Simple Summary

Mosquito-borne diseases affect millions of people around the world, including Uganda. People therefore need to protect themselves from mosquito bites to stop the spread of disease. One way of keeping mosquitoes at bay is through the use of natural aromatic plant compounds as repellents. These plants release compounds (essential oils) as vapors into the air that keep mosquitoes away, creating a “mosquito-free zone”. In this research, the repelling power of Eucalyptus and lemon grass leaves against mosquitoes and their composition were studied. Leaves from the Nwoya district community, Uganda, were identified and essential oils were obtained by distillation. The oils were tested on Anopheles mosquitoes in an olfactometer in a laboratory. The testing showed that eucalyptus and lemon grass do indeed repel mosquitoes, with eucalyptus showing more effectiveness than lemon grass. A number of compounds were discovered from the gas chromatography–mass spectrophotometric analysis, many of which were similar to other findings but varied in percentage composition. Incorporating Eucalyptus and lemon grass essential oils with spatial activity into control programs can complement existing tools used, such as mosquito nets, offer community-based, low-cost protection, and provide alternatives in the midst of rising parasite, drug, and insecticide resistance.

Abstract

Background: Recently, the use of volatile compounds as spatial repellents have received special attention as a promising strategy for adult An. gambiae s.l control. Anopheles gambiae s.l is a primary vector of malaria, an arthropod-borne disease of global significance. Current strategies for controlling mosquitoes heavily rely on vector control methods. Understanding the responses of these vectors to volatile compounds will be helpful in the formulation of repellants or attractants for control vector populations. This study was conducted in Nwoya district, Uganda, one of the high-malaria-transmission areas in the northern part of Uganda, as one of the ways of reducing contact between the parasite, vector, and malaria outbreak. Materials and Methods: In this study, a laboratory-reared female An. gambiae Kisumu strain from Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) insectaries were used to examine spatial behavior responses of An. gambiae to selected EOs of Eucalyptus grandis and Cymbopogon citratus. Spatial activity responses were measured using a Y-tube olfactometer under controlled conditions using three replicates in various concentrations of the tested EOs. These oils were extracted by steam distillation and the main constituents identified using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Results: Mosquito response curves indicating effective repellency concentrations are reported, as well as the gas chromatography–mass spectrophotometry analysis results. For Eucalyptus grandis, the two components with the highest composition were L-α terpineol and Eucalyptol, while those for Cymbopogon citratus were Lavandulol, methyl ether, and citral. Other components had a percentage composition less than five but they might play a big role in repellent activity against mosquito species. Conclusions: The mosquito repellency results in this study indicate that Eucalyptus grandis and Cymbopogon citratus EOs could be used as mosquito repellents, providing more evidence that natural products have promising lead compounds for further development of botanical spatial repellents. Further characterization of EOs and testing on mosquito behavior related to the prevention of malaria and other vector-borne diseases will promote innovation in vector control and provide new vector control tools that are needed in this era of insecticide resistance.

1. Introduction

Personal protection against mosquito bites is an additional layer of defense in malaria-endemic areas and especially against other mosquito-borne diseases [1,2,3]. This protection is afforded by the application of substances either from chemicals or plants (compounds, extracts, or essential oils) to deter mosquitoes from biting [2,3]. These substances are called mosquito repellents and are sometimes referred to as volatile compounds [4,5,6]. Mosquito repellents work by keeping mosquitoes away from human skin and their source, avoiding contact, bites, and disease [3,4]. Repellents, whether artificial or derived from natural sources, are substances applied to the skin or clothing to stop contact with insects [1,2,3,4]. Mosquito repellent substances are either many plant extracts [7,8,9,10,11,12], plant compounds [8,9], or essential oils [2,3,9,13]. Artificial repellents, typically containing DEET or picaridin, have been shown to offer effective protection [1,11,14]. Various chemical and natural plant repellents, such as Azaradirachta indica (Neem tree), Citrus nardus (Citronella), Cymbopogon citratus (Lemon grass and certain plant extracts), and Eucalyptus grandis (Eucalyptus) have been explored for their potential mosquito-repelling properties, spatial activity, and have shown beneficial protection [2,3,15,16].

Among the many studies performed are those that have demonstrated the insecticidal [17,18], repellent [19,20], larvicidal [21,22,23,24,25], and adulticidal [26,27] effects of various essential oils [26,27,28,29,30], highlighting their potential as eco-friendly mosquito control agents. The composition of many have also been explored [4,15,30]. However, these studies often differ in the materials and methods used [20,26], the type of formulations examined [5,6,17,18,19], and mosquito species tested [20,26,27], leading to variable and sometimes inconclusive results. Many investigations have focused on short-term repellency [23,26,27], and fewer have assessed the spatial efficacy, longevity, or scalability of essential oils in real-world applications [31]. The use of repellent substances in various forms can effectively prevent mosquito bites to human hosts [5,6]. These EOs found in plant compounds [5,6] are used as aromatic plant compound extracts, plant alkaloids, and EOs to control mosquitoes [1,2,3,4]. EOs are manufactured in the plastids and cytoplasm of plant cells, 2-C-methyl-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP), and mevalonic acid pathways, respectively [15,16,17]. They are made up of various oxygenated hydrocarbons, phenylpropenes, and volatile hydrocarbon molecules (terpenes and sesquiterpenes) [16,17,31]. EOs greatly influence mosquito activity in a number of ways, such as by disrupting mosquito-seeking behavior when used as indoor spraying products or applied on human skin [11], plant extracts [5,6,12], compounds [13], and EOs [9,12,14].

EOs influence the neurological system of insects by obstructing GABA-gated chloride channels, octopamine receptors, and the enzyme acetylcholinesterase [18,19]. Monoterpenes constitute above 90% of the essential oils that can cause acetylcholinesterase enzyme activity inhibition in insects [20,32,33,34]. EOs also target the octopaminergic system of insects by blocking octopamine receptors causing acute behavioral effects on insects [35,36,37]. This is accomplished by blocking the rise in cyclic AMP (Adenosine Mono phosphate) levels as a result of the binding of octopamine receptors with a combination of EOs, including eugenol, y-terpineol, and cinnamic alcohol. Monoterpenes found in EOs, such as citronellal, linalool, and estragole, can also inhibit GABA-gated chloride channels [38,39,40]. They do this by first binding to receptor sites, which increases the influx of chloride anions into neurons and causes hyper excitation of the central nervous system, convulsions, and ultimately insect death [41,42].

