Abstract

In recent years, commercial and research interest in service robots working in everyday environments has grown. These devices are expected to move autonomously in crowded environments, maximizing not only movement efficiency and safety parameters, but also social acceptability. Extending traditional path planning modules with socially aware criteria, while maintaining fast algorithms capable of reacting to human behavior without causing discomfort, can be a complex challenge. Solving this challenge has involved the development of proactive systems that take into account cooperation (and not only interaction) with the people around them, the determined incorporation of approaches based on Deep Learning, or the recent fusion with skills coming from the field of human–robot interaction (speech, touch). This review analyzes approaches to socially aware navigation and classifies them according to the strategies followed by the robot to manage interaction (or cooperation) with humans.

1. Introduction

Society 5.0 represents a new paradigm in which people and artificial beings cooperate in routines, environments, and the interactions of everyday life [1]. This cooperation is intended to be natural and intuitive, and the new artificial actors are expected to behave appropriately. Service robots are one of the technologies with the greatest number of potential applications in this new social paradigm [2]. They are also one of the most profoundly affected by the new technical and contextual complexities arising from these new requirements [3]. Service robots, being inevitably social when used in everyday life scenarios, face the most challenging technical, ethical, social, and legislative demands. In particular, Socially Aware Robotics (SAWR) is an emerging area of research that seeks to understand how cognitive robots can be aware of their social context and use this capability to behave as more accessible, accepted, and useful devices, being able to establish more appropriate and effective interactions to assist humans [4]. A robot aiming to exploit socially enhanced autonomous capabilities needs to perceive its environment and reach a certain level of understanding of its context. However, to be truly socially aware, a robot must not only react intentionally to perceived changes, but it must also be able to predict or learn what the behavior of the humans surrounding it will be, anticipating consequences and selecting the best possible and most comprehensible action, while respecting social conventions [5,6].

One of the essential capabilities of most robotic solutions, more deeply affected by these new social requirements, is navigation. Service robots working in daily life environments cannot just search for the shortest collision-free path. They should also solve a multi-variable optimization problem that considers, for example, human comfort and social rules. As a result, traditional navigation approaches are no longer adequate due to their limited flexibility, and new proposals arise. The growing importance of the topic has given rise to several review articles analyzing these proposals in different ways. Concepts regarding the human factor were highlighted in the survey papers on proxemics ([7,8]), and semantic and social mapping ([9]). The review paper by Gao and Huang [10] focused on the evaluation methods, scenarios, datasets, and metrics commonly used in previous socially-aware navigation research. Zhu and Zhang [11] reviewed Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) methods and DRL-based navigation frameworks. They differentiated between several typical application scenarios: local obstacle avoidance, indoor navigation, multi-robot navigation, and social navigation. Chik et al. [12] focused on robot navigation as a hierarchical task, involving a collection of sub-problems that can range from the high-level decision to reactive avoidance of low-level obstacles. The review highlighted how the whole navigation stack should evolve to address the problem of dealing with dynamic human environments, including human detection, tracking, and predictive modeling, at a more local level, and considering social costs at a higher level.

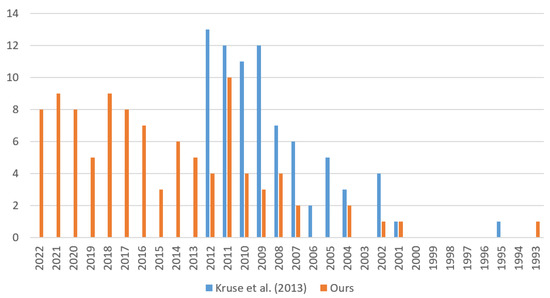

The paper by Kruse et al. [13] discusses human-aware navigation. In this paper, the authors state that ‘the robotics and human–robot interaction (HRI) communities have not yet produced a holistic approach to human-aware navigation’ [13], even though they identified 77 citations between 1995 and 2012 closely related to this topic. They also defined two axes on which to classify these papers. First, they established four categories: comfort, naturalness, sociability, and others. In the second axis, the technologies on which the articles focus are considered. The categories in this second axis are pose selection, global planning, behavior selection, and local planning.

The present survey extends the previous work of Kruse et al. [13] in two dimensions. On the one hand, it updates the analysis considering new approaches and research conducted in the last ten years in the field of social navigation. On the other hand, this survey focuses on those methods in which the robot modifies its behavior in the presence of another mobile agent, or traces a path (e.g., avoiding disturbing a group of people talking to each other). Hence, it differs from the work of Kruse et al. [13] as the basis of our categorization will not be functionality, but the degree to which the method employed for reacting in the presence of humans is able to learn from previous observations or predict the near future. Prediction and Learning will be the terms that will guide the literature search, establishing subgroups in the more global group of social navigation. Moreover, this survey would like to draw attention to papers that focus on social comfort and explore how social navigation methods are evolving to equip robots with more human-like skills. As robots become increasingly similar to humans, understanding the complexities of social norms and adapting to them becomes more important. These papers shed light on how robots can be designed to better interact with humans in social situations.

2. Methodology

This section describes the criteria used both to select the set of articles considered for this review article (Section 2.1) and to organize them into different groups (Section 2.2).

2.1. Article Selection Criteria

We carefully curated a collection of papers on the topics of social navigation, with a special interest in two keywords, prediction and learning. Our selection process involved a thorough review of the literature, drawing from the works of Kruse et al. [13], Chik et al. [12], Gao and Huang [10] and Zhu and Zhang [11], and extended with recent citations. We selected the most relevant papers that explored the areas of social navigation, comfort, prediction, and learning. These papers were further narrowed down by evaluating the quality and relevance of the references cited in each article. Finally, we prioritized the papers that were most frequently cited in previous works.

