Abstract

The success of touristic businesses, attractions, and destinations heavily relies on travel agents’ recommendations, which significantly impact client satisfaction. However, the underlying recommendation process employed by travel agents remains poorly understood. This study presents a conceptual model of the recommendation process and empirically investigates the influence of tourism categories on agents’ destination recommendations. By employing collaborative filtering-based recommendation systems and comparing various algorithms, including matrix factorization and deep learning models, such as the bilateral variational autoencoder (BiVAE) and light graph convolutional neural network, this research provides insights into the performance of different techniques in the context of tourism. The models were evaluated using a tourism dataset and assessed through a range of metrics. The results indicate that the BiVAE algorithm outperformed others in terms of ranking and prediction metrics, underscoring the significance of considering multiple measurements and exploring diverse techniques. The findings have practical implications for tourism marketers seeking to influence travel agents and offer valuable insights for researchers investigating this domain. Additionally, the proposed model holds potential for applications in travel recommendation systems, including attraction recommendations.

1. Introduction

Since millions of people visit different destinations every year, arranging a trip might be difficult for travelers. Although the internet has made it simpler for users to plan their vacations, the increasing volume of online content can make it challenging to promptly find appropriate locations and activities. With increasing demand in the tourism industry, meeting the needs and desires of customers has become crucial. To address this issue, researchers have implemented recommendation systems (RSs) using various techniques [1].

Artificial intelligence and machine learning have played significant roles in RS development by enabling computers to learn from large datasets and provide personalized recommendations to users. Mainly, RSs gather data to build their recommendations and predict which items are worth recommending to a user. Different RSs predict the utility of a recommendation in different ways, depending on their recommendation algorithm [1,2].

RSs can help organize vast amounts of data on the internet by considering users’ reviews and examining their previous history. The recommendation methodologies can be classified into many distinct categories such as collaborative filtering (CF), content-based filtering (CB), hybrid filtering, demographic RS, knowledge-based RS, risk-aware recommender RS, social network RS, and context-aware RS [3]. Generally, CF and CB are two common approaches employed in RSs. CF recommends items to users based on their past user behavior and the behavior of similar users, whereas CB involves analyzing the characteristics of different activities to make recommendations [2]. CF was shown to be effective in several investigations and outperformed other techniques [4].

In recent years, there has been significant growth in the number of studies and amount of research on RSs. These studies have applied various research methodologies, which result in a diverse range of outcomes in different contexts. Results obtained depend on various factors such as the source of the dataset, preference elicitation protocol, data preprocessing techniques, types of features used, and the intended RS applications.

Tourism recommendations must consider the context of a user’s trip, such as the time of year, weather, and category (e.g., sports, events, relaxation, and nature). To provide relevant suggestions, this contextual information should be integrated into recommendations. In this study, to examine its impact on agents’ recommendations, we incorporated the tourism category.

Although there have been a significant number of design studies published in this field, RSs face several challenges that can affect their accuracy and effectiveness in providing relevant recommendations to users. One of the key challenges is the cold-start issue, where the system struggles to provide recommendations for new users or items with limited data. Another challenge is the sparsity problem, where the system has limited or incomplete data regarding users and items, making it challenging to provide accurate recommendations [5]. In this study, we aimed to examine some of the challenges in tourism RSs, specifically the recommendation process employed by travel agents.

This study introduces a conceptual model that explores the recommendation process and examines the impact of tourism categories on agents’ destination recommendations. The research employs collaborative filtering-based recommendation systems and conducts a comparative analysis of different algorithms, including matrix factorization, bilateral variational autoencoder (BiVAE), and light graph convolutional neural network. By doing so, the study offers valuable insights into the effectiveness of various techniques within the tourism context.

The study is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the research problematic. Section 3 presents the related work on RSs and the methods used in tourism. Section 4 presents a description of the investigated algorithms. Section 5 discusses the experiment and methodology applied in this work. Section 6 contains the analysis and results. Section 7 includes the conclusion and future work.

2. Research Problematic

Travel agents play a significant role in influencing client satisfaction and the success of touristic businesses, attractions, and destinations. However, the recommendation process that travel agents use is not well understood, which can hinder tourism marketers seeking to influence travel agents and researchers interested in studying this area.

We can outline these issues that motivate our research into a (i) lack of understanding of the recommendation process employed by travel agents; the (ii) influence of travel agents on client satisfaction and the success of touristic businesses, attractions, and destinations; (iii) limited knowledge hindering tourism marketers in influencing travel agents effectively; and a (iv) research gap in comprehensively studying the recommendation process utilized by travel agents. By examining these challenges, our research aims to provide insights into the recommendation process employed by travel agents, offer practical implications for tourism marketers seeking to influence travel agents, and contribute to the existing body of knowledge in this area.