Most sesquiterpenes and monoterpenes of EOs are known to contain repellent activities [25,26]. For example, ρ-cymene, α-pinene, eugenol, γ pinene, citronellol, citronellal, and camphor, among monoterpenes, are responsible for the repelling of mosquitoes [27,28,35]. On the other hand, sesquiterpenes like α-bisabolol, guaiol, nootkatone, α-cadinol, β-caryophellene, and germacrene have been identified as repellent representatives [13,31]. β-caryophellene expresses high repellent activity against Aedes mosquitoes [27,41]. EOs of Artemisia absinthium have demonstrated harmful effects on populations of Anopheles, Aedes, and Culex mosquito larvae [29]. EOs have also been investigated to cause toxicity and repellency at various developmental stages against adult Anopheles mosquitoes [20,24,41,42,43,44,45]. Ovicidal and larvicidal activities have been observed against An. gambiae and Ae. aegypti from EOs got from Lippa multiflora, Cymbogon proximus, and Ocimum canum [43,46,47]. Combinations of EOs tested on Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes showed that blended EOs yielded stronger repellency than individual EOs [48,49]. Consequently, the major constituents of EOs work together to provide increased insect toxicity, repellant, or larvicidal effects [17,24]. Because they target distinct areas or have different modes of action, EOs with a combination of active components have been shown to diminish resistance in mosquito populations [30,34,50]. Combinations of EOs tested on Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes showed that blended oils yielded stronger repellency than individual EOs. Consequently, the major constituents of EOs work together to provide increased insect toxicity and repellant and larvicidal effects [30,32,34] because they target distinct areas or have different modes. A number of chemical constituents of EOs have been explored and these are responsible for their antioxidative, antimicrobial, and pharmaceutical effects, as well as repellent and insecticidal effects [23,24,25,26,27,30,39].

However, the overdependence and inappropriate application of synthetic pesticides has led to environmental degradation, emergence of resistant strains, and toxicity in mammals despite their effectiveness in controlling vectors. The use of chemically derived mosquito repellents has raised concerns of insecticide resistance, environmental persistence, and potential adverse health effects. As a result, there is growing scientific interest in plant-derived alternatives, particularly EOs, due to their bioactive properties, biodegradability, and relative safety [21]. Despite ongoing efforts to control the disease through various means, the persistence of malaria cases indicates a need for innovative and sustainable vector control strategies. One promising avenue for mosquito control involves exploring the repellent activity of essential oils derived from aromatic plants. This research study addresses these gaps by examining the spatial activity responses of the EOs of Eucalyptus grandis and Cymbopogon citratus against Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes to inform the practicability of their use in integrated vector management strategies.

2. Materials and Methods Study Area

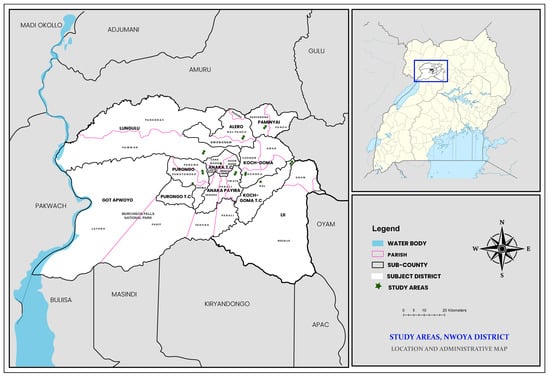

Nwoya District is situated in the northern Ugandan Acholi sub region at 02°38′ N, 32°00′ E. The district is neighbored by six districts: Oyam to the east; Kiryandongo in the southeast; Gulu in the northeast; Masindi to the south; Buliisa to the southwest; and Amuru to the north. The area experiences both wet and dry seasons due to its elevated location at 3220 feet above sea level. The wet season occurs from March to November and is characterized by warm and humid conditions, whereas the dry season occurs from December to February and is usually hot. The months of May, June, August, and October receive the highest amount of rainfall annually. Annual variation in temperature is between 18 degrees Celsius and 36 degrees Celsius [48]. Administratively, Nwoya district has four counties with eleven sub counties (Figure 1). With 133,500 residents and a population density of 37 people per square kilometer, the district is primarily rural, with an estimated 10% annual population growth rate [49]. There are three health center IIIs, fourteen health center IIs, and one main hospital in the district [49].

Figure 1.

Nwoya district (showing the various sampled sub counties).

2.1. Study Design

The study employed a cross-sectional study design supplemented by experimental procedures [51].

2.2. Aromatic Plant Essential Oil Extraction

Plants were collected from various parts of Nwoya district, Uganda. EOs from the fresh leaves of the gathered plants were extracted using the steam distillation method [52]. Fresh leaves were chopped using a knife and placed in a stainless-steel distiller; the plant materials with known mass underwent steam distillation. To prevent direct contact with the plant, materials were packed in a sieved compartment inside the vessel, with two liters of distilled water at the bottom of the stainless-steel vessel. During the steam distillation process, volatile compounds were released from the packed plant material while being cooled by the steam. For three hours of the process, the distillate containing water and plant volatiles was gathered in a separating funnel. By the process of decanting, essential oils were extracted from the top layer of the mixture into a separating funnel. After the extraction process, the residual distillate was sent to liquid–liquid extraction (LLE), it was dried by adding anhydrous magnesium sulfate to 70 mL × 3 HPLC grade n-hexane. The extracted hexane layers were pooled, filtered, and the solvent evaporated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator at 25 °C. The extracted EOs by LLE were obtained by decanting, weighed and pooled together. The mass of EO was divided by the initial mass of plant material and multiplied by 100 to obtain the percentage yield of essential oil obtained. All extracted EOs were kept in glass vials at −20 °C.

2.3. Mosquito Culture

For all experiments conducted in this study, female Anopheles gambiae Kisumu strains from Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) insectaries were used. Batches of approximately 500 eggs were hatched in 33 × 51 × 5 cm pans containing three liters of tap water. Fish flakes were fed to the larvae ad libitum. Pupae were sorted into 200 mL plastic cups and transferred to BugDorm-1 Insect Rearing Cages (30 × 30 × 30 cm, Bug dorm Company, Taichung, Taiwan). Cotton wool containing 10% sucrose solution was put on the top of each cage for feeding adult mosquitoes and changed weekly. Cages were kept inside an insectary room that was maintained at room temperature (average 27 °C) and 70–80% humidity with a light/dark cycle of 12/12, respectively.

2.4. Dilution of Test Compounds

In a 14 mL falcon tube, dilutions of the E. grandis and C. citratus test compounds were prepared using a micropipette for a range of concentrations ranging from 0 to 100% and diluted at intervals of 10% using pure olive oil as a diluent. The tubes were vortexed for sixty seconds before use.

