Abstract

In the pursuit of real-time object detection with constrained computational resources, the optimization of neural network architectures is paramount. We introduce novel sparsity induction methods within the YOLOv4-Tiny framework to significantly improve computational efficiency while maintaining high accuracy in pedestrian detection. We present three sparsification approaches: Homogeneous, Progressive, and Layer-Adaptive, each methodically reducing the model’s complexity without compromising its detection capability. Additionally, we refine the model’s output with a memory-efficient sliding window approach and a Bounding Box Sorting Algorithm, ensuring precise Intersection over Union (IoU) calculations. Our results demonstrate a substantial reduction in computational load by zeroing out over 50% of the weights with only a minimal 6% loss in IoU and 0.6% loss in F1-Score.

1. Introduction

Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) have transformed object detection by enabling high-accuracy recognition in complex scenes. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) in particular preserve spatial hierarchies in images and remain the dominant backbone for vision tasks. YOLO (You Only Look Once) [1,2], a widely deployed single-stage detector, is known for its favorable trade-off between accuracy and latency, making it a common choice in real-time applications such as Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS).

Despite their efficiency, detectors like YOLO still pose challenges for deployment on embedded and low-power platforms. Model size and computational demand continue to grow with network depth, motivating the need for compression and sparsification. Classical pruning methods [3,4,5] often rely on retraining to recover accuracy, which is costly and impractical in resource-constrained or on-the-fly scenarios. This motivates retraining-free sparsification approaches that reduce redundant computation directly during inference.

Evaluation methodology also requires reconsideration. Traditional detection reporting often includes Precision, Recall, and F1 score. However, these classification-centric metrics fail to reflect localization quality, producing paradoxes such as high F1 with misaligned bounding boxes. Modern benchmarks such as COCO [6] standardize on Average Precision (AP) across IoU thresholds, and recent metrics like GIoU [7] and CIoU/DIoU [8] further refine localization assessment. In this work, we emphasize Intersection-over-Union (IoU) as our primary evaluation measure while still reporting F1 for comparability with prior YOLO literature. This dual perspective allows both backward compatibility with existing studies and forward alignment with modern AP-style evaluation.

Contributions. This paper proposes lightweight, retraining-free sparsification of YOLOv4-Tiny during inference, along with improvements to evaluation methodology:

- We critique the reliance on F1 score in detection tasks where localization dominates, and instead prioritize IoU while explicitly clarifying the role of F1 as a secondary, comparative metric.

- We introduce the Bounding Box Sorting Algorithm (BBSA) to better align predictions and ground truth for IoU computation. While heuristic, it exposes the shortcomings of naïve matching in sparsified settings.

- We propose several sparsification schemes that dynamically skip computation for low-impact weights at inference time. These methods eliminate more than 50% of multiplications in YOLOv4-Tiny without retraining, achieving only a 6% IoU drop and 0.6% F1 drop, highlighting their suitability for embedded deployment.

2. Motivation

Model compression for object detection must be evaluated not only by classification accuracy but also by localization quality. This section motivates our evaluation methodology by reviewing YOLO, discussing the shortcomings of conventional metrics, and highlighting the advantages of IoU-based assessment in sparsified detectors.

2.1. Background: What Is YOLO?

YOLO is a CNN designed for real-time object detection. It formulates detection as a single regression problem, directly predicting bounding box coordinates and class probabilities in one forward pass [1]. This avoids the multi-stage pipeline of traditional detectors and makes YOLO attractive for latency-sensitive deployment.

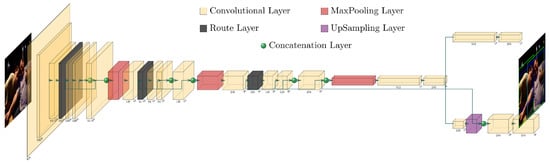

The input image propagates through 37 layers including convolution, max-pooling, up-sampling, and route layers, as shown in Figure 1. Max-pooling reduces spatial resolution by selecting maxima, while up-sampling interpolates to increase resolution. Route layers concatenate activations across channels. The image is divided into a grid, with each cell predicting bounding boxes and probabilities for objects within. Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) then filters redundant boxes. Unless otherwise stated, we rely on the default greedy NMS implementation of YOLOv4-Tiny. This clarification is essential, since variants such as Soft-NMS [9], DIoU-NMS, or CIoU [8] produce different IoU distributions.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the YOLOv4-Tiny architecture. Layer sizes and aspect ratios are drawn to approximate actual proportions.

