Abstract

Recent advances in machine and deep learning algorithms and enhanced computational capabilities have revolutionized healthcare and medicine. Nowadays, research on assistive technology has benefited from such advances in creating visual substitution for visual impairment. Several obstacles exist for people with visual impairment in reading printed text which is normally substituted with a pattern-based display known as Braille. Over the past decade, more wearable and embedded assistive devices and solutions were created for people with visual impairment to facilitate the reading of texts. However, assistive tools for comprehending the embedded meaning in images or objects are still limited. In this paper, we present a Deep Learning approach for people with visual impairment that addresses the aforementioned issue with a voice-based form to represent and illustrate images embedded in printed texts. The proposed system is divided into three phases: collecting input images, extracting features for training the deep learning model, and evaluating performance. The proposed approach leverages deep learning algorithms; namely, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Long Short Term Memory (LSTM), for extracting salient features, captioning images, and converting written text to speech. The Convolution Neural Network (CNN) is implemented for detecting features from the printed image and its associated caption. The Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network is used as a captioning tool to describe the detected text from images. The identified captions and detected text is converted into voice message to the user via Text-To-Speech API. The proposed CNN-LSTM model is investigated using various network architectures, namely, GoogleNet, AlexNet, ResNet, SqueezeNet, and VGG16. The empirical results conclude that the CNN-LSTM based training model with ResNet architecture achieved the highest prediction accuracy of an image caption of 83%.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, machine learning algorithms and applications have contributed to new advances in the field of assistive technology. Researchers are leveraging such advancements to continuously improve human quality of life, especially those with disabilities or alarming health conditions [1]. Assistive technology (AT) deploy devices, present services or programs to improve functional capabilities of people with disabilities [2]. The scope of assistive technology research studies comprises hearing impairment, visual impairment, and cognitive impairment, among others [3,4,5].

Vision impairment can vary from mild, moderate, severe vision impairment and total blindness. In the light of the recent advances in machine learning and deep learning, research studies and new solutions for people with visual impairment have gained more popularity. The main goal is to provide people with visual impairment with visual substitution by creating navigation or orientation solutions. Such solutions can ensure self-independence, confidence, and safety for people with visual impairment in the daily tasks [6]. According to estimates, approximately 253 million individuals suffer from visual impairments: 217 million have low-to-high vision impairments, and 36 million are blind. Figures have also shown that, amongst this population, 4.8% are born with visual deficiencies, such as blindness: for 90% of these individuals, their ailments have different causes, including accidents, diabetes, glaucoma, and macular degeneration.

The world’s population is not only growing, but also getting older, meaning more people will lose their sight due to chronic diseases [7]. Such impediments can have knock-on effects; for example, individuals with visual impairments who want an education may need specialized help in the form of a helper or equipment. Learners with visual impairments can now make use of course content in different forms, such as audiotapes, Braille, and magnified material [8]. It is worth noting that these tools read the text instead of images. Technological advancements have been employed in educational environments to assist people with visual impairment, blind people, and special-needs learners, and these developments, particularly concerning machine learning, are ongoing.

The main objective of conducting visual impairment research studies is to achieve visual enhancement, vision replacement, or vision substitution as originally classified by Welsh Richard in 1981 [9]. Vision enhancement involve acquiring signals from camera which processed to produce an output display through head-mounted device. Vision replacement deals with displaying visual information to the human brain’s visual cortex or the optic nerve. Vision substitution concentrate on delivering nonvisual output in a auditory signals [10,11]. In this paper, we focus on vision substitution solution that delivers a vocal description on both printed texts and images to people with visual impairment. There are three main areas of concentration concerning research on people with visual impairment; namely, mobility, object detection and recognition and navigation. In the era of data explosion and information availability, it is imperative to consider means to information access for people with visual impairment specially printed information and images [6]. Over the past decades, authors have leveraged state of the art machine learning algorithms to develop solutions supporting each of the aforementioned areas.

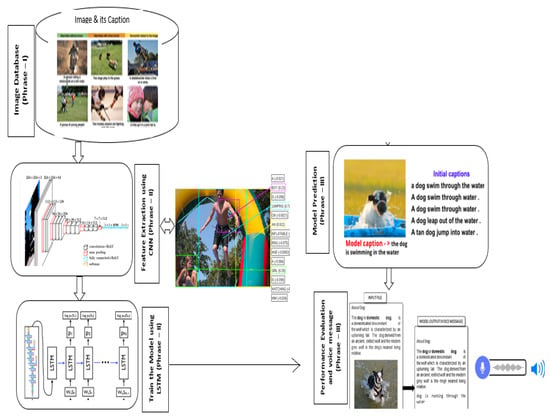

Deep learning has evolved in prominence as a field of study that seeks innovative approaches for automating different tasks depending on input data [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Deep learning is a type of artificial intelligence techniques that can be used for image classification, recognition, virtual assistants, healthcare, authentication systems, natural language processing, fraud detection, and other purposes. The study describes an Intelligent Reader system that employs Deep Learning techniques to help people with visual impairment read and describe images in a printed text book. In the proposed technique, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [19] is utilised to extract features from input images, while Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [20] is used to describe visual information in an image. The intelligent learning system generates a voice message comprising text and graphic information from a printed text book using the text-to-speech approach. Deep learning-based technologies increase image-related task performance and can help people with visual impairment live better lives. The overall architecture of the proposed solution is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Deep Learning Reader Architecture.

The proposed intelligent reader system reads text using optical character recognition (OCR) and the Google Text-to-Speech (TTS) approach, which converts textual input into voice messages. The input images were trained with CNN-LSTM model to predicts the appropriate captions of an image and sends them to the intelligent reader system. The reader system transmits all data to visually impaired users in the form of audio messages. The proposed approach divides into three phrases: acquisition of input images, extracting features for training the deep learning model, and assessing performance. The efficiency of the constructed model is evaluated using different deep learning architectures, including ResNet, AlxeNet, GoogleNet, SqueezeNet, and VGG16. The experimental results suggest that the ResNet network design outperforms other architectures in terms of accuracy.

This paper provides the following contributions. First, it delivers an Electronic Travel Aids (ETA) vision substitution solution for people with visual impairment that includes spatial inputs such as photography or visual content. Although many studies have proposed text-to-speech solutions, this paper utilizes deep learning capabilities to describe images as well as text to a person with visually impairment. Second, it briefs the reader about most significant deep learning architectures for image recognition, along with most identified features of each architecture. Finally, this paper proposes and implements a deep learning architecture utilizing CNN and LSTM algorithms. Content is extracted from text and images with the former algorithm, and a captions are predicted with the latter.

