Abstract

The NTRU (Number Theory Research Unit) is a prominent post-quantum public key cryptography algorithm and a current focus of research. Although many NTRU variants have been proposed, a comprehensive generalization of these variants is still lacking. To address this issue, we propose the G-NTRU (Generalized NTRU), an algorithmic framework for NTRU variants on algebraic rings. This framework generalizes specific ring extensions to more general algebraic structures, allowing the unification of various NTRU variants. We then analyze the key properties of the G-NTRU, including correctness, lattice-based characteristics, and security. The semantic security of the G-NTRU is demonstrated through the introduction of the G-AGCD (Generalized Approximate Greatest Common Divisor). To validate the generality of the G-NTRU framework, we introduce the CNTRU (Complex Number NTRU), a variant of the NTRU over the ring of complex numbers. The CNTRU shares the same properties as the G-NTRU, further confirming the versatility of the G-NTRU in studying NTRU variants over algebraic rings.

1. Introduction

With the advancement of the Internet, while fostering closer connections between people, private information has also become increasingly vulnerable to exposure. Cryptographic algorithms remain the most effective, economical, and reliable method for securing network data. The evolution of public key cryptography has progressed through traditional algorithms, which are based on hard mathematical problems. Classical public key cryptography relies on challenges such as integer factorization and the discrete logarithm problem, exemplified by the RSA encryption algorithm [1], the DSA signature algorithm [2], the ElGamal encryption algorithm [3], and the Paillier encryption algorithm [4]. However, Shor demonstrated that quantum computers can efficiently solve integer factorization and discrete logarithm problems [5], reducing these once-hard problems to tractable P-problems. As a result, researchers have shifted toward developing cryptographic algorithms resistant to quantum computing, known as quantum-resistant or post-quantum cryptography.

In 2016, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) initiated the Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization Process [6], aiming to standardize cryptographic algorithms resistant to quantum attacks. Lattice-based cryptography quickly emerged as one of the leading candidates due to its strong security foundations and versatility. By August 2024, NIST published three post-quantum cryptography (PQC) standards [6]: ML-KEM, ML-DSA, and SLH-DSA. Among these, ML-KEM (Modular Lattice Key Encapsulation Mechanism) and ML-DSA (Modular Lattice Digital Signature Algorithm) are both based on modular lattice structures, underscoring the significant role of lattice-based cryptography in the field.

A lattice is a mathematical structure consisting of discrete points generated by a set of vectors, forming a regular, structured grid. Lattice cryptosystems, a promising class of post-quantum public key cryptosystems, derive their security from the hardness of solving lattice problems. These problems, such as the Shortest Vector Problem (SVP) and the Closest Vector Problem (CVP), involve finding specific lattice points in a high-dimensional Euclidean space. The challenge lies in the rapid increase in complexity as the dimensionality rises, leading to an exponential growth in the computational effort required to solve these problems using classical algorithms. To date, no efficient algorithms have been discovered for solving these lattice problems on either classical or quantum computers, making them a strong candidate for secure post-quantum encryption schemes.

Lattice-based cryptographic schemes continue to dominate research in post-quantum cryptography, offering robust security against quantum computational threats, and are regarded as key to the future of secure communication in the quantum era. The extensive study of lattice structures for cryptographic purposes, such as NTRU and its variants, reflects the broader effort to develop practical, quantum-resistant encryption and signature algorithms.

In 1998, Hoffstein, Pipher, and Silverman proposed the NTRU (Number Theory Research Unit) public key encryption algorithm [7]. The NTRU algorithm features a simple structure and is algebraically based on polynomials, constructed over a polynomial quotient ring. It offers higher operational speed compared to traditional public key cryptographic algorithms, and its security can be reduced to the lattice problem, providing resistance against quantum computing attacks. Over time, the NTRU has been further developed, leading to the emergence of several NTRU variants. A brief chronological introduction to these variants is provided below, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

NTRU variants.

There are several other NTRU variants of the algorithm [21]. The primary distinction among the various NTRU variant algorithms lies in the different rings on which they are based. The characteristics of NTRU variants constructed over different rings differ, impacting their speed, security, and other properties. However, NTRU variant algorithms based on the same type of ring also exhibit commonalities and share similarities in their nature. In 2015, Yasuda et al. summarized and analyzed a class of NTRU variant algorithms, proposing a generalized NTRU cryptographic algorithm based on a group ring, referred to as GR-NTRU [22]. The ring associated with GR-NTRU is isomorphic to the ring of NTRU polynomial quotient rings, . Additionally, there are many NTRU variant algorithms defined over other rings, such as the ring of integers, the ring of Gaussian integers, and the ring of matrices.

This paper focuses on generalizing NTRU variant algorithms by extending them over algebraic rings to propose the G-NTRU algorithms. It aims to facilitate the study of the properties of this kind of NTRU variant through the G-NTRU algorithm framework. To enable a thorough analysis of the semantic security of the G-NTRU, the AGCD problem is extended from the ring of integers to the generalized AGCD problem over rings, referred to as the G-AGCD problem. The framework for the semantic security proof of the G-NTRU is constructed under the assumption of the G-AGCD hard problem. The innovative contributions of this research are described below:

- (1)

- A generalized NTRU algorithm over algebraic rings, referred to as the G-NTRU algorithm, is proposed to extend existing NTRU algorithms within this context. The G-NTRU framework enables a more comprehensive understanding and exploitation of the properties and performance of the NTRU algorithm across different algebraic structures, thus opening up new possibilities for the advancement of post-quantum cryptography. A comparative analysis of the G-NTRU algorithm is conducted, and its variants over different algebraic rings are comprehensively compared with other NTRU variant algorithms. This analysis aims to better assess their performance and security, providing deeper insights and directions for future research on NTRU algorithms.

