Abstract

Background/Objectives: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in wildlife is an emerging public health concern due to the risk of zoonotic transmission, especially through the food chain, yet data on free-ranging animals remain scarce. This study examined the presence and patterns of AMR among bacteria isolated from hunted wild boars in the Campania region of Italy. Methods: Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) was used to identify bacterial isolates from wild boar meat and carcass swabs to the species level, and the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion test was applied to screen 205 isolates, spanning 20 bacterial genera, against a panel of clinically relevant antibiotics. Resistance metrics were analyzed at genus and antibiotic levels, and patterns were visualized using a hierarchically clustered heatmap. Results: Resistance was detected in 15 of the 20 genera, with full susceptibility observed in Acinetobacter, Arthrobacter, Glutamicibacter, Leclercia, and Rahnella. Overall, 67.3% (138/205) of the isolates showed resistance to at least one antibiotic, with 33.7% (69/205) classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR). Carbapenems retained the highest activity (≥95% susceptibility) among all genera tested, while amoxicillin/clavulanate (78.4%) and aztreonam (57.4%) exhibited the highest mean resistance. Among potential pathogens, Escherichia coli exhibited an extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-like phenotype, with resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanate (67%), aztreonam (54%), and ceftazidime (47%) but preserved carbapenem susceptibility. Staphylococcus spp. showed pronounced resistance to linezolid (57%) and erythromycin (52%), whereas Pseudomonas isolates demonstrated elevated resistance to aztreonam and ceftazidime (57% each). Opportunistic pathogens such as Alcaligenes faecalis and Pantoea agglomerans showed peak resistance to ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanate. Pathogens and opportunistic pathogens demonstrated higher mean resistance (>30%) than commensals (≤32%), but the difference in mean and median resistance levels was not statistically significant (Mann–Whitney’s U test, W = 4, p = 0.39). Conclusions: These findings highlight the widespread occurrence of AMR and MDR phenotypes, with clinically significant resistance patterns in wild-boar-associated bacteria, including non-pathogenic strains, highlighting their role in the amplification of AMR. Although the preservation of carbapenem susceptibility underscores their potential as last-line antibiotics, the high resistance to commonly used antibiotics raises concerns for zoonotic transmission. Surveillance of wildlife reservoirs therefore remains critical for integrated AMR control.

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a natural evolutionary process in which microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi, develop the ability to adapt to and resist the effects of drugs that once killed or inhibited them, rendering them ineffective [1]. In recent years, there has been a global surge in AMR and the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDR), posing a public health threat [2]. This has primarily been attributed to the overuse and misuse of antimicrobial agents in both human and veterinary medicine, as well as in agriculture [3].

While society grapples with the consequences of misuse and overuse of antimicrobials, emerging sources of AMR have become a focal point of scientific research. One such area of interest is the potential role of wildlife in the spread of AMR. Studies have shown that wild animals can harbor a variety of bacteria, including strains carrying multiple resistance genes that can be exchanged between pathogenic and non-pathogenic organisms [4,5]. Subsequently, these can be transferred to humans during the handling, processing, and consumption of wild game meat, creating a direct pathway for the spread of antimicrobial resistance [6]. Furthermore, increased interaction between wildlife, domestic animals, and humans provides an interface for horizontal gene transfer, especially in environments contaminated with antimicrobial residues or resistant microbes. Such interactions facilitate the dissemination of resistance determinants across species and ecosystems, amplifying the AMR risk [7,8].

While much focus has been placed on pathogenic bacteria as the primary drivers of AMR transmission, non-pathogenic bacteria, often referred to as commensal or environmental bacteria, play an equally critical but largely unexplored role. These bacteria, which naturally inhabit the gut, skin, and mucosal surfaces of animals and humans, as well as soil and water environments, frequently harbor resistance genes within their genomes or in mobile genetic elements such as plasmids, transposons, and integrons [9]. Although these bacteria may not directly cause disease, they act as silent reservoirs of resistance genes that can be transferred to pathogenic species through horizontal gene transfer mechanisms like conjugation, transformation, and transduction. This gene exchange potential therefore enables non-pathogenic bacteria to become essential players in the environmental resistome [10,11].

In food production systems, commensal bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. and Lactobacillus spp. can acquire and disseminate resistance determinants within the microbiota of animals [12]. These bacteria persist throughout slaughtering, meat processing, and handling stages, contaminating carcasses and the environment, especially in less ideal hygienic conditions [13]. Once in the food, they can colonize the human gut, where they may exchange resistance genes with opportunistic or pathogenic bacteria, thus forming an invisible bridge between environmental and clinical reservoirs of AMR [11,14]. In wild animals, such bacteria may be naturally exposed to resistant strains from agricultural runoff, contaminated water, or contact with livestock, allowing them to accumulate and maintain resistance genes even in the absence of antibiotic exposure [15].

Wild boars are particularly relevant in this issue. As omnivorous animals with scavenging and rooting behaviors, they frequently encounter environments contaminated with antimicrobial residues, fecal bacteria, and resistant organisms from livestock and human waste [16]. This exposure facilitates colonization by resistant bacteria, many of which may persist in their gut and skin flora. Given their popularity as game animals, wild boars are hunted for both sport and culinary purposes in various regions across the globe, and their meat has become an integral part of local diets, contributing to the economic and cultural fabric of communities [17]. However, the very practices that sustain this relationship between humans and wild boars may also foster a conducive environment for the spread of resistant bacteria, given their role as potential carriers of resistant bacteria, both through direct contact and the consumption of contaminated meat. Considering the potential for the spread of AMR through the food chain, efforts to combat antimicrobial resistance should therefore not be limited to healthcare settings but must extend to include comprehensive surveillance and regulation within the food production and distribution systems [18].