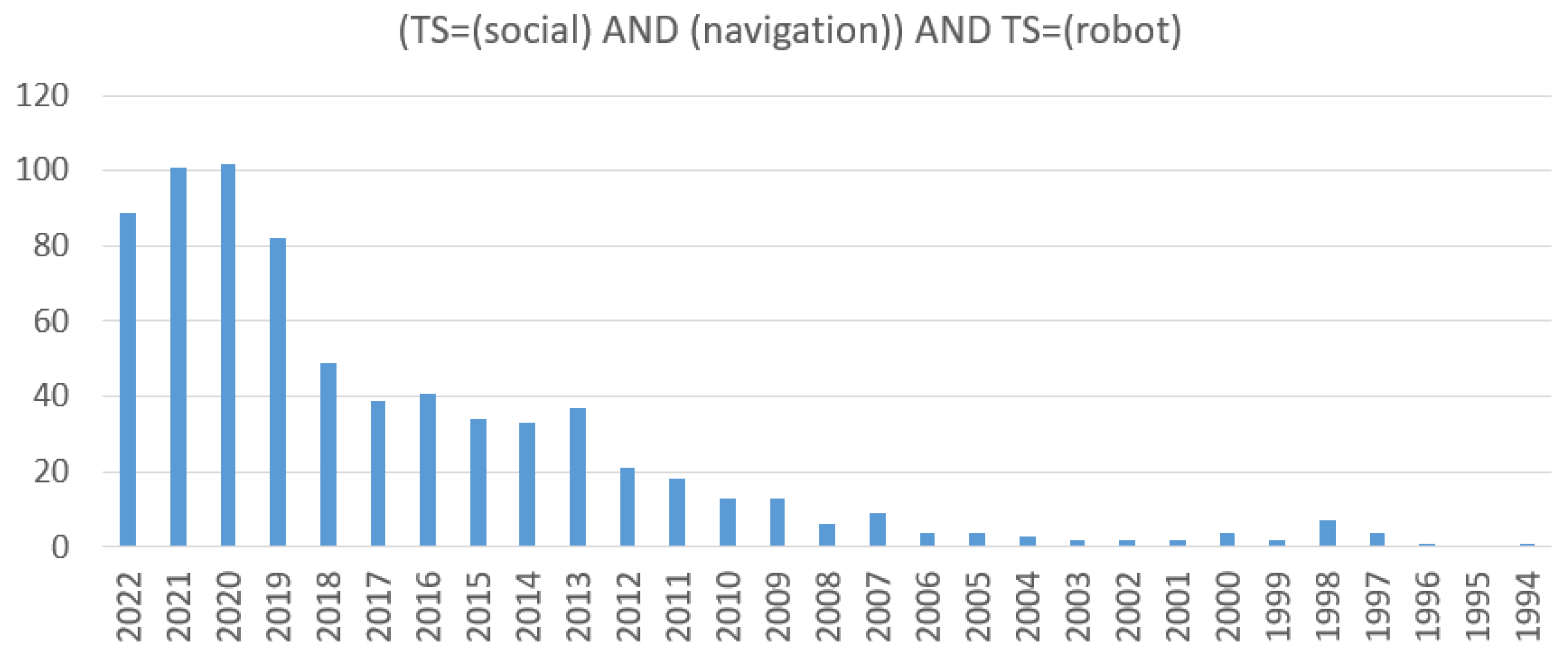

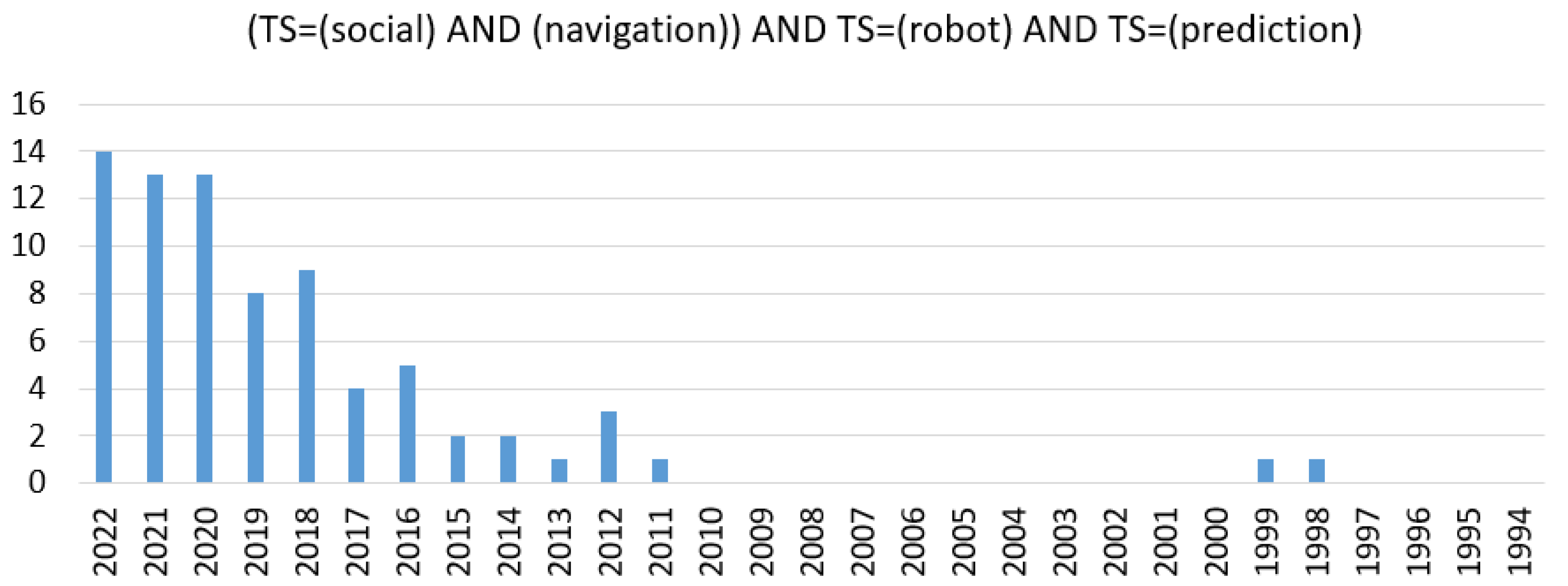

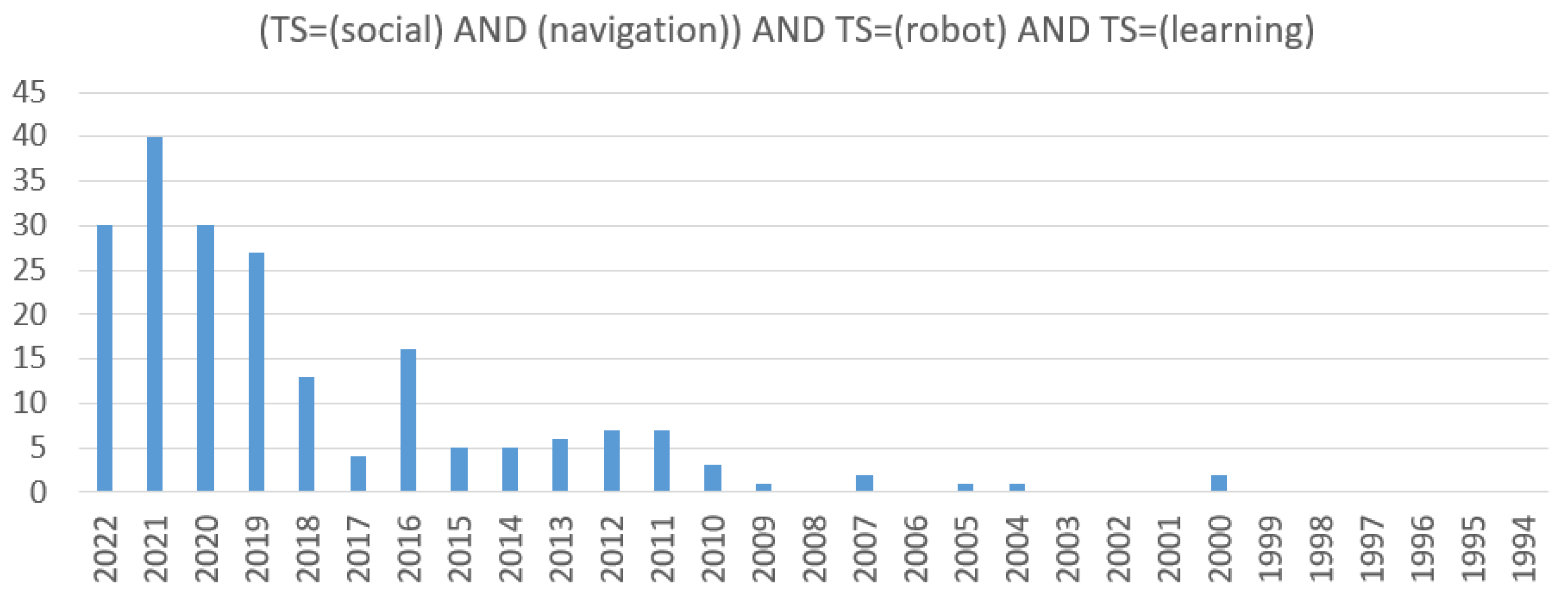

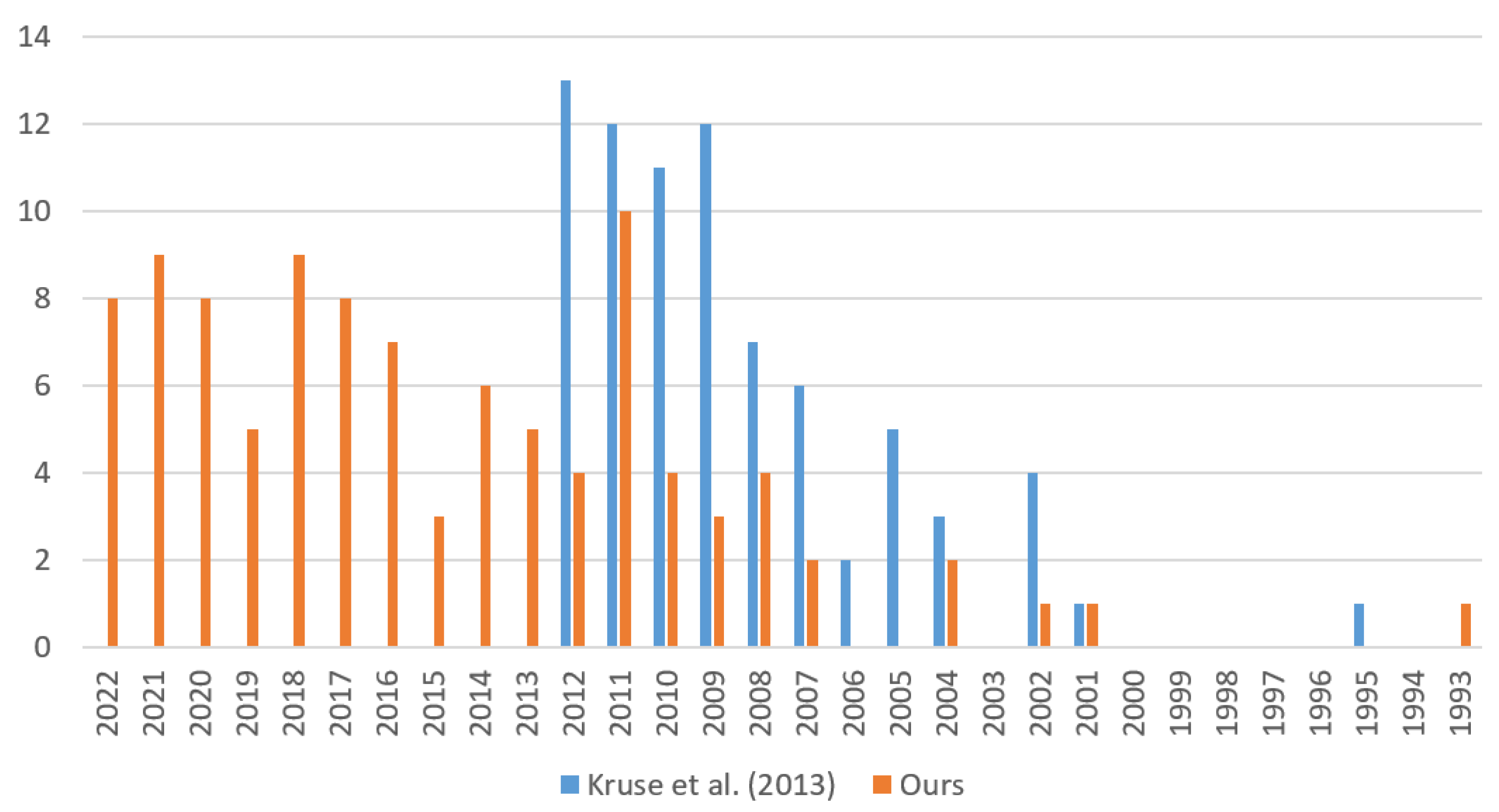

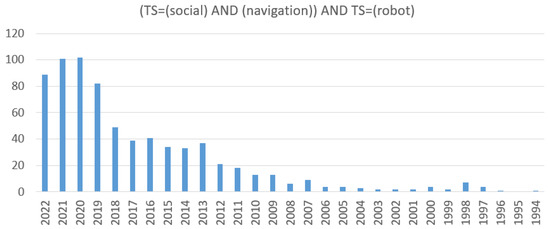

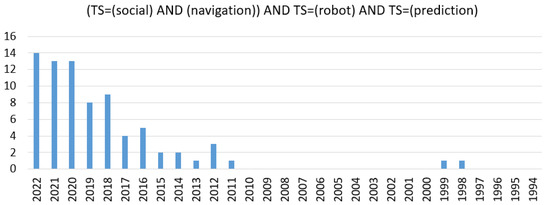

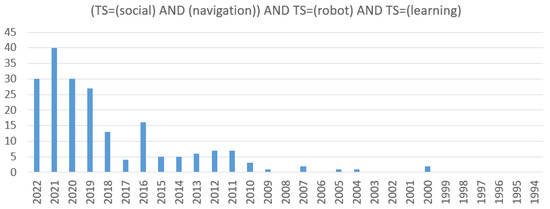

To gain insight into the number of papers published on our focus topics, we can refer to the graphs in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3. These graphics were generated using data from the Web of Science (https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science/, accessed on 13 February 2023). For the topic (TS = (social AND navigation)) AND TS = (robot), we obtain 723 results in the range from 1994 to 2022 (data from the current year, 2023, were not included as the year has not finished and these data could disturb the statistics). Adding TS = (learning), the number of citations reduces to 207 results (Figure 3). With TS = (prediction), the number is reduced to 80 results (Figure 2). From this large dataset, we have covered in this survey 100 papers. Figure 4 compares the papers covered by the survey by Kruse et al. [13] and the current review.

