Abstract

Data are an important part of machine learning. In recent years, it has become increasingly common for researchers to study artificial intelligence-aided design, and rich design materials are needed to provide data support for related work. Existing aesthetic visual analysis databases contain mainly photographs and works of art. There is no true logo database, and there are few public and high-quality design material databases. Facing these challenges, this paper introduces a larger-scale logo database named JN-Logo. JN-Logo provides 14,917 logo images from three well-known websites around the world and uses the votes of 150 graduate students. JN-Logo provides three types of annotation: aesthetic, style and semantic. JN-Logo’s scoring system includes 6 scoring points, 6 style labels and 11 semantic descriptions. Aesthetic annotations are divided into 0–5 points to evaluate the visual aesthetics of a logo image: the worst is 0 points; the best is 5 points. We demonstrate five advantages of the JN-Logo database: logo images as data objects, rich human annotations, quality scores for image aesthetics, style attribute labels and semantic description of style. We establish a baseline for JN-Logo to measure the effectiveness of its performance on algorithmic models of people’s choices of logo images. We compare existing traditional handcrafted and deep-learned features in both the aesthetic scoring task and the style-labeling task, showing the advantages of deep learning features. In the logo attribute classification task, the EfficientNet _B1 model achieved the best results, reaching an accuracy of 0.524. Finally, we describe two applications of JN-Logo: generating logo design style and similarity retrieval of logo content. The database of this article will eventually be made public.

1. Introduction

In recent years, intelligent design has become a new dimension of design practice and academic research. Intelligent design system-assisted design, such as intelligent poster design, photo classification and intelligent logo design, has gradually become popular, bringing more possibilities to the design industry. However, there are few public databases that include design materials such as posters, web pages and logos, so related technologies use photo databases and personal databases. This is inconvenient for researchers. In 2020, Wu et al. [1] in China explored new next-generation artificial intelligence technology including deep learning and proposed a next-generation artificial intelligence plan. The reference exemplifies the need for data and accurate expert annotation knowledge for deep learning. It was confirmed that a database with high-quality annotation knowledge has high research value. On 8 July 2021, at the World Artificial Intelligence Conference (WAIC 2021), the digital creative intelligent design engine proposed by the Alibaba–Zhejiang University Frontier Technology Joint Research Center summarized the model construction of a media carrier that organically integrates design theory and computing. The research content involves the interdisciplinary topics of artificial intelligence and design, such as design semantic annotation, image generation, graphic style learning and aesthetic computing. It can be seen that the computational method of intelligent design urgently needs a large-scale public database of design materials.

As researchers committed to solving this problem, we introduce a new visual analysis database of logo image aesthetics named JN-Logo that combines and improves aesthetic analysis.

The data and labels for the aesthetic score are at this link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/13EXuptt6TpKqHWk6tDr2AWFLVSW-dHHC/view?usp=sharing (accessed on 24 September 2022).

The data and labels for style attribute classification are at this link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NQc-uCV42j71sumwh0jWeFpZyvMdHSW1/view?usp=sharing (accessed on 24 September 2022).

The following are the contributions and innovations of our work:

- We introduce a larger database of logos that are design materials. We evaluate the aesthetics of the data by manual annotation. The evaluation system includes six kinds of aesthetic scores, six kinds of style attribute labels and semantic descriptions. We also show five advantages of JN-Logo.

- We set up two tasks for JN-Logo: a style attribute classification task and an aesthetic quality scoring task. JN-Logo is tested using methods based on traditional features as well as deep features. Finally, the best performance is selected as the baseline.

- We demonstrate JN-Logo for logo retrieval and specifying color transfer. It is proven that high-quality data with aesthetic quality evaluation is more beneficial to intelligent system design.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present an aesthetic quality evaluation, aesthetic visual analysis database and logo database related to JN-Logo. In Section 3, we describe the aesthetic evaluation of JN-Logo and compare the pros and cons of related datasets. In Section 4, we present aesthetic visual analysis tasks and experiments. In Section 5, we describe two applications of JN-Logo: logo style generation and logo content similarity retrieval. In Section 5, we discuss how JN-Logo will be expanded for more research in the future.

2. Related Work

This section introduces the aesthetic visual analysis database and the logo database. At present, most of the data used for quality evaluation are photographic pictures. Subjective evaluation methods mainly involve scoring and annotation. Commonly used aesthetic analysis databases are: Databases of photographic aesthetics are AVA [2], CUHK [3], CUHKPQ [4,5] and Photo.Net dataset (PN) (https://www.photo.net, (accessed on 25 March 2021)) [6,7]. Image databases containing subjective evaluations of observers are also: Laboratory for Image & Video Engineering (LIVE) [8], Categorical Subjective Image Quality (CSIQ), IVC, MICT, A57, Tampere Image Database 2008 (TID2008) [9] and Tampere Image Database 2013 (TID2013) [10]. TID2013 is an enhanced version of TID2008. Additionally used are Wireless Imaging Quality (WIQ) [11], etc.

Logo databases are commonly used for logo retrieval [12], logo recognition [13,14,15,16] and logo detection [17,18,19]. The BelgaLogos database [20] was the first benchmark for logo detection and is used to detect logos. LogoDet-3K [21] is used for both logo detection and logo recognition and is the largest logo detection database with complete annotations. The logo-2K+ database [22] is only used for logo image recognition, similar to the logoDet-3K database. Some of the larger logo databases for object detection are FlickrLogos-32 [14] and Logos in the Wild [23]. The databases used for logo detection and logo recognition are Logo-Net [24], WebLogo-2M [25] and PL2K [26]. The large-scale databases used for logo detection are basically pictures of logo scenes, which are not suitable for the aesthetic analysis of logos. Small databases for logo recognition can be used for aesthetic analysis, but most are not publicly available and have small numbers. For example, Vehicle Logos is a dataset for classification and instance segmentation containing 34 logos, each with 16 images, for a total of 544 images. Each image has a corresponding image class label and instance segmentation image label. FlickrSportLogos-10 is a dataset of 10 sports brands with 2038 images that can be used for classification and object detection. HFUT-CarLogo dataset contains 32,000 car logo images, divided into HFUT-VL1 and HFUT-VL2, for classification and object detection, respectively. Car-Logos-Dataset contains 374 car logo images, one for each logo. The logos-627-Dataset is a dataset containing 627 logo images.