While several studies have reported AMR in wild boar populations in Italy [19,20] and other parts of the world [21], they have primarily focused on pathogenic bacteria recovered from fecal samples. Consequently, a critical knowledge gap persists regarding the resistance profile of bacteria present on carcasses and in edible meat, which is directly relevant to public health. Moreover, globally, studies have focused on screening pathogenic bacteria but have largely neglected non-pathogenic and environmental strains. Such bacteria may not pose an immediate health threat but may serve as important intermediaries for resistance gene transfer during food handling or within the human gut following ingestion [22]. As a result, neglecting non-pathogenic bacteria in surveillance programs underestimates the overall burden and complexity of AMR transmission in food systems.

Comprehensive epidemiological studies that incorporate both pathogenic and commensal bacteria from wild boar populations, as well as in the meat destined for human consumption, are essential for understanding the scope of the problem, as well as providing a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of AMR transmission, including the potential for spillover to human and domestic animal populations [16]. Considering this, the present study aims to unravel the AMR profiles of commensal and pathogenic bacteria isolated from wild boar carcasses. Specifically, we seek to determine the potential role of wild boar meat in the transmission of AMR to humans. We aim to emphasize the critical need to expand monitoring programs to include non-pathogenic bacteria as key indicators of resistance dissemination, thereby providing the basis for informed mitigation strategies and promoting food safety.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sourcing and Identification of Isolates

The study assessed antibiotic the susceptibility of 205 bacterial isolates from the strain collection from a previous study by Peruzy et al. [23], which isolated bacteria from carcass swabs and meat of 36 wild boars hunted between October and December 2019 from the Campania region of Italy. The isolates were stored at −20 °C at the microbiology laboratory at the Department of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Production, University of Naples Federico II. Pure colonies of all isolates were re-identified by MALDI TOF-MS, as specified by the manufacturer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Spectral acquisition and analysis were performed using the MALDI BioTyper’s, MBT Compass® HT (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). A score of ≥2 was considered valid for species-level identification, while that between 1.7 and 2 was considered valid for genus-level identification. A score ≤ 1.7 was considered invalid.

2.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

The Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method for screening for antibiotic resistance was performed according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [24] (EUCAST) protocol using a panel of commonly used antibiotics (antibiotic disks ROSCO NEO-SENSITABSTM; sourced from Rosco Diagnostica A/S Taastrugaardsvej 30, DK-2630, Taastrup, Denmark). The choice of antibiotics tested for each organism was based on whether they were indicated for use against the specific bacteria and whether EUCAST clinical breakpoints for the antibiotics were available. The antibiotics disks included were ampicillin (10 µg), ampicillin (2 µg), amoxicillin–clavulanate (3 µg), aztreonam (30 µg), benzyl penicillin (1 U), ceftazidime (10 µg), cefoxitin (30 µg), cefotaxime (5 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), gentamycin (30 µg), imipenem (10 µg), levofloxacin (5 µg), linezolid (10 µg), meropenem (10 µg), oxytetracycline (30 µg), piperacillin–tazobactam (36 µg), tetracycline (10 µg), tigecycline (15 µg), trimethoprim–sulphamethoxazole (25 µg), and vancomycin (5 µg), as indicated in Figure 1 and Supplementary Material Table S1. A fresh culture of the bacteria was diluted in a normal saline solution, and its turbidity was adjusted to 0.5 McFarland’s standard before inoculating a loopful onto a Mueller–Hinton agar plate (OXOID, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom; catalog number CM0131B) (for non-fastidious) or Mueller–Hinton agar + 5% defibrinated horse blood and 20 mg/L β-NAD (OXOID, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom; catalog number PB1229A) (for fastidious organisms). The antibiotic disks were placed onto the inoculated agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h for non-fastidious organisms or in the presence of CO2 at 37 °C for 18–24 h for fastidious organisms. The inhibition zone was measured, and readings were compared with those specified in the EUCAST clinical breakpoint table [25] to categorize the organism as susceptible or resistant. For organisms for which no breakpoints were available, comparisons were made based on clinical breakpoints for other organisms closely related to them (Table 1). Organisms were classified as MDR if they showed resistance to ≥3 antibiotic classes in accordance with the classification criterion by [26].

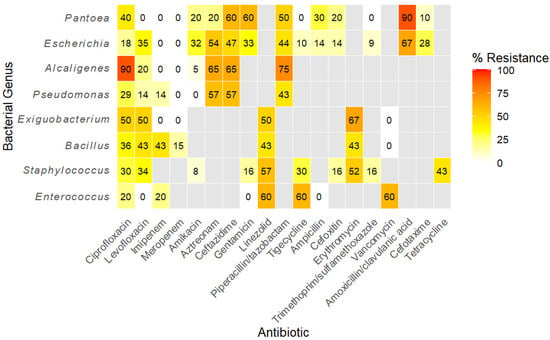

Figure 1.

Heatmap showing the distribution of antibiotic resistance among bacterial genera based on isolate-level testing. Resistance values are expressed as the percentage of isolates resistant to each antibiotic. Genera tested against similar antibiotics are clustered together. Grey cells denote combinations for which testing was not performed.

Table 1.

