Abstract

Background: Canine skin and ear infections are common in small-animal practice and increasingly complicated by multidrug resistance (MDR), yet data from Serbia are limited. This study aimed to describe the bacterial etiology and antimicrobial resistance patterns in canine otitis externa and pyoderma. Methods: We retrospectively reviewed laboratory records from the Clinical Bacteriology and Mycology Laboratory, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Belgrade (January 2017–August 2024). A total of 422 non-invasive swabs from clinically ill dogs were included (ears: n = 210; skin: n = 212). Bacterial identification used conventional methods and commercial systems, and disk-diffusion susceptibility testing followed CLSI/EUCAST guidance. Methicillin resistance in staphylococci was assessed by cefoxitin/oxacillin screening; MRSA was confirmed by PCR and PBP2a detection. Resistance trends were compared between 2017–2020 and 2021–2024. Results: The leading pathogens were Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (ears 48.1%; skin 79.7%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ears 29.1%; skin 7.6%). Staphylococci showed high resistance to macrolides, clindamycin, tetracycline, and first-line β-lactams (amoxicillin–clavulanate, cephalexin), with the highest susceptibilities to amikacin, florfenicol, and rifampicin. P. aeruginosa remained most susceptible to amikacin, polymyxin B, and imipenem. Between the two periods, S. pseudintermedius resistance increased to amikacin, fusidic acid, and cephalexin, while resistance to florfenicol decreased. P. aeruginosa resistance to imipenem increased. The prevalence of methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) was 27.4% (74/270). MDR S. pseudintermedius and MDR P. aeruginosa were identified in 38.5% and 53.3% of isolates, respectively. One isolate of each species was resistant to all tested drugs. Conclusions: These findings confirm high levels of antimicrobial resistance in major canine skin and ear pathogens and emphasize the need for susceptibility-based therapy, rational antimicrobial use, and ongoing surveillance in small-animal practice.

1. Introduction

Bacterial skin and ear infections are among the most common conditions in small animal veterinary practices [1,2]. Skin infections may present with mild erythema and pruritus or progress to deep, painful, or ulcerative lesions, while otitis externa (OE) may range from mild erythema and ceruminous discharge to chronic, painful, or proliferative disease. These infections are typically caused by the skin and ear microbiota of dogs and cats and most often occur as secondary complications. Moderate to severe or recurrent cases are usually triggered by stress, dietary changes, or underlying pathological conditions, including atopic dermatitis, allergies, endocrinopathies, ectoparasites, foreign bodies, and anatomical abnormalities [1,2,3]. Such events, combined with breed susceptibility and other predisposing factors, create favorable conditions for colonization by opportunistic pathogens [1,2].

The most commonly isolated causative agents in canine skin and ear infections are S. pseudintermedius, S. aureus, Streptococcus canis, P. aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Proteus spp., with Malassezia pachydermatis frequently found in cases of OE [1]. These infections not only cause significant discomfort and pain in affected animals [4], but they also pose a public health concern [1,2]. The increase in the global companion animal population, especially of dogs, further amplifies this risk, as dogs can serve as reservoirs for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) determinants, transmissible through direct or indirect contact [5]. The close relationship between pets and their owners may favor such transmission [1].

The development of AMR in bacterial pathogens and the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) microorganisms have profound implications for both veterinary and public health. Dogs carrying MDR pathogens are at an increased risk of failed treatment regimens, with severe cases requiring last-resort surgical interventions [2]. Despite these challenges, empirical antibiotic prescription without prior susceptibility testing remains common in veterinary medicine, particularly in developing countries such as Serbia, creating conditions that favor the selection and dissemination of resistant strains [1].

Given the significance of MDR bacterial strains, it is crucial to maintain updated knowledge about the pathogens implicated in canine skin and ear infections and their resistance patterns. Regular monitoring and temporal analysis are essential for designing effective control strategies, improving treatment outcomes, and enabling evidence-based therapies. Therefore, the aim of this study is to highlight the importance of routine microbiological diagnostics by analyzing data collected over eight years at the Laboratory for Clinical Bacteriology and Mycology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (FVM), University of Belgrade. Additionally, it evaluates antibiotic resistance profiles, highlighting the high prevalence of MDR strains and helps inform appropriate antibiotic use and control measures.

2. Results

In this retrospective study, a total of 422 samples from cases of canine ear (n = 210) and skin (n = 212) infections were analyzed. The number of bacterial skin infections was nearly identical to the number of OE cases.

In canine ear samples, S. pseudintermedius was the most commonly identified bacterium (101/210; 48.10%), followed by P. aeruginosa (61/210; 29.05%). S. aureus was isolated from 18 swabs (18/210; 8.57%), and other staphylococci were found in 16 swabs (16/210; 7.62%). Among the other staphylococci, the following species were identified: S. coagulans from 1 swab (0.48%), S. haemolyticus from 3 swabs (1.43%), and S. epidermidis from 12 swabs (5.71%). Streptococcus Lancefield group G (presumptive S. canis) was isolated from 23 swabs (23/210; 10.95%). Proteus spp. was isolated from 39 samples (39/210; 18.57%), comprising P. vulgaris in 9 swabs (9/210; 4.29%) and P. mirabilis in 30 swabs (30/210; 14.29%). The prevalence of Enterobacterales was 4.29% (9/210) and the following species were identified: Escherichia coli in 4 cases (4/210; 1.90%), Klebsiella pneumoniae in 4 swabs (4/210; 1.90%), and Serratia marcescens in 1 swab (1/210; 0.48%). Other bacteria identified included Corynebacterium sp. in 17 swabs (17/210; 8.10%), and a single isolate of Pseudomonas sp. (other than P. aeruginosa) (0.48%). These bacteria were identified as causative agents of OE in dogs (Table 1). Of the 210 ear swabs, 69 (32.86%) showed mixed bacterial infections caused by two or more bacteria.

Table 1.

Bacterial isolates from canine ear and skin infections.

Regarding canine skin samples, S. pseudintermedius was the most commonly identified bacterium (169/212; 79.72%), followed by S. aureus (22/212; 10.38%). Other staphylococci were isolated from 10 swabs (10/212; 4.72%) represented by the following species: S. coagulans (4/212; 1.89%), S. epidermidis (4/212; 1.89%), and S. haemolyticus (2/212; 0.94%). Beta-hemolytic Streptococcus Lancefield group G was isolated from 18 swabs (18/212; 8.49%). P. aeruginosa was isolated from 16 swabs (16/212; 7.55%). Proteus spp. was isolated from 18 samples (18/212; 8.49%), comprising P. vulgaris in 8 swabs (8/212; 3.77%) and P. mirabilis in 10 swabs (10/212; 4.72%). Among the Enterobacterales, E. coli was the only isolated species in 11 cases (11/212; 5.19%). Other identified bacteria included Corynebacterium sp. in 3 swabs (3/212; 1.42%) and Pseudomonas sp. (other than P. aeruginosa) in 2 swabs (2/212; 0.94%) (Table 1). Compared to cases of OE, mixed bacterial infections were less common in skin samples, with 52 out of 212 skin swabs (24.53%) showing mixed infections caused by two or rarely three bacteria.