In the recent decades, many researchers have developed an assistive device/system to read text books for people with visual impairment, which helps them enhance their learning skills without the assistance of a tutor. Reading image content is a challenging task for visually impaired students. The proposed system is unique in that it incorporates the intelligence of two deep learning approaches, CNN and LSTM, to assist people with visual impairment in reading a text book (both text and image content) without the assistance of a human. The proposed approach reads the text content in the book using OCR and then provides an audio message. If any images are presented in the text book between the texts, the system uses the CNN model to extract the features of the image, and the LSTM model to describe the captions of the images. Following that, the image captions are translated into voice messages. As a result, visually challenged persons understand the concept of the text book without any ambiguity. The suggested method combines the benefits of OCR, CNN, LSTM, and TTS to read and describe the complete book content through audio/voice message.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 covers previous proposed solutions available for visual impairment. The preliminaries of various architectures in Deep learning approach is explained in Section 3. Then, the empirical findings and model evaluation are detailed in Section 4. We conclude this endeavour in Section 5 with concluding remarks and future work.

2. Related Work

Vision impairment is a common disability with different level of severity. Assistive technology has contributed to providing visual substitution in the form of products, devices, software or systems [21,22,23]. Visual substitution is an alternative means to capture visual images, directions or movements and deliver it in a non-visual manner through audio or Braille [2]. Visual substitution can be categorized into three main categories; namely, Electronic Travel Aids (ETAs), Electronic Orientation Aids (EOAs), and Position Locator Devices (PLDs) [24]. An overview of each category of visual substitution is discussed further.

- Electronic Travel Aids (ETAs)ETAa are devices that translate environment information that are typically identified via human vision, using non-vision sensory. It includes sensing inputs such as a camera, Radio Frequency Identification (RFID), Bluetooth, or Near-Field Communication (NFC), to receive environment inputs, and a feedback modalities to deliver information to the user in a non-vision form such as such as audio, tactile, or vibrations.

- Electronic Orientation Aids (EOAs)EOAs devices provide a navigation path and identify obstacles to people with visual impairment. The objectives of EOAs devices is to improve safety and mobility in unrecognized environment by detecting obstacles and delivering information by means of audio or vibrations [25].

- Position Locator Devices (PLDs)PLDs provide a precise positioning of devices that utilizes Global Positioning System (GPS) and Geographic Information System (GIS). Such technologies have limitation that it ought to be used outdoors and need to be coupled with other sensors to identify obstacles throughout navigation

This paper delivers an ETA vision substitution solution for people with visual impairment. Technological developments, including computer vision and deep and machine learning, are utilized in an autonomous learning system for people with visual impairment.

2.1. AT Based on Deep Learning Techniques

The author in [26] outlined a one-off cheap wearable assistive technology (AT) device running on solar power that provides users with ongoing real-time continuous, real-time object recognition to aid VI individuals.This system comprises three elements: a camera, a system on module (SoM) processing unit, and an ultrasonic sensor. The user wears the camera like a pair of glasses to provide real-time recordings, while the SoM, worn as a belt, processes information from the camera, and the sensor can detect objects. Lin et al. [27] proposed a deep learning-based support system to heighten users’ ability to perceive their surroundings. This system involves a terminal that can be worn and has an earpiece, RGBD camera, and an earphone. A CPU can aid deep learning, and a smartphone is employed whenever touch-based actions are necessary. The system also provides safe, clear walking directives thanks to the RGBD information and semantic maps. In [28], employs deep convolution neural network-based architecture to create a system that detects indoor objects and is based on the “RetinaNet” deep convolution neural network. The assessment of detection levels utilizes different elements, including AlexNet, GoogleNet, ResNet, SqueezeNet, and VGGNet. Applying this system resulted in detection clarity of mean average precision (mAP) 84.61%.

To assist people with visual impairments, Tasnim et al. [29] outlined an automatic process solution to detect Bangladeshi banknotes by way of a convolutional neural network. The research proved successful, as demonstrated by the fact that the system was 92% accurate in specifying the notes and could provide written and audio outputs. The researcher [30] designed a smart glass system for blind and people with visual impairment using computer vision and deep learning algorithms. This proposed approach includes four distinct modules: low-light image enhancement, object detection, audio feedback, and tactile graphics generation. In the first module, a deep learning approach is used to improve the quality of the dark image, and objects/texts are recognized using an object recognition method. Finally, the text to speech module produces an audio output. In this method, the object detection model is trained on 133 different types of sounds. The ExDark data set is used to assess the effectiveness of the proposed approach. Reading books, detecting currency notes, and determining parcel specifics are all challenging tasks for people with visual impairment. Mishra et al. [31] developed ChartVi, an automated chart summarising system that accepts various types of chart images such as line, pie, bar, and so on and generates a summary. The CNN-VGG16 network model is utilised in this approach to identify the chart image categories, and then feature extraction techniques are employed to automatically separate graphical and textual information. The inpainting method removed the grid lines from the chart. Finally, the chart summary is divided into three sections: prime, core, and wrapping. The premier section of the chart comprises the fundamental information about the chart, such as the title, axis titles, and range, among other things, the core part contains the actual meaning of the chart, and the wrapping part contains the details of multi-serious charts. According to the empirical studies, ChartVi achieves 97.09% accuracy in chart type classification, >95% accuracy in textual segmentation, and 98% accuracy in graphical extraction. Consequently, a database containing thousands of images of these banknotes was created. Developments such as these mean blind individuals or those with visual impairments can participate in everyday activities.

2.2. AT Based on Raspberry Pi

According to Zamir et al. [32], a smart reader system informed by the Raspberry Pi can turn text into spoken signals. A camera recognizes printed text thanks to optical character recognition (OCR). This method proposes to create a system that converts images to audio per the Raspberry Pi single-board computer. In [33], the authors presented the unified descriptor network, Dual Desc, that could outperform the NetVLAD architecture in terms of describing images. A wearable device validates real-world information, and the suggested visual localization suggestions employ multimodal images to avoid any issues associated with RGB photos.The author [34] developed a voice mentor system that reads content such as books, currency notes, and shopping parcels and provides audio output to the user. The Raspberry Pi is deployed in this approach to support the portable camera and audio signals through headphones. To extract text from images and transform the text to audio, optical character recognition (OCR) is used. Chauhan et al. [35] use a Raspberry Pi 3B model and ultrasonic sensors to create Ikshana, an intelligent assistive device for vision impaired users. This device is designed to help people with a variety of daily chores including as character recognition, facial detection, currency denomination identification, and obstacle detection. OCR software is used to extract text from printed books and internet content. The assisting device’s design includes a Raspberry Pi 3B model as the computing unit, a Raspberry Pi camera, buttons, and ultrasonic sensors. The headphone acts as a narrative agent, directing the audio output to the user.

A smart electronic assistive device, consisting of two gadgets such as glasses and a smart cane, is designed by Flores et al. [36]. The glasses utilise an image processing technique to recognise text, while the smart cane detects obstacles in the walking path by using sensors named VL53L0X and Ultrasonic. The developed device achieves 100% accuracy in obstacle detection, 98.13% accuracy in text recognition, and 91.33% accuracy in natural scene identification.