- (2)

- The generalized AGCD problem over an algebraic ring, referred to as the G-AGCD problem, is presented. This extension of the traditional AGCD problem from the ring of integers to generalized algebraic rings facilitates the analysis of the semantic security of the G-NTRU. The AGCD problem can also be adapted to different rings; for example, in the context of a matrix ring, it becomes the AMGCD problem. Assuming the G-AGCD problem is difficult, the IND-CPA security of the G-NTRU is demonstrated through the combination of residual hash primitives.

- (3)

- To verify the generality of the G-NTRU algorithmic framework, a variant of the NTRU algorithm over the complex ring, referred to as the complex NTRU algorithm (CNTRU), is proposed. The CNTRU algorithm is constructed based on the G-NTRU framework, facilitating a more convenient study of its properties through the lens of the G-NTRU. The CNTRU algorithm retains the same properties as those in the G-NTRU framework, thereby validating the generality of the G-NTRU in the context of NTRU variants over algebraic rings.

Section 2 of this paper introduces the relevant theoretical concepts. Section 3 describes the algorithmic structure of the G-NTRU. Section 4 outlines the properties and security of the G-NTRU, including a comparative analysis. Section 5 details the algorithmic structure of the CNTRU. Finally, Section 6 concludes this paper.

2. Theoretical Background

This section outlines the foundational concepts utilized in this paper.

2.1. Lattice

In cryptography, lattice is a mathematical structure with significant applications. Below are some definitions of lattice:

Definition 1

(lattice). Let be a set of linearly independent row vectors. From this set of row vectors, we form a row-full rank matrix . The set is then called the lattice generated by the vectors over , denoted .

Any set of linearly independent vectors generated by can serve as a basis for the lattice. The number of vectors in the lattice basis is referred to as the dimension of the lattice.

Definition 2

(NTRU lattice). There exists a ring , where the elements of

are polynomials of degree at most

, with coefficients in the range

. These polynomials take the form

. In this ring, there exists a polynomial

and an invertible polynomial

, such that

. The NTRU lattice is determined by

and

and is defined as follows:

2.2. Gaussian Heuristic

The Gaussian distribution can be applied to lattices for studying and analyzing their properties. It is also a crucial tool for the analysis and design of public key cryptographic schemes based on lattices.

Definition 3

(Gaussian function). Let . For any -dimensional vector , let be the Gaussian function with centred and factored as a Gaussian function. For any set of dimensional vectors, the Gaussian function is .

Definition 4

(discrete Gaussian distribution on lattice). Let real . For any dimensional vector and lattice , define a discrete Gaussian distribution on lattice , where .

The geometric significance of the discrete Gaussian distribution on the lattice lies in the fact that, under the Gaussian distribution , the distance from all points on the lattice to the center point ccc is approximately .

Definition 5

(Gaussian Heuristic). For the n-dimensional lattice , the Gaussian expectation of the shortest length is as follows:

It is called the Gaussian Heuristic. Here,

represents the volume (or capacity) of the lattice

, which is also the determinant of the lattice basis matrix

. In a randomly chosen lattice

, the length (

) of the shortest nonzero vector (

) is satisfied:

If

is a constant, then an

-dimensional randomly chosen lattice satisfies, for all sufficiently large

,

2.3. GCD Problem Variants

The Greatest Common Divisor problem is a challenging issue involving integers, centered on finding the Greatest Common Divisor among them. Several other difficult problems are extensions of the GCD problem.

Definition 6

(GCD problem). For a large prime , given a set of products of , where is chosen randomly, solve for .

Definition 7

(AGCD problem). For a large prime , given a set of error products of p, where is the small-integer error, and and are chosen randomly to solve .

Definition 8

(DAGCD problem). For a large prime , given a set of error products of p and a random number , distinguish between and the random number .

Definition 9

(AMGCD problem). For an integer matrix , given a set of error matrices , det(A) = p}, find such that .

2.4. Ring

In mathematics, the term “ring” refers to an algebraic structure that includes the operations of “” and “”, satisfying specific axioms, such as the associative and distributive laws. The following is a precise definition of a ring:

Definition 10

(ring). A nonempty set defining two algebraic operations, also denoted

, is called a ring if the following is true:

- Addition “+”:

- is closed for the “+” operation, which means that for any , there is ;

- There exists a unit element “0” in R, which means that for , there exists satisfying ;

- All elements in satisfy the associative law, which means that for any , there is ;

- All elements in satisfy the commutative law, which means that for any , there is ;

- All elements in have inverse elements corresponding to them, which means that for any , there exists satisfying .

- 2.

- Multiplication “”:

- is closed for the “” operation, which means that for , there is ;

- All elements in satisfy the associative law, which means that for any , there is ;

- All elements in satisfy the distributive law, which means that for any , there are .

Definition 11

(division ring): Ring R is called a division ring if the following is true:

- There exists at least one element not equal to zero in R, and the zero element 0 satisfies ;

- There exists a unit element “1” in , which means that for , there exists satisfying and ;

- Every nonzero element has an inverse element in , which means that for any , there exists satisfying .

2.5. Verifiable Security

Semantic security refers to a property of encryption schemes that ensures the ciphertext does not reveal any meaningful information about the plaintext, even if an adversary has access to auxiliary information. In other words, the encryption should be indistinguishable from random data, making it computationally infeasible for an attacker to deduce any information about the original message.

