Abstract

Electrochemical deposition of gold from a sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte was studied on GaAs–TiAu substrates using polarization curve measurements, gold layer morphology analysis (AFM), and current efficiency determination in the temperature range of 20–65 °C. It was found that increasing the temperature to 50–65 °C makes it possible to raise the gold deposition current density from 2 to 7 mA/cm2 while maintaining a current efficiency close to 100% and obtaining compact coatings with a surface root mean square roughness Sq of 6–8 nm. The activation energy of the process is 20–25 kJ/mol. It was shown that electrochemical conditioning of the electrolyte prevents sulfur precipitation, whereas the introduction of excess sulfite ions dissolves the sediment but leads to poorer coating quality. Thus, the feasibility of electrolyte regeneration has been demonstrated, and optimal gold deposition regimes have been determined: 7 mA/cm2 at 50 °C and 10 mA/cm2 at 65 °C.

1. Introduction

Electrochemical deposition of gold on TiAu is widely used in microelectronics, microsystems, and optoelectronics to create contact, barrier, and reflecting layers and conductive traces and pads for soldering or thermocompression bonding—titanium provides strong adhesion to semiconductor and dielectric surfaces, while the top gold layer ensures high electrical conductivity, chemical inertness, and compatibility with wire bonding and soldering processes [1,2,3,4,5,6]. It should be noted that the interest in the electrochemical deposition of gold is not limited exclusively to plating onto pre-deposited gold layers. The literature reports demonstrate the feasibility of Au electrodeposition onto a wide range of other conductive substrates, including semiconductor structures [7,8,9] and carbonaceous materials (glassy carbon, graphite, carbon micro- and ultramicroelectrodes [10,11,12,13]).

Thin gold films are used as catalysts in energy applications [14,15,16] and as sensors [16,17,18,19,20]. Conventional gold plating electrolytes are based on cyanide complexes that provide high-quality precipitates and fine control over the process; however, their high toxicity incentivizes the search for safe alternatives [21]. Among cyanide-free systems, the most attractive are electrolytes based on sulfite and thiosulfate compounds of gold providing lower toxicity, fair solubility of Au(I) complexes, and compatibility with photoresists [22,23].

Thiosulfate gold plating electrolytes exhibit limited working or storage stability. The instability is due to disproportionation of thiosulfate yielding colloid sulfur and sulfite ions (S2O32− → S0 + SO32−) and protonation with subsequent degradation of the Au(S2O3)23− complex [24]. These processes lead to electrolyte turbidity, lower current yield, and deterioration of the precipitate morphology. To increase the stability of thiosulfate systems, it was suggested to combine thiosulfate ions and sulfite ions in the solution, which allowed for obtaining more stable mixed complexes of gold, such as Au(S2O3)(SO3)25− [1,25,26].

The stability of this complex is comparable to that of the cyanide complex and distinguishes it among other sulfite-thiosulfate complexes of gold (Table 1). The stability constants summarized in Table 1 were not determined in the present study but were compiled from the literature. Depending on the system, they were obtained using potentiometric titration and equilibrium modeling [27], electrochemical speciation analysis and thermodynamic calculations [26,28,29], and differential UV spectroscopy, as well as quantum-chemical (DFT) calculations supporting the data [30]. Despite methodological differences, the reported values are in agreement.

Table 1.

Stability constants of (log β) of Au(I) complexes in cyanide and sulfite-thiosulfate systems.

The authors of [31] showed that the sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte is more stable as compared to individual solutions based on Na2S2O3 or Na2SO3. Gold precipitates as dense and uniform coatings at a temperature of 50–60 °C without signs of the precipitate formation in the electrolyte. Estrine et al. in [26] have confirmed the existence of stable mixed Au(I) complexes in similar systems and have shown that it is Au(S2O3)(SO3)25− complex that is electroactive during gold reduction on the platinum electrode. The calculated stability constant (log β ≈ 30.8) for this complex is appreciably higher than that for Au(S2O3)23− (log β ≈ 24–28.7), which explains an elevated stability of the electrolyte and possibility of its prolonged operation without sulfur sedimentation.

Increased stability of the gold plating sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte remains an urgent task and has been covered in a number of publications over the recent years. In work [32], Li K. et al. scrutinized the effects of pH and temperature on the stability and kinetics of gold reduction in thiosulfate solutions and established that increased temperature accelerated reduction, though, impaired the stability of the complex. Studies [28,33] have noted that the key factor determining the stability of sulfite-thiosulfate systems is the balance between S2O32− and SO32− ligands. This is because sulfite acts as a “regenerator” of thiosulfate, preventing the formation of colloidal sulfur, the sedimentation of which becomes particularly pronounced at lower pH [34]. However, practical methods for restoring solution stability, such as by adding sulfite ions or adjusting the pH, have not been studied in detail.

Recent publications on thiosulfate systems pointed out the possible regeneration of the solution by Na2SO3 [33]. However, there is no quantitative assessment data describing the influence of excess sulfite on the precipitation kinetics and morphology of gold coating.

Therefore, the goal of the present work is a complex study of the electrochemical deposition of gold from the sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte, including the analysis of temperature and current density effects on the morphology of the precipitates, determination of gold reduction activation energy, and the assessment of the influence of excess sulfite ions on the electrolyte stability and possibility of its regeneration after sedimentation of sulfur.

Despite the accumulated experimental data, significant gaps remain in the systematic investigation of the effects of temperature, current density, and kinetic parameters. Furthermore, quantitative data on electrolyte regeneration following sulfur deposition are limited.

Consequently, the objective of this work is to systematically examine the influence of temperature and current density on the electrodeposition of gold from a sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte (pH 5.7) onto GaAs–TiAu substrates. Particular emphasis was placed on establishing the dependence of the activation energy for gold reduction on the electrode potential. This relationship has not been comprehensively analyzed for sulfite-thiosulfate systems. This study also demonstrates the impact of excess sulfite ions on the dissolution of precipitated sulfur, changes in pH, and the morphology of gold deposits. These findings allow for an assessment of the feasibility of electrolyte regeneration and the extension of its service life.

The results contribute to modern views on the chemical and electrochemical stability of sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating systems and can be used when developing cyanide-free gold plating technologies in microelectronics.

2. Materials and Methods

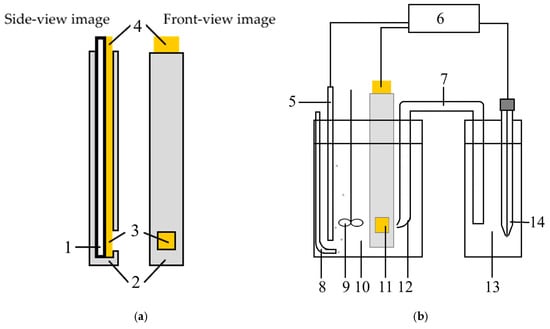

In the experiments, gold was electrochemically deposited on n-type GaAs specimens with sputtered TiAu layers having a thickness of 0.05 and 0.2 μm. To prepare the specimens, GaAs plates were soaked in dimethylformamide at 150 °C for 10 min. Then, TiAu was deposited by electron-beam sputtering. Immediately before recording the polarization curves and electrodeposition, GaAs-TiAu specimens were treated in dimethylformamide (heated until bubbling, cooled down, washed in deionized water having a resistance of 18 MOhms) and coated with chemically resistant varnish KhV-784 (a protective coating based on chlorinated polyvinyl chloride (CPVC) resins with organic solvents, providing strong adhesion and resistance to acids). On the one end of the specimen, there was an uncoated space for a current lead connection. On the other end to be put into the electrolyte, there was an uncoated window for which the area was measured by transparent scale paper. Figure 1a shows the schematic of the working electrode.