Figure 1.

Web of Science Analyze filter: (TS = (social AND navigation)) AND TS = (robot).

Figure 2.

Web of Science Analyze filter: (TS = (social AND navigation)) AND TS = (robot) AND TS = (prediction).

Figure 3.

Web of Science Analyze filter: (TS = (social AND navigation)) AND TS = (robot) AND TS = (learning).

Figure 4.

Distribution of publications over years considered by the review paper by Kruse et al. [13] and the current survey.

2.2. Article Classification Criteria

As mentioned above, the goal of socially aware navigation is not only to find a collision-free path from a starting point to a destination. This navigation process also requires carefully taking into account the movement of people around the robot, and the interactions processes between the robot and these people. When the number of people is small, few interactions are required to avoid possible collisions. People tend to move along rectilinear trajectories over long periods of time. However, when the density of people increases, problems arise [14]. In these scenarios, people have to frequently change their motion states (direction of travel, but also velocity or acceleration) in real time, to avoid collisions while trying to reach their destinations. Linear models are no longer correct for modeling interactions (human–robot, but also human–human). The perception of the robot’s movement by others becomes particularly relevant. Thus, in addition to being safe, it is important that the motion of the robot is legible, allowing people in the vicinity of the robot to easily understand its movement intention [15].

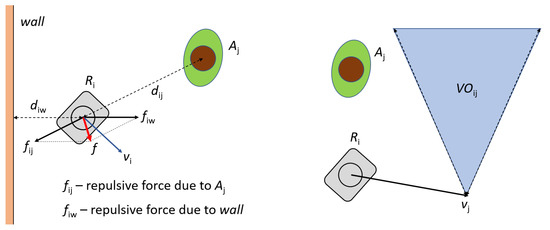

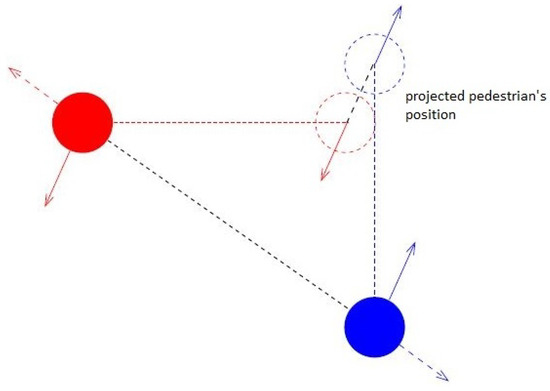

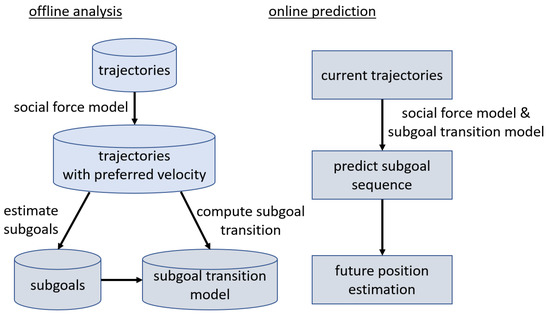

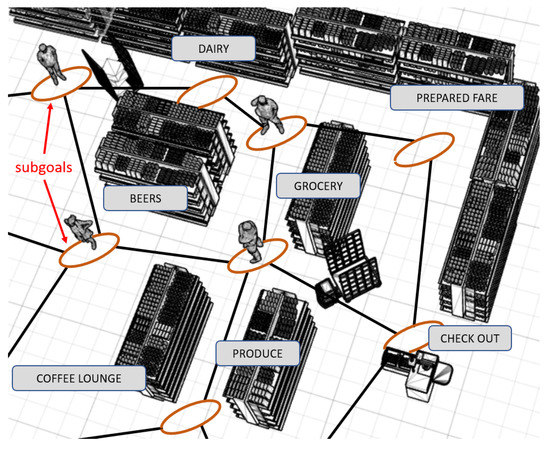

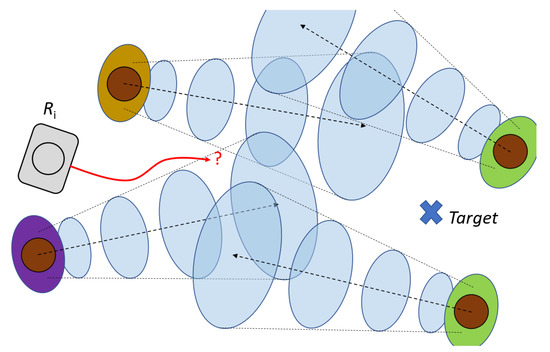

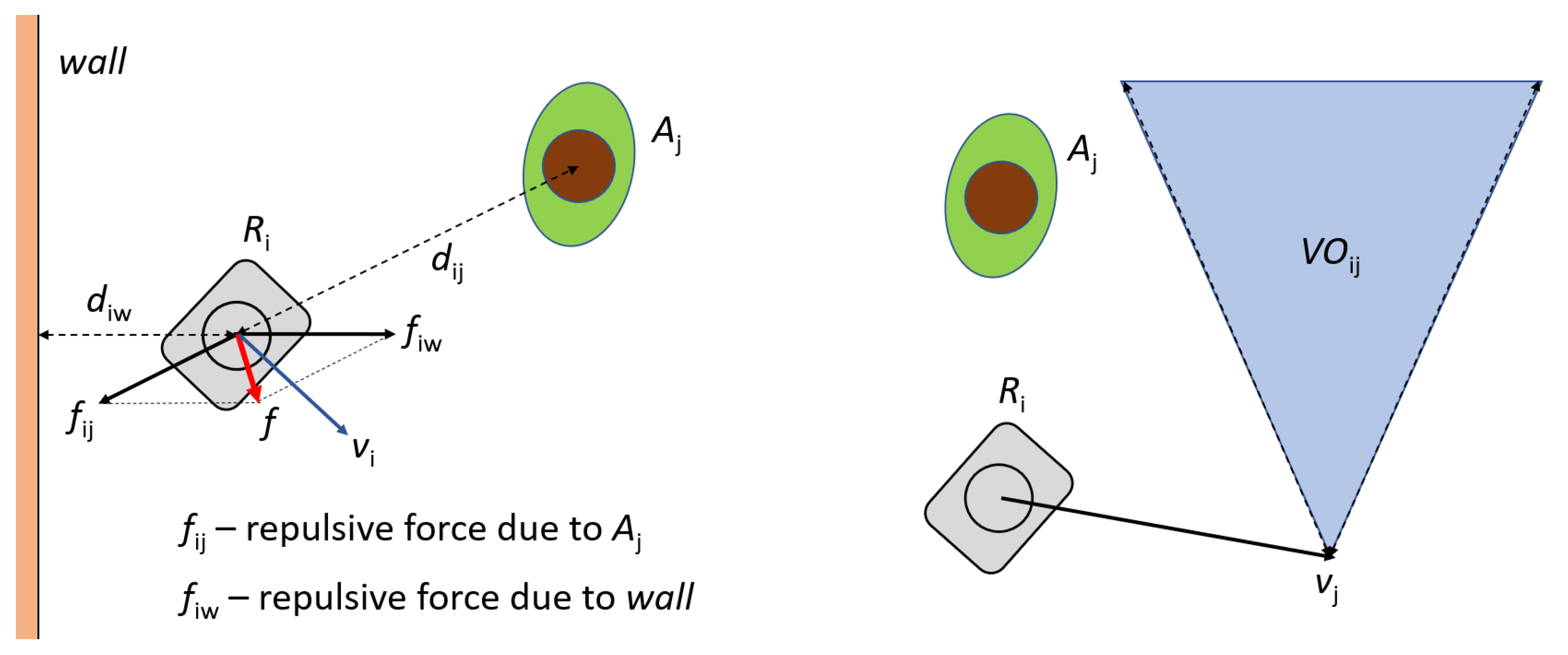

Analyzing the evolution of socially aware robot navigation addresses two major topics: (i) evaluating how robot social skills have made human interactions more comfortable and natural; (ii) evaluating how algorithms solve navigation in crowded scenarios. Following on previous work from several researchers on robot navigation in dense crowds, we will group in this survey works on robot navigation into three categories [14,16]: (1) reactive approaches; (2) proactive approaches; and (3) learning-based approaches. Moreover, we added a fourth category: (4) multi-behaviour navigation approaches. In reactive approaches, the robot reacts to other mobile agents through one-step look ahead strategies [14]. These approaches are typically very efficient (e.g., the social force model [17]). Proactive approaches predict the behavior of the human and then plan a suitable path. Predictions can be based on reasoning (assumptions of how agents behave in general), or learning (justified by observations of how agents behave) [13]. Strategies for prediction can deal with human motion [18] or intentions [14]. Learning-based approaches aim towards the robot learning the navigation policy, and adapting it to the target scenario. Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has been extensively employed for solving this problem [11,19]. Finally, we added multi-behaviour navigation approaches as a separate subsection. Significantly, these methods address the question of whether it can be useful to consider interaction actions, such as touching, gesturing, or speaking, for the sake of allowing robots to navigate in dynamic, crowded environments. The importance of being able to coordinate different robotic functionalities (navigation, dialogue) to solve a navigation goal will grow in the coming years as service robots actually share the environment with people.

