Abstract

Lubricants are substances that reduce friction and heat dissipation between operating machine parts. The purpose of the paper is to investigate the possibility of improving the tribological properties of biodegradable vegetable oils. The objects of the research were lubricating oils produced based on selected plant oils (rapeseed, sunflower, corn, soybean) and Priolube ester oil containing nanoparticle hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) and a dispersant. The research assesses the physicochemical properties, the wear load limit, the welding load, and the friction coefficient of the prepared oil compositions. The article compares the results with those obtained during the CB30 engine and PAO4 oil tests. The test results confirm that lubricating oils prepared in this way are characterized by promising tribological properties, are easy to prepare, and are environmentally friendly. The appropriate method of preparation has a significant impact on the quality of the obtained oils.

1. Introduction

The primary use of lubricants is to reduce the friction of interacting machine parts. With its practical applications, this research aims to make this reduction more efficient and environmentally friendly. Friction is most often an undesirable phenomenon and is responsible for reducing the operating capabilities of machines. As a result of friction, released heat may accelerate the destruction of the tribological node. In addition to reducing friction, lubricants should guarantee good heat dissipation from the tribological node, prevent noise, deformation, and damage to mating surfaces, and play a vital role in the transport of foreign particles. Therefore, lubricants are used in machines, cars, and various mechanisms; 37.3 million tons of lubricants were exploited worldwide in 1999 [1]. In the automotive and industrial sectors, liquid and solid lubricants are mainly used, although lubricants that contain various gases may also be utilized.

Lubricants are not homogeneous substances; they consist of a base oil enriched with various additives that give the oil the required properties. Manufacturers often choose a single oil as the lubricant base, although a mixture of oils may also be used. A good lubricant is characterized by the following properties: a wide temperature range within which it remains fluid, a high viscosity index, thermal and hydraulic stability, demulsibility, reduced risk of corrosion, and high oxidation resistance.

1.1. Biodegradability of Lubricants

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) defines biodegradability via three basic terms relating to three concepts: readily biodegradable, ultimately biodegradable, and inherently biodegradable [2,3]. A substance is readily biodegradable when, during tests, it is fast and is ultimately biodegraded in an aquatic environment under aerobic conditions [4]. A material is ultimately biodegradable (aerobic) when utilized entirely by microorganisms [4]. However, a substance is inherently biodegradable if it shows natural, primary biodegradation, and if it shows biodegradation above 20% of the theoretical value. A substance is inherently biodegradable if it shows biodegradation above 70% of the theoretical value [5].

According to Acumen Research and Consulting (ARC) analyzes and forecasts [6], the global market for biodegradable lubricants is growing constantly and in 2022 it will reach USD 2.8 billion, and the forecast predicts growth of 5.2% in 2023–2022. Moreover, ARC believes that there are growing concerns about the gradual destruction of the natural environment through the use of petroleum products that are not biodegradable, and so more and more people are considering using lubricants, the use of which reduces the amount of pollution and the risk of harmful effects on human health and adds to the protection of the natural environment.

1.2. Biolubricants

Lubricants based on vegetable oils or animal fats are called biolubricants. Animal fats can be exploited; however, it is more advantageous, at least for ecological reasons, to use plant materials, and the most common are rapeseed, castor, palm, sunflower, and tall oil. Hydrolyzing vegetable oils produce acids that are combined to create specialized synthetic esters. Additionally, lubricant producers can use lanolin, a lubricant derived from wool [7].

Currently, the biolubricants market constitutes a small part of the lubricant market; 840,000 tons of lubricants were sold in Great Britain in 2008, and only 1% were biolubricants [8]. Other oils from plants were also tested. In 2020, Australian researchers tested the lubricating properties of safflower oil, finding that oil-lubricated internal combustion engines achieved better performance and lower exhaust emissions compared to petroleum-based lubricants in lawnmowers, chain saws and other agricultural equipment. Lee (2020) [9] applied a gene silencing method, redesigned a new type of saffron, which produces up to 93% oil.

Automobile lubricants are disposed of, but unfortunately they cause leaks caused by poor car conditions, accidents, and other losses; therefore, approximately 50% of lubricants pollute the environment [10]. Unlike biolubricants, most mineral lubricants are highly toxic and have low biodegradability, whereas biolubricants’ good biodegradable properties eliminate problems with hydrolysis, oxidation, and poor efficiency at low temperatures. The growing biolubricants market is also influenced by changing legal regulations that specify requirements for oils available for sale [10].

1.3. Lubricants in Mechanical Structures

The increasing intensity and time required for the use of technical devices require the use of increasingly efficient and durable lubricants. Research on reducing the wear of friction surfaces of machine and device elements by using various lubricants is carried out often; for example, attempts have been made to develop a simple abrasive wear model [11,12] and an adhesive wear model [13,14,15].

Introducing additives (e.g., layered materials) to the oil can positively influence the lubricating properties mentioned above. Currently, many additives have been tested and added to the oil to cause friction reduction: molybdenum disulfide (), [16], tungsten disulfide (), hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), [17,18,19], and graphite (C), [20,21,22,23].

Several studies have confirmed that the tribological properties of lubricating oils are improved after adding layered materials to them. This is because the sliding of layers connected by weak Van der Waals forces, built of atoms strongly connected by covalent bonds, is facilitated [24,25,26].

Additives (layered materials) can be introduced into the material from which the surfaces of friction elements are made by sintering or applying them to the friction surfaces. Another method is to place the layered material in specific points, for example, in specially prepared pockets on the friction surfaces or by laser sputtering. These methods allow for the economical use of layered materials, but the applied technology is not simple [12,26,27]. The simplest method is to add them to the lubricating oil with which they will enter the tribological node. The size of the additive particles is vital in this respect; they should be as small as possible, and such expectations can be met by modern layered nanomaterials, thus guaranteeing an improvement in the lubricating properties of oils. Important factors determining their selection are resistance to high temperature [12,15,28], reactivity, and harm to health [29].