We have added new datasets in recent years to enrich our work, but they are not datasets of logo images.

The PIAA database [27] is an image aesthetics database containing 438 subjects with a total of 31,220 photographic images with rich aesthetic annotations from people and with rich subjective attributes. FLICKR-AES and REAL-CUR [28] are automatic aesthetic rating databases with people’s aesthetic preferences and content and aesthetic attributes suitable for residual-based models. AADB [29] is also a photographic image database for aesthetic scores and attributes, and the developers used a deep learning method—deep convolutional neural networks—to rank the aesthetics of photos. The current large multimodal database M5Product [30] has 6 million multimodal samples, including five modes: image, text, table, video and audio. Ego4D [31] is a large-scale video dataset with data captured using seven cameras. The DynamicEarthNet dataset [32] contains daily Planet Fusion images and Sentinel 2 images with manual annotation. It is a large-scale multi-class dataset with a multi-temporal change detection benchmark for the fields of Earth observation and computer vision. The FineDiving dataset [33] is a collection of videos of diving events and competitions, including the Olympic Games, World Cup, World Championships and other diving sports.

In the design domain, the applications of logo datasets are logo image generation, image retrieval and image recognition. Logo image datasets are mainly used in specific visual designs. There are few publicly available logo image datasets.

Therefore, a small logo dataset is mainly dominated by logo images. This the same type of data in the JN-Logo database introduced in this paper. However, JN-Logo has a larger scale and is collected, screened, filtered and manually annotated, and the quality of the image clarity and beauty is better.

3. Creating JN-Logo

We introduce the process of creating JN-Logo, a comparison of JN-Logo and related databases, and a visual analysis of JN-Logo.

3.1. Methodology

This section describes the steps to construct the dataset: acquisition, filtering and annotation.

3.1.1. Collecting

The images of JN-Logo were mainly obtained by crawling the Internet via https://www.logoids.com, https://www.logosj.com, https://www.logogala.com, https://image.baidu.com, https://www.logonews.cn/, https://logopond.com/gallery/list/?gallery=featured and http://www.zhengbang.com.cn/ (accessed on 25 March 2021).

LogoNews has more than 50 popular categories of content, including more than 90 different countries and regions and 49 design agencies. LogoPond can find the most popular logo designs on the Internet today. It mainly provides mock-up logo design videos and other services. Its biggest feature is to update the logo designs and other works uploaded by some artists or designers every month. The website “www.zhengbang.com.cn” (accessed on 25 March 2021) includes China’s top 500 companies, such as CCTV, Bank of China, China Southern Power Grid, and other companies, as well as Internet companies such as Baidu and Alibaba. It contains more than 50 industry categories, such as the Internet, new technology telecommunications, aviation, automobiles, home appliances, central enterprises, real estate, banking, medical and pharmaceuticals, road transportation, logistics, corporate services, consulting, etc. Thus, we can search for original domestic logos at this website. To increase the diversity of the dataset, we also grabbed logo images from categories such as “Internet company logo”, “cultural industry company logo”, “cosmetic brand logo” and “food brand logo” from online engines such as “Baidu.com”. We also supplemented information by photographing storefronts, company signs and logos. Through the above methods, we have collected a large number of pictures from different countries, industries, classifications and graphics, and with rich colors.

3.1.2. Interviews and Questionnaires

This section discusses annotations through interviews, questionnaires and data cleaning. To obtain the stylistic attributes of the logo images, this paper conducted a questionnaire to observe the participants’ preferences for style. The questionnaire contained 50 random logo images and 2 questions, as shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

The two questions we invited subjects to answer on the questionnaire.

According to the correlation between color and psychological feeling, we set dozens of labels with regard to Question 1. The content of the labels combines people’s psychological attributes, emotional attributes and aesthetic preferences. Finally, we evaluated style preference. Question 2 aims to understand people’s aesthetic preferences.

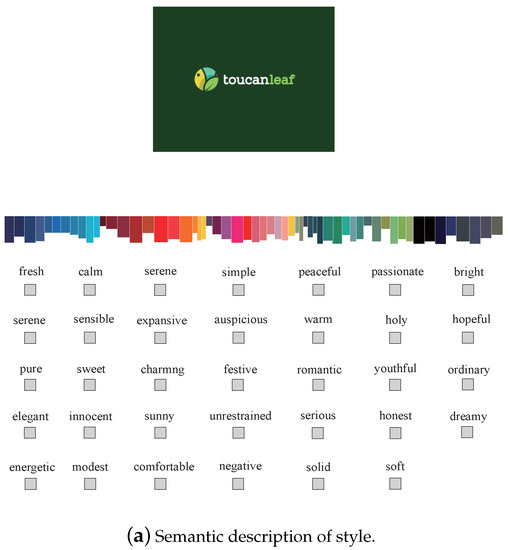

The content of the labeling is shown in Figure 1. It can be seen that the 10 most-appearing style descriptions were finally obtained through voting.

Figure 1.

Style labels in Question 1 and the style descriptions that received the most votes: (a) semantic description of the style of logo images and (b) the 10 selected semantic descriptions.

3.1.3. Cleaning

We obtained valid questionnaires from training subjects. This preliminary work was used for data cleaning. Then, to ensure data quality, the data were cleaned before labeling. We sanitized the data to ensure that the logo images were the appropriate size. In particular, we removed the following logo images: (a) images with length or height less than 300 pixels or extreme aspect ratios and (b) images with extreme aspect ratios.

3.1.4. Annotation

In JN-Logo, we provide three types of annotations: aesthetic, style and semantics. We chose 100 random images and asked subjects to annotate the images. In the annotation system, one image is randomly selected from the logo dataset at a time, each of which conforms to the original aspect ratio.

A total of 14,917 images were set and divided into image quality of 0–5 points and style attributes of 1–6. Approximately 150 people participated in marking during the scoring process. Finally, 6 quality scores, 6 style attributes and 11 style descriptions were obtained. With our scoring system, each subject annotated 100 images, and 150 people took turns annotating 14,917 images. The final scores for aesthetics, style and semantics were obtained.