4. Discussion

Robot navigation within humans has been a goal of the robotics community for decades. Reactive approaches, such as the ones presented in this study, were designed to handle dynamic scenarios, but have severe constraints (e.g., constant velocities for moving obstacles) that do not allow them to handle complex environments. These approaches do not model humans and their not always predictable behavior. Moreover, they cannot take into account multi-agent behaviors, such as joint planning. To deal with these problems, proactive approaches focus on human modeling and reciprocal planning. They have faced several problems, related to, for example, giving relevance to social comfort (practically covered by most of the proactive and learning-based approaches), the interaction with humans but also with groups of humans, or the Freezing Robot Problem. The problem of the first approaches for modeling human motion was solved by considering goal-based policies. Considering that people are moving towards certain goals, the robot can project their motion (trajectories) on a map and trace a route for avoiding them. However, these goals are not necessarily available to the robot. Given the positions in a map of all people surrounding the robot, proxemics can be used for extending this map, taking into account social norms. In addition to space, other factors need to be taken into account. Traits such as body posture and facial expressions can help the robot to be more approachable and predictable, further improving its ability to function in social environments. As we review in this work, proactive approaches have evolved to manage human–robot interaction and, subsequently, human–robot cooperation. Cooperative planning provides navigation efficiency and also human acceptability [120]. In parallel, learning-based approaches have emerged in this last decade to learn motion planners. As data-driven approaches, the major strength of these methods is that they are able to estimate a practical human model without having to specify social norms, as they are implicitly present in the data. In recent years, the major limitation was that these approaches need large data sets, which were captured from virtual scenarios. The great difference between the simulation environment and the real-world one is the major challenge to transfer the trained model to a real robot. Virtual-to-real approaches are currently able to generalize the learned planners and to satisfactorily deployed them in unseen real environments [101]. It is clear that real-world experiments involving actual people and uncontrolled environments are crucial to validating the effectiveness of social navigation. These experiments reveal the challenges and complexities that arise in real-life situations, providing valuable insights into how robots can improve their navigation skills.

The use of databases to calibrate or train the system is usually necessary in all methods examined. These datasets are usually obtained by recording pedestrian trajectories with cameras or sensors in specific environments, or are collected by experts. Relying solely on recorded datasets may not be good practice, as the goal is to generalize pedestrian behavior, which requires a variety of datasets from different sources. In the case of proactive methods, the use of real data is common. For example, the Edinburgh Informatics Forum Pedestrian Database was successfully used by Ferrer and Sanfeliu [48,74]. Others, such as Luber et al. [127] and Ferrer and Sanfeliu [74], used The Freiburg People Tracker. However, this is not the case, as mentioned above, for learning-based methods. These usually describe the tools used to generate virtual learning environments, which enable them to obtain the volumes of data needed to successfully complete the training. For these methods to be successful in real environments, the data used for prediction or learning must be as realistic and diverse as possible. Therefore, it is crucial to collect data sets from a variety of sources and experts.

Two relevant topics have begun to be taken into account in the most recent proposals. On the one hand, the possibility for the robot to handle different behavioral options, and that, depending on the context, the robot itself self-adapts its behavior. Self-adaptation is a topic widely addressed in robotics, with specific proposals related to navigation and including parameter reconfiguration, algorithm changes, or even reconfiguration of the architecture itself [123,124]. Although it has not been analyzed in depth in this survey, some references were added to Section 3.4. On the other hand, navigation has started to be considered as a task that is not only about finding a path free of obstacles, or that this path is as close as possible to the one a person would follow, but may require specific skills that we would not include a priori in a navigation stack. Thus, to avoid getting stuck in an environment densely crowded with people, the robot may need to talk to people, or even push them lightly. This multi-modal collaboration scenario can be useful for a robot to become more socially aware, allowing it, for example, to greet people it crosses paths with.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This survey analyzes the problem of robot navigation in every day, crowded environments. The analysis of recent studies highlights the advancements in robot navigation, particularly in the area of social navigation. Although purely reactive proposals were presented, when a mobile robot is deployed in an environment where people move around freely, it becomes necessary for this robot to predict the movement of these other agents. The use of prediction enables the robot to quickly adapt and optimize its navigation, To generate these predictions, navigation algorithms have evolved from a human–robot interaction scenario to a human–robot cooperation one, where it is expected that people will proactively help the robot to find a free and safe path. However, the complexity and variety of human behavior in the real world can make this assumption fail. Recent approaches propose that the mobile robot can interact with people not only because their paths may cross on the map, but more actively, through gestures, vocalization and touch, to require their help in navigating [16,120,121]. As a signaling mechanism for conveying an intention to humans, incorporating features such as body posture and gestures also contributes to making the robot appear more friendly and predictable to humans, leading to better human–robot interactions and an overall improved experience.

Future work in this field should focus on thoroughly reviewing existing experiments and exploring ways to further improve robot performance. It is also important to keep abreast of the latest developments and advances in this field. In addition, as mentioned above, it could be interesting to analyze methods using record data and methods using test databases and to analyze the behavior of the methods in real environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.-R., J.P.B. and A.B.; Funding acquisition, J.P.B. and A.B.; Investigation, S.G.-R., J.P.B., A.H.-P. and A.B.; Methodology, S.G.-R., J.P.B. and A.B.; Supervision, A.B. and J.P.B.; Validation, A.B. and A.H.-P.; Writing—original draft, S.G.-R.; Writing—review & editing, S.G.-R., J.P.B., A.H.-P. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partially funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 825003 (DIH-HERO SUSTAIN and DIH-HERO GAITREHAB), and projects TED2021-131739B-C21 and PDC2022-133597-C42, funded by the Gobierno de España and FEDER funds.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gladden, M.E. Who Will Be the Members of Society 5.0? Towards an Anthropology of Technologically Posthumanized Future Societies. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPARC. Robotics 2020 Multi-Annual Roadmap for Robotics in Europe; Technical Report; SPARC: The Partnership for Robotics in Europe, euRobotics Aisbl: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seibt, J.; Damholdt, M.F.; Vestergaard, C. Integrative social robotics, value-driven design, and transdisciplinarity. Interact. Stud. 2020, 21, 111–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Rossi, A.; Dautenhahn, K. The Secret Life of Robots: Perspectives and Challenges for Robot’s Behaviours during Non-interactive Tasks. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2020, 12, 1265–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandini, G.; Sciutti, A.; Vernon, D. Cognitive Robotics. In Encyclopedia of Robotics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, T.; Bensch, S. Understandable robots-What, Why, and How. Paladyn J. Behav. Robot. 2018, 9, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Martinez, J.; Spalanzani, A.; Laugier, C. From Proxemics Theory to Socially-Aware Navigation: A Survey. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2015, 7, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarakoon, S.M.B.P.; Muthugala, M.A.V.J.; Jayasekara, A.G.B.P. A Review on Human–Robot Proxemics. Electronics 2022, 11, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, K.; Kostavelis, I.; Gasteratos, A. Recent trends in social aware robot navigation: A survey. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2017, 93, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Huang, C.M. Evaluation of Socially-Aware Robot Navigation. Front. Robot. AI 2022, 8, 721317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, T. Deep reinforcement learning based mobile robot navigation: A review. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2021, 26, 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chik, S.; Fai, Y.; Su, E.; Lim, T.; Subramaniam, Y.; Chin, P. A review of social-aware navigation frameworks for service robot in dynamic human environments. J. Telecommun. Electron. Comput. Eng. 2016, 8, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, T.; Pandey, A.K.; Alami, R.; Kirsch, A. Human-aware robot navigation: A survey. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1726–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, F.; Lou, Y. Interactive Model Predictive Control for Robot Navigation in Dense Crowds. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 2289–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisbot, E.A.; Marin-Urias, L.F.; Alami, R.; Simeon, T. A Human Aware Mobile Robot Motion Planner. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2007, 23, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamezaki, M.; Tsuburaya, Y.; Kanada, T.; Hirayama, M.; Sugano, S. Reactive, Proactive, and Inducible Proximal Crowd Robot Navigation Method Based on Inducible Social Force Model. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 3922–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, P.; Shiller, Z. Motion planning in dynamic environments using the relative velocity paradigm. In Proceedings of the 1993 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Atlanta, GA, USA, 2–6 May 1993; Volume 1, pp. 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, A.; Palmieri, L.; Arras, K.O. Joint Long-Term Prediction of Human Motion Using a Planning-Based Social Force Approach. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 4571–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Won, J.; Lee, J. Crowd Simulation by Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM SIGGRAPH Conference on Motion, Interaction and Games, MIG ‘18, Limassol, Cyprus, 8–10 November 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, S.; Koval, A.; Kanellakis, C.; Agha-mohammadi, A.; Nikolakopoulos, G. D*+s: A Generic Platform-Agnostic and Risk-Aware Path Planing Framework with an Expandable Grid. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.05563. [Google Scholar]

