Abstract

Understanding and accurately modelling mass transport phenomena in anode-supported solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) is essential for improving efficiency and mitigating performance losses due to concentration polarization. This study presents a one-dimensional, isothermal, multi-component diffusion framework based on the Stefan–Maxwell (SM) formulation to evaluate hydrogen, water vapour, and nitrogen transport in two different porous ceramic support materials: calcia-stabilized zirconia (CSZ) and magnesia magnesium aluminate (MMA). Both SM binary and SM ternary models are implemented to capture species interactions under varying hydrogen concentrations and operating temperatures. The SM formulation enables direct calculation of concentration polarization as well as the spatial distribution of gas species across the anode support’s thickness. Simulations are conducted for two representative fuel mixtures—20% H2 (steam-rich, depleted fuel) and 50% H2 (steam-lean)—across a temperature range of 500–1000 °C and varying electrode thicknesses. They are validated against experimental data from the literature, and the influence of electrode thickness and fuel composition on polarization losses is systematically assessed. The results show that the ternary SM model provides superior accuracy in predicting overpotentials, especially under low-hydrogen conditions where multi-component interactions dominate. MMA consistently exhibits lower polarization losses than CSZ due to enhanced gas diffusivity. This work offers a validated, computationally efficient framework for evaluating mass transport limitations in porous anode supports and offers insights for optimizing electrode design and operational strategies, bridging the gap between simplified analytical models and full-scale multiphysics simulations.

1. Introduction

Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) are gaining significant attention as a promising energy conversion technology capable of directly converting chemical energy from fuels into electricity and heat with high efficiency [1]. Operating at high temperatures, typically between 600 °C and 1000 °C, SOFCs exhibit remarkable fuel flexibility, allowing them to utilize various fuels, including hydrogen, natural gas, syngas, and even hydrocarbon fuels, through internal reforming within the anode [2]. This high operating temperature also facilitates the use of inexpensive electrode materials, reducing reliance on rare elements such as platinum [1].

Understanding the intricate transport phenomena within SOFCs is crucial for improving their efficiency and performance [3]. Among these phenomena, the transport of gas species through the porous electrode materials (anode and cathode) is of particular importance [4]. Mass transport limitations in the porous structure lead to concentration gradients, which, in turn, cause a decrease in the partial pressures of reactants at the active electrochemical reaction sites and an increase in the partial pressures of products [5]. This results in a performance loss known as concentration polarization or overpotential, diminishing the overall cell voltage and power output [6].

The anode-supported SOFC configuration is widely adopted due to its mechanical robustness and potential for operation at lower temperatures compared to electrolyte-supported designs [7,8]. The microstructure of the porous anode, including its porosity, pore size distribution, and tortuosity, significantly influences the gas diffusion process and, consequently, the cell performance [9,10,11]. An appropriate microstructure is essential for ensuring sufficient transport of fuel and products to and from the reaction zones, thereby minimizing the concentration overpotential.

Modelling the transport of multiple gas components in such porous media presents a complex challenge [12]. Several mathematical models have been developed and applied to simulate mass transfer in SOFC electrodes, including Fick’s Model (FM), the Stefan–Maxwell (SM) model, and the Dusty Gas Model (DGM) [13,14,15,16]. FM assumes binary diffusion and ideal gas behaviour, which makes it appropriate for systems where one species is predominant or present in large excess relative to others. However, the SM and DGM are considered to be more rigorous for describing multi-component diffusion in porous structures, accounting for interactions between all species and the pore walls. Studies comparing these models have shown varying degrees of agreement, depending on the fuel composition and operating conditions [17,18], highlighting the differences in their predictions [3,16,19].

The microstructural properties of porous electrodes (i.e., porosity, tortuosity, and pore size distribution) are essential inputs for these models. Optimizing these parameters is critical for enhancing gas transport and minimizing polarization losses [20].

Comprehensive modelling of SOFCs often involves computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and multiphysics approaches to simulate the coupled phenomena of mass transfer, heat transfer, fluid flow, and electrochemistry. These models [21,22,23] can provide detailed spatial distributions of reactant concentrations, temperature, and current density, which are valuable for understanding cell operation and identifying performance limitations. Several studies [24,25,26,27,28] have also utilized CFD and multiphysics models to investigate various aspects of SOFCs, including different flow channel geometries, porous structures, and operating conditions. Some modelling efforts specifically focus on mass transfer within the anode, comparing different models or evaluating the impact of microstructure.

Anode-supported SOFCs are particularly relevant for the direct utilization of various fuels, including methane, syngas, and biogas, due to the catalytic activity of the anode material (typically Ni-YSZ) for internal steam or dry reforming. However, operating on hydrocarbon fuels can pose challenges, such as carbon deposition (coking) and sulphur poisoning, which can degrade the anode’s performance and lifetime [29,30,31,32]

Previous studies have compared various gas diffusion models, including Fick’s law, the Stefan–Maxwell equations, and the Dusty Gas Model, to predict mass transport in SOFC anodes [3,16,19]. Building on this foundational work, the present study extends the comparison by systematically analysing SM binary and SM ternary models under varying hydrogen concentrations and temperature conditions, while incorporating the effect of anode microstructure through effective diffusivity in different material layers. This approach provides additional insights into concentration polarization trends that can guide early-stage electrode design and operational optimization.

In this study, a comprehensive modelling framework is developed to analyse gas transport phenomena within the porous anode structures of SOFCs, with emphasis placed on the role of microstructural characteristics in governing mass transfer behaviour. Two distinct modelling approaches are employed to quantify gas composition profiles and concentration polarization: an analytical method based on binary gas diffusion, and a one-dimensional isothermal model formulated using the SM equations to account for multi-component gas interactions. These approaches are applied to representative SOFC operating conditions involving varying hydrogen-based gas mixtures and temperature regimes, and the model predictions are validated against experimental diffusion data to ensure accuracy and applicability.