Due to the specificity of the lubricating oil production process, the simplest method is to add layered materials to it during its production [30]. This process does not require a very high temperature, so it preserves the properties of layered materials. However, because of the plate-like shape of the layered materials, it is not easy to obtain a stable mixture with lubricating oils without distinct segmentation. Layered materials with a smaller particle diameter behave slightly better. Small particles also flow better through filters that retain contaminants and better fill the roughness of friction surfaces or spaces between system elements [31].

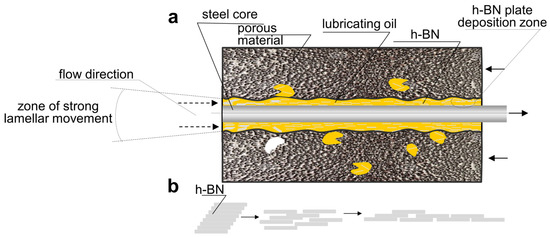

Figure 1 shows the lamellar lubrication mechanism based on the use of anisotropic layered materials (a), such as h-BN. The characteristic of layered materials is their inhomogeneous system of bonds in the molecule. Strong covalent bonds create hexagonal layers connected by weak van der Waals bonds. The transverse forces acting on the h-BN molecule during the bearing operation smoothly move the individual layers relative to each other, thus creating favorable conditions for sliding layer on layer (b), guaranteeing good lubricating properties.

Figure 1.

Lamellar lubrication model, (a) bearing model, (b) lamellar sliding mechanism of h-BN layers.

Additionally, it was found that, when using layered materials in oils, smaller particles allow better anti-seize properties [32,33]. Among many layered materials, h-BN deserves special attention because it is relatively inexpensive and easily available, safe for health, does not react with other substances and does not change its properties and structure at high temperatures [12,15]. Although the often used layered agents WS2 and MoS2 guarantee a slightly lower friction coefficient than h-BN, they are not indifferent to health. In most previous studies, researchers examined the h-BN addition with relatively large particles. The comparison of the tribological properties of oils with the addition of h-BN of different particle sizes was carried out in 2018 [32]. At that time, Urbaniak et al. researched oil containing h-BN with a particle size of 70 nm using different amounts and different amounts of surfactant (surface-active compound) [34]. Taking into account the results obtained, it can be concluded that adding h-BN layered nanomaterial to the lubricating oil can be a good solution to obtain a lubricating oil with ~27% greater galling load than base oil. This is possible, provided that certain conditions are met for the preparation of the lubricating oil. In the case of PAO4 base oil, succinimide in an amount not exceeding 0.5% by weight should be used as a dispersing agent for hexagonal boron nitride (70 nm at 2.5 wt%).

Hexagonal boron nitride is an inorganic chemical compound obtained by synthesis. It was first synthesized in 1842 by William H. Balmain [1]. Currently, it is obtained using high-energy methods of producing boron–nitrogen bonds. It comes in three crystallographic forms (). The variant (h-BN) has a hexagonal structure similar to graphite; it is a soft, lamellar variety of boron nitride with high anisotropy, and because of this, it can be used as a solid lubricant. It belongs to the group of materials with high chemical stability and, according to the latest research, it is harmless to health, which confirms its use as an additive to cosmetics. Because it is not a toxic substance and does not bioaccumulate, no ecological problems should be expected with its moderate use.

Due to the need to protect the environment, the possibility of using biodegradable oils, including vegetable oils, to produce lubricating oils is sought. The latest available research on soybean and sunflower oil, which is parallel to ours, confirms that using nano h-BN helps obtain a low friction coefficient [35], eliminating small surface defects and discontinuities, improves heat dissipation and, what is very important, h-BN is not destroyed even at very high temperatures [36].

As part of the pilot research program, a set of oils (corn, rapeseed, sunflower, soybean, and Priolube 3967 LQ) was prepared and hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) was introduced into these oils together with a surfactant in the appropriate amount. Then, the physicochemical and tribological properties of these oils were examined.

The research aimed to determine the impact of adding h-BN to these oils on selected tribological properties and compare the results obtained with CB30 oil intended for use in four-stroke engines at low and medium loads [34]. The purpose of the surfactant, which reduces the surface tension of the oil (proprietary or reserved substance), was to prevent the possible sticking of the h-BN particles and to obtain a more stable suspension in the oil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Testing Materials

2.1.1. Hexagonal Boron Nitride and Anticaking Agent (Surfactant)

Test samples were prepared from selected biodegradable base oils, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) with a particle size of 70 nm and a surfactant. The research used hexagonal boron nitride MK-hBN-N70 purchased from Lower Friction M.K. IMPEX CORP 6382 Lisgar Drive, Mississauga, Ontario L5N 6X1 Canada.

Succinic acid imide (succinimide) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was used to prevent caking of hexagonal boron nitride particles and to ensure longer retention of suspended particles in oil (slowing down sedimentation). The additive is a high-performance dispersing agent employed wherever needed to retain hydrocarbons or inorganic particles in an oil suspension. The specification of a succinimide was presented in [34]. It has found use in producing high-performance engine and transmission lubricants, as an agent preventing oil deposits from forming during downtimes, and as a dispersing agent aiding in keeping process equipment clean in refineries, the petrochemical industry, and the gas and coke industry.

2.1.2. Oils Used for the Preparation of Test Samples

Due to their high degree of biodegradability and availability, the following vegetable oils were selected for testing: rapeseed, sunflower, corn, soybean and, for comparison, Priolube 3967 LQ ester oil. The oils used for the study were purchased from a Silesia Oil (Łaziska Górne, Poland), i.e., rapeseed, sunflower, corn and soybean oils, all domestically produced, and Priolube 3967 LQ ester oil from CRODA Lubricants.