Figure 1.

Specimen and electrochemical cell for polarization curve recording: (a) 1—GaAs semiconductor plate, 2—insulating varnish, 3—0.05/0.2-μm sputtered layer of TiAu, 4—current lead connection pad; (b) three-electrode cell scheme: 5—auxiliary electrode, 6—potentiostat-galvanostat, 7—electrochemical bridge, 8—nitrogen gas flow, 9—overhead stirrer, 10—gold plating electrolyte, 11—working electrode, 12—the Haber–Luggin capillary, 13—solution of potassium chloride, 14—silver chloride reference electrode.

Polarization studies were performed in the three-electrode electrochemical cell (Figure 1b). The auxiliary electrode was represented by a platinum plate (≥99.9% purity). The reference electrode was a saturated silver chloride electrode connected with the electrolyte through an electrochemical bridge filled with saturated solution of potassium chloride and combined with the Haber–Luggin capillary. The potential was measured versus a saturated silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) reference electrode and subsequently converted to the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE) scale. Before recording the polarization curves, the electrochemical cell was bubbled by nitrogen for 20 min. The polarization studies were conducted on a potentiostat-galvanostat P-40X (Elins, Chernogolovka, Russia). Polarization studies were performed using a P-40X potentiostat-galvanostat (Ellins, Russia). The curves were recorded in a potentiodynamic mode at 20, 35, 50, and 65 °C in the background electrolyte and in sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolytes. The electrolyte compositions are given in Table 2. The electrochemical cell was thermostated using an ELMI TW-2.02 water bath (ELMI, Riga, Latvia). To calculate the activation energy and determine the character of cathodic polarization during gold electroplating, the temperature kinetics method was used [35,36,37].

Table 2.

Compositions of sulfite-thiosulfate electrolytes for recording polarization curves and assessing the influence of sulfite ions on the electrolyte stability.

To assess the contact quality and current yield of gold layers electrochemically deposited from electrolyte 1, the specimens with sputtered metallic coating were weighted with fourth-order accuracy, coated by insulating chemically resistant XB-784 varnish, treated by sulfuric acid (H2SO4:H2O = 1:10) for 1 min, and washed in deionized water. Then, gold was deposited from the sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte. Then, the varnish was removed mechanically and by a solvent (1:1 mixture of toluene and acetone). The specimens were reweighed, and the current yield was calculated based on the mass change. The thickness of the coating was measured on a S-Neox confocal profilometer (Sensofar Metrology, Terrassa, Spain) relative to the marks in the center and along the specimen’s edges insulated by the varnish for the time of electrochemical deposition. The morphology of the specimens was assessed on a SCB8001VEGA atomic force microscope (NT-MTD Spectrum Instruments, Zelenograd, Russia). The root mean square roughness Sq was measured on a section with an area of 102 μm. Nanoindentation of the coatings was carried out with a NanoTest system (Micro Materials Ltd., Wrexham, Wrexham, UK) using a Berkovich indenter in the load-controlled mode. The loading and unloading times were set to be 20 s, with a 10 s dwell time at the maximum load and a 60 s dwell time at 90% unloading for thermal drift correction. At least 10 indentations were made at each load, separated by a spacing of 50 µm. The maximum applied load ranged from 2 to 10 mN. To ensure the measured properties were not influenced by the substrate, the maximum indentation depth was kept below 10% of the coating thickness for all tests. The hardness of the coatings were extracted from the load–displacement curves using the Oliver–Pharr method [38]. The measured values were averaged and rounded to the nearest whole number. The pH of each electrolyte was measured at room temperature with a calibrated HI 98108 pHep+ pocket pH tester (Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA). The obtained values are listed in Table 2.

The effect of annealing on the physical properties of the deposited gold layers was studied after annealing at 270 °C in nitrogen for 10 min in an SNOL 15/900 furnace (AB “UMEGA GROUP”, Utena, Lithuania).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Deposition Conditions on Current Yield and Properties of Deposited Gold Layers

For electrochemical processes, the dependence of current density on temperature at a constant potential is described by an equation similar in form to the Arrhenius equation [35]:

where A is the effective activation energy of the electrode process and R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol−1·K−1). Thus, there is a linear relationship between log i and 1/T, which holds true over a wide temperature range.

The activation energy of the electrochemical reaction was calculated from the slope of the straight line in the coordinates of log i vs. 1/T:

The activation energy of the electrochemical reaction was calculated from the slope of the straight line in the coordinates of log i vs. 1/T, at temperatures of 20, 35, 50, and 65 °C.

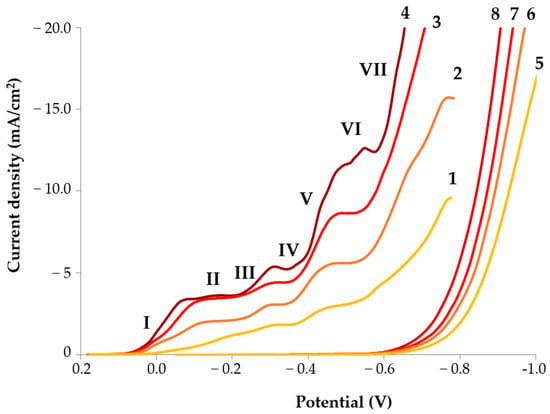

On the polarization curves plotted for the sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolyte, there is a trend of polarization decrease with increasing temperature (Figure 2). As can be seen from Figure 2, regardless of the temperature, all curves exhibit four characteristic waves.

Figure 2.

Polarization curves of gold deposition from the sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolyte (curves 1–4) and background electrolyte (curves 5–8) at different temperatures: 1, 5–20 °C; 2, 6–35 °C; 3, 7–50 °C; 4, 8–65 °C.

According to [33], the first wave (regions I and II) of the polarization curve corresponds to the reaction of gold reduction from the thiosulfate complex:

[Au(S2O3)2]3− + e− → Au + 2S2O32−

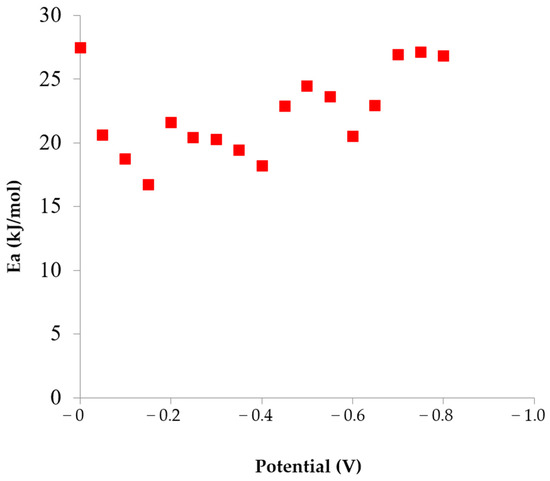

At a potential of 0 V, the calculated activation energy for this reaction is 27.4 kJ/mol (Figure 3), indicating a mixed diffusion–kinetic mechanism. In the potential range from −0.05 V to −0.15 V, diffusion control increases, and the activation energy for the reduction of the [Au(S2O3)2]3− complex decreases from 20.6 to 16.7 kJ/mol (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dependence of activation energy on the deposition potential in the sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolyte.

