| Electrical conductivity [S/m] | |

| Angular velocity [rad/s] |

References

- Xiao, J.K.; Zheng, G.F.; Liu, P.X.; Ling, D.Q. Review on development status and key technologies of high-speed motors. Electr. Drive 2020, 50, 3–9, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, F.H.; Li, G.F.; He, J.L.; Liu, S. RS-SCBiGRU: A noise-robust neural network for high-speed motor fault diagnosis with limited samples. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23054. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Q.; Zhou, X.; Rong, Y.; Wang, X.; Geng, L.; Yang, Q. Study on the influence of topological structures and soft magnetic materials on the performance of high-speed motors. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2025, 96, 045111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, B.; Yang, Z.; Dong, C.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z. Research on electromagnetic performance and rotor eddy current loss suppression of ultra-low temperature and high-speed permanent magnet motor materials for LNG pumps. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2024, 20, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Luo, S.; Liu, X.; Li, W. The eddy current loss segmentation model of permanent magnet for temperature analysis in high-speed permanent magnet motor. IET Power Electron. 2021, 14, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.H.; Xu, Y.F. Multiobjective optimization design of a brushless excitation synchronous motor based on the Taguchi method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2644, 012065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbika, M. Optimization of air gap length and capacitive auxiliary winding in three-phase induction motors based on a genetic algorithm. Energies 2021, 14, 4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmouditabar, F.; Baker, J.N. Design optimization of induction motors with different stator slot rotor bar combinations considering drive cycle. Energies 2023, 17, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Wang, H.; Ni, S.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Z. Multi-objective optimization design of external rotor permanent magnet synchronous motor for robot arm. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhao, J.; Yan, S. Parameter calculation and rotor structure optimization design of solid rotor induction motors. Sensors 2025, 25, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuhova, M. Modeling of induction motor direct starting with and without considering current displacement in slot. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Ouyang, W.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, R. Sequential subspace multi-objective optimization design of rim-driven thrusters motor based on NSGA. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikhumphun, P.; Seangwong, P.; Fernando, N.; Siritaratiwat, A.; Khunkitti, P. Design optimization of a novel dual-skewed Halbach-array double-sided axial flux permanent magnet motor for electric vehicles. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hua, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhu, Y. Multi-objective optimization design of bearingless interior permanent magnet synchronous motor based on MOWOA. Electronics 2025, 14, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, K.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Xu, T. Design and electromagnetic performance optimization of a MEMS miniature outer-rotor permanent magnet motor. Micromachines 2025, 16, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, D.; Wang, K.; Li, F. Research on pole optimization of semi-inserted dual-rotor axial flux permanent magnet motor for high power density. COMPEL 2025, 44, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, X.; Xie, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q. Characteristic analysis and optimization design of permanent magnet synchronous motor with new rotor structure. Int. Core J. Eng. 2025, 11, 232–247. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, L.; Shi, C.; Zhao, C.; Yang, K. Analysis and optimization of a moving magnet permanent magnet synchronous planar motor with split Halbach arrays. Energies 2025, 18, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Yang, Z.; Sun, X.; Ding, Q. Design and multi-objective optimization of a composite cage rotor bearingless induction motor. Electronics 2023, 12, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, C.; Petrov, I.; Pyrhönen, J.J. Modeling and mitigation of rotor eddy-current losses in high-speed solid-rotor induction machines by a virtual permanent magnet harmonic machine. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2018, 54, 8109912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, C.; Petrov, I.; Pyrhönen, J.J. Extraction of rotor eddy-current harmonic losses in high-speed solid-rotor induction machines by an improved virtual permanent magnet harmonic machine model. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 27746–27755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, C.; Petrov, I.; Pyrhönen, J.J. Design of a high-speed solid-rotor induction machine with an asymmetric winding and suppression of the current unbalance by special coil arrangements. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 83175–83186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbahce, M.O.; Mcguiness, D.T. Shielded axially slitted solid rotor design for high-speed solid rotor induction motors. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2018, 12, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbahce, M.O.; Kocabas, D.A. High-speed solid rotor induction motor design with improved efficiency and decreased harmonic effect. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2018, 12, 1126–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).