This work provides a systematic comparative evaluation of established diffusion models—including FM, SM binary, and SM ternary models—under realistic anode operating conditions. By offering clear parametric insights into the influence of fuel composition, temperature, and microstructural properties on concentration polarization, this study contributes practical guidance for optimizing SOFC anode design and operating strategies. The strength of this work lies in its ability to deliver these insights in a form that serves as a preliminary design guide for researchers and engineers before progressing to more detailed or resource-intensive simulations. The findings serve as a valuable foundation for future developments and more advanced multi-dimensional modelling of SOFC systems.

2. Theory and Methodology

In this study, a structured methodology was adopted, beginning with a comprehensive literature review to establish the theoretical foundation for gas transport in SOFC anodes. Analytical models were formulated and validated using experimental gas diffusion data, followed by the development of an advanced Excel-based computational tool to enable detailed parametric analysis. A systematic comparison between modelling approaches was conducted by varying key input parameters under different operational conditions to evaluate their predictive performance. This methodological process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the method used in this research.

2.1. Modelling Equations

In this study, a one-dimensional (in the x-direction) isothermal diffusion model is used, and convective mass transport (pressure-driven flow) within the porous anode is neglected. This assumption is justified based on the typical operating conditions of anode-supported SOFCs, where gas-phase diffusion dominates mass transport due to the small pore sizes and limited pressure gradients across the electrode. While this approach captures the primary concentration polarization effects, it does not account for potential shear flow, flow maldistribution, or convective enhancement, which may be relevant in more complex geometries or under transient conditions. This simplification is acknowledged as a limitation of the current model, and future work may incorporate two-dimensional or three-dimensional CFD models to capture convective and flow distribution effects more accurately. However, this simplified framework offers a fast and effective method for establishing the influence of gas-phase mass transport on anode (and anode support) performance, making it a useful tool for guiding early-stage design and operational decisions before adopting more advanced modelling techniques.

In Fick’s Model (FM), it has been shown [19] that, for a binary component system, the formula to calculate the mole fractions y1 and y2 in a porous anode support is given by the following equation:

and y2 can be determined by the fact that y1 + y2 = 1.

The term represents the effective diffusion coefficient for a binary system, and it is given by the following formula:

For ternary component systems (H2(1)-H2O(2)-N2), the formula to calculate y1 and y2 is given by

is the overall effective diffusion coefficient for the ternary component system, and it is given by the following formula:

where represents the effective binary diffusion coefficient of component 1 in nitrogen, and yN2 is the mole fraction of nitrogen in the gas mixture. The term in Equations (2) and (4) corresponds to the effective Knudsen diffusion coefficient. Knudsen diffusion becomes significant when the mean free path of gas molecules is much larger than the characteristic pore size. However, in this study, the pore size of the porous anode supports used is sufficiently large relative to the mean free path, so Knudsen diffusion is neglected.

The SM model is an alternative, well-established framework for describing multi-component gas transport in porous media. When Knudsen diffusion is negligible, the SM equations simplify considerably. Under such conditions, analytical solutions for binary and ternary gas systems can be derived [19], making it possible to calculate species fluxes and concentration profiles based solely on binary diffusion coefficients and mole fractions.

For a binary component system in an SM model, the formula to calculate the mole fractions y1 and y2 in a porous anode support is given by the following equation:

For a ternary component system, the corresponding analytical equation is given by

Concentration polarization or overpotential is used to validate the performance of the two mass transport models. It is the difference between the ideal and real cell voltage (when corrected for Ohmic and activation overpotentials). For FM, it has been shown [19] that, for binary and ternary component systems, the respective formulae to calculate concentration polarization at x = la are as follows:

where and are the overall effective diffusion coefficients for binary and ternary components, respectively, as defined by Equations (2) and (4).

In SM models, the concentration polarization, when only the SM diffusion is considered, can be determined by the following formulae [19] for binary (Equation (9)) and ternary (Equation (10)) component systems:

The symbols and parameters used in mathematical formulations are summarised in Table 1 for clarity and reference throughout the study.

Table 1.

Definitions of symbols and parameters used in mathematical models.

The data listed in Table 2 were used to calculate the mole fraction profiles of H2, H2O, and N2 and the concentration polarization, for the case of 60% H2 content in the ternary mixture, with the anode support thickness ranging from 0 to 2 mm, evaluated in increments of 0.2 mm.

Table 2.

Input parameters for the ternary component system H2 (60%), N2 (10%), and H2O (30%).

The diffusion coefficients used in this study were derived from experimental data from diffusion measurements conducted by the authors and theoretical models. These values were adjusted using the Bruggeman correction factor [3,4], which accounts for the influence of microstructural properties such as porosity and tortuosity on effective diffusion in porous media. The effective values were then used as input parameters in the FM and SM models.

The data listed in Table 3 were used to calculate the mole fractions of H2, H2O, and N2 and the concentration polarization, for the case of 50% H2 content in the ternary mixture.

Table 3.

Input parameters for partial pressure at H2 (50%) N2 (20%), and H2O (30%).

The present model is based on several assumptions. It adopts a one-dimensional, steady-state, isothermal framework, focusing solely on diffusion-driven mass transport while neglecting convective effects, electrochemical kinetics, and local temperature gradients. Microstructural properties of the porous ceramic anode support are incorporated through effective diffusion coefficients without explicitly resolving pore geometry. Model validation was performed by comparing the model outputs with published experimental data in the literature, providing qualitative agreement but limited quantitative validation. These simplifications are acknowledged as limitations, and the model is intended primarily for comparative analysis and parametric evaluation rather than detailed predictive accuracy.

2.2. Calculation for Ternary Component System

The diffusion of gas species within two different anode supports was investigated using the FM and SM models for ternary mixtures composed of H2, H2O, and N2. Two gas compositions were studied in detail: one with 60% H2, 30% H2O, and 10% N2; and another with 50% H2, 30% H2O, and 20% N2. The SM model was used for the prediction of gas concentration profiles across the anode supports. Both FM and SM models were employed to calculate the concentration polarizations, allowing for a direct comparison of their predictions and providing insight into how each model treats diffusion in ternary gas systems. This comparative analysis helped evaluate the limitations and applicability of FM relative to the more rigorous SM formulation under the same operating conditions.