2.2. Assessing Inference Accuracy in YOLO

Object detection quality depends both on identifying the correct class and on localizing objects precisely. Metrics such as Precision, Recall, and F1-score are widely used, but they reflect classification success rather than bounding box alignment. Their definitions are:

Here TP denotes true positives, FP false positives, and FN false negatives. However, in many detection scenarios, a TP is defined only if the predicted box overlaps the ground truth with IoU [6]. Without such a threshold, Precision and Recall may saturate at 100% even for severely misaligned boxes.

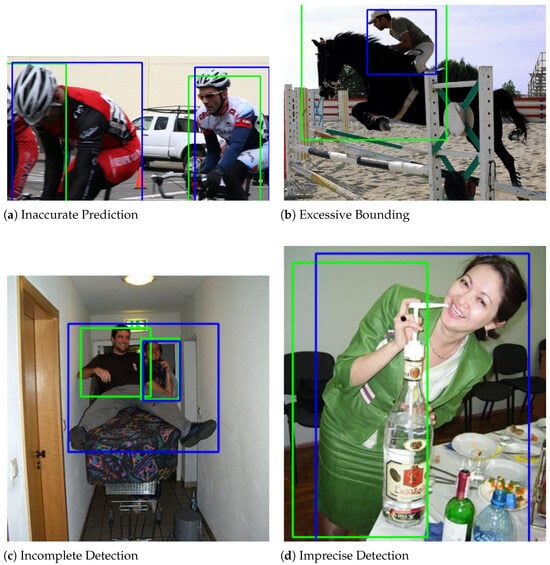

- Limitations of F1 for ADAS: In safety-critical applications such as ADAS, bounding box placement is as important as correct classification. Figure 2 and Table 1 illustrate paradoxical cases where Precision, Recall, and F1 are all 100% but bounding boxes are clearly misaligned, leading to low IoU. This exposes the risk of relying on F1 alone.

Figure 2. Blue = ground truth, Green = YOLO prediction. Even with Precision/Recall/F1 = 100%, IoU exposes misalignment.

Figure 2. Blue = ground truth, Green = YOLO prediction. Even with Precision/Recall/F1 = 100%, IoU exposes misalignment. Table 1. Comparative metrics for sample images in Figure 2 using YOLOv4-Tiny. IoU highlights mislocalization despite perfect classification scores.

Table 1. Comparative metrics for sample images in Figure 2 using YOLOv4-Tiny. IoU highlights mislocalization despite perfect classification scores.

To focus on the most safety-relevant class, we filter YOLO outputs at the post-processing stage to retain only pedestrian detections. The network is not modified; instead, all non-pedestrian predictions are discarded during evaluation. This ensures consistent measurement of pedestrian localization accuracy. Example images are selected randomly from the pedestrian dataset to illustrate representative success and failure modes.

2.3. IoU and Modern Extensions

IoU directly measures bounding box overlap:

It is now the basis of modern benchmarks such as COCO AP@[0.50:0.95] [6]. Extensions such as GIoU [7] and DIoU/CIoU [8] refine the metric to better penalize misalignment. We adopt IoU as our primary measure, but continue reporting F1 for backward comparability.