3.2. JN-Logo Visual Analysis

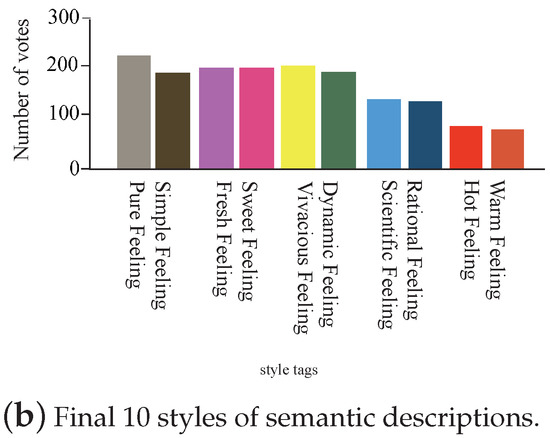

This section analyzes the score distribution and style classification distribution of the JN-Logo data. Score distribution and style classification distribution can solve two problems: (1) image quality score can learn the aesthetic preferences of landmark images, and (2) the distribution of style classification can learn style preferences and semantic descriptions. Figure 2 shows the amount of data for aesthetic ratings and the amount of data for style attributes.

Figure 2.

(a) The number data points for aesthetic preferences; (b) the number of data points for style attributes and style semantic descriptions.

It can be seen from Figure 2b that the number of data points for style attributes is mainly concentrated in Attribute 1 and Attribute 5. Further, it can be seen from the histogram that about 12 kinds of blue, such as dark blue and light blue, account for a large proportion in Attribute 1. From dark red, red, orange, and yellow, about 10 colors account for a large proportion in Attribute 2. From purplish red, rose red, light pink, light yellow, and mint green, about 13 colors account for the largest proportion in Attribute 3; it has the most mixed colors. In attribute 4, green has a large proportion, and about 13 green color systems have a large proportion. In attribute 5, the proportion of color distribution is relatively balanced, and about 9 different dark colors account for a large proportion. As shown in Figure 2a, the scoring data points are mainly concentrated between 3–5 points, with 4 points being the most popular. The category with picture quality of 1 point has the smallest number of pictures, about 800. From the perspective of database construction, this trend conforms to a uniform distribution. Quality score data and style attribute data are generally in line with the actual situation, and there is no extreme class imbalance problem, which means the dataset can meet the training requirements and can be used for classification and training algorithms.

As shown in Figure 2, the scoring data points are mainly concentrated between 3–5 points, and the logo data with 4 points is the most popular.

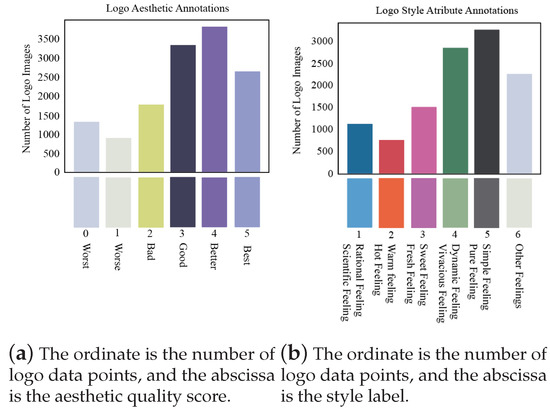

Figure 3 shows the color distribution of 6 style attributes and 11 style descriptions.

Figure 3.

Color distribution map of 6 style attributes of JN-Logo based on feeling: (a) Rational and Scientific, (b) Warm and Hot, (c) Sweet and Fresh, (d) Vivacious and Dynamic, (e) Simple and Pure, and (f) other.

A circle chart is a visualization of color data, and a histogram is a visualization of color value and specific gravity distribution extracted from the circle chart. Figure 4 shows a visualization of 57 colors. We extracted a total of 57 dominant colors from the data.

Figure 4.

Shows 57 colors extracted from 6 types of style attributes.

We performed statistical analysis of the colors in the six data styles of the style annotation. This can be seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

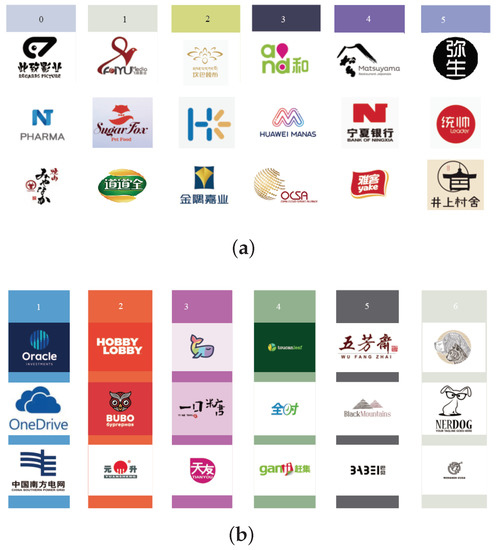

Finally, Figure 5 shows the image quality score image category (Figure 5a), and the style attribute image category (Figure 5b) with style semantic description.

Figure 5.

(a) Image quality score images (0–5). (b) Style attribute images with style semantic description (1–6).

A score of 0–5 is shown in Figure 5a, representing worst, worse, bad, good, better and best, respectively, with 5 points being the highest score. Figure 5b shows feelings of Rational, Scientific, Warm, Hot, Sweet, Fresh, Dynamic, Vivacious, Simple, Pure and Others. Thus, there are a total of 6 styles and 11 semantically described logo images. Due to the different subjective feelings of participants, their understanding of beauty was different. Subjects were judged on the basis that images with low clarity were rated lower. Further, the participants had different preferences for colors, graphics and content of images. It can be seen that although subjects had different aesthetic preferences, subjects still rated images with low clarity as lower.

Ultimately, the accuracy of the image quality score is unstable and is close to random guessing. On the other hand, the subjects of the style category images are more uniform in matching style selection and semantic description, so the distribution of style attributes is relatively accurate. The specific prediction method is introduced in Section 4.

3.3. Comparison of JN-Logo-Related Datasets

Table 2.

Comparison of the advantages of JN-Logo and four other quality-evaluation databases based on five aspects.

Table 3.

Comparison of the advantages of JN-Logo and four other logo databases based on five aspects.

This section compares the JN-Logo database to similar quality-evaluation databases and logo databases in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Five advantages of the JN-Logo database are having logo images as data objects, rich annotations, quality scores for image aesthetics, style attribute labels and description of the style; these aspects demonstrate the advantages of this database. We discuss the similarities and differences between JN-Logo and related databases.

