Abstract

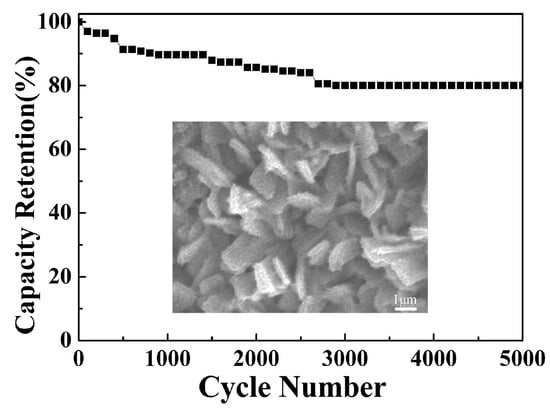

Herein, an electrochemically activated zinc–cobalt-layered double hydroxide/nickel–cobalt-sulfide (EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS) hierarchical composite electrode was fabricated in situ via coupled hydrothermal synthesis and electrodeposition. The influence of electrolyte concentration on the activation efficiency was systematically analyzed, and the corresponding effects of electrochemical activation on each component were elucidated. Benefiting from the introduction of the Zn component and subsequent electrochemical activation, the composite electrode exhibits a marked performance enhancement. The EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode achieves a high areal specific capacitance (Cs) of 11.39 F cm−2 at 4 mA cm−2, maintains 70.15% of this value when the current density is increased ten-fold, and retains 80.05% of its initial capacity after 5000 cycles.

1. Introduction

The continuously increasing global energy demand underscores the urgency of efficient energy storage technologies. Electrochemical storage devices and their pivotal role in improving energy-utilization efficiency are therefore highlighted. As core components of energy storage devices, electrode materials have consistently attracted extensive research attention [1,2,3]. Among the various electrode materials, Co(OH)2, a typical pseudocapacitive electrode material, stands out because of its exceptional merits: high theoretical specific capacitance, unique structural characteristics, good conductivity, and cycling stability [4]. Moreover, cobalt-based bimetallic hydroxides/sulfides and their composites have been designed and constructed by optimizing preparation routes such as hydrothermal methods, co-precipitation, and electrodeposition. Various hierarchical or composite structures are thereby obtained, effectively improving the energy storage performance of the electrodes [5,6,7]. For example, Markhabayeva et al. used a two-step hydrothermal method to prepare a NiCo2S4 electrode that delivered a specific capacity of 8.1 F cm−2 at a discharge current density of 5 mA cm−2 [8]. Similarly, Jiang et al. combined electrodeposition with hydrothermal synthesis to fabricate CoSe2@NiCo-LDH composite electrodes that achieved a specific capacity of 6.06 F cm−2 at 6 mA cm−2 [9].

Recognizing that the composition and preparation methods are the two key factors in breaking through the energy storage limits of electrode materials, researchers have extended their efforts beyond the aforementioned composite systems. Extensive studies have employed heteroatom doping to modulate the host band structure, thereby enhancing intrinsic conductivity, optimizing charge transfer kinetics, or creating new active sites via dopant-induced lattice defects. For example, Zheng et al. reported Mn-doped Co9S8@Co(OH)2 electrodes exhibiting a specific capacity of 5.62 F cm−2 at a discharge current density of 1.5 m A cm−2 [10].

In view of these considerations and with the aim of mitigating the toxicity and cost of cobalt-based compounds, Zn–Co-layered double hydroxides (ZnCo-LDHs) were prepared by simple hydrothermal synthesis to reduce the overall cobalt content [11,12]. Meanwhile, electrodeposition technology has emerged as an important route for preparing hierarchical composites, offering the unique advantages of controllable stepwise growth with precise layer control, short processing times, high reproducibility, and operational simplicity [13]. Additionally, an electrochemical activation strategy has been implemented to induce controlled compositional and structural transitions that expand ion/electron transport pathways, thereby enhancing the intrinsic electrochemical activity of the electrode material [14,15]. For example, Hong et al. synthesized NiCo-hydroxysulfide and, after activating it in 6 M KOH by cyclic voltammetry, achieved a specific capacity more than twice that obtained with 1 M KOH [16]. Meanwhile, Hong et al. prepared a CoS/NiMn-LDH electrode and subjected it to a 10-cycle charge/discharge activation, yielding about 1.4 times the original specific capacity [17].

Guided by the above analysis and focusing on composition regulation and synthetic methodology as the two pivotal breakthroughs, this study integrates hydrothermal synthesis with electrodeposition to construct a ZnCo-LDH/nickel–cobalt-sulfide (NCS) composite electrode, while systematically evaluating the influence of electrochemical activation on electrode performance. The hierarchical design and activation strategy presented herein provide experimental evidence for the structural and performance modulation of composite electrodes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Nickel foam (NF, 100 PPI, Kunshan Dessco Co., Ltd., Kunshan, China) substrates (1.0 cm × 1.5 cm) were first sliced and then subjected to sequential washing with dilute HCl, ethanol, and deionized water to remove surface oxides and impurities. All chemicals and reagents employed were of analytical grade and purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China.

