Abstract

Laser cladding is an effective surface engineering technique to enhance the high-temperature performance of metallic materials. In this work, a Cr-Al-C composite coating was in situ fabricated on H13 steel by laser cladding to alleviate the performance degradation of H13 steel under severe thermomechanical conditions, particularly in high-temperature piercing applications. The phase composition, microstructure, microhardness, high-temperature oxidation behavior, and tribological performance of the coating were systematically investigated. The coating is mainly composed of a B2-ordered Fe-Cr-Al phase reinforced by uniformly dispersed M3C2/M7C3-type carbides, which provides a synergistic combination of oxidation protection and mechanical strengthening, offering a microstructural design that differs from conventional Cr-Al or Cr3C2-based laser-clad coatings. Cyclic oxidation tests conducted at 800–1000 °C revealed that the oxidation behavior of the coating followed parabolic kinetics, with oxidation rate constants significantly lower than those of the H13 substrate, attributed to the formation of a dense and adherent Al2O3/Cr2O3 composite protective scale acting as an effective diffusion barrier. Benefiting from the stable oxide layer and the thermally stable carbide-reinforced microstructure, the wear rate of Cr-Al-C coating is significantly reduced compared to H13 steel. At room temperature, the wear rate of the coating is 6.563 × 10−6 mm3/(N·m), about two orders of magnitude lower than 8.175 × 10−4 mm3/(N·m) for the substrate. When the temperature was increased to 1000 °C, the wear rate of the coating remained as low as 5.202 × 10−6 mm3/(N·m), corresponding to only 1.9% of that of the substrate. This work demonstrates that the Cr-Al-C laser-cladded coating can effectively improve the high-temperature oxidation resistance and wear resistance of steel materials under extreme service conditions.

1. Introduction

The piercing plug is a critical component in the seamless steel tube forming process, and its performance directly influences the billet quality, piercing efficiency, and energy consumption. During piercing, the plug is subjected to high temperatures, heavy loads, and complex cyclic stresses, causing severe wear and failure, which significantly increases consumption and production costs while reducing productivity and product quality. Therefore, improving the performance and lifespan of the piercing plug is essential for producing seamless steel tubes [1,2,3].

Piercing plugs are commonly manufactured using H13 steel. H13 steel is a typical Cr-Mo-V hot-work tool steel containing about 5 wt.% Cr, exhibiting good strength as well as certain wear and oxidation resistance. However, under high-temperature piercing conditions, the surface of H13 steel is prone to severe wear and oxidation, leading to performance degradation and shortened service life, thus limiting its application under extreme conditions [4]. Therefore, developing surface-strengthening coatings with excellent wear resistance and oxidation resistance has become a key approach to improving the service performance of H13 piercing plugs.

To improve the performance of H13 steel under harsh service conditions, researchers have adopted various advanced surface strengthening technologies, including laser cladding, overlay welding, thermal spraying, PVD (physical vapor deposition), and CVD (chemical vapor deposition) [1]. Among them, laser cladding, as an efficient surface modification technique, employs a high-energy-density laser beam to melt alloy or composite powders and rapidly solidify them onto the substrate surface. It can significantly enhance the wear resistance and oxidation resistance of surface layers without altering the substrate microstructure, while enabling precise control of coating composition and thickness. Compared with traditional coating processes, laser cladding exhibits superior performance in harsh environments such as high temperatures and high stresses, depending largely on the cladded material composition [5,6].

In the laser cladding process, the selection of raw powders plays a decisive role in the coating microstructure, properties, and metallurgical bonding with the substrate [6]. Cr3C2 is a commonly used reinforcing phase, which can undergo partial decomposition in the melt pool and react with Fe and Cr to form dispersed strengthening carbides, thereby significantly enhancing the hardness and wear resistance of the coating [7]. Feng et al. [8] compared the effects of different Cr3C2 contents on the coating structure and wear resistance in Fe3Al-Cr3C2 laser-cladded coatings, and found that the coating hardness increased with increasing Cr3C2 content, while the sample containing 15 wt.% Cr3C2 exhibited the lowest friction coefficient and wear rate. Similarly, Chen et al. [9] added 10% Cr3C2 into a Stellite 6-Cr3C2-WS2 composite coating prepared on H13 steel, and their results showed that the friction coefficient of the coating decreased by 30% compared with the substrate, confirming the significant role of carbide reinforcement in improving friction and wear behavior.

In addition to the partial decomposition of Cr3C2 during cladding to generate dispersed carbides such as Cr7C3 and Cr23C6 that enhance coating hardness and wear resistance, the Cr element itself also plays a crucial role in microstructural formation and high-temperature service behavior of the coating system. Numerous studies showed that in Ni-Cr and Fe-Cr laser-cladded alloy systems, increasing Cr content led to optimized phase structures and improved hardness/strength, and also promoted the formation of dense and continuous metallurgical bonding interfaces with the steel substrate, effectively eliminating pores or cracks [10,11,12]. Moreover, under high-temperature conditions, Cr preferentially oxidizes to form a dense Cr2O3 protective scale, providing an early oxidation barrier and delaying oxygen diffusion toward the substrate. Zhang et al. [13] reported that WC/Co-Cr exhibited excellent high-temperature oxidation resistance, significantly superior to H13 steel. However, Cr2O3 might undergo chromium volatilization or chromate formation at above ~1000 °C, leading to scale breakdown (breakaway oxidation) and causing rapid oxidation and substrate degradation [14]. In contrast, an Al2O3 film exhibited superior thermodynamic stability and lower growth rates and could maintain effective protection even at above 1000 °C [15,16]. Therefore, introducing Al becomes an effective strategy to improve the high-temperature oxidation resistance of cladded coatings. Ma et al. [17] studied the effect of different Al contents on the oxidation performance and mechanisms of Cr-Al coatings and pointed out that the solid-solution strengthening of Al in Cr improves oxidation resistance; the coating containing 6.6 at.% Al had the best oxidation resistance due to the formation of a Cr2O3 + Al2O3 composite oxide scale that suppresses oxide growth and protects the substrate. During rapid solidification in cladding, Al can also readily react with Cr to form thermally stable intermetallics such as Cr2Al and Cr5Al8, further enhancing structural stability and oxidation/wear resistance of the coating. Based on the Cr-Al synergistic oxidation mechanism, the rapid formation of Cr2O3 can provide a nucleation substrate for the epitaxial growth of α-Al2O3, accelerating its densification and ultimately forming a stable and dense composite protective scale at high temperatures [18].