The IND-CPA (Indistinguishability under Chosen Plaintext Attack) game is a framework used to demonstrate the security of a cryptographic algorithm against chosen plaintext attacks. In this game, an adversary is given the ability to choose plaintexts and receive corresponding ciphertexts, ultimately attempting to distinguish between two different messages encrypted under the same key.

Definition 12

(IND-CPA game). IND-CPA security is demonstrated through a game between an adversary and a challenger, divided into the following sessions:

(1) Initialization: The challenger generates a public key from the key generation algorithm of the cryptographic regime and then gives that public key to the adversary.

(2) Access to Oracle: An adversary can select a plaintext message multiple times and then access the Oracle to obtain the ciphertext encrypted by the system.

(3) Challenge: The adversary outputs plaintext messages

and

. After receiving the two plaintext messages, the challenger randomly chooses

and generates the target ciphertext

to send to the adversary.

(4) Conjectures: The adversary guesses and outputs

. If

, the adversary wins.

The adversary’s advantage in winning the game is defined as . An encryption algorithm is considered indistinguishable under a chosen plaintext attack, or IND-CPA-secure, if for any polynomial-time adversary, there exists a negligible function such that .

3. G-NTRU Algorithm

The G-NTRU algorithm is not a single algorithm but a framework for generalized NTRU variants over algebraic rings. It is not designed for a specific ring but rather for a generalized algebraic ring, denoted as . First, we introduce the structure of the ring , followed by a detailed description of the algorithmic steps.

Given a division ring , where each coefficient of is an integer, for example, can represent a ring of integer polynomials, where each coefficient of the polynomials is integer, or can represent a ring of integer matrices, where each element of the matrix is an integer.

For and , define as the operation where each integer coefficient of is taken by modulo , as the operation where each integer coefficient of is multiplied by , and as the operation where each integer coefficient of is incremented by . Clearly, after performing these operations, the resulting element remains in the ring . The element is called the inverse of modulo if it satisfies .

The following defines the NTRU algorithm over the algebraic ring , referred to as the G-NTRU algorithm.

- :

- 1.

- Inputs:

Let be the elements in the generalized ring , where has an inverse modulo (). The is generally .

Here, is chosen as a large prime number, while is an integer that is homogeneous with (), with the condition that is much larger than .

- 2.

- Calculate the inverse:

Compute the inverse of modulo , denoted as , and the inverse of modulo , denoted as . This operation ensures that

Store this inverse:

- 3.

- Calculate h:

Multiply with , and then reduce the result modulo to obtain

Ensure that all the coefficients of lie in the interval .

If any coefficient , set .

If any coefficient , set .

- 4.

- Output keys:

The public key is

The private key is

- :

- 1.

- Choose the plaintext:

Select a plaintext element with coefficients in the range .

- 2.

- Randomly select element:

Randomly select an element . The coefficients of can also be within .

- 3.

- Calculate c:

Compute the product , where is the public key obtained from the previous steps.

Ensure that the coefficients of the ciphertext are within the appropriate range .

- 4.

- Output c:

The ciphertext is then returned as the output.

- :

- 1.

- Inputs:

, : the private key.

: the ciphertext.

: a large modulus.

: a small modulus.

- 2.

- Calculate a:

Multiply the private key with the ciphertext , and then reduce the result modulo to obtain

After computing , ensure that all its coefficients are within the range .

- 3.

- Calculate b:

Multiply the private key with , and then reduce the result modulo to obtain

Reduce the result ; ensure that all its coefficients lie within the range .

- 4.

- Output b:

The value is the decrypted plaintext .

- 5.

- Encryption and decryption correctness:

By analyzing the decryption algorithm, we can evaluate the correctness of both the encryption and decryption processes.

The decryption is successful.

4. Algorithm Analysis

Section 4 primarily discusses the security of the G-NTRU algorithm and provides a comparative analysis with other algorithms. The AGCD problem and its extended versions are introduced. The generalized GCD problem over different algebraic rings, termed the G-AGCD problem, is formulated inductively. For example, over the ring of integers, G-AGCD reduces to AGCD, and over the ring of matrices, G-AGCD reduces to AMGCD. Finally, the security of G-AGCD is analyzed in the context of the G-AGCD problem.

4.1. Security Analysis

4.1.1. Lattice Attack

The lattices underlying different NTRU variant algorithms differ, but they share common characteristics. Here, we summarize the lattice structure on which these NTRU variants are based in a generalized form, referred to as the G-NTRU lattice.

Definition 13

(G-NTRU lattice). The generalized NTRU lattice is generated from the

dimensional lattice basis matrix

, which is constructed using the public key

from the generalized NTRU algorithm.

where

is the matrix generated by the public key

, and

is a parameter to be determined, typically set to 1, as discussed below.

The NTRU lattice structure varies depending on the algebraic ring it is constructed on, with differences primarily in the formation of the matrix. For example, on polynomial rings, the NTRU lattice is defined by a cyclic matrix generated from the public key coefficients , represented as follows:

In the case of matrix rings, the Matrix NTRU lattice H is generated from the matrix public key coefficients , represented as follows:

For integer rings, the lattice structure is simply the one-dimensional case of the Matrix NTRU lattice, reflecting the algebraic equivalence between congruence cryptographic algorithms and the Matrix NTRU algorithm in one dimension.

Theorem 1.

The , formed by multiplying the private key by and concatenating it with , lies on the lattice .

Proof of Theorem 1.