To address this knowledge gap, we proposed a conceptual model of the recommendation process and empirically investigated the impact of tourism category on agents’ destination recommendations. We also compared the performance of different recommendation algorithms, including matrix factorization and deep learning models, such as bilateral variational autoencoder (BiVAE) and light graph convolutional neural network (LightGCN), on a tourism dataset using various metrics. Our analysis showed that the BiVAE algorithm performed the best in ranking and prediction metrics, which highlights the importance of considering multiple measurements and exploring different techniques to address a problem.

3. Related Work

Tourism is a social, cultural, and economic phenomenon associated with the movement of people to places outside their usual residence for personal or business-related reasons [6]. RSs in the tourism field help individuals filter all the information stored online to locate suitable places to visit [7]. Various studies have focused on the different types of RSs in tourism [8,9]. Moreover, we discussed the contextual aspects of tourism in RSs.

3.1. Contextual Aspects of Tourism

Khan et al. [10] suggest a categorization of contextual aspects in tourism RSs. The RS framework was categorized into five distinct categories, each catering to specific aspects of RSs, as follows:

- Time-Based Frameworks that leverage temporal information, such as the time of day, day of the week, or even the season, to improve the precision of recommendations.

- Activity-Based Frameworks that identify various human activities for tailored recommendations. These activities include low-level activities like eating, reading, and listening to music and high-level activities, including social interactions and outdoor explorations.

- Location-Based Frameworks that utilize technologies like GPS to estimate a user’s geographical position and aid travelers in unfamiliar regions.

- Social-Based Frameworks that consider social constructs and user interactions such as individual preferences, social connections, tags, and social descriptions gathered from various sources like websites, social networks, and online forums.

- Multi-Dimensional Frameworks that consider multiple contextual factors including weather conditions, user mood, and specific user interests. This approach acknowledges contextual variables that can significantly impact user preferences for accurate recommendations.

3.2. Tourism and RSs

In this section, different research aspects of such types related to tourism RSs, including CF and knowledge-based and hybrid systems, are briefly discussed. Table 1 summarizes the related work in tourism RSs.

3.2.1. Collaborative Filtering

CF is one of the most commonly used techniques in tourism RSs [11]. The CF method recommends tourist destinations according to their relevance to tourists’ preferences [12]. In CF, users’ interests are predicted based on the interests of other users who resemble them. This is performed by analyzing the user’s interactions with the item and determining commonalities in the data that can be utilized to predict which item a user may like [2]. There are two types of CF: memory-based and model-based. Memory-based RSs conduct recommendations by connecting directly to the database, whereas model-based RSs employ machine learning and transaction data to build a model that can provide recommendations [13].

Machine learning is widely used in various fields, such as tourism RSs, to enhance their efficiency [11]. For instance, Jomsri [8] applied machine learning and analytic hierarchy process techniques to develop a system that guides boat travel destinations in Om Non-Canal, Thailand. The model collects historical data for each user’s travel from the user location, and K-means clustering is applied to create models for grouping tourists based on the brief history that each traveler identified. The analytical hierarchy process is then applied to rank the tourist attractions according to the information from experienced travelers. The Spearman correlation coefficient is employed to measure the relationship between the order of attractions attained from the model and tourists, and it was equivalent to 0.93 in the test of ranking 30 places, which indicates that the rank from the model is correct and matches the order of the tourists.

Another study by Yoon et al. [12] proposed a real-time travel RS for tourism (R2Tour). The R2Tour employs a machine learning model that considers situational factors, including temperature and tourist profiles, to recommend the top five most popular tourist destinations nearby. The authors experimented with six different machine learning algorithms to evaluate the effectiveness of the system using information regarding Jeju Island’s tourist attractions, including K-nearest neighbors, support vector machine, random forest, voting, XGBoost, and LightGBM. XGBoost and LightGBM models had very similar results, with LightGBM outperforming the other models with 77.3% accuracy, 0.773 micro-F1, and 0.415 macro-F1. Moreover, the classification of tourist activity patterns utilizing XGBoost based on real-time context resulted in the highest accuracy of 80.6%, micro-F1 of 0.806, and macro-F1 of 0.73.

3.2.2. Knowledge-Based RS

A knowledge-based RS makes recommendations based on user queries and rating history. It asks the user to give some rules or instructions to search for it through the database and produce the results. It can use real-time and context-aware techniques to recommend relevant items to users. The primary distinction between the two is the data they utilize to make recommendations. Real-time RSs are designed to provide recommendations for immediate user behavior data [14].