Tests of the physicochemical properties of oils (flash point temperature, min [°C] kinematic viscosity at 40 °C and 100 °C [mm2/s], viscosity index, pH value, surface tension [nN/m], density [g/cm3] and refractive index) were carried out in the Bioelectrochemistry Laboratory of the Faculty of Chemistry, University of Białystok.

For physicochemical tests, the following apparatuses were used:

- WTW pH meter (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA) with SenTix®41 pH electrode (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA) to determine the pH value of oils,

- Abbe refractometer (KERN Optics, Balingen, Germany) to determine the angle of refraction of light when light rays pass from air to the tested oil,

- Nima tensiometer (Nima Technology Ltd., Coventry, UK) to determine surface tension using the tensiometer method,

- An apparatus consisting of a Höppler viscosimeter (RHEOTEST, Medingen, Germany) and a thermostat (Merazet, Poznań, Poland) to test viscosity (the test itself was carried out for temperatures of 40 and 100 °C),

- Pycnometers ((Archem, Kielce, Poland) placed in a thermostat (Merazet, Poznań, Poland)) to test the oil density (measurements were made at 15 °C).

The results obtained are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specification of the tested oils.

2.1.3. Preparation of Samples for Testing

To prepare the research samples, a PS 600.R2 laboratory scale with a weighing accuracy of up to 1.5 mg (Radwag, Radom, Poland), an ultrasonic homogenizer UP200St (Hielscher Ultrasonics, Teltow, Germany) 200 W, 26 kHz with an S26d14 litanium ø14 sonotrode and a UP200St-T generator and a UP200St-G transducer with automatic frequency tuning with adjustable amplitude were used from 20 to 100% and pulse from 0 to 100%.

After the appropriate amounts of oil, h-BN (hexagonal boron nitride) and surfactant were measured, a lubricant mixture was prepared using an ultrasonic homogenizer and subjected to testing. The mixture preparation process was carried out each time before the test (mixing time 15 min, room temperature 20 °C, and humidity 55%).

The compositions of individual samples are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the compositions of the test oil mixture.

2.2. Apparatus

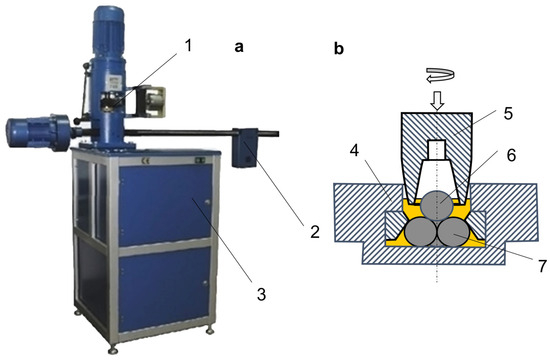

Tests of the lubricity properties of oil compositions were carried out in the laboratory of SILESIA OIL LTD using the T-02U universal four-ball apparatus (ITEE, Radom, Poland, Figure 2, Table 3). This apparatus determines the anti-seize and anti-wear properties of lubricants and building materials [37,38,39]. The average diameter of the flaw [mm], the welding load [daN], and the temperature of the friction node were determined during the tests.

Figure 2.

(a) Four-ball apparatus; (b) friction node, 1—body with ball mounting assembly, 2—loading assembly, 3—base, 4—ball seat with tested oil mixture, 5—upper ball holder, 6 —upper ball, 7 —lower balls; ball material—100CR6 steel with a diameter of 12 mm and a hardness of 59–61 HRC (Ra 0.02).

Table 3.

Specification of the T02U device.

The size of the flaw was measured with an OMO 06192/06193 optical microscope (Keyence International, Mechelen, Belgium), and photos were taken with a PENTAX K-70 camera (Ricoh Polska Sp. z o.o., Warszawa, Poland).

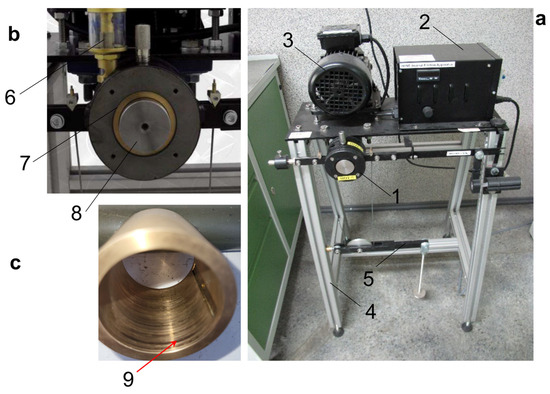

Measurements of the friction coefficient characteristic of the tested oils were performed on the HFN5/E/16/029 device manufactured by P. A. HILTON Ltd. (Andover, UK. Figure 3, Table 4). The HFN5 device is designed to determine friction by measuring the friction torque in a plain bearing under variable load, speed, and lubrication conditions.

Figure 3.

(a) HFN5/E/16/029 device, (b) test head, (c) CC481 K bronze sleeve (Ra 2.5) after testing, 1—test head 2—control unit, 3—electric motor, 4—base, 5—weight, 6—droplet oil dispenser, 7—bronze sleeve CC481K (Ra 2.5), 8—steel pin C45 (Ra 1.25), 9—friction trace.

Table 4.

Specification of the HFN5/16/029 device.

The tests were carried out using the same conditions for each type of oil, in the case of friction with light bearing lubrication at a constant rotational speed of 400 [rpm] and variable bearing load (from 55 to 135 [N]). A plain bearing made of phosphor bronze (a solid material) was used as a reference bearing.

The friction torque was recorded for various bearing load values and, based on these results, using Guillame Amonts friction law stating that the friction coefficient (μ) is a dimensionless quantity determining the relationship between the friction force () and the pressure force (), the friction coefficient was calculated using the pattern [40]:

The friction coefficient is the friction angle corresponding to the angle of inclination at which a body slides down an inclined plane with uniform motion.