Given

there exists such that

Now, consider the and multiply it by the lattice basis matrix :

Expanding this product yields the following:

Thus, can be expressed in terms of the lattice basis , implying that lies on the lattice .

This completes the proof. □

may represent either a vector or a matrix; however, it will be discussed below in the context of as a vector. Assuming that is a matrix, if any of its row vectors is close to the shortest vector in the lattice, then it can be generalized that solving the matrix is equivalent to solving the Shortest Vector Problem (SVP).

According to the Gaussian Heuristic, the expected length of the shortest vector in the lattice can be expressed as follows:

Furthermore, the length of the target vector is given by the following:

Here, a good choice of the parameter can facilitate the attacker’s ability to find the vector or vectors of length close to . As the ratio increases, it becomes easier to locate the target vector. If this ratio gradually approaches 1, the difficulty of finding the target vector becomes more akin to solving the Shortest Vector Problem (SVP) on the lattice.

The ratio can be expressed as follows:

It is easy to see that this ratio reaches its maximum value of when , which simplifies to . Given that the elements are chosen uniformly and approximately equal in norm, , the common parameter is generally taken to be 1.

Since the elements in are uniformly chosen, with , we have . When and take their maximum values, we have the following:

In the generalized NTRU algorithm, since is a large prime and , the length of the target vector is much smaller than the Gaussian expectation of the lattice . This leads to a high probability that the shortest vector of the lattice is either the target vector or its cyclic form.

Thus, breaking the G-NTRU cipher algorithm is somewhat equivalent to solving the Shortest Vector Problem (SVP) in the G-NTRU lattice. For instance, in the case of the NTRU, one of the shortest vectors of the lattice consists of the coefficients of the private key polynomials and . In the Matrix NTRU variant, the matrix formed by the shortest vectors of the lattice represents the private key and . However, the security of the lattice is also influenced by the number of dimensions in the lattice basis. For example, congruent cryptosystems based on the ring of integers have lattice basis matrices of only two dimensions, which makes solving the SVP problem considerably easier.

4.1.2. Generalized AGCD Problem

There are many cryptographic algorithms whose security is built on the AGCD problem. For instance, the DGHV10 algorithm [23] relies on the AGCD problem defined over the ring of integers. In this context, the AGCD problem is then extended from the ring of integers to other algebraic rings.

Definition 14

(Generalized Approximate Greatest Common Divisor, G-AGCD, problem). For an element on an algebraic ring

, given a list of multiples of

with errors over the ring

,, where

,, find p such that

satisfies certain conditions.

The element solved by is not necessarily unique. For example, the subproblems of G-AGCD, such as AGCD over a matrix ring and the AMGCD problem, require finding the original while satisfying specific restrictions. Therefore, when specifying G-AGCD on a particular ring, it is necessary to stipulate specific restrictions.

Definition 15

(Generalized Decisional Approximate Greatest Common Divisor, G-DAGCD, problem). On the algebraic ring

, given multiples of with errors by G-AGCD, b = a × p + e and a randomly chosen element v ∈ R, distinguish between and a random element .

Definition 16

(Learning With Error, LWE). Know the matrix . Given multiples of the matrix and the column vector with errors, where , find the vector .

The Learning With Error (LWE) problem can be reduced to the lattice difficulty problem, specifically the Shortest Vector Problem (SVP). There are many variants of the LWE problem, such as the Ring LWE (RLWE) problem and the polynomial LWE problem. The LWE problem and its variants significantly facilitate the construction of lattice-based cryptosystems. The security of the NTRU is grounded in the RLWE problem.

By expanding the vector and vector in the LWE problem into matrices, the LWE problem becomes analogous to the Augmented Matrix GCD (AMGCD) problem. In fact, the AMGCD problem can also be generalized to the LWE problem. Additionally, AMGCD reduces to the Approximate GCD (AGCD) problem when . As G-AGCD subproblems, AGCD and AMGCD are likely to be difficult, suggesting that G-AGCD also presents a high level of difficulty.

Assumption 1

(G-AGCD). There is no polynomial-time algorithm that finds satisfying certain conditions from a list of multiples of

with errors over the ring

,

, where

,, and

satisfies certain conditions.

Theorem 2.

There exists a polynomial-time algorithm which reduces G-AGCD to MGCD in Assumption 1.

Proof of Theorem 2.

Denote any integer part of as , such as the matrix with . The multiplication of two elements in , , results in being of the form . For one integer part of , we have . From the AGCD problem, it is difficult to find given a list of . By the same reasoning, solving for the other integer parts of is also difficult, implying that finding is difficult. □

Clearly, the G-AGCD problem is reduced to the AGCD problem when there exists only one integer part of the elements in the ring .

Due to three steps, our G-NTRU scheme is semantically secure under the AGCD assumption:

Step 1: AGCD G-AGCD;

Step 2: G-AGCD G-DAGCD;

Step 3: G-DAGCD G-NTRU.

4.1.3. IND-CPA Security

The security of the G-NTRU algorithm presented in this paper relies on the hardness of the G-AGCD problem. In the following sections, the security of the proposed scheme will be demonstrated under the assumption that the G-AGCD problem is computationally difficult.

Lemma 1

(Leftover Hash Lemma, [24]). Let , . Let , and let be an almost universal family of hash functions mapping the value domain to the value domain .The is quasi-random within (on the set ), where is chosen uniformly at random from and uniformly from .

Theorem 3.

The G-NTRU proposed in Section 3 of this paper is IND-CPA-secure.

Proof of Theorem 3.

This theorem is proved below using the game sequence method.

