Abstract

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) in Translation Quality Assessment (TQA) has emerged as an exciting new line of research hoping to explore the potential of this revolutionary technology within the field of translation studies in general and its effect on translator training ecosystem. The aim of this study is to explore how AI’s evaluation of students’ legal translations aligns with instructors’ evaluations and to look at the potential benefits and challenges of using AI in evaluating legal translations tasks. Ten anonymous copies of instructor-graded English-to-Arabic mid-term exam translations were collected from an undergraduate legal translation course at a Saudi university and evaluated using ChatGPT-4o. The system was prompted to detect the translation errors and score the exam using the same rubric that was used by the instructors. A manual segment-by-segment comparison of ChatGPT-4o and human evaluations was conducted, categorizing errors by type and assessing alignment by comparing the scores statistically to determine if there were significant differences. The results indicated a high level of agreement between ChatGPT-4o and the instructors’ evaluation. In addition, paired sample t-test comparisons of instructor and ChatGPT-4o scores indicated no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05). Feedback provided by ChatGPT-4o was clear and detailed, offering error explanations and suggested corrections. Although such results encourage effective integration of AI tools in TQA in translator training settings, strategic implementation that balances automation with human insight is essential. With proper design, training, and oversight, AI can play a meaningful role in supporting modern translation pedagogy.

1. Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) and artificial intelligence (AI) have recently demonstrated strong performances in translation tasks, particularly as tools for generating translations [1,2,3]. However, only a few studies have explored their capabilities in assessing translations, especially in translator training settings. Such a line of research seems to be motivated by the practical challenges faced by instructors who must assess numerous students’ work while ensuring fairness and consistency, as well as linguistic, cultural, and functional accuracy [4]. According to [5,6], there is a high correlation between AI tools and human judgments, suggesting that reliable AI tools can be used in translation evaluation, consequently, reducing instructors’ workload and promoting evaluation consistency. Other researchers (e.g., [7]) highlighted how AI tools can enhance learner’s autonomy and critical thinking in language education. Despite these studies, a research gap still exists in the literature on the use of AI tools in translation evaluation. First, studies have often focused on global dominant languages such as English, Spanish and Mandarin, overlooking low-source languages such as Arabic. In addition, none of the studies focused on legal translation tasks despite the unique challenges of this field [5,6]. Finally, in most of the studies, there is an overemphasis on grammatical errors over legal coherence and cultural context [8,9].

Therefore, this study aims to address this gap by exploring the potential of using AI tools for Translation Quality Assessment (TQA) in English–Arabic legal translator training contexts.

The following research questions will be explored:

- To what extent does AI’s evaluation of students’ legal translations in an undergraduate legal translation course align with instructors’ evaluations?

- What are the potential benefits and challenges of using AI in evaluating legal translations in translator training settings?

This study aimed to fill the gap found in research regarding the use of AI in translation evaluation, specifically in legal translation from English into Arabic. This study aimed to evaluate whether alignment between AI’s evaluations and human instructors’ assessments serves as a measure of its reliability. If the AI’s evaluations consistently align with human evaluations, this could indicate its potential as an efficient and reliable evaluation tool. This study also aimed to examine the potential benefits and challenges associated with using AI for legal translation evaluation, which can aid translation instructors and students in ensuring more effective integration of technology into the curriculum. Moreover, this study could help AI developers in enhancing the performance of these LLM systems and maximizing their use in various settings.

In summary, this study strived to explore AI tools such as ChatGPT-4o’s potential as an assessor of legal translation within an educational context. By assessing its alignment with the human instructors and identifying its strengths and weaknesses, this research sought to determine whether these tools can be utilized as a reliable assessment tool for translation instructors in academic contexts. As AI continues to develop, its role in education and professional translation must be carefully analyzed to ensure it enhances human expertise rather than becoming a replacement for it.

Given the intricacies of legal translation, an AI evaluator must not only be linguistically proficient but also have the ability to recognize legal nuances and context-specific accuracy. If AI tools prove to be a reliable translation assessment tool, their implementation could streamline grading processes, provide students with valuable feedback, and support instructors in maintaining assessment quality. Conversely, if inconsistencies arise, these findings can help in identifying the limitations of AI-driven evaluations regarding translations and highlight areas for further improvement.

Ultimately, this research contributed to the broader literature on AI’s evolving role in translation education. By evaluating the reliability and practicality of AI tools such as ChatGPT-4o, this study offered insights that could influence pedagogical strategies, AI development, and the future of translation assessment methodologies.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: first, the literature review section highlights the recent studies in the field of AI and translation assessment and the challenges associated with English–Arabic legal translation; this is followed by this study’s methodology and analysis procedures. Next, this study’s results are presented and discussed, providing some practical implications. Finally, this study’s conclusion is presented, highlighting the main findings, study limitations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

Recent studies demonstrate the rapid growth of research on LLM evaluation across domains such as medicine (e.g., LLMs for fact-checking and medical text processing) and e-commerce (e.g., adapting prompts for domain-specific efficiency) [10,11]. These works highlight a broader trend toward systematically testing the reliability, adaptability, and performance of LLMs in specialized contexts. Within translation studies, the integration of AI in translation studies has likewise led to significant developments, particularly in generating and evaluating translations. While AI-driven translation tools have been widely studied, the role of LLMs as TQA tools remains a relatively new area of study. Research in this domain has begun exploring the accuracy, consistency, and reliability of AI-based evaluation methods compared to traditional human assessment and established evaluation metrics. Building on this wider body of evaluation research, the present study contributes by focusing on the relatively underexplored area of legal TQA, thereby extending LLM evaluation into a new pedagogically relevant domain. In this section, a comprehensive overview of existing studies that examined AI’s potential as a TQA, with a particular focus on GPT-based models, is presented.

2.1. AI in Translation Studies

The emergence of AI has significantly influenced the field of translation studies, presenting both unprecedented opportunities and complex challenges. Scholars have increasingly examined how AI technologies are reshaping the way translation is conducted, studied, and conceptualized.

Reference [12] highlighted the transformative role of AI in expanding the scope and methodology of translation studies. With advanced data acquisition, transmission, and analytical tools, AI facilitates the exploration of previously inaccessible historical translator data across different languages and cultures. This has enabled researchers to broaden the research content and discover new subjects within translation studies. AI’s capacity for machine learning, natural language processing, and computer vision allows for faster and more comprehensive analysis, significantly enhancing research efficiency. However, reference [12] also emphasized the challenges that accompany these advancements, such as data inconsistency, the lack of standardized methodologies, ambiguous translator identities, and pressing ethical issues. These challenges demand a more integrated approach, combining the advantages of AI with a detailed investigation of translator behavior, practices, and pedagogy. To achieve this, reference [12] suggested a new research framework that blends knowledge from various fields, encourages critical engagement with AI data, and cultivates a collaborative, digitally skilled research space supporting the combined roles of humans and machines in the evolving field of translation studies.

In parallel, reference [3] explored the broader implications of AI in translation practice, noting its ability to improve accessibility, speed, and cost effectiveness of translation services. AI tools, particularly Neural Machine Translation (NMT) systems, supported global connectivity by making real-time multilingual communication a reality. Nonetheless, the article highlighted the limitations of AI in capturing idiomatic expressions, cultural sensitivity, and contextual nuances where human expertise remains indispensable. Reference [3] advocated hybrid translation models that enable AI’s efficiency to be merged with the interpretive capabilities of human translators. Furthermore, reference [3] called for improved training datasets and robust ethical frameworks to address the biases and potential loss of linguistic diversity brought about by AI systems.