Using parameters from Table 2 and Table 3, the model discretized the anode support thickness into incremental layers. At each step, the SM equations were solved iteratively using the previously computed concentrations, the diffusion coefficients, and the imposed fluxes. This yielded the evolving concentration profiles of H2, H2O, and N2 from the gas channel to the electrode–electrolyte interface for both gas mixtures.

The model outputs include spatial profiles of the gas concentrations across the anode supports and offer insight into diffusion-limited concentration polarization under different operating scenarios. The models assume isothermal conditions and neglect coupled heat and mass transfer effects. These simplifications are justified for low-to-moderate current densities, where thermal gradients are minimal and concentration losses dominate. It has been shown that, under such conditions, neglecting thermal effects introduces only a small error (typically 5–10%) in the predicted concentration fields. However, at higher current densities or in thicker anode supports, thermal coupling may become significant and should be included in future model refinements.

It should be noted that while gas-phase concentration profiles are calculated across both of the support layers (CSZ or MMA), electrochemical reactions are assumed to occur exclusively within the functional layer. The support layer functions solely as a porous medium for gas transport, without participating in electrochemical activity. This modelling approach captures the full concentration gradient across the anode while accurately reflecting the localized nature of the electrochemical reaction zone.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mole Fraction Profiles

In this study, a quantitative model was developed to analyse the concentration (partial pressure) profiles of reactant and product species across the thickness of SOFC anode supports. The objective was to gain deeper insight into the mass transport limitations that contribute to concentration overpotentials within the porous electrode microstructure.

An isothermal assumption was adopted, and the temperature was treated as a uniform parameter across the anode. Local heating effects, including Joule heating, activation losses, and enthalpy of mixing, were not considered in the present model. Therefore, temperature gradients within the anode were neglected, and the concentration profiles and overpotentials were evaluated based on average operating temperatures. This approach allows the model to focus solely on diffusion-driven concentration variations while providing parametric insights into the impact of temperature on concentration polarization.

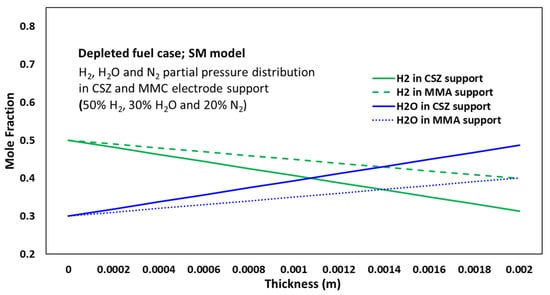

Two gas mixtures representative of typical SOFC operating conditions were considered in the model: a 20% H2 + 60% H2O + 20% N2 mixture, and a 50% H2 + 30% H2O + 20% N2 mixture. The anode support materials were CSZ and MMA, with a thickness of 2 mm for both ceramic materials.

Key input parameters, such as operating temperature, pressure, gas diffusivities in each layer, layer thicknesses, and current density, were defined based on standard SOFC anode configurations.

For the 20% H2 mixture, the hydrogen concentration decreased linearly within both the CSZ and MMA support layers. This reduction was attributed to the consumption of hydrogen as it diffused toward the reaction zone, where electrochemical oxidation occurred.

Correspondingly, the water vapour concentration increased from 0.6 at the inlet to 0.787 at the interface, reflecting the generation of H2O as a reaction product. As expected, the concentration of the inert nitrogen remained constant at 0.2 throughout the electrode’s thickness.

A less steep concentration gradient was exhibited in the MMA support compared to the CSZ support, which was attributed to the higher effective gas diffusivity of CSZ, associated with its more porous ceramic matrix structure.

The linear decrease in H2 and increase in H2O mole fractions (Figure 2) confirm diffusion limitations under fuel depletion (20% H2). The shallower gradient in MMA (−0.087 change in yH2 vs. −0.187 in CSZ) underscores its superior diffusivity. This directly correlates with reduced concentration polarization in MMA (Section 3.2), highlighting the impact of microstructure on mass transport. The decline in the H2 mole fraction from 0.5 (bulk) to 0.313 (interface) directly determines the concentration overpotential via Equation (4), with larger gradients yielding higher .

Figure 2.

Mole fraction profiles of H2 and H2O across the full anode thickness (2 mm), including the MMA functional layer (0.2 mm) and CSZ support layer (1.8 mm), under depleted fuel conditions (20% H2, 60% H2O, 20% N2), predicted by the Stefan–Maxwell (SM) model.

Similar trends were observed under the 50% H2 condition; however, the magnitude of the concentration gradients was reduced due to the higher inlet hydrogen concentration. The H2 mole fraction decreased from 0.5 at the gas channel to 0.313 at the electrode–electrolyte interface. The concentration profiles of H2O and N2 followed patterns like those in the 20% H2 case.

The model demonstrated the capability to quantitatively predict the distribution of gas species within the distinct anode layers under varying operating conditions. These results provide important insights into diffusion limitations contributing to concentration overpotentials in solid oxide fuel cells.

The analysis revealed that steeper concentration gradients occurred at lower hydrogen concentrations (e.g., 20% H2) and with increasing electrode thickness, as evidenced by the mole fraction profiles in Figure 2 and Figure 3. For instance, in the 2 mm electrode, the H2 mole fraction decreased from 0.2 at the gas channel to 0.0133 at the electrode–electrolyte interface under 20% H2 conditions, representing an 86.7% drop. In contrast, for the 0.5 mm electrode, the drop was only 53.3% (from 0.2 to 0.0933). This indicates that increasing the electrode thickness amplifies the concentration polarization, particularly under fuel-depleted conditions. These trends directly contribute to higher concentration overpotentials and reduced fuel cell performance.

Figure 3.