In the case of the device used for testing, the sample in the form of a sliding bearing remained at rest, relating to the counter-sample. The tested oil was introduced in droplet form into the contact area between the sample and the counter-sample. The measured friction torque was used to determine the friction force which, about the step-changing pressure, allowed the determination of the characteristics of their relationship, and the tangent of the angle of inclination of the trend line (ρ) of the obtained measurement results is given by the formula:

where the value of the measured friction coefficient allows for comparison of the results obtained for individual oil mixtures.

The stability of oil suspensions was assessed based on the observation of samples placed in laboratory bottles for 14 days, and the observed changes were documented using the camera.

2.3. Test Procedures

A sample of the stable lubricant suspension obtained as a result of homogenization was placed on the head of the four-ball apparatus and, according to the PN-C-04362:2017-03 standard, its anti-wear properties (scar diameter) and lubrication properties (welding load) were determined.

After placing the test specimen in the friction node of the four-ball apparatus (10 mL of oil is drip-fed into the contact interface to cover the balls in the node), it was tested under the following conditions: ambient temperature 20 °C, rotational speed 1500 rpm, constant pressure 39.23 daN, time 3600 s. Chrome steel balls (100CR6) with a diameter of 12.7 mm ± 0.0005 mm were used in the tests. Each measurement was repeated three times, after which the diameter of the flaw on the steel balls was measured, and, on this basis, the wear load limit () was determined. Then, the permissible galling load test was performed.

Friction coefficient tests were carried out on the HFN5/E/16/029 device using the same parameters for each type of oil in friction conditions with light bearing lubrication at a constant rotational speed of 400 [rpm] and variable bearing load (from 55 to 135 N). A plain bearing made of phosphor bronze (a solid material) was used as a reference bearing. The friction torque was recorded for various bearing load values, and the friction coefficient was calculated based on these results.

3. Results and Discussion

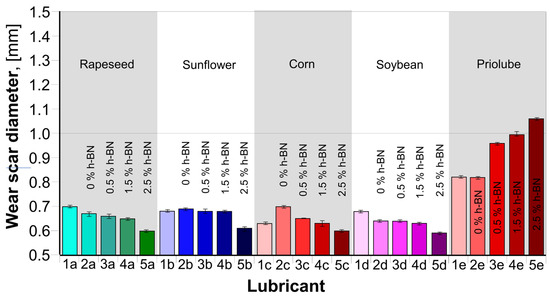

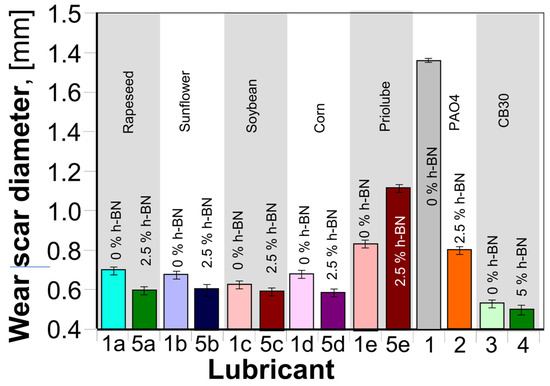

3.1. Wear Scar Measurement

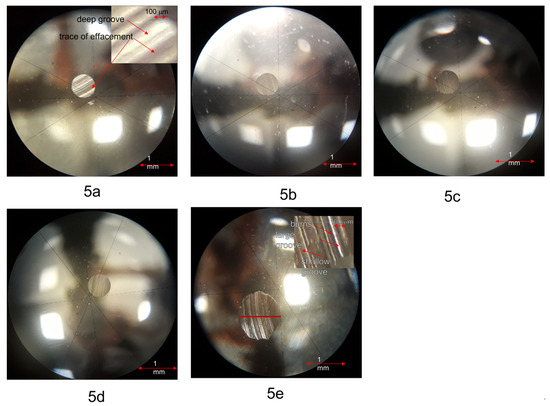

The wear area resulting from the tests was measured using a calibrated measuring microscope. This consisted of measuring the diameters three times perpendicularly, and the results of the average diameters of the wear scars are summarized in Table 5 and Figure 4, where the standard deviations of the measurements are also shown. Photos of the shape and type of abrasion were taken, and sample images are shown in Figure 5.

Table 5.

Average diameter of the defect.

Figure 4.

Flaw diameter.

Figure 5.

An example image of a wear scar after examination, 5a—Rapeseed oil + 2.5% h-BN + 0.5% surfactant, 5b—Sunflower oil + 2.5% h-BN + 0.5% surfactant, 5c—Corn oil + 2.5% h-BN + 0.5% surfactant, 5d—Soybean oil + 2.5% h-BN + 0.5% surfactant, 5e—Priolube 3967 LQ + 2.5% h-BN + 0.5% surfactant.

Table 5 and the graph in Figure 4 show that the addition of a surfactant contained in the lubricating oil has a minor impact on the size of the flaw diameter obtained, so it does not play a significant role. The addition of hexagonal boron nitride h-BN has a much more substantial impact. As can be seen, the introduction of hexagonal boron nitride into the solution helps, in the case of vegetable oils, to achieve a much smaller flaw diameter (up to 15%), especially when the h-BN content is 2.5% by weight of the total lubricating solution. A similar trend can be observed in our previous research on PAO4 and CB30 oil [32], which may indicate the possibility of obtaining better tribological properties in this way. A surprising result was obtained for a lubricant prepared on the basis of Priolube ester oil; the addition of h-BN causes the size of the blemish to increase as its content increases. This mechanism requires further research, but already at this stage it can be concluded that the introduction of hexagonal boron nitride to ester oil (Priolube) may result in a deterioration of its tribological properties, at least in terms of anti-seize and anti-wear properties.