Based on the above analysis, we employed Cr3C2, Cr, and Al powders as the feedstock system for laser cladding to prepare a Cr-Al-C composite coating on H13 steel. It is expected that the coating’s wear resistance and oxidation resistance will be concurrently improved owing to dispersion-strengthening effect of Cr3C2, the high-temperature oxidation protection and metallurgical bonding improvement provided by Cr, and the formation of highly stable Al2O3/intermetallic compounds induced by the introduction of Al, thereby significantly improving the service performance of the piercing plugs under severe thermo-mechanical conditions. The main contribution is to clarify a structure-property relationship, showing that an in situ B2-ordered Fe(Al, Cr) matrix coupled with dispersed carbides provides an integrated microstructural basis for coupled oxidation-wear resistance under severe thermo-mechanical conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composite Powder

To prepare fine spherical agglomerates (microspheres) with good flowability, Cr3C2/Al/Cr microspheres were synthesized using a spray-drying granulation method [19]. First, raw powders of Cr3C2, Al, and Cr were prepared in a molar ratio of 0.9:2.1:1. The Cr3C2:Al:Cr molar ratio (0.9:2.1:1) was chosen to approximate Cr-Al-C stoichiometry (close to Cr2AlC), with a slight Al excess to compensate for Al loss during processing/cladding and to ensure sufficient Al for forming a protective Al2O3-containing scale at high temperature. Cr3C2 also acts as the carbon source and promotes Cr-rich carbide strengthening. The mixed powders were subjected to a planetary high-energy ball milling for 24 h at 240 r/min using a ball-to-powder ratio of 5:1 using 304 stainless steel balls as the milling media, to get a homogeneous and refined powder mixture. Tetramethylammonium hydroxide (C4H13NO) was used as a dispersant, and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was employed as a binder. The milled powders were mixed with deionized water at a mass ratio of 6:4, with 0.3% dispersant and 3% binder added, and mechanically stirred for 240 min to form a uniform and stable slurry. Subsequently, the slurry was spray-dried using a centrifugal spray granulation tower (The TSD series spray dryer manufactured by Wuxi Kaiyide Drying Equipment Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China) with an inlet temperature of 200 °C, outlet temperature of 120 °C, peristaltic pump speed of 13 rpm (corresponding to a feed rate of 50 mL/min), and atomizer frequency of 240 Hz, ultimately yielding Cr3C2/Al/Cr microspheres. After spray drying, the microspheres underwent binder removal in a vacuum-sealed furnace. Under vacuum, the temperature was raised to 300 °C at 10 °C/min, held for 1 h, and then furnace-cooled to room temperature, yielding dense and impurity-free Cr3C2/Al/Cr microspheres. The spray-drying parameters were determined based on preliminary trials and literature guidance to obtain spherical agglomerates with stable slurry atomization, rapid solvent removal, and sufficient granule densification, thereby improving powder handling and feeding stability during laser cladding. The substrate surface was polished with 200-mesh sandpaper to remove oil and oxide layers, followed by ultrasonic cleaning in anhydrous ethanol for 10 min and drying in an oven for later use.

2.2. Coating Preparation

H13 steel was selected as the substrate. The substrate dimensions were 50 mm × 50 mm × 5 mm. A composite coating was fabricated using a BC3000-60 laser cladding system (Nanjing Zhongke Yuchen Laser Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). After multiple preliminary experiments, the optimal processing parameters were identified as a laser power of 2000 W, a laser beam diameter of Φ 3 mm, a powder feed rate of 11 g/min, a scanning speed of 500 mm/min, a defocus distance of 40 mm, an overlapping rate 50%, with Ar as the protecting gas. A dense, crack-free coating with a thickness of approximately 2 mm was successfully produced.

2.3. Performance Testing and Characterizations

The phase constituents of the coatings were characterized by X-ray diffraction (Rigaku Ultima IV, Rigaku Corporation, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan), employing Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å), at a scanning rate of 10°/min, and a 2θ range from 5° to 90°. The cross-section of the coatings was etched with a mixed acid solution of HCl and HF (1:1) for 1 min to reveal the microstructure. The coating microstructure and elemental distribution were examined by a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-7001F + INCAX-MAX, EOL Ltd., Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The microhardness of the samples was determined using a Vickers hardness tester (HX-1000 TM/LCD, Shanghai Taiming Optical Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) under a load of 5 N and a dwell time of 15 s. Five indentations were measured every 0.1 mm along the depth from the surface to the substrate. All measurements were repeated under identical conditions to ensure the reliability of the results.

Before the tribological tests, all sample surfaces were progressively polished to achieve a mirror finish. The optimal tribological test parameters were determined by simulating the service conditions of a piercing plug under high temperature and high pressure (Table 1). Tribological tests were conducted using a GF-1200 high-temperature reciprocating tribological tester (Lanzhou Zhongke Kaihua Technology Co., Ltd., Lanzhou, China), with 5 mm-diameter DD5 high-temperature, nickel-based alloy balls as the friction pair material. The tribological test conditions were adopted with a stroke of 5 mm, under a load of 20 N, for 30 min, at room temperature and 1000 °C. The DD5 alloy possesses excellent high-temperature strength and microstructural stability and is a typical material for aero-engine turbine blades, effectively simulating severe high-temperature friction conditions. Tribological tests were conducted using a ball-on-disk configuration with reciprocating motion. The variation in the coefficient of friction over time was recorded in real time during the experiments. Two-dimensional profiles and three-dimensional morphology of wear scars were characterized using a 2D profilometer (Alpha-Step D-300, KLA Corporation, Milpitas, CA, USA) and a 3D surface profiler (VHX-6000, Keyence, Keyence Corporation, Osaka, Japan), and wear volumes were calculated via software analysis. The microstructure and elemental composition of the worn regions were characterized with SEM and EDS. The wear rate, W (mm3/N·m), was calculated according to Equation (1) [20].

where V is the wear volume (mm3), F is the applied load (N), and L is the sliding distance (m). For the wear tests, each condition was conducted once due to experimental constraints; therefore, the reported wear rates and friction coefficients represent single-run values, and no error bars are presented.

