Abstract

The current hot topic in cyber-security is not constrained to software layers. As attacks on electronic circuits have become more usual and dangerous, hardening digital System-on-Chips has become crucial. This article presents a novel electronic core to encrypt and decrypt data between two digital modules through an Advanced eXtensible Interface (AXI) connection. The core is compatible with AXI and is based on a Trivium stream cipher. Its implementation has been tested on a Zynq platform. The core prevents unauthorized data extraction by encrypting data on the fly. In addition, it takes up a small area—242 LUTs—and, as the core’s AXI to AXI path is fully combinational, it does not interfere with the system’s overall performance, with a maximum AXI clock frequency of 175 MHz.

1. Introduction

Multiprocessor-System-on-Chip (MPSoC) and related on-chip networking architectures for communicating System-on-Chip (SoC) elements have been extensively investigated in the past [1]; however, their security is seldom mentioned [2]. The accuracy and security of the hardware, especially the processors, need to be enhanced because they suffer from attacks, and hardware mending is difficult or even unfeasible [3].

In embedded applications, failing to guarantee security involves economic drawbacks so trusted computing solutions have gained more and more attention [4]. In order to characterize security, the typical criteria are user authentication, storage and communications security, and input/output security [5]. A Central Processing Unit (CPU) can access physical resources in an MPSoC [6], allowing illegitimate processes executing in one or more CPUs to generate malicious requests. For instance, sensitive information can be extracted, the operations of MPSoC can be disabled, or system behavior can be modified due to attacks on MPSoCs [7]. Therefore, safety mechanisms are needed to avoid the insertion of malevolent data or orders into the system. The design of SoCs maintaining expense levels with incorporated security features and cost limitations remains a challenge to overcome. Furthermore, this security must be maintained throughout the life cycle of the embedded system [8].

MPSoC-based systems involve stringent constraints in real time as well as security requirements [9]. However, the mechanisms of real-time security demand immediate reactions and are sometimes too fast to check the protection measures affecting the safety of MPSoCs. Therefore, security must be considered a design parameter, and balancing performance with real-time security should be addressed [10]. The performance of MPSoCs is usually increased by dividing the applications into tasks and disseminating them among the computing Intellectual Property (IP) cores [7]. In addition, it involves exchanging sensitive data and IP cores can be exploited to attack the system.

In this complex scenario, the IP cores cannot be trusted; some of them may be malicious, for example, a “Hardware Trojan” [11]. This drives a very active research field since these attacks pose significant security risks for the electronics industry [12] or even the military [13]. Although most of the efforts have focused on detecting such malicious pieces of hardware [14,15], it is not the only way to deal with them. Apart from Trojan detection approaches, designs for security and run-time monitoring [12] are also used. Last but not least, another strategy used to secure systems is by encrypting the memory bus of microprocessors [16,17,18,19], video links [20,21], and peripheral communications [22,23,24]. This article introduces the evolution of a secured bus, a ciphered scheme where trusted IPs can safely communicate and are protected from the present hardware Trojans.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we provide an overview of the related work on hardware security. Section 3 describes the functionality and components of the proposed hardware Advanced eXtensible Interface (AXI) encryption IP, both in the system creation and in the IP internal structure. In Section 4, the obtained results regarding the area and time resources for a Zynq device are discussed. In Section 5, we compare the performance of our security approach to other hardware-based security solutions. Finally, Section 6 summarizes this paper and outlines future work.

2. Related Work

2.1. Security in SoC

When academia or industry addresses modern reconfigurable SoC platform security, they typically define a security boundary inside the integrated circuit. This “fence” assumes that the elements located outside it are vulnerable to potential external attackers. However, the information and subsystems within this perimeter are also vulnerable to run-time threats. In this case, the attackers may have gained access to the SoC subsystems and the variety of potential threats is wide [8,25].

The potential threats typically identified for reconfigurable SoCs are the following [26]:

- Reverse engineering attacks: The adversary obtains and analyzes the unencrypted bitstream to understand how it functions.

- Cloning and overbuilding attacks: The attacker aims to copy the firmware or the unencrypted Field-Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) bitstream and then use it in an identical device, selling it as their own.

- Tampering attacks: The adversary modifies or extracts data from the design, gaining physical access to the device.

- Spoofing: The attacker replaces the firmware or FPGA bitstream with their own.