- (1)

- Game 0. The game is designed as an IND-CPA game between a challenger and an adversary of the G-NTRU encryption scheme.

- (2)

- Game 1. Compared to Game 0, in Game 1, the public key generation method no longer generates by the key generation algorithm but randomly and uniformly selects . Since are chosen randomly and uniformly, and since the mapping from to is one-to-one, Game 0 and Game 1 are statistically indistinguishable from the adversary’s perspective.

- (3)

- Game 2. Compared to Game 1, in Game 2, only the target ciphertext is modified. Instead of generating the ciphertext through the encryption algorithm, the challenger chooses randomly and uniformly over . From Definition 15, it is difficult to distinguish between and . From the adversary’s perspective, Game 1 and Game 2 are indistinguishable.

In Game 2, the public key and ciphertext provided by the challenger are chosen randomly and uniformly, resulting in a negligible advantage for the adversary in Game 2. Consequently, the advantage of an adversary attempting to attack the G-NTRU scheme in Game 0 is negligible, indicating that the G-NTRU encryption scheme is IND-CPA-secure. □

4.2. Comparison of Algorithms

The ring underlying the NTRU variants of GR-NTRU is isomorphic to the polynomial ring over the NTRU. In contrast to GR-NTRU, the G-NTRU proposed in this paper generalizes the ring across various basic algebraic NTRU variants. Table 2 presents a comparative overview between GR-NTRU and G-NTRU.

Table 2.

Two types of NTRU variants.

Overall, G-NTRU offers greater flexibility by generalizing algebraic rings, enabling applications across different architectures. In contrast, GR-NTRU leverages the structure of group rings to facilitate diverse security analyses and performance optimizations tailored to specific group ring structures.

Common algebraic structures include integers, matrices, and polynomials, among others, and various NTRU variants can be constructed based on different algebraic rings. This paper compares G-NTRU algorithms over several common algebraic rings, examining their properties across these different structures. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

G-NTRU on different rings.

5. The NTRU Variant Algorithm on Complex Rings

The NTRU variant algorithm on complex rings, referred to as the CNTRU, is derived from the G-NTRU algorithmic framework. The CNTRU is constructed over the ring of complex numbers, shifting the algebraic structure from polynomials used in the traditional NTRU algorithm to pure imaginary numbers. Throughout the operation of the CNTRU algorithm, complex numbers with nonzero real parts are intentionally not produced. The fundamental properties of the CNTRU remain consistent with the findings and studies related to the G-NTRU.

5.1. CNTRU Algorithm

The most significant feature of the NTRU algorithm is its double-mode operation. However, the NTRU variant algorithm defined over the ring of complex numbers lacks modulo operations when due to the structure of complex numbers represented as . When , the complex numbers become purely imaginary, allowing for the modulo operations to be satisfied.

In the context of a complex ring , let , where takes the form . The algebraic structure over the ring determines the parameters used in the CNTRU algorithm.

Given two purely imaginary numbers and (with ), the operations are defined as follows:

For purely imaginary addition:

For purely imaginary multiplication:

For multiplying integers with purely imaginary numbers:

For the modulo operation with purely imaginary numbers:

In this algorithm, the mod ranges over the interval . When , it holds that . The element is defined as the inverse of modulo if it satisfies the following condition:

The following section defines the NTRU algorithm on the ring , specifically focusing on the CNTRU algorithm.

- :

- 1.

- Inputs:

The coefficients of the imaginary part of are then uniformly chosen on as

Choose the parameters and such that , and are coprime (mutually prime), and is much larger than .

Let be the elements in the generalized ring , where has an inverse modulo ( modulo ).

Choose the parameter space as follows:

- 2.

- Calculate the inverse:

Compute the inverse of modulo , denoted as , and the inverse of modulo , denoted as . This operation ensures that

Store this inverse:

- 3.

- Calculate h:

Multiply with , and then reduce the result modulo to obtain

Ensure that all the coefficients of lie in the interval .

If any coefficient , set .

If any coefficient , set .

- 4.

- Output keys:

The public key is

The private key is

- :

- 1.

- Input:

Public key .

Purely imaginary plaintext (where “mmm” is selected such that ).

Random element (where is selected such that ).

Parameter .

- 2.

- Calculate c:

Compute the product , where is the public key obtained from the previous steps.

Ensure that the coefficients of the ciphertext are within the appropriate range .

- 3.

- Output c:

Output the ciphertext :

The first step is to compute the following:

where and its coefficients are kept between .

The second step is to compute the following:

where , and is the decrypted plaintext .

- :

- 1.

- Inputs:

The private key , .

The ciphertext .

A large modulus .

A small modulus .

- 2.

- Calculate a:

Multiply the private key with the ciphertext , and then reduce the result modulo to obtain

After computing , ensure that all its coefficients are within the range .

- 3.

- Calculate b:

Multiply the private key with , and then reduce the result modulo to obtain

Reduce the result ; ensure that all its coefficients lie within the range .

- 4.

- Output b:

Output the ciphertext :

5.2. Parameter Space

NTRU variant algorithms, like the original NTRU algorithm, commonly encounter the issue of decryption failure. This failure typically arises due to the double-modulus operation in the decryption process. Specifically, during the first step of the operation, if , modulus crossing occurs in the second modulus , leading to the inability of the second step of the operation to correctly recover the plaintext m.

In this paper, the decryption failure problem is addressed by carefully adjusting the parameter selection space [25]. By refining the choice of parameters, the likelihood of modulus crossing can be reduced, thus mitigating the occurrence of decryption failures and enhancing the overall reliability of the algorithm.