2.2. Stepwise Fabrication of EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS) and EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS Electrodes

The pretreated NF was immersed in a mixed aqueous solution containing 0.05 M Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 0.025 M Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, and 0.3 M CH4N2O. A hydrothermal reaction was then carried out at 120 °C for 6 h, after which the product ZnCo-LDH was removed and rinsed successively with ethanol and deionized water.

A mixed solution containing 0.05 M NiCl2·6H2O, 0.05 M CoCl2·6H2O, and 0.5 M CH4N2S was prepared. A three-electrode system was assembled with the ZnCo-LDH from the previous step as the working electrode, and a platinum foil and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) acting as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. A constant potential of −1.1 V was applied for 180 s. After deposition, the resulting zinc–cobalt-layered double hydroxide/nickel–cobalt-sulfide (ZnCo-LDH/NCS) composite electrode was rinsed with deionized water and ethanol, and then dried for characterization. For comparison, single-component ZnCo-LDH and NCS electrodes were also prepared by the same method and are denoted as ZnCo-LDH and NCS, respectively.

Electrochemical activation (EA) was performed by 25 consecutive cyclic voltammetry cycles at 5 mV s−1 in a three-electrode configuration with 1, 3, 5, or 7 M KOH as the electrolyte. After activation, the ZnCo-LDH/NCS composite electrode is designated EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS); the single-component ZnCo-LDH and NCS electrodes are designated EA ZnCo-LDH and EA NCS, respectively. Depositing the NCS layer onto the activated EA ZnCo-LDH surface gives the composite electrode designated EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS.

2.3. Characterization

The surface morphology and elemental composition of the electrodes were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-7610F 15.0 kV, Tokyo, Japan), X-ray diffractometry (XRD, Cu Kα radiation with λ = 1.5406 Å, Shimadzu Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALAB 250Xi, ThermoFisher Scientifific Co., Ltd, Waltham, MA, USA, Al Kα as X-ray source). Electrochemical performance was evaluated by cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and long-term cycling tests using a CHI760E electrochemical workstation (Shanghai Chenhua Instrument Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). A three-electrode configuration was employed with the as-prepared ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode as the working electrode, a Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference, a Pt foil as the counter electrode, and 2 M NaOH as the electrolyte.

3. Results

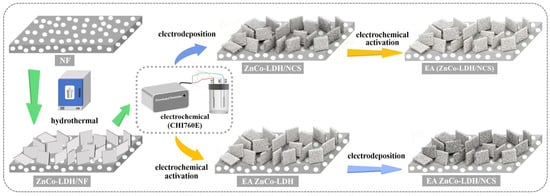

Figure 1 illustrates the fabrication procedures of the two electrodes. First, ZnCo-LDH nanosheets are grown in situ on NF via a hydrothermal reaction. The process then splits into two routes. In one, a NCS layer is uniformly electrodeposited onto the ZnCo-LDH surface. After the ZnCo-LDH/NCS composite is assembled, electrochemical activation is performed to yield the EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS) electrode. For comparison, a parallel route carries out the activation before NCS deposition, giving the EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the stepwise fabrication processes for the EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS) and EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrodes.

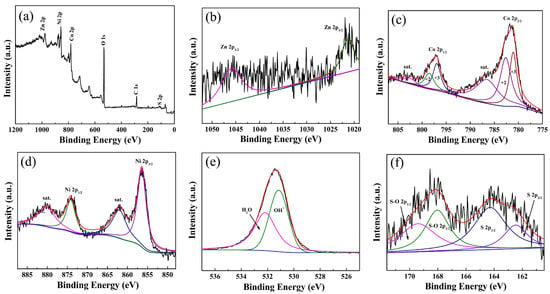

The XRD patterns of ZnCo-LDH, EA ZnCo-LDH, and EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS are presented in Figure S1. The three strongest peaks at 44.6°, 51.9°, and 76.5° arise from the NF substrate. The remaining broad, low-intensity reflections can be indexed to the (003), (012), and (015) planes of the hydrotalcite-like LDH phase, which are in good agreement with the previous report [18,19], indicating that the layered structure is retained after deposition of the NCS layer, albeit with limited crystallinity. Figure 2a presents the XPS survey spectrum of EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS, revealing clear photoelectron signals for Zn 2p, Ni 2p, Co 2p, O 1s, C 1s, and S 2p. In the Zn 2p region (Figure 2b), the signals at 1045.9 and 1021.3 eV are assigned to Zn 2p1/2 and Zn 2p3/2, respectively [20]. These two peaks are attenuated after the activation treatment. For comparison, Figure S2 displays the Zn 2p spectrum of the hydrothermal reaction without electrochemical activation. The Co 2p spectrum (Figure 2c) exhibits spin–orbit splitting into 2p1/2 components at 798.49 and 796.94 eV and 2p3/2 components at 782.64 and 781.09 eV, together with shake-up satellites at around 802.6 and 786.5 eV; this multiplet structure confirms the coexistence of Co2+ and Co3+ [21]. The Ni 2p region (Figure 2d) shows characteristic peaks at 874.12 eV (2p1/2) and 856.42 eV (2p3/2), accompanied by satellite peaks at about 880.13 and 862 eV [20]. The O 1s envelope (Figure 2e) is deconvoluted into two components at 532.18 eV (adsorbed H2O) and 531.15 eV (bound OH−) [16]. The S 2p spectrum (Figure 2f) is resolved into two doublets: the first at 164.29 eV and 162.47 eV corresponds to 2p1/2 and 2p3/2, whereas the second at 169.41 eV (2p1/2) and 168.04 eV (2p3/2) arises from S-O bonding generated by the reaction of sulfur species with OH− released during thiourea hydrolysis [22].