Sittisaman et al. [15] present a real-time tourism information RS on a smartphone (RTIRS) by applying a responsive web design. Their proposed system comprised three parts: spatial and temporal ontologies, the responsive web design using Bootstrap framework, and the system architecture using PHP and SPARQL. Two experiments were carried out. In the first experiment, they searched for an attraction place for tourists, and the RTIRS displayed correct search results along with a route from the user’s location. In the second experiment, a real-time tourism information recommendation test was conducted where RTIRS recommended tourism details according to the geographical coordinates of the user. Their proposed system obtained good results with an F-score of 95.88%.

3.2.3. Hybrid Systems

Due to the difficulty in dealing with the size of the required data and the cold-start problem caused by CF [16], several works have combined multiple approaches to balance the problems that are associated with each method. For example, Brodeala et al., in [9], built an RS that is dedicated to recommending accessible tourism destinations to ease the process of end-to-end holiday planning for people with disabilities. They took user reviews from public websites, such as TripAdvisor, and disability descriptions from dedicated websites as a starting point. Their chosen approach was a hybrid system that was built from collaborative, CB, knowledge-based, and multi-objective approaches.

Bourgais et al. [16] also used a hybrid system that combined CF and CB approaches, along with a rule-based approach that considered the user’s time of visit, the number of people present, or their financial status concerning the trip. They attempted to address the overspecialization issue in the tourism domain via semantic trajectory. Their concept was to employ semantic information and conduct logical reasoning beforehand to increase the score of points of interest (POIs) along the computed trajectories. They provided a use case example of the overall process in Rouen, France and showed that their proposed method provided diversity among the recommended POIs.

Forouzandeh et al. [7] combined the artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm with the fuzzy TOPSIS method to recommend the best tourist destination for users according to their preferences. They applied their methodology to a TripAdvisor dataset collected from Facebook that contained 1015 online questionnaires. They used precision, recall, and F1 metrics to illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach and compared the results with other algorithms, namely, CB, CF standard, and collaborative systems, which contain several algorithms called tourism RS-related algorithms. Their findings indicated that the proposed method performed best. In the first phase, the TOPSIS model was employed to define places with the highest score, which produced a positive ideal solution that was represented by a four-column matrix. During the second stage, the ABC algorithm began to examine the destinations and recommended the shortest destinations to the user’s ideal location.

Other research presented different techniques published in the tourism field. For instance, Shao X. et al. [17] proposed a sentiment-aware multi-modal topic model to mine the multi-modal latent semantics of the data on the travel website. The system was applied to two personalized recommendation applications, namely, the single-platform traveling recommendation and the inter-platform traveling recommendation. Two datasets were constructed to validate the two platforms, namely, TripAdvisor and Trip website. Features such as part of speech, word tagging function from NLP, and SIFT-Bow were used. For the experiment evaluation, 24 university students volunteered to label the returned recommendation list as if it was relevant to the query or not. Evaluation results based on the online travel website revealed the enhanced performance of their method with an improvement in the precision equal to 0.06.

Zhao et al. [18] proposed the Photo2Trip system, which is a visual feature-enhanced tour RS that employs the visual contents and CF models. Their work was intended to cover the lack of work that considers the visual content information for tour recommendations. The Photo2Trip system comprised three parts: photos from Flickr website, visual features generated using the visual toolbox, and user input constraints. A dataset from Yahoo! was used in the proposed system with 100 M photos and videos. The proposed model outperformed the baseline model with an increase of 8.0% in the average F1-score, which shows the effectiveness of integrating CB into predicting visit interests in trip planning.

Context-aware RSs use contextual information, such as location, weather conditions, and user profile, to recommend items that are specific to the user’s needs and preferences [19]. Camacho et al. [20] tested a synthetic dataset on four recommendation models, namely, CB, demographic-based, popularity-based, and CF approaches, each employed with specific algorithms. They proposed an ontology-based context-aware travel RS application using these models at various maturity levels. They used field-aware factorization machines (FFMs) for CF to easily include context awareness, which yielded the best performance with a mean average precision (MAP) of 0.18.

Another research paper conducted by Nan et al. [11] introduced a collaborative mining and filtering process for context-aware travel recommendations. The performance of their approach was compared to other methods, which include methods–time measurement, average true range, and context-aware fuzzy-ontology-based tourism recommendation system. The process was assessed on a dataset that included flights, hotels, and user information regarding travel destinations from several sources. For the evaluation metrics, they applied accuracy, data processing rate, mining time, and overhead. Their findings indicated effective results with a high accuracy of 8.26%, a high data handling rate of 7.41%, a reduction of 10.47% in mining time, and a reduction of 12.35% in overhead.

Han et al. [21] proposed a tourist attraction recommendation model that combines spatial, temporal, and visual embeddings using Flickr-geotagged photos as a data source and a matrix factorization RS. They used Word2Vec to model the spatial and temporal factors. They obtained a precision of 0.1557 and recall of 0.3114.