Mole fraction profiles of H2 and H2O across the full anode thickness (2 mm), including the MMA functional layer (0.2 mm) and CSZ support layer (1.8 mm), under normal fuel conditions (50% H2, 30% H2O, 20% N2), predicted by the Stefan–Maxwell (SM) model.

Potential mitigation strategies include reducing the electrode support thickness, without compromising structural integrity, and increasing fuel flow rates to replenish surface concentrations more effectively.

The model may also be extended to optimize key electrode parameters—such as porosity, tortuosity, and particle size—to maximize diffusivity. Additionally, the effects of temperature, pressure, and current density can be evaluated using this approach. This framework offers a robust platform for the systematic development of improved electrode materials and geometries aimed at minimizing concentration polarization.

Furthermore, the model can be integrated with CFD simulations to analyse the influence of flow channel design and to capture two-dimensional concentration distributions at the electrode scale. Such an approach would enable comprehensive optimization of the full SOFC stack configuration.

In summary, the quantitative modelling approach presented here provides critical insights into mass transport phenomena within SOFC electrodes and bridges the gap between nanoscale electrochemical kinetics and macroscale cell performance. These findings offer valuable guidance for the design of next-generation SOFCs with enhanced durability, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness.

3.2. Concentration Polarization Predictions Using the Stefan–Maxwell Model

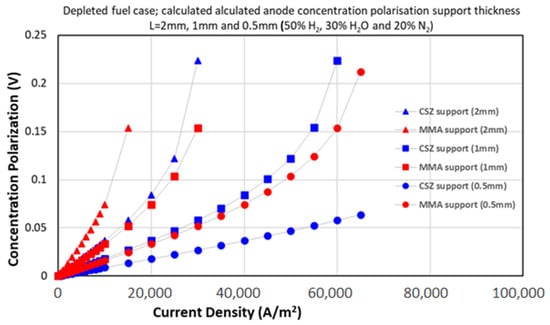

The study employed an SM binary mass transport model to predict concentration polarizations across SOFC anodes with thicknesses of 2 mm, 1 mm, and 0.5 mm.

The exponential rise in polarization with current density (Figure 4) stems from intensified hydrogen depletion (→0), as formalized in Equation (4). For the 20% H2 gas mixture, concentration profiles across the anode were evaluated using the SM model. At a current density of 10,000 A/m2 and an anode thickness of 2 mm, the hydrogen mole fraction decreased from 20% at the gas channel interface to 9.99% at the electrode–electrolyte interface. As expected, the H2O mole fraction increased along the thickness, rising from 60% to 70.1%. Similar trends were observed for 1 mm and 0.5 mm electrodes, with more rapid hydrogen depletion and steeper concentration gradients due to the reduced diffusion length.

Figure 4.

Concentration polarization (overpotential) versus current density for the 20% H2 (depleted fuel) case, using the Stefan–Maxwell binary model. The plot illustrates the increase in polarization losses under low-hydrogen conditions.

The model predicted significant concentration variations, indicating the presence of diffusion limitations at high current densities, particularly in thicker electrodes. The sharp decline in H2 concentration observed in the 2 mm case highlighted the extent of concentration polarization under these conditions. These findings quantify the severity of mass transport losses across varying operating parameters.

For the 50% H2 gas mixture at the same current density and 2 mm thickness, the hydrogen concentration decreased from 50% to 40.8%, while the water vapour content increased from 30% to 39.2%. As with the 20% H2 case, steeper gradients were observed in the 1 mm and 0.5 mm electrodes. However, the higher hydrogen content resulted in less pronounced concentration polarization and a slower depletion rate.

This approach effectively captured the influence of bulk hydrogen concentration on diffusion-related losses. Compared to the 20% H2 case, the 50% H2 mixture exhibited improved mass transport characteristics and lower concentration overpotentials.

In summary, the SM model results demonstrated that gas composition, electrode thickness, and current density exert a significant influence on concentration polarization. These insights provide valuable guidance for optimizing anode design and operating conditions to minimize diffusion limitations and enhance SOFC performance.

For the 50% H2 case, similar trends were observed, although the gradients were smaller due to the higher hydrogen concentration; H2 decreased from 0.5 to 0.313 at the interface. The analysis confirmed that concentration variations are more pronounced at lower H2 levels and higher current densities, offering guidance for optimizing electrode design and operating conditions.

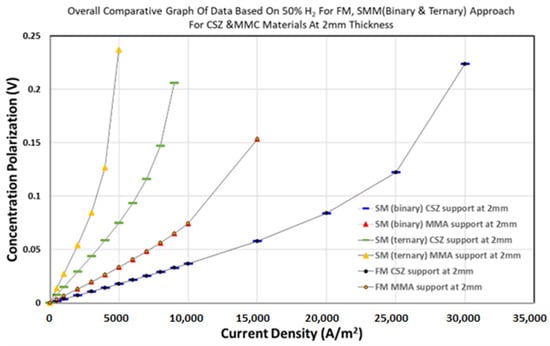

As shown in Figure 5, the concentration polarization values for the 50% H2 gas mixture were predicted using the SM ternary model. The SM ternary model consistently outperforms others, predicting 15–20% lower overpotentials than FM at 20% H2 (Figure 6). This arises from its rigorous treatment of multi-component interactions (e.g., H2-H2O-N2), critical under fuel depletion. MMA further reduces losses by 30–40% versus CSZ due to its higher porosity (Table 4), demonstrating its value for low-H2 operations.

Figure 5.

Concentration polarization (overpotential) versus current density for the 50% H2 (depleted fuel) case, using the Stefan–Maxwell ternary model. The results show the effects of multi-component interactions on polarization under low hydrogen concentrations.

Figure 6.

The concentration overpotential values for the 50% H2 gas mixture using Fick’s Model (FM) and the Stefan–Maxwell (SM) model in both binary and ternary forms.

Table 4.

Model input parameters for multi-component diffusion analysis in CSZ and MMA anode layers.