2.3. AT Based on Internet of Things (IoT)

The author [37] developed an intelligent assistive system based on machine learning and Internet of Things (IoT) to recognise people with visual impairment’s acquaintances in their regular activities. The author built the proposed system using three major technologies: machine learning, image processing, and IoT. In this system, the data ingestion layer is used to store input images, while the data analysis layer analyses processed data and evaluates the system’s accuracy and efficiency using machine learning. Finally, the application layer builds a mobile app that may be used to detect a new individual whose face samples must be saved in the cloud and that gives haptic response to the person with visual impairment when an acquaintance is detected.The researcher [38] created an IoT-based automatic object identification system that can recognise objects and currency notes in real time. This system employs four kinds of sensors to detect obstructions in the front, left, right, and floor directions. To detect the currency note, the Single Shot Detector (SSD) model using MobileNet and Tensorflow-lite is utilised. There were 365 people with visual impairment evaluated with this technology, and 82% of them thought the cost was acceptable, 13% thought it was moderate, and the remaining 5% thought it was relatively high. The proposed system’s overall accuracy in object identification and recognition is 99.31% and 98.43%, respectively.

2.4. Image Captioning Techniques

Image captioning technique is utilised in a wide range of applications, including bridge damage detection, remote sensing image captioning, language caption synthesis, and construction. Chun et al. [39] used an image captioning technique to describe the damage state of a bridge. A deep learning model is used in this work to produce descriptive sentences from an image. This method can also detect many types of damage in bridge images and provide a full interpretation of complicated imagery. The real time dataset is created during inspection work on 3118 bridges controlled by Japan’s Kanto Regional Development Bureau’s MLIT from 2004 to 2018. The developed technique uses the Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU) score to evaluate the algorithm’s performance. The proposed method achieves 69.3% accuracy for accurately generating explanatory phrases that give user-friendly, text-based descriptions of bridge damage in images. The researcher [40] used Meta captioning to develop a remote sensing image captioning system. The Meta characteristics are extracted from two tasks in this approach: remote sensing classification and natural image classification. Because of the scarcity of training dataset, effective remote sensing image captioning is extremely difficult. The Meta features are then employed for remote sensing image captioning. The ResNet network is used to train natural image categorization. To illustrate the efficiency of the Meta captioning framework, three distinct remote sensing captioning datasets were employed in the experimental analysis: Sydney-Captions, the Remote Sensing Image Captioning Dataset, and the University of California Merced dataset.

In [41], an integrated approach for extracting semantic information about items, behaviours, and interactions from construction images with visual links was devised. In this approach, the CNN model is used to extract the prominent features from the entire image, and the Mask R-CNN-based Encoder model is used to forecast the image’s description words based on the input features. To train the model, 41,668 images were collected from 174 distinct construction sites and divided into training and validation sets. According to the results of the experimental analysis, the proposed method produces BLEU Scores of 0.61, 0.52, 0.44, and 0.36 for BLEU1, BLEU2, BLEU3, and BLEU4, respectively. Afyouni et al. [42] developed AraCap, an Arabic Image Caption Generation approach that combines an object-based and image captioning framework. The COCO and Flickr30k datasets are used to assess the method’s performance. The proposed method includes the object detection and image captioning processes in a sequential order. Using a similarity score, the proposed approach generates captions that are compared to original captions from public databases. The results show that the similarity scores of the proposed models for Arabic generated captions surpassed the basic captioning technique. The remote sensing captioning model was constructed [43] utilising a Variational Autoencoder and a Reinforcement Learning-based Two-stage Multi-task Learning Model (VRTMM). CNN is used in this method to extract both semantic and spatial characteristics from an image. Then, Reinforcement Learning is used to improve the quality of the generated phrases. To identify the remote sensing image scene, a publicly accessible Remote Sensing Image dataset of 31,500 images and 45 scene classifications was used. The results of the experiments illustrate that the proposed model is successful at remote sensing image captioning and produces a new state-of-the-art outcome.

Table 1 illustrates the learning approach employed in recent studies designed for people with visual impairment.

Table 1.

Summarization of the Related works.

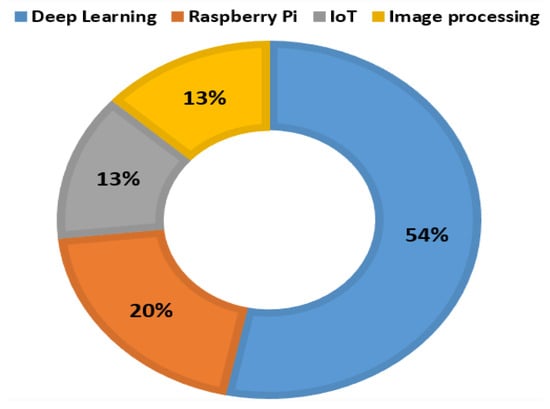

Figure 2 depicts a summary of relevant literature. Recently, new innovations in the field of assistive technology have emerged, providing excellent assistance to people with visual impairment in a variety of ways. According to the above literature, 54% of researchers applied deep learning and artificial intelligence approaches to design an assistive device or system. The key advantage of these systems is that they are mobile apps, making it very easy for the user to utilise them. The figure also depicts that, 23% of assistive devices are Rasberry Pi and IoT based hardware devices. The remaining 23% of researchers analyses the image captioning methods using deep learning. The significant applications of the literature discussed above include text recognition, currency note identification, bridge damage detection, language prediction, remote sensing image captioning and facial recognition. It is extremely difficult for visually challenged persons to comprehend image information presented in textbooks, articles, and online advertisements. To overcome these limitations, the proposed system uses deep learning algorithms to provide image information in the form of audio output.

Figure 2.

Related Literature Summary.

3. Preliminaries

Deep learning is a type of machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) that that models the learning of data. This approach helps academic researchers to gather, assess, and decipher substantial reams of information because it streamlines and quickens the process.

A vast amount of research has been conducted in the field of computer vision in recent decades. Image classification, image segmentation, video tracking, pedestrian identification, object detection, and many other applications are examples of computer vision applications. One of the most essential computer vision techniques is object detection, which is used to discover and locate objects/obstacles inside an image or video. Object identification approaches include drawing bounding boxes and representing various things of interest in a given image. Several deep learning variations based on artificial neural networks have been employed such as Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and Long Short Term Memory (LSTM), where different architectures plays an important role in different applications [47].

3.1. Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)

Multilayer Perceptron is a feed-forward artificial neural network algorithm which has input, output and one or more hidden layers [48]. The perceptron can use Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) [49] activation function or Sigmoid that combined with the initial weights in a weighted sum for prediction. In the fully connected layer of MLP, all the nodes are connected with the next and previous layer. There are many applications of multi-layer perceptron such as speech recognition, pattern recognition, sentiment analysis, etc.