In a study conducted in the same context of our study, reference [13] investigated the challenges faculty members at Saudi universities face when using AI tools (AITs) in teaching translation. Using a qualitative approach, the researcher distributed a 14-item questionnaire to a purposive sample of 50 translation faculty members selected from various Saudi universities during the first semester of 2023. The findings revealed that most participants held positive views toward integrating AITs in translation education. While they acknowledged certain challenges, these were generally seen as manageable, especially as AITs continue to evolve and become more essential to the field. Faculty members also believed that AI has begun offering innovative solutions to long-standing issues in translation instruction. Additionally, the education level was found to significantly influence their professional development and ability to adapt to AITs. However, some responses highlighted areas of concern. Statements like “I can use AITs without outside instruction” and “I often use AI tools in class” received low average scores of 2.80 and 2.70, respectively, suggesting a need for training and greater ease of use. Similarly, the statement “I often involve students in AI practice” scored 2.95, indicating that despite favorable attitudes, actual implementation remains limited, likely due to obstacles such as lack of time, support, or familiarity with the tools.

These studies indicated that AI is more than a technological innovation and it is a force reshaping translation paradigm across research, practice, and education. Reference [12] highlighted the methodological expansion and analytical depth AI brings to translator studies, while [3] stressed the practical benefits and ethical limitations of AI in real-world translation. Complementing these perspectives, reference [13] revealed how translation educators perceive and engage with AI tools in academic settings, drawing attention to the gap between positive attitudes and practical implementation. Together, the studies advocated for a balanced, interdisciplinary approach that harnesses AI’s efficiency while reinforcing the irreplaceable human values of cultural sensitivity, linguistic diversity, and pedagogical adaptability.

2.2. Legal Translation Challenges

The assessment of translation quality in legal contexts presents a complex set of challenges that stem from the specialized nature of legal language, the interplay of multiple legal systems, and the cultural specificity embedded within legal texts [4]. Recent scholarly work highlighted these multifaceted issues and emphasized the critical role that qualified legal translators play in upholding justice in an increasingly globalized world [4,8].

Reference [4] provided an in-depth exploration of the complexities inherent in legal translation, emphasizing that the field extends far beyond mere linguistic transfer. Legal translators act as neutral mediators in multilingual legal systems, ensuring fair communication and legal equality across cultural and jurisdictional divides. The authors argued that legal translation is deeply rooted in the dialectics of language, law, and culture. In fact, each legal system brings with it unique terminology, procedural norms, and interpretive traditions. Legal translators, therefore, must possess not only advanced linguistic skills but also an understanding of comparative law, legal reasoning, and cultural nuances. One key challenge identified is the accurate rendering of legal terms, which often carry system-specific meanings that can be drastically altered if mistranslated. Failure to convey such terms correctly can compromise the legal enforceability of translated documents, especially in high-stakes contexts like contracts or litigation. Additionally, translators must navigate dense legal jargon and archaic phrasing while maintaining the formality and intent of the source document. These intricacies complicate the task of evaluating translation quality, as TQA must account for legal accuracy, linguistic fluency, and cultural appropriateness.

Adding to this discourse, reference [8] focused specifically on the translation of culture-specific legal terms, which represent a persistent challenge in legal TQA. Through an evaluation of English translations in Hatem et al.’s The Legal Translator in the Field, this study highlighted the difficulty of translating culturally embedded concepts that may not have direct equivalents in the target language. According to the analysis, legal translators must excel in three core competencies: comparative legal knowledge, precise legal terminology, and mastery of legal writing styles. The lack of direct equivalence between legal systems often forces translators to engage in a complex decision-making process, balancing fidelity to the source text (ST) with intelligibility and legal relevance in the language of the target text (TT). This highlighted a key issue in legal TQA as evaluators must assess not only the linguistic accuracy of a translation but also its legal and cultural functionality within the target legal system.

Together, these studies revealed that legal TQA is a multidimensional process that requires evaluators to consider a range of factors from terminological precision and syntactic clarity to legal coherence and cultural alignment. As globalization increases cross-border legal interactions, the demand for rigorous and context-sensitive TQA methods continues to grow. Effective translation assessment in the legal field must therefore be guided by interdisciplinary expertise, integrating insights from translation studies, law, linguistics, and cultural analysis to ensure justice and fairness in multilingual legal settings.

2.3. AI as a Translation Quality Assessor

Since the use of AI in translation is relatively new, research on the application of these systems in translation evaluation is rather scarce. Reference [14] proposed a prompting technique called AUTOMQM, standing for Automated Multi-dimensional Quality Metrics, which employs LLM capabilities for reasoning and in-context learning and asks the LLMs to pinpoint and categorize the errors found in the translations. The LLMs investigated in this study were PaLM and PaLM-2, PaLM referring to Particular Language Model. The examples investigated in this study were extracted from two versions of the Workshop on Machine Translation: WMT’22 and WMT’19. The results showed that PaLM-2 models were highly correlated with human judgments with the reference-less PaLM-2 BISON, Baseline Iterated and Stored on Node, being rivalrous with the learned baselines, especially regarding assessing alternative translations of the same sentence. The study claimed that [15]’s GPT-based GPT Estimation Metric Based Assessment (GEMBA) is more accurate at the segment level while the researcher’s PaLM-2 models exhibit higher system level performance.

Reference [16] research explored how AI models are reshaping TQA through real-time feedback mechanisms. They examined the technical integration of AI, its impact on efficiency, error reduction, and how it transforms the translation industry in terms of service quality, cost, and competitiveness. Their research also considered user experience, ethical concerns, and implementation barriers to present a comprehensive view of AI’s influence. The study highlighted several key benefits: enhanced productivity, reduced human error through real-time detection, and continuous improvement owing to fast feedback loops. These factors collectively boosted translation speed, accuracy, and overall quality. In terms of industry impact, AI contributed to more precise and reliable translations, which lead to higher client satisfaction. It also reduces labor costs, making services more cost-effective and competitive. User feedback showed that many translators appreciate the efficiency and quality improvements, although some express concerns over system limitations and the clarity of feedback. Improving usability and accuracy is crucial for broader acceptance. However, challenges remained, especially in handling complex or low-resource languages, addressing ethical concerns like data privacy and bias, and ensuring transparency. Solutions included better training, improved model design, and open communication. Looking ahead, use of AI is expected to become more widespread in translation assessment, with technologies like predictive analytics and AI-driven tools further enhancing capabilities. However, adoption depends on addressing barriers such as standardization, resistance to change, and data protection.

Reference [17] conducted a study investigating the impact of AI on TQA by gathering insights from 450 participants, including professional translators, postgraduate students, and foreign language learners who frequently use AI tools. Using a digital questionnaire and statistical analysis methods such as percentages, means, and t-tests, the research explored how AI integration, ST quality, and the type of AI model influence evaluation accuracy. The study aimed to assess AI’s effectiveness in detecting translation errors and improving evaluation processes while considering the influence of input quality and evaluator expertise. Three hypotheses were tested: that AI improves evaluation accuracy, that ST quality affects AI evaluation precision, and that the type of AI model used significantly impacts assessment outcomes. The results supported all three hypotheses. Over 78% of respondents considered AI essential for evaluating translation quality, over 79% agreed it enhances precision, and 75% believed it reduces bias. Additionally, 61% acknowledged that ST quality influences AI performance, while 63% found AI more reliable when STs were well written. Regarding model type, 65% stated it affects accuracy, with 73% emphasizing the importance of evaluator expertise and 59% highlighting the role of linguistic competence. The study confirmed that AI significantly enhances TQA. However, the effectiveness of AI tools depended heavily on the quality of the ST, the type of AI model used, and the evaluator’s expertise. These factors must be carefully managed to fully realize the benefits of AI in translation evaluation

The reviewed studies proved that AI is emerging as a powerful tool for enhancing TQA, though its application remains in early stages and is accompanied by complex challenges. Reference [14] illustrated how LLMs can effectively replicate human judgment in error categorization, while reference [16] emphasized AI’s broader industry impact through real-time feedback, increased efficiency, and instructor-centered improvements. Reference [17] provided empirical support for AI’s ability to improve evaluation precision while highlighting the influence of ST quality, AI model type, and evaluator expertise. Together, these findings emphasize the growing reliability and utility of AI in TQA, provided its limitations are addressed through improved model training, ethical safeguards, and greater transparency. As technology matures, a balanced approach that integrates AI’s speed and consistency with human critical insight will be key to ensuring rigorous and adaptable evaluation frameworks.