Table 1.

Atomic percentages (at.%) of elements in the laser-cladded Cr-Al-C composite coating obtained from EDS analysis for the entire region and at points A to D.

To evaluate the high-temperature oxidation resistance of the Cr-Al-C composite coating, the H13 samples with sizes of 10 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm and the coated samples with sizes of 10 mm × 10 mm × 7 mm and with a coating thickness of approximately 2 mm were used. Oxidation tests were conducted in a muffle furnace (OTF-1200 X, Shenyang Kejing Automation Equipment Co., Ltd., Shenyang, China) at temperatures of 800 °C, 900 °C, and 1000 °C, with a heating rate of 10 °C/min and an oxidation duration of 10 h. To prevent additional mass changes in the crucibles during high-temperature treatment, alumina crucibles were pre-oxidized for 2 h at the corresponding oxidation temperatures. Subsequently, the specimens were placed into the pre-oxidized crucibles and weighed together using an analytical balance (with an accuracy of 0.1 mg) to record the initial mass m0. During oxidation, the exposure was interrupted every 1 h for mass measurement: the samples were removed from the furnace, allowed to cool to room temperature (within ~20 min), and then manually weighed to record the mass change (mn), after which they were returned to the furnace for continued exposure. Therefore, the procedure can be considered approximately cyclic oxidation, because periodic cooling to room temperature and reheating were introduced by the hourly weighing steps. The weight gain (Δw) was calculated by (mn − m0)/Asurface area, and oxidation kinetic curves were plotted to analyze the mass evolution over time [21]. After the oxidation tests, the oxides on the coating surface were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Phase Analysis and Microstructure of the Coating

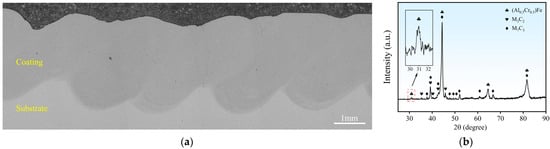

The microstructure and phase composition of the Cr-Al-C laser-clad coating were systematically characterized using XRD and SEM/EDS. Figure 1a shows the cross-sectional morphology of the laser-cladded Cr-Al-C composite coating. A dense and continuous coating layer with an average thickness of approximately 2.5 mm is formed on the substrate. The coating exhibits a relatively uniform thickness along the cladding direction without apparent macroscopic defects such as cracks, pores, or delamination. A clear and well-bonded coating/substrate interface was observed, indicating good metallurgical bonding achieved during the laser cladding process. Figure 1b presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the coating. The coating mainly consists of a B2-ordered (Al0.5Cr0.5)Fe phase and Cr-rich carbides (assigned to M3C2/M7C3-type carbides). Four diffraction peaks located at 31.023°, 44.390°, 64.669°, and 81.640° correspond to the characteristic planes of the B2 (CsCl-type) structure. The low-angle and weak peak at 31° is the (100) superlattice reflection of B2, while the other three peaks correspond to the (110), (200), and (211) planes. The lattice constants from the four diffraction peaks were highly consistent, with an average value of a = 0.28827 ± 0.00026 nm, indicating the cubic phase of Al0.5Cr0.5Fe.

Figure 1.

(a) Cross-sectional SEM of the laser-cladded Cr-Al-C composite coating on the H13 steel substrate. (b) XRD pattern of the laser-cladded Cr-Al-C composite coating.

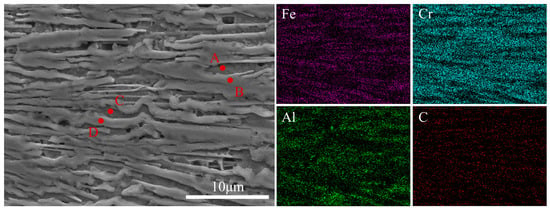

Figure 2 reveals that the etched coating exhibits a distinct layered stacking structure. Table 1 lists the elemental contents at different points in the SEM images. EDS point analysis indicates that the protruding regions (B and D points) were Cr-C enriched with low Fe and Al, having an approximate atomic ratio of Cr:Fe:Al ≈ 40:13:3. This region was primarily composed of Cr-rich carbides (assigned to M3C2/M7C3-type composite carbides) where M is mainly Cr with certain amounts of Fe and Al [22]. During laser cladding, Fe and Al atoms could partially dissolve into the Cr-rich carbide phases. Owing to the excellent chemical stability and high hardness of M3C2/M7C3-type carbides, they appeared as protrusions during etching, indicating greater resistance to corrosion. It is inferred that these carbides likely serve as the primary strengthening phase of the coatings, contributing to the enhancement of hardness and wear resistance.

Figure 2.

Local SEM image of the laser-cladded Cr-Al-C composite coating and the corresponding EDS point analyses taken from positions labeled A to D.

Compared to the M3C2/M7C3-type carbides in the protruding regions (B and D points), the recessed areas (A and C points) showed a more Fe-rich composition. SEM-EDS point analysis further revealed that the recessed regions were Fe-dominant, with Al and Cr present in nearly equal atomic ratios (Al:Cr:Fe ≈ 17:17:50), corresponding to the B2 (CsCl-type) (Al0.5Cr0.5)Fe phase. The lattice parameters and compositional range of this phase are highly consistent with reported Fe-Al-Cr B2 phases [23,24]. It should be noted that points A and C (as well as points B and D) exhibit close EDS compositions (Table 1), which is expected because the B2 matrix and Cr-rich carbides are finely intermixed. Due to the finite interaction volume of the electron beam, EDS spot measurements may include partial signal contributions from neighboring phases, especially near phase boundaries or within thin lamellae. Therefore, the phase attribution here is based on the combined evidence from etching contrast (protrusions vs. recesses), the compositional trends in Table 1 (Fe-rich vs. Cr-C enriched), and the XRD results, rather than the absolute values of a single EDS spot. Compared with the matrix, the addition of Al and Cr can enhance the matrix’s oxidation resistance and corrosion resistance. Moreover, studies reported that Al and Cr in Fe-based solid solutions can improve material toughness [25]. Previous studies demonstrated that B2 (Pm-3m, CsCl-type) ordering can significantly increase the yield strength and hardness of Fe-Al-Cr materials. This strengthening is mainly attributed to the ordered lattice, which constrains slip and increases the resistance to dislocation motion. In addition, the high antiphase boundary (APB) energy further hinders dislocation glide and contributes to the enhanced hardness [26,27,28]. Therefore, the (Al0.5Cr0.5)Fe phase in the coating may improve the performance of the coating.