2.5. Spatial Repellency Assay

In the spatial repellency test, the mosquito is elicited to move away from the treated surface without making physical contact [53]. To assemble a spatial repellency assay system, the treatment and control chambers were connected to opposite sides of the clear cylinder using the linking section [54]. With the butterfly valves in both linking sections closed, 25 mosquitoes were transferred into the clear cylinder. After 30 s of acclimatization, the butterfly valves were simultaneously opened and closed again after 10 min. The number of mosquitoes in the treatment and control chambers, as well as the clear cylinder were recorded. A total of three replications (utilizing 25 female mosquitoes in total) were conducted for each treatment (n = 3) and for each concentration (n = 3).

2.6. Repellence Testing Procedure

Mosquito repellence of the test compounds was tested using a standard Y-tube olfactometer [51,55] (Figure 2) in accordance with WHO guidelines [56]. Mosquitoes were starved for three to four hours prior to performing each experiment. The olfactometer was cleaned with 70% ethanol before and between experiments. Repellence assays were performed between 8:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m. with presence of natural light. In the olfactometer, the control center was exposed to pure olive oil while the treatment side was exposed to different EO test compounds.

Figure 2.

Y-tube olfactometer set up used in the study.

2.7. Data Analysis

Spatial repellency was expressed as the proportion of mosquitoes prevented from entering the treatment space in relation to all mosquitoes moving within the system and was calculated from a ‘spatial activity index’ using the equation below.

The spatial activity index varies from −1 to 1: zero indicates no response; −1 indicates that all mosquitoes moved into the treatment chamber, resulting in an attractant response, and 1 indicates that all the mosquitoes moved into the control chamber (away from the treatment source), resulting in a spatial repellent response. If no movement is recorded within the system (i.e., Nt = 0, Nc = 0), the test is valid but the spatial activity index is 0. The spatial activity index was calculated for each replicate, and the mean index for each activity index dosage was analyzed by Probit-plane regression analysis, from which the ED50 and ED90 and the corresponding 95% confidence limits were estimated. The number of replicates, the total number of mosquitoes, and the mean spatial activity index (±standard error) for each activity index dosage and negative control were recorded.

2.8. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analysis

For the general identification of each plant composition, the extracts of individual plants were analyzed by GC-MS of Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA, USA) model (Intuvo 9000 GC connected to 19091S-433UI-INT MS) with a HP-5MS UI column with 30 m length, 250 μm dimensions, and 0.25 μm film thickness. Helium served as the carrier gas and the flow rate was set at 3 mL/min. This process determined the names, molecular weights, and molecular formulae of the components present in the extracts. To ensure validity of the results, the instrument was tuned using perfluorotributylamine (PFTBA) before introduction of the sample to ensure that calibration had not shifted. Additionally, a blank of methanol solvent used for extraction was also injected into the machine. Sample injection was performed using a split-less mode using five microliters as the volume. Temperature at the injector was set at 280 °C. The oven temperature was programmed as follows: 70 °C for 2 min and increased at a rate of 25 °C/min to 150 °C and held for 2 min, then increased at a rate of 3 °C/min to 200 °C and held for 2 min, and finally 8 °C/min to 280 °C and held for 10 min. The ionization voltage of MS-analysis was controlled by the EI procedure with the ion source heat of 280 °C. The total GC-MS running time was 45.867 min. The relative proportional percentage of each component was calculated by comparing its average peak area to the total area. The analysis of the mass spectrum of the GC-MS utilized the National Institute of Standard and Technology (NIST) database, which contains over 62,000 patterns. The spectrum of the identified components was matched against the spectrum of known components stored in the NIST library.

3. Results

3.1. Plant Identification

Plants collected from various parts of Nwoya district (E. grandis and C. citratus) were first properly pressed in plant presses and morphologically identified. Confirmation of these plant species was performed at Makerere University Botany Herbarium, Kampala, Uganda. The identification results showed that the eucalyptus leaves used were Eucalyptus grandis with plant taxonomy as follows: Kingdom: Plantae; Division: Spermatophyta; Subphyllum Angiospermae; Class Dicotyledonae; Order: Myrtales; Family: Myrtaceae; Genus Eucalyptus; Species: grandis W. Hill ex Maiden; while for the lemon grass leaves as Cymbopogon citratus; Kingdom: Plantae; Division: Magnoliophyta; Class: Liliopsida; Subclass: Commelinidae; Order: Poales; Family: Poaceae; Genus: Cymbopogon; Species: citratus (DC. Ex Nees) Stapf.

3.2. Mosquito Confirmation

Confirmation of reared mosquito species at the Uganda Virus Research Institute insectary was conducted using PCR following the protocol of [55]. All mosquito species used were laboratory-reared An. gambiae Kisumu strain.

3.3. Isolating and Fractionating the Essential Oils

The extracted EOs by LLE were obtained by decanting, weighing, and pooling together. About 5–8 mL of EOs were obtained from 1.68 kg of Eucalyptus leaves and 0.86 kg of lemon grass leaves to obtain about 5.6 and 8.4 mls of Eucalyptus essential oils (EEOs) and lemon grass essential oils (LEOs) respectively. These were preserved at −20 °C until needed for further testing.

3.4. Essential Oil Yield

The yields of Eucalyptus essential oils (EEOs) and lemon grass essential oils (LEOs) are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

LEOs obtained from Cymbopogon citratus; temperature (60–70 °C); 3 h per run.

Table 2.

EEOs obtained from Eucalyptus grandis, temperature (60–70 °C), 3 h per run.

3.5. GC-MS Analysis

The EEOs and LEOs of the leaves from E. grandis and C. citratus were identified by GC-MS analysis to establish the chemical compounds present. The percentage composition of each major compound was determined based on peak area normalization in the GC-MS chromatogram. Results were adjusted according to the NIST library. The chromatographs of both oils showed 18 and 19 peaks for E. grandis and C. citratus, respectively, and these were interpreted as shown in Table 3. Analysis of EEOs showed that the first compounds were L-alpha-terpineol (33.2%) and Eucalyptol (18%), and the rest were less than 10% and for Lemon grass. The LEOs were Lavandulol, methyl ether (47.2%), and Citral (12.96%) as the main compounds (Table 3). The minority compounds presenting less than 10% composition are also shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Chemical composition of compounds after gas chromatography–mass spectrophotometer (GC-MS) analysis.

