Abstract

Natural disasters, such as wildfires, can cause widespread devastation. Future-proofing infrastructure, such as buildings and bridges, through technological advancements is crucial to minimize their impact. Fires in disasters often stem from damaged fuel lines and electrical equipment, such as the 2018 California wildfire caused by a power line fault. To enhance safety, IoT applications can continuously monitor the health of emergency personnel. Using Bluetooth 5.0 and wearables in mesh networks, these apps can alert others about an individual’s location during emergencies. However, fire can disrupt wireless networks. This study assesses Bluetooth 5.0’s performance in transmitting signals in fire conditions. It examined received signal strength indicator (RSSI) values in a front open-fire chamber using both Peer-to-Peer (P2P) and mesh networks. The experiment considered three transmission heights of 0.61, 1.22, and 1.83 m and two distances of 11.13 m and 1.52 m. The study demonstrated successful signal transmission with a maximum loss of only 2 dB when transmitting through the fire. This research underscores the potential for reliable communication in fire-prone environments, improving safety during natural disasters.

1. Introduction

In the critical realm of emergency response, the combination of Internet of Things (IoT) and wireless communication technologies has emerged as a vital asset, fundamentally reshaping crisis management. The precise knowledge of individuals’ whereabouts within a building carries significant value for various applications, particularly in enhancing the planning and response strategies of first responders and emergency personnel. One method for gathering this information entails the use of Bluetooth Low-Energy (BLE) applications, which have been employed in a variety of building-related contexts, such as indoor navigation [1] and activity recognition [2], providing crucial insights through motion detection.

Regarding indoor localization and occupancy estimations, diverse approaches cater to specific area types. In [3], the authors present a system that relies on iBeacons to ascertain building occupancy and predict the presence of a user inside or outside a particular room.

Alternatively, through Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) solutions, it is also possible to track the condition of individuals affected by fire-based disasters via remote monitoring of health bio signs. Health bio signs to be monitored may include galvanic skin response, heart rate, and blood pressure [4]. Monitoring enables risk assessment and intervention, thereby providing a means of potentially reducing casualties [5]. IoMT applications are typically concerned with tracking a users’ state of health to monitor wellbeing [6,7] and quantify progression of an illness [8]. Moreover, continuous monitoring and reporting of a user’s vital signs, such as heart rate, temperature, and respiration, can unveil potential health risks by identifying otherwise unnoticed irregularities. This, in effect, enables the detection of undiagnosed medical conditions, which could otherwise be missed [9].

Monitoring bio signs could, therefore, be used to assess the current state of health of the associated emergency rescue service members as a means of ensuring their safety. Additionally, these data could be used to alert team members when a squad member is at risk, allowing for immediate action to be taken. This is especially important within an environment that is engulfed by a fire, representing a large risk to life.

In addition to risks presented by typical fires, natural disasters present a high-risk scenario for emergency workers. Risks may include being trapped or seriously injured by debris, as well as respiratory and asthmatic problems [10]. These scenarios can also introduce several challenges to communication, as different environmental factors can affect radiofrequency (RF) propagation, which can reduce the useful range of the radio transmissions. Outdoor and rural environments can introduce free-space loss and foliage attenuation [11], whereas indoor and urban environments can introduce scattering, reflection, and material penetration loss [12]. These losses are then enhanced by surrounding debris, which can further affect the indoor–outdoor communication link performance between users.

Compounding these directly presented challenges, natural disasters increase the potential for auxiliary fires to occur. Specifically, these auxiliary fires may occur indirectly from damaged fuel lines and electrical and chemical equipment. This can create devastating fires that engulf everything around them, such as the 2018 California wildfire caused by a power transmission line fault [13].

The users’ vital signs readings are obtained via optical, or electrocardiogram sensors attached to the user and then transmitted wirelessly via various RF technologies. Different bands of the RF spectrum, e.g., sub-GHz, microwave, and millimeter wave, offer different transmission ranges, data rates, and power consumption. Due to these differences, certain radio technologies are more suitable than others depending on the overall application requirements.

Additionally, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have been deployed for assisting in emergency relief. Some are applied by bridging connections via UAV base stations, delivery of supplies via payloads, and recording environmental data for hazard monitoring [14,15]. However, not all wireless networks are suitable for every natural disaster since RF propagation can be affected by environmental changes, such as those related to temperature, humidity, wind speed, and precipitation [16].

The environmental effects of fire present a particularly difficult set of challenges for radio communications technology. These challenges include damage to existing infrastructure, e.g., wireless routers. Additionally, fire attenuation via ionized particles, particulate matter (PM), and changes to the surrounding air’s refractive index can be introduced.

This article is dedicated to the comprehensive evaluation of BLE 5.0 as a viable solution for implementing health-tracking systems in fire-related environments. Our analysis, starting with Section 2 below, investigates the attenuation factors specific to fire conditions, shedding light on their potential impact on wireless communication systems. We then explore the capabilities and overall suitability of BLE 5.0 in emergency response situations in Section 3.

Subsequently, Section 4 outlines the test scenarios, and in Section 5, we present an in-depth analysis of the results. Finally, we present our conclusions, reflecting on the findings, and propose further testing to gain deeper insights into the technology’s functionality within these critical scenarios.

2. Related Work

In emergency response scenarios, the reliability of wireless communication can be a matter of life and death, as it directly impacts the system’s performance, especially if used for applications involving health sign monitoring and/or asset tracking of individuals. Any form of fire can cause signal attenuation on wireless communication due to the direct characteristics and influence on environmental variables. Heat generated and exerted from fires can reduce the surrounding humidity levels while also raising the surrounding temperature. This can create air updrafts from the source, as the surrounding air molecules become lighter and less dense while being more energized by the flame, which in turn influences the airflow. The greater the airflow, the more available oxygen molecules can be introduced into the combustion reaction of the flame, thus prolonging the reaction (assuming combustible material is still available) and increasing the overall temperature.