On the second wave of the polarization curve (sections III and IV), a discharge of the adsorbed intermediate reaction products occurred (reactions 2 and 3). Their decomposition intensified in the acidic medium near the electrode surface [26] as follows:

2[Au(S2O3)2]3− → Au2S2O3 ads + 3S2O32−

Au2S2O3 ads + 2e− → 2Au + S2O32−

The activation energy for this reaction is 19.4–20.4 kJ/mol and it proceeds under diffusion control.

On the third wave of the polarization curve (sections V and VI), the electrochemical reaction mechanism changes from diffusion-controlled to mixed, with an activation energy of 18.2–24.5 kJ/mol (Figure 3). There was an appreciable growth of the cathodic current density due to the reaction of gold reduction in the Au(S2O3)(SO3)25− sulfite-thiosulfate complex [26]:

[Au(S2O3)(SO3)2]5− + e− → Au + S2O32− + 2SO32−

On section VII of the polarization curve, starting from −0.55 V, reactions of sulfite ion reduction and hydrogen liberation took place, which lowered the current yield (Table 3):

2SO32− + 2e− + 2H2O → S2O42− + 4OH−

2H2O + 2e− → H2 + 2OH−

Table 3.

Current yield and deposition rate of gold depending on temperature and current density.

According to the calculations, the potential of hydrogen reduction from the electrolyte with pH of 5.7 amounted to −0.34 V.

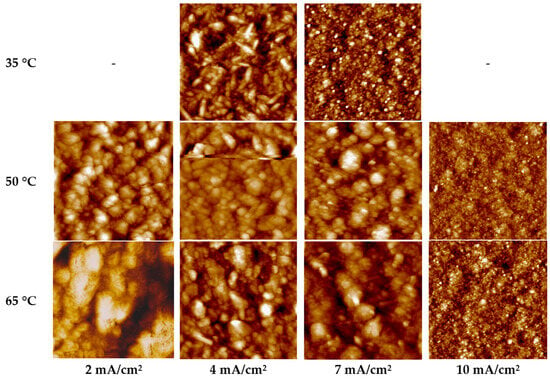

Gold electrodeposition from a sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte within the current density range of 2–10 mA/cm2 and the temperature range of 35–65 °C exhibits a pronounced dependence of the morphology, microstructure, surface roughness, and microhardness of the resulting coatings on the deposition potentials corresponding to different segments of the polarization curves.

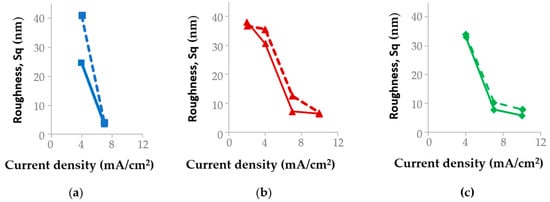

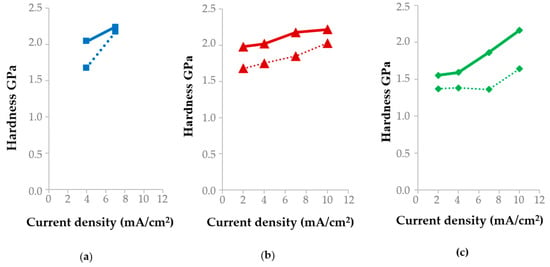

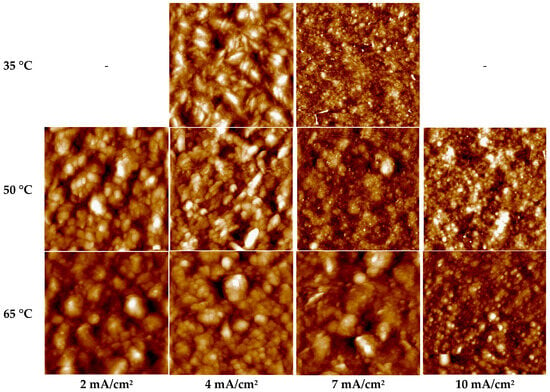

On segments I–II (the first wave), which are characterized by the reduction of the [Au(S2O3)2]3− complex (reaction (1)) and mixed diffusion–kinetic control, coatings with a coarse-grained structure are formed. At a current density of 2 mA/cm2 and temperatures of 50–65 °C, the deposits exhibit well-defined grain boundaries (Figure 4). This results in elevated surface roughness values (Sq 34–36 nm, Figure 5) and a moderate microhardness of 1.55–1.98 GPa (Figure 6) due to the weakened Hall–Petch strengthening effect. Under these conditions, the current efficiency remains close to 100% (Table 3).

Figure 4.

AFM image of gold layers deposited from the sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte at different temperatures and current densities (the section dimensions in the images was 3 × 3 μm). The sample deposited at 4 mA/cm2 and 50 °C exhibits linear distortions in its AFM topography, characteristic of a tip-slip scanning artifact.

Figure 5.

Roughness of the specimens deposited at (a) 35 °C, (b) 50 °C, and (c) 65 °C before (solid line) and after annealing (dashed line).

Figure 6.

Hardness of the specimens deposited at (a) 35 °C, (b) 50 °C, and (c) 65 °C before (solid line) and after annealing (dashed line).

The AFM images of the samples (Figure 4) deposited at potentials corresponding to segments III–IV (the second polarization wave) at 50 and 65 °C and a current density of 4 mA/cm2 reveal that the deposits are characterized by large, spherical grains and a surface roughness Sq of 30–34 nm. The atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of the gold layer deposited at 4 mA/cm2 and 50 °C (Figure 5) reveals a scanning artifact indicative of tip slippage, characterized by a horizontal streak and affecting less than 3% of the scan area. The mechanical properties of these deposits correspond to those of the first wave, while the current efficiency likewise remains close to 100%.

At 35 °C, the same current density of 4 mA/cm2 shifts the potential to more negative values (down to −0.4 V), corresponding to the onset of the third polarization wave. Under these conditions, gold layers with reduced surface roughness are formed (Sq = 25 nm, Figure 5a). The hardness is 2.04 GPa (Figure 5a), the grains exhibit an elongated morphology (Figure 4), and the deposited layers are characterized by a non-uniform thickness distribution. For a sample area of 2.5 cm2, the measured thickness of the gold deposits varies from 1.6 μm to 2.4 μm across different regions of the specimen.