Figure 2.

XPS spectra of (a) survey scan, (b) Zn 2p, (c) Co 2p, (d) Ni 2p, (e) O 1s, and (f) S 2p for EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode.

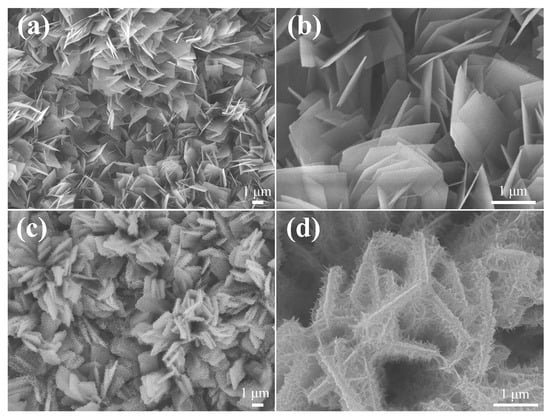

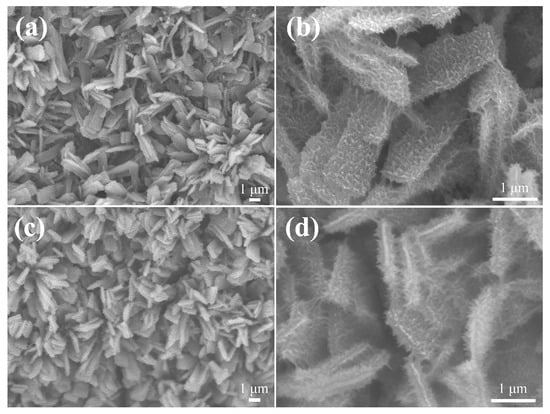

Figure 3a depicts the FE-SEM image of the pristine ZnCo-LDH electrode. Dense ZnCo-LDH nanosheets are uniformly distributed on the NF substrate, and the surface of these nanosheets is relatively smooth and flat, with a thickness of about 18 nm (Figure 3b). Following NCS layer deposition, these nanosheets displayed a substantial thickening and a denser spatial distribution (Figure 3c). At higher magnification, in Figure 3d, the intertwined networks are seen to tightly envelop these nanosheets like a dense layer of burrs.

Figure 3.

SEM images of (a,b) ZnCo-LDH and (c,d) ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrodes recorded at different magnifications.

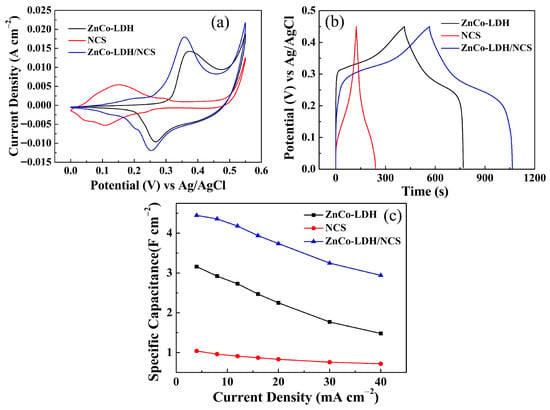

Figure 4a compares the CV curves (recorded at 5 mV s−1 in 2 M NaOH) of the ZnCo-LDH, NCS, and ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrodes. The composite electrode exhibits the strongest current response, substantially exceeding those of the single-component ZnCo-LDH and NCS electrodes, indicating superior energy storage capability. Consistently, GCD tests at 4 mA cm−2 (Figure 4b) reveal that the ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode affords the longest discharge time, followed by ZnCo-LDH, whereas NCS delivers the shortest. The pseudocapacitive behavior is attributed to the following electrochemical reaction [23,24,25]:

Figure 4.

Electrochemical performance comparison of ZnCo-LDH, NCS, and ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrodes: (a) CV curves; (b) GCD curves; (c) Cs at various current densities.

The zinc component hardly participates in the above redox reactions, though it may promote the formation of the Zn-Co composite nanosheet structure. Moreover, Zn(OH)2, as a typical amphoteric hydroxide, acts as a structure-directing agent in our reaction system, as previously reported [20]. The Cs values of the three electrodes at various current densities are summarized in Figure 4c. The trend is fully consistent with the CV results and corroborates the effectiveness of combining ZnCo-LDH with Co(OH)2.