- Shiller, Z.; Large, F.; Sekhavat, S. Motion planning in dynamic environments: Obstacles moving along arbitrary trajectories. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seoul, Korea, 21–26 May 2001; Volume 4, pp. 3716–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, B.; Prassler, E. Reflective navigation: Individual behaviors and group behaviors. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), New Orleans, LA, USA, 26 April–1 May 2004; Volume 4, pp. 4172–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulgenzi, C.; Spalanzani, A.; Laugier, C. Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance in uncertain environment combining PVOs and Occupancy Grid. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Roma, Italy, 10–14 April 2007; pp. 1610–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, O. Real-time obstacle avoidance for manipulators and mobile robots. In Proceedings of the 1985 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), St. Louis, MO, USA, 25–28 March 1985; Volume 2, pp. 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Qi, L.; Yuan, H.; Guo, X.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Z.; Yang, T. Path planning method with improved artificial potential field—A reinforcement learning perspective. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 135513–135523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, J.; Koren, Y. The vector field histogram-fast obstacle avoidance for mobile robots. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1991, 7, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babinec, A.; Duchoň, F.; Dekan, M.; Mikulová, Z.; Jurišica, L. Vector Field Histogram* with look-ahead tree extension dependent on time variable environment. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2018, 40, 1250–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, R.; Driankov, D. Velocity potentials and fuzzy modeling of fluid streamlines for obstacle avoidance of mobile robots. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE), Istanbul, Turkey, 2–5 August 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhu, G.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, L. Improved Social Force Model Based on Emotional Contagion and Evacuation Assistant. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 195989–196001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.; Malviya, V.; Kala, R. Social Cues in the Autonomous Navigation of Indoor Mobile Robots. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2021, 13, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.; Molnar, P. Social Force Model for Pedestrian Dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 1995, 51, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trautman, P.; Krause, A. Unfreezing the Robot: Navigation in Dense, Interacting Crowds. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010; pp. 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, X.T.; Ngo, T.D. Toward Socially Aware Robot Navigation in Dynamic and Crowded Environments: A Proactive Social Motion Model. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2017, 14, 1743–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snape, J.; Berg, J.V.D.; Guy, S.J.; Manocha, D. The Hybrid Reciprocal Velocity Obstacle. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2011, 27, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, J.; Lin, M.; Manocha, D. Reciprocal Velocity Obstacles for real-time multi-agent navigation. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Pasadena, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2008; pp. 1928–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanlungo, F.; Ikeda, T.; Kanda, T. Social force model with explicit collision prediction. EPL Europhys. Lett. 2011, 93, 68005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, G.; Garrell, A.; Sanfeliu, A. Social-aware robot navigation in urban environments. In Proceedings of the 2013 European Conference on Mobile Robots (ECMR), Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 September 2013; pp. 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiomi, M.; Zanlungo, F.; Hayashi, K.; Kanda, T. Towards a Socially Acceptable Collision Avoidance for a Mobile Robot Navigating Among Pedestrians Using a Pedestrian Model. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2014, 6, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautman, P.; Ma, J.; Murray, R.M.; Krause, A. Robot navigation in dense human crowds: Statistical models and experimental studies of human—Robot cooperation. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2015, 34, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Large, F.; Vasquez, D.; Fraichard, T.; Laugier, C. Avoiding cars and pedestrians using velocity obstacles and motion prediction. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, Parma, Italy, 14–17 June 2004; pp. 375–379. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, S.; Horiuchi, T.; Kagami, S. A probabilistic model of human motion and navigation intent for mobile robot path planning. In Proceedings of the 2009 4th International Conference on Autonomous Robots and Agents, Wellington, New Zealand, 10–12 February 2009; pp. 663–668. [Google Scholar]

- Du Toit, N.E.; Burdick, J.W. Robot Motion Planning in Dynamic, Uncertain Environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2012, 28, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.M.; Doshi-Velez, F.; Huang, A.S.; Roy, N. A Bayesian nonparametric approach to modeling motion patterns. Auton. Robot. 2011, 31, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoude, G.; Luders, B.; Joseph, J.M.; Roy, N.; How, J.P. Probabilistically safe motion planning to avoid dynamic obstacles with uncertain motion patterns. Auton. Robot. 2013, 35, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziebart, B.D.; Ratliff, N.; Gallagher, G.; Mertz, C.; Peterson, K.; Bagnell, J.A.; Hebert, M.; Dey, A.K.; Srinivasa, S. Planning-based prediction for pedestrians. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), St. Louis, MO, USA, 11–15 October 2009; pp. 3931–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennewitz, M.; Burgard, W.; Thrun, S. Learning motion patterns of persons for mobile service robots. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 May 2002; Volume 4, pp. 3601–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuderer, M.; Kretzschmar, H.; Sprunk, C.; Burgard, W. Feature-Based Prediction of Trajectories for Socially Compliant Navigation. In Robotics: Science and Systems VIII; MIT Press: Sydney, Australia, 2013; pp. 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, G.; Sanfeliu, A. Comparative analysis of human motion trajectory prediction using minimum variance curvature. In Proceedings of the 2011 6th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Lausanne, Switzerland, 8–11 March 2011; pp. 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabtoul, M.; Spalanzani, A.; Martinet, P. Towards Proactive Navigation: A Pedestrian-Vehicle Cooperation Based Behavioral Model. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 6958–6964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