EUCAST clinical breakpoints applied to interpret antimicrobial susceptibility test results of the different genera of bacteria.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in the CRAN project’s R statistical software version 2025.05.1 + 513 [27]. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the main characteristics of the antimicrobial resistance profiles of the bacterial isolates from wild boar carcasses. Frequencies and percentages were calculated to summarize categorical variables, and median, means, and standard deviations were used to summarize numerical variables. Heatmaps of resistance to specific antibiotics were constructed using the R package ggplot2 for genera of bacteria with at least 5 isolates tested. Differences in resistance levels between pathogens and non-pathogenic bacteria were assessed by the Mann–Whitney U test as described in [28]. p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial Isolates Tested

The 205 isolates studied included both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, some of which are considered pathogenic, while others are commensals or environmental, belonging to 20 bacterial genera, dominated by Staphylococcus, Escherichia, Alcaligenes, and Bacillus, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Composition and description of bacterial isolates for which antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed. Isolates were recovered from hunted wild boars from the Campania region, Italy.

3.2. Antibiotic Resistance Profiles

As shown in Table 3, resistance to antibiotics was detected among bacteria belonging to 15 of the 20 genera (75%), while 5 (20%) including Acinetobacter, Fictibacillus, Glutamicibacter, Leclercia, and Rahnella were fully susceptible. Overall, 138 of the 205 isolates (67.3%) were resistant to at least one antibiotic, of which 7 were resistant to only one antibiotic, 11 to two, and 120 to three or more antibiotics. Additionally, 69 isolates (33.7%) were classified as multidrug-resistant.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial resistance profiles of 205 bacteria isolated from wild boars from Campania region, Italy.

3.3. Antibiotic Resistance Patterns

Antibiotic resistance patterns were analyzed for eight genera of bacteria that had representative isolates greater than five. The overall median resistance was 35% (IQR 14–58%). Susceptibility to carbapenems (imipenem and meropenem) was retained across all genera (≥95%). Conversely, the highest mean resistance was recorded for amoxicillin/clavulanate and aztreonam (78.4% and 57.4%, respectively) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Resistance metrics for specific antibiotics.

A hierarchically clustered heatmap (Figure 1) partitioned isolates into two principal groups: Gram-negative genera characterized by extensive β-lactam and aztreonam resistance and Gram-positive genera distinguished by resistance to protein synthesis inhibitors (tigecycline, linezolid, and tetracycline). Genus-specific profiles revealed that the opportunistic pathogens Alcaligenes and Pantoea showed the highest single-drug resistance (ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanate, each 90%). Among primary pathogens, Escherichia displayed a classical extended-spectrum β-lactamase phenotype with high resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanate (67%), aztreonam (54%), and ceftazidime (47%) but full susceptibility to carbapenems. Pseudomonas showed elevations in aztreonam and ceftazidime resistance (57% each). Staphylococcus demonstrated pronounced linezolid (57%) and erythromycin (52%) resistance, while Enterococcus and Exiguobacterium shared similarly elevated tigecycline and linezolid resistance (≤67%).

As shown in Table 5, true pathogens and opportunistic pathogens presented higher mean resistance (>30%) and extreme peaks (>90%) than commensal/environmental genera (mean ≤32%, peaks ≤67%), but carbapenem activity (<15%) was maintained across pathogenic categories. However, the levels of resistance to antibiotics did not differ significantly between the groups (Mann–Whitney’s U test, W = 4, p = 0.39).

Table 5.

Comparison of resistance metrics stratified by pathogenic status.

4. Discussion

The phenotypic antibiotic susceptibility testing of 205 bacterial isolates spanning 20 genera, obtained from wild boar carcass swabs and meat samples in the Campania region of Italy, reveals a complex landscape of resistance that mirrors both wildlife ecology and anthropogenic pressures.

Overall, 67.3% (138/205) of the isolates exhibited resistance to at least one antibiotic, and 33.7% (69/205) were MDR, highlighting the substantial carriage of resistant bacteria in free-ranging wild boars. Other Italian studies likewise reported MDR prevalences in bacteria isolated from wild boars ranging from 5.6% to 100%. These included 5.6% among Salmonella spp. isolates from spleens, livers, and rectal swabs of wild boars from Tuscany [20], 62.5% among nasal swab Enterococcus spp. and Staphylococcus spp. isolates from Campania [64], and 100% among Escherichia coli from mesenteric lymph nodes and feces of 23.3% of wild boars sampled in northern Italy [65]. These studies suggest a consistent reservoir function of wild boars across regions. While the figures in this study are comparable to other Italian studies, there is a consistent trend of higher prevalences being reported in the south than in the north of Italy. The elevated resistance in this study could reflect local AMR selection pressures either from anthropogenic environmental contamination or agricultural antibiotic use, as well as regional ecological factors, as reported by Karwowska [66]. Notably, intensive farming activity is prevalent across the Campania region, potentially promoting environmental dissemination of resistant bacteria through run-offs, manure application, or water systems [67]. The MDR prevalences in this study are also comparable to those reported in other European studies; for example, a study by Sabença et al. [68] in Portugal identified 44% MDR prevalence among E. coli isolates from wild boars, while a German study by Günther et al. [69] reported a 56% prevalence of MDR among E. coli.

The public health implications of these findings are profound. Due to their rapidly expanding populations and intensified contact with agricultural and peri-urban landscapes, wild boars represent a significant ecological interface for the transmission of resistant bacteria [16]. The carriage of MDR bacteria in these animals introduces the possibility of gene flow between environmental, animal, and huma microbiota, especially through hunting or food contamination [70,71].