The concentration overpotential values for a 50% H2 gas mixture are compared in this graph using FM, the SM binary model, and the SM ternary model. The mole fraction profiles in Figure 2 and Figure 3 span the entire anode thickness of 2 mm, with the MMA functional layer (0.2 mm) positioned adjacent to the electrolyte and the CSZ support layer (1.8 mm) forming the bulk of the anode structure.

The anode is modelled as a bilayer structure, where the MMA functional layer is placed on top of the CSZ support layer, forming a continuous diffusion path from the gas channel to the electrolyte interface. This bilayer configuration reflects typical SOFC anode architectures, with the MMA layer enabling improved gas transport and reduced polarization losses.

In all models, overpotential increases with current density due to greater reactant consumption. The MMA functional layer (with 0.2 mm thickness) exhibited lower concentration polarization compared to the CSZ support layer (with 1.8 mm thickness), which can be attributed to its higher gas diffusivity despite the longer transport path in the CSZ layer.

Table 4 summarizes the input parameters for diffusion analysis in CSZ and MMA layers. The layer properties, including thickness, porosity, tortuosity, and effective diffusivity, were derived from experimental and theoretical studies in the literature [3,4,19]. The diffusion coefficients were calculated using the Bruggeman correction to account for the effects of porosity and tortuosity on gas transport in porous media. These values represent typical SOFC anode structures and are used to enable a realistic comparison between the CSZ support layer and MMA functional layer.

A comparative analysis of the models shows that the SM ternary model consistently predicts the lowest concentration overpotentials across both electrode materials, particularly at higher current densities and under lower hydrogen concentration (depletion) conditions. This is because the ternary model accurately captures the complex multi-component interactions that occur within the gas mixture.

The SM binary model improves upon FM by including some species interactions but still simplifies the system by only considering pairwise diffusion, which leads to slight deviations when the gas mixtures are not dominated by one species. FM significantly overestimates concentration losses due to its assumption of ideal binary diffusion, which becomes increasingly inaccurate as reactant depletion intensifies.

Overall, the SM ternary model provides the most accurate and reliable prediction of concentration polarization, especially under demanding operating conditions with high current densities and complex gas mixtures. This finding highlights the importance of using comprehensive diffusion models for precise SOFC performance assessment.

A direct comparison of the FM, SM binary, and SM ternary models was conducted using the concentration overpotential predictions shown in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 4 illustrates the overpotential trends for the 20% H2 case. The SM ternary model shows the lowest overpotential values and the best agreement with experimental data [19], particularly at higher current densities. The SM binary model overestimates polarization losses slightly, while the FM shows the largest deviation, especially under steep concentration gradients.

Figure 5 presents the results for the 50% H2 case, where the differences between the models are smaller. However, the SM ternary model still provides the most consistent predictions, showing better alignment with expected trends and lower sensitivity to hydrogen depletion.

Figure 6 compares the two fuel conditions across all models, highlighting the following:

- The SM ternary model better captures the non-linear effects of hydrogen concentration on polarization.

- FM tends to underestimate or overestimate polarization, depending on the operating point.

- The SM binary model performs well under high-H2 conditions but becomes less accurate as the H2 concentration decreases.

These results indicate that the SM ternary model is the most reliable for predicting mass transport behaviour in SOFC anodes, particularly under fuel-depleted conditions where multi-component interactions are more significant. Table 5 summarizes the outcomes of the model performance based on Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6.

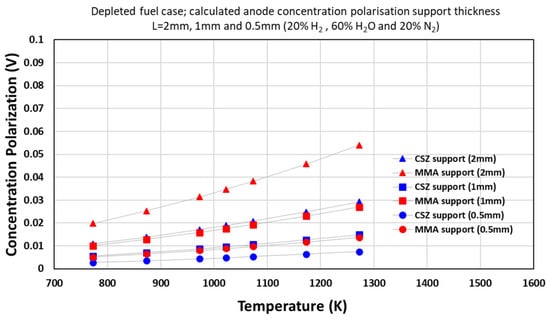

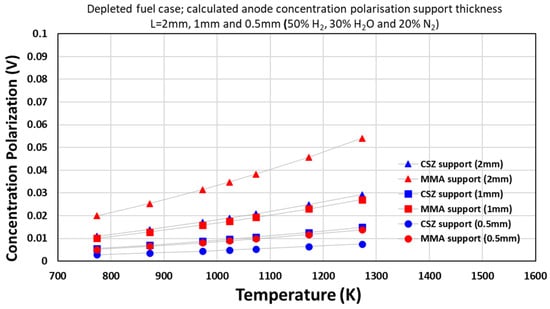

3.3. Concentration Polarization with Temperature Variation

3.3.1. Stefan–Maxwell Binary Model with Temperature Variation

The objective was to apply the SM equation for binary mixtures to analyse the effect of temperature on concentration overpotential in a 2 mm thick SOFC anode. The anode consisted of a ceramic calcia-stabilized zirconia (CSZ) support layer and a magnesia magnesium aluminate (MMA) functional layer.

Two fuel compositions were considered: 20% H2, 60% H2O, 20% N2 (steam-rich) and 50% H2, 30% H2O, 20% N2 (steam-lean). Relevant input parameters, including diffusivity and current density, were defined.

The SM model was analytically solved to determine concentration overpotentials in the CSZ and MMA layers over a temperature range of 500 °C to 1000 °C.

Figure 7 illustrates the concentration polarization variation with temperature for the depleted case (20% H2) using the SM binary model, showing the increase in polarization with temperature. For the 20% H2 case at a current density of 2000 A/m2, the concentration overpotential in the CSZ layer increased from 0.00423 V at 500 °C to 0.00717 V at 1000 °C over a 2 mm thickness. In the MMA layer, due to higher gas diffusivity, the overpotential rose from 0.00803 V to 0.014 V over the same temperature range.

Figure 7.

Concentration polarization vs. temperature for SM binary model with temperature variation (depleted case).