To mitigate these threats, academia and industry have developed and built different silicon features. For example, reverse engineering and spoofing are avoided via firmware and a bitstream secure boot process [27]. The reconfigurable SoC platforms may include Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)-256 and Hash-Based Message Authentication Code (HMAC) crypto-engines to allow encrypted and authenticated firmware and bitstream storage outside the device. Yang et al. [28] proposed a high-efficiency Data Bus (DBUS) for AES-encrypted SoCs in order to reduce overheads and dynamic energy and achieve higher throughput than AXI-based implementations. They implemented and compared AES-encrypted Direct Memory Access (DMA) using AXI and DBUS interfaces to demonstrate that the DBUS could be encrypted/decrypted immediately without additional latency and power costs. These symmetric cryptography mechanisms are usually complemented by asymmetric cryptography such as Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA)-2048 for boot software signature. The unique identifiers for each integrated device, such as Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) or Physical Unclonable Function (PUF), are widely used in these platforms to enhance the security of the cryptographic protection applied in this context [29]. Firewall IP cores have been developed to protect the SoC from malicious software [30].

This passive security is achieved by active built-in security measures. Anti-tampering sensors are complemented by robust zeroization and security lockdown mechanisms [31]. These countermeasures are in charge of erasing sensitive information and blocking access to the device’s safe zones. Access to the vendor-specific debug and configuration channels, such as the Joint Test Action Group (JTAG) or emulator, is secure. This active security strategy is completed by monitoring the on-chip temperature and voltage values to detect potential abnormal operations relating to an ongoing attack [32].

In addition to the hardware and hardware roots of the trust security mechanisms used to mitigate external attacks, it is necessary to ensure the security of these platforms at run-time operation [33]. This protection includes security mechanisms to ensure proper resource isolation and access, protect the execution of real-time applications, and secure processes and data. The protection against unwanted access during routine system operation needs real-time surveillance of hardware security mechanisms combined with security for memory, registers, peripheral and on-chip bus access, and transactions [34].

The most common security threats identified at run-time operation for SoCs are as follows: accessing memory regions restricted to other tasks or subsystems, intercepting the input/output data, DMA attacks accessing physical memory and bypassing Operating System (OS) security mechanisms, modification of device configuration registers, and malware insertion. The complex multi-core SoC platforms require intra- and inter-subsystem security mechanisms to mitigate intra- and inter-subsystem threats between privileged and non-privileged software, DMA, and bus-master-capable elements targeting memory caches, contents, and registers [35].

The inter-subsystem countermeasures are typically Memory Management Unit (MMU) hardware blocks associated with each CPU and Snoop Control Unit (SCU) [36]. These MMUs, managed by a hypervisor, typically offer a second-stage translation between logical and physical addresses. This mechanism is complemented by CPU-type secure memory management mechanisms, such as TrustZone (TZ) by Advanced RISC Machines (ARM) [37], that separate secure and non-secure memory spaces.

In addition to these MMU blocks, SoCs require inter-subsystem security mechanisms to block access to peripherals, IP cores, and memory regions used by other CPUs. It is not strange to include a rich set of security elements such as MMU, System Memory Management Unit (SMMU), Xilinx Memory Protection Unit (XMPU), Xilinx Peripheral Protection Unit (XPPU), and TZ in modern SoC platforms such as Xilinx Zynq Ultrascale+ MPSoC from Xilinx [38].

2.2. Security Scenarios

Our IP core (AXICrypt) is capable of encrypting and decrypting AXI traffic in real time, thus enabling high-security transactions.

The need for security should not always need to be proven. Although security is not always needed, several simple scenarios demonstrate the usefulness of the presented core.

One such scenario is chip-to-chip AXI communications [39]. In this example, the AXI was extended beyond the chip, making it vulnerable to outside attacks. In order to harden the system against eavesdropping, the encryption of the traffic was capitalized [40]. The authors of this article studied the feasibility of encrypted data exchange between the security software executed in a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) and the secure logic part of a heterogeneous SoC. Similar to our case, the experiment was conducted with a Xilinx Zynq-7010 SoC and two lightweight stream ciphers. Mühlbach et al. [41] proposed a scalable Tree Parity Machine Rekeying Architecture (TPMRA) IP core designed and implemented to meet the adaptability, low-cost terms, and varying bus performance requirements. The proposed system was latency-free and could be implemented in the Advanced Microcontroller Bus Architecture (AMBA) bus interface bridge to protect the ARM bus. Contrary to our case, they focused on both Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC) and FPGA implementations. He et al. [42] proved the security properties of SoC bus implementation through a scalable SoC bus verification framework. Unlike our case, they constructed Finite State Machine (FSM) models from the bus implementation based on the property set obtained from the bus protocol and potential security threats. The FSMs were constructed from SoC gate-level netlists; later security properties were designed by examining Trojans’ feasible attacks in bus protocols and IPs. They tested their method in an SoC with an AMBA bus.

Another use case is when the system must be hardened against malicious IP cores [43] or tools [44]. In this scenario, the securitization of communications between the trusted master and slave is paramount, especially when the designer has no control over the IPs that can intercept the communication. One such core is the AXI Interconnect (or any other AXI infrastructure elements) and any other IP present in the system that may have access to the AXI communications channel. This kind of hardware Trojan presents a security risk to IP-based FPGA designs [45,46]. Another threat is a malicious IP that can tamper or send spurious messages to other IPs [47,48].