While MDR organisms are a big concern, ESBL and carbapenemase producers are particularly urgent global health threats, with related infections associated with mortality rates of up to 50%. Moreover, the development of resistance to these often last-resort antibiotics leads to the dependence on older, more toxic drugs such as colistin, presenting a further challenge to health management [72]. In this study, Gram-negative genera demonstrated resistance predominantly to β-lactams and monobactams. Particularly, resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanate (67%), aztreonam (54%), and ceftazidime (47%) alongside universal susceptibility to imipenem and meropenem (carbapenems) was observed among Escherichia isolates, consistent with the ESBL phenotype as described by Husna et al. [73]. This pattern mirrors findings from other wild boar studies in Europe, where resistance to carbapenems remains low; 0% as reported by Rega et al. [74], Selmi et al. [75], and Pătrînjan et al. [76], and 5.9% by Holtmann et al. [77], while extended-spectrum cephalosporins show high resistance frequencies (up to 85%) [75,76,78]. The preservation of carbapenem activity suggests limited selective pressure for carbapenemase genes in the wild.

Among Gram-positive genera (including Staphylococcus spp. and Enterococcus spp.), resistance to protein synthesis inhibitors, including linezolid, tigecycline, and erythromycin, was dominant. Macrolide (erythromycin) resistance is commonly detected in wild-boar-associated bacterial isolates, while tigecycline resistance remains principally a clinical and production-animal concern and is rarely reported in primary wild boar field studies [64,79]. For example, Poeta et al. [80] found 48.5% erythromycin resistance among fecal Enterococcus isolates from Portuguese wild boars, while a meta-analysis by Akwongo et al. [81] reported a 22% macrolide resistance across studies. Studies by [82] reported phenotypic resistance to linezolid as well as the carriage of the transferable genes optrA and poxtA that are responsible for linezolid resistance in E. faecalis and E. feacium isolates, from in wild boars in Italy. Additionally, linezolid resistance in Enterococcus spp. isolates in other Italian wildlife was also reported by Smoglica et al. [83], albeit at low levels. While resistance to linezolid remains rare in wildlife [81,82,83], there have been more frequent reports in livestock-associated S. aureus [84,85,86] and Enterococcus spp. [87,88], suggesting possible cross-species transmission routes [88,89,90]. Linezolid resistance in wild boars and other wildlife, especially those that are hunted for human consumption, is particularly concerning and warrants close surveillance to prevent its transmission through the food chain, as it is considered a last-resort antibiotic for MDR Gram-positive infections [91].

Opportunistic pathogens such as Alcaligenes faecalis and Pantoea agglomerans exhibited the highest single-drug resistance peaks (90%) to ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanate, indicating their ability to accumulate resistance determinants even in wildlife hosts. Previous studies have reported extensively resistant (XDR) and pan-drug-resistant (PDR) Alcaligenes faecalis, with resistance rates as high as 83.6% in human studies [31,92]. Moreover, recent studies have also identified high-level quinolone resistance in environmental isolates of Alcaligenes faecalis, attributing it to efflux pump overexpression and chromosomal mutations [93,94]. By contrast, some environmental commensals such as Rahnella aquatilis remained fully susceptible. This dichotomy echoes European surveillance data, which often demonstrates elevated quinolone and β-lactam resistance in opportunistic Gram-negatives from wildlife, likely driven by agricultural run-offs and contaminated water and feed sources, while purely environmental bacteria genera retain susceptibility [95,96]. The complete susceptibility of some of the environmental genera may also suggest variability in environmental exposure and intrinsic resistance mechanisms.

Furthermore, true pathogens and opportunistic pathogens showed higher resistance metrics than commensals or environmental isolates. True pathogens and opportunistic pathogens demonstrated mean resistance rates exceeding 30%, with peaks reaching 90%, in contrast to the generally lower rates observed in environmental isolates. This association has been documented elsewhere, likely due to increased selective pressures faced by pathogenic bacteria either in hosts previously exposed to antibiotics or through horizontal gene transfer in microbiomes with higher antibiotic exposure [6,97]. This trend is also supported by the One Health framework, which posits that zoonotic pathogens, due to frequent host transitions and environmental adaptability, often acquire and maintain resistance genes [98]. Notably, S. aureus and E. coli, both well characterized pathogens, exhibited classical resistance profiles, including linezolid and β-lactam resistance, respectively, patterns that have frequently been documented in clinical and environmental studies [99,100]. Despite the higher resistance metrics observed among pathogens than environmental bacteria, the difference is not statistically significant. This therefore reinforces the argument that non-pathogenic bacteria can equally contribute to amplification of AMR along the food production chain, as suggested in [22].

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study provide compelling evidence that wild boars are significant reservoirs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, including MDR strains of species with clinical relevance. The observed resistance patterns reflect both bacterial phylogeny and pathogenic status, with notable differences between Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains. Despite the extensive resistance profiles observed, susceptibility to carbapenems and amikacin was generally conserved across all genera, which emphasizes the critical importance of these antibiotics as last-resort treatments and highlights the need for stringent control of their use in both human and veterinary medicine contexts. However, the presence of resistance to other potent antibiotics, even if at low levels, raises concerns over potential future shifts in resistance if selection pressures increase.

Further, the resistance patterns observed in Campania suggest a more diverse and possibly advanced development of resistance across both environmental and clinically significant bacteria. This trend may reflect ecological pressures within the Mediterranean biome, driven by high human–wildlife interaction and dense agricultural land use, as well as variability in resistance mechanisms such as intrinsic resistance among bacteria. Furthermore, the presence of resistance in bacteria like Macrococcus spp. and Rothia spp., organisms often dismissed as harmless commensals, even at low percentages, supports emerging views that these non-pathogenic organisms can act as reservoirs or conduits for resistance genes, potentially transferring them to more virulent or invasive species.

While this study provides relevant information regarding antibiotic resistance profiles of pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacterial isolates from wild boar carcasses, it is limited to phenotypic resistance. A further investigation to unravel the resistance profiles and patterns at the genotypic level is recommended to provide a clearer understanding of the underlying resistance mechanisms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antibiotics15010065/s1, Table S1: Resistance of different bacterial genera to different classes of antibiotics.