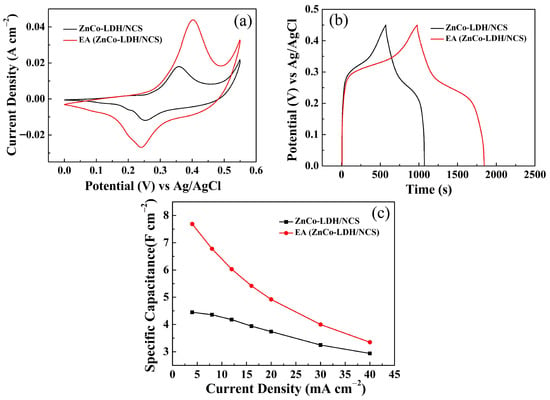

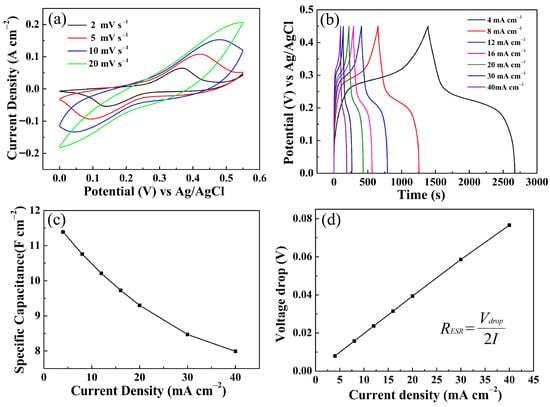

Remarkably, the ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode gained an additional performance boost after electrochemical activation in 1 M KOH [designated as EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS)]. Figure 5 compares the CV and GCD curves before and after this activation. Both the current response (Figure 5a) and the discharge duration (Figure 5b) of the EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS) electrode increase markedly, demonstrating enhanced energy storage capability.

Figure 5.

Electrochemical performance comparison of ZnCo-LDH/NCS and EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS) electrodes: (a) CV curves; (b) GCD curves; (c) Cs at various current densities.

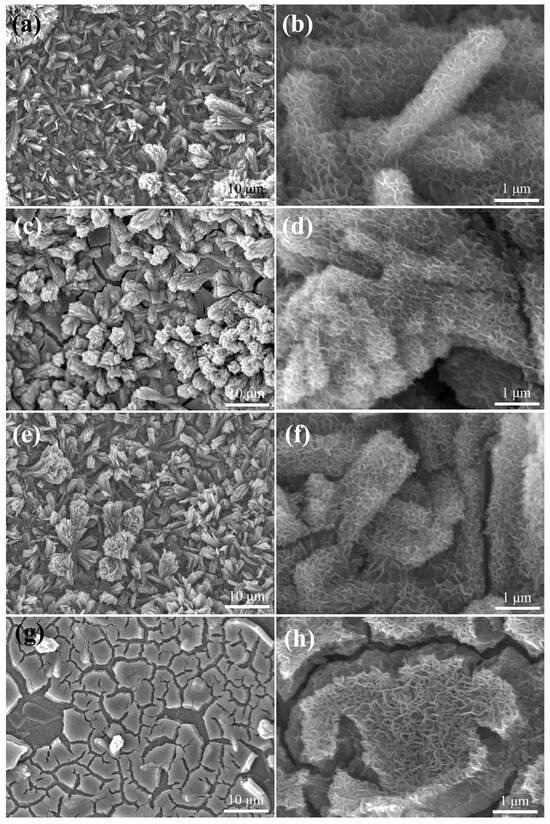

Figure 6 presents FE-SEM images of the ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrodes after cyclic voltammetry electrochemical activation at different electrolyte concentrations. At a low KOH concentration of 1 M, numerous curved nanoflakes form on the hierarchical surface (Figure 6a,b); these nanoflakes are approximately 20 nm thick and interweave with one another. When the concentration is raised to 3 M (Figure 6c,d), the nanoflakes become markedly denser, and this trend persists as the concentration is increased to 5 M (Figure 6e,f). Further increasing the concentration to 7 M causes excessive stacking of the nanoflakes, destroying the hierarchical architecture and generating numerous cracks.

Figure 6.

FE-SEM images of EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS) electrodes activated in different KOH concentrations: (a,b) 1 M, (c,d) 3 M, (e,f) 5 M, and (g,h) 7 M.

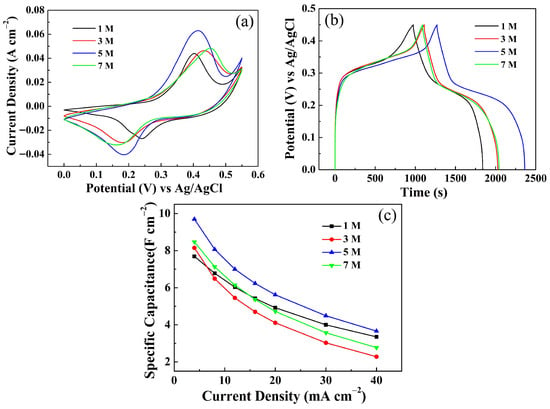

To further confirm the effectiveness of the activation treatment, composite electrodes were subjected to electrochemical activation in KOH electrolytes of 1, 3, 5, and 7 M. The corresponding activation profiles are displayed in Figure S3. At the same time, post-activation CV (Figure 7a) and GCD (Figure 7b) tests of the four electrodes reveal a progressive enhancement in activation efficiency with increasing electrolyte concentration, reaching an optimum at 5 M and delivering 9.70 F cm−2 at 4 mA cm−2. Further elevation to 7 M leads to a performance decline. The CS values of the four electrodes at various discharge current densities are summarized in Figure 7c. These systematic results corroborate the validity of this strategy and elucidate its concentration-dependent behavior.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the electrochemical performance of ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrodes activated with four different electrolyte concentrations: (a) CV curves; (b) GCD curves; (c) Cs at various current densities.