The AVA [2] database contains approximately 250,000 images. Each image was scored by 78 to 549 raters, with scores ranging from 1 to 10. The average score is used as the ground-truth label for each image. The author annotated 1 to 2 semantic labels for each image based on the information in the text of each image. There are a total of 66 textual tags in the entire database. The pictures in AVA are marked with photographic attributes, which involve photographic aesthetics and are described from the three directions of light, color and composition. There are a total of 14 photographic attributes. This database contains by far the largest amount of aesthetic-quality evaluation data. However, the semantic annotations are not strictly classified and mainly describe the content and style of the images.

Both JN-Logo and AVA obtain human aesthetic preference scores and style attributes through manual annotation. The difference is that JN-Logo scores range from 0–5 points and style attributes from 1–6 points. The number of scores is 0: 1303, 1: 896, 2: 1775, 3: 3320, 4: 3793 and 5: 2636. In the style attribute annotation, the number in each category is 2752, 1622, 1733, 2647, 3268 and 2895, respectively. The distribution is shown in Figure 2.

The second difference is that JN-Logo is different from photographic databases. Logo image datasets are more suitable for design and have more research value and innovation. The third difference is that JN-Logo is based on the characteristics of logo design by adding image descriptions of visual psychological feelings to the style attributes, such as sense of reason and technology, enthusiasm and warmth, sweetness and vitality. The AVA dataset does not use this approach.

Photo.Net dataset (PN) (https://www.photo.net) [7] is a sharing platform for photography enthusiasts. Each picture has a rating of 1–7, and 7 is the most beautiful photograph. One advantage of PN scoring is that the scores are provided by online photography peers, and each image receives two or more points [2]. The difference between http://Photo.net and JN-Logo is that the former does not provide rich annotations, nor does it have style tags or semantic descriptions of styles.

CUHK [3] (http://DPChallenge.com) contains approximately 12,000 photographic images. Each photo has been scored by at least 100 users. CUHK has the same user score as AVAs with an advantage: the scoring method is different. All photos have only binary labels. The top and bottom 10% of photos are extracted and designated as high-quality professional photos and low-quality snapshots, respectively, but 80% of photos are ignored. CUHK has no style tags or semantic descriptions of styles. CUHK-PQ [4,5] (http://DPChallenge.com (accessed on 25 March 2021)) contains 17,690 images. All photos still only have binary labels (1 = high-quality images, 0 = low-quality images). However, photos have more content-based tags. The data are grouped into seven scene categories: animal, plant, still life, architecture, landscape, people and night scenery.

The difference between CUHK-PQ and JN-Logo is that the former has content-based classification labels. However, it does not have style tags. The most significant difference between JN-Logo and the above four databases is that JN-Logo’s content is not photographs but rather logo images, and JN-Logo adds a semantic description of the style.

There are four logo datasets introduced as follows: BelgaLogos [20] is the first benchmark for logo detection and is used to detect logos. All images are manually annotated, and the dataset consists of 10,000 images with 37 logos and 2771 logo instances annotated with bounding boxes. It has no score distribution, style labels or semantic descriptions.

WebLogo-2M [25] uses the social media site Twitter as its data source, with 194 logo categories and 1,867,177 images. WebLogo-2M is the first large-scale fully automated dataset constructed by exploiting inherently noisy web data. However, there is no human annotation, and it is not a public dataset.

Logo-2K+ [22] is a dataset for logo image recognition only. It is similar to the LogoDet-3K dataset and can be used for image classification and object detection. Logo-2K+ contains 10 major categories, 2341 subcategories and 167,140 images, with at least 50 images for each logo category. Logo-2K+ is a large logo dataset containing human annotations but does not have score distributions, style labels or semantic descriptions.

LogoDet-3K [21] is used for copyright infringement detection, brand awareness monitoring, etc. It is the largest logo detection dataset with complete annotations. It has 3000 logo categories, approximately 200,000 manually annotated logo objects and 158,652 logo images. The photos are human-annotated in detail, and each logo object is annotated and contains multiple instances of the logo. To ensure the annotation quality of LogoDet-3K, each bounding box is manually annotated and placed as close as possible to the logo object. LogoDet-3K contains not only logos and photos of logos but also a large logo dataset with human annotations. However, it has no score distribution, style labels or semantic descriptions.

The four aesthetic databases are based on photographs and refer to photographic aesthetics, and are mainly used for the aesthetic evaluation and classification of photographs. However, these data are not design-related images and are not fully applicable to the design field. The four logo datasets, such as BelgaLogos [20], have logo objects and photos containing logos, which are mainly used for retrieval, object detection, classification and image recognition. However, they do not have the aesthetic characteristics of images such as image quality scores and image style attributes. JN-Logo can be used for image quality assessment as well as logo image recognition and retrieval. In contrast, our JN-Logo database consists of logo images that can be used for logo-related aesthetic evaluation, retrieval, classification and generation.

The introduction of the eight databases above shows that the photographic image dataset for quality scoring and the logo image database for identification meet technical needs to a certain extent. However, different types of data (images) make it difficult to meet the needs of all disciplines. Because the content of the images is different, it is difficult to meet the needs of all disciplines, nor can it meet the needs of researchers in design disciplines for databases. The better the quality of the image and the closer the data type is to the needs of the algorithm, the more advantageous. Therefore, the JN-Logo database can meet the needs of designers and intelligent technology of logo images.

Figure 6 shows part of the logo data in the JN-Logo dataset.

Figure 6.

(a) Logo images with backgrounds. (b) Logo images without backgrounds.

4. Creation of Baseline

This section creates a baseline for JN-Logo as a performance criterion. We use methods based on traditional features and deep features to conduct experiments on JN-Logo, analyze the indicators of the model, prove the superiority of the performance of the model with higher accuracy, and use it as a baseline. We separately set the style classification task and the image quality scoring task to train simultaneously.

In the style classification task, the purpose is to train an attribute classifier that can separate logo images of different attributes. For an image , the attribute labels can be obtained through the style attribute classifier.

In the image aesthetic scoring task, it is also necessary to train a scoring classifier to distinguish different scoring levels. For an image , obtain the score of this image through the scoring classifier.

4.1. Method

The handcrafted and deep-feature methods used for the two tasks are described below.

(1) Methods based on handcrafted features:

The method based on handcrafted features is divided into two steps. First, the features of the image need to be extracted, and then, the features are input into the attribute classifier or the scoring classifier.