Author Contributions

C.J.A., K.H., L.S., L.B., A.F., N.M. and M.F.P. were involved in the conceptualization of the study; laboratory analysis was performed by C.J.A., M.F.P. and L.S.; data analysis was performed by C.J.A.; drafting and reviewing of the manuscript were performed by C.J.A., K.H., L.S., L.B., A.F., N.M. and M.F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is part of the CRESCENDO Doctoral Program funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie program (MSCA-COFUND-2020) with grant agreement no. 101034245.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not involve live animals or the collection of primary samples. All bacterial isolates analyzed were from previous studies. The research was conducted in accordance with institutional and national ethical guidelines governing laboratory research. Ethical approval for animal experimentation was therefore not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with this study have been included in the manuscript. Additional information can be obtained from the Supplementary Materials and/or by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| ESBL | Extended-spectrum beta lactamase |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| PDR | Pan-drug-resistant |

| µg | Microgram |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

References

- Reygaert, W.C. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Founou, R.C.; Founou, L.L.; Essack, S.Y. Clinical and economic impact of antibiotic resistance in developing countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189621. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, C. Positive Association between the Use of Quinolones in Food Animals and the Prevalence of Fluoroquinolone Resistance in E. coli and K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa: A Global Ecological Analysis. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, V.R.; Bowen, R.A.; Bosco-Lauth, A.M. Zoonotic pathogens from feral swine that pose a significant threat to public health. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramey, A.M.; Ahlstrom, C.A. Antibiotic resistant bacteria in wildlife: Perspectives on trends, acquisition and dissemination, data gaps, and future directions. J. Wildl. Dis. 2020, 56, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza-Rodríguez, C.; Alt, K.; Grobbel, M.; Hammerl, J.A.; Irrgang, A.; Szabo, I.; Stingl, K.; Schuh, E.; Wiehle, L.; Pfefferkorn, B. Wildlife as sentinels of antimicrobial resistance in Germany? Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 7, 627821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugochi, L. Antimicrobial Resistance in Indicator Bacterial Species from Wildlife at the Human-Livestock-Wildlife Interface in the Mnisi Community, Mpumalanga, South Africa. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) as a form of human–wildlife conflict: Why and how nondomesticated species should be incorporated into AMR guidance. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberte, L.E.; van Schaik, W. Antibiotic resistance in the commensal human gut microbiota. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 68, 102150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Wintersdorff, C.J.H.; Penders, J.; van Niekerk, J.M.; Mills, N.D.; Majumder, S.; van Alphen, L.B.; Savelkoul, P.H.M.; Wolffs, P.F.G. Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance in Microbial Ecosystems through Horizontal Gene Transfer. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongre, D.S.; Saha, U.B.; Saroj, S.D. Exploring the role of gut microbiota in antibiotic resistance and prevention. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2478317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbehiry, A.; Marzouk, E. From Farm to Fork: Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacterial Pathogens in Livestock Production and the Food Chain. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Narvaez-Bravo, C.; Zhang, P. Driving forces shaping the microbial ecology in meat packing plants. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1333696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Dou, Q.; Smalla, K.; Wang, Y.; Johnson, T.A.; Brandt, K.K.; Mei, Z.; Liao, M.; Hashsham, S.A.; Schäffer, A. Gut microbiota research nexus: One Health relationship between human, animal, and environmental resistomes. mLife 2023, 2, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, A.M. Antimicrobial resistance: Wildlife as indicators of anthropogenic environmental contamination across space and through time. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R1385–R1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, R.T.; Fernandes, J.; Carvalho, J.; Cunha, M.V.; Caetano, T.; Mendo, S.; Serrano, E.; Fonseca, C. Wild boar as a reservoir of antimicrobial resistance. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 135001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pittiglio, C.; Khomenko, S.; Beltran-Alcrudo, D. Wild boar mapping using population-density statistics: From polygons to high resolution raster maps. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193295. [Google Scholar]