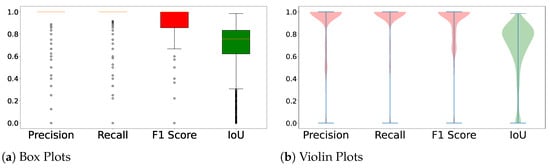

2.4. Significance

Figure 2 and Figure 3 demonstrate that IoU captures localization degradation overlooked by F1. This distinction is crucial when analyzing sparsification effects, where small weight perturbations can shift bounding boxes. Robust evaluation also depends on principled matching between predictions and ground truth. In Section 3, we introduce both heuristic (BBSA) and principled (Hungarian/Munkres [10,11]) matching strategies to expose how evaluation methodology influences perceived sparsification impact. This motivates our focus on IoU as the central metric for assessing compressed YOLO models.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Precision, Recall, F1, and IoU over 944 pedestrian images [12]. IoU reveals greater spread, reflecting variability in localization accuracy.

3. Understanding YOLOv4-Tiny Characteristics for Sparsification

This section characterizes YOLOv4-Tiny to establish a foundation for sparsification. We begin with a weight distribution analysis that highlights the relative importance of outlier versus median weights and motivates threshold-based pruning. We then introduce a generic sparsity framework that formalizes pruning thresholds. Next, we describe the Bounding Box Sorting Algorithm (BBSA) as a lightweight heuristic for matching predicted and ground-truth boxes under sparsified inference. Finally, we explore linear sparsity as an illustrative experiment, showing how gradually increasing sparsity affects performance metrics. This scaffolding prepares the ground for the specific sparsification strategies in Section 4.

3.1. Weights Distribution Analysis

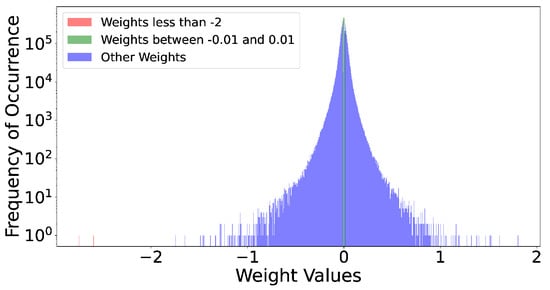

In CNNs, the multiplication and accumulation of weights and activations dominate computation, with each weight’s influence proportional to its magnitude. In YOLOv4-Tiny, we apply sparsification strategies that zero out less significant weights. This does not alter the network structure but induces sparsity, optimizing efficiency while preserving architecture. Importantly, sparsity also creates opportunities for future hardware to skip multiplications with zero weights, improving inference efficiency.

Figure 4 plots YOLOv4-Tiny’s weights on a logarithmic scale. Most weights cluster near median magnitudes (green), while a few outliers dominate (red). Removing just the two largest outliers reduces F1 by 1.24%, while removing nearly two million median weights causes only a 0.51% drop. This suggests disproportionate influence of a small set of weights. While these numbers are illustrative and not statistically tested, they motivate careful treatment of outliers in sparsification.

Figure 4.

YOLOv4-Tiny weight distribution on log scale. Outliers (red) disproportionately affect accuracy, while median weights (green) have smaller impact.

To further guide thresholding, we also analyze interquartile ranges (IQR) of weights across layers. The IQR principle, detailed in Section 4, adapts pruning thresholds to dataset-dependent distributions, enabling retraining-free sparsification tuned to weight statistics.

3.2. Generic Sparsity Framework

Let YOLOv4-Tiny contain L convolutional layers, indexed , with weights . Each , where F is number of filters, C input channels, and spatial dimensions. Our goal is to prune low-magnitude weights without retraining.

We define per-layer pruning thresholds using two strategies:

where controls the fraction of weights retained, and specifies the target sparsity for layer l. and map these parameters to thresholds . Sensitivity analysis for f and is reported in Section 6. Pruning is applied as:

This operation induces structured zeros that simplify hardware computation by skipping multiplications with zero weights.

