Abstract

During continuous casting, coated slag is applied to molten steel to enhance heat transfer and lubrication. In this study, a numerical calculation model was built to reveal the flowing characteristic of slag according to the fundamental principles of heat transfer and viscous fluid mechanics. The flow and heat transfer behaviour of protective slag on the surface of molten steel and the flow velocity of liquid slag in slag channel gaps were calculated and analyzed. The streaming and thermal conduction situation of slag on the surface of molten steel, as well as the flow velocity of liquid flux in the slag passage gap, were calculated and analyzed. The results showed that as the thickness of the liquidus slag film increased from 10 to 12 mm, the thermal flux density at the top of the flux film layer decreased from 0.1059 to 0.0882 MW/m2. The heat flux density increased rapidly within 0.1 m of the narrow side of the mould, reaching a peak value of 2.27 MW/m2. As the viscosity temperature factor of the flux increased from 0.45 to 2.05, the maximum floating speed of the liquid film from the water inlet to the narrow side in the centre district of the mould decreased from 0.0316 to 0.028 m/s, representing a reduction of approximately 11.4%. This study can provide a reference for the design and improvement of protective slag.

1. Introduction

Protective slag is a crucial auxiliary material in continuous casting production. It covers the molten steel and is composed of three components: base material, solvent, and carbonaceous material. During the production process, the protection of molten steel from the intermediate ladle to the mould is ensured by the continuous addition of immersion nozzles and flux. The distribution of flux directly affects the friction and thermal diffusion of the cast billet. During production, it is essential that the liquid film supply above the molten steel’s appearance is adequate to ensure continuous and uniform flow into the slag passage gap between the mould and the slab. Insufficient slag distribution can lead to increased friction between the casting billet and the mould, unstable heat transfer, and various surface defects on the casting billet. It is necessary to have a comprehensive understanding of the thermal and flow characteristics of protective slag [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Many researchers have conducted research on protective slag. Delhalle et al. developed a one-dimensional unsteady numerical model to reveal the thermal behaviour of protective slag. They investigated the effects of melting temperature, consumption, and the effective heat conductivity of liquid slag on the thickness of the slag layer [11]. Yang et al. built a mathematical model for the heat transfer of protective slag in round castings. They calculated the thermal field across the protective slag, casting billet, and mould and analyzed the influence of the casting process and the thermal properties of protective slag on the temperature distribution of the slag above the meniscus. The calculation results were visualized and displayed using the VC platform and OpenGL technology [12]. Ramirez-Lopez et al. employed the computational fluid dynamics software FLUENT 16.0 to develop a 2D model that describes the stream and thermal characteristics of molten steel and protective flux. They calculated the relationship between the thickness of the liquidus and solidus films in the gap between the mould and the casting billet over time. They simultaneously analyzed the instantaneous flowing of liquid flux near the meniscus district and the periodic variation of shell pressure during a vibration cycle. The results revealed that flux consumption was primarily dependent on the thickness of the liquidus flux film, with the slag consumption process predominantly occurring within the negative slip time range. However, the model was relatively complex, with a simulation calculation time of up to 120 h for a single vibration cycle [13,14]. Toshiyuki et al. developed a simplified experimental simulation device, using silicone oil in place of flux to replicate the behaviour of flux flowing into the channel under the influence of mould vibration and pulling speed. They observed that the flux consumption mainly occurred during the late stage of the plus sliding state and within the range of negative sliding time. The researchers also investigated the relationship between slag consumption and variation in pulling velocity, shake frequency, and the viscosity of the flux [15,16]. Jin et al. added lithium dioxide to the protective slag in order to avoid the longitudinal cracks and defects. The industrial trial showed that the longitudinal cracks were decreased by using this protective slag [17]. Yang et al. built a fluent model which considered four-phase flow during the continuous casting process. The performance of bubbles caused by the injected argon was investigated using the Lagrangian algorithm. The detailed results of bubble distribution, flow field, and meniscus fluctuation were exhibited [18].