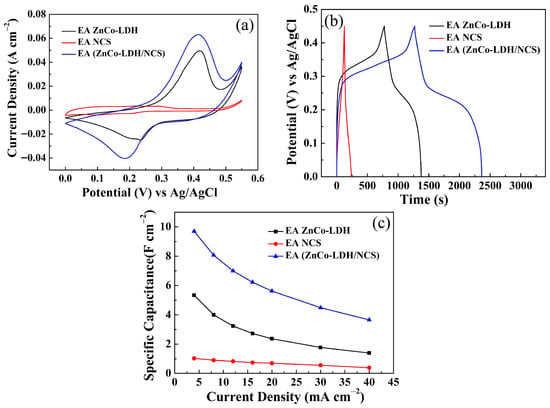

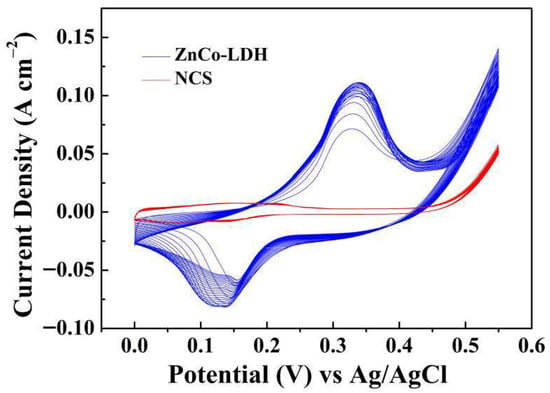

To further clarify the influence of activation treatment on each component, single-component ZnCo-LDH and NCS electrodes and the ZnCo-LDH/NCS composite electrodes were compared after identical activation treatment in 5 M KOH; the activation profiles are displayed in Figure S4. Subsequent CV (Figure 8a) and GCD (Figure 8b) measurements of the three electrodes demonstrate that the composite electrode retains the most pronounced energy storage behavior, which is confirmed in Figure 8c. When the activation responses are evaluated individually, the ZnCo-LDH electrode exhibits a marked increase in current response, whereas the NCS electrode remains almost unchanged, as shown in Figure 9. These observations substantiate that the ZnCo-LDH component is the predominant contributor to the electrochemical activation process.

Figure 8.

Electrochemical performance comparison of EA ZnCo-LDH, EA NCS, and EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS) electrodes: (a) CV curves; (b) GCD curves; (c) Cs at various current densities.

Figure 9.

Electrochemical activation curves of ZnCo-LDH and NCS electrodes.

Figure 10a depicts the SEM image of hydrothermally grown ZnCo-LDH nanosheets after electrochemical activation. These dense nanosheets retain their original alignment on the NF substrate. At higher magnification, their surfaces appear extremely rough, as if short, thick filaments had been drawn out (Figure 10b). After NCS layer deposition (Figure 10c,d), the overall morphology closely matches that shown in Figure 6f.

Figure 10.

FE-SEM images of (a,b) EA ZnCo-LDH and (c,d) EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrodes at different magnifications.

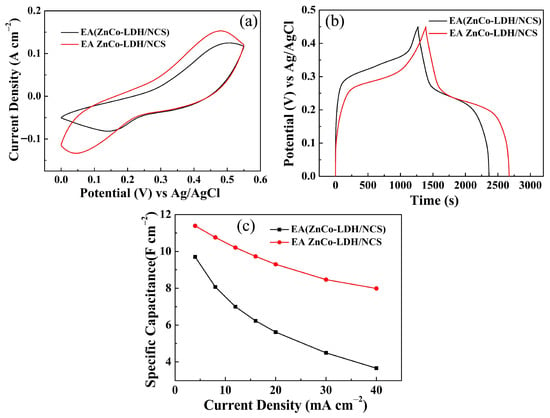

Based on the preceding analysis, a ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode in which only the ZnCo-LDH layer was electrochemically activated was fabricated and denoted EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS. Its energy storage performance was compared with that of the EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS) electrode. Both CV (Figure 11a) and GCD (Figure 11b) data consistently reveal the superior characteristics of EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS, thus confirming that electrochemical activation of ZnCo-LDH provides the primary contribution to the specific capacity. In addition, the EIS spectra of the EA ZnCo-LDH, NCS, and EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrodes are compared in Figure S5. The results demonstrate that the Rct of the EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS composite electrode is smaller than that of the single-component EA ZnCo-LDH and NCS, confirming accelerated interfacial ion diffusion and thereby facilitating electrochemical reactions [20,21].

Figure 11.

Electrochemical performance comparison of EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS) and EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrodes: (a) CV curves; (b) GCD curves; (c) Cs at various current densities.