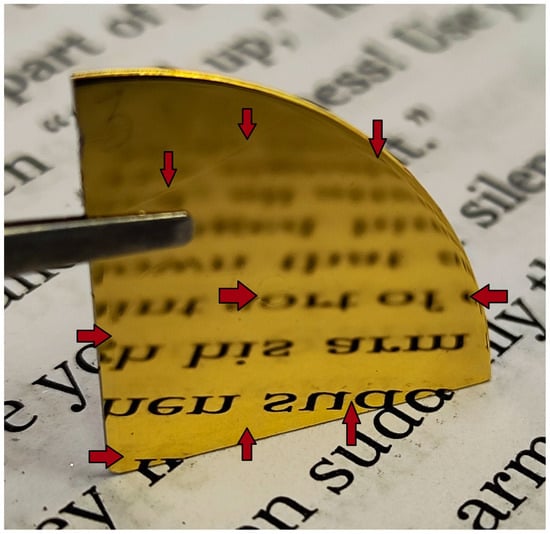

On segment V (the third wave), which is associated with the reduction of gold from the sulfite-thiosulfate complex Au(S2O3)(SO3)25− (reaction (4)), the most uniform and fine-grained structures are formed. At current densities of 7 mA/cm2 (for temperatures of 50 and 65 °C) and 10 mA/cm2 (at 65 °C), deposition is carried out under relatively negative polarization, with potentials reaching −0.45 V. These conditions yield minimal surface roughness values (6–8 nm, Figure 5) and a densely packed, fine-grained microstructure (Figure 4). Under these regimes, the current efficiency remains close to 100%, indicative of a very low hydrogen evolution reaction rate. The hardness of the coatings deposited at 50–65 °C varies in the range of 1.55–2.16 GPa. Deposition at 65 °C and 10 mA/cm2 is characterized by a high growth rate (0.59 µm/min), a homogeneous fine-grained microstructure, and minimal surface roughness of 6 nm. These gold layers exhibit a mirror-like luster, comparable to that of TiAu metallization sputtered onto polished GaAs semiconductor structures. In Figure 7, the electrodeposited gold can be identified by a 2 µm-high step (marked with arrows) resulting from the removal of a chemically resistant lacquer. This step is evident both along the sample perimeter and as a circular feature in its central region.

Figure 7.

A photograph of the sample featuring a gold layer electrodeposited onto a GaAs–TiAu substrate from a sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte at a current density of 4 mA/cm2 and a temperature of 65 °C. The gold layer thickness is 2 µm. Arrows indicate the boundaries of the electrodeposited gold along the perimeter and a circular region of the sputtered TiAu metallization in the center, revealed after the removal of a chemically resistant lacquer.

Gold electrodeposition, as well as the recording of polarization curves, were performed under identical hydrodynamic conditions, with the overhead stirrer rotation speed kept constant and using an electrolyte of the same composition. Under these conditions, the diffusion layer thickness was governed primarily by temperature. This dependence is clearly demonstrated by the increase in the limiting diffusion current densities for the reduction of different gold-containing species (Figure 2, plateaus II, IV, and VI on polarization curves 1–4) with increasing temperature.

It should be noted that at a current density of 7 mA/cm2 and a temperature of 35 °C, the gold deposition—according to the polarization curve (Figure 2, curve 2)—occurs at potentials corresponding to segment VII. In this potential range, the rates of the side reactions (5) and (6) are significant, which explains the recorded gold current efficiency of 83.5% (Table 3). At a current density of 10 mA/cm2 and a temperature of 50 °C, the cathode potential under load also corresponds to segment VII (Figure 2, curve 3), resulting in a current efficiency of 80%. Gold layers deposited at potentials corresponding to region VII of the polarization curves are characterized by minimum surface roughness and maximum hardness. Specifically, at 35 °C and 7 mA/cm2 and at 50 °C and 10 mA/cm2, the surface roughness values Sq are 4 nm and 6.7 nm, while the corresponding microhardness values are 2.17 GPa and 2.22 GPa, respectively (Figure 6).

The observed combination of minimum roughness and maximum microhardness can be attributed to the specific features of the electrocrystallization processes. First, at potentials corresponding to region VII, gold deposition proceeds under conditions of significant cathodic overpotential, which results in a sharp increase in the nucleation rate relative to the growth rate of already formed crystallites. As a consequence, a fine-grained structure with a high density of nuclei is formed, promoting effective surface leveling and leading to low values of surface roughness Sq.

Second, intensive nucleation and rapid growth under mass-transport-limited conditions lead to the formation of coatings with a high density of crystallographic defects, such as grain boundaries and dislocations, which can account for the observed increase in hardness.

Thus, the optimal conditions for gold electrodeposition, ensuring a current efficiency close to 100%, low surface roughness (Sq = 5.8–7.8 nm), and high coating microhardness (1.86–2.18 GPa), correspond to the potentials of region V of the polarization curve at 50 °C and 7 mA/cm2, as well as at 65 °C and 7 and 10 mA/cm2. These regimes enable the formation of uniform fine-grained coatings exhibiting low surface roughness and enhanced mechanical strength.

3.2. Effect of Annealing on the Physical Properties of Gold Layers

In microelectronics, low-temperature annealing (up to 300 °C) is commonly employed after electrochemical deposition to relieve internal stresses and facilitate subsequent soldering processes. To study the effect of annealing on the physical characteristics of gold, the specimens were annealed at 270 °C for 10 min in nitrogen. Thermal treatment altered the properties of the deposited layers: roughness increased (Figure 5) while microhardness dropped (Figure 6).

For samples deposited at potentials corresponding to region VII of the polarization curves (35 °C and 7 mA/cm2; 50 °C and 10 mA/cm2), the effect of annealing on surface roughness and hardness is weak: the roughness changes by less than 3%, while the microhardness varies by 3% and 10% for samples deposited at 35 °C and 50 °C, respectively.

The most pronounced increase in surface roughness accompanied by a simultaneous decrease in hardness (Figure 5 and Figure 6) is observed for samples deposited at 35 °C and 4 mA/cm2, 50 and 65 °C and 7 mA/cm2, as well as at 65 °C and 10 mA/cm2, whose deposition potentials correspond to region V of the polarization curves (Figure 2). For the 35 °C, 4 mA/cm2 regime, annealing leads to a decrease in microhardness from 2.04 to 1.68 GPa (by 18%), while the surface roughness Sq increases from 25 to 31 nm (Figure 5a). At 50 °C and 7 mA cm−2, the hardness decreases from 2.18 to 1.85 GPa (by 15%), accompanied by an increase in roughness from 6–7 to 9–10 nm (Figure 5b). For the 65 °C and 10 mA cm−2 regime, the changes are less pronounced: the hardness decreases from 2.22 to 2.03 GPa, while the roughness increases from 6 to 8 nm (Figure 5c). The microstructure of these specimens was similar: it was represented by agglomerates of grains (Figure 4) the distance between which decreased after annealing (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

AFM image of gold layers deposited from the sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte at different temperatures and current densities after annealing (the section dimensions in the images was 3 × 3 μm).