The surrounding atmosphere’s refractive index is influenced by this phenomenon, resulting in the occurrence of sub-refraction. This effect arises due to alterations in atmospheric temperature and gas composition. The primary cause is the reduction in air density, which leads to less bending of the signal path compared to the norm. Consequently, higher temperatures prompt a decrease in the refractive index.

This alteration has a more pronounced impact, as the signal distance increases, particularly when employing directional antennas. This could potentially cause a deviation from the straight pathway of the RSSI signal in large-scale environments, such as brush fires, but will have minimal impact on smaller indoor fires. Since the base is the hottest region of the flame (as hot air rises, which causes it to cool), the refractive index will increase with height, eventually reaching normal conditions [17]. Therefore, depending on where the signal is penetrating the flame, the change in temperature can influence its overall performance.

The temperature generated does, however, generally rely on the fuel source, as different compounds burn at different levels due to their chemical and molecular structure. Additionally, the combustion sources impact on the quantity and composition of atmospheric smoke. Atmospheric smoke has been shown [18] to increase radiofrequency (RF) signal attenuation. Therefore, this reinforces the impact of the material source on the attenuation effect from the fire, as some materials generate more atmospheric smoke than others.

In addition to Class A fires involving solid materials, they are also more likely to generate a higher concentration of airborne debris compared to other types, such as chemical and electrical fires. This is because the materials that burn turn into ash, which becomes airborne due to the updraft created by the temperature difference between the fire and the surrounding air. Consequently, this can lead to the absorption of electromagnetic waves [19]. The presence of particulate matter causes scattering of the radio waves, leading to signal attenuation. Moreover, the random orientation of the particles results in highly variable levels of attenuation.

However, fires of Classes B and C, which include flammable liquids and gases, result in minimal particulate matter (PM) generation. Nevertheless, they possess the capacity to modify the composition of the surrounding air, thereby impacting its dielectric constant. This alteration has been shown to affect the refractive index of the surrounding air by producing elevated levels of atmospheric elements, as evidenced in [20]. The specific elements generated depend on the combustion source, such as petroleum, ethanol, kerosene, and similar substances.

The general performance of the system is determined by its associated received signal strength indicator (RSSI) of the transmitted signal. The RSSI is part of the data packet transmitted, intended to obtain a relative indication of the quality of the current connection that exists between the transmitter and receiver. The RSSI ranges are −40 dB or less is exceptionally good, −50 to −70 dB is considered good, and anything more than −80 dB is considered intermittent, with the possibility of zero operation [21].

Therefore, this interference can cause issues for communication using the 2.4 GHz Industrial Scientific and Medical (ISM) band, as illustrated in [22]. The study primarily focuses on the flame height and distance of a fire fueled by liquefied petroleum (LP) gas to generate a small fire radius of 10 cm between the propagation path of two Imotes2 nodes. The first node was set at a fixed distance of 0.2 m from the fire column, acting as the receiver, while the second node was placed at varying distances with respect to the fire column. These values ranged from 0.2 to 2 m, with an incremental increase of 0.2 m for each reading [23].

This work determined a linear deterioration of signal transmission, as indicated by a reduction of RSSI of up to 3.2 dBm between the presence of a fire of 10 cm in height and when no fire is present. The fire’s impact on radio transmission is greater the closer the transmission proximity is to the fire, thus highlighting how the fire primarily affects signals’ performance within its surrounding environment.

Additionally, when the temperature of these gases reaches a high enough temperature, the electrons overcome their atomic binding energy, thus becoming separated from their atoms. This causes the gas mixture to contain freely moving electrons and nuclei, generating ionized plasma, which results in dispersion and attenuation of the interacting electromagnetic waves [24].

This was demonstrated in [25], in which Pinus Caribea (pine) litter was used as the fuel source to investigate the effect brought on by an ionized medium. While the ionized medium generated is weak, it is most likely to be present within forest fires or located in house fires as furniture. When transmitting between 8 and 10.5 GHz, this resulted in a loss of 1.6–5.8 dB. There was a similar attenuation rate observed in [22]; however, the attenuation was initially 6 dB, but eventually decreased to around 2 dB. This is primarily due to the concentration of the ionized particles having a linear relationship with the combustion rate of the fire. Therefore, as the rate of combustion increases or decreases, so does the creation of ionized particles. Hence, the attenuation effect of the fire can fluctuate throughout the combustion process, as shown in [22].

Since plasma-based attenuation is dependent on the material burnt, it further emphasizes the crucial role of the fuel source on the attenuation capabilities of a related fire. Additionally, it also highlights that certain levels of attenuation generated by the fire may be reduced over time. This is due to an inconsistent concentration of ionized particles throughout the whole combustion process. However, signal attenuation will still be present while the fire is still active in some form.

This shows that fire does have a significant effect on the 2.4 GHz ISM band, revealing that both the signal strength and link quality parameters are further dependent on the dimensions of the fire column, and the link performance could become severely impacted under extreme fire conditions, such as those produced by bushfires. This, therefore, can affect most commercial communication links within the indoor fire environment, regardless of any damage to the communication relay device, e.g., the router, which would conventionally be used to transmit and receive the average users’ vital health data via smart medical devices.

Currently, within the Fire Emergency Services, their main form of communication is via two-way, handheld ultra-high-frequency (UHF) portable radio systems that operate between 450 and 470 MHz, enabling communication between squad members [26]. However, as shown in [24], this frequency is subjectable to the fire’s attenuation, which can result in a RSSI loss of up to 8 dBm.