3.2. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

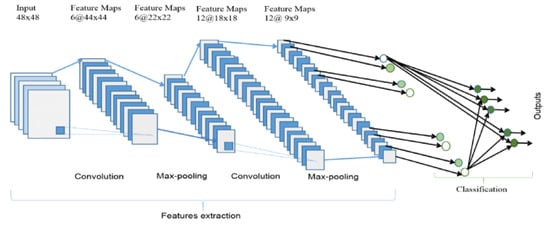

CNN [50] can be defined as a kind of deep learning neural network that has aided the development of classifying and recognizing images. The CNNs are composed of several different basic layers followed by the activation layers. A CNN is made up of three layers: a convolutional layer, a pooling layer, and a fully connected layer. The Convolutional layer involves a procedure wherein a succession of layers retrieve low- to high-level features from the input layer. Meanwhile, the fully connected layer utilizes the Softmax Classification method to calculate and arrange the class label scores. The pooling layer is responsible for reducing the convoluted features’ spatial dimensions. This pooling comprises two kinds: average pooling and maximum pooling. The former provides an average of each value from the part of the image within the kernel’s boundaries, while the latter returns the topmost value. The fully connected (FC) layer performs classification using the characteristics retrieved by the previous layers and their various filters. FC layers typically use a softmax activation function to classify inputs, yielding a probability ranging from 0 to 1. Figure 3 shows the CNN architecture.

Figure 3.

CNN Architecture [51].

Numerous CNN architectures, such as Alexnet [52], VGG16 [53], Squeezenet [54], ResNet [55], and GoogLeNet [56], have emerged in recent years, with many differences in terms of layer types, hyper-parameters, and so on. The most significant predefined networks are discussed in this article.

3.3. CNN-AlexNet

AlexNet is a pioneering architecture in the field of computer vision. This model takes images with dimensions of 227 × 227 × 3 as input. As the number of filters increases, the model is trained deeper and more features are extracted. In addition, the filter size is decreasing, implying that the original filter is becoming smaller. RGB images are sent into the deep learning model’s input. Softmax is the activation function utilised in the output layer [52].

3.4. CNN-VGG16

The VGG16 is a typical convolution neural network (CNN) architecture developed by Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman of the University of Oxford. The architecture’s performance is assessed using the ImageNet dataset [57], which obtained 92.7 percent top-5 test accuracy in 2014. In comparison to AlexNet, VGG16 employs huge kernel-sized filters. The architecture’s input image dimensions are set at 244 × 244 × 3. All of the hidden layers in this network are followed by the ReLu activation function. Finally, the softmax layer serves as the output layer [53].

3.5. CNN-GoogLeNet

The primary goal of the Inception architectural model is to use less computational resource by altering earlier Inception designs. The initial version of the inception model is called “GoogLeNet”, and it has 22 layers. These networks have learnt several feature representations for a variety of images. The network’s input dimensions are 224 × 224 × 3. The GoogLeNet architecture differs from prior designs such as AlexNet and VGG16 in that it uses global average pooling to generate deeper architecture. Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) is used as activation functions in this architecture’s convolutions [56].

3.6. CNN-ResNet

Deep neural networks need more time to train the model and are more prone to overfitting. To overcome these shortcomings, Microsoft launched ResNet, a residual learning framework that improves the training of networks that are far deeper and relatively simple to grasp than those previously employed. Every few stacked levels in this network design directly suit a required underlying mapping [55].

3.7. CNN-SqueezeNet

SqueezeNet is a smaller neural network that was created to be a more compact alternative for AlexNet. This architecture has 50x less parameters than AlexNet and performs 3× quicker. It used ReLU activation in all squeeze and expand layers [54].

Table 2 describes the 3D depiction of each deep learning network architecture. TensorSpace (https://tensorspace.org/index.html (accessed on 15 October 2022)) is an interactive visualization tool that exposes data connections between network layers.

Table 2.

Visualization of Deep Learning Architectures.

3.8. Long Short Term Memory (LSTM)

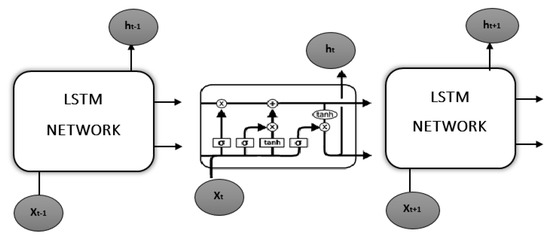

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [58] networks are Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) that have the capacity to grasp order dependency in sequence prediction scenarios. RNN is a feed-forward neural network characterized by its internal memory. In this network, the current stage involves the output of the preceding step acting as an input: after its generation, the output undergoes replication and is returned to the RNN. During the decision-making process, the network assesses information about the input and output it acquired from the previous input and helps identify the order of the images. LSTM networks can be used in different contexts, including activity recognition, grammar learning, handwriting identification, human action detection, picture description, rhythm learning, time series prediction, voice recognition, and video description. Figure 4 illustrates the LSTM architecture.

Figure 4.

LSTM Network Architecture [59].

LSTM networks comprise numerous memory blocks, otherwise referred to as cells and illustrated in the image as rectangles. These blocks take responsibility for recording information, and modifying this information occurs using one of four gate methods. LSTMs handle Short-Term Memory (STM) and Long-Term Memory (LTM), while the gates aim to streamline the computation process. In this instance, the LTM moves to the forget gate, where it loses data that does not serve a purpose: conversely, the learn gate makes it possible to grasp data from the STM, and the remember gate amends LTM data and brings it up to date, and the use gate forecasts the output of the current event.

4. The Proposed CNN-LSTM Design

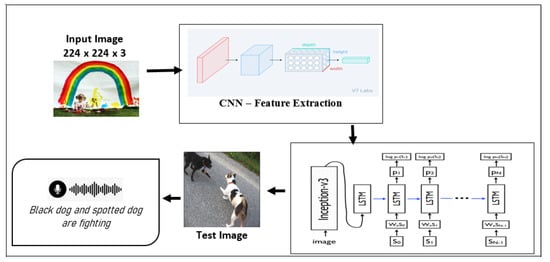

The proposed approach involves feeding the input file into the intelligent reader system, which utilizes an Optical Character Recognition (OCR) tool that scrutinizes the file’s contents and Google Text-to-Speech (TTS) technique adapts written input into voice responses. When a file has images, the trained CNN-LSTM model predicts the related captions, which are forwarded to the intelligent reader system. The reader system passes on all data in the form of voice messages. The proposed system is divided into three phases: collecting input images, extracting features for training the deep learning model, and evaluating performance. Such an approach aims to ease concerns over predicting sequences, including spatial inputs such as photography or visual content. Figure 5 depicts the suggested CNN-LSTM model’s architecture.

Figure 5.

CNN-LSTM Design.

Phase 1 (Input Image Collection): The input images are collected and preprocessed. In this research, Flickr 8K dataset, which comprises images and associated human descriptions, is utilised for model training.