Therefore, the energy storage characteristics of the EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode were systematically investigated. Figure 12a presents the CV curves recorded at various scan rates. Within a potential window of 0–0.55 V, the profile of the CV response remained essentially unchanged. As the scan rate increased, the peak positions shifted toward the edges of the window and the absolute value of current response progressively increased. In fact, lower scan rates allow for more extensive contact between the electrochemically active sites and the OH− in the electrolyte, thereby enabling a more complete electrochemical reaction [26]. The GCD curves recorded at various current densities are presented in Figure 12b. The results show that the electrode discharge time increases monotonically with decreasing current density. At a current density of 4 mA cm−2, the discharge duration reaches 1281 s, yielding a high Cs of 11.39 F cm−2 as calculated by the standard formula [27,28] (see Supplementary Materials). At 40 mA cm−2, the discharge duration is 90 s and the Cs is 7.99 F cm−2. This suggests that, at lower current densities, the prolonged residence time of OH− at the electrochemically active sites drives the redox reactions to completion, thereby enhancing charge storage utilization [29]. Figure 12c reveals the dependence of Cs on current density. Upon a ten-fold increase in current density, the Cs decays by only 29.85%. In addition, the voltage drop curve was plotted from the GCD test data, and the average RESR calculated using the inserted equation was 0.95 Ω cm−2 [24,27] (see Supplementary Materials).

Figure 12.

Electrochemical performance of EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode: (a) CV curves; (b) GCD curves; (c) Cs; and (d) voltage drops at various current densities.

Figure 13 depicts the long-term cycling stability of the EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode evaluated over 5000 consecutive charge–discharge tests. After 2900 cycles, the Cs stabilizes at approximately 80.05% of its initial value and thereafter shows negligible further decay. The observed Cs fade can be attributed to the partial irreversible internal structural collapse of the activated electrode during prolonged charge–discharge cycling, which reduces the accessible electrochemically active sites. The inset shows an SEM image of the EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode after electrochemical testing, which confirms that the overall hierarchical structure remains essentially unchanged, although partial cross-linking is observed within the NCS layer.

Figure 13.

Cycling stability of the EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode; the inset shows the post-test FE-SEM image.

Table 1 summarizes the test conditions and Cs values of representative electrodes reported in the literature. The EA-ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode fabricated in this study demonstrates superior capacitive performance. This enhancement can be rationalized by the following aspects: (1) Expedient and precisely tunable fabrication. The hydrothermal synthesis step ensures the crystallinity and preferred orientation of ZnCo-LDH nanosheets, whereas the subsequent electrodeposition step allows precise, room-temperature tuning of the active-layer thickness and mass loading without the need for high-temperature annealing or polymeric binders [18,30,31]. (2) Compositional synergy. The partial substitution of Co by Zn to form the ZnCo-LDH electrode markedly reduces cobalt content and its inherent toxicity, while the dynamic dissolution–redeposition reconstruction mechanism of Zn in alkaline media continuously regenerates electrochemically active sites and thereby increases the Cs [11]. (3) Electrochemical activation that engenders lattice defects and cation vacancies within the ZnCo-LDH framework synchronously optimizes the density of effective active sites and the ionic/electronic transport pathways, and thus markedly enhances the Cs and rate performance of the electrode [12,32,33,34,35]. (4) Activation efficacy was systematically evaluated by comparing the overall composite electrode under KOH concentrations of 1, 3, 5, and 7 M, while parallel tests were conducted on EA ZnCo-LDH and EA NCS electrodes. This systematic comparison established the optimal activation condition and corroborated that the synergistic combination of composite architecture and controlled electrochemical activation is essential for the observed performance enhancement.

Table 1.

Cs evaluation of representative electrodes.

4. Conclusions

In the present system, ZnCo-LDH was first grown in situ on NF substrates via a hydrothermal route, followed by electrodeposition of a NCS layer to yield the ZnCo-LDH/NCS composite electrode. On the one hand, ZnCo-LDH/NCS was electrochemically activated in electrolytes of different concentrations to obtain the EA (ZnCo-LDH/NCS) electrode. The impact of activation concentration was systematically compared and analyzed, and at 5 M, the electrode reached 9.70 F cm−2 at 4 mA cm−2. On the other hand, the composite electrode obtained by depositing a NCS layer onto pre-electrochemically activated ZnCo-LDH, designated EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS, exhibited the most favorable energy storage performance, delivering a Cs of 11.39 F cm−2 at 4 mA cm−2 and retaining 80.05% of its initial capacity after 5000 cycles. This electrochemical activation strategy is readily extendable to the rational design of other hierarchical composite electrodes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/coatings16010113/s1. Figure S1: XRD patterns of ZnCo-LDH, EA ZnCo-LDH, and EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS. Figure S2: XPS spectra of Zn 2p for ZnCo-LDH electrode. Figure S3: Electrochemical activation curves of ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrode with four different electrolyte concentrations: (a) 1 M; (b) 3 M; (c) 5 M; (d) 7 M. Figure S4. Electrochemical activation curves of (a) ZnCo-LDH, (b) NCS, and (c) ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrodes. Figure S5. EIS spectra of EA ZnCo-LDH, NCS. and EA ZnCo-LDH/NCS electrodes; formula for calculating the Cs and RESR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W.; methodology, W.D.; software, S.W.; formal analysis, X.C.; investigation, Z.L., and Z.Z.; writing—original draft prepartion, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L.; supervision, C.W.; funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Scientific and Technology Development Project of Jilin Province, China (Grant No. YDZJ202501ZYTS326).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ke, J.Q.; Zhang, Y.F.; Wen, Z.P.; Huang, S.; Ye, M.H.; Tang, Y.C.; Liu, X.Q.; Li, C.C. Designing strategies of advanced electrode materials for high-rate rechargeable batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 4428–4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Wang, S.Z.; Sha, S.Y.; Lv, S.Y.; Wang, G.D.; Wang, B.F.; Li, Q.B.; Yu, J.X.; Xu, X.G.; Zhang, L. Novel semiconductor materials for advanced supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 4288–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ren, J.N.; Sridhar, D.; Xu, B.B.; Algadi, H.; El-Bahy, Z.M.; Ma, Y.; Li, T.X.; Guo, Z.H. Progress of layered double hydroxide-based materials for supercapacitors. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 1520–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.H.; Feng, X.Q.; Wang, S.R.; Wu, Q.K.; Lv, S.S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.Z. Facile synthesis of hexagonal α-Co(OH)2 nanosheets and their superior activity in the selective reduction of nitro compounds. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 18061–18068. [Google Scholar]