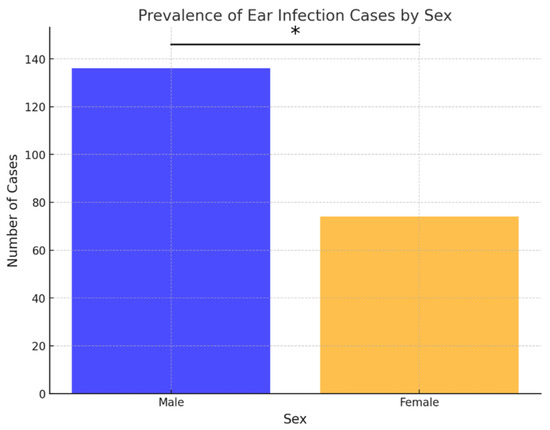

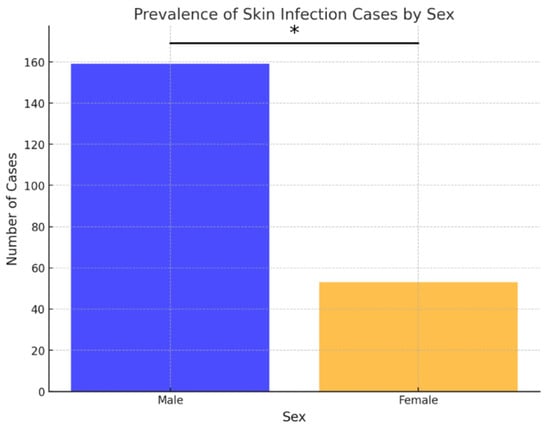

Out of the 210 ear samples, 136 (64.76%) were from males, and 74 (35.24%) were from females. Similarly, in cases of skin infections, 159 out of 212 samples (75%) were from males, and 53 (25%) were from females. Over the examined 8-year period, the frequency of both skin and ear infections was statistically higher in males compared to females (p < 0.05) (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of ear infection cases by sex. Asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference between sexes (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of skin infection cases by sex. Asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference between sexes (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05).

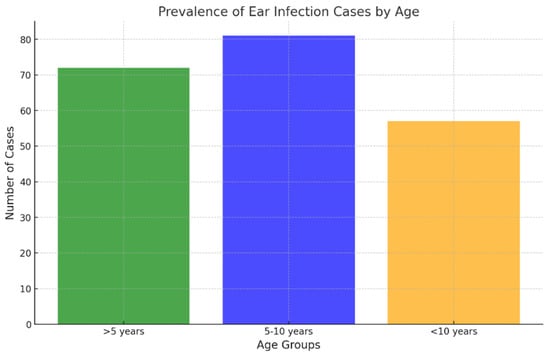

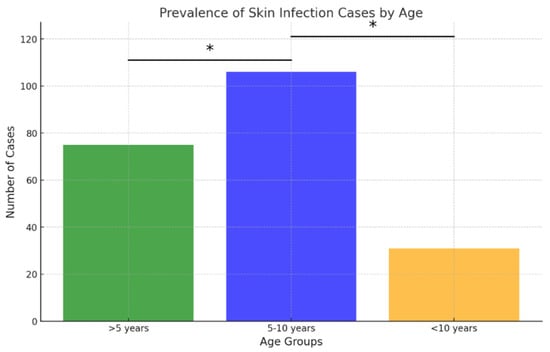

Regarding age distribution, the 5–10-year age group accounted for the largest proportion of samples (81/210; 38.57% of ear samples and 106/212; 50% of skin samples), followed closely by dogs younger than 5 years (72/210; 34.29% of ear samples and 75/212; 35.38% of skin samples) (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The 5–10 age group showed statistically higher infection rates for skin infections (p < 0.05), while no statistically significant differences in infection rates were observed for ear infections.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of ear infection cases by age.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of skin infection cases by age. Asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference between age groups (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05).

In cases of OE, a total of 47 different dog breeds were identified. The most frequently observed breed was the West Highland White Terrier (n = 32; 15.24%), followed by the Labrador Retriever (n = 14; 6.67%), English Bulldog and English Cocker Spaniel (n = 12 each; 5.71%), Golden Retriever and mixed breeds (n = 10 each; 4.76%), Shar Pei and Pug (n = 9 each; 4.29%), and Bichon Frisé, Poodle, and French Bulldog (n = 8 each; 3.81%). In cases of skin infections, a total of 35 different dog breeds were identified. The most frequently observed breed was the American Staffordshire Terrier (n = 37; 17.45%), followed by the Bull Terrier (n = 23; 10.85%), English Bulldog (n = 20; 9.43%), Doberman Pinscher (n = 16; 7.55%), German Shepherd and mixed breeds (n = 13 each; 6.13%), French Bulldog (n = 10; 4.72%), and West Highland White Terrier and Boxer (n = 8 each; 3.77%). Other breeds were represented in smaller numbers (fewer than 8 individuals).

2.1. Overall Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile

The antimicrobial susceptibility results are presented separately for six examined bacterial groups and are summarized in Table 2. The following results represent the overall antibiotic susceptibility profile of all isolates collected during the entire 2017–2024 study period. Pairwise comparisons were performed to evaluate differences in susceptibility proportions among antibiotics within the same timeframe. Temporal trends in resistance between the two study periods (2017–2020 vs. 2021–2024) are presented separately in Figure 5.

Table 2.

Distribution of antimicrobial susceptibility profiles among the most prevalent bacterial pathogens.

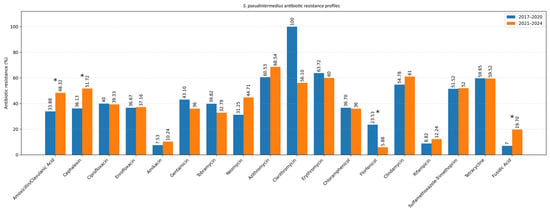

Figure 5.

Resistance profile of S. pseudintermedius (Comparison of the 2017–2020 and 2021–2024 periods). Asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05).