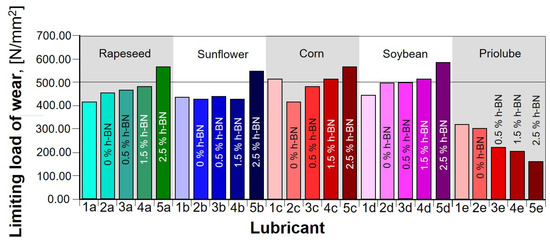

The results of the average flaw diameter obtained during the measurements were used to determine the limit load for circular economy consumption based on the formula [17].

where:

- —load on the friction node = 392.3 [N],

- —average flaw diameter [mm],

- —coefficient considering the distribution of forces in the friction node.

The effect of the surfactant only has a minor impact on the wear load limit; its main purpose is to obtain a more stable suspension of h-BN in the base oil. Only the introduction of h-BN allows for significant changes in achieved tribological parameters. However, its effect needs to be clarified; the observed results show that, in the case of some base oils, it is positive and very pronounced and is related to quantitative content. As seen from the results in Table 5 and the graph in Figure 6, there is an improvement in the tribological properties for all vegetable oils. The best result—an increase in the wear load limit of more than 30%—was in the case of soybean oil, and a similar result was obtained for other vegetable oils when the base oil was combined with oils containing 2.5% h-BN. Considering the amount of h-BN contained in the lubricant, the increase in the obtained value of the limiting seizure load increased, and only in the case of sunflower oil did a small amount of h-BN (up to 1.5%) have no effect. As can be seen from these tests, the introduction of h-BN into Priolube ester oil could be more beneficial in improving the tribological properties in terms of seizing load.

Figure 6.

Wear load limit GOZ.

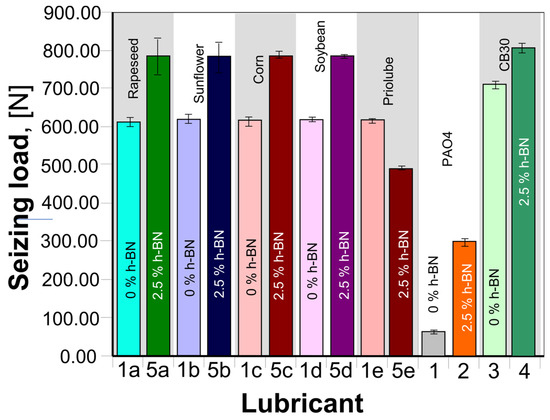

3.2. Seizure Load Determination

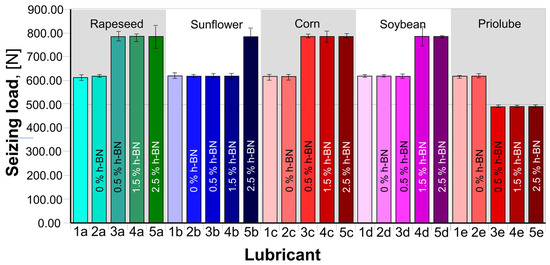

In further research, the oil compositions were tested on a four-ball tester to determine the seizing load. For this purpose, the working area of the four balls was filled with lubricating oil of appropriate composition. During operation, the load was systematically increased until a sudden increase in resistance to movement occurred, which was considered as the moment of initiation of the seizure. The measurement results are summarized in Table 6 and the graph in Figure 7.

Table 6.

Weld load.

Figure 7.

Weld load.

The results presented in Table 6 and Figure 7 show that the introduction of hexagonal boron nitride to a vegetable oil-based lubricating oil has a significant impact on the increase in seizing load by up to 27%. However, this does not apply to ester oil, for which, similarly to the limit load, there are indications of deterioration for this parameter. In the case of rapeseed and corn base oil, the addition of a small amount of h-BN (0.5% by weight) causes a sudden increase in the value of the seizing load; in the case of soybean oil, this effect can be achieved with just 1.5% by weight of h-BN and, in the case of sunflower oil, such an increase in the scuffing load is achieved only for 2.5% h-BN.

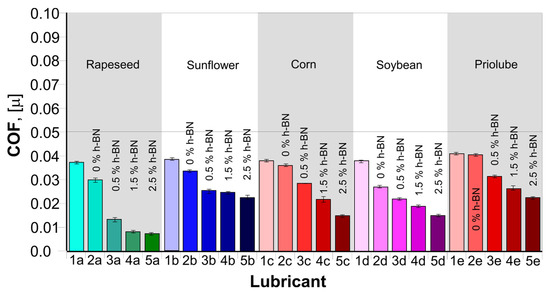

3.3. Measurement of the Friction Coefficient

The determination of the friction coefficient for individual oil compositions, according to Table 2, was based on the results of the friction torque measurement using the HFN5/E/16/029 apparatus. Measurements of the friction torque as a function of the bearing load were made for a rotational speed of 400 [rpm]. The results obtained are summarized in Table 7 and, based on this, the friction coefficient was determined for all tested oil mixtures.

Table 7.

Friction moment, friction force, friction coefficient.