- Kujat Choy, S.; Neumann, E.-M.; Romero-Barrios, P.; Tamber, S. Contribution of Food to the Human Health Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2023, 21, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelloni, F.; Cilia, G.; Bogi, S.; Ebani, V.V.; Turini, L.; Nuvoloni, R.; Cerri, D.; Fratini, F.; Turchi, B. Pathotypes and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Escherichia coli Isolated from Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) in Tuscany. Animals 2020, 10, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilia, G.; Turchi, B.; Fratini, F.; Bilei, S.; Bossù, T.; De Marchis, M.L.; Cerri, D.; Pacini, M.I.; Bertelloni, F. Prevalence, Virulence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Salmonella spp., Yersinia enterocolitica and Listeria monocytogenes in European Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) Hunted in Tuscany (Central Italy). Pathogens 2021, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.; Fonseca, C.; Mendo, S.; Caetano, T. A closer look on the variety and abundance of the faecal resistome of wild boar. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, F.; Domingues, C.P.F.; Rebelo, J.S.; Monteiro, F.; Nogueira, T. The Impact of Non-Pathogenic Bacteria on the Spread of Virulence and Resistance Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzy, M.F.; Murru, N.; Smaldone, G.; Proroga, Y.T.R.; Cristiano, D.; Fioretti, A.; Anastasio, A. Hygiene evaluation and microbiological hazards of hunted wild boar carcasses. Food Control 2022, 135, 108782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. EUCAST Disk Diffusion Method for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Document Version ed.; European Committeee on Antibiotic Susceptibility: Växjö, Sweden, 2023; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters; Version n 15.0; European Committeee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing: Växjö, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Chicco, D.; Sichenze, A.; Jurman, G. A simple guide to the use of Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, Chi-squared test, and Kruskal-Wallis test in biostatistics. BioData Min. 2025, 18, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Rathinavelu, S.; Zavros, Y.; Merchant, J.L. Acinetobacter lwoffii infection and gastritis. Microbes Infect. 2003, 5, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas, M.Y.; Oguz, M.M.; Ceri, M. Acinetobacter lwoffii peritonitis in a patient on automated peritoneal dialysis: A case report and review of the literature. Case Rep. Nephrol. 2017, 2017, 5760254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Extensively drug-resistant Alcaligenes faecalis infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzanera, M.; Narváez-Reinaldo, J.J.; García-Fontana, C.; Vílchez, J.I.; González-López, J. Genome Sequence of Arthrobacter koreensis 5J12A, a Plant Growth-Promoting and Desiccation-Tolerant Strain. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e00648-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Date, J.; Takeno, T.; Watanabe, S.; Oda, A. Antimicrobial therapy using vancomycin and therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in patient with bacteremia caused by Arthrobacter woluwensis:a case report. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci. 2025, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haque, M.A.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Hossen, F.; Islam, M.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Siddique, N.; He, C.; Ahmed, F. Bacillus spp. Contamination: A Novel Risk Originated From Animal Feed to Human Food Chains in South-Eastern Bangladesh. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 783103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baindara, P.; Aslam, B. Editorial: Bacillus spp.—Transmission, pathogenesis, host-pathogen interaction, prevention and treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1307723. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.Y.; Yang, J.; Ko, J.-H.; Cho, S.Y.; Huh, K.; Chung, D.R.; Peck, K.R.; Ko, K.S.; Kang, C.-I. Extensively drug-resistant Enterobacter ludwigii co-harbouring MCR-9 and a multicopy of blaIMP-1 in South Korea. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 36, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schechner, V.; Levytskyi, K.; Shalom, O.; Yalek, A.; Adler, A. A hospital-wide outbreak of IMI-17-producing Enterobacter ludwigii in an Israeli hospital. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2021, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.-e.-Z.; Zaheer, R.; Zovoilis, A.; McAllister, T.A. Enterococci as a One Health indicator of antimicrobial resistance. Can. J. Microbiol. 2024, 70, 303–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivertsen, A.; Dyrhovden, R.; Tellevik, M.G.; Bruvold, T.S.; Nybakken, E.; Skutlaberg, D.H.; Skarstein, I.; Kommedal, Ø. Escherichia marmotae—A Human Pathogen Easily Misidentified as Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0203521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, N.; Zishiri, O.T. Presence, Pathogenicity, Antibiotic Resistance, and Virulence Factors of Escherichia coli: A Review. Bacteria 2025, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Liang, Q.; Zong, R.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, C.; Yang, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, D.; Duan, H.; Du, W.; et al. Isolation, Identification, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Exiguobacterium mexicanum from a Giraffe. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zheng, J.; Peng, D.; Sun, M. Complete genome sequence of Fictibacillus arsenicus G25-54, a strain with toxicity to nematodes. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 241, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borker, S.S.; Thakur, A.; Kumar, S.; Kumari, S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, S. Comparative genomics and physiological investigation supported safety, cold adaptation, efficient hydrolytic and plant growth-promoting potential of psychrotrophic Glutamicibacter arilaitensis LJH19, isolated from night-soil compost. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 307. [Google Scholar]

- Sutthiwong, N.; Sukdee, P.; Lekhavat, S.; Dufossé, L. Identification of Red Pigments Produced by Cheese-Ripening Bacterial Strains of Glutamicibacter arilaitensis Using HPLC. Dairy 2021, 2, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.; Graça, A.L.; Gonçalves, G.; Carvalho, A.C. Kocuria rhizophila Infection: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e86788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziogou, A.; Giannakodimos, I.; Giannakodimos, A.; Baliou, S.; Ioannou, P. Kocuria Species Infections in Humans-A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayet, S.; Lang, S.; Garnier, P.; Pierron, A.; Plantin, J.; Toko, L.; Royer, P.Y.; Villemain, M.; Klopfenstein, T.; Gendrin, V. Leclercia adecarboxylata as Emerging Pathogen in Human Infections: Clinical Features and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdács, M.; Ábrók, M.; Lázár, A.; Terhes, G.; Burián, K. Leclercia adecarboxylata as an emerging pathogen in human infections: A 13-year retrospective analysis in Southern Hungary. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 2020, 14, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, L.M.; Pierneef, R.; Mafuna, T.; Magwedere, K.; Matle, I. Genus-wide genomic characterization of Macrococcus: Insights into evolution, population structure, and functional potential. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1181376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanchaithong, P.; Perreten, V.; Schwendener, S. Macrococcus canis contains recombinogenic methicillin resistance elements and the mecB plasmid found in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 2531–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, H.-J. Review of the taxonomy of the genus Arthrobacter, emendation of the genus Arthrobacter sensu lato, proposal to reclassify selected species of the genus Arthrobacter in the novel genera Glutamicibacter gen. nov., Paeniglutamicibacter gen. nov., Pseudoglutamicibacter gen. nov., Paenarthrobacter gen. nov. and Pseudarthrobacter gen. nov., and emended description of Arthrobacter roseus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Díaz, J.; Escobar-Zepeda, A.; Adaya, L.; Rojas-Vargas, J.; Cuervo-Amaya, D.H.; Sánchez-Reyes, A.; Pardo-López, L. Paenarthrobacter sp. GOM3 Is a Novel Marine Species With Monoaromatic Degradation Relevance. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 713702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; K, C.N.; Bastola, C.; Jahir, T.; Risal, R.; Thapa, S.; Enriquez, D.; Schmidt, F. Pantoea agglomerans: An Elusive Contributor to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbation. Cureus 2021, 13, e18562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz Andrea, T.; Cazacu Andreea, C.; Allen Coburn, H. Pantoea agglomerans, a Plant Pathogen Causing Human Disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 1989–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfadadny, A.; Ragab, R.F.; AlHarbi, M.; Badshah, F.; Ibáñez-Arancibia, E.; Farag, A.; Hendawy, A.O.; De los Ríos-Escalante, P.R.; Aboubakr, M.; Zakai, S.A.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Navigating clinical impacts, current resistance trends, and innovations in breaking therapies. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1374466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, W.; Carvalhaes, C.G.; Cayô, R.; Gales, A.C.; Pignatari, A.C. Co-transmission of Rahnella aquatilis between hospitalized patients. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 19, 648–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tash, K. Rahnella aquatilis bacteremia from a suspected urinary source. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 2526–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mo, S.; Li, H.; Yang, R.; Liu, X.; Xing, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, L. Rothia nasimurium as a Cause of Disease: First Isolation from Farmed Chickens. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 653. [Google Scholar]