Specifically, we choose a large prime and define the following sets:

Then, the parameters , , , , and are chosen accordingly. Table 4 presents the specific details:

Table 4.

Correspondence table of parameter sets.

The CNTRU algorithm, in comparison to both the G-NTRU and the original NTRU algorithms, first extends the parameter space from the limited set to the integers . It then compresses the parameter range to the specific sets , , , , and , ensuring a refined and controlled selection of parameters.

5.3. Accuracy Analysis

The following is the explanation of the given parameter assumptions and the correctness of the encryption and decryption processes within the framework:

Parameters and assumptions:

From the relationship , we derive .

Similarly, from , we derive .

For the public key , we have the following:

Expanding the ciphertext , we obtain the following:

For decryption algorithms, there are the following:

Step one:

Step two:

Since is less than and m is less than , the final decrypted result is the same as the plaintext , and the decryption is successful.

For the case of CNTRU decryption failure, the decryption can be satisfied with correct decryption by controlling the parameter space in Section 5.2, as shown by (50):

Then, for the maximum value of , there is the following:

Since the maximum value of is not greater than , the correctness of the subsequent module is guaranteed.

Specific examples will be provided below for smaller values of to facilitate better understanding of the algorithm and its validation, as follows: Given , we compute , rounding each result to one decimal place.

Thus, we have ,,,,.

(1) :

For the large prime , the parameter space is chosen such that ,,. In this case, we generate , , and .

The inverse of modulo and modulo is calculated as follows:

This is achieved by using the conjugate property and the Euclidean algorithm.

Next, we compute the public key as follows:

Calculating this step by step as follows:

Output public key and private key .

(2) :

We select the pure dummy plaintext from and randomly generate from . We then compute the ciphertext as described in Formula (40):

Substituting in the values:

Output the ciphertext .

(3):

The first step is to compute the following:

Output .

The second step is to compute the following:

Since the plaintext , we find that . Therefore, the decryption is successful.

5.4. Security Analysis

This subsection analyzes the security of the CNTRUs from two main aspects, namely security on the lattice and the semantic security of the CNTRU.

5.4.1. Lattice Analysis

From Section 4.1.1 of this paper, it is evident that the lattice basis matrices for the algorithms of NTRU variants on different algebraic rings differ primarily in the choice of the -matrix. Below is the definition of the CNTRU lattice:

Definition 17

(CNTRU lattice). The CNTRU lattice L(B) is generated by the 2N × 2N dimensional lattice basis matrix B constructed from the public key h of the CNTRU algorithm.

where is the matrix generated by the public key in the form , is the integer part of the public key , and .

Theorem 4.

The , formed by multiplying the private key by and concatenating it with , lies on the lattice .

Proof of Theorem 4.

The equation implies that there exists some integer vector u such that . Here, is the imaginary part of the private key , and is the imaginary part of . Consider the vector . When multiplied by the lattice basis matrix , it yields the following:

Since can be written as a linear combination of the lattice basis matrix with integer coefficients, it is a vector on the lattice . This proves that indeed lies on the lattice .

From the Gaussian Heuristic, the expected length of the shortest vector in the lattice is given by the following:

The length of the target vector is given by the following:

The function ) compares the length of the target vector with the Gaussian expectation of the shortest vector:

From the Gaussian Heuristic, the Gaussian expectation of the length of the shortest vector on the lattice can be obtained as follows:

And the length of the target vector is as follows:

The constructor is as follows:

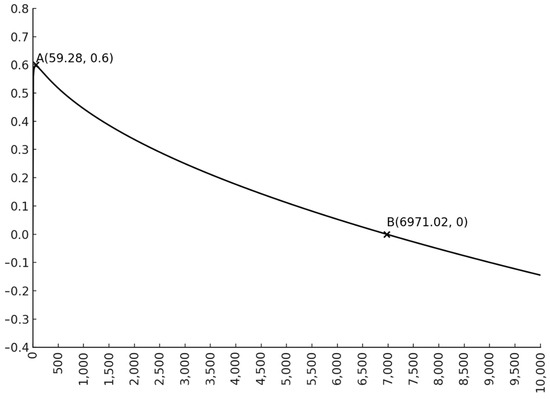

The function is shown in Figure 1, where . It is a convex function with extrema at and zeros at and . Here, , with values of , , and retained to two significant decimal places.

Figure 1.

Plot of function.

The CNTRU lattice is a discrete integer lattice, and is a large integer. When , the target vector length is greater than the Gaussian expectation of the CNTRU lattice, with the difference being approximately 0.596, which makes the target vector length close to the Gaussian expectation of the CNTRU lattice. However, when , the target vector length is less than the Gaussian expectation of the CNTRU lattice. Thus, with a high probability, the shortest vector on the CNTRU lattice is the target vector . □

Therefore, breaking the private key of the CNTRU cryptographic algorithm is somewhat equivalent to solving the Shortest Vector Problem (SVP) in the CNTRU lattice. Compared to the CNTRU lattice, which is two-dimensional, the NTRU lattice and matrix NTRU lattice are high-dimensional lattices, providing higher security on the lattice.

5.4.2. Semantic Security Analysis

The security of the CNTRU scheme proposed in this paper relies on the difficulty of the DAGCD problem. The security of the scheme is demonstrated under the assumption that DAGCD is hard.

Theorem 5.

The CNTRU encryption scheme proposed in Section 5.1 of this paper is IND-CPA-secure.

Proof of Theorem 5.

The following proves this theorem by using the game sequence method.