Moreover, the information transmitted by these systems is exclusively in audio form. This heightens the potential for human error, as there is a risk of misinterpreting one’s situation, particularly during high-stress flight or fight scenarios. Fire attenuation has also been shown to affect the whole LPWAN sub-GHz spectrum, as demonstrated in [24]. Normally, these frequencies are considered more resilient to environmental depletion factors, such as material penetration loss [27]. This generally makes them an ideal alternative to standard Wi-Fi for long-range indoor–outdoor communication due to their longer wavelengths. However, in this case, the fire attenuation makes their performance subjectively worse.

Sometimes, this can be countered by adding a message-repeating infrastructure, which relays the information while amplifying the signal’s strength. This can cause numerous issues, such as higher power consumption within these scenarios or a decrease in the signal to noise ratio (SNR) in the transmitter, which can render the received information incomprehensible. Therefore, it is more than likely that any communication links between the individuals are expected to be ineffective due to the amount of attenuation directly generated by a fire. This is especially true at times when an individual is closest to the source of the fire, where data communication could be compromised. This is crucial when effective communication can be key for survival [28].

As previously described, the performance of these communication methods can be heavily influenced by the conditions of the surrounding environment when any form of fire is present. This can render them unreliable as a means of establishing a consistent and reliable communication network for the monitoring of users’ vital health data.

Due to these reasons, a fire-resilient communication network is required for deployment within any scenarios in which a fire may occur, if not initially involved. This, however, can be difficult, since one characteristic can influence another, and no two fires are the same; therefore, the major variables involved are hard to account for. To counter this, there needs to be a system that can counteract/resist the attenuation effects introduced by fires to establish a reliable, consistent connection, allowing for accurate data transmission and reception. It is known that operation of Wi-Fi and LPWAN can become greatly impaired and dysfunctional due to a RSSI reduction, which can cause gaps in data transmission.

Furthermore, as emphasized in [29], 5G is notably more susceptible to attenuation factors such as rain due to its use of the millimeter-wave spectrum, characterized by shorter wavelengths and higher frequencies. This susceptibility raises concerns about its suitability in demanding environments, a perspective reaffirmed in [30]. This is primarily due to 5G operating in the millimeter-wave spectrum (above 6 GHz), which allows for faster speeds, increased range, and higher data capacity.

However, these benefits are only possible due to the shorter wavelengths associated with these frequencies. This is especially true for the case of indoor fires due to material penetration loss, as it has been shown [31] that millimeter waves displayed a mean excess loss of 10.6 dB for the single-family unit and 22.7 dB for the multi-story brick building. In [32], no signal was detected through brick pillars throughout the millimeter-wave bands yet signals through hollow plasterboard wall resulted in a penetration loss ranging between 5.4 and 8.1 dBm. In [33], researchers measured penetration losses of 2 dB, 9 dB, and 35.5 dB at 60 GHz through a glass door, plasterboard with metallic studs, and a wall with a metal-backed blackboard, respectively.

To counter this, signals are usually sent through glass, as it offers better signal performance. However, it was shown in [34] that while transmitting the signal through a plain glass wall presented virtually no loss, the penetration loss increased by 25 dB to 50 dB when the glass surface was metal-coated [34]. This is important to note, as modern-day glass windows, primarily used within construction of dwellings, are routinely infused, or coated with metal substrates to block harmful ultraviolet rays, while also improving the thermal insulation properties [35].

While the above provides an understanding of the effect in certain materials, it covers only a handful. This, therefore, leaves room for further testing as a means of obtaining a full understanding of 5G building material penetration loss before it can be relied on for health tracking within emergency response situations.

As mentioned earlier, contemporary communication technologies often prove inadequate for this application, primarily due to their vulnerability to fire-induced signal attenuation. This susceptibility can result in loss of critical data or even complete disconnection between these systems. Hence, there is a pressing need to investigate the potential impact of fire-induced signal attenuation on the effectiveness of resilient communication technologies such as BLE 5.0, as outlined in the following section.

3. Bluetooth 5.0 Communication Link

Bluetooth operates on the same frequency as standard 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi, which has been shown to be the more resilient frequency regarding fire attenuation, as opposed to sub-GHz and the millimeter spectrum. In addition, it also operates on a different protocol stack, which makes it more resilient to attenuation [36]. This resilience is achieved through advanced communication schemes and improving the signal transmission efficiency [37]. Notably, this protocol has been developed by the Bluetooth Special Interest Group (SIG) specifically for establishing resilient short-range communication, which has been progressively upgraded to accommodate longer distances while remaining robust [38]. This is primarily achieved by having a Bluetooth device operate on a lower bandwidth, which uses a scattered ad-hoc topology connection. This makes up a Piconet when transmitting or receiving data within the established network.

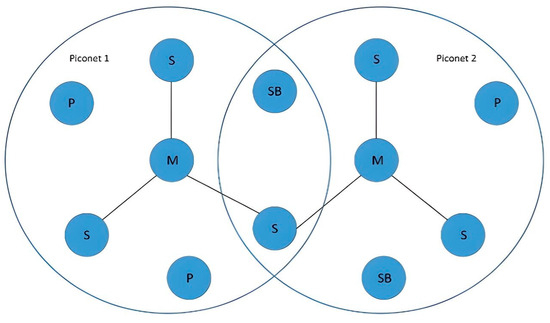

The system is comprised of four states: master, slave, standby, and parked. For data communication, the master state manages the data transmission, while the slave manages the reception of data within the system. For connection, standby devices wait to join the Piconet later while retaining its MAC address, whereas parked devices wait to adhere to the Piconet later and release its MAC address. These states allow the network to expand and transmit data while leveraging neighboring networks. This is presented in Figure 1, which depicts two Piconets forming a mesh network.

Figure 1.

Bluetooth ad-hoc Piconet topology illustration.

This meshing capability enables devices within the network to interact with one another without the need for any dedicated access points or wired connections. This can compensate for the reduced communication range provided by Bluetooth, as opposed to Wi-Fi. Additionally, this meshing can enable any system to become more resilient to environmental depletion factors. This is because additional paths for the signal are generated by establishing a many-to-many mesh network, as the devices can switch roles from master to slave, and vice versa.