2.4. ChatGPT as Translation Quality Assessors

Research on TQA began exploring how ChatGPT compares with other AI models in providing accurate assessments. Reference [5] aimed to investigate the extent of LLM capabilities operating as English Grammatical Error Correction (GEC) evaluators. They investigated three LLMs, which are GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and LLaMA-2 [5]. The texts used were from the Southeastern English Dialects Archive (SEEDA) dataset. They evaluated the potential of LLMs as assessors by comparing their performance with conventional metrics. The results showed that at the system level, GPT-4 tends to obtain high correlations compared to existing metrics, which highlights its utility in GEC evaluations. In addition, at the sentence level, GPT-4 maintains a relatively high correlation in comparison to traditional metrics, indicating a strong alignment with human judgments. By contrast, GPT-3.5 achieved only moderate correlations, performing noticeably lower than GPT-4, while LLaMA-2 showed the weakest performance, with only limited correlation with human judgments. These findings suggest that although GPT-4 currently outperforms the other LLMs, further work is needed to enhance the reliability of alternative models in GEC evaluation.

A research study by [9] also aimed to evaluate ChatGPT’s ability for GEC found in writings in comparison to commercial GEC products such as Grammarly and cutting-edge models such as GECToR, standing for Grammatical Error Correction with Real-time feedback. The examples were extracted from the Conference on Natural Language Learning 2014 (CoNLL2014) benchmark dataset. The performance was evaluated based on three metrics which were Precision, Recall, and F0.5 score. According to the results, ChatGPT had the highest recall value, GECToR had the highest precision value, and Grammarly achieved a balance between the two metrics with the highest F0.5 score. These results suggested the tendency of ChatGPT to correct as many errors as possible, which could result in overcorrection. On the other hand, GECToR tends only to correct the errors it is confident about, which leaves many errors uncorrected. However, Grammarly’s performance is more stable as it combines the advantages of both ChatGPT and GECToR.

In a study by [15], the researchers aimed to determine whether large language models (LLMs) can serve as effective translation quality assessors. The study primarily investigated GPT-4, but also included other LLMs such as GPT-2, Ada GPT-3, Babbage GPT-3, Curie GPT-3, Davinci-002 GPT-3.5, ChatGPT, Davinci-003 GPT-3.5.1, and GPT-3.5-turbo. The test data and methodology followed the WMT22 metrics, and examples were extracted from the Multidimensional Quality Metrics (MQM) 2022 test set, which included translations from English into German, English into Russian, and Chinese into English. The test set contained 54 translation system outputs, produced either by machines or humans. The researchers proposed GEMBA, a metric that evaluates translation segments in isolation and then calculates the overall score by averaging the segment-level scores at the system level. The results indicated that GPT-4 achieved the highest correlation with human judgments across all three language pairs, followed closely by Davinci-003 and GPT-3.5-turbo. In contrast, earlier models such as GPT-2 and Curie GPT-3 demonstrated significantly lower performance, with their scores often resembling random guessing. This study highlights the potential of advanced LLMs in translation quality assessment, while also identifying limitations in earlier models.

As an advanced AI model, ChatGPT [18] has garnered attention in recent literature for its potential use in TQA. In a study by [19], the researchers compared the translation evaluation of a scientific text excerpt from English to Portuguese using a human evaluation and ChatGPT 3.5. The researchers selected the excerpt from an article and assessed four different Portuguese translations for their study. Two of the translations were from Google Translate and DeepL, one translation was from ChatGPT, and the last one was the official Portuguese translation. The three criteria chosen for the evaluation were fluency, appropriateness and accuracy. For each of these three criteria, they employed a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. The human participants also had to follow the same criteria and evaluate them on a scale. The researchers found that both human evaluators and ChatGPT agreed on which translation deserved the lowest and highest scores, consistently identifying the same translations as the best and worst among those evaluated. Also, the results demonstrated that ChatGPT’s evaluations are more consistent in comparison to human evaluations.

Another study that aimed to find out if ChatGPT can be used as a metric to evaluate translation’s quality was written by [20]. Accordingly, it also aimed to find how the user can develop prompts that can generate reliable evaluations if ChatGPT can indeed be used as an evaluation metric. The researchers used error analysis prompting in ChatGPT against Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU), BERTscore with BERT standing for Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers, BLEURT standing for Bilingual Evaluation Understudy with Representations from Transformers, and Comet. The text used was a test set from the WMT20 Metric shared task in two language pairs: Chinese to English and English to German. The researchers’ in-context prompting strategy was based on chain-of-thought and error analysis. Their research showed that this strategy improves ChatGPT’s evaluation performance. They also showed potential issues that researchers should be made aware of when using ChatGPT as an evaluator.

Similarly, reference [6] investigated the effect of applying ChatGPT-4o for the TQA of human translations based on MQM. The study examined the translations of a literary and non-literary text made by Master of Translation and Interpreting (MTI) students, comparing the assessment of ChatGPT-4o and humans. The focus of the analysis was on accuracy, fidelity and fluency, taking into consideration error counts and overall quality scores. The results of the study indicated the close alignment between ChatGPT-4o and the human evaluators, displaying consistent scoring and qualitative feedback.

Research Gap

The reviewed literature, summarized in Table 1 below, indicated three main gaps. First, most studies have focused on language pairs other than English-Arabic, overlooking the unique linguistic and legal challenges this combination presents (e.g., [5,6]). Second, the research has been largely quantitative, emphasizing AI and LLM performance metrics without considering pedagogical or instructor-centered applications [14,17]. Third, there has been an overemphasis on grammatical errors, with limited attention to deeper issues like legal coherence and cultural context [8,9]. While prior studies often aim to improve AI systems, this study shifts the focus to supporting translation trainees and educators. By examining the challenges of using AI in legal translation assessment, it aims to inform more effective and ethical integration of technology into translation training.

Table 1.

Summary of the literature review.

This study addresses these gaps by examining ChatGPT-4o’s potential as a TQA tool within English–Arabic legal translation training. It aims to support translation trainees and instructors through effective, ethical integration of AI evaluation, balancing technological advancements with the professional and pedagogical realities of legal translation training.

The methodology adopted in this study is described in the next section followed by the analysis and results.

3. Methodology

This study aimed to assess the extent of alignment between AI and instructors’ evaluations of students’ translations in a legal translation course and to explore the potential benefits and challenges of AI as a TQA tool. To achieve these objectives, a mixed-method descriptive case study design was employed. Drawing on [21], the descriptive case study design enabled an in-depth exploration of evaluations within the context of a legal translation course without relying on abstract theoretical generalizations. The combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches ensured comprehensive insights as qualitative data captured instructors’ perceptions and evaluation experiences, while quantitative data compared student scores assigned by AI and human evaluators, enhancing the robustness and comprehensiveness of the findings [21].