However, most studies have treated the density of the protective slag as constant, without considering the impact of liquid slag convection. Consequently, the understanding of the flow characteristics of protective slag in the slag passage gap remains insufficient. In a previous work, the influence of casting speed on slag consumption was discussed, and the transient flow velocity of protective slag and molten steel at each moment of the vibration cycle was analyzed [19,20]. In this article, a two-dimensional longitudinal section numerical model is developed to reveal the flowing and thermal characteristics of protective slag above the liquid steel, taking into account the impact of temperature on the protective slag. The article also provides a detailed analysis of the flow characteristics of protective slag in the slag passage.

2. Model

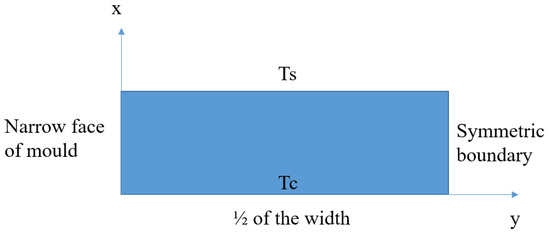

A curved billet continuous caster from a specific steel enterprise is utilized in this experiment. The primary process parameters for the slab continuous casting are detailed in Table 1. The software is FLUENT. To ensure symmetry, the calculation area in this study is 900 mm in length. The boundaries of the calculated district are defined by the narrow side and the centre district of the mould, each representing half the width of the slab, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Main parameters of the slab caster.

Figure 1.

Schematic of model.

The N-S formula and energy formula were solved in order to obtain the flow and thermal results of the slag. In this work, the flow of liquid slag is regarded as incompressible. The main formulas are as follows:

- (1)

- Continuity formula [21,22]:

- (2)

- Momentum formula [21,22]:

- (3)

- Energy formula [21,22]:

The boundary conditions are as follows:

- (1)

- The upper surface is set to no slip boundary.

- (2)

- The interface temperature at the bottom is set to the pouring temperature of the molten steel.

- (3)

- The right boundary is set as a symmetrical boundary.

- (4)

- The temperature of the slag liquid on the left boundary is set as a function of the thickness of the slag layer.

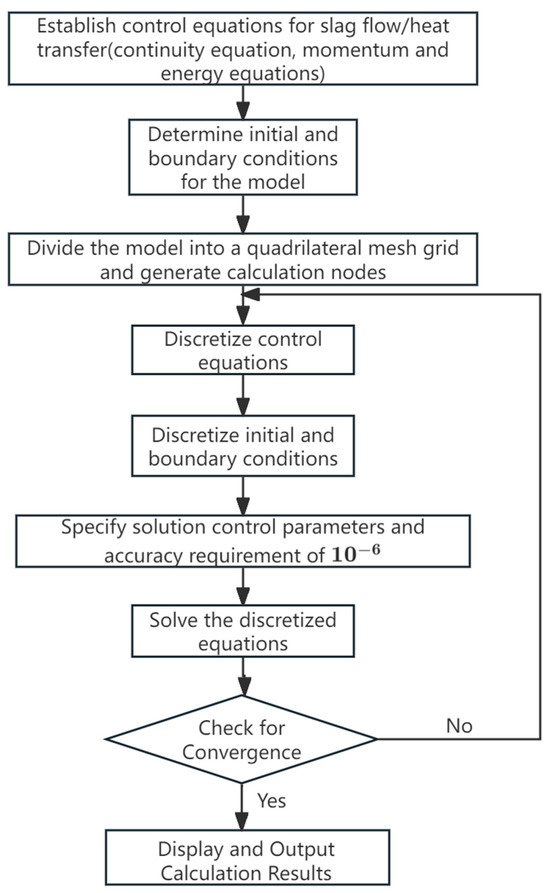

The calculation diagram is shown in Figure 2. The main process parameters, such as specific heat, effective thermal conductivity, thermal expansion coefficient, and so on, are shown in Table 2 [4,21].

Figure 2.

Calculation process of the model.

Table 2.

Process and property parameters.

The mesh independence is listed in Table 3. When the mesh number exceeds 421,334, the deviation of density of thermal flux is very small, and it can be considered that the mesh number is appropriate.

Table 3.

Mesh independence analysis.