3.3. Improving IoU Estimation: Bounding Box Sorting Algorithm

Accurate IoU evaluation requires matching predicted boxes with ground truth . Standard greedy matching may fail under sparsification, where over- and under-predictions are common. We propose a heuristic Bounding Box Sorting Algorithm (BBSA), described in Algorithm 1, to align predictions with ground truth.

| Algorithm 1 Bounding Box Sorting Algorithm |

|

BBSA handles under-prediction by duplicating best matches, and over-prediction by discarding surplus boxes. This ensures each ground-truth object has a matched prediction. However, duplication and discarding can distort IoU, Precision, and Recall. We acknowledge this limitation and analyze its effect in Section 6. To provide context, we later contrast BBSA with principled bipartite matching via the Hungarian/Kuhn–Munkres method [10,11].

3.4. Effects of Linear Sparsity on Model Performance

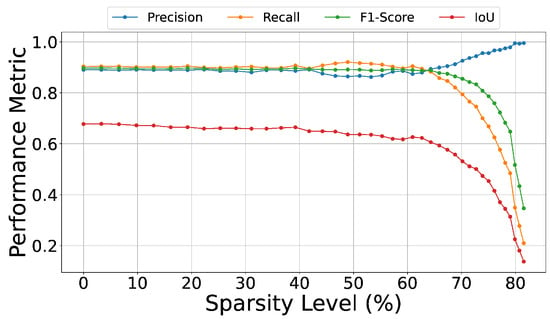

As a baseline, we experiment with linearly pruning middle-range weights. Guided by the weight distribution, we increment sparsity until collapse, observing its effect on metrics. Figure 5 shows Precision, Recall, F1, and IoU under varying sparsity.

Figure 5.

Performance metrics under increasing sparsity. IoU degrades earlier than F1, validating IoU as a more sensitive localization measure.

Results show Precision, Recall, and F1 remain stable until ∼42% sparsity, collapsing near 64%. IoU, however, begins degrading earlier, revealing localization sensitivity to pruning. This supports IoU as the primary evaluation metric and motivates more principled sparsification functions and developed in Section 4.

4. Sparsification Strategies for YOLOv4-Tiny

Building on the groundwork of Section 3, we now present specific sparsification strategies for YOLOv4-Tiny. We group them into three categories: (i) homogeneous methods that apply global sparsification, (ii) progressive methods that introduce layer-wise gradients, and (iii) layer-adaptive methods that incorporate weight distribution statistics such as the interquartile range (IQR). Throughout, we emphasize that while F1 is reported for comparability with prior YOLO studies, IoU remains the central metric, in line with COCO-style evaluation [6] and modern localization metrics such as GIoU/CIoU [7,8].

4.1. Homogeneous Method

The Homogeneous Method enforces a consistent sparsity across all layers, ensuring a balanced but coarse reduction in complexity. This can be achieved either by a global threshold or by a uniform sparsity level. Parameters are defined as: , the fraction of the minimum layer range used as threshold; and , the fraction of weights pruned globally. In practice, f values between 0.1–0.5 and values up to 0.7 provided stable results, as shown in Section 6.

4.1.1. Homogeneous Threshold Method

In the Homogeneous Threshold Method (HTM), a global threshold is derived from the smallest spanning layer, preventing over-pruning:

Here . Selecting removes the smallest layer entirely, which collapses connectivity.

4.1.2. Homogeneous Sparsity Method

Alternatively, the Homogeneous Sparsity Method (HSM) applies a uniform sparsity level across the network:

This enforces global pruning independent of per-layer distributions.

4.2. Progressive Method

The Progressive Method gradually increases sparsification from shallow to deep layers. Early layers (feature extractors) are pruned lightly, while deeper layers (refinements) are pruned more aggressively.

4.2.1. Progressive Threshold Method

Thresholds are ramped from to :

For layer l:

4.2.2. Progressive Sparsity Method

Sparsity levels are linearly increased:

This guarantees shallow layers always retain some weights, preventing collapse.

4.3. Layer-Adaptive Method

Layer-adaptive sparsification tailors thresholds per layer, guided by weight distributions. Two strategies are considered: the IQR-Based Threshold Method and the Layer-Specific Sparsity Method. These adapt thresholds to statistical variation rather than enforcing uniformity.