- Arishi, M. Morphologically engineered mixed metal oxides on carbon fibers as a binder-free electrode for diffusion capacitance-dominated hybrid supercapacitors. Rare Metals 2025, 44, 8548–8564. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.L.; Ning, S.L.; Xu, J.C.; Zhu, J.M.; Yuan, Z.X.; Wu, Y.L.; Chen, J.; Xie, F.Y.; Jin, Y.S.; Wang, N.; et al. In situ electrochemical activation of Co(OH)2@Ni(OH)2 heterostructures for efficient ethanol electrooxidation reforming and innovative zinc-ethanol-air batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 5300–5312. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.H.; Li, X.L.; Li, Q.W.; Lv, K.; Liu, J.S.; Hang, X.K.; Bayaguud, A. Mechanism research progress on transition metal compound electrode materials for supercapacitors. Rare Metals 2024, 43, 4076–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markhabayeva, A.A.; Anarova, A.S.; Abdullin, K.A.; Kalkozova, Z.K.; Tulegenova, A.T.; Nuraje, N. A hybrid supercapacitor from nickel cobalt sulfide and activated carbon for energy storage application. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 2024, 18, 2300211. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Cai, B.; Gu, H.; Xu, R.X.; Sun, Y.X.; Zhou, J.W.; Yu, F. Growing magnetic NiCo-LDH nanosheets on the Ni@CoSe2 surface to enhance energy storage capacity in asymmetric supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 1671–1682. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Ye, W.; Yang, P.; Song, J.; Shi, X.; Zheng, H. Manganese doping to boost the capacitance performance of hierarchical Co9S8@Co(OH)2 nanosheet arrays. Green Energy Environ. 2022, 7, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.W.; Han, L.; Yang, S.; Liu, Z.L.; Liu, M.; Li, B. Nanosheet-structured ZnCo-LDH microsphere as active material for rechargeable zinc batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 659, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.Y.; Wang, H.W.; Li, D.B.; Hong, X.D.; Wang, X.L. Electrochemical activation of Zn-doped NiCoO for improving the electrochemical performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1026, 180500. [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav, S.L.; Jadhav, A.L.; Mandlekar, B.K.; Sarawade, P.B.; Kadam, A.V. Influence of deposition current and different electrolytes on charge storage performance of Co3O4 electrode material. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2023, 180, 111422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.D.; He, J.H.; Duan, C.X.; Wang, G.J.; Liang, B. Recent advance in electrochemically activated supercapacitors: Activation mechanisms, electrode materials and prospects. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2025, 209, 115134. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.C.; Song, X.Z.; Hao, Y.C.; Feng, Z.F.; Hu, R.Y.; Wang, X.F.; Meng, Y.L.; Tan, Z.Q. In situ growth and electrochemical activation of copper-based nickel-cobalt hydroxide for high-performance energy storage devices. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 9460–9469. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, C.Y.; He, J.H.; Wang, G.J.; Hong, X.D.; Liang, B. Electrochemical activation of NiCo-hydroxysulfides in high-concentration KOH for constructing ultra-high capacitance electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 463, 142815. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.H.; Deng, C.Y.; Wang, G.J.; Duan, C.X.; Hong, X.D.; Liang, B. Charge/discharge activation of CoS/NiMn-hydroxide composite for enhancing the electrochemical performance. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 38585–38592. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.W.; Wu, W.L.; Zhao, C.H.; Liu, T.T.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.F. Rational design of 2D/1D ZnCo-LDH hierarchical structure with high rate performance as advanced symmetric supercapacitors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 602, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dai, M.Z.; Zhao, D.P.; Liu, H.Q.; Zhu, X.F.; Wu, X.; Wang, B. Nanohybridization of Ni-Co-S Nanosheets with ZnCo2O4 Nanowires as Supercapacitor Electrodes with Long Cycling Stabilities. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 2637–2643. [Google Scholar]