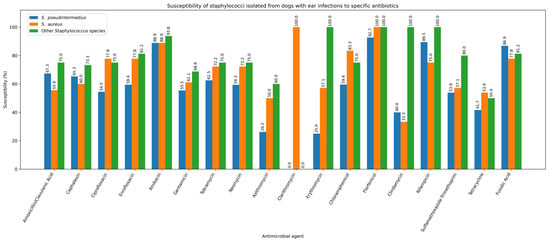

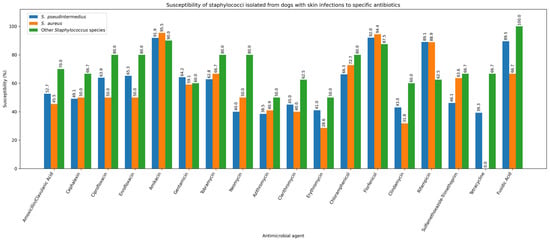

Across staphylococcal species, the highest resistance rates were observed in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius for the macrolides azithromycin (130/203; 64.0%) and erythromycin (96/153; 62.7%)—and for tetracycline (93/156; 59.6%), whereas the greatest susceptibility was recorded for florfenicol (157/170; 92.4%) and amikacin (235/259; 90.7%), with similarly high values for rifampicin (148/166; 89.2%) and fusidic acid (146/166; 88.0%). Pairwise comparisons confirmed that amikacin had higher susceptible fractions than gentamicin (162/266; 60.9%; p < 0.0001), tobramycin (109/174; 62.6%; p < 0.0001) and neomycin (58/101; 57.4%; p < 0.0001), while florfenicol showed higher susceptibility than β-lactams and fluoroquinolones (vs amoxicillin/clavulanate 157/270; 58.1%; p < 0.0001; vs. ciprofloxacin 163/270; 60.4%; p < 0.0001) and macrolides and tetracycline (all p < 0.0001). Chloramphenicol susceptibility rates (167/262; 63.7%) were significantly higher than those of clarithromycin (18/43; 41.9%; p = 0.0001), erythromycin (p < 0.0001), clindamycin (91/215; 42.3%; p < 0.0001), sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim (113/234; 48.3%; p = 0.0006) and tetracycline (p < 0.0001). In Staphylococcus aureus, amikacin had higher susceptibility rates than β-lactams (p < 0.0001; p = 0.0002), fluoroquinolones (both p = 0.0025), macrolides (p < 0.0001–0.0003), SXT (p = 0.0026) and tetracycline (p < 0.0001), while florfenicol showed higher susceptibility than β-lactams (both p < 0.0001), fluoroquinolones (p = 0.0002), macrolides (all p < 0.0001), SXT (p < 0.0001), tetracycline (p = 0.0217) and chloramphenicol (p = 0.01). Chloramphenicol had higher susceptibility than amoxicillin/clavulanate (p = 0.0193), cephalexin (p = 0.0438), macrolides (p = 0.0066–0.0253), SXT (p = 0.0006) and tetracycline (p = 0.0133). In other staphylococci, florfenicol (23/24; 95.8%) and amikacin (24/26; 92.3%) were most active, and pairwise analysis showed that amikacin exceeded gentamicin (p = 0.0385), azithromycin (p = 0.0065) and SXT (p = 0.0161), while florfenicol exceeded cephalexin (p = 0.0479), azithromycin (p = 0.0026), SXT (p = 0.0037) and clindamycin (p = 0.0258). Among β-hemolytic Streptococcus group G, the highest susceptibility was observed for florfenicol (27/28; 96.4%), chloramphenicol (38/41; 92.7%), cephalexin (36/39; 92.3%), rifampicin (12/13; 92.3%) and amoxicillin/clavulanate (37/41; 90.2%), while the lowest occurred for ciprofloxacin (46.3%), enrofloxacin (48.8%), SXT (34.4%), tetracycline (25.0%) and fusidic acid (35.7%). For this species, β-lactams had higher susceptibility than fluoroquinolones (all p < 0.0001) and clindamycin (p = 0.0390; p = 0.0291), while chloramphenicol and florfenicol exceeded fluoroquinolones and all low-performing classes (all p < 0.0001); chloramphenicol also exceeded erythromycin (p = 0.0385) and clindamycin (p = 0.0153). In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the highest susceptibility was observed for amikacin (69/76; 90.8%), polymyxin B (60/67; 89.6%), imipenem (48/54; 88.9%), enrofloxacin (83.1%), ciprofloxacin (81.8%), gentamicin (80.7%) and tobramycin (80.6%), while florfenicol was significantly lower (29/59; 49.2%), with pairwise comparisons confirming its lower susceptibility rates versus ciprofloxacin (p = 0.0054), enrofloxacin (p = 0.0029), amikacin (p < 0.0001), gentamicin (p = 0.0068), tobramycin (p = 0.0091), polymyxin B (p = 0.0003) and imipenem (p = 0.0008). In Proteus mirabilis, imipenem showed the highest susceptibility (26/26; 100%), followed by amikacin (92.5%), gentamicin (86.0%), ciprofloxacin (84.2%), enrofloxacin (84.2%), tobramycin (81.6%), neomycin (77.5%) and cephalexin (64.8%), whereas florfenicol (65.3%), amoxicillin/clavulanate (63.2%), chloramphenicol (59.6%), SXT (51.1%) and tetracycline (48.9%) showed lower values; imipenem exceeded all lower-performing drugs (p = 0.0003–0.0232), and amikacin exceeded β-lactams, chloramphenicol, florfenicol, SXT and tetracycline (p = 0.0003–0.0075).

2.2. Temporal Trends in Antimicrobial Resistance (2017–2024)

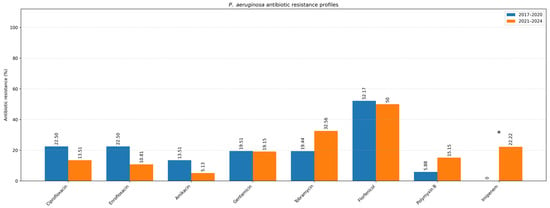

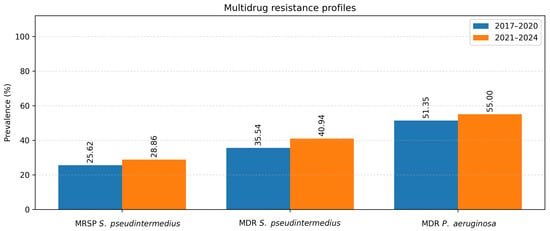

To evaluate temporal changes in antimicrobial resistance, data were compared between two study periods: 2017–2020 and 2021–2024 (Table 3). The analysis focused on the two most common pathogens isolated from canine ear and skin infections, S. pseudintermedius and P. aeruginosa. For S. pseudintermedius, resistance to several antibiotics significantly increased in the later period. Notably, resistance to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid and fusidic acid showed a statistically significant increase (p < 0.05), observed among both methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible isolates. A similar upward trend was noted for cephalexin (p < 0.05), corresponding to the rising proportion of methicillin-resistant isolates. In contrast, a statistically significant decrease in resistance to florfenicol was observed (p < 0.05) (Figure 5). Resistance to macrolides (azithromycin, erythromycin, clarithromycin) and tetracycline remained high but relatively stable across both periods, indicating sustained selective pressure within these antimicrobial classes. For P. aeruginosa, a significant increase in resistance to imipenem was recorded in 2021–2024 compared to 2017–2020 (p < 0.05) (Figure 6). Resistance levels to other antipseudomonal agents such as amikacin and polymyxin B remained largely unchanged, suggesting that carbapenem resistance is emerging as the most dynamic concern within this species. Regarding methicillin-resistant and multidrug-resistant phenotypes, the prevalence of MRSP (27.4%) and MDR S. pseudintermedius (38.5%) did not change significantly between periods (p > 0.05). Similarly, no significant variation was observed for MDR P. aeruginosa isolates (53.3%) (p > 0.05) (Figure 7).

Table 3.

The percentages of methicillin-resistant staphylococci (MRS) and multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria during the 2017–2024 period.

Figure 6.

Resistance profile of P. aeruginosa (Comparison of the 2017–2020 and 2021–2024 periods). Asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

MRSP, MDR S. pseudintermedius and MDR P. aeruginosa.

One strain of S. pseudintermedius (1/270; 0.37%) and one strain of P. aeruginosa (1/77; 1.30%) were resistant to all tested antibiotics. S. pseudintermedius was isolated from the skin, while P. aeruginosa was isolated from the external ear canal. Given that staphylococci are the predominant pathogens in canine skin and ear infections, Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of staphylococcal isolates obtained from ear and skin samples.

Figure 8.

Susceptibility of staphylococci isolated from dogs with ear infections to specific antibiotics.

Figure 9.

Susceptibility of staphylococci isolated from dogs with skin infections to specific antibiotics.