4.3.1. IQR-Based Threshold Method

The IQR-Based Threshold Method, shown in Algorithm 2, adaptively defines layer thresholds based on the statistical spread of weights, shown in Figure 6, making sparsification dataset- and layer-aware. For each layer l:

where and are quartiles of the weight distribution and is a user-controlled sparsity factor. Two adjustment terms moderate pruning intensity:

- : reduces pruning when the quartile range is wide, preserving diverse critical weights.

- : increases pruning when weights cluster tightly around the median, exploiting redundancy.

This balances aggressive pruning in dense, low-variance layers with conservative pruning in layers containing broad, high-variance weights (Table 2).

Figure 6.

Layer-wise weight distributions in YOLOv4-Tiny. Wider IQR ⇒ conservative pruning; denser medians ⇒ aggressive pruning.

| Algorithm 2 IQR-based Sparsification |

|

Table 2.

Layer-specific adjustments based on weight distribution. Larger IQR ⇒ conservative pruning; higher density ⇒ aggressive pruning.

Compared to homogeneous and progressive methods, the IQR approach dynamically adapts to each layer’s statistical profile. Layers with tight, redundant distributions tolerate aggressive pruning; layers with broad, high-variance weights retain capacity. This distribution-aware mechanism explains why the IQR method sustains accuracy at higher sparsity levels in Section 6, highlighting its advantage for real-time deployment.

4.3.2. Layer Specific Sparsity Method

Alternatively, each layer applies a uniform percentile-based sparsity:

This balances per-layer reductions while avoiding collapse.

- Discussion. The homogeneous and progressive methods provide global control, while the IQR-based and layer-specific methods adapt pruning to layer statistics. Parameters f and trade off between aggressiveness and accuracy; we report sensitivity analyses in Section 6. BBSA is used for lightweight box matching under sparsification, but we note it can bias IoU/Precision/Recall by duplicating or discarding boxes. Accordingly, we later contrast it with Hungarian/Munkres assignment [10,11]. Finally, all methods target weight sparsification only; activation quantization is left for future work.

5. Experimental Methodology

This section describes the end-to-end methodology used to evaluate sparsification in YOLOv4-Tiny. The workflow integrates dataset preprocessing, weight pruning, custom convolution blocks, and evaluation. Figure 7 provides a system-level overview.

Figure 7.

Workflow of the sparsification evaluation platform.

5.1. Workflow Overview

The pipeline begins with dataset preprocessing, where pedestrian annotations are parsed into structured tensors containing images and bounding-box coordinates. In parallel, network weights and layer configurations are extracted from the original YOLOv4-Tiny model. These weights are then passed to our sparsification module, which applies one of the strategies described in Section 4. A no-op path is included for dense baselines.

The sparsified weights () are re-integrated into a modified YOLOv4-Tiny model that uses custom convolution and batch-normalization blocks. This modification exposes fine-grained control over sparsity injection and ensures deterministic comparisons across strategies. Predictions are post-processed using our Bounding Box Sorting Algorithm (Section 3.3) to align predicted and ground-truth boxes. The resulting detections are then evaluated using IoU and F1, consistent with the motivation in Section 2.

5.2. Efficient Convolution Implementation

Convolution layers dominate the compute cost in YOLOv4-Tiny. To isolate the effect of sparsification without confounding framework-level optimizations, we implemented custom convolution blocks that expose direct control over weight access. These blocks leverage a memory-efficient sliding-window formulation, avoiding data duplication and approximating the throughput of PyTorch’s native kernels. The same blocks are used for both dense and sparse runs, ensuring fairness across baselines. This design allows us to quantify the impact of sparsification independently of library-specific optimizations while maintaining realistic computational cost.

6. Experimental Results

We evaluate the sparsification strategies of Section 4 on YOLOv4-Tiny, reporting detection accuracy using F1 and IoU. Unless otherwise noted, results are averaged over three random seeds; variation was consistently within F1 and IoU. We organize the results into intra-method comparisons, inter-method comparisons, and tabulated summaries.