3.2. Microhardness Analysis

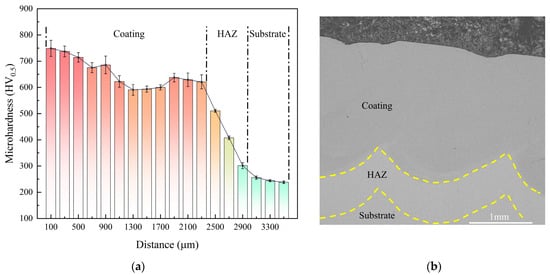

To verify the speculation on the proposed mechanism for the coatings’ hardness increase discussed in Section 3.1, microhardness tests were conducted in the direction perpendicular to the surface. Figure 3a shows the hardness distribution within the 0–3600 μm range. As shown in Figure 3a, the hardness exhibits a typical gradient decrease from the coating through the heat-affected zone (HAZ) to the substrate, which is consistent with the previously described microstructure and phase evolution. For clarity, the corresponding regions and approximate boundaries are indicated in the cross-sectional SEM image (Figure 3b), where the HAZ is defined based on the transition in the microhardness profile.

Figure 3.

(a) Microhardness profile of the laser-cladded Cr-Al-C coating. (b) Cross-sectional SEM image showing the coating, heat-affected zone (HAZ), and H13 substrate regions. The HAZ boundaries are indicated for guidance and are defined based on the microhardness profile.

Within the coating region, microhardness remained at 600–760 HV, significantly higher than the substrate, indicating a pronounced strengthening effect of the laser-clad Cr-Al-C coating. This enhancement mainly originates from three factors: first, the dispersed M3C2/M7C3-type hard carbides provide effective second-phase strengthening by impeding dislocation motion. Second, the formation of the B2 ordered phase in the Fe-Cr-Al system can pin dislocations, significantly enhancing the resistance to deformation [29]. Finally, the extremely high cooling rate during laser cladding promotes the formation of fine grains in the coating, further enhancing the material’s yield strength and hardness. The synergistic effect of these three strengthening mechanisms results in a coating hardness much higher than that of the H13 steel substrate.

The hardness change within the coating shows a gradual decrease with depth, primarily attributed to the cooling-rate gradient from the surface to the interior that drives microstructural and phase evolution [30]. As the depth increases to 1100–2300 μm, the microhardness decreases gradually from approximately 700 HV to 590–640 HV. This moderate reduction is mainly caused by grain coarsening due to the decreased cooling rate, and slight hardness fluctuations induced by compositional variations in the partially melted zone.

At the depth of 2500–2900 μm, reaching the heat-affected zone (HAZ) formed during laser surface engineering, a pronounced drop in microhardness was observed. Although no melting occurs in this region, it undergoes intense thermal cycling, which triggers tempering softening of the original structure and carbide coarsening. Consequently, its average hardness remains above that of the substrate. Unlike the coating, the HAZ contains no abundant fine hard carbides, and its microstructural evolution is governed mainly by the recovery and tempering responses of the substrate under rapid thermal cycling. As a result, its hardness remains significantly lower than that of the melt-cladded coating, producing a characteristic transition zone in the hardness profile [31].

When the depth exceeds 2900 μm, the microhardness stabilizes at 240–260 HV, consistent with the uncladded H13 steel substrate.

For context, reported microhardness values for laser-cladded coatings vary with alloy system and strengthening strategy. In an Fe-Ni-Al laser-cladded coating, the reported coating hardness spans about 361–489 HV (with a HAZ hardness of ~250 HV), depending on Al content and the tested region, which is lower than the present Cr-Al-C coating (600–760 HV) [32]. By contrast, a high-Al/high-Cr Fe-B-C laser-cladded coating exhibits a hardness of ~620 HV (substrate ~190 HV), where the strengthening was attributed to a hardened matrix together with boride/carbide precipitates, including Cr-rich M3C2/M7C3-type carbides [33]. Although test conditions differ across studies, these comparisons help contextualize the present hardness level and indicate its suitability for load-bearing service under severe thermo-mechanical conditions.

Overall, the microhardness profile exhibits a continuous and smooth gradient, which helps maintain surface wear resistance and indentation resistance, reduce interfacial residual stresses, avoid cracking or delamination caused by abrupt hard/soft transitions, and enhance the overall load-bearing capacity and service reliability.

3.3. Oxidation Properties

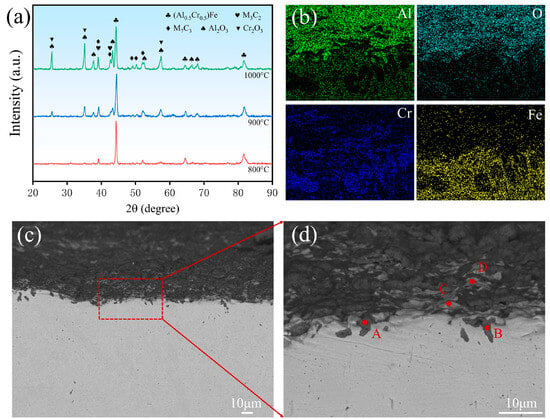

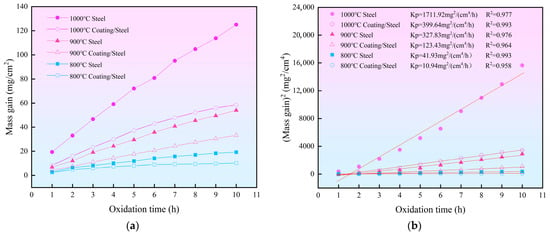

To systematically evaluate the high-temperature oxidation resistance of the Cr-Al-C laser-cladded coating, cyclic oxidation tests were carried out on the coated and the bare substrates at 800, 900, and 1000 °C for 10 h in air. The cyclic oxidation was performed with hourly interruption for mass measurement. The XRD patterns of the coating surface after oxidation at different temperatures are shown in Figure 4a. At 800 °C, no newly formed and distinguishable oxide diffraction peaks are detected, possibly due to oxidation being limited at this temperature. This result suggests that the coating maintains good oxidation stability under relatively moderate thermal exposure.