We used the following methods: the style attribute classifier corresponds to the style attribute classification task, and the scoring classifier corresponds to the quality scoring task. The Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) [34] is used to extract image features. The second step is to feed the features into a style attribute classifier and scoring classifier using a variety of approaches: (1) Support Vector Machine (SVM), (2) XGBoost [35] and (3) Random Forest [36].

Although the above traditional handcrafted features have the advantages of high efficiency and good interpretability, they cannot extract the implicit high-level semantic information of the picture, so they cannot achieve high accuracy. Therefore, we also consider using deep feature-based methods to accomplish these two tasks.

(2) Methods based on deep features: Deep feature-based methods use end-to-end training, feature extraction and downstream tasks performed on one model, and the image can be directly input into the deep model to obtain its attribute classification label or rating label.

The following models are used: Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [37,38,39], Residual Network, [40], EfficientNet [41,42], Visual Transformer Model [42] and MLP-Mixer [43].

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are a class of feedforward neural networks that contain convolutional computations and have deep structures. Its artificial neurons can respond to a part of the surrounding units within the coverage area and have the characteristics of local perception, weight sharing, downsampling, etc., reducing the number of parameters, expanding the network receptive field, and meaning the network does not need complex preprocessing of images. The original image can be directly input, so this method has been widely used in various tasks in the field of computer vision.

Residual Network (ResNet) [40] is mainly composed of residual blocks. By adding residual connections to the residual blocks, the problem of network degradation is solved, and the problem of gradient disappearance caused by increasing depth is alleviated so that the network can be deeper.

EfficientNet [41,42] is a model obtained by compound model expansion combined with neural structure search technology. It mainly scales the model automatically in the three dimensions of depth, width and scale.

Visual Transformer Model [42] is a deep self-attention mechanism learning model. Visual Transformer is a class of models that blocks images and inputs them into the transformer, abandoning the traditional CNN architecture and having less inductive bias.

MLP-Mixer [43] (Mixer) is entirely based on Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs), without using convolutions or self-attention, just repeatedly applied to spatial locations or feature channels. Mixer relies only on basic matrix multiplication routines, data storage layout transformations and scalar non-linearization.

The method in this section inputs the training data, that is, the large-scale sign image I, into the depth model to obtain the depth feature F, where F is a one-dimensional vector used for semantic representation of the sign image. After obtaining the image features, we complete the attribute classification and aesthetic scoring tasks through the style attribute classification layer or the scoring classification layer, respectively. The formula is as follows:

Specifically, the feature vector is mapped to the category label through a fully connected layer (FC), and the input probability value (logits) is obtained through the softmax function, which is expressed as follows:

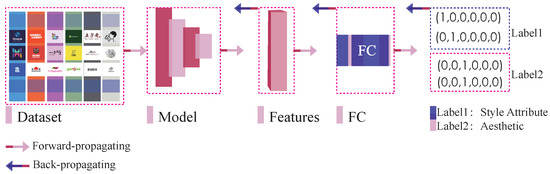

finally, the value of the cross-entropy function is calculated through the output logits, the value of the cross-entropy is minimized, and the network parameters are updated through the iterative training and back-propagation algorithm. Figure 7 shows the general framework of the deep model approach. The model completes two tasks based on different labels: style attribute classification and image quality scoring. In simple terms, we input the training image into the deep model to obtain deep features, complete the classification task through the classification layer, and iteratively update the model parameters through the back-propagation algorithm.

Figure 7.

Diagram of the deep model-based approach. This model completes two tasks of style attribute classification and aesthetic scoring based on different labels. First, input the training image into the deep model to obtain deep features, complete the classification task through the classification layer, and iteratively update the model parameters through the back-propagation algorithm.

Figure 7 shows the general framework of the deep model approach.

The deep-feature-based method is an end-to-end model that does not require a human to manually design algorithms to extract image features. The hidden high-level semantic features of images can be directly extracted through a large number of learnable parameters. Hence, manual intervention is reduced, and better performance is achieved.

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Dataset

For the dataset, JN-Logo is used to visually analyze all the data in the database, with a total of 14,917 images, which are divided by image quality (0–5 points), style attributes (1–6) and 10 (excluding “other”) style descriptions. The image quality score is 0–5, and the number of aesthetic scores 0–5 is shown in Table 4:

Table 4.

Number of aesthetic annotations of logo images.

The six categories of style attributes are called (1) Rational and Scientific, (2) Hot and Warm, (3) Sweet and Fresh, (4) Dynamic and Vivacious, (5) Pure and Simple and (6) other styles. The number of style attributes is shown in Table 5:

Table 5.

Number of style annotations of images.

The JN-Logo database is divided into a training set and a test set, and then 90% of the pictures are randomly set as the training set, and the remaining 10% of the pictures are set as the test set; the style attribute classification task and the image quality scoring task are set for simultaneous training (Equation (5)).

For the style attribute classification task, the purpose is to train an attribute classifier that can separate logo images of different attributes. For an image, its attribute label can be obtained through this attribute classifier, which can be expressed as:

4.2.2. Experimental Setup

We use the JN-Logo dataset (14,917) for training with the following hyperparameter settings: initial learning rate is set to ; there are a total of 20 rounds for training, and in the 10th and 15th rounds, the decay learning rate is 1/10 of the previous one; SGD is used as the optimizer, and the image resolution is set to .

4.2.3. Evaluation Metrics

For the tasks of logo attribute classification and aesthetic scoring, accuracy is used as the evaluation index:

where N and P are the predicted classes, (True Positive) is the number of positive samples predicted to be positive, (True Negative) is the number of negative samples predicted to be negative, (False Positive) is the number of negative samples predicted to be positive, and (False Negative) is the number of positive samples predicted to be negative.

4.2.4. Results and Analysis

The specific results are shown in Table 6. Accuracy 1 represents the accuracy of the manual feature method and the deep feature method for the style attribute category, and Accuracy 2 represents the accuracy of the manual feature method and the deep feature method for the aesthetic score category.

Table 6.

Accuracy 1 and Accuracy 2 of the manual feature method and the deep feature method.