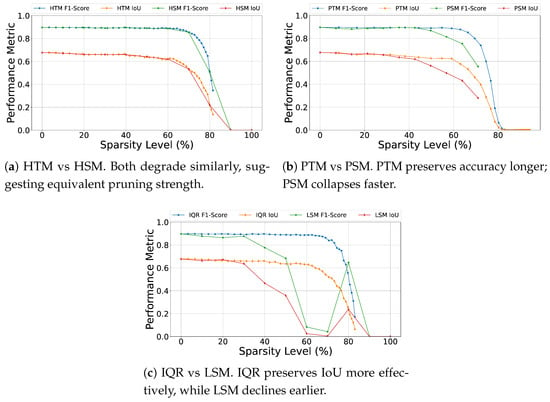

6.1. Intra-Method Comparison

Homogeneous: Figure 8a contrasts HTM and HSM. Both produce nearly identical degradation curves, indicating that global thresholds and global sparsity levels converge to comparable effective . The choice of formulation (threshold vs. level) thus has limited impact.

Figure 8.

Intra-method performance comparison under varying sparsity levels. (a) compares global thresholding (HTM) against global sparsity (HSM); (b) contrasts progressive thresholding (PTM) with progressive sparsity (PSM); (c) evaluates the distribution-aware IQR method against the naive layer-specificmethod (LSM).

Progressive: Figure 8b compares PTM and PSM. PTM prunes gradually and preserves accuracy longer, while PSM applies high sparsity to deeper layers early, removing critical weights and collapsing sooner. This shows thresholds provide finer control than directly enforcing layer sparsity.

Layer-Adaptive: Figure 8c compares the IQR-based method with LSM. IQR exploits per-layer weight distributions to protect important weights, maintaining F1 and IoU up to ∼70% sparsity. LSM, by applying uniform levels, degrades much earlier. Both collapse near 80% sparsity, but IQR achieves significantly higher IoU at intermediate levels.

6.2. Inter-Method Comparison

Figure 9a aggregates threshold-based methods. HTM and IQR remain stable up to ∼60% sparsity, with IoU degrading only gradually. PTM degrades faster, highlighting the cost of aggressive late-layer pruning.

Figure 9.

Inter-method aggregate analysis of sparsification strategies. (a) shows the superiority of distribution-aware (IQR) and global (HTM) thresholds over progressive ramping; (b) illustrates that global uniformity (HSM) and gradual progression (PSM) are significantly more robust than independent layer-specific sparsity (LSM).

Figure 9b compares sparsity-level methods. HSM is most stable, retaining ∼89% F1 and ∼66% IoU until 40% sparsity. PSM degrades sooner, while LSM collapses abruptly at higher sparsity. These results confirm that distribution-aware thresholds (IQR) or global uniformity (HSM) are safer than progressive or naive per-layer levels.

6.3. Tabulated Comparison of Pruning Strategies

Table 3 and Table 4 report detailed F1, IoU, and normalized IoU (NIoU) across sparsity levels. Three trends emerge:

- All methods are stable up to ∼40% sparsity; beyond this, IoU declines earlier than F1, reaffirming IoU as the more sensitive metric.

- IQR achieves the best trade-off, retaining 89.6% F1 and 66.1% IoU at 40% sparsity, compared to LSM’s collapse at the same level.

- Progressive strategies (PTM, PSM) are consistently less robust, indicating that monotonic layer-wise pruning is less effective than global or distribution-aware thresholds.

Table 3.

Performance of sparsity-level methods (HSM, PSM, LSM) across sparsity levels. IoU reveals earlier degradation than F1.

Table 3.