For a 1 mm electrode, the overpotentials were approximately halved, ranging from 0.00208 V in CSZ to 0.00403 V in MMA at 500 °C. At 0.5 mm thickness, the values further decreased, ranging between 0.00103 V and 0.00520 V.

For the 50% H2 case, lower overpotentials were observed due to the higher reactant concentration. In the CSZ layer, the overpotential increased from 0.00261 V at 500 °C to 0.00708 V at 1000 °C for a 2 mm electrode. The MMA layer again exhibited lower values, ranging from 0.00478 V to 0.0130 V over the same temperature range.

Similar trends were observed for 1 mm and 0.5 mm thicknesses, with MMA consistently showing lower overpotentials than CSZ across all temperatures.

The results indicate that temperature has a direct effect on concentration overpotential, with losses increasing at higher temperatures due to accelerated electrochemical reaction rates. This effect is more pronounced under low-hydrogen concentrations.

The model offers valuable insights into mass transport limitations under both steam-rich and steam-lean conditions, supporting informed decisions on electrode thickness and operating temperature to minimize concentration losses.

Figure 8 presents the concentration polarization variation with temperature for the normal case (50% H2), demonstrating the lower overpotentials compared to the depleted case, especially with increasing temperature.

Figure 8.

Concentration polarization vs. temperature for SM binary model with temperature variation (normal case).

3.3.2. Stefan–Maxwell Ternary Model with Temperature Variation

The SM equation for ternary mixtures was applied to analyse the effect of temperature on concentration overpotential in a 2 mm thick SOFC anode. The anode consisted of a CSZ support and MMA functional layers.

Two fuel gas compositions were considered: 20% H2, 60% H2O, 20% N2 (steam-rich) and 50% H2, 30% H2O, 20% N2 (steam-lean). Relevant parameters, including diffusivity and current density, were specified.

For the 20% H2 case, the overpotential in CSZ increased from 0.0160 V at 500 °C to 0.0493 V at 1000 °C. In the MMA layer, the overpotential rose from 0.0353 V to 0.200 V due to higher gas diffusivity. Higher temperatures amplified by accelerating H2 consumption (reducing ), as per Equation (4).

With a 1 mm electrode, the overpotentials decreased by nearly half in both layers, ranging from 0.00746 V in CSZ to 0.0147 V in MMA at 500 °C. At 0.5 mm thickness, the values further reduced, ranging from 0.00362 V to 0.00687 V.

Overpotential increased with temperature (Figure 9) due to accelerated reaction rates depleting H2 faster. At 1000 °C, the losses in MMA were 60% lower than in CSZ for 20% H2. This underscores the need for material-aware thermal management: MMA’s stability enables high-temperature operation with minimized polarization.

Figure 9.

Concentration polarization vs. temperature SM ternary model with temperature variation (depleted case).

As shown in Figure 10, for the 50% H2 case, lower overpotentials were observed due to the higher reactant concentration. In the CSZ layer, the overpotential increased from 0.0109 V at 500 °C to 0.0292 V at 1000 °C for a 2 mm electrode. The MMA layer again showed lower values, rising from 0.0199 V to 0.0540 V.

Figure 10.

Concentration polarization vs. temperature SM ternary model with temperature variation (normal case).

Similar trends were observed for 1 mm and 0.5 mm thicknesses, with MMA consistently exhibiting lower overpotentials than CSZ across the temperature range.

The results confirm that temperature directly influences concentration overpotential, with losses increasing at higher temperatures due to accelerated electrochemical reaction rates. This effect is more pronounced under lower-hydrogen concentrations.

The model offers clear insight into mass transport limitations under both steam-rich and steam-lean conditions, supporting informed selection of electrode thickness and operating temperature to minimize concentration losses.

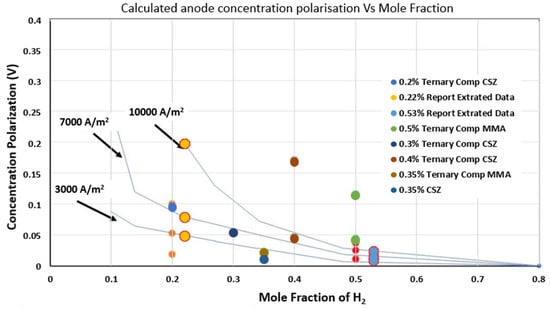

3.4. Validating SM Models

Model validation focused on gas-phase concentration polarization using data from Suwanwarangkul et al. [19]. Predictions for 20% H2 at 10,000 A/m2 show deviations within 8% (Figure 11). The ternary SM model aligns closest with experiments (average error: 5.2%), while Fick’s Model overestimates losses by 15–25% due to neglecting multi-component interactions. This confirms the SM framework’s reliability for SOFC mass transport analysis under practical operating conditions.

Figure 11.

Comparison of model predictions using Fick’s Model (FM) and the Stefan–Maxwell (SM) model with experimental data for concentration polarization (overpotential) as a function of hydrogen mole fraction. The experimental data, sourced from Suwanwarangkul et al. [19], represent measured overpotential values from SOFC studies under controlled gas compositions and current densities. These data are used to validate the model predictions for both fuel-depleted (20% H2) and normal (50% H2) operating conditions. The plot illustrates a good agreement between the SM model predictions and the experimental measurements, particularly under low-hydrogen-concentration conditions, supporting the model’s accuracy in capturing concentration polarization effects in SOFC anodes.

The evaluation focused on concentration polarization in SOFC anodes for two hydrogen (H2) mole fractions—0.2 and 0.5—representing steam-rich and steam-lean conditions. It is important to note that the present model focuses solely on gas-phase mass transport within the anode and does not simulate the full electrochemical performance of the SOFC, such as voltage–current (V-I) characteristics or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) responses. Consequently, direct validation using full-cell experimental data is beyond the scope of this study. Instead, the model predictions of concentration polarization were compared against published experimental data on gas-phase diffusion and concentration overpotentials, providing reasonable agreement within the intended modelling framework. Previous studies have reported comparisons between measured and calculated concentration overpotentials in H2–H2O–Ar systems at current densities of 3000, 7000, and 10,000 A/m2 [16,19]. These experimental data were obtained from the work of Suwanwarangkul et al. [19], where detailed polarization measurements under controlled gas compositions were used to validate diffusion models.