- Obi, C.A.; Egbuche, O.; Nwokike, S.I.; Mezue, K.; Abe, T.; Bulsara, K.; Olanipekun, T.; Onuorah, I. Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator Lead Infective Endocarditis Due to Rothia Specie: A Rare Case in An Immunocompetent Man. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.-J.; Kim, B.; Kim, Y.-e.; Lee, Y.; Pai, H. A Case of Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis with Cerebral Hemorrhage Caused by Rothia mucilaginosa. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 23, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.Y.C.; Bae, J.S.; Otto, M. Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence 2021, 12, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlet, C.P.; Brown, M.M.; Horswill, A.R. Commensal Staphylococci Influence Staphylococcus aureus Skin Colonization and Disease. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannes-Costa, P.S.; de Oliveira, J.S.S.; da Silva Santos, G.; Nagao, P. A current review of pathogenicity determinants of Streptococcus sp. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 1600–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocera, F.P.; Ferrara, G.; Scandura, E.; Ambrosio, M.; Fiorito, F.; De Martino, L. A Preliminary Study on Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Staphylococcus spp. and Enterococcus spp. Grown on Mannitol Salt Agar in European Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) Hunted in Campania Region-Italy. Animals 2021, 12, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercato, A.; Cortimiglia, C.; Abualsha’ar, A.; Piazza, A.; Marchesini, F.; Milani, G.; Bonardi, S.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Migliavacca, R. Wild Boars as an Indicator of Environmental Spread of ESβL-Producing Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 838383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowska, E. Antibiotic Resistance in the Farming Environment. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, E.; Cerino, P.; Triassi, M.; Di Duca, F.; Porreca, A.; Russo, I.; Scippa, S.; Venuta, A.; Coppola, A.; Pizzolante, A. Contamination assessment and risk evaluation of organophosphorus pesticides in groundwater: A study on contamination patterns and implications. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabença, C.; Romero-Rivera, M.; Barbero-Herranz, R.; Sargo, R.; Sousa, L.; Silva, F.; Lopes, F.; Abrantes, A.C.; Vieira-Pinto, M.; Torres, C.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli from Fecal Samples of Wild Animals. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, T.; Kramer-Schadt, S.; Fuhrmann, M.; Belik, V. Environmental factors associated with the prevalence of ESBL/AmpC-producing Escherichia coli in wild boar (Sus scrofa). Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 980554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napit, R.; Gurung, A.; Poudel, A.; Chaudhary, A.; Manandhar, P.; Sharma, A.N.; Raut, S.; Pradhan, S.M.; Joshi, J.; Poyet, M.; et al. Metagenomic analysis of human, animal, and environmental samples identifies potential emerging pathogens, profiles antibiotic resistance genes, and reveals horizontal gene transfer dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.G.J.; Flach, C.-F. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECDC. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales, Third Update; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 3 February 2025.

- Husna, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Badruzzaman, A.; Sikder, M.H.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.T.; Alam, J.; Ashour, H.M. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL): Challenges and opportunities. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega, M.; Andriani, L.; Cavallo, S.; Bonilauri, P.; Bonardi, S.; Conter, M.; Carmosino, I.; Bacci, C. Antimicrobial Resistant E. coli in Pork and Wild Boar Meat: A Risk to Consumers. Foods 2022, 11, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, R.; Tayh, G.; Srairi, S.; Mamlouk, A.; Ben Chehida, F.; Lahmar, S.; Bouslama, M.; Daaloul-Jedidi, M.; Messadi, L. Prevalence, risk factors and emergence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing-, carbapenem- and colistin-resistant Enterobacterales isolated from wild boar (Sus scrofa) in Tunisia. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 163, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pătrînjan, R.T.; Morar, A.; Ban-Cucerzan, A.; Popa, S.A.; Imre, M.; Morar, D.; Imre, K. Systematic Review of the Occurrence and Antimicrobial Resistance Profile of Foodborne Pathogens from Enterobacteriaceae in Wild Ungulates Within the European Countries. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmann, A.R.; Meemken, D.; Müller, A.; Seinige, D.; Büttner, K.; Failing, K.; Kehrenberg, C. Wild Boars Carry Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase- and AmpC-Producing Escherichia coli. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 367. [Google Scholar]