Figure 4.

(a) XRD patterns of the Cr-Al-C laser-cladded coating after oxidation at 800, 900, and 1000 °C for 10 h. (b) Cross-sectional EDS elemental maps of Al, O, Fe, and Cr for the coating oxidized at 1000 °C. (c) Cross-sectional SEM morphology of the coating after oxidation at 1000 °C, showing the overall oxide scale and coating structure. (d) Enlarged view of the selected region in (c), highlighting local microstructural features and the locations of EDS point analyses (A–D).

As the oxidation temperature was raised to 900 °C, characteristic diffraction peaks of Al2O3 and Cr2O3 appeared, implying that the coating surface enters an active oxidation stage accompanied by the formation of selective oxidation products dominated by Al and Cr. After oxidation at 1000 °C for 10 h, diffraction peak intensities of both Al2O3 and Cr2O3 were significantly enhanced, reflecting accelerated oxidation kinetics and an increased amount of oxide products at elevated temperatures. Meanwhile, the diffraction peaks corresponding to M3C2/M7C3-type carbides also became more pronounced, indicating that these Cr-rich carbide phases exhibit excellent thermochemical stability during high-temperature oxidation. Notably, no characteristic peaks of iron oxides (Fe2O3 or Fe3O4) were detected even at 1000 °C, demonstrating that the coating effectively suppresses the outward diffusion of Fe during oxidation [34].

Cross-sectional SEM images of the coating oxidized at 1000 °C are illustrated in Figure 4b–d. In addition, EDS point analyses were conducted at the characteristic regions labeled A–D (marked in Figure 4d), and the corresponding results are summarized in Table 2. Some white bright-contrast regions (C and D points) beneath the oxide scale are enriched in Cr and C, with Cr content of approximately 35 at.% and C content of about 54 at.%, while the oxygen content remains as low as 5 at.%. Combined with the XRD results, these phases are attributed to Cr-rich M3C2/M7C3-type carbides. Even after oxidation at 1000 °C for 10 h, these carbide phases remain structurally intact without evident oxidation, exhibiting excellent high-temperature oxidation stability.

Table 2.

EDS point analysis results (at.%) of the characteristic regions (A–D) marked in Figure 4 for the Cr-Al-C laser-cladded coating after oxidation.

Figure 5a shows the mass gain per unit area as a function of oxidation time for the coated and the bare H13 samples at different temperatures, and Figure 5b presents the corresponding parabolic fitting of the oxidation kinetics data. At the same temperature, the coated samples exhibit much lower mass gain rates than the bare substrate, indicating a significantly reduced oxidation rate. It is noted that the oxidation exposure was interrupted by hourly weighing, thereby introducing repeated cooling/heating between cycles. During the cooling steps, severe oxide-scale spallation was observed on the bare H13 substrate, whereas only slight spallation occurred on the coated samples, indicating improved scale adhesion on the coating. The oxidation kinetics (Equation (2)) was further analyzed using the parabolic rate law describing diffusion-controlled oxidation processes [35]:

where Δm/A represents the mass change per unit area (mg/cm2), Kp is the oxidation rate constant (mg2/(cm4/h)), t is the oxidation time (h), and C is an integration constant (intercept) reflecting the initial oxide condition and early transient oxidation before the steady parabolic regime. The fitting results show that the coefficients of determination (R2) for all six datasets exceed 0.95, indicating excellent agreement between the experimental data and the parabolic kinetic model. This confirms that the oxidation processes of both the coated and the bare substrate at all tested temperatures are governed by diffusion-controlled mechanisms.

Figure 5.

(a) The oxidation curve shows the weight gain of the coating over time. (b) Curve fitting of the oxidation kinetics data for the coating.

From a cyclic-oxidation perspective, repeated cooling/heating can generate additional thermal stresses (due to thermal-expansion mismatch and oxide growth stresses), which may promote microcracking or local spallation of the oxide scale and thereby compromise its integrity and protectiveness.

The parabolic rate constants (Kp) obtained from kinetic fitting further quantify the protective effect of the coating. As the oxidation temperature increases from 800 to 1000 °C, the Kp values of both the coated and the bare H13 samples increase markedly, reflecting the thermally activated nature of the oxidation process [35]. Nevertheless, the Kp values of the coated samples remain substantially lower than those of the bare H13 samples at all temperatures. Specifically, at 800 °C, the Kp value of the bare substrate is 41.93 mg2/(cm4/h), whereas that of the coated samples is significantly reduced to 10.94 mg2/(cm4/h), indicating an effective suppression of oxidation at the low-temperature stage. When the temperature increases to 900 °C, the Kp value of the coated samples remains markedly lower than that of the bare H13 samples. Under the severe oxidation condition of 1000 °C, the oxidation rate constant of the bare H13 samples increases sharply to 1711.92 mg2/(cm4/h), while that of the coated samples is only 399.64 mg2/(cm4/h), approximately one quarter of the bare substrate. This quantitative comparison clearly demonstrates the superior high-temperature oxidation resistance and pronounced inhibitory effect of the Cr-Al-C laser-cladded coating.

The improved oxidation resistance is primarily attributed to the formation of a dense, adherent Al2O3/Cr2O3 composite protective scale on the coating surface. Previous studies have demonstrated that the preferential formation of Cr2O3 at the early oxidation stage can act as a structural template for the epitaxial growth of α-Al2O3, facilitating the rapid development of a continuous and highly protective oxide layer [36]. Such a scale effectively retards inward oxygen diffusion and outward Fe migration. Moreover, this composite scale enhances scale integrity and adhesion during cyclic oxidation, thereby helping maintain sustained protection under repeated cooling/heating. Meanwhile, the thermally stable M3C2/M7C3-type carbide phases retained at high temperatures may further act as diffusion barriers, synergistically slowing down the oxidation process and thereby endowing the Cr-Al-C laser-cladded coating with outstanding high-temperature oxidation resistance.