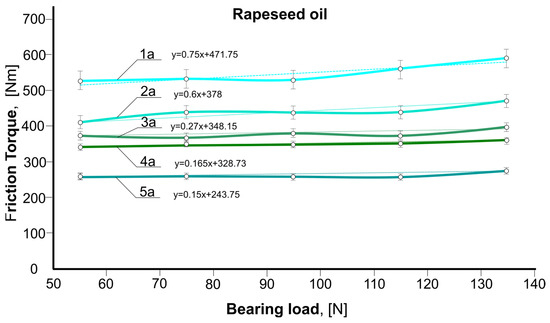

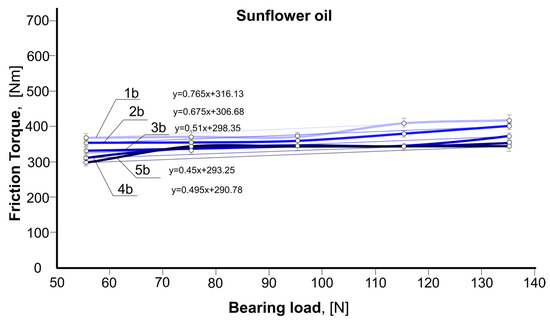

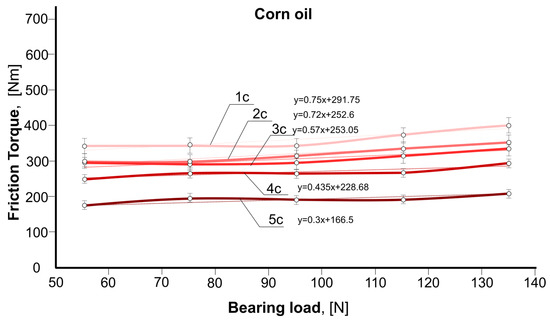

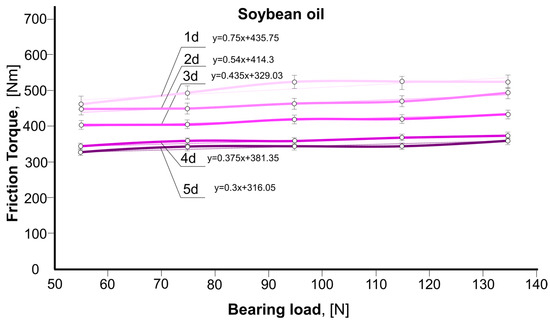

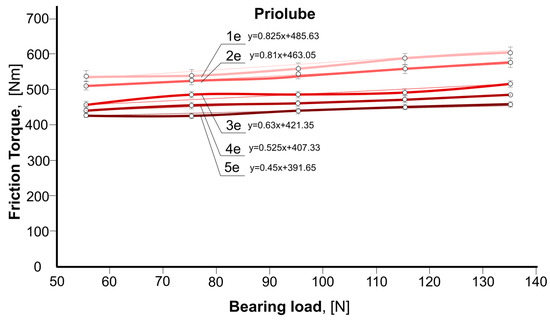

Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 present the relationship between the friction torque and the bearing load, which was used to determine the friction coefficient for the tested oil compositions. Figure 13 shows a graph of the obtained friction coefficient values for individual oil compositions.

Figure 8.

Relation between friction torque and bearing load for rapeseed oil.

Figure 9.

Relation between friction torque and bearing load for sunflower oil.

Figure 10.

Relation between friction torque and bearing load for corn oil.

Figure 11.

Relation between friction torque and bearing load for soybean oil.

Figure 12.

Relation between friction torque and bearing load for Priolube oil.

Figure 13.

Friction coefficient of the tested oil compositions.

As can be seen from the graphs presented in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12, in each case, an increase in load is accompanied by an increase in the friction torque, i.e., the angle of inclination of the trend lines for individual curves allows the determination of the angle whose tangent is equivalent to the friction coefficient. On the basis of these graphs, it can be concluded that it has the most significant impact on the change in the friction coefficient value in the case of rapeseed oil (approx. 80%) and the smallest impact in the case of sunflower oil (more than 50%). At the same time, based on Table 7 and the graph in Figure 12, it can be argued that in each of the analyzed cases, i.e., the introduction of both vegetable and Priolube hexagonal boron nitride ester oils into the oil, it can be seen that, in each of the tested oil compositions, the introduction of h-BN guaranteed a lower friction coefficient.

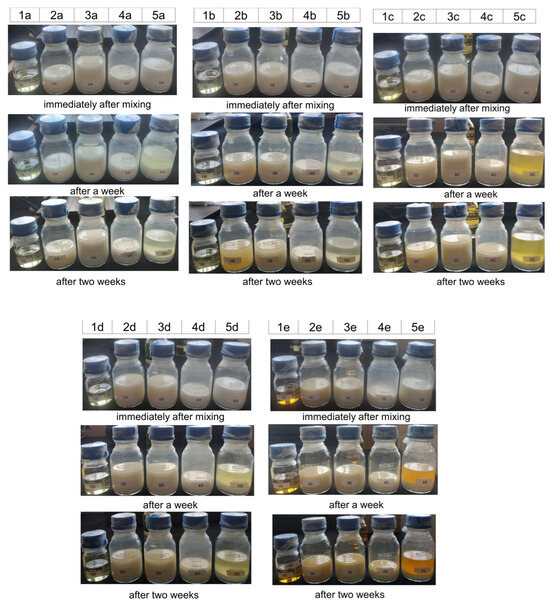

The stability of oil suspension was assessed based on direct observation of oil compositions; the observation was carried out for 14 days at the same time every day, and the appearance assessment was documented using photos. Below are only photos from three days, immediately after mixing, after a week, and after two weeks.

As can be seen from the photos (Figure 14), at the initial stage, the observed solutions showed the high quality of the mixture, but it can be seen that, systematically every day, gradual deposition of h-BN particles at the bottom could be seen. This problem can cause the properties of lubricating mixtures to deteriorate during their subsequent use. In the tests presented, this problem was avoided by mixing the oil compositions immediately before the test.

Figure 14.

Oil composition during storage.

3.4. Physicochemical Properties of Oil Mixture

Table 8 presents the physicochemical results of selected mixtures of base oils with h-BN. We measured pH, surface tension, density, and dynamic and kinematic viscosity of various mixtures of vegetable oil with the addition of a surfactant at a concentration of 0.5% and a solid substance—hexagonal boron nitride at concentrations of 2.5%.

Table 8.