3.1. Participants and Context

Two female instructors with PhDs in Translation were purposively selected. Instructor A had 10 years of teaching experience, primarily in interpreting and military translation, and had recently transitioned into legal translation instruction after over a year of professional legal translation practice. Instructor B had nearly 30 years of teaching experience, including three years in legal translation. Both instructors have worked at a Saudi university teaching several translation courses including a Translation of Legal Texts course. It is part of the BA translation program at the College of Language Sciences, King Saud University [22]. The course is a mandatory course, taught in the final semester of the program, and it is designed to develop students’ ability to translate complex legal texts, which are carefully selected to represent a range of legal fields. The course trains 25 students to identify various types of legal documents and their specific features, translate legal texts between English and Arabic with precision, understand legal content and terminology, recognize equivalent legal expressions in the target language, and utilize relevant translation resources. The decision to focus on legal translation in this case study stems from the challenges it presents for translation trainees.

3.2. Procedures

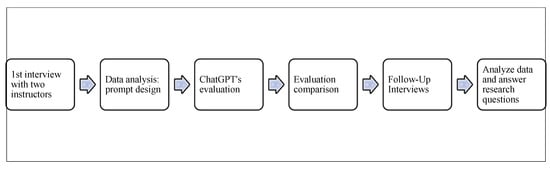

After obtaining ethical approval to conduct this study from the Standing Committee for Scientific Research Ethics at KSU (810-24), this study went through several phases, as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Research phases.

The instructors were approached and were asked for their written consent to participate in this study. Both instructors were informed about the objectives and the procedures of this study, and they were assured that their participation is voluntary, and the data they provide will be used anonymously for research purposes only.

3.3. Initial Semi-Structured Interviews

Initial semi-structured interviews were conducted with each instructor via Zoom (~1 h each). The interview explored the instructors’ qualifications and their experience in legal translation teaching to contextualize their insights. Questions covered their general approaches to teaching and evaluating legal translations, types of texts assigned, criteria for assessing translation quality, and methods for determining error severity. Instructors were also asked about common students’ challenges and recurring errors, how these are addressed, and whether certain legal documents are harder to evaluate. Further questions examined how they handle students’ disagreements about the scoring and feedback, the effectiveness of their feedback in improving student performance, and their preferred techniques for ensuring feedback is understood. Finally, consent was sought regarding the use of anonymized student work for research purposes. Anonymous copies of graded English-to-Arabic mid-term exam translations from 10 students (5 per instructor, representing high, medium, and low performance levels) were collected from the instructors. The two instructors who graded the translations were the same instructors who taught the students in the legal translation course. Since they were handwritten, the translations were digitalized using the OCR feature in Google Translate. The OCR transcriptions were manually verified by two researchers, who independently cross-checked them against the original handwritten texts. Any discrepancies were corrected through consensus before analysis. While error rates were not recorded quantitatively, this process ensured that the final texts used for evaluation were free of observable OCR errors.

3.4. Prompt Design

ChatGPT-4o was selected as the AI tool for this study. It was the first AI tool made available for the public, in May 2024 by OpenAI, providing advanced real-time multimodal reasoning capabilities, speed, and widespread adoption [23]. Its widespread adoption, over 400 million weekly users as of February 2025 [24], reflects its utility across various domains. When using AI tools in general and ChatGPT in particular, prompt design is critical, as studies (e.g., [25,26]) show that prompts specifying evaluation criteria (accuracy, fluency, cultural appropriateness) yield more reliable, human-aligned assessments. Thus, the prompt guided ChatGPT to evaluate student legal translations systematically by comparing the full translation to the source text without omissions and marking errors in square brackets (e.g., The [erroneous term] was used). Under each paragraph, it listed errors with categories and provided comments explaining each error, suggesting corrections, and calculating deductions. Repeated errors were marked in all instances but counted once, missing parts required providing the correct translation with deductions, and incomplete translations were noted with –0.5 points per missing sentence. A structured summary reported content and other error deductions with the overall remaining score.

To ensure clarity, Table 2 below summarizes the scoring system used for each instructor.

Table 2.

AI evaluation error types and deductions per instructor.

For Instructor B, deductions were divided equally between content errors (max 7.5 points) and other errors (max 7.5 points). Overall, this prompt ensured evaluations were consistent, detailed, and aligned with each instructor’s assessment standards in legal translation teaching.

3.5. ChatGPT’s Evaluation and Comparison

Using the identified evaluation criteria derived from the initial interviews, multiple prompts were iteratively tested until an optimal prompt was crafted. The optimal prompt was entered into ChatGPT-4o alongside the source texts and student translations. ChatGPT-4o evaluated each student translation individually, with outputs compiled for analysis. A manual segment-by-segment comparison of ChatGPT-4o and human evaluations was conducted, categorizing errors by type and assessing alignment by comparing the scores statistically to determine if there were significant differences.

3.6. Follow-Up Interviews

A second round of semi-structured interviews (~1 h 44 min each) was conducted via Google Meet to present and discuss the evaluation results, alignment perceptions, potential AI benefits, and challenges. Responses were audio-recorded, transcribed, and thematically analyzed under four categories: alignment, benefits, challenges, and additional comments, with direct quotes extracted to illustrate key views.

3.7. Validity and Reliability

To enhance the validity of this study, multiple data sources were employed. Methodological triangulation was applied through the use of multiple data sources, including interviews with the instructors and performance evaluations, to cross-verify findings and ensure a comprehensive understanding of the research context [21]. Additionally, this research was part of the first author’s MA thesis, conducted under the supervision of a full professor at the College of Language Sciences. Regular consultations and feedback sessions with the supervisor contributed to interpretive validity, helping to refine the analysis and minimize researcher bias.

4. Analysis and Results

This section describes the analysis stage and the findings of this study. It includes analyzing the alignment between ChatGPT-4o and the instructors’ evaluations in assessing the quality of legal translation. This study aimed to determine how closely ChatGPT-4o’s evaluations align with those of the experienced instructors by examining error detection, scoring consistency, and readability of the feedback structure. In addition to alignment, this section also explores the potential benefits and challenges of integrating ChatGPT-4o into the evaluation process, specifically in legal translation assessment.

To achieve this, ChatGPT-4o was provided with the same evaluation criteria as the one followed by the instructors, incorporating their distinct scoring systems. The evaluation criteria were collected during the first semi-structured interviews. The results were analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively to compare ChatGPT-4o’s assessments with those of the instructors, focusing on both score differences and qualitative evaluation patterns. Additionally, the results highlight specific areas of agreement and disagreement, illustrating the strengths and limitations of AI in translation assessment.

This section also examined ChatGPT-4o’s consistency and readability across evaluations, assessing whether its structured feedback enhances reliability and educational value. The findings contribute to the ongoing discussion on AI’s role in translation, particularly in specialized fields like legal translation, where accuracy and contextual understanding are paramount.

4.1. Analysis of Initial Interview

The aim of the first set of interviews was to gather data on the challenges faced by the instructors when evaluating legal translation, as well as to collect the criteria they follow when evaluating. To do this, the interviews were recorded, and notes were taken during the conversations. Afterwards, aspect related to legal translation challenges and evaluation criteria was compiled in a Word document. Then, the responses were categorized by grouping the challenges separately from the criteria and using this data to design the evaluation prompt used in this study. The data was sorted and organized to highlight recurring patterns and themes.

According to the data collected from the interviews, some of the challenges faced when evaluating legal translations mentioned by the instructors include ambiguous writing and wrong or messy formatting or structure, which requires more energy and is time-consuming. One of the instructors even mentioned that the lack of capitalization or multiple spelling errors can hinder the evaluation process as it requires rereading the translation multiple times to figure out what the student meant. Another challenge mentioned is to humanize the evaluation, which means to sympathize with the student without compromising too much. For example, an instructor may choose to overlook minor stylistic issues if the student shows a solid understanding of legal concepts, therefore maintaining objectivity while showing empathy.