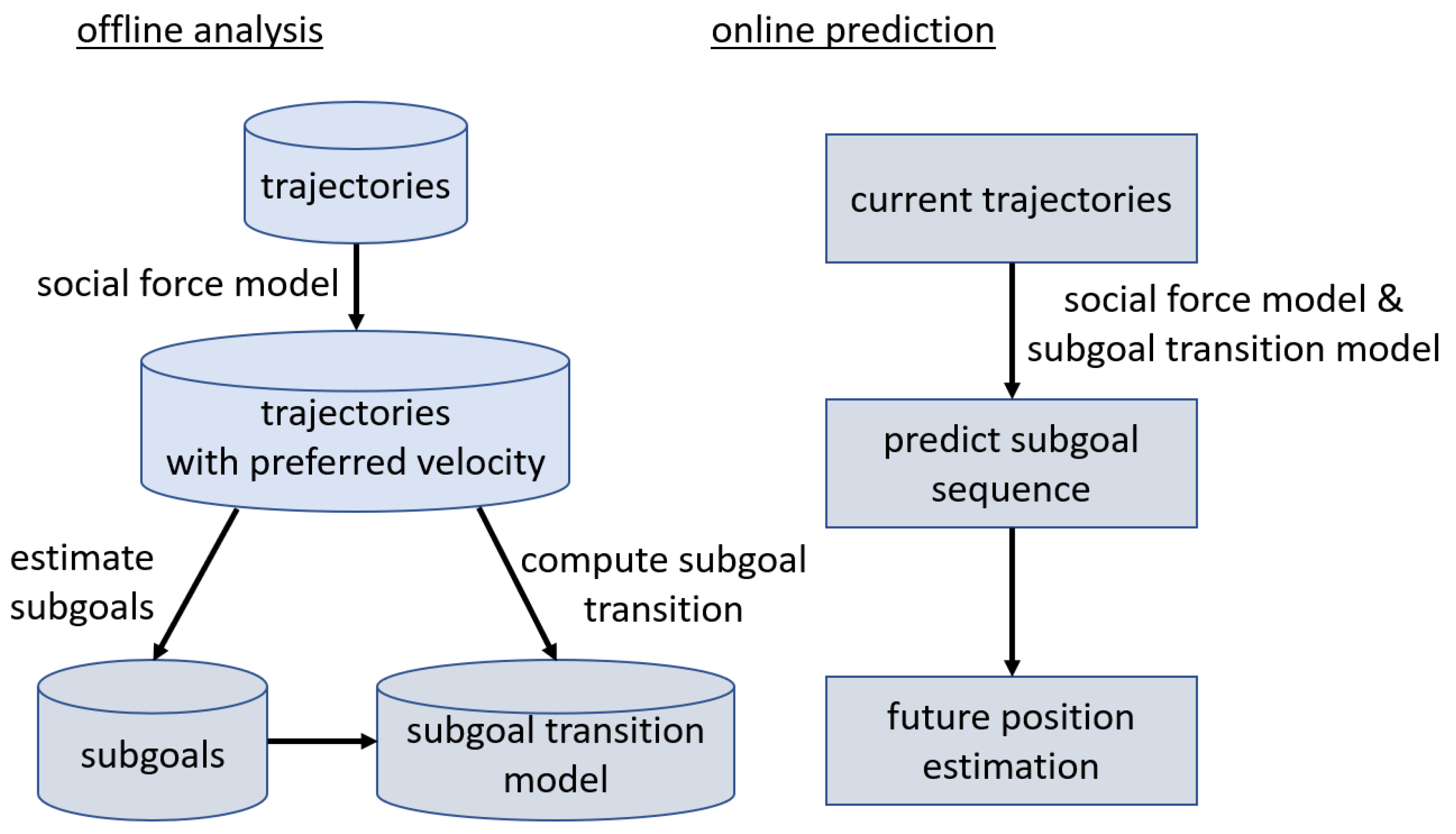

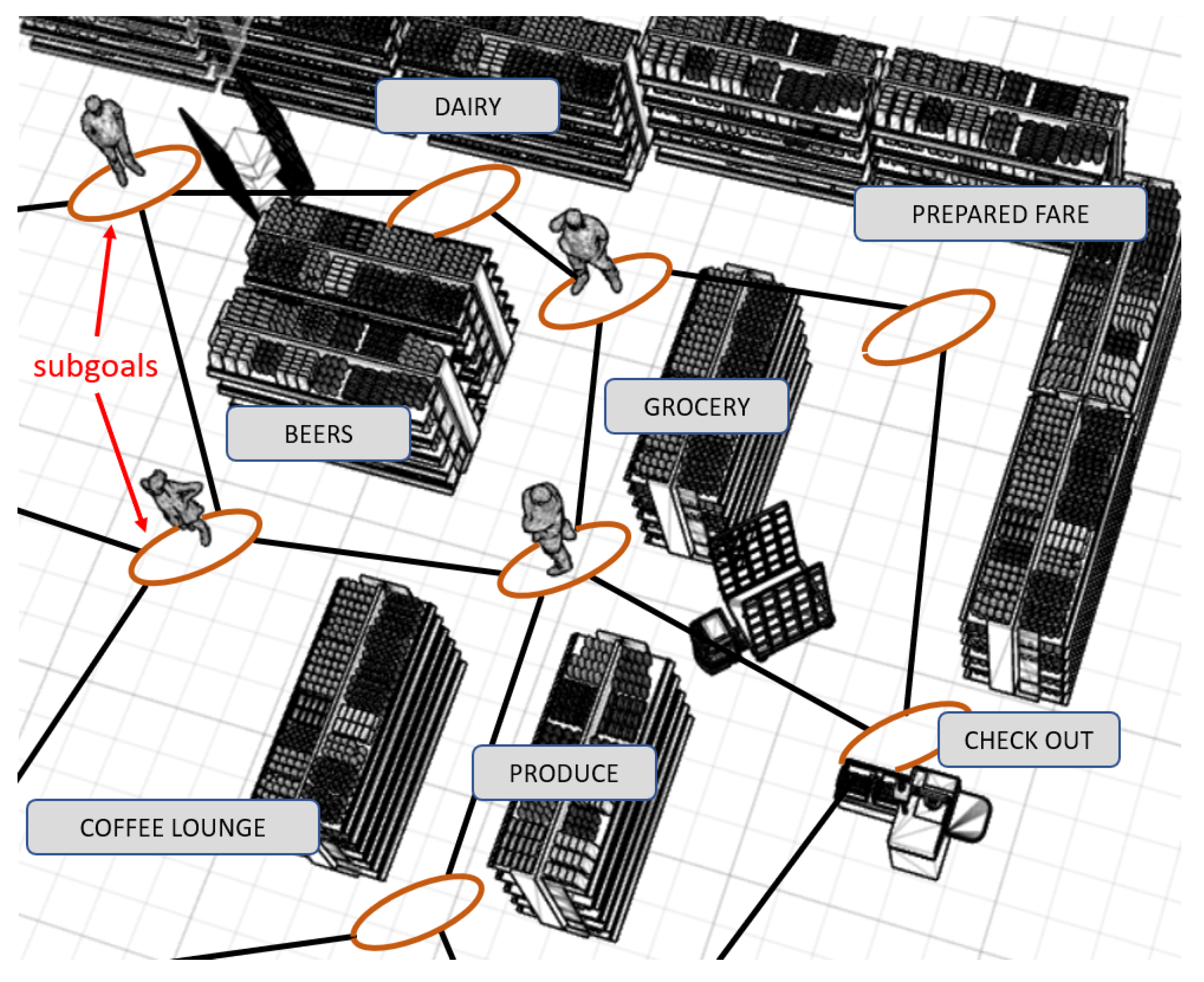

- Ikeda, T.; Chigodo, Y.; Rea, D.; Zanlungo, F.; Shiomi, M.; Kanda, T. Modeling and Prediction of Pedestrian Behavior based on the Sub-goal Concept. In Robotics: Science and Systems VIII; MIT Press: Sydney, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luber, M.; Tipaldi, G.D.; Arras, K. Place-Dependent People Tracking. Int. J. Robotic Res. 2011, 30, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, G.; Garrell, A.; Sanfeliu, A. Robot companion: A social-force based approach with human awareness-navigation in crowded environments. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013; pp. 1688–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, A.; Manso, L.J.; Macharet, D.G.; Bustos, P.; Núñez, P. Socially aware robot navigation system in human-populated and interactive environments based on an adaptive spatial density function and space affordances. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2019, 118, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, R.; Mataric, M.J. A Probabilistic Framework for Autonomous Proxemic Control in Situated and Mobile Human-Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the HRI ’12, Seventh Annual ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Boston, MA, USA, 5–8 March 2012; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 193–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, R.; Atrash, A.; Matarić, M.J. Proxemic Feature Recognition for Interactive Robots: Automating Metrics from the Social Sciences. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Reuse, Pohang, Republic of Korea, 13–17 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Svenstrup, M.; Tranberg, S.; Andersen, H.J.; Bak, T. Pose estimation and adaptive robot behaviour for human–robot interaction. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; pp. 3571–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

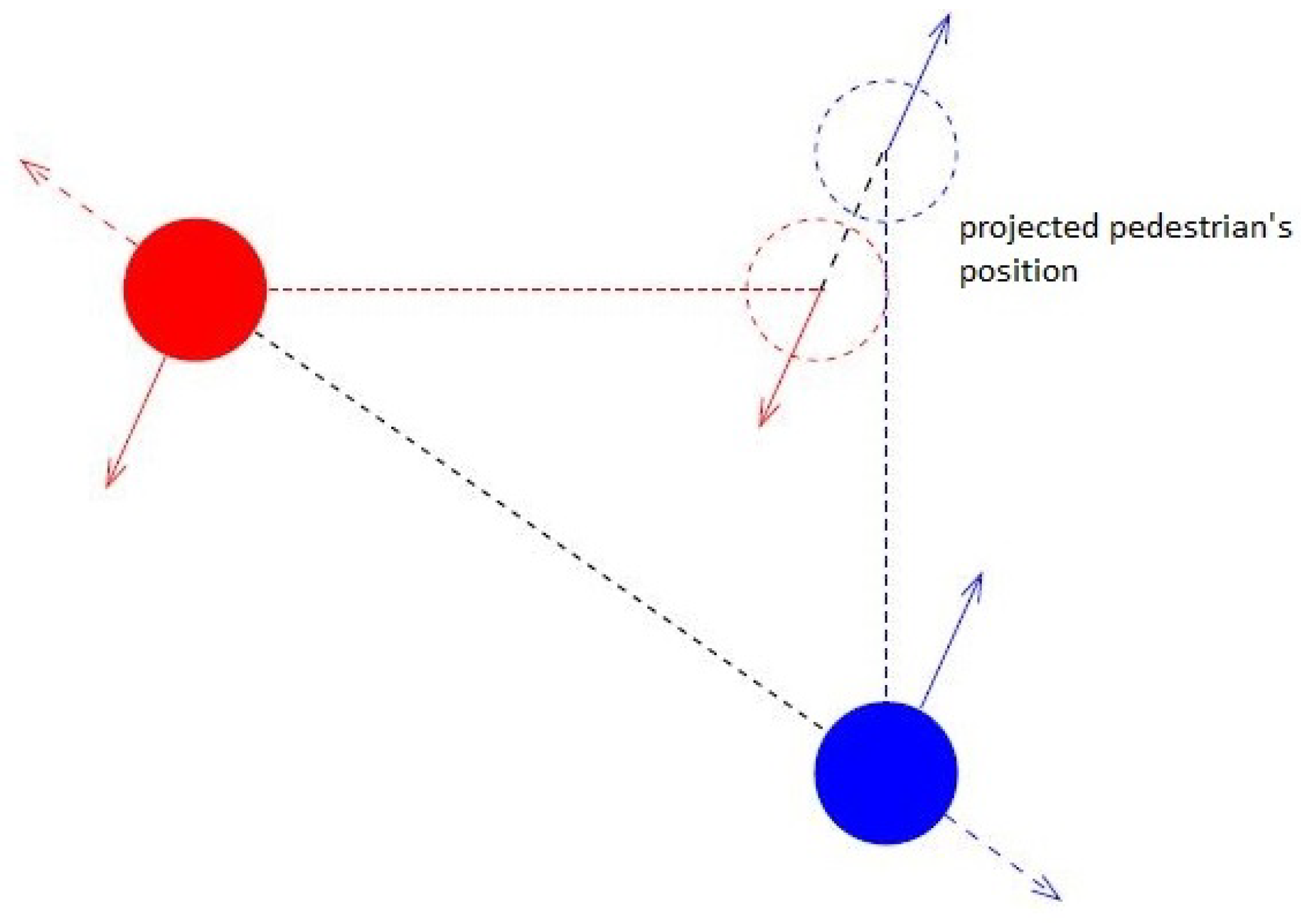

- Castro-González, A.; Shiomi, M.; Kanda, T.; Salichs, M.A.; Ishiguro, H.; Hagita, N. Position prediction in crossing behaviors. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010; pp. 5430–5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratsamee, P.; Mae, Y.; Ohara, K.; Takubo, T.; Arai, T. Human–robot collision avoidance using a modified social force model with body pose and face orientation. Int. J. Humanoid Robot. 2013, 10, 1350008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, G.; Sanfeliu, A. Proactive Kinodynamic Planning using the Extended Social Force Model and Human Motion Prediction in Urban Environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014; pp. 1730–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, F.; Fontanelli, D.; Garulli, A.; Giannitrapani, A.; Prattichizzo, D. When Helbing meets Laumond: The Headed Social Force Model. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 55th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 3548–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, J.; Guy, S.J.; Lin, M.; Manocha, D. Reciprocal n-Body Collision Avoidance. In Proceedings of the Robotics Research; Pradalier, C., Siegwart, R., Hirzinger, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bera, A.; Kim, S.; Randhavane, T.; Pratapa, S.; Manocha, D. GLMP- realtime pedestrian path prediction using global and local movement patterns. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Stockholm, Sweden, 16–21 May 2016; pp. 5528–5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