2.3. Ciphers

Many modern applications demand strong security so private data is encrypted by ciphers when it has to be saved or forwarded through vulnerable channels. After that, to be retrieved, a decryption process is needed [49,50]. The resistance against attacks is measured by cryptanalysis [51]. A cipher’s mathematical strength is mainly studied by algebraic or statistical analysis. Side-channel attacks of stream ciphers address power, faults, and timing analysis [52].

Stream ciphers constitute a significant class of encryption algorithms that have gained acceptance in resource-constrained contexts such as applications under power consumption and area limitations, among other aspects, because of their minimal influence on existing resources [51,52,53,54]. These ciphers are symmetric, which means that the used encryption and decryption keys are the same and are only known, theoretically, by reliable entities [50].

A new kind of approach has emerged in the form of quantum computing [44]. In order to manage keys secretly, the novel approach of [55] is effective. Although very promising, quantum computing is a long-term solution for security in the Internet of Things (IoT) [56].

Stream ciphers are different to block ciphers in many aspects [57]. Individual characters of plaintext are encrypted one after another by a changeable encryption conversion in stream ciphers. Meanwhile, in block ciphers, groups of characters of plaintext are encrypted in parallel through a static encryption conversion. Stream ciphers are not required to fill registers with unnecessary information or wait for data blocks, preventing the loss of time demanded by block ciphers. So, stream ciphers provide a high-security solution that runs at high frequencies and requires a small area [49]. They are generally faster than block ciphers in hardware and have less complex hardware circuitry [53].

There is a broad range of constructions of stream ciphers in the literature. They can be developed to be highly efficient only on one platform. Hence, technology-specific requirements need to be fulfilled [57]. Separate groups have made multiple efforts to develop a generation of novel secure stream ciphers [50,51]. The design of compact and efficient stream ciphers was boosted by eSTREAM [58], the ECRYPT Stream Cipher Project. The eSTREAM project comprises two profiles, high-throughput software-based ciphers that provide a security level of 128 bits or 256 bits and low-resource hardware-based ciphers that provide a security level of 80 bits [57].

A significant effort has been made to study the strength of the ciphers [52]. In [57], a comparative study of the 34 stream cipher proposals of eSTREAM was made to view the stream cipher’s design tendencies. Nowadays, eSTREAM includes seven stream ciphers, three in the hardware category and four in the software category. Grain v1, MICKEY 2.0, and Trivium are in the hardware profile, and HC-128, Rabbit, Salsa20/12, and SOSEMANUK are in the software profile [58]. Both stream and block ciphers are susceptible to fault attacks. In addition, the literature demonstrates that stream ciphers are extremely sensitive to fault attacks. Most of the eSTREAM portfolio ciphers are vulnerable to side-channel attacks. Trivium, Mickey, and Grain from the hardware profile and SOSEMANUK and Rabbit from the software category have suffered fault attacks [52].

Stream ciphers’ design must guarantee that they can avoid all known attacks. Ref. [51] analyzed Grain, Mickey, and Trivium and compared their fundamental generating structures.

The purpose of Grain stream ciphers was to design an algorithm that was simply implementable in hardware and needed a small chip with low power consumption [50,59]. A summary of an attack on the Grain family of ciphers was described in [50], and their analysis supported that a fault attack is more efficient than others against this cipher family.

There are two Mickey versions, Mickey and Mickey-128, with security levels of 80 bits and 128 bits, respectively, with the same design strategy, that is, they follow the irregular clocking of registers [51]. In [52], a fault attack on Mickey was presented, employing an extensible procedure to simplify or mount fault attacks against other ciphers.

The Trivium stream cipher is a hardware-oriented synchronous engine that, using an iterative process, obtains the values of 15 state bits used to refresh the 3 state bits and calculate 1 keystream bit [51]. The weakness of the Trivium cipher’s FPGA implementations was studied in [54], which developed four Trivium designs in two different FPGA families, proving their vulnerability to fault attacks. The implementation of hardware-profile stream ciphers was presented in [49], who used structural (Very-High-Speed Integrated Circuit) Hardware Design Language (VHDL) on the Altera FPGA. They reported that the best algorithm for hardware implementation was Trivium, the second was Grain, followed by Mickey. Ref. [49] demonstrated that Trivium presented the best performance results due to its size, flexibility, throughput, and speed. Multiple previous works related to VHDL implementations of Grain, Mickey, and Trivium on Xilinx FPGAs and Cyclone FPGA were referenced in [49]. In [59], Grain and Trivium stream ciphers were considered for hardware applications by evaluating their FPGA implementation features. Their results showed that the Trivium algorithm occupied more chip space than Grain, but it had a higher rate of keystream production.