Physicochemical results summary.

3.5. Comparison of Results

Analyzing the results presented in Table 8 for vegetable and Priolube 3967 LQ, we can conclude that adding surfactant improves the physicochemical properties of the oils. Adding a surfactant resulted in better dispersion of solid particles in the oil. In the samples analyzed, no sedimentation was observed in the case of nano-h-BN.

The higher the viscosity, the thicker the lubricating film formed on the friction surfaces, and the more difficult it is to force the oil out of the friction surfaces, which means that it better protects them from seizing. The mixture containing 0.5% surfactant and 2.5% h-BN showed the highest viscosity for vegetable oils.

Substances also exhibit the best lubricating properties that wet surfaces well, i.e., they have the lowest surface tension value. The lowest surface tension values were obtained in the Sunflower and Soybean oil mixtures with 0.5% surfactant and 2.5% hBN.

The obtained optimal physicochemical parameters of vegetable oil mixtures with a surfactant of 0.5% concentration and 2.5% addition of solids (70 mn h-BN) confirm the accuracy of the tests described earlier.

Analyzing the results for the vegetable oil and Priolube 3967 LQ (without the addition of surfactant), it can be concluded that, as in the case of vegetable oils, the most optimal physical and sheath properties are demonstrated by oil mixtures with the addition of 2.5% h-BN: the lowest surface tension and the highest viscosity value.

In further research, the results obtained were compared with tests previously carried out under the same conditions but on other base oils [34], because the presented work is a continuation of research aimed at assessing the impact of hexagonal boron nitride nanoparticles on the tribological properties of various oil compositions. Previously, selected mineral oils that are currently biodegradable, including vegetable oils, were assessed. This comparison allows for evaluating whether, at least due to their tribological properties, vegetable oils can replace mineral oils.

As seen from Table 8 and the graphs in Figure 15 and Figure 16, all vegetable oils (rapeseed, sunflower, corn, soybean) tested in this work show promising tribological properties. Although they are slightly worse than commercial CB30 oil, they are better than base oil based on PAO4 polyalphaolefins.

Figure 15.

Wear scar diameter.

Figure 16.

Seizing load.

4. Conclusions

The work is part of multistage research, presented in a previous publication [34], with the aim of assessing the possibility of improving the lubricating properties of oils in which h-BN nano-powder was used.

The research indicates that the use of hexagonal boron nitride nano-powder may provide a good direction to improve the lubricating properties of both mineral and vegetable oils. Vegetable oils do not differ in their lubricating properties from commercial oils recognized on the market. What may be very important in the event of a possible transition to “green” production is that, in many cases, expensive and difficult-to-produce mineral oils can probably be replaced with vegetable oils. Moreover, the proposed oil compositions are biodegradable and harmless to health, which cannot be said for mineral oils.

The results obtained in this study show that the addition of layered h-BN nano-powder to the oil allows promising lubricating properties to be obtained. Furthermore, rapeseed oil with 2.5% h-BN and 0.5% surfactant allowed for achieving a friction coefficient of as much as 80%. Similarly, good results were obtained for other parameters, i.e., wear limit load higher by 30% and welding load higher by 27%. The mixture containing 0.5% surfactant and 2.5% h-BN showed the highest viscosity for vegetable oils, and the lowest surface tension values were obtained in the Sunflower and Soybean oil mixtures.

Unfortunately, an operational problem may be the great difficulty in obtaining a solid, well-dispersed oil suspension due to the characteristics of layer additives. Therefore, this fact should be of further interest to researchers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M. and M.G.; methodology, T.M. and A.D.P.; validation, M.G. and A.D.P.; formal analysis, W.U. and A.D.P.; data curation, W.U., T.M., A.M. and A.D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, W.U., T.M., A.M. and A.D.P.; writing—review and editing, W.U., T.M., M.G., A.M. and A.D.P.; visualization, W.U.; supervision, W.U., T.M. and A.D.P.; funding acquisition, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are available within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Julia Cieslicka and Michal Rosiak from Kazimierz Wielki University for their help in preparing oil samples for testing. The Military University of Technology (UGB no. 22-891/2021), Kazimierz Wielki University (POIR.04.04.00-00-0004/15) supported this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bartels, T.; Bock, W.; Braun, J.; Bush, C.; Buss, W.; Dresel, W.; Freiler, C.; Harperscheid, M.; Heckler, R.P.; Hörner, D.; et al. Lubricants and Lubrication. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canter, N. Biodegradable lubricants: Working definitions, review of key applications and prospects for growth. Tribol. Lubr. Technol. 2020, 76, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, P.; Kucharska, K.; Kamiński, M. Ecological and Health Effects of Lubricant Oils Emitted into the Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Test No. 301: Ready Biodegradability, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 3; OECD: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Guideline for Testing of Chemicals. 2005. Available online: www.oecd.org/chemicalsafety/testing/34898616.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Bio-Based Lubricants Market Size—Global Industry, Share, Analysis, Trends and Forecast 2023–2032. February 2023. Available online: https://www.acumenresearchandconsulting.com/bio-based-lubricants-market (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Salimon, J.; Salih, N.; Yousif, E. Biolubricants: Raw materials, chemical modifications and environmental benefits. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2010, 11, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Non-Food Crops Centre. NNFCC Conference Poster. Improved winter rape varieties for biolubricants Archived 4 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Available online: https://al.io.vn/en/Lubricant (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Lee, T. Safflower oil hailed by scientists as possible recyclable, biodegradable replacement for petroleum. ABC News, 7 June 2020; Australian Broadcasting Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M. Plant-oil-based lubricants and hydraulic fluids. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 1769–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K. Abrasive Wear of Metals. Tribol. Int. 1997, 30, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, W.; Kałdonski, T.; Kałdonski, T.J.; Pawlak, Z. Hexagonal boron nitride as a component of the iron porous bearing: Friction on the porous sinters up to 150 °C. Meccanica 2016, 51, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Goltsberg, R.; Etsion, I. Modeling Adhesive Wear in Asperity and Rough Surface Contacts: A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 6855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, Z.; Kałdoński, T.; Urbaniak, W. A hexagonal boron nitride-based model of porous bearings with reduced friction and increased load. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2010, 224, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, W.; Kałdoński, T.; Hagner-Derengowska, M.; Kałdoński, T.J.; Madhani, J.T.; Kruszewski, A.; Pawlak, Z. Impregnated porous bearings textured with a pocket on sliding surfaces: Comparison of h-BN with graphite and MoS2 up to 150 °C. Meccanica 2015, 50, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, D.; Bhusahan, B. Effect of MoS2 and WS2 Nanotubes on Nanofriction and Wear Reduction in Dry and Liquid Environments. Tribol. Lett. 2013, 49, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Wakabayashi, T.; Okada, K.; Wada, T.; Nishikawa, H. Boron nitride as a lubricant additive. Wear 1999, 232, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Jin, Y.; Sun, P.; Ding, Y. Tribological behaviour of a lubricant oil containing boron nitride nanoparticles. Procedia Eng. WCPT7 2015, 102, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramteke, S.; Chelladurai, H. Examining the role of hexagonal boron nitride nanoparticles as an additive in the lubricating oil and studying its application. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part N J. Nanomater. Nanoeng. Nanosyst. 2020, 234, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelonis, D.A.; Tereshko, J.W.; Andersen, C.M. Boron nitride powder—A high performance alternative for solid lubrication. GE Adv. Ceram. 2003, 4, 81506. [Google Scholar]