- Vahedizadeh, F.; Moraveji, S.; Fotouhi, L.; Zirak, M.; Shahrokhian, S. Hierarchical core@shell ZnCo LDH@NiS2 on nickel foam for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2024, 94, 112460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.Y.; Du, C.C.; Yang, H.K.; Huang, J.L.; Zhang, X.H.; Chen, J.H. NiCoP@CoS tree-like core-shell nanoarrays on nickel foam as battery-type electrodes for supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 421, 127871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuratha, K.S.; Su, Y.Z.; Wang, P.J.; Hasin, P.; Wu, J.H.; Hsieh, C.K.; Chang, J.K.; Lin, J.Y. Free-standing 3D core-shell architecture of Ni3S2@NiCoP as an efficient cathode material for hybrid supercapacitors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 625, 565–575. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, Y.; Jiang, T.T.; Dai, Y.M.; Wu, X.F.; Lv, X.F.; Chen, M.T.; Ye, T.W.; Wu, Q. 3D network structure of Co(OH)2 nanoflakes/Ag dendrites via a one-step electrodeposition for high-performance supercapacitors. Mater. Res. Bull. 2023, 157, 112013. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Wan, J.N.; Liu, G.L.; Suo, H.; Zhao, C. Design and construction of hierarchical α-Co(OH)2-coated ultra-thin ZnO flower nanostructures on nickel foam for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 838, 155556. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; Dai, X.Q.; Jin, J.; Tie, N.; Dai, Y.T. Hierarchical core-shell hollow CoMoS4@Ni-Co-S nanotubes hybrid arrays as advanced electrode material for supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 331, 135459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; You, J.H.; Zhao, Y.; Bao, W.T. Core-shell CuO@NiCoMn-LDH supported by copper foam for high-performance supercapacitors. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 3314–3322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.L.; He, X.; He, D.; Cui, B.Y.; Zhu, L.; Suo, H.; Zhao, C. Construction of CuO@Ni-Fe layered double hydroxide hierarchical core-shell nanorod arrays on copper foam for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 2080–2088. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Z.C.; Fan, J.C.; Huang, T.; Hu, R.S.; Fang, Y.F.; Liu, H.O.; Luo, W.B.; Chao, Z.S. Asymmetric supercapacitors based on Co9S8–ZnCo-layered double hydroxide nanocomposite electrodes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 21617–21627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Zhang, H.L.; Peng, X.; Shao, X.; Chai, Y.F.; Ma, M.; Li, Z.L.; Liu, S.D.; Ding, B. Heterostructure engineering of transition metal dichalcogenides for high-performance supercapacitors. Rare Metals 2025, 44, 8198–8236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Peng, C.; Zhou, Q.L.; Liu, Z. Electrocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production: Advances, challenges and future perspectives. Chem. Rec. 2025, 25, e202500066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Zuo, H.C.; Wang, H.; Chen, S. Rapid room-temperature synthesis of porous sulfur-doped nickel-chromium-layered double hydroxide for oxygen evolution catalysis in seawater splitting. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2023, 18, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.N.; Wu, X.Y.; Xu, Y.H.; Cao, Y.Y.; Luo, Y.Y.; Yang, H.J.; Wang, J.J.; Li, W.B.; Li, X.F. Modulating electronic and interface structure of CuO/CoNi-LDH via electrochemical activation for high areal-performance supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2024, 83, 110426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Cen, M.X.; Guo, Y.B.; Wang, B.Y.; Tian, Y.; Song, Z.L.; Peng, X.S.; Lian, J.B.; Ng, D.H.L. Highly sulfur-doped porous carbon enhances sodium-ion storage with superior rate capability and long cycling stability. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 19883–19895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.M.; Chang, L.H.; Chen, B.M.; Huang, H.; Guo, Z.C. Electrochemistry behavior and corrosion resistance of Al-Mn alloy prepared by recovering 1070-Al and Al-Mn alloys in ZnSO4 solutions. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2023, 18, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Zhong, X.H.; Wang, F.L.; Huang, Z.H.; Hong, Z.; Gao, Y.F.; Wang, H.D.; Ren, J.W.; Peng, S.J.; Li, L. Convenient room-temperature synthesis of sulfur and nitrogen co-doped NiCo-LDH coupled with CNTs on NiCo foam as battery-type electrode for high performance hybrid supercapacitor. Rare Metals 2024, 43, 4286–4301. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, S.; Shang, W.S.; Chi, Y.D.; Wang, H.; Chu, X.F.; Geng, P.Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Cheng, Z.F.; Yang, X.T. Hierarchical Design of Co(OH)2/Ni3S2 Heterostructure on Nickel Foam for Energy Storage. Processes 2022, 10, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Chi, R.T.; Liu, R.; Shi, Y.J.; Zhang, Z.X.; Che, H.W.; Wang, G.S.; Mu, J.B.; Wang, Y.M.; Zhang, X.R. Se-doped nickel-cobalt sulfide nanotube arrays with 3D networks for high-performance hybrid supercapacitor. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 30536–30545. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Ouyang, J.; Zhou, C.; Luo, Y. Sophora-like nickel–cobalt sulfide and carbon nanotube composites in carbonized wood slice electrodes for all-solid-state supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 7400–7407. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, M.H.; Zeng, W.L.; Quan, H.Y.; Cui, J.M.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, D.Z. Low-crystalline Ni/Co-oxyhydroxides nanoarrays on carbon cloth with high mass loading and hierarchical structure as cathode for supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 357, 136886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Shi, X.-R.; Sun, C.; Zhang, X.; Huang, M.; Liu, R.; Wang, H.; Xu, S. Template-controlled in-situ growing of NiCo-MOF nanosheets on Ni foam with mixed linkers for high performance asymmetric supercapacitors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 572, 151344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F.; Min, S. Monolithic porous carbon membrane-based hybrid electrodes with ultrahigh mass loading carbon-encapsulated Co nanoparticles for high-performance supercapacitors. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.