The microhardness in the as-deposited state is high due to a high density of defects. The large number of grain boundaries impedes dislocation motion, which manifests as high hardness (the Hall–Petch effect).

Annealing of gold films at temperatures of 100–300 °C may lead to grain growth and recrystallization. This observation is consistent with the established literature data on the behavior of thin gold coatings under thermal treatment. The authors of [39] directly correlate this microstructural change with a reduction in hardness [40]. Grain growth weakens the Hall–Petch effect, resulting in material softening. The relief of internal stresses and recrystallization are the primary reasons for softening during low-temperature annealing.

Future studies should include direct microstructural analysis (e.g., XRD, TEM, or EBSD) to conclusively confirm the proposed mechanisms of recrystallization and grain growth responsible for the hardness reduction at elevated temperatures.

The decrease in microhardness after thermal treatment promotes soldering to the deposited gold layers, so it is used in microelectronics to relieve stresses after electrochemical deposition and facilitate soldering.

The high surface roughness in the as-deposited state is attributed to growth kinetics that lead to the formation of protrusions, dendrites, and irregularities at the grain boundaries [41]. Annealing smoothens the surface via thermodynamically driven processes; at elevated temperatures, surface atoms gain high mobility, leading to the minimization of surface energy [42]. The underlying mechanisms are identical to those observed in sputtered gold films, as detailed by Bonyár and Lehoczki in their work [43], where annealing at ~230–420 °C induces grain coalescence and a significant reduction in roughness, as measured by AFM.

3.3. Stability of Sulfite-Thiosulfate Gold Plating Electrolytes

According to Estrine et al. [26], the stability of the sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolyte is determined by dynamic equilibrium between S2O32− and SO32− ligands, the concentration of protons (pH), and cathodic reactions. In fresh solutions with neutral and slightly acidic pH, gradual decomposition of thiosulfate is observed:

S2O32− → S + SO32−

S2O32− + 6H+ + 4e− → 2S + 3H2O

These processes lead to the formation of colloid sulfur, turbidity, and degradation of the active complex [Au(S2O3)2]3−. However, periodic conditioning of the electrolyte reverses the process, improving stability and clarity of the solution.

Estrine et al. have shown a connection of this effect with a number of interrelated factors.

First, the cathodic reaction of hydrogen liberation,

is accompanied with the accumulation of OH− ions and alkalization of the solution, which shifts the equilibrium in thiosulfate decomposition to the left and inhibits sulfur formation.

2H2O + 2e− → H2 + 2OH−

Second, the formed sulfite (SO32−) plays the role of thiosulfate regenerator by bonding sulfur and reducing S2O32−.

Third, in the course of electrolysis, the fraction of mixed complexes [Au(S2O3)(SO3)2]5− that have high stability constant (log β ≈ 30.8, Table 1) increases, while the concentration of less stable [Au(S2O3)2]3− (log β ≈ 23.8–28.7, Table 1) decreases. This stabilizes the chemical composition of the solution and reduces the probability of disproportionation.

Moreover, the reduction of gold concentration due to its precipitation decreases the probability of side reactions of Au(I) reduction in the solution, while quasi-stationary pH (4.5–5.5) minimizes the rate of thiosulfate degradation.

Therefore, electrolyte conditioning promotes self-regulating equilibrium between the ligands and hydroxide ions, which stabilizes the gold complexes and prevents sulfur sedimentation. Estrine et al. [26] have noted that after several months of operation, the electrolyte preserves clarity and activity in the case of periodic cathodic processes and replenishment of sulfite ions.

Similar regularities were discovered by Liew and Roy [44]. The authors have shown that thermostating and long-term conditioning of the sulfite-thiosulfate solutions increased the fraction of stable mixed Au(I) complexes and almost completely eliminated colloid sulfur. The addition of excess Na2SO3 augmented the effect by shifting the equilibrium of reaction (7) to the left and restoring the clarity of the solution. Liew and Roy have also unveiled that bath conditioning was accompanied by an extended potential of gold deposition plateau and decreased polarization overvoltage, which speaks of the stabilization of electroactive complexes and inhibition of side cathodic processes (reduction of SO32− and liberation of H2).

Therefore, the results obtained in [26,44] evidently demonstrated that the use or dosed introduction of excess sulfite ions improves the electrolyte stability due to the regeneration of thiosulfate, stabilization of Au(I) complexes, and elimination of disproportionation products.

Despite the results, the literature still lacks quantitative data on the effect of excess sulfite ions on the precipitate morphology and capability of electrolyte regeneration by excess sulfite ions after its sedimentation. In this connection, the present work states a problem of complex investigation of the effect of excess sulfite ions on the stability of sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolyte, including the following:

- The assessment of the effect of the time of electrolyte storage and usage on the stability of the sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolyte and the morphology of deposited gold layers;

- The analysis of the polarization behavior of the system with 50% excess of sulfite ions;

- The assessment of the sulfur sediment dissolution capability after introducing a 50% excess of sulfite ions and the comparison of the morphology of deposited gold layers before and after electrolyte regeneration.

Such an approach allows for quantitatively confirming the conclusions of Estrine [26] and Liew [44] related to the role of sulfite ions as a regenerator of thiosulfate and electrolyte stabilizer, as well as establishing the conditions for prolonging the life of sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolytes.

3.3.1. Studying the Effect of Storage and Usage Times of Sulfite-Thiosulfate Gold Plating Electrolyte on Its Stability and Morphology of Deposited Gold Layers

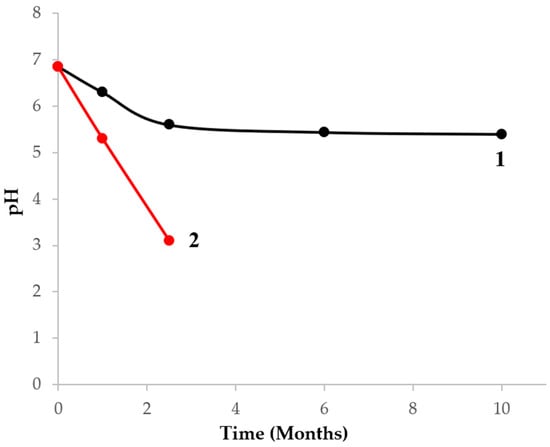

To assess the stability of the sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolyte and the morphology of deposited gold layers affected by the time of electrolyte storage and usage, a portion of the electrolyte was prepared. A colorless clear freshly prepared electrolyte with pH 6.85 was divided into two parts: one part was used to deposit gold, the second one (reference) was used only to analyze pH depending on the storage time. After a month, in the reference portion, a light sediment started to accumulate with a reduction of pH down to 5.3. After 2.5 months, the amount of the sediment in the reference portion increased with further reduction of pH down to 3.1 (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Time dependence of the sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte pH: 1—electrolyte portion after electrochemical deposition, 2—portion without electrochemical deposition.

The sedimentation of rhombic sulfur (identified by XRF) could be due to reactions (7) and (8).

It should be noted that in the electrolyte used for gold electrodeposition, there was no sedimentation. Over 2.5 months, pH reached almost a persistent value of 5.3. The stability of the sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolyte during its usage is conditioned by a number of electrochemical transformations described above.