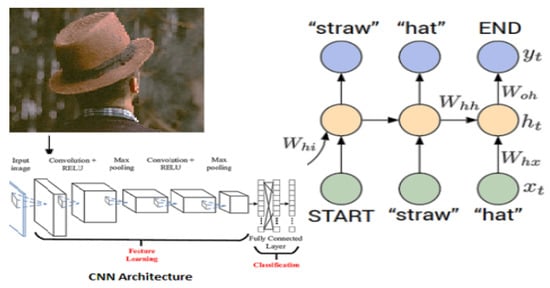

Phase 2 (Model Training): It consists of two main parts: feature extraction and a language prediction model built with two deep learning techniques: Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Long Short Term Memory (LSTM). CNN is a sub component of the Deep Learning approach and customized deep neural networks that are used for image classification and recognition. Images in CNN model are represented as a 2D matrix that can be scaled, translated, and rotated. The CNN model analyses the images from top to bottom and left to right, extracting salient features for image categorization. In this network architecture the convolutional layer with 3 × 3 kernels is utilised for feature extraction with ReLU active function. To minimise the dimensions of an input picture, the max-pooling layer with a size of 2 × 2 kernels is utilised. The extracted features will be put into the LSTM model, which will provide the image caption. LSTM is a subsection of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) that was created to solve sequence prediction issues. The output from the last hidden state of the CNN (Encoder) is fed as the input of the decoder. Let = <START> vector and the required label = first word in the sequence. In the same way consider = word vector of the first word and expect the network to identify the next word. Lastly, = last word, and = <END> token. The visualization of language prediction model is depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Language Prediction Model.

The language model takes the image pixels i and the input word vectors is denoted as (,,…,), and determines the series of hidden states (,,…,) that produce the outputs (,,…,). As the initial hidden state ht, the image feature vectors are only transmitted once. As a result, the image vector I the previously hidden state , and the current input are used to determine the next hidden state. A softmax layer is used on the specified hidden state activation function to generate the current output .

The CNN-LSTM is a deep learning architecture that combines two algorithms: CNN and LSTM. The salient features of the input images are extracted to predict sequences, and the latter predicts captions. The developed deep network model is evaluated using various architectures including ResNet, AlexNet, GoogleNet, SqueezeNet, and VGG16. Phase 3 (Testing): In phase 3, the trained model is tested using the test dataset. The CNN-LSTM model predicts the caption sequence from the test image. The proposed approach’s efficiency is determined using metrics such as BLEU, precision, recall, and accuracy. Using Google Text-to-Speech API, the output captions are turned into audio messages. The intelligent reader system based on deep learning enables people with visual impairment to easily understand text as well as images displayed in text content.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Dataset Collection

In this research, the Flickr8k dataset [60,61] is employed to train the model. Flickr8k Dataset, which contains 8092 images, and each is annotated with 5 sentences using Amazon Mechanical Turk.The annotations on each image allow for progress in automatic image description and grounded language understanding. Flickr8k Text file, which contains image names and captions. For training, the deep learning model dataset is divided into three parts: 80%, 10%, and 10% for training, validation, and testing, respectively. Table 3 shows a sample image with a caption.

Table 3.

Sample Image and Description.

5.2. Results and Discussion

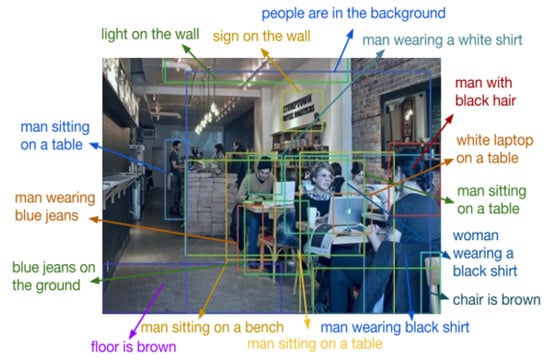

The training process involved feeding the dataset, which was the input, into the model. This research employed CNN and LSTM to ascertain an image’s caption: CNN withdrew the features, and an LSTM-trained model came up with the caption. Post-training, the model should accept the image, which subsequently summarizes the content. The trained model helps capture the information encoded in the image, as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Image Description presented using Trained Model [61].

As a consequence of the parameter analysis, several metrics were investigated, including input image size, activation function, developer name and year of creation, and top-5 error rate. Table 4 depicts the input parameter values. In this table the input image size of AlexNet is 227 × 227 × 3, while the remaining network architecture is 224 × 224 × 3. The activation function is used to find the output of the neural network that contains several activation functions such as sigmoid, tanh, relu, softmax, and so on. In this article, AlexNet and VGG16 employed the softmax activation function, whereas the others used Relu activation. When compared to other algorithms, ResNet has the lowest error rate. In the empirical analysis, the batch size and epochs were set to 512 and 200, respectively.

Table 4.

Parameter Values of Proposed Method.

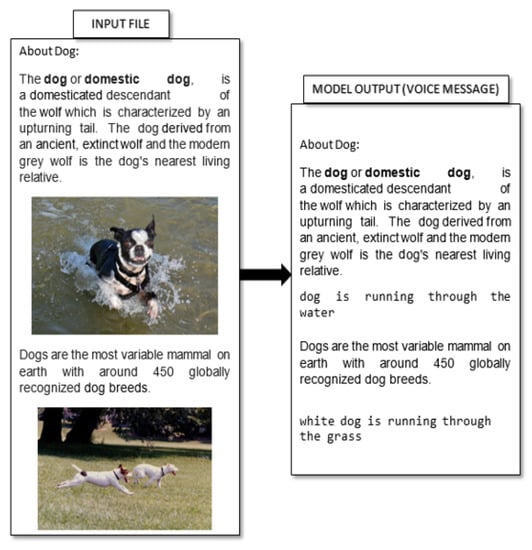

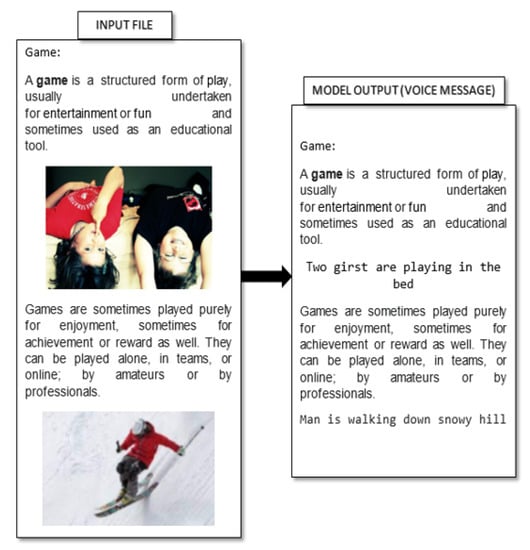

The suggested approach features a document comprising words and images: the LSTM model predicts the caption, and a voice message disseminates all relevant data. Figure 8 and Figure 9 demonstrates the output of the proposed deep learning reader.

Figure 8.