In the logo attribute classification task, EfficientNet _B1 [45] achieved the best result, reaching an accuracy of 0.524. In the quality scoring task, neither hand-crafted feature-based methods nor deep feature-based methods achieved good results. The best performance by SeResNet50 [40,47] reached an accuracy of 0.293. Therefore, it can be seen that the participants differed greatly in scoring, and the different judgments of the quality of the logo images resulted in a low accuracy rate. For this situation, it is necessary to design a more appropriate model from the characteristics of the dataset itself. However, manual scoring has high randomness, and each person has different scoring standards, so predicting a high accuracy rate is still a challenging task.

In the quality scoring task, each person’s aesthetic preferences were different and failed to achieve good results. This is a challenge to be solved.

We compared performance parameters of precision, recall and F-1 measure. The performance parameters of the style attribute classification are shown in Table 7:

Table 7.

Comparison of performance parameters of precision, recall and F-1 measure of style classification.

The performance parameters table of aesthetic score is as follows (Table 8):

Table 8.

Comparison of performance parameters of precision, recall and F-1 measure of aesthetic classification.

The first three are traditional handcrafted features, the rest are deep learning features, and the table shows that deep feature-based methods have certain advantages. The results of aesthetics scoring are less than ideal, indicating that the aesthetics scoring task is still a challenging task.

We increased the real-time display FPS (frames per second), which represents the complexity of the algorithm. Complexity is inversely proportional to speed (Table 9).

Table 9.

FPS of models.

As shown in Table 9, the FPS frame rate of models such as Vit-B can meet the real-time requirements.

5. Application of JN-Logo

In this section, we introduce the purpose of the three JN-Logos. Then, we describe JN-Logo’s style classification and content classification for free-style-generated images, specified style-generated images and similarity-based retrieval. These can take advantage of JN-Logo by using the advantages of the image quality and color of the logo, as well as the style classification and content.

5.1. Similarity-Based Retrieval Based on Content Classification

At present, for the problem of logo infringement, the technology that can retrieve imitated logo designs is not perfect, and a high-quality dataset can better support the algorithm.

5.1.1. Methodology

This section provides JN-Logo as a logo image database that covers various industries and types and can be used to explore the similarity of logos. Specifically, in this section, we recall similar pictures through image retrieval-related technologies.

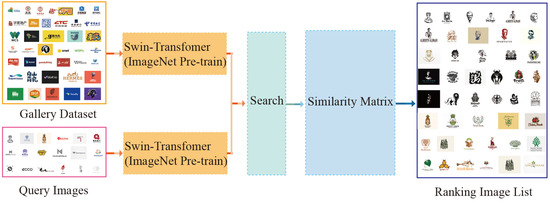

We conducted experiments by extracting features from the images in the JN-Logo dataset and preprocessing the logo images. Then, we input the data into a Swin Transfomer model [41] that was pretrained based on the ImageNet dataset [49], converted all logo images into one-dimensional vectors, and stored them. Then, for a picture to be retrieved, we used the previously acquired features to calculate its cosine similarity with the rest of the pictures. At the same time, the pictures were sorted by similarity, and the most-similar N pictures were returned. With this, it can found from the N pictures whether there are similar signs. We observed infringement, which reduced the cost of manual screening. Figure 8 shows the process of the experiment.

Figure 8.

Retrieval flowchart: for an image, extract features through the Swin Transformer model. Based on the extracted features, further calculate the cosine similarity of the pictures in the gallery set. Sort pictures by similarity, and return N pictures with the highest similarity.

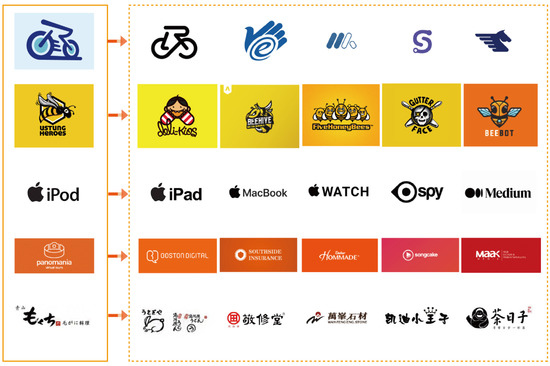

5.1.2. Results and Discussion

In this experiment, images with similar content are automatically screened out through an image retrieval model. Experiments showed that this method has a good effect on the similarity retrieval of JN-Logo data images. In addition, this method combined with our data can effectively deal with logo infringement and counterfeiting. Figure 9 shows some images whose similarity is close to the original image.

Figure 9.

Retrieve images close to the original image. They are the five original images extracted from the query dataset and the images retrieved from the corresponding gallery dataset.

We selected five groups of images with better results. As seen in Figure 9, the first three groups can detect pictures with obviously similar features. We found that similar parts of the illustration-style graphics are easier to retrieve. The third group of geometrically abstract figure-similar images can obviously be retrieved. A fourth group of similar images with a white pattern and an orange-red background is easier to retrieve. The fifth group of pictures is logo images of font designs in the form of oriental ink and wash, and it is difficult to find logos with high similarity.

When this happens, there may be three problems. First, the dataset is not large enough and needs to be expanded. Second, JN-Logo contains many pictures with the oriental style that were not detected, indicating that our algorithm needs to be further improved. Third, logos with oriental styles are more unique, and it is difficult to find similar images.

5.2. Image Generation Based on Style Attributes

When a user is dissatisfied with the color of a logo and wants to see a specific color, our database can provide a specific style of logo. Therefore, the problem of specifying colors to generate images can be solved.

5.2.1. Methodology

First, define the hue range for each style based on the hue circle. The enhanced operation principle and actual use are as follows:

1. Extract the background color:

In logo images, the background color is usually white, black or other colors, as shown in Figure 10. For the algorithm to work properly, the background part needs to be determined so that it can be replaced when the background needs to be preserved, or the background color can be changed separately.

Figure 10.

Images with different background colors, such as white, black, dark blue, dark red, bright yellow, dark purple, medium green, rose red, etc.

Specify a logo image img1 and determine the RGB value of the first pixel of the image as the background color b. The background color and its float (+−5) values are counted as background colors. Mark the area where the background color is located as the background for replacement after the style change is completed. When the color of the main body of the logo includes the background color, the background extraction algorithm regards the background color part of the main body (foreground) as the background. In this case, subsequent style changes ignore this part.

2. HSV color space conversion:

The RGB model does not conform to the visual perception of the human eye [50], while the HSV color space is closer to people’s visual perception of color than RGB. The HSV space expresses the hue, saturation and lightness and darkness of colors very intuitively. This is convenient for color comparison. When used to specify color segmentation, the HSV space has a relatively large effect.