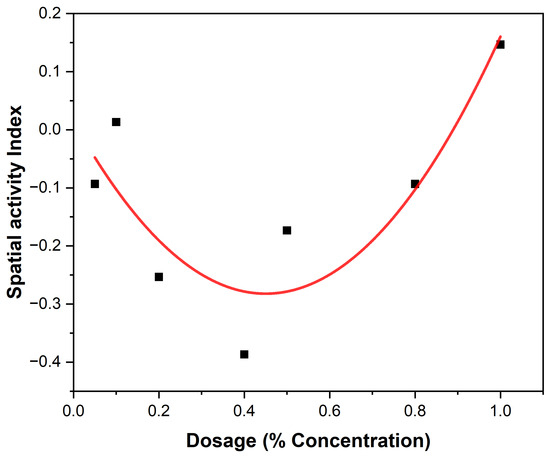

3.6. Repellency and Spatial Repellent Index

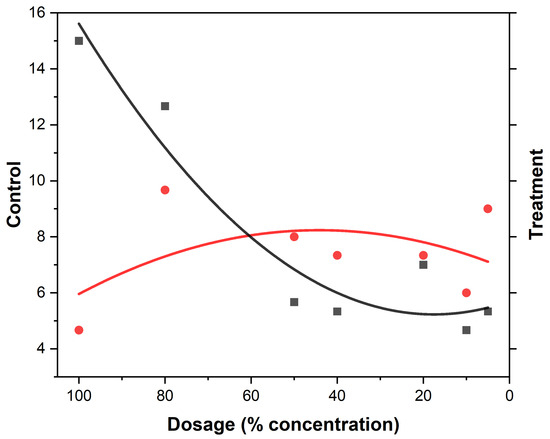

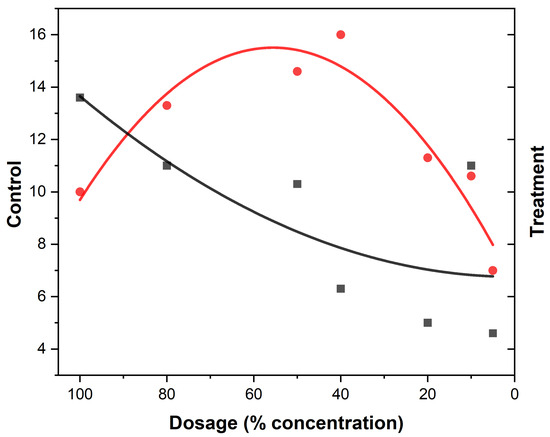

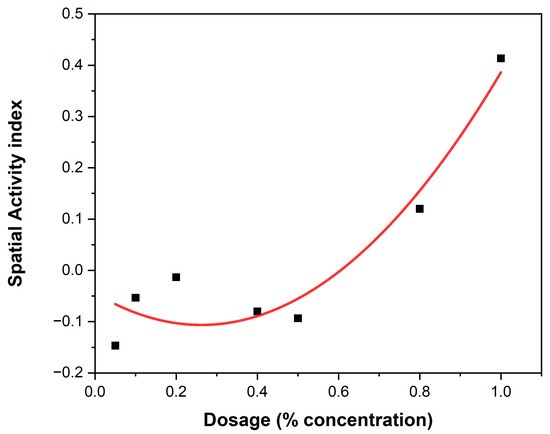

The behavioral responses to essential oil concentrations of EEO and LEO are presented (Table 4 and Table 5). Variations among the different concentration levels of EOs are revealed (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The most notable response in An. gambiae was observed at a concentration of 40% EEO (Table 4) while that of LEO was observed at 80% (Table 5), suggesting mosquitoes were more sensitive to the active ingredients in the EEOs than in LEOs. The spatial activity index varies from −1 to 1:0 indicates no response; −1 indicates that all mosquitoes moved into the treatment chamber, resulting in an attractant response, and 1 indicates that all the mosquitoes moved into the control chamber (away from the treatment source), resulting in a spatial repellent response. Both EEOs and LEOs showed both negative and positive levels of spatial repellency with no statistically significant variances p ≤ 0.05). Highest spatial activity was observed at 16 for the EEO at a concentration of 40% and 11 for lemon grass at a concentration of 80%. The highest spatial repellency against An. gambiae was observed at a concentration of 40% (SAI = −0.39) for EEOs, and 80% (SAI = 0.12) for LEOS, both showing significant differences from the control group (p < 0.05). Forty percent and 80% compositions for EEOs and LEOs, respectively, demonstrated the most promising spatial activity index against An. gambiae. The effective dose composition of EEO at 50% ED50 was 45.49% and at 90, ED90 was 51.35%. For C. citratus, no LEO ED50 detection was observed at 50% and at 90% the ED90 was 0.052%.

Table 4.

Response of female Anopheles gambiae to EEOs.

Table 5.

Response of female Anopheles gambiae to LEOs.

Figure 3.

Lemon grass mosquito repellency. The black squares represent the treatment (mosquito responses being repelled) to LEOs and the red dots the control (attraction to the oil). The curves represent the gradient at the different EO compositions.

Figure 4.

Eucalyptus mosquito repellency. The red dots represent the treatment (mosquito responses being repelled) to EEOs and the black squares the control (attraction to the oil) at different concentrations of the EOs. The red curve indicates the treatment while black curve are the control.

The spatial activity index of EEO and LEO on An. gambiae are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, showing varying spatial activity indices with responses varying between the negative and positive values. Both EEOs and LEOs showed both negative and positive levels of spatial repellency with no statistically significant variances (p ≤ 0.05). The highest activity was observed at 16 for the EEO at a concentration of 40% and for lemon grass this was 11 at 80%. The highest spatial repellency against An. gambiae was observed at a concentration of 40% (SAI = −0.39) for EEOs, and 80% (SAI = 0.12) for LEOS, with both showing significant differences from the control group (p < 0.05). Forty percent and 80% compositions for the EEOs and LEOs, respectively, demonstrated the most promising spatial activity index against An. gambiae.

Figure 5.

EEOs spatial activity index.

Figure 6.

LEOs spatial activity index.

4. Discussion

For many generations, natural plants and their products have been used to drive away pest insects as well as for human protection from bites [56,57,58,59]. They have been planted around homes for protection from bites of various insects. Plant extracts have been further developed; first, by different means of extraction and by designing products that are applied to the human skin for protection from insect bites [56,57,58,59]. These products obtained from natural plants could either be crude extracts, essential oils [60,61], or further synthesized into useful products [57,62]. Natural repellents through the release of various compounds offer personal protection against many insect bites [1,63].