Performance of sparsity-level methods (HSM, PSM, LSM) across sparsity levels. IoU reveals earlier degradation than F1.

| HSM | PSM | LSM | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL | F1 | IoU | NIoU | SL | F1 | IoU | NIoU | SL | F1 | IoU | NIoU | ||

| 0 | 89.7 | 67.7 | 100 | 0 | 89.7 | 67.7 | 100 | 0 | 89.7 | 67.7 | 100 | ||

| 20 | 89.4 | 66.0 | 97.5 | 14.2 | 88.1 | 66.1 | 97.6 | 20 | 86.4 | 67.2 | 99.3 | ||

| 40 | 89.6 | 65.9 | 97.3 | 28.4 | 88.9 | 65.6 | 96.9 | 40 | 77.6 | 46.5 | 68.7 | ||

| 60 | 88.7 | 62.0 | 91.6 | 42.6 | 89.2 | 61.9 | 91.4 | 60 | 8.3 | 2.6 | 3.8 | ||

| 80 | 50.6 | 21.8 | 32.2 | 56.8 | 81.3 | 49.8 | 73.4 | 80 | 64.6 | 23.7 | 35.0 | ||

| 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 70.9 | 55.4 | 28.0 | 41.4 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Table 4.

Performance of threshold-based methods (HTM, PTM, IQR). IQR and HTM are most stable; PTM collapses early.

Table 4.

Performance of threshold-based methods (HTM, PTM, IQR). IQR and HTM are most stable; PTM collapses early.

| HTM | PTM | IQR | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL | F1 | IoU | NIoU | SL | F1 | IoU | NIoU | SL | F1 | IoU | NIoU | ||

| 0 | 89.7 | 67.7 | 100 | 0 | 89.7 | 67.7 | 100 | 0 | 89.7 | 67.7 | 100 | ||

| 19.2 | 89.7 | 66.5 | 98.2 | 24.3 | 89.4 | 66.2 | 97.8 | 19.4 | 89.7 | 66.4 | 98.1 | ||

| 39.2 | 89.6 | 66.4 | 98.1 | 38.2 | 89.5 | 64.5 | 95.3 | 39.6 | 89.6 | 66.1 | 97.6 | ||

| 60.9 | 88.9 | 62.6 | 92.5 | 59.1 | 88.8 | 62.4 | 92.2 | 60.8 | 88.7 | 62.8 | 92.8 | ||

| 80.7 | 43.3 | 18.0 | 26.6 | 80.2 | 6.46 | 2.31 | 3.4 | 80.6 | 45.4 | 19.3 | 28.5 | ||

7. Related Work

We review two main areas relevant to this work: (i) localization metrics for object detection and (ii) sparsification techniques, with emphasis on retraining-free approaches.

7.1. Localization Metrics

Precise evaluation of detection models requires metrics that capture both classification accuracy and spatial alignment. While Precision, Recall, and F1 summarize classification quality, they fail to distinguish well-localized from poorly aligned detections. The Intersection-over-Union (IoU) metric addresses this gap by measuring bounding box overlap, and has become the basis of modern benchmarks such as COCO AP@[0.50:0.95] [6]. Several extensions refine IoU: GIoU [7], DIoU/CIoU [8], probabilistic IoU [13], and scale/variance-aware variants [14,15]. These works optimize IoU during training to improve convergence. By contrast, our study uses IoU distributions at inference time to evaluate how sparsification perturbs localization quality, complementing F1 for comparability with prior YOLO literature.

7.2. Sparsification Techniques

Model sparsification is a longstanding strategy for reducing inference cost. Classical pruning pipelines [5,16,17] rely on iterative prune–retrain cycles to recover accuracy. Surveys such as Hoefler et al. [3] highlight the overhead of such retraining, which limits applicability in real-time or resource-constrained settings.

Retraining-free sparsification methods aim to bypass this overhead. Ashouri et al. [18] proposed flat, triangular, and relative pruning for CNN classifiers without retraining. More recently, hardware-oriented pruning schemes have been proposed for efficient deployment on embedded accelerators, though most remain tied to classification tasks. Our contribution adapts and extends retraining-free sparsification to object detection, where localization accuracy is paramount and inference latency is critical. We introduce Homogeneous and Progressive strategies, as well as a dataset-dependent IQR-based method that exploits layer-wise weight statistics to define pruning thresholds, bridging the gap between classification-centric pruning and detection-aware evaluation.