The evaluation criteria were based on a structured rubric that divided errors into two main categories: content errors and other linguistic or structural errors. Both instructors included mistranslations, incorrect specialized terms, and omissions as “Content Errors” and grammatical mistakes, structural inconsistencies, and spelling errors as “Other Errors”. However, it is important to note that the scoring system of the two instructors differed slightly. For example, Instructor B considered Content Errors to weigh 50% and the Other Errors also 50%, meaning a maximum of 7.5 points, Instructor A did not have this limit when grading. Another difference is that Instructor B’s text was for 15 points, while Instructor A’s text was for 20 points. The final difference between them pertains to the scoring system itself, as Instructor B deducted 0.25 points per incorrect specialized term and untranslated words. Also, she deducted 0.5 points per mistranslated headings/subheadings and untranslated sentences. Lastly, she deducted 0.25 per pair of mistakes of the same type when it came to grammar, structure, spelling, punctuation, conjunctions, word order, and inaccurate translations.

On the other hand, Instructor A deducted 0.25 points per untranslated word and 0.5 per incorrect specialized terms and per untranslated sentence. Also, she deducted 0.25 points for each error in the grammar, structure, spelling, punctuation, conjunctions, and word order. Table 3 below represents the evaluation criteria of instructors A and B.

Table 3.

Evaluation criteria.

The reasons for the above-mentioned differences lie in what each instructor considers to be more important. For example, Instructor A considers mistranslations of specialized terms to be more important than those of regular terms, therefore allocating 0.5 points to such errors. On the other hand, Instructor B mentioned in the interview that she viewed the mistranslation of terms in general to weigh the same. Further, Instructor B set a 50% limit for each error category (Content and Other) to prevent excessive deductions of the same errors. On the other hand, Instructor A did not set this limit, explaining that she wanted the first exam to serve as a caution and to motivate them to approach their translation work with greater seriousness.

The in-depth discussion with the instructors during the initial interviews led to the next stage of this study, which aimed to design the right prompt to be used with ChatGPT-4o for the evaluation, as will be described in the next section.

4.2. Prompt Design Process

The process of designing an effective prompt for ChatGPT-4o to evaluate legal translations involved several sessions and trials. Several challenges emerged as earlier iterations of the prompt revealed that ChatGPT-4o struggled to recognize the titles of clauses as subheadings, often excluding them from its evaluation. Additionally, when the prompt did not explicitly instruct ChatGPT-4o to include clause titles, it failed to consider them as part of the assessment. Another issue arose with long paragraphs since if the prompt did not clarify that ChatGPT-4o could truncate lengthy content using ellipses, it produced evaluations that were overly summarized, reducing the depth of analysis. Furthermore, prompts that did not specify the inclusion of cut-off translations and their definition led ChatGPT-4o to overlook missing translations at the end of a text, failing to flag them as errors. Similarly, using the phrase “missing translations” instead of “untranslated texts” resulted in ChatGPT-4o not detecting words or sentences that had been left untranslated by students.

These observations highlight the critical role of precision and clarity in prompt design. A well-structured prompt must be precise and specific, ensuring that ChatGPT-4o receives clear instructions on what and how to evaluate. It should provide examples and definitions when necessary to guide the ChatGPT-4o’s interpretation of errors. Using proper terminology is also essential, as slight variations in wording can significantly impact ChatGPT-4o’s ability to identify certain translation mistakes. Moreover, the prompt must offer comprehensive instructions, detailing all aspects that need to be included in the analysis.

Based on the challenges described above, it was found that an effective ChatGPT-4o evaluation prompt should enable the model to:

- Follow all instructions without omission.

- Evaluate the translation from start to finish.

- Adhere to the scoring criteria set for human evaluation.

- Detect all untranslated text, whether words, sentences, or cut-off sections.

- Recognize and include titles, headings, and subheadings (such as clause titles) in the assessment.

- Explain identified errors, comment on why they are considered mistakes, and suggest appropriate corrections.

The prompt used for this study incorporated the same scoring system employed by the human evaluators (the instructors), ensuring that ChatGPT-4o’s assessments were directly comparable to human evaluations. The prompt explicitly instructed GPT-4o to compare the full translation to the ST, mark errors using square brackets, categorize errors according to the predefined criteria, and provide a clear explanation for each identified error. Additionally, GPT-4o was required to suggest corrections and apply the structured scoring system that deducted specific point values for each type of error. The final output from GPT-4o included a breakdown of the deductions and an overall score.

By incorporating these elements into the prompt, ChatGPT-4o was expected to provide a structured and thorough evaluation. The analysis of ChatGPT-4o’s performance compared to the instructors’ evaluations is presented in the following section.

4.3. Analysis Stage

As stated in the methodology, both instructors provided anonymous copies of graded English-to-Arabic translations from mid-term exams completed by their students, along with the instructors’ feedback. From each instructor, 5 translations were selected, resulting in a total of 10 translations being collected. These five were chosen to represent low, medium and high-performance levels. The exams included two texts: an excerpt from a “Power of Attorney” and an excerpt from an “Employment Contract.” According to the instructors, these topics are typically assigned to students at the beginning of the course, as they are considered to be at a more accessible level. As presented in Table 4 below, the ST of the “Power of Attorney” excerpt consisted of 250 words while the “Employment Contract” consisted of 343 words. The grades of the students that were given the “Employment Contract” excerpt, the students of Instructor A, ranged from 8 to 16.75 out of a total of 20 points. On the other hand, the grades of the students that were given the “Power of Attorney” excerpt, the students of Instructor B, ranged from 6 to 13 out of a total of 15 points. Both texts were originally in English, and the students translated them into Arabic.

Table 4.

Table of texts and scores.

The evaluation sessions began by individually entering the students’ translations into ChatGPT-4o, accompanied by the designed prompt and ST. Afterwards, the evaluations given by ChatGPT-4o were collected in a Word document where two tables were created to record all the data of the evaluations. The tables included the ST, the translation of the five students, the evaluations of the instructors and the evaluations of ChatGPT-4o all side by side.

It is important to note that no models were trained or fine-tuned for this study. We used ChatGPT-4o, a pretrained large language model developed by OpenAI [27], accessed through prompting. The model was employed as-is, without additional training, and our focus was on designing a tailored prompt to guide the evaluation of legal translation texts. Therefore, the ‘training’ element in this study refers to the iterative refinement of prompts rather than the training of the LLM itself.

After filling the tables with the segments and their evaluations, the next step was to examine and compare ChatGPT-4o’s evaluation for each translated segment against the instructor’s evaluation. The following coding system was used for the comparison analysis:

- −

- Agreement: This indicates the areas where both the human instructors and ChatGPT-4o reached consensus in their evaluations. Agreement was operationalized based on the detection of the same errors, rather than the exact point deductions. In other words, if both the AI and the instructor identified the same type of error (e.g., grammar, mistranslation, terminology), it was counted as agreement even if the points deducted for that error differed. Stylistic or subjective judgments were not counted as agreement unless they corresponded to a clearly identifiable error.

- −

- Disagreement: This indicates the aspects of the evaluations where the human instructors and ChatGPT-4o did not reach consensus. Two types of disagreement were identified.

- ○

- Errors Detected by Instructor Only: Highlighting the errors that ChatGPT-4o overlooked or ignored but were identified by the human instructors.

- ○

- Errors Detected by ChatGPT Only: Highlighting the errors that the human instructors overlooked but were detected by ChatGPT-4o.

- −

- Other Observations: This highlights notable patterns or insights that emerged during the comparison, which do not fit precisely into the categories above.