Our study established the spatial activity and composition of two EOs obtained from the leaves of aromatic plants E. grandis and C. citratus. A significant increase in the attraction response of An. gambiae Kisumu strain to experimental EEOs and LEOs following exposure in the Y-tube olfactometer treatment chamber compared to the controls was similar to what has been observed in some studies [17,19,20,54,57]. More importantly, from this study, the findings have advanced our understanding of the spatial activity of the EEOs and LEOs as well as the chemical compounds present in E. grandis and C. citratus as aromatic plants. Increase in spatial activity index was observed with an increase in the concentration of both EOs. The activity dosage ranged between 40 and 80%, which indicated that mosquitoes were influenced by the compounds emitted by both oils. Both EOs showed reasonable repellency. A similar repellency for EEO was reported by [58] and for LEO at 60%, which is almost similar to what we observed. The minimum application volume to be effective was slightly different for both oils being slightly lower for the EEO than LEO. These observed responses in mosquito behavior may be due to the differences in the composition of the plants and also to a hyperactive olfactory response of female Anopheles mosquitoes elicited by the EO compounds [58]. The findings support a heightened sensory mechanism of action as there was an increase in the number of mosquitoes landing in the treatment portion of the tube overall and fewer mosquitoes in the controls as the concentration of the essential oils increased. Heightened olfactory acuity can result from extensive grooming, especially of the antennae [64,65]. In terms of the effective dosage to be applied for the EEO and LEO, E. grandis showed a much higher percentage at ED50 and ED90 than C. citratus. For C. citratus, the LEO ED50 could not be detected and at ED90 it was very low. This may suggest that LEOs might have a slightly higher potency than the EEOs. However, more studies need to be conducted to ascertain these findings because this study did not specifically isolate the different compounds for spatial response activities.

From the few studies presented on spatial activity, variations in the attraction of mosquito species and insects to different repellents and attraction are shown [62,66,67,68]. Essential oil molecules may disrupt the insect’s ability to detect host-seeking chemical signals and reduce bites by binding to the mosquito’s olfactory receptors [66]. There could also be a possibility of the mosquito’s receptors interacting with the essential oil molecules, which could trigger a repellent response in the mosquito, causing it to avoid the treated area or individual [35]. The precise mechanism by which EOs disrupt the mosquito’s olfactory system may vary depending on the specific compounds present in the oil and their interactions with the complex array of receptors involved in host-seeking behavior [66,69,70,71,72].

In a slightly different tone, only a few studies have investigated the volatile oil composition of E. grandis and C. citratus varieties and some representations from parts of the world include those performed by [70,73]. The fresh leaves produced pale yellow EOs with a yield between 0.7 for EEO and 1.7 for LEO, which is in accordance with what has been reported for EEOs and LEOs in plants from related studies [13,72,74,75]. Our composition is generally consistent with the chemical profiles of the EOs of some of the EEOs and LEOs from related plant species grown in other countries, where a majority of these were found in Indonesia, Turkey, Cyprus, and China [72,76]. Composition of EEOs differed slightly from what was discovered in [37]; however, the species were different and the climate and environmental conditions were likely slightly different from ours.

For the GCMS composition of the EOs, 18 and 19 peaks were obtained after GCMS analysis in EEOs and LEOs. Some of the EOs presented are similar to what has been found in other studies but the percentage composition is very different. Also the composition of these compounds varies from what was found in other studies [70,72,73]. This could be that the plant species are grown in different climatic zones and are presented with different environmental factors. It could be that the species difference is a contributing factor, along with the age of the plant that was harvested, the chemical and physical conditions of the growth environment, as well as the season of harvesting (season, location, climate, soil, and developmental stage) [68,71,72]. All these factors may have played a part in the presentation of different composition of EEOS and LEOS.

Alpha-terpineol in Eucalyptus had the highest composition in the EEOs. It is one of the most popular fragrant ingredients used in household cleaning products, perfumes, cosmetics, and is used to flavor beverages and foods [74,75,76]. It also has several important medicinal and biological properties [70,75,76,77,78,79] Eucalyptol, which was the second highest, is commonly used for manufacturing of cosmetic products and has many health and biological beneficial uses as well [70]. For C. citratus, the LEOs, Lavandulol-methyl-ether had the highest composition, though it was not as highly explored as its other components which could also have several important medicinal and biological properties. Citral, which was the second highest in the LEOs, is commonly used for manufacturing of cosmetic products, and has many health and biological beneficial uses as well [77,78,79]. Citral is well-known for its strong, refreshing lemon-like scent and is widely used in perfumery and cosmetics for its aromatic properties [35]. For the rest of the minority compounds found in the EEOs and LEOs, which were not examined, they could present a potential repellent action, which could still have had a significant effect on the spatial behavior of the mosquitoes. For example, 1,8-cineole and limonene could have been present in low composition but might have played a significant role in the spatial activities. Therefore, there was a reduction in mosquito numbers as mosquitoes refused (were repelled) to perch on the treatment arm that had been oiled with EEOs and LEOs due to terpenoids and other class contents that can be toxic for mosquitoes. Eucalyptus grandis and C. citratus EOs both contained a variety of terpenes and sesquiterpenes. Both EOs showed high levels of composition which was dominated by monoterpenes. For Eucalyptus, eucalyptol, also known as 1,8-Cineole, was very much present though it was not the highest in composition. For C. citratus, citral, which is a monoterpene, was present. Other compounds belonging to other groups were in low in composition. The components were not isolated singly so each individual‘s effect was not studied separately. This is an area for further exploration.

5. Limitations

This study tested only the activity of aromatic essential oils from plants on one species of mosquito but most probably the product can. Further work may be conducted on other mosquito species. This experiment was conducted on lab-reared mosquitoes that may exhibit different behaviors compared to natural field populations. This needs to be further explored and tested in the semi field experiments and on human subjects. Only two products were tested for the effective dosage and spatial responses; there are many more compounds that could be tested. These may also have spatial repellent chemicals that could affect mosquito behavior differently so further studies are recommended. Specifically, from these results, a broader functionality of volatile repellents beyond their current application (to prevent human biting) could facilitate the development and expanding label uses of available products. It is hoped that this may further incentivize the discovery, development, and evaluation of new spatial repellent products for mosquito and other arthropod-borne disease prevention. In summary, both EEOs and LEOs offer a promising approach for spatial mosquito control, particularly against An. gambiae species. Their ability to deter mosquitoes from entering and feeding can significantly reduce the risk of malaria transmission.