Due to the promising results provided by Trivium and present in the literature, it was selected as the best stream cipher for our hardware applications.

2.4. Trivium

Christophe De Cannière and Bart Preneel developed Trivium as a submission to the Profile II (hardware) of the eSTREAM competition [58]. Trivium is a stream cipher designed to provide good speed and gate count in hardware [60]. Due to its virtues, it has been selected as part of the portfolio for low-area hardware ciphers (Profile 2) by the eSTREAM project. It is part of the ISO/International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 29192-3 lightweight cryptography standard [61].

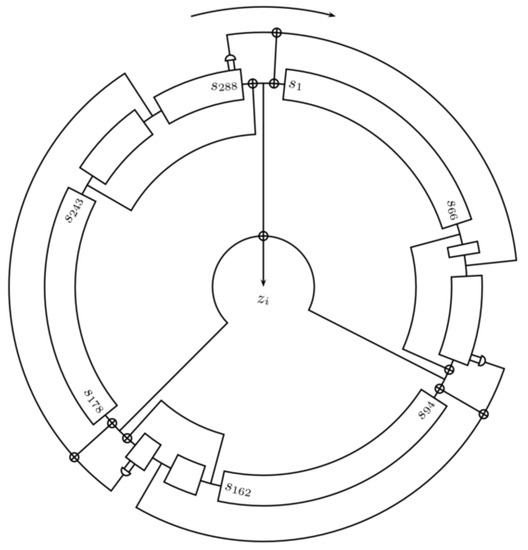

It generates up to 264 bits of output from an 80-bit key and an 80-bit Initialization Vector (IV). Its main component is a 288-bit shift register holding the internal state, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure of the trivium algorithm. The main elements are shift registers, AND gates, and XOR gates.

A nonlinear combination of taps is used in every shift to obtain the next step, following (1). Since the first 65 s of each shift register are unused, a novel state bit is used 65 rounds after it was generated. This provides the required flexibility to be able to obtain up to 64 s in every cycle. This is done by using as many feedback circuits as output bits. In practice, the powers of two values are used ().

One important aspect is that 1152 steps must be performed to initialize the state before producing any output.

3. Hardware Description

3.1. IP Hardware Description

The proposed core can encrypt/decrypt on-the-fly data in an AXI connection. In order to achieve the required minimal latency and small area footprint, the core uses the Trivium stream-cipher algorithm.

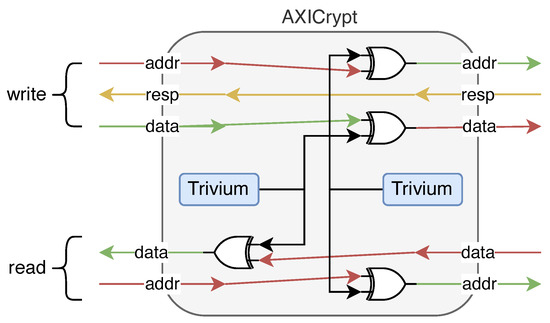

The system is built around two identical blocks, one for the channel and the other for the channel. Each one of them is composed of an existing Trivium core [62] and a handshake block. Although Trivium is a stream cipher, it can be made to provide 32-bit output data thanks to not having feedback in the first 65 s of data. A single Trivium core is capable of encrypting the or buses using this characteristic. This handshake block manages and signals when the cipher core is being initialized. The initialization is required to fill the 288-bit shift register. Once the initialization ends, the core goes into the pass-through mode where only the and/or channels are altered. With this structure, the core is AXI4 compatible. A simplified diagram can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The designed IP has two separate and optional sections, address encryption and data encryption. Both parts are built around a 64-bit Trivium core. The IP core also manages and signals when the encryption core is being initialized.

The encryption of the channel leads to problems using the AXI infrastructure. This makes use of the addresses to route the information. If this is encrypted, they cannot process it. channel encryption is only valuable for point-to-point connections. The reason is that the AXI infrastructure requires the plaintext address to correctly route the data.

This approach has several limitations:

- Each AXICrypt must be paired with another AXICrypt. Both should have the same key and IV in order to understand each other.

- Extending the system to a multimaster or multislave environment would require changing the key and IV with the added delay of the initialization period.

- Due to the previous characteristic, the core has been implemented with a fixed key and IV. This leads to a much-reduced core size.

The fixed key and IV used to initialize the core are not the best option from a security point of view [63]. The main reasons behind this are:

- The core must be capable of continuous operation.

- The core must be able to encrypt/decrypt data in a single cycle and with zero latency.

These reasons make the initialization period of the core very important. If the key and IV are changed, the core must be reinitialized, requiring the very long 1152 clock-cycle initialization period. Furthermore, a key exchange mechanism is required to exchange the key and IV.