Deep learning Reader Output 1.

Figure 9.

Deep learning Reader Output 2.

BiLingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU) [62] evaluates the performance levels of the image captioning system and carries out an investigation of the n-gram correlation between the reference translation statement and the translation statement under consideration. BLEU score is computed using the following equation,

where,

is the count of i-gram in candidate matching the reference translation,

is the count of i-gram in the reference translation,

is the total number of i-grams in candidate tanslation.

A higher BLEU score indicates correspondingly high performance levels. Table 5 features the 1- and 2-gram BLEU scores for the AlexNet, GoogleNet, ResNet, SqueezeNet, and VGG16 networks. Studies have found that the ResNet network architecture exceeds the other networks’ performance levels.

Table 5.

BLEU Score Values.

Table 6 summarises the performance of the proposed framework and the other image captioning approaches presented in the related work section. Image captioning is used in a variety of applications such as bridge damage detection, remote sensing image captioning, language caption synthesis, constructions, and so on. According to the table, the BLEU score values for construction image captioning method, remote sensing image captioning method, and Arabic Image Caption Generation were 0.56, 0.77, and 0.81, respectively. For describing the image caption, the proposed method used various Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) pre-trained networks such as AlexNet, GoogleNet, ResNet, SqueezeNet, and VGG16. The empirical results show that the proposed CNN–ResNet network model achieves a higher BLEU score value than other network models and existing image captioning approaches.

Table 6.

The Performance Comparison with Existing Approaches.

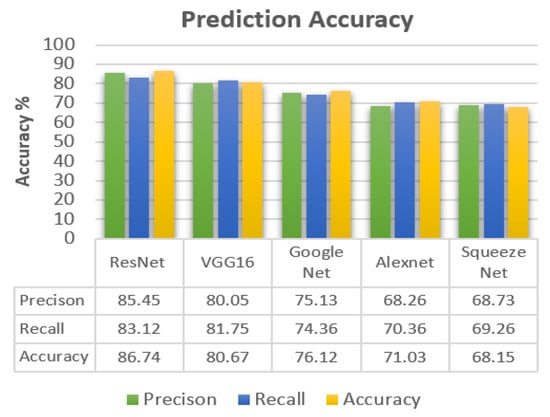

The suggested CNN-LSTM algorithm’s efficiency is assessed using evaluation metrics such as precision, recall, and accuracy.Precision is the number of correct class predictions that belong to the same class. The number of actual predictions made out of all the classes in the data set is denoted as recall. Model accuracy relates to the ability to choose the best model based on training data, and it is defined as follows:

To evaluate the correctness of the predicted images captions, it is compared against the caption of the tagged images. In this empirical analysis, true positive means that the predicted model accurately predicts image captions that are tagged positive captions in the class labels. True negatives indicate that the predicted model properly predicts image captions with negative tags in the class labels. A false positive is an outcome in which the model forecasts the positive class inaccurately. Similarly, false negative is an output in which the model predicts negative captions incorrectly. The ResNet network performs better than the existing architectures. The next step in the methodology employ text-to-speech to vocally narrate the data for people with visual impairment. Figure 10 demonstrates the evaluation metric values for several architectures such as Alexnet, GoogleNet, SqueezeNet, VGG16, and ResNet.

Figure 10.

Prediction Accuracy.

According to the experimental results, ResNet has the highest precision value of 85.45%, while Alexnet has the lowest precision value of 68.26%. In terms of recall, squeezeNet has the lowest recall value of 69.26%, while ResNet has the highest precision value of 83.12%. ResNet architecture has the highest overall accuracy of 86.74% when compared to other network architectures. The empirical results indicate that the CNN-LSTM model with ResNet network architecture outperforms the image caption prediction.

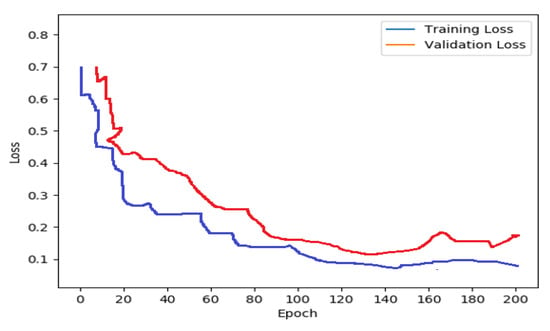

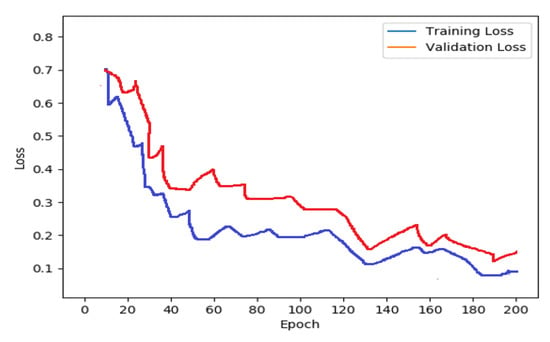

In this experimental analysis, the model is trained with 200 epochs. The training and validation loss for the AleNet architecture is depicted in the Figure 11. The lost accuracy start at 0.7 and gradually decreased to an average value of 0.2.

Figure 11.

Training and Validation loss (Alexnet).

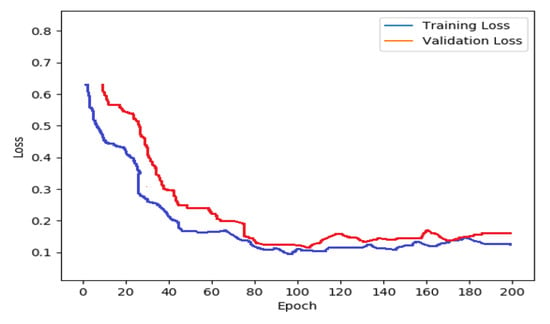

Figure 12 demonstrates the training and validation loss for GoogleNet architecture. According to the GoogleNet training and validation graph, the loss value starts at 0.6 and ends at 0.25, indicating that the network performs lower for image caption prediction.

Figure 12.

Training and Validation loss (GoogleNet).

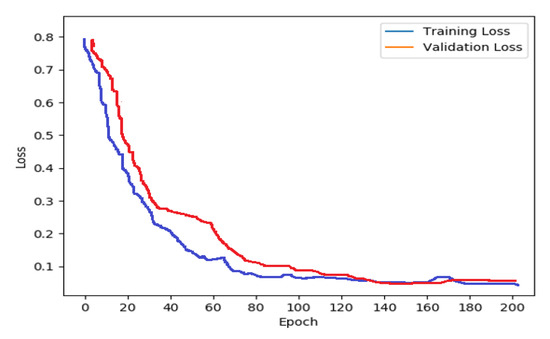

Figure 13 demonstrates the training and validation loss of the ResNet architecture. According to this figure, the loss rate started at 0.8 and gradually decreased below 0.1 after the 80th epoch. When compared to other networks architectures, the ResNet produces better accuracy and a lower loss rate.