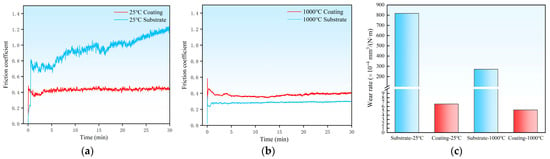

3.4. Tribological Properties

Wear resistance is generally strongly correlated with the material’s hardness [20]. Higher hardness can effectively resist abrasive indentation and plowing, thereby reducing wear volume and significantly influencing the interfacial coefficient of friction and the dominant wear mechanisms. To evaluate the service potential of the coating under practical high-temperature conditions, tribological tests were conducted on the H13 steel substrate and the laser-cladded Cr-Al-C coating at room temperature (25 °C) and high temperature (1000 °C), using a DD5 Ni-based alloy ball as the counter-body. Figure 6 presents the evolution of the coefficient of friction for the substrate and coating at different temperatures. At room temperature, the substrate’s coefficient of friction continuously increases after approximately 5 min of testing, reaching an average value as high as 0.929, indicating severe adhesion and plastic deformation (Figure 6a). In contrast, the coating shows minimal fluctuation in its friction coefficient throughout the test, with an average value of approximately 0.431. When the temperature reaches 1000 °C (Figure 6b), the substrate’s friction coefficient markedly decreases to 0.284, mainly due to the formation of an iron oxide (Fe3O4) on H13 steel, which acts as a solid lubricant and forms a low-shear-strength transfer film at the friction interface. In contrast, the Cr-Al-C coating forms a denser and more stable Al2O3-Cr2O3 composite oxide scale at high temperature, whose limited lubricity prevents further reduction in the friction coefficient. The coating exhibits an average friction coefficient of 0.378 at 1000 °C, which is slightly higher than that of the substrate but still indicates excellent high-temperature frictional stability.

Figure 6.

Evolution of the friction coefficient of the coating and the H13 steel substrate at different temperatures: (a) 25 °C and (b) 1000 °C. (c) Wear rates of the H13 steel substrate and the coating after sliding tests at 25 °C and 1000 °C.

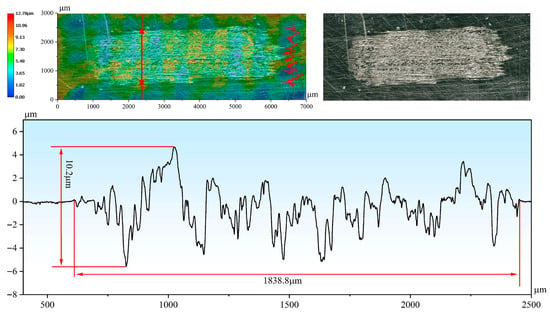

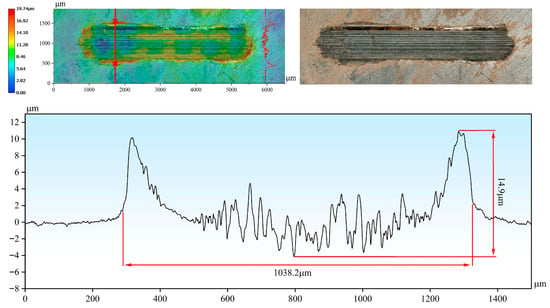

By analyzing the three-dimensional wear morphologies and the corresponding two-dimensional profile curves of the wear scars (Figure 7 and Figure 8), the wear severity of different samples can be more intuitively compared in terms of wear scar width and depth. At room temperature, the wear scar width and maximum wear depth of the H13 steel substrate reached 3349.1 μm and 180.1 μm, respectively. In contrast, the Cr-Al-C coating exhibited a wear scar width and depth of 1838.8 μm and 5.5 μm, respectively, with the wear depth being approximately 3.0% of that of the substrate. At 1000 °C, the wear scar width and depth of the substrate were 2532.1 μm and 85.8 μm, respectively (Figure 8). In comparison, the corresponding values for the Cr-Al-C composite coating were only 1038.2 μm and 4.1 μm, with the wear depth being approximately 4.8% of that of the substrate. Based on the pronounced differences in wear scar geometrical parameters, the wear rates of different samples at different temperatures were further quantitatively calculated and comparatively analyzed. As shown in Figure 6c, the wear rate of the coating is significantly lower than that of the substrate at both room temperature and 1000 °C. At room temperature, the substrate showed a wear rate of 8.175 × 10−4 mm3/(N·m), while the coating demonstrated a wear rate of 6.563 × 10−6 mm3/(N·m), about two orders of magnitude lower than that of the substrate. When the temperature was increased to 1000 °C, the substrate’s wear rate decreased to 2.706 × 10−4 mm3/(N·m), whereas the coating maintained a low wear rate of 5.202 × 10−6 mm3/(N·m), corresponding to only 1.9% of the substrate. This demonstrates that the coating exhibits superior wear resistance compared with the substrate under both ambient and high-temperature conditions. Notably, the wear rate of the coating at 1000 °C is slightly lower than that at room temperature, further indicating that the Al2O3/Cr2O3 composite oxide film formed at high temperature provides additional protection.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional morphology and two-dimensional cross-sectional profile of the wear scar on the coating after testing at 25 °C.

Figure 8.

Three-dimensional morphology and two-dimensional cross-sectional profile of the wear scar on the coating after testing at 1000 °C.

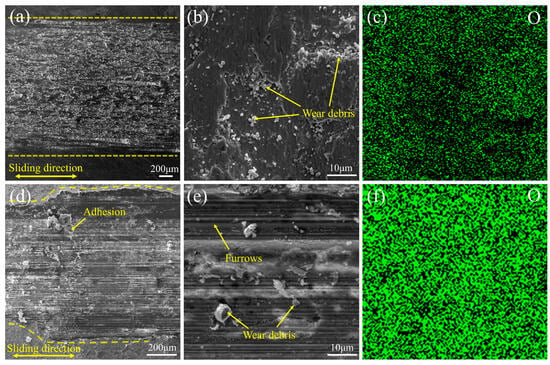

By combining the microscopic morphologies of the wear scars (Figure 9) with the frictional behavior, the wear mechanisms can be analyzed below. At room temperature, the high hardness of the coating effectively resists abrasive indentation and plowing. Consequently, no pronounced grooves appear on the wear track (Figure 9a,b), and only a small amount of debris is observed. Trace O and Ni detected by EDS (Figure 9c) indicate the occurrence of slight oxidation and material transfer. Therefore, the dominant wear mechanism of the coating at room temperature is adhesive wear, accompanied by slight oxidative wear. In contrast, the H13 steel substrate with lower hardness underwent plastic deformation during sliding, thereby increasing the real contact area. This facilitates the occurrence of adhesive wear and material transfer, consequently resulting in an increased friction coefficient. Moreover, H13 steel is unable to form a continuous protective oxide film at room temperature, which further aggravates frictional wear.