3. Discussion

A thorough understanding of pathogen distribution, along with up-to-date antimicrobial susceptibility data, is essential for effectively managing OE and skin infections in both human and veterinary medicine [2]. In this study, Staphylococcus spp., P. aeruginosa, Proteus spp., and Streptococcus spp. were the most frequently isolated bacteria, which aligns with previous reports [1,6,7,8,9]. Our findings further confirm the role of S. pseudintermedius as the main causative agent of canine skin infections [1,2,8]. Other authors have also reported a high prevalence of this bacterium, ranging from 39.2% to 58.8% [1,10,11] for OE cases and 50.0% to 84.7% [12,13] for skin infection cases. The high rate of colonization with Staphylococcus spp. in dogs may pose a potential public health concern. For example, S. coagulans and S. aureus are associated with a broad spectrum of diseases in both humans and animals [14,15]. Although the detected low prevalence of S. aureus in our samples aligns with other available studies, their capacity to harbor antimicrobial resistance mechanisms underscores the importance of monitoring their role in canine infections and public health implications [2,16,17].

P. aeruginosa was the second most commonly isolated bacterium from canine ear samples, similarly to other reports [4,18]. By contrast, Bugden described this bacterium as the most frequently isolated species from canine OE samples in Australia, followed by S. pseudintermedius, linking the higher prevalence of P. aeruginosa to an increased diagnosis of chronic OE [19]. Although previous studies indicate low genetic similarity between canine and human P. aeruginosa strains, suggesting limited cross-species transmission, proper hygiene when handling animals remains important. This is supported by a 2018 report documenting zoonotic transmission of a carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa strain (VIM-2 producer) between a dog, its owner, and their household environment [20].

Proteus spp., especially P. mirabilis, were identified in our samples at a slightly higher frequency compared to other studies [1,2]. This finding underscores Proteus spp. as occasional yet noteworthy contributors to canine infections. Importantly, in all cases in this study, Proteus spp. was isolated as part of mixed infections, with at least one additional pathogen present, denoting their role as secondary pathogens. Their clinical relevance in this context lies primarily in the fact that mixed infections may complicate treatment outcomes, especially when empirical therapy lacks adequate Gram-negative coverage. Therefore, while the etiological importance of Proteus spp. is limited, their presence may contribute to persistence or recurrence of infection in predisposed cases [3,21]. High percentages of mixed infections, as noted in our study results, are clinically significant since they reduce the likelihood of successful treatment with empirical or antibiotic susceptibility-based therapy.

During the study period, ear and skin infections were predominantly observed in male dogs, similarly to some other reports [1,22]. However, sex distribution was assessed solely on a descriptive basis and was not intended to imply any causal association since the development of otitis is primarily influenced by other known factors [23].

Skin infections were most commonly diagnosed in dogs aged 5 to 10 years, consistent with findings from other studies [1]. In contrast, no statistically significant correlation between age and OE was observed. In younger dogs, otitis is frequently associated with ear mites (Otodectes cynotis) [24], while bacterial otitis is more prevalent in adult dogs. The latter often develops secondary to underlying conditions such as allergies, impaired immune function, endocrine disorders, or reduced elasticity of the skin and ear canal tissues, which predispose older dogs to bacterial infections [25]. However, some studies have reported a higher incidence of bacterial otitis in younger dogs, particularly those ≤4 years of age [18].

In our study, the West Highland White Terrier was the most common breed in otitis cases, followed by the Labrador Retriever, English Bulldog, English Cocker Spaniel, Golden Retriever, mixed breeds, and others. These findings align closely with other studies [2,18]. Although such a high incidence in the West Highland White Terrier has not been previously reported, it most likely reflects this breed’s predisposition to otitis [23] as well as its popularity in Serbia.

Antibiotic resistance has become a significant public health issue, largely driven by the improper use, overuse, and misuse of antibiotics in both human and veterinary medicine [26]. Conditions such as canine OE and bacterial skin infections are among the leading causes for prescribing antibiotics in small animal veterinary practices [1,27]. Despite the widespread use of antibiotics to treat these issues, antimicrobial susceptibility testing is rarely conducted, and treatments are often based on empirical practices rather than guided by sensitivity data [1,28]. The observed trend of increasing resistance of S. pseudintermedius to amoxicillin-clavulanate (AMC), cephalexin, and fusidic acid is not unexpected, given that broad-spectrum antibiotics are among the most frequently prescribed antimicrobials for dogs and cats [29]. Similary, data from Romania and North Macedonia similarly show β-lactam resistance in S. pseudintermedius ranging from 15.9% to 73% [30,31]. Furthermore, a study from Bulgaria noted a significant increase in resistance to AMC from 5 to 42% in coagulase-positive staphylococci from OE samples [32].

Although the prevalence of MRSP and MDR S. pseudintermedius did not show a statistically significant rise over the years, their rates remain alarmingly high. Neighboring countries report MRSP prevalence of 7.5% in Croatia [33] and 29% in Bosnia and Herzegovina [34], while our previous work also confirmed high MRSP prevalence in Serbia through mecA detection [8]. The elevated MRSP rate in this study may reflect the selection of OE and dermatitis cases, which frequently involve methicillin-resistant infections. MRSP and MDR strains with extensive resistance profiles represent a major challenge in veterinary medicine [35], and veterinary settings, such as hospitals and clinics, appear to be key hubs for their transmission between pets and humans [36].

A notable finding of this study was the persistently high resistance of Staphylococcus isolates to macrolide antibiotics and clindamycin throughout the entire study period. This pattern may reflect co-selection of erythromycin resistance during treatment with other antimicrobials. For example, the ermB gene is linked to the aadE-sat4-aphA-3 aminoglycoside-resistance cluster, meaning that use of topical aminoglycosides can inadvertently co-select for resistance to macrolides and lincosamides [37,38]. Consistent with a growing global trend of macrolide and clindamycin resistance, particularly among MRSP isolates, our findings align with ISCAID recommendations that prioritize topical therapy for canine OE and pyoderma and reserve systemic antibiotics such as cephalexin, cefadroxil, or AMC for appropriate cases, while advising against empirical use of macrolides and clindamycin in regions like ours where resistance to these classes is high [39].

Antibiotic resistance in the group ‘other staphylococci’ was significantly lower than in S. aureus and S. pseudintermedius, presumably due to the predominance of coagulase-negative staphylococci, which generally exhibit lower resistance levels compared to coagulase-positive strains [40]. However, higher resistance rates have been reported in S. coagulans [41], S. haemolyticus [42], and S. epidermidis [43]. Notably, amikacin and florfenicol emerged as two of the most effective antibiotics, with isolates showing high susceptibility, further supporting their clinical utility.

Regarding treatment efficacy, staphylococci demonstrated the highest sensitivity to amikacin, florfenicol, and rifampicin. Since OE is best managed with topical therapy [3] and neither amikacin nor rifampicin is commercially available in topical formulations, florfenicol appears most promising based on in vitro susceptibility data. Florfenicol, a synthetic derivative of thiamphenicol and chloramphenicol, inhibits bacterial protein synthesis and has documented activity against diverse Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, with additional evidence suggesting anti-inflammatory properties [44]. It is also available in Serbia as an approved otic preparation for treating canine OE.