6. Conclusions

Mosquitoes were repelled by the EEO and LEO test compounds. GCMS analysis showed that the clear yellow oil of EEOs contained 18 compounds, with the highest being L-alpha-terpineol while for the LEOS, a clear yellow color was also presented, containing 19 compounds with the most prevalent compound being Lavandulol-methyl-ether. Both EEOs and LEOs offer a promising approach for spatial mosquito control, particularly against the An. gambiae species and could be further developed into useful products to protect humans and animals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.K.; Methodology, M.A.K., A.B.K. and N.M.M. Validation, A.B.K. and C.B.; Formal Analysis, M.A.K. and F.K.; Investigation, A.B.K. and F.K.; Resources M.A.K. and A.B.K.; Data Curation, M.A.K., N.M.M. and A.B.K.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.A.K.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.A.K., N.M.M. and A.B.K.; Visualization, M.A.K., N.M.M. and A.B.K.; Supervision, M.A.K. and N.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by the 8th Call Competitive Research grant of Kyambogo University, Kampala, Uganda. The funding agencies had no role in the study design, data collection, analyses, interpretation of findings, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to publish the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the (Research Ethics Committee) of Clarke University Ethical considerations no. CLARKE-2025-1601 and from Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST).

Data Availability Statement

All data have been included in the submitted manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Competitive Research grants committee, Kyambogo University for providing the funding; Departments of Biological Sciences and Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Kyambogo University; for providing facilities and materials to support the experimentations and the insectary team; at the Uganda Virus Research Institute, Department of Entomology, for providing insectary facilities and conducting of the testing. Last but not least, Birungi Solome of the Department of Food and drugs, the Directorate of Government Analytical Chemists (DGAL), Wandegeya for carrying out GCMS analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Asadollahi, A.; Khoobdel, M.; Zahraei-Ramazani, A.; Azarmi, S.; Mosawi, S.H. Effectiveness of plant-based repellents against different Anopheles species: A systematic review. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera-Gahona, M.; Peña-Moreno, C.; Quiñones-Sobarzo, N.; Weinstein-Oppenheimer, C.; Guerra-Zúñiga, M.; Collao-Ferrada, X. Repellents against Aedes aegypti bites: Synthetic and natural origins. Front. Insect Sci. 2025, 4, 1510857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.R.M.; Eduardo Ricci-Júnior, E. An approach to natural insect repellent formulations: From basic research to technological development. Acta Trop. 2020, 212, 105419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y. Essential Oils as Repellents against Arthropods. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2, 6860271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J.H. Chemical and plant-based insect repellents: Efficacy, safety, and toxicity. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2016, 27, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavela, R.; Benelli, G. Ethnobotanical knowledge on botanical repellents employed in the African region against mosquito vectors—A review. Exp. Parasitol. 2016, 167, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, M.F.; Moore, S.J. Plant-based insect repellents: A review of their efficacy, development and testing. Malar. J. 2011, 10 (Suppl. S1), S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afify, A.; Potter, C.J. Insect repellents mediate species-specific olfactory behaviours in mosquitoes. Malar. J. 2020, 19, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olonisakin, A. Essential oil composition and biological activity of Cymbopogon citratus from Keffi, Nigeria. J. Chem. Soc. 2010, 35, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Dickens, C.; Bohbot, J.D. Mini review: Mode of action of mosquito repellents. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2013, 106, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Z.; Leal, W.S. Mosquitoes smell and avoid the insect repellent DEET. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13598–13603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Chowdhury, N.; Chandra, G. Plant extracts as potential mosquito larvicides. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011, 135, 581–598. [Google Scholar]

- Alphian, Z.; Marpaung, H.; Taufik, M.; Andriayani; Lanny, S.; Samosir, S.J. GC-MS Analysis of Chemical Contents and Physical Properties of Essential Oil of Eucalyptus grandis from PT. Toba Pulp Lestari. Asian J. Chem. 2019, 31, 2319–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaenson, T.G.T.; Palsson, K.; Borg-Karlson, A.-K. Evaluation of Extracts and Oils of Mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) Repellent Plants from Sweden and Guinea-Bissau. J. Med. Entomol. 2006, 43, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiekh, R.A.E.; Atwa, A.M.; Elgindy, A.M.; Mustafa, A.M.; Senna, M.M.; Alkabbani, M.A.; Ibrahim, K.M. Therapeutic applications of eucalyptus essential oils. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, D.P.; Damasceno, R.O.S.; Amorati, R.; Elshabrawy, H.A.; de Castro, R.D.; Bezerra, D.P.; Nunes, V.R.V.; Gomes, R.C.; Lima, T.C. Essential Oils: Chemistry and Pharmacological Activities. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owolabi, T.A.; Okubor, P.C.; Danga, J.; Onimisi, I. Insecticidal effect of Essential Oils of Citrus limon, Cymbopogon citratus and Syzygium aromaticum and their Synergistic Combinations Against Anopheles Mosquitoes. Acta Biol. Slov. 2025, 68, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radünz, A.L.; Radünz, M.; Bizolloa, A.R.; Tramontina, M.A.; Radünz, L.L.; Mariotd, M.P.; Tempel-Stumpfd, E.R.; Calistoe, J.F.F.; Zaniole, F.; Albeny-Simõese, D.; et al. Insecticidal and repellent activity of native and exotic lemon grass on Maize weevil. Braz. J. Biol. 2024, 84, e252990. [Google Scholar]

- Aïzoun, N.; Honvoh, E.; Codjia, S.; Chougourou, D. Repellent activities of ethanolic extract of Cymbopogon citratus (Poaceae) and Ocimum basilicum L. (Lamiaceae) leaves against Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Dogbo district in south-western Benin, West Africa. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 30, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, Z.; Amani, A.; Basseri, H.R.; Kazemi, S.H.M.; Sedaghat, M.M.; Azam, K.; Azizi, M.; Amirmohammadi, F. Repellent Efficacy of Eucalyptus globulus and Syzygium aromaticum Essential Oils against Malaria Vector, Anopheles stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae). Iran J. Public Health 2021, 50, 1668–1677. [Google Scholar]