3.2. AXI Infrastructure

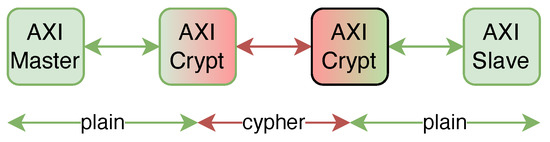

A simplified diagram of the secured system is depicted in Figure 3. A master sends data; at one point, the proposed core—AXICrypt—ciphers it. The ciphertext is transferred through the AXI infrastructure until it arrives at the destination AXICrypt. The core deciphers it and sends the plaintext to the destination slave.

Figure 3.

The proposed system is introduced between a master and slave. Plain text (green) is inserted into the bus by the master; the designed core encrypts it (red) and passes it to the end designed core, where it is decrypted and sent to the end slave.

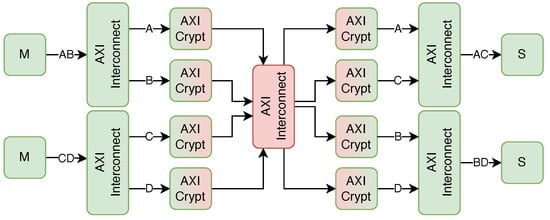

A complex multimaster system can be built. Although the core has limitations to boost its performance, they can be overcome by using an appropriate AXI infrastructure. An example is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

A multimaster–multislave environment. Any of the masters can access any of the slaves with a secured channel.

In this complex example, any of the two masters can access any of the two slaves. Every channel has its key/IV combinations, thus securing all four communication channels (A, B, C, and D). The system can also include non-secure channels or any other combination by suitably extending the central AXI interconnect.

4. Results

The use case to verify the design was a single master. This simple example was built using a single master and a single slave with two AXICrypts in the middle. Figure 5 shows the evaluation testbed. The master is in charge of performing several reads and writes to test the different configurations required. In this example, only the are encrypted.

Figure 5.

Block diagram of the example design.

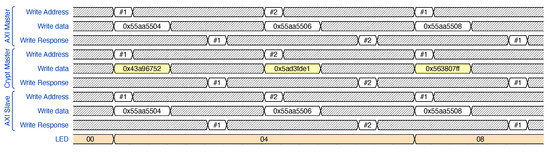

The results can be seen in Figure 6. The data (, for instance) are transferred as plaintext—line 1—until they reach the AXICrypt core. Inside the core, they are encrypted () and transferred as ciphertext—line 5. On reaching the second AXICrypt core, the data are deciphered and transmitted as plaintext—line 8. Finally, they arrive at a GPIO slave that receives the data and changes the value of the LEDs—line 10.

Figure 6.

Write transaction from an AXI master to an LED-controlling GPIO slave. data are inserted, encrypted () by the proposed IP, then decrypted by the proposed IP in the destination, and finally passed to the end slave that finally changes the values of the LEDs from to .

4.1. Area

The approach of the IP core is straightforward to minimize the required resources. In the usual case of only encryption, the area results are:

- 242 LUts

- 316 FF

The compact nature of the Trivium algorithm, which is very well-suited for FPGA implementations, helps obtain a minimal footprint. In this case, a single Trivium core is present.

4.2. Speed

The AXI-to-AXI path in the AXICrypt core is fully combinational. This leads to a zero-clock cycle delay. In other words, the presence of the core hardly affects the overall performance of the system.

Although the IP has some sequential sub-blocks, it only introduces a combinational delay to the AXI-to-AXI path. The delay might reduce the maximum AXI clock frequency; however, in our experiments, the AXI clock runs at 175 MHz. The same system, without the IP, was capable of running at 200 MHz. This leads to a 0 decrease in the maximum clock frequency.

5. Comparison

5.1. Area

Table 1 compares the area of AXICrypt with that discussed in Section 2. As can be seen, AXICrypt overcame the proposal of Benhani et al. Our approach required substantially lower resources compared to the approach by Mühlbach. Nevertheless, if one uses the traditional 6 NAND2 gates per lookup table (LUT), AXICrypt also performed favorably (22717 NAND2 → 3700 LUT)

Table 1.

Comparison of area and timing results. The results for AXICrypt are for an . Due to the combinational nature of the AXICrypt encryption, it does not have any latency. The sequential part of the core is capable of reaching 175 MHz.

5.2. Time

Table 1 compares the performance of AXICrypt with that discussed in Section 2. In this respect, all the proposals are similar, although AXICrypt outperformed Mühlbach’s proposal in terms of speed. Benhani’s proposal was slightly faster but at the cost of much higher latency. In any case, a frequency comparison is of limited value due to the different technologies used.

5.3. Capabilities

Table 2 compares the capabilities of AXICrypt. All three approaches are very similar, targeting the ARM family of buses. The encryption algorithms are equally similar; Benhani et al. [40] provided configurability in the selection of the algorithm, whereas in AXICrypt and Mühlbach et al. [41], the algorithm was hard-coded.