In addition, the analysis included a comparison between the scores given by each instructor and by ChatGPT. The comparison results are described below.

4.4. Instructor A vs. GPT’4o

4.4.1. Agreements

Many of the errors above are agreed upon by both Instructor A and GPT-4o. Some examples of these errors include but are not limited to “مارتش” (Martsh—incorrect transliteration of March), “مفعولة الدخل” (affected income), “صدر” (issued), “الأتفاقية” (the agreement—misspelled with hamza), “الموظف” (the employee), and “ويمثل” (and represents). Though they agreed on these errors, sometimes they deducted different amounts of points for one error. For example, GPT-4o deducted half a point for the mistranslation of the term “March” as “مارتش” while the instructor deducted only a quarter of a point as they did not count it as a specialized term. Another example is how the instructor deducted half a point for the mistranslation of “made entered into” as “صدر” (issued) while GPT-4o only deducted a quarter of a point.

4.4.2. Disagreements

Although many errors were agreed upon by both the instructor and GPT-4o, some errors were not. Some of these disagreements were because the instructor detected errors that were not detected by GPT-4o and some because of the opposite, GPT-4o detecting errors that were not detected by the instructor. Therefore, to show these differences, the two sections below discussed the errors detected by the instructor only and the errors detected by GPT-4o only.

4.4.3. Errors Detected by Instructor A Only

Some examples of the errors which were detected by the instructor only include multiple missing punctuations, as GPT-4o appeared to only notice when a punctuation is misused and not when it is missing. Other examples include some spelling mistakes that were not picked up by GPT-4o such as “احمد” (Ahmed), “هويه” (identity), “اليه” (mechanism/procedure), and “الاردنيه” (Jordanian). Another error detected only by the instructor is how one of the students translated the title “Employment Contract” into “عقد العمل” (the employment contract), adding the definite article “ال” (the), which was considered an error worth half a point. In these examples the instructor prioritized punctuation, spelling and grammar.

4.4.4. Errors Detected by GPT-4o Only

There were multiple errors picked up by GPT-4o which were overlooked by the instructor. For example, GPT-4o found the translation “بين كلاً من” (between both of) and “في ما بعد” (in what after) to be errors, correcting them into “بين كل من” (between each of) and “فيما بعد” (hereinafter). GPT-4o also noticed that one of the students translated “Wisam Khalil” into “وسام خالد” (Wisam Khalid) while the instructor did not notice. Further, one student translated the terms “First Party” and “Second Party” into “القسم الأول” (the section one) and “القسم الثاني” (the section two), which GPT-4o flagged and deducted points accordingly. In the previous examples, GPT-4o prioritized grammatical accuracy, orthographic correctness, lexical precision, and appropriate legal terminology.

It was noted that one student made a repetition when she wrote “الموافق الذي يوافق” (the date that agrees), and although it was noticed by both the instructor and GPT-4o, only GPT-4o deducted points on it. Further, the title was translated into “عقد توظيف” (employment contract) by two students; however, in one instance GPT-4o considered the translation acceptable, but in the other, it deducted points for stylistic preferences. GPT-4o also seemed to ignore most spelling mistakes, but it managed to detect structural and stylistic errors that the instructor did not.

To summarize the analysis, there was considerable agreement on many errors, although differences in point deductions were noted. Disagreements emerged, with the instructor identifying errors that GPT-4o overlooked and vice versa. Additional observations indicated that while both evaluations recognized certain issues, only GPT-4o penalized some errors, and it displayed inconsistencies in assessing translations based on stylistic preferences.

4.5. Instructor B vs. GPT’4o

4.5.1. Agreements

Both Instructor B and GPT-4o agreed on many errors. These errors included, but were not limited to, inaccurate rendering of the translation, terminological errors, as well as grammatical errors. For example, both agreed that the title “Power of Attorney” cannot be rendered as just “الوكالة” (the agency) but should instead be translated as “وكالة قانونية” (legal power of attorney). Furthermore, the translations of terms such as “Legal,” “Safety Deposit Boxes,” “Vaults,” and “Real Estate Transactions,” which were rendered as “قضائية” (judicial), “صناديق الإدخار” (savings boxes), “سراديب” (cellars/basements), and “الصفقات العقارية” (real estate deals), were also considered errors by both Instructor B and GPT-4o.

4.5.2. Disagreements

We can see that although most errors were agreed upon by both the instructor and GPT-4o, there were still some errors that were not. Some of these disagreements were because the instructor detected errors that were not detected by GPT-4o and vice versa, GPT-4o detecting errors that were not detected by the instructor. Therefore, to show these differences, the two sections below discussed the errors detected by the instructor only and the errors detected by GPT-4o only.

4.5.3. Errors Detected by Instructor B Only

It can be seen that there were some errors that only the instructor considered to be such. For example, the instructor viewed the translation of “handle” as “يتحكم” (controls) to be an error of wrong meaning, while GPT-4o did not consider it as such. In fact, GPT-4o suggested the word “التحكم” (control/controlling) as the correct translation when one of the students translated the word “control” into “سيطرة” (domination). The instructor also found the phrases “شؤوني التالية” (my following affairs) and “الأمور التالية” (the following matters) to be errors, while GPT-4o did not. Further, “المعاملات البنكية” (banking transactions) was considered an error because the word “البنكية” (bank-related) was not deemed an accurate rendering; the instructor suggested that it should instead be translated as “المصرفية” (financial/banking). In the previous examples, the instructor prioritized semantic accuracy, stylistic appropriateness/word choice, and correct use of terminology.

4.5.4. Errors Detected by GPT-4o Only

We can observe from the table above that GPT-4o tends to give a lot of importance to spelling errors such as those found in “إسم” (name), “الإستثمارات” (investments), “الإتفاقيات” (agreements), and “التي امتلكها” (that I owned), correcting them into “اسم” (name), “الاستثمارات” (investments), “الاتفاقيات” (agreements), and “التي أمتلكها” (that I own), while the instructor gave less value towards such errors. The possible reasons why the instructor ignored such errors may be because they found other types of errors to be more important than simple spelling mistakes, or perhaps because the student already had multiple errors, and the instructor did not wish to be too strict. Another example of an error detected only by GPT-4o is the translation of “hospitalization” as “التنويم” (bed admission/being put to sleep), which was considered correct by the instructor but marked as an error by GPT-4o. Instead, GPT-4o suggested it should be translated into “الدخول إلى المستشفى” (hospital admission) for more precision. The previous examples show that GPT-4o prioritized spelling issues and demonstrated a terminological disagreement with the instructor.

It was noted that Instructor B, most of the time, did not elaborate on the type of error and does not give suggestions for all the errors she detects. She attributed this to the overwhelming number of papers the instructor had to grade and evaluate, the limited time they had to evaluate them, or sometimes she preferred the students to come to her and ask for feedback when they were handed back their graded papers. On the other hand, GPT-4o tended to always specify the type of error, why it was considered an error and always provided suggestions or alternatives for the translations. This is because the prompt that the researcher designed requested of it to offer its reasoning and to give suggestions. Furthermore, it was noticed that GPT-4o’s response to spelling errors was inconsistent. As previously observed with Instructor A’s students, GPT-4o overlooked several spelling errors, whereas with Instructor B’s students, it penalized minor spelling inconsistencies. This inconsistency may be influenced by how the errors are embedded in context. Other possible explanations include how some spelling inconsistencies may stem from token-level misinterpretation or biases in the training data. For instance, certain misspellings may occur frequently online or in informal Arabic usage, leading GPT-4o to treat them as acceptable variations. Furthermore, the model may prioritize more consequential errors over minor orthographic inconsistencies, especially when several types of mistakes are present within the same segment.