- Nazmin, F.; Barek, M.A.; Miah, A.M.; Hossen, S.; Islam, M.S.; Ahmed, J. Mosquito repellent and larvicidal activity of essential oils of aromatic plant growing in Bangladesh: A review. Clin. Phytosci. 2025, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osanloo, M.; Sedaghat, M.M.; Sanei-Dehkordi, A.; Amir Amani, A. Plant-Derived Essential Oils; Their Larvicidal Properties and Potential Application for Control of Mosquito-Borne Diseases. Galen Med. J. 2019, 8, e1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rini, P.; Rini, P. Chemical compositions and repellent activity of Eucalyptus tereticornis and Eucalyptus deglupta essential oils against Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito. Thai J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 41, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, S.M.; Moustafa, M.A.M.; Fónagy, A.; Kamel, O.M.H.M.; Abdel-Haleem, D.R. Chemical composition of four essential oils and their adulticidal, repellence, and field oviposition deterrence activities against Culex pipiens L. (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, M.; Benelli, G. α-Humulene and β-elemene from Syzygium zeylanicum (Myrtaceae) essential oil: Highly effective and eco-friendly larvicides against Anopheles subpictus, Aedes albopictus, and Culex tritaeniorhynchus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 2771–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sarar, A. Chemical composition, adulticidal and repellent activity of essential oils from Mentha longifolia L. And Lavandula dentata L. Against Culex pipiens L. J. Plant Prot. Path 2014, 5, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonwera, M. Mosquito repellent from Thai essential oils against dengue fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti L.) and filaria mosquito vector (Culex quinquefasciatus Say). J. Agric. Tech. 2015, 11, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pavela, R.; Pavela, R. Essential oils for the development of eco-friendly mosquito larvicides: A review. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 76, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B.; Tyagi, S.; Aarim, M.; Khan, M.S.; Khan, A.F. Biosynthesis of Essential Oil in Aromatic Plant Species: A review. Biomed. Biosci. Adv. 2024, 1, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manh, H.D.; Hue, D.T.; Hieu, N.T.T.; Tuyen, D.T.T.; Tuyet, O.T. The MosquitoLarvicidal Activity of Essential Oils from Cymbopogon and Eucalyptus Species in Vietnam. Insects 2020, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyita, A.; Sari, R.M.; Astuti, A.D.; Yasir, B.; Rumata, N.R.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Simal-Gandara, J. Terpenes and terpenoids as main bioactive compounds of essential oils, their roles in human health and potential application as natural food preservatives. Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukarram, M.; Choudhary, S.; Khan, M.A.; Poltronieri, P.; Khan, M.M.A.; Ali, J.; Kurjak, D.; Shahid, M. Lemongrass Essential Oil Components with Antimicrobial and Anticancer Activities. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, H.; Song, Q. Lemon grass essential oil and its major component citronellol: Evaluation of larvicidal activity and acetylcholinesterase inhibition against Anopheles sinensis. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabakaran, P.; Sivasubramanian, C.; Veeramani, R.; Prabhu, S. Review Study on Larvicidal and Mosquito Repellent Activity of Volatile Oils Isolated from Medicinal Plants. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 2, 3132–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassolé, I.H.N.; Juliani, H.R. Essential oils in combination and their antimicrobial properties. Molecules 2012, 17, 3989–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, M.; Rogalska, J.; Wyszkowska, J.; Stankiewicz, M. Molecular Targets for Components of Essential Oils in the Insect Nervous System—A Review. Molecules 2018, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, V.; Islam, J.; Agnihotri, A.; Goswani, D.; Rabha, B.; Talukdar, P.K.; Dhiman, S.K.; Chattopadhyay, P.; Veer, V. Repellent efficacy of some essential oils against Aedes albopictus. J. Parasit. Dis. Diagn. Ther. 2016, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bekele, D. Review on insecticidal and repellent activity of plant products for malaria mosquito control. Biomed. Res. Rev. 2018, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.R.; Dubey, R.C.; Saini, S. Phytochemical and antimicrobial studies on essential oils of some aromatic plants. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 4364–4368. [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan, M.; Benelli, G. One-pot green synthesis of silver nano crystals using Hymenodictyon orixense: A cheap and effective tool against malaria, chikungunya and Japanese encephalitis mosquito vectors? RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 59021–59590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, M.; Kadaikunnan, S.; Alharbi, N.S.; Benelli, G. Acute toxicity and repellent activity of the Origanum scabrum Boiss. & Heldr. (Lamiaceae) essential oil against four mosquito vectors of public health importance and its biosafety on non-target aquatic organisms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 23228–23238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnankiné, O.; Bassolé, I.H.N. Essential Oils as an Alternative to Pyrethroids’ Resistance against Anopheles Species Complex Giles (Diptera: Culicidae). Molecules 2017, 22, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillij, Y.G.; Gleiser, R.M.; Zygadlo, J.A. Mosquito repellent activity of essential oils of aromatic plants growing in Argentina. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 2507–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndou, T.T.; von Wandruszka, R.M.A. Essential oils of South African Eucalyptus species (Myrtaceae). S. Afr. Tydskr. Chern. 1986, 39, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wangrawa, D.W.; Chandrasegaran, K.; Upshur, F.; Borovsky, D.; Sharakhov, I.V.; Inauger, C.; Badolo, A.; Sanon, A.; Lahondère, C. Behavioral response of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) to essential oils of Cymbopogon nardus (L.) Eucalyptus camaldulensis (Dehnh) and their blend in Y-maze olfactometer. Front. Trop. Dis. 2024, 5, 1443952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasanah, L.U.; Ariviani, S.; Purwanto, E.; Praseptiangga, D. Chemical composition and citral content of essential oil of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf) leaf waste prepared with various production methods. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 19, 101570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajilov-Krstev, T.; Jovanović, B.; Jović, J.; Ilić, B.; Miladinović, D.; Matejić, J.; Rajković, J.; Dorđević, L.; Cvetković, V.; Zlatković, B. Antimicrobial, antioxidative, and insect repellent effects of Artemisia absinthium essential oil. Planta Med. 2014, 80, 1698–1705. [Google Scholar]