In environments that have a fire occur, communication to and from one node may be distorted to the extent that communication is no longer viable. However, in the presence of a mesh network, the signal is not completely lost. Instead, the message can still be received by neighboring devices, which can then route the message around the fire through the most optimal path, with minimal interference [39].

In terms of energy consumption, these devices consume very little power, enabling them to operate over long periods of time without requiring charging and/or battery replacement. This makes devices that incorporate this technology viable for long-term use, often over a series of weeks, months, or even years depending on the battery source [40]. This long battery life favorably compares to the UHF radios currently used by fire services, which only have a charge capacity of approximately 12 h between charges [41].

In addition, Bluetooth 5.0 offers up to 2 Mbps of bandwidth with a message capacity of 255 bytes per payload [42]. This bandwidth enables a considerable amount of data to be transmitted via sensors, which can provide a more detailed evaluation of the user’s state and the environmental condition where they are located.

These factors are beneficial, as the low power consumption of most standard Bluetooth modules makes them ideal for implementation into a UAV for a mobile aerial node. This would enable wider coverage and adaptability, as they can position themselves in the most efficient location, thus reducing signal communication loss via environmental depletion factors, such as material penetration and free-space loss. Additionally, it allows for data to be collected and relayed at safe distances, ensuring the integrity of the devices.

Since these devices are unmanned, they can be positioned in a way that allows for wider and more diverse coverage in areas deemed unsuitable or unreachable for human personnel. Mass deployment could also be used to enable this, as each UAV added into a solution may increase the number of available communication pathways. Additionally, increasing the number of devices connected in the network allows for incorporation of proximity tracking of individuals and solution elements via the RSSI of the user’s Bluetooth 5.0 module in relation to surrounding nodes. This could be implemented by having the UAVs form a grid system, which in turn could be used to determine the approximate location of the users’ positioning by ascertaining their associated received signal strength indicator (RSSI) value and determining which nodes are closest to it.

This is especially beneficial since Global Positioning System (GPS) location-tracking systems can be affected by a building structure, as some buildings have so many incorporated metal structures and supports that they can, effectively, become a faraday cage, which degrades the location accuracy by introducing GPS drift or a complete loss of signal. Therefore, these Bluetooth modules can be implemented to act as a secondary location tracker of both potential victims and rescue response personnel, while still relaying the users’ health data.

This becomes useful in emergency response scenarios, such as a burning building complex, where GPS performance can be affected by the building’s metal structures. This can result in inaccurate or complete loss of remote location-tracking capabilities. Therefore, this secondary system could help provide relative information on users’ locations in relation to other members’ RSSI levels and surrounding nodes. This additionally comes in handy for locating downed teammates in areas of low vision due to high concentrations of smoke.

It is, therefore, apparent that Bluetooth 5.0 has several advantages that could augment communication between emergency services personnel and their support teams. However, to date, there has been no evaluation of the performance of BT 5.0 signals in the presence of fire. To determine if this communication technology is appropriate for the application, it must first be evaluated in a real-world scenario.

4. Experimental Scenario

4.1. Experimental Setup

Before adoption of Bluetooth 5.0 as the communication medium for an emergency personnel protection platform, its effectiveness first needs to be evaluated. Specifically, data transmission must be evaluated through a fire source and in the proximity of a fire source.

To investigate this, a series of “nodes”, consisting of Adafruit Feather nRF52 Bluefruit LE microcontroller boards featuring the Nordic nRF52832 Bluetooth 5.0 Low-Energy module, were selected. This module communicates with a 2.4 GHz radio in a manner that offers up to +4 dBm output power, operating with an ARM Cortex M4F CPU running at 64 MHz [43]. These boards were manufactured by Adafruit Industries LLC, based in New York, United States and purchased through Pimoroni Ltd based in Sheffield, Yorkshire, UK.

A fire was lit within a front open-fire chamber consisting of length 1.7 m, width 2.39 m, and height 2.39 m, with a layer of insulating mineral slurry. The fuel source was crib wood, generating a thermal energy of 3 megawatts, which burned at approximately 600 °C (1112 °F) at its peak, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Fire chamber and crib wood after ignition.

In each transmission, the received signal strength indicator (RSSI) of every device was recorded, and the successful reception of messages was verified. To ensure the accuracy of our experiments, the nodes were stationed in a fixed position to minimize potential signal variations caused by movement. This approach allowed us to specifically focus on assessing the attenuation effects originating from the fire source.

The nodes were strategically positioned on either side of a semi-enclosed fire chamber within a dedicated fire evaluation site, as illustrated in Figure 2. This specialized site, authorized for controlled combustion experiments, serves as a regulated environment for evaluating various aspects of combustion and the impacts. The nodes were employed to transmit and receive a predefined message, simulating real-world heart rate data with a rate of 70 beats per second (bps).

Network Topologies

Two sets of network topologies were used during the experiments. The Peer-to-Peer (P2P) system was used to evaluate the attenuation effect of the fire and penetration of the back wall. Then, the mesh system was used, consisting of three nodes to divert the signal around the fire and a fire chamber as a means of investigating any performance improvement when diverting the signal around these depleting elements.

4.2. Experimental Procedure

During the procedure, the transmitter module (Node 1) was handheld to simulate close-contact proximity with the user to further help mimic a real-life deployment scenario. Both the bridging module (Node 2) and the receiver module (Node 3) where attached to a tripod during each test setup, as demonstrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Node attached to a tripod.

With the average height of men being 1.71 m and women being 1.6 m [44], a deployment height of 1.22 m was chosen as a means of mimicking the average chest height. This is where the wearable Bluetooth module would ideally be placed in relation to the user to reduce impacts on the device or user performance. Cardiac and respiratory data can then be obtained via electrocardiogram (ECG) sensors.