4.6. Score Alignment of AI and Human Evaluations

Table 5 below presents the scores assigned by Instructor A and GPT-4o to five students, each evaluated on a 20-point scale, and the scores assigned by Instructor B and ChatGPT-4o to five students, each evaluated on a 15-point scale.

Table 5.

Students’ scores by the two instructors and ChatGPT-4o.

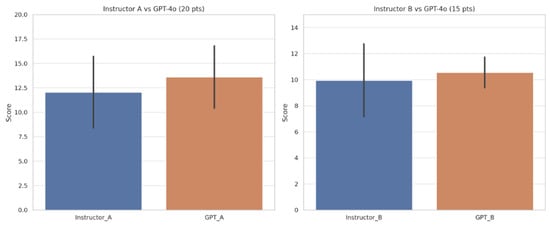

To see if the differences between the instructor’s scores and ChatGPT-4o were statistically significant, a paired sample t-test was conducted, and the p-value was calculated, as shown in Table 6 below. According to [28], t-tests are valid with small sample sizes, especially in paired designs, as long as the differences between pairs are approximately normally distributed. A bar plot comparing the average scores between the instructors and ChatGPT-4o for each group of students is shown in Figure 2.

Table 6.

Score difference of the 10 students.

Figure 2.

Bar plot comparing the average scores between the instructors and ChatGPT-4o for each group.

The results indicated some variance between human instructors and AI assessments. However, the p-value is greater than 0.05, indicating no statistically significant difference between the instructors’ scores and GPT-4o’s scores.

Furthermore, effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d for paired samples using the following formula:

With the small sample size, calculating the effect sizes will help in assessing the extent of the difference between the instructors’ scores and those of GPT-4o, as shown in Table 7 below.

Table 7.

Effect sizes calculated using cohen’s d.

The results revealed a medium effect size (d = −0.54) for Instructor A, indicating that this instructor tended to score students slightly higher than GPT-4o on average. On the other hand, the effect size for Instructor B was small (d = −0.25), suggesting that their scores were more closely aligned with GPT-4o, with only minor differences.

4.7. General Evaluation of ChatGPT-4o’s Performance

One of the most notable aspects of ChatGPT-4o’s performance was its consistency in evaluating student translations. ChatGPT-4o applied the same error categories, point deductions, and feedback structure across all evaluations, which enhances the reliability of its assessments. Each evaluation followed a systematic format, beginning with an assessment of terminological accuracy, followed by grammatical errors, structural weaknesses, and a final summary with a numerical score. This consistency makes ChatGPT-4o’s evaluations easy to read and interpret, particularly for comparative analysis across multiple translations.

Additionally, ChatGPT-4o’s explanations were generally clear and concise, providing direct corrections alongside brief justifications for why an error was flagged. For example, when identifying a grammatical mistake, ChatGPT-4o did not merely state that the word was incorrect but also provided the correct form and a brief rationale for why the change was necessary. This level of explanation may contribute to the educational value of ChatGPT-4o’s assessment, making it useful for student learning and instructional purposes.

However, in some instances, it was noticed that while for the first few students its evaluations were presented in the same format, this was not the case for the latter ones. For example, it managed to present the ST, the TT, the error types, the comment, and the points deducted for all paragraphs and then concluded with presenting the final score calculations as well as the overall comments. This format, however, was only followed in the evaluations of the first three students. In the case of the fourth student, it did not present the ST but included the TT, followed by the errors, comments, points deducted, and final scoring along with the overall comments. As for the evaluation of the fifth student, the formatting changed again but this time it only presented the sentences containing the errors in each paragraph, followed by the error types, comments, points deducted, and the final scoring and overall comments. In other words, while the content and evaluation criteria applied by ChatGPT-4o were consistent, the formatting of the output varied in later sessions. However, when the same prompt and the later students’ translations were re-entered on a different day, it has been noticed that the previously mentioned formatting issue was resolved, and the consistent structure returned. This could indicate that the reason behind the formatting inconsistencies with the later students is due to the usage limit of GPT-4o.

4.8. Perceptions of the Instructors

The following section discusses the potential benefits and challenges of utilizing AI in TQA as well as other opinions that did not fit under the previous two categories. The opinions were according to the perception of the instructors which were collected during the second set of semi-structured interviews.

4.8.1. Perceptions of Alignment Between GPT-4o and the Instructors

Both instructors reflected positively on the level of alignment between their evaluations and those generated by GPT-4o. Instructor B observed that the differences between her assessment and the AI’s were minor and comparable to the variations typically found among human evaluators in the same field. She remarked that the AI’s feedback felt like “the opinion of another instructor” and expressed positive surprise at how often her evaluations aligned with those of the GPT’4o. She stated, “We can rely on it, but not 100%, not yet.” emphasizing that while full reliance may not be advisable at this stage, the consistency and low margin of error are promising. For her, this level of agreement serves as evidence that AI can be beneficial for both instructors and students in academic evaluation. She concluded that the numbers and overall alignment are encouraging and support the tool’s potential for integration in educational contexts.

Instructor A also acknowledged a strong level of agreement between her assessments and AI’s evaluations. She commented, “I found it very interesting. It has potential.” and added, “I think there is a good level of alignment.” She attributed this belief to several factors, including the use of a well-crafted prompt, the detailed evaluation criteria provided to the AI, and the evidence observed in the results. Instructor A also noted AI’s consistency as a key strength contributing to the alignment and supporting the tool’s academic usefulness.

4.8.2. Potential Benefits

Both instructors acknowledged several shared benefits of using AI in TQA. They agreed that AI can effectively complement human evaluation rather than replace it. Instructor A stated, “Yes, they complement each other.” while Instructor B echoed this view, saying, “The AI can complement the work of the human.” This collaborative dynamic allows instructors to maintain oversight while benefiting from AI’s consistency and speed. The researcher also observed that ChatGPT-4o significantly reduces the time required to assess translations by producing detailed evaluations rapidly, supporting its role in streamlining the evaluation process.

Both also emphasized AI’s potential to promote student autonomy and support the learning process. Instructor A shared that some of her students reported improvements when using AI for language assessment, stating, “I want them to be autonomous… you want to give them another source of guidance when it comes to language and sentence structure.” Instructor B similarly noted, “Any feedback can be beneficial—from the teachers and from the AI.” In line with these views, the researcher noted that ChatGPT-4o’s interactive explanations may help students independently explore and understand their errors, thereby fostering learner autonomy.

Another shared benefit was the potential for reducing time and effort in evaluating student work. Instructor B stated, “This is what we need—less effort and accurate result.” while Instructor A viewed AI as a helpful starting point, noting that it could be used as a first step to then validate it [the evaluation] herself as a second step. Both also agreed that a well-crafted prompt leads to meaningful AI responses. Instructor A highlighted that the AI was able to “identify the mistakes, justify why they are considered mistakes, and explain them.” while Instructor B pointed out that “the prompt helped the AI reflect the way a human does when dealing with translations.” The researcher further confirmed that well-crafted prompts played a critical role in output reliability; consistent and accurate results were achievable through careful prompt development and iterative refinement.

After reviewing the AI-generated evaluations, both instructors reported a shift in perspective. Instructor A remarked, “There is potential… it made sense.” and Instructor B noted, “My opinion has changed… I’m more encouraged to use it.”

An additional benefit observed by the researcher is ChatGPT-4o’s potential to support standardized evaluation practices across different instructors. By using a unified prompt aligned with common rubrics, it is possible to achieve more objective and coherent assessments. The AI’s user-friendly interface which allows evaluators to input queries with minimal technical effort was also noted as a practical strength. Furthermore, ChatGPT-4o’s free accessibility, despite daily usage limits, enhances its appeal for academic use, especially in institutions where resources may be limited.