3. Results

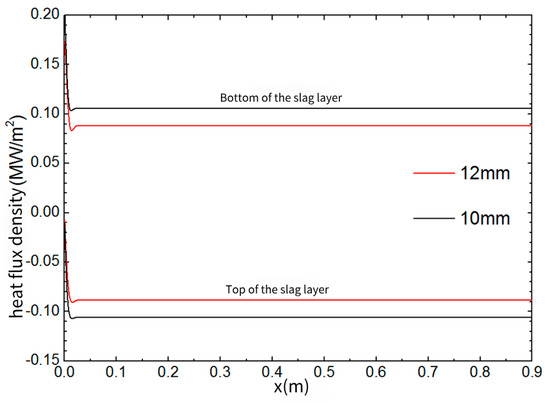

3.1. Influence of Slag Layer Thickness on Heat Flow

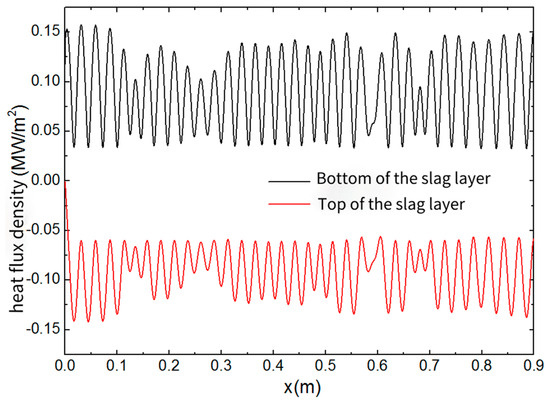

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the density of thermal flux at the top and base of the protect slag for various slag film thicknesses. The direction of density of thermal flux is opposite to that of the temperature gradient in the calculation area. Consequently, the density of thermal flux at the top of the slag film is negative, while it is positive at the base. Generally, with the liquid film increases, the heat flux density decreases. For instance, the liquid film thickness increases from 10 mm to 12 mm, and the heat flux density at the top of the layer decreases from 0.1059 MW/m2 to 0.0882 MW/m2. However, when the thickness reaches 15 mm (Figure 4), natural convection within the slag film intensifies, making heat convection the predominant mode of thermal delivery in the slag layer. The maximum heat flux density at the top of the slag layer reaches 0.15 MW/m2. This peak corresponds to the upward flow of high-temperature, low-density protective slag at the bottom. The valley corresponds to the downward flow of lower-temperature, higher-density protective slag at the top. According to these results, controlling the thickness of the protective slag within a reasonable range is crucial. The intensification of natural convection is not helpful to the stabilization of the protective slag layer.

Figure 3.

Heat flux on the top and bottom of the flux layer with thicknesses of 12 and 10 mm.

Figure 4.

Heat flux on the top and bottom of the slag layer with thickness of 15 mm.

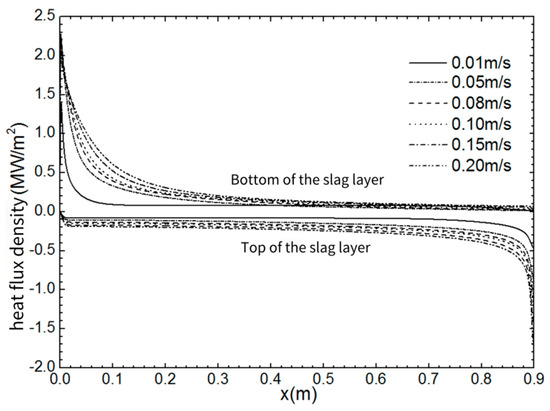

3.2. Influence of Bottom Shearing Speed on the Interface Heat Flux

At a low flow speed at the reflux district of the liquidus steel, a relatively calm liquid surface can not provide enough thermal energy to the slag, which affects the melting and replenishment of protective slag. A high speed in the reflux district of the molten steel can undermine the stable boundary of the steel and slag, potentially causing slag rolling and negatively impacting the quality of the casting slab. Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between the thermal flow density at the base and top of the liquid slag and the bottom shear velocity. Considering that the direction of thermal flow density is opposite to that of the temperature gradient in the calculation area, the thermal flow density at the top of the slag layer is negative, while the thermal flow density at the bottom is positive. The interfacial thermal flow density between the steel and slag remains stable when the measurement point is distant from the narrow surface of the mould. However, owing to intense convective heat transfer near the narrow surface and the water inlet, the heat flux density increases rapidly within 0.1 m of the narrow surface, reaching a maximum of 2.27 MW/m2. The interfacial thermal flow density between the powder slag and liquidus slag begins at 0.08 m from the water outlet, with a maximum heat flux density of 1.79 MW/m2. This increase in bottom shear velocity considerably enhances both heat conduction and convection within the slag layer, leading to a higher interfacial heat flux density, which aligns with practical data from the continuous casting process.