Table 2.

Comparison of capabilities.

Benhani et al. [40] required extensive software configuration to define the different TZ configuration registers and Xilinx Isolation Design Flow. The author stated that encryption/decryption was used only to protect sensitive data processed by the secure world. Most of the time, applications are run in the normal world with no encryption/decryption. This is the reason for much higher latency. Our proposal is focused on continuous data flow.

Mühlbach et al. [41] provided two data paths, one for encrypted and the other one for unencrypted data, whereas the others only provided one path. The approach presented in this paper is the only one with address encryption capabilities.

6. Conclusions

Electronic attacks on MPSoCs have raised interest in security concerns and memory protection requests. MPSoCs can be protected against data modification, data extraction, and denial of service attacks by encrypting the on-chip communications. Otherwise, the embedded system could be in peril because its modules can be misconfigured and unknown IPs inserted.

A proposal to enhance security in an SoC based on a Trivium stream cipher is presented in this work. AXI transaction encryption cores are distributed to secure system memories and requests between AXI master and slaves on the fly. So, our IP protects the system against data extraction.

This secure architectural solution ensures a correct and adequate separation between program code and data among reliable and unreliable applications without compromising performance—with a maximum AXI clock frequency of 175 MHz—since it is combinational. Several use cases were completed on a Zynq platform and the effectiveness of the proposed IP has been proven. It uses a straightforward approach in order to decrease the required area resources, that is, 242 LUTs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; Methodology, J.J., A.A.; Validation, U.B., L.M.; Formal analysis, A.A.; Investigation, J.L., A.A.; Writing—Original Draft, J.L., J.J.; Writing—Review & Editing, J.L., J.J., U.B.; Supervision, J.L.; Project administration, J.L.; Funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported within the fund for research groups of the Basque university system IT1440-22 by the Department of Education and within the PILAR ZE-2020/00022 and COMMUTE ZE-2021/00931 projects by the Hazitek program, both of the Basque Government, the latter also by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación of Spain through the Centro para el Desarrollo Tecnológico Industrial (CDTI) within the project IDI-20201264 and IDI-20220543 and through the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional 2014–2020 (FEDER funds).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fiorin, L.; Lukovic, S.; Palermo, G.; di Milano, P. Implementation of a reconfigurable data protection module for NoC-based MPSoCs. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Symposium on Parallel and Distributed Processing, Miami, FL, USA, 14–18 April 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, S.P.; Niazmand, B.; Jervan, G.; Sepulveda, J. Enabling Secure MPSoC Dynamic Operation through Protected Communication. In Proceedings of the 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS), Bordeaux, France, 9–12 December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancajas, D.M.; Chakraborty, K.; Roy, S. Fort-NoCs: Mitigating the Threat of a Compromised NoC. In Proceedings of the The 51st Annual Design Automation Conference on Design Automation Conference—DAC’14, San Francisco, CA, USA, 1–5 June 2004; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorin, L.; Silvano, C.; Sami, M. Security Aspects in Networks-on-Chips: Overview and Proposals for Secure Implementations. In Proceedings of the 10th Euromicro Conference on Digital System Design Architectures, Methods and Tools (DSD 2007), Lubeck, Germany, 29–31 August 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotret, P.; Gogniat, G.; Sepúlveda Flórez, M.J. Protection of heterogeneous architectures on FPGAs: An approach based on hardware firewalls. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2016, 42, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, W.; Jerraya, A.; Martin, G. Multiprocessor System-on-Chip (MPSoC) Technology. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2008, 27, 1701–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, J.; Flórez, D.; Immler, V.; Gogniat, G.; Sigl, G. Efficient security zones implementation through hierarchical group key management at NoC-based MPSoCs. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2017, 50, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Peeters, E.; Tehranipoor, M.M.; Bhunia, S. System-on-Chip Platform Security Assurance: Architecture and Validation. Proc. IEEE 2018, 106, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Salloum, C.; Elshuber, M.; Höftberger, O.; Isakovic, H.; Wasicek, A. The ACROSS MPSoC—A new generation of multi-core processors designed for safety–critical embedded systems. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2013, 37, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan, M.; Siddiqui, F.; Sezer, S.; Kang, B.; McLaughlin, K. Enforcing Policy-Based Security Models for Embedded SoCs within the Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Dependable and Secure Computing (DSC), Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 10–13 December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Forte, D.; Jin, Y.; Karri, R.; Bhunia, S.; Tehranipoor, M. Hardware Trojans: Lessons Learned after One Decade of Research. ACM Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Syst. 2017, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, S.; Hsiao, M.S.; Banga, M.; Narasimhan, S. Hardware Trojan Attacks: Threat Analysis and Countermeasures. Proc. IEEE 2014, 102, 1229–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.Q.; Zhou, Q.; Cai, Y.C.; Qu, G. Trusted Integrated Circuits: The Problem and Challenges. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2014, 29, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, W.; Sanjab, A.; Wang, Y.; Kamhoua, C.A.; Kwiat, K.A. Hardware Trojan Detection Game: A Prospect-Theoretic Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 7697–7710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, M.; Lin, D. FPGA implementations of Grain v1, Mickey 2.0, Trivium, Lizard and Plantlet. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2020, 78, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, R.; Torres, L.; Sassatelli, G.; Guillemin, P.; Anguille, C.; Bardouillet, M.; Buatois, C.; Rigaud, J. Hardware Engines for Bus Encryption: A Survey of Existing Techniques. In Proceedings of the Design, Automation and Test in Europe, Munich, Germany, 7–11 March 2005; pp. 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscock, T.; Savry, O.; Goubin, L. Lightweight instruction-level encryption for embedded processors using stream ciphers. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2019, 64, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; He, H.; Xiao, N.; Liu, F.; Zhong, G. Efficient Encryption-Authentication of Shared Bus-Memory in SMP System. In Proceedings of the 2010 10th IEEE International Conference on Computer and Information Technology, Washington, DC, USA, 29 June–1 July 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dick, R.P.; Choudhary, A. Operating System Controlled Processor-Memory Bus Encryption. In Proceedings of the 2008 Design, Automation and Test in Europe, Munich, Germany, 10–14 March 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.N.; Kousar, R.; Majid, H.; Fleury, M. Transparent encryption with scalable video communication: Lower-latency, CABAC-based schemes. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2017, 45, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Tong, X.; Meng, X. An efficient chaos pseudo-random number generator applied to video encryption. Optik 2016, 127, 9305–9319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, W.A. CANTrack: Enhancing automotive CAN bus security using intuitive encryption algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2017 7th International Conference on Modeling, Simulation, and Applied Optimization (ICMSAO), Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 4–6 April 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro, J.; Astarloa, A.; Zuloaga, A.; Bidarte, U.; Jiménez, J. I2CSec: A secure serial Chip-to-Chip communication protocol. J. Syst. Architect. 2011, 57, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, L. Design and Implementation of Encryption Filter Driver for USB Storage Devices. In Proceedings of the 2011 Fourth International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design, Hangzhou, China, 28–30 October 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmandi, F.; Huang, Y.; Mishra, P. System-on-Chip Security; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, S.; Tehranipoor, M. Chapter 10—Physical Attacks and Countermeasures. In Hardware Security; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 245–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, I.; Hogan, K.; Devadas, S. Invited Paper: Secure Boot and Remote Attestation in the Sanctum Processor. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 31st Computer Security Foundations Symposium (CSF), Oxford, UK, 9–12 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wen, W. Design of a pre-scheduled data bus for advanced encryption standard encrypted system-on-chips. In Proceedings of the 2017 22nd Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASP-DAC), Chiba, Japan, 16–19 January 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Yahya, J.; Wong, M.M.; Pudi, V.; Bhasin, S.; Chattopadhyay, A. Lightweight Secure-Boot Architecture for RISC-V System-on-Chip. In Proceedings of the 20th International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 6–7 March 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro, J.; Bidarte, U.; Muguira, L.; Astarloa, A.; Jiménez, J. Embedded firewall for on-chip bus transactions. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 98, 107707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xilinx Corp. Developing Tamper-Resistant Designs with Zynq UltraScale+ Devices. 2018. Available online: https://docs.xilinx.com/v/u/en-US/xapp1323-zynq-usp-tamper-resistant-designs (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Hasan Anik, M.T.; Ebrahimabadi, M.; Pirsiavash, H.; Danger, J.L.; Guilley, S.; Karimi, N. On-Chip Voltage and Temperature Digital Sensor for Security, Reliability, and Portability. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 38th International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD), Hartford, CT, USA, 18–21 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, G.; Narahari, B.; Simha, R.; Namazi, A.; Levy, R. FPGA SoC architecture and runtime to prevent hardware Trojans from leaking secrets. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Hardware Oriented Security and Trust (HOST), Washington, DC, USA, 5–7 May 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, K.; Saha, D.; Chakrabarti, A. Self Aware SoC Security to Counteract Delay Inducing Hardware Trojans at Runtime. In Proceedings of the 2017 30th International Conference on VLSI Design and 2017 16th International Conference on Embedded Systems (VLSID), Hyderabad, India, 7–11 January 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, S. A security vulnerability analysis of SoCFPGA architectures. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Design Automation Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–29 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmont, T.; Legat, J.D.; Quisquater, J.J. Enhancing security in the memory management unit. In Proceedings of the 25th EUROMICRO Conference, Informatics: Theory and Practice for the New Millennium, Milan, Italy, 8–10 September 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARM Inc. Arm TrustZone Technology. 