- Weather Spark. Available online: https://weatherspark.com/countries/UG (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- UBOS 2014 Statistical Abstract. Available online: www.ubos.org (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Boutekedijiret, C.; Bentahar, R.; Belabbes, J.; Bessire, J.M. Extraction of rosemary essential oil by steam distillation and hydrodistillation. Flavour. Fragr. J. 2003, 18, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, J.P.; Achee, N.L.; Sardelis, M.R.; Chauhan, K.R.; Roberts, D.R. A novel high-throughput screening system to evaluate the behavioral response of adult mosquitoes to chemicals. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2005, 21, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achee, N.L.; Bangs, M.J.; Farlow, R.; Killeen, G.F.; Lindsay, S.; Logan, J.G.; Moore, S.J.; Rowland, M.; Sweeney, K.; Torr, S.J.; et al. Spatial repellents: From discovery and development to evidence-based validation. Malar. J. 2012, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.A.; Brogdon, W.G.; Collins, F.H. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993, 49, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines for Efficacy Testing of Spatial Repellents; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.; Bangonan, L.; Xue, R.-D.; Talbalaghi, A. Evaluation of essential oils as spatial repellents against Aedes aegypti in an olfactometer. J. Am. Mosq. Cont. Ass. 2022, 38, 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique, A.; Naeem, J.; Ang, K.L.; Abid, S.; Xu, Z.; Khawar, M.T.; Saleemi, S.; Abdullah, M.; Adeel. Cinnamon and Eucalyptus Extracts: A Promising Natural Approach for Durable Mosquito-Repellent Fabrics with Multifunctionality. ACS Omega 2024, 26, 41468–41479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.I.; Kim, S.-I.; Jung, J.W.; Ilyasov, R.A.; Jang, D.; Lee, S.-H.; Kwon, H.W. Spatial releasing properties and mosquito repellency of cellulose-based beads containing essential oils and vanillin. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2019, 22, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.S.; Almeida, M.M.; Salazar, M.d.L.A.R.; Pires, F.C.S.; Bezerra, F.W.F.; Cunha, V.M.B.; Cordeiro, R.M.; Olivo Urbina, G.R.; da Silva, M.P.; Souza e Silva, A.P.; et al. Potential of Medicinal Use of Essential Oils from Aromatic Plants; InTech: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasanthan, A.; Senthilkumar, K.L.; Gokulan, P.D.; Vignesh, A.; Vishnu, V. Formulation and evaluation of mosquito repellent cream by eucalyptus oil. Int. Res. J. Mod. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2023, 5, 2366–2369. [Google Scholar]

- Trigg, J.K. Evaluation of a eucalyptus-based repellent against anopheles spp. in Tanzania. J. Am. Mosq. Cont. Ass. 1996, 12, 243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Onen, H.; Luzala, M.M.; Kigozi, S.; Sikumbili, R.M.; Muanga, C.-J.K.; Zola, E.N.; Wendji, S.N.; Buya, A.B.; Balciunaitiene, A.; Viškelis, J.; et al. Mosquito-Borne Diseases and Their Control Strategies: An Overview Focused on Green Synthesized Plant-Based Metallic Nanoparticles. Insects 2023, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Alotaibi, B.M. Essential oils of some medicinal plants and their biological activities: A mini review. J.Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appll. Sci. 2023, 9, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böröczky, K.; Wada-Katsumata, A.; Batchelor, D.; Zhukovskaya, M.; Schal, C. Insects groom their antennae to enhance olfactory acuity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 110, 3615–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukkanon, C.; Karpkird, T.; Saeung, M.; Leepasert, T.; Panthawong, A.; Suwonkerd, W.; Bangs, M.J.; Chareonviriyaphap, T. Excito-repellency activity of Andrographis paniculata (Lamiales: Acanthaceae) against colonized mosquitoes. J. Med. Entomol. 2020, 57, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, J.L.T.; Moscoso, K.E.P.; Salas, I.F.; Achee, N.L.; Grieco, J.P. Spatial repellency and other effects of transfluthrin and linalool on Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. J. Vec. Ecol. 2019, 44, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, E.J.; Coats, J.R. Current and future repellent technologies: The potential of spatial repellents and their place in mosquito-borne disease control. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirisopa, P.; Leepasert, T.; Karpkird, T.; Nararak, J.; Thanispong, K.; Ahebwa, A.; Chareonviriyaphap, T. High-Throughput Screening System Evaluation of Andrographis paniculata (Burm.f.) Extracts and Their Fractions against Mosquito Vectors. Insects 2024, 15, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Yin, M.; Liu, M.; Gao, W. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of variations in the essential leaf oil of 6 Eucalyptus Species and allelopathy of mechanism 1,8-cineole. Ciência Rural 2023, 53, e20210687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocheng, F.; Bwanga, F.; Joloba, M.; Softrata, A.; Azeem, M.; Pütsep, K.; Borg-Karlson, A.K.; Obua, C.; Gustafsson, A. Essential Oils from Ugandan Aromatic Medicinal Plants: Chemical Composition and Growth Inhibitory Effects on Oral Pathogens. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, 230832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Torres, A.G.; López-Castillo, G.N.; Marín-Torres, J.L.; Portillo-Reyes, R.; Luna, F.; Baca, B.E.; Sandoval-Ramírez, J.; Carrasco-Carballo, A. Cymbopogon citratus Essential Oil: Extraction, GC–MS, Phytochemical Analysis, Antioxidant Activity, and in Silico Molecular Docking for Protein Targets Related to CNS. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 5164–5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainat, R.; Mushtaq, Z.; Nadeem, F. Derivatization of Essential Oil of Eucalyptus to Obtain Valuable Market Products—A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Chem. Biochem. Sci. 2019, 15, 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Polito, F.; Fratianni, F.; Nazzaro, F.; Amri, I.; Kouki, H.; Khammassi, M.; Hamrouni, L.; Malaspina, P.; Cornara, L.; Khedhri, S.; et al. Essential Oil Composition, Antioxidant Activity and Leaf Micromorphology of Five Tunisian Eucalyptus Species. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniran, O.I.; Fabiyi, E. A cream formulation of an effective mosquito repellent: A topical product from lemongrass oil (Cymbopogon citratus) Stapf. J. Nat. Prod. Plant Resour. 2012, 2, 322–327. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, C.; Yee Ho, L.; Wu, T.-Y.; Sit, N.M. Chemical composition and bioactivities of Eucalyptus essential oils from selected pure and hybrid species: A review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 120118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.L.; Wang, W.; Wang, G. Recent updates on bioactive properties of α-terpineol. J. Essentail Oil Res. 2023, 35, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M.; Sheikholeslami, M.A.; Ghafghazi, S.; Pouriran, R.; Parvardeh, S. Analgesic effect of α-terpineol on neuropathic pain induced by chronic constriction injury in rat sciatic nerve: Involvement of spinal microglial cells and inflammatory cytokines. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 22, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gouveia, D.N.; Costa, J.S.; Oliveira, M.A.; Rabelo, T.K.; e Silva, A.M.D.O.; Carvalho, A.A.; Miguel-dos-Santos, R.; Lauton-Santos, S.; Scotti, L.; Scotti, M.T.; et al. α-Terpineol reduces cancer pain via modulation of oxidative stress and inhibition of iNOS. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 105, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solon, I.G.; Santos, W.S.; Branco, L.G.S. Citral as an anti-inflammatory agent: Mechanisms, therapeutic potential, and perspectives. Pharmacol. Res. Nat. Prod. 2025, 7, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, E.; Kozłowska, M.; Gruczyńska-Sękowska, E.; Kowalska, D.; Tarnowska, K. Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) Essential Oil: Extraction, Composition, Bioactivity and Uses for Food Preservation—A Review. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019, 69, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).