Figure 5.

Heat flux distribution on the flux layer interface.

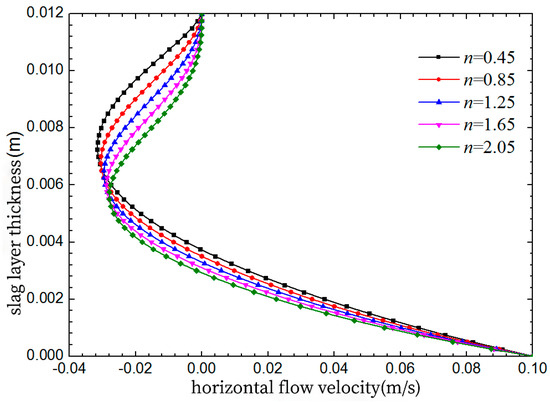

3.3. Influence of Viscosity Temperature Coefficient on Horizontal Flow Velocity

The temperature coefficient (n) of protective slag viscosity indicates the dependence of the protective slag viscosity on temperature. A larger n value signifies a greater sensitivity of viscosity to temperature changes, whereas a smaller value indicates less sensitivity. The viscosity distribution of protective slag directly influences the roll and thermal conductivity of the liquidus slag, thereby affecting the structure of the slag level above the liquid steel. The viscosity temperature coefficient reflects changes in the protective slag’s viscosity and is typically determined using empirical methods. This article explores the influence of changes in the viscosity temperature coefficient on the flow velocity and temperature distribution of slag.

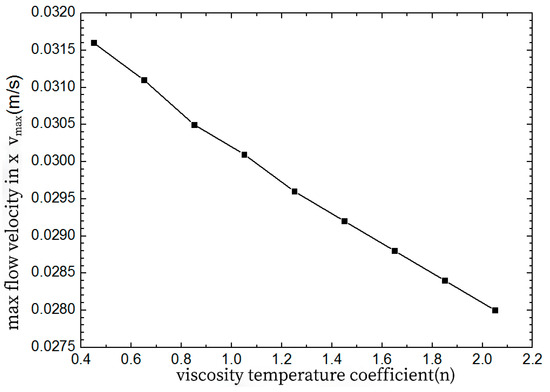

As seen in Figure 6, within the central area of the model, 450 mm from the centre of the nozzle, the horizontal flow speed of the liquid layer in the thickness direction decreases as the viscosity temperature coefficient of the protective slag increases. Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between the peak flow speed of the protective slag, flowing from the water inlet to the narrow side, and the viscosity temperature coefficient. As the viscosity temperature coefficient of the protective slag increases from 0.45 to 2.05, the peak flow speed decreases from 0.0316 to 0.028 m/s, representing a reduction of approximately 11.4%.

Figure 6.

Effect of the exponent for temperature dependence of viscosity on horizontal velocity.

Figure 7.

Maximum horizontal velocity from submerged entry nozzle to narrow surface as a function of the exponent for temperature dependence of viscosity.