2021. Available online: https://developer.arm.com/Processors/TrustZone%20for%20Cortex-A (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Xilinx Corp. Isolation Methods in Zynq UltraScale+ MPSoCs. 2020. Available online: https://docs.xilinx.com/v/u/en-US/xapp1320-isolation-methods (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Xilinx Corp. AXI Chip2Chip v5.0. 2020. Available online: https://www.xilinx.com/content/dam/xilinx/support/documents/ip_documentation/axi_chip2chip/v5_0/pg067-axi-chip2chip.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Benhani, E.M.; Lopez, C.M.; Bossuet, L. Secure Internal Communication of a Trustzone-Enabled Heterogeneous Soc Lightweight Encryption. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Field-Programmable Technology (ICFPT), Tianjin, China, 9–13 December 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbach, S.; Wallner, S. Secure communication in microcomputer bus systems for embedded devices. J. Syst. Architect. 2008, 54, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Guo, X.; Meade, T.; Dutta, R.G.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, Y. SoC interconnection protection through formal verification. Integration 2019, 64, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, S.; Du, D.; Chakraborty, R.S.; Paul, S.; Wolff, F.G.; Papachristou, C.A.; Roy, K.; Bhunia, S. Hardware Trojan Detection by Multiple-Parameter Side-Channel Analysis. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2013, 62, 2183–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Njilla, L.; Kamhoua, C.A.; Yu, Q. Thwarting Security Threats From Malicious FPGA Tools With Novel FPGA-Oriented Moving Target Defense. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. VLSI Syst. 2019, 27, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moein, S.; Gulliver, T.A.; Gebali, F.; Alkandari, A. A New Characterization of Hardware Trojans. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 2721–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; He, T. A method of implanting combinational hardware Trojan based on evolvable hardware. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2021, 93, 107229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, Q. Enhancing Architecture-level Security of SoC Designs via the Distributed Security IPs Deployment Methodology. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 36, 387–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wang, H.; Yong, J.; Jiang, X. On Secure Wireless Communications for IoT Under Eavesdropper Collusion. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2016, 13, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmolejo-Tejada, J.M.; Trujillo-Olaya, V.; Velasco-Medina, J. Hardware implementation of Grain-128, Mickey-128, Decim-128 and Trivium. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE ANDESCON, Bogotá, Columbia, 14–17 September 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hridya, P.R.; Jose, J. Cryptanalysis of the Grain Family of Ciphers: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), Melmaruvathur, India, 4–6 April 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Masood, A. Resistance of Stream Ciphers to Algebraic Recovery of Internal Secret States. In Proceedings of the 2008 Third International Conference on Convergence and Hybrid Information Technology, Busan, Korea, 11–13 November 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Chowdhury, D.R. Differential Fault Analysis of MICKEY-128 2.0. In Proceedings of the 2013 Workshop on Fault Diagnosis and Tolerance in Cryptography, Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 20 August 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, A.J.; van Oorschot, P.C.; Vanstone, S.A. Handbook of Applied Cryptography; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potestad-Ordonez, F.E.; Jimenez-Fernandez, C.J.; Valencia-Barrero, M. Vulnerability Analysis of Trivium FPGA Implementations. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. VLSI Syst. 2017, 25, 3380–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lou, X.; Fan, Z.; Wang, S.; Huang, G. Verifiable Multi-Dimensional (t,n) Threshold Quantum Secret Sharing Based on Quantum Walk. Int J Theor Phys 2022, 61, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Carames, T.M. From Pre-Quantum to Post-Quantum IoT Security: A Survey on Quantum-Resistant Cryptosystems for the Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 6457–6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Kausar, F.; Masood, A. Comparative Analysis of the Structures of eSTREAM Submitted Stream Ciphers. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Emerging Technologies, Washington, DC, USA, 24–26 October 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecrypt. ECRYPT Stream Cipher Project. In Encyclopedia of Cryptography and Security; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; p. 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarpour, A.; Mahdlo, A.; Akbari, A.; Kianfar, K. Grain and Trivium ciphers implementation algorithm in FPGA chip and AVR micro controller. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Computer Applications and Industrial Electronics (ICCAIE), Penang, Malaysia, 4–7 December 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cannière, C.; Preneel, B. Trivium. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 244–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Information Technology—Security Techniques—Lightweight Cryptography—Part 3: Stream Ciphers. ISO/IEC 29192-3:2012; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Mccullough, B. Random Number Generators. 2006. Available online: https://github.com/jorisvr/vhdl_prng (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Gupta, A.; Mishra, S.P.; Suri, B.M. Differential Power Attack on Trivium Implemented on FPGA. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).