Figure 13.

Training and Validation loss (ResNet).

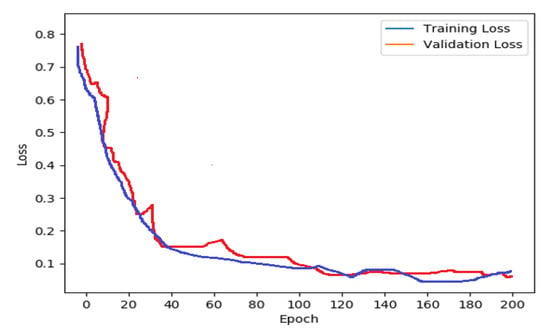

The loss rate for the VGG16 network architecture started at 0.75 and ended at 0.2 and it is shown in Figure 14. It is believed that the loss rate for both training and validation seems to be the same. It is also important to note that the training loss rate is impressed in a smooth manner, with no ups and downs.

Figure 14.

Training and Validation loss (VGG16).

Finally, Figure 15 shows the SqueezNet training and validation graph. In this figure, both curves are deviated with high values, indicating that it produce less performance for image caption prediction. The graphs confirms a proven decrease in loss across the different tested models as the number of epochs increases during validation and training which represents a better learning capability of the models.

Figure 15.

Training and Validation loss (SqueezNet).

The experimental results show that the SqueezNet network has a very high loss rate, implying that it produces less efficiency than the other networks. In comparison of ResNet and Vgg16 networks, ResNet produce superior and lower loss rates. Similarly, when compared to other networks, GoogleNet has an average loss rate. The ResNet design is thought to better match the training data and forecast the incoming data.

6. Conclusions

This work involves generating a deep learning-based intelligent system to assist individuals with visual impairments. The system comprises entering text and images from coursebooks: CNN extricates the relevant data, and LSTM specifies the visual input. Users receive the data in the form of voice messages that use the text-to-speech module. The Alexnet, GoogleNet, ResNet, SqueezeNet, and VGG16 networks train the LSTM model. According to research, the LSTM-based training model provides the most suitable image descriptions and predictions.

An intelligent system means individuals with visual impairments can easily comprehend text and images, although limitations exist, such as requiring the use of the Flicker8k dataset to provide image data. Subsequent studies will utilize transfer learning to refine descriptions of images based on real-time photos and their descriptive content.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G., A.T.A. and N.A.K.; Data curation, S.A., B.Q. and A.E.H.; Formal analysis, J.G., A.T.A., S.A., N.A.K., B.Q. and A.E.H.; Investigation, A.T.A., S.A., N.A.K., B.Q. and A.E.H.; Methodology, J.G., A.T.A., S.A., N.A.K., B.Q. and A.E.H.; Resources, J.G., S.A., B.Q. and A.E.H.; Software, J.G. and N.A.K.; Supervision, A.T.A.; Validation, A.T.A., S.A., B.Q. and A.E.H.; Visualization, J.G., N.A.K., B.Q. and A.E.H.; Writing—original draft, J.G., A.T.A., S.A. and N.A.K.; Writing—review & editing, J.G., A.T.A., S.A., N.A.K., B.Q. and A.E.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for supporting this work. Special acknowledgement to Automated Systems & Soft Computing Lab (ASSCL), Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Triantafyllidis, A.K.; Tsanas, A. Applications of machine learning in real-life digital health interventions: Review of the literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjari, K.; Verma, M.; Singal, G. A survey on assistive technology for visually impaired. Internet Things 2020, 11, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Took, C.C.; Seong, J.K. Machine learning in biomedical engineering. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2018, 8, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, E.; Ballerini, L.; Hernandez, M.d.C.V.; Chappell, F.M.; González-Castro, V.; Anblagan, D.; Danso, S.; Muñoz-Maniega, S.; Job, D.; Pernet, C.; et al. Machine learning of neuroimaging for assisted diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s Dementia Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2018, 10, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swenor, B.K.; Ramulu, P.Y.; Willis, J.R.; Friedman, D.; Lin, F.R. The prevalence of concurrent hearing and vision impairment in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 312–313. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick, A.; Hazarika, S.M. An insight into assistive technology for the visually impaired and blind people: State-of-the-art and future trends. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2017, 11, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.H.; Lee, Y.J. Evaluation of medication use and pharmacy services for visually impaired persons: Perspectives from both visually impaired and community pharmacists. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Duan, Y.; Kang, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, F.Y. Traffic flow prediction with big data: A deep learning approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2014, 16, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, R. Foundations of Orientation and Mobility; Technical Report; American Printing House for the Blind: Louisville, KY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, B.D.C.; Villegas, O.O.V.; Sánchez, V.G.C.; Jesús Ochoa Domínguez, H.d.; Maynez, L.O. Visual perception substitution by the auditory sense. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Santander, Spain, 20–23 June 2011; pp. 522–533. [Google Scholar]

- Dakopoulos, D.; Bourbakis, N.G. Wearable obstacle avoidance electronic travel aids for blind: A survey. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Part C (Appl. Rev.) 2009, 40, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Song, F.; Clark, B.C.; Grooms, D.R.; Liu, C. A wearable device for indoor imminent danger detection and avoidance with region-based ground segmentation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 184808–184821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkholy, H.A.; Azar, A.T.; Magd, A.; Marzouk, H.; Ammar, H.H. Classifying Upper Limb Activities Using Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision, Cairo, Egypt, 8–10 April 2020; pp. 268–282. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, N.A.; Azar, A.T.; Abbas, N.E.; Ezzeldin, M.A.; Ammar, H.H. Experimental Kinematic Modeling of 6-DOF Serial Manipulator Using Hybrid Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision, Cairo, Egypt, 8–10 April 2020; pp. 283–295. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, H.A.; Azar, A.T.; Ibrahim, Z.F.; Ammar, H.H.; Hassanien, A.; Gaber, T.; Oliva, D.; Tolba, F. A Hybrid Deep Learning Based Autonomous Vehicle Navigation and Obstacles Avoidance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision, Cairo, Egypt, 8–10 April 2020; pp. 296–307. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, A.S.; Azar, A.T.; Ibrahim, Z.F.; Ibrahim, H.A.; Mohamed, N.A.; Ammar, H.H. Deep Learning Based Kinematic Modeling of 3-RRR Parallel Manipulator. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision, Cairo, Egypt, 8–10 April 2020; pp. 308–321. [Google Scholar]