In this work, concentration overpotentials were analysed in the ceramic CSZ support layer and metallic MMA functional layer. SM binary and ternary diffusion models were applied at current densities of 3000, 7000, and 10,000 A/m2.

At 0.2 H2, the binary model predicts overpotentials of 0.0183 V in CSZ and 0.0106 V in MMA at 3000 A/m2, increasing to 0.0527 V and 0.0252 V at 7000 A/m2, respectively. The ternary model yields slightly higher values.

At 0.5 H2, the binary model estimates overpotentials of 0.0378 V in CSZ and 0.0196 V in MMA at 3000 A/m2, while the ternary model predicts negligible losses.

In general, higher overpotential values are observed for 0.2 H2 compared to 0.5 H2, as expected, due to steeper concentration gradients at lower reactant levels. The MMA layer consistently exhibits lower overpotentials than the CSZ layer, attributed to its higher gas diffusivity resulting from increased porosity. Overpotentials increase with current density due to greater reactant consumption.

The accuracy of the gas distribution calculated using the SM model was assessed by comparing the predicted concentration overpotentials with experimental data from the literature. The model showed good agreement, with deviations typically within 5–10% of the reported experimental values across various hydrogen concentrations and current densities. While uncertainty bands were not included in the current graphs, the results indicate that the model reliably captures the key trends in concentration polarization. Incorporating uncertainty quantification in graphical outputs could be considered in future work to further enhance model interpretation.

The model offers valuable insights into mass transport limitations under varying operating conditions, supporting the optimization of electrode materials and microstructure to minimize concentration losses.

The model presented in this study focuses specifically on gas-phase diffusion processes within the porous anode structure; therefore, it is not designed to predict or simulate full electrochemical performance metrics such as voltage–current (V-I) characteristics or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data. These metrics involve complex interactions among charge transport, reaction kinetics, and interfacial phenomena, which are beyond the scope of the current work. Instead, the model was validated using experimental diffusion data from the literature [19], focusing on concentration polarization under varying hydrogen concentrations (20% and 50%) and current densities. The predicted concentration overpotentials show good agreement with experimental measurements, with deviations within 5–10%, confirming the model’s reliability for predicting mass transport limitations in SOFC anodes. Future extensions of this work may include coupling the diffusion model with electrochemical reaction models and ionic transport equations to enable comparison with V-I and EIS data, and to provide a more comprehensive performance analysis.

4. Conclusions

This study presented a one-dimensional, isothermal, multi-component diffusion model based on the Stefan–Maxwell (SM) formulation to analyse mass transport and concentration polarization in anode-supported solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs). The model was applied to two representative fuel mixtures (20% H2 and 50% H2) across a temperature range of 500–1000 °C and varying electrode thicknesses.

The results demonstrated that the ternary SM model provides the best agreement with published experimental data on concentration overpotential, particularly under low-hydrogen conditions (20% H2), where multi-component interactions significantly affect mass transport behaviour.

It was found that concentration overpotential increases with temperature and current density, with the most pronounced effects observed under fuel-depleted conditions. The magnesia magnesium aluminate (MMA) functional layer consistently exhibited lower polarization losses compared to the calcia-stabilized zirconia (CSZ) support, attributed to its higher gas diffusivity due to increased porosity.

These findings provide a reliable modelling framework for evaluating mass transport limitations in SOFCs and offer actionable insights for optimizing electrode design and operating conditions. This study supports the use of advanced diffusion models like the SM approach for more accurate predictions of concentration polarization, particularly in low-fuel or high-current applications.

While the model showed good agreement with experimental data (deviations within 5–10%), future work should incorporate multi-dimensional effects, real-time operational conditions, and coupled thermal and electrochemical phenomena to enhance predictive accuracy and applicability.