Unlike iterative retraining pipelines, our methods operate directly at inference by setting low-importance weights to zero, reducing multiplications without altering model structure. This enables fast deployment while preserving detection quality, as quantified by IoU under sparsification.

8. Conclusions

We evaluated retraining-free sparsification strategies for YOLOv4-Tiny with a focus on inference-time efficiency. Among the methods studied, the IQR-based thresholding approach proved most effective, leveraging layer-wise weight distributions to retain accuracy under high sparsity. In contrast, uniform and progressive methods degraded more rapidly, underscoring the importance of distribution-aware pruning. Evaluation further confirmed that IoU is a more sensitive indicator of localization quality than F1, especially as sparsity increases.

To ensure consistent measurement under pruning-induced mispredictions, we introduced the Bounding Box Sorting Algorithm (BBSA). While lightweight, it may bias metrics in cases of duplication or discarding, motivating future work on principled assignment (e.g., Hungarian matching). More broadly, this study demonstrates that meaningful sparsity gains can be achieved without retraining, enabling real-time deployment on constrained platforms.

Future directions include extending distribution-aware sparsification to multi-class COCO-scale datasets, integrating board-level latency and power measurements, and exploring activation pruning to complement weight sparsity. These steps will provide a more complete view of sparsification for detection models in practical embedded settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-u.-R.K.; Methodology, T.-u.-R.K.; Software, T.-u.-R.K.; Validation, T.-u.-R.K.; Formal analysis, K.C. and S.R.; Investigation, T.-u.-R.K.; Resources, T.-u.-R.K.; Writing—original draft, T.-u.-R.K.; Writing—review & editing, T.-u.-R.K., K.C. and S.R.; Supervision, K.C. and S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J. Understanding of object detection based on CNN family and YOLO. Proc. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1004, 012029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefler, T.; Alistarh, D.; Ben-Nun, T.; Dryden, N.; Peste, A. Sparsity in deep learning: Pruning and growth for efficient inference and training in neural networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 1–124. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W.J. Deep Compression: Compressing Deep Neural Networks with Pruning, Trained Quantization and Huffman Coding. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1510.00149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, W.; Xu, H.; Zhang, T. Effective sparsification of neural networks with global sparsity constraint. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 3599–3608. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Bourdev, L.; Girshick, R.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Zitnick, C.L.; Dollár, P. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1405.0312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezatofighi, H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized Intersection over Union: A Metric and A Loss for Bounding Box Regression. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.09630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU Loss: Faster and Better Learning for Bounding Box Regression. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.08287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodla, N.; Singh, B.; Chellappa, R.; Davis, L.S. Soft-NMS—Improving Object Detection With One Line of Code. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04503. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, H.W. The Hungarian Method for the Assignment Problem. Nav. Res. Logist. Q. 1955, 2, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkres, J. Algorithms for the Assignment and Transportation Problems. J. Soc. Ind. Appl. Math. 1957, 5, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthika, N.; Chandran, S. Addressing the false positives in pedestrian detection. In Electronic Systems and Intelligent Computing: Proceedings of ESIC 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1083–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Lee, H.S. Probabilistic anchor assignment with iou prediction for object detection. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part XXV 16. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 355–371. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, P. Scale-sensitive IOU loss: An improved regression loss function in remote sensing object detection. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 141258–141272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Dayoub, F.; Sunderhauf, N. Varifocalnet: An iou-aware dense object detector. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 8514–8523. [Google Scholar]

- Augasta, M.; Kathirvalavakumar, T. Pruning algorithms of neural networks—A comparative study. Open Comput. Sci. 2013, 3, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, M.; Foroosh, H.; Tappen, M.; Pensky, M. Sparse convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 806–814. [Google Scholar]

- Ashouri, A.H.; Abdelrahman, T.S.; Dos Remedios, A. Retraining-free methods for fast on-the-fly pruning of convolutional neural networks. Neurocomputing 2019, 370, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.