3. Make a style change:

We list the style types and hue ranges in Table 10 below. There are many mixed colors in the vitality attribute. These colors are processed into two intervals representing two different specified colors.

Table 10.

We define four style types with image descriptions.

After specifying the type of color style to generate, a more appropriate and unique generated image is obtained to make the generated image contrast and generate more options. We first add the hue value of the image H as a random number r within (0, 10,000). Numeric-type conversion is also performed to prevent exceeding the representation range of unit8. Then, the color width (hue range) of the specified style is used to take the remainder of the transformed hue channel to determine the hue part of the specified style. Finally, the base value (the lowest value) of the style is added to make the colors all fall within the hue range of the color and obtain the generated hue value .

The formula is expressed as follows:

where is the hue value of position i, j of the original image, is the new hue value, is the current style hue peak value, and is the current style hue base value.

4. Convert HSV color space to RGB:

For computer storage and display, the HSV color space needs to be converted to the RGB color space.

5. Replace the background color:

In the style change step, we ignored the existence of the background. Therefore, the image background usually has a color after the change. To make the background blank, we replace the previously extracted background with the image after style generation. The entire algorithm (Algorithm 1) flow is shown in the following pseudocode:

| Algorithm 1 Specified Style’s image generation algorithm |

| Input: Original image img1. Output: Specified style image img2.

|

5.2.2. Results and Discussion

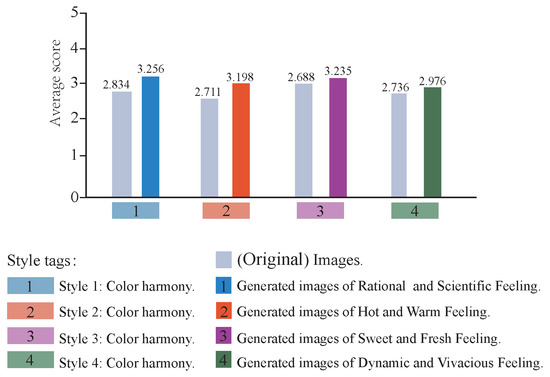

The color images generated by the specified image often have a single color, so we use the subjective evaluation method HVPA [51] to obtain the average value of color harmony for the four style attributes.

As above, using a five-point scoring system, the higher the score, the better the quality of the indicator. We select 50 generated images that perform very well and score them together with the original images. We still invite professional students to score and use the scores of 20 professional subjects to obtain 1000 scores and average them.

Scoring rules are shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Scoring system for indicator color harmony.

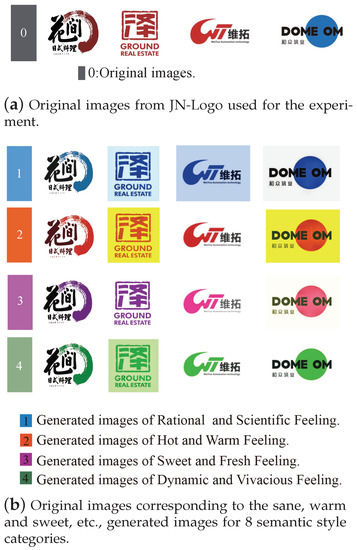

Figure 11 shows the original image and generated images for the four style categories.

Figure 11.

(a) Images from JN-Logo. (b) Four different styles of images from our method with 8 semantic descriptions.

We use Figure 12 to show the numerical comparison of subjective evaluation. The results show that the value range is concentrated between 2 and 3. It can be seen that the color harmony index of the generated images corresponding to the four style attributes is better than that of the original images.

Figure 12.

Comparison of color harmony score indicators for four subjectively evaluated original images and generated images.

6. Conclusions

We created a logo aesthetic image database that combines aesthetic analysis databases (Photographic Aesthetic Image) and logo image retrieval databases (Logo Retrieval Image), and we also established a baseline using a deep learning model. The model provides three types of annotations: aesthetic quality score, style attribute classification and semantic description. The data contain six aesthetic scores, six style labels and semantic descriptions. We compare JN-Logo with other related databases and show the advantages of JN-Logo in five aspects. Experiments on JN-Logo using traditional handcrafted features and deep feature methods establish a baseline for JN-Logo as a performance standard. We measure the effectiveness of the performance of algorithmic models that people choose to label data. We introduce JN-Logo for similarity retrieval of image content and image generation with style semantics. We demonstrate by the method that a high-quality database with specified content is more conducive to intelligent design.

In the style attribute classification task, the EfficientNet _B1 model achieved the best results, only reaching an accuracy of 0.524. Especially in the aesthetic scoring task, the best result comes from the SeResNet50 model, which only achieves an accuracy of 0.293, indicating that the current task is still challenging. Because manual annotation is hard to control, we will continue to optimize our database and improve the model in the future.