For instance, after 4.5 years, the sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolyte that was periodically used for gold remained clear (transparent) and showed no signs of sedimentation, despite the gold concentration in it dropping from 9.8 to 8 g/L and the pH value decreasing down to 4.7. The gold layers deposited from this electrolyte were aureate and glossy.

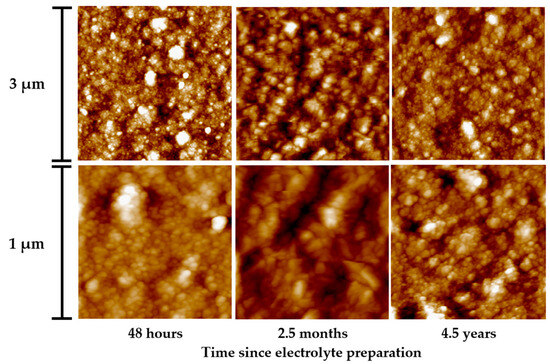

AFM images of 2 µm thick electrodeposited gold layers, deposited at a current density of 10 mA/cm2, are shown in Figure 10. The coatings obtained from a fresh sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte were characterized by smaller grains and greater smoothness as compared to the gold precipitates from the electrolyte stored for 2.5 months. The roughness Sq amounted to 7.8 and 29 nm, respectively.

Figure 10.

AFM images of gold layers deposited from sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolyte. Time after electrolyte preparation: 48 h, 2.5 months and 4.5 years. The thickness of the gold plating was 2 μm, the deposition current density is 10 mA/cm2, and the deposition temperature is 65 °C.

Following the study results, the bath conditioning increases the stability of the electrolyte due to the inhibition of rhombic sulfur sedimentation that accelerates with increasing medium acidity. During electrolyte usage, pH slightly decreases, which yields larger grains and less smooth gold layers as compared to the precipitates from a fresh electrolyte.

While no signs of electrolyte degradation were observed during its periodic use in the present study, a definitive assessment of its long-term stability under operational conditions necessitates further investigation. A pertinent direction for future work involves a systematic study of stability during both storage and operation, with the electrolyte monitored over extended periods. The application of analytical techniques, such as X-ray diffraction (XRD) for phase identification and Raman spectroscopy for tracking molecular transformations within the solution, would provide conclusive evidence regarding its stability limits and the nature of any potential decomposition products.

3.3.2. Analysis of the Polarization Character of Sulfite-Thiosulfate Electrolyte with 50% Excess of Sulfite Ions

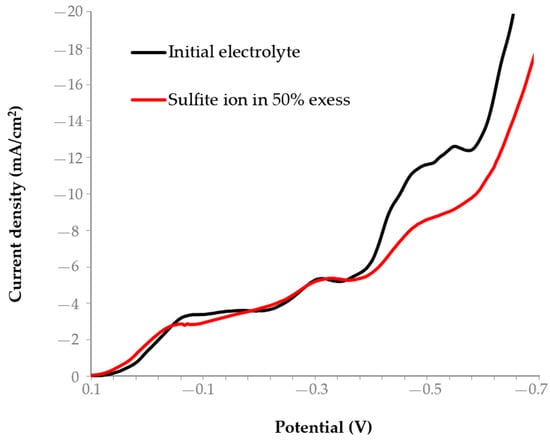

To assess the effect of sulfite ion concentration on electrochemical gold deposition we have recorded polarization curves for the electrolyte with 50% excess of sulfite ions (Figure 11; Table 2, electrolyte 3).

Figure 11.

Influence of sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte composition on the shape of the polarization curves.

At a potential from −0.4 to −0.6 V, the polarization curve of electrolyte 3 demonstrates a drop of the reaction limiting current density from 12 to 9 mA/cm2.

The decrease in the limiting cathodic current density with an introduced excess of sulfite ions may be due to the changed type of the particles dominating in the electrolyte and altered kinetics of Au(I) reduction in the sulfite-thiosulfate system. Increased concentration of SO32− shifts the complexation equilibrium promoting the formation of more stable and less electrochemically active Au(I)-sulfite complexes, as compared to thiosulfate complexes. As a result, the effective concentration of particles reducing near the cathode surface reduces and, due to diffusion limitations, the reaction limiting current drops. Moreover, sulfite can be adsorbed on the specimen’s gold surface, change the structure of the electrical double layer and impede charge transfer. It can also compete for electrons and disturb the relation of gold reduction currents and side processes. The combined effect of these factors reduces the observed limiting cathodic current density at a fixed potential.

3.3.3. Assessing the Capability of Sedimented Sulfur Dissolution by Introduction of Excess Sulfite Ions

The stability of the sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolytes varies from three weeks [33] to several months. The instability of thiosulfate gold plating solutions is due to their susceptibility to disproportionation with the formation of colloid sulfur as per reaction (7), and protonation of S2O32− ions at neutral and acidic pH with the formation of HSO3− ions and elementary sulfur.

These reactions lead to the sedimentation and loss of active gold complexes which makes the bath unusable.

The addition of sulfite (SO32−) shifts the equilibrium of reaction (7) to the left, thus preventing the formation of colloid sulfur and stabilizing the solution. Moreover, the formation of the mixed Au(S2O3)(SO3)25− complex with high stability constant (log β ≈ 30.8, Table 1) enhances the thermodynamic stability of the electrolyte as compared to individual complex [Au(S2O3)2]3− (log β ≈ 23.8–28.7, Table 1). This was confirmed by electrochemical measurements and calculations of Estrine et al. [26], where they have demonstrated that this very mixed complex is the active agent in gold reduction on the Pt electrode in a fresh solution.

During the usage of the sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte, the concentration of sulfite drops due to its oxidation to SO42−, while thiosulfate remains stable. Therefore, compensated sulfite losses may be an effective way to prolong the electrolyte life.

To assess the influence of excess sulfite ions on the ability to dissolve sedimented sulfur, after storage-induced sedimentation, the sulfite-thiosulfate gold plating electrolyte was supplemented with 50% excess of sulfite ions (Table 2, electrolytes 4 and 5). The introduction of excess sulfite ions led to a complete dissolution of sedimented sulfur and raised the electrolyte’s pH from 1.9 to 3.5. To achieve pH 5.7—specific for a fresh electrolyte—after the introduction of sulfite ion, the solution was supplemented with 0.1 M NaOH.

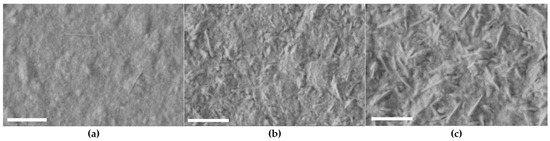

To assess the influence of the sulfite ion concentration and pH on the structure of deposited layers, electrolytes 1, 4, and 5 (Table 2) were used to deposit two microns of gold at a temperature of 65 °C and current density of 10 mA/cm2 (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the gold layers deposited from (a) fresh sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte, (b) regenerated electrolyte with pH 3.5, and (c) regenerated electrolyte with pH 5.7. The thickness of the gold plating was 2 μm, the deposition current density is 10 mA/cm2, and the deposition temperature is 65 °C, scale—500 nm.