Figure 9.

SEM images of worn surface morphologies of the Cr-Al-C coating after sliding tests at different temperatures: (a,b) at 25 °C under low and high magnifications, respectively; (d,e) at 1000 °C under low and high magnifications, respectively. Corresponding EDS elemental maps for oxygen are shown in (c,f) at 25 °C and 1000 °C, respectively.

At 1000 °C, although the substrate exhibits a lower friction coefficient due to the presence of a lubricious Fe3O4 film, its wear rate remains much higher than that of the coating. This discrepancy primarily originates from the distinct characteristics of the oxide films formed on the two materials. The coating develops a continuous, dense, and well-adherent Cr2O3/Al2O3 composite oxide scale, characterized by extremely low oxygen diffusivity and excellent resistance to spallation, enabling effective substrate isolation and mechanical load bearing.

EDS (Figure 9f) reveals a pronounced increase in O content within the high-temperature wear track, confirming the stability of the oxide scale. As shown in Figure 9c,d, a complete oxide layer, localized plowing traces, oxide debris, and adhered particles can be observed, indicating that the coating undergoes oxidation-dominated wear at high temperatures, accompanied by abrasive wear and adhesive wear. In contrast, the Fe3O4 film formed on the H13 substrate is porous and prone to spallation; its repeated formation-and-fracture process (cyclic oxidation) markedly accelerates material loss, resulting in a much higher wear rate than the coating.

In summary, the superior wear resistance of the laser-clad Cr-Al-C coating from room temperature to 1000 °C arises from the synergistic enhancement of its dense protective oxide film, high-temperature microstructural stability, and intrinsically high hardness. These attributes endow the coating with strong potential for long-term service under high-temperature tribological conditions.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the phase composition, high-temperature oxidation behavior (800–1000 °C), and tribological performance at room temperature and 1000 °C of a Cr-Al-C composite coating fabricated on H13 steel by laser cladding. Beyond conventional designs that improve oxidation protection or wear resistance in isolation, the key insight of this work is that the in situ B2-Fe(Al, Cr) + carbide phase architecture enables coupled oxidation-wear resistance, as supported by the oxidation kinetics from 800–1000 °C and the wear mechanisms at room temperature and 1000 °C. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

- A dense Cr-Al-C coating produced by laser cladding metallurgically bonded well to the H13 steel substrate. The coating was composed of in situ formed B2-ordered (Al0.5Cr0.5)Fe phase together with dispersed M3C2/M7C3-type carbides. The combination of B2 ordered-phase strengthening, carbide dispersion strengthening, and grain refinement induced by rapid laser solidification is the dominant strengthening mechanism, resulting in a significant enhancement of microhardness, approximately three times that of the substrate.

- The Cr-Al-C laser-cladded coating exhibited markedly enhanced oxidation resistance compared with the bare substrate in the temperature range 800–1000 °C. The synergistic oxidation of Cr and Al promotes the rapid formation of a continuous, dense, and adherent Al2O3/Cr2O3 protective scale, which effectively suppresses inward oxygen diffusion and outward Fe migration, even at 1000 °C. Additionally, the thermally stable M3C2/M7C3-type carbide phases retained beneath the oxide scale act as auxiliary diffusion barriers.

- At both room temperature and 1000 °C, the Cr-Al-C laser-cladded coating exhibits significantly lower wear rates than the H13 steel substrate. At room temperature, the wear rate of the coating was 6.563 × 10−6 mm3/(N·m), about two orders of magnitude lower than 8.175 × 10−4 mm3/(N·m) for the substrate. The wear mechanism at room temperature is dominated by adhesive wear, accompanied by mild oxidative wear. At 1000 °C, the wear rate of the coating remains extremely low, accounting for only 1.9% of that of the substrate, indicating excellent wear stability under high-temperature conditions. The dominant wear mechanism shifts to oxidative wear, associated with the formation of a protective oxide layer on the worn surface, while abrasive and adhesive wear play secondary roles.

- This work demonstrates that the Cr-Al-C composite coating provides reliable surface protection for metallic components under extreme conditions, highlighting its potential for practical industrial applications.