A deployment height of 0.61 m was used to mimic a casualty on the ground in the event they are unconscious or unable to stand. Then, 1.83 m was used to evaluate the suitability of a wearable device being incorporated into headgear for increased data collection regarding environmental conditions, such as gas and temperature readings.

The receivers were then placed at fixed heights of 1.22 m to determine the performance with a clear P2P transmission, as well as being a good medium between both the 0.61 m and 1.83 m test measurements.

4.2.1. Experiment 1

Experiment 1 was conducted within the indoor evaluation environment without an active fire present. This was to determine the base RSSI value to provide a comparative baseline. Additionally, this would capture any effect the controlled fire evaluation structure may have on the signal’s performance.

During both Experiment 1 P2P setups, Node 1 acted as the transmitter while Node 3 acted as the receiver, obtaining the value of 70 bps and providing the RSSI value of Node 1’s transmission.

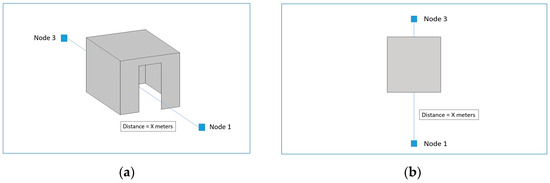

Node 1 was placed at 6.4 m and 7.92 m away from the front of the fire, while Node 3 was placed 2.77 m from the back of the fire chamber. This resulted in a total transmission distance of 10.82 m and 12.34 m, respectively, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

(a) Indoor P2P node positioning (3D) in Experiment 1. (b) Indoor P2P node positioning (2D) in Experiment 1.

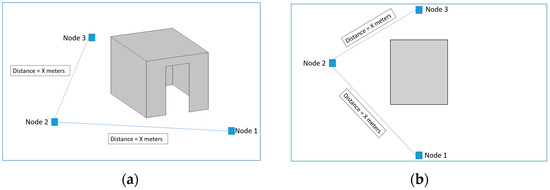

During the Experiment 1 mesh networking setup, Node 1 remained as the transmitter; however, it was directed to Node 2, which acted as a bridging module receiving the message from Node 1 and relaying it to Node 3, which remained as the receiver, along with recording Node 1’s RSSI value.

Node 1 remained 7.92 m away from the front of the fire at heights of 0.61, 1.22, and 1.83 m, while Node 3 was placed 2.77 m from the back of the fire chamber. Node 2 was placed 5.28 m from Node 3 at a 45-degree angle of each board, which resulted in a transmission distance 10.82 m between Nodes 1 and 2, as illustrated in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5.

(a). Indoor mesh node positioning (3D) in Experiments 1 & 2. (b) Indoor mesh node positioning (2D) in Experiments 1 & 2.

4.2.2. Experiment 2

Experiment 2 was repeated in the same manner and conducted in the same location as Experiment 1. However, in this instance, a controlled fire was lit to determine any differences in the RSSI levels when the fire was present. These differences were used to analyze any effect that the fire may have on the Bluetooth 5.0-based communications.

4.2.3. Experiment 3

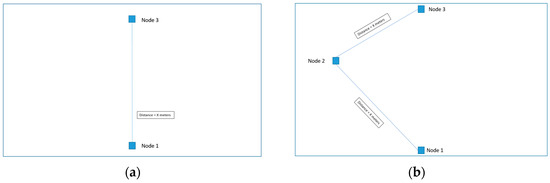

Experiment 3 took place outside in an open green area that was free of any obstruction. The testing was conducted in the same manner as Experiments 1 and 2, as illustrated in Figure 6, except for the fire chamber not being present. This experiment was performed as a means of identifying an average RSSI value without reflections or material penetration loss being present.

Figure 6.

(a). Outdoor P2P node positioning in Experiment 3. (b) Outdoor Mesh node positioning in Experiment 3.

Once the results were collected, they were then grouped and averaged across a 15 s interval for each of the three environmental conditions, along with the varying distances and heights. The results from these experiments are presented in the following section.

5. Experimental Findings

5.1. Experimental Results

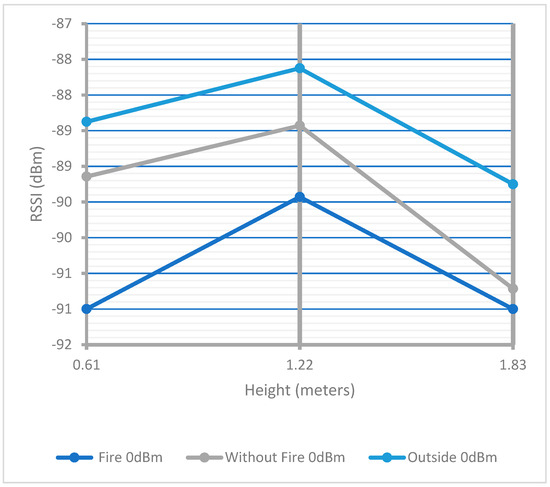

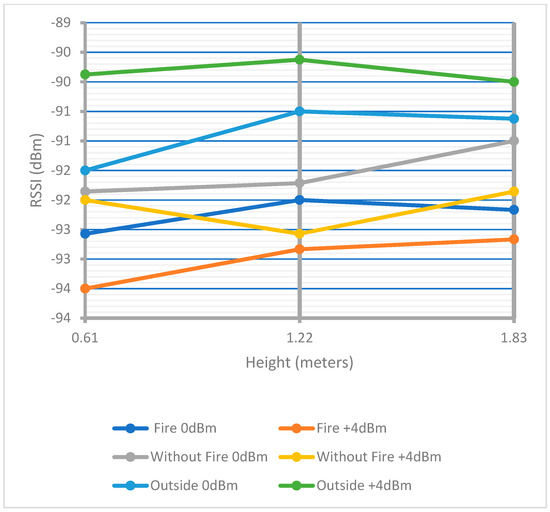

The results shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8 illustrate that the impact of a fire event on Bluetooth transmission exhibited minimal attenuation and environmental dependence. Specifically, the presence of the fire induced a marginal 2 dBm variance between Experiments 1 and 2. Concurrently, the environmental influence on signal performance produced a comparable 2 dBm disparity between Experiments 1 and 3.