The quality of the precipitate after electrolyte regeneration deteriorates: gold layers become more dull and rough. The root mean square roughness Sq of the gold layers deposited from the regenerated electrolytes with pH 3.5 and 5.7 amounted to 12.1 and 35 nm as compared to 7.2 nm for the fresh electrolyte. The structure becomes acicular. Such alteration of the precipitate structure may indicate the change in the composition of reduced gold particles and kinetics of the electrochemical deposition reaction.

4. Conclusions

The studies of electrochemical gold deposition from the sulfite-thiosulfate electrolyte onto GaAs–TiAu substrates allowed establishing the regularities that determine the process kinetics, precipitate morphology, and electrolyte stability during usage and storage.

The temperature regime has a significant effect on both the deposition rate and the coating quality. As the temperature increases from 20 to 65 °C, an increase in current density from 2 to 10 mA/cm2 results in only a slight shift in the deposition potential (from −0.38 V to −0.45 V), which enables a higher deposition rate without deterioration of the deposit morphology. At a current density of 7 mA/cm2 at 50 °C and 7 and 10 mA/cm2 at 65 °C, smooth coatings with low roughness (6–8 nm) and current efficiency close to 100% are obtained. In the cathodic potential range of −0.18 to 0 V vs. NHE, gold reduction proceeds from sulfite complexes [Au(SO3)2]3−. The calculated activation energy for this process decreases from 27.4 kJ/mol to 16.7 kJ/mol as the potential shifts in the negative direction, indicating a change in the reaction mechanism from mixed to diffusion control.

The multistage nature of cathodic gold reduction from sulfite-thiosulfate electrolytes is manifested by the presence of several distinct regions on the polarization curves, corresponding to the successive reduction of different Au(I) complex species, which occur predominantly under diffusion-controlled conditions. In the cathodic potential range of −0.18 to 0 V vs. NHE, gold reduction proceeds from sulfite complexes [Au(SO3)2]3−. The calculated activation energy for this process decreases from 27.4 kJ/mol to 16.7 kJ/mol as the potential shifts in the negative direction, indicating a change in the reaction mechanism from mixed to diffusion-controlled.

With a further increase in the cathodic potential (−0.20 to −0.38 V), the reduction of the Au(S2O3)23− complex becomes possible, which also proceeds under diffusion control. In the range of potentials from −0.38 to −0.55 V, the stable Au(S2O3)(SO3)25− complex reduces with the change in the mechanism from diffusion to the mixed one. This section provides the formation of dense fine-crystalline glossy precipitates at high current yield, which indicates an effective reduction of active forms of Au(I) with minimal contribution of side processes.

At more negative potentials (below −0.55 V), the process enters the section with simultaneous reactions of sulfite ion reduction and hydrogen liberation, which lowers the gold deposition current yield and induces surface defects.

Low-temperature annealing of the electrodeposited gold layers at 270 °C for 10 min results in an increase in surface roughness and a decrease in hardness, with the effect being most pronounced for samples deposited at 35 °C and 4 mA cm−2, 50 and 65 °C and 7 mA/cm2, as well as at 65 °C and 10 mA/cm2, whose deposition potentials correspond to region V of the polarization curves.

A study of the electrolyte’s stability over time showed that in a portion of the electrolyte from which no electrochemical deposition was carried out, a decrease in pH to 3.1 and the precipitation of rhombic sulfur were observed after 2.5 months due to the disproportionation reaction of thiosulfate. In contrast, the electrolyte from which gold was electrodeposited remained transparent and stable for more than 4 years, which is explained by cathodic alkalinization of the medium and the suppression of the sulfur sedimentation reaction.

The introduction of 50% excess sulfite ions effectively dissolves sedimented sulfur and recovers the solution clarity. However, this lowers pH and deteriorates the precipitate quality: roughness increases and grains take an acicular form. This indicates the stabilization of the solution by excess sulfite, but changes the composition of the active gold complex and alters the reduction kinetics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.; methodology, M.V., T.B. and T.O.; validation, M.V., T.B. and A.T.; formal analysis, M.V.; investigation, M.V.; resources, E.B.; data curation, M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V. and A.T.; writing—review and editing, T.B. and T.O.; visualization, A.T.; supervision, T.O.; project administration, I.K.; funding acquisition, E.B. and M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The results were obtained within the state assignment of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (theme no. FEWM-2024-0008) (conceptualization and study design, experimental research) and as part of the Tomsk University of Systems Control and Radioelectronics Development Program for 2025–2036 under the Strategic Academic Leadership Program “Priority 2030” (access to research facilities and instrumentation, acquisition of reagents, materials, and equipment).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Science Research Institute of Semiconductor Devices and personally I.D. Filimonova and N.G. Garber for their support in performing the analyses for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Mariya Vaisbekker and Tatiyana Bekezina received funding from the Science Research Institute of Semiconductor Devices, JSC (634034, Tomsk, Russian Federation) for methodology development, which supported part of the work presented in this manuscript.