- Azar, A.T.; Koubaa, A.; Ali Mohamed, N.; Ibrahim, H.A.; Ibrahim, Z.F.; Kazim, M.; Ammar, A.; Benjdira, B.; Khamis, A.M.; Hameed, I.A.; et al. Drone Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Review. Electronics 2021, 10, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubâa, A.; Ammar, A.; Alahdab, M.; Kanhouch, A.; Azar, A.T. DeepBrain: Experimental Evaluation of Cloud-Based Computation Offloading and Edge Computing in the Internet-of-Drones for Deep Learning Applications. Sensors 2020, 20, 5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Dong, J.; Li, H.; Gao, Y. Simple convolutional neural network on image classification. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Big Data Analysis (ICBDA), Beijing, China, 10–12 March 2017; pp. 721–724. [Google Scholar]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, A.; Ogunfunmi, T. Developing a deep learning-enabled guide for the visually impaired. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), Seattle, WA, USA, 29 October–1 November 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tapu, R.; Mocanu, B.; Zaharia, T. Wearable assistive devices for visually impaired: A state of the art survey. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2020, 137, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swathi, K.; Vamsi, B.; Rao, N.T. A Deep Learning-Based Object Detection System for Blind People. In Smart Technologies in Data Science and Communication; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, A.S.; Gubbi, J.; Palaniswami, M.; Wong, E. A vision-based system to detect potholes and uneven surfaces for assisting blind people. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 23–27 May 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, V.N.; Nguyen, T.H.; Le, T.L.; Tran, T.T.H.; Vuong, T.P.; Vuillerme, N. Obstacle detection and warning for visually impaired people based on electrode matrix and mobile Kinect. In Proceedings of the 2015 2nd National Foundation for Science and Technology Development Conference on Information and Computer Science (NICS), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 16–18 September 2015; pp. 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, B.; Velázquez, R.; Del-Valle-Soto, C.; de Fazio, R.; Giannoccaro, N.I.; Visconti, P. Solar-Powered Deep Learning-Based Recognition System of Daily Used Objects and Human Faces for Assistance of the Visually Impaired. Energies 2020, 13, 6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, K.; Yi, W.; Lian, S. Deep learning based wearable assistive system for visually impaired people. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Seoul, Korea, 27–29 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Afif, M.; Ayachi, R.; Said, Y.; Pissaloux, E.; Atri, M. An evaluation of retinanet on indoor object detection for blind and visually impaired persons assistance navigation. Neural Process. Lett. 2020, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, R.; Pritha, S.T.; Das, A.; Dey, A. Bangladeshi Banknote Recognition in Real-Time Using Convolutional Neural Network for Visually Impaired People. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Robotics, Electrical and Signal Processing Techniques (ICREST), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 5–7 January 2021; pp. 388–393. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhiddinov, M.; Cho, J. Smart glass system using deep learning for the blind and visually impaired. Electronics 2021, 10, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Kumar, S.; Chaube, M.K.; Shrawankar, U. ChartVi: Charts summarizer for visually impaired. J. Comput. Lang. 2022, 69, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamir, M.F.; Khan, K.B.; Khan, S.A.; Rehman, E. Smart Reader for Visually Impaired People Based on Optical Character Recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Technologies and Applications, Bahawalpur, Pakistan, 6–8 November 2019; pp. 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, R.; Hu, W.; Chen, H.; Fang, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, Z.; Bai, J. Hierarchical visual localization for visually impaired people using multimodal images. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 165, 113743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahithi, P.; Bhavana, V.; ShushmaSri, K.; Jhansi, K.; Madhuri, C. Speech Mentor for Visually Impaired People. In Smart Intelligent Computing and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 441–450. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, S.; Patkar, D.; Dabholkar, A.; Nirgun, K. Ikshana: Intelligent Assisting System for Visually Challenged People. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC), Trichy, India, 7–9 October 2021; pp. 1154–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, I.; Lacdang, G.C.; Undangan, C.; Adtoon, J.; Linsangan, N.B. Smart Electronic Assistive Device for Visually Impaired Individual through Image Processing. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 13th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment, and Management (HNICEM), Manila, Philippines, 28–30 November 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Aravindan, C.; Arthi, R.; Kishankumar, R.; Gokul, V.; Giridaran, S. A Smart Assistive System for Visually Impaired to Inform Acquaintance Using Image Processing (ML) Supported by IoT. In Hybrid Artificial Intelligence and IoT in Healthcare; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.A.; Sadi, M.S. IoT enabled automated object recognition for the visually impaired. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Update 2021, 1, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, P.J.; Yamane, T.; Maemura, Y. A deep learning-based image captioning method to automatically generate comprehensive explanations of bridge damage. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2022, 37, 1387–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ni, Z.; Ren, P. Meta captioning: A meta learning based remote sensing image captioning framework. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 186, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, B.; Bouferguene, A.; Al-Hussein, M.; Li, H. Vision-based method for semantic information extraction in construction by integrating deep learning object detection and image captioning. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 53, 101699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afyouni, I.; Azhar, I.; Elnagar, A. AraCap: A hybrid deep learning architecture for Arabic Image Captioning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 189, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, M. Remote sensing image captioning via Variational Autoencoder and Reinforcement Learning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 203, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denić, D.; Aleksov, P.; Vučković, I. Object Recognition with Machine Learning for People with Visual Impairment. In Proceedings of the 2021 15th International Conference on Advanced Technologies, Systems and Services in Telecommunications (TELSIKS), Nis, Serbia, 20–22 October 2021; pp. 389–392. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, S.M.; Kumar, S.; Veeramuthu, A. A smart personal AI assistant for visually impaired people. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), Tirunelveli, India, 11–12 May 2018; pp. 1245–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Durgadevi, S.; Thirupurasundari, K.; Komathi, C.; Balaji, S.M. Smart Machine Learning System for Blind Assistance. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Power, Energy, Control and Transmission Systems (ICPECTS), Chennai, India, 10–11 December 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Koubaa, A.; Azar, A.T. Deep Learning for Unmanned Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, M.C.; Balas, V.E.; Perescu-Popescu, L.; Mastorakis, N. Multilayer perceptron and neural networks. WSEAS Trans. Circuits Syst. 2009, 8, 579–588. [Google Scholar]

- Agarap, A.F. Deep learning using rectified linear units (relu). arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.08375. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alom, M.Z.; Taha, T.M.; Yakopcic, C.; Westberg, S.; Sidike, P.; Nasrin, M.S.; Hasan, M.; Van Essen, B.C.; Awwal, A.A.; Asari, V.K. A state-of-the-art survey on deep learning theory and architectures. Electronics 2019, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Iandola, F.N.; Han, S.; Moskewicz, M.W.; Ashraf, K.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and< 0.5 MB model size. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07360. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, A. Long short-term memory. In Supervised Sequence Labelling with Recurrent Neural Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S. Understanding LSTM Networks, Volume 11. 2015. Available online: https://colah.github.io/posts/2015-08-Understanding-LSTMs/ (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Hodosh, M.; Young, P.; Hockenmaier, J. Framing image description as a ranking task: Data, models and evaluation metrics. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2013, 47, 853–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Karpathy, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Densecap: Fully convolutional localization networks for dense captioning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 4565–4574. [Google Scholar]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. Bleu: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 7–12 July 2002; pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).