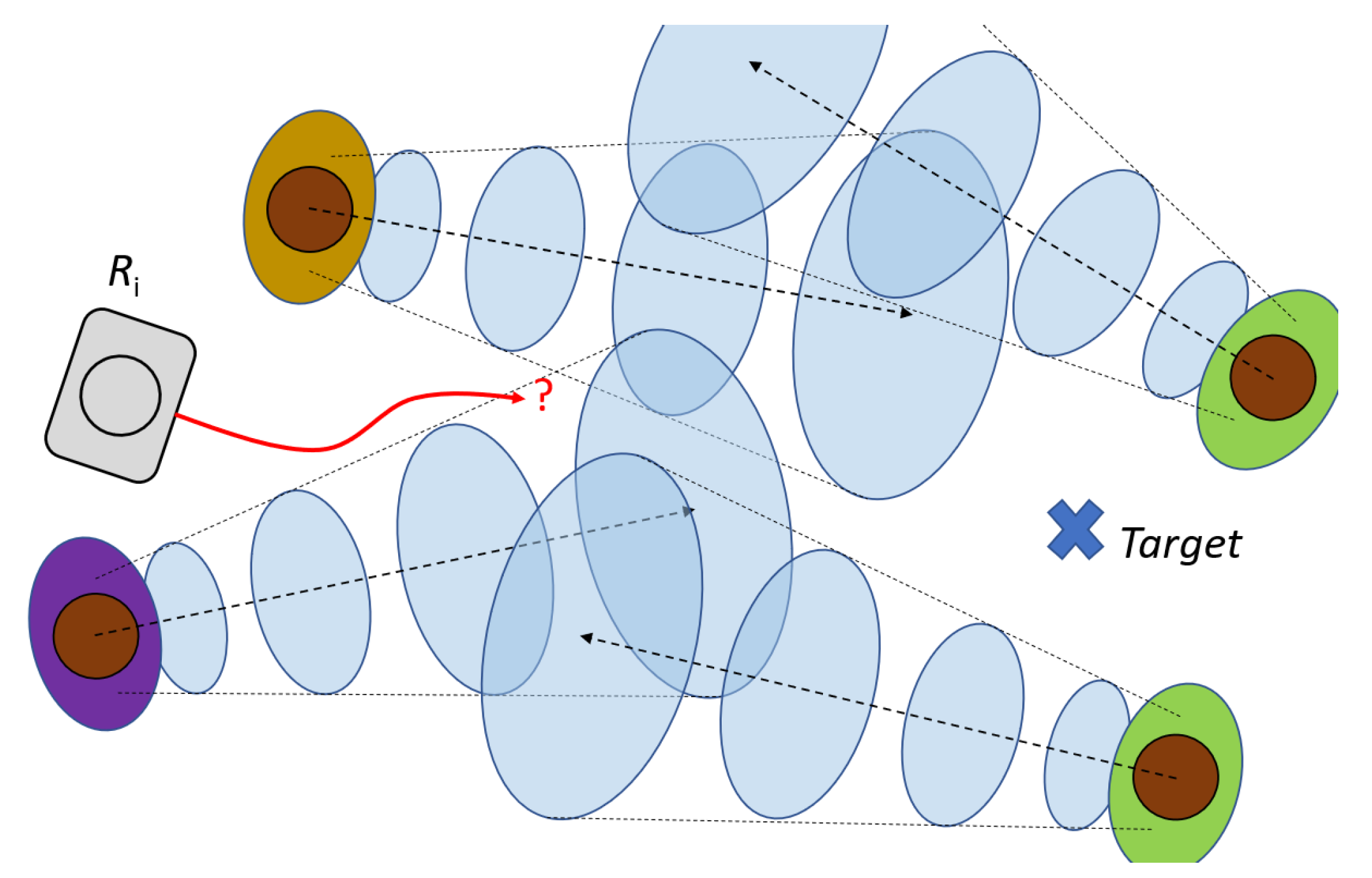

- Luo, Y.; Cai, P.; Bera, A.; Hsu, D.; Lee, W.S.; Manocha, D. PORCA: Modeling and Planning for Autonomous Driving Among Many Pedestrians. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 3418–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Guy, S.J.; Liu, W.; Wilkie, D.; Lau, R.W.; Lin, M.C.; Manocha, D. BRVO: Predicting pedestrian trajectories using velocity-space reasoning. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2015, 34, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Xie, X.; Lv, P.; Niu, J.; Wang, H.; Li, C.; Zhu, R.; Deng, Z.; Zhou, B. Crowd Behavior Simulation with Emotional Contagion in Unexpected Multihazard Situations. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. 2021, 51, 1567–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, S.; Guy, S.J.; Zafar, B.; Manocha, D. Virtual Tawaf: A Velocity-Space-Based Solution for Simulating Heterogeneous Behavior in Dense Crowds. In Modeling, Simulation and Visual Analysis of Crowds; The International Series in Video Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 11, pp. 181–209. [Google Scholar]

- Alahi, A.; Goel, K.; Ramanathan, V.; Robicquet, A.; Fei-Fei, L.; Savarese, S. Social LSTM: Human Trajectory Prediction in Crowded Spaces. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemula, A.; Muelling, K.; Oh, J. Social Attention: Modeling Attention in Human Crowds. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 4601–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foka, A.; Trahania, P. Probabilistic Autonomous Robot Navigation in Dynamic Environments with Human Motion Prediction. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2010, 2, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenstrup, M.; Bak, T.; Andersen, H.J. Trajectory planning for robots in dynamic human environments. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010; pp. 4293–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J.; Kuipers, B. A smooth control law for graceful motion of differential wheeled mobile robots in 2D environment. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 4896–4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J.; Johnson, C.; Kuipers, B. Robot navigation with model predictive equilibrium point control. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 4945–4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Martinez, J.; Spalanzani, A.; Laugier, C. Understanding human interaction for probabilistic autonomous navigation using Risk-RRT approach. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–30 September 2011; pp. 2014–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, G.; Sanfeliu, A. Bayesian Human Motion Intentionality Prediction in urban environments. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2014, 44, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, R.; Chadalavada, R.; Lilienthal, A.J. Recognition of human–robot motion intentions by trajectory observation. In Proceedings of the 2016 9th International Conference on Human System Interactions (HSI), Portsmouth, UK, 6–8 July 2016; pp. 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, G.; Zulueta, A.; Cotarelo, F.; Sanfeliu, A. Robot social-aware navigation framework to accompany people walking side-by-side. Auton. Robot. 2017, 41, 775–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khambhaita, H.; Alami, R. A Human-Robot Cooperative Navigation Planner. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE International Conference, Vienna, Austria, 6–9 March 2017; pp. 161–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabtoul, M.; Spalanzani, A.; Martinet, P. Proactive Furthermore, Smooth Maneuvering For Navigation Around Pedestrians. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 4723–4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Liu, M.; Everett, M.; How, J.P. Decentralized non-communicating multiagent collision avoidance with deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Kreiss, S.; Alahi, A. Crowd-Robot Interaction: Crowd-Aware Robot Navigation with Attention-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 6015–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Dugas, D.; Cesari, G.; Siegwart, R.; Dubé, R. Robot Navigation in Crowded Environments Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–29 October 2020; pp. 5671–5677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, P.; Vollmer, C.; Ferris, B.; Fox, D. Learning to navigate through crowded environments. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–8 May 2010; pp. 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Pineau, J. Socially Adaptive Path Planning in Human Environments Using Inverse Reinforcement Learning. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2016, 8, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Everett, M.; Liu, M.; How, J.P. Socially aware motion planning with deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; pp. 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, M.; Chen, Y.F.; How, J.P. Motion Planning Among Dynamic, Decision-Making Agents with Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; pp. 3052–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsani, S.S.; Muhammad, M.S. Socially Compliant Robot Navigation in Crowded Environment by Human Behavior Resemblance Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 5223–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, L.; Liu, J. Crowd-Comfort Robot Navigation Among Dynamic Environment Based on Social-Stressed Deep Reinforcement Learning. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2022, 14, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugas, D.; Nieto, J.; Siegwart, R.; Chung, J.J. NavRep: Unsupervised Representations for Reinforcement Learning of Robot Navigation in Dynamic Human Environments. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 7829–7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

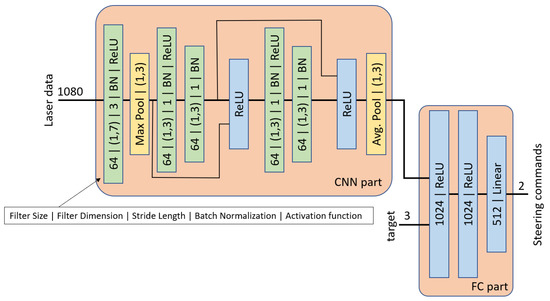

- Gil, O.; Garrell, A.; Sanfeliu, A. Social Robot Navigation Tasks: Combining Machine Learning Techniques and Social Force Model. Sensors 2021, 21, 7087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, A.; Faust, A.; Chiang, H.T.L.; Hsu, J.; Kew, J.C.; Fiser, M.; Lee, T.W.E. Long-Range Indoor Navigation with PRM-RL. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2020, 36, 1115–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Shi, B.E.; Liu, M. Robot Navigation in Crowds by Graph Convolutional Networks with Attention Learned From Human Gaze. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 2754–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Sun, S.; Zhao, X.; Tan, M. Learning to Navigate in Human Environments via Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing, Sydney, Australia, 8–11 December 2019; Gedeon, T., Wong, K.W., Lee, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 418–429. [Google Scholar]

- Long, P.; Fan, T.; Liao, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; Pan, J. Towards Optimally Decentralized Multi-Robot Collision Avoidance via Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 6252–6259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromniak, M.; Stenzel, J. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Mobile Robot Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th Asia-Pacific Conference on Intelligent Robot Systems (ACIRS), Nagoya, Japan, 13–15 July 2019; pp. 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Shi, L.; Xu, M.; Hwang, K.S. End-to-End Navigation Strategy with Deep Reinforcement Learning for Mobile Robots. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 2393–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jiang, R.; Ge, S.; Lee, T. Role Playing Learning for Socially Concomitant Mobile Robot Navigation. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2018, 3, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.A.; Fidjeland, A.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.F.R.; Yusuf, S.H. Mobile Robot Navigation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Processes 2022, 10, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