References

- Green, T.A. Gold electrodeposition for microelectronic, optoelectronic and microsystem applications. Gold Bull. 2007, 40, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaka, T.; Okinaka, Y.; Sasano, J.; Kato, M. Development of new electrolytic and electroless gold plating processes for electronics applications. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2006, 7, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlin, H.; Frisk, T.; Åstrand, M.; Vogt, U. Miniaturized Sulfite-Based Gold Bath for Controlled Electroplating of Zone Plate Nanostructures. Micromachines 2022, 13, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Złotnik, S.; Wróbel, J.; Boguski, J.; Nyga, M.; Kojdecki, M.A.; Wróbel, J. Facile and Electrically Reliable Electroplated Gold Contacts to p-Type InAsSb Bulk-Like Epilayers. Sensors 2021, 21, 5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Giacomozzi, F.; Cian, A.; Giubertoni, D.; Lorenzelli, L. Enhancing the Deposition Rate and Uniformity in 3D Gold Microelectrode Arrays via Ultrasonic-Enhanced Template-Assisted Electrodeposition. Sensors 2024, 24, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serga, V.; Zarkov, A.; Shishkin, A.; Melnichuks, M.; Pankratov, V. Investigation of the Impact of Electrochemical Hydrochlorination Process Parameters on the Efficiency of Noble (Au, Ag) and Base Metals Leaching from Computer Printed Circuit Boards. Metals 2024, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero, M.; Alonso, C. Deposition of nanostructurated gold on n-doped silicon substrate by different electrochemical methods. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2010, 40, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depestel, L.M.; Strubbe, K. Influence of the crystal orientation on the electrochemical behaviour of n-GaAs in Au(i)-containing solutions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskam, G.; Searson, P.C. Electrochemical nucleation and growth of gold on silicon. Surf. Sci. 2000, 446, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.J.; Strom, N.E.; Simoska, O. Electrochemical deposition of gold nanoparticles on carbon ultramicroelectrode arrays. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 16204–16217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, G. Electrochemical Deposition of Gold Nanoparticles on Reduced Graphene Oxide by Fast Scan Cyclic Voltammetry for the Sensitive Determination of As(III). Nanomaterials 2018, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finot, M.O.; Braybrook, G.D.; McDermott, M.T. Characterization of electrochemically deposited gold nanocrystals on glassy carbon electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1999, 466, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrokhian, S.; Rastgar, S. Electrochemical deposition of gold nanoparticles on carbon nanotube coated glassy carbon electrode for the improved sensing of tinidazole. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 78, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Razazzadeh, A.; Khan, H.; Kwon, S. Catalysts Design and Atomistic Reaction Modulation by Atomic Layer Deposition for Energy Conversion and Storage Applications. Exploration 2025, 5, e20240010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanij, F.D.; Latyshev, V.; Vorobiov, S.; You, H.; Volavka, D.; Samuely, T.; Komanicky, V. Preparation of ultrathin sputtered gold films on palladium as efficient oxygen reduction electro-catalysts. Mol. Catal. 2024, 567, 114461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, P. Nanoporous gold: A review and potentials in biotechnological and biomedical applications. Nano Sel. 2021, 2, 1437–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Q.; Bai, G.; Li, S. A Designed Twist Sensor Based on the SPR Effect in the Thin-Gold-Film-Coated Helical Microstructured Optical Fibers. Sensors 2022, 22, 5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulowski, W.; Skibińska, K.; Żabiński, P.; Wojnicki, M. Optimization of Gold Thin Films by DC Magnetron Sputtering: Structure, Morphology, and Conductivity. Coatings 2025, 15, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.P.; Dos Santos, P.S.S.; Dias, B.; Núñez-Sánchez, S.; Pastoriza-Santos, I.; Pérez-Juste, J.; Pereira, C.M.; Jorge, P.A.S.; De Almeida, J.M.M.M.; Coelho, L.C.C. Exciting Surface Plasmon Resonances on Gold Thin Film-Coated Optical Fibers Through Nanoparticle Light Scattering. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2400433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiraju, A.; Munjal, R.; Viehweger, C.; Al-Hamry, A.; Brahem, A.; Hussain, J.; Kommisetty, S.; Jalasutram, A.; Tegenkamp, C.; Kanoun, O. Towards Embedded Electrochemical Sensors for On-Site Nitrite Detection by Gold Nanoparticles Modified Screen Printed Carbon Electrodes. Sensors 2023, 23, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihăilescu, M.; Negrea, A.; Ciopec, M.; Negrea, P.; Duțeanu, N.; Grozav, I.; Svera, P.; Vancea, C.; Bărbulescu, A.; Dumitriu, C. Ștefan Full Factorial Design for Gold Recovery from Industrial Solutions. Toxics 2021, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesiulis, H.; Tsyntsaru, N. Eco-Friendly Electrowinning for Metals Recovery from Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE). Coatings 2023, 13, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaisbekker, M.S.; Ostanina, T.N.; Loginova, L.V.; Bekezina, T.P.; Chichevskaya, Y.V. Comparative Study of the Processes of Electrochemical Deposition of Gold From Cyanide and Sulphite-Thiosulphate Electrolytes. Galvanotekhnika I Obrab. Poverkhnosti 2022, 30, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatgadde, L.G.; Petersen, D.R. A thiosulfate–sulfite gold electroplating process for microelectronics. In Proceedings of the Conference on Environmentally Acceptable Electroplating Processes, Orlando, FL, USA, 2001; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Osaka, T.; Kodera, A.; Misato, T.; Homma, T.; Okinaka, Y.; Yoshioka, O. Electrodeposition of Soft Gold from a Thiosulfate-Sulfite Bath for Electronics Applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 3462–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrine, E.C.; Riemer, S.; Venkatasamy, V.; Stadler, B.J.H.; Tabakovic, I. Mechanism and Stability Study of Gold Electrodeposition from Thiosulfate-Sulfite Solution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, D687–D696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, W.N.; Senanayake, G.; Nicol, M.J. Interaction of gold(I) with thiosulfate–sulfite mixed ligand systems. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2005, 358, 2183–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.A.; Roy, S. Speciation Analysis of Au(I) Electroplating Baths Containing Sulfite and Thiosulfate. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, C157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrūnas, G.; Valiūnienė, A.; Vienožinskis, J.; Gaidamauskas, E.; Jankauskas, T.; Margarian, Ž. Electrochemical gold deposition from sulfite solution: Application for subsequent polyaniline layer formation. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2008, 38, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Kou, J.; Sun, C. Investigation on Gold–Ligand Interaction for Complexes from Gold Leaching: A DFT Study. Molecules 2023, 28, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stezeryanskii, E.; Vyunov, O.; Omelchuk, A. Determination of the Stability Constants of Gold(I) Thiosulfate Complexes by Differential UV Spectroscopy. J. Solut. Chem. 2015, 44, 1749–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, Q.; Xu, B.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, T. An Electrochemical Study of Gold Dissolution in Thiosulfate Solution with Cobalt–Ammonia Catalysis. Metals 2022, 12, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, M.; Sadri, F.; Zhang, S.; Ghahreman, A. The Role of Thiosulfate and Sulfite in Gold Thiosulfate Electrowinning Process: An Electrochemical View. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 166, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, G. The role of ligands and oxidants in thiosulfate leaching of gold. Gold Bull. 2005, 38, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromberg, A.G.; Semchenko, D.P. Physical Chemistry; Vysshaya Shkola: Moscow, Russia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kublanovsky, V.S.; Nikitenko, V.M. Actual Activation Energy of the Electroreduction of Iminodiacetate Complexes of Palladium (II). Nac. Akad. Nauk Ukr. 2017, 2, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Danilov, F.I.; Protsenko, V.S. Actual activation energy of electrode process under mixed kinetics conditions. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2009, 45, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 1992, 7, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloyer, D.D.; Winchell, P.G.; Phillips, R.W.; Lund, M.R. Recrystallization of Compacted Gold Foil Specimens. J. Dent. Res. 1977, 56, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Huang, H.; Xu, F.; Lu, P.; Chen, Y.; Shen, J.; Ye, G.; Gao, F.; Yan, B. Thermal Annealing Effect on Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering of Gold Films Deposited on Liquid Substrates. Molecules 2023, 28, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, L.; Salvarezza, R.C.; Herrasti, P.; Ocón, P.; Vara, J.M.; Arvia, A.J. Dynamic-scaling exponents and the roughening kinetics of gold electrodeposits. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 52, 2032–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potejanasak, P.; Duangchan, S. Gold Nanoisland Agglomeration upon the Substrate Assisted Chemical Etching Based on Thermal Annealing Process. Crystals 2020, 10, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonyar, A.; Lehoczki, P. An AFM study regarding the effect of annealing on the microstructure of gold thin films. In Proceedings of the 36th International Spring Seminar on Electronics Technology, Alba Iulia, Romania, 8–12 May 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- J-Liew, M.; Sobri, S.; Roy, S. Characterisation of a thiosulphate–sulphite gold electrodeposition process. Electrochim. Acta 2005, 51, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.