4.8.3. Potential Challenges

Despite these benefits, both instructors highlighted common challenges. They stressed the importance of training, with Instructor A stating the need for “training for professional use,” and Instructor B adding, “It would require training to be familiar with it.” Both highlighted that prompt design is essential to guide AI effectively. Instructor A cautioned that if a prompt is already designed to suit her evaluation criteria the answer might be good while Instructor B affirmed, “It depends on how to guide the AI… the results would still be dependent on humans.” Practical issues were also mentioned, particularly the format of student translations. Instructor A pointed out that it would be “time-consuming if the translations are not provided as a soft copy,” and Instructor B suggested that having typed responses would “make it easier to feed the AI.” The researcher similarly noted that converting handwritten exam translations into a digital format was a time-consuming but necessary step to make the texts suitable for AI input. Although the term “digitization” was not explicitly mentioned by the instructors, this process posed a practical limitation that could hinder the seamless integration of AI tools.

Furthermore, both instructors emphasized that AI may lack the human capacity for judgment and interaction as Instructor B stated, “When it comes to debating and arguing on the errors with the students the AI might not be able to do so.” In other words, it may not be able to support a high level of ongoing interaction between it and the students

Another challenge observed by the researcher was inconsistency in output formatting. While early evaluations followed a clear structure that includes the ST, TT, identified errors, comments, point deductions, and an overall score, later evaluations deviated from this format, even when the same prompt was reused. This inconsistency appeared to be linked to usage limits or server behavior, as re-entering the same input on a different day restored the original structure. Although the core evaluation content remained consistent, these fluctuations in layout present a usability concern when AI tools are applied in formal or comparative assessments.

In addition to benefits and challenges, both instructors expressed openness to experimenting further with AI. Instructor A spoke of “keeping the possibility of using it as a second step,” while Instructor B affirmed, “Everything we should try and then we decide based on the results.” They both acknowledged the rapid development of AI tools. Instructor B remarked, “I think that AI would outsmart us one day,” and Instructor A simply stated, “There is potential.” These views reflect a cautious but growing interest in AI, particularly when used to enhance rather than replace human expertise in academic evaluation.

While the instructors expressed optimism and openness to using ChatGPT-4o, their reflections, along with observed limitations, support the conclusion that the tool is most effective as a supplementary aid, not a substitute for expert judgment. The researcher’s reflections further support the conclusion that ChatGPT-4o is best positioned as a supplementary tool. Its advantages in speed, consistency, user accessibility, and feedback quality and readability are promising, but they must be balanced against the need for human oversight, thoughtful integration, and structured usage protocols. When implemented carefully, AI can serve as a valuable aid to instructors, enriching both teaching practices and student learning experiences

A discussion of the results highlighted in this section is presented next.

5. Discussion

This study explored (1) the alignment between AI tools, i.e., ChatGPT-4o’s evaluations and those of experienced human instructors in a legal translation course, and (2) the potential benefits and challenges of its use in such contexts. This section discusses these findings in light of previous research highlighting their pedagogical implications.

5.1. Alignment with Instructor Assessments

Overall, the findings demonstrated strong alignment between ChatGPT-4o’s evaluations and instructor assessments, particularly in identifying key content and linguistic errors. With the right prompt, ChatGPT-4o consistently recognized and categorized mistranslations, incorrect specialized terms, omissions, and grammatical inconsistencies. Statistical analysis confirmed that there was no statistically significant difference between the scores given by the instructors and ChatGPT-4o. These results mirror those of [6,19,29], who reported strong correlations between AI-generated and human evaluations in diverse translation contexts.

Notably, reference [19] found ChatGPT evaluations often mirrored human assessments and sometimes outperformed them in consistency, which aligns with this study’s observation of ChatGPT-4o’s structured and systematic approach. However, while reference [19] focused primarily on general translation contexts, the current study extends these findings by demonstrating ChatGPT-4o’s capability in specialized domains such as legal translation, provided that prompt design is sufficiently detailed. This contributes new evidence to the literature, supporting the view that AI tools hold significant potential for TQA beyond general language use, as also discussed by [29].

Despite overall alignment, qualitative analysis revealed notable differences. ChatGPT-4o sometimes overlooked errors that instructors detected, while being overly stringent in penalizing minor structural or stylistic issues. For example, it deducted points for spelling inconsistencies that human evaluators either ignored or addressed leniently, factoring in student intent and pedagogical considerations. This finding is consistent with [9,20], who emphasized that AI feedback can be overly rigid and fail to distinguish between critical and non-critical errors, potentially undermining learning if not accompanied by human judgment.

These discrepancies highlight the fundamental difference between rule-based AI systems and human evaluators, who bring professional judgment informed by context, course objectives, and learner needs. This suggests that customizing AI prompts with course-specific instructions and specialized legal terminology lists could adjust AI evaluation sensitivity to better reflect instructor expectations, an approach also supported by [25,26].

Furthermore, the findings demonstrated the critical role of prompt design. During the pilot phase, ambiguous prompts led ChatGPT-4o to ignore untranslated clauses or titles, but refining prompts improved evaluation performance significantly. This finding is consistent with the work of [25,26], who emphasized that well-structured, translation-specific prompts yield evaluations more aligned with human judgment, particularly in specialized texts. Thus, the current study reinforces the need for prompt engineering expertise to harness AI’s full potential in TQA.

It should be noted that the prompts provided to the AI were directly informed by the instructors’ evaluation criteria, and as such there is a possibility of prompt-induced bias. This alignment may have contributed to higher agreement levels between AI and human evaluations. While this design choice ensured consistency with the grading framework used in the course, it also limits generalizability, as the results may differ if alternative prompts or evaluation rubrics are applied. Future research should therefore examine the stability of AI evaluations across varied prompt designs and independent scoring criteria.

In general, while ChatGPT-4o demonstrates potential to complement human evaluation, it should not replace instructor judgment, particularly given its limited contextual empathy and pedagogical flexibility. Therefore, consistent with [9,20], this study supports a hybrid evaluation approach where AI tools enhance, rather than replace, human judgment.

5.2. Benefits and Challenges

This study identified several benefits of using ChatGPT-4o, aligning with broader trends in the TQA literature. Firstly, enhanced learner autonomy emerged as a key benefit that was pointed out by the instructors. Structured and immediate AI feedback supports student self-reflection and correction, echoing [7], who emphasized the role of digital tools in fostering self-directed learning in language education.

Secondly, time efficiency was evident. According to the instructors, ChatGPT-4o’s capacity to deliver detailed evaluations rapidly can reduce instructor workload, as also observed by [16], who highlighted AI’s potential for real-time feedback and increased productivity. Although reference [14] did not directly assess time efficiency, their findings on AI’s alignment with human judgment suggest potential for streamlining assessment processes, which the current study confirms within legal translation.

Thirdly, consistency in applying evaluation criteria was a notable strength, with ChatGPT-4o applying the same framework across all samples, minimizing subjectivity. This finding aligns with [17], who concluded that AI evaluations improve precision and reduce bias when guided by clear metrics. However, as shown in this study and echoed by [20], such consistency is contingent upon precise prompt design.

Additionally, the accessibility and intuitive interface of ChatGPT-4o facilitates broader adoption, particularly in resource-limited settings, supporting observations by [3,13] regarding the importance of user-friendly, low-barrier AI tools in educational contexts.

Despite these strengths, several challenges remain. The technical barrier of prompt design is significant, with minor wording variations leading to major output differences. This supports [20,25], who highlighted prompt formulation as a determinant of AI evaluation effectiveness. As suggested in this study, developing standardized prompt templates and providing instructor training on prompt engineering can mitigate this challenge.