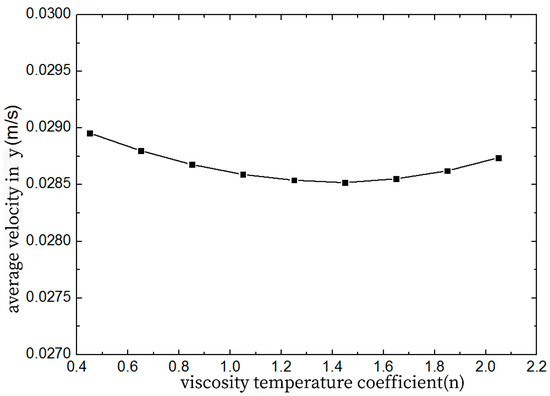

3.4. Influence of Viscosity Temperature Coefficient on Longitudinal Flow Velocity

As shown in Figure 8, at the water outlet, as the viscosity temperature coefficient increases, the average change in the vertical flow speed of the liquid film along the thickness direction is approximately 0.1%. The thermal convection of the liquid film near the submersed nozzle is strong, resulting in a local high temperature zone for the liquid slag and a broad range of high-temperature areas. The viscosity temperature coefficient has a minimal impact on the roll and thermal conductivity of the protective slag in the water outlet area.

Figure 8.

Average vertical velocity as a function of exponent for temperature dependence of viscosity.

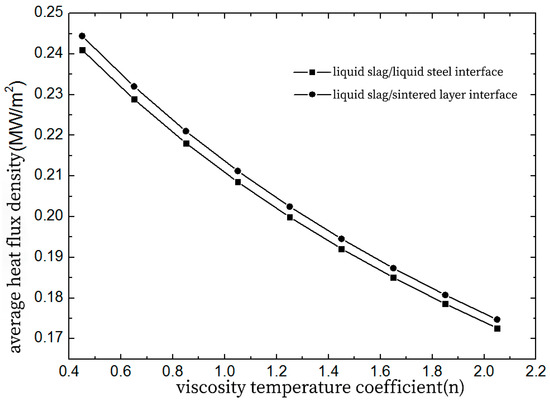

3.5. Influence of Viscosity Temperature Coefficient on Interface Thermal Flow Density

The average value of thermal flow density at the junction of the steel and liquid slag and the junction of the sintering layer and liquid slag varies with the viscosity temperature coefficient of the protective slag (Figure 9). As n increases, the average thermal flow density at the molten steel/liquidus film junction decreases from 0.241 MW/m2 to 0.173 MW/m2, representing a reduction of ~28.2%. The average thermal flow density at the liquid slag/sintering layer decreases from 0.244 MW/m2 to 0.175 MW/m2, a reduction of approximately 28.3%. This indicates that a higher n value increases the sensitivity of viscosity to temperature changes in the slag layer, resulting in lower circulation velocity and thermal conductive rate of the liquidus film. The results are consistent with those of Neelakantnan, Mcdavid, and Macias [4,21,22].

Figure 9.

Average surface thermal flow varies with the temperature dependence of viscosity.

4. Conclusions

According to the model, the flow and thermal conductive characteristics of protective slag above the liquidus steel and the flow speed of liquid film in slag passage gaps are determined. The conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- As the thickness of the liquid flux film increases from 10 to 12 mm, the heat flux density at the top of the slag layer decreases from 0.1059 to 0.0882 MW/m2. However, when the thickness reaches 15 mm, natural convection within the film intensifies, making thermal convection the dominant mode. At this thickness, the peak thermal flow density at the top of the film reaches 0.15 MW/m2.

- (2)

- Owing to strong convective heat transfer near the narrow surface and the water inlet, the heat flux density increases rapidly within 0.1 m of the narrow side, reaching a peak value of 2.27 MW/m2. The interface thermal flow density between the powder slag film and liquid slag film begins at 0.08 m from the immersed nozzle, with a maximum heat flux density of 1.79 MW/m2.

- (3)

- As the factor of viscosity temperature of the slag increases from 0.45 to 2.05, the peak flow speed of the liquid film from the immersed nozzle to the narrow side in the centre district of the mould decreases from 0.0316 to 0.028 m/s, representing a reduction of approximately 11.4%. This reduction in flow velocity within the slag layer weakens both convection and heat conduction, leading to a decrease in the interfacial thermal flow density. Additionally, the high-temperature area of the slag film near the water outlet remains relatively wide, causing only minimal changes in the longitudinal flow of the protective slag.