Figure 7.

P2P topology of average RSSI across 10.82 m.

Figure 8.

P2P topology of average RSSI across 12.34 m.

Regarding spatial parameters, an increment of 1.52 m in height led to a maximal 2 dBm loss, while altering the height by ±0.61 m resulted in a maximum loss of 1 dBm. Furthermore, augmenting the transmission power by ±4 dBm yielded only negligible improvements. Notably, Experiment 3 demonstrated a maximum performance increase of 1.5 dBm, whereas Experiments 1 and 2 experienced a maximum decline of 1 dBm.

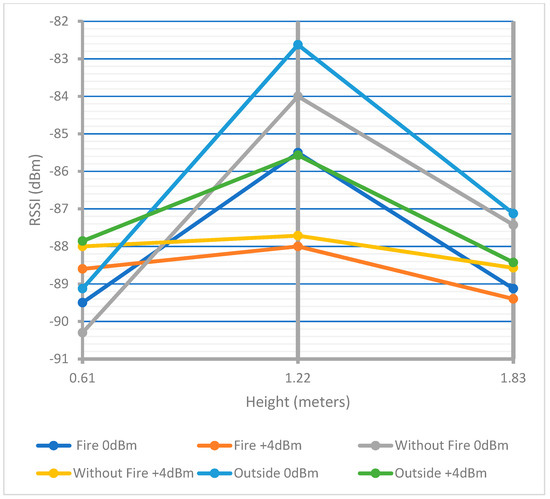

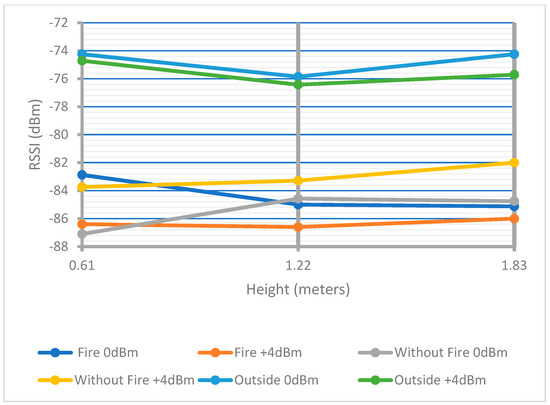

The establishment of a mesh network topology yielded an overall performance enhancement, evidenced by an increase of up to 5 dBm, as depicted in Figure 9 and Figure 10, in comparison to the P2P topology showcased in Figure 7 and Figure 8. Notably, the presence of fire exerted minimal impact on this topology, resulting in a mere 2 dBm decrease in overall performance. However, it is noteworthy that at 0.61 m, there was a discernible maximum increase of 1 dBm in transmission strength.

Figure 9.

Mesh topology of Node 1–Node 2 average RSSI across 12.34 m.

Figure 10.

Mesh topology of Node 2–Node 3 average RSSI across 12.34 m.

During Experiments 1 and 2, a fluctuation of approximately 1.5 dBm in signal performance between Nodes 2 and 3 was observed, despite their consistent maintenance of identical height, distance, and orientation throughout the experiment.

When the signal was amplified by ±4 dBm, it was observed to have an adverse effect on the transmission performance of the signals. This phenomenon manifested as a maximum decline of 3 dBm in Experiments 1, 2, and 3 across the heights of 1.22 and 1.83 m. Notably, when transmitting between Nodes 1 and 2 at a height of 0.61 m, there was a modest improvement of 0.5 dBm in performance.

In instances where transmission occurred between Nodes 2 and 3, which were in closer proximity to each other, this led to a maximum loss of up to 1 dBm in Experiments 1 and 2. However, Experiment 3 exhibited a maximum increase of 0.5 dBm under these conditions.

5.2. Discussion of Results

In summary, the presence of fire exhibited minimal influence on Bluetooth signal transmission performance, with the maximum attenuation observed at 2 dBm for both P2P and mesh network topologies. Notably, the 1.22 m height configuration yielded the most optimal performance among the three tested heights, primarily owing to the omnidirectional characteristic of the devices employed.

The omnidirectional emission of signals, radiating in all directions rather than being focused on a specific point of the antenna, caused radio waves to interact with surfaces, leading to either their successful reception or a depletion in signal power. Consequently, the 0.61 m height configuration demonstrated inferior performance due to increased signal reflection off the ground, resulting in reduced power.

In contrast, the 1.83 m height configuration transmitted most signals over the 1.22 m reception radius, establishing a clear and efficient line of sight. This also clarifies why Experiments 1 and 2 experienced more adverse effects compared to Experiment 3, as the environment introduced greater potential for signal reflections.

Regarding the reduction in RSSI when enhancing the signal by ±4 dBm, this effect may be attributed to the increased signal resilience against the damping impact of reflections, enabling stronger signals to reach their intended destinations compared to their weaker counterparts.

Furthermore, the amplified signal’s impact on transmission between Nodes 2 and 3 was more pronounced due to their proximity. While signal amplification enhances transmission power, excessive proximity can introduce distortion into the system by generating additional noise, primarily attributable to reception sensitivity. This is why signal amplification is typically implemented to counter specific signal distortions, such as free-space loss or signal penetration, when necessary.