In this study, there is a lack of systematic research on the influences of coating thickness and temperature on the wear resistance of the Cr-Al-C coating. Future work will investigate the aforementioned influencing factors and evaluate long-term wear resistance performance.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, S.Z., Y.Z., S.L., X.Z., G.B., F.C., D.L.; investigation, S.Z. and Y.Z., F.C.; data curation, S.Z. and X.Z., Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.L.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, S.L.; funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 52275171.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Guoping Bei was employed by the company China Porcelain Fuchi (Suzhou) High Tech Nano Materials Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yamane, A.; Shitamoto, H.; Yamane, K. Development of Numerical Analysis on Seamless Tube and Pipe Process. Nippon Steel Sumitomo Met. Tech. Rep. 2015, 107, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Chen, Z.; Yan, Y.; Zhuo, Y.; Wang, C.; Jia, Q. Enhanced High−Temperature Wear Performance of H13 Steel through TiC Incorporation by Laser Metal Deposition. Materials 2022, 16, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Du, B.; Sun, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. The Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Cladded CoCrFeNiAl/WC Coatings on H13 Steel. Coatings 2025, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficak, G.; Łukaszek-Sołek, A.; Hawryluk, M. Durability of Forging Tools Used in the Hot Closed Die Forging Process–A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Xie, D.; Liu, Y.; Lv, F.; Zhou, K.; Jiao, C.; Gao, X.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Zu, H.; et al. Effect of WC on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Clad AlCoCrFeNi2.1 Eutectic High-Entropy Alloy Composite Coatings. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 976, 173219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Xue, P.; Lan, Q.; Meng, G.; Ren, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xu, P.; Liu, Z. Recent Research and Development Status of Laser Cladding: A Review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 138, 106915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbale, A.M.; Kumar, M.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Ahamad, T.; Kalam, M.A.; Mubarak, N.M.; Alfantazi, A.; Khalid, M. A Comparative Study on Characteristics of Composite (Cr3C2-NiCr) Clad Developed through Diode Laser and Microwave Energy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Shan, J.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Gong, K.; Li, C. Effect of Cr3C2 Content on the Microstructure and Wear Resistance of Fe3Al/Cr3C2 Composites. Coatings 2022, 12, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, B.; Chen, L.; Xu, J.; Zhu, Y. Effect of Laser Cladding Stellite 6-Cr3C2-WS2 Self-Lubricating Composite Coating on Wear Resistance and Microstructure of H13. Metals 2020, 10, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-Y.; Wang, C.-M.; Ji, J.-X.; Feng, X.-L.; Cui, H.-Z.; Song, Q.; Zhang, C.-Z. Synthetic Effect of Cr and Mo Elements on Microstructure and Properties of Laser Cladding NiCrxMoy Alloy Coatings. Acta Metall. Sin. Engl. Lett. 2020, 33, 1331–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Wu, C.; Zhang, J.; Abdullah, A. Effects of V and Cr on Laser Cladded Fe-Based Coatings. Coatings 2018, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Guo, Y.; Lei, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Sun, H.; Wang, P. Effect of Chromium Addition on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Laser Cladding Ti-Al-SiC Composite Coatings. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 39481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jie, X.; Zhang, L.; Luo, S.; Zheng, Q. Improving the High-Temperature Oxidation Resistance of H13 Steel by Laser Cladding with a WC/Co-Cr Alloy Coating. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 2016, 63, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, T.; Karlsson, S.; Hooshyar, H.; Sattari, M.; Liske, J.; Svensson, J.-E.; Johansson, L.-G. Oxidation After Breakdown of the Chromium-Rich Scale on Stainless Steels at High Temperature: Internal Oxidation. Oxid. Met. 2016, 85, 509–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybicki, G.C.; Smialek, J.L. Effect of the θ-α-Al2O3 Transformation on the Oxidation Behavior of β-NiAl + Zr. Oxid. Met. 1989, 31, 275–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pint, B.A. Experimental Observations in Support of the Dynamic-Segregation Theory to Explain the Reactive-Element Effect. Oxid. Met. 1996, 45, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Meng, C.; Wang, H.; He, X. Effect of Al Content on the High-Temperature Oxidation Resistance and Structure of CrAl Coatings. Coatings 2021, 11, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, J.; Duan, C.; Feng, X.; Shen, Y. Investigation of Cr-Al Composite Coatings Fabricated on Pure Ti Substrate via Mechanical Alloying Method: Effects of Cr-Al Ratio and Milling Time on Coating, and Oxidation Behavior of Coating. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 660, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Fan, S.; Bei, G. Preparation and Characterization of Cr2AlC Microspheres Prepared by Spray-Drying Granulation. Powder Technol. 2024, 437, 119521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archard, J.F. Contact and Rubbing of Flat Surfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 1953, 24, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smialek, J.; Garg, A.; Gabb, T.; MacKay, R. Cyclic Oxidation of High Mo, Reduced Density Superalloys. Metals 2015, 5, 2165–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, J.; Kiviö, J.; Balusson, C.; Raami, L.; Vihinen, J.; Peura, P. High-Speed Laser Cladding of Chromium Carbide Reinforced Ni-Based Coatings. Weld. World 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friák, M.; Golian, M.; Holec, D.; Koutná, N.; Šob, M. An Ab Initio Study of Magnetism in Disordered Fe-Al Alloys with Thermal Antiphase Boundaries. Nanomaterials 2019, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Jiang, S.; Huang, T.; Qin, M.; Hu, T.; Luo, J. Single-Phase High-Entropy Intermetallic Compounds (HEICs): Bridging High-Entropy Alloys and Ceramics. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yao, Z.J.; Zhang, P.Z.; Luo, X.X.; Zhang, Z.L.; Han, P.D. Elastic Constants and Properties of B2-Type FeAl and Fe-Cr-Al Alloys from First-Principles Calculations. In Proceedings of the 2nd Annual International Conference on Advanced Material Engineering (AME 2016), Wuhan, China, 15–17 April 2016; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerbacher, M. Dislocations and Deformation Microstructure in a B2-Ordered Al28Co20Cr11Fe15Ni26 High-Entropy Alloy. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Królicka, A.; Caballero, F.G. B2-Strengthened Fe-Mn-Al-C-Ni Steels as a Promising Environmentally Friendly Structural Material: Review and Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korir, R.C.; Huang, Y.-T.; Cheng, W.-C. Martensitic Transformation Induced by B2 Phase Precipitation in an Fe-20 Ni-4.5 Al-1.0 C Alloy Steel Following Solution Treatment and Subsequent Isothermal Holding. Metals 2025, 15, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanzade, M.; Barnoush, A.; Motz, C. A Review on the Properties of Iron Aluminide Intermetallics. Crystals 2016, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta Majumdar, J.; Manna, I. Laser Material Processing. Int. Mater. Rev. 2011, 56, 341–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X. Martensite Transformation Characteristics in the Heat Affected Zone of Laser Cladding on Rail. Mater. Lett. 2024, 367, 136615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Qi, C. Study on the Microstructure and Properties of a Laser Cladding Fe-Ni-Al Coating Based on the Invar Effect. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ju, J.; Chang, W.; Yang, C.; Wang, J. Investigation on the Microstructure and Wear Behavior of Laser-Cladded High Aluminum and Chromium Fe-B-C Coating. Materials 2020, 13, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Bei, G. Recent Progress in Preparation, Microstructure and Properties of Cr2AlC MAX Phase Coatings. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 117555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, N.; Meier, G.H.; Pettit, F.S. Introduction to the High Temperature Oxidation of Metals, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-521-48042-0. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Guo, E.; Zhong, F.; Fu, B.; Cai, G.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, C.; Ren, F. A Novel Method for Preparing α-Al2O3 (Cr2O3)/Fe-Al Composite Coating with High Hydrogen Isotopes Permeation Resistance. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 20367–20375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.