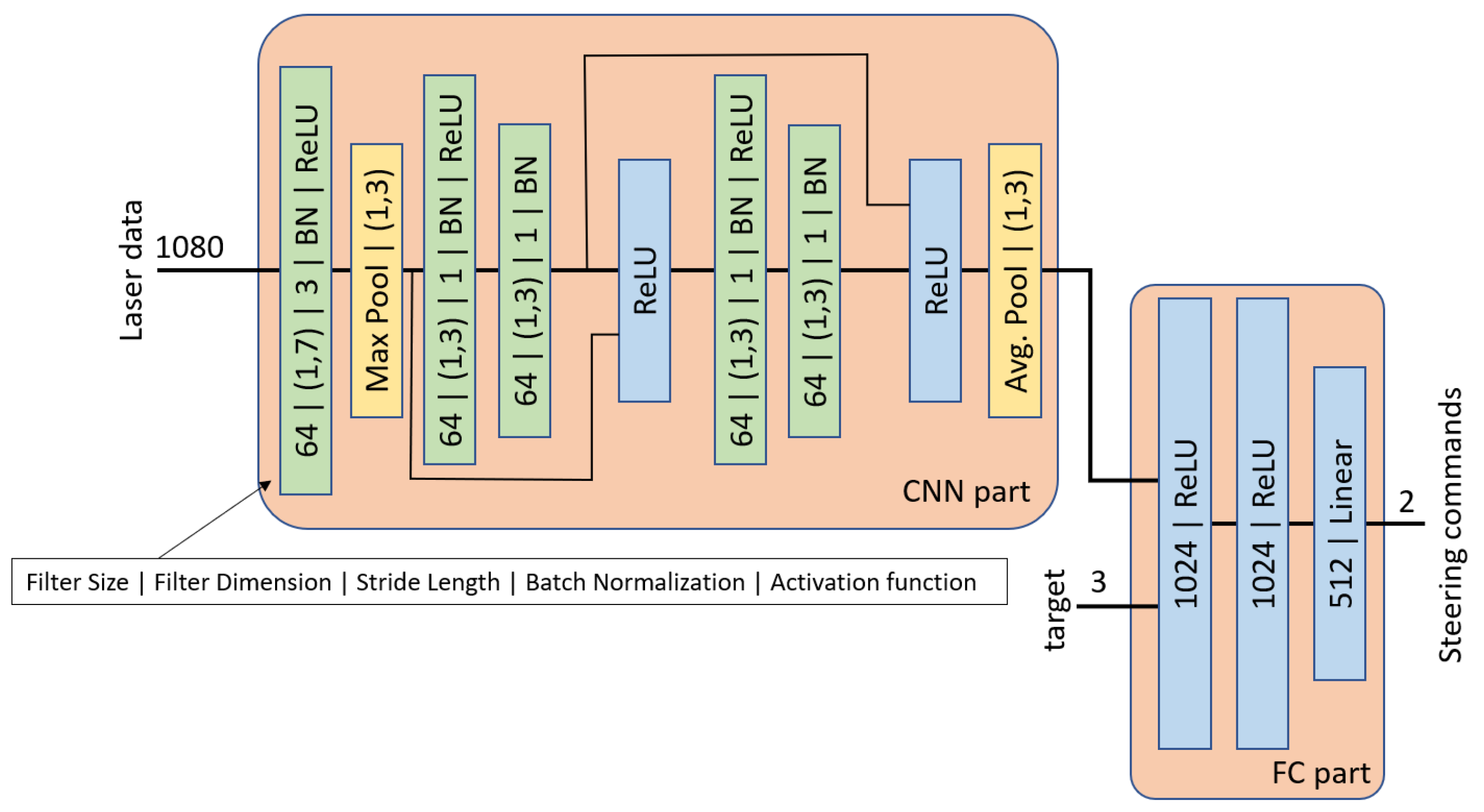

- Pfeiffer, M.; Schaeuble, M.; Nieto, J.; Siegwart, R.; Cadena, C. From Perception to Decision: A Data-driven Approach to End-to-end Motion Planning for Autonomous Ground Robots. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Piscataway, NJ, USA, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 1527–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, M.; Shukla, S.; Turchetta, M.; Cadena, C.; Krause, A.; Siegwart, R.; Nieto, J. Reinforced Imitation: Sample Efficient Deep Reinforcement Learning for Mapless Navigation by Leveraging Prior Demonstrations. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 4423–4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, L.; Paolo, G.; Liu, M. Virtual-to-real deep reinforcement learning: Continuous control of mobile robots for mapless navigation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; pp. 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Barham, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; Ghemawat, S.; Irving, G.; Isard, M.; et al. TensorFlow: A system for large-scale machine learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.08695. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Held, D.; Tamar, A.; Abbeel, P. Constrained Policy Optimization. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; Volume 70, pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, T.; Cheng, X.; Pan, J.; Manocha, D.; Yang, R. CrowdMove: Autonomous Mapless Navigation in Crowded Scenarios. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.07870. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Hsu, D.; Lee, W.S.; Shen, S.; Subramanian, K. Intention-Net: Integrating Planning and Deep Learning for Goal-Directed Autonomous Navigation. In Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning, Mountain View, CA, USA, 13–15 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pokle, A.; Martín-Martín, R.; Goebel, P.; Chow, V.; Ewald, H.M.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Sadeghian, A.; Sadigh, D.; Savarese, S.; et al. Deep Local Trajectory Replanning and Control for Robot Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 5815–5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-D’Arpino, C.; Liu, C.; Goebel, P.; Martín-Martín, R.; Savarese, S. Robot Navigation in Constrained Pedestrian Environments using Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Dance, C.; Kim, J.E.; Park, K.S.; Han, J.; Seo, J.; Kim, M. Fast Adaptation of Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Navigation Skills to Human Preference. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 30 May–4 June 2020; pp. 3363–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghi, B.H.; Dudek, G. Sample Efficient Social Navigation Using Inverse Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.10318. [Google Scholar]

- Ziebart, B.D.; Maas, A.L.; Bagnell, J.A.; Dey, A.K. Maximum Entropy Inverse Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Chicago, IL, USA, 13–17 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Higueras, N.; Ramón-Vigo, R.; Caballero, F.; Merino, L. Robot local navigation with learned social cost functions. In Proceedings of the 2014 11th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics (ICINCO), Vienna, Austria, 1–3 September 2014; Volume 2, pp. 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerkey, B.; Konolige, K. Planning and control in unstructured terrain. In Proceedings of the ICRA Workshop on Path Planning on Costmaps, Pasadena, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez, D.; Okal, B.; Arras, K.O. Inverse Reinforcement Learning algorithms and features for robot navigation in crowds: An experimental comparison. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014; pp. 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmar, H.; Spies, M.; Sprunk, C.; Burgard, W. Socially compliant mobile robot navigation via inverse reinforcement learning. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2016, 35, 1289–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

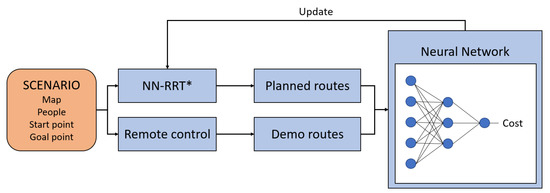

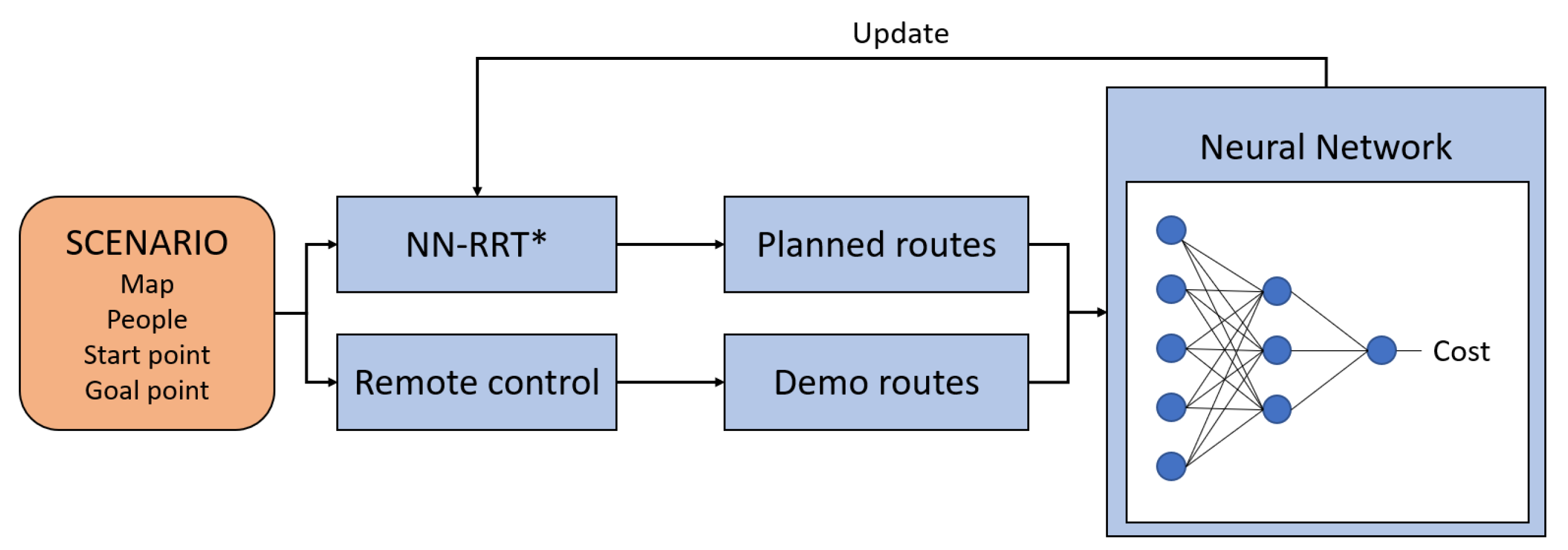

- Wang, Y.; Kong, Y.; Ding, Z.; Chi, W.; Sun, L. NRTIRL Based NN-RRT* Path Planner in Human-Robot Interaction Environment. In Proceedings of the Social Robotics, Florence, Italy, 13–16 December 2022; Cavallo, F., Cabibihan, J.J., Fiorini, L., Sorrentino, A., He, H., Liu, X., Matsumoto, Y., Ge, S.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 496–508. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, D.; Amir, E. Bayesian Inverse Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 20th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Hyderabad, India, 6–12 January 2007; pp. 2586–2591. [Google Scholar]

- Okal, B.; Arras, K.O. Learning socially normative robot navigation behaviors with Bayesian inverse reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Stockholm, Sweden, 6–21 May 2016; pp. 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugas, D.; Nieto, J.; Siegwart, R.; Chung, J.J. IAN: Multi-Behavior Navigation Planning for Robots in Real, Crowded Environments. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 October 2020–24 January 2021; pp. 11368–11375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Magro, A.; Gondkar, R.; Manso, L.; Núñez, P. Towards efficient human–robot cooperation for socially-aware robot navigation in human-populated environments: The SNAPE framework. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 3169–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Song, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Hu, Y.; Liu, S.B.; Zhang, J. Robot Navigation Based on Human Trajectory Prediction and Multiple Travel Modes. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, R.S.D.; Romero-Garcés, A.; Marfil, R.; Vicente-Chicote, C.; Cruz, J.M.; Inglés-Romero, J.F.; Bandera, A. QoS Metrics-in-the-Loop for Better Robot Navigation. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Proceedings of the WAF, Alcala de Henares, Spain, 19–20 November 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 1285, pp. 94–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bozhinoski, D.; Wijkhuizen, J. Context-based navigation for ground mobile robot in semi-structured indoor environment. In Proceedings of the 2021 Fifth IEEE International Conference on Robotic Computing (IRC), Taichung, Taiwan, 15–17 November 2021; pp. 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, P.; Manso, L.J.; Bandera, A.; Rubio, J.P.B.; García-Varea, I.; Martínez-Gómez, J. The CORTEX cognitive robotics architecture: Use cases. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2019, 55, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfil, R.; Romero-Garcés, A.; Rubio, J.P.B.; Manso, L.J.; Calderita, L.V.; Bustos, P.; Bandera, A.; García-Polo, J.; Fernández, F.; Voilmy, D. Perceptions or Actions? Grounding How Agents Interact within a Software Architecture for Cognitive Robotics. Cogn. Comput. 2020, 12, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luber, M.; Tipaldi, G.D.; Arras, K. Better models for people tracking. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).