- Bonardi, S.; Cabassi, C.S.; Longhi, S.; Pia, F.; Corradi, M.; Gilioli, S.; Scaltriti, E. Detection of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase producing Escherichia coli from mesenteric lymph nodes of wild boars (Sus scrofa). Ital. J. Food Saf. 2018, 7, 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Korczak, L.; Majewski, P.; Iwaniuk, D.; Sacha, P.; Matulewicz, M.; Wieczorek, P.; Majewska, P.; Wieczorek, A.; Radziwon, P.; Tryniszewska, E. Molecular mechanisms of tigecycline-resistance among Enterobacterales. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1289396. [Google Scholar]

- Poeta, P.; Costa, D.; Igrejas, G.; Rodrigues, J.; Torres, C. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in faecal enterococci from wild boars (Sus scrofa). Vet. Microbiol. 2007, 125, 368–374. [Google Scholar]

- Akwongo, C.J.; Borrelli, L.; Houf, K.; Fioretti, A.; Peruzy, M.F.; Murru, N. Antimicrobial resistance in wild game mammals: A glimpse into the contamination of wild habitats in a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Cinthi, M.; Coccitto, S.N.; Massacci, F.R.; Albini, E.; Binucci, G.; Gobbi, M.; Tentellini, M.; D’Avino, N.; Ranucci, A.; Papa, P.; et al. Genomic analysis of enterococci carrying optrA, poxtA, and vanA resistance genes from wild boars, Italy. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 135, lxae193. [Google Scholar]

- Smoglica, C.; Vergara, A.; Angelucci, S.; Festino, A.R.; Antonucci, A.; Marsilio, F.; Di Francesco, C.E. Evidence of Linezolid Resistance and Virulence Factors in Enterococcus spp. Isolates from Wild and Domestic Ruminants, Italy. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.B.; Lim, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Lee, G.Y.; Park, K.T.; Yang, S.-J. Genetic characteristics and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from pig farms in Korea: Emergence of cfr-positive CC398 lineage. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 503. [Google Scholar]

- Leão, C.; Clemente, L.; Cara d’Anjo, M.; Albuquerque, T.; Amaro, A. Emergence of Cfr-Mediated Linezolid Resistance among Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (LA-MRSA) from Healthy Pigs in Portugal. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1439. [Google Scholar]

- Lienen, T.; Grobbel, M.; Tenhagen, B.-A.; Maurischat, S. Plasmid-Coded Linezolid Resistance in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Food and Livestock in Germany. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, I.N.; Lozano, C.; Juárez-Fernández, G.; Höfle, U.; Simón, C.; Rueda, S.; Martínez, A.; Álvarez-Martínez, S.; Eguizábal, P.; Martínez-Cámara, B.; et al. Nasotracheal enterococcal carriage and resistomes: Detection of optrA-, poxtA- and cfrD-carrying strains in migratory birds, livestock, pets, and in-contact humans in Spain. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccioni, G.; Di Cesare, A.; Sabatino, R.; Corno, G.; Mangiaterra, G.; Marchis, D.; Citterio, B. Occurrence and Transfer by Conjugation of Linezolid-Resistance Among Non-Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium in Intensive Pig Farms. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Cai, C.; Dong, N.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Cai, J. Mapping the widespread distribution and transmission dynamics of linezolid resistance in humans, animals, and the environment. Microbiome 2024, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Long, X.; Wang, M.; Ma, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, W.; Yue, M.; Yang, H.; Pan, D.; Tang, B. Transmission of linezolid-resistant Enterococcus isolates carrying optrA and poxtA genes in slaughterhouses. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1179078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembicka, K.M.; Powell, J.; O’Connell, N.H.; Hennessy, N.; Brennan, G.; Dunne, C.P. Prevalence of linezolid-resistant organisms among patients admitted to a tertiary hospital for critical care or dialysis. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 191, 1745–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.J.; Nizhu, L.N.; Rabbani, R. Bloodstream infection with pandrug-resistant Alcaligenes faecalis treated with double-dose of tigecycline. IDCases 2019, 18, e00600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, K.K.; Singh, C.K.; Kumar, M.; Singh, D.K. Whole-genome sequencing of Alcaligenes sp. strain MMA: Insight into the antibiotic and heavy metal resistant genes. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1144561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, W.; Dong, R.; Liang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, W.; Ji, B.; Tian, G.; et al. Genomic and resistome analysis of Alcaligenes faecalis strain PGB1 by Nanopore MinION and Illumina Technologies. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-García, F.; Gil-Gil, T.; Laborda, P.; Ochoa-Sánchez, L.E.; Martínez, J.L.; Hernando-Amado, S. Coming from the Wild: Multidrug Resistant Opportunistic Pathogens Presenting a Primary, Not Human-Linked, Environmental Habitat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwich, L.; Molina-López, R.A. The environmental watchdogs: Wildlife as sentinels of antimicrobial resistance pollution in the environment in Catalonia. Metode Sci. Stud. J. 2023, 13, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Araújo, S.; Caniça, M.; Pereira, J.E.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. Caught in the ESKAPE: Wildlife as Key Players in the Ecology of Resistant Pathogens in a One Health Context. Diversity 2025, 17, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Meza, M.E.; Galarde-López, M.; Carrillo-Quiróz, B.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M. Antimicrobial resistance: One Health approach. Vet. World 2022, 15, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brdová, D.; Ruml, T.; Viktorová, J. Mechanism of staphylococcal resistance to clinically relevant antibiotics. Drug Resist. Updates 2024, 77, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Bell, T.; Lee, K.; Jeong, J.; Bardwell, J.C.A.; Lee, C. Identification of host genetic factors modulating β-lactam resistance in Escherichia coli harbouring plasmid-borne β-lactamase through transposon-sequencing. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2493921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.