In the broader context, the mesh network demonstrated superior performance compared to the P2P topology, primarily attributed to the reduced distance between the three nodes and the avoidance of the back wall of the fire chamber. This strategic placement effectively circumvented material penetration loss, resulting in stronger RSSI values.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Bluetooth 5.0 has demonstrated its operational capability near fire, both through mesh networking and when the signal must penetrate the fire itself using Peer-to-Peer (P2P) transmission, owing to its low susceptibility to attenuation during experimental testing. Consequently, this wireless communication network emerges as an optimal choice for establishing a dependable system for monitoring the health of emergency rescue personnel, particularly in environments where fires are either prevalent or pose a potential threat during emergency response scenarios.

Furthermore, Bluetooth 5.0 offers substantial advantages over other conventional wireless networks and communication systems presently employed in emergency response services, particularly when implemented via mesh networking. The synchronization of mesh communication allows for the concurrent use of multiple data sources, facilitating more comprehensive monitoring of rescue personnel across extensive disaster areas. Additionally, it introduces a self-healing feature to the overall system, enabling signal rerouting along alternative pathways in the event of a node’s incapacitation.

The experimental assessment of various heights and distances revealed minimal variations in signal performance with respect to the transmitter height. Consequently, there is an opportunity to incorporate these devices into headgear, enabling the collection of additional environmental data, such as gas and temperature. This capability permits a more accurate assessment of the conditions in which the rescue team operates, allowing for timely identification of situations requiring heightened caution.

While the tests conducted have demonstrated promising results in achieving effective data communication through both P2P and mesh network topologies, there remain numerous unexplored factors that require further investigation to comprehensively assess the performance of Bluetooth in challenging environments. Future research efforts will involve the implementation of location tracking using the received signal strength indicator (RSSI) in relation to neighboring nodes. This will serve as a supplementary location-tracking method, particularly in scenarios where GPS tracking is either impractical or imprecise, such as indoor environments.

Additionally, considering that predetermined values were used in the current setup, it is imperative to conduct further testing to gather real-world user data, ensuring that the system can provide accurate results when sensors are positioned in proximity to sources of fire.

Furthermore, an upcoming study will explore the potential integration of this setup into Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to establish aerial-based nodes. This investigation will necessitate the exploration of additional variables, including antenna orientation and potential interference arising from the UAV’s relay antenna used for communication with its operator. Moreover, the incorporation of UAVs will offer insight into any potential effects that may arise when these nodes are mobile in a controlled manner.

Author Contributions

Investigation, B.B.; Resources, M.M.; Data curation, B.B.; Writing—original draft, B.B.; Writing—review & editing, B.B., J.R., J.S., A.E., M.M. and P.P.; Supervision, J.R., J.S. and A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data reported here was captured using the experimental setup mentioned in the study. Data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ulster University FireSERT for their help in the construction of the fire chamber used for the collection of results for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Fujihara, A.; Yanagizawa, T. Proposing an extended ibeacon system for indoor route guidance. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Intelligent Networking and Collaborative Systems (INCOS), Taipei, China, 2–4 September 2015; pp. 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.A.U.; Pathak, N.; Roy, N. Mobeacon: An ibeacon-assisted smartphone-based real time activity recognition framework. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Systems: Computing, Networking and Services, Coimbra, Portugal, 22–24 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Corna, A.; Fontana, L.; Nacci, A.A.; Sciuto, D. Occupancy detection via ibeacon on android devices for smart building management. In Proceedings of the 2015 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition, Grenoble, France, 9–13 March 2015; pp. 629–632. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kwon, S.; Seo, S. Kwangsuk Park Highly wearable galvanic skin response sensor using flexible and conductive polymer foam. In Proceedings of the 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–30 August 2014; pp. 6631–6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edoh, T. Internet of Things in Emergency Medical Care and Services. In Medical Internet of Things (m-IoT)—Enabling Technologies and Emerging Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanphaisarn, W.; Roeksabutr, A.; Wardkein, P.; Koseeyaporn, J.; Yupapin, P. Heart detection and diagnosis based on ECG and EPCG relationships. Med. Devices 2011, 4, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Quinn, S.; Bond, R.; Nugent, C. A two-staged approach to developing and evaluating an ontology for delivering personalized education to diabetic patients. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2017, 43, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, A.L.; Brooks, E. An Internet of things resource for rehabilitation. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Collaboration Technologies and Systems (CTS), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 19–23 May 2014; pp. 461–467. [Google Scholar]

- Banka, S.; Madan, I.; Saranya, S.S. Smart Healthcare Monitoring using IoT. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2018, 13, 11984–11989. [Google Scholar]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work; Milczarek, M.; Hauke, A.; Pinotsi, D.; Georgiadou, P.; Kallio, H. Emergency Services: A Literature Review on Occupational Safety and Health Risks; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2011; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2802/54768 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Meng, Y.S.; Lee, Y.H. Investigations of foliage effect on modern wireless communication systems: A review. Prog. Electromagn. Res. 2010, 105, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Cao, C.; Zou, X.; He, J.; Yan, H.; Wang, G.; Steer, D. Measurement and Modeling of Penetration Loss in the Range from 2 GHz to 74 GHz. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Washington, DC, USA, 4–8 December 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eavis, P.; Penn, I. California Says PG&E Power Lines Caused Camp Fire That Killed 85. The New York Times. 15 May 2019. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/15/business/pge-fire.html (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- Clark, D.G.; Ford, J.D.; Tabish, T. What role can unmanned aerial vehicles play in emergency response in the Arctic: A case study from Canada. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, J.C.; Wakeham, R.T. Unmanned Aerial Systems in the Fire Service: Concepts and Issues. In Proceedings of the Aviation/Aeronautics/Aerospace International Research Conference, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 15–18 January 2015; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Luomala, J.; Hakala, I. Effects of temperature and humidity on radio signal strength in outdoor wireless sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 2015 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS), Lodz, Poland, 13–16 September 2015; pp. 1247–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Target Fire Protection. Target Fire Protection Ltd., 2017. Available online: https://www.target-fire.co.uk/news/what-is-the-temperature-of-fire/ (accessed on 18 October 2019).