Many challenges must be addressed in RSs, including cold-start and sparsity problems. Moreover, RSs must handle the problem of scalability, as they must process large amounts of data and provide real-time recommendations to users. The accuracy of recommendations can also be affected by the quality of input data and bias in the data or algorithm. Another challenge is the privacy issue; considering that RSs often collect and use personal data to provide recommendations, it raises data privacy and security concerns. Finally, RSs must also address the issue of diversity, given that providing the same type of recommendations to users can lead to a lack of novelty and user dissatisfaction [16].

Table 1.

Summary of related works.

Table 1.

Summary of related works.

| Ref. | Dataset | RS Type | Approach | Task | Algorithm | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | TripAdvisor | Hybrid | TOPSIS method, CB, CF, and CL | Ranking | ABC algorithm | Precision, recall, and F1-score |

| [9] | TripAdvisor | Hybrid | Hybrid of CF, CB, KB, and multi-objective | Ranking | N/A | N/A |

| [16] | Raw touristic data | Hybrid | Combination of CF, CB, and rule-based approaches | Prediction | N/A | POIs score |

| [8] | Historical data collected from user location | CF | Machine learning techniques and analytic hierarchy process | Ranking | K-means clustering, analytical hierarchy process | Spearman correlation coefficient |

| [15] | Collect spatial and temporal ontology according to areas | Knowledge-based | Responsive web design | Ranking | PHP and SPARQL | F1-score, recall, and precision |

| [12] | Information about Jeju Island’s tourist attractions | CF | ML | Ranking | K-NN, SVM, RF, voting, XGBoost, and LightGBM | Accuracy, micro-F1, and macro-F1. |

| [20] | Hotel synthetic dataset | Hybrid | CB, demographic-based, popularity-based and CF | Ranking and Prediction | Field-aware factorization machines for CF | MAP, MAR, coverage, personalization, diversity HL, diversity LL, and novelty |

| [11] | Flights, hotels, and user information | Hybrid | Context-aware | Ranking | Collaborative mining and filtering process (CMFP) | Accuracy, data processing rate, mining time, and overhead |

| [17] | TripAdvisor and Trip datasets | Hybrid | Mutual document projection, topic space projection | Ranking | Used SIFT-Bow features, Part-of-Speech, word tagging, Dirichlet hyperparameters, symmetric priors | Perplexity, precision, and MAP |

| [18] | Flickr dataset | Hybrid | Visual contents and CF | Prediction | Visual-enhanced Probabilistic matrix factorization | RMSE, precision, recall, F1-score, and POIs |

| [21] | Flickr dataset | Hybrid | Context-aware and CF | Prediction | Word2Vec, visual embeddings, MF, and Bayesian Personalized Ranking | Precision, recall, MRR, and MDE |

As shown in Table 1, several studies have used a CF approach in combination with other models to enhance the efficiency of RSs in the tourism field [11,16,18,20]. Machine learning techniques have also demonstrated effective results with multiple algorithms, such as XGBoost and LightGBM [12]. Furthermore, most of the studies were observed to be dedicated to either the ranking or prediction tasks. As for the evaluation metrics, most studies used accuracy in their models. Therefore, this study will train the dataset on different CF techniques for ranking and prediction tasks. We will evaluate the results using accuracy along with different metrics that will be discussed in the following section.

4. Description of the Investigated Algorithms

In this study, we selected the BiVAE, LightGCN, SAR, SVD, and NMF algorithms to analyze the recommendation process and assess the influence of tourism categories on agents’ destination recommendations. The rationale behind these selections is as follows:

BiVAE was chosen for its ability to capture complex patterns and dependencies through variational autoencoder architecture. LightGCN was selected for its efficiency and scalability in handling large-scale recommendation datasets using graph convolutional networks. SAR was included for its real-time recommendation generation and computational efficiency, combining social- and item-based approaches. SVD was chosen as a baseline method due to its simplicity and interpretability, using straightforward matrix factorization. NMF was included to explore non-negative matrix factorization techniques and their effectiveness in recommendation analysis.

By including this diverse set of algorithms, we aim to comprehensively assess and compare their performance within the context of tourism. Each algorithm brings unique characteristics and strengths that contribute to a comprehensive analysis of the recommendation process in the tourism domain.

4.1. LightGCN Model

Neural graph collaborative filtering (NGCF) is a method for modifying graph convolutional networks in RSs. LightGCN, a condensed version of NGCF, is also available. The final embedding is the weighted sum of the embeddings acquired at all layers, which LightGCN acquires by continuously propagating user and item embeddings on the user–item interacting network [22].