Author Contributions

Data curation, S.W. and F.D.; writing—original draft, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Shanjiao Wang was employed by the company Nanjing Ericsson Panda Communications Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Meng, Y.A.; Thomas, B.G. Modeling transient slag-layer phenomena in the shell/mold gap in continuous casting of steel. MMTB 2003, 34, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furumai, K.; Aramaki, N.; Oikawa, K. Influence of heat flux different between wide and narrow face in continuous casting mould on unevenness of hypo-peritectic steel solidification at off-corner. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2022, 49, 845–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.N.; Wen, G.H.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Yu, L. Effect of Microstructure on the Granule Strength of Hollow Granulated Mold Fluxes for Continuous Casting. Steel Res. Int. 2023, 94, 2200480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelakantan, V.N.; Sridhar, S.; Mills, K.C.; Sichen, D. Mathematical model to simulate the temperature and composition distribution inside the flux layer of a continuous casting mould. Scand. J. Metall. 2002, 31, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pei, Q.W.; Han, Z.F.; Wang, E.A.; Wang, J.Y.; Karcher, C. Modeling study of EMBr effects on molten steel flow, heat transfer and solidification in a continuous casting mold. Metall. Res. Technol. 2023, 120, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.H.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, X.Z. Study on the consumption mechanism and lubrication of mold powder based on non-sinusoidal oscillation mode. Metals 2024, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.J.; Wang, X.D.; Yao, M. Simulation study on transient periodic heat transfer behavior of meniscus in continuous casting mold. MMTB 2023, 54, 3164–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, S.T.; He, S.P.; Zhang, X.B.; Wang, Q.Q. A 3D mathematical modeling on meniscus solidification and heat transfer in continuous casting chamfered mold of slab. Steel Res. Int. 2023, 94, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.J.; Luo, S.; Wang, W.L.; Zhu, M.Y. Modelling of meniscus behavior and slag consumption during initial casting stage of continuous casting process. Metal. Mater. Int. 2024, 30, 2183–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.H.; Yu, B.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, X.Z. A mathematical mould model for transient infiltration and lubrication behaviour of slag in a steel continuous casting process. J. South. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2024, 30, 2183–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhalle, A.; Larrecq, M. Mould Powders for Continuous Casting and Bottom Pour Teeming. Warrendale, PA, USA, 1986; pp. 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.M. Research on Heat Transfer Calculation and Visualization of Continuous Casting Round Billet Protective Slag. Master’s Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Lopez, P.E.; Lee, P.D.; Mills, K.C. Explicit modelling of slag infiltration and shell formation during mould oscillation in continuous casting. ISIJ Int. 2010, 50, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Lopez, P.E.; Lee, P.D.; Mills, K.C. A new approach for modelling slag infiltration and solidification in a continuous casting mould. ISIJ Int. 2010, 50, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajitani, T.; Okazawa, K.; Yamada, W. Cold model experiment on infiltration of mould flux in continuous casting of steel: Simple analysis neglecting mould oscillation. Trans. Iron Steel Inst. Jpn. 2006, 46, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kajitani, T.; Okazawa, K.; Yamada, W. Cold model experiment on infiltration of mould flux in continuous casting of steel: Simulation of mould oscillation. ISIJ Int. 2006, 46, 1432–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jin, H.B.; Tu, L.F.; Zhang, X.B.; Wang, Q.Q. Optimization of mold slag for continuous casting of peritectic steel. Steel Res. Int. 2023, 94, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.D.; He, P.; Chang, L.Y.; Li, T.S.; Bai, X.T.; Luo, Z.G.; Zhao, N.N.; Liu, Q.K. Numerical analysis of slag-steel-air four-phase flow in steel continuous casting model using CFD-DBM-VOF model. Metals 2024, 13, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.M.; Zeng, Y.B.; Wang, S.J.; Zheng, G.T. Analysis of Flow and Fluctuation Characteristics in Coated Slag Using a 2D Model in the Meniscus Region of Mold. Coatings 2023, 13, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.M.; Wang, S.J.; Zheng, G.T. Flow and influencing factors of coated slag in continuous casting mold. Coatings 2023, 13, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdavid, R.M.; Thomas, B.G. Flow and thermal behavior of the top surface flux/powder layers in continuous casting molds. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 1996, 27, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, E.; Castillejos, A.H.; Acosta, F.A.; Herrera, M.; Neumann, F. Modelling molten flux layer thickness profiles in compact strip process moulds for continuous thin slab casting. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2002, 29, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).