- (1)

- Game 0. The game is designed as an IND-CPA game between a challenger and an adversary of the CNTRU encryption scheme.

- (2)

- Game 1. Compared to Game 0, in Game 1, the public key generation method no longer generates by the key generation algorithm but randomly and uniformly selects . Since is randomly and uniformly chosen and to is a one-to-one mapping, Game 0 and Game 1 are statistically indistinguishable to the adversary.

- (3)

- Game 2. Compared to Game 1, in Game 2, only the target ciphertext is modified. Instead of generating the ciphertext by the encryption algorithm, the challenger chooses randomly and uniformly over . From DAGCD, it is difficult to distinguish between and . Therefore, Game 1 and Game 2 are indistinguishable to the adversary.

Since the public key and ciphertext provided by the challenger in Game 2 are randomly and uniformly chosen, the adversary has a negligible advantage in Game 2. Consequently, the advantage of an adversary attacking the generalized NTRU scheme in Game 0 is negligible, proving that the CNTRU encryption scheme is IND-CPA-secure. □

5.5. Efficiency Analysis

The algebraic structure of the parameters in the CNTRU algorithm is purely imaginary, ensuring that no complex numbers with nonzero real parts are generated during the algorithm’s operations. The operations in the CNTRU algorithm are as efficient as integer modulo operations, and the computational overhead is measured in terms of bit operations.

The modulo addition operation for integers has a time complexity of , while the modulo multiplication operation has a time complexity of . Inverses of complex numbers can be computed efficiently by conjugation, whereas inverses of purely imaginary numbers are computed similarly to integer inverses, with a time complexity of , by using the Euclidean algorithm. Table 5 summarizes the inverse time complexity for the three algebraic structures.

Table 5.

Inverse time complexity.

Regarding the time complexity of the CNTRU encryption algorithm, in the CNTRU algorithm, the encryption operation is defined as . Ignoring the overhead of randomly selecting , the time complexity of the CNTRU encryption algorithm is determined by the modular multiplication of with , the modular multiplication with , and the modular addition with the polynomial mmm, which is . Therefore, the overall time complexity of the encryption process is .

Similarly, the time complexity of the CNTRU decryption algorithm is based on the decryption operations and . The time spent on decryption is dominated by the modular multiplications, each with a complexity of , leading to an overall decryption time complexity of .

Given that the length of the encrypted plaintext is , encrypting and decrypting 1 bit of plaintext and ciphertext both involve a feature of constant time complexity, making these operations very fast compared to the NTRU and Matrix NTRU algorithms, as illustrated in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of encryption and decryption time complexity levels.

The CNTRU algorithm offers the significant advantage of a fast key generation process, resulting in higher algorithmic efficiency. When constructing the scheme, the same parameter space control method is employed to avoid decryption failures, similar to those observed in the traditional NTRU algorithm. However, due to the CNTRU lattice being two-dimensional—a low-dimensional lattice—it is less secure compared to other NTRU algorithm variants.

Notably, in the context of the complex ring, if the imaginary parts of all complex numbers are zero, the algorithm behaves identically to an NTRU variant built on an integer ring, making it equivalent to a congruent cipher algorithm. Conversely, if the real parts of the complex numbers are all zero, the algorithm becomes identical to the CNTRU algorithm.

Constructing NTRU variant algorithms on complex rings not only enriches the system of NTRU variant algorithms but also provides lateral verification of the generality of the G-NTRU algorithm.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we summarize different NTRU algorithms over algebraic rings, integrate NTRU lattices over these rings, and analyze attacks on these lattices. Extending related hard problems facilitates the study of the security of the extended NTRU algorithm. The integer ring AGCD problem is extended to the G-AGCD problem over generalized rings, and the extended G-NTRU algorithm is proved to be semantically secure under the assumption of the hardness of the G-AGCD problem. However, the complexity of the G-AGCD problem requires further study. Additionally, the CNTRU is proposed based on the G-NTRU algorithmic framework, and the generality of the G-NTRU framework is verified.

The NTRU algorithm holds significant practical importance as a generalized post-quantum cryptographic framework. The algebraic ring generalization of the G-NTRU enables it to operate on a wide range of structures, such as rings of integers, rings of complex numbers, and rings of matrices. This flexibility enhances its applicability to diverse security needs and performance requirements. However, a limitation of the G-NTRU is that its complexity varies depending on the chosen algebraic structures and rings, with implementations based on complex structures potentially leading to decreased computational efficiency. Furthermore, the G-NTRU algorithm operating on low-dimensional rings is less secure than its counterparts on high-dimensional rings.

For future research, several directions can be pursued. First, the parameter selection for the G-NTRU can be further optimized to reduce computational complexity and communication overhead, making it more suitable for application scenarios that require high real-time performance. Second, the theoretical analysis of the anti-quantum security of the G-NTRU can be enhanced by investigating the intractability of the G-AGCD problem within various algebraic structures, providing more rigorous complexity proofs. Finally, exploring the applicability of other algebraic rings could generalize the G-NTRU to incorporate novel mathematical structures, leading to more efficient and secure algorithmic implementations.