The highest resistance rates in β-hemolytic Streptococcus were observed against SXT and tetracycline, while AMC was among the most effective antibiotics, with isolates showing high susceptibility, supporting its classification as a drug of choice for treating canine streptococcal infections [21]. Streptococcus isolates in this study showed notably high levels of resistance to fluoroquinolones, with 53.66% resistant to ciprofloxacin and 51.22% to enrofloxacin. Earlier studies (2010–2016) reported good fluoroquinolone activity [45], but research from 2017–2025 demonstrates a consistent global increase, with S. canis resistance reaching 45–60% in canine OE cases across Europe, Asia, and Latin America [46,47]. This trend is largely linked to excessive empirical use of fluoroquinolones, particularly enrofloxacin and marbofloxacin, often without susceptibility testing. Despite this, Despite this, fluoroquinolones are prescribed in 63% of S. canis cases [47].

P. aeruginosa is intrinsically resistant to numerous antibiotics, including most β-lactams and β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and chloramphenicol, and readily develops additional resistance [1]. In our study, amikacin, polymyxin B, and imipenem showed the highest activity against P. aeruginosa. Imipenem resistance was low, slightly below the 15–23% reported elsewhere [48,49], although still clinically relevant given WHO’s designation of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa as a critical priority pathogen [50]. The significant resistance of P. aeruginosa isolates from canine OE to gentamicin (19.32%) observed in this study aligns with the results reported in previous research [4,51]. Petrov et al. noted the decrease in resistance rates for AMC, while a significant increase was detected for aminoglycosides [32]. An earlier study from Croatia describes P. aeruginosa strain resistance to gentamicin (43.3%), ciprofloxacin (8.7%), and enrofloxacin (51.9%) [51]. This study did not include several key anti-pseudomonal agents (e.g., piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftazidime, aztreonam), limiting the scope of susceptibility data. Notably, P. aeruginosa showed the highest proportion of MDR strains among all tested bacteria, greatly restricting therapeutic options, as reported elsewhere [1,52].

The high resistance observed for AMC as well as to first-generation cephalosporins (cephalexin) across all isolates except Streptococcus spp. are likely influenced by the fact that, besides clindamycin, these antibiotics are commonly used as first-line treatments during empirical antibiotic prescription, contributing to the emergence of AMR [2,39]. Also, of concern is the fact that we detected variable (fluctuating) levels of resistance to fluoroquinolones given that they are classified as critically important antibiotics in human medicine [53,54]. A striking finding was the high level of resistance to tetracycline across all tested bacterial species, and it should be regarded as a poor empirical choice for the treatment of ear and skin infections in dogs, consistent with several recent reports describing similar resistance levels [30,55,56].

The prevalence of MDR strains in our examination corresponds to findings from recent reports from studies on dogs with otitis and skin infections [4,57,58]. MDR pathogens pose a significant threat to animal health by severely limiting therapeutic options and often necessitating the use of antibiotics not approved for veterinary use. These findings highlight the need to establish treatment protocols for managing canine OE and skin infections, tailored and informed by the latest research on resistance profiles of commonly isolated pathogens, as well as continuous AMR monitoring through national programs like the German GERM-Vet, the Swedish SVARM, and the French RESAPATH, which are already established in some European countries [59,60,61]. According to the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, the country has an estimated population of approximately 6.59 million inhabitants [62], while data from the Veterinary Directorate of the Republic of Serbia indicates that 1,955,289 dogs are registered in the Central Database. Additionally, around 100,000 new dogs are registered annually, and between 30,000 and 35,000 are deregistered, either due to death or export [63]. This information underscores the importance of implementing the mentioned protocols and monitoring systems in Serbia. This retrospective study provides valuable insights for clinicians, particularly in veterinary hospitals within our region and neighboring countries, to make informed decisions regarding antibiotic use, especially considering that this is the first study of its kind conducted in Serbia. Because empirical antibiotic use is still common in everyday veterinary practice, and studies show that evidence-based prescribing is often overlooked, regular susceptibility testing has become increasingly important for choosing effective treatments, preventing resistance, and improving patient outcomes [1,2]. This need is even more pronounced in recurrent cases, and our findings reinforce how essential it is to keep evaluating the bacteria involved in canine ear and skin infections so that treatment decisions remain well-informed and clinically sound. Compared to published Balkan studies that report only single-timepoint prevalence, or class-specific resistance rates, this study is the first from Serbia to offer a large-scale longitudinal analysis with statistically evaluated AMR trends for major canine skin and ear pathogens.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

This study analyzed data from the Laboratory for Clinical Bacteriology and Mycology at the Department of Microbiology and Dermatological Clinic, FVM, University of Belgrade, Serbia, covering January 2017 to August 2024. The dataset, collected from VetIS (Veterinary Information System, a nationally developed digital platform created by the Computer Centre of the Faculty of Electrical Engineering, University of Belgrade), which enables recording and tracking of veterinary data, including diagnostics, treatments, and laboratory findings, consisted of records from clinically ill canine patients diagnosed with OE and pyoderma or postsurgical wound infections at the Dermatology Clinic of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine. A total of 422 noninvasive skin and ear swab samples were collected during routine veterinary examinations conducted for diagnostic purposes. The laboratory records included essential information, such as animal identification details (name, ID number, species, breed, sex, and age), type of material collected, clinical diagnosis, sampling date, prior antibiotic use, bacterial identification, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing results. For statistical analysis, age was categorized into three groups (<5 years, 5–10 years, and >10 years). Additionally, co-infections in positive cultures were recorded (excluding fungi). Collected data were organized in Microsoft Excel before statistical analysis to ensure proper standardization. Incomplete or missing records were excluded from the study to maintain data integrity. All variables were clearly defined and cross-verified with laboratory logs to establish accuracy.

4.2. Isolation and Identification of Bacteria and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

For microbiological analysis, the samples were cultured using the following media: Columbia agar with 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), MacConkey agar (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and Sabouraud dextrose agar (HiMedia, Mumbai, India) for fungal isolation, though fungi were excluded from this study. For the rapid identification of Enterobacterales, the chromogenic HICrome UTI agar (HiMedia, Mumbai, India) was used. Conventional clinical microbiology tests were used to establish an accurate identification (Gram staining, catalase, oxidase, assessment of beta-hemolysis, biochemical properties such as indole utilization, etc.). Additional tests included the ONPG (β-galactosidase) test, mannitol test, urease test, polymyxin E susceptibility testing, and coagulase tests for differentiating staphylococci. Staphylococci were identified using the commercial ID 32 Staph system (API, BioMérieux, Lyon, France), streptococci were classified into groups using specific agglutinating sera (Microgen Bioproducts Ltd., Camberley, UK), and for Gram-negative bacteria the BBL Crystal Enteric/Nonfermentor Kit (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used.

This study analyzed the antibiotic resistance profiles of S. pseudintermedius, S. aureus, other staphylococci (grouped), Streptococcus Lancefield group G (presumptive S. canis), P. aeruginosa and P. mirabilis. Antibiotic resistance profiles of other strains were excluded from the analysis due to the limited number of isolates. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed on Mueller-Hinton agar (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) using the disk diffusion method, following CLSI and EUCAST guidelines. For staphylococci, antimicrobial susceptibility was interpreted according to CLSI VET01-A4 [64] and updated annually using CLSI M100 documents [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] for agents not covered by VET01-A4 and EUCAST guedelines [73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. For β-hemolytic streptococci, EUCAST streptococcal clinical breakpoints (versions 2017–2024) [73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80] were applied whenever available, while CLSI VET01-A4 [64] and CLSI M100 [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] were used for antibiotics lacking EUCAST values. For P. aeruginosa and P. mirabilis, EUCAST clinical breakpoints (versions 2017–2024) [73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80] were applied for all antibiotics included in EUCAST tables. For agents lacking EUCAST interpretation, particularly those used primarily in veterinary medicine, CLSI M100 [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] and CLSI VET01-A4 [64] were used. Breakpoints were updated annually throughout the 8-year study period according to the most recent documents available at the time of testing.