- Carrion, F.J.; Gines, M.N.; Iglesias, P.; Sanes, J.; Bermudez, M.D. Liquid crystals in tribology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 4102–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałdoński, T.; Krol, A.; Giemza, B.; Gocman, K.; Kałdońnski, T.J. Porowate Łożyska Ślizgowe Spiekane z Proszku Żelaza z Dodatkiem Heksagonalnego Azotku Boru h-BN [Porous Slide Bearings Sintered from Iron Powder with Addition of Hexagonal Boron Nitride h-BN]. Patent P401050, 4 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Senyk, S.; Kałdoński, T. Analysis of the influence of hexagonal boron nitride on tribological properties of grease. Tribologia 2022, 3, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaso, P.; Dassenoy, F.; Ville, F.; Diaby, M.; Vacher, B.; Le Mogne, T.; Beli, M.; Cavoret, J. An investigation on the reduced ability of IF-MoS2 nanoparticles to reduce friction and wear in the presence of dispersants. Tribol. Lett. 2014, 55, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, W.; Majewski, T.; Woźniak, R.; Sienkiewicz, J.; Kubik, J.; Petelska, A.D. Research on the influence of the manufacturing process conditions of iron sintered with the addition of layered lubricating materials on its selected properties. Materials 2020, 13, 4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gocman, K.S.; Kałdoński, T.; Giemza, B.B.; Król, A. Permeability and Load Capacity of Iron Porous Bearings with the Addition of Hexagonal Boron Nitride. Materials 2022, 15, 5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałdoński, T. Tribologiczne Zastosowania Azotku Boru. In Tribological Applications of Boron Nitride, 2nd ed.; MUT: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Groszek, A.J.; Whiteridge, R.E. Surface properties and lubricating action of graphite MoS2. Am. Soc. Lubr. Eng. Trans. 1971, 14, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ay, N.; Ay, G.M.; Goncu, Y. Environmentally friendly material: Hexagonal boron nitride. J. Boron 2016, 1, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Senyk, S.; Perehubka, M.; Kałdoński, T. Lubricity tests for oils containing hexagonal boron nitride. Bull. Mil. Univ. Technol. 2019, 68, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, C.J.; Menezes, P.L.; Lovell, M.R.; Jen, T.-C.H. The size effect of boron nitride particles on the tribological performance of biolubricants for energy conservation and sustainability. Tribol. Lett. 2013, 51, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K.; Bijwe, J.; Padhan, M. Role of size of hexagonal boron nitride particles on tribo-performance of nano and micro oils. Lubr. Sci. 2018, 30, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, A.; Haq, M.I.U.; Anand, A.; Mohan, S.; Kumar, R.; Jayalakshmi, S.; Singh, R.A. Nanodiamond particles as secondary additive for polyalphaolefin oil lubrication of steel—Aluminium contact. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, W.; Majewski, T.; Powązka, I.; Śmigielski, G.; Petelska, A.D. Study of Nano h-BN Impact on Lubricating Properties of Selected Oil Mixture. Materials 2022, 15, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granja, V.; Jogesh, K.; Taha-Tijerina, J.; Higgs, C.F., III. Tribological Properties of h-BN, Ag and MgO Nanostructures as Lubricant Additives in Vegetable Oils. Lubricants 2024, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Bu, Y.; Guan, P.; Yang, Y.; Qing, J. Tribological properties of hexagonal boron nitride nanoparticles as a lubricating grease additive. Lubr. Sci. 2023, 35, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczewski, R.; Szczerek, M.; Tuszyński, W.; Wulczyński, J. A four-ball machine for testing antiwear, extreme-pressure properties, and surface fatigue life with a possiblility to increase the lubricant. Tribologia 2009, 1, 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Balmain, W.H. On ethogen and ethonides. Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1843, 12, 466–470. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, J.E.; Devlin, M.T.; Prakash, B. Lubricant additives for improved pitting performance through a reduction of thin-film friction. Tribol. Int. 2014, 80, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuki, M.; Matsukawa, H. Systematic Breakdown of Amontons’ Law of Friction for an Elastic Object Locally Obeying Amontons’ Law. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).