This paper enriches the research direction of post-quantum cryptography related to the NTRU by proposing the G-NTRU framework, which extends the applicability and security analysis dimensions of NTRU algorithms. The G-NTRU provides a new perspective for developing anti-quantum encryption algorithms and establishes a solid theoretical foundation for academic research on NTRU variants. In the future, the application and further exploration of the G-NTRU will contribute to the realization of secure, reliable, and efficient communication systems in the quantum era.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.W. and Z.L.; methodology, Q.W.; software, Q.W.; validation, Q.W. and Z.L.; formal analysis, Q.W. and Z.L.; investigation, Q.W. and Z.L.; resources, Q.W. and Z.L.; data curation, Q.W., J.Z. and Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.W. and J.Z.; writing—review and editing, Q.W. and J.Z.; visualization, Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62472040, in part by the Copyright Research Project of China Copyright Protection Center (BQ2024017), in part by the Beijing Municipal Education Commission Scientific Research Project under Grant KM202010015009, in part by the Beijing Municipal Education Commission Scientific Research Project Funding under Grant KM202110015004, in part by the Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication Doctoral Funding Project under Grant 27170120003/020, in part by the Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication Research Innovation Team Project under Grant Eb202101, in part by the Intramural Discipline Construction Project of Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication under Grant 21090121021, in part by the Key Educational Reform Project of Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication under Grant 22150121033/009, in part by the General Research Project of Basic Research of Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication under Grant Ec202201, in part by the Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication Doctoral Funding Project under Grant 27170122006, in part by BIGC Project (Ec202201), in part by the general research project of Beijing Association of Higher Education in 2022 (No. MS2022093), and in part by R&D Program of Beijing Municipal Education Commission(KM202310015002).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rivest, R.L.; Shamir, A.; Adleman, L. A method for obtaining digital signature and public key cryptosystems. Commun. ACM 2004, 21, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankerson, D.R.; Vanstone, S.A.; Menezes, A.J. Guide to Elliptic Curve Cryptography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- ElGamal, T. A public key cryptosystem and a signature scheme based on discrete logarithms. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1985, 31, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillier, P. Public-key cryptosystems based on composite degree residuosity classes. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT ‘99: International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques, Prague, Czech Republic, 2–6 May 1999; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Shor, P.W. Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM J. Comput. 1997, 26, 1484–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST. Solicit, Evaluate, Standardize and One or More Quantum Resistant Public-Key Cryptographic Algorithms. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/post-quantum-cryptography (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Hoffstein, J.; Lieman, D.; Pipher, J.; Silverman, J.H. NTRU: A Public Key Cryptosystem; NTRU Cryptosystems, Inc.: Acton, MA, USA, 1999; Available online: http://www.ntru.com (accessed on 1 January 1999).

- Yassin, H.R.; Al-Saidi, N.M.G. An innovative bicartisian algebra for designing of highly performed NTRU like cryptosystem. Malays. J. Math. Sci. 2019, 13, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Akleylek, S.; Kaya, N. New quantum secure key exchange protocols based on MaTRU. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Digital Forensic and Security, ISDFS 2018, Antalya, Turkey, 22–25 March 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, L.; Xu, H.; Miao, L.; Zhou, X. A group-based NTRU-like public-key cryptosystem for IoT. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 75732–75740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Sastry, C.V.; Pradhan, J. A matrix formulation for NTRU cryptosystem. In Proceedings of the 16th IEEE International Conference on Networks (ICON 2008), New Delhi, India, 12–14 December 2008; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caboara, M.; Caruso, F.; Traverso, C. Gröbner bases for public key cryptography. In Proceedings of the Twenty-First International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation, Linz/Hagenberg Austria, 20–23 July 2008; pp. 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Vats, N. NNRU, a noncommutative analogue of NTRU. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0902.1891. [Google Scholar]

- Yassein, H.R.; Al-Saidi, N.M.G.; Farhan, A.K. A new NTRU cryptosystem outperforms three highly secured NTRU analog systems through an innovational algebraic structure. J. Discret. Math. Sci. Cryptogr. 2022, 25, 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Alsood, H.H.; Yassein, H.R. QOTRU: A new design of NTRU public key encryption via Qu-Octonion Subalgebra. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1999, 012097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, C.M.; Binh, N. DBTRU, a new NTRU-like cryptosystem based on dual binary truncated polynomial rings. In Proceedings of the 2015 2nd National Foundation for Science and Technology Development Conference on Information and Computer Science (NICS), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 10–11 September 2015; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gaithuru, J.N.; Salleh, M.; Mohamad, I. Mini NTRU degree truncated polynomial ring (mini-NTRU): A simplified implementation using binary polynomials. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 8th International Conference on Engineering Education (ICEED), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–8 December 2016; pp. 270–275. [Google Scholar]

- Karbasi, A.H.; Atani, R.E. ILTRU: An NTRU-Like public key cryptosystem over ideal lattices. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2015, 2015, 549. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Lei, H.; Hu, Y. D-NTRU: More efficient and average-case IND-CPA secure NTRU variant. Inf. Sci. 2018, 438, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doröz, Y.; Sunar, B. Flattening NTRU for Evaluation Key Free Homomorphic Encryption. J. Math. Cryptol. 2020, 14, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Padhye, S. Generalizations of NTRU cryptosystem. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2016, 9, 6315–6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, T.; Dahan, X.; Sakurai, K. Characterizing NTRU-Variants Using Group Ring and Evaluating their Lattice Security. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2015, 2015, 1170. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, M.; Gentry, C.; Halevi, S.; Vaikuntanathan, V. Fully homomorphic encryption over the integers. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques—EUROCRYPT 2010, French Riviera, France, 30 May–3 June 2010; pp. 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Impagliazzo, R.; Zuckerman, D. How to recycle random bits. In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS 1989), Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 30 October–1 November 1989; pp. 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.C.; Wu, Q.H.; Song, J.S.; Peng, H.P. Study on the parameters of the matrix NTRU cryptosyste. J. Henan Polytech. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).