In this study, we introduced a robust, analytically solvable SM ternary model for multi-component gas transport in SOFC anodes. By comparing it with FM and SM binary models across different fuel compositions, temperatures, and material architectures (CSZ vs. MMA), this study demonstrates the superiority of the SM ternary approach in capturing complex species interactions and reducing predictive errors. The model’s high fidelity, validated against experimental data, combined with its low computational cost, makes it a valuable design tool for the early-stage optimization of SOFCs. These insights can inform material selection and operating strategies, thereby reducing reliance on computationally intensive CFD simulations and accelerating the development of high-performance SOFC systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K. and M.C.; Methodology, C.K. and M.C.; Software, V.K.P., F.G. and M.C.; Validation, M.C.; Formal analysis, V.K.P. and M.C.; Investigation, F.G. and M.C.; Data curation, V.K.P.; Writing—original draft, C.K.; Writing—review & editing, F.G., M.G. and M.C.; Visualization, M.G.; Supervision, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Díaz, B.; Celentano, D.; Molina, P.; Sancy, M.; Troncoso, L.; Walczak, M. On the validation and applicability of multiphysics models for hydrogen SOFC. J. Power Sources 2024, 607, 234493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Lau, G.; Song, D.; Fukuyama, Y.; Tucker, M.C. Optimization of metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells with a focus on mass transport. J. Power Sources 2023, 555, 232402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zheng, K.; Yan, Y.; Liu, W.; Bai, P.; Wang, S.; Xu, L. Optimizing fuel transport and distribution in gradient channel anode of solid oxide fuel cell. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 285, 119558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machaj, K.; Kupecki, J.; Niemczyk, A.; Malecha, Z.; Brouwer, J.; Porwisiak, D. Numerical analysis of the relation between the porosity of the fuel electrode support and functional layer, and performance of solid oxide fuel cells using computational fluid dynamics. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 936–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.H.; Sezer, H.; Celik, I.B.; Epting, W.K.; Abernathy, H.W.; Kalapos, T. Fundamental study of gas species transport in the oxygen electrode of solid oxide fuel and electrolysis cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 1142–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Pan, Y.; He, F.; Xu, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, B.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M. Manipulating and optimizing the hierarchically porous electrode structures for rapid mass transport in solid oxide cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheem, H.H.; Abbas, S.Z.; Tabish, A.N.; Fan, L.; Maqbool, F. A review on mathematical modelling of direct internal reforming-solid oxide fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2022, 520, 230857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, I.K.; Gizzatullin, A.R.; Filimonova, A.A.; Chichirova, N.D.; Beloev, I.H. Numerical simulation of processes in an electrochemical cell using COMSOL Multiphysics. Energies 2023, 16, 7265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, A.R.; Wilhelm, C.A.; Welles, T.S.; Milcarek, R.J.; Ahn, J. Effects of Synthesis Gas Concentration, Composition, and Operational Time on Tubular Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Liang, K.; Ma, G.; Ba, L. Three-dimensional multi-physics modelling and structural optimization of SOFC large-scale stack and stack tower. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 2742–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, F.R.; Yuan, H.-B.; Moran, J.C.; Tippayawong, N. Overview of hydrogen production technologies for fuel cell utilization. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2023, 43, 101452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, A.; Chakrovorty, A.; Sarmah, P.; Paramasivam, P.; Kumar, V.; Yadav, S.K.; Manickkam, S.; Ahmed, M. A review on solid oxide fuel cell technology: An efficient energy conversion system. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 6443247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opakhai, S.; Kuterbekov, K. Metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells: A review of recent developments and problems. Energies 2023, 16, 4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, H.; Babaei, M.; Theodoropoulos, C. Multiscale Simulation of Internal Reforming Solid Oxide Fuel Cells to Capture Complex Reaction Phenomena. ECS Meet. Abstr. 2024, MA2024-02, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.T.; Claassen, C.M.Y.; Baltussen, M.W.; Peters, E.; Kuipers, J.A.M. Coupling of multicomponent transport models in particle-resolved fluid-solid simulations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 291, 119920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedik, A.; Lubos, N.; Kabelac, S. Coupled transport effects in solid oxide fuel cell modeling. Entropy 2022, 24, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błesznowski, M.; Sikora, M.; Kupecki, J.; Makowski, Ł.; Orciuch, W. Mathematical approaches to modelling the mass transfer process in solid oxide fuel cell anode. Energy 2022, 239, 121878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.A.; Bao, C.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X. A combined approach of Lattice Boltzmann Method and Maxwell-Stefan equation for modeling multi-component diffusion in solid oxide fuel cell. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1809.01600. [Google Scholar]

- Suwanwarangkul, R.; Croiset, E.; Fowler, M.W.; Douglas, P.L.; Entchev, E.; Douglas, M.A. Performance comparison of Fick’s, dusty-gas and Stefan–Maxwell models to predict the concentration overpotential of a SOFC anode. J. Power Sources 2003, 122, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.R.; Padinjarethil, A.K.; Hagen, A.; Bosio, B. Multiscale analysis of Ni-YSZ and Ni-CGO anode based SOFC degradation: From local microstructural variation to cell electrochemical performance. Electrochimica Acta 2023, 460, 142589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhu, P.; Huang, Y.; Yao, J.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, M. A Comprehensive Review of Modeling of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: From Large Systems to Fine Electrodes. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 2184–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, E.; Dehghani, H.; El Hachemi, M.; Belouettar–Mathis, E.; Makradi, A.; Wallmersperger, T.; Gouttebroze, S.; Preisig, H.; Andersen, C.W.; Shao, Q.; et al. Physics-based and data-driven modelling and simulation of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 96, 962–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, C.; Liu, M.; Fan, J.; Yan, J. Transient performance analysis of a solid oxide fuel cell during power regulations with different control strategies based on a 3D dynamic model. Renew. Energy 2023, 218, 119266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzhi, L.U.; Wei, S.; Zhenhua, D.U.; Wanda, M.A.; Shidong, N.I. Analysis and comparison of multi-physics fields for different flow field configurations in SOFC. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 229, 125708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tian, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Jia, L.; Li, J.; Yan, D. Numerical and experimental study of effects of different flow channel structures on the performance of solid oxide fuel cell. J. Power Sources 2025, 652, 237401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lu, L.; Levtsev, A.; Chen, D. Investigate the multi-physics performance of a new fuel cell stack by a 3D large-scale model basing on realistic structures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 7085–7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, W.; Kuang, X.; Jia, L.; Yan, D. Numerical optimization of obstacles channel geometry for solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 38438–38453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.; Yin, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Yun, K.; Yu, J. Impact of Fuel Utilization on Flow and Reaction Uniformity in a 1 kWe SOFC Stack: A CFD-Based Study. Fuel Cells 2025, 25, e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maza, W.A.; Steinhurst, D.; Pomeroy, E.D.; Kee, R.J.; Ricote, S.; Walker, R.A.; Owrutsky, J. Comparison of Carbon Deposition and Removal from Ni-YSZ and Ni-BCZY Composites Using Operando Optical Methods. ECS Transactions 2023, 111, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Hou, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, M. Sulfur-and Coking-Tolerant Anodes for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. ECS Meet. Abstr. 2022, MA2022-02, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainon, A.N.; Somalu, M.R.; Bahrain, A.M.K.; Muchtar, A.; Baharuddin, N.A.; Sa, M.A.; Osman, N.; Samat, A.A.; Azad, A.K.; Brandon, N.P. Challenges in using perovskite-based anode materials for solid oxide fuel cells with various fuels: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 20441–20464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, Z.; Felix, A.; Kalyvas, C.; Chizari, M. Design of a Fuel Cell/Battery Hybrid Power System for a Micro Vehicle: Sizing Design and Hydrogen Storage Evaluation. Vehicles 2023, 5, 1570–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).