- Li, Y.W.; Yuan, H.Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, R.F.; Ming, F. A novel protocol to measure the attenuation of electro-magnetic waves through smoke. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2016, 27, 065902. [Google Scholar]

- Sciuto, G.L. Air pollution effects on the intensity of received signal in 3G/4G mobile terminal. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2019, 10, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, M.; Aschauer, R.; Asenbaum, A.; Vasi, C.; Wilhelm, E. Interferometric determination of the refractive index of liquid sulphur dioxide. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2000, 11, 1714–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veris Industries. Veris Aerospond Wireless Sensors: Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI); Veris Industries: Tualatin, OR, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chinthaka, M.D.; Malka, N.H.; Ramamohanarao, K.; Moran, B.; Farrell, P. The signal propagation effects on IEEE 802.15.4 radio link in fire environment. In Proceedings of the 2010 Fifth International Conference on Information and Automation for Sustainability, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 17–19 December 2010; pp. 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wotton, B.M.; Gould, J.S.; McCaw, W.L.; Cheney, N.P.; Taylor, S.W. Flame temperature and residence time of fires in dry eucalypt forest. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2012, 21, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, A.C.M. Wireless Channel Characterization in Burning Buildings Over 100–1000 MHz. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2016, 64, 3265–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphale, K.; Heron, M. Microwave measurement of electron density and collision frequency of a pine fire. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2007, 40, 2818–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firerescue1.com. IAFF: Voice Radio Communications Guide for the Fire Service, Section 2—Basic Radio Communication Technology. 2017. Available online: https://www.firerescue1.com/fire-products/communications/articles/iaff-voice-radio-communications-guide-for-the-fire-service-section-2-basic-radio-communication-technology-RgQG1khps2pimfXd/ (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- WAVIoT LPWAN. “NB-Fi vs Competitors”—WAVIoT LPWAN. 2010. Available online: https://waviot.com/technology/waviot-lpwan-technology-comparison (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Scholz, M.; Gordon, D.; Ramirez, L.; Sigg, S.; Dyrks, T.; Beigl, M. A concept for support of firefighter frontline communication. Futur. Internet 2013, 5, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragó, Á.; Kántor, P.; Bitó, J.Z. Rain Effects on 5G millimeter Wave ad-hoc Mesh Networks Investigated with Different Rain Models. Period. Polytech. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2016, 60, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, H. A Flame Attenuation Analysis Using State-of-the-Art Millimeter Techniques. IEEE Trans. Mil. Electron. 1965, 9, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, C.U.; Wang, R.; Choi, T.; Hur, S.; Whang, K.; Park, J.; Molisch, A.F. Outdoor to Indoor Penetration Loss at 28 GHz for Fixed Wireless Access. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Kansas City, MO, USA, 20–24 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violette, E.J.; Espeland, R.H.; DeBolt, R.O.; Schwering, F.K. Millimeter-wave Propagation at Street Level in an Urban Environment. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1988, 26, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Manabe, T.; Ihara, T.; Saito, H.; Ito, S.; Tanaka, T.; Sugai, K.; Ohmi, N.; Murakami, Y.; Shibayama, M.; et al. Measurements of Reflection and Transmission Characteristics of Interior Structures of Office Building in the 60-GHz Band. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1997, 45, 1783–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Mayzus, R.; Sun, S.; Samimi, M.; Schulz, J.K.; Azar, Y.; Wang, K.; Wong, G.N.; Gutierrez, F.; Rappaport, T.S. 28 GHz Millimeter wave cellular communication measurements for reflection and penetration loss in and around buildings in New York city. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Budapest, Hungary, 9–13 June 2013; pp. 5163–5167. [Google Scholar]

- Glass for Europe. Low-E Insulating Glass for Energy Efficiency Building. Glass for Europe, 2009. Available online: http://www.glassforeurope.com/ (accessed on 4 October 2023).

- Todtenberg, N.; Kraemer, R. A survey on Bluetooth multi-hop networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2019, 93, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulić, P.; Kojek, G.; Biasizzo, A. Data Transmission Efficiency in Bluetooth Low Energy Versions. Sensors 2019, 19, 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaycon Systems. Bluetooth Technology: What Has Changed Over the Years. Medium. 2017. Available online: https://medium.com/jaycon-systems/bluetooth-technology-what-has-changed-over-the-years-385da7ec7154 (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- Baert, M.; Rossey, J.; Shahid, A.; Hoebeke, J. The bluetooth mesh standard: An overview and experimental evaluation. Sensors 2018, 18, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novel Bits. “BLE Power Consumption Optimization: The Comprehensive Guide”—Novel Bits. 2017. Available online: https://www.novelbits.io/ble-power-consumption-optimization/ (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- Brentwood Communications. “Motorola DP4401 EX for Sale” Brentwood Communications. 2015. Available online: https://www.brentwoodradios.co.uk/two-way-radios/motorola-dp4401-ex-2/ (accessed on 13 November 2019).

- Amar Infotech. 10 Major Differences—Bluetooth 5 vs 4.2—Feature Comparisons. 2018. Available online: https://www.amarinfotech.com/differences-comparisons-bluetooth-5-vs-4-2.html (accessed on 4 October 2023).

- Townsend, K. Bluefruit nRF52 Feather Learning Guide. Adafruit Learning System. 2017. Available online: https://learn.adafruit.com/bluefruit-nrf52-feather-learning-guide?view=all (accessed on 13 November 2019).

- Roser, M.; Appel, C.; Ritchie, H. Human Height. Our World in Data. 2013. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/human-height (accessed on 4 October 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).