The results should therefore be interpreted with caution. A total of 20 antimicrobial agents were tested (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA (except for the florfenicol, purchased from Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) using the following concentrations: Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid 20 μg + 10 μg (AMC), Cefalexin 30 μg (CN), Amikacin 30 μg (AN), Gentamicin 10 μg (GM), Tobramycin 10 μg (NN), Neomycin 30 μg (N), Ciprofloxacin 5 μg (CIP), Enrofloxacin 5 μg (ENF), Erythromycin 15 μg (E), Azithromycin 15 μg (AZM), Clarithromycin 15 μg (CLR), Chloramphenicol 30 μg (C), Florfenicol 30 μg (FFC), Clindamycin 2 μg (CC), Rifampicin 5 μg (RAM), Fusidic acid 10 μg (FA), Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole 1.25 μg + 23.75 μg (SXT), Tetracycline 30 μg (TET), Imipenem 10 μg (IPM) and Polymyxin B 300 IU (PB). Due to the duration of this study and the specific characteristics of certain isolates and clinical cases, as well as considering intrinsic resistance [81] and official recommendations, not all isolates were consistently tested against every mentioned antibiotic. The number of tested isolates is provided in the study results (Table 2). Quality control of each new lot of antibiotic disks and culture media was performed according to CLSI VET01-A4 [64] and CLSI M100 [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. The potency and integrity of disks, as well as the sterility, depth, and pH of Mueller–Hinton agar, were verified before testing. Reference strains S. aureus ATCC 25923, E. coli ATCC 25922, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, and E. faecalis ATCC 29212 (Microbiologics, St. Cloud, MN, USA) were used for routine performance checks.

Methicillin resistance in staphylococci was evaluated using the disc diffusion method with cefoxitin (30 μg) (Becton Dickinson, USA) for S. aureus and oxacillin (2 μg) (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for other staphylococci [64,82,83]. Confirmation of MRSA was done by PCR using MRSA ATCC 43300 and ATCC 33591 (Microbiologics, St. Cloud, MN, USA) as positive controls, with the previously described method [84]. The mecC gene was not tested. Also, detection of PBP2a was done with the Slidex MRSA agglutination kit (bioMérieux, Lyon, France). Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as resistance to at least three distinct antibiotic classes [85]. The considered antibiotic classes were as follows: cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracycline, macrolides and amphenicoles.

4.3. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the proportions of each group, including age, sex, skin infection types, and antimicrobial drugs. Graphics were generated using R’s built-in libraries, and the frequencies of antimicrobial resistance were summarized through descriptive statistical analysis. The statistical significance between groups was evaluated using Fisher’s exact test, with a p-value < 0.05 considered significant. Statistical analysis of the experimental results was performed using the statistical software GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

5. Conclusions

Throughout the study period, S. pseudintermedius and P. aeruginosa were identified as the predominant pathogens in canine skin and ear infections. A clear upward trend in antimicrobial resistance among S. pseudintermedius isolates was observed for β-lactams, particularly amoxicillin–clavulanate and cephalexin, followed by fusidic acid and amikacin. Florfenicol demonstrated a decreasing resistance trend and remained highly effective for localized treatment of staphylococcal otitis. In contrast, tetracyclines exhibited persistently high resistance across all bacterial species, making them a poor therapeutic choice for both skin and ear infections. Resistance to macrolides and clindamycin remained consistently high throughout the period without notable fluctuation. In P. aeruginosa, a significant upward trend in resistance to imipenem was recorded in the later study years, while susceptibility to amikacin and polymyxin B remained stable. The persistently high prevalence of methicillin-resistant and multidrug-resistant S. pseudintermedius and P. aeruginosa continues to limit therapeutic options. These findings highlight the growing challenge of antimicrobial resistance in small-animal practice and the importance of routine susceptibility testing to guide rational antibiotic selection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P., D.M. and D.K.; methodology, I.P., D.M. and D.K.; validation, D.M. and D.K.; formal analysis, B.V. and V.G.; investigation, I.P., A.R., A.N., K.A., M.R., V.G., M.I., D.M., N.M.M. and D.K.; resources, N.M.M.; data curation, I.P., V.G., A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P.; writing—review and editing, D.M., A.R. and D.K.; visualization, B.V. and V.G.; supervision, D.M., D.K. and A.R.; project administration, A.R., N.M.M. and I.P. I.P. and B.V. contributed equally to this work. N.M.M. and D.K. contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract numbers 451-03-136/2025-03/200143 and 451-03-136/2025-03/20031).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this animal study due to the use of samples collected as part of routine veterinary diagnostic procedures, which do not require additional ethical approval under national regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to veterinary privacy regulations and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMC | Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid |

| CN | Cephalexin |

| AN | Amikacin |

| GM | Gentamicin |

| NN | Tobramycin |

| N | Neomycin |

| CIP | Ciprofloxacin |

| ENF | Enrofloxacin |

| E | Erythromycin |

| AZM | Azithromycin |

| CLR | Clarithromycin |

| C | Chloramphenicol |

| FFC | Florfenicol |

| C | Clindamycin |

| RAM | Rifampicin |

| FA | Fusidic acid |

| SXT | Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole |

| TET | Tetracycline |

| IMP | Imipenem |

| PB | Polymyxin B |

| MRSP | Methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant S. aureus |