For example, we will invite art-related experts to score, improve the quality and accuracy of scoring and establish a better standard. We will design a multi-label system and perform multiple rounds of labeling. In the classification of style attributes, not only should the style of color be divided, but also the style of graphics should be classified. In the evaluation method, there is no objective evaluation index for the image quality of design material data such as logos. The database of this paper was used to propose a new evaluation index algorithm. In the design field, we can build a font-based logo image dataset, such as one that includes font logos of Chinese artists.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to this work. Conceptualization, N.T.; methodology, N.T.; software, N.T. and Z.S.; validation, N.T. and Z.S.; formal analysis, N.T. and Z.S.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, N.T.; writing—original draft, N.T.; writing—review and editing, Z.S.; visualization, N.T.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions e.g., privacy.The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the research results having potential commercial value.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the students from the School of Artificial Intelligence and School of Design at Jiangnan University for their help with scoring.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wu, F.; Lu, C.; Zhu, M.; Chen, H.; Pan, Y. Towards a new generation of artificial intelligence in China. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perronnin, F. AVA: A large-scale database for aesthetic visual analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision & Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, K.; Tang, X.; Feng, J. The Design of High-Level Features for Photo Quality Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’06), New York, NY, USA, 17–22 June 2006; pp. 419–426. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; Wang, X.; Tang, X. Content-Based Photo Quality Assessment. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2011, Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Luo, W.; Wang, X. Content-Based Photo Quality Assessment. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2013, 15, 1930–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, R.; Joshi, D.; Li, J.; Wang, J.Z. Studying Aesthetics in Photographic Images Using a Computational Approach. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2006, 9th European Conference on Computer Vision, Graz, Austria, 7–13 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, D.; Datta, R.; Fedorovskaya, E.; Luong, Q.T.; Wang, J.Z.; Jia, L.; Luo, J. Aesthetics and Emotions in Images. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2011, 28, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadiyaram, D.; Pan, J.; Bovik, A.C. A Subjective and Objective Study of Stalling Events in Mobile Streaming Videos. IEEE Trans. Image Proc. 2017, 29, 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarenko, N.; Carli, M.; Lukin, V.; Egiazarian, K.; Battisti, F. Metrics Performance Comparison For Color Image Database. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Workshop on Video Processing and Quality Metrics, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 14–16 January 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarenko, N.; Jin, L.; Ieremeiev, O.; Lukin, V.; Egiazarian, K.; Astola, J.; Vozel, B.; Chehdi, K.; Carli, M.; Battisti, F.; et al. Image database TID2013: Peculiarities, results and perspectives-ScienceDirect. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2015, 30, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepernick, H. Wireless Imaging Quality (WIQ) Database; Blekinge Tekniska Hgskola: Karlskrona, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, G.; Meng, K.; Li, H. Graph Based Visualization of Large Scale Microblog Data. In Proceedings of the Advances in Multimedia Information Processing– PCM 2015.Conference On, Part II, Gwangju, Korea, 16–18 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Revaud, J.; Douze, M.; Schmid, C. Correlation-Based Burstiness for Logo Retrieval. In Proceedings of the ACM Multimedia Conference, Nara, Japan, 29 October–2 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Romberg, S.; Pueyo, L.G.; Lienhart, R.; Zwol, R.V. Scalable logo recognition in real-world images. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval, Trento, Italy, 18–20 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantidis, Y.; Pueyo, L.G.; Trevisiol, M.; Zwol, R.V.; Avrithis, Y. Scalable triangulation-based logo recognition. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval, ICMR 2011, Trento, Italy, 18–20 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Romberg, S.; Lienhart, R. Bundle min-hashing for logo recognition. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM Conference on International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval, Dallas, TX, USA, 16–20 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.Q.; Wang, J.; Kankanhalli, M.S. Automatic video logo detection and removal. Multimed. Syst. 2005, 10, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Li, H.; Fan, X.; Liu, R.; Jia, Q. Region-based CNN for Logo Detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Internet Multimedia Computing and Service, Xi’an, China, 19–21 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Eggert, C.; Zecha, D.; Brehm, S.; Lienhart, R. Improving Small Object Proposals for Company Logo Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval, Bucharest, Romania, 6–9 June 2017; pp. 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, J.; Samet, H.; Soffer, A. Integration of local and global shape analysis for logo classification. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2001, 23, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Min, W.; Hou, S.; Ma, S.; Zheng, Y.; Jiang, S. LogoDet-3K: A Large-Scale Image Dataset for Logo Detection. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 12 August 2020; Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2008.05359.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Wang, J.; Min, W.; Hou, S.; Ma, S.; Jiang, S. Logo-2K+: A Large-Scale Logo Dataset for Scalable Logo Classification. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 6194–6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüzk, A.; Herrmann, C.; Manger, D.; Beyerer, J. Open Set Logo Detection and Retrieval. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications, Madrid, Portugal, 1 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hoi, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Xue, H.; Wu, Q. LOGO-Net: Large-scale Deep Logo Detection and Brand Recognition with Deep Region-based Convolutional Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 46, 2403–2412. [Google Scholar]

- Hang, S.; Gong, S.; Zhu, X. WebLogo-2M: Scalable Logo Detection by Deep Learning from the Web. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Fehervari, I.; Appalaraju, S. Scalable Logo Recognition Using Proxies. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 7–11 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, L.; Qie, N.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Guo, Y. Personalized Image Aesthetics Assessment with Rich Attributes. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 27 September 2022; pp. 19829–19837. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Shen, X.; Lin, Z.; Mech, R.; Foran, D.J. Personalized Image Aesthetics. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 638–647. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, K.; Shen, X.; Zhe, L.; Mech, R.; Fowlkes, C. Photo Aesthetics Ranking Network with Attributes and Content Adaptation. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Zhan, X.; Wu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Kampffmeyer, M.C.; Wei, X.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Liang, X. M5Product: Self-harmonized Contrastive Learning for E-commercial Multi-modal Pretraining. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 27 September 2022; pp. 21220–21230. [Google Scholar]

- Grauman, K.; Westbury, A.; Byrne, E.; Chavis, Z.; Furnari, A.; Girdhar, R.; Hamburger, J.; Jiang, H.; Liu, M.; Liu, X.; et al. Ego4D: Around the World in 3,000 Hours of Egocentric Vide. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 27 September 2022; pp. 18973–18990. [Google Scholar]

- Toker, A.; Kondmann, L.; Weber, M.; Eisenberger, M.; Camero, A.; Hu, J.; Hoderlein, A.P.; Enaras, A.; Davis, T.; Cremers, D. DynamicEarthNet: Daily Multi-Spectral Satellite Dataset for Semantic Change Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 27 September 2022; pp. 21126–21135. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Rao, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, G.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J. FineDiving: A Fine-grained Dataset for Procedure-aware Action Quality Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 27 September 2022; pp. 2939–2948. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE computer society conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR’05), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; Volume 1, pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Wei, L.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the Computer Science-Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 10 April 2015; Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1409.1556.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J. Object Detection Networks on Convolutional Feature Maps. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 39, 1476–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 1 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 22 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tolstikhin, I.; Houlsby, N.; Kolesnikov, A.; Beyer, L.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Yung, J.; Keysers, D.; Uszkoreit, J.; Lucic, M.; et al. Mlp-mixer: An all-mlp architecture for vision. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 24261–24272. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Laurens, V.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 2019, 97, 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, H.; Sun, Y.; He, T.; Mueller, J.; Manmatha, R. ResNeSt: Split-Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 2736–2746. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G.; Albanie, S. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Girshick, R.; Dollár, P.; Tu, Z.; He, K. Aggregated Residual Transformations for Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1492–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, D.; Wei, D.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Kai, L.; Li, F.F. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, M.J.; Ballard, D.H. Color indexing. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 1991, 7, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 740–755. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1405.0312.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).