4.2. SAR Model

The simple algorithm for recommendation (SAR) is based on consumer transaction history. It is a quick, scalable, and adaptive system for customized recommendations that works by identifying similarities among items and proposing related products to those that a user already has a preference for [23].

4.3. SVD Model

The singular value decomposition (SVD) model takes a rectangular matrix of gene data expression and factors it into a real or complex matrix. SVD reflects the growth of the initial data in a diagonal covariance matrix-based coordinate system [24].

4.4. NMF Model

Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) is a statistical method that enables us to reduce the size of the input corpus. It employs the factor analysis method to assign smaller weights to words with less coherence. The NMF model has a two-layer directed graphic structure, comprising observed and hidden random variables [25].

4.5. BiVAE Model

The bilateral variational autoencoder (BiVAE) model integrates two inference models, user-based and item-based, parameterized by neural networks, with a generative model of dyadic data. It can be implemented as either a user-side or item-side Bayesian variational autoencoder [26].

5. Proposed Methodology

This study presents a conceptual model of the recommendation process and empirically investigates the influence of tourism categories on agents’ destination recommendations. By examining RS challenges in the context of tourism, our research aims to provide insights into the recommendation process employed by travel agents and offer practical implications for tourism marketers seeking to influence travel agents.

In this research, we applied the CF approach using various techniques to predict hotel ratings and recommend the most relevant tourist attractions for the user. To our knowledge, this dataset has only been examined by one study to use different RS approaches and evaluate their performance [20].

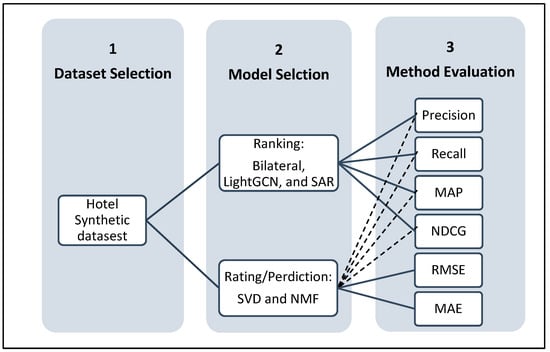

For our experiment, we evaluated the effectiveness of different CF techniques in predicting ratings and recommending the top 10 relevant tourist attractions to the user. Figure 1 illustrates the procedures applied in our work. First, we chose the tourism dataset. Next, we applied four CF algorithms designed to rank and predict hotel ratings. For ranking, we used the bilateral, LightGCN, and SAR models. For rating prediction, we employed two matrix factorization techniques, namely, SVD and NMF.

Figure 1.

Research architecture of recommender system.

Afterward, we evaluated the performance of each algorithm using different metrics and compared their results. The matrix factorization techniques were intended to produce high accuracy, not for top-rank predictions. Nevertheless, to assess the performance with other models, we also presented ranking metrics such as MAP and normalized discounted cumulative gain (NDCG).

The following subsections present the experiment details, including parameters used in the proposed RS models, and the evaluation metrics used to evaluate the performance of our models.

5.1. RS Model Hyperparameter

We trained the models using different CF algorithms on the tourism dataset. We split the dataset for all models into a ratio of training (75%) and testing (25%) datasets using a stratified split based on items.

The number of seeds for all models and the maximum number of epochs were set to 42 and 15, except for BiVAE and LightGCN, for which the maximum numbers of epochs were set to 50 and 5. For ranking metrics, we used k = 10 (top 10 item recommendations for the user). Table 2 shows the settings for each algorithm, which were adjusted to obtain the optimal results for each model.

Table 2.

Hyperparameter settings for the proposed RS models.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

Numerous studies have utilized metrics such as root mean squared error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE) for performing regression on 1–5 ratings [20], whereas others have used machine learning classification metrics such as precision, recall, and accuracy. In our proposed experiments, we evaluated all models primarily using precision and recall metrics, besides other metrics as shown below.

5.2.1. Ranking Metrics

Precision is a measure of the model’s efficiency, specifically the level of correct predictions it makes. It is calculated using Equation (1) [27].

Recall, also known as the true positive rate, is the proportion of data points from an important class that a machine learning model correctly identifies as being among all samples from that class. It calculates the percentage of actual positive labels that the model accurately identified [27]. Recall can be calculated using Equation (2):

MAP is a statistic used to assess models for object detection. It calculates the mean of average precision values across recall values between 0 and 1 by computing the AP across all classes and/or total IoU levels [28]. Assuming that U is a user, m is a rating interaction, and is the assembly of ranked items, MAP can be calculated using Equation (3):

NDCG is a measure of the ranking system’s effectiveness that considers the order in which relevant items appear in the ranked list. It is based on the idea that higher-ranked items should receive more credit than lower-ranked items. NDCG is commonly used to evaluate the performance of search engines, RSs, and other information retrieval systems [28].

Assuming that is the ideal discounted cumulative gain that calculated ideal relevance order, m is a rating interaction, and represents hit (1 or 0) when an item is in its ranking position, NDCG@K can be calculated using Equation (4):

5.2.2. Predicting/Rating Metrics

RMSE is commonly used to assess the accuracy of forecasts. It represents the Euclidean distance between the measured true values and the forecasts. It is frequently employed in climatology, forecasting, and regression analysis to validate experimental results [29].

MAE measures the quantity of measurement error, which is the difference between the measured value and the true value. It is a measure of the average size of errors in a set of forecasts, without considering their direction. MAE is employed to evaluate the effectiveness of a regression model and is calculated as the average absolute difference between the predicted and actual values [29].

5.2.3. Run-Time Performance

This refers to the time taken to train a model and to use it for predicting or recommending K items, measured in seconds.

6. Experiments and Results

6.1. Dataset Analysis

The tourism dataset describes the services offered by hotels to tourists. It contains synthetically generated data that can be used for training RSs, as well as demographic information regarding the users, item categories, and user ratings.

This dataset was created using a synthetic data generation methodology that employed different techniques, including Gaussian copulas and fuzzy logic inference systems.

The dataset is publicly available on Kaggle [30], and it comprises four CSV files: icat, rats, ufeat, and user_info. The icat file contains item information, including a unique identifier name, category, and implicit quality used to generate user ratings. The rats file contains user ratings of items, whereas the ufeat file contains user demographic information such as age, gender, and region. The user_info file contains user information such as first and last name and email, all of which are synthetic data.

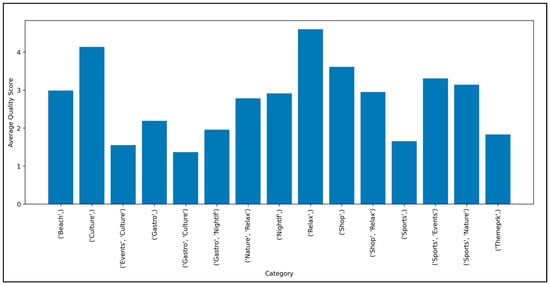

The dataset contains 345,000 ratings provided by 100,000 users who rated 23 items. This dataset can be used by researchers to develop and evaluate RSs in the tourism domain. Figure 2 presents the quality score for each category in the dataset.

Figure 2.

Average quality score for each category of items.

6.2. Results and Discussion

Table 3 presents the performance of the four techniques applied to the CF approach on the dataset. N/A is employed to indicate the unavailability of data. The highest score for each metric is underlined.

Table 3.

Detailed statics on models’ performances with different metrics.

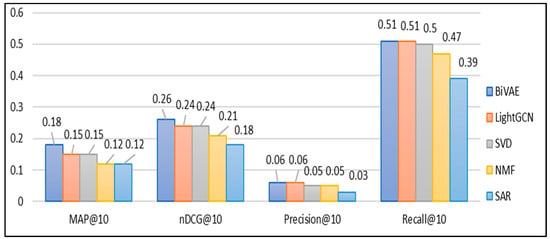

Figure 3 displays the distribution of results for four models in terms of ranking metrics—precision, recall, MAP, and NDCG. The results show that the BiVAE model outperformed all other models with a 0.18 MAP, 0.26 NDCG, 0.06 precision, and 0.51 recall.

Figure 3.

Distribution of four models’ performances with ranking metrics.

This is a good result for this dataset, as previously reported by Camacho et al., who achieved the same MAP value of 0.18 using the FFM model, which was most successful with CF in comparison to other models. We also observe that LightGCN had the same highest results in terms of precision and recall as BiVAE, making it the second most effective model for this dataset. Moreover, LightGCN and SVD produced the same results, with an MAP value of 0.15 and an NDCG value of 0.24.

To assess the performance of the BiVAE, LightGCN, and SAR models, we only used the ranking metrics as these models are designed for recommending related items to users rather than predicting explicit ratings for user–item pairs. Meanwhile, we applied the prediction metrics (RMSE and MAE) only to the matrix factorization models SVD and NMF as the matrix factorization algorithm was developed to predict ratings as close as possible to their actual values.

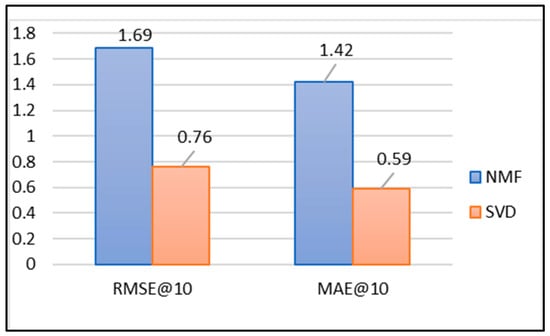

Figure 4 shows that SVD achieves a lower error rate with an RMSE and MAE of 0.76 and 0.59, respectively, which indicates a good result. This suggests that on average, the error in predicted ratings is less than one. Furthermore, the RMSE of both models is slightly higher than the MAE: SVD achieved an RMSE and MAE of 0.76 and 0.59, and NMF achieved an RMSE and MAE of 1.69 and 1.42, respectively. This is expected since higher errors are penalized more.

Figure 4.

Distribution of RMSE and MAE scores for NMF and SVD models.

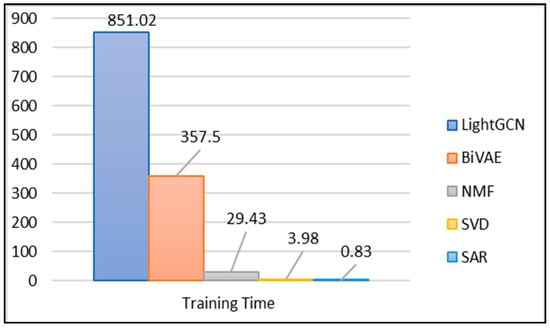

Additionally, the training time durations of the models were examined, as illustrated in Figure 5. The LightGCN model exhibited the longest training time, requiring 851.02 s, while the SAR model demonstrated exceptional efficiency with a training duration of only 0.83 s. The BiVAE model, with a training time of 357.50 s, outperformed the LightGCN model in all evaluated metrics. Notably, the BiVAE model consistently demonstrated superior performance across all metrics, showcasing its efficacy within the context of our study. Conversely, the SAR model exhibited comparatively weaker performance when compared to the other models. These findings highlight the superior performance of the BiVAE model and emphasize the potential limitations of the SAR model in our specific investigation. As part of our future work, we aim to incorporate alternative models and further refine our proposed model to enhance its overall performance in the recommendation process.

Figure 5.

Distribution of training time taken in seconds by each model.

In comparing our work with the related research, we observed that the BiVAE model outperformed all other models in terms of ranking metrics such as precision, recall, MAP, and NDCG. This result is similar to the findings of Camacho et al. [20], who achieved an MAP value of 0.18 using the FFM model, which was the most successful collaborative filtering (CF) model in their study.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed recommendation models to provide new insights into the tourism field using various algorithms, including BiVAE, LightGCN, SAR, SVD, and NMF models. The models were assessed with different types of metrics, such as ranking and prediction. Our analysis suggested that the BiVAE algorithm is the most beneficial for this type of dataset as it achieved the highest score in both metrics.

Therefore, we consider BiVAE to be an appropriate RS for this study. Conversely, the SAR model had the worst performance compared to other models. We also measured the training time taken by each model and reported the results in seconds. From the analysis, we noticed that the LightGCN model took significantly more time than other models, with a difference of 851.02 s. Meanwhile, BiVAE took less time (357.50 s) and performed better.

These findings demonstrate the importance of considering multiple measurements when conducting an RS, and they show the value of exploring different techniques to address a problem. Our suggested model can also be used for travel recommendation applications, including attraction recommendations. For future plans, we will develop our work by incorporating different models, such as knowledge-based models, and enhancing the overall performance of the model.

Author Contributions

G.A. (Ghadeer Alrehaili) and G.A. (Ghadi Alyahya) researched the literature, implemented the experiment, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. M.A. designed and supervised the analysis, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and contributed to the discussion. A.A.-N. and W.M.A.-N. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-RG23151).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in Kaggle [30] at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/vitortcamacho/recommendersystemtourism-pmpproject (accessed on 14 April 2023).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) for funding and supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Singh, A.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, A.; Katarya, R. A Systematic Survey of Tourism Recommender System Techniques and Challenges. J. ISMAC 2022, 3, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Fararni, K.; Aghoutane, B.; Yahyaouy, A.; Riffi, J.; Abdelouahed, S. Tourism recommender systems: An overview. Int. J. Cloud Comput. 2021, 10, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitini, O.; Kaloun, S.; Bencharef, O. An Improved Recommender System Solution to Mitigate the Over-Specialization Problem Using Genetic Algorithms. Electronics 2022, 11, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Cai, Y.; Tang, G.; Xie, Y. Collaborative Filtering Recommendation Algorithm Based on TF-IDF and User Characteristics. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokde, D.; Girase, S.; Mukhopadhyay, D. Matrix Factorization Model in Collaborative Filtering Algorithms: A Survey. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 49, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Carmona, M.Á.; Díaz-Pacheco, Á.; Aranda, R.; Rodríguez-González, A.Y.; Fajardo-Delgado, D.; Guerrero-Rodríguez, R.; Bustio-Martínez, L. Overview of Rest-Mex at IberLEF 2022: Recommendation System, Sentiment Analysis and Covid Semaphore Prediction for Mexican Tourist Texts. Proces. Del Leng. Nat. 2022, 69, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouzandeh, S.; Rostami, M.; Berahmand, K. A Hybrid Method for Recommendation Systems based on Tourism with an Evolutionary Algorithm and Topsis Model. Fuzzy Inf. Eng. 2022, 14, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomsri, P. An Optimal Travel Route Recommender System for Tourists in Om Non Canal, Thailand. In Proceedings of the ISCSIC 2019: 2019 3rd International Symposium on Computer Science and Intelligent Control, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 25–27 September 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodeala, L.C. Online Recommender system for Accessible Tourism Destinations. In Proceedings of the RecSys ‘20: 14th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Virtual, 22–26 September 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 787–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman Khan, H.U.; Lim, C.K.; Ahmed, M.F.; Tan, K.L.; Bin Mokhtar, M. Systematic Review of Contextual Suggestion and Recommendation Systems for Sustainable e-Tourism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Kanato, K.; Wang, X. Design and Implementation of a Personalized Tourism Recommendation System Based on the Data Mining and Collaborative Filtering Algorithm. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 1424097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.; Choi, C. Real-Time Context-Aware Recommendation System for Tourism. Sensors 2023, 23, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aditya, P.H.; Budi, I.; Munajat, Q. A comparative analysis of memory-based and model-based collaborative filtering on the implementation of recommender system for E-commerce in Indonesia: A case study PT X. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science and Information Systems (ICACSIS), Malang, Indonesia, 15–16 October 2016; pp. 303–308. [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda-Pacheco, J.C.; Domingo, M.C. Deep learning and Internet of Things for tourist attraction recommendations in smart cities. Neural Comput. Applic. 2022, 34, 7691–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittisaman, A.; Panawong, N. A Development of Real-time Tourism Information Recommendation System for Smart Phone Using Responsive Web Design, Spatial and Temporal Ontology. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2019, 8, 994–999. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgais, M.; Zanni-Merk, C.; Fatali, R.; Alizada, N. Avoiding the Overspecialization of Recommender Systems in Tourism with Semantic Trajectories, Initial Thoughts. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 207, 1933–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Tang, G.; Bao, B.-K. Personalized Travel Recommendation Based on Sentiment-Aware Multimodal Topic Model. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 113043–113052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Xu, C.; Liu, Y.; Sheng, V.S.; Zheng, K.; Xiong, H.; Zhou, X. Photo2Trip: Exploiting Visual Contents in Geo-Tagged Photos for Personalized Tour Recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 33, 1708–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Rodd, S.F. Context Aware Recommendation Systems: A review of the state of the art techniques. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2020, 37, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, V.T.; Cruz, J. Ontology-based Context Aware Recommender System Application for Tourism. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2301.00768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, C.; Chen, K.; Gui, D.; Du, Q. A Tourist Attraction Recommendation Model Fusing Spatial, Temporal, and Visual Embeddings for Flickr-Geotagged Photos. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Deng, K.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. LightGCN: Simplifying and Powering Graph Convolution Network for Recommendation. In Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual, 25–30 July 2020; pp. 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, H. SAR: Smart Adaptive Recommendations. Microsoft. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/hongooi73/SAR (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Li, X.; Wang, S.; Cai, Y. Tutorial: Complexity analysis of Singular Value Decomposition and its variants. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.12085. [Google Scholar]

- Topic Modelling Using NMF. Available online: https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2021/06/part-15-step-by-step-guide-to-master-nlp-topic-modelling-using-nmf/ (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Truong, Q.-T.; Salah, A.; Lauw, H.W. Bilateral Variational Autoencoder for Collaborative Filtering. In Proceedings of the WSDM ’21: 14th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Virtual, 8–12 March 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, R.; Cannon, K.; Srinivas, R. A Comparative Evaluation of Recommender Systems for Hotel Reviews. SMU Data Sci. Rev. 2018, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- MRR vs MAP vs NDCG: Rank-Aware Evaluation Metrics And When To Use Them|by Moussa Taifi PhD|The Startup|Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/swlh/rank-aware-recsys-evaluation-metrics-5191bba16832 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Acharya, S. What Are RMSE and MAE? Medium. 2021. Available online: https://towardsdatascience.com/what-are-rmse-and-mae-e405ce230383 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Tourism Dataset for Recommender Systems. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/vitortcamacho/recommendersystemtourism-pmpproject (accessed on 14 April 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).