| MDR | Multidrug resistant |

References

- Nocera, F.P.; Ambrosio, M.; Fiorito, F.; Cortese, L.; De Martino, L. On Gram-Positive- and Gram-Negative-Bacteria-Associated Canine and Feline Skin Infections: A 4-Year Retrospective Study of the University Veterinary Microbiology Diagnostic Laboratory of Naples, Italy. Animals 2021, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, R.S.; Ramírez, A.S.; Moya-Gil, E.; de la Fuente, S.N.; Suárez-Pérez, A.; Poveda, J.B. Microbiological Survey and Evaluation of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Microorganisms Obtained from Suspect Cases of Canine Otitis Externa in Gran Canaria, Spain. Animals 2024, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.H.; Griffin, C.E.; Campbell, K.L. Müller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology, 7th ed.; Elsevier/Saunders: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bajwa, J. Canine otitis externa—Treatment and complications. Can. Vet. J. 2019, 60, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bourély, C.; Cazeau, G.; Jarrige, N.; Leblond, A.; Madec, J.Y.; Haenni, M.; Gay, E. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacteria isolated from dogs with otitis. Epidemiol. Infect. 2019, 147, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D.-C.; Choi, J.-H.; Boby, N.; Kang, H.-Y.; Kim, S.-J.; Song, H.-J.; Park, H.-S.; Gil, M.-C.; Yoon, S.-S.; Lim, S.-K. Bacterial prevalence in skin, urine, diarrheal stool, and respiratory samples from dogs. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arain, M.B.; Leghari, A.; Khand, F.M.; Hassan, M.F.; Lakho, S.A.; Khoso, A.S.; Malik, M.I.; Lanjar, Z.; Rehman, I.U.; Arain, S. Prevalence and characterization of in vitro susceptibility profile of bacteria harvested from otitis externa in dogs. Pak Euro J. Med. Life Sci. 2024, 7, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Prošić, I.; Milčić-Matić, N.; Milić, N.; Radalj, A.; Aksentijević, K.; Ilić, M.; Nišavić, J.; Radojičić, M.; Gajdov, V.; Krnjaić, D. Molecular prevalence of mecA and mecC genes in coagulase-positive staphylococci isolated from dogs with dermatitis and otitis in Belgrade, Serbia: A one-year study. Acta Vet. Beogr. 2024, 74, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; Ntakiyisumba, E.; Hirwa, F.; Yoon, H.; Oh, S.-I.; Kim, C.; Kim, M.H.; Yoon, J.-S.; Won, G. Prevalence of bacterial pathogens isolated from canines with pyoderma and otitis externa in Korea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysková, P.; Vydrzálová, M.; Mazurová, J. Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria and yeasts isolated from healthy dogs and dogs with otitis externa. J. Vet. Med. Ser. A 2007, 54, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tešin, N.; Stojanović, D.; Stančić, I.; Kladar, N.; Ružić, Z.; Spasojević, J.; Tomanic, D.; Kovačević, Z. Prevalence of the microbiological causes of canine otitis externa and the antibiotic susceptibility of the isolated bacterial strains. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2023, 26, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.A.; Helbig, K.J. The complex diseases of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in canines: Where to next? Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naziri, Z.; Majlesi, M. Comparison of the prevalence, antibiotic resistance patterns, and biofilm formation ability of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in healthy dogs and dogs with skin infections. Vet. Res. Commun. 2023, 47, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Gara, J.P. Into the storm: Chasing the opportunistic pathogen Staphylococcus aureus from skin colonisation to life-threatening infections. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 3823–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.Y.; Lee, H.-H.; Hwang, S.Y.; Hong, J.; Lyoo, K.-S.; Yang, S.-J. Carriage of Staphylococcus schleiferi from canine otitis externa: Antimicrobial resistance profiles and virulence factors associated with skin infection. J. Vet. Sci. 2019, 20, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazi, Y.H.; Almajali, A.M.; Ababneh, M.M.; Ahmed, H.S.; Jaran, A.S. Molecular study on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from dogs and associated personnel in Jordan. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuny, C.; Layer-Nicolaou, F.; Weber, R.; Köck, R.; Witte, W. Colonization of dogs and their owners with Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in households, veterinary practices, and healthcare facilities. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, D.M.; Bhanderi, B.B.; Mathakiya, R.A.; Nimavat, V.R.; Jhala, M.K. Isolation, characterization, antibiogram, and molecular detection of antibiotic resistance genes from bacteria isolated from otitis externa in dogs. Indian J. Vet. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 17, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugden, D.L. Identification and antibiotic susceptibility of bacterial isolates from dogs with otitis externa in Australia. Aust. Vet. J. 2013, 91, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.R.; Sellera, F.P.; Moura, Q.; Carvalho, M.P.; Rosato, P.N.; Cerdeira, L.; Lincopan, N. Zooanthroponotic transmission of drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1160–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardabassi, L.; Houser, G.A.; Frank, L.A.; Papich, M.G. Guidelines for antimicrobial use in dogs and cats. In Guide to Antimicrobial Use in Animals; Guardabassi, L., Jensen, L.B., Kruse, H., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Hussain, K.; Sharma, R.; Chhibber, S.; Sharma, N. Prevalence of canine otitis externa in Jammu. J. Anim. Res. 2014, 4, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.G.; Ballantyne, Z.F.; Hendricks, A.; Church, D.B.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Pegram, C. West Highland White Terriers under primary veterinary care in the UK in 2016: Demography, mortality and disorders. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 2019, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salib, F.A.; Baraka, T.A. Epidemiology, genetic divergence and acaricides of Otodectes cynotis in cats and dogs. Vet. World 2011, 4, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridomichelakis, M.N.; Farmaki, R.; Leontides, L.S.; Koutinas, A.F. Aetiology of canine otitis externa: A retrospective study of 100 cases. Vet. Dermatol. 2007, 18, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Forde, B.M.; Kidd, T.J.; Harris, P.N.A.; Schembri, M.A.; Beatson, S.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Walker, M.J. Antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00181-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beco, L.; Guaguère, E.; Méndez, C.L.; Noli, C.; Nuttall, T.; Vroom, M. Suggested guidelines for using systemic antimicrobials in bacterial skin infections: Part 2—Antimicrobial choice, treatment regimens and compliance. Vet. Rec. 2013, 172, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escher, M.; Vanni, M.; Intorre, L.; Caprioli, A.; Tognetti, R.; Scavia, G. Use of antimicrobials in companion animal practice: A retrospective study in a veterinary teaching hospital in Italy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirollo, C.; Nocera, F.P.; Piantedosi, D.; Fatone, G.; Della Valle, G.; De Martino, L.; Cortese, L. Data on before and after the traceability system of veterinary antimicrobial prescriptions in small animals at the University Veterinary Teaching Hospital of Naples. Animals 2021, 11, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dégi, J.; Morariu, S.; Simiz, F.; Herman, V.; Beteg, F.; Dégi, D.M. Future Challenge: Assessing the Antibiotic Susceptibility Patterns of Staphylococcus Species Isolated from Canine Otitis Externa Cases in Western Romania. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikoska, I.; Popova Hristovska, Z.; Matevski, I.; Jurhar Pavlova, M.; Ratkova Manovska, M.; Cvetkovikj, A.; Cvetkovikj, I. Phenotypic and Molecular Characterization of Antimicrobial Resistance in Canine Staphylococci from North Macedonia. Mac. Vet. Rev. 2025, 48, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.; Zhelev, G.; Marutsov, P.; Koev, K.; Georgieva, S.; Toneva, I.; Urumova, V. Microbiological and antibacterial resistance profile in canine otitis externa—A comparative analysis. Bulg. J. Vet. Med. 2019, 22, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matanović, K.; Mekić, S.; Šeol, B. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from dogs and cats in Croatia during a six-month period. Vet. Arh. 2012, 82, 505–517. [Google Scholar]

- Maksimović, Z.; Dizdarević, J.; Babić, S.; Rifatbegović, M. Antimicrobial resistance in coagulase-positive Staphylococci isolated from various animals in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Microb. Drug Resist. 2022, 28, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönthal, T.; Eklund, M.; Thomson, K.; Piiparinen, H.; Sironen, T.; Rantala, M. Antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and the molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius in small animals in Finland. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Duijkeren, E.; Kamphuis, M.I.C.; van der Mije, I.C.; Laarhoven, L.M.; Duim, B.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Houwers, D.J. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius between infected dogs and cats and contact pets, humans and the environment in households and veterinary clinics. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 150, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerlin, P.; Burnens, A.P.; Frey, J.; Kuhnert, P.; Nicolet, J. Molecular epidemiology and genetic linkage of macrolide and aminoglycoside resistance in Staphylococcus intermedius of canine origin. Vet. Microbiol. 2001, 79, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuer, L.; Frenzer, S.K.; Merle, R.; Bäumer, W.; Lübke-Becker, A.; Klein, B.; Bartel, A. Comparative analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius prevalence and resistance patterns in canine and feline clinical samples: Insights from a three-year study in Germany. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, A.; Cain, C.L.; Ferrer, L.; Nishifuji, K.; Varjonen, K.; Papich, M.G.; Guardabassi, L.; Frosini, S.M.; Barker, E.N.; Weese, J.S. Antimicrobial use guidelines for canine pyoderma by the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases (ISCAID). Vet. Dermatol. 2025, 36, 234–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; Heilmann, C.; Peters, G. Coagulase-negative Staphylococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 870–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino-Farfán, J.A.; Vega, L.G.A.; Espinoza, S.Y.C.; Magallanes, S.G.; Moreno, J.J.S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus schleiferi subspecies coagulans associated with otitis externa and pyoderma in dogs. Open Vet. J. 2021, 11, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Xu, J.; Meng, X.; Wu, Z.; Hou, X.; He, Z.; Shang, R.; Zhang, H.; Pu, W. Molecular epidemiology and characterization of antimicrobial-resistant Staphylococcus haemolyticus strains isolated from dairy cattle milk in Northwest, China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1183390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). European Risk Assessment Report: Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus Epidermidis; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Trif, E.; Cerbu, C.; Olah, D.; Zăblău, S.D.; Spînu, M.; Potârniche, A.V.; Pall, E.; Brudașcă, F. Old antibiotics can learn new ways: A systematic review of florfenicol use in veterinary medicine and future perspectives using nanotechnology. Animals 2023, 13, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, C.; de Jong, A.; Moyaert, H.; El Garch, F.; Janes, R.; Klein, U.; Morrissey, I.; Thiry, J.; Youala, M. Antimicrobial susceptibility monitoring of dermatological bacterial pathogens isolated from diseased dogs and cats across Europe (ComPath results). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 1254–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, Y.; Tsuyuki, Y.; Goto, M.; Yoshida, H.; Takahashi, T. Novel quinolone-nonsusceptible Streptococcus canis strains with point mutations in quinolone resistance-determining regions and their related factors. Jpn J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 73, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanishi, I.; Iyori, K.; Také, A.; Asahina, R.; Tsunoi, M.; Hirano, R.; Uchiyama, J.; Toyoda, Y.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Hayashi, S. Antibiotic-resistant status and pathogenic clonal complex of canine Streptococcus canis-associated deep pyoderma. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.-E.; Chung, T.-H.; Hwang, C.-Y. Identification of VIM-2 metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from dogs with pyoderma and otitis in Korea. Vet. Dermatol. 2018, 29, 186-e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KuKanich, K.S.; Bagladi-Swanson, M.; KuKanich, B. Pseudomonas aeruginosa susceptibility, antibiogram and clinical interpretation, and antimicrobial prescribing behaviors for dogs with otitis in the Midwestern United States. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 45, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Publishes List of Bacteria for Which New Antibiotics Are Urgently Needed; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Mekić, S.; Matanović, K.; Šeol, B. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from dogs with otitis externa. Vet. Rec. 2011, 169, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secker, B.; Shaw, S.; Atterbury, R.J. Pseudomonas spp. in canine otitis externa. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Office for Animal Health (NOAH). Critically Important Antibiotics in Veterinary Medicine: European Medicines Agency Recommendations; NOAH: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.noah.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/NOAH-briefing-on-CIAs-07122016.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU). 2022/1255 of 19 July 2022 designating antimicrobials or groups of antimicrobials reserved for treatment of certain infections in humans, in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2019/6 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Off. J. Eur. Union 2022, 191, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, C.B.; Botoni, L.S.; Coura, F.M.; Silva, R.O.; Santos, R.D.D.; Heinemann, M.B.; Costa-Val, A.P. Frequency and antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in dogs with otitis externa. Ciênc. Rural 2018, 48, e20170738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefańska, I.; Kwiecień, E.; Kizerwetter-Świda, M.; Chrobak-Chmiel, D.; Rzewuska, M. Tetracycline, macrolide and lincosamide resistance in Streptococcus canis strains from companion animals and its genetic determinants. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.; Maboni, G.; Battisti, R.; da Costa, L.; Selva, H.L.; Levitzki, E.D.; Gressler, L.T. High rates of multidrug resistance in bacteria associated with small animal otitis: A study of cumulative microbiological culture and antimicrobial susceptibility. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 165, 105399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, F.M.; Santana, J.A.; Silva, B.A.; Xavier, R.G.C.; Bonisson, C.T.; Câmara, J.L.S.; Rennó, M.C.; Cunha, J.L.R.; Figueiredo, H.C.P.; Lobato, F.C.F.; et al. Occurrence and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. in diseased dogs in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BVL). GERMvet—Veterinary Medicines/Antibiotic Resistance. Available online: https://www.bvl.bund.de/EN/Tasks/05_Veterinary_medicines/01_Tasks_vmp/05_Tasks_AntibioticResistance/05_GERMvet/vmp_GERMvet_node.htm (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Swedish Veterinary Agency (SVA). Svarm—Resistance Monitoring. Available online: https://www.sva.se/en/what-we-do/antibiotics/svarm-resistance-monitoring (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- ANSES. RESAPATH—Resistance Monitoring. Available online: https://resapath.anses.fr/ (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Statistički Zavod Republike Srbije (SORS). Estimates of Population. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-us/oblasti/stanovnistvo/procene-stanovnistva/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Veterinary Directorate of the Republic of Serbia. Central Database of Registered Dogs in Serbia—Annual Report 2022; Veterinary Directorate, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management: Belgrade, Serbia, 2022. Available online: https://www.vet.minpolj.gov.rs/ (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated from Animals, 4th ed.; CLSI document VET01-A4; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 27th ed.; CLSI supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 28th ed.; CLSI supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 29th ed.; CLSI supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th ed.; CLSI supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 31st ed.; CLSI supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 32nd ed.; CLSI supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 33rd ed.; CLSI supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 34th ed.; CLSI supplement M100; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 7.1; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST): Malmö, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 8.0; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST): Malmö, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 9.0; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST): Malmö, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 10.0; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST): Malmö, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 11.0; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST): Malmö, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 12.0; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST): Malmö, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 13.0; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST): Malmö, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 14.0; European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST): Malmö, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, R.; Cantón, R.; Brown, D.F.J.; Giske, C.G.; Heisig, P.; MacGowan, A.P.; Mouton, J.W.; Nordmann, P.; Rodloff, A.C.; Rossolini, G.M.; et al. EUCAST expert rules in antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, A.; Damborg, P.; Nielsen, S.S. Antimicrobial resistance in methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius of canine origin: Literature review from 1980 to 2013. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 171, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, J.; Millis, N.; Duckett Jones, R.; Johnson, B.; Kania, S.A.; Odoi, A. Patterns of antimicrobial, multidrug and methicillin resistance among Staphylococcus spp. isolated from canine specimens submitted to a diagnostic laboratory in Tennessee, USA: A descriptive study. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, H.D. Detection of methicillin resistance in staphylococci by PCR. In Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook, 2nd ed.; Murray, P.R., Ed.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 